Volume 11, No. 1, Art. 2 – January 2010

Context, Experience, Expectation, and Action—Towards an Empirically Grounded, General Model for Analyzing Biographical Uncertainty

Herwig Reiter

Abstract: The article proposes a general, empirically grounded model for analyzing biographical uncertainty. The model is based on findings from a qualitative-explorative study of transforming meanings of unemployment among young people in post-Soviet Lithuania. In a first step, the particular features of the uncertainty puzzle in post-communist youth transitions are briefly discussed. A historical event like the collapse of state socialism in Europe, similar to the recent financial and economic crisis, is a generator of uncertainty par excellence: it undermines the foundations of societies and the taken-for-grantedness of related expectations. Against this background, the case of a young woman and how she responds to the novel threat of unemployment in the transition to the world of work is introduced. Her uncertainty management in the specific time perspective of certainty production is then conceptually rephrased by distinguishing three types or levels of biographical uncertainty: knowledge, outcome, and recognition uncertainty. Biographical uncertainty, it is argued, is empirically observable through the analysis of acting and projecting at the biographical level. The final part synthesizes the empirical findings and the conceptual discussion into a stratification model of biographical uncertainty as a general tool for the biographical analysis of uncertainty phenomena.

Key words: biographical uncertainty; youth transitions; post-communism; time perspective; unemployment; recognition; social change; economic crisis

Table of Contents

1. Introduction—Dangerous Transitions

2. The Case of Magdalena

3. Dimensions and Time Perspectives of Biographical Uncertainty

4. A Stratification Model of Biographical Uncertainty for Empirical Analysis

5. Concluding Remarks

1. Introduction—Dangerous Transitions

In this article I want to suggest a general, empirically grounded model for analyzing biographical uncertainty. It was developed on the basis of empirical work done in the course of a study of meanings of work and unemployment among young people in transitions to working life in the context of post-communist Lithuania (REITER, 2008a). If one accepts the corrosion of the validity of (normality) expectations as one of the main reasons for uncertainty on the biographical level (WOHLRAB-SAHR, 1993; ZINN, 2004; BONSS & ZINN, 2005), then the post-communist transformation, similar to the recent economic crisis, qualifies as a generator of biographical uncertainty par excellence. Within the formerly communist half of Europe the continuity promises of the life course model of the authoritarian welfare state and its criteria for evaluating individual performance (LEISERING & LEIBFRIED, 1999; LEISERING, 2003) disappeared over night together with the many restrictions it had imposed on individual lives. In other words, the post-communist situation became an exogenous source of uncertainty because it re-defined institutions and resulted in the dissolution of what had been taken for granted (BONSS, 1995, p.23). [1]

For young people growing up in these countries of rapid societal mainstreaming along Western standards of economy and society the new situation implied that uncertainty was introduced into their transitions to the world of work on at least three levels that are analytically distinguished in the literature (e.g. BONSS & ZINN. 2005, p.186): First, on the level of structural uncertainty unemployment, introduced together with market economy and capitalism, changed the institutional context of transitions to working life. The routes to employment were diversified and institutional guidelines lost their binding character. Second, the constitution of biographical expectations suffered from the devaluation of traditional models of normality of life and employment. Transition decisions were individualized, perspectives confused and de-standardized. Third, uncertainty was perceived by individuals as a new feature of the post-communist environment and reacted upon by individuals. While this third dimension partly transcends the sociological argumentation, the higher level of societal uncertainty is expressed in rather straightforward indicators like the suicide rate, which increased among young people in some of the former communist countries during the 1990s (UNICEF 2000, Chapter 2). [2]

Several contributions discuss some of the effects of this and similar forms of "external uncertainty" relevant to post-communist youth transitions (e.g. ROBERTS, CLARK, FAGAN & THOLEN, 2000; KOVACHEVA, 2001; WILLIAMS, CHUPROV & ZUBOK, 2003; BLOSSFELD, KLIJZING, MILLS & KURZ, 2005; and NUGIN, 2008).1) This article wants to add to this knowledge a perspective that reveals the translation of external threats, real or imagined, to how they may become relevant at the inside of (biographical) action. In short, a general model for analyzing biographical uncertainty is introduced taking the example of youth transitions. [3]

Transitions are (extended) moments of biographical change where individuals within certain biographical, social and material situations establish expectations on the basis of their experiences and other forms of knowledge available to them. The here discussed issue of youth transitions to the world of work and the related problem of unemployment is such a moment of change, as is the transition to adulthood in general, or that of other agents in other stages in the life course. Transitions typically involve normative as well as biographical aspects. In normative terms, and following the original work of Arnold VAN GENNEP (1981), transitions constitute "status passages" between life course positions. Status passages "link institutions and actors by defining time tables and entry as well as exit markers for transitions between social status configurations," as HEINZ (1996, pp.58-59) puts it. Conceptually, status passages are at the intersection of agency/structure and represent the biographical actor and his or her biography as well as the life course and related institutions and their normative program in general. [4]

The biographical dimension of transitions is further underlined by their quality as "fateful moments" that GIDDENS (1991, p.243) defines as "moments at which consequential decisions have to be taken or courses of action initiated." The biographical quality of transitions consists here in conceptualizing the individual as an actor that is, in principle, able to manipulate the shape of his or her trajectory from birth to death. While this enterprise may be insignificant within the flow of societal, global, or even cosmic events, it is critical for the constitution of a biography as an ontogenetic narrative. A transition is not one fateful moment but, qua extended moment of oriented change, a succession or conglomerate of fateful moments where single decisions or events may have far-reaching consequences and may even be "out of control."2) [5]

Transitions, like all human actions, are characterized by an inherent uncertainty concerning outcome and consequences for the future of both individual and society. Mary DOUGLAS (1996) uses the notion of "danger" to capture this two-fold aspect of insecurity in transitions. Following VAN GENNEP, DOUGLAS points to the significance of "danger-beliefs" for the maintenance of the "ideal order of society" in religious systems. She identifies passages through transitional states and marginal periods as dangerous for the individual and as potentially contagious or dangerous for others:

"He (i.e. VAN GENNEP; H.R.) saw society as a house with rooms and corridors in which passage from one to another is dangerous. Danger lies in transitional states, simply because transition is neither one state nor the next, it is undefinable. The person who must pass from one to another is himself in danger and emanates danger to others" (DOUGLAS, 1996, p.97). [6]

Unemployment in welfare market societies as a possible outcome of youth transitions to working life (i.e. the "next room" in the corridor of life after schooling, in the metaphor) is an example for the two-fold danger in the above sense, i.e. it is dangerous for both individual and society. While it is an integral element and a threat to the very arrangement of such societies, the option of unemployment also firmly establishes a reference problem around which individual lives need to be organized. After all, unemployment triggers the establishment of (external) moral claims as part of "men's attempts to force one another into good citizenship" (DOUGLAS, 1996, p.3). [7]

The abolishment of the constitutional obligation (and right) to labor in former state socialist countries ended the ideological claims to comprehensive labor planning together with the "communist taboo against unemployment" (BAXANDALL, 2000). With mass unemployment, also the post-education job guarantee once characterizing socialism was now burdened with uncertainty, "a situation in which actors cannot predict outcomes and cannot assign probability distributions to possible outcomes," as BECKERT (1996, p.814) defines it for the purpose of economic sociology. In other words, the institutionalization of unemployment together with the labor market in former state socialist countries turned youth transitions in post-communism into dangerous transitions in the sense of DOUGLAS.3) The threats of unemployment to biography and identity that JAHODA, LAZARSFELD and ZEISEL (1975) had described many years ago as well as novel employment-based criteria of "right/good" or just "appropriate/tolerable" behavior (JUSKA & POZZUTO, 2004) became relevant also to young people growing up in countries with a past of several decades of communist rule. [8]

Against this background, the model of biographical uncertainty introduced in this article is constituted on the basis of an analysis of interviews with young people in transition to the world of work in the post-Soviet and neo-capitalist context of Lithuania. Lithuania was chosen as a context because it is one of the countries that, after the collapse of the Soviet Union entered a transformation, which involved their mainstreaming towards a Western model of economy and society and finally brought them into the European Union. The Lithuanian transformation was among the most radical and resulted, among other things, in an extensive working poor problem (BARDONE & GUIO, 2005) as well as mass unemployment. With an overall unemployment rate of 16.5% in 2001 the Lithuanian youth unemployment rate reached its peak of close to 31% in the same year; at that time it was the highest among the Baltic countries (EUROPEAN COMMISSION, 2006). While unemployment had declined in the course of the study due to labor shortage in the region, this trend was sharply reversed during the ongoing economic crisis. Within the 14 months from May 2008 to July 2009, the overall unemployment rate nearly quadrupled from 4.4% to 16.4%.4) [9]

Altogether 30 problem-centered interviews (WITZEL, 2000) with young people were conducted in the year 2004 in the frame of a qualitative research project exploring the new meanings of work and unemployment from the perspective of young people in transition to working life. The sample includes young people in linear (n=11) and in non-linear (n=19) transitions to working life. Half of the respondents are male, half female; half of them live in the capital Vilnius, eight in other towns or regional centers, and seven in villages. They are between 15 to 24 years old; the core age-range is 16 to 21 years with single cases below and above. The interviews were conducted by Lithuanian native-speakers and translated into English. Due to the unavoidable "foreignization" of the originally spoken language associated with this processing and manipulating of the data (TEMPLE & YOUNG, 2004), certain forms of hermeneutic in-depth analysis were ruled out (see e.g. FLICK, 2006, pp.330-341). However, the data analysis involved, on the one hand, extensive biographical case reconstructions. On the other hand, on the basis of cross-case analyses empirically grounded typologies following the suggestions of KLUGE (2000) were systematically constructed. Altogether three such classifications were produced. The first is a heuristic typology of relations between individuals, the state, and the unemployed in society. A second typology classifies young women in the sample according to their gender-work relations. The third classification, which is relevant here, deals with patterns of youth transitions and related time perspectives of biographical uncertainty.5) [10]

In order to reproduce the practical steps towards the empirically grounded model of biographical uncertainty the argument is organized into three steps. The following part introduces the case of a young woman and how she responds to the threat of unemployment in the transition to the world of work. As prototypical example of the youth transition pattern of continuation, this case is characterized by comprehensive reduction of uncertainty. Thereafter, her uncertainty management in the time perspective of certainty production is conceptually rephrased by distinguishing three types or levels of biographical uncertainty: knowledge, outcome, and recognition uncertainty. All three are differently represented in patterns of youth transitions and their corresponding time perspectives of biographical uncertainty; and they are empirically observable through the analysis of acting and projecting at the biographical level. The final part synthesizes the discussion into a stratification model of biographical uncertainty as a general tool for the biographical analysis of uncertainty phenomena. [11]

In the postscript written after the conversation with Magdalena, the interviewer uses the following words to summarize her impression of the respondent:

"The most important thing about the girl (that I noticed) is that she is calm about her future. She already knows what she wants to be in her life, what she wants to achieve, and how to achieve this. As she said herself: 'I already found my place'." [12]

Magdalena is an 18-year-old student in the first year at the Faculty of Police. Her transition from lower to upper secondary education and into her first year of studies went smoothly, and it seems she had little doubts about what she wanted to study. First, she thought of trying to enter military academy and then decided to become police officer, like her father. It is a profession that she already liked as a child, as she says now. She even manages to indicate that she first articulated this idea towards some relatives in her childhood at the age of four. Asked about her motivation, she answers:

"Somehow actually I thought about it since childhood, because my father (is) also at the police. So I remember when I was four years old, and when we used to go to the village, so relatives used to ask me: 'What are you going to be when you grow up?' 'A police officer, like dad' (...)" (21.9).6) [13]

Although Magdalena had some other professional ideas and even considered attending university she gave it up as she was not confident enough regarding her capacity in view of her poor educational performance. Police work, on the other hand, could be chosen within the Lithuanian system of applying for post-secondary education with the "lowest marks" (21.9), as she points out. Importantly, now that she studies in the first year at the Faculty of Police the influence of her father, retired by now, is omnipresent and the identification with his experiences is high. He became her general model of future work. The continuation of the "family tradition" (21.45) of police work is a major motivating element in Magdalena's narrative. Over and over again, she repeats that she wants to please her family, make it "proud" of her, and to prove that their initial skepticism concerning her performance at school was unnecessary. She made an effort, studied hard and was more successful than expected. Asked whether she felt any kind of pressure or wanted to do the same as her father, she once more refers to her childhood and says that she wishes her children to perpetuate this circle of intergenerational recognition:

"No, nothing. I just, maybe, well, when I was a child, I used to look at my father, in uniform and so, and I used to think ... Well, I was proud that my father was in the police force. And I also want my children to be proud that I would be as well, not only something simple, but I will hold a (responsible) position (...)" (21.46). [14]

In order to study, Magdalena had to leave the place where she grew up and move to another town, where she now lives in a student dormitory. Her high identification with what she studies extends to her new social environment—"I'm telling you I feel that it is my place" (21.14). On the other hand, the relationship to her friends from the past, which she meets occasionally back home on weekends, changed considerably. She even says that she "got alienated from these friends because they stayed the same" (21.15). She changed her life style and feels that she has nothing in common with them anymore. Gradually loosing interest is only one dimension of this process of dissociation. The distinction is finally quite explicit. While her friends in regular studies at university will be able to continue with an easy students' life for a while, Magdalena has a rather clear perspective ahead; working life, her "future," is just around the corner. She comments the difference between her friends and herself like this:

"Well, they don't think yet. Because my future is very close. Because it is only one and a half years for me and that's it, I go to work. I'll have to work for a year. And I know that I have to study hard for a year, for a year and a half. Well, I have to get a good job. And then I should get good recommendations to study further. And this point is very close. Maybe it seems for them that, well, four years, so, 'We'll have time to get used to it, it is nothing' " (21.16). [15]

Magdalena's general idea of life is pretty consolidated—i.e. growing up, education, perhaps going abroad to see a different life for a while, and then essentially working for a year or two in order to get established, and having family. Going abroad is what she needs to sacrifice and postpone for the time being; the contract she decided to sign in order to benefit from the job guarantee associated with her professional education requires her to stay in the country after finishing it. She does feel a bit uneasy about being involved in a very strict program of education, but the price she has to pay is small in view of the continuity advantages she expects to have and compared to the transitional discontinuity she observes among relatives, friends and former classmates. Compared to some of her former classmates that are now studying, or compared to other acquaintances that started drifting and use drugs, she is lucky to benefit from the job security attached to her professional track. Others will have to face the tough reality of the labor market where contacts, friends and money are the most important preconditions of admission, as she maintains. The certainty of getting a job is "a very big point in favor of this profession" and has already been promised by contracts. In a situation of unpredictability, she can be "calm" already now; and she emphasizes the fact that she is in the comfortable position of being able to say: "I will have a job" (21.27). [16]

Although she believes that it should be possible to find some job in case one wants to, Magdalena recognizes the actual lack of work places as a major reason for unemployment apart from individual shortcomings that may be relevant for not getting a job. She also criticizes the fact that many young people end up in tracks of higher education without job prospects. She suggests that there should be ways of channeling them also into non-academic jobs—"people should be told what their real perspectives are" (21.33). She chose the field of work where her father's social capital can be useful for her—"I even went for that, because dad will help me somehow through old connections. Because I don't know, I wanted these kinds of guarantees." Otherwise she probably "would go abroad, to do any kind of work" (21.42). In this respect "it was much more difficult for our parents. They did everything by themselves, and now parents can help us somehow. Well, at least my family" (21.34). In the Soviet Union people usually had to go to work right after school and it was more difficult to continue in education. For those who managed to study, it was clear already before they had finished where they would work, as she says:

"As I was told, they also studied and maybe in the third year, when two years were left for them, so they used to have jobs, they already knew that they would finish and would go to work there, to some factory or something" (21.34). [17]

Magdalena's perspective of continuation with regard to working life is extraordinarily consistent. In her account she emphasizes this conscious choice of continuity-guarantees, which she establishes on different levels. She maintains the family tradition and experience of appreciating and "executing" a certain activity across the societal transformation; and she intends to pass this "family spirit" of police work on to the next generation. Additionally, her choice seems to allow the facilitating influence of her father's position to unfold and last into her own career. In this way, she obviously, consciously or not, benefits from advantages of the old and new system. Through her choice, she finally also escapes the expectable difficulties in the current labor market, and she maintains the predictability-advantages of the former system in terms of clear structures and perspectives with regard to both work as such and career. [18]

In the following, I want to rephrase the specificities of this case in conceptual terms in order to develop and unfold the terminology used to conceptualize the general model of biographical uncertainty. For reasons of space and clarity, and in order not to lose the focus of the article, I restrict myself to only one case here. In the underlying study, conceptual paraphrases were produced for prototypes of all three youth transition patterns of the typology (REITER, 2008a, 2007).7) [19]

3. Dimensions and Time Perspectives of Biographical Uncertainty

Magdalena is not far away from already having made an important decision about her (professional) future. The interview gives her the opportunity to look back upon this decision and locate it in relation to her past and her anticipated future as well as to her (social) environment. "Biographical rationalization" could be a general term to describe this process of ex post, and depending on the present situation, establishing a meaningful order within the space of biographical experiences.8) In her case, this rationalization produces the image of a young woman who knows what she wants and how; who is confident things will turn out like planned; and who has plans that are both totally in accordance with her family's tradition and socially highly acceptable. In conceptual terms, Magdalena's time perspective is one of certainty production. In her case the specific "linkage of the past and future of the life story in the present," as BROSE, WOHLRAB-SAHR and CORSTEN (1993, p.170) define the concept of time perspective, relates experience (past) productively to expectations (future) and biographical projecting (present). [20]

Experience and its status in biographical projecting is the key category for an assessment of the quality of the linkage of past, present and future. Experiences are characterized by a dual temporal horizon: through experience we conserve and reinterpret the past in order to orient our (biographical) action towards the future (FISCHER & KOHLI, 1987; VOGES, 1987; HOERNING, 1989; HOERNING & ALHEIT, 1995; ROBERTS, 2004). Following WOHLRAB-SAHR (1992, 1993), a sociological notion of biographical uncertainty is generally identified as the weakening of this linkage of experience, expectation and projecting due to an erosion of intersubjectively shared certainty in a specific social situation. Processes of deinstitutionalization, like the post-communist transformation, can be among the reasons for this kind of uncertainty.9) [21]

Like all her peers, Magdalena is affected by the biographical uncertainty challenge that affects youth in post-communism: institutional arrangements of youth transitions, together with the knowledge about their interplay, eroded or became redundant. On the basis of the interview material, altogether three levels or dimensions of biographical uncertainty can be distinguished. Uncertainty of knowledge refers to biographical planning and the mobilization of experience knowledge in the sense of SCHÜTZ and LUCKMANN (1973). Uncertainty of outcome of (social) action concerns anticipated events and results in view of the essential contingency of the future (MEAD, 2002). Uncertainty of recognition characterizes the re-evaluation of the social environment addressing the issue of recognition within social relations (HONNETH, 1992). [22]

How are these dimensions of biographical uncertainty represented in Magdalena's case? [23]

First, Magdalena solves the Schützian problem of knowledge uncertainty related to the advent of unemployment to the post-communist world by pursuing an unproblematic career on the basis of knowledge available within the family. The transformations of post-communist societies towards market democracies are "imposed transitions" that question the validity of available knowledge and patterns of biographical orientation. The question is: to what should one aspire, and how under the changing conditions? The typical reaction to this situation of "knowledge crisis" (SCHÜTZ, 1964) would consist in the application, adjustment and updating of available knowledge and experience—however useful it may be—by reflecting on one's own experience or that of significant others. In short, in Magdalena's case the reference to a stock of past experiences predominates her motivational basis for future-oriented acting. She essentially eliminates knowledge uncertainty by projecting the past of her family into her own future (and, possibly, that of her offspring).10) [24]

Second, the rather high predictability of what shape Magdalena's future will take according to her choices strongly reduces the universally valid Meadian problem of outcome uncertainty. Outcome uncertainty has become part of post-communist youth transitions to the world of work simply because unemployment was introduced in the course of the transformation of institutional arrangements. For better or worse, the post-communist transformation is a shift towards a kind of complexity that additionally challenges individual action. Probably more than before, the actual outcome of biographical action now depends on the extent to which shares of the future can be appropriated through the right assessment of chances, the anticipation of changes in opportunity structures, and, finally, the ability to consolidate one's own priorities in the present situation. The review and revision of what may become useful from the past for the future in an attitude of control focuses the attention to the present as the "locus of reality" (MEAD, 2002/1932); it provides the chance to reduce some of the contingencies of life. By adopting an apparently low-risk professional career that is feasible also for a young woman in a high-risk labor market, Magdalena narrows down her horizon of relevance as well as the range of expectable outcomes. Also her potential for spontaneity, contingency rooted in MEAD's concept of the "I," is reduced in this way. [25]

Third, the societal transformation changed the status of individuals and potentially requires a reorganization of the space of relevant social contacts and what they represent. The problem of recognition uncertainty is precisely rooted in this re-assessment of social contacts through and for changing societal requirements. It refers to "struggles for recognition" in the sense of HONNETH (1992) as they happen on the biographical level when actors establish their biographical orientations under consideration of and active reference to significant "circles of recognition" (PIZZORNO, 1991, p.219).11) Anthropologically, relational uncertainty and the process of reorganizing social affiliation are part of the natural, social, and reflexive human condition of uncertainty (DUX, 1982). Young people have a generally higher sensitivity with regard to the significance of certain others. Issues of status vis-à-vis others are particularly critical in moments of transition, which, as discussed in the introduction, are normatively charged. The process of post-communist transformation may further facilitate recognition uncertainty by, on the one hand, questioning and devaluating the competence of older significant others to inform the future of their offspring. On the other hand, as the overall logic of "normative modeling" of the life course (LEISERING, 2003, p.211-214) changes, the social environment itself needs to distribute positions anew considering the novel criterion of achievement with unemployment as its indicator of failure (REITER, 2007). Magdalena's particular strategy of recognition uncertainty management by sorting out her social past consists in a combination of two aspects: the dissociation from "old friends" and peers; and the utilization of the positive family capital by continuing with the family tradition that is, above all, socially highly recognized. [26]

Altogether, Magdalena's account is an example of comprehensive neutralization of uncertainty and production of certainty on all three levels. Knowledge uncertainty is reduced through the production of predictability by extending the past (i.e. family experiences). Contingency and outcome uncertainty is avoided through the adoption of an apparently low-risk professional career in a high-risk labor market. Recognition uncertainty, finally, is eliminated and social esteem constructed through family tradition and the related narrative of intergenerational recognition. This extensive production of certainty at this moment in time does not necessarily imply that Magdalena's (professional) future will be deprived of any moment of creativity, change, or contingency. On the contrary, modern (professional) socialization across the life course usually involves the fluctuation of competing priorities like those of professional continuity versus self-actualization (HELLING, 1996). [27]

The case of Magdalena is representative of the youth transition pattern of continuation; it is one of three patterns identified in the underlying interview material. The other two are the pattern of liberation and the pattern of trajectory. They can be summarized and generalized in the following way (without providing additional empirical reference for the latter two).

The pattern of continuation is characterized by a configuration of experience, expectation and projecting, which results in a time perspective of comprehensive production of certainty. Outcome-, knowledge-, and recognition-uncertainty are neutralized by mobilizing resources and knowledge available within the family. Once interests and aims in life are consolidated, the focused reproduction of familiar normality brings the future largely "under control." Contingency is replaced with possibility within the logic of the chosen career. Uncertainties with regard to the world of work as well as the possibility of unemployment are associated with life outside this track. The involvement of young people in traditionally acknowledged forms of activity, or "meaningful tradition" involving a sustainable biographical project, results in a unity of forms of emotional recognition (family) and social recognition (employment security), at times at the cost of sacrificing some of the freedom of the new system.

The pattern of liberation is characterized by a time perspective of contingency production and reproduction. Outcome-, knowledge-, and recognition-uncertainty are high but not necessarily "problematic" because positively exploited as creativity and self-actualization. The future is kept open and "out of sight"; fatalism underlines this attitude. A certain mode of operation, a lifestyle, is consolidated rather than interests and priorities. The rejection of the typical is part of the reaction to dropping out (sometimes on purpose) of the usual program of socialization. Uncertainties with regard to the world of work concern the quality of activities rather than unemployment as such. This pattern goes hand in hand with estrangement from social background and high internalized standards of (unconventional) achievement, which allow the clear distinction of oneself from others, peers or members of society in general. The newly available opportunity structure of the westernized system is appreciated as a challenge that needs to be faced. However, the strong moment of (possible) external determination in a space of social contingency, potential intolerance towards others, and a marginalized group that is too slow to cope with the rapid change are the price of such liberation.

The pattern of trajectory12) is characterized by an apparently idiosyncratic mode of uncertainty management and by a time perspective of restoration and normalization of a life burdened with extensive external determination partly due to social and family situations. Outcome-, knowledge-, and recognition uncertainty are dealt with in an ambivalent way; the latter due to multiple experiences of misrecognition—especially those most painful on the primary emotional level. Achievement logic is reduced to the immediate environment following a pragmatic and closed process of stabilizing one's situation and relationships. Opportunities beyond the present are conventional or confused; or they reflect tracks that have already been interrupted, indicating that the interruption has never really been acknowledged. The lack of resources as well as unemployment in the family constrains possibilities and constitutes uncertainty with regard to the world of work. The latter is seen as a real threat that is answered with gendered strategies of coping as well as involvement in rather destructive and in this sense "meaningless tradition" with no sustainable biographical project. [28]

All three patterns of youth transitions and the associated time perspectives are responses to the uncertainty problematic of the post-communist situation. They are instructive for a general model of biographical uncertainty for analyzing similar phenomena, which is suggested in the following part. [29]

4. A Stratification Model of Biographical Uncertainty for Empirical Analysis

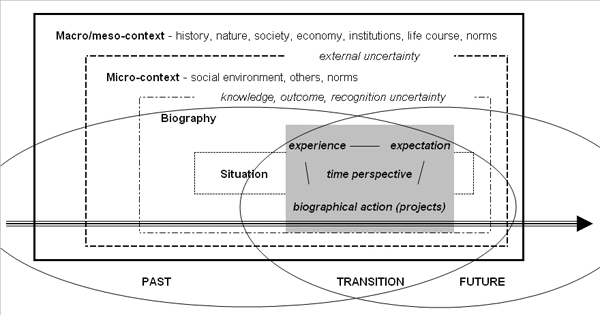

Taken together, the elements discussed in the course of the paper can be synthesized into a dynamic stratification model for the analysis of biographical uncertainty (Figure 1). It should be understood as a map for the analysis of uncertainty rather than a theoretical model. In short, the observable core of biographical uncertainty consists of the negotiation of biographical action and projection by meaningfully linking experience (PAST) to expectations (FUTURE)—i.e. the establishment of a biographical time perspective—within a changeable biographical situation (TRANSITION). Analytically, biographical uncertainties and the time perspectives that characterize them accommodate three dimensions:

The uncertainty of knowledge refers to the consultation of the available stock of knowledge for clues to establish productive biographical expectations and a project into the future (i.e. the past in the present and the future). This level involves the analysis of the motivational orientation of biographical planning.13)

The uncertainty of outcome refers first of all to the concern about the (near) future and to the re-valuation of the present and its capacity to administer some control over shares of this future on the basis of a re-interpretation of the past (i.e. the present in the past and the future). Here, the analysis focuses on the extent to which the future can be brought under the "control" of the present situation.

The embeddedness of transitions within the micro-context of the social environment establishes recognition uncertainty as a third, relational layer of biographical uncertainty. Biographically relevant action is here understood as social action in the sense of Max WEBER, and as a way of establishing and defining relations to significant others. It is oriented towards a social environment monitoring biographical action on the basis of recognized criteria for normatively acceptable performance; these include criteria of (social) citizenship and achievement in the life course (i.e. others as past, present, and future). [30]

Norms like these usually transcend the immediate environment and refer to the historically changeable meso- and macro-context within which biographies typically evolve mediated by the life course as a socially and politically constructed, institutionalized frame of reference and generator of sets of expectations towards life (LEISERING, 2003). Finally, changes in the wider context of institutions, society, economy, nature, and history may be sources of external uncertainty. The significance of this wider context is contingent upon the extent to which the individual is tied to it by mediating frameworks like, for instance, the life course or the political economy of a society.

Figure 1: A dynamic stratification model of biographical uncertainty [31]

In other words, the investigation of biographical time perspectives as triangular configurations of experience, expectation and projecting is at the center of a systematic analysis of biographical uncertainty in youth transitions as well as other decisive biographical moments and status passages. They all are embedded within stratified environments of experience. The analysis of these triangular configurations through the reconstruction of how motives of biographical action, as well as action itself, establish a linkage between past and future in the biographical situation allows the empirical localization and assessment of knowledge, outcome and recognition uncertainty at the inside of biographical action. These uncertainties are situational and, thus, dynamic and changeable over time. The social environment is implicated at all levels of uncertainty as source of knowledge, motivation and proxy experience, and as imagined target audience of outcome that is relevant in terms of both evaluation and relationship management. Finally, the possible impact of changes in the economy and the society, and especially in the politically socialized institution of the life course can be reconstructed in this perspective. In this way, we can find out whether, how, and to what extent external uncertainties that may be recognized in theoretical and empirical terms actually enter the level of biographical acting. [32]

For instance, on the basis of this model it should be possible to find out whether and how globalization-related "increasing insecurity, which is becoming the basic experience of the younger generation," as BECK and BECK-GERNSHEIM (2009, p.33) maintain following BLOSSFELD et al. (2005), is in fact articulated and ratified on the level of biographical action. Similarly, evidence for the biographical relevance of the economic, cultural and social context features of an "acceleration society" that ROSA (2003, 2005) describes can be brought forward empirically. [33]

The identification of the boundaries of this outer layer of the onion of uncertainty is particularly difficult. For instance, despite their obvious relevance, the anthropological foundations of social life usually constitute only unexpected sources of external uncertainty. Occasionally, events like earthquakes are able to suspend the "habitual ties between the body and the world" (REHORICK, 1986, p.388) and bring to mind the fundamental context-dependence of mankind. Also the fact that we inhabit the thin shell of a fireball racing through space with some 100,000 km/h typically does not result in a biographically relevant "cosmic anxiety," at least not among people usually considered sane.14) Even the risks of physical destruction through wars and other forms of dying "by human decision," both quite omni-present and probable within a lifetime (HOBSBAWM, 1994, p.12; LEITENBERG, 2006), are filtered out or suppressed by (protective) cognitive mechanisms. All these aspects may be culturally, religiously or politically moderated, manipulated or neutralized;15) or they simply do not become relevant within the stock of experiences as frames or schemata that are typically available within the circulation and transmission of relevant knowledge among a few generations. [34]

Altogether, the empirical analysis of the relevance of external sources of insecurity and risk, which may be identified in both theoretical and empirical terms, for biographical uncertainty needs to follow the perspective of individual actors. [35]

In this article I suggest to move the discussion around uncertainties in youth transitions and other biographical moments of change one step further by introducing a general model for the analysis of biographical uncertainty. The model is empirically grounded in a comparative investigation of patterns of youth transitions to the world of work in the post-communist context of Lithuania, a context where the problem of unemployment was introduced together with the market-based management of human resources. The area of youth transitions is where the model may have its primary relevance as a tool also for the synthesis of available classifications of youth transitions to work and adulthood with a similar interest like, for instance, CAVALLI (1985), BRANNEN and NILSEN (2002), DU BOIS-REYMOND (1998), and LECCARDI (2005).16) [36]

Furthermore, the model developed against this very specific background can be compared to typologies constructed in other contexts. WOHLRAB-SAHR's (1993) classification of seven types of biographical uncertainty empirically reconstructed on the basis of a study of female temporary work, or ZINN's (2004) typology of biographical certainty construction are but two examples. This is not the place for such a necessarily more extensive enterprise; yet, a crucial difference to these two examples consists in the fact that the stratification model of biographical uncertainty introduced here is empirically grounded in a study that does not need to refer to sociological meta-discourses in order to frame the investigation. The post-communist transformation, it seems, is a phenomenon that is largely independent of meta-narratives of a gradual evolution of modernity towards another level like that of reflexive modernization. Uncertainty is here not due to creeping change but due to an abrupt confrontation of whole societies with new requirements of organizing life. Common notions like that of "shock therapy" (GLIGOROV, 1995) used to describe the dynamic of the socio-economic transformation are indicative of this type of change. [37]

The current economic crisis is another turning point in history that undermines established continuity beliefs. The threat of unemployment is once again at the center of the problem that is, this time, a global one and not confined to post-communism.17) However, for the population of the former socialist east of Europe it is the second time within two decades that the very foundations of their societies are challenged. Follow-up research could, for instance, prepare to study the "Children of the Great Recession" and how this historically unique global phenomenon impacted on both their uncertainty profiles and their coping and development in the years and decades to come (see ELDER, 1974; ZERNIKE, 2009). [38]

Finally, the model presented here incorporates features that seem sufficiently general to perhaps contribute one aspect and building block to a sociology of uncertainty that, it seems, still needs to be written. Single aspects have been discussed more systematically, all in a certain perspective of interest (e.g. KAUFMANN, 1970; EVERS & NOWOTNY, 1987; BONSS, 1995; BECKERT, 1996; BOGNER, 2005; ZINN, 2008). Yet a comprehensive review is missing that would consider the classical sociological contributions including those of DURKHEIM and MERTON, SIMMEL and PARK, as well as those of GEHLEN, DOUGLAS and other institutional anthropologists. [39]

Earlier versions of the argument synthesized in this paper were presented on three occasions: at the 8th Annual Conference of the European Sociological Association "Conflict, Citizenship and Civil Society," Glasgow, 3-6 September, 2007, Joint session of Research Network 3 (Biographical Perspectives on European Society) and Research Network 22 (Sociology of Risk and Uncertainty); at the 1st ISA Forum of Sociology "The End of Rationality? The Challenge of New Risks and Uncertainties in the 21st Century," Barcelona, 5-8 September 2008, Joint session of TG04 and RC38: "Biographical Coping with Risk and Uncertainty" of the International Sociological Association (ISA); and at the Nordic Youth Research Conference NYRIS10 "Bonds and Communities—Young People and Their Social Ties," Lillehammer, 13-15 June 2008. I want to thank the participants of these sessions for valuable comments and feedback.

1) Uncertainty and risk are popular issues in youth research in general. More recent examples include: CAVALLI (1985), GILLIS (1993), FURLONG and CARTMEL (1997a, b), HEINZ (2009), KELLY (1998), CIESLIK and POLLOCK (2002), LECCARDI (2005, 2008). <back>

2) THOMSON et al. (2002) study related phenomena for young people under the heading of "critical moments." <back>

3) See also ALLATT (1997). <back>

4) Source: EUROSTAT, EUROIND Database, Harmonized unemployment rates (%), monthly data, http://epp.eurostat.ec.europa.eu/portal/page/portal/euroindicators/labour_market/database [Retrieved in September 2009]. <back>

5) For the discussion of prototypical examples of these typologies see REITER (2008b, 2009, 2010). <back>

6) The first part of the number (i.e. 21) refers to the number of the interview; the second part (i.e. 9) refers to the consecutive unit of coding. <back>

7) There, also the more extensive localization of uncertainty in relevant social theories of time of G. H. MEAD and Alfred SCHÜTZ is discussed. See also REITER (2003). <back>

8) The notion of biographical rationalization suggested here has nothing to do with that put forward by BOLÍVAR and DOMINGO (2006) for the purpose of discussing the establishment of the biographical approach within the scientific community. <back>

9) It is important to note that it is the planning of action on the basis of such a linkage, rather than the realization of whatever outcome of action, that is at the core of biographical uncertainty. <back>

10) Especially regarding the reduction of uncertainty through knowledge reproduction this pattern of continuation shares some commonalities with Jens ZINN's (2004) type of "traditionalization" as a mode of certainty construction. <back>

11) I have elaborated on this elsewhere in the frame of discussing the ambivalent role of family ties in post-communism (REITER, 2008c). I suggest to use the term of recognition uncertainty when significant social relations, their history, constitution, and prospects, become a source of ambiguity in the process of establishing biographical transition expectations, plans and projects. These ambiguities can hamper, undermine, or trigger and facilitate self-development and self-confidence and invite forms of recognition uncertainty management; they determine the assessment of available options and shape future-oriented action. <back>

12) The label of "trajectory" as it is used here refers to the concept first developed by STRAUSS and GLASER (1970) in the context of studies of dying trajectories. See also RIEMANN and SCHÜTZE (1991). <back>

13) The micro-epistemological problem addressed here is a biographical correlate of a fundamental knowledge problem in modernity, e.g. DUX (2005, p.119): "Under conditions of uncertainty human beings need to make knowledge certain, i.e. provable. But uncertainty of knowledge is the stigma of the modern age." <back>

14) However, about a century ago, SPENGLER's (1963, p.215) notion of "Weltangst" addressed related issues. See NAGEL, SCHIPPER and WEYMANN (2008) for a discussion of the contemporary relevance of apocalyptic ideas. <back>

15) For an ethnographic example of the importance of ignorance and its social production in view of ground contamination see AUYERO and SWISTUN (2008). <back>

16) However, as indicated in REITER (2009) the here introduced terminology and dimensions of uncertainty may well be useful also for the description of responses of nations (like the post-socialist ones) to uncertainty in transitions. <back>

17) Robert B. ZOELLICK, president of The World Bank Group, and Dominique STRAUSS-KAHN, managing director of the International Monetary Fund, express the development rather unambiguously in their joint foreword to the Global Monitoring Report 2009 (IBRD & THE WORLD BANK, 2009, p.xi): "We are in the midst of a global financial crisis for which there has been no equal in over 70 years. It is a dangerous time. The financial crisis that grew into an economic crisis is now becoming an unemployment crisis. It risks becoming a human and social crisis—with political implications. No region is immune." For estimations of the global scope of the job crisis see also IMF, 2009; and ILO, 2009). <back>

Allatt, Pat (1997). Conceptualising youth: Transitions, risk and the public and the private. In John Bynner, Lynne Chisholm & Andy Furlong (Eds.), Youth, citizenship and social change in a European context (pp.89-102). Aldershot: Ashgate.

Auyero, Javier & Swistun, Debora (2008). The social production of toxic uncertainty. American Sociological Review, 73, 357-379.

Bardone, Laura, & Guio, Anne-Catherine (2005). In-work poverty. New commonly agreed indicators at the EU level. Population and living conditions. Statistics in focus. Population and social conditions 5/2005. European Commission, Eurostat, http://ec.europa.eu/employment_social/social_inclusion/docs/statistics5-2005_en.pdf [Date of access: January 30, 2009].

Baxandall, Phineas (2000). The communist taboo against unemployment: Ideology, soft-budget constraints, or the politics of de-stalinization? East European Politics and Societies, 14, 597-635.

Beck, Ulrich & Beck-Gernsheim, Elisabeth (2009). Global generations and the trap of methodological nationalism. For a cosmopolitan turn in the sociology of youth and generation. European Sociological Review, 25, 25-36.

Beckert, Jens (1996). What is sociological about economic sociology? Uncertainty and the embeddedness of economic action. Theory and Society, 25(80), 3-840.

Blossfeld, Hans-Peter; Klijzing, Erik; Mills, Melinda & Kurz, Karin (Eds.) (2005). Globalization, uncertainty and youth in society. London: Routledge.

Bogner, Alexander (2005). Grenzpolitik der Experten. Vom Umgang mit Ungewissheit und Nichtwissen in pränataler Diagnostik und Beratung. Weilerswist: Velbrück Wissenschaft.

Bolívar, Antonio & Domingo, Jesús (2006). Biographical-narrative research in Iberoamerica: Areas of development and the current situation. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung / Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 7(4), Art. 12, http://nbn-resolving.de/urn:nbn:de:0114-fqs0604125 [Date of access: April 23, 2009].

Bonss, Wolfgang (1995). Vom Risiko. Unsicherheit und Ungewissheit in der Moderne. Hamburg: Hamburger Edition.

Bonss, Wolfgang & Zinn, Jens O. (2005). Erwartbarkeit, Glück und Vertrauen – Zum Wandel biographischer Sicherheitskonstruktionen in der Moderne. Soziale Welt, 56(2/3), 183-202.

Brannen, Julia & Nilsen, Ann (2002). Young people's time perspectives: From youth to adulthood. Sociology, 36, 513-537.

Brose, Hanns-Georg; Wohlrab-Sahr, Monika & Corsten, Michael (1993). Soziale Zeit und Biographie. Über die Gestaltung von Alltagszeit und Lebenszeit. Opladen: Westdeutscher Verlag.

Cavalli, Alessandro (1985). Il tempo dei giovani. Bologna: Il Mulino.

Cieslik, Mark & Pollock, Gary (2002). Young people in risk society: The restructuring of youth identities and transitions in late modernity. Aldershot: Ashgate.

Douglas, Mary (1996). Purity and danger: An analysis of the concepts of pollution and taboo. London: Routledge.

Du Bois-Reymond, Manuela (1998). "I don't want to commit myself yet": Young people's life concepts. Journal of Youth Studies, 1, 63-79.

Dux, Günter (1982). Die Logik der Weltbilder. Sinnstrukturen im Wandel der Geschichte. Frankfurt/Main: Suhrkamp.

Dux, Günter (2005). Toward a sociology of cognition. In Nico Stehr & Volker Meja (Eds.), Society & knowledge. Contemporary perpectives in the sociology of knowledge & science (pp.117-150). New Brunswick: Transaction.

Elder, Glen H. (1974). Children of the great depression. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press.

European Commission (2006). Employment in Europe 2006. Luxembourg: Office for Official Publications of the European Communities.

Evers, Adalbert & Nowotny, Helga ( 1987). Über den Umgang mit Unsicherheit – die Entdeckung der Gestaltbarkeit von Gesellschaft. Frankfurt/Main: Suhrkamp.

Fischer, Wolfram & Kohli, Martin (1987). Biographieforschung. In Wolfgang Voges (Ed.), Methoden der Biographie- und Lebenslaufforschung (pp.25-49). Opladen: Leske und Budrich.

Flick, Uwe (2006). An introduction to qualitative research (3rd edition). London: Sage.

Furlong, Andy & Cartmel, Fred (1997a). Risk and uncertainty in the youth transition. Young—Nordic Journal of Youth Research, 5(1), 3-20.

Furlong, Andy & Cartmel, Fred (1997b). Young people and social change. Individualization and risk in late modernity. Buckingham: Open University Press.

Giddens, Anthony (1991). Modernity and self-identity. Self and society in the late modern age. Cambridge: Polity.

Gillis, John R. (1993). Vanishing youth: the uncertain place of the young in a global age. Young—Nordic Journal of Youth Research, 1(1), 3-17.

Gligorov, Vladimir (1995). Gradual shock therapy. East European Politics and Society, 9, 195-206.

Heinz, Walter R. (1996). Status passages as micro-macro linkages in life course research. In Ansgar Weymann & Walter R. Heinz (Eds.), Society and biography. Interrelations between social structure and the life course (pp.51-65). Weinheim: Deutscher Studienverlag.

Heinz, Walter R. (2009). Youth transitions in an age of uncertainty. In Andy Furlong (Ed.), Handbook of youth and young adulthood. New perspectives and agendas (pp.3-13). London: Routledge.

Helling, Vera (1996). Bausteine berufsbiographischer Sozialisation. BIOS – Zeitschrift für Biographieforschung und Oral History, 9, 74-92.

Hobsbawm, Eric J. (1994). Age of extremes: The short twentieth century, 1914-1991. London: Viking Penguin.

Hoerning, Erika M. (1989). Erfahrungen als biographische Ressourcen. In Peter Alheit & Erika M. Hoerning (Eds.), Biographisches Wissen (pp.148-163). Frankfurt/Main: Campus.

Hoerning, Erika M. & Alheit, Peter (1995). Biographical socialization. Current Sociology, 43, 101-114.

Honneth, Axel (1992). Kampf um Anerkennung. Zur moralischen Grammatik sozialer Konflikte. Frankfurt/Main: Suhrkamp.

IBRD and The World Bank (2009). Global monitoring report 2009. A development emergency. Washington: The International Bank for Reconstruction and Development & The World Bank, http://siteresources.worldbank.org/INTGLOMONREP2009/Resources/5924349-1239742507025/GMR09_book.pdf [Date of access: April 29, 2009].

ILO (2009). Global employment trends: January 2009. Geneva: International Labour Office, http://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/---dgreports/---dcomm/documents/publication/wcms_101461.pdf [Date of access: April 17, 2009].

IMF (2009). World economic outlook: Crisis and recovery. Washington: International Monetary Fund, http://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/weo/2009/01/pdf/text.pdf [Date of access: April 23, 2009].

Jahoda, Marie; Lazarsfeld, Paul F. & Zeisel, Hans (1975). Die Arbeitslosen von Marienthal. Ein soziographischer Versuch über die Wirkungen langandauernder Arbeitslosigkeit. Mit einem Anhang zur Geschichte der Soziographie. Frankfurt/Main: Suhrkamp.

Juska, Arunas & Pozzuto, Richard (2004). Work-based welfare as a ritual: Understanding marginalisation in post-independence Lithuania. Journal of Sociology and Social Welfare, 31, 3-24.

Kaufmann, Franz-Xaver (1970). Sicherheit als soziologisches und sozialpolitisches Problem. Stuttgart: Ferdinand Enke Verlag.

Kelly, Peter (1998). Risk and the regulation of youth(ful) identities in an age of manufactured uncertainty. PhD thesis, Deakin University, Melbourne.

Kluge, Susann (2000). Empirically grounded construction of types and typologies in qualitative social research. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung / Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 1(1), Art. 14, http://nbn-resolving.de/urn:nbn:de:0114-fqs0001145 [Date of access: June 1, 2003].

Kovacheva, Siyka (2001). Flexibilisation of youth transitions in Central and Eastern Europe. Young—Nordic Journal of Youth Research, 9(1), 41-60.

Leccardi, Carmen (2005). Facing uncertainty. Temporality and biographies in the new century. Young—Nordic Journal of Youth Research, 13(2),123-146.

Leccardi, Carmen (2008). New biographies in the "risk society"? About future and planning. Twenty-First Century Society, 3(2), 119-129.

Leisering, Lutz (2003). Government and the life course. In Jeylan T. Mortimer & Michael J. Shanahan (Eds.), Handbook of the life course (pp.205-225). New York: Kluwer.

Leisering, Lutz & Leibfried, Stephan (1999). Time and poverty in western welfare states. United Germany in perspective. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Leitenberg, Milton (2006). Deaths in wars and conflicts in the 20th century. Cornell University Peace Studies Program, Occassional Paper #29 (3rd ed), http://www.cissm.umd.edu/papers/files/deathswarsconflictsjune52006.pdf [Date of access: April 25, 2009].

Mead, George H. (2002). The philosophy of the present. Amherst: Prometheus Books.

Nagel, Alexander K.; Schipper, Bernd U. & Weymann, Ansgar (Eds.) (2008). Apokalypse. Zur Soziologie und Geschichte religiöser Krisenrhetorik. Frankfurt/Main: Campus.

Nugin, Raili (2008). Constructing adulthood in a world of uncertainties: Some cases of post-Communist Estonia. Young—Nordic Journal of Youth Research, 16(2), 185-207.

Pizzorno, Alessandro (1991). On the individualistic theory of social order. In Pierre Bourdieu & James S. Coleman (Eds.), Social theory for a changing society (pp.209-233). Boulder: Westview Press.

Rehorick, David Allan (1986). Shaking the foundations of lifeworld: A phenomenological account of an earthquake experience. Human Studies, 9, 379-391.

Reiter, Herwig (2003). Past, present, future. Biographical time structuring of disadvantaged young people. Young—Nordic Journal of Youth Research, 11(3), 253-279.

Reiter, Herwig (2007). Biographical uncertainty in the transition to working life among young people in post-Soviet Lithuania. Paper presented at the 8th Annual Conference of the European Sociological Association "Conflict, citizenship and civil society," Glasgow.

Reiter, Herwig (2008a). Dangerous transitions in the "New West"—youth, work, and unemployment in post-Soviet Lithuania. PhD-thesis, European University Institute, Florence.

Reiter, Herwig (2008b). "I would be against that, if my husband says: 'You don't work.'"—Negotiating work and motherhood in post-state socialism. Sociological Problems, IL, 193-211.

Reiter, Herwig (2008c). Recognition uncertainty and the role of family ties in negotiating post-communist youth transitions. Paper presented at the Nordic Youth Research Conference NYRIS10 "Bonds and communities—young people and their social ties," Lillehammer.

Reiter, Herwig (2009). The uncertainty of liberation in the "New West". Journal of International Relations and Development, 12(4), 395-402.

Reiter, Herwig (2010). Die nachholende Generation? Anmerkungen zur Beschleunigung der Generationslagerung Jugendlicher im Neuen Westen Europas. In Michael Busch, Jan Jeskow & Rüdiger Stutz (Eds.), Zwischen Prekarisierung und Protest. Die Lebenslagen und Generationsbilder von Jugendlichen in Ost und West (pp.329-350). Bielefeld: transcript Verlag.

Riemann, Gerhard & Schütze, Fritz (1991). "Trajectory" as a basic theoretical concept for analyzing suffering and disorderly social processes. In David Maines (Ed.), Social organization and social process (pp.333-357). New York: Aldine de Gruyter.

Roberts, Brian (2004). Health narratives, time perspectives and self-images. Social Theory & Health, 2, 170-183.

Roberts, Kenneth; Clark, Stanley C.; Fagan, Colette & Tholen, Jochen (2000). Surviving post-communism. Young people in the former Soviet Union. Celtenham: Edward Elgar.

Rosa, Hartmut (2003). Social acceleration: Ethical and political consequences of a desynchronized highspeed society. Constellations, 10(1), 3-33.

Rosa, Hartmut (2005). Beschleunigung. Die Veränderung der Zeitstrukturen in der Moderne. Frankfurt/Main: Suhrkamp.

Schütz, Alfred (1964). The stranger. An essay in social psychology. In Alfred Schütz (Ed.), Collected papers II (pp.91-105). The Hague: Martinus Nijhoff.

Schütz, Alfred & Thomas Luckmann (1973). The structures of the life-world. Evanston: Northwestern University Press.

Spengler, Oswald (1963). Der Untergang des Abendlandes. Umrisse einer Morphologie der Weltgeschichte. München: Beck.

Strauss, Anselm & Glaser, Barney (1970). Anguish. The case history of a dying trajectory. Mill Valley: The Sociology Press.

Temple, Bogusia, & Young, Alys (2004). Qualitative research and translation dilemmas. Qualitative Research, 4, 161-178.

Thomson, Rachel; Bell, Robert; Holland, Janet; Henderson, Sheila; McGrellis, Sheena & Sharpe, Sue (2002). Critical moments: Choice, chance and opportunity in young people's narratives of transition. Sociology, 36, 335-354.

UNICEF (2000). Young people in changing societies. Regional monitoring reports, No. 7. Florence: UNICEF Innocenti Research Centre.

Van Gennep, Arnold (1981). Les rites de passage. Étude systématique des rites. Paris: A. et J. Picard.

Voges, Wolfgang (1987). Zur Zeitdimension in der Biographieforschung. In Wolfgang Voges (Ed.), Methoden der Biographie- und Lebenslaufforschung (pp.125-141). Opladen: Leske und Budrich.

Williams, Christopher; Chuprov, Vladimir & Zubok, Julia (2003). Youth, risk and Russian modernity. Aldershot: Ashgate.

Witzel, Andreas (2000). The problem-centered interview [26 paragraphs]. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung / Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 1(1), Art. 22, http://nbn-resolving.de/urn:nbn:de:0114-fqs0001228 [Date of access: May 31, 2003].

Wohlrab-Sahr, Monika (1992). Über den Umgang mit biographischer Unsicherheit – Implikationen der "Modernisierung der Moderne". Soziale Welt, 43, 217-236.

Wohlrab-Sahr, Monika (1993). Biographische Unsicherheit. Formen weiblicher Identität in der "reflexiven Moderne": Das Beispiel der ZeitarbeiterInnen. Opladen: Leske und Budrich.

Zernike, Kate (2009). Generation OMG. The New York Times, http://www.nytimes.com/2009/03/08/weekinreview/08zernike.html [Date of access: March 13, 2009].

Zinn, Jens O. (2004). Health, risk and uncertainty in the life course: A typology of biographical certainty construction. Social Theory & Health, 2, 199-221.

Zinn, Jens O. (Ed.) (2008). Social theories of risk and uncertainty. An introduction. Oxford: Blackwell.

Herwig REITER is Research Fellow at the Chair of Political Sociology and Comparative Analysis of Contemporary Societies at the University of Bremen. His main areas of interest include the sociology of youth, work and unemployment, life course and biography, post-communism, and qualitative methodology and methods.

Contact:

Herwig Reiter

University of Bremen

Institute of Sociology

Bremen, Germany

Tel.: 0049 (0)421-218-66403

Fax: 0049 (0)421-218-66353

E-mail: hreiter@bigsss.uni-bremen.de

URL: http://www.smau.gsss.uni-bremen.de/index.php?id=reiter

Reiter, Herwig (2010). Context, Experience, Expectation, and Action—Towards an Empirically Grounded, General Model for Analyzing Biographical Uncertainty [39 paragraphs]. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung / Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 11(1), Art. 2, http://nbn-resolving.de/urn:nbn:de:0114-fqs100120.