Volume 11, No. 1, Art. 5 – January 2010

The Spatial Dimension of Risk: Young People's Perceptions of the Risks and Uncertainties of Growing Up in Rural East Germany

Nadine Schäfer

Abstract: Young people have been identified as one of the groups most severely affected by post-socialist transformation processes (McAULEY, 1995; BRAKE & BÜCHNER, 1996; KOLLMORGEN, 2003). They are growing up at a time that is characterized by the need for reorientation due to the collapse of state socialism and its far-reaching economic, political and cultural consequences (YOUNG & LIGHT, 2001). Young people in post-socialist countries are thus often described as facing additional risks and uncertainties to create their own biographies (BRAKE & BÜCHNER, 1996; WERZ, 2001).

This paper discusses the spatial dimension of young people's perception and experiences of risks. It argues that young people's perception of space has a major impact on how they perceive their opportunities to cope with, challenge and/or negotiate experiences of risks and uncertainties. It will be shown that such perceptions have major implications on, for example, their migration and career plans.

The paper will draw on new research findings from an in-depth participatory research study of young people growing up in rural East Germany (SCHÄFER, 2008). The project has focused on young people's perception of everyday disadvantages and risks, and how they translate such experiences and understandings into their (imagined) future lives. I argue here that young people's understanding of risk is interlinked with their perception of space. This spatial dimension of risk, however, has largely been neglected in previous research.

Key words: young people; rural; post-socialist; space; risk; Germany; second modernity

Table of Contents

1. Introduction

2. The Meaning of Risk for Young People's Everyday Lives

3. The Meaning of Risk in a Rural, Post-Socialist Context

4. Background to the Research Project

5. Young People's Perception of the Disadvantages and Risks of Growing up in Rural East Germany

6. Negotiating Risk: Who Benefits and Who Struggles?

7. Making Sense of Perceptions and Experiences of Everyday Risks

8. Conclusion

Social scientists have labeled young people in post-socialist Germany as the "losers" of reunification (see BRAKE & BÜCHNER, 1996; KOLLMORGEN, 2003) due to the rapid changes and new forms of socio-economic inequalities which are connected with the transition process. While high out-migration and unemployment rates and the lack of job and training opportunities are characteristic for most rural regions in western countries, academics have pointed out that East-German rural regions are particularly disadvantaged (BAUR & BURRMANN, 2000; BRAKE, 1996; BRAKE & BÜCHNER, 1996; KOLLMORGEN, 2003). This refers back to the fact that rural life in the socialist German Democratic Republic (GDR) was mainly organized by the state through agricultural co-operatives (Landwirtschaftliche Produktionsgenossenschaften) which also took over the responsibility for a wide range of social and administrative functions in rural areas (see RUDOLPH, 1997; VAN HOVEN, 2001). After reunification, however, these service structures were dissolved without being replaced. [1]

Comparative research on East and West German youth further indicates that young East Germans are more likely to perceive their future as bleak, and are much more pessimistic about their future prospects than their western counterparts as they have experienced more dramatic changes (see BRAKE, 1996; BRAKE & BÜCHNER, 1996; WERZ, 2001; FÖRSTER, 2003). In line with this, findings from the Shell youth studies (DEUTSCHE SHELL, 2002, 2006) refer to an increasing gap between East and West German youths with regard to their perception of their personal options. In this paper I focus on young people's perceptions of their everyday lives in rural East Germany more than 15 years after unification of the two German parts. I will analyze how these young people perceive and experience their everyday lives, and the choices and risks they are facing. The chapter will show how young people's understanding of everyday and future risks are shaped by their perception of spatial differences which has major implications on their understanding of how to prepare themselves for their future lives. This spatial dimension of risk, however, has all too often been overlooked even though it might provide a valuable contribution in creating a better understanding of the heterogeneity of young people's everyday lives in second modernity (BECK, 2002). [2]

2. The Meaning of Risk for Young People's Everyday Lives

BECK's (2000, 2002), BECK and BECK-GERNSHEIM's (2002) and GIDDENS' (1990, 1991, 1994, 2000) theoretical work on individualization and the development of a second modernity has become an important reference for youth research and youth studies in sociology and geography, both in the German and Anglo-American context (EVANS, BEHRENS & KALUZA, 1999; GRIFFIN, 2001; DEUTSCHE SHELL, 2002; ZINNECKER, BEHNKE, MASCHKE & STECHER, 2002; BURDEWICK, 2003; VALENTINE, 2003; JENTSCH, 2004; JENTSCH & SHUCKSMITH, 2004; DEUTSCHE SHELL, 2006; FRANCE, 2007; FURLONG & CARTMEL, 2007; ROCHE, TUCKER, THOMSON & FLYNN, 2007). They argue that living in the present-day world is connected with massive changes for the self as a consequence of wider globalization processes, including changes with regard to the welfare state, increasing labor market insecurities and the loss of former traditional bonding. It means that new opportunities as well as risks and uncertainties have become fundamental components of people's everyday life. [3]

Although BECK's description of second modernity as a society where inequalities can no longer be explained through the dimension of class has been criticized (EVANS, 2002; LEHMANN, 2004; SHUCKSMITH, 2004; HÖRSCHELMANN & SCHÄFER, 2005; SHARLAND, 2006; WYNESS, 2006; FURLONG & CARTMEL, 2007; HÖRSCHELMANN & SCHÄFER, 2007), it is argued that the general characterization, which BECK and BECK-GERNSHEIM as well as GIDDENS provide for contemporary life conditions, are highly valuable as these authors "have been successful in identifying processes of individualization and risk which characterize late modernity and which have implications for lived experiences" (FURLONG & CARTMEL, 2007, p.2). This paper focuses on meanings and understandings of risk and uncertainties as expressed by participants of the study. It critically questions in how far BECK's, BECK-GERNSHEIM's and GIDDENS' conceptualization of risk helps to understand these young people's everyday experiences and how it affects their present day and future lives. [4]

BECK (1992) describes the new risks that people are facing in contemporary western societies as increased global risks, such as the threat of nuclear war and environmental disasters. He also refers to the risks which affect people on the basis of their everyday lives. This includes processes of de-traditionalization and individualization which, on the one hand, free the individual from former constraints. Young people are perceived as being in the position to choose from a range of different lifestyles, subcultures and identities so that "the individual himself or herself becomes the reproduction unit for the social in the life world" (BECK, 1992, p.130). [5]

On the other hand, however, these processes create new uncertainties and risks as people are increasingly forced to plan and reflexively (re)construct their biographies. It means that the self "has to be created and recreated on a more active basis than before" (GIDDENS, 2000, p.47) and has become a "reflexive project" (GIDDENS, 1994) for which the individual as an active agent has become responsible. The individual thus plays an important role in the construction of his/her own identity, which makes reflexively organized life-planning increasingly important (GIDDENS, 1994). BECK and BECK-GERNSHEIM (2002) and GIDDENS (1994, 2000) highlight that the increasingly demanded individualization can be perceived as a burden people have to cope with on an individual level (see also WALKERDINE, 2003; LEHMANN, 2004). It includes that experiences of structural inequalities are increasingly interpreted as personal failures (see BECK, 2002; SHUCKSMITH, 2004) which results in increased levels of pressure with which young people have to cope in creating their own biographies. [6]

Life, from this point of view, becomes a matter of personal decision while no clear guidelines are offered to help the individual to cope with these choices. The individual can therefore also be referred to as the "victim of individualization" (BECK & WILLMS, 2004), as "(t)he normal biography thus becomes the "elective biography', the 'reflexive biography', the 'do-it-yourself' biography. This does not necessarily happen by choice, neither does it necessarily succeed" (BECK & BECK-GERNSHEIM, 2002, p.3, see also BRAKE & BÜCHNER, 1996; FURLONG & CARTMEL, 2007). These pressures produce the characteristic feeling of living in the second modernity: the feeling of insecurity which becomes part of people's everyday life (GIDDENS, 1994). [7]

Similarly to GIDDENS, BECK has warned against the "misleading impression that everyone can take equal advantage of mobility and modern communications, and that transnationality has been liberatory for all people" (BECK 2002, p.31). However, BECK's and GIDDENS' work has been criticized for not providing a conceptual framework that explains why people do not profit or suffer equally from the new chances and risks of second modernity as more recent research indicates (EVANS, 2002; LEHMANN, 2004; SHUCKSMITH, 2004; WYNESS, 2006; FURLONG & CARTMEL, 2007). [8]

BECK's understanding of risk has further been criticized as it ignores the everyday construction of the meaning of risk and the different ways in which "reflexivity and individualization are experienced as part of personal biographies and how they are constructed via such categories as class and gender" (TULLOCH & LUPTON, 2003, p.66). Following a socio-cultural approach, TULLOCH and LUPTON (2003) focus on people's understandings and experiences of risk arguing that "risk knowledges" are context specific, historical and local. This socio-cultural analysis of young people's contextualized understandings and negotiations of everyday risks offers an opportunity to conceptually explore the multiple and diverse ways in which new risks and opportunities are perceived and experienced. MITCHELL, CRAWSHAW, BUNTON and GREEN (2001, p.219) have argued that these "everyday or lay accounts of risk as opposed to official accounts are extremely important as they help to give meaning to risk taking and risk rationalization in young people's lives." Such conceptualization of risk includes, for example, the understanding that risk-taking can be perceived both positively and negatively, and thus challenges "[s]ome aspects of the risk society thesis, particularly those contentions that tend to make sweeping generalizations about how 'late moderns' respond to risk" (TULLOCH & LUPTON, 2003, p.10). [9]

This approach supports EVANS' (2002) call to see young people as social actors in a social landscape. In line with recent research which has highlighted the importance of socio-geographic contexts for people's everyday lives (see GREEN, MITCHELL & BUNTON, 2000; GELDENS & BOURKE, 2008), this paper aims to contribute to a more complex understanding of young people's lives in second modernity. In particular, it will reflect on the socio-spatial dimension of risk by analyzing how young people link their rural, East German residency with their understanding and experience of everyday risks and uncertainties. This new analysis offers a better understanding of the multiple ways in which young people translate understandings of spatial differences for their present day and future lives. [10]

3. The Meaning of Risk in a Rural, Post-Socialist Context

Particularly with reference to the socio-economic situation in the countryside, contemporary research suggests that life in rural areas is problematic for young people (FURLONG & CARTMEL, 2007; FRANCIS, 1999; BAUR & BURRMANN, 2000; GLENDINNING, NUTTALL, HENDRY, KLÖP & WOOD, 2003; AUCLAIR & VANONI, 2004; MIDGLEY & BRADSHAW, 2006). GELDENS and BOURKE (2008) have shown that rurality is often constructed as being synonymous with risk and uncertainty. It could thus be argued that young people in rural regions have to face specific risks when creating their own biographies. In line with PANELLI (2002), I argue, however, that the negative image of the rural in general and of rural residency for young people in particular has to be challenged. Rural spaces are not only spaces of marginalization but also spaces of possibilities "where landscapes of youth can be read as terrains of creativity, conflict and change, flexing over the broader topography of political-economic processes and sociocultural systems" (PANELLI 2002, p.121). This does not mean that socio-spatial or economic disadvantages of rural residency do not need to be investigated in more detail as they are of high political relevance to address young people's rights. It rather refers to the aim of elaborating a more complex and heterogeneous understanding of rural space and the heterogeneity of young people's rural lives (see also NAIRN, PANELLI & McCORMACK, 2003). [11]

To gain such insights a post-modern understanding of rurality will be used defining it as a social construction which includes the "words and concepts understood and used by people in everyday talk" (HALFACREE, 1993, p.29). This approach puts the definition of rurality no longer down to particular statistical characteristics or to a general dichotomous concept which assumes a contrast between the rural and the urban but emphasizes the importance of images and perceptions of rurality. This post-modern awareness of the social construction of rurality calls for a focus on the different discourses of rurality from the perspective of its residents. The rural thus "becomes a world of social, moral and cultural values in which rural dwellers participate" (CLOKE & MILBOURNE, 1992, p.360). This produces a specific knowledge about the rural and what it means to be rural (WOODS, 2007) which impacts on people's attitudes and behavior. This concept of rurality reflects MASSEY's (1993) progressive understanding of place. She argues that place

"can be imagined as articulated movements in networks of social relations and understandings, but where a large proportion of those relations, experiences and understandings are constructed on a far larger scale than what we happen to define for the moment as the place itself" (p.239). [12]

MASSEY's (1993, 2005) approach rejects the assumption that places lose their significance and emphasizes in accordance with McDOWELL (1999) that everyday life is indeed a local affair that is globally connected. This conceptualization of place highlights that the spatial organization is a key element with regard to people's identity construction. It represents an important context within which young people growing up in rural East Germany make sense of their everyday experiences and the risks and uncertainties they might face. [13]

Research on young people's lives in the context of post-socialism (see RIORDAN, WILLIAMS & ILYNSKY, 1995; MACHÁČEK, 1997; SMITH, 1998; ROBERTS, CLARK, FAGAN & THOLEN, 2000; HÖRSCHELMANN, 2002; PILKINGTON, OMEL'CHENKO, FLYNN, BLIUDINA & STARKOVA, 2002; PILKINGTON & JOHNSON, 2003; PILKINGTON, 2004; HÖRSCHELMANN & SCHÄFER, 2005; NUGIN, 2008) showed, that values and norms developed in the past, as well as in the context of transformation continue to be relevant for how people experience and interpret present conditions. These findings challenge the perception of post-socialism as "a temporary, transitional category with no power beyond a limited historical and geographical moment" (STENNING, 2005, p.113). In the context of young people's lives in post-communist Estonia, NUGIN (2008) argues that the experiences of uncertainties in transition-societies are constantly changing. Her research shows that different age cohorts perceive and experience uncertainties differently. It indicates that transformation processes can affect groups of people differently and thus highlights the importance of socio-cultural approaches to uncover such differences. Such research, which focuses on people's perception of risk, further allows the analysis of the meaning of the socio-spatial dimension of risk which has been mostly neglected up to now (GELDENS & BOURKE, 2008). This article aims to address this gap by providing an insight into young people's perceptions of risk. It will be argued that it is crucial to take these spatial dimensions of risk into account to more fully understand how young people cope with, challenge and/or overcome experiences of disadvantage and risk and how they plan and prepare for their (future) lives. In the following I will give a brief outline of the research study before presenting some of the research findings. [14]

4. Background to the Research Project

Since reunification Mecklenburg-Vorpommern (MV) suffers from dramatic economical changes. It has been classed as an EU 1 region (BUNDESAMT FÜR BAUWESEN UND RAUMORDNUNG, 2000), which means that it belongs to one of the poorest and structurally weakest regions in Europe. This refers to various characteristics, such as a poorly developed infrastructure and high unemployment rates, which are more than twice as high as the national average. In 2005, 21,3% of the population in MV were unemployed, which affected 19% of young people under the age of 25 (STATISTISCHES LANDESAMT MECKLENBURG-VORPOMMERN, 2005, p.4). In addition, the birth-rate dropped drastically by more than 50% between the years 1989 and 1994 (STATISTISCHES LANDESAMT MECKLENBURG-VORPOMMERN, 2003, p.56), and is still in decline. Further, high out-migration rates of young people in particular characterize the region since reunification. This trend is supposed to continue (FISCHER & KÜCK, 2004; KRÖHNERT, VAN OLST & KLINGHOLZ, 2004) and refers to the main problem the region has to face. [15]

Although increasing rates of out-migration and decreasing birth-rates have been put on the political agenda in Germany, there is still a lack of qualitative research that focuses on the actual situation of young people's lives (DIENEL & GERLOFF 2003). Such insights, however, are needed to develop a more sustainable concept of keeping the standard of living in rural areas high and to offer young people the possibility to choose if they want to stay or leave their rural regions. [16]

My doctoral research aimed to address these issues by focusing on young people's everyday and future lives in rural East Germany (SCHÄFER, 2008). An in-depth, qualitative research project was designed which included the use of focus group discussions, research training for participants, facilitating peer-research and the development of smaller research projects which were designed, conducted and analyzed by participants themselves. This participatory research approach resulted in a high level of engagement of 67 14-16 year olds and provided a rich insight into their everyday lives and future prospects. Access to the participants was gained through five different schools in Mecklenburg-Vorpommern, one of the five "new federal states" that formerly belonged to the GDR (German Democratic Republic). At the beginning of the project a questionnaire survey was handed out by the teachers to all students in grade 8 and 10 which included questions regarding participants' socio-economic background, their educational level and general questions around their everyday lives. The return rate was 73% (n=124) which could be interpreted as young people's high interest in the research project. Some findings from this survey will be discussed here. Due to the fact that I could not be involved in the introduction and distribution of the questionnaires, however, I decided to treat findings from the questionnaire as additional information to further contextualize the analysis of the qualitative data I gathered. [17]

The main data, however, was generated in the next stage of the participatory research project which used a range of qualitative research methods (including focus group discussions, visual methods such as drawings, photographs, video filming), to gain a deeper insight into young people's perceptions and understandings of their everyday lives. Aiming for the research to be as inclusive as possible and to give all students the opportunity of making an informed decision about participating in the project, I presented the aims of the project in each school to students from one class in grade 8 and one in grade 10 (with ca. 15-20 pupils in each class). After the initial information session in which the project was introduced and participants' involvement was outlined, I met with those who expressed interest in the project and agreed the day and time of our weekly focus group discussions. The number of students who wanted to participate varied from 5-11 students per class. This meant that the final sample included 9 groups of young people with a total of 67 students (36 female, 31 male students). Three to five focus group discussions were conducted with each group (depending on their interest and motivation). In addition, research training was provided for young people to develop their own research projects on topics that were relevant to them. Here, however, I want to focus on findings from the focus group discussions which offer a valuable insight into young people's understanding and negotiation of risks. All focus group discussions were fully transcribed (in German) and analyzed following a grounded theory approach (GLASER & STRAUSS, 1967; STRAUSS & CORBIN, 1998). I followed the three stages of coding as described by STRAUSS and CORBIN (1998) who distinguish between open, axial and selective coding. While the first two steps of open and axial coding were done by hand on the print outs of the interview transcripts the final step of selective coding was done with the help of NUD*IST qualitative analysis software (N6). Quotations from the focus group discussions have been translated into English by the author after completion of the data analysis. [18]

It is important to highlight that the participants belong to the first generation which was born at the time of, or shortly before or after the reunification of the two German states in 1990. It means that they have not lived in the GDR themselves. The research thus aimed to get an insight into the ways in which growing up in a post-socialist country impacted on the young people's everyday lives. It could be assumed that young people might have developed an understanding of what it was like to live in the GDR through narratives of their parents and grandparents as well as through the experience of still existent customs and behaviors which refer back to the socialist socialization of their parents. Such understandings might have implications on how they perceive and experience the ongoing transformation processes and how they perceive experiences of disadvantage and risk. [19]

5. Young People's Perception of the Disadvantages and Risks of Growing up in Rural East Germany

It became clear in the course of the research that participants connected a number of disadvantages and risks with their rural East German residency. However, young people distinguished clearly between those disadvantages and risks which they characterized as rural and those which they perceived as East German. In the following I will firstly introduce the dimensions which participants identified as rural disadvantages, to then analyze their perception of risks which they perceived as being connected with living in East Germany. [20]

Participants identified a range of disadvantages which they perceived as characteristic for growing up in the countryside. The following table (Table 1) lists the most frequently discussed disadvantages and further includes some of the strategies participants referred to in the focus group discussions as ways to cope with or overcome them.

|

Disadvantages of growing up rural |

Strategies to overcome experienced disadvantages |

|

Lack of shopping facilities |

Travel to other towns/cities: on their own with their parents Order via Internet |

|

Lack of leisure facilities |

Travel to other places (driven by parents) Meet with friends at home or in public/outdoor places |

|

Poor transport facilities |

Cycling Getting driving license Asking friends who can drive Use the Internet to overcome spatial distances |

|

Limited number of peers at place of residency |

Use Internet to build up friendships Pen-friends in other parts of the country |

|

Social pressure and control |

Aiming to "fit in" Creating own spaces confronting or escaping adult control Considering out-migration |

|

Gender specific job opportunities (identified by female participants) |

Conforming to normative expectations Trying to rebel against normative expectations Considering out-migration |

Table 1: Participants' perceptions of the disadvantages of growing up in a rural region [21]

While the motivation and ability to develop strategies to challenge perceived disadvantages varied immensely amongst the participants, it became clear that they all shared the understanding, that most of these disadvantages were only temporary. Participants argued, for example, that their opportunities to make use of services and facilities within the region would increase when they were getting older as they would become more mobile (through, for example, having a car or being able to afford public transport or pay for a taxi). It further means that although all participants raised the issue of limited public transport they did not perceive it as something that had to be urgently addressed as the problem would dissolve—at least to some extend—when they were becoming older. [22]

In contrast to these "temporary" disadvantages, however, participants found it much more difficult to challenge or cope with experiences of social pressure and control or normative expectations connected with, for example, gender specific roles. Such issues were particularly referred to by female participants. The following quotes are characteristic for the comments the girls/young women made in the focus group discussions.

Melanie (16, f)1): When you walk through the village, when we have a family festivity then they [people in the village] watch you. They all sit at their windows—stuck to the glass. And next day they all tattle about it: who it was and how much she has changed and so on. And then the gossip goes on until you pass their windows again. And I think that is much worse for the girls than for the boys.

Anja (16, f): If you gain a bad reputation in [name of the village] it goes around the whole world. It really does! (...) Well, probably not the whole world but all the young people in surrounding villages will know about it. And some weeks later, when you have probably forgotten all about it somebody will come up to you and say: "oh, what have you done," you know. That is really weird. [23]

Those participants who referred to experiences of social pressure and gender specific expectations often considered leaving their rural environment when they were older. It supports findings by GELDENS and BROUKE (2008) which indicate that rural communities provide young people with reduced choices of identity formation. GLENDINNING et al. (2003) have further described rural communities as a "fish bowl" where young people are confronted with a high level of social pressure to conform to local cultural expectations. The authors argue that gender is a key dimension affecting young people's feelings about their communities. [24]

The dimensions of rural disadvantages which participants identified were generally in line with those to which young people growing up in other European regions refer to (see BÖHNISCH & WINTER, 1990; FRANCIS, 1999; BAUR & BURRMANN, 2000; AUCLAIR & VANONI, 2004; COMMISSION FOR RURAL COMMUNITIES, 2005; FURLONG & CARTMEL, 2007). They thus represent forms of structural disadvantages which are not unique to the East German but characteristic for rural contexts. It highlights that socio-geographic contexts play an important role with regard to young people's experiences and perceptions of everyday risks and opportunities (GREEN et al., 2000; GLENDINNING et al., 2003; GELDENS & BOURKE, 2008; NUGIN, 2008). [25]

In the course of the project, it became further clear that participants were particularly concerned about their future careers. They repeatedly discussed issues such as the risk of unemployment, lack of job opportunities and limited ways of preparing themselves for the transition from school to work. The perception of being at risk of becoming unemployed was reinforced by young people's experiences that even those who are willing to work can end up in long-term unemployment, as 16 year old Ann described:

Ann (16, f): My mum has been unemployed for more than 6 Years now. She has written so many applications—we could use them as wall-paper for the whole flat now. [26]

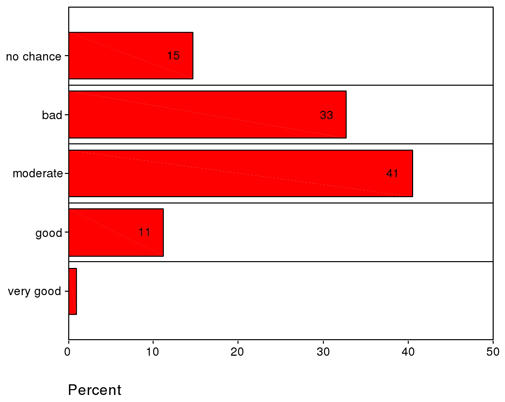

Being asked how they perceived their chances of finding a job within the region in the questionnaire, nearly half of the participants (48%) ranked their personal job opportunities as bad or without reasonable chance, while 41% described their chances as moderate (see figure 1). Less than 12% of young people described their chances as good, including one respondent who described his/her chance as very good. These perceptions of future chances within the region were not significantly dependent on gender (p=0.485), age (p=0.185) or educational achievement of respondents (p=0.728).

Figure 1: Perception of future job opportunities in the region (n=123) [27]

Participants gave similar responses with regard to the question about whether or not they worried about the job situation in the region. The majority of students (63%) stated that they sometimes worried about the job situation while nearly every third participant (27%) indicated that they worried often about their future career. Only 10% of respondents stated that they did not worry at all. When analyzing young people's level of concern by using Mann Whitney, no significant differences were found in relation to participants age (p=0.107) or educational level (p=0.306). It became clear, however, that female participants were more likely to worry than boys (U=1375.000; p=0.049). This was confirmed in the focus group discussions where female participants repeatedly indicated that they might have fewer opportunities to find work within the region than for their male peers. Antje, for example, described it as follows:

Antje (16, f): But I think there are not many job opportunities for girls. I mean, well, if I was a boy, for example, then I would have become a mason or a road builder or a house-painter. [28]

This perception of gender specific job opportunities corresponds with research on rural youth in other European countries which has highlighted that girls and young women often perceive their job prospects within rural regions as more restricted than their male counterparts (see LITTLE, 1986; BELL & VALENTINE, 1995; DAHLSTROEM, 1996; LITTLE, 1997, 2002a, 2002b; GLENDENNING et al., 2003; LITTLE & LEYSHON, 2003; LITTLE & PANELLI, 2003). [29]

Despite the gender difference in the extent to which young people worried about their future lives it became clear, however, that this worry represented a general concern among the participants. The majority of young people in this study thus repeatedly referred to feelings of being at risk of getting a poor education or job training and/or of becoming unemployed. The analysis of the focus group discussion revealed that this concern was highly interlinked with their understanding of growing up in post-socialist East Germany. Contrary to most issues which participants identified as being connected with their rural residency (but in line with the issue of social pressure and gender specific expectations), these issues seemed to be perceived as long-term disadvantages and thus as creating potential risks regarding young people's future lives. [30]

Participants referred to the understanding of still persisting fundamental East-West German differences which they often described as having strong implications for the job market. Robert (16), for example, argued that East-West German differences were still apparent in the way in which jobs were accessed:

Robert (m, 16): I think the only way to get a job in East Germany is through connections. That is quite different in the West. Here, I have heard a lot of people saying: my father works there and now I got a job there too. That never happens in the West. There, you do your interview and then they choose the one who is best qualified for the job. And I prefer it that way. [31]

Participants repeatedly referred to East-West German differences with regard to the job market and job opportunities (see Table 2).

|

Situation in East Germany |

Situation in West Germany |

|

Poor job situation |

More jobs |

|

Lower salary |

Higher salary |

|

Types of jobs restricted |

Variety of jobs available |

|

Getting a job is dependent on connections |

Getting a job is dependent on personal qualification |

Table 2: Young people's perceptions of differences between East and West Germany [32]

The risk of unemployment was understood as an East German and thus as a spatial disadvantage that affected not only young people but everybody who was growing up and living in the Eastern part of the country. It indicates that young people perceived themselves as living in a marginalized East German region rather than as marginalized rural citizens or marginalized (rural) youth. It refers to a process of the "normalization of risks," as perceived risks have become a normal part of (young) people's everyday lives (see GREEN et al., 2000). This spatial understanding of risk challenges the concept of risk as used by GIDDENS and BECK and highlights that socio-spatial dimensions of young people's everyday lives have strong implications on their risk knowledges. The latter is important, however, to better understand the choices young people make and the strategies they develop to cope with, challenge and/or overcome perceived risks. Further, such insights allow to rethink the appropriateness and need of governmental policies, youth services and needs of young people and can help to address issues of inequalities and to support young people achieving their full potential and dreams. These findings of the spatial dimension of young people's perception and understanding of risk highlight the value of MASSEY's (1993) conceptualization of space in terms of the complexity of interacting social relations and the importance of space and locality within young people's perceptions of others as insiders and outsiders. In the following section, I want to analyze in more depth how participants made sense of perceived spatial disadvantages, risks and opportunities and which implication this had on their everyday and future lives. [33]

6. Negotiating Risk: Who Benefits and Who Struggles?

The majority of participants highlighted that socialist experiences and values still had a major impact on their parents' present-day life. It indicates that people's experiences in post-socialist countries are often still shaped by norms and values which were developed in the socialist past (see also RIORDAN et al., 1995; MACHÁČEK, 1997; SMITH, 1998; ROBERTS et al., 2000; HÖRSCHELMANN, 2002; PILKINGTON et al., 2002; PILKINGTON & JOHNSON, 2003; PILKINGTON, 2004; HÖRSCHELMANN & SCHÄFER, 2005). At the same time, participants argued, however, that the transformation process affected them differently from the older generations. Participants often emphasized that they had actually not experienced living in a socialist country themselves. The differentiation between those who grew up under socialism, such as their parents and grandparents, and those who were born into a unified country like themselves became particularly clear in Anna's description of the differences between her own and her father's present day life:

Anna (15, f): My father always says that he could not survive in the West as he grew up in a completely different world. So he has to stay here. He taught me that the West Germans are different but that it is not their fault, really, and they are not really bad. They are just different. My dad believes that I will do fine there and I think so too. I really want to go there to find a good job and I know I won't have any problems there at all; it is just that my father is too old now to live there. [34]

Anna made a clear distinction between her father's and her own (future) life. The East, according to Anna's explanation, still offered a safe place for her father to live; while the West represented the world of "capitalism" which he was not used to and within which he could not survive. The Eastern and Western German parts were thus perceived by Anna as still being divided along the former borders. This perception was shared by all participants and was connected with their understanding that different skills were needed to survive in each part of the country. [35]

From the participants' point of view, people who were socialized in the GDR were often perceived as facing more risks than the younger generation, because it seemed nearly impossible for the former to build a bridge between their socialist upbringing and capitalism. This was explained on the one hand by the poor socio-economic situation, an outcome of the collapse of the socialist system and the transformation process. On the other hand, it was strengthened by young people's perception that the older generations were often unable or unwilling to make use of the new opportunities, because they were still affected by their socialist upbringing. Young people described the older generations thus often as being trapped spatially in the East German part unable to survive in the capitalist West. For Anna, it seemed to mean that she had to physically move and thus leave her father as well as East Germany behind to be able to build her own life in reunified (Western) Germany. Such understanding was also reflected in participants' perception of East Germany as a good place to spend holidays or to return to after retirement but not as a place for young people to live and build up their careers. [36]

Anna's quote brings to the point what the majority of participants repeatedly highlighted during the focus group discussions: that reunification had opened new opportunities and chances for the young generation. These opportunities, however, were perceived as being available in the West. East Germany, on the other hand, was perceived by participants as a place of stagnation which offered young people only very limited opportunities for their future lives, as people's everyday lives were still closely linked with its socialist past. Even though there were differences amongst young people with regard to their willingness and wish to migrate to the West, the majority of participants shared this understanding. It indicates that the discourse on still existing East-West German differences did build an important part of young people's understanding of the living conditions in reunified Germany. [37]

This seems to reflect findings from a study on East Germans' perceptions of their lives in unified Germany by FÖRSTER (2004). Looking at East Germans who were born in 1972/73 and who thus roughly represent the parental generation of my own participants, FÖRSTER found that East Germans often did not connect a positive perception of the future with their East German residency. His participants particularly highlighted, however, that they were even more concerned about their children's future in the Eastern part of the country. It could indicate that the perception of the "East" as the "past" and the "West" as the "future" might be deeply rooted in people's perception of everyday life conditions in unified Germany. Such understanding is also reflected in the dominant public inner-German discourse on the still existent East German otherness as (re)produced in the media (see HÖRSCHELMANN, 2001, 2002, 2007; SCHLOTTMANN, 2005). It indicates how deeply rooted these spatial perceptions of risks can be and raises the questions of how to challenge such perceptions of still existing fundamental differences. [38]

7. Making Sense of Perceptions and Experiences of Everyday Risks

This section focuses on the implications which young people's perception of growing up rural and of still existing differences between East and West Germany had on their understanding of and preparation for their future lives. I will start by looking at a key dimension which young people identified as important for a successful transition into the job market (see also SCHÄFER, 2007). It will then be shown how such understandings are interlinked with their spatial perception of risks and opportunities and how they translated this for their own (future) lives. [39]

Participants shared the understanding that education represented one of the key dimensions to improve their chances in the job market. However, their everyday experiences were often contradictory to such understanding, as better qualifications or higher degrees did not always guarantee greater success in the job market. Participants often referred to experiences of friends, family or community members who were struggling to get a job, even though they had achieved exceptionally good school leaving qualifications.

Nadine (16, f): But some leave with the best marks and they also don't get a job. I know a girl who had a really tough time. She was here last year and got a first in her school exams and could hardly find a job.

I: But generally would you say when you are really good in school and when you are a bit clever then you have a good chance [to get a job]?

Patrick (16, m): No.

Anja (16, f): No (...) Well some people who are really good [at school] still haven't found any vocational training places yet. [40]

Participants tried to make sense of these contradictory experiences and to translate them into strategies for their own future lives. It seemed often unclear to participants, however, how best to improve their job opportunities. Some participants had experienced, for example, that going for higher education could even become an obstacle to find a good job:

Tanja (14, f): It could happen that a student from a Realschule2) has really high marks whereas the student from the Gymnasium has only moderate results.

Manuela (14, f): Yes, then it is better to have a better Realschule-degree.

Tanja (14, f): It means that having an Abitur is probably not always an advantage.

I: Well, but then you can study at University.

Dirk (14, m): Yeah, but I have read in a newspaper that they [employers] had one applicant from a Gymnasium and one from a Realschule and they did not take the student from the Gymnasium but the other one! [41]

As for reasons why employers may choose a Realschule-student over a student from a Gymnasium, participants referred to financial aspects that make it more attractive to employ less educated people:

I: Do you think that everybody has equal chances to get a job?

Christiane (16, f): No, not at all. I mean, well, sometimes you have to have really good marks, but on the other hand: when you have Abitur and your marks are too good, then they can't pay you. I mean, that is weird. You really don't know what to do.

Anja (16, f): Yeah, over-qualified.

Christiane (16, f): Yes, that's the risk. [42]

Referring to examples from the local job market where higher education had not helped to improve people's job chances, some students thus concluded that the effort to get Abitur and spending another three years in school may even increase the risk of unemployment. Patrick, for example, pointed out:

Patrick (16, m): I mean, nowadays you have to consider if you really want to get A-levels. If you do Abitur you lose several years and then the unemployment rate is even higher than it is today. You should really think twice about it. [43]

It became clear in the focus group discussions that participants did not expect the job situation to improve over the next few years. Staying in higher education was thus understood by some as worsening their already limited chances, and thus creating additional risks. The translation of these local experiences into strategies to improve their own position in the job market did therefore sometimes include not aiming for the highest possible qualification. [44]

Participants further identified issues which they perceived as possibly putting themselves at risk. This included the option of taking on vocational training in the region. The participants perceived the opportunities of gaining vocational training not only as limited but also highlighted that the working conditions and financial implications of getting the training locally were putting them at additional risk, such as financial independence.

Melanie (16, f): You have to work for three months [in the company] without getting paid. Three months, that's incredible (...) and even then you can't be sure that you get the training. I really don't know how you are supposed to finance this.

Anja (16, f): I am really scared, because it happened to my sister when she finished school. She was on vocational training and she had to count every penny. She couldn't even buy a pair of shoes because she wasn't earning enough! [45]

Again, such perceptions and experiences often resulted in young people considering leaving the region and probably migrating to West Germany to build up their careers. It indicates that participants generally shared the understanding that education and additional qualifications are key entering the job market. Preparing yourself for the job market, however, was perceived as being connected with additional risks in the context of their rural East German environment. [46]

Referring to research on unemployment in rural areas conducted by CARTMEL and FURLONG (1997), SHUCKSMITH (2000) highlights that rural young people are generally integrated in two separate labor markets: the national labor market on the one hand and the local labor market on the other hand. The first is characterized as the distant and often well paid market. Access to this market, according to SHUCKSMITH (2000), is mainly dependent on education and social background. In contrast to this, rural young people also have access to a poorly paid, often insecure local job market within which their prospects are highly limited. [47]

Participants' ambiguous description of education as both enabling and restricting mirrors their experiences of two quite separate labor markets. Here, it becomes important that participants perceived their local environment as typically East German rather than typically rural. They thus distinguished between two different job markets which they perceived as being characterized by East-West German rather than urban-rural differences. Participants argued that higher education and qualifications were more important in the West German job market. This had implications on, for example, their career and migration plans. For those who considered staying in East Germany it thus made sense to translate local experiences into strategies to best prepare themselves for the regional/urban market as the local job market was perceived as representative for the East German job market. This meant, however, that those participants who were hoping or saw a possibility of staying within the region (and/or within East Germany) perceived "under-achievement" as a sensible strategy. Following this strategy, however, might disadvantage them to succeed in the context of more competitive urban job markets in the region and thus reduce their chances in towns and cities in their direct environment. [48]

MÜLLER (2001) has further highlighted that young people growing up in East Germany have often experienced a devaluation of their parent's qualifications in the transformation process. In her research on risks and opportunities of rural East German youth in the local and regional job market, MÜLLER found that such experiences sometimes resulted in an understanding that education and qualification does not always lead to success in the job market. This had a strong impact on the strategies young people chose to improve their personal chances, resulting in the development of negative assimilation strategies (MÜLLER, 2001, p.220) such as getting a lower qualification. The development of such strategies, however, might exclude these young people even more. [49]

Participants of this research study were born at the time of unification and thus had not gained experiences of growing up in a socialist country or of the immediate changes connected with reunification in 1990. This could explain why they did not directly refer to experiences of "disqualification" as described by MÜLLER (2001), nor did they refer to such experiences of their parents or grandparents. However, it could be assumed that the understanding and meaning of education is highly contested amongst older generations due to experiences of "devaluation" which could result in a perception that aiming for the highest educational level might not guarantee successful transition into the job market. Further research should analyze parental understandings of the meaning of education and how it impacts on the ways young people are prepared or prepare themselves for the future transition into the job market. [50]

The analysis indicates that young people's perception of the risks and uncertainties which characterize their everyday lives is influenced by their understanding of spatial differences. Participants in this study reflected in particular on two spatial dimensions: the meaning of growing up growing up in a rural area and of growing up in post-socialist Germany. Most disadvantages and risks which participants identified as typically rural were in line with those identified in other European studies on young people's rural lives (see BÖHNISCH & WINTER, 1990; FRANCIS, 1999; BAUR & BURRMANN, 2000; AUCLAIR & VANONI, 2004; COMMISSION FOR RURAL COMMUNITIES, 2005; FURLONG & CARTMEL, 2007). It highlights the importance of local contexts and thus strengthens the call for a socio-spatial conceptualization of risk. [51]

With regard to their future lives, however, the second dimension of spatial differences seemed to be even more important. Participants clearly identified poor job and training opportunities as the main disadvantage of their East German residency. Reunification was understood, however, as having created new options to realise personal aims and ambitions, giving East Germans access to the West German and international job market. Participants thus highlighted that leaving the region and building a career somewhere else (most likely in West Germany) was perceived as an opportunity which had emerged with the fall of the wall. The transformation process was thus understood as having opened up new choices rather than a burden or additional disadvantage (see also NUGIN, 2008). Young people also generally perceived themselves as being able to exercise choice and control over their lives and often highlighted that it was up to them to overcome perceived disadvantages. [52]

On the other hand, young people (re)produced popular stereotypes that referred to essential differences between East and West Germans with regard to lifestyles and values. They highlighted that the socialist upbringing of their parents and grandparents still had a major impact on people's life in East Germany resulting in essential differences between the two parts of Germany. Young people even predicted the persistence of this German-German divide for at least another generation. These understandings seemed to be constantly reproduced not only by the older generations but also by the media which had a strong impact on participants understanding of the East-West German relationship. Young people did not, however, problematize these issues as structural inequalities. They rather highlighted the emergence of opportunities and their responsibility to take advantage of them individually. It means that participants did not describe themselves generally as the losers of reunification but rather highlighted the increasing opportunities which were perceived as being available to develop their future job-careers in the West. According to the understanding that their economic disadvantage was connected to their geographical position the opportunity to migrate was therefore seen as a way to take responsibility for their own lives. [53]

These findings indicate that the spatial dimensions of young people's experience and perceptions of risks (and opportunities) need to be taken into account to better understand which strategies they develop to cope with and challenge such risks. Such insights will also offer new opportunities to critically evaluate and re-think which services and support young people need to create their own biographies and to overcome experienced disadvantages and risks. [54]

Participants' understanding that people are affected differently by the transformation process and that the younger generation might have more chances to profit from new opportunities which emerged with reunification of the two German states challenges BECK's and GIDDENS' understanding that global risks represent key concerns of (young) people's everyday lives. It rather highlights that risk knowledges are context specific (TULLOCH & LUPTON, 2003) and that socio-spatial landscapes (EVANS, 2002) matter with regard to young people's creation of their own biographies. The perception and experiences of risks can thus be different for different people at different times and in different places. [55]

Finally, the findings challenge both, the descriptions of East German youth as losers of reunification and the over-generalized assumption that an East German identity can be understood as the outcome of East Germans' feelings of being treated as second class citizens in a united Germany (MEULEMANN, 1998). They rather highlight the importance of understanding young people's perceptions and experiences of everyday risks with regard to the socio-spatial, economical and cultural contexts in which they are growing up (see also GREEN et al., 2000; TULLOCH & LUPTON, 2003; NUGIN, 2008). The findings strengthen the call for a socio-cultural conceptualization of risk and provide an original insight into the multiple ways in which young people experience and negotiate their everyday lives. It calls for more conceptual and empirical work to analyze the meaning of space in the context of young people's lives in second modernity. Such research will help to gain a better understanding of who suffers and who benefits from (new) risks and uncertainties in western societies. [56]

Acknowledgments

A draft of this paper was presented at the International Sociological Association Forum of Sociology, in the session "Sociology of Risk and Uncertainties," Barcelona September 5- 9, 2008. I am grateful for the additional financial support of the Seale Hayne Educational Trust and the Foundation for Urban and Regional Studies for this doctoral study, which was funded by the School of Geography, University of Plymouth.

1) Participants' names have been anonymized. Their age (in years) and gender (f=female, m=male) is indicated in brackets. "I" is used for the interviewer. <back>

2) The qualifications which can be achieved at the different German school types can be translated into the English system as follows: Förderschule = Special Educational Needs School; Hauptschulabschluss = Pre-GCSE, Realschulabschluss = GCSE (Realschule), Abitur = A-Level (Gymnasium). <back>

Auclair, Elizabeth & Vanoni, Didier (2004). The attractiveness of rural areas for young people. In Birgit Jentsch & Mark Shucksmith (Eds.), Young people in rural areas of Europe (pp.74-104). Aldershot: Ashgate.

Baur, Jürgen & Burrmann, Ulrike (2000). Unerforschtes Land: Jugendsport in ländlichen Regionen. Aachen: Meyer und Meyer.

Beck, Ulrich (1992). Risk society: Towards a new modernity. London: Sage.

Beck, Ulrich (2000). What is globalization? Cambridge: Polity Press.

Beck, Ulrich (2002). The cosmopolitan society and its enemies. Theory, Culture and Society, 19(1-2), 17-44.

Beck, Ulrich & Beck-Gernsheim, Elisabeth (2002). Individualization. Institutionalized individualism and its social and political consequences. London: Sage.

Beck, Ulrich & Willms, Johannes (2004). Conversations with Ulrich Beck. Cambridge: Polity Press.

Bell, David & Valentine, Gill (1995). Queer country: Rural lesbian and gay lives. Journal of Rural Studies, 11(2), 113-122.

Böhnisch, Lothar & Winter, Reinhard (1990). Pädagogische Landnahme. Einführung in die Jugendarbeit des ländlichen Raums. München: Juventa Verlag.

Brake, Anna (1996). Wertorientierung und (Zukunfts-)Perspektiven von Kindern und jungen Jugendlichen. Über Selbstbilder und Weltsichten in Ost- und Westdeutschland. In Peter Büchner, Burkhard Fuhs & Heinz-Hermann Krüger (Eds.), Vom Teddybär zum ersten Kuss. Wege aus der Kindheit in Ost- und Westdeutschland (pp.67-98). Opladen: Leske + Budrich.

Brake, Anna & Büchner, Peter (1996). Kindsein in Ost- und Westdeutschland. Allgemeine Rahmenbedingungen des Lebens von Kindern und jungen Jugendlichen. In Peter Büchner, Burkhard Fuhs & Ingrid Burdewick (Eds.), Jugend – Politik – Anerkennung. Eine qualitative empirische Studie zur politischen Partizipation 11 bis 18-Jähriger (pp.43-66). Bonn: Leske + Budrich.

Bundesamt für Bauwesen und Raumordnung (2000). Raumordnungsbericht 2000. Bonn: Selbstverlag des Bundesamtes für Bauwesen und Raumordnung.

Burdewick, Ingrid (2003). Jugend – Politik – Anerkennung. Eine qualitative empirische Studie zur politischen Partizipation 11 bis 18-Jähriger. Bonn: Leske + Budrich.

Cloke, Paul & Milbourne, Paul (1992). Deprivation and lifestyles in rural Wales: II. Rurality and the cultural dimension. Journal of Rural Studies, 8(359), 371.

Commission for Rural Communities (2005). Rural disadvantage: Our first thematic study. London: CRC Publication.

Dahlstroem, Margareta (1996). Young women in a male periphery—Experiences from the Scandinavian North. Journal of Rural Studies, 12(3), 259-271.

Hurrelmann, Klaus; Albert, Mathias & Infratest Sozialforschung (2002). Jugend 2002. Zwischen Pragmatischem Idealismus und Robustem Materialismus. Frankfurt/M.: Fischer.

Hurrelmann, Klaus; Albert, Mathias & TNS Infratest Sozialforschung (2006). Jugend 2006 – Eine pragmatische Generation unter Druck. 15. Shell Jugendstudie. Frankfurt/M.: Fischer.

Dienel, Christiane & Gerloff, Antje (2003). Geschlechtsspezifische Besonderheiten der innerdeutschen Migration für Sachsen-Anhalt. In Thomas Claus (Ed.), Gender-Report Sachsen-Anhalt 2003. Daten, Fakten und Erkenntnisse zur Lebenssituation von Frauen und Männern (pp.47-64). Magdeburg: Gender-Institut Sachsen-Anhalt (G/I/S/A).

Evans, Karen (2002). Taking control of their lives? Agency in young adult transitions in England and the New Germany. Journal of Youth Studies, 5(3), 245-269.

Evans, Karen; Behrens, Martina & Kaluza, Jens (1999). Risky voyages: Navigating changes in the organisation of work and education in Eastern Germany. Comparative Education, 35(2), 131-150.

Fischer, Hartmut & Kück, Ursula (2004). Bevölkerungsentwicklung und Migration von 1990 bis 2002: Berlin und die neuen Bundesländer im Vergleich. Statistische Monatszeitschrift, 11, 420-426.

Förster, Peter (2003). Junge Ostdeutsche heute: doppelt enttäuscht. Ergebnisse einer Längsschnittstudie zum Mentalitätswandel zwischen 1987 und 2002. Aus Politik und Zeitgeschichte, 15, 6-17.

Förster, Peter (2004). Ohne Arbeit keine Freiheit. Warum junge Ostdeutsche rund 15 Jahre nach dem Susammenbruch des Sozialismus noch nicht im gegenwärtigen Kapitalismus angekommen sind. Leipzig: Rosa-Luxemburg-Stiftung.

France, Alan (2007). Understanding youth in late modernity. Maidenhead: Open University Press.

Francis, Leslie (1999). The benefits of growing up in rural England: A study among 13-15-year-old females. Educational Studies, 25(3), 335-341.

Furlong, Andy & Cartmel, Fred (1997). Young people and social change: Individualisation and late modernity. Buckingham: Open University Press.

Furlong, Andy & Cartmel, Fred (2007). Young people and social change. New perspectives. Maidenhead, NY: Open University Press.

Geldens, Paula & Bourke, Lisa (2008). Identity, uncertainty and responsibility: Privileging place in a risk society. Children's Geographies, 6(3), 281-294.

Giddens, Anthony (1990). The consequences of modernity. Stanford: Stanford University Press.

Giddens, Anthony (1991). Structuration theory: Past, present and future. In Christopher Bryant & David Jary (Eds.), Giddens' theory of structuration. A critical appreciation (pp.201-221). London: Routledge.

Giddens, Anthony (1994). Modernity and self-identity. Self and society in the late modern age (4th ed.). Cambridge: Polity Press.

Giddens, Anthony (2000). Runaway world. How globalisation is reshaping our lives. London: Profile Books.

Glaser, Barney & Strauss, Anselm (1967). The discovery of grounded theory: Strategies for qualitative research. Chicago: Aldine.

Glendinning, Anthony; Nuttall, Mark; Hendry, Leo; Klöp, Marion & Wood, Sheila (2003). Rural communities and well-being: a good place to grow up? Sociological Review, 51(1), 129-156.

Green, Eileen; Mitchell, Wendy & Bunton, Robin (2000). Contextualizing risk and danger: An analysis of young people's perceptions of risk. Journal of Youth Studies, 3(2), 109-126.

Griffin, Christine (2001). Imagining new narratives of youth: Youth research, the "new Europe" and global youth culture. Childhood, 8(2), 147-166.

Halfacree, Keith (1993). Locality and social representation: Space, discourse and alternative definitions of the rural. Journal of Rural Studies, 9(1), 23-37.

Hörschelmann, Kathrin (2001). Breaking ground—marginality and resistance in (post) unification Germany. Political Geography, 20(8), 981-1004.

Hörschelmann, Kathrin (2002). History after the end: Post-socialist difference in a (post)modern world. Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers, 27(1), 52-66.

Hörschelmann, Kathrin (2007). Defining the subject of speech—Constructions of authorship in post-unification German media discourses. Geoforum, 38(3), 456-468.

Hörschelmann, Kathrin & Schäfer, Nadine (2005). Performing the global through the local—globalisation and individualisation in the spatial practices of young East Germans. Children's Geographies, 3(2), 219-242.

Hörschelmann, Kathrin & Schäfer, Nadine (2007). "Berlin is not a foreign country, stupid!"—Growing up "global" in eastern Germany. Environment and Planning A, 39(8), 1855-1872.

Jentsch, Birgit (2004). Experience of rural youth in the "risk society": Transitions from education to the labour market. In Birgit Jentsch & Mark Shucksmith (Eds.), Young people in rural areas of Europe (pp.237-267). Aldershot: Ashgate.

Jentsch, Birgit & Shucksmith, Mark (Eds.) (2004). Young people in rural areas of Europe. Aldershot: Ashgate.

Kollmorgen, Raj (2003). Das Ende Ostdeutschlands? Zeiten und Perspektiven eines Forschungsgegenstandes. Berliner Debatte Initial, 14(2), 4-18.

Kröhnert, Steffen; van Olst, Nienke & Klingholz, Reiner (2004). Mecklenburg-Vorpommern. Das wichtigste Kapital sind die Leere und die Landschaft. In Steffen Kröhnert, Nienke van Olst & Reiner Klingholz (Eds.), Deutschland 2020. Die demographische Zukunft der Nation (pp.36-40). Berlin: Berliner Institut für Bevölkerung und Entwicklung.

Lehmann, Wolfgang (2004). "For some reason, I get a little scared": Structure, agency, and risk in school-work transitions. Journal of Youth Studies, 7(4), 379-396.

Little, Jo (1986). Feminist perspectives in rural geography: An introduction. Journal of Rural Studies, 2(1), 1-8.

Little, Jo (1997). Constructions of rural women's voluntary work. Gender, Place and Culture—A Journal of Feminist Geography, 4(2), 197-210.

Little, Jo (2002a). Gender and rural geography. Identity, sexuality and power in the countryside. Harlow: Pearson Education Limited.

Little, Jo (2002b). Rural geography: Rural gender identity and the performance of masculinity and femininity in the countryside. Progress in Human Geography, 26(5), 665-670.

Little, Jo & Leyshon, Martin (2003). Embodied rural geographies: Developing research agendas. Progress in Human Geography, 27(3), 257-272.

Little, Jo & Panelli, Ruth (2003). Gender research in rural geography. Gender, Place and Culture—A Journal of Feminist Geography, 10(3), 281-289.

Macháček, Ladislav (1997). Individualisation of the first post-communist generation in the Slovak Republic. Sociológia, 29(3), 249-257.

Massey, Doreen (1993). A global sense of place. In Ann Gray & Jim McGuigan (Eds.), Studying culture. An introductory reader (pp.232-240). London: Edward Arnold.

Massey, Doreen (2005). For space. London: Sage.

McAuley, Alastair (1995). Inequality and poverty. Russia in transition: Politics, privatisation and inequality. London: Longman.

McDowell, Linda (2002). Transitions to work: Masculine identities, youth inequality and labour market change. Gender, Place and Culture—A Journal of Feminist Geography, 9(1), 39-59.

Meulemann, Heiner (1998). Werte und nationale Identität im vereinten Deutschland: Erklärungsansätze der Umfrageforschung. Opladen: Leske & Budrich.

Midgley, Jane & Bradshaw, Ruth (2006). Should I stay or should I go? Rural youth transitions. Newcastle: Institute for Public Policy Research.

Mitchell, Wendy; Crawshaw, Paul; Bunton, Robin & Green, Eileen (2001). Situating young people's experiences of risk and identity. Health, Risk & Society, 3(2), 217-233.

Müller, Karin (2001). Arbeitsmarktrisiken und berufliche Chancen Jugendlicher in ländlichen Räumen. Beiträge zur Arbeitsmarkt- und Berufsforschung Beitrag AB 249. Nürnberg: Institut für Arbeitsmarkts- und Berufsforschung der Bundesanstalt für Arbeit.

Nairn, Karen; Panelli, Ruth & McCormack, Jaleh (2003). Destabilizing dualisms: Young people's experiences of rural and urban environments. Childhood, 10(1), 9-42.

Nugin, Raili (2008). Constructing adulthood in a world of uncertainties. Some cases of post-Communist Estonia. Young, 16(2), 185-207.

Panelli, Ruth (2002). Young rural lives: Strategies beyond diversity. Journal of Rural Studies, 18(2), 113-122.

Pilkington, Hilary (2004). Youth strategies for glocal living: Space, power and communication in everyday cultural practice. In Andy Bennett & Keith Kahn-Harris (Eds.), After subcultures. Critical studies in contemporary youth culture (pp.119-134). Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

Pilkington, Hilary & Johnson, Richard (2003). Peripheral youth: Relations of identity and power in global/local Context. European Journal of Cultural Studies, 6(3), 259-283.

Pilkington, Hilary; Omel'chenko, Elena; Flynn, Moya; Bliudina, Ul'iana & Starkova, Elena (2002). Looking West? Cultural globalization and Russian youth cultures. Pennsylvania: Pennsylvania-State University Press.

Riordan, James; Williams, Christopher & Ilynsky, Igor (1995). Young people in post-communist Russia and Eastern Europe. Aldershot : Dartmouth Publishing Company.

Roberts, Ken; Clark, Stanley C.; Fagan, Colette & Tholen, Jochen (2000). Surviving post-communism. Young people in the former Soviet Union. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar.

Roche, Jeremy; Tucker, Stanley; Thomson, Rachel & Flynn, Ronny (2007). Youth in society. London: Sage.

Rudolph, Martin (1997). Unterschiede auf dem Land. Landjugendliche in Ost- und Westdeutschland. Berichte über Landwirtschaft, 75, 486-497.

Schäfer, Nadine (2007). "I mean, it depends on me in the end, doesn't it?" Young people's perspectives on their daily life and future prospects in rural east-Germany. In Ruth Panelli, Samantha Punch & Elsbeth Robson (Eds.), Global perspectives on rural childhood and youth (pp.121-134). New York: Routledge.

Schäfer, Nadine (2008). Young people's geographies in rural post-socialist Germany: A case study in Mecklenburg-Vorpommern. Unpublished PhD Thesis, University of Plymouth.

Schlottmann, Antje (2005). RaumSprache – Ost-West-Differenzen in der Berichterstattung zur deutschen Einheit. Eine sozialgeographische Theorie. Stuttgart: Franz Steiner Verlag.

Sharland, Elaine (2006). Young people, risk taking and risk making: Some thoughts for social work. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung / Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 7(1), Art. 23, http://nbn-resolving.de/urn:nbn:de:0114-fqs0601230.

Shucksmith, Mark (2004). Young people and social exclusion in rural areas. Sociologia Ruralis, 44(1), 43-59.

Smith, Fiona (1998). Between East and West. Sites of resistance in east German youth cultures. In Tracey Skelton & Gill Valentine (Eds.), Cool places. Geographies of youth cultures (pp.289-304). London and New York: Routledge.

Statistisches Landesamt Mecklenburg-Vorpommern (2003). Statistisches Jahrbuch Mecklenburg-Vorpommern 2003. Schwerin: Statistisches Landesamt Mecklenburg-Vorpommern.

Statistisches Landesamt Mecklenburg-Vorpommern (2005). Zahlenspiegel Mecklenburg-Vorpommern. Landesdaten ausgewählte Kreisdaten. Schwerin: Statistisches Landesamt Mecklenburg-Vorpommern.

Stenning, Alison (2005). Post-socialism and the changing geographies of the everyday in Poland. Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers, 30(1), 113-127.

Strauss, Anselm & Corbin, Juliet (1998). Basics of qualitative research. Techniques and procedures of developing grounded theory. London: Sage.

Tulloch, John & Lupton, Deborah (2003). Risk and everyday life. London: Sage.

Valentine, Gill (2003). Boundary crossings: Transitions from childhood to adulthood. Children's Geographies, 1(1), 37-52.

van Hoven, Bettina (2001). Women at work—experiences and identity in rural East Germany. Area, 33(1), 38-46.

Walkerdine, Valerie (2003). Reclassifying upward mobility: Femininity and the neoliberal subject. Gender and Education, 15(3), 237.

Werz, Nikolaus (2001). Abwanderung aus den neuen Bundesländern von 1989 bis 2000. Aus Politik und Zeitgeschichte B, 39-40, 23-31.

Woods, Michael (2007). Engaging the global countryside: Globalization, hybridity and the reconstitution of rural place. Progress in Human Geography, 31(4), 485-507.

Wyness, Michael (2006). Childhood and society. An introduction to the sociology of childhood. Basingstoke: Palgrave.

Young, Craig & Light, Duncan (2001). Place, national identity and post-socialist transformations: An introduction. Political Geography, 20(8), 941-955.

Zinnecker, Jürgen; Behnke, Imbke; Maschke, Sabine & Stecher, Ludwig (2002). Null zoff & voll busy. Die erste Jugendgeneration des neuen Jahrhunderts. Ein Selbstbild. Opladen: Leske+Budrich.

Nadine SCHÄFER has been working on young people's everyday lives and their identity construction in second modernity. Further research interests include: children's geographies, gender relations, transformation processes in post socialist countries and participatory research approaches. Nadine is a lecturer in the Graduate School of Education/University of Exeter.

Contact:

Nadine D. Schäfer

Graduate School of Education

University of Exeter, St. Luke's Campus

Heavitree Road, Exeter EX12LU

United Kingdom

Tel.: 0044 1392 724768

E-mail: n.d.schaefer@exeter.ac.uk

Schäfer, Nadine (2010). The Spatial Dimension of Risk: Young People's Perceptions of the Risks and Uncertainties of Growing Up in Rural East Germany [56 paragraphs]. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung / Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 11(1), Art. 5, http://nbn-resolving.de/urn:nbn:de:0114-fqs100159.

Revised: 7/2010