Volume 7, No. 3, Art. 4 – May 2006

Immigration and Citizenship: Participation and Self-organisation of Immigrants in the Veneto (North Italy)

Claudia Mantovan

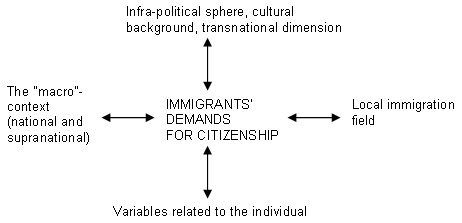

Abstract: The changes related to globalisation and to the increasing presence of immigrants in Western Europe place the traditional concept of citizenship in crisis: formal citizenship is no longer a means to inclusion for an increasing number of people, such as non-EU immigrants. A research project, like the one presented in this paper, which seeks to study immigrants' citizenship demands (MEZZADRA, 2001), needs, therefore, to concentrate on a more pragmatic meaning of citizenship. Partly following the suggestions of some authors who have researched this topic, I have built a multidimensional model for analysing immigrants' self-organisation and political participation in Italy and, in particular, in the Veneto region. The model takes into consideration four factors that can have an influence on immigrants' civic and political participation, namely: 1) supranational and national context, 2) local immigration field, 3) infra-political sphere, cultural background, transnational dimension and 4) some variables related to the individual (like gender, age, length of time in host country, etc). The findings show that these factors are important in shaping "immigrants' citizenship demands" and that for many immigrants formal citizenship is neither a salient issue nor a fundamental tool for participation in the society of arrival.

Key words: citizenship, immigrants, self-organisation, participation, Veneto, Italy

Table of Contents

1. Introduction

2. A Sociological Research Project to Study Immigrants' "Citizenship from the Ground"

3. The Influence of "Macro" Context and Local Immigration Field on Immigrants' Mobilisation and Participation

4. The Influence of Infra-political Sphere, Cultural Background, Transnational Dimension on Immigrants' Mobilisation and Participation

5. The Influence of Variables Related to the Individual on Immigrants' Mobilisation and Participation

6. Citizenship, Belonging and Participation

7. Conclusion

The research that informs this paper began as an interest in the changes facing western democracies, in particular the crisis of national citizenship that has paralleled the advancement of globalisation and the rise in migration across Europe. Citizenship, in fact, was born as a means to include, but in the last 30 years it has become more and more exclusive, because "economic globalisation creates a new kind of social exclusion, so that an important part of the population seems to have lost the connection with the sphere of citizenship" (DAHRENDORF, 1995, p.30). A very important question at stake now is, therefore, how to rethink a new model of citizenship adequate to this new era. [1]

Italian political scientist Sandro MEZZADRA suggests that "to get again to the essence of citizenship" it is necessary to analyse it not as a simple status but as an "action" (MEZZADRA, 2001, p.89). [2]

Citizenship has, in fact, different meanings. According to Rainer BAUBÖCK (1994), we can distinguish between a formal and a substantial one. The formal one is based on the link to the state, i.e. nationality; the substantial one is represented by a set of rights and duties accessed by this formal citizenship, i.e. rights to vote, respect of laws. [3]

Further, the substantial meaning of citizenship can be also used in two different ways: in a static meaning, as a simple possession of rights and duties, or in a dynamic meaning (what Gerard DELANTY, 2002 calls democratic citizenship), as an effective participation in political life. [4]

Arguing the importance of concentrating on this democratic citizenship, MEZZADRA suggests the value of researching what he calls the "immigrants' demands for citizenship". Immigrants, in fact, are at the same time victims, actors and "revealers" (due to the mirror function of immigration; SAYAD, 2002) of these changes, and to study immigrants is to gather insight into the contemporary crisis of national citizenship. [5]

MEZZADRA's idea, which seeks to analyse the issues involving citizenship and immigration from the point of view of immigrants' mobilisation, contains an intuition similar to that of NEVEU (1993), who sustains the value of an anthropological approach, referring to the contribution by ANDERSON (1983), and more in general, a micro-sociological approach to the issues of nationality and citizenship. [6]

2. A Sociological Research Project to Study Immigrants' "Citizenship from the Ground"

But what does it mean in concrete terms to study immigrants' citizenship demands from a sociological point of view? [7]

NEVEU helps us to move from the domain of political philosophy to those of sociology and anthropology by introducing the concept of what she calls "local citizenship" or "citizenship from the ground", that is "the multiple ways through which social actors themselves define, perceive, practice the engagement in a public space" (NEVEU, 1999, p.9). [8]

The "engagement in a public space" is close to the theme of the representation of interests. This last issue, in fact, has been the object of many studies related to the theme of citizenship. MARTINIELLO, for example, in his research on Italian immigrants in Belgium, chooses, among the many points of view from which to study integration, to adopt what VERBUNT (1976) defines as integration by means of autonomy, that is "the organisation of the immigrant communities and the role of ethnic institutions in the collective promotion of immigrants through negotiation with the institutions of the native society" (MARTINIELLO, 1992, p.38). [9]

Following these suggestions, I defined more precisely my research subject, that is how immigrants perceive themselves as citizens, how they bring their interests to bear in local society, what kinds of questions they ask in this context, how they interact with indigenous social networks, and how local policies influence this socio-political engagement. [10]

The research had four main objectives:

to obtain new data on the crisis of national citizenship and develop an analytical framework around this;

to link the crisis of national citizenship to the more grounded and localised participation of immigrants in the host society;

to review the host society's ability to manage the complexity that surrounds contemporary notions of citizenship and contemporary flows of migrants;

to examine the extent to which immigrants are a factor in "citizenship enlargement" through their (individual or collective) mobilisation. [11]

To set up my research's framework and methodology, I considered two other contributions, one coming from Pierre BOURDIEU and one from Hassan BOUSETTA. [12]

BOURDIEU (1994) argued the importance of adopting a relational approach, which means that we need to look at the relations among the social actors instead of the so-called substantial realities or essences such as individuals, groups, etc. [13]

BOUSETTA (2000) argued that to analyse ethnic politics and ethnic mobilisation we have to take into account three distinct analytical levels: the sphere of the state's political power, that of political organisation and that of infra-political activities. BOUSETTA explains the importance of these last two spheres arguing that the collective political action of immigrants may be analytically divided between political-organisational strategies and infra-political strategies. The former are addressed outside the group and intend to influence the political agenda; the latter are "invisible" forms of mobilisation, because they are addressed within the group itself, and aim to increase control and power over it. Sociology has often neglected the latter which, on the contrary, are essential to understanding the former. [14]

My research has been conducted in some provinces of the Veneto region (Treviso, Venice and Vicenza) and is constituted by four levels of analysis:

The "macro"-context (national and supranational), which can be considered as a political opportunity structure which influences immigrants' mobilisation.

Local immigration field: Analysis of what happens in the political-organisational sphere through the reconstruction of an ethnographic map of the key-actors, both Italians and immigrants, of what I defined as the local immigration field (adapting a famous concept by BOURDIEU1)), and a reconstruction of the development of their relationship. By key-figures I mean those who play an actual role in this field, above and beyond their institutional role. The Italians generally work for immigration assistance centres or in the immigration sector of labour unions, in local government, in the third sector. The immigrants are what I have named visible immigrants: mobilised immigrants (who mobilise themselves to represent a collective interest at different levels) who have also won the race for access into the public sphere and who therefore, in different roles and with different responsibilities, have become known at a local level and are often consulted by institutions or by the media. They have years of immigration experience behind them, and there are no more than ten of them in each of the provinces I have considered. To isolate these key-actors of the local immigration field I adopted a qualitative network analysis. My approach, based on in-depth interviews and observation through participation, with attention to the diachronic dimension, is closer to the network analysis by Anglo-Saxon social scientists from the Manchester school than to the characteristics this acquired after being exported to the US in the Seventies, when American structural analysts added a massive use of mathematical models, quantitative techniques and a particular attention to the influence of the grid on the social actor rather than vice-versa (see PISELLI, 1995).

Infra-political sphere, cultural background, transnational dimension: For the two nationalities considered by the stakeholders as "the most organised", the communities from Bangladesh and from Senegal, I also conducted a more detailed analysis of the forms of self-organisation which are not addressed to the host society. Immigrants I have considered in this part are mobilised but often not visible.

Variables related to the individual: I maintained constant attention on individual characteristics and strategies, because of a theoretical perspective which considers the relationship with their culture as something unique and mutable. [15]

My research framework is summarised in Fig.1:

Figure 1: The analytical research framework [16]

To investigate these topics, I used a mix between interviews and ethnography. In fact, I adopted a semi-structured interview with open-ended questions, but used as a very flexible instrument, so that I sometimes came back to re-interview the same person several times, when new questions emerged. This was possible thanks to the trust that I earned with the people after being in the field for several months. I also obtained a large amount of information from informal discussions. Total of interviewees (one or more times) was 65 (22 Italians and 43 immigrants). [17]

3. The Influence of "Macro" Context and Local Immigration Field on Immigrants' Mobilisation and Participation

The dynamics between mobilised immigrants and Italians in the study area confirm the results of a national research project (CARPO, CORTESE, DI PERI, & MAGRIN, 2003): the experiments (consultations, inter-ethnic organisations, etc.) set up in the late 1980s and early 1990s to deal with immigration have largely failed. In the Veneto areas, following an initial phase in which various organisations and unified inter-ethnic alliances were created (promoted by unions, often with the participation of Caritas2)), a new phase began. This new phase provided the context for the research and can be characterised by a fragmentation of immigrants into a thousand different streams based on ethnic, national, and/or religious association. These organisations are numerous but often only exist on paper. In these associations immigrants appear to be mainly occupied with mutual aid, intervening in their country of origin and promoting their own culture and practices; notable by their absence are the ethnic organisations with expressly political demands. [18]

Within the organisational context outlined above there are few visible immigrants taking an active communal roll. These are generally migrants who have lived in Italy for some years and this, combined with personal ability and/or a considerable cultural capital, has enabled them to become well-known figureheads. Their visibility comes mainly from the fact that they have managed to construct positive relationships with Italian actors in the local immigration field and thereby act as important intermediaries between minority and majority communities. However, they tend to do this pragmatically rather than through any "purpose-built" organisation. [19]

The question, then, is why, when all the immigrants interviewed were interested in voting at local elections and in participating politically, there was not any obvious immigrant activity for this purpose. [20]

There are many explanations. The inter-ethnic alliances set up by Italians in the 1980s and 1990s, such as the local immigration councils, show the limits of representational mechanisms arising from within the host society. Further, the role of immigrants within these groups was often marginal. This may be due to the fact that Italian society became multicultural relatively quickly and Italian officials sought an interlocutor to represent immigrants with equal alacrity. This was hastened by the fact that immigrants do not have the vote, and the forms of "representation" that resulted therefore addressed a need on the part of the host society and not the concerns/needs of immigrant minorities. In some cases representatives were "constructed" by official institutions. [21]

All of these elements explain why immigrants don't feel that the organisations set up by Italians are their own, and that they frequently complain about the fact that Italians have monopolised all of the central positions in the local immigration field. It is especially those immigrants who have been in Italy for the most time and who are most capable that complain about the fact that it is particularly difficult to make the "leap" from being considered assisted to being considered protagonists, liberating themselves from the stifling "tutelage" of the Italians. It is no accident, therefore, that in the two provinces where inter-ethnic alliances were set up (Treviso and Vicenza), various immigrants, in part the same who have participated in these experiments, have recently attempted (with greater or less success) to create their own real organisations, an attempt that, even if hardly systematic, has drawn the interest of many immigrants also in the province of Venice. [22]

The fact that this growing dissatisfaction on the part of immigrants leads to few and rarely effective reactions is also linked to their weak position in the host society, which has many causes, related to the supranational, national and local context:

Supranational context: globalisation, segmentation of the world labour force (COLATRELLA, 2001), closing of the borders by the EU.

Italian context: lack of political rights, policies of control that "produce" undocumented immigration, restrictive legislation on immigration and citizenship for those from outside the EU3), recent legislation on immigration which worsened the conditions for renewing the residency permit4). Other factors that work against the birth of strong immigrant political organisations relate to some characteristics of Italian immigration, namely the polycentric fragmentation5) and the fact that it is a rather recent phenomenon. The marginal position of immigrants in Italian society does not concern only material questions, but also symbolic ones. Immigrants are widely dissatisfied and frustrated with the image of the foreigner in Italy (who is seen, especially if undocumented, as a criminal). Further, there is a sense of not being a part of Italian society, inasmuch as those of a different race/religion are seen and treated by native Italians as "immigrants", even after living in Italy for many years. This gap between "immigrant" and "citizen" can be traced to what Catherine NEVEU (1993) calls nationité (nation-ness) and to what (with connotations different from those of NEVEU) Pierre BOURDIEU (1994) and Abdelmalek SAYAD (2002) call la pensée d'État. This involves a perception, unconsciously rooted in the minds of natives, that immigrants are ontologically "out of place" and they unsettle the ideal divisions that define nations as "natural"; such as language, culture, religion, traditions, race, etc. This helps to explain the profound resistance that immigrants encounter to their inclusion as "Italian citizens", and it is a resistance that is strong because it is based upon a taken-for-granted but constructed and imagined community that is invisible to many on the inside (SAYAD, 2002).

Local context: in Veneto immigrants complain of a lack of public spaces in which to meet6) and of intense work rhythms7) (immigrant interviewees complain in fact about a lack of time to put into organisations). These variables connected with the Veneto context lead to increasing the social exclusion of immigrants, and seem in part responsible for the pressure on the religious and cultural dimensions of their self-organisation. At the provincial and communal level, the influence of the regional context is then reinforced, or partially "corrected", by the adoption of diverse policies. The activity started by the city of Venice by its plan to concede the right to vote in local elections to immigrants in April 20058), for example, had as an effect the bringing to light of the sense of impotence that many immigrants had felt in the Veneto, liberating a desire for political participation that evidently, as one city worker put it, "already existed". [23]

Finally, the situation is further complicated by the divisions among Italian actors in the local immigration field, with competition between Italian actors to define a model for the integration of immigrants. The conflict is principally between a universalist and social democratic vision (predominant in cities like Venice), and a differentialist one (supported by the regional government and cities like Treviso), but the divisions are more stratified and capillary and are found within each single province and city, where here an anti-racist association and a city administration oppose each other, there, instead, a mayor and Caritas, etc. Cooperating with one rather than another Italian actor may impact upon the resources enjoyed by the immigrant or his/her relationship with other Italian immigrant actors. This competition can be a particular issue, especially when the immigrant has not been in Italy for long and/or does not have many other interlocutors9). [24]

Due to these factors of immigrants' weakness, it is not surprising that the few strategies based on social demands and also on head-on conflict come from those in positions of relative power and strength: those who are a bit "less immigrant" (that is, as a result of being an Italian citizen and/or resident in Italy for many years). [25]

4. The Influence of Infra-political Sphere, Cultural Background, Transnational Dimension on Immigrants' Mobilisation and Participation

Immigrants' associations and mobilisation seem to be partly influenced by the geographic area of origin. For example the immigrants coming from Sub-Saharan Africa are characterised by a high level of associationalism, while the associations among Eastern Europeans are usually small and little representative (with the partial exception of Albanians). [26]

Looking at the two cases studied, we can observe that Senegalese have often a strategy of presentation of self in which they tend to emphasise the democratic and political stability of their home country, its secularity, their internal unity, and the willingness of the Senegalese to respect the rules of the host country. As several of them said: "every Senegalese is an ambassador of Senegal". There is also a very strong work ethic amongst the Mourid Brotherhood10), a capacity for self-organisation that links to the tradition of African associationalism, and strong and widespread informal interaction or daa'ira (linked to the Brotherhood). These factors make the Senegalese the most organisationally vibrant; the community also has high union membership and is well connected to anti-racist associations. [27]

The Bangladeshis are highly internally organised, but show few signs of integration. This is especially noticeable in Venice, where there is a high concentration of Bangladeshi and where, along with national associations, there are also numerous groups linked to the political parties in their country of origin. Their associations (both national and political) appear to be characterised by a chronic factionalism, due to the reproduction of mechanisms present in the Bangladeshi social and political system. The social structure in Bangladesh is in fact based on the duality patron/client (EADE, 1989); this is a hierarchical social stratification, a legacy of the Hindu caste system, which gives rise to leaders who struggle for power not so much on the basis of political programs but as individuals. Bangladeshi activity, at least for now, appears primarily oriented within the group itself and towards Bangladesh. Examples of this activity include: celebrations on national holidays in which hundreds of people participate; daily news in Bengali on local radio stations (Venice); a sports arena to practice national sports (Treviso). Moreover, the principal concern of this group is that they need places to teach Bengali to their children. The question of language for Bangladeshi is crucial because it is a founding pillar of their nation and, therefore, key to maintaining collective identity. [28]

This level of analysis has confirmed the importance of the infra-political sphere and transnational dynamics in understanding migrant participation in the host society. The Bangladeshi political leaders11) and the Senegalese Marabouts12) are at the apex of this. [29]

5. The Influence of Variables Related to the Individual on Immigrants' Mobilisation and Participation

With reference to the conclusions in the previous paragraph, we must keep in mind, however, that in Italy we are dealing with first generation immigrants. Moreover, even amongst the first generation there are multiple division lines and the community continues to evolve. These division lines include: gender, length of time in host country, age, educational level, previous experience in politics, unions and associations, and class. [30]

These variables have considerable effects on immigrants' mobilisation and participation. In the case of gender this is particularly evident: immigrants' associations leaders are mostly men, due to the weak position of many women and to cultural factors that sometimes prevent women from engaging in the public sphere. Besides, immigrant women, when they reach a representative position, often show different needs compared to men. [31]

Regarding variables such as the length of time in host country and class, we have already given many elements in the third paragraph: if an immigrant has been living in Italy for a short period of time and has a hard and/or precarious job, he/she rarely has time to engage politically. [32]

Other relevant elements, partly linked to the first group, are the sense of belonging, plans, and in general the options that each one of them chooses to adopt in the society in which he/she has arrived. In this way, for example, it is interesting to note the difference between immigrants who generally prefer cooperation with inter-ethnic and Italian organisations and those who prefer to engage within their own national, ethnic and/or religious groups. [33]

6. Citizenship, Belonging and Participation

Italian citizenship does not seem to be a key concern for immigrants; what they want is simpler, namely, to be allowed complete freedom of movement, employment and residence. The denial/granting of any of these is arguably a more important criterion for social stratification in the era of globalisation than any concept of legal citizenship (BAUMAN, 1998). The "pragmatic" approach on the part of immigrants with regard to citizenship is linked to the fact that obtaining it does not eliminate the sense of exclusion from the host community (see above). Rather than obtaining formal status, immigrants desire the elimination of the material and symbolic obstacles that prevent their participation in the society in which they have arrived. [34]

The willingness of immigrants to participate in their host society is not considered by them to be in absolute contrast to the desire not to lose their own cultural roots. Their being "here" as well as "there" is, on the contrary, considered a dual resource enabling them to contribute to their country of origin, fulfil the role of cultural mediator, and integrate into their host country. The substantial indifference amongst immigrants with respect to the one-way "identity" option leads them to make explicit and mature criticism of what an immigrant interviewee defined as the "nationalised democracy" model of integration. [35]

This research shows that immigrants have multiple alliances and do not believe that formal citizenship is a key issue for them and a fundamental tool to participate in the society of arrival. [36]

Other factors, on the contrary, are revealed to be very important in influencing immigrants' self-organisation and participation:

The context of arrival and the position of immigrants within it. Immigrants claim that their weak position in the host society is one of the main obstacles in their political participation. In particular, the problems related to the residency permit and to the feeling of not belonging to the host society are respectively the biggest material and symbolic obstacle to their inclusion.

Infra-political sphere, cultural background, transnational dimension. The relevance of these factors, highlighted in the fourth paragraph, show that immigrants' citizenship demands are in some cases partly linked to the cultural background (i.e. the Bangladeshis' claim to have places where to teach Bengali to their children) and to the transnational dynamics (i.e. links of Senegalese with their Marabouts). The presence in European societies of increasing citizenship demands linked to different cultural backgrounds underlines that the traditional model of citizenship has become inadequate to deal with multiple identities of individual subjects.

Variables related to the individual. To be a man or a woman, to be part of a lower class or an upper class, newcomer or arrived in the host society several years since, together with more "subjective" variables such as previous experience in unions and political parties, sense of belonging, plans, etc, are also important factors in influencing immigrants' citizenship demands. Taking these factors into account prevents us adopting a deterministic image of the "culture", recognising on the contrary the many fractures inside the so called "ethnic communities", and highlights once more how "citizenship demands" are complex and internally differenced. [37]

What I have said so far allows me to respond to the questions I asked at the beginning of this research study, namely whether immigrants are revealers of the crisis of national citizenship configurations, and whether they are agents for "enlarging" citizenship. [38]

The answer to the first question is yes: from the "litmus test" constituted by the discourses and the activity of immigrants discussed earlier, it becomes clear that a "double crisis" exists, one that concerns the link between formal and substantial citizenship (that is the continuity between enjoyment of rights, above all political rights, and possession of a formal citizenship), and the other which concerns the link between formal citizenship and identity (that is, to continue to invest formal citizenship with connotations of identity). Italian society, therefore, does not seem to have yet elaborated effective tools for redefining the criteria for inclusion in a reality that has changed profoundly. [39]

So far as the second question is concerned, the response is, at least for now, mainly no. If the presence of immigrants is objectively increasing the complexity of society, and stimulating debate and interventions on the part of many Italian actors, this is not however the result of mobilisation on the part of immigrants because of the powerless conditions in which they find themselves, which prevents their "demand for citizenship" from translating itself into organisations that can impose themselves on the dominant society. [40]

Because, as we have seen, many factors in the marginalisation of immigrants originated at a supranational and national level, the local level (regional and sub-regional), while influential, can only have a partial impact in improving immigrants' existential situation and consequently their participation. [41]

The difficulties that immigrants report encountering in trying to participate in the society in which they have arrived, which include, as we have seen, serious "immaterial" problems (such as lack of access to the mediating and political "foundry" which shapes their social image), confirm the centrality of the category of exclusion in the contemporary era. If, in certain areas of the world, health, food and shelter are sufficient for full social integration, in post-industrial societies anyone seeking to fully take part in the life of the community also needs a degree of education, specific training, enjoyment of the modern means of communication, information, and collective recognition and appreciation of their own resources, needs and interests (DE FALCO, 2004). [42]

The exclusion of immigrants from participation in the exchange and social activity that define the condition of citizenship in a democratic society, as this study has shown, confirms the increasing inability of Western democracies to address the demands of a growing part of their own population. This also confirms that, due to the fact that formal citizenship is no longer a means of inclusion for many people, to research citizenship concentrating on its democratic meaning (that is, to concentrate on effective participation in social and political life and on the factors that can influence it) is a more fruitful methodology. [43]

I would like to thank Sam SCOTT, who edited all of the articles, reading them critically, and supervising the English translations; Maren BORKERT, who created this issue of FQS, organised the publication process, and worked on the formal aspects and translated the abstracts from English to German; Alberto MARTÍN-PÉREZ who translated the abstracts into Spanish.

1) Pierre BOURDIEU adopted the concept of "field" to analyse the structure and the power relations within the same domain (scientific, bureaucratic, etc). The "local immigration field" is rather a transversal field, which includes individuals belonging to different "fields" understood in the strict sense used by BOURDIEU, namely the Italian and immigrant people who deal with immigration in different roles and with different interests, in the territories that I have analysed. <back>

2) A Catholic organisation. <back>

3) The Law 91 of 1992 doubles the period required for non-EU immigrants to be able to request naturalisation, from five to ten years. <back>

4) The Law 189 of 2002 (called the "Bossi-Fini" Law) introduced the "contratto di soggiorno" ("visiting contract"), linking the residency permit with the work contract. <back>

5) The immigrants in Italy come from 191 countries, and those in Veneto, from 173 (CARITAS, 2003). <back>

6) The territory of Veneto, as a result of widespread industry, is overwhelmed by a rampant urbanisation. <back>

7) The majority of immigrants interviewee were, in fact, workers. <back>

8) An initiative which did not end well. <back>

9) In Venice, for example, there is an anti-racist organisation which has a bad relationship with some Venetian civil servants, due to political differences. Immigrants who attend the meetings of this organisation often are newcomers and don't speak Italian, so they easily absorb from the anti-racist network this bad opinion regarding Venice council. <back>

10) A Sufi Brotherhood which has been created in Senegal at the end of the XIX century. <back>

11) The political leaders of Bangladesh name the leaders of Bangladeshi political groups in Rome, who in turn choose the head of the political groups in other Italian cities. <back>

12) The Marabouts (spiritual guides) visit their talibe (disciples) in the countries of emigration as well. <back>

References

Anderson, Benedict (1983). Imagined communities. Reflections on the origin and spread of nationalism. London: Verso.

Bauböck, Rainer (1994). Transnational citizenship: membership and rights in international migration. Aldershot: Edgar Elgar.

Bauman, Zygmunt (1998). Globalisation. The human consequences. Cambridge: Polity Press-Blackwell Publishers Ltd.

Bourdieu, Pierre (1994). Raisons pratiques. Paris: Éditions du Seuil.

Bousetta, Hassan (2000). Institutional theories of immigrant ethnic mobilisation: relevance and limitations. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, 26(2), 229-245.

Calabrò, Anna Rita (1997). L'ambivalenza come risorsa. La prospettiva sociologica. Bari: Laterza

Caritas (2003). Immigrazione. Dossier Statistico. Roma: Anterem.

Carpo, Federico; Cortese, Ornella; Di Peri, Rosita & Magrin, Gabriele (2003). Immigrati e partecipazione politica. Il caso italiano. Available at: http://www.retericerca.it/Satchel/documents/Rapporto%20finale%20Italia.pdf [Accessed: 16th January 2006].

Colatrella, Steven (2001). Workers of the world. African and Asian migrants in Italy in the 1990's. New York-Asmara: Africa World Press.

Dahrendorf, Ralph (1995). Quadrare il cerchio. Benessere economico, coesione sociale e libertà politica. Bari: Laterza.

De Falco, Michela (2004). Marginal citizenship. Paper presented in the Summer School EFMS, Helsinki, 22-31 August.

Delanty, Gerard (2000). Citizenship in a global age. Society, culture, politics. Buckingham: Open University Press.

Eade, John (1989). The politics of community: the Bangladeshi community in East London. Aldershot: Avebury.

Martiniello, Marco (1992). Leadership et pouvoir dans les communautés d'origine immigrée. Paris: CIEMI-L'Harmattan.

Mezzadra, Sandro (2001). Diritto di fuga. Migrazioni, cittadinanza, globalizzazione. Verona: Ombrecorte.

Neveu, Catherine (1993). Communauté, nationalité et citoyenneté. De l'autre coté du miroir: les Bangladeshis de Londres. Paris: Karthala.

Neveu, Catherine (Ed.) (1999). Espace public et engagement politique. Enjeux et logiques de la citoyenneté locale. Paris: L'Harmattan.

Piselli, Fortunata (Ed.) (1995). Reti. L'analisi di network nelle scienze sociali. Roma: Edizione I Centauri.

Sayad, Abdelmalek (2002). La doppia assenza: dalle illusioni dell'emigrato alle sofferenze dell'immigrato. Milano: Raffaello Cortina Editore.

Verbunt, Gilles (1976), Travailleurs immigrés: grève des foyers. Projet, 109, 981-985.

Wihtol de Wenden, Catherine (2001). La beurgeoisie. Les trois âges de la vie associative issue de l'immigration. Paris: CNRS Éditions.

Claudia MANTOVAN has a Ph.D. in sociology and is a research fellow in the Sociology Department at Padua University. Her research areas include: migration, citizenship, participation and territoriality.

Contact:

Claudia Mantovan

Dipartimento di Sociologia, Università di Padova

via Cesarotti, 10/12, 35123, Padova, Italy

Tel.: 049/827.4364

Fax: 049/827.4335

E-mail: claudia.mantovan@libero.it

URL: http://www.sociologia.unipd.it/

Mantovan, Claudia (2006). Immigration and Citizenship: Participation and Self-organisation of Immigrants in the Veneto (North Italy) [43 paragraphs]. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung / Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 7(3), Art. 4, http://nbn-resolving.de/urn:nbn:de:0114-fqs060347.