Volume 11, No. 2, Art. 1 – May 2010

Retirement Transition in Ballet Dancers: "Coping Within and Coping Without"

Irina Roncaglia

Abstract: Retirement transitions in ballet dancers have been under researched. The purpose of this paper is to investigate the experiences of career transition in ballet dancers, from a life course perspective. Drawing upon existing transition models (SCHLOSSBERG, 1981) and sport literature (TAYLOR & OGILVIE, 1994), the paper investigates how ballet dancers cope (or not) with the transition and explores the different factors influencing the coping process. Qualitative analysis of semi-structured interviews from fourteen international ballet dancers were used adopting an idiographic approach through interpretative phenomenological analysis and tenets of grounded theory methodology. The results identified a main theme "Coping strategies: Coping within & without" and eight sub-categories: Denial, alienation, indecision, severance, acceptance, letting go, renegotiation and reconstruction. The individual can experience different responses, which trigger different coping processes and subsequently different types of support are sought. Finally the paper briefly discusses some of the implications for future career development and career guidance.

Key words: retirement; transitions; ballet dancers; coping strategies; career development; life span; life course

Table of Contents

1. Adaptations to Retirement: An Introduction

2. SCHLOSSBERG's Framework and TAYLOR and OGILVIE's Model

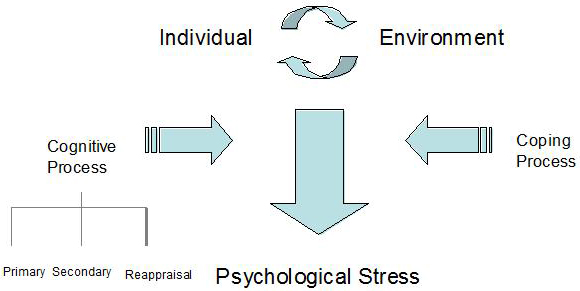

2.1 SCHLOSSBERG's framework

2.2 TAYLOR and OGILVIE: A conceptual model

2.2.1 Coping mechanisms: Resources and skills

2.2.2 Social support

2.2.3 Pre-retirement planning

3. Methodology

3.1 Procedures

3.2 Participants

4. Results

4.1 Coping strategies: Coping within & coping without

5. Reflections and Conclusions

1. Adaptations to Retirement: An Introduction

In the last century retirement has resulted in the identification of this transition as a new stage of life with its own name, dedicated organisations, magazines and its own financial, legal infrastructure (SAVISHINSKY, 1995). According to anthropological studies, when individuals transition from one stage to another, they make use of ceremonies that assist them to transform their identities, investing in the deep cultural meaning of the "passage". Anthropologists have studied these rites of passage amongst different cultures and recognised that tensions and unhappiness are experienced if appropriate time and meaning is not devoted to these events (VAN GENNEP, 1960; SAVISHINSKY, 1995). In the words of MANHEIMER (1994, p.44) "retirement ... is still a rite of passage we have not figured out how to celebrate" and it is seen as the end of productive engagement both economically and socially. This perhaps is because retirement underlines the end of an era and focuses on the past rather than the future, thus important issues remain unresolved. [1]

Dancers who suddenly stop working might have fewer opportunities to celebrate such rites of passage, immersed in worries about the future or sometimes still living with the mistaken belief that they will get back into the profession. The study was previously presented within the context of the "Retirement transition model" by Irina RONCAGLIA (2006, 2008). The model highlighted different factors which can influence how retired dancers experience the transition to an alternative occupation. The model identifies six different themes which were highlighted as significant elements. These are: reasons for retirement, social support, emotional responses, coping strategies, contextual factors and floating resolutions: the sequels. Retirement transitions can be difficult and characterised by crisis manifested by psychopathology, occupational crisis, substance abuse and social difficulties (TAYLOR & OGILVIE, 1994). This paper explores the experience of retirement transition of fourteen international ballet dancers and identifies different factors through qualitative analysis which have influenced their coping processes. It uses elements of Nancy SCHLOSSBERG's framework and Jim TAYLOR and Bruce OGILVIE's model to address the coping mechanisms used by this occupational group. [2]

2. SCHLOSSBERG's Framework and TAYLOR and OGILVIE's Model

In order to contextualise this study I will now present Nancy SCHLOSSBERG's framework and the four factors which relate to how individuals cope with transitions and the five step conceptual model developed to account for the athletic retirement process by Jim TAYLOR and Bruce OGILVIE (1994). [3]

SCHLOSSBERG, WATERS and GOODMAN (1995) suggest that despite the identification of general patterns as proposed by HOPSON's model (1981) individual differences occur in the responses to transitions. HOPSON's model, known as the transition cycle is a model of psychological processes experienced through transitions which includes events as well as non-events (i.e. not gaining a principal role or receiving a promotion) that can require an adjustment in an individual's behaviour and relationships. He identified seven psychological phases which an individual will experience when faced with a transition. Individual differences will occur for each person according to a range of variables. These variables include deficits and limitations as well as resources, personal attributes and capabilities. SCHLOSSBERG's model (1981) offers a framework where four main factors affect how individuals cope during transitions. These have been identified as: 1, situation, 2. self, 3. support, and 4. strategies. These factors are considered as a cluster of multiple resources, assets, liabilities and limitations, constructed as a balance between positives and negatives. They are fluid and changeable. I will briefly describe each one in turn.

The first factor, the situation, refers to eight key dimensions identified as the trigger, the timing, the source, the role change, the duration, previous experience, concurrent stress and assessment of the transition (SUGARMAN, 2001, p.150). These variables have been considered the most significant factors in the transition process. This can be questioned because although the timing may be categorical, its duration—how long the retirement process lasts—depends also on individual experience and therefore on the "self" rather than exclusively being a characteristic of the situation.

The second factor, the self, includes personal characteristics such as gender or role a person is ascribed or acquired, age, status and state of health and all the psychological resources available to each individual, which includes ego development, personality traits, outlook, commitment and values.

The third factor, support, ranges from social support such as family members to more interpersonal transactions which can include personal values and priorities. Sources of support can also range from intimate relationships to a network of friends. Ballet dancers often lack this type of social support, challenging some previous research, which suggests that athletes receive considerable support amongst family and friends. Ballet dancers who do receive such support seem to have an easier transition (WERTHNER & ORLICK, 1986).

The fourth factor of coping strategies is linked to the third factor. These strategies can include primary or problem focused strategies and secondary or emotion focused strategies (HECKHAUSEN & SCHULZ, 1995). The former relate to the environment whereas the latter relate to internal responses to external circumstances. SCHLOSSBERG (1981) noted that an internal source of coping such as a change of values that leads the individual to other interests provides an internal impetus for change that can facilitate the transition experience. [4]

It is recognised that adulthood is characterised by periods of stability and change and that the individual subjective experience, and the perceived meanings of that experience can exert and shape how people respond and act to changes. SCHLOSSBERG's framework helps us to visualise the dynamic and interactive nature of these contributing factors, which have to be explored in a non-linear and non-progressive way (CHARNER & SCHLOSSBERG, 1986). [5]

2.2 TAYLOR and OGILVIE: A conceptual model

TAYLOR and OGILVIE's (1994) conceptual model draws from previous theoretical work within and outside sport. Their five step model examines adaptations to the athletic retirement process throughout its entire course. It identifies four different causes which initiate the retirement process. These are: 1. age, 2. deselection, 3. injury and 4. free choice. Age is considered as one of the main factors, affecting the level of performance and therefore inducing considerations of retirement (TAYLOR & OGILVIE, 1994). Little research has considered the relationship between age and ability in terms of a) artistic maturation in the performer and b) physical abilities. It may be that age plays a relatively minor part in the decision making process. Deselection includes behavioural changes within fellow dancers, coaches, directors and ballet masters. Hints are made during casting sessions, less attention is given to corrections during daily training and a sense of slow exclusion from the group is experienced. These are all parts of the deselection process, which can be considered as an example of transition in response to a non-event. Injuries are part of athletes' and dancers' careers and can be associated with distress manifested in depression, substance abuse and suicidal attempts. A general lowered state of well-being is experienced by injured dancers particularly where a chronic injury has caused the end of their career. Free choice is a desirable factor which, because of its positive attributes, has been neglected in the current literature. Dancers may seek new challenges in previously unattended areas of their life, such as building a family, or developing new interests outside the ballet world. These processes then influence the periods of adaptation to retirement such as developmental factors, self and social identity, perceptions of control and tertiary contributors. The available resources are further contributing factors that will affect the response to retirement. Depending on the type of adaptation and available resources, outcomes are expressed either as a healthy career transition or a retirement crisis that identifies four different areas: psychopathology, substance abuse, occupational and family/social problems. These may require professional counselling and/or extensive periods of readjustment. Furthermore depending on the complexity of the crisis experienced by retired dancers during the transition, the reasons for their retirement, the emotional impact and the contextual factors in which the transition is taking place, different coping mechanisms will be sought by the individual (RONCAGLIA, 2006, 2008). Within the available resources which can affect how an individual respond to the retirement transition, TAYLOR and OGILVIE identify three main areas: coping skills, social support and pre-retirement planning. For the purpose of this article I will cover some of the issues related to these three areas. [6]

2.2.1 Coping mechanisms: Resources and skills

Coping mechanisms have their time and space and can assist the individual during the adjustment process, depending on the changeable relationship between situation-coping and response-situation. The impact of a stressful life event such as retirement has been researched within two main traditions. The first relies on coping resources, dispositional qualities and social locations, which all focus on the buffering effect of social support. The second relies on the different characteristics of the change such as undesirability, uncontrollability, unpredictability and magnitude of the event in question which builds on the accumulated experience of the individual prior to the impact of retirement. [7]

LAZARUS and FOLKMAN (1984) are the proponents of a definition of psychological stress which is the outcome of a relationship between the individual and the environment that is perceived as challenging or as exceeding existing resources and consequently endangering their state of well-being. Through cognitive and coping processes the individual resorts to different resources.

Illustration 1: Psychological stress model adapted from LAZARUS and FOLKMAN (1984) [8]

FOLKMAN, LAZARUS, PIMLEY and NOVACEK (1987) suggested two central processes that determine the outcome of a stressful experience in a given situation: a cognitive process and a coping process as illustrated above. The first includes three basic forms of appraisal: a primary appraisal where the individual assesses the significance of the situation and gauges whether the situation is positive, stressful or irrelevant. A secondary appraisal, which is an assessment of coping resources and options available depending on the situation appraised (e.g. threat, challenge or loss). The third is the notion of reappraisal, which is a state of being "on guard" as processes are in constant motion due to possible changes in the environment and developing coping skills. Emotional reactions need to be mastered and this is when cognitive appraisals leave the stage to different forms of coping processes. A problem-focus behaviour is directed at altering the problem that is causing the stress; in the case of a ballet dancer's retirement this might entail reducing anxiety provoked by an unknown future and by finding information on other avenues that may be pursued such as retraining programmes. Emotion-focus behaviour will see the individual engaging in cognitive operations such as reappraising the situation as an acceptable part of a dancer's life and therefore less threatening. [9]

More recently HECKHAUSEN and SCHULZ (1995) suggested a similar distinction between primary and secondary appraisal. The first directed to the external environment or situation is referred to as "primary control". This aims at changing the environment in such a way to fit the demands of the individual. The second or "secondary control" is targeted to the internal self or individual and aims at developing or altering the perceived situation, helping to channel resources in order to challenge irrational beliefs and expectations. Although these are two well defined models, shifts occur throughout the life course, depending on the constraints (liabilities) and resources (assets) encountered. Coping with crises throughout life is a cumulative learning process and survival strategies are adapted accordingly in managing these crises (BLAIKIE, 1999). [10]

To universally define "social support" is still problematic, especially within a qualitative approach where support acquires social, cultural and unique individual meanings within different cultures and social contexts. However TAYLOR (2003, p.235) attempted to define it as:

"Information from others that one is loved and cared for, esteemed and valued, and part of a network of communication and mutual obligations from parents, a spouse or lover, other relatives, friends, social and community contacts such as clubs, or even a devoted pet" (p.235). [11]

In order for a stressful event to result in positive outcomes, there must be a fit between the demands of the stressors and the functions of coping (CUTRONA, 1990; CUTRONA & RUSSELL, 1990). According to their "Optimal stress matching theory" a distinction between different types of events, their appraisals and the types of coping strategies need to occur in the individual in order to identify which coping strategy is going to be effective with a specific type of stressful event. After conducting a review of over 40 studies they suggested that when people are faced with uncontrollable events, and by "uncontrollable" events they referred to the extent to which an individual has control (or no control) over the outcome, they will require social support that fosters emotional support. In this instance emotional support involves the opportunity to ventilate emotions, re-evaluate the severity of one's losses, or experience positive emotions that can derive from sources which have not been lost because of the occurrence of the stressful event. For controllable events, they reported that social support components will foster informational and esteem support. Informational support deals with advice, information and works by reinforcing an individual's level of competence. [12]

For dancers and athletes, the primary social support system might often be derived from the work environment as a consequence of the total immersion in the activity at psychological and social levels. Furthermore, athletes and dancers might suffer from the absence of a support system outside their working environments. The exclusion by co-workers and colleagues can be a product of their own fear of retirement, given the reality of a short lived career. As a consequence the dancer and the athlete approaching retirement will slowly be "outcast" or treated as an outsider by members of the company. [13]

According to TAYLOR and OGILVIE (1994) and SCHLOSSBERG (1981) pre-retirement planning appears to have the greatest influence in the quality of adaptation to retirement. Although the incorporation of pre-retirement planning programmes is becoming increasingly part of organisations such as the Dance Career Development1), there still appears to be a resistance among those institutions that see such educational programmes as a threat to the devotion needed for a vocational and professional career. In the dancing world, money that is invested in supporting retirement transitions could be offset by the costs related to the impact on mental health services brought on by chronic injuries, substance abuse and/or depression. Time taken for workshops and reading materials should be seen as contributing elements in the establishment of a future career and the opportunity to enrich the organisation with new thinking. [14]

Past research in the field of coping with transitions concentrated on defining typical patterns of responses (e.g. HOPSON, 1981) and measured the length and impact of such changes. It has primarily focused on determining general responses to losses or crises with a predictable pattern of reactions that can then be applied to inform transition management interventions. [15]

Little empirical research and qualitative explorative studies at present have been devoted to this area with the exception of some studies in the athletic population. A qualitative approach to the study of retirement in dancers may assist us in better understanding how they really coped (or not) with the transition, what was the meaning of their retirement from a coping perspective and may give suggestions on what kind of support services and resources might be helpful in reducing high level of distress, depression and potential occupational and social problems. The study aims to shed light on the meaning of retirement in dancers and how and when if at all coping skills are adopted during the transition. [16]

Knowledge and experience are deeply shaped by the subjective and cultural perspectives of each individual (YARDLEY, 2000). The present study adopted an idiographic approach using elements of interpretative phenomenological analysis (IPA; see SMITH & OSBORN, 2003) with underlying criteria of grounded theory methodology (CORBIN & STRAUSS, 1990). The main aim of IPA is to explain the meaning of participants' experiences recognising the dynamic process of the research, where the researcher plays an active role as an interviewer, in getting an insider's perspective of participants' experience of their world. This is also achieved via a process of interpretation. The interpretative component aims to understand and attempts to make sense of the relationship between the participant and their contexts through a psychological framework. The criterion adopted from grounded theory was to ensure that interpretations remained grounded within the participants' descriptions where ideas, conceptualisations and categorisations processes are emerging, explored and woven back from the data into the fabric of the theory. A semi-structured interview format (see the Appendix) was employed to collect individual data from the whole sample. Interviews were tape-recorded and transcribed verbatim. All interviews lasted between one to one and a half hours. [17]

The interpretive process of coding becomes the means whereby the data are broken down analytically. Its main purpose is to understand the development and interpretation of findings that are reflected in the data, through systematic ways of thinking and interpreting phenomena. The process of analysis can be reduced to three broad stages:

the reduction of text,

the exploration of text,

the integration of the investigation. [18]

These stages all involve interpretations, and at each stage a more abstract level of analysis is achieved. The reduction of text stage includes a process of initial analysis which allowed the general "tone" of each interview to be captured prior to transcription and the determination of an initial interpretation of the retirement experience. Verbatim transcription of interviews, coding and dissection of the text into manageable and meaningful text segments with the use of coding followed. This was completed on the basis of the theoretical interests guiding the research questions, and on the basis of issues that were grounded in the text itself. The exploration of text (Stage 2) through open-coding allowed events and actions previously identified to be given initial conceptual levels so that similar events or actions could be grouped together to form initial categories. Adopting axial coding was the next step which allowed the agreement between two or more categories that eventually gave form to a larger group of categories sharing the same underlining characteristics. Axial coding also implies a further development and refinement of existing categories. The selective coding process follows through which all the different categories are unified around main themes. The synthesis of the investigation (Stage 3) includes a process of integration within a higher level definition which allows returning to the original research questions and the theoretical interests underpinning them. Any arguments and discussion grounded in the data would then be addressed as well as the patterns which emerged from the exploration and analysis of the text. The extracts below illustrate the analytical process that was undertaken, which developed in these examples, into the main theme of "Coping within & coping without".

|

Units of text (Step 1) |

Initial codes (Step 2) |

Categories (Step 3) |

Categories identified as basic concepts (Step 4) |

Clustering of main themes and sub-categories (Step 5) |

|

"I know I was not happy with the situation I was in there and I couldn't figure out why. I knew the time of retiring was coming ... to move on ..." (40-43, Christine) |

Realisation of end of career Feelings of unhappiness Needing to cope with a possible change Beyond her control An inevitable phenomenon |

Needs Drives Realisation Confusion Control Causes Abilities |

Finding new situations Accepting the change Sense of no control Inevitability of event External to the person "me" |

Reasons for retirement Voluntary/involuntary Age/coping within "I" Coping strategies: "without" Planning |

Table1: Data analysis and coding (extract examples) [19]

The depth of an individual case often shows the completeness of the interpretation and the complexity of the phenomenon observed. For this reason alone a small number of cases seemed appropriate for this study, and purposive sampling selection was initially adopted. A total purposive sample of fourteen (N=14) international ballet dancers was recruited for this study. Eight females and six males, age at interview ranged from 28 to 56 yrs (M= 40.57, and SD= 7.84). The age at retirement ranged from 21 to 49 yrs (M= 30.5, and SD= 5.9). All participants were Caucasians except one who was Asian. Five participants were single, two were married with no children and seven were married with children. Participants were recruited as I progressed further with the research and the selection was guided by the need to have a range of people that met my criteria: range of age since retirement, length of time employed as professional dancers, dancers who were both single and in a relationship to examine the role of significant others. All participants were informed about the interviews, their length, consent and confidentiality criteria prior to each interview. All interviews followed the British Psychological Society Ethical guidelines.2) [20]

In this section of the paper I present the results from the data analysis of participants' interviews. I focus on the experience of retirement after the actual event has taken place illustrating how the main theme of "Coping within & coping without" and their subsequent sub-categories have emerged from the analysis. [21]

4.1 Coping strategies: Coping within & coping without

The data analysis identified the main theme of "coping within and without" which depicts the experiences of retirement transition for this occupational group after the event has taken place. The main theme emerging from this study tries to encapsulate the process of coping that includes an internal (within) and an external (without) adjustment, both necessary for optimal functioning throughout post-retirement. The dancer has to adjust as a person—the "I"—and as a dancer—the "me"—and takes into consideration the processes of change occurring through his/her social structure. The "I" and the "me" can be compared to the "self" and the "situation" of SCHLOSSBERG et al. (1995) which are then both related to the strategies variable and how the individual is coping. Eight sub-categories identified factors which affected participants' coping abilities. The framework depicts different coping styles, planned and unplanned retirement, the sense of control and choice exercised on the context of coping responses and the dancer's identity which influenced the way participants coped with the change. The results identify not only coping styles but coping resources which contribute to or inhibit the coping experience. As suggested by SUGARMAN (2001), coping is best thought of as a process rather than a single response, hence this notion of coping as a dynamic movement between the situation-person-situation. [22]

The eight psychological processes were identified as sub-categories with the following definitions:

denial,

alienation,

letting go,

isolation,

severance,

acceptance,

renegotiation,

reconstruction. [23]

These sub-categories were experienced either in isolation or at times in combination within the same individual, they were non-sequential; i.e. at any point the individual could have experienced one or more psychological processes depending on the dynamics of his/her social structure and his/her personal attributes. HOPSON and ADAMS (1976) talk about a transition-cycle where different stages are identified in any given transition, and although dynamic in its nature they always start from a stage of immobilisation and progress through to the final stage of integration. The eight sub-categories identified by this study relate to how participants may have coped with the change. Most strategies were applied according to the changing situation and the demands posed by that specific situation (SCHLOSSBERG et al., 1995). Some participants coped by isolating themselves from the source of distress; others coped through accepting the change and renegotiating their identity with alternative roles. Following COLEMAN and GROOMBRIDGE (1982), coping is here identified more as a process of dealing with the situation through change rather than coping with the change. [24]

Denial

Denial is a psychological process which depicts the inability that something, an event or an action has actually taken place. Amy retired at 30 years of age. She illustrates how, around two years prior her actual retirement, she had found herself being "stuck". Amy tried to cope with this feeling by auditioning for other ballet companies but with no success and therefore continued to experience uncertainty.

"... And about that time, that eight years, I did some more auditions and I couldn't get anywhere. Like I said ... so I just [got] this stuck feeling. Also, that I did not know what to do after giving up ballet ..." (112-114, Amy). [25]

Coping for Amy meant adopting alternative coping mechanisms where she refused any social contact with other people, almost as if denying her identity to others. This represents a defensive coping mechanism that sees the individual withdrawing in the self and using humour as an alternative strategy. She talks about the cause of distress as an unknown identity, the "it".

"... Anybody that you call people [laughter] I just didn't ... I couldn't talk with people basically and it is hard ... just couldn't talk ... I kind of ... I didn't talk to anybody so I didn't know what to do with it ..." (278-280, Amy). [26]

Alienation

This sub-category emerges from a sense of feeling external to the group, in the case of this study the Ballet Company. Luke who retired at 35 years of age, illustrates how he experienced and coped with the situation through a sense of alienation. He also illustrates how he reflected on future possibilities and future careers.

"I really had to think very hard because I didn't think I had any skills. Because I grew up in an environment where dancers were thought to be dumb and so I thought I was dumb" (336-338, Luke).

"I didn't think it was going to be a big issue ... well ... I was [in] for a big surprise when I did make the transition. I didn't realise what a great part of my life my career was, until I didn't have it. Until I wasn't a dancer. And then the doubts started to come in, who was I, if I wasn't dancing, who was I"? (229-233, Luke) [27]

Letting go

Letting go is described as the inability of the individual to disengage from the activity which in this study is the ballet dancing profession and specifically performing. As part of the coping strategies adopted by the sample, letting go becomes a significant stage where the individual learns to detach himself/herself from the activity. As found by HOPSON and ADAMS (1976), this analysis identifies different coping processes of letting go and acceptance that allow the individual to move on. These are identified in HOPSON's model as mid-points of the transition, whereas BRIDGES (1980) talks about letting go as the initial stage of a transition. Similarly, in this study letting go is adopted by some participants early on in the retirement process. For example Luke wanted to be in control of his situation and planned for the actual event of retiring:

"... I realised I was getting older and I wanted to make the choice that I stopped when I still felt that I could do everything and I was in control to make that decision. It was my choice. Rather than having watched everybody else and other people leaving the company to be pushed out ..." (36-41, Luke).

"I constantly felt not ready for this, but I didn't want it to be as you said, sudden. So that's why the planning came in. Because I didn't want it to be a shock to my system, that I was being told that I wasn't worth any more or that I wasn't good enough to do something ..." (575-578, Luke). [28]

Isolation

Isolation is experienced by some participants as a stage where their identity as a dancer is questioned. There seems to be a process of disconnection from a place, a person(s) or an event. Luke illustrates when he talked about the emotional effort he had to employ to detach from the ballet environment where dancers are thought to be un-educated. He seems to experience and cope with the situation through a sense of Isolation as he reflected on the future possibilities for an alternative career.

"I really had to think very hard because I didn't think I had any skills. Because I grew up in an environment where dancers were thought to be dumb and so I thought I was dumb" (336-338, Luke). [29]

Marianne, who retired at 34 years of age, illustrates how she coped through isolation, but also slowly letting go and renegotiating her new identity.

"My identity is I think also how people see my identity that has changed. My identity of course in a sense that I feel slightly different, I do not see myself any more as a dancer, which is a change. I also don't introduce myself as an ex-dancer ehm ... and I try to avoid coming on to the topic outside work on dance unless they ask it specifically ... I feel they are interested in it. Otherwise I kind of skip over that, not because I am embarrassed, I just don't feel it is necessary" (94-100, Marianne). [30]

Severance

This sub-category is identified as a way of detaching oneself completely, disconnecting psychologically and physically from a specific social context. Christine retired at 32 years of age. She illustrated another example of an alternative coping mechanism by going to another country and refusing to think about anything specific, especially denying the responsibilities of "doing class" which is an important element of a dancer's routine in order to maintain physical fitness. During this period of trying to cope, she was isolated, she "cut" people away, and everything associated with dance out of her life. A process of severance can be identified as a way of coping through anxiety and distress.

"... I left for six months, came to London [from Birmingham] went to Italy for about a week to clear my head, did not think about doing class, did not think about doing anything at all, I just needed to cut them ..." (27-29, Christine). [31]

When faced with an injury, a process of severance is experienced by this participant:

"... And so I was 33, by then my back was playing up so badly and I just thought I can't risk having another herniated disk and literally bearing through [out] the whole thing again. So I literally more or less stopped over night ..."

"... I just could see that it wasn't good for me what I was doing and I stopped very, very quickly ..." (63-66, 68-70, Florence). [32]

Acceptance

When the ego and self-concept are attacked, different coping strategies are employed in order to deal with the damaged self-esteem. Repairing this damage means taking control of the situation—problem focus coping—trying to alter it accepting and adapting to a different role through Acceptance. It also means removing the "self"' from the source of the threat and/or re-interpreting one's own identity through an emotion focus coping process. Florence, retired at 33 years of age due to a back injury. She illustrates how she had to adopt a coping process which included accepting the limitations of her physical abilities.

"... And so I was 33, by then my back was playing up so badly and I just thought I can't risk having another herniated disk and literally bearing through [out] the whole thing again. So I literally more or less stopped over night ..."

"... I just could see that it wasn't good for me what I was doing and I stopped very, very quickly ..." (63-66, 68-70, Florence). [33]

Expectations also emerge from the dancer him/herself, who expects a certain level of understanding and acceptance from the people that are close, like a partner or family member. High family ideals had to be faced by Marianne mentioned earlier, on a daily basis as she experienced her retirement.

"... it did change something in their eyes, also because I felt that the identity or the status of the dancer, for them was somehow not as high as the status of what my brothers were doing for instance, and I think that it is still the case" (332-335, Marianne). [34]

Renegotiation

Renegotiation is the ability to enter into a dialogue with the self and others and the ability to revisit existing roles. This sub-category acquires importance when the bereaved person remembers in a constructive and positive way the deceased through renewed energy and nostalgic recollection that function as comforting elements to the bereaved through the period of loss. Diana retired at the early age of 24 years, expressed how having been a dancer is still very much part of who she is: the core identity which has been refined and accommodated in light of these changes.

"... Is still very much part of it ... and me [it] had been very strange [to] rediscover that. And it feels all right ... so that ... what I was ... (a dancer), that is what I still am ... and [is] still in me ..." (494-495, Diana). [35]

Similarly, Florence expressed her ways of coping in accepting that part of her past, (and being a dancer), as elements of what she is, reminiscing about dancing and enjoying going to the ballet.

"... For me ... bit of me that I still connected to my past and I do accept that I do love it. I do love going to the ballet. I love watching it still and I found it very exciting as well. And I feel very privileged that I was able to do it and that I am still able to have this connection with the dance ..." (273-276, Florence). [36]

Reconstruction

Reconstruction is understood here as the ability to build and develop new roles. Retirement from dance can be a source of identity crisis, when the dancer's identity is very pronounced. These findings correspond to results from related research in athletes and other professions (WERTHNER & ORLICK, 1986). The individual therefore thrives for a reconstruction, a personal (within) and a social self (without) through an adjustment into alternative life styles and roles. The process of reconstruction entails understanding oneself again, almost reinventing one's own identity through a different social environment and alternative goals. Luke gives an example:

"So I had [to] sort of manipulate the way I feel about my own self-image. As it were ... my self-confidence, my self-esteem and try to re-understand my self and almost re-invent myself ..." (253-255, Luke). [37]

Grace, who retired at 46 years of age, illustrates how she acknowledges and accepts emotionally this process of reconstruction. She acknowledges that the "dancer" is still part of what she is, and she reappraises the situation (FOLKMAN et al., 1987) taking this into consideration.

"... I suppose a certain part of me even now to an extent I am the dancer. You know you can't spend over 40 years of your life and suddenly [it] is like turning a light off, it doesn't disappear ..." (212-214, Grace). [38]

Although all unique in the way they have expressed their coping responses, either overtly or covertly, it appears that some individuals needed to reconsider their psychological contract with their past identities. Some participants of this study accepted letting go without fear, and yet renegotiated an identity through continued meaningful changes and through the development of self-enhancement and self-empowerment. [39]

5. Reflections and Conclusions

This article illustrated and discussed the results from a study on the retirement transition of ballet dancers. Specifically it focused on the coping strategies adopted by retiring ballet dancers. It captured each participant's reality and experiences focusing on exposing retirement as it is lived by the individual ballet dancer. It suggested that it is a multidimensional and multidirectional process and that several factors, internal and external to the individual can influence his/her ability to cope during this process. [40]

The main theme presented in this article is "coping strategies: Coping within & without" which illustrates the type of adjustment necessary for this occupational group when they are faced with a loss of structure and daily routines which were provided by their dancing environment. There is a process of having to cope with a reconstruction of a personal identity—coping within—but also through an adjustment as a social self—without: the person as the "I" and the person as the "me". Eight sub-categories were identified: denial, alienation, letting go, isolation, severance, acceptance, renegotiation and reconstruction. The sub-categories emerging from the main theme—coping within & without—have been determined by whether the coping mechanisms stemmed from a planned or unplanned retirement, which further influenced whether the experience was positive, negative or both. This also depended on the way the individual nourished self-esteem and self-confidence in coping with the change; was it seen as a challenge and a new way to improve his/her self-image, or as a loss? The complex psychological processes do not occur in a linear fashion, as perhaps suggested in previous transition literature (HOPSON & ADAMS, 1976). These movements can lead some dancers to adapt to new situations through a range of coping skills that are not always evident to the individual. Perceiving the threat to oneself (primary appraisal), assessing the resources available depending on the nature of the threat (secondary appraisal) and, as constant changes in the environment and in the developing coping responses occur, the permanent alert in which the individual resides, characterises how the stress is conceived (CARVER, SCHEIER & WEINTRAUB, 1989). [41]

The results highlighted that the sense of control plays a key role in the coping process of the dancer. The controllability of a stressor is the primary dimension in determining an appropriate match between stressors and types of support. CUTRONA and RUSSELL (1990) contend that a "controllable" event will require social components fostering problem focused coping, whereas "uncontrollable" events will require social support components that foster emotion focused coping. They also predicted that instrumental, tangible support will be more effective following uncontrollable events, whereas informational support through advice and guidance will be more effective following controllable events. The sense of control and choice the individual has over the situation also led to different coping strategies. Coping with a changing identity implies an adjustment both at psychological and social levels, but also an adjustment stemming from the social context. People around the dancer need to be aware of the changing person. As suggested by FOLKMAN et al. (1987), there is an adaptation which includes an emotional change (internal) and an alteration of the situation (external). When either of these two areas—external and internal—is not addressed, coping becomes more problematic. [42]

Coping includes processes that might be ill-fitted to the individual who is searching to resolve, but rather than being "wrong directions", as suggested by ALFERMANN, STAMBULOVA and ZEMAITYTE (2004), these processes become necessary parts of the journey. Rather than wrong paths, these are necessary steps that hopefully empower dancers to promote their individual development, experiences and reconstruction of the changing individual. Saving time or avoiding wrong directions means little in these journeys, as from each "step" the dancer can either learn or understand a new part of the "self"—indeed like a performance. Effective coping means as suggested by SCHLOSSBERG et al. (1995) utilising a range of strategies that fits any given and different situation. [43]

The study also highlighted that retirement from dance can be a source of identity crisis, when the dancer's identity is very pronounced. These findings support previous related sport literature (WERTHNER & ORLICK, 1986). The individual therefore strives for a reconstruction, a personal—within—and a social self—without—through an adjustment into alternative life styles and roles. The way people cope with changing life-events differs depending on:

how they perceive that change, either negative, challenging and/or positive,

the way they prepared for that change and the extent of their perceived sense of control and choice over the situation,

the saliency of their work-identity coping with the loss of an identity, the loss of a social structure and consequently the reconstruction and/or continuation of a new one. [44]

As the coping strategies are included in the personal journey of each individual, other developmental difficulties and changes in the life course of each individual took place as part of this personal journey. These other changes can include the acquisition of new roles (e.g. motherhood, parenthood), new assumptions and values (e.g. balance between private and public roles), and accommodation to new occupational roles (i.e. new jobs). The way people react to an event and respond to specific experiences will also determine how that same individual might be able to cope with other life-changes. There is not one way or one reason in which retirement coping processes can be explained, because the transition is complex and needs to be addressed within the context in which it takes place. Through time the individual can learn how to cope and manage future changes, through time the individual can learn to cope: coping within and without the self. [45]

Questions and sub-questions during interview schedule:

Can you start by telling me about yourself (e.g. your age, when did you start dancing, when did you stop)?

How did you feel when your career was coming to an end?

Was retirement planned? Was retirement sudden?

Do you want to share the reasons for your retirement?

How did you come to the decision of retiring?

Was it a lengthy process?

Was/is the experience important for you?

Do you want to share your feelings around the time of retirement?

Did/do you feel you have/had control of the situation?

Did/do you feel that you had enough support around you?

If you explore the events since retirement, which area has been more important?

Your friends? Your work? Your family? Yourself?

What kind of support you received if any? (friends, family, outside agency)

How did/do you feel towards your family?

How did they feel towards yourself?

How did/do you feel towards your colleagues that were still dancing?

How was the transition away from the Ballet Company?

How did you cope through the whole experience?

How did/do you cope with the transition?

How do you feel about the future?

Did/do you have a new purpose in life?

How is the future looking for you?

How do you define yourself now that you have "retired"?

Do you consider yourself still a dancer?

Do you see yourself as an individual looking for a new identity?

Are there any other experiences that you might want to share or address?

Looking retrospectively has the experience been important in a positive or negative way?

1) http://www.thedcd.org.uk <back>

2) http://www.bps.org.uk/downloadfile.cfm?file_uuid=6D0645CC-7E96-C67F-D75E2648E5580115&ext=pdf <back>

Alfermann, Dieter; Stambulova, Natalia & Zemaityte, Aiste (2004). Reactions to sport career termination: A cross-national comparison of German, Lithuanian and Russian athletes. Psychology of Sport & Exercise, 5, 61-75.

Blaikie, Andrew (1999). Ageing and popular culture. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Bridges, William (1980). Transitions: Making sense of life's changes. Reading, Mass: Addison-Wesley.

Carver, Charles; Scheier, Michael & Weintraub, Jason K. (1989). Assessing coping strategies: A theoretically based approach. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 56, 267-283.

Charner, Ivan & Schlossberg, Nancy K. (1986). Variations by theme: The life transitions of clerical workers. The Vocational Guidance Quarterly, 35, 212-224.

Coleman, Alan & Groombridge, Joy (1982). Preparation for retirement in England and Wales: A research report. Leicester: National Institute for Adult Education.

Corbin, Juliet & Strauss, Anselm (1990). Grounded theory method: Procedures, canons and evaluative criteria. Qualitative Sociology, 13, 3-21.

Cutrona, Carolyn E. (1990). Stress and social support: In search of optimal matching. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology, 9, 3-14.

Cutrona, Carolyn E. & Russell, Daniel W. (1990). Type of social support and specific stress: Toward a theory of optimal matching. In Irvin G. Sarason, Barbara R. Sarason, & Gregory R. Pierce (Eds.), Social support: An interactional view (pp.319-366), New York: Wiley.

Folkman, Susan; Lazarus, Richard S.; Pimley, Scott & Novacek, Jay (1987). Age differences in stress and coping processes. Psychology and Aging, 2, 171-184.

Heckhausen, Jutta & Schulz, Richard (1995). A Life-span theory control. Psychological Review, 102, 284-304.

Hopson, Barrie (1981). Response to the papers by Schlossberg. Counselling Psychologist, 9, 36-39.

Hopson, Barrie & Adams, John D. (1976). Towards an understanding of transition: Defining some boundaries of transition. In John Adams, John Hayes & Barrie Hopson (Eds.), Transitions: Understanding and managing personal change (pp.3-25). London: Martin Robertson.

Lazarus, Richard S. & Folkman, Susan (1984). Stress, appraisal and coping. New York: Springer.

Manheimer, Ronald J. (1994). The changing meaning of retirement. Creative Retirement, 1, 44-49.

Roncaglia, Irina (2006). Retirement as a career transition in ballet dancers, International Journal of Educational and Vocational Guidance, 6, 181-193.

Roncaglia, Irina (2008). The ballet dancing profession: A career transition model, Australian Journal of Career Development, 17(1), 50-59.

Savishinsky, Joel C. (1995). The unbearable lightness of retirement. Research on Ageing, 17, 243-259.

Schlossberg, Nancy K. (1981). A model for analysing human adaptation to transition. The Counselling Psychologist, 9, 2-18.

Schlossberg, Nancy K.; Waters, Elinor B. & Goodman, Jane (1995). Counselling adults in transitions: Linking practice with theory. New York: Springer.

Smith, Jonathan A. & Osborn, Mike (2003). Interpretative phenomenological Analysis. In Jonathan. A. Smith (Ed.), Qualitative psychology: A practical guide to research methods (pp.51-79). London: Sage.

Sugarman, Leonie (2001). Life-span development: Frameworks, accounts & strategies (2nd ed.). New York: Taylor & Francis.

Taylor, Jim & Ogilvie, Bruce (1994). A conceptual model of adaptation to retirement among athletes. Journal of Applied Sport Psychology, 6, 1-20.

Taylor, Shelley E. (2003). Health psychology. New York: McGraw-Hill.

van Gennep, Arnold (1960). The rites of passages (translated by M. Vizedom and G. Caffee). Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Werthner, Penny & Orlick, Terry (1986). Retirement experiences of successful Olympic athletes. International Journal of Sport Psychology, 17, 337-363.

Yardley, Lucy (2000). Dilemma in qualitative health research. Psychology and Health, 15, 215-228.

Irina RONCAGLIA is a Chartered Practitioner Psychologist at Sybil Elgar School (National Autistic Society), where she works with young adults with ASDs with challenging behaviour. She has published in the Australian Journal of Career Development, International Journal for Educational and Vocational Guidance, in the Qualitative Methods in Psychology Newsletter and presented papers at several conferences. RONCAGLIA has completed her PhD on the Retirement Transition in Ballet Dancers through a Life Course approach with the University of London, Birkbeck.

Contact:

Irina Roncaglia

The National Autistic Society

Sybil Elgar School

Havelock Rd. Southall UB2 4NR

London, UK

Tel.: +44 (0) 208 8139168

Fax: +44 (0) 208 7479886

E-mail: Irina@Roncaglia.co.uk

URL: http://www.roncaglia.co.uk/

Roncaglia, Irina (2010). Retirement Transition in Ballet Dancers: "Coping Within and Coping Without" [45 paragraphs]. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung / Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 11(2), Art. 1, http://nbn-resolving.de/urn:nbn:de:0114-fqs100210.