Volume 12, No. 2, Art. 6 – May 2011

Photographic Portraits: Narrative and Memory

Brian Roberts

Abstract: This article is a more general "companion" to the subsequent, Brian ROBERTS (2011) "Interpreting Photographic Portraits: Autobiography, Time Perspectives and Two School Photographs". The article seeks to add to the growing awareness of the importance of visual materials and methods in qualitative social research and to give an introduction to the "photographic self image"—self-portraits and portraits. It focuses on time and memory, including the experiential associations (in consciousness and the senses) that the self engenders, thus linking the "visual" (photographic) and "auto/biographical".

The article attempts to "map" a field—the use of portraiture within social science—drawing on narrative and biographical research, on one side, and photographic portraiture, on the other. In supporting the use of photography in qualitative research it points to the need for researchers to have a greater knowledge of photographic (and art) criticism and cognisance of photographic practices. The article does not intend to give a definitive account of photographic portraiture or prescribe in detail how it may be used within social science. It is an initial overview of the development and issues within the area of photographic portraiture and an exploration of relevant methodological issues when images of individuals are employed within social science—so that "portraiture" is better understood and developed within biographical and narrative research.

Key words: portrait; self-portrait; photographic self-image; narrative; time perspectives; memory; recurrence

Table of Contents

1. Overview

2. Photographs in Current Biographical/Narrative Social Research

3. Social Documentary Photography and Photographic Portraiture

4. The Photograph and Reality

5. The Photograph: The Mirror, the Screen ...

6. Photographic Self-Images: Portraits and Self-Portraits

7. Narratives and the Photographic Self-Image

8. Narratives: Visual and Written Text Materials

9. On Looking and Re-Looking at Photographs—Memory and Recurrence

9.1 Photographic self-images and recurrence

9.1.1 Spontaneous recurrence

9.1.2 Remembering as recurrence

9.1.3 Return as recurrence

10. Conclusion: Responses to Photographic Portraits

11. Epilogue: The Use of Photographic Portraits in Research

Illustration 1: The practice of photography—self-portrait, 2009 (B. ROBERTS, 2011)1) [1]

The article begins, in Section 2—"Photographs in Current Biographical/Narrative Research"—with an outline of the past and present use of visual materials in the social sciences. It notes the increasing and diverse use of photographs in narrative/biographical research (e.g. in interviews) and some of the main methodological issues that arise. The section also points to the types of photographic "genres" (containing portraits) that may be drawn upon and questions of skill, training and collaboration (with professional photographers). Section 3—"Social Documentary Photography and Photographic Portraiture"—considers the development and "traditions" of social documentary photography, which routinely contain portraiture. Such work is relevant for social science research in placing individuals in their social, political and environmental context. In Section 4—"The Photograph and Reality"—the nature of the "photograph" is considered: how a photograph is produced, by the photographer, the camera and the computer. The photograph is a complex construction in composition and subject to shifting interpretation. The "relation" between "reality" and the photograph is taken further in Section 5—"The Photograph: The Mirror, the Screen ..."—with reference to how we perceive portraits, as a mirror, or screen, or veil, etc. in and through which we try to "recognise" our image given in front of us. Thus, we can have a number of forms of interpretation or scrutiny of our self image. The history of photographic portraiture and its relation to the history and practice of painting is briefly outlined in Section 6—"Photographic Self-Images: Portraits and Self-Portraits"—including, particularly, the notion of the "pose". Section 7—"Narratives and the Photographic Self-Image"—provides a brief overview of the idea of "narrative", with narrative construction seen as an attempt to give meanings to the diversity of life experience. This is followed by how we "look" at self-images—how we connect images and experiences, a process involving the emotions and senses. Section 8—"Narratives: Visual and Written Text Materials"—explores the relation, differences and similarities, between the visual imagery and written materials according to methodological issues and narrative construction. Questions surrounding memory and time and photographic self-images are discussed in Section 9—"On Looking and Relooking at Photographs—Memory and Recurrence". Here are questions concerning how we "retrieve" and "re-experience" an image and its context according to the senses and subsequent experiences (and viewings). Section 10—"Conclusion: Responses to Photographic Portraits"—makes clear some of the paradoxes of the photographic self-image: for instance, while the photograph is of us, it still seems unfamiliar; we also "project" our self to others, while we "protect" an inner sense of who we are. Finally, in "Section 11—Epilogue: The Use of Photographic Portraits in Research"—the article draws up some guidance for the application of portraits and self-portraits in biographical and narrative research studies. [2]

2. Photographs in Current Biographical/Narrative Social Research

When we see photographic portraits of ourselves, maybe in an album of pictures including family and friends, commonly taken of holidays and celebratory events, a process of recognition (or "re-cognition") takes place which can vary in intensity and length. We recall the context and date, as far as we can, but this process of "looking" is not merely a "factual" scanning—as we survey the image, past associations and emotions are recovered and "brand new" thoughts, perceptions and feelings stimulated. Here are implicated questions of memory and time, identity and self-image, sensual connections, accompanying mood and, possibly, a personal life assessment, that are related to the seen image. We may ask ourselves:—"Has something been lost?", "Has something been gained?", "What has changed?", "What has remained the same?"2) [3]

This article is concerned with the use of the photographic camera and the interpretation of the "photographic self-image"—portraits of us by others and self- portraits.3) The photographic camera can, it seems, "do" many things: it can "shoot", it can "capture", it can "pry", and can reveal "secrets", both seeing things anew and (appearing to) confirm "what is". It lays "things" bare: "... the meaning of a camera, a weapon, a stealer of images and souls, a gun, an evil eye ... colder than keenest ice, and incalculably cruel" (AGEE & EVANS, 2006 [1941], pp.320, 322). [4]

The photographic portrait (including the self-portrait) was once seen as a lesser photographic form, a mere mechanical reproduction, but nevertheless was also appraised as demanding just as great technical skill, and as highly regarded artistically as any other photographic genre.4) It is at once both mundane and enigmatic:

"Of all the genres of photography, the most charismatic, and therefore the most difficult to resolve successfully, is the portrait. A portrait photograph immediately grabs the viewer's attention and triggers profoundly personal responses—emotional, paradoxical and not always rational. The issues raised are complex, challenging, even treacherous, revolving around the self and its representation, identity and immortality" (BADGER, 2007, p.169). [5]

The use of "visual" materials (photographs, film, painting etc.) has been generally neglected in the history of social science research.5) In the development of the social sciences, and humanities more generally, there has (in fact) been varying attention to visual materials. For instance, in terms of portraiture, literary/historical biography have routinely featured individual and group portraits (and photographs of birthplace, the person at work, on travels, etc.), whereas most other fields have given scant attention to such materials. In sociology, there was some use of photographs, as in the early days of the Chicago School. In anthropology there is also an uneven history of use of visual materials (photographs and film). Usage can be traced from early colonialist and traveller origins to academic research in the 1940s (BATESON & MEAD, 1942), before a demise and a more recent reappearance through "visual studies" in the 1970s onwards (see HARPER, 1998; PINK, 2006, pp.9-15).6) [6]

Despite being broadly overlooked in the past, visual materials are increasingly being explored in innovative ways within the social sciences. and, in particular in narrative and biographical research. Commonly, research on individual narratives and biographical life histories has been based primarily on transcript materials (written texts) gained from different forms of extensive interview (and, additionally, perhaps various kinds of other documentary materials, such as field notes). However, as RIESSMAN points out (in reviewing visual materials in narrative research), other forms of communication such as bodily movement, images, sound, etc. are now being considered more extensively (and in conjunction) in the study of individual lives (and in broader social research) (RIESSMAN, 2008, p.141; see also FINNEGAN, 2002; PINK, 2007). As she describes, painting, photography, collage and video, ranging from "found" to "requested" images, are now being investigated. Various types of approach are being employed such as "photovoice", "photo interviewing" and "photo-elicitation", " reflexive photography", "photo novella" and "autodriving" (see COLLIER & COLLIER, 1986; HURWORTH, 2003; RIESSMAN, 2008, pp.153-159; WAGNER, 1980). In addition, numerous kinds of analysis, interpretation, and theory (from differing disciplines) are being used to address the context of production and specific aspects of the image (RIESSMAN, 2008, p.180; see also HALFORD & KNOWLES, 2005; KNOBLAUCH, BAER, LAURIER, PETSCHKE & SCHNETTLER, 2008a; BOHNSACK, 2008). A broad range of "advantages" of using visual materials in narrative and biographical study—and in qualitative research generally—have been described: they can be used throughout research (e.g. as a research diary); to stimulate memories; to help others understand experience and outlook; as a key aspect of participatory or collaborative practice; to create new ideas and aid interpretation and theory; as interrelated with other methods and data; and to produce additional, richer interview material (see RIESSMAN, 2008; HALFORD & KNOWLES, 2005, and also HURWORTH, 2003; KNOBLAUCH , BAER, LAURIER, PETSCHKE & SCHNETTLER, 2008b). [7]

The use of photographs in sociology, and in auto/biographical sociology in particular, creates a series of methodological issues.7) For BECKER (1974), in his early exploration of areas of concern (before the subsequent "explosion" of qualitative methodology) these included training, truth and proof, sampling, reactivity, access, and conceptual procedures. Interestingly, BECKER elsewhere has also compared the characteristics of visual sociology, documentary photography and photojournalism by assessing the purposes of images from each area (1995). Immediate issues for sociologists, in considering photography for sociological research, are knowledge of photographic genres, the necessary photographic ability or familiarity with the practical and interpretive skills required, and relevance and benefits of images for a specific investigation. For example, the range of photo "genres" that may be drawn upon is very broad, such as documentary, street, war/conflict, news, portrait/studio, fashion, "family album", "wedding", pornographic, and abstract, and each has a different purpose, scope, function, audience or "aesthetic" and may be "amateur" or "professional" in origin. In addition, for research purposes, images may be already in existence (e.g., in a family album, on a mobile phone, in personal networking on-line albums, in an archive, etc.) rather than taken explicitly for the study—and this difference should be kept in mind. In terms of portraiture, for instance, it is important to recognise that "found" images of individuals can have differing "functions"—for personal, family, work and public reasons, and can be intended to depict age, status or other identifying aspects of individuals. Questions also arise concerning the relation between images and text (see Section 8), for example, both the text or image can "describe" or "illustrate" the other, or the text can be part of an image—intentionally included or added later within the image, or as title or caption. Images can be placed within, before or after bodies of text. Finally, more "abstractly", photographic portraits may be taken as both "material" and "artistic or representational" objects, both "showing" and also seeming to "stand in" for the individual portrayed (WEST, 2004, p.43). [8]

If the sociologist wishes to collaborate with professional photographers then there are further issues involved, especially in being clear what is wanted for sociological purposes. Of course, if the sociologist wishes to take the research photographs—or requests the research participants to take them—then there are questions of technical skill in using the camera and in processing via the computer, the quality of the images required, and degree of competence in how the images are to be presented (digitally and/or by print). Various kinds of collaboration between researcher, photographer and research participants can occur. If the research is to use already "found" (taken) photographs (e.g., in research using family albums, archived existing portraits, and so on) then this may produce further questions (e.g. contacting individuals shown for consent and copyright, relevant knowledge of the context and date, etc.; see DRAKE, FINNEGAN & EUSTACE, 1994).8) [9]

In summary, self- portraits and portraits fulfil various social functions: for research purposes they can be "found", or can be made by the researcher (for instance, as part of a research diary, to "illustrate" the research scene, or to provide portraits of participants, etc.), or with/by the research participant(s) (e.g., in collaborative, participatory research), or with/by a professional photographer. Photographs can also be taken at any point or throughout the research process, before/during/and after. However obtained, they can be used in research to gain oral (i.e., through forms of interview) or written comment and/or as part of "projects" combining with forms of art or artefacts. It is probable that different memories are gained in interviews where images are included than in those that do not include reference to images. Finally, it must be noted, the field of portraiture is very extensive, including, the "singular" portrait; the individual within a group; and the self-portrait/portrait placed in contemporary, historical, fictional or mythical context (through use of costume, backdrop, etc.). Also, there are issues regarding what the portrait and self-portrait is intended to reveal or express, e.g. skill, status, character or ageing, illness, and other characteristics, and the need to recognise the development and cross-cultural history of portraiture. Here, in this article, I will consider photography, and its place within sociology, only very generally; rather the focus is on examination of the meaning and use of photographs of self for qualitative research. [10]

3. Social Documentary Photography and Photographic Portraiture

An important area of "contact" between photography and sociological research, in terms of subject matter, and to some degree, intent (e.g. charting societal change and raising social issues) is "social documentary photography" (see LENMAN, 2008, pp.173-179). Current researchers in visual anthropology/sociology are well aware of social documentary photography and the use of the combination of photographs and text in the "documentary photo book", but this influential and important work merits further scrutiny (c.f. CALDWELL & BOURKE-WHITE, 1937; LANGE & TAYLOR, 1939; LANGE, 1982; CORWIN, MAY & WEISSMAN, 2010). There is growing interest, at least in Britain, in the history and recent development of forms of social documentary photography, by photographers, cultural critics and galleries, as indicated by publication of both newer and older work (see TATE LIVERPOOL, 2006; MELLOR, 2007; WILLIAMS & BRIGHT, 2007; SEABORNE & SPARHAM, 2011).9) Prominent recent photographic issues have been focused around the connections between photography, surveillance and voyeurism, etc. and the possibilities of street photography in current socio-political contexts (see HOWARTH & McLAREN, 2010; O'HAGAN, 2010; PHILIPS, 2010). This tradition of social investigation and documentary reportage (PRICE, 2004) can be traced back to RIIS's photographs of the poor in New York in the late 19th century; HINE's images of work people and social conditions (c.f. with the Pittsburgh Survey) in the early 20th century; and the famous work of the Farm Security Administration (FSA) in the US and other documentary in the 1930s, depicting the lives of farm workers and others.10) A related documentary form is the "photo-essay" found in the photo-magazine in the inter-war years up to the early 1950s.11) The "pinnacle" of the "photo-book", which also broke "beyond" the "genre", was AGEE and EVANS's "Let Us Now Praise Famous Men" (originally to be an article for Fortune) based on the lives of three farming families. It is a poetical, biblical, factual, descriptive, radically auto-ethnographic script which veers from the smallest aspects of the life of poor tenant farmers to profound questions of human existence (2006 [1941]; see also ALLRED, 2010, pp.93-131; RATHBONE, 2000; HAMBOURG, ROSENHEIM, EKLUND & FINEMAN, 2000; MELLOW, 1999, pp.306-331; MORA & HILL, 2004; STOTT, 1973). One very striking feature of the work requires comment: EVANS's photographs (including individual and group portraits) are displayed uncaptioned at the very start of the book. [11]

Another "tradition" of the "photo-book" can be identified, leading back (in particular) to the work of BRASSAI on Paris, and BRANDT on the "English", in the 1930s (BROOKMAN, 2007; CAMPANY, 2006; DELANY, 2004; POIRIER, 2005) and surrounded by a broader current of "humanistic realism".12) This was followed during the mid 1950s, when an ambivalent, alienated, or ironic view of social life (often transgressing photographic conventions) was offered in Robert FRANK's "travelogue" across the U.S. and William KLEIN's view of New York.13) This work not only pointed to social division and the gap between reality and illusion, it was also a personal account of creativity and experience (BROOKMAN, 2010, p.219). It was influential on the growth of "street photography" (with its mix of the "quirky" and "mundane") depicting urban lives, during the 1960s and 1970s (see SHORE, 2008; WESTERBECK, 2005; WESTERBECK & MEYEROWITZ, 2001), and later photographic studies on the "underside" (e.g., drug addiction) or marginalised areas of social life. [12]

In documentary photography there is an initial problem of what is "documentary" or a "document" (see STOTT, 1973; LENMAN, 2008, pp.173-174) and a related deeper question: what are the "assumptions" which underlie the approach taken about the social world and/or its representation?14) These assumptions (it can be said) broadly stem from the "traditions" of "naturalism" and "realism" in artistic endeavour (including photography) in the depiction of "social scenes" (see ROBERTS, 1998; WILLIAMS, 1991; and also AGEE & EVANS, 2006 [1941], pp.205-217). The above areas of photography (social documentary, photo book, street photography, and related areas) are important sources of portraiture since they show people situated within their everyday social situations. To these "genres" can be added, for research purposes, "found" sources such as professional portraiture (in the studio and elsewhere) and informal picture-taking (by friends, families, etc). Finally, at least some mention should be made regarding the "documentary" work oral historians who have long used portrait and other photographs in the study of working lives, communities, health, migration and other areas and more recently have pioneered Web based resources (recorded interviews with transcripts, video, photographs, and the practice of "digital storytelling", etc.) (see FREUND & THOMSON, forthcoming; ROBERTS, 2008, par.76-81; see also ROBERTS, 2002, pp.93-114). [13]

The "real" in our daily living confronts us as a "rush", a myriad of visual and other sensual experiences; we search for connections (and "rhyme") amongst these "happenings". We respond to the world through the construction of interpretive meanings by, for example, the "typification" of individuals, events and objects. These narrative-biographical meanings we associate with experiences in the social world, and transfer and adapt them to other individuals, situations, etc., deemed to be similar, to guide our actions. In viewing photographs we refer to these previous "reserves of knowledge" that shape action, adapting them to current experience and anticipated situations. Through the act of photography (taking pictures of people, situations and our environment) and viewing images, we seek to give form to experience and structure to memories. [14]

Photographs can have the character of appearing to be "more real than real", due to their "glossiness" and heightened colour and definition—and have a directness of perspective that seems to include us as the viewer; they can seem to give qualities not only of a "super-reality" but of "fantasy" or "dreaminess", "uncannily like the world we know, yet more perfect, ordered and coherent" (EDWARDS, 2006, pp.101f.). Yet, the photograph is the result of a series of decisions and detailed applications by the photographer, involving choosing its context, selection of topic, the precise "moment", the focusing and framing of the image, etc., and a series of further processes through to its final presentation on a digital screen or as a print. By cropping (omitting part of the original image), increasing or decreasing depth of colours, darkening highlights or lightening shadows, sharpening, adding or reducing contrast and hue, and manipulating the image in other ways (e.g. erasing, or introducing new, elements) in the camera and computer, the image can be altered very substantially. In portraiture, "correcting" or "refining" the image (actions which have taken place since the beginning of photography), is not simply a "technical" or (even) an "aesthetic" exercise, it is intimately concerned with how we wish to portray ourselves or others and want an audience to see the image. Thus, when a photographic image is taken, there is a "composition" of a scene or portrait by angle, focus, framing, and other camera settings (e.g. image saving format), and then "computer work" by storing and editing/amending the image via software programmes. On printing, there are the additional characteristics of the printer (in tone, sharpness, colours which may differ from what was seen on the camera and computer screen) and the paper quality and type (and size of image) which may significantly affect the photograph and its reception. Thus, from the "reality" seen by the photographer to the digital image and photographic paper print, "amendments" are made along the way. There is then a very complex process of construction of the "representation of reality" before the viewer sees the final digital or printed image. Further, it should be noted, photographic aesthetics, style and appreciation change over time, and technological advances bring new photographic possibilities. [15]

Just as within the camera itself, or later on a computer and printer, we can change the image that has been "taken", so in our minds (interpretively, visually, emotionally) we can edit and track changes made. When viewing ourselves in a picture, through memory and reflection in our "mind's eye", we are also involved in an "editing" process—as we "crop" (i.e., concentrate on an aspect of the picture and determine what is to be "seen") or otherwise "alter" the image. Again, there is a "sensual" and "emotional" editing (a re-memorisation of words, sound, taste, smell, or touch) as well as internal visual modification, as an image is modified and ascribed new connotations. We may "re-date" and "re-contextualise" the image, perhaps by placing it in a different position where there is a sequence of existing images (as in the album or slide show) in "reviewing" our memory. [16]

In interpreting a past portrait within our current lives, we may not only be responding to others' comments or an anticipated audience, perhaps thereby, bringing new notions of its meaning(s) to us, but also be attempting to fit it into our current self-conceptions. Our memory of the self-image may, therefore, change a great deal on re-viewing. Looking back at an image of ourselves can lead us to re-evaluate our current self-image (and contemporary pictures), perhaps observing: "I have changed a great deal"; "I still look much the same". Re-viewing of images of self may well provoke self-questioning: "What was I doing?"; "Why was I doing that?"; "How did I do that?"; "When was that?"; "Where was I?" Images of self can importantly produce "what ifs", in terms of the self and action—"What if I had done that then, I could be this now or that in the future." In seeing photographs of self once again we re-connect elements of our lives. We "narrativise" and "fantasise" in the experience of looking and modifying, we re-compose a sense of self: "Who and What I was/might have been"; "Who and What I am or might be"; "Who and What I will be/could be" In this re-composition we draw on previous evaluations and current social relations, and also, wider "narrative" models of life (e.g. from the broader media and culture) and make applicable to our daily experience. [17]

5. The Photograph: The Mirror, the Screen ...

Photography has undergone immense change in the past twenty years or so. Digital photography, in particular, has brought the ability to produce, store and retrieve thousands of pictures very easily for re-viewing—and the camera can do more things "automatically". Instead of sending a film away to be "processed", a digital image can be viewed, manipulated, and reproduced within the camera, and on the home computer and printer. Digital technology, in addition, makes it very easy to insert images into written text or give a caption (and place text on) to a picture. It also allows our self-images or those of others to be readily taken on phones or palm sized video cameras, and shared via e-mail and posted on social network Web sites. These viewings of self have become routine, alongside the "mundane" seeing of our image in the daily round—in the bathroom mirror in the morning or evening, perhaps in a lift mirror at work, on a CCTV screen15) in a shop, or by glancing at our photo on an identity tag or card. Most viewings of images of self, whether digital or otherwise, tend to be cursory and sporadic without much circumspection—but, just occasionally we are "brought up short" by "catching" our image in a shop window or other reflection, and ask "Who is that?"; "Is that me?"; as we ponder for a moment, the image in front of us—our own "reflected self"?16) [18]

The common, "everyday" assumption of the photograph is that it "mirrors" "reality"— it is a faithful record of what is seen by the photographer and the camera. But, this idea fails to account for how the photographer and camera "see". What is "produced" by the "camera eye" (we can say again) includes what happens "technically" (automatically via the manufactured specifications of the camera) and, of course, also includes the photographer's actions in choosing camera "settings" from "menus" (e.g., light sensitivity), and the processing of the image in the camera, computer (and printer). Having said that, the photographic image could be taken, in a sense, to "reflect" like a mirror, to some extent—it does take from "reality", what is reproduced is recognisable as the person, landscape, etc.17) However, even if a picture is initially perceived as a mirror image of reality—of what was actually viewed (i.e., an object), even so, the image has still to be "seen", to be interpreted. In the detail of the image, or in the image as a whole, something different from that taken as "reality" may be apprehended—possibly resulting in some surprise. On subsequent occasions of looking, new meanings can be formed which (again) can possibly be quite unexpected. Nevertheless, in interpreting a photograph of ourselves, the idea of "mirror" may well be the routine or initial interpretive "frame" that we apply—and our "re-look" may not, in fact, raise a reaction that is much different, perhaps, from previous occasions when the image has been glanced at or surveyed, etc. But there is another sense in which the photograph may be conceived of as a "mirror". In the self-portrait, in its multiple forms, the individual perceives him- or herself as both "self" and "other", as "subject but also as "object"; simultaneously, we "are" the viewer while viewing our "double" who (it seems) may be looking straight back. It is as though we are looking in a mirror which shows both ourselves and someone else: "These qualities make self-portraits both compelling and elusive" (WEST, 2004, p.165). This "otherness" we also sometimes experience in looking at a "real" glass mirror or other type of reflection. Similarly, when we see another's self-image (especially if the face fills the frame) we might, just for a moment, confuse the staring face as our own. [19]

In summary, the notion that a photographic image provides a straight reflection of the "reality" of people, a scene, a landscape, etc. assumes that by "simply looking", we "know" the image as reality. The knowledge that the taker frames the picture and operates the camera settings, of the technology involved in the camera and computer in "capturing" the picture, and then the further effects of printing (the printer's characteristics, the type and size of photographic paper used, etc.) is "bracketed off". But, if the photograph is more than a "mirror" in how we interpret an image reflection of "our reality": what do we see when looking at a portrait of ourselves?" Or, perhaps we should rather ask: "How do we see?"—"What might the act of looking also be?" While our image is "caught", what is it to be "captured"? [20]

Apart from as a mirror, there are other significant ways through which we interpret our self-images. On seeing the photograph it may take on the properties of an impenetrable "screen"—simply a flat surface that cannot be seen through (i.e. like a cinema, computer or TV screen). A screen can "screen off" something by obscuring, protecting or hiding; in this sense the memory(ies) that a particular photograph may be associated with may "mask" an earlier, a contemporary (at the time of the photograph), or even a later experience (including in the "present" of the viewer).18) Or the photograph may be taken as a "window" or "portal"—a fully transparent surface that we can see, and even imaginatively be transported beyond.19) In between screen and window lie other possibilities, particular points on a continuum, ranging from near transparency (almost as a window), through various degrees of opaqueness, "frostiness" or "cloudiness", to where an image of self (or other image) is difficult to recognise but will (perhaps) emerge if we peer long and hard enough (as if the "mist" of the "crystal ball" will lift). Or, the image may have a different semi-transparency, like a veil, gauze, bead curtain, etc.—as having a porosity or permeability in which elements are missing or obscured: if only we can find and fill in the missing pieces we believe the image will be completed. Perhaps the photograph is also a "microscope" or a "magnifying glass"—as we look deeper into it, we "blow up" parts or the whole of the image, to see what is there for clues to personal mysteries and what links our past, present and future.20) Interpretively, looking at the image, as screen, window, and veil, etc., we are trying to see through the surface image to find out what lies behind—to explore, to clarify, to fill in gaps in self-understanding. A second look or closer examination may reveal something beyond the surface, what does not seem readily apparent—appears to take more shape, the "lost" parts become defined, and new elements emerge and cohere, as understandings form and a self(ves) is/are constructed. [21]

In gazing, peering, examining the image, we are attempting to understand what we were then, and what we were before and after the photograph was taken; we are looking at the photograph for what it can tell us about how we have changed—"What has become of us?" The photograph, whether taken as a screen or window, etc., seems to "tell us" about our life then and "invites us" to make connections in experience to the "now" and our future (see MITCHELL, 2005). The act of "looking" may also give a glimpse of secrets, lifting an "apparent reality" to reveal what seemed "hidden"—adding what is missing to complete a picture, seeing through what is opaque, etc. to find "new" personal meanings. [22]

Instead, therefore, of a reflection accepted as a simple, anticipated, unreflexive" truth", the image of ourselves, then, could be met with deeper self observation or self absorption (engrossment). What at first may seem a mere "mirror" image becomes, perhaps, something intriguing or profound. Here, a questioning or search for "self" may begin; rather than an unreflexive confirmation of an assumed self, an interrogation of being in association with photographic image, raising (if pursued) questions of the relations between real/unreal, reflection/ transparency, recognition/ non-recognition. So, in the act of looking there is a process of "doubling" of the self (a "seriality")—the formation of multiple and differing images of "selves" in time: "That was what I was"; "That is me still"; "I could have been that then ... and now ... and in the future" (see ROBERTS, 2011).21) We may not be merely glancing at a photograph of a past transitory episode, a moment in our lives, but seeking to find how it fits into a trajectory, pattern and meaning of our existence. The portrait was "us" but is it still "us", as then, now and in the future? [23]

6. Photographic Self-Images: Portraits and Self-Portraits

The emergence of 19th century photographic portraiture drew upon classical and religious art traditions in picturing the upper classes. But alongside such traditional influences were contemporary developments in "scientific" thinking (phrenology and physiognomy—the head and face as indicators of "character") and the impetus to record "facts" on the "dangerous classes" (and monitor the perceived "threats" of crime and disease, c.f. the rise of "court", "census" and other "social statistics", and the invention of fingerprinting) (see ERTEM, 2006). Thus, photographic portraiture was both a means of representing the "bourgeois self", as well as recording and archiving information (i.e., the "criminal portrait") for purposes of social regulation. The photographic portrait (initially taken by a professional or well-off amateur) quite quickly lost its exclusivity in recording high "status" (although still used in this manner, as in "official" and "news" photographs" of political, business, academic leaders and others) or as part of the social activities of the wealthier classes. It had become a widespread phenomenon by the late 19th century. The recording of personal milestones, family celebrations, work or leisure activities, social conditions, or used as "calling cards", etc. amongst other social classes became commonplace, even as early as the 1850s, photographic societies were being founded.22) [24]

It should be noted that there are various ways that photographic portraits can be made. A self-portrait by an individual can be taken: by means of a tripod (or surface) and using a remote control or time delay on the camera; by photographing a reflected image in a mirror (or other reflection from some shiny surface, see Illustration 1); by holding the pointing camera out at arm's length; by using a commercial photo-booth; or by photographing a silhouette/shadow. Where a portrait is taken by someone else, the degree of "control" over "posing" for the camera can vary from the "subject" setting the camera for the taker to press the release button, e.g., ranging from the tourist asking a passer-by for help, a friend taking a picture of an individual or group, where someone "directs" the pose (e.g., the commercial "photo-shoot"), to the "candid" photograph taken perhaps without the individual's apparent awareness. [25]

Photography, from its beginnings, was taken as both a technical, automatic recording of the object (requiring little from the taker) while also as an "art" due to the intervention of the photographer—a dual legacy that appears to remain (ERTEM, 2006; EDWARDS, 2006). A discussion of the photographer's role in relation to the "photographic portrait" opens parallel interesting concerns surrounding the processes of representation in art (painting, drawing, sculpture, video, etc.), however, while these are relevant, they are too large to be tackled in detail here. Even so, the great extent to which early (formal) photographic portraiture had similarities with painting traditions, as in the formation of the "pose" (e.g., stance, expression), should be noted (see EDWARDS, 2006, pp.40-48; ERTEM, 2006; LENMAN, 2008, p.517). Commentaries on connections between portraiture in painting and photography often include associated concerns: facial expression and character, "likeness", deportment and iconography (e.g., connections between portraiture and religious images), and "authenticity" and representation (see WEST, 2004, pp.34-37; FREELAND, 2010; GAGE, 2004; BARLOW, 2004; CUMMING, 2009; VAN ALPHEN, 2004; WELLS, 2004; WOODALL, 2004a). Keen debate continues on issues regarding the relation of photography to "art" (see COTTON, 2004; FRIED, 2008). [26]

All individual portrait photographs (whether by self or other, "posed" or "candid", etc.), at least to some extent, can be regarded as part of (or representing) a "type"—according to activity, dress, manner, etc. depicted.23) Certainly, when an individual "poses" there is the social influence of mores on "how one should pose", given the situation, one's status or age, etc., for an intended audience. Of course, a prime function of some portraits is to denote social standing (e.g., achievement), character (e.g. dignity) or physical attribute (e.g., attractiveness) within a group or institution, or to an audience. The "pose" (and expression) has socially "given" aspects, and so the "self-portrait often repeats familiar conventions" in particular periods; but "it also brings scope for complex interpretation" (RIDEAL, 2005, p.7) e.g., in what the pose is meant to convey, its diversity at specific moments, and when it changes new conventions are formed. [27]

A great deal more could be added, here, about the formation of the "pose" (of a single individual or person as part of a group) and related issues in portraits in photography compared with painting (see, FRIED, 2008, pp.191-235; KOZLOFF, 2007, pp.7-11; WEST, 2004). However at base, as BADGER argues, the pose "is closely related to the question of appearances":

"If photography is essentially about scrutiny and observation, it must also be about the pose, for the pose is the subject's presentation of his or her identity to the photographer, an act which ensures the preservation of that identity. The old idea that a photograph steals the soul dies hard, and not altogether without cause, because the pose is the subject's defence. It is an essential element in the representation of the human figure, the mediating step taken by the sitter to 're-present' his or her interface with the world" (2007, p.174). [28]

Even though the pose can vary according to context and other factors, in essence, it can be said that, we "show ourselves in a 'pose', but we also hide behind a pose" (HOLSCHBACH, 2008, p.17) [29]

We must not forget that "styles" of photographic portraiture are very varied and, for instance, include "art photography". The differing styles of portraiture overlap with each other and also with wider photographic genres. The nature of portraiture is changing rapidly; contemporary portraiture is increasingly cognisant of the developing socio-technological context. According to one view (in a discussion of art photography) those "who wish to say something meaningful about the face are looking for strategies and tactics to match its rapidly evolving social and technological environment" (EWING, 2006, p.13). [30]

7. Narratives and the Photographic Self-Image

Individuals attempt to give meaning, order and direction to their lives, in the face of the diversity and intensity of experience, through the formation of "personal narratives".24) Such individual accounts may be shifting or relatively static, too changeable so they lose connection and pattern, or too "set" as to be unable to have a flexibility of self to interact sufficiently with social surroundings, thereby, inadequately guide necessary lines of personal action for a coherent and a "versatile" "sense of self".25) Narratives, at the one extreme, bring a personal stasis or repetition, while at the other, a dizzying swirl of self-reconstruction and fragmentation—and so, tending towards, at one pole, a certain fixivity of past memory, while at the other, an endless round of hope, fear or confusion brought by an ongoing search for, or arising from, new identity(ies) which resist consolidation (McADAMS, 1993, p.166; see FRANK, 1984; KLAPP, 1969). However, between these poles, narrative formation and reformation can provide the necessary means to review and "re-view" (although with varying degrees of self-reflection) and give a "provisional order" to our lives. As RIESSMAN (2005, p.6) states:

"Narratives do not mirror, they refract the past ...The 'truths' of narrative accounts are not in their faithful representations of a past world, but in the shifting connections they forge among past, present and future. They offer storytellers a way to re-imagine lives ... narrative analysis can forge connections between personal biography and social structure—the personal and the political". [31]

Several "fundamental" types of narrative have been identified by researchers, which tend to be found empirically in mixed examples in particular cultural contexts and actual personal accounts. For instance, GERGEN and GERGEN, describe basic types as "the tragic narrative", "comedy or romance", and the "happily ever after" myth with more "complex variants" being located in actual individuals' narratives (1984, pp.176-177; GERGEN, 1999, pp.70-72). GERGEN and GERGEN emphasise "dramatic engagement" in narratives—the emotions, feelings, and drama associated with connections in experience (ROBERTS, 2004c, pp.91-92). Of further interest here is BROCKMEIER's notion of "autobiographical time" or orders of "temporality" and connection. He identifies six narrative models of autobiographical time (linear, circular, cyclical, spiral, static, fragmentary); each has a different "vision" of the "course" and "direction of time"—with key metaphors expressed which bring together the periods and elements of the life account (e.g., an "arrow" for a linear model) (BROCKMEIER, 2001, p.461; see also BROCKMEIER, 2002; ROBERTS, 2004c, pp.92-93; SMITH & SPARKES, 2002; SPARKES & SMITH, 2003). Although our "starting point" is our location in the present, we may move through various "time perspectives" in the past, present and future in interpreting images of ourselves—different trajectories in trying to understand the "passing" of our lives (see ROBERTS, 2011). [32]

The construction of a self narrative rests fundamentally on the personal ability to make clear linkages between life events so as to make experience intelligible—an attempt to give some coherence. Individuals will vary in the degree to which they are able to make some pattern out of experience and this endeavour will differ in strength over time. A wide range of connections may be made by individuals in constructing autobiographical narratives, such as coincidence, fate, chance, choice, contingency, fortune, preordination, déjà-vu, and serendipity, and these we may apply when we view our portrait photographs. These techniques are employed by individuals to make attachments between the myriad of experiences, emotions, and events that occur in life—to order and relate, and establish "rhythm", "theme" and "flow" in, simply, "what happens" to us. Life connections, or how we associate one memory (of a person, event, feeling, piece of music, conversation, place, etc.) with another, are intricate and varied, and are used to "compose" our "life" and sense of self. Some forms of connection allow for more self-agency ("I chose to take that direction"), others are perceived as the result of social or other circumstance ("I had no alternative due to ..."). The connections we make in joining our life-experience may be rhetorically summarised in metaphor or simile—"Recently, my life has been a 'roller-coaster'"; "My life has been like a river, I have gone with the flow". We imaginatively comprehend our lives as auto/biographic composers in trying to gain "composure" and (re)compose a "sense of self"—in words, verbally and in thought, visually and according to the other senses (SUMMERFIELD, 1998, pp.16-17; see also SHERIDAN, STREET & BLOOME, 2000; ROBERTS, 2007, pp.44-46, 2011; ROBERTS, J., 1998). [33]

The use of these connections need not be consistent in a given individual narrative. As we recall, we interpret and re-interpret (i.e., re-view, re-feel, etc.), "living" in a retrospective-prospective endeavour to give meaning to what has occurred, what is taking place, or may happen—in a vain effort to give a definite linearality, consistency and understanding of life's diversity. In terms of images we also re-visualise (if the image has been seen previously by us) and modify sensual-emotional re-associations, a process apparent when seeing our portrait photograph. This process of "looking", therefore, includes an interpretation of the seen elements of the photograph but also engages the other senses (touch, sounds, etc.) as it engenders memories of the scene portrayed. The influences of contemporary personal experience—the immediate context, our broader personal circumstance and outlook—feed into this process of "looking"; and even the "feel" of the photograph, its frame or folder, and the effect of reading any written caption or dedication, can affect our response to the image. We do not only "visualise" our lives—we also "perform" our life in the mind, as well as in action, through our sensual, aesthetic, artistic and everyday capabilities. [34]

8. Narratives: Visual and Written Text Materials

There are some very complex issues regarding the relation between visual (and aural) and textual materials in narrative analysis. Apart from the kind of visual and written textual materials to be presented, these can include: the extent to which they are meant to largely "stand" separately when presented on the same subject, providing different "accounts" (for possible indirect comparison, contrast, etc.); the degree one "describes", "supports" or, even, "subverts" the other (some kind of implicit/explicit interplay, by irony, humour, etc.); implications for how they are represented in form (e.g., on the Web), their proximity, sequentially, simultaneity, etc.; how much material from each is given (n.b. one may be used to "summarise" the other); and, finally, whether other materials (e.g., objects) are placed with the visual and textual materials, and so on.26) [35]

A substantial number of methodological similarities in approach have been pointed out between visual analysis and text based methods, as in the use of transcribed narrative interviews.27) For instance, it is argued, that both the camera and tape recorder do not merely "record"—instead, the photographer and interviewer operate in specific situations and have degrees of control in recording/selection; both means can be used to aid description of context, argument, interpretation and theorisation by the researcher; and the materials from both methods require close analysis. Also, it is said that there is not a "simple realism" in narratives or images—rather, interpretation is required and on-going, since new insights can be made; the materials from both can be used productively together; and, finally, both methods uncover only a "fragment" of experience (RIESSMAN, 2008, p.181). For RIESSMAN

"[a] photograph stabilizes a moment in time, preserving a fragment of narrative experience that otherwise would be lost. Transcripts or oral narratives similarly 'fix' a moment in the stream of conversation. But ... the same oral narrative can be transcribed in different ways, each pointing interpretation in different directions and, if the conversational context changes, the speaker would likely shape her story for the new audience. Related issues arise with images ... In a word, investigators must guard against reifying a single transcript or image as the 'real thing'" (p.179). [36]

WEST argues, in relation to self-portraits (by artists) that they can be very varied and questions how they relate to narrative and the "revelatory qualities of autobiography" (2004, p.78). She observes that, as individuals, we are a "fragmented" collection of experiences and emotions, etc., but, "autobiographical narrative" seems to aim towards producing a "unified self". She adds, that although a written autobiography is "constrained" by what the authors select about their life to relate, "a work of art" is even more curtailed by "technical limitations" since (unlike video, etc.) it can merely give "a series of frozen moments" (p.78). Both the portrait and the narrative, the picture and words, can be regarded as having a comparable distinctiveness: in the sense that, just as pictures cannot be fully described in words, so words cannot be fully translated into pictures. Further, both are restricted in giving the felt emotion of an individual but are expressions of it, through which we can "describe" ourselves and "relate" to each other. We may not be able to translate a portrait into words to any great extent even if looking for longer than a glance—alternatively, a glance may be sufficient to bring an extensive narrative. Similarly, a narration—short or extensive—may contain little visual imagery in relation to self. A complex issue follows here pertaining to how may photographs of self (by oneself or others) and autobiographical writing be used in conjunction?28) Do portrait photographs aid autobiographical narrative construction, which is caught between a "multiple", "decentred", "fragmentary" self and the need for a sense of cohesion and continuity? Or is the photograph itself also divided between dissolution and unity (between multiple interpretation of the image and the attempt to "impose" order to visual experience) (RUGG, 1997)? We may conclude, on considering these questions, that in the composition of narrative using text and imagery there are two lines of continuum: one visual and one textual—each continuum has the tendency to observe and replicate self-fragmentation and self-division and the striving for self-unification, the self as an embodied unity, and integrated within time and context. For RUGG, the introduction of the photograph into autobiographical narrative lends assistance (and insight) to both conflicting views of the "self"—as a disparate or as a singular entity. Perhaps, the "self" itself may be the attempt to organise, negotiate and monitor—and reconcile ("privately" and "publicly") through performance and presentation—these "polarities".29) [37]

In forming our narratives in relation to a photographic self-image we are aware that the portrait is an indicator of a time passed and time passing, and our eventual end. But it can also represent the past as now in contemporary consciousness, and as in the future (as it will probably "survive" our physical demise)—as memories are re-affirmed, recovered, and reshaped. The portrait photograph

"... is a sign of the passing of time, of the fact that what we see in the shiny surface of the photographic print no longer exists as we see it: it is a sign, again, of our inexorable mortality (as well as, paradoxically, an always failed means of our re-securing our hope of having the photographed subject 'live' forever)" (JONES, 2006, p.46). [38]

Of course, many artists and photographers have constructed self-portraits (e.g., often as engaged in their work) with some narrative content—some, at least implied, "story"—which may link to their daily life-concerns directly or be more "fictional-fantastical-mythical" in orientation (by depicting themselves in historical, "classical" costume or alluding to film or popular cultural "roles"). There can also be multiple self-portraits given in the same picture or as part of a collage, possibly with other images, or as an installation mixing images with various objects. Artists have also included, in a variety of ways, their own portrait in individual or group portraits they have made of others.30) Finally, it is worth noting that within contemporary "art photography" (as loosely described) there are "apparently unselfconscious, subjective, day-to-day, confessional modes", or expressions of "intimate life", and also that the area of "performance art" has concerns with autobiography and the body, and identities (COTTON, 2004, p.137; see also GOLDBERG, 2001). [39]

9. On Looking and Re-Looking at Photographs—Memory and Recurrence31)

On "looking" at photographs of ourselves we are engaged in an imaginative narrative construction (as described above).32) This is not to say that narratives are produced that are fully formed or coherent—there may well be inconsistencies and omissions, and it can be said we are always engaged in personal construction without given endings, as circumstances alter, reflection is modified, memories are re-defined, and "new" memories and expectations emerge. Thus, for example, the personal reaction to a "photographic self-image" may indicate shifts in self perception and construction as individuals relate their lives to and through photographic depictions of themselves. While each narrative produced is a unique account of experience, some general (basic) forms of narrative have been identified (n.b. see above—the "tragic", "happy ending", etc.) often imbued with the individual's overall mood and life-outlook. There is an especially important issue here in relation to "mood" in personal narratives and photographs of self—since some writers have posited that the "photograph" is essentially "melancholic"—recalling the past, as referring to what has gone, or as intimately associated with loss and death (c.f. BARTHES, SONTAG and LÉVI-STRAUSS). Even what appears to be a joyous picture can be taken only as evidence that "all things pass and fade" (EDWARDS, 2006, pp.118f.).33) In this view, the photograph merely records that something existed in another place and time or that, over a period, diverse meanings are accrued and original context and meanings are obscured or forgotten (and so, the photograph becomes merely an "object" for appreciation). Here, the photograph is a given "surface" on which interpretations play and the depth of original associated sensory experiences and memories, thereby, cannot be recovered. But, against this understanding, as EDWARDS describes (following BENJAMIN), we can argue that photographs can bring back the past as active—within the present, and anticipate the future:

"Despite the influence of this argument, this melancholic conception is open to dispute. If photographs encapsulate the peculiar temporal paradox of here-now and there-then, by definition, this condition must work both ways round: as much as the image conveys something of death, reminding us of the unstoppable passing of time, it simultaneously brings a moment from the past to life for us ... Benjamin is important ... in contrast to Barthes, he was committed to making the past active in the present ... concerned to recapture the past from the 'victors' ... For him, nothing in the past had truly disappeared forever; its traces could be rediscovered and put to use" (EDWARDS, 2006, pp.119-120; see also KEENAN, 1998). [40]

"Taking a picture" is an act intended to foster remembering, and by the photograph's continued existence thereby, and so it helps to shape memory of experience. Further, the act of photographing (and videoing) is itself part of the surrounding event to be remembered. To take a photograph—an attempt to "capture" a scene, a ritual (e.g., a wedding), a face, etc.—is, itself, part of our realisation that we "lose" memories (see KEENAN, 1998). Describing the photographic portrait, JONES says that it holds a "promise"; referring to the "performative" work of Cindy SHERMAN and others, she argues:

"The photograph, as is well noted by theorists such as Barthes, is a death-dealing apparatus in its capacity to fetishize and congeal time. At the same time, we are drawn to the photographic portrait image as a promise of delaying or eradicating mortality. In their exaggerated theatricality, these works I look at here thus foreground the fact that the self portrait photograph is eminently performative and so life-giving" (JONES, 2006, p.42).34) [41]

Photographs and "photographing" (as in portraiture) can, in short, stimulate a "memorising" of people, events and objects and associated emotional and sensual experiences which are placed within contemporary thoughts, feelings and circumstances—"We photograph so that we remember". As EDWARDS says, what occurs in this memorising process may not be expected (c.f. PROUST). When we view pictures of ourselves, that perhaps we have seen many times before, we have pre-notions of what we will see and our response, but even so, elements, connections and feelings (as argued earlier) which are not anticipated may enter our "re-view" and narrative construction—especially if we see the pictures with others (and who may also appear in the photograph) (EDWARDS, 2006, pp.120f.). Also a photographic portrait, while recording a face at a given moment, carries some of the past of how I looked and an indicator of some of what I may well become. It portrays both continuity and change, which are apparent when we view multiple photographs of ourselves taken over time. Sometimes we notice some change when viewing a new portrait photograph of ourselves or others that we had not "picked up" in recently seeing our face or that of others in daily interaction; maybe there is something different due to ageing lines around the eyes and mouth, in the skin tone or in hair colour and thickness, and so some shift in expression or "look". Finally, is there a sense in which the camera can "arrest time"? Perhaps, some black and white images, rather than colour, may be beyond "dating", timeless (ASSOULINE, 2005, pp.234, 238)? Such photographic images, like narratives (to which they may be associated) can "separate themselves" from, or rather "go beyond" an era, a temporal reference, and relate to both the original setting (e.g., of family life, a tragedy, war wounded) and to the general features of "humanity"—the perennial human condition, and its aspects such as love and loss, ageing and death. [42]

A finished photograph is subject, however composed, to interpretation and re-interpretation—and it may well be placed alongside others in a digital slideshow, print book or album, which introduces a particular interpretive positioning (e.g. as part of a chronology or alongside contemporaneous images). We perceive images in very complex ways, including through the social context of "looking" (on our own, or in interaction with friends or relatives who are also seeing the same photograph[s]). On viewing an image for the first time, an initial interpretation of its content is applied (drawing on anticipations, feelings, and memories aroused)—these may alter when the photograph is looked at for a little longer or on subsequent occasions. Seeing photographs of oneself generates "memory traces" of time and place, and previous notions of self and social identities. The process of looking can be a more or less emotional, sensual, and often social experience which brings with it expectations, for instance, regarding the self to be seen (including conceptions from any previous viewing). As we shift in self-perspective, from situation to situation, and change physically and emotionally over life's course—we "re-view" our self-image, including when we see our photographic images and those self-portraits we hold in memory (our "image archive" and those of the other senses and the emotions). In short, the "process" of "looking" or "seeing" is a complex entity: it may be just a glance, an "idle" gaze, a "viewing" with others, an inspection or examination, a deep reflection—or some combination of these; even a cursory glance may bring "vivid" memories of images and sensual experience and self-reflection. [43]

When we see a self-image, an intimate process begins—of recognition, non-recognition and "mis-recognition". Just as photographic images can be altered within the camera's technology and on the computer screen by using software programmes—by cropping, straightening, contrast, colour temperature, saturation, lightening, darkening or use of effects to "warm", "glow", "tint", etc., the image— a parallel "internal" editing in the "mind" can be done within memory and imagination. Particular parts of it may be enhanced, omitted, substituted or added in the "mind's eye". These are not simply "visual edits" but include emotional and sensual responses as a picture may be seen new or "afresh" with new thoughts, connections and feelings. Past situations are "brought back" into contemporary experience as subjects for "appraisal" and are "re-lived", "retained", "amended", "re-ordered" or "erased"—are "re-narrativised" and "re-memorised" alongside current experience. As COLLEY (2002, p.92) observes:

"We all of us convert life's crowded, untidy experiences into stories in our own minds, re-arranging awkward facts into coherent patterns as we go along, and omitting episodes that seem in retrospect peripheral, discordant, or too embarrassing or painful to bear". [44]

"Memory" or "memorising" is part of the routine imaginative processes through which we guide action during our daily life. As TOULMIN and GOODFIELD argue, it is central to the construction of "our own personal reconstruction of the past" because it is "the first essential stepping-stone" in linking individuals, through family and others to societal traditions (1967, p.25). Again, what "turns up" in memory is not always expected. As EDWARDS (2006, p.121) argues, in relation to viewing photographs:

"Photographs provoke acts of memory recalling us to things, places, and people. They establish connections across time and space, including chains of association. What will be dredged up in memory's driftnet cannot be predicted in advance: an item of clothing or decor in a picture can spark connections and associations". [45]

Memories, following MEAD, should be seen as situated in the continuing formation of experience:

"We frequently have memories that we cannot date, that we cannot place ... We remember perfectly distinctly the picture, but we do not have it definitely placed, and until we can place it in terms of our past experience we are not satisfied" (THOMPSON & TUNSTALL, 1971, p.144; see PETRAS, 1968; MAINES, SUGRUE & KATOVICH, 1983, p.164). [46]

In this way, "memory imagery" is "fitted in" by an inclusion or exclusion of elements, into a framework of experience—as the "assurances which we give to a remembered occurrence come from the structures with which they accord" (MEAD, 1929, p.237, 1956, p.335; see also FLAHERTY & FINE, 2001). In memory we may recall and structure not only the "whats" and "whys", but also the "what ifs", "if onlys" or the "fantasies" of experience. Indeed, "fantasy" is a critical feature of memory and should not be deemed as mere "fancy"—as occurring only in some trivial remembrance, a mere "day dream" or seen as only idle speculation on what may happen. It is necessary in reviewing our life and rehearsing our future (see ROBERTS, 2007). [47]

Memories that we have are more than mere sets of "retrieved" images that were framed in ongoing experience. Any image is associated with its past context and the current circumstances of its "revival"; it connects with the range of senses (e.g., a remembered image of a person may bring the sound of their voice). Past experiences "are not merely visualised but also re-experienced by being "re-heard", "re-smelled", "re-touched" and "re-felt", etc." in memory—"a recalled image, a remembered piece of music, or a taste, or an odour may bring an association with other sensual and emotional feelings" (ROBERTS, 2007, p.43). It is clear that "some of our most powerful and important 'memories' may initially arise from dimensions other than the immediately visual—and all memories, in whatever form, are 'evocative'" (p.43; see also DRIESSEN, 1998, p.8). [48]

9.1 Photographic self-images and recurrence

"Recurrence" is the characteristic feature of memory. A past "happening" may only be for only a second or so, but subject still to frequent revisits and re-interpretation. An earlier seemingly inconsequential experience is recalled or repeated, or the mind "casts" back to what are taken as significant, "nodal" incidents (epiphanies, turning points). The latter are both meaningful and meaning-empty—as points of "recurrence" they are "localities of mystery" within life, used to apply "time" and "re-time" our experiences.35) [49]

Charles DICKENS, through the character "Pip" in "Great Expectations", gives a sense of how we reflect on the timing of past circumstances in an effort to make consistent sense of our life:

"That was a memorable day to me, for it made great changes in me. But it is the same with any life. Imagine one selected day struck out of it, and think how different its course would have been. Pause you who read this, and think for a moment of the long chain of iron or gold, of thorns or flowers, that would never have bound you, but for the formation of the first link on one memorable day" (in FRANK, 1984, p.154). [50]

Recurrence is a key aspect of looking at "auto/biographical photographic images" or portraits (by others) and self-portraits of ourselves—in a number of ways. [51]

Spontaneous recurrence is an involuntary, unconscious-to-conscious movement of a memory into thought, feeling and imagery: so "events, objects, relationships, emotions, and sensations may appear as if 'spontaneously' within the present consciousness although due to some clear association with elements" in contemporary life that is not (at least immediately) apparent (ROBERTS, 2003, p.17, 2004a). In looking at photographs, the whole or a part of the particular image might stimulate detailed memories and related sensual and emotional feelings. At its simplest, according to EDWARDS (following PROUST) there can be "voluntary" and "involuntary memory":

"Proust contrasted the inadequacy of 'voluntary memory', in which we consciously try to recall the past, to 'involuntary memory', which floods through us as a response to some unexpected stimulus. Voluntary memory, he felt, was always frustrated in its goal, whereas the unwilled memory could be more successful in capturing a moment of past time. For him, photographs provide a key stimulus for involuntary memory" (EDWARDS, 2006, p.121). [52]

9.1.2 Remembering as recurrence

This recurrence is the "function" of an active reminiscence—voluntary memory: "When did it happen?", "What did I do?", "Yes, I remember that too!", "That was an enjoyable occasion". Here is the "conscious thinking" about the past, brought into contemporary consciousness within possible interaction with others (ROBERTS, 2003, p.17, 2004a). [53]

We can say that spontaneous (Section 9.1.1) and voluntary memories (Section 9.1.2) provide necessary elements for narrative interpretations of life—they are likely to include more than linear time constructions and encourage some reflection. They can also set in motion further interpretive thought on previous experiences, perhaps a more imaginative manipulation of memory—a "return", a fuller "repetition", so as to "re-live; "re-story", "re-envision", "re-sensualise" and "re-enact"—to reconnect and re-invigorate what was an interest, a path, or a relationship that was ended or not fully pursued (see ROBERTS, 2004a):

"This type [of recurrence] takes two forms: firstly, a return to 'relive' specific events, relationships, experiences and objects which become 'nodal'—perceived as significant in life and subject to repeated recovery. Here there is a search for missed, hidden or alternative meanings—'truths' which can be uncovered. Secondly, there is the more manipulative re-envision, re-story and re-enactment which is not merely to find the 'clues' to past circumstances but to ask 'What if'—'Could things have been different if I had done that?' This is the 'fantasy' of the alternative life or lives" (2003, pp.17f.). [54]

By return as recurrence, the life trajectory can be perceived as if it could have taken another arc with a different set of experiences. While the operation of memory is obviously connected to the construction of the "past", its origin is in the "present", while also associated with the future. We rehearse future action—we can anticipate the likely success or failure of different projects. In addition, we also have a retrospective rehearsal—"What if I had made that decision?"; "Perhaps I could be doing that now"; "I could do that in the future" (ROBERTS, 2007, p.43; see SCHUTZ, 1972, p.103). These rehearsals are located in imagination and, its component, "fantasy". Some continuing, "creative fantasising" in life composition is vital for our sense of being and necessary to avoid the perils of obsession (over-repetition) and degeneration (or stasis) in life narrative (see FRANK, 1984). [55]

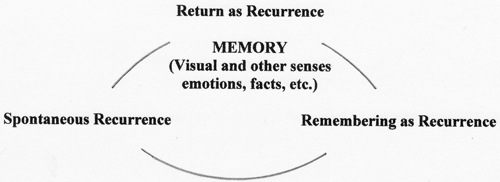

Illustration 6 outlines the types of "recurrence" in memory and indicates that one type can "lead" to another.

Illustration 6: Memory and types of recurrence [56]

Recurrence, in its various forms, brings a "re-consideration"—a pondering of what had or could have ("if only") occurred in our lives: regret and relief, happiness and sadness, tensions of secrets and lies, reaction to failures and successes, and so on.36) All these feelings may happen when we look at photographs of ourselves, say, as a child. The actions and decisions that were made (or could have been made) may be re-assessed, as perhaps perceived as if for the first time, and even in retrospect as having a major effect on our life path—or, alternatively, not so important after all in life's trajectory. Thus, in thought, possible actions and decisions can intrude and be pursued. Viewing photographic portraits can bring such a re-visualisation of events, re-wording of past conversations, re-enactment of actions, and re-sensualisation and re-emotionalisation of past experience to a greater or lesser degree—as previous or arising memories are reshaped and alternative life paths experiences imagined:

"Because it gives us a body with which to engage, the photographic portrait (perhaps especially if it is our own portrait) encourages us to attach to it via our own psychic past; it calls out for us to bring embodied experiences from our own past (whether repressed and 'forgotten' or easily called to mind) into dialogue with it in order to give this 'new' subject meaning within our own world view" (JONES, 2006, pp.54-5). [57]

10. Conclusion: Responses to Photographic Portraits

When looking at a photograph of self, a process of recognition (or mis-recognition) operates; the response to a self-image can be very varied—in part, depending on whether we already know that the image is of ourselves, because we may have taken it or have been told previously it is us (e.g., a picture as a child). If it has not been seen by us before, then we may soon recognise it as ourselves—as if a "reflection" (a "mirror") (see Section 5) or merely as we once were, even if the picture is from many years ago. But it may be that while the image is recognisable, visually as having been "me", is it "me" as I am? It may seem to represent a past self that is opaque, blurred, or even unrecoverable. Or I may see a picture of someone but I am not sure I can "re-cognise" who it is—is it really "me", and still as now? I try to "read" into the image but my attempt at "attachment" is fraught, I try to look "through" the surface of the picture (as though seeing the person through a "frosted glass" or "semi-transparent screen") to gain clarity and certainty through affective and other connections. The person shown in a picture may seem not to have much of (or any longer) a tie with us; we know it is a picture of us, as we attempt to look into or through the image, to construct a meaningful link but the tie eludes us. We want to "know" the person, but who they were escapes us. We ask "Who was I then?" and "What did I feel and think?" We look at the picture and the face looks back, not revealing its "secrets". However, we may see a photograph and have some partial recognition, we are not entirely sure but there are elements that are familiar (the image is interpretively like a "gauze" or "bead curtain"). If we could only "familiarise" those elements that are not fully recognised then, perhaps, the linkage between our present and the subject in the past would become apparent and established. Finally, the photographed person may seem a stranger to us or, at best, has some vague familiarity. The photograph here tends towards being a mere object, a record (a picture on an impervious "screen", as some unknown portrait on a wall, in a book, etc.). It is obviously a picture of someone and it may arouse some curiosity, like some historical document. Our memory is not able to place us in the position of the photographed subject, and helpful comments by others on the photographs may not be sufficient to enable recognition. The "photographic I" of the picture remains unconfirmed. [58]

A photograph can be said to "mediate", its surface seemingly lies between us and our previous self(ves). It appears that even when we "pictorially know" the image is of ourselves, and about our social relationships, the photograph can still exude some unfamiliarity and strangeness. We look at our portrait and the "self" in the picture stares back. Perhaps, the photograph as a "window" is of particular interest here: the glass can give our reflection—almost like a shadow—as we see our image on a surface. We can also see the image of ourselves as if beyond the surface, while still reflecting back at us. We see ourselves and our surroundings reflected in the surface and, at the same time, ourselves as part of the scene viewed through the window. The reflected image in a window can indicate to us the transitory nature of the self: as the light changes on the glass so does our image in sharpness and density of reflection, and just as it appeared it may, as readily, cease to exist. [59]

When we "pose" for a photograph—a portrait or self-portrait—we have in mind both a self we wish to "project" to others and one we wish to "protect" from an intrusive gaze. At the same time, there are pictorial limits to what an image can convey and, thereby, pass down as a legacy of the self. There is, then, a complex dynamic between the "pose" formed within the photograph and what can be discerned in the act of looking by the viewer:

"Through the pose, then, and this is where the productive tension of self portrait photography resides, the embodied subject is exposed as being also and at the same time a mask or screen, a site of projection and identification (themselves dynamics that are synaesthetic and embodied)" (JONES, 2006, p.50). [60]

Is there, then, a sense in the formation of the "pose", that we are not only protecting and projecting the self (or selves)—but also endeavouring to "preserve" a sense of self for future retrieval at later points through our memory, and leave a lasting legacy for others? The photographic portrait is, therefore, an "internal", "external" and an "eternal" document—to ourselves, to others, and to those to come.37) [61]

11. Epilogue: The Use of Photographic Portraits in Research38)

Until the early to mid 1980s, apart from a few examples, such as BECKER's well-known discussion of connections between photography and sociology (BECKER, 1974, 1982), an occasional research study (e.g. MARSDEN & DUFF, 1975), and an attempt to explore photography's relationship with the humanities (PARRY, MACNEIL & MACNEIL, 1977), there had been a dearth of social research interest in the employment of visual images. Today, in both sociology and anthropology, visual materials (photographs, film and video, etc.) are becoming essential components of research, publication and teaching. But, as part of this expanding interest, it would be worthwhile for social science researchers considering the use of photographs, to study more closely debates within photographic criticism and practice, for instance, surrounding both "traditional" and more contemporary photographic work in social documentary and portraiture. [62]