Volume 1, No. 1, Art. 14 – January 2000

Empirically Grounded Construction of Types and Typologies in Qualitative Social Research

Susann Kluge

Abstract: In qualitative social research, there are only a few approaches in which the process of typology construction is explicated and systematised in detail; furthermore, you can find very different concepts of types like ideal types, real types, prototypes, extreme types, types of structure. Because the construction of typologies is of central importance for the qualitative social research, it is necessary to clarify the concept of types and the process of typology construction. Therefore, this article will first present a general definition of the concept of types, and then how this definition forms the basis of rules for a systematic and controlled construction of types and typologies.

Key words: type, typology, ideal type, prototype, construction of types and typologies

Table of Contents

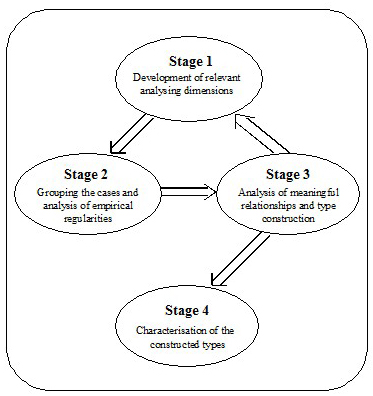

1. Problem

2. The Concept of Types

2.1 Combination of attributes

2.2 Empirical regularities and meaningful relationships

3. Rules for an Empirically Grounded Type Construction

3.1 Development of relevant analysing dimensions

3.2 Grouping the cases and analysis of empirical regularities

3.3 Analysis of meaningful relationships and type construction

3.4 Characterisation of the constructed types

The concept of types has played a meaningful role since the beginning of empirical social sciences (cf. MENGER 1883; WEBER 1988/1904) and has experienced a renaissance in the field of qualitative social research since the 80's. In many qualitative studies, types are constructed in order to comprehend, understand and explain complex social realities as far as possible (e.g. BOHNSACK 1989, 1991; DIETZ et al. 1997; GERHARDT 1986; HONER 1993; LUDWIG 1996; NAGEL 1997). However, the research practice is confronted with the problem how these types can be constructed systematically and transparently. In current sociological literature, there exist only a few approaches in which the process of type construction is explicated and systematised in detail (e.g. GERHARDT 1986, 1991a, 1991b; KUCKARTZ 1988, 1995, 1996). Moreover, very different analysis steps are carried out in single studies and in the few general approaches for type construction which are presented in literature (see also: HAUPERT 1991; JUETTEMANN 1981, 1989; MAYRING 1990, 1993). Also different concepts of type are used (e.g. ideal types, empirical types, structure types, prototypes etc.) or the concept of type is not defined explicitly at all. In order to clarify these basic problems, first a general definition of the concept of types will be presented. In the next step this definition forms the basis to formulate some rules for a systematical and transparent construction of types and typologies. [1]

Every typology is the result of a grouping process: An object field is divided in some groups or types with the help of one or more attributes (cf. BAILEY 1994, pp.1; FRIEDRICHS 1983, p.90; HAUPERT 1991, p.240; SODEUR 1974, pp.1). The elements within a type have to be as similar as possible (intern heterogeneity on the "level of the type") and the differences between the types have to be as strong as possible (external heterogeneity on the "level of the typology"; cf. KLUGE 1999, pp.26). The constructed subgroups with common attributes that can be described and featured by a particular constellation of these properties are defined with the term type. Therefore, LAZARSFELD (1937) and BARTON (1955) developed the concept that every type—in spite of all the differences which can exist with regard to formal qualities like the degree of abstraction and complexity or the time-space links etc.—can be defined as a combination of its attributes. But between the single properties not only empirical correlations have to exist ("Kausaladaequanz"; WEBER 1972/1921, p.5), but also meaningful relationships ("Sinnadaequanz", WEBER 1972/1921, p.5; for more details about the definition of the concept of types and the different kinds of types and typologies see KLUGE 1999). [2]

Accordingly, every typology is based on an attribute space which results from the combination of the selected attributes and their dimensions. If this attribute space is represented with the help of multidimensional tables, we gain a general view over all possible combinations which are theoretically conceivable. Since all possible combinations often do not exist in reality and/or the differences between individual combinations of attributes are not relevant for the research question, single fields of the attribute space can be summarised. BARTON (1955, pp.45) and LAZARSFELD (1937, pp.126 and LAZARSFELD & BARTON 1951, pp.172) call this proceeding "typological operation" of reduction. It is very effective in order to concentrate the existing variety and to reduce it to a few relevant types. [3]

For example, if we try to typify the delinquent behaviour of adolescents by means of different aspects, we can at first distinguish between different levels of delinquency1) (high, low, non) and the development of the delinquency2) (continuous, episode) (cf. KLUGE 1999, p.227). Since the two attributes have in each case two and/or three values, six possible combinations result (see Tab. 1). The further analyses of the adolescents who are only "low" delinquent have shown, that it is not reasonable to make a differentiation, whether they commit these offences continuously or "get out" in terms of a certain period. And it is not possible for an adolescents "without" delinquency to show a development of delinquent behaviour. For these reasons the two groups are summarised in each case to reduce the original attribute space. There are now four remaining distinctions between adolescents:

continuously high level of delinquency ("continuous delinquency"),

exit from high delinquency ("episode"),

only "minor offences",

no offences ("conformity").

|

Level of delinquency |

Development of delinquency |

|||

|

|

continuous |

episode |

||

|

high |

1 continuous |

episode 2 |

||

|

low |

3 |

minor offences |

4 |

|

|

non |

5 |

conformity |

6 |

|

Tab. 1: Delinquent behaviour of adolescents [4]

2.2 Empirical regularities and meaningful relationships

In addition to WEBER (1972/1921), BECKER (1968/1950), McKINNEY (1969, 1970), and BAILEY (1973) pointed out that both the empirical regularities and correlations (Kausaladaequanz) and the existing meaningful relationships (Sinnadaequanz) must be analysed in order to achieve a suitable interpretation of typical social action (eine "richtige kausale Deutung typischen Handelns") and to develop understandable ("verstaendliche") types of social action, therefore: sociological rules (cf. WEBER 1972/1921, pp.5). On the one hand, empirical investigations need always theoretical knowledge, because investigations can not be carried out purely inductively (see KELLE 1998; KELLE & KLUGE 1999). On the other hand, qualitative social research must also be based on empirical investigations, if meaningful statements about social reality are to be made and not empirically remote constructs. It is only, when empirical analyses are combined with theoretical knowledge, that "empirically grounded types" can be constructed. Types are always constructions (which are dependent on the attributes that should form the basis for the typology). Thus, this term—in contrast to WEBER's ideal type or BECKER's "constructed type"—should clarify the empirical part of the constructed types (cf. KLUGE 1999, p.58, p.87). [5]

3. Rules for an Empirically Grounded Type Construction

Starting from these general considerations for the concept of types, four stages of analysis can be distinguished for the process of type construction (for more details see KLUGE 1999 and KELLE & KLUGE 1999): [6]

3.1 Development of relevant analysing dimensions

If the type is defined as a combination of attributes, one first needs properties and/or dimensions, which form the basis for the typology. With the help of these attributes, the similarities and differences between the research elements (persons, groups, behaviour, norms, cities, organisations etc.) must be adequately grasped. And finally the constructed groups and types have to be described with the help of these properties. For standardised studies these variables and their possible permissible attributes have to be defined already before the data collection. In qualitative studies, these properties and their dimensions are elaborated and "dimensionalised" during the process of the analysis by means of the collected data and the theoretical knowledge (for the term of dimensionalisation see: STRAUSS 1987; STRAUSS & CORBIN 1990; KELLE 1998; KELLE & KLUGE 1999, pp.67). [7]

3.2 Grouping the cases and analysis of empirical regularities

The cases can be grouped by means of the defined properties and their dimensions and the identified groups can be analysed with regard to empirical regularities. Using the "concept of attribute space" (cf. LAZARSFELD 1937; LAZARSFELD & BARTON 1951; BARTON 1955), one can receive a general view of all potential possible combinations and the concrete empirical distribution of the cases to the different combinations of the properties. Cases which are assigned to a combination of attributes must be compared with each other, in order to check the intern homogeneity of the constructed groups—which form the basis for the later types. This is necessary, because the cases must resemble each other to a large extent themselves on the "level of the type". Furthermore the groups must be compared among one another in order to check whether there is a sufficiently high external heterogeneity on the "level of the typology" and in order to check whether the resulting typology contains sufficient heterogeneity and/or variation in the data. [8]

3.3 Analysis of meaningful relationships and type construction

If the examined social phenomena should become not only described but also "understood" and "explained", the meaningful relationships, which form the basis of the empirically founded groups and/or combinations of attributes, must be analysed. Normally different reasons lead to a reduction of the attribute space and therefore of the groups (= combinations of attributes) to a few types. In addition, these analyses mostly lead to further attributes (stage 1), which must be considered at the type construction, the attribute space has to be complemented and the new groups have to be examined again for empirical regularities (stage 2) and meaningful relationships (stage 3; see Fig. 1). In qualitative studies, the interviewees can comment explicitly and at length on existing relationships, and the meaningful relationships can be analysed much more differentiated and more comprehensive on the basis of qualitative data material than with standardised data.

Fig. 1: Model of empirically grounded type construction [9]

The procedure of the stages 2 and 3 can be illustrated briefly by means of a study, which analyses the relationship between the occupational (training) career and the delinquent behaviour of adolescents (DIETZ et al. 1997). The cross tabulation of the two central analysis dimensions "occupational career" and "delinquent behaviour" (which were elaborated and dimensionalised before on account of comprehensive data analyses) leads, at first, to an attribute space with eight possible combinations (see Tab. 2). If the cases are assigned to the single cells, the following distribution results at the time of the third questioning wave:

|

Type of delinquency |

Occupational career3) |

|||||

|

|

successful |

failed |

sum |

|||

|

continuous |

12 |

10 men |

4 |

1 man |

11 men |

16 |

|

episode |

7 |

4 men |

6 |

3 men |

7 men |

13 |

|

minor offences |

9 |

5 men |

4 |

4 women |

5 men |

13 |

|

conformity |

2 |

1 man |

2 |

1 man |

2 men |

4 |

|

sum |

30 |

20 men 10 women |

16 |

5 men |

25 men |

46 |

Tab. 2: Distribution of the examined cases referring to the occupational career and the type of delinquency at the time of the third wave4) [10]

The very extensive contrasting analyses within and between the groups (that cannot be carried out here any further on account of their complexity; but see DIETZ et al. 1997 and KLUGE 1999) would lead finally to a reduction of the attribute space and to a typology, which contains three types of juvenile delinquent careers (further the group of the conformers was not considered during the analyses because of its low degree of delinquency):

|

Type of delinquency |

Occupational career |

|

|

successful |

failed |

|

|

continuous |

type I |

type II |

|

episode |

type III |

|

|

minor offences |

"conformers" |

|

|

conformity |

||

Tab. 3: Three types of relationship between occupational career and delinquent behaviour (cf. KLUGE 1999, p.231)

|

Type I: |

The mostly masculine adolescents of the type "double life" are occupationally successful, simultaneously highly burdened with delinquency, and officially recorded through the judicial system (police and justice) (DIETZ et al. 1997, p.247). |

|

Type II: |

Adolescents of the type "marginalisation" may fail not only in their occupational career but are also continuously burdened with high delinquency. In this case, the young people normally drop out of the education system and/or are excluded because of a deviating life-style (life in subcultures) (DIETZ et al. 1997, p.252). |

|

Type III: |

The third type "episode" comprises such adolescents whose high level of delinquency decreases in the course of time. Here, the occupational career has no influence on a stabilisation of delinquent careers. Rather, in both groups the getting out of delinquency occurs mostly with a stable partnership or by getting out of a youth clique at the same time (DIETZ et al. 1997, pp.254). [11] |

3.4 Characterisation of the constructed types

Finally the constructed types are described extensively by means of their combinations of attributes as well as by the meaningful relationships. In addition, the criteria for the characterisation of the types have to be specified—by prototypes, ideal types, extreme types etc. [12]

These four stages represent sub-goals of the process of type construction and can be realised with the help of different analysing methods and techniques which are depending on the research question and the kind and quality of the data (see Fig. 2). In such a way e.g., the cases can be grouped by help of the "concept of attribute space" (BARTON 1955; LAZARSFELD 1937), by contrasting single cases (GERHARDT 1986, 1991a, 1991b) or by a computer-assisted grouping procedure like cluster analysis (KUCKARTZ 1988, 1995, 1996).

|

Fig. 2: Different analysing methods and techniques of the "model of empirically grounded type construction" [13]

In contrast to the approaches of GERHARDT or KUCKARTZ, the "model of empirically grounded type construction" shows a considerably greater openness and flexibility. Every stage of analysis can be realised with the aid of different analyse methods and techniques and the model complies very well with the variety of qualitative research questions and with the different quality of the data. For every study, it can be tested which analysing methods are most effective to achieve the sub-goals of the single stages of analysis. Depending on the research question and the kind of the data, it may be more reasonable to maintain the context of a case while developing the analysing dimensions (e.g. during biographical studies of the life course), or to "isolate" single topic aspects in order to be able to analyse these in a purposeful manner (e.g. in expert interviews). In spite of the variety of the different methods, the four "stages of analysis" guarantee that the central sub-goals of the process of type construction are being realised (development of relevant analysing dimensions, grouping of the cases and analysis of empirical regularities, analysis of meaningful relationships and type construction, characterisation of the types). Therefore, types can be constructed systematically and transparent with the aid of the model, if this process is documented in detail—e.g. as demonstrated by GERHARDT (1986) in her study of "patient careers". On account of the openness of the model it is not only possible to compare different approaches with each other but also to achieve a combination of the different analysing techniques and therefore to overcome the separation between the different approaches. [14]

1) This index contains the kind of offences committed, the frequency of the individual offences and contact with institutions of the criminal justice system (police and justice; see KLUGE 1999, p.226). <back>

2) The example comes from a research project, that analyses the relations between the occupational (training) career and the delinquent behaviour of adolescents resp. young adults (DIETZ et al. 1997). <back>

3) The "occupational career" is classified as successful if the adolescents are (still) in the qualifying training system or have already started a qualified occupation. The "occupational career" is considered as failed if the adolescents are in unskilled occupations or unemployed. In this case, the respective investigation date is decisive (see also, footnote 4). <back>

4) See KLUGE (1999, p.229) and DIETZ et al. (1997, p.245).

The table only reflects the distribution of the adolescents at the third panel wave. The assignment can change in the process of the study (five investigations are planned in total) if e.g. an adolescent finds a place of work or another young person becomes unemployed. Also the delinquent behaviour of the adolescents can still decrease or increase again at a later time. While the assignment of the individual cases can vary, the basic assignment raster remains—also the attribute space that is determined by the properties "occupational career" and "type of delinquency" (provided that the attributes must not be defined again!). <back>

Bailey, Kenneth D. (1973). Monothetic and Polythetic Typologies and their Relation to Conceptualization, Measurement and Scaling. American Sociological Review, 38, 18-33.

Bailey, Kenneth D. (1994). Typology and Taxonomies. An Introduction to Classification Techniques. Thousand Oaks: Sage.

Barton, Allen H. (1955). The Concept of Property-space in Social Research. In Paul F Lazarsfeld & Morris Rosenberg (Eds.), The Language of Social Research (pp.40-53). New York: Free Press.

Becker, Howard S. (1968/1950). Through Values to Social Interpretation. Essays on Social Contexts, Actions, Types, and Prospects. New York: Greenwood press. [1st edition, 1950, Durham, N.C.: Duke University Press].

Bohnsack, Ralf (1989). Generation, Milieu und Geschlecht. Ergebnisse aus Gruppendiskussionen mit Jugendlichen. Opladen: Leske and Budrich.

Bohnsack, Ralf (1991). Rekonstruktive Sozialforschung. Einführung in Methodologie und Praxis qualitativer Forschung. Opladen: Leske and Budrich.

Dietz, Gerhard-Uhland; Matt, Eduard; Schumann, Karl F. & Seus, Lydia (1997). "Lehre tut viel ... ": Berufsbildung, Lebensplanung und Delinquenz bei Arbeiterjugendlichen. Münster: Votum.

Friedrichs, Jürgen (1983). Methoden empirischer Sozialforschung (11th edn.). Opladen: Westdeutscher Verlag. [1st edition, 1973].

Gerhardt, Uta (1986). Patientenkarrieren. Eine medizinsoziologische Studie. Frankfurt/Main: Suhrkamp.

Gerhardt, Uta (1991a). Typenbildung. In Uwe Flick et al. (Eds.), Handbuch Qualitative Sozialforschung. Grundlagen, Konzepte, Methoden und Anwendungen (pp.435-439). München: Psychologie Verlags Union.

Gerhardt, Uta (1991b). Gesellschaft und Gesundheit. Begründung der Medizinsoziologie. Frankfurt/Main: Suhrkamp.

Haupert, Bernhard (1991). Vom narrativen Interview zur biographischen Typenbildung. In Detlef Garz & Klaus Kraimer (Eds.), Qualitativ-empirische Sozialforschung. Konzepte, Methoden, Analysen (pp.213-254). Opladen: Westdeutscher Verlag.

Honer, Anne (1993). Lebensweltliche Ethnographie. Ein explorativ-interpretativer Forschungsansatz am Beispiel von Heimwerker-Wissen. Wiesbaden: Deutscher Universitäts-Verlag.

Jüttemann, Gerd (1981). Komparative Kasuistik als Strategie psychologischer Forschung. Zeitschrift für Klinische Psychologie und Psychotherapie, 29(2), 101-118.

Jüttemann, Gerd (1989) (Ed.). Qualitative Forschung in der Psychologie. Grundfragen, Verfahrensweisen, Anwendungsfelder [2nd edn.). Heidelberg: Asanger. [1st edition, 1985, Weinheim: Beltz].

Kelle, Udo (1998). Empirisch begründete Theoriebildung. Zur Logik und Methodologie interpretativer Sozialforschung (2nd edn.). Weinheim: Deutscher Studien Verlag.

Kelle, Udo & Kluge, Susann (1999). Vom Einzelfall zum Typus. Fallvergleich und Fallkontrastierung in der qualitativen Sozialforschung. Opladen: Leske und Budrich.

Kluge, Susann (1999). Empirisch begründete Typenbildung. Zur Konstruktion von Typen und Typologien in der qualitativen Sozialforschung. Opladen: Leske und Budrich.

Kuckartz, Udo (1988). Computer und verbale Daten. Chancen zur Innovation sozialwissenschaftlicher Forschungstechniken. Frankfurt/Main: Peter Lang.

Kuckartz, Udo (1995). Case-Orientied Quantification. In Udo Kelle, Gerald Prein & Katherine Bird (Eds.), Computer-Aided Qualitative Data Analysis. Theory, Methods, and Practice (pp.158-166). London: Sage.

Kuckartz, Udo (1996). MAX für WINDOWS: ein Programm zur Interpretation, Klassifikation und Typenbildung. In Wilfried Bos & Christian Tarnai (Eds.), Computerunterstützte Inhaltsanalyse in den Empirischen Sozialwissenschaften. Theorie, Anwendung, Software (p.229-243). Münster: Waxmann.

Lazarsfeld, Paul F. (1937). Some Remarks on the Typological Procedures in Social Research. Zeitschrift für Sozialforschung, VI, 119-139.

Lazarsfeld, Paul F. & Barton, Allen H. (1951). Qualitative Measurement in the Social Sciences. Classification, Typologies, and Indices. In Daniel Lerner & Harold D. Lasswell (Eds.), The Policy Sciences (pp.155-192). Stanford University Press.

Ludwig, Monika (1996). Armutskarrieren. Zwischen Abstieg und Aufstieg im Sozialstaat. Opladen: Westdeutscher Verlag.

Mayring, Philipp (1990). Qualitative Inhaltsanalyse. Grundlagen und Techniken (2nd revised edn.). Weinheim: Deutscher Studien Verlag. [1st edition, 1983, Beltz].

Mayring, Philipp (1993). Einführung in die qualitative Sozialforschung. Eine Anleitung zu qualitativem Denken (2nd revised edn.). Weinheim: Psychologie Verlags Union. [1st edn, 1990].

McKinney, John C. (1969). Typification, Typologies, and Sociological Theory. Social Forces, 48(1), 1-12

McKinney, John C. (1970). Sociological Theory and the Process of Typification. In John C. McKinney & Edward A. Tiryakian (Eds.), Theoretical Sociology. Perspectives and Developments (pp.235-269). New York: Meredith.

Menger, Carl (1883). Untersuchungen über die Methode der Socialwissenschaften, und der Oekonomie insbesondere. Leipzig: Duncker & Humblot.

Nagel, Ulrike (1997). Engagierte Rollendistanz. Professionalität in biographischer Perspektive. Opladen: Leske and Budrich.

Sodeur, Wolfgang (1974). Empirische Verfahren zur Klassifikation. Stuttgart: Teubner.

Strauss, Anselm L. (1987). Qualitative Analysis for Social Scientists. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Strauss, Anselm L. & Corbin, Juliet (1990). Basics of Qualitative Research. Grounded Theory Procedures and Techniques. Newbury Park, London, New Delhi: Sage.

Weber, Max (1972/1921): Wirtschaft und Gesellschaft. Grundriß der verstehenden Soziologie. 5th Edn, revised by Johannes Winckelmann, Tübingen: Mohr (1st edition, 1921)

Weber, Max (1988/1904): Die "Objektivität" sozialwissenschaftlicher und sozialpolitischer Erkenntnis. In Max Weber, Gesammelte Aufsätze zur Wissenschaftslehre (edited by Johannes Winckelmann, 7th edn., pp.146-214). Tübingen: Mohr. [1st edition, 1904, Archiv für Sozialwissenschaft und Sozialpolitik, 19, 22-87].

Susann KLUGE

Contact:

Dr. Susann Kluge

Sonderforschungsbereich 186 "Statuspassagen und Risikolagen im Lebensverlauf" der Universität Bremen

Bereich Methodenentwicklung und EDV

Wiener Str. / FVG-West

Postfach 330 440

28334 Bremen, Germany

Phone: +49 / 421 / 218 – 4166

Fax: +49 / 421 / 218 – 4153

E-mail: skluge@sfb186.uni-bremen.de

Kluge, Susann (2000). Empirically Grounded Construction of Types and Typologies in Qualitative Social Research [14 paragraphs]. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung / Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 1(1), Art. 14, http://nbn-resolving.de/urn:nbn:de:0114-fqs0001145.

Revised 3/2007