Volume 10, No. 2, Art. 35 – May 2009

Photo-ethnography by People Living in Poverty Near the Northern Border of Mexico

Jesús René Luna Hernández

Abstract: People living in poverty have had little opportunity to express their feelings about the precarious situation in which they live. Most studies on poverty have focused on describing its most prominent characteristics, more often in a quantitative manner. This paper aims to explore the way in which people living in poverty conceptualize what they consider important and/or interesting in their everyday lives. Disposable cameras were given to 30 participants. In this paper efforts of 10 different photographers are reported. After the photographs were developed the participants were asked to comment on any aspect or situation portrayed in one or more photographs that could be considered interesting or important to them. Three main topics emerged: family, environmental problems and dangers, and community actions. Most of the photographs and commentaries centered on physically and emotionally-related themes, with a clear tendency to denounce unjust situations and to portray the manner in which the poor cope with the vicissitudes of daily life.

Key words: photo-ethnography; poverty; northern border of Mexico; agency; contamination

Table of Contents

1. Poverty and Photography

1.1 Poverty as described by the poor

1.2 Understanding poverty from the outside

1.3 From participants to activists

1.4 An alternative image of the poor created by themselves

2. Method

2.1 Context and participants

2.2 Procedure for obtaining photographs

2.3 Coding system and analysis of the photographs

3. Results

3.1 Thematic analysis of the photographs and their explanations

4. Discussion

5. Limitations of this Study and Future Approaches

Urban poverty is a main topic on political, economic, social and security agendas in our contemporary globalized world. The urgency and complexity of this phenomenon have required different strategies in order to be understood (CITRO & ROBERTS, 1995; DIAZ, HOBFAUER, LARA & LAVIELLE, 2001; ESPINOZA & LUNA, 2005; JENCKS, 1992; KANBUR, 2002). However, the way in which many studies of poverty typically have employed just one method for gathering data, typically by considering mostly objective economic aspects of poverty, has resulted, more often than desired, in a very fragmented view of the reality in which poor people live. Furthermore, most research on urban poverty consists of researcher-based judgments and assessments of the physical circumstances surrounding poverty, such as lack of access to basic services and goods, like drinking water and hospitals, thus failing to include the perceptions of the poor themselves. [1]

A number of studies have found that people in everyday discourse tend to assign most of the responsibility for the causes of poverty to the very people who live with it (DUDWICK, 2002; ELLERMAN, 2001; KUEHNAST, 2002). That is, the poor are responsible for their poverty. This line of thought gives support to what has been called the Culture of Poverty (LEWIS, 1988). [2]

This paper differs from previous studies that have directly linked the causes of poverty to the people who live in it. In some cases such approaches have justified existing governmental strategies and efforts to combat poverty that turn out to be very paternalistic and not at all emancipating, since they consider the poor as lacking initiative and a clear perception of their own lives (PRESIDENCIA DE LA REPUBLICA, 2006; VOS et al., 2001). In the research that I describe in this paper a different representation of the poor is shown, in which they clearly understand their situation and actively look for ways to improve the quality of their lives. [3]

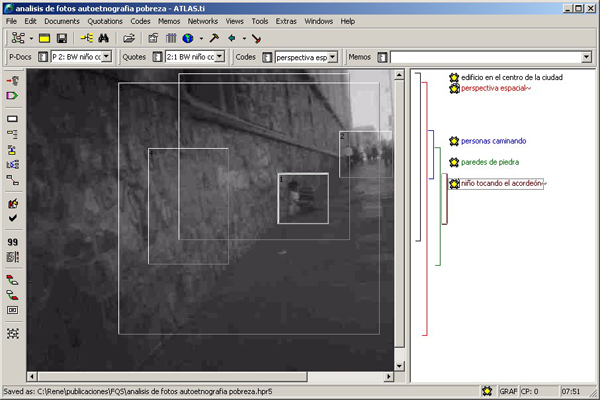

In order to understand more clearly the perspectives the poor have of their lives I have used a technique I have called Photo-ethnography; originally named Fotobefragung by Ulf WUGGENIG (1990). The original purpose of this technique was to "emphasize the active role in the research process of the respondents" (KOLB, 2008, p.4). For my purposes, this perspective on research allows people living in poverty to express themselves and to allow others to know their perceptions and points of view on everyday life in a way that is akin to other similar explorations (e.g., CAMPOS-MONTEIRO & DOLLINGER, 1998; NARAYAN, 2000). [4]

1.1 Poverty as described by the poor

The study of poverty is receiving an increasing amount of interest, with new developments in both the theoretical and methodological approaches emerging in the research community (RADLEY, HODGETTS & CULLEN, 2005; WANG, CASH & POWERS, 2000). However, there has been a paucity of research that has examined the perspectives of individuals living in poverty. One methodology used to address this gap is ethnography. [5]

Such approaches are valuable in that they attempt to clarify the mechanisms through which poverty evolves. However, in many cases the psychological variables and the social problems they deal with have been defined a priori by an external observer, who in most cases is not directly involved with the experience of living day to day in poverty [6]

In many cases, the point of view of the ethnographic researcher has always been situated outside of the context of the subjective experience of the people living in poverty. Although the researcher could live under the same roof with them for a long period of time, his or her most important task would be either to describe how the poor lived, how they looked for opportunities for survival, or to show how they would take advantage of available opportunities to improve their lives; that is, the ethnographer creates an "anthropology of poverty" (LEWIS, 1988; ZAMORANO-VILLARREAL, 2006). However, the interpretation of such findings has mainly been done from an objectivistic perspective on the social and cultural surroundings of the poor; thus leaving out vital information about the subjective world of the poor and the interpretations they have of their social, economic, and cultural situations. [7]

Furthermore, most of the recent research efforts on understanding poverty have focused on the analysis of several demographic variables on the well-being of the poor. The emphasis ceased to be on the culture of poverty and on the individual behavior of the poor; the macro-social aspects of poverty became the most relevant issues in its study. For example, most of these studies have focused on the effects of poverty on different indicators of quality of life, such as household characteristics, net income, and access to health services (DE SOTO & DUDWICK, 2002; JENCKS, 1992; KUEHNAST, 2002; KRUIJT, 1996; NARAYAN, 2000). The main purpose of such studies was the development of quantifiable indicators that could, somehow, help to "objectively" manage what they defined as economic development. [8]

Recently, in a relatively small number of studies, the subjective impact of poverty has been taken into account. Some of these studies have shown in detail the adverse consequences of poverty on the psychological well-being of the poor (KUEHNAST, 2002). They have also underlined the need for paying attention to the relationship between psychological variables and diverse social issues, such as the relationship between high levels of stress and anxiety and overcrowding (KANBUR, 2002), and of the relationship between violence and oppression (DUDWICK, 2002). Other research efforts have sought to establish the efficacy of several strategies of support for the poor, which would allow them to escape extreme poverty (MULLAINATHAN, 2004; VOS et al., 2001). A number of studies have focused on self-help approaches (e.g., ELLERMAN, 2001), utilizing socio-psychological approaches that aim to influence individual processes, such as modifying attributions toward poverty. These approaches aimed to stimulate the capacities the poor have for work and self-development through the development of self-efficacy (BANDURA, 1995). [9]

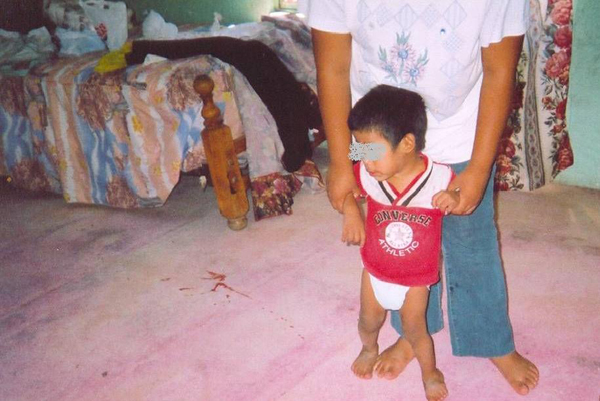

1.2 Understanding poverty from the outside

The existing division between those who define what poverty is and those who live within it is the result of serious deficiencies in the comprehension of how the poor perceive the contexts in which they live, the problems they face in their lives, and their worries about the future. Such lack of understanding has become an obstacle for carrying out any kind of effective plan to combat poverty in Mexico (DIAZ, HOFBAUER, LARA & LAVIELLE, 2001). Most government policies, both at the local and federal levels, as well as strategies from non-governmental organizations (NGOs), have not been designed to take into account the needs of the poor and how those needs could be satisfied to improve their quality of life. Most of the time the poor have to make do with what the agencies and institutions offer them based on the distorted ideas these organizations have about the nature of poverty (PRESIDENCIA DE LA REPÚBLICA, 2006). [10]

A very small number of publications have allowed the poor to articulate their worries, fears, and life perspectives. One such opportunity is portrayed in the book The Voice of the Poor: Can Anyone Hear Us? published by the World Bank (NARAYAN, 2000). This book includes the points of view, opinions and experiences of over 40,000 people from 50 countries. What is most significant in this book is that the poor themselves are the ones who express what they feel and what they think, without needing someone "translating" or "interpreting" such information. [11]

In a similar manner, a relatively new methodology being used in research settings, which I consider innovative and a potential generator of interesting data, is one based on the gathering of data focusing on both the visual experience and the recall of memories by the people living in poverty. An example of this is the work of CAMPOS-MOINTEIRO and DOLLINGER (1998), and ZILLER (1989, 1990), all of whom distributed disposable cameras to street children so that they could portray how they socially represented their own identities and the collective orientations they have toward numerous aspects of their everyday lives. Likewise, RADLEY et al. (2005), and WANG et al. (2000) asked homeless people to take photos of typical aspects of their daily lives. After the photos were taken the researchers collected stories told by the homeless about the images so that they could discuss the topics of exclusion, alienation, and isolation. [12]

1.3 From participants to activists

Through the lens of a camera, participants may focus many aspects of their subjectivity in alternative ways, channeling their views and reflections in different manners, turning into researchers of their own culture and of their own lives. They stop being merely spectators and become social activists, promoting change in the physical, social, and cultural environments in which they live (KOLB, 2008). The camera brings an empowering opportunity very few research strategies can offer; more so if their problems, desires, hopes, and worries can be expressed as narratives by generating meaning to the images they produce. [13]

1.4 An alternative image of the poor created by themselves

The poor are often victimized by the continual push from society to acquire the means for developing and living a worthy life. Almost all social scientists, including those outside of academia, have described only a relatively small proportion of the phenomena of poverty by quantifying its effects most of the time1) (SEN, 1992). Fundamental information and alternative perspectives are lost in this way, missing the opportunity to help develop new and better strategies for social change that could modify the complex circumstances that surround extreme poverty. The combined use of ethnography and photography (photo-ethnography) in poverty research provides a different option that allows researchers to consider the way in which perceptions, motives, and behaviors relate to each other and to the social structure in which poor people live. [14]

Furthermore, the use of photo-ethnography in social research precedes the sociological analysis of social structure (BARTHES, 1980). The use of photographs in social research involves a structural autonomy that allows it to get into the intrinsic nature of the message that is being communicated. Photographs capture and announce, amplify, and exhibit a message at the same time that they allow the researcher to get closer to the intimate spaces of people. [15]

To ensure that the participants in such studies become the very instruments that collect the information of interest, that is, to invite them to work as "self-ethnographers," is a strategy that can be used to understand the various problems, obstacles, and opportunities that the poor face every day. This approach permits the poor to get involved in the construction of strategies that could signify an improvement of their quality of life, allowing them to become empowered in more realistic and viable ways than those offered by outside agents who have not had the direct experience of enduring what the poor have to face everyday. [16]

The purpose of this study is to hear the voices of some of the inhabitants of poor and marginalized regions of Ciudad Juarez through the use of the photographs they produce and by the commentaries they made for such images. This will provide researchers with a deeper understanding of the perceptions those living in poverty have of the physical and social contexts in which they live through the use of a non-intrusive qualitative technique. [17]

Ciudad Juarez is a city with a population of approximately 1,300,000 inhabitants, located on the Mexico-United States border. Approximately 30% of the population are immigrants who have arrived from other parts of the country, especially from the southern provinces of Mexico, as well as from Central America (INSTITUTO NACIONAL DE ESTADISTICA, GEOGRAFÍA E INFORMATICA, 2003). Many of these immigrants work in the maquiladora2) industry, and reside in one of the many marginalized colonias, poor neighborhoods that are situated in areas remote from the downtown area, and lacking most basic services, such as running water, electricity, affordable and efficient public transportation, and police security. [18]

The participants in this study are residents of one such colonias, where the author was working on a research project with support from the federal government of Mexico (ESPINOZA & LUNA, 2005); which had as its objective the exploration of the social and psychological aspects of poverty in Ciudad Juarez. In the present study a total of 30 people (15 male, 15 female) were selected to participate. Half of the participants were invited to participate because they were known by the researcher and his assistants. The other half were selected because they lived in a colonia located in the western part of Ciudad Juarez, where most of the residents have very low incomes. They were interviewed in their homes. The participants’ ages ranged from 16 to 65 years. Their occupations were varied, from maquiladora workers to housewives, to domestic workers and newspaper sellers. All of them agreed to participate after the researcher explained to them that the data produced in the study would be confidential and used only for research purposes. They were informed that their participation was voluntary and that they could drop out of the study at any time, or they could also refuse to have their photographs published. They were also told that there was no involvement from any political, religious, or governmental association, other than the Autonomous University of Ciudad Juarez. [19]

2.2 Procedure for obtaining photographs

Each of the participants was given a disposable flash-included 27-exposure camera, and they were asked to take photographs over a 3-day period (even though in many cases more time was required) of anything, anyone, or any situation that was either interesting or important to them, in any place and at any time of the day. When the cameras were collected and the photographs developed, a set of photos was given to each participant as a gift for participating. It was in this phase of the research that they were asked to comment on any photograph they considered interesting or important. [20]

I would like to note here that the most ideal situation would have been to collect verbal information on the photographs at the same time that these were being taken, instead of waiting some time for them to be developed. However, budget limitations did not allow for this. [21]

2.3 Coding system and analysis of the photographs

After development of the film, each photograph was digitized and subsequently analyzed with the Atlas.ti software (BERMEJO, 1998; MUÑOZ-JUSTICIA, 2005). This allowed for the identification of specific aspects within each of the photographs, and to create different categories. A total of 676 photographs were examined.

Figure 1: Analysis of photographs using Atlas.ti [22]

The coding process was done based on grounded theory (GLASER, 1998; TRINIDAD, CARRERO & SORIANO, 2006), taking into account the open-selective-theoretical coding sequence. This coding sequence allows the researcher to progress from basic data as given by the participants to substantive theory, and from there to formal theory through different processes of theoretical integration. It is akin to going from the datum or incident to the code and then to the establishment of a concept (TRINIDAD & COLS, 2006). [23]

A total of 26 cameras were recovered along with the same number of interviews. Most of the interviews were carried out at the interviewees' homes, with a few exceptions that were carried out at the place of work of the person interviewed. This was the case of Juan3), a newspaper vendor who explained to me the nature and motivations of his photographs at the same time he was selling newspapers at a crossroad. [24]

3.1 Thematic analysis of the photographs and their explanations

Thematic grouping was done by using Atlas.ti, combining visual information with the associated narratives the people gave to them. The main resulting categories are shown on Table 1, beginning with the higher frequency categories. [25]

Three main patterns/themes emerged from the collection of photographs: (1) portraits of friends and family; (2) recognition of important places in the colonia, portraying problems and worries regarding the physical context of the community; (3) actions taken by the community members to solve such problems. Other minor themes emerged from the photographs, but occurred less frequently than the main ones. Some of the photographs of the minor themes were taken in other places around the city, especially in the downtown area.

|

Category |

Commentary |

Examples |

|

Family: Group portrayal |

Approximately half of the photographs showed members of the photographer's family. Around 30% (over 200) of the photographs revolved around this topic. |

|

|

Family: Children at home or nearby |

Some of these photographs (1%) are focused on children's everyday lives in their community. |

|

|

Family: Seeking medical attention for specific problems |

The mother of this child used the camera to ask for help with her child's special education and physical needs. |

|

|

Family: Children at school |

Some photographs show children at school, most of the time playing. |

|

|

Physical context: Environmental problems in their community |

A number of photographs show the physical context and its environmental problems. About 20% of the images related to this topic. |

|

|

Physical context: Health risks |

The photographer included the child's feet close to the contaminated water to denounce the lack of sewers and drains. |

|

|

Physical context: Important places in the community |

Some of the photographs show the very few areas designed for leisure and fun in the community. |

|

|

Community agency: Corrective actions taken by the members of the community |

A small number of photographs (about 5%) show how the community copes with problems to which the authorities are not paying attention. They show actions such as cleaning and repairing streets. |

|

|

Community agency: Reunions and gatherings by neighborhood associations and non-governmental organization (NGO) representatives |

In the same context, some of the photographs show how neighbors and NGO representatives gather to discuss problems and offer solutions. |

|

|

Poverty in other places |

There are few images that portray poverty in other parts of the city. The few with that theme were taken mainly in the downtown area of Ciudad Juarez. |

|

|

Decorative and religious objects |

There are very few images of inert objects, even though they are full of symbolism to the participant. |

|

|

Domestic animals |

A small number of photographs show domestic animals. However, animals appear in many of the pictures as a part of the physical environment. |

|

Table1: Main thematic categories from the photographs [26]

An example of the first thematic category is a photograph taken by the son of one female participant. She is joined outside of her house by the youngest members of her immediate family. They are all gathered around her, happily looking at the camera, as if inviting the looker to join them. We can see some details of the construction materials used in the house. The front wall is made up of pieces of wood that do not look to be very strong, and even though there is enough space between the wall and the house, this space does not seem to be a typical patio, a space for leisure or children's recreation. It looks like a place for work, with a lot of chairs and tin cans that are spread around it. [27]

However, the most significant aspect of the image is the fact that the children are standing around their mother: "These are my sons and daughters, my family."4) And the house is the perfect place to live in, as long as they are together: "Our house is a very modest little house, but we are very happy living in it because it is built with the effort that bind together those of our family, and that's why we do not worry, in our house we do not lack potatoes, beans, corn tortillas and a chicken leg, sometimes."

Figure 2: Family of the participant [28]

A second variation of the first category is shown in the next photograph, taken by the mother of a three-year old boy who could neither walk nor talk. He is being held by his aunt, so he can stand on his feet. The mother of the child explained to me that this picture is very important to her because it shows how both doctors and the health system have failed to help her and her son. She mentioned that the doctors kept telling her that her son had no problems at all, that all his cognitive and motor functions were alright, and that it was only a matter of time until her son would be able to walk and talk. She said: "Doctors in the Seguro5) do not pay attention to me."

Figure 3: Three-year old boy with motion impairment [29]

The participants were also worried about contamination and the bad conditions of their physical environment, especially of locations close to their homes, schools, and places of work. Their photographs reflect the frustration they feel when they see garbage thrown in empty fields that are very close to their homes, children having no other place to play than in dirty streets, and playgrounds full of dirty water and contaminated mud. In many of the interviews related to these pictures there were comments blaming the city authorities for not doing enough to clean up their neighborhoods, especially the places where children regularly play.

Figure 4: Garbage found close to the participants' homes [30]

Similar photographs show places that could represent a potential danger to the security of the whole community. These places could become sources of infections. Some of the interviewees said: "They throw dead dogs on the empty fields"; "They use the holes as hiding ground for those who take drugs," The authorities were also accused of not providing the community with the necessary and basic infrastructure they needed, such as paved roads, parks, trees, and running water6).

Figure 5: A puddle of dirty water [31]

The third theme that emerged from the narratives of the participants is the involvement of the community in coping with some of the most immediate and dangerous issues they face. Some of them are exemplified in photographs of people cleaning a street, fixing walls that are about to fall, and cleaning a field full of debris. Once more, there were comments generated by the photographs regarding the lack of involvement of governmental authorities in what people considered a long-forgotten responsibility: "If we don't fix it, nobody else would do it." The images that reflect the community’s action represent the little hope they have for a better future for all: "At least we can take care of our streets." These photographs were produced as a reflection of how people can work together, using in the most effective way the very scarce resources they have.

Figure 6: Actions performed by community members in order to improve the quality of the surroundings [32]

The poor are not just the passive victims of the oppressive capitalist system in which they live. The people who live in poverty have a dynamic way of looking at the world, many times centered on what is significant in their lives: family, well-being, and community. It is interesting to note that most photographs in this study were related to the participants’ closest physical, social, and cultural environments. Many perceived their participation in this research as an opportunity to highlight the troubles they face day to day, as well as a way of demanding action from the authorities, all in an effort to improve their way of life. [33]

The fight of the poor to achieve a higher standard of living is not positively interpreted by some social groups. As a result, when programs to fight poverty are developed, many of them become distorted and their objectives turn out to be very limited in range, sometimes due to the fact that the individuals who run agencies in charge of these programs, either governmental or NGO’s, assume that they know exactly what the people living in poverty need. Many of these policies and plans are based on trial-and-error strategies, or are based on what political decision-makers, with little or no first-hand knowledge, define as important for a community. As a metaphor for such a problem, imagine that we arrive at a new setting, as when visiting a city for the first time. One strategy to get to know exactly where we are would be to study a map or ask for directions from someone who thoroughly knows the city. As a general rule, we do not go stumbling though each street and square we find along the way. The same should happen in the endeavor to combat poverty. This is rarely done. For instance, the current government of Mexico has a program called Oportunidades, which in English means Opportunities (SECRETARIA DE DESARROLLO SOCIAL, 2009). Its aim is to help people who live in extreme poverty to survive. However, the financial support it gives to the poor is granted based on information gathered by objective instruments, without collecting subjective information that might help the agencies and programs to understand how poor individuals’ agency and resilience interacts with their strategies for survival. Researchers, as well as economists and politicians, should give voice to those who live day to day in poverty, those who carry on their shoulders incredibly heavy burdens, worries, and fears, and those who know how to stretch to the maximum the very minimal resources they have for survival. [34]

In this study, one of the most interesting findings was that almost none of the photographs had as themes acquisition of luxury items,, such as expensive cars, large houses, or places and situations that represent other, wealthier social strata. This could be interpreted in many ways. It may be that poor individuals are mainly worried about finding solutions to the most immediate problems they have in their environment. Similarly KOLB (2008) found a similar pattern in her study of the Hammam neighborhood in Morocco. To her, the themes in the photographs she collected denouncing environmental pollution came as a surprise; whereas for those who took the photographs contamination is a constant and worrisome reality. In each of these studies photographs represent opportunities for those who make political and economic decisions to carry out actions that could help people to achieve a healthy and dignified life, both in Morocco and in Ciudad Juarez. [35]

However, an alternative interpretation rests on the fact that by not taking pictures of things or places from other parts of the city, the poor in Ciudad Juarez find themselves in a bad situation, isolated and marginalized, most probably by structural causes. Some of these causes are located on a macro level, such as the collective public transportation is overwhelmed by demand, and is also very expensive. Other reasons are more individualistic, such as those related to the lack of an education that may give those living in poverty the chance to see what life could be like with an education and the opportunity to pursue that life. [36]

5. Limitations of this Study and Future Approaches

The insights in this paper highlight the most important themes in the lives of the people living in poverty, and how they represent them. But there are some limitations to consider. The first is that the conclusions and inferences drawn from these photographs and their associated narratives are speculative in nature. More in-depth research needs to be conducted, especially on the discourse that different contextual visions of the world could generate in the poor. The interviews could be more extensive and more in-depth. Also, a similar study could be carried out involving those who live in non-poverty conditions, including those who are wealthy, so that attributions toward poverty and wealth could be explored, among other issues. Furthermore, a critical analysis of the discourse of decision-makers, such as local politicians and entrepreneurs could be done, so that their discourse about poverty could be contrasted with that of the people they are supposed to help. This discourse can be integrated from writings, photographs, and spoken language. Aiming at an integration of qualitative and quantitative approaches, a questionnaire could be developed focusing on the three themes found in this study. [37]

It is critical that we understand how the poor deal with their financial situations and how they develop their social networks. To do so we must know how they perceive and interpret their world. However, if we inquire about their view of the world from a "questionnaire" or "structured interview" we would be losing a considerable amount of information. The use of an ethnographic method based on photographs allows us, at least partially, to see through the eyes of the "Other." Only then we can develop a more comprehensive, empathic, and compassionate vision of our own world. [38]

I appreciate very much the financial support this project received, during the year 2005, from the Graduate Studies and Research General Coordination of the Management and Social Sciences Institute of the Universidad Autónoma de Ciudad Juarez. Without it, this research would not have been possible. Also, I am thankful to the various students who assisted me during fieldwork.

I am indebted to my parents René and Ramona, who, since I was a child, instilled in me the notion of social justice. In a very special way I am grateful to Julia and Derek for all their support for my work in exchange for very little time spent with me. To Ian Clara, I can only say thank you for your help, professionalism, and enduring friendship.

Lastly, I dedicate this paper to the people who try to survive, day by day, in a context of poverty who lack most resources; whereas in the same city, through very different networks, billions of dollars come and go, both legally and illegally.

1) The ways in which poverty has been quantified, and the different perspectives on the measurement of it can be seen in the paper Sobre conceptos y medidas de la pobreza by Amartya SEN (1992). <back>

2) Assembling and/or manufacturing plants in which basic materials are temporarily imported for processing. After processing these materials are returned to the country of origin or sent to other places for further modifications (MENDIOLA, 1998). <back>

3) The names of participants were changed for security and ethical reasons. <back>

4) This is my translation from Spanish. To read the original please refer to the Spanish version of this paper, in this same issue. <back>

5) The "Seguro" is the main health system in Mexico. Its full name is The Mexican Institute of Social Security. <back>

6) For a better understanding of the limitations of the physical, social, and political contexts of the people who live in poor neighborhoods in Ciudad Juarez, as well as for a more profound discussion concerning the conflicts of interest they have with corporations and groups with strong economic agendas, please read ESCALONA RODRIGUEZ (2004). <back>

Bandura, Albert (1995). Self-efficacy in changing societies. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Barthes, Roland (1980). La cámara lúcida: Notas sobre la fotografía. Barcelona: Paidós.

Bermejo, Jesús (1998). Atlas.ti: de la organización de los datos al análisis y a la creación de nuevo conocimiento. Casi Nada Webzine, 19, http://solotxt.brinkster.net/csn/19atlas.htm [Date of access: 24.08.2008].

Campos-Monteiro, Julieta M. & Dollinger, Stephen J. (1998). An autophotographic study of poverty, collective orientation, and identity among street children. The Journal of Social Psychology, 138(3), 403-406.

Citro, Constance Forbes & Michael, Robert T. (Eds.) (1995). Measuring poverty: A new approach. National Academy Press, Washington DC, http://www.census.gov/hhes/www/povmeas/toc.html [Date of access: 21.11.2007].

De Soto, Hermine G. & Dudwick, Nora (2002). Eating from one pot: Survival strategies in Moldova's collapsing rural economy. In Nora Dudwick, Elizabeth Gomart, Alexandre Marc & Kathleen Kuehnast (Eds.), When things fall apart: Qualitative studies of poverty in the former Soviet Union (pp.333-378). Washington, DC: The World Bank.

Diaz, Daniela; Hofbauer, Helena; Lara, Gabriel & Lavielle, Briseida (2001). El combate a la pobreza: una cuestión de gobernabilidad. México: FUNDAR Centro de Análisis e Investigación, http://www.fundar.org.mx/secciones/publicaciones/pdf/doc-pobreza2001.pdf [Date of access: 27.03.2007].

Dudwick, Nora (2002). No guests at our table social fragmentation in Georgia. In Nora Dudwick, Elizabeth Gomart, Alexandre Marc & Kathleen Kuehnast (Eds.), When things fall apart: Qualitative studies of poverty in the former Soviet Union (pp.213-258). Washington, DC: The World Bank.

Ellerman, David (2001). Helping people help themselves: Toward a theory of autonomy-compatible help. WashingtonDC: The World Bank.

Escalona-Rodríguez, María Isabel (2004). Desarrollo urbano y clientelismo político: El caso de la Anapra en Ciudad Juárez. En Héctor Padilla (Ed.), Cambio político y participación ciudadana en Ciudad Juárez (pp 283-324). Ciudad Juárez: Universidad Autónoma de Ciudad Juárez.

Espinoza, Roxana & Luna, Jesús René (2005). Estudio exploratorio de las atribuciones causales de la pobreza en población pobre de Ciudad Juárez. México: Sivilla-Conacyt.

Glaser, Barney (1998). Doing grounded theory: Issues and discussions. Mill Valley: Sociology Press.

Instituto Nacional de Estadística, Geografía e Informática (2003). Chihuahua: Resultados definitivos. XII censo general de población y vivienda 2000. Aguascalientes: INEGI.

Jencks, Christopher (1992). Rethinking social policy: Race, poverty and the underclass. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Kanbur, Ravi (2002). A window on social reality: Qualitative methods in poverty research. In Nora Dudwick, Elizabeth Gomart, Alexandre Marc & Kathleen Kuehnast (Eds.), When things fall apart: Qualitative studies of poverty in the former Soviet Union (pp 9-20). Washington,DC: The World Bank.

Kolb, Bettina (2008). Involving, sharing, analysing: Potential of the participatory photo interview. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung / Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 9(3) Art. 12, http://nbn-resolving.de/urn:nbn:de:0114-fqs0803127 [Date of access: 12.09.2008].

Kruijt, Dirk (1996). Changing labour relations in Latin America. A policy evaluation of labour relations and trade unionism in Colombia and Peru. Amsterdam: Thela Publishers for the Ministry of Foreign Affairs (DGIS) and the Netherlands Trade Union Confederation FNV.

Kuehnast, Kathleen (2002). Poverty shock: The impact of rapid economic change on the women of the Kyrgyz Republic. In Nora Dudwick, Elizabeth Gomart, Alexandre Marc & Kathleen Kuehnast (Eds.), When things fall apart: Qualitative studies of poverty in the former Soviet Union (pp.33-56). Washington, DC: The World Bank.

Lewis, Oscar (1988). Nuevas observaciones sobre el continuum folk urbano y urbanización con especial referencia a México. En Mario Bassols, Roberto Donoso Salinas & Alejandra Massolo (Eds.), Antología de la sociología urbana (pp.226-239). México: Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México.

Mendiola, Gerardo (1999). México: Empresas maquiladoras de exportación en los noventa. Serie Reformas Económicas, 49, Comisión Económica para América Latina y el Caribe, http://www.eclac.org/publicaciones/xml/1/4571/lcl1326e.pdf [Date of access: 22.03.2008].

Mullainathan, Sendhil (2004). Psychology and development economics. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University, http://www.economics.harvard.edu/faculty/mullainathan/papers/PsychDev.pdf [Date of access: 17.10.2008].

Muñoz Justicia, Juan (2003). Análisis cualitativo de datos textuales con Atlas/ti. Barcelona: Universitat Autonoma de Barcelona, http://www.incluirong.org.ar/docs/manualatlas.pdf [Date of access: 15.04.2006].

Narayan, Deepa (2000). La voz de los pobres: ¿Hay alguien que nos escuche? Madrid: Banco Mundial-Mundi Prensa.

Presidencia de la República (2006). México: Presidencia de la República de México, http://fox.presidencia.gob.mx/foxcontigo/?contenido=27577&pagina=1 [Date of access: 27.03.2007].

Radley, Alan; Hodgetts, Darrin & Cullen, Andrea (2005). Visualizing homelessness: A study on photography and estrangement. Journal of Community and Applied Psychology, 15, 273-295.

Sen, Amartya K. (1992). Sobre conceptos y medidas de pobreza. Comercio Exterior, 42(4), http://www.flacso.or.cr/fileadmin/documentos/FLACSO/CLSen_-_Conceptos_y_medidas.doc [Date of access: 14.10.2008].

Trinidad, Antonio; Carrero, Virginia & Soriano, Rosa María (2006). Teoría fundamentada "grounded theory": La construcción de la teoría a través del análisis interpretacional. Madrid: Centro de Investigaciones Sociológicas.

Vos, Rob P.; Cabezas, Maritza; Aviles, Maria Victori; Cuesta, José; Komives, Kristin; Guimarães, João; Dijkstra, Geske; Helmsing, Bert & van Staveren, Irene (2001). Reducir la pobreza: Se puede? Experiencia con las estrategias de reducción de pobreza en América Latina. Stockholm: Swedish International Development Agency.

Wang, Caroline C.; Cash, Jennifer L. & Powers, Lisa S. (2000). Who knows the streets as well as the homeless? Promoting personal and community action through photovoice. Health promotion Practice, 1(1), 81-89.

Wuggenig, Ulf (1990). Die Photobefragung als projektives Verfahren. Angewandte Sozialforschung, 16(1/2), 109-129.

Zamorano-Villarreal, Claudia Carolina (2006). Ser inmigrante en Ciudad Juárez: Itinerarios residenciales en tiempos de maquiladora. Frontera Norte, 18(35), 29-53.

Ziller, Robert Charles (1990). Photographing the self. Newbury Park, CA: Sage.

Ziller, Robert Charles; Vern, Herman & Camacho de Santoya, Christina (1989). The psychological niche of children of poverty and affluence through auto-photography. Children´s Environments Quarterly, 6, 186-196.

Jesús René LUNA HERNÁNDEZ is a full-time professor in the Psychology Program in the Management and Social Sciences Institute of the Universidad Autónoma de Ciudad Juárez, in Mexico, and he is a PhD candidate at the Department of Social Psychology of the Universidad Autónoma de Barcelona, in Spain. His research interests include the social psychological studies on poverty, the impact of globalization on the poor, the relationship between urban and migrant communities, and new information and communication technologies, and the socio-psychological analysis of scientific knowledge production in the academic context. He has published in the International Journal of Psychology on the area of scientific productivity in international psychology, as well as on various national and international publications on the social psychology of poverty.

Contact:

Jesús René Luna Hernández

Programa de Psicología

Instituto de Ciencias Sociales de la Universidad Autónoma de Ciudad Juárez

Ave. Universidad y Heroico Colegio Militar s/n, Zona Chamizal, C.P. 32310, Ciudad Juárez, Chihuahua, México

Tel.: +52-656-688-3847 y +52-656-688-3800, extensión 3641

Fax: +52-656-688-3812

E-mail: jeluna@uacj.mx

URL: http://psicologiageneralreneluna.blogspot.com/

Luna Hernández, Jesús René (2009). Photo-ethnography by People Living in Poverty Near the Northern Border of Mexico [35 paragraphs]. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung / Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 10(2), Art. 35, http://nbn-resolving.de/urn:nbn:de:0114-fqs0902353.