Volume 10, No. 3, Art. 7 – September 2009

Cacophony: Ways to Preserve the Complexity of Subjects in the Research Presentation

Jacob Thøgersen

Abstract: The main objective of this paper is to present and argue for the relevance of a non-linear, interactive presentation of results of a qualitative investigation of language attitudes. After introducing the layout of the project, the conclusions of "traditional" qualitative analyses, i.e. a rhetorical and a discourse analysis are presented. Analyses show that although informants share common traits in both the exposition of their attitudes as well as their arguments for supporting a particular attitude, the overall picture is one of confusion rather than order. It is proposed that the challenge of the project is to find a mode of presentation which does not sweep this confusion under the rug, but rather holds it up as an interesting find in itself. As an attempt to confront this challenge, an interactive online presentation is presented.

Key words: multi-medial presentation; texts; reflexivity; attitudes

Table of Contents

1. Introduction

2. Data and Initial Analyses

2.1 Rhetorical analyses

2.2 Discourse analysis

3. Anti-essentialist Analysis

3.1 The text which isn't a text

3.2 Cacophony—to lend voice to the people

3.3 Layout

3.3.1 The question

3.3.2 The main screen

3.3.2.1 The answers

3.3.2.2 The question mark

3.3.2.3 The exclamation point

3.3.2.4 The full stop

3.3.3 The attitude answers

3.3.4 The newspaper headline

3.3.5 The narrative of the blind men and the elephant

4. Technical Disclaimer

In 2001, The Nordic Language Council initiated a large-scale comparative investigation of the impact of English on Nordic speech communities (GRAEDLER, 2004). The project, known as Moderne Importord i Språka i Norden [Modern Loanwords in the Nordic Languages], MIN for short, deals with several aspects of English impact. These can roughly be grouped into aspects of influence, i.e. the quantity and quality of English influence on the languages, and aspects of attitude, i.e. the populations' responses to the influence from English. In relation to the first are comparisons of the number of loanwords in the various languages (SELBACK & SANDØY, 2007), the number of neologisms based on loanwords (KVARAN, 2007), and the degree of adaptation of loanwords into the borrowing language's orthography, morphology and phonology (JARVAD & SANDØY, 2007; OMDAL & SANDØY, 2008). In relation to the second, there are telephone surveys (KRISTIANSEN & VIKØR, 2006), reaction experiments (KRISTIANSEN, 2006), and semi-qualitative interviews which is the focus of this paper (cf. also HÖÖG, 2005; THØGERSEN, 2007). More information about the MIN project can be found at http://moderne-importord.info/. [1]

In Denmark, which was one of the seven speech communities involved in the project, the qualitative investigation was comprised of 47 interviews with respondents from quite disparate walks of life. The respondents were contacted through their workplace and selected to satisfy a two-axis design. One axis was status in the workplace, i.e. managers vs. workers, the other workplace culture, traditional hierarchical vs. modern levelled and more autonomous. In actual practice the last axis corresponds to businesses which produce material goods vs. businesses in the service sector. The two-axis design leads to four cells of 12 respondents (with one recording missing because of technical problems). Inspired by DAHL (1997) and BOURDIEU (1979) we call each of these respondent cells life styles. Representatives of the four life styles are factory line workers and store house workers (low status, traditional), shop assistants and nurses at a nursing home (low status, modern), mechanical and biotech engineers (high status, traditional), and graphic designers and editors at a publishing house (high status, modern). The interviews lasted from 45 minutes to 2 hours. Above I defined the interviews as qualitative. I do so because of the analysis that was conducted on the interview data. The analysis was a grounded discourse analysis much in line with the one described by POTTER and WETHERELL (1987). The interviews themselves involved both standardised and qualitative aspects. On the one hand all respondents were presented with a battery of questionnaires with a total of approximately 120 questions. On the other hand, respondents were encouraged to elaborate on, discuss and argue with the questions and the interviewer—and in general to think aloud. This often led to rather unstructured conversations around the general theme of the interview. Often the interviewer would distance him- or herself from the questionnaire and side with the respondent in performing the task of filling in the questionnaires. The interaction between interviewer and interviewee was audio recorded and forms the data for the qualitative analysis. [2]

The mix of interviewing techniques may raise eyebrows in both camps of the controversy between standardised vs. non-standardised interviewing (LAZARSFELD, 1944). However, presenting all respondents with similar questions, I will argue, is instrumental in getting data to qualitatively analyse how differently the respondents perform the task. Even though the project uses standardised interviewing techniques (FOWLER & MANGIONE, 1990), it does so with the aim of analysing the interview interaction as well as analysing the respondents' discursive presentations of their attitudes (POTTER & WETHERELL, 1987; SUCHMAN & JORDAN, 1990; POTTER, 1996, 1998; HOUTKOOP-STEENSTRA, 2000; STAX, 2000, 2005). The use of non-standardised elements, inspired by KVALE (1994) and SPRADLEY (1979) add further data to the same analysis. See THØGERSEN (2005a) for a discussion of the use of standardised and non-standardised interview techniques in the project. [3]

The project was doubly comparative in its scope. On the one hand it wished to investigate differences between the Nordic communities viewed large. On the other hand it wished to investigate differences between different respondents within each community. It quickly became evident that comparing different informants' answers to the "same" question is no trivial feat. When the subject in question was something as diffuse and as remote from most informants as language policy, the respondents did not seem to have formed any clear opinion, let alone any clear terminology on the subject; and their interpretations of the questions interviewers asked them were often quite far from the interpretations which interviewers themselves would use. [4]

An example I will return to below is a question that had incidentally also been used in the large-scale telephone survey with approximately 6,000 respondents across the Nordic area. The question was: "To which extent do you agree that it would be better if everybody in the world spoke English as their mother tongue?" The respondents could give their answer in a Likert type scale with five steps ranging from "agree completely" to "disagree completely". I expect that the question is meant to gauge respondents' feelings towards a utopia with one world language; English. Is a situation with one world language a dream or a nightmare? It came as a bit of a surprise that some 20% of the population agreed completely or somewhat with the statement. Different interpretations of the high percentage have been proposed, e.g. that it is a reaction by the proportion of the population who feels marginalised by the growing use of English. If English was their mother tongue, they would no longer be marginalised (KRISTIANSEN, 2005, 2006; KRISTIANSEN & VIKØR, 2006). However, looking at the verbal answers of just three respondents, a likely candidate for the "surprising attitudes" is that respondents are not all answering the question we believed we asked. [5]

First I want to present a respondent who I believe answers the "right" question. Her answer presupposes that all adopting English as a mother tongue would mean fewer languages worldwide, which I believe is indeed presupposed by the question.

A: "I completely disagree with that […] because I think it is incredibly exciting that all these different strange (heh heh) languages exist, even if you don't understand them. It is a challenge to try to communicate even if you don't understand an iota of it. It makes the world more differentiated I think, more diverse. […] I realise it would be extremely practical if we spoke the same language all of us, but also quite boring" (Resp31, 20.46).1) [6]

However, if we look at the next respondent, there is nothing in her answer to indicate such presuppositions. On the contrary, she claims that English is the language that she uses the most in her everyday life. This is not true, English is the foreign language she uses the most; the language she uses the most is Danish. We can infer this from her answer. English she uses with Swedish customers, which are only a small fraction of the customers. With the large majority of the customers who are Danish, she uses their common language Danish. This use of Danish, however, is invisible. Speaking Danish does not count as speaking a language, it is just communicating. I get the feeling that she is not discussing whether to adopt a world language (the core of the question), but rather which world language, assuming that it is already established that we are to adopt one.

B: "I agree because I think English is a good language … better than German anyway, and also a bit easier to learn. And it is also what I use the most in my everyday life, for example here in the sales department. With Swedes I always speak English because I'm from Jutland, and I don't understand Swedish very well. And I think it is the best language actually, German I am not very keen on, it sounds a little weird" (Resp41, 3.05). [7]

In fact, the answer makes more sense if we think of the term "mother tongue" as not one's first or most significant language, but rather as an international lingua franca, a language used between people who do not speak or understand each other's languages. It is my claim that a significant proportion of the respondents who declared themselves in agreement with the question's statement, did in fact re-interpret the term "mother tongue" along the same lines as this respondent did. Or in other words, it is highly debatable whether the respondents all answered the same question. [8]

It would be tempting to claim that all respondents who declared that they agreed with the statement had "misinterpreted" the question, and all who disagreed had interpreted it as intended. However, there are some few but interesting exceptions to this generalisation. The respondent C in the next excerpt seems to share A's presupposition that adopting English as a world language would mean the loss of other languages. He just sees this as a benefit, not a deficit.

C: "I agree strongly with that. Again, that is what I meant when I said that we delimit people by having a lot of different languages. […] I would imagine that many, many people got a much bigger profit from their lives—because it is so delimiting" (Resp49, 16.55). [9]

We are of course far from the first to notice the challenges, or indeed the impossibility, of standardising questions used in an interview (LAZARSFELD, 1944; BOURDIEU, 1973 [1999]; MISHLER, 1986; SUCHMAN & JORDAN, 1990; SCHOBER & CONRAD, 1997; CONRAD & SCHOBER, 2000; HOUTKOOP-STEENSTRA, 2000; STAX, 2000; MAYNARD, HOUTKOOP-STEENSTRA, SCHAEFFER & Van Der ZOUWEN, 2002; STAX, 2005; cf. also THØGERSEN, 2005b for a discussion). When informants apparently are not interpreting the "same" question in uniform ways, it does not seem reasonable to compare their answers. A and B above clearly did not define "mother tongue" in the same way. One may choose to disregard this and conclude that one is more negative than the other, but that just seems to put our carefully assembled qualitative data to waste. Without altogether rejecting any comparison in terms of positive and negative answers, I will choose to look elsewhere for more general trends that informants would have in common. This leads to two types of more or less traditional qualitative analyses. [10]

The first of these analyses deals with the form of respondents' attitude answers. That is, how respondents find, describe, argue and defend their attitudes in an on-going interaction with an interviewer. It is an analysis very much inspired by Conversation Analysis (CA). The analysis describes three different traits in the construction of attitudes, pragmaticalisation, neutralisation, and positioning (see THØGERSEN [forthcoming a] for a more elaborate description of the three). [11]

When respondents are confronted with the questions of the interviewer, it is clear that they haven't given these language policy issues much previous thought, at least not in the decontextualised terms which academic linguistics use. They haven't built a general stance to the issues, which they can readily re-present and defend. What they have is some general and well-established norms for what it is to be a good person. The process of pragmaticalisation is the respondents matching of the interviewer's and the questionnaire's decontextualised questions with the pragmatic everyday notions of good and bad, reasonable and ridiculous (cf. BOURDIEU, 1973 [1999] for a comparable view). [12]

The tool for doing pragmaticalisation that I find most interesting is the use of "commonplaces" (cf. BILLIG, 1987). What makes a commonplace is its tautological nature. Although commonplaces seem to give new information about the respondents, on a logical level they do not. No one will ever argue against a commonplace. To be sure, you can disagree with the implications of the commonplace and even oppose it with another commonplace, but the commonplace as such is an established truth. It is a pre-packaged combination with verbal expression and value assessment—and it is irreproachable. The effect of pragmaticalisation through commonplaces is that the respondent's way to negotiate his or her own attitude isn't, as we might have otherwise believed, to sit back and feel deep in his or her soul what one thinks about the issue one is faced with. Settling on an attitude is rather deciding which commonplaces best fit the issue at hand. [13]

To schematise, the process of settling on an attitude runs as follows: We start with a question posed decontextualised, all encompassing, in order to be something the respondent can form an opinion towards. It is next pragmaticalised by being matched with a number of (conflicting) commonplaces. In the end, as the conclusion, the respondent settles for one of the commonplaces as more appropriate than the opposing—and this is noted as the respondents' true attitude. Only in the rare occasion do the respondents return to the decontextualised sphere and express their attitudes in the format given by the question. It is far more common to stay in the contextualised and more reserved sphere. The reservations, which are inevitably a consequence of the respondents reformulating the question and answering only their own question, brings us to the next feature of attitude formatting, neutralisation. [14]

By neutralisation I mean the very common practice that respondents will present their attitude as if it is not an attitude at all but simply the only reasonable stance on the matter. The choice then is presented as a non-choice. This is theoretically interesting. We tend to assume attitude evaluations to be exclusive but equivalent. We assume that our attitudes are (more or less informed) choices between like evaluations in which no choice is inherently better. Attitudes, in other words, we assume to be a matter of individual preference, not of rational justification. [15]

Through neutralisation, however, attitude constructions are not a choice between equals. It is an argument that one's own choice is neutral, considered and without self-interest, whereas the choices of the others are biased, rash and often governed by self-interest. More than anything, what distinguishes one's choices from those of the others, is that one's own stance is presented as moderate, whereas that of the others is presented as fundamentalist and dogmatic. This is apparent even on the linguistic surface where opposing views are often presented with extreme case formulations (POMERANTZ, 1986) such as "all", "always", "completely", whereas own views are presented with "softeners" (EDWARDS, 2000) such as "some", "sometimes", "a little". [16]

One further strategy in presenting one's own view as neutral is to avoid presenting it in positive terms. As mentioned above, opposing views are often presented as somehow extreme and (through pragmaticalisation) often in commonplaces that no one can reasonably dispute. A way to "present an attitude as though it is no attitude" is then to simply reject an extreme version of others' views without explicating one's own. In rhetorical terms this is what is known as arguing against a straw man. [17]

The third feature I will mention is positioning. The term positioning is adopted from constructivist (social) psychology traditions that interpret identity as the outcome of interactional negotiations rather than inner qualities (DAVIES & HARRÉ, 1990; HOWIE & PETERS, 1996; WETHERELL, 1998). Positioning is the dynamic identity construction that happens as identity categories are being introduced and evaluated as something the interlocutors are or are not. Every utterance is produced with orientation to the picture it paints of the speaker—for the interlocutor as well as for the speaker him- or herself. [18]

Again this is interesting from a theoretical perspective. We may naïvely think that a survey or an attitude investigation is an event where social values play a very little role. The respondents are confronted with a question; they search their feelings for an attitude and present their answers. Questions are always formulated value neutral without a social bias in one direction or the other. In fact it is a fundamental of interviewing that interviewers should never evaluate their questions or the respondents' answers. In an attitude interview no attitudes are tabooed. The objects respondents are asked to present their opinions towards are in other words kept socially neutral in formulations as well as in feedback to responses. It is striking, then, how much work respondents put into re-socialising the neutralised questions. And further, it is striking how often a question about personal attitude is answered with reference to social categories ("I am [not] an X") instead of discrete attitude statements ("I do [not] believe Y"). [19]

What we have then are respondents constructing a local identity by orienting towards the different social positions that they introduce in their answers. Often they will draw up a picture of the positions before settling for one of them. But, mind you, first after discussing the merits of the opposing views—and therefore presenting their view as a considered view. [20]

Secondly, a discourse analysis was conducted. This analysis was in part inspired by Dennis PRESTON's work with "folk linguistics", i.e. laymen's understandings, descriptions, indeed their cultural knowledge regarding linguistic issues (PRESTON, 1993, 1994; NIEDZELSKY & PRESTON, 1999). The discourse analysis highlights some of the discourses that recurrently surround English in the respondents' answers, however not so much through what they state in their answers as through what their answers presuppose. In TOULMIN'ian terms (TOULMIN, 1958), I am not so much interested in respondents' claims as in the data and (often implicit) warrants the claims are based on. [21]

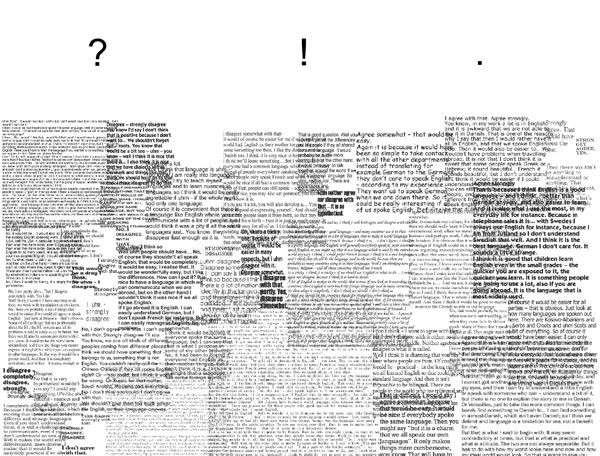

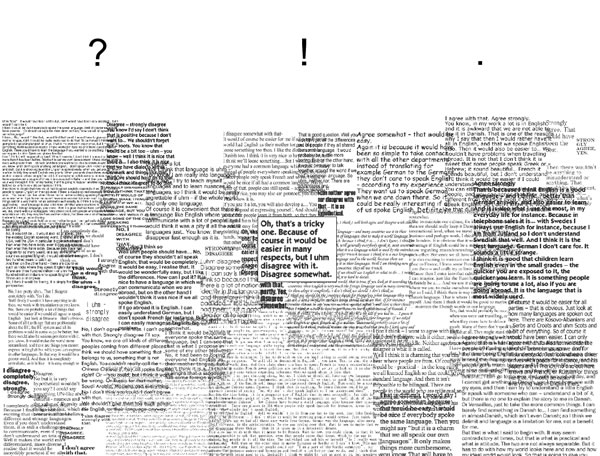

Another significant inspiration for the analysis was the work on discourses or interpretive repertoires which scientists draw on in explaining their work (e.g. MULKAY, 1991). The audio recordings of the interviews were transcribed (a total of approximately 2,000 pages). Since the interviews were conducted in a semi-structured way, it was relatively easy to split the transcripts into separate files concerning each of the questions all respondents were asked to negotiate. Presenting respondents' answers in a "synoptic" way like this makes it very easy to spot general trends in respondents' answers, both for individual life styles and for the sample as a whole. In THØGERSEN (2007) the discourses surrounding the individual questions are handled in a more exhaustive way (see also THØGERSEN, forthcoming b). Here I want only to focus on three discourses that proved more universally applicable than others. In fact they are so applicable that the same discourse can often be used to argue opposite stances. This observation is much in line with ROTH and LUCAS: "Although a student changed his epistemological claim, he could still draw on the same repertoire, but in a new context" (1997, p.168). The three discourses I focus on, I refer to as "English as the default language of the world", "English as a sign of modernity and internationality", and "the wish for status quo". [22]

Regarding "English as the default language of the world", it is striking e.g. how respondents arrive at an estimate of different languages' relative importance as international languages. Irrespectively of whether a respondent estimates a language as "important" or "unimportant" they arrive at their estimation using the same algorithm: 1) Is the language a "big" language? 2) Can the speakers of the language be assumed to speak English? If the answer to the first question is yes and the answer to the second is no, then the language may be an important one. If the speakers of the language, however, are deemed to speak English, then the language is relatively less important. So in arguing for the importance of Arabic we get on the one hand:

"Arabic plays a very large role as an international language. A lot of people live in the Arabic World, and I believe few of them are really good at English" (Resp19, 11.20). [23]

And on the other hand:

"In all the Arabic countries I've been to, they speak English really well. So Arabic won't play a very large role. They are all British states" [presumably: "previous colonies"] (Resp25, 17.18). [24]

The same basic reasoning, mutatis mutandis, is used when arguing about which languages are most important to speak as foreign languages, which language should be taught in school etc. I believe that this is very illustrative of the unquestioned importance the Danish respondents ascribe to English. [25]

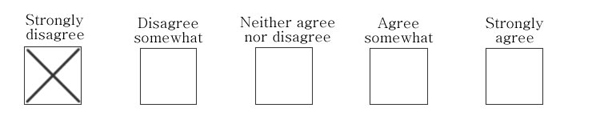

In several different questions respondents were required to estimate the relative English influence in a number of different language, different language domains etc. Looking at how the respondents come to their estimation of e.g. the amount of English influence in Sweden compared with Norway is noteworthy. Compared here is one respondent who arrives at the judgement that Sweden has more English influence than Norway, with another who arrives at the opposite conclusion.

"The Swedes are very international compared to the Norwegians, generally, I think. They have these giant companies, and there everyone speaks English" [Resp32, 44.00].

"They [the Swedes] are not as international, they want it in Swedish translation" (Resp25; 49.35). [26]

The interesting point is how the respondents arrive at his estimation of the amount of English, by estimating how international the two populations are. In other words English (influence) is equated with internationality (and in other responses modernity); the more international or modern, the more English influence. And significantly, the same line of arguing is used irrespectively of the conclusion, showing both the prevalence and the strength of the argument type. [27]

The third discourse I wish to mention is the often occurring matter-of-fact claim to status quo. It is not very remarkable that respondents use state-of-affairs as starting point for an attitude claim, and it is of course not specific to the attitudes towards English. It is however a very significant feature of the attitude interview; on the one hand because it acts (again) to minimise the respondent's stake in the presentation of an attitude—he merely establishes a fact—on the other because common knowledge as well as presuppositions in the interview questions thus get solidified. Presuppositions get taken for respondents' attitudes and wishes, whereas what they are framed as in the interview are merely expressions of states-of-affair. [28]

From the point of view of the validity of an attitude investigation, it is significant that what respondents seem to share is not their inner emotions, but rather their most qualified guess at how things already are. What we have, then, is the public discourse reproducing itself. If public discourse has it that, say, Danish has a laissez faire policy towards English loan words; this laissez faire'ism gets registered as the most common attitude, which solidifies the policy etc. [29]

However, for two reasons the qualitative analyses were not altogether satisfying. On the one hand the analyses avoided the underlying initial question of the entire investigation, i.e. "what are (groups of) Danes' attitudes towards English?" On the other hand are more philosophical and ethical reflections on the nature and role of linguistic representations. To approach respondents' attitudes by examining how their answers are constructed, though all good and well, does not quite delve into the big question. If anything, the qualitative analysis presents sound reasons for rejecting the big question altogether as a valid object of study through a questionnaire as much recent social psychological thinking about attitudes has done (BILLIG, 1987; POTTER & WETHERELL, 1987; EDWARDS & POTTER, 1992; WETHERELL & POTTER, 1992; POTTER, 1996, 1998; WETHERELL, 1998). The philosophical and ethical reflections arise out of the schism that may be bluntly stated like this: If I have painstakingly taken it upon me to show that informants do not understand my questions, what leads me to think that I can understand their answers without any problems, sort them and present them as they were intended? However, it still seems very much worthwhile to at least try to form an answer to the big question. [30]

The challenge, then, is to develop a methodological and presentational modus that is able to on the one hand deal with the "big question", and on the other hand maintain at least some of the fragmentation which I have shown to be a defining characteristic of the data. To do this, I will first discuss some of the theoretical background that frames this proposed "mode of answer" and maybe makes it more tangible to specify what is needed of a solution. After that, I will describe the technical solution I propose may elucidate the sought after "big" answer. [31]

DERRIDA (1967 [1997]) pointed out that language is not transcendental; it is not positioned outside the world, pointing at it. It is immanent, itself a part of the world. Meaning in language is therefore never anchored in an exterior reality. Language instead works as a chain of signs, with one sign referring to another sign, which refers to another sign etc. In the abstract, this theory may be hard to manage. But I believe it is essentially the same insight the interviewer and respondent are working their way to in interactions like this:

|

Written Question: |

What is your attitude towards linguistic purism (= the act of trying to keep the language "pure" from outside influence)? |

|

Respondent: |

It depends very much on the viewpoint. If it is seen from a nationalistic1 point of view, I guess I think it is very negative. |

|

Interviewer: |

Mm—and if it is from a democratic2? |

|

Respondent: |

Then I believe it is something else. That is probably what is in it. Yes, if it is from a wish to involve as many as possible2, I think it is fine, but if it is from some notion of something uniquely Danish which must be protected1, it makes me sick, you know. I guess that is probably it. |

|

Interviewer: |

But isn't it hard to tell the difference? |

|

Respondent: |

Incredibly hard. That is why it is so hard to relate to these things and one gets so ambivalent. [Resp28, 83.00] [32] |

I have indexed the references to "purism" with subscribed 1's and 2's to highlight the two opposing definitions each associated with its own attitude. What I want to show with this excerpt is how the respondent does not tie his attitude to the linguistic sign he is presented with, but rather introduces new signs, "democracy" and "nationalism", which he then negotiates. To be fair, it is the interviewer who gives the label of the second sign as "democratic", but that there is an opposition between "nationalistic" and other aspects is already obvious in the respondent's immediate response, which introduces different "points of view". Furthermore the respondent is very quick to pick up on the interviewer's proposed label and elaborate on it. The outcome is that "purism" is inscribed meaning not in what it refers to in a language external world—what it means—but through the other signs that it is related to. It should be needless to say that this is not unique to "purism"; "nationalism" could get exactly the same treatment, e.g. separating it in "all citizens are equal" and "we are better than all others". [33]

To DERRIDA, the consequence of the analysis seems to be that since words only refer to words, we can no longer meaningfully discuss final meaning through words—which, ironically, he uses words to say. In other words, we can deconstruct "meaningful" expressions, but we cannot build new. We are at a, not very satisfying, semantic dead end. Here it can be fruitful to enter Gilles DELEUZE in the discussion (DELEUZE & PARNET, 1977 [1987]; DELEUZE, 2004). DELEUZE basically accepts DERRIDA's analysis, that language is not transcendental, but insists, nevertheless, that a lot of meaningful reality can be built using language. Language to DELEUZE is in the original sense poetic, "constructive". In other words, instead of trying to describe reality with words, we should rather try and construct a reality that brings us closer to some understanding. Now DELEUZE's rejection of the attempts to describe a world outside language through language, i.e. denying to use language the way we are used to using language, often makes his writing hard to pin down. To understand DELEUZE's project, I therefore turn to one of his commentators, Todd MAY:

"When we think about problems, we tend to think about them in terms of solutions. Problems, it seems to us, seek solutions. Not only do they seek solutions, each problem seeks a unique solution, or at least a small set of them. It is as though a problem were merely a particular lack or fault that a solution will fill or rectify. That is how we were taught to think of problems at school. And that is why schools have so many tests. […] But we do not need to approach things this way. Instead of seeing these as problems that seek a particular solution, we might see them as opening up fields of discussion, in which there are many possible solutions, each of which captures something, but not everything, put before us by the problem" (MAY, 2005, p.83). [34]

Applying this dictum to attitude investigations may present some problems, but it definitely also opens up some new avenues to investigate. Following the dictum, one should not try to determine what Danes' attitudes are towards English; this would surmount only to what MAY calls "posing a question only to find the solution". Furthermore, after rejecting giving the simple, categorical answer, we may not simply rephrase the question in order to get a more statistically and linguistically valid answer. This in a sense was what I did with the qualitative analyses. It rejected the quantitative, uniform analysis only to introduce a uniform qualitative analysis. Might a more valid and honest analysis not rather be an analysis that does not try to give uniform, memorable conclusions, but instead try to maintain the multi-facetted, self-contradictory discussions? Of course, this may be a dead end. In fact we often do pose questions because we want a tangible answer. So, attempting to follow DELEUZE'/MAY's dictum, how would one go about doing this? [35]

3.1 The text which isn't a text

In a way we have taken a detour through philosophy to arrive closer to home, viz. deep in a problem anthropology has always been fighting: How can we describe "the other" as just as complex, just as contradictory as we are ourselves? CLIFFORD and MARCUS (1986) edited a classic work that tries to come to terms with just this problem. They write in their introduction:

"For [Edward] Said, the Orient is ‘textualized'; its multiple, divergent stories and existential predicaments are coherently woven as a body of signs susceptible of virtuoso reading. This Orient, occulted and fragile, is brought lovingly to light, salvaged in the work of the outside scholar. The effect of domination […] is that they confer on the other a discrete identity, while also providing the knowing observer with a standpoint from which to see without being seen, to read without interruption" (p.12). [36]

In sum, the "essentialist" descriptions seem to be under attack from various sides. Not only from a philosophical and from an empirical side, but here also from a political side, it is objectionable to attempt to pigeonhole other people's attitudes, opinions, experiences, world views etc. into discrete categories that we believe to be sensible. If we respect the people we investigate as equals, we should give them the right to define their own rationality, shouldn't we? Indeed, the very attempt to "describe" others, i.e. make them object of a description which we hold sole responsibility for and power over, is objectionable. [37]

CLIFFORD and MARCUS describe an early (perhaps unwilling) attempt to break the chains of the all-powerful writer:

"James Walker is widely known for his classic monograph The Sun Dance and Other Ceremonies of the Oglala Division of the Teton Dakota (1917) […]. But our reading of it must now be complemented—and altered—by an extraordinary glimpse of its 'makings'. Three titles have now appeared […]. The first (Lakota Belief and Ritual) is a collage of notes, interviews, texts, and essay fragments written or spoken by Walker and numerous Oglala collaborators. This volume lists more than thirty 'authorities', and whenever possible each contribution is marked with the name of its enunciator, writer, or transcriber. These individuals are not ethnographic 'informants'. Lakota Belief is a collaborative work of documentation, edited in a manner that gives equal rhetorical weight to diverse renditions of tradition. Walker's own descriptions and glosses are fragments among fragments" (p.15). [38]

In this vein, a way for me to present an honest monograph of Danes' attitudes towards English might be then to publish transcripts of all the interviews I conducted, not holding off the contradictory examples, not explaining (imposing my understand that is), and putting the same emphasis on the interviewer's role in the construction of attitudes as upon the respondents. Although this non-interventionist, non-analytic approach does sound tempting, it is also unsatisfying to merely present all data and offer no analysis and no structure whatsoever. Some sort of analyses and some sort of data selection is necessary. The major break from writing in "ordinary" academic tradition I am attempting is to produce a presentation that is:

pluri-linear rather than of uni-linear,

simultaneous rather than chronologically progressing,

multi-voiced rather than one-voiced,

fragmentary rather than uniform,

suspended rather than finished. [39]

In my experimenting with this non-essentialist presentation, I worked with an interactive computer based presentation, substituting the regular printed text for a presentation in Macromedia Flash®. Flash® is a very commonly used program for making interactive elements on websites. Generally speaking, if a website contains moving elements that responds to your actions, chances are that some elements are programmed in Flash®. The rest of this article will describe the layout of the presentation and discuss why it came to look as it does. The description is a theoretical addendum; ideally the presentation should speak for itself.

Online version: Cacophony [40]

3.2 Cacophony—to lend voice to the people

Using a presentation in Flash® (or any other interactive presentation package) gives us the ability to respect at least some of the ideals of pluriformity and suspended closure described above. The problem as described by CLIFFORD and MARCUS and also by a range of other contemporary sociologists and anthropologists within a broadly speaking "reflexive" paradigm (e.g. ASHMORE, 1989; MULKAY, 1991; BOURDIEU & WACQUANT, 2002; JØRGENSEN, 2002,) can be narrowed down to the fact that any presentation of knowledge is always presented from some elevated position (see also the two special issues of FQS on "Subjectivity and Reflexivity in Qualitative Research", MRUCK, ROTH & BREUER, 2002 and ROTH, BREUER & MRUCK, 2003). Presentations may try through various means to include themselves in the analysis or to analyse their own utterances as utterances on a par with all other utterances, but the very nature of writing fights this attempt (ONG, 1982 [2007]; LANDOW, 1997). For academic writing with heightened demands on transparency, this may be even truer. This has led some of the "reflexivists" to attempt to break the boundaries of academic writing (e.g. TYLER, 1986; ASHMORE, 1989; FUGLSANG, 1998; FUGLSANG & CARNERA LJUNGSTRØM, 1999; ROTH, McROBBIE & LUCAS, 1998; ROTH & McROBBIE, 1999; ROTH, 2001, 2002, see also the aforementioned FQS special issues, and JONES et al., 2008). In traditional academic writing there is but one voice of writing or editing. Even if the author/editor quotes other voices, he or she is ultimately the gatekeeper who admits and rejects other voices and the conductor who decides when they can speak. Furthermore academic writing (perhaps all writing) has a normative demand for consistency. It is allowed to present contradictory statements, but then the contradiction must be resolved at some higher level. Most fundamentally, it seems as though the text fights the subversion of its own objectivity simply because it has a unilinear chronology. It is impossible in written text to say two things at the same time, and you cannot go from one point in the text to two related points—(though this has been attempted in literature and cinema e.g. by Svend Åge MADSEN in Den Ugudelige Farce, 2002, http://www.g.dk/bog/den-ugudelige-farce-svend-aage-madsen_9788702018240, and by Krzysztof KIESLOWSKI in Przypadek aka Blind Chance, 1987, http://www.imdb.com/title/tt0084549/). Some researchers have tried to import the same dual linearity into their academic texts using parallel texts printed on the same page, e.g. two columns with one presenting reflexive comments to the text presented in the other (RUBOW, 2000; ROTH, 2002), or using inserts in the form of quotes, voice-overs etc. (ROTH & McROBBIE, 1999). These however are rather rare exceptions to the otherwise strong normative demand that you have to treat one point before you can turn to the other. As a commensurable of these characteristics of (academic) writing, you cannot give two contradictory statements at the same time. [41]

The nature of (academic) texts which forces unilinearity has led some researchers to abandon written texts altogether, or at least to expand on texts' limitations by including also other, often more artistic means of expression. A case in point is FQS special issue on "Performative Social Science" (JONES et al., 2008), in particular ROBERTS' (2008) historical overview of attempts to circumvent the shackles of the "traditional authoritative text" (ROTH et al., 1998, p.108). In my attempt to write a non-textual "text" I have opted for an interactive presentation using Flash®. Using Flash® (or other interactive presentations), I think allows us to develop a style which is more consistent with the theoretical, methodological and political demands presented by social constructivism. As an added feature, interactive presentations may be constructed as un-ended and never-ending. While the written text is already finished and can be grasped from beginning through middle to end, the interactive presentation may be constructed to be "written" only when it is "read". In this case it would be impossible to uphold the illusion of a privileged conclusion and a finished whole. The presentation ends when no one watches it. The conclusion is suspended and runs like a thread through the whole "reading", or maybe it only takes shape after the reader has left it. It is certainly useless to look for the conclusion on the last page. [42]

Along with presenting the investigation results in an alternative and hopefully more theoretically consistent way, the presentation should also offer a general criticism of the use of opinion polls in creating news and research headlines. As discussed, answers given by different informants are not necessarily comparable, and interpretation of answers using only the researcher's focus on matters may lead to wholly invalid analyses. The point is that the clear conclusion of an opinion poll suppresses all of the arguments and the counter arguments. The purpose of the conclusion is exactly this, to minimise noise. I, on the other hand, insist that the noise is the real core of the investigation. The many intermingling voices with all their ambiguities are what give the answer. [43]

This presentation takes its beginning in the catch phrase "to lend voice to the people"—a phrase often heard in public discourse. The reading aloud of excerpts of the respondents' answers is therefore essential. The voice is here represented by one person reading the answer of 47 respondents. Using only one reader has both a practical (anonymising) effect and a theoretical point. The ones we are interested in are the Danes, not a few scores of individuals. Using one voice, the answers come out as anonymous answers—in theory they could be anybody's answer. They could even be the same person who had all the different views on the same subject at different times, in different contexts. This point is further emphasised when several answers are listened to at the same time. When one reader reads them all, the answers can blend into cacophony. This is a metaphor for the project at large. When you follow only one person's reasoning, everything seems sensible. When you try to hold several answers stable to compare them, complexity tends to expand exponentially. If you want to define the all-encompassing "voice of the people", you hear only confusion. [44]

A note on translation: All answers were of course given in Danish. Mind you this was not scripted and carefully prepared Danish, but spontaneous speech on difficult subject matter. The respondents hesitate, rephrase, contradict themselves, create non sequiturs and often ascribe words definitions quite far from the dictionaries'. Furthermore, an interviewer was present, trying to spur the respondent on and offering tokens of reception. The interviewer's participation has been edited out of the respondents' answers. In translating I have tried to maintain this spontaneity, while editing the answers enough for them to become largely intelligible, while trying to maintain the overall tone of the individual answer. This is not to say that no information is lost in translation; of course it is. However, this loss is of a completely different order than the loss of plurality wilfully introduced when all answers are forced into the Likert scale. One dilemma is how to translate the dedicated generic pronoun "man" [English: "one/you"] in e.g. "man skal tale engelsk" [English: "one/we/you must speak English"]. "Man" is used both singular and plural, and is ambiguous with regards to inclusion of the speaker. Generally I have opted for "you" or "we", and avoided "one" which often seems quite formal compared with "man". Using "you" or "we" however, forces a distinction regarding inclusion of the speaker, which is not present in the Danish text. The "voice" of the Danish attitudes is as you can probably tell not a native-speaker of English. After all, it is Danish respondents that are re-enacted; it is not a problem if their "Danishness" is also re-enacted. [45]

The presentation is composed of a number of imaginary "rooms": [46]

The first screen shows the question the respondents were presented with, and the range of pre-defined answers ranging from "agree completely" through "disagree completely". The reading of the question should bestow a feeling of being in the respondents' place. Answers presented on-line without preparation often seem confusing. By presenting the viewer with the actual question I hope to show why answers are as hesitant and ambivalent as they sometimes are.

Figure 1: Cacophony, the question

When the question is read through, the presentation continues to "the main screen" (3.3.2).

If one clicks on the screen while the question is being read, one is sent to "the main screen" (3.3.2). [47]

"The main screen" is the central and weighty part of the presentation. The other nine "rooms" can be seen as commentaries to this. It consists of several parts. [48]

The largest part of "the main screen", the entire bottom part, is filled with quotes from the 47 respondents interviewed. The answer of each respondent has its own square. Different fonts are used to illustrate the different respondents. The quotes partly overlap to illustrate the "messiness" which is also illustrated by the use of cacophonous voices. The quotes are printed in grey in contrast to "the question" (3.3.1) and "the attitude answers" (3.3.3) which are printed in black. This of course is a metaphorical hint to our trying to see attitudes as black or white, when they often are rather shades of grey.

Figure 2: Cacophony, the main screen [49]

When one moves the curser over an answer, it is magnified and lifted out of the mess with a frame. It is thus possible to zoom in on any given answer. Simultaneously, a reading of the answer begins and continues until the end of the answer. If one moves over a new answer, this will be the one zoomed in on and the reading of that will begin. But the reading of the former answer continues. One can start several readings in this way (depending on the power of the computer) and thereby hear the cacophony of voices that are the theme of the presentation.

Figure 3: Cacophony, the main screen with one answer highlighted

If one clicks on an answer, one is sent to "the attitude answers" (3.3.3). [50]

If one rolls the curser onto the question mark all readings stop. If one clicks on it, one is sent back to "the question" (3.3.1). [51]

If one rolls the curser onto the question mark all readings stop. If one clicks on it, one is sent to "the newspaper headline" (3.3.4). [52]

If one rolls the curser onto the question mark all readings stop. If one clicks on it, one is sent to "the narrative of the blind men and the elephant" (3.3.5). [53]

If one clicks on an answer in the main screen one is sent to the "filtered" quantitative attitude answers on a scale from "agree completely" to "disagree completely". The transformation is not without a hint of sarcasm. When one removes the inconsistencies and reservations of the answer, one also removes the most interesting parts of it. And more fundamentally, one removes the connection the answer has with the lived world. The answer "agree completely" is hard to comprehend when it is seen outside of a rhetorical context. When the standardised answer is seen in connection with its rhetorical presentation, most answers make good sense. [54]

Simultaneously the attitude answers are meant to criticise that quantification treats things together that do not go together. As one can see from the answers, the respondents' arguments for choosing the same quantified answer are widely different—often even contradictory; and even respondents choosing widely different "attitude answers" will often produce remarkably similar qualitative answers.

Figure 4: Cacophony, the attitude answers

If one clicks on the screen, one is sent to "the main screen" (3.3.2). [55]

If one clicks on the exclamation point, one is sent to a fictional newspaper headline using the percentages gathered in the quantitative analysis of the attitude answers. The headline is a comment on the way opinion polls are used as news. The critique is two-fold. On the one hand it criticises that we have a tendency to see the clear and stringent answers as truer than the ambiguous and unclear. The truth of the matter is the opposite. The noise is primary; the clear answer is an abstraction—or even an illusion. The headline rests only on the unstable support of the many confused voices; it merely fails to mention this in favour of a clear (but faulty?) statement. [56]

On the other hand, it comments on the paradox that opinion polls can be newsworthy. If the participants form a representative sample of the population, their answers should never surprise the population, should they? Boldly stated, every opinion poll that makes a headline, should give rise to suspicion of (presumably accidental) manipulation. Either the answers loose their meaning when derived of context (as here), or the transformation from question wording to interpretation is not as simple as we are lead to believe.

Figure 5: Cacophony, the newspaper headline

If one clicks on the screen, one is sent to "the main screen" (3.3.2). [57]

3.3.5 The narrative of the blind men and the elephant

If one clicks on the full stop, one is sent to the narrative of the blind men who meet an elephant and describe it from each their vantage point: as a tree trunk, a snake or a spear. The narrative can be read as an allegory of the problem of the opinion poll; that it gathers the respondents' manifold, incompatible utterances under one uniting headline.

If one clicks on the screen, one is sent to "the main screen" (3.3.2).

Figure 6: Cacophony, the narrative of the blind men and the elephant [58]

In this description of the presentation, I have kept the description of the narrative for last. Therefore it gets the prominent place I argued above. Could it be that this is really the conclusion? In the presentation itself, the narrative does not necessarily get the same prominence. The viewers' interaction with the presentation is beyond my control. Of course, one could claim (as a critical colleague of mine did) that the placement of the full stop in the far right of the screen will lead left-to-right readers to see it last, and thus to read it as a conclusion. By this reasoning, the three punctuation marks form a thesis—anti-thesis—synthesis, a sort of simplest possible argumentative structure. I admit that this is a plausible interpretation and that I have probably had a moment of weakness when I placed the punctuation marks and the content they link to. [59]

The presentation is inserted above in Section 3.1. When you click the link, the presentation opens in a new window. The presentation uses quite large sound and picture files. It may therefore take a while to load. To be manageable the file is rather compressed. If you are interested in a version in better quality, you are welcome to write the author for a CD with the file. For best performance, the computer monitor should be set to a resolution of 1280x1024 or better. [60]

I have experienced crashes in which the presentation no longer responds. This is most likely to occur if a lot of activities (i.e. a lot of sound files) are started at the same time. Should this happen, the window is minimised by pressing Esc, and it can then be closed down, and the presentation can be restarted. [61]

I have not studied Flash® programming (or any other kind of programming). I have taught myself what little I know about Flash® by making this presentation. I had a message I wanted to bring across and an experiment I needed to try; and here was the opportunity to try it out. It really is possible for a novice to make a working presentation. However, I'll be the first to admit that the programming isn't the neatest you are likely to come across. I hope viewers will bear this in mind, and judge the presentation by its potential rather than by its execution. [62]

I owe a big thank you to Michael BARNER-RASMUSSEN for pointing out weaknesses and inconsistencies in a draft version of this paper. The weaknesses and inconsistencies that remain are all my fault.

1) The code is comprised of the respondent ID (here respondent # 31) and the time of the sequence (here 20 minutes 46 seconds into the recording). <back>

Ashmore, Malcolm (1989). The reflexive thesis. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Billig, Michael (1987). Arguing and thinking. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Bourdieu, Pierre (1973 [1999]). Den offentlige mening eksisterer ikke. In Henrik Hovmark (Ed.), Men hvem skabte skaberne (pp.224-235). Copenhagen: Akademisk Forlag.

Bourdieu, Pierre (1979). Distinction, a social critique of the judgement of taste. London: Routledge.

Bourdieu, Pierre & Wacquant, Loïc J.D. (2002). Refleksiv sociologi—mål og midler. Copenhagen: Hans Reitzel.

Clifford, James & Marcus, George E. (Eds.) (1986). Writing culture. The poetics and politics of ethnography. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Conrad, Frederick G. & Schober, Michael F. (2000). Clarifying question meaning in a household telephone survey. Public Opinion Quarterly, 64(1), 1-28.

Dahl, Henrik (1997). Hvis din nabo var en bil. Copenhagen: Akademisk Forlag.

Davies, Bronwyn & Harré, Rom (1990). Positioning: The discursive production of selves. Journal for the Theory of Social Behaviour, 20(1), 43-63.

Deleuze, Gilles (2004). Desert islands. Los Angeles: Semiotext(e).

Deleuze, Gilles & Parnet, Claire (1977 [1987]). Dialogues. New York: The Athlone Press.

Derrida, Jacques (1967 [1997]). Of grammatology. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins.

Edwards, Derek (2000). Extreme case formulations: Softeners, investment, and doing nonlitteral. Research on Language and Social Interaction, 33(4), 347-373.

Edwards, Derek & Potter, Jonathan (1992). Discursive psychology. London: Sage.

Fowler, Floyd F. & Mangione, Thomas W. (1990). Standardized survey interviewing. Minimizing interviewer-related error. London: Sage.

Fuglsang, Martin (1998). At være på grænsen—en moderne fænomenologisk bevægelse. Copenhagen: Nyt fra Samfundsvidenskaberne.

Fuglsang, Martin & Carnera Ljungstrøm, Alexander (1999). Det nøgne liv—en poetik for det sociale. Frederiksberg: Samfundslitteratur.

Graedler, Anne-Line (2004). Modern loanwords in the Nordic countries. Presentation of a project. Nordic Journal of English Studies, 3(2), 5-22.

Höög, Catharina Nyström (2005). Teamwork? Man kan lika gärna samarbeta! Svenska åsikter om importord. Oslo: Novus.

Houtkoop-Steenstra, Hanneke (2000). Interaction and the standardized interview. The living questionnaire. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Howie, Dorothy & Peters, Michael (1996). Positioning theory: Vygotsky, Wittgenstein and social constructionist psychology. Journal for the Theory of Social Behaviour, 26(1), 51-64.

Jarvad, Pia & Sandøy, Helge (Eds.) (2007). "stuntman" og andre importord i Norden. Om udtale og bøjning. Oslo: Novus.

Jones, Kip; Gergen, Mary; Guiney Yallop, John J.; Lopez de Vallejo, Irene; Roberts, Brian & Wright, Peter (Eds.) (2008). Performative social science. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung / Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 9(2), http://www.qualitative-research.net/index.php/fqs/issue/view/10.

Jørgensen, Marianne Winther (Ed.) (2002). Refleksivitet og kritik. Frederiksberg: Roskilde Universitetsforlag.

Kristiansen, Tore (2005). Engelsk i dansk sprog og sprogsamfund: Rapport fra en landsdækkende meningsmåling. Danske Talesprog, 6, 139-169.

Kristiansen, Tore (Ed.) (2006). Nordiske sprogholdninger. En masketest. Olso: Novus.

Kristiansen, Tore & Vikør, Lars (Eds.) (2006). Nordiske språkhaldningar. Ei meningsmåling. Oslo: Novus.

Kvale, Steinar (1994). InterView. Copenhagen: Hans Reitzels Forlag.

Kvaran, Guðrún (Ed.) (2007). Udenlandske eller hjemlige ord? En undersøgelse af sprogene i norden. Oslo: Novus.

Landow, George P. (1997). Hypertext 2.0. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins.

Lazarsfeld, Paul F (1944). The controversy over detailed interviews—an offer for negotiation. The Public Opinion Quarterly, 8, 38-60.

Madsen, Svend Åge (2002). Den ugudelige farce. Copenhagen: Gyldendal.

May, Todd (2005). Gilles Deleuze: An introduction. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Maynard, Douglas W.; Houtkoop-Steenstra, Hanneke; Schaeffer, Nora Cate & van der Zouwen, Johannes (2002). Standardization and tacit knowledge: Interaction and practice in the survey interview. New York: Wiley.

Mishler, Elliot G. (1986). Research interviewing. Context and narrative. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Mruck, Katja; Roth, Wolff-Michael & Breuer, Franz (Eds.) (2002). Subjectivity and reflexivity in qualitative research I. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung / Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 3(3), http://www.qualitative-research.net/index.php/fqs/issue/view/21.

Mulkay, Michael (1991). Sociology of science. A sociological pilgrimage. London: Open University Press.

Niedzelsky, Nancy & Preston, Dennis R. (1999). Folk linguistics. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter.

Omdal, Helge & Sandøy, Helge (2008). Nasjonal eller internasjonal skrivemåte? Om importord i seks nordiske land. Oslo: Novus.

Ong, Walter J. (1982 [2007]). Orality and literacy. London: Routledge.

Pomerantz, Anita (1986). Extreme case formulations: A way of legitimizing claims. Human Studies, 9, 219-229.

Potter, Jonathan (1996). Attitudes, social representations and discursive psychology. In Margaret Wetherell (Ed.), Attitudes, social representations and discursive psychology (pp.119-173). London: Sage.

Potter, Jonathan (1998). Discursive social psychology: From attitudes to evaluative practices. European Reviews of Social Psychology, 9, 233-266.

Potter, Jonathan & Wetherell, Margaret (1987). Discourse and social psychology. London: Sage.

Preston, Dennis R. (1993). The uses of folk linguistics. International Journal of Applied Linguistics, 3, 181-259.

Preston, Dennis R. (1994). Content-oriented discourse analysis and folk linguistics. Language Sciences, 16, 285-331.

Roberts, Brian (2008). Performative social science: A consideration of skills, purpose and context. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung / Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 9(2), Art. 58, http://nbn-resolving.de/urn:nbn:de:0114-fqs0802588.

Roth, Wolff-Michael (2001). The politics and rhetoric of conversation and discourse analysis. Review Essay: Ian Parker and

the Bolton Discourse Network (1999). Critical Textwork:

An Introduction to Varieties of Discourse and Analysis / Carla Willig (Ed.) (1999). Applied Discourse Analysis: Social and

Psychological Interventions / Paul ten Have (1999). Doing Conversation Analysis: A Practical Guide. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung / Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 2(2), Art. 12, http://nbn-resolving.de/urn:nbn:de:0114-fqs0102120.

Roth, Wolff-Michael (2002). Grenzgänger seeks reflexive methodology. Review Essay: Mats Alvesson & Kaj Sköldberg (2000). Reflexive Methodology: New Vistas for Qualitative Research / Christiane K. Alsop (Ed.) (2001). Grenzgängerin: Bridges Between Disciplines. Eine Festschrift für Irmingard Staeuble. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung / Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 3(3), Art. 2, http://nbn-resolving.de/urn:nbn:de:0114-fqs020328.

Roth, Wolff-Michael & Lucas, Keith B. (1997). From "truth" to "invented reality": A discourse analysis of high school physics students' talk about scientific knowledge. Journal of Research on Science Teaching, 34(2), 145-179.

Roth, Wolff-Michael & McRobbie, Cam (1999). Lifeworlds and the "w/ri(gh)ting" of classroom research. Journal of Curriculum Studies, 31(5), 501-522.

Roth, Wolff-Michael; Breuer, Franz & Mruck, Katja (Eds.) (2003). Subjectivity and reflexivity in qualitative research II. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung / Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 4(2), http://www.qualitative-research.net/index.php/fqs/issue/view/18.

Roth, Wolff-Michael; McRobbie, Cam & Lucas, Keith B. (1998). Four dialogues and metalogues About the nature of science. Research in Science Education, 28(1), 107-118.

Rubow, Cecilie (2000). Hverdagens Teologi. Folkereligiøsitet i danske verdener. Copenhagen: Anis.

Schober, Michael F. & Conrad, Frederick G. (1997). Does conversational interviewing reduce survey measurement error? Public Opinion Quarterly, 61(4), 576-602.

Selback, Bente & Sandøy, Helge (Eds.) (2007). Fire dagar i nordiske aviser. Ei jamføring av påverknaden i ordforrådet i sju språksamfunn. Oslo: Novus.

Spradley, James P. (1979). The ethnographic interview. Orlando, FL: Holt, Rinehart and Winston.

Stax, Hanne-Pernille (2000). And then what was the question again? Text and talk in standardised interviews. Proceedings of the 2000 American Statistical Association's Section on Survey Research Methods, 913-17.

Stax, Hanne-Pernille (2005). Når tekst kommer på tale. Studier af interaktion, tekst og opgaveforståelse i spørgeskemabaserede interview. PhD thesis, University of Southern Denmark.

Suchman, Lucy & Jordan, Brigitte (1990). Interactional troubles in the face-to-face survey interviews. Journal of the American Statistical Association, 85(409), 232-41.

Thøgersen, Jacob (2005a). Sprog og interview, interview og sprog. NyS, 33, 9-41.

Thøgersen, Jacob (2005b). The quest for objectivity in the study of subjectivity. Acta Linguistica Hafniensia, 37, 217-241.

Thøgersen, Jacob (2007). Det er meget godt som det er ... Er det ikke? Oslo: Novus.

Thøgersen, Jacob (forthc.-a). From attitudes to commonplaces—A discursive approach to attitude interviews, http://www.note-to-self.dk/docs/from_attitude.pdf.

Thøgersen, Jacob (forthc.-b). Coming to terms with English in Denmark—discursive constructions of a language contact situation. International Journal of Applied Linguistics.

Toulmin, Stephen (1958). The uses of argument. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Tyler, Stephen A. (1986). Post-modern ethnography: From document of the occult to occult document. In Clifford, James & George E. Marcus (Eds.), Post-modern ethnography: From document of the occult to occult document (pp.122-140). Berkeley: University of California Press.

Wetherell, Margaret (1998). Positioning and interpretative repertoires: Conversation analysis and post-structuralism in dialogue. Discourse & Society, 9(3), 387-412.

Wetherell, Margaret & Jonathan Potter (1992). Mapping the language of racism. Discourse and the legitimisation of exploitation. London: Sage.

Jacob THØGERSEN is assistant professor of Danish language at the University of Copenhagen. He wrote his PhD dissertation on Danes' attitudes towards the influence from English. In working with this he developed a particular interest in methods, analytical strategies and methods of presentation involved in the study of so-called attitudes.

Contact:

Jacob Thøgersen

Center for Internationalisation and Parallel Language Use

Copenhagen University

Njalsgade 128

DK-2300 Copenhagen S

Denmark

Tel.: +45 353 28167

E-mail: jthoegersen@hum.ku.dk

URL: http://www.note-to-self.dk/

Thøgersen, Jacob (2009). Cacophony: Ways to Preserve the Complexity of Subjects in the Research Presentation [62 paragraphs]. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung / Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 10(3), Art. 7, http://nbn-resolving.de/urn:nbn:de:0114-fqs090371.