Volume 12, No. 1, Art. 36 – January 2011

Learning to Use Visual Methodologies in Our Research: A Dialogue Between Two Researchers

Nick Emmel & Andrew Clark

Abstract: In this paper we discuss learning about using visual methodologies in a research project exploring social networks, neighbourhood spaces and community in an inner city-area of a British northern city. We draw on the substantive and methodological experiences of visual researchers and provide an account of the ways in which we discussed, developed, and reflected on the value and possibilities of visual methods in our data collection and analysis. We present the paper as a dialogue to represent how, as a research team, we engaged in an on-going iterative engagement with the visual methods we used. Our dialogue considers visual data we collected through a walkaround method, focusing on how these data contributed to our understanding of the field, data analysis, the refinement of research questions, and theoretical development in the research.

Key words: visual methods; qualitative; walkarounds; dialogue

Table of Contents

1. Introduction

2. The Research, the Fieldsite, and a Walk

3. Learning to Use Visual Methods

4. Conclusion

"Every image embodies a way of seeing. Even a photograph" (BERGER, 1972, p.10)

There has recently been something of a visual turn in the social sciences (PAUWELS, 2000) where, alongside analysis of visual material culture, there is increasing use of visual methods in empirically-grounded research (BANKS, 2001; COLLIER & COLLIER, 1986; PROSSER, 1998). The growth in interest in visual methods may be related to increasingly inexpensive and accessible technologies to record and disseminate the still and moving image (KNOBLAUCH, BAER, LAURIER, PETSCHKE & SCHNETTLER, 2008). It may also reflect a heightened awareness of the appropriateness of visual method as a means of documenting and representing the social world, where visual methods are being used in creative ways to develop new ways of understanding individuals and social relationships, and social science knowledge itself (PINK, 2007; ROSE, 2001). In addition, the methodological insights provided by researchers' experiences of applying visual methods are evident in growing numbers of papers delivered at conferences, workshops and training events (e.g. ESRC, 2009). [1]

In this paper we discuss how we developed and applied visual methods for the first time in our research. Our discussion draws on the substantive and methodological experiences of visual researchers from across social science disciplines. It also provides an account of the ways in which we played with, discussed, and reflected on the value and possibilities of visual methods in our data collection and analysis in a reflective process that sought to alert us to the possibilities and limitations of these methods. [2]

We present the paper as a dialogue in response to calls to develop alternative ways of writing about and representing experiences of, and findings from, social science research (LATHAM, 2003; LEUNG & LAPUM, 2005; MULKAY, 1985; WYNNE, 1988). As CHAPLIN notes, postpositivist aspirations to "liberate authors from academic constraints" (1994, p.247) have been used to justify new literary forms in sociological analysis and writing. Here, we adopt a dialogic style to representing how our different ideas became enmeshed in the research endeavour, reflect on the different literatures we have been thinking about, and to demonstrate ways in which research projects develop in iterative, fluid, and often unexpected ways. Our intention is to reflect, albeit partially, the debates, agreements and disagreements, along the intellectual road we travelled and in doing so, provide some indication of the ways in which a visual method might be reworked throughout the research process. Our dialogue relies heavily on our individual field diaries that we kept throughout the research process and from which we selectively drew important lessons we had learnt about using visual methods in the research. This dialogue has been re-worked following feedback from various research meetings and seminars (CLARK & EMMEL, 2008). [3]

The linearity of the research process provides a structure for the paper and we map the chronological development of the research, starting with our entry into the research fieldsite. Our reflections consider how we moved from early understandings through more sophisticated interpretations as the research progressed and the role visual methods played in forming these insights. We focus on how we learnt to use visual methods in this research. But before turning to this dialogue we briefly describe the research site and the method we used, a walkaround method, in this investigation of networks, neighbourhood space, and communities. [4]

2. The Research, the Fieldsite, and a Walk

Our research is an investigation of networks, neighbourhood spaces, and communities using a multi-method approach including participatory social mapping interviews, diary-interviews and walking interviews (EMMEL & CLARK , 2009). The research is situated in one geographical location or fieldsite. Periodically we walked through this field along a set pathway taking photographs. It is these fieldsite walkarounds and the challenges of using visual methods to document the field, that we report here. The research is conducted in a geographical place covering around 1.5 mile2 (circa 2.5 km2) with a mixed population. Relatively affluent students live in close proximity to one of the most deprived populations in England. There is a relatively large ethnic minority population, established families who have brought up two or three generations in the area, and a significant, somewhat transitory population of young urban professionals mostly living in rented accommodation. Within this socially heterogeneous geographical context our research explores, among other aims, the ways different social groups create, maintain, dissemble and experience, social networks over time and across space. [5]

We both have experience of conducting research in the urban built environment and in previous, separate, research we have also walked our research sites in order to try to understand further the locations within which we are doing research (EMMEL & SOUSSAN, 2001; CLARK, 2009). We tended to do this for five reasons: First, to identify and recognise difference, particularly in the built environment; second, to consider the impact of the environment on those who live in the place; third, to look for ways in which the built environment might be experienced by those who live there; fourth, to look for evidence of the ways in which public and other services are delivered in these places; and finally, to explore how the places we are researching within might change over time. [6]

In our current research, we recognised the possibilities of formalising walks through and around our fieldsite as a more rigorous visual method. What can we learn by walking through the field? Can walking through the field help us recognise stability and flux? How can we record what we are observing and the interpretations we make as we walk through the field? Do these walkarounds offer any analytical and theoretical insights? And can photographing the field provide any insight beyond visual descriptions of where we are doing our research? [7]

The first time we walked the fieldsite we set out with no fixed plan of where or for how long we would walk. Although we had no formal training in either photography or visual research methods, we decided to take photographs of the field as we walked. Like many researchers, we have both previously taken photographs of our research sites in a somewhat ad hoc manner. In our field notes, Nick notes:

"Andrew and I go for a wander around [fieldsite]. We have a (digital) camera and we are just taking photos of what interests us in the built environment ..." [8]

The route we walk is about 2.5 miles (circa 4km) in length, meanders through the fieldsite and takes around three hours to complete. We have repeated the walk every three months for over two years and have now done ten walkarounds. We walk through a predominantly residential area where streets of 19th century terraced properties and large 19th century mansion houses that have converted into apartments are interspersed with more recent inter-war semi-detached houses, purpose built low-rise flats, and small post-war social housing estates. Periodically, residences are broken by institutional buildings; places of worship or education, parkland and shorter rows of commercial properties; mostly fast-food takeaways, grocery stores, property agents, and an occasional public house or café. We always walk the same route, and try to walk at the same time of day. The route captures the diversity we saw in the built environment. Our decision to walk at the same time of day was practical, to ensure we would walk in daylight throughout the year. It was also informed by our concern to explore how the place might change over time. We presupposed that similar kinds of activities will happen at a similar time of day. We stop the walk at a café about half way through, where we discuss what we are taking photographs of and what we have noticed as we walk. Towards the end of the walk we cross our outgoing path, turn the cameras off, walk across a park and talk about what we have learnt from this trip through the field. Both of us write up individual ethnographic field notes immediately afterwards in field diaries that we subsequently share. The following dialogue focuses on what we have learnt from this method and outlines our reflections on the significance of visual methods in field-based research. [9]

3. Learning to Use Visual Methods

Nick: When we first started doing the walks we were, I think, quite clear about why we walk our research sites given our backgrounds in researching urban places. I decided to take a camera and take photographs whilst we were walking. I remember being unsure as to why I was taking the photographs. I wrote in my research diary, half-joking, that this was a method in search of a research question! You didn't have a camera on that walk so I sent you the photographs I had taken. Three months later I did another walkaround. I sent you the photographs from this walk too. When you came to [site of research] to start work on the project I suggested we do the walk again. Why did you think it would be worthwhile doing the walk? [10]

Andrew: As a field researcher, walking the field is something I just do. Like most researchers, I have been trained that if you really want to understand a place you have to go and see it for yourself. [11]

I was keen to walk the same route to re-familiarise myself with the field; it's easier to refresh your memory when you are in the setting you are trying to remember or reflect upon. I wanted to take photographs because I wanted to keep a record of the field, or at least parts of it. Perhaps I wanted to try to capture the field for posterity. I remember we discussed whether we should video-record our walks. We eventually deciding not to because of the complexities of what to record, where to "zoom in", and ultimately, what we would do with the films we would produce. On reflection, perhaps we were both nervous that seeing the world through the lens of a video camera, and the implications of producing, as PINK puts it, not so much "realist representations, but expressive performances of the everyday" (2003, p.55). [12]

Of course, this does not mean that looking through the lens of still or digital camera is any more "real", or less "performative", and nor does it eradicate the negotiation of what to photograph and why. For me, this decision making changed as the research progressed. For instance, initially I hoped that I would be able to compare the photographs with the records from earlier walkarounds and perhaps even archive material, to see how the site changed through shorter and longer periods of time, and especially if I took photographs from the same vantage points (RIEGER, 1996; SMITH, 2007). I think it is fair to say my approach to visual data has changed substantially since then, but before we talk about that, I am interested to know about the sorts of data you believed you were collecting. [13]

Nick: I agree with your idea of familiarising ourselves with the field as something we just do. In the past that process did include visual data, but these were sketches and the occasional photograph taken with a 35mm camera that accompanied the written descriptions I recorded in my field notes. This time it was different, we chose to use a camera to collect data. Like in all my earlier research of place I was faced with the same intellectual problem—places are not as easy to understand as we first assume. As an example, in my earlier research in slums in Mumbai (EMMEL & SOUSSAN, 2001) sketching how a water supply is distributed through a slum suggests something about the social relationships that brought about its design. These sketches were the start of an investigation of these relationships. Similarly, taking photographs I have a record of the place I was walking through created in a new way. [14]

However, unlike you, my concern was not to take photographs from the same vantage point but to try and take images that supplement questions I wanted to know the answer to in the research. RIEGER (1996, p.5) notes that "visual change and social change are generally related, and we can often draw useful insights about what is happening within the social structure from a careful analysis of visual evidence". [15]

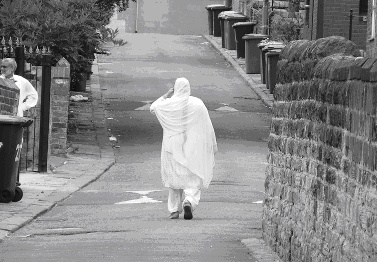

Figure 1 is an example of the kind of data I thought I was trying to collect. At the time, we were seeking to understand the ethnic make-up of the area. This photograph is part of that understanding. But there is more. The railings—so typical of some of the houses in the area—are perhaps an indicator or who lives in these houses. The rubbish bins lined up on the street, the rubbish lying in the road, the traffic calming measure all lead to further insights in getting to know and understand the area.

Figure 1: A back street in the fieldsite [16]

These photographs have documentary value. I am able to linger over the images and identify key indicators that are important to understanding the place. What strikes me, however, as I review these images much later, once we have started to understand this place better through other methods—participatory mapping, walking interviews, and field diaries (EMMEL & CLARK, 2009)—is that the way I understand this place through the images is rather different to the ways in which those who live there understand it and the way I understand it as a researcher. PINK (2007, p.32) describes this as a "rupture between visibility and reality". These images record visible phenomena. Reality cannot be fully represented visually. We need to do more to understand the place we are walking through. So in response to your question, my answer is material visual signifiers of the area that provide a partial account of the place we were investigating. [17]

Andrew: Looking back on my own stacks of photographs, I seem to take two types of image. One is a kind of macro-scale or panoramic view that captures the moment. The others are more micro in scale and try to document what I saw as the key issues for the field. [18]

The panoramic views were an attempt to represent the whole of the field in a single image or set of images (Figure 2). In a way, they represent a rather naïve approach to photographic methods and an attempt to fix the field. I think these images are not dissimilar to tourist snaps: something to show people—colleagues, students and conference delegates for instance, where I had been and what I had seen. They hint at attempts to present an overview of the field site that, in many ways, produce a view from above or outside, in the same way that other researchers have sought to produce a "typical" image of place from a particular, usually lofty, vantage point (CROW, 2000).

Figure 2: A main street in the fieldsite [19]

The second set of images was taken close up. These document some of the key issues in the area. During our first walk these were students, rubbish, and traffic—three features that seemed to be ubiquitous. On reflection, I'm not sure why I took pictures of students, rubbish and traffic; maybe I thought they would stand in as proof for what I saw. With hindsight, I approached the camera a little like some approach voice recording equipment, as a tool to uncritically capture the social world. [20]

As I have become more familiar with the field and with visual methods, I am surprised that I still seem to be taking these same types of images: I continue to produce panoramic and key issue photographs. However, rather than capturing the moment, my panoramic photographs now represent ideas to follow up. For example, Figure 3 contains a great deal of data: This patch of supposedly vacant waste ground is the boundary of a physical redevelopment scheme that was suspended in the late 1970s. For recent residents, it is an area where building materials and rubbish is sometimes dumped. For others, who have lived in the area for many years, this is also the site of a public house that was destroyed in disturbances between local residents and police some 12 years previous and which has withstood the threat of redevelopment, partly because of a strong local stewardship towards the historical and social significance of the land. Consequently, while the photographs I have taken remain the same visually, how we read these images and ultimately understand their content clearly changes as our knowledge of the place is enhanced through other methods.

Figure 3: Waste ground at the fieldsite [21]

More than this, and as this example highlights, the photograph is a valuable tool for researcher-elicitation. It is a mnemonic device that reminds me to follow up particular stories. I work with these images alongside other methods, including interviews, to add a further layer to my knowledge of the area. My view of photographing the field has changed from a somewhat positivist belief in them being static data or "proof" about the field to become part of my interrogation and interpretation of the data. In a way then, I am using photographs as elicitation devices to probe deeper into my own understanding of the field in much the same way as I might use photo-elicitation with participants (EPSTEIN, STEVENS, McKEEVER & BARUCHEL), 2006; HARPER, 2002). [22]

That is one way in which my attitude to the use of photographs has changed because of this method. But I am interested in the idea of partiality in visual data. Is the partiality of the image a problem? And what can we do about it? Or is it enough to just say we can never represent reality completely? [23]

Nick: Your ideas about why you take a photograph are, I think, reflected in aspects of the history of objectivity (DATSON & GALISON, 2007). These authors trace the emergence of a mechanical objectivity associated with instruments like the daguerreotype and camera to record images uncontaminated by interpretation, and go on to note that "photographic vision has become a primary metaphor for objective truth" (p.197). In part, your early thinking about why you were taking photographs on the walkaround has elements of this objectivity in it. However, as time goes by the photographs take on a new purpose, which is akin to a more recent understanding of objectivity as familiarity, expertise and "trained judgment" (p.322). [24]

We each use the photographs we take on the walk as an adjunct to the other methods we are using in the research. In addition, of course, we are spending a considerable amount of time immersing ourselves in the field and in getting to know it. Through this immersion we gain a considerable stock of knowledge about how the place is now and also a deeper understanding of its history. You suggest that the photographs you are taking are a mnemonic device to remind you of particular issues, events, and understandings of this place. I think this is an important feature of the photographs we take. As I read our field notes, research diaries, and the transcripts from the other methods I am reminded of photographs I have taken on the walk. Now I take photographs that are informed by what I am learning as I analyse the data in the research. But, like you, I think the photographs we take are more than just mnemonic devices. They contribute to and facilitate an interpretation of place, which in turn provides a more complete account of the place and space in which we are doing research. [25]

That the image is only a partial account is emphasised on the walk. An image cannot capture sounds, smells, nor touch for instance. All of these have become important to me as I walk. There are areas that are quiet and peaceful and there are areas that are noisy with traffic and hustle and bustle. There are places that have particular and evocative smells. There are parts where the terrain is flat and smooth, and parts where it is rough and steep, all of which is important in trying to understand the place. These observations are recorded in my field-notes though they are rather harder to document visually. [26]

You are right though, to say that we have learnt that an image does not capture reality. Still, photographs are another source of insight, like, for instance, the statistical indicators we have compiled (CLARK, 2008), and, of course, the data we are collecting using the other methods (EMMEL & CLARK, 2009). Like all these data, photographs sharpen our senses. Looking through the viewfinder of my camera has made me much more aware of the visual. Reviewing photographs, invariably on my computer screen, mean that what was once a passing glance is now planned, framed, composed, and given meaning in the pressing of the shutter (GRADY, 2009). The photograph, once taken, adds to the many modes of data recorded in various media to be used in our analysis. If, as I assert, the collection of multi-modal data has the potential to deepen our sociological understanding then we are faced with the challenge of how to analyse this visual data alongside all the other modes of data. How have you gone about doing this? [27]

Andrew: Analysis of researcher produced visual data creates a different set of analytical problems to that created by participants. Although there is instructional literature available to explain how to analyse and interpret visual material that has not been generated by the researcher (e.g. ROSE, 2001), these techniques are less appropriate here. I am also not sure that techniques for analysing text-based data (e.g. FEREDAY & MUIR-COCHRANE, 2006; GRBICH, 2007; SRIVASTAVA & HOPWOOD, 2009) are entirely appropriate. This is not necessary because visual data is different in form and content but because, in our case the researcher is the participant as we go about documenting the field. This makes common visual analytic processes, such as semiotic analysis or thematic analysis through photo-elicitation, difficult because any analysis begins at the same time as the data is generated. So, although as with much textual and other forms of visual data, analysis was a "series of inductive and formative acts carried out throughout the research process" (PROSSER & SCHWARTZ, 1998, p.125, my emphasis); mapping this process is quite complex. [28]

We have talked about the photographs as mnemonic devices, facilitating interpretation, and an attempt to frame (and, to a degree, fix) the field site. All these approaches form part of the analysis process. As mnemonic devices my photographs worked as prompts for different questions to be asked of participants and existing data. As framed representations of the field site, the images are better approached not as a photographic record to be reviewed and analysed, but rather as part of my reflexive engagement with the way we construct knowledge about the field (BURGESS, 1984; LAREAU & SHULTZ, 1996). Hence the photographs document my changing relationship with this knowledge and facilitate the process of trained judgement to understand the field rather than standing alone to provide any objective portrayal of it. For the purposes of analysis, the photographs have come to serve as a tangible aspect of a sensual method capable of evoking past experiences. These evocations are used to ask new questions of data collected through different methods. [29]

Figure 4 is an example about how this analytical process happens. The panorama could be analysed at face value as an empty play area; perhaps supporting ideas about the out-migration of families (a common theme discussed by some resident groups). This remains an interpretation based on my own reading of the landscape, and information collected during participant observation of local residents' meetings. Subsequent questioning about play spaces in the area however, reveals a range of alternative explanations for under-use. For example, conversational interviews with young people reveal a more nuanced geography of play and socialisation in the area; informal discussion with a local official suggest infrastructural problems with this particular space, while analysis of the recent history of this play space hints at a more political explanation for its existence and apparent under-use. This means that I do not analyse the images alone (that is, as a discrete data set); but rather alongside other methods. I verify my interpretations (that lie behind the comprehension of the image) with those of others; and vice versa, interrogating the interpretations of participants with my own experiences. Finally, beyond either interrogation or triangulation, I use the walkaround method as a way of formulating new questions to ask of participants in the other methods. In some respects, it is the making of the photograph (deciding whether, and what, to photograph and why), rather than the image itself, that is more analytically revealing.

Figure 4: A playground in the fieldsite [30]

We have already discussed how the walkabout method for me represents the way in which we do qualitative and ethnographic field research, and we have both remarked upon how we have always been enthusiastic about photographing our research sites. This method has encouraged me to think more deeply about why I engage in such practices. In the past, I have tended to consider photographs as illustrative of the sorts of things I am seeing in and understanding about the field; I suppose as "snapshots" of life. I am now much more aware of the processes behind producing and analysing such images. [31]

While research questions inform what data we generate, that data in turn informs the questions we ask, and this includes visual data. So, rather than performing content or thematic analysis on the images and on any accompanying textual or verbal elicitations, the images exist as tangible representations of the iterative process of data creation (my attempt to document the field through the production of an image) and analysis (my attempt to represent what I am experiencing through the production of a meaningful image). For me, the images are re-analysed not for their meaning, but for their potential meaning depending on particular interpretations. Because it is hard to elicit my own interpretation of the image after it has been produced, I instead analyse different interpretations of the image; verifying such interpretations through interrogation of the images triangulated with data collected through other methods. [32]

Nick: The point you make is also made by EMMISON and SMITH (2000, p.2) and DICKS, SOYINKA and COFFEY (2006, p.79), who argue that:

"... photographs have been misunderstood as constituting forms of data in their own right when in fact they should be considered in the first instance as means of preserving, storing, or representing information. In this sense photographs should be seen as analogous to code-sheets, the response to interview schedules, ethnographic field notes, tape recordings, verbal interactions or any one of the numerous ways in which the social researcher seek to capture data for subsequent analysis and investigation." [33]

However, I think we have to see the photographs we take on the walks as more than code sheets that inform other aspects of our research. Earlier I suggested that photographs act as material visual signifiers of the place we are seeking to investigate. I want to go further. EMMISON and SMITH (2000, p.68) argue each of these signifiers is an index, which has "a direct connection with the thing it represents" or better, is part of something, in this case a part of the place, something that is typical of the place, that "stands for the whole", a synecdoche. So, for instance, I can group many photographs taken from a walkaround into piles that represent particular places in the geographically bounded place we are investigating—the park, its pedestrians, leisure, and art; the corner, its advertising hoardings, eateries, and traffic; The mixed residential streets where students live alongside long-term residents, the posters advertising concerts and local music bands, the football shirts for the local team hanging on the washing line; The predominantly "locals" area with the community centre, estate agents' for-sale signs, where children are playing in the street; and so on. The photographs encourage reflection, categorisation, and interpretation of the geographical place we are investigating. We may conclude that this place is not homogeneous but is a rich matrix of many neighbourhoods existing in one geographic space, whose particular characteristics can be seen and are represented in the photographs we collect on the walkaround. [34]

This first level of analysis is categorising and searching for patterns. The visual data thus categorised becomes modal (that is typical characteristics) that represent particular places, events, and scenes within the geographical place. And having done this inductive and formative exercise using the photographs, further data collection and analysis is needed; indeed subsequent walks lead to the collection of more visual data. But, in contrast to our earlier forays into the field, the photographs I now take are fewer and are planned. On the last walkaround, for instance, I took photographs of the ways people walk through the area. This was based on the insights from the other methods, including the walking interview in which we have observed that people take specific routes and walk in particular ways through this place. Our gaze is sharpened by what we learn in the inductive approach to data collection in many modes. [35]

Our learning about visual methods has moved from "fixing the landscape", through concerns about what we learn from an image and how much we "capture the social world". The choices about the photographs we take are purposive in relationship to what we are learning using other methods, our analysis of these data, and the theoretical insights we are gaining into networks, neighbourhood spaces and communities. We recognise the partiality of photographs and the threats to their validity. Photographs do not, as the popular aphorism goes, say a thousand words. As we have discussed these data collection exercises and analyses require more than the visual images to address our research questions. We draw on all the other modes we record in our analysis. By modes I mean "the abstract, non-material resources of meaning-making. The obvious modes include writing, speech and images; less obvious ones include gesture, facial expression, texture, size and shape, even color" (DICKS et al., 2006, p.82). As I have mentioned sound, smell, and touch were also important. Our contention is that visual representation, alongside the many other data we collect are used in exercises of triangulation in which multiple perspectives as well as multiple data are brought to bear through critical evaluation on their validity (HAMMERSLEY, 2008; DENZIN, 1989) and contribute to the development of sociological insight, argument, and theorization that we, as a research team, have arrived at. [36]

Our intellectual journey to understand the visual is not over. Yet it is this journey thus far that we have sought to report and reflect on here. We are experienced researchers of place and no longer neophyte visual researchers. A desire to understand place is important to both of us, for place provides the material expression of networks, neighbourhood spaces, and communities we seek to understand. [37]

The visual is one more mode to add to all the modes we have traditionally used in seeking to understand place. Of course the visual has always been part of our understanding of place, but in these walks we have had the opportunity to formalise the visual as simultaneously, data, method, and analysis in our research and reflect on what we have learnt from it. [38]

While photographs form the basis of our visual data, they offer more than just information about what we observe in our field site. They allow us to map our reflexive engagement with the research field. They are a kind of visual research diary, offering clues to how we respond to the field over the course of research. They sharpen our gaze through framing the field in the viewfinder. Furthermore, they stimulate an awareness that we are in the act of generating data, for and through using a camera we have been encouraged to think about the role of research equipment in the field. While qualitative researchers are now familiar with collecting data using a sound recorder, taking a camera into the field allows us to re-engage with the role such equipment plays in the production of data through which we understand the social world. [39]

Our photographs are not just snapshots of life in the field site, or pieces of data to be analysed as some kind of objective truth. We are not in the act of producing a visual ethnography where photographs play the central role in our representation of the field. Rather, the images we take facilitate hunches, ideas, and theories to help answer particular research questions. Our growing familiarity with the field, while not necessarily apparent in our piles of photographs, is evident in our increasingly complex interpretations accompanying each image. For photographs do not just offer a way of representing social life, but also, through organising, sorting and categorising images, make it possible to begin to understand these representations more clearly. Furthermore, the photographs act as a mnemonic aid to stimulate particular interpretations. They also facilitate our trained judgment of the field site that we now know so well, enabling us to navigate back and forth between the other stories we hear in the research and encourage a more complete understanding of the field. Photographs are a record of what we saw in the field, but their meaning evolves. The strength of this reflexive account with visual methods is also its potential weakness. The paradox lies in the epigraph with which we started this paper. Every image does embody a way of seeing (BERGER, 1972) but this embodiment is not deterministic, but relational. Of course, researchers (and particularly ethnographers) have long used photographs to record and represent the field. We argue that those practices of recording and representing are rooted in, and responsive to, reflexive engagements with different modes of data collection and the knowledge they produce. Moreover, the knowledge embodied in the production and analysis of a photograph changes with reference to the other ways of seeing, hearing, writing, and recording in the research that we mobilise towards answering our research questions. The challenges we face then, lie not only in deciding what to photograph, or in choosing which images to include in research outputs, but also in how to incorporate relational accounts of the production and, crucially, analysis, of visual data without necessarily reducing it to relativism. Through using visual methods we have learnt that photographs are another mode that facilitates our sociological theorisation of place in our pursuit of a more adequate understanding of networks, neighbourhood spaces, and communities. However, they are not a panacea but must be treated with the same critical methodological approach that we would apply to any method of data collection in our qualitative research. [40]

This paper reports on research funded by the Economic and Social Research Council (ref 576255017). "Connected Lives" is part of the Manchester/Leeds Real Life Methods Node of the National Centre for Research Methods.

Banks, Marcus (2001). Visual methods in social research. London: Sage.

Berger, John (1972). Ways of seeing. London: Penguin.

Burgess, Robert (1984). In the field: An introduction to field research. London: Routledge.

Chaplin, Elizabeth (1994). Sociology and visual representation. London: Routledge.

Clark, Andrew (2008). An overview of Hyde Park and Burley Road, Leeds, http://www.reallifemethods.ac.uk/research/connected/ [Accessed: January 4, 2011].

Clark, Andrew (2009). Experiences of moving through stigmatised neighbourhoods. Population, Space and Place, 15(6), 523-533.

Clark, Andrew & Emmel, Nick (2008). Reflections on methodologies to understand community. Presented at the Annual Meeting of the ESRC National Centre for Research Methods, Bristol, UK, 10-11th January.

Collier, John. Jr. & Collier, Malcolm (1986). Visual anthropology: photography as a research method. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press.

Crow, Graham (2000). Developing sociological arguments through community studies. International Journal of Social Research Methodology, 3(3), 173-187.

Daston, Lorraine & Galison, Peter (2007). Objectivity. New York: Zone Books.

Denzin, Norman (1989). The research act. A theoretical introduction to sociological methods. London: Prentice Hall.

Dicks, Bella; Soyinka, Bambo & Coffey, Amanda (2006). Multimodal ethnography. Qualitative Research, 6(1), 77-96.

Economic and Social Research Council (ESRC) (2009). Researcher development initiative: Building capacity in visual methods. Grant holder: Jon Prosser, http://www.rdi.ac.uk/projects/round2/28.php [Accessed: March 30, 2010].

Emmel, Nick & Clark, Andrew (2009). The methods used in "Connected Lives": Investigating networks, neighbourhoods, and communities. ESRC National Centre for Research Methods, NCRM Working Paper Series 6/09, http://eprints.ncrm.ac.uk/800/ [Accessed: January 4, 2011].

Emmel, Nick & Soussan, John (2001). Interpreting environmental degradation and development in the slums of Mumbai. Land Degradation and Development, 12, 277-283.

Emmison, Michael & Smith, Philip (2000). Researching the visual. London: Sage.

Epstein, Iris; Stevens, Bonnie; McKeever, Patricia & Baruchel, Sylvain (2006). Photo elicitation interview (PEI): Using photos to elicit children's perspectives. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 5(3), Art. 1, http://www.ualberta.ca/~iiqm/backissues/5_3/pdf/ epstein.pdf [Accessed: January 22, 2011].

Fereday, Jennifer & Muir-Cochrane, Eimear (2006). Demonstrating rigour using thematic analysis: A hybrid approach of inductive and deductive coding and theme development, International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 5(1), 80-92.

Grady, John (2009). Visual research at the crossroads. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung / Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 9(3), Art. 38, http://nbn-resolving.de/urn:nbn:de:0114-fqs0803384 [Accessed: December 10, 2010].

Grbich, Carol (2007). Qualitative data analysis: An introduction. London: Sage.

Hammersley, Martyn (2008). Questioning qualitative enquiry: Critical essays. London: Sage.

Harper, Douglas (2002). Talking about pictures: A case for photo elicitation. Visual Studies, 17, 13-26.

Knoblauch, Hubert; Baer, Alejandro; Laurier, Eric; Petschke, Sabine & Schnettler, Bernt (2008) Visual analysis. New developments in the interpretation and analysis of video and photography. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung / Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 9(3), Art. 14, http://nbn-resolving.de/urn:nbn:de:0114-fqs0803148 [Accessed: December 10, 2010 ].

Lareau, Annette & Shultz, Jeffrey (1996). Journeys through ethnography: Realistic accounts of fieldwork. Boulder, CO: Westview Press.

Latham, Alan (2003). Research, performance, and doing human geography: Some reflections on the diary-photograph, diary-interview method. Environment and Planning A, 35(11), 1993-2017.

Leung, Doris & Lapum, Jennifer (2005). A poetical journey: The evolution of a research question. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 4(3), 63-82, http://ejournals.library.ualberta.ca/index.php/IJQM/article/view/4441/3781 [Accessed: December 10, 2010 ].

Mulkay, Michael (1985). Talking together: An analytical dialogue. In Michael Mulkay, The word in the world: Explorations in the form of sociological analysis (pp.103-129). London: Allen & Unwin.

Pauwels, Luc (2000). Taking the visual turn in research and scholarly communication: Key issues in developing a more visually literate (social) science. Visual Studies, 15(1), 7-14.

Pink, Sarah (2003). Representing the sensory home: Ethnographic experience and ethnographic hypermedia. Social Analysis, 47(3), 46-63.

Pink, Sarah (2007). Doing visual ethnography. London: Sage.

Prosser, Jon (Ed.) (1998). Image-based research: A sourcebook for qualitative researchers. London: Falmer Press.

Prosser, Jon & Schwartz, Dona (1998). Photographs within the sociological research process. In Jon Prosser (Ed.), Image-based research: A sourcebook for qualitative researchers (pp.115-130). London: Falmer Press.

Rieger, Jon (1996). Photographing social change. Visual Sociology, 11(1), 5-49.

Rose, Gillian (2001). Visual methodologies: A guide to the interpretation of visual materials. London: Sage.

Smith, Trudi (2007). Repeat photography as a method in visual anthropology. Visual Anthropology, 20, 179-200.

Srivastava, Prachi & Hopwood, Nick (2009). A practical framework for qualitative data analysis. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 8(1), 76-84, http://ejournals.library.ualberta.ca/index.php/IJQM/article/view/1169/5199 [Accessed: January 22, 2011].

Wynne, Andy (1988). Accounting for accounts of multiple sclerosis. In Steve Woolgar (Ed.), Knowledge and reflexivity: New frontiers in the sociology of knowledge (pp.101-122). London: Sage.

Nick EMMEL is senior lecturer in sociology and social policy at the University of Leeds, UK. His substantive research interests include inequality and the experiences of poverty in place. At the moment Nick is writing a book on sampling and choosing cases in qualitative research for Sage.

Contact:

Nick Emmel, PhD.

School of Sociology and Social Policy

University of Leeds

Leeds

LS2 9JT, UK

E-mail: n.d.emmel@leeds.ac.uk

Andrew CLARK is lecturer in sociology at the University of Salford. His research interests focus on urban space, and predominantly on neighbourhood and community change.

Contact:

Andrew Clark, PhD.

School of English, Sociology, Politics and Contemporary History

University of Salford

Salford

Greater Manchester

M5 4WT, UK

E-mail: a.clark@salford.ac.uk

Emmel, Nick & Clark, Andrew (2011). Learning to Use Visual Methodologies in Our Research: A Dialogue Between Two Researchers [40 paragraphs]. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung / Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 12(1), Art. 36, http://nbn-resolving.de/urn:nbn:de:0114-fqs1101360.