Volume 9, No. 3, Art. 25 – September 2008

Mapping the Imaginary—Maps in Fantasy Role-Playing Games

Tobias Röhl & Regine Herbrik

Abstract: This paper deals with cartographic representations as means of communicating the imaginary using maps in fantasy role-playing games as an example. Drawing on SCHUTZian accounts of intersubjectivity and communication we understand maps as one of many strategies to deal with the problem of "medium transcendencies" posed by communicating with others. The methodology of "sociological hermeneutics" (SOEFFNER) is introduced as means of approaching maps and the interactions they are involved in. In our analyses of maps used in role-playing games we can then show that maps are not only a means of locating oneself but also a means of actively creating a meaningful place in which we are entangled. Thus, maps help to form a sense of belonging in (imaginary) territories which are only given to us in mediated form.

Key words: maps; cartography; role-playing games; video hermeneutics; sociological hermeneutics; visual sociology

Table of Contents

1. Communicating the Imaginary and Maps—An Introduction

2. Communication, Performativity and the Imaginary—Theoretical Considerations

2.1 A Schutzian and anthropological perspective on communication

2.2 The imaginary and its performative mediation

3. Fictional Worlds and Interactive Story-telling: Pen and Paper Role-Playing Games

3.1 Role-playing games—An introduction

3.2 Participants, players and characters—GOFFMAN and beyond

3.3 Fantasy and imaginary worlds

4. Hermeneutic Analysis of Visual Data

4.1 Approaching the field

4.2 Video hermeneutics

4.3 Cartographic interpretations

5. Cartography of Imaginary Worlds—Interpreting Maps in Role-Playing Games

5.1 Where?—Maps and situating oneself in the world

5.2 Maps and (narrative) relevance

5.3 Cartographic possibilities and restrictions—The "view from nowhere" and cartographic determinations

5.4 Where to?—Maps and planning actions

5.5 Inscribing oneself and making tactical decisions

5.6 Wherein?—Maps and the creation of a fictitious world

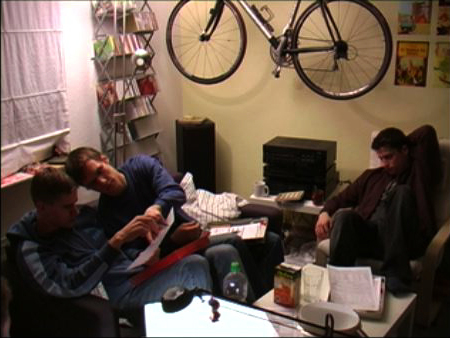

5.7 Maps in-between game world and everyday life-world

6. Maps and the Imaginary—Concluding Remarks

1. Communicating the Imaginary and Maps—An Introduction

Communicative interaction often requires the interaction partners to refer to objects and circumstances which transgress the boundaries of face-to-face situations: they report on past events, describe distant places etc. Sometimes the objects and circumstances in question are imaginary, i.e. when buildings or journeys are planned, a story is told or a wish is expressed. The project "Kommunikative Vermittlungsstrategien des Imaginären" ("Communicating the Imaginary")1) investigates the attempts of agents to share such mental images with their interaction partners and focuses on communicative interactions in which the agents cooperatively construct a shared imaginary world. By analyzing these kinds of communicative interactions in so-called paper-based role-playing games the project aims to enquire into how processes of communicating the imaginary exactly work. The participants of such games assume the roles of fictional characters and collaboratively create stories set in fictitious worlds, thus fabricating and referring to an imaginary sphere throughout.2) [1]

An important means of communicating the imaginary are maps. Cartographic representations lend themselves well to narrations where imaginary places are to be created and presented, and are an integral part of fictional works like STEVENSON's "Treasure Island" (1982 [1883]) or J.R.R. TOLKIEN's "Lord of the Rings" (1979 [1954/55]).3) Pen and paper role-playing games are no exception to this. Maps and floor plans are an important feature of many of such games. Not only can they be found in many role-playing publications, but also in the play itself where—more often than not—game masters and players alike draw them themselves. All of the role-playing groups we observed so far have used cartographic representations in their gaming sessions. Dealing with maps in role-playing games and their role in communicating the imaginary the following questions arose: What places do maps fill among the communicative strategies in role-playing games? In what way do they contribute to the mediation of the imaginary? [2]

The article deals with these questions in the following way. In Section 2 theoretical considerations underlying our research are introduced. Section 3 presents an account of role-playing games and the fantasy genre, explaining why these games are a perfect example of the communicative processes we are interested in. Our attempt to deal with visual data from the perspective of "sociological hermeneutics" (SOEFFNER, 2004) is shown in Section 4. Then our analysis of maps and role-playing interactions involving them is presented in detail in Section 5. Finally, we conclude with some remarks on maps and the imaginary in Section 6. [3]

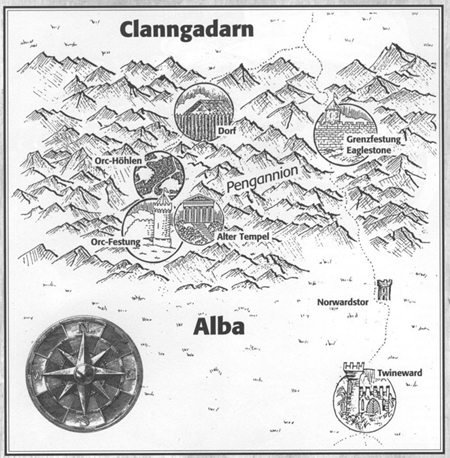

2. Communication, Performativity and the Imaginary—Theoretical Considerations

2.1 A Schutzian and anthropological perspective on communication

The everyday life-world is an intersubjective world in which

"the following is taken for granted without question: (a) the corporeal existence of other men; (b) that these bodies are endowed with consciousness similar to my own; (c) that the things in the outer world included in my environs and that of my fellow-men are the same for us and have fundamentally the same meaning; (d) that I can enter into interrelations and reciprocal actions with my fellow-men" (SCHUTZ & LUCKMANN, 1974, p.5) [4]

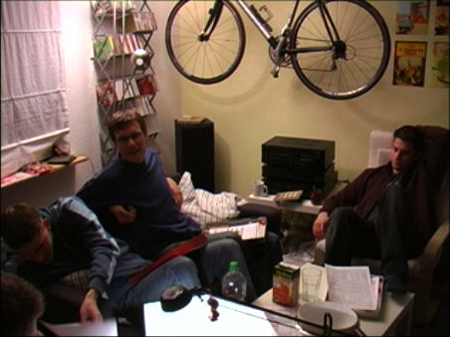

From this follows:

"that I can, up to a certain point, obtain knowledge of the lived experiences of my fellow-men—for example, the motives of their acts—so, too, I also assume that the same holds reciprocally for them with respect to me" (SCHUTZ & LUCKMANN,1974, p.4) [5]

Consequently, in the "natural attitude" (SCHUTZ & LUCKMANN 1974, pp.3-5) of the everyday life-world, agents assume that they can easily communicate with each other. This assumption is not without limits, however: "When a man tries to slip into another person's shoes, he fails" (SCHUTZ & LUCKMANN, 1989, p.102). One can only grasp the subjective meaning of alter's actions in idealized form. To fully comprehend the other and his or her actions I would have to access his or her—inaccessible—consciousness. This limitation constitutes one of the many boundaries of one's life-world. The boundary separating the consciousness of ego and alter ego belongs to the "medium transcendencies" (SCHUTZ & LUCKMANN, 1989, pp.109-117) of the life-world. [6]

Agents employ different strategies to get a glimpse of that which lies beyond the boundaries of the "medium transcendencies." Although this boundary can never be crossed, we can get a glimpse of the other's consciousness by using signs to communicate with each other. Sign systems—language in particular—are capable of transgressing this and other boundaries of the everyday life-world. Signs refer to something that is not immediately given in the situation at hand and to something beyond the actual experience (SCHUTZ & LUCKMANN, 1989, pp.131-147). They are capable of crossing the boundaries of time and space ("little transcendencies"), alter ego ("medium transcendencies") and even our everyday experience ("great transcendencies": dreams, ecstasy, religious experiences etc.). This does not only apply to language but to all forms of human communication: body language, gestures, facial expressions, etc. (SOEFFNER, 1988, p.521). Communication is thus conceived as a means for agents to deal with these transcendencies of the life-world. [7]

Human behavior is understandable and interpretable by other human beings because of its semiotic dimension (SOEFFNER, 1999, p.7). This semiotic characteristic is rooted in the human condition characterized by a lack of instincts (GEHLEN, 1986) and "biological ambiguity" ("biologische Mehrdeutigkeit") (GEHLEN, 1986; PLESSNER, 1965). From such an anthropological perspective we are thus bound to interpret human behavior. In order to constrain the ambiguities inherent in our behavior and our actions we rely on "metacommunicative hints" ("metakommunikative Beigaben"; SOEFFNER, 1999, p.10) to signal the other how to make sense of our behavior.4) Nevertheless, human behavior, actions, and signs point to a horizon of meanings beyond their actual meaning in the concrete interaction. [8]

2.2 The imaginary and its performative mediation

The metacommunicative dimension confers a dramaturgical component to our actions. With FISCHER-LICHTE we assume that this dramaturgical component is vital to the arts and other spheres where the imaginary has to be mediated (FISCHER-LICHTE, 2002). Such spheres cannot be paid justice by simply looking at their referential dimension, i.e. the mere depiction of figures, actions, relations, situations etc. (FISCHER-LICHTE, 2002, p.279). Their dramaturgical component witnessed in performative acts, i.e. the execution of actions and their immediate consequences, is far more important. [9]

Drawing on ISER's literary anthropology we conceive the "imaginary" as something which

"tends to manifest itself in a somewhat diffuse manner, in fleeting impressions that defy our attempts to pin it down in a concrete and stabilized form. The imaginary may suddenly flash before our mind's eye, almost as an arbitrary apparition, only to disappear again, or to dissolve into quite another form" (ISER, 1993, p.3). [10]

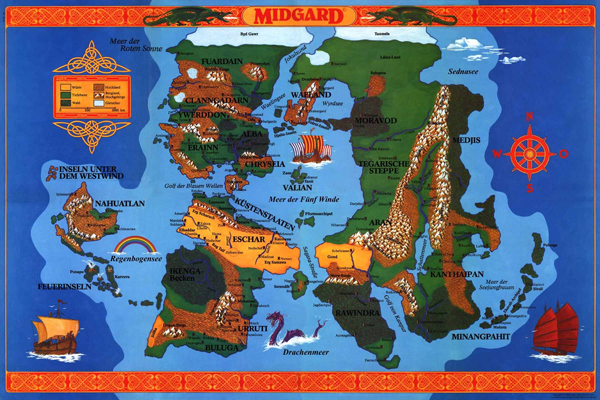

The peculiarity of the imaginary lies in its diffuse character. It can only be grasped through "fictionalizing acts," i.e. in performances realized in a medium. These performative acts are thus media of the imaginary and must not be mistaken for the imaginary itself. The imaginary is a never-ending potentiality of meaning which cannot be fixed once and for all. Beyond the meaning at hand, there is a large variety of other possible interpretations. [11]

3. Fictional Worlds and Interactive Story-telling: Pen and Paper Role-Playing Games

A paradigmatic example for the communication of the imaginary, its performative mediation and emergence are pen and paper role-playing games. The focus therefore lies not on the texts outlining a role-playing plot but on the cooperatively told story established by performative acts. With their performances the players of role-playing games give the imaginary a form to emerge in. From passive recipients of a story they turn into performing actors vital to the progression of the narration. [12]

3.1 Role-playing games—An introduction

The 1970s saw the emergence of pen and paper role-playing games in the U.S. (FINE, 2002, p.14). Today, such games are quite popular in many countries around the globe. Players in such games assume the roles of fictional characters and are engaged in cooperatively telling a story. Usually, participants are seated around a table on which—amongst other things—dice, pen and paper (to record various things) can be found. Hence the name pen and paper role-playing games to distinguish this sort of games from online and live-action role-playing games. One of the players assumes the role of the referee or game master and is responsible for the general plot of the story to be told. Furthermore the game master is responsible for all the actions of the characters not controlled by the remaining players of the game as well as the behavior of the environment of the fictional world. The other players on the other hand are only concerned with the actions of their respective characters. To determine the outcome of difficult actions (e.g. climbing a slippery wall) dice are rolled and interpreted according to rules found in so-called rulebooks, of often several hundred pages of length. These rules not only govern the outcome of actions as described above, but also the "creation" of a player's character as they determine the attributes of a character in the imaginary world. This allows for a great variety of characters ranging from an athletic but uneducated barbarian to a wise and powerful, yet physically weak, wizard or sorceress. A large variety of (different) role-playing game systems with varying rule systems and settings (fantasy, science fiction, horror etc.) are available in specialized game stores. The game master decides on a certain plot prior to a game session and is free to, either chose a prewritten one, that can be bought from a whole range of plots in book form, or he or she can chose a plot that is entirely his or her own creative work. Within the limits defined by the given plot and the rule system players can improvise quite freely. Their actions determine the progression and outcome of the story. Therefore one could speak of it as interactive story-telling. [13]

3.2 Participants, players and characters—GOFFMAN and beyond

The distinction of characters and players, imaginary world of the game and everyday life-world is connected—albeit not identical—to GOFFMAN's distinctions of "gaming situation" and "play," "players" and "participants" (GOFFMAN, 1961). For GOFFMAN a "gaming encounter" is a "focused gathering" were "participants" are focused on—but not necessarily engaged in—a game. There can be by-standers observing the game (mere "participants") and people actually playing the game: "players" (which are at the same time "participants"). While the "gaming situation" encompasses participants and players alike, the actual "play" involves only the players. Each action (body movements, gestures, utterances etc.) can either be made as a participant in the gaming situation (e.g. fetching a drink from the table) or as a player (e.g. rolling a dice). In role-playing games another layer of action has to be distinguished from the two described so far.5) Players enact their characters which are part of an imaginary world. Thus, someone's action could also refer to his or her respective character in the imaginary world, e.g. when speaking in-character ("I am Embros, sorcerer of the northern wastes!").6) The table below clarifies this:

|

World |

Situation |

Person |

Example |

|

everyday life-world |

gaming situation |

participant |

fetching a drink or snack |

|

|

play |

player |

announcing a move |

|

imaginary world |

|

character |

speaking in-character ("I am Embros, sorcerer of the northern wastes!") |

Table 1: Layers of action and their reference in role-playing games [14]

3.3 Fantasy and imaginary worlds

The role-playing groups presented in this article are playing a subtype of pen and paper role-playing games, namely fantasy role-playing games. The oldest pen and paper role-playing game system Dungeons & Dragons—first published in 1974—and most of the recent popular systems can be clearly assigned to this genre. In a very broad sense, this genre can be defined in the following way:

"[...] a narrative is a fantasy if it presents the persuasive establishment and development of an impossibility, an arbitrary construct of the mind with all under the control of logic and rhetoric. [...] to make nonfact appear as fact, is essential to fantasy" (IRWIN, 1976, p.9). [15]

More specifically, in popular culture the term fantasy refers to a genre of trivial literature that is heavily influenced by the novels of J.R.R. TOLKIEN and characterized by its content which involves an imaginary, fictional world in which a quasi-medieval age meets magic and fantastic creatures like dragons, dwarfs and trolls. In fantasy role-playing games players accordingly assume the roles of e.g. wizards, knights or dwarfs and fight against dragons and other fantastic creatures. Plots provided for the players by the game master could therefore include the player's characters rescuing a princess from an evil sorcerer's captivity or escorting a caravan of traders through perilous areas. [16]

4. Hermeneutic Analysis of Visual Data

Our data mainly consists of video recordings of role-playing sessions. So far eleven role-playing sessions have been filmed. The field was approached via a local game store and a press release published in a local newspaper as well as on the homepage of the University of Constance. Four groups replied to these measures. One of the groups were filmed during two different sessions. Depending on the size of the role-playing group and the size of their gaming venue we used one or two video cameras to film the groups in the environment where they usually played—most often this was the living room in one of the player's flats or houses. Another six gaming groups were filmed at several role-playing conventions. Furthermore, we conducted and transcribed several expert interviews with game masters, a game store owner and an editor of a role-playing game publisher. Another kind of data we rely on are the texts, images and material objects used by role-players in their gaming activities. These include a wide range of objects like rulebooks, scenario descriptions, pictures, drawings, sketches, character sheets7), notes scribbled on pieces of paper, and—most relevant for this article—maps. [17]

Our video data are scientific recordings of natural situations (KNOBLAUCH, 2005, p.265). "Natural" should not be mistaken for naïve naturalism. Rather, it describes our relation to the situation filmed. The role-playing sessions would have taken place in a similar way without our presence. Of course, the players are aware of the cameras and that does influence their behavior to a certain extent. However, we still deal with a "gaming situation" (GOFFMAN, 1961), no matter how aware the players are of the cameras. Furthermore, in our experience players soon got used to the cameras and felt comfortable in their gaming experience despite the presence of recording devices. [18]

Single sequences of the video data are transcribed so that each level of communication (gestures, intonation, utterances etc.) of each speaker gets its own tier in a transcription resembling a musical score.8) These sequences are interpreted according to the methodology of sociological hermeneutics (SOEFFNER, 1991, 2004, 2005; HITZLER & HONER, 1997). This approach aims to reconstruct the meaning of interactions and communication by a thorough step-by-step analysis of signs considering both realized and unrealized alternatives of action. While such a "theoretical attitude" assumed by the interpreter is based in the "natural attitude" of the everyday life-world, it differs from the latter insofar as the social scientist is a "disinterested observer," i.e. his or her outlook is different from that of the observed agents (SCHUTZ, 1962, pp.207-259). He or she is not involved in the problems of the agents and not under pressure to act, thus gaining the time for a thorough and reflective analysis (SOEFFNER, 1991, p.265). [19]

These methods of interpretation have proven worthwhile for analyzing texts but—because of the semiotic dimension of all human behavior (see above)—can in principle be applied to all sorts of data (SOEFFNER, 2005, p.166). Consequently, methods of sociological hermeneutics have been successfully applied to the analysis of video data (RAAB, 2002; RAAB & TÄNZLER, 2006). On the diachronic level the focus lies on the immediate context of the sequence in question and the sequence following after that. Deliberately ignoring the context in which a sequence in fact occurred, generates plenty of possible contexts in which the sequence could be found. The aim of such an endeavor is to create a wide range of possible, alternative options of action in order to elaborate the specificity of the actual course of action in comparison to these alternatives and, finally, to answer the question of which social problem is solved by the actual course of action (SOEFFNER, 2004, p.86). [20]

Visual data differs from textual data in one important respect. While transcribed texts of interviews and other forms of dialogue are sequentially structured, visual data is characterized by the simultaneity of various elements.9) Thus, the interpretational endeavor has to take into account that each single frame of our video data is in itself a rich and complex datum. In our case, the setting of the game can be analyzed: How are the players seated with respect to each other? What kind of milieu do they live in? What kind of accessories are situated/present on the table? In our analysis we draw on visual hermeneutics—as proposed by BRECKNER (2003)—and subdivide the image into several segments and interpret them one by one without taking their actual context—i.e. the other segments of the image—into account. These interpretations are reassessed in light of the other segments and are finally put into the context of the whole frame. Additionally, we temporarily (and deliberately) ignore one level of communication during the interpretation (one time the visual, another time the auditory) to yield a broad range of interpretations which are also reassessed in light of further data and finally condensed into a single interpretation. This has the positive side effect of enabling very careful observations. [21]

4.3 Cartographic interpretations

Maps as an object of inquiry are quite well known in historical research (see BAGROW & SKELTON, 1966; HARVEY, 1980; HARLEY & WOODWARD, 1987; EDSON, 1997; VÖLKEL, 2007). In sociology, however, they are only sparsely mentioned as an object of inquiry (for an exception see PSATHAS, 1979), although scholars of other disciplines in the humanities seem less reluctant to deal with them (BUCI-GLUCKSMANN, 1996; COSGROVE, 1999; TURCHI, 2004; VELMINSKI, 2006; STOCKHAMMER, 2001, 2007). [22]

As with other visual data there is no single canonical method of analysis. Again, we draw on sociological hermeneutics (SOEFFNER, 2004) to approach our object in question. With maps we have to rely on visual hermeneutics as outlined by BRECKNER (2003). As with the interpretation of frames of video data, we subdivide the map into segments (the key, the compass, mountainous areas etc.) and interpret these initially without taking the actual context into account. Finally, the segments are reintegrated into the context of the whole map and the meanings generated beforehand are contrasted with the actual meaning in light of the actual context. Since maps are employed in the actual play of role-playing games, the analysis of maps has to be supplemented by the video analysis of role-playing interactions in which they are used. Maps (and other material objects), language, as well as gestures, interact with each other in communication—only by considering all of these elements can we get a thorough grasp of the meaning emerging in interactions (HERBRIK & RÖHL, 2007). [23]

5. Cartography of Imaginary Worlds—Interpreting Maps in Role-Playing Games

The following interpretations of maps and interactions recorded on video were taken from two role-playing groups. Each group is introduced upon first mention by an image containing the players' names. Images and stills are included to supplement the text where necessary. The beginning of a section contains a video sequence when relevant. [24]

5.1 Where?—Maps and situating oneself in the world

Video 1: Maps and situating oneself in the world

Figure 1: Overview of players in group [25]

In the first still (Fig. 2) Carsten points to a point on the map on the table in front of him while simultaneously asking: "Are we here then?" Such a question would seem rather strange without the accompanying gesture and map. "Here" is a deictic term and as such has to refer to a certain area or space. While "here" could be used tacitly and thus refer to the place where speaker and recipient are located in the face-to-face situation, it would render the question trivial and the other agents would question the relevance of this utterance.

Figure 2: Group I-1 [26]

Thus, the question only becomes meaningful in combination with a deictic gesture10) aimed at a map. Consequently, two types of situations come to mind as possible contexts. First, we could be dealing with a situation where the speaker suffers from amnesia and wakes up from a coma or from a night's sleep after a drunken night. Second, this could be a situation where the speaker has to come to terms with a new surrounding. The question "Are we here then?" could be the stereotypical question of a traveler wielding a map at locals. Similarly, participants of an expedition could assure themselves of their position in such a way. Both interpretations (amnesia, localizing oneself in new surroundings) are characteristic for role-playing games. In the imaginary world, for characters to be able to act in a certain place, this place has to be created first in order to allow players to situate their characters in it. As most scenarios cannot be completed in a single gaming session, players have to recall past events and the whereabouts of their characters in the beginning of most sessions. In other words, the knowledge of players and that of their characters, for whom there are no temporal discontinuities, has to be synchronized. Thus, the question of one's place inside the gaming world is one of the first questions asked by players at the start of a session. In this case, it is asked with the help of a map. Furthermore, role-players are also travelers and explorers in a world alien to them. Although many landscapes might be familiar to their characters, they discover new terrain as players, i.e. as inhabitants of their everyday life-world in the 21st century.

Figure 3: Group I-2 [27]

Mischa, the game master, gives an answer to Carsten's question: "You passed Norwards Gate. You are now here somewhere!" (Fig. 3) While he talks, his index finger follows an imaginary line envisioning this path, until he stops at a specific point on the map. Then Carsten gives way to Mischa's index finger. However, Mischa points to another place on the map than Carsten did. Carsten in turn adopts that correction. Mischa is the expert who is in a position to answer Carsten's question. Not only is Carsten's line of sight directed at Mischa, he also pulls his index finger back, thus showing that he accepts Mischa as someone giving answers. Carsten's lack of knowledge (either because he cannot remember where the last session finished or the area is alien to him) can thus be augmented by Mischa's superior geographical knowledge of the imaginary world. [28]

Gunter adds another detail to this simple spatial information: "There's Eaglestone, the small fortress." His "there" shows that there are two levels involved in the "play" of role-playing games (see Section 3.2). Carsten and Mischa used "here" to refer to a place in the imaginary game world and were thus taking the perspective of their characters. Gunter's "there," however, reminds us that the players can distance themselves from the game world: the "here" becomes a "there." Players are then firmly rooted in their everyday life-world. Like Gunter, Carsten then supplements the game master's simple naming of places and his rather technical description of spatial relations: "Beyond that there's only barbarians' land!" The additions of Gunter and Carsten show that the question of place is far more than a simple technical question. The imaginary places are endowed with meaning. They assume cultural values in the fictitious world of the game which entangle them firmly in the web of meaning of the imaginary world. [29]

Furthermore, the map allows Mischa to visualize past events topographically in the players' story ("You passed Norwards Gate"). Enabling players to situate themselves, the map serves as basis of background knowledge which is activated at the beginning of a session. As soon as it is negotiated the background knowledge serves as shared and "taken for granted" (SCHUTZ & LUCKMANN, 1974, pp.8-15) knowledge underlying the following interactions "until further notice" (ibid., p.8). Only if disagreement arises does it become the focus of discourse again (see Section 5.4). [30]

5.2 Maps and (narrative) relevance

Figure 4: Map depicting the region where the adventure takes places11) [31]

The map of the area in which the players are situated and which the players drew themselves is based on a map of the area which is only known to the game master (see Fig. 4). This map depicts various places: a mountain which fills up almost the whole upper half of the picture; a plain, a compass as well as roads which connect several graphically encircled places like a fortress, caves and settlements. Instead of a simple, plain and schematic map, which merely illustrates graphical relations between abstract points, this map is rich in iconic detail. Grass is growing in the plains, the compass rose reminds us of medieval engravings, the mountains are mimetic images of actual mountains and not schematic pictograms, and the encircled places are enlarged as if watched through a looking glass. Inside of these enlarged areas we see—with the exception of the "Orc-Höhlen" (orc caves)—iconic representations of various places or buildings situated there. This representational style can be frequently found in tourist maps. What maps of role-playing games and tourism have in common is that in both contexts we want to be able to locate ourselves and at the same time specific places are highlighted and endowed with relevance. By highlighting some places one conveys that there is something to be seen, done and experienced at these places. Because of this a game master has to carefully select when and which information he or she reveals. Usually, such information is given to players when their characters have the same information at hand. Since such highlighting is always relevant for the narrative in role-playing games, the tension of the story would suffer if the players knew such information beforehand.12) The abundance of iconic elements in the maps found in role-playing games points to the aesthetic dimension of mediating the imaginary. The iconic elements help visualizing the imaginary world in a much easier way than a pure schematic map which only depicts abstract lines between numbered points. [32]

5.3 Cartographic possibilities and restrictions—The "view from nowhere" and cartographic determinations

The possibility of locating oneself with the help of a map is tied to two requirements. The first requirement is the cartographic perspective of maps. While classical pictures of the renaissance, which are composed according to linear perspective, open a "window" into the world and assign an ideal standpoint to the spectator, maps enable a "view from nowhere" ("vue de nulle part"; BUCI-GLUCKSMANN, 1996, p.33). The spectator's standpoint is not clearly determined, his or her point of view is "eliminated." It is exactly this which opens up interpretations from which the spectator can locate himself in any place on the depicted territory. The "view from nowhere" is at the same time potentially a gaze from every possible position which includes an imagined gaze from within the territory of the map. [33]

The second requirement lies in the tension maps typically inhibit. On the one hand they determine the spatial dimensions of a territory in a relatively clear and intersubjectively intelligible way, on the other hand they are a selection of certain aspects of the territory. The map does not pretend to be a naturalistic image of a territory. Instead, map and territory are related to each other by the principle of correspondence. The map is not the territory it represents, but resembles it structurally (KORZYBSKI, 1958, p.58). Thus, the cartographic representation determines the player's action insofar as their characters cannot move around the territory in every possible way. To reach "Clanngadarn" from "Alba" one has to cross a mountain and will probably follow the road from "Twineward" via "Norwardstor" ("Norwards Gate") and "Grenzfestung Eaglestone" ("Fortress Eaglestone") (see Fig. 4). The map is however still open to numerous interpretations. Most importantly, most maps do not define the position of the recipient and other agents.13) Thus, one can imagine oneself in various places on the map, taking a wide range of possible routes.14) [34]

5.4 Where to?—Maps and planning actions

Video 2: Maps and planning actions

|

|

|

Figure 5: Overview of players in group II

|

|

|

Figure 6: Group II-1 [35]

An example taken from another role-playing group (group II) shows that maps can obtain immediate relevance in certain situations in the game. Phillip's character is infiltrating the camp of the villain and secretly tries to reach one of the tents. Phillip is not sure how his character can get there without being caught by Orloff's guards. His memory of the camp deceives him: "They [the guards; T.R. / R.H.] are beneath the camp?" Andy, the game master, reminds him that he owns a map of the camp. Phillip understands this as invitation to consult this map in order to clarify the spatial dimensions of the camp. Thus, he and his fellow gamers are looking for the map until Phillip discovers it next to his seat (see Fig. 6). Reading the map for some time on his own, he is finally joined by Thorsten. Thorsten points to the map and describes the fictitious space surrounding their characters (see Fig. 7). Thorsten too knows maps as a means of orientation in the world of the game. The game master does not have to correct Phillip's imagination of the fictitious space explicitly, mentioning the map is sufficient. The map is thus—from the perspective of BERGER's and LUCKMANN's sociology of knowledge (1987)—an objectivated means of localization and as such able to support and even substitute linguistic means of localization—as such the map belongs to the realm of "visual knowledge" (SCHNETTLER & PÖTZSCH, 2007). Furthermore, the example shows that the background knowledge activated by maps and other means can become an issue. If a player's memory and his or her character's knowledge and perception diverge, a map can help to synchronize these diverging levels and make them consistent again.

Figure 7: Group II-2 [36]

Finally, Phillip puts the map away again (see Fig. 8). Using the newly acquired knowledge of the spatial dimensions of the map he can realize his plan and sneak past the guards. This episode shows how relevant maps can be for actions in the gaming world. Where am I and where do I have to go? Which way do I take? How can I avoid being seen by my adversaries? How can I take them by surprise?

Figure 8: Group II-3 [37]

5.5 Inscribing oneself and making tactical decisions

The analysis of the map in question confirms these observations (see Fig. 9). At a later point in the game the players utilize the map to determine their way through the camp and finally defeat the villain Orloff. In order to do this the players trace the path their characters take with a pencil on the map. The path described by the drawn lines leads from a blockhouse to the woods behind it. The numbers on the map denote different relevant points in a similar vein to the map in Fig. 4. Specific places are singled out and marked as relevant. By referring to these numbers in the game master's booklet describing the scenario and the plot the authors of the scenario can easily denote places and give detailed descriptions of them. Here too, specific places are marked as important points in the narration. During the course of the game, players and the game master can mark further places by encircling places (like for example no. 3) with a pencil, thus singling out a place.

Figure 9: Map of Orloff's camp15) [38]

The map is not drawn true to scale. "Read literally" the hay wagon is too large. Still, group II employs this map of a scenario downloaded from the Internet. It fulfills its purpose: Players can locate their characters in the imaginary world, make tactical decisions and act in the game world. Because the map's relation to its territory is one of correspondence and not a naturalistic image, players are not confused by this depiction of spatial relations. What is striking about this map is its abundance of iconic elements. Parts of the map look like an image construed in bird's eye view. The visual imagination of that place of action is enhanced in this way. At the same time there are clues that we are dealing with a cartographic representation. The trees are depicted schematically, some proportions are awkward, and in the upper right corner we find an arrow clearly marked with one cardinal direction ("F" stands for "Firun," the north of this imaginary world; although it bears a different name, it is like our north associated with cold and ice). [39]

5.6 Wherein?—Maps and the creation of a fictitious world

But maps are not only an immediate part of the gaming situation of role-playing games, they are also an integral part of the rule and source books of the varied role-playing game systems. These maps are not necessarily used directly in a gaming session. Rather, they depict whole regions, continents, and even the entire fictitious world. World maps in particular are seldom used in gaming sessions. Still, most role-playing game systems know them. What is the purpose of these maps in role-playing games then? A close look at the history of the fantasy genre proves to be insightful. In his essay "On Fairy-Stories" (1983 [1947]), J.R.R. TOLKIEN, one of the founders of the genre, developed the idea of a "sub-creation," i.e. the creation of a coherent, consistent and plausible "secondary world."16) He realized this idea in his popular novel "The Lord of the Rings" (1979 [1954/55]), where he pursued the endeavor of creating a modern myth and brought the fictitious world "Arda" into being endowing it with its own history, mythology, people and completely worked out languages (e.g. Elvish) and geography. A large foldout map is an important part of the novel. It enables us not only to envision the adventures and voyages of the protagonists, but—more importantly—is also part of TOLKIEN's "sub-creation." With its help readers are willing to confer an "accent of reality" (SCHUTZ & LUCKMANN, 1974, pp.22-25) to TOLKIEN's "secondary world." A consistent world is presented which the novel constantly refers to. Furthermore, the map depicts regions which are not immediately relevant for the story told and thus convey the impression that the world presented herein exists beyond the novel.17) [40]

Most role-playing games use fantasy settings and as such inherit TOLKIEN's ideas and creations, especially his most famous novel "The Lord of the Rings" (1979 [1954/55]). TOLKIEN's novels made a significant impact on the fantasy genre and many works of fictions after them inherit his ideas to a certain degree. Consequently, the idea of creating a plausible and self-contained fictitious "secondary world" can be found in role-playing game publications, but also among players and game masters. An author of role-playing games interviewed by us describes his desire to create a complex world:

"The world has to be in the heads of the creators in so much detail that I can write it down and others lacking the opportunity to talk to the creators […] are able to roam this world. That means that the level of detail has to be enormous."18)

(Game author Dennis) [41]

One of the game masters we interviewed deals with the problem posed by conveying worlds created by others in the first place in the following way:

"I have to come to grips with the world to such an extent that I know for sure how the world reacts." 19)

"If I present the world to them [the players; T.R. / R.H.], I have to know how it reacts. And of course, it happens that they leave the […] plot […], but it is out of the question that they get the impression that the world ends there." 20)

"They [the players; T.R. / R.H.] should have the impression that the world engulfs and surrounds them everywhere." 21)

(Game master Marc) [42]

In order to give players the impression "that the world engulfs and surrounds them," i.e. to create an entire plausible world, descriptions of the fictitious world are consequently very detailed and elaborate. The world maps are bound to this "sub-creation." They are a means of creating a plausible "secondary world." Both type of maps, TOLKIEN's and that of the role-playing games, can be characterized by the specific relation of map and territory described by BAUDRILLARD in his account of postmodern relations of sign and signified: "The territory no longer precedes the map, nor does it survive it. It is nevertheless the map that precedes the territory—precession of simulacra—that engenders the territory […]" (BAUDRILLARD 2001, p.1; italics in original). This certainly holds true for imaginary maps. For the reader or the player the map creates an idea of the territory to be imagined. Interesting enough, this only works because we usually assume a traditional relation of map and territory. Because there is a map depicting an area, we conclude that there is a corresponding territory somewhere which was drawn in the map accordingly.22) [43]

5.7 Maps in-between game world and everyday life-world

Maps of the world and specific regions can be found in the rulebooks at points where the world is described and the reader is introduced to this world. They are gates to the worlds created by the authors of role-playing publications. It is noticeable that both TOLKIEN's maps and that of fantasy role-playing games combine a pseudo-medieval23) visual appearance with modern conventions of cartography.24) Illustrations of mythical creatures (dragons, sea snakes) and medieval ships, pseudo-Celtic ornaments and lyrical names ("Rainbow Sea" etc.) turn the world map of Germany's first role-playing game Midgard into a cartographic representation which is not only a map depicting the world but also a map from that world (see Fig. 10). As such the map is directed at the player's character and part of the game world. The key, the exact scale, the cardinal directions (with north, east, west, and south), the compass, the orientation to the north, all this points to the fact that we are dealing with a map which is part of the everyday life-world of the players. The map has to be directed at them too, they have to understand and use it. Therefore, the author of such a map has to rely on conventions understandable and recognizable by agents of the 21st century. Furthermore, these maps show geographic features which resemble that of our own world.25) There are rivers flowing into the ocean, mountains, polar ice caps, island groups, and deserts. All of these could be found on our earth—although combined in a completely different way. The map is thus situated in-between fictitious gaming world and players' everyday life-world. It is exactly this intermediate position of role-playing maps that enables players to imagine a plausible and coherent fictitious world—a "secondary world" in the vein of TOLKIEN. They engender a territory which they precede.

Figure 10: Map of "Midgard"26) [44]

6. Maps and the Imaginary—Concluding Remarks

Cartographic representations fulfill an important role in the mediation of the imaginary. Not only do they help to visualize spatial dimensions of the imaginary world and to orientate oneself in that world, they also serve to give plausibility to the world as a whole. Maps are important mnemotechniques helping the players to synchronize their memory with that of their characters. Furthermore, they are means of locating oneself and lend the characters a meaningful place in the fictitious gaming world. With their help players can decide on their course of actions in tactical situations and plan future actions. Maps are finally a way of creating a consistent and plausible fictitious world as a whole: A world which "engulfs and surrounds" (game master Marc) the characters controlled by the players. In that regard maps in role-playing games do not fundamentally differ from maps of the everyday life-world. Such maps also remind us of past voyages or enable orientation in alien places. They show us the shortest route around construction sites and thus allow us to plan the routes we take. Finally, they too are a means of creation: an architect drawing a plan of a house to be built creates a territory (yet) lacking a counterpart in the material world. Even our world is not immediately given to us as a whole. Thanks to globes and world maps we know how to imagine it. The analysis of maps used in role-playing games thus can tell us something about maps in other contexts. [45]

We would like to thank Hans-Georg SOEFFNER for his advice on an early draft and our student assistants André BECKERSJÜRGEN, Sebastian HOGGENMÜLLER and Tim LORENZ for their help and assistance in writing this article. Finally, we are indebted to the German Research Foundation (Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft, DFG) which made this article possible by funding the research project "Kommunikative Vermittlungsstrategien des Imaginären" ("Communicating the Imaginary"). Special thanks belong to Melanie HOCHSTÄTTER for proofreading our English.

1) The project is funded by the German Research Foundation (Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft, DFG). <back>

2) More on this kind of games in Section 3.1. <back>

3) For an overview of "maps of the imaginary" in literature see TURCHI (2004) and STOCKHAMMER (2007). <back>

4) See also BATESON's account of metacommunication (1972) and GOFFMAN's analysis of communicative frames (1974). <back>

5) Similarly, in his classic study on role-playing games Gary Alan FINE (2002, pp.185-187) draws on another one of GOFFMAN's concepts and distinguishes three "frames": the primary framework of the real world, the game context and the level of characters. <back>

6) One could even distinguish yet two more layers. First, with regard to our second layer, it makes a difference if a player is referring to the imaginary world by asking a question pertaining to the rule system, or if he or she is announcing a move of his or her character in a performative act ("I am going north!"). With regard to the former it is doubtful whether this kind of activity can be called "play" at all. Secondly, we witnessed a tendency of players to play around with the possibilities of the imaginary world itself. Often players would come up with actions and utterances of their characters which were not meant to be meaningful performative (gaming) acts. Rather, they were imagining actions their imaginary characters might do, often exaggerating their actions and speaking in an ironic tone. These "what if" utterances were employed jokingly most of the time, often to the amusement of fellow players. We call this layer "conjunctive play," because of its "what if" character. For the sake of simplicity we would like to refrain from referring to these other layers for the purposes of this article. <back>

7) Character sheets consist of one or more pieces of paper on which the attributes, the background and the possessions of one's character are recorded. <back>

8) We use the EXMARaLDA editor developed by linguists of the University of Hamburg (for an overview see SCHMIDT & WÖRNER, 2005). Our transcription system draws heavily on the HIAT system (EHLICH & REHBEIN, 1981). <back>

9) See LANGER's distinction of "discursive" and "representational symbolism" (1967, pp.79-102). <back>

10) For a thorough analysis of gestures in role-playing games see HERBRIK and RÖHL (2007). <back>

11) Taken from the scenario "Der singende Tod" by courtesy of the publisher DDD Verlag. <back>

12) As all games, role-playing games too can be characterized as "uncertain activity" (CAILLOIS, 1961, p.7), an activity with an uncertain ending, thus creating the tension necessary to engage players. <back>

13) An exception are tourist maps mounted to a stand. Since one cannot take them with them, one's position can be defined permanently. <back>

14) Insofar, a map can be considered as diagram in the broadest sense, as a system of graphical relations (BOGEN & THÜRLEMANN, 2003). Drawing on C.S. PEIRCE, Steffen BOGEN and Felix THÜRLEMANN conceive diagrams as signs which relate to the objects represented by them through analogy. The relations of their parts resemble that of the represented objects. On the one hand, diagrams open up a number of interpretations exceeding what the "author" of the diagram initially conceived. On the other hand, they determine certain relations limiting the number of interpretations. <back>

15) By courtesy of the author Matthias FREUND, taken from a copy of the players' printout. <back>

16) For the creation of plausible "secondary worlds" in fantasy literature see NESTER (1993). <back>

17) For maps and their relevance to TOLKIEN's literary work see DROUT (2007), entry "Maps." <back>

18) German original: "Die Welt muss so detailliert in den Köpfen der Macher existieren, dass ich sie aufs Papier bringen kann und dass andere, die keine Möglichkeit haben, mit dem Schöpfer dieser Welt direkt zu kommunizieren, [...] in der Lage sind, in dieser Welt sich zu bewegen. Das heißt, die Detailtiefe muss enorm sein." <back>

19) German original: "Ich muss mich in der Welt so zurechtfinden, dass ich mir absolut sicher bin, wie die Welt reagiert." <back>

20) German original: "Wenn ich ihnen [den Spielern; T.R. / R.H.] ne Welt präsentiere, muss ich wissen, wie die reagiert. Und klar, des kommt vor, dass sie den [...] Plot verlassen oder so was, aber es darf nich so sein, dass sie deswegen dann das Gefühl haben, da hört die Welt auf." <back>

21) German original: "Sie [die Spieler; T.R. / R.H.] sollen das Gefühl haben, dass die Welt sie überall einhüllt und auffängt." <back>

22) Of course, readers of fantasy literature and role-players alike know that this is an imaginary territory. <back>

23) Umberto ECO refers to that phenomenon as "neomedievalism" to describe a renewed interest in the Middle Ages and the popular—albeit somewhat bizarre—perspective on that era (1986, p.63). For an account of this "neomedievalism" in fantasy literature and games see SELLING (2004). <back>

24) For an extensive history of Western cartography see BAGROW and SKELTON (1966). Unlike other maps relating to the imaginary (e.g. in literature), maps of role-playing games and that of TOLKIEN's novels follow the conventions of modern cartography and Euclidian geometry without questioning them (STOCKHAMMER, 2001). <back>

25) Drawing on C.S. PEIRCE, Winfried NÖTH therefore states that imaginary maps have two "dynamic objects" ("dynamische Objekte"), one of them situated in the geographic and the other in the imaginary world (NÖTH, 1998, p.33). <back>

26) By courtesy of the publisher "Verlag für F&SF-Spiele," retrieved from the publisher's homepage on the 17th of February 2008. <back>

Bagrow, Leo & Skelton, Raleigh A. (1966). History of cartography. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Bateson, Gregory (1972). Steps to an ecology of mind: Collected essays in anthropology, psychiatry, evolution, and epistemology. Chicago: University of Chicago.

Baudrillard, Jean (2001). The precession of simulacra. In Jean Baudrillard (Ed.), Simulacra and simulation (pp.1-42). Ann Arbor: The University of Michigan Press.

Berger, Peter L. & Luckmann, Thomas (1987). The social construction of reality. A treatise in the sociology of knowledge. Harmondsworth: Penguin.

Bogen, Steffen & Thürlemann, Felix (2003). Jenseits der Opposition von Text und Bild. Überlegungen zu einer Theorie des Diagramms und des Diagrammatischen. In Alexander Patschovsky (Ed.), Die Bildwelt der Diagramme Joachims von Fiore: Zur Medialität religiös-politischer Programme im Mittelalter (pp.1-22). Ostfildern: Thorbecke.

Breckner, Roswitha (2003). Körper im Bild. Eine methodische Analyse am Beispiel einer Fotografie von Helmut Newton. Zeitschrift für qualitative Bildungs-, Beratungs- und Sozialforschung, 1, 33-60.

Buci-Glucksmann, Christine (1996). L'œil cartographique de l'art. Paris: Galilée.

Caillois, Roger (1961). Man, play, and games. New York: Free Press of Glencoe.

Cosgrove, Denis (Ed.) (1999). Mappings. London: Reaktion Books.

Drout, Michael D.C. (2007). J.R.R. Tolkien Encyclopedia: Scholarship and critical assessment. New York: Routledge.

Eco, Umberto (1986). Dreaming of the middle ages. In Umberto Eco (Ed.), Travels in hyperreality. Essays (pp.61-72). London: Picador.

Edson, Evelyn (1997). Mapping time and space: How medieval mapmakers viewed their world. London: British Library.

Ehlich, Konrad & Rehbein, Jochen (1981). Zur Notierung nonverbaler Kommunikation für diskursanalytische Zwecke. In Peter Winkler (Ed.), Methoden der Analyse von Face-to Face-Situationen (pp.302-329). Stuttgart: Metzler.

Fine, Gary Alan (2002). Shared fantasy: Role-playing games as social worlds. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Fischer-Lichte, Erika (2002). Grenzgänge und Tauschhandel. Auf dem Wege zu einer performativen Kultur. In Uwe Wirth (Ed.), Performanz: Zwischen Sprachphilosophie und Kulturwissenschaften (pp.277-300). Frankfurt/M.: Suhrkamp.

Gehlen, Arnold (1986). Der Mensch: Seine Natur und seine Stellung in der Welt. Wiesbaden: Aula-Verlag.

Goffman, Erving (1961). Encounters: Two studies in the sociology of interaction. Indianapolis: Bobbs-Merrill.

Goffman, Erving (1974). Frame analysis: An essay on the organization of experience. London: Harper and Row.

Harley, John B. & Woodward, David (1987). The history of cartography, Vol. I: Cartography in prehistoric, ancient, and medieval Europe and the Mediterranean. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press.

Harvey, Paul D.A. (Ed.) (1980). The history of topographical maps: Symbols, pictures and surveys. London: Thames and Hudson.

Herbrik, Regine & Röhl, Tobias (2007). Visuelle Kommunikationsstrategien im Zusammenspiel. Gestik im Fantasy-Rollenspiel. sozialer sinn, 8(2), 237-265.

Hitzler, Ronald & Honer, Anne (1997). Sozialwissenschaftliche Hermeneutik: Eine Einführung. Opladen: Leske + Budrich.

Irwin, William Robert (1976). The game of the impossible: A rhetoric of fantasy. Urbana, Chicago: University of Illinois Press.

Iser, Wolfgang (1993). The fictive and the imaginary: Charting literary anthropology. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press.

Knoblauch, Hubert (2005). Video-Interaktions-Sequenzanalyse. In Christoph Wulf & Jörg Zirfas (Eds.), Ikonologie des Performativen (pp.263-275). München: Wilhelm Fink Verlag.

Korzybski, Alfred (1958). Science and sanity: An introduction to non-Aristotelian systems and general semantics. Lakeville, Conn.: Institute of General Semantics.

Langer, Susanne K. (1967). Philosophy in a new key: A study in the symbolism of reason, rite, and art. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press.

Nester, Holle (1993). Shadows of the Past: Darstellung und Funktion der geschichtlichen Sekundärwelten in J. R. R. Tolkiens The Lord of the Rings, Urslua K. Le Guins Earthsea-Tetralogy, Patricia McKillips Riddle-Master-Trilogy. Trier: WVT.

Nöth, Winfried (1998). Kartosemiotik und das kartographische Zeichen. Zeitschrift für Semiotik, 20(1-2), 25-39.

Plessner, Helmuth (1965). Die Stufen des Organischen und der Mensch: Einleitung in die philosophische Anthropologie. Berlin: de Gruyter.

Psathas, George (1979). Organizational features of direction maps. In George Psathas (Ed.), Everyday language. Studies in ethnomethodology (pp.203-225). New York: Irvington.

Raab, Jürgen (2002). "Der schönste Tag des Lebens" und seine Überhöhung in einem eigenwilligen Medium. Videoanalyse und sozialwissenschaftliche Hermeneutik am Beispiel eines professionellen Hochzeitsvideofilms. sozialer sinn, 3, 469-495.

Raab, Jürgen & Tänzler, Dirk (2006). Video hermeneutics. In Hubert Knoblauch, Bernt Schnettler, Jürgen Raab & Hans-Georg Soeffner (Eds.), Video-analysis: Methodology and methods. Qualitative audiovisual data analysis in sociology (pp.85-96). Frankfurt/M.: Lang.

Schmidt, Thomas & Wörner, Kai (2005). Erstellen und Analysieren von Gesprächskorpora mit EXMARaLDA. Gesprächsforschung—Online-Zeitschrift zur verbalen Interaktion, 6, 171-195.

Schnettler, Bernt & Pötzsch, Frederik S. (2007). Visuelles Wissen. In Rainer Schützeichel (Ed.), Handbuch Wissenssoziologie und Wissensforschung (pp.472-484). Constance: UVK.

Schutz, Alfred (1962). On multiple realities. In Alfred Schutz, Collected papers, Vol. I: The problem of social reality (pp.207-259). The Hague: Nijhoff.

Schutz, Alfred & Luckmann, Thomas (1974). The structures of the life-world, Vol. I. London: Heinemann.

Schutz, Alfred & Luckmann, Thomas (1989). The structures of the life-world, Vol. II. Evanston: Northwestern University Press.

Selling, Kim (2004). "Fantastic neomedievalism": The image of the middle ages in popular fantasy. In David Ketterer (Ed.), Flashes of the fantastic (pp.211-218). Wesport, Conn.: Praeger.

Soeffner, Hans-Georg (1988). Rituale des Antiritualismus—Materialien für Außeralltägliches. In Hans Ulrich Gumbrecht & Ludwig K. Pfeiffer (Eds.), Materialität der Kommunikation (pp.519-546). Frankfurt/M.: Suhrkamp.

Soeffner, Hans-Georg (1991). Verstehende Soziologie und sozialwissenschaftliche Hermeneutik—Die Rekonstruktion der gesellschaftlichen Konstruktion der Wirklichkeit. Berliner Journal für Soziologie, 2, 263-269.

Soeffner, Hans-Georg (1999). Kommunikation. In Jo Reichertz & Norbert Schröer (Eds.), auslegen 03. Essener Schriften zur Sozial- und Kommunikationsforschung (pp.7-17). Essen: Universität-Gesamthochschule Essen.

Soeffner, Hans-Georg (2004). Auslegung des Alltags—Der Alltag der Auslegung: zur wissenssoziologischen Konzeption einer sozialwissenschaftlichen Hermeneutik. Constance: UVK.

Soeffner, Hans-Georg (2005). Sozialwissenschaftliche Hermeneutik. In Uwe Flick, Ernst von Kardorff & Ines Steinke (Eds.), Qualitative Forschung: Ein Handbuch (pp.164-175). Reinbek: Rowohlt.

Stevenson, Robert Louis (1982 [1883]). Treasure island. London: Gollancz.

Stockhammer, Robert (2001). "An dieser Stelle." Kartographie und die Literatur der Moderne. Poetica, 33, 273-306.

Stockhammer, Robert (2007). Kartierung der Erde: Macht und Lust in Karten und Literatur. München: Fink.

Tolkien, John R.R. (1979 [1954/55]). The lord of the rings. London: Allen Unwin.

Tolkien, John R.R. (1983 [1947]). On fairy-stories. In Christopher Tolkien (Ed.), The monsters and the critics and other essays. London: Allen & Unwin.

Turchi, Peter (2004). Maps of the imagination: The writer as cartographer. San Antonio: Trinity University Press.

Velminski, Wladimir (2006). е π rраφ—Mysterien der Kartographie. In Horst Bredekamp & Pablo Schneider (Eds.), Visuelle Argumentationen: Die Mysterien der Repräsentation und die Berechenbarkeit der Welt (pp.225-252). München: Fink.

Völkel, Markus (2007). Hugo Grotius' Grollae obsidio cum annexis von 1629: Ein frühneuzeitlicher Historiker zwischen rhetorischer (Text) und empirischer Evidenz (Kartographie). In Gabriele Wimböck, Karin Leonhard & Markus Friedrich (Eds.), Evidentia: Reichweiten visueller Wahrnehmung in der Frühen Neuzeit (pp.83-110). Berlin: Lit.

Videos

Video_1: http://medien.cedis.fu-berlin.de/stream01/cedis/fqs/3-09/RH_video1.FLV (425 x 355)

Video_2: http://medien.cedis.fu-berlin.de/stream01/cedis/fqs/3-09/RH_video2.FLV (425 x 355)

Tobias RÖHL is research assistant in the project "Kommunikative Vermittlungsstrategien des Imaginären" ("Communicating the Imaginary") at the Department of History and Sociology at the University of Constance. His dissertation deals with diagrams and maps and their relevance for human practice in different fields of action. In his previous research he investigated the symbolic dimension of roadside memorials. His current research interests include the sociology of knowledge, phenomenology, methodology of the social sciences and visual sociology.

Contact:

Tobias Röhl, M.A.

Department of History and Sociology

University of Constance

78547 Constance, Germany

Tel.: +49 (0)7531-88-4162

Fax: +49 (0)7531-88-3194

E-mail: tobias.roehl@uni-konstanz.de

URL: http://www.uni-konstanz.de/soziologie/fg-wiss/phpwebsite/

Regine HERBRIK is research assistant in the project "Kommunikative Vermittlungsstrategien des Imaginären" ("Communicating the Imaginary") at the Department of History and Sociology at the University of Constance. In her dissertation she investigates communicational interactions in face-to-face-encounters (i.e. pen-and-paper-role-playing games) drawing on frame analysis, sociological hermeneutics and video interaction analysis. Previously she worked as editor for the German sociological review journal "Soziologische Revue" and edited a special edition on the sociology of knowledge for that journal with Hans-Georg SOEFFNER. Her current research interests are philosophical (and literary) anthropology, theories of play and game, sociology of knowledge and the interrelation between different modes of communication.

Contact:

Regine Herbrik, M.A.

Department of History and Sociology

University of Constance

78547 Constance, Germany

Tel.: +49 (0)7531-88-2165

Fax: +49 (0)7531-88-3194

E-mail: regine.herbrik@uni-konstanz.de

URL: http://www.uni-konstanz.de/soziologie/fg-wiss/phpwebsite/

Röhl, Tobias & Herbrik, Regine (2008). Mapping the Imaginary—Maps in Fantasy Role-Playing Games [45 paragraphs]. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung / Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 9(3), Art. 25, http://nbn-resolving.de/urn:nbn:de:0114-fqs0803255.