Volume 13, No. 3, Art. 6 – September 2012

Mirroring Voices of Mother, Daughter and Therapist in Anorexia Nervosa

Kathryn Weaver, Kristine Martin-McDonald & Judith Spiers

Abstract: The experiences of women with eating disorders and the meanings drawn from these experiences are largely hidden from health care professionals and thus are poorly represented in clinical and academic discourse. This study examined interpersonal relationships in the context of anorexia nervosa between an adolescent, her mother, and therapist revealed in their private and intimate diaries, letters, and reflections. Using narrative processes, we analyzed complex communication between the daughter and mother. The results reflected their written dialogue, represented their stories, and were validated by them. The core story, mirroring voices, documents the reciprocal processing of experiences and perceptions between the daughter and mother that facilitate the daughter's recovery. Six threads of mirroring voices include "being implicitly there for each other," "writing gives us voice," "centering on ourselves," "measuring up," "anorexic bitch," and "pain has a name." The findings suggest the use of similar strategies by the daughter and mother to manage the anorexia nervosa by recasting it as an intrusion requiring their united efforts. The major implication is that health professionals consider the mother-daughter interaction as a resource.

Key words: mother-daughter relationship; eating disorders; recovery

Table of Contents

1. Introduction

2. Background Literature

3. Study Purpose

4. Methodology

4.1 Data collection

4.2 The participants

4.3 Analysis

5. Results

5.1 Being implicitly there for each other

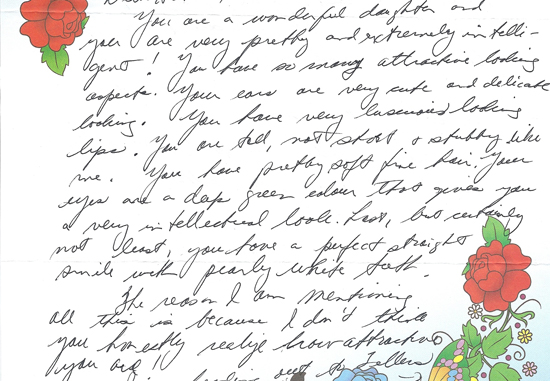

5.2 Writing gives us voice

5.3 Centering ourselves

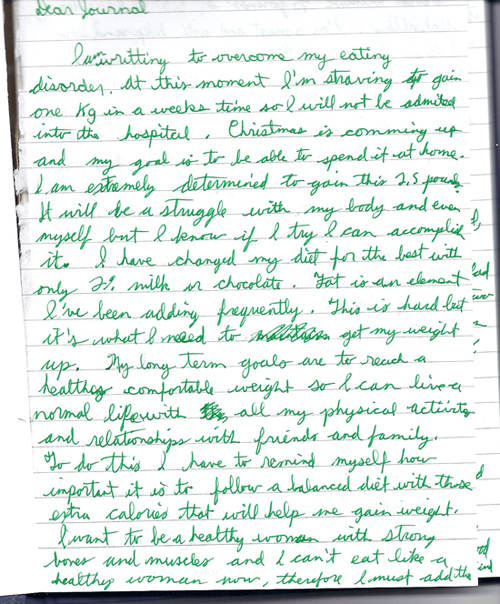

5.4 Measuring up

5.5 "Anorexic bitch"

5.6 Pain has a name

6. Discussion

7. Implications

8. Conclusion

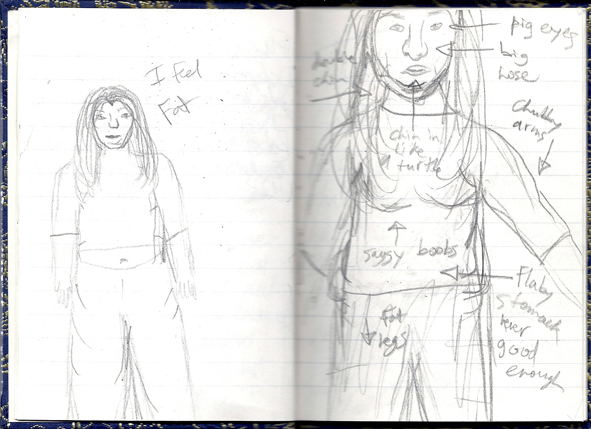

"Life

Like ice on the road

You never know

What part will cause you to slip.

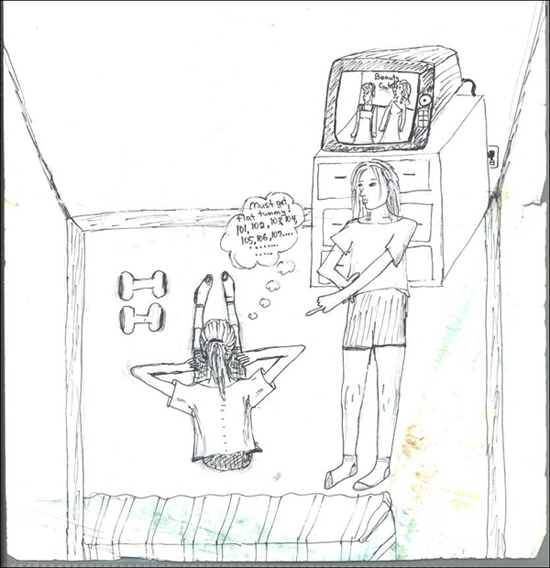

Either we journey on

Deal with the ups and downs,

Or out of fear of falling

We stay inside" (Daughter's Journal [DJ], entry dated March 5, 2003).

The health consequences and high cost of treatment associated with eating disorders can be overwhelming; and thus, it is critical that the perspectives of those most affected be represented in developing knowledge upon which to inform supportive clinical intervention. To this end, we began to analyze key ideas that threaded through the serial texts of greeting cards and daily letters written by a mother to her daughter hospitalized with anorexia nervosa, the stories of the daughter conveyed throughout her diaries and drawings, and reflections by the daughter's therapist. These ideas and threads would reveal the meaning of the eating disorder to the mother and daughter and the managing processes they use to effect recovery. Such analysis of the mother-daughter interaction enables their stories to be heard, providing a more comprehensive rendering than that conveyed in available individual accounts of eating disorders and recovery. After describing our study rationale, purpose and the approach taken toward data collection and analysis, we introduce the participants themselves. Our findings are presented as coalescing narrative threads that can help practitioners and policy makers better understand and support individuals and families. [1]

Much of our knowledge about living with anorexia nervosa has been developed from researcher-driven data collection and analysis processes which convey the experiences of those affected from the perspectives of clinicians and academics. Such investigation has often condensed understanding of the eating disorder to discrete physical and psychological responses of individuals that are measurable against professional expectations which include assessment and diagnostic criteria (DELLAVA, THORNTON, LICHTENSTEIN, PEDERSEN & BULIK, 2011; HENDERSON et al., 2010); eating attitudes, behavioral traits and psychopathology (JACOBS et al., 2009; JENNINGS, FORBES, McDERMOTT, HULSE & JUNIPER, 2006; McCOMB, CHERRY & ROMELL, 2003); motivation toward behavior change (BRUG et al., 2005; SULLIVAN & TERRIS, 2001); and physical activity and dietary practices (BEWELL-WEISS & CARTER, 2010; JONAT & BIRMINGHAM, 2004; SCHEBENDACH et al., 2011). Similarly, research focusing on the family responses has, for the most part, isolated characteristics (e.g., parental concern, perfectionism and attachment) that influence (EVANS & WERTHEIM, 2005; SHOEBRIDGE & GOWERS, 2000; SOENENS et al., 2008) or are influenced by (ESPINA, OCHOA DE ALDA & ORTEGO, 2003; GILBERT, SHAW & NOTAR, 2000; SIM et al., 2009) the development of the eating disorder. The application of sociological and feminist theories has permitted examination of the role of social expectations on personal values, thus extending understanding of eating disorders from individual and family explanations to expressions of social and political vulnerability and inequality (BANKS, 1992; SZEKELY, 1989). Such investigations reflect the complexity of lived experiences and have put forward a view of anorexia nervosa as a source of comfort (WEAVER, WUEST & CILISKA, 2005) and strength (GARRETT, 1996); recovery turning points are identified as finding self (WEAVER et al., 2005), choosing between life and death (GARRETT, 1996, 1997), no longer doing what others expect (MUKAI, 1989), "truthful self nurturing" (KEARNEY, 1999) and becoming "real" (BERESIN, GORDON & HERZOG, 1989; LAMOUREUX & BOTTORFF, 2005). [2]

In addition to investigations by clinician and academic professionals, lay accounts have described eating disorders as a means for self-improvement and recovery as maturing and learning to trust in self and others (POPPINK, 2011; THORNTON, 2007). While both professional and lay publications reveal complex struggles within specific social contexts, they do not adequately provide the perspectives of the therapist providing care and services. We could locate no research integrating the intense contributions of therapists in caring for eating disordered persons and families. Throughout the available literature, the therapist is usually an investigator administering interviews or surveys to participants with eating disorders, or the therapist is a consumer reflecting upon the personal experience of having an eating disorder. Discrete aspects of the therapeutic alliance, for example the bond between therapist and client (TERENO, SOARES, MARTINS, CELANI & SAMPAIO, 2008) and the impact of the client's body mass index on the therapist (TOMAN, 2002), have begun to be examined in the context of eating disorders; and yet, the overall therapeutic alliance has been poorly explored (TERENO et al., 2008). We believe research combining experiences of therapists with those of persons affected by eating disorders may contribute to richer understanding of how individuals, families, and societies construct and resist eating disorders. Therefore, we accompany our exploration of the meaning of anorexia nervosa and recovery for a teenaged daughter and her mother with reflections from her therapist. In doing so, we position the mother-daughter narrative to inform and stand alongside dominant clinical narratives. [3]

We set out to understand individual, family, and social meanings and constructions of eating disorders from the perspectives of those most affected. This study was part of a larger project wherein we explored the meaning of eating disorders through analyzing the diaries of women living with anorexia nervosa (self-starvation), bulimia nervosa (cycle of binge eating and purging) or binge eating disorder (episodes of uncontrolled eating without attempting to compensate for weight gain). The availability of in-depth accounts prepared by one participant, her mother and therapist allowed us to extend an aspect of our original study to uncover complex concurrent meanings for the daughter, mother and therapist. The study objective was to comprehend and give voice to the experiences of these three women. [4]

A narrative approach to research was chosen to enable access to individual meanings and to a rationalized representation of complex, dynamic processes that have altered over time and under varying circumstances (BRUNER, 1987). People construct narratives not simply to recount events but to produce knowledge and shape experiences of events in ways that are significant and logical for them and their audience (DENZIN, 1989). Narratives allow people to alter the direction of their lives (FRANK, 1995). By providing space for others for their voices to be heard, narrative research can yield insight into intentions and behaviors that can be useful in understanding situations arising in clinical settings and everyday lives. [5]

The data in this study included unsolicited diaries and art work by an adolescent during a three year period and letters from her mother during the daughter's second hospitalization for treatment of anorexia nervosa. These writings were intimate, written for self or daughter, and clearly not prepared for a research project. The data consisted of nine journals, 51 original poems, and three drawings from the daughter; 79 letters and 87 commercial cards by her mother; and also 6 recorded reflections from the therapist. The first author obtained appropriate institutional ethical approval and consent from the participants to include their communications in the study before proceeding with the analysis. All data were transcribed and anonymized. No names are used and some details have been altered to protect the anonymity of the family. [6]

The daughter, a 15 year old grade 10 student, began journaling in November, 2000, a month before her first admission for treatment of anorexia nervosa. At 174 cm and 41.8 kg, she did not agree she looked emaciated. She was hospitalized for four months, home for one month, and re-hospitalized at an admission weight of 39.9 kg for another 4 months. She described being "all out of whack and on a heart monitor with a heart rate of 35-45." She was discharged from the second hospitalization September 2001 at 60 kg and experienced recovery as an on-going journey for the next several years. [7]

The mother, a full-time high school teacher, was the primary care-giver in the family comprising her husband, the daughter with the eating disorder, two older daughters, and herself. The mother and father interacted with the treatment team social worker during the daughter's hospitalizations. [8]

The therapist, a nurse psychotherapist specializing in eating disorders, had met with the daughter prior to the first admission, worked with her during the second hospitalization, and provided follow-up outpatient therapy. The therapist was alarmed by the daughter's emaciation, grey skin color, cyanotic (bluish) nail beds, bradycardia (slow heart rate), and chapped cold hands. The therapist maintained monthly contact with the parents through their attending a community support group for eating disorders. The therapist consented to sharing her written and verbal reflections about her work with the daughter and interactions with the mother following their verbal, audio-recorded consent. [9]

In keeping with the narrative approach described by EMDEN (1998), the written texts (daughter's diaries, mother's letters and therapist's reflections) were read several times to grasp content, retain key ideas, and produce stories. Each member of our research team took responsibility for in-depth immersion in and representation of the texts of one participant to the rest of the team. This maximized our expertise, fostered synergistic dialogue and championed each participant. We created individual stories for the daughter and mother, and a coherent core story representing their relationship with each other and the therapist. Verbatim quotes, edited for clarity, formed the basics of the stories. Narrative threads were identified based on recurrence (ideas that have the same meaning but different wording), repetition (the existence of the same ideas using the same wording), and grab of the ideas within the stories. These threads were examined to generate meanings about the participants' experiences and perceptions. [10]

As a research team, we were struck by the comparable motivations and behavioral responses of the daughter and her mother that occurred at every narrative thread. We perceived the mother-daughter team's responses as protecting and enhancing each other through parallel strategies that involved intentional presencing, writing, relationship and esteem building, pathologizing the anorexia nervosa but not the daughter, and expressing underlying pain and negative feelings. The responses of the mother were contrived to foster self-esteem in the daughter by mirroring back to the daughter a sense of worth, intended to create self-respect, self-assertion, competence, security, as well as comfort in the unfamiliar hospital setting. Mirroring needs of the daughter included her need to be admired for her own qualities and accomplishments. According to psychoanalyst KOHUT (1984), mirroring is a process of employing accurate empathy, i.e. knowing and absorbing what the other person (usually the child) is feeling, communicating back recognition and acceptance of this, and doing something about it. Being mirrored refers "to all the transactions characterizing the mother-child relationship, including ... constancy, nurturance, a general empathy and respect" (KOHUT, 1977, pp.146-147). KOHUT (1977) further uses the term "mirror transference" to describe the developmentally arrested patient experiencing the therapist's empathy and bonding as part of the patient herself. [11]

We rechecked the stories and threads of mirroring voices by returning to the full texts and by taking them back to the participants. The mother and daughter, interviewed separately, expressed appreciation of each other's willingness to benefit others through the telling of their stories. Neither mentioned any surprise upon reading the core story integrating the voices of daughter, mother and therapist. The mother initially did not want to include negative comments from the daughter concerning the father, saying "[i]t really was not that bad ... Every family has some difficulties to work out. We [mother and father] do get on well together" (Interview with the mother while taking the stories and threads back to her). However, the mother permitted the content to be included because she believed it to be important to her daughter's recovery. The daughter volunteered having greater understanding and acceptance of her mother's career and care-giving obligations. The therapist agreed with the researchers' interpretation, recommending its dissemination to patients, families, and counselors in similar contexts. [12]

The core story of mirroring voices is a processing and sharing of similar values, attitudes, and behaviors between the daughter and mother. The component threads of the core story—"being implicitly there for each other," "writing gives us voice," "centering on ourselves," "measuring up," "anorexic bitch," and "pain has a name"—are enhanced by the therapist's reflections. [13]

5.1 Being implicitly there for each other

The relationship between the daughter and mother was characterized by mutual support, protection, and admiration. To the daughter, her mother was "the best mother in the world." The daughter described being exceptionally cared for by her mother. This experience was positive in that it sheltered the daughter from loneliness; it was negative in that it evoked ridicule by her sisters and father:

"I was 2½ or so I imagine. I was thought to be the classic baby sibling or so they thought. Alone in my room, crying to get company, I hated sleeping alone. I feared what was to come. My mother cared for me like a princess and I developed an admiration for her, the woman who stuck by me. I'd cry until she came and lay until I fell asleep. This behavior likely started my spoiled brat persona. I did not understand the label which dismissed and minimized me. I was just a scared innocent young child" (DJ 03). [14]

According to the mother, the daughter was pretty, talented, and intelligent (see Illustration 1). The mother conveyed her admiration of the daughter in letters pointing out the daughter's endowments and abilities. The mother identified that the daughter had been teased at an early age by classmates and siblings about appearance (wearing glasses, being chubby) and shyness. During this period in the daughter's life, the mother commuted and worked long hours (ten hours/day, six days/week) and had not consistently been "there" for the daughter. Because the mother believed the daughter saw herself in a negative way, the mother intended to help the daughter build positive self-perception through reinforcing her strengths.

"You have many talents that many do not have. You are extremely intelligent, artistic, caring and pragmatic. Before your physical health was compromised by your anorexia, you have always had a healthy athletic body that allowed you to learn many physical activities. I know throughout your short life you learned how to do more things than many people do not do in their entire life-time. I am so glad to have such a bright girl like you for a daughter. I love you, Daughter. I will do anything for you and I am there for you whenever and however you need us. I hope you sleep well tonight. Love, Mom" (Letter from Mom [LM] 24)

Illustration 1: Letter from mother to daughter (LM 49) [15]

The therapist described a strong positive bond between the daughter and mother but not between the daughter and the other family members. The daughter spent little time with her father whom she considered abusive toward her mother. The daughter described her older sisters as not having prolonged closeness with the mother for they often sided with the father in downgrading the mother. The daughter identified that crying for her mother at bedtime as a young child served to keep her mother at her bedside and thus protect her mother from her father's abuse. In this way, the daughter and her mother were unconditionally "there" for each other in their family life. They were also geographically there for each other when the daughter attended the high school where her mother taught. Neither considered this a problem because "[i]t's not like I am in her homeroom or take classes with her" (Daughter Interview). The therapist observed the daughter and mother to often sit in silence in the daughter's hospital room, the mother smiling as she watched the daughter do the artwork or homework that the mother transported between the school and the hospital. The therapist believed the daughter and mother were comfortable and accepting of each other with minimal verbal communication. [16]

The daughter described herself as having limited self-esteem without the right to express herself freely. Across the pages of her various journals, she wrote in different colored inks and tones, in places scribbling over words or writing faintly to reduce legibility. She explained that she had sometimes written under the covers at night while in the hospital to prevent others from seeing. Her journals contained original drawings and poetry which enabled her to express her feelings, perceptions, and other private communication.

"Dear Journal, I am writing to you because I need to express myself ..." (DJ 01).

"Dear Journal, I am writing to overcome my eating disorder" (DJ 01 [Illustration 2]).

"Today I bought this journal because I feel as though I'm not being heard. By writing in this I can remember my feelings and be able to discuss them if necessary or if I have enough guts. I'm anorexic. I was not always. I did not ask for it and some day I will write the opposite. That some day is far away and to imagine me without this image with traits is extremely difficult. However I'm trying ... I am confused about everything" (DJ 02).

Illustration 2: Entry for the daughter's journal (DJ 01) [17]

The mother wrote at least daily to the daughter, excessively detailing everyday happenings and pledging absolute love and support. These letters were placed inside commercial cards and stored in a fabric covered box on the daughter's night stand.

"Thank you for the letter you gave me last night. I agree with you. It is so much easier to communicate in pen and paper than by word. I think this is mainly because you take time to consider what you are going to write, but when you say something, often you think about it after you have said it and realize that it was the wrong thing to say. Unfortunately, you cannot crumble up what you have said or scratch it out. There are so many times in my life when I have said something that I wish I could have been able to rewind and erase. The urgency to say something has always got in my way in producing healthy instructive comments" (LM 4). [18]

The therapist recalled the daughter bringing a heavy canvas bag to each therapy session, unbuckling the bag, taking out a journal or scrap of paper, wrinkling up her nose while struggling to decipher her writing, reading what she intended, and returning it to the bag. On several occasions, the daughter asked the therapist to write in the daughter's journals to remind the daughter of what would happen if she did not eat or continued to exercise. The daughter referred to the therapist's written responses to help her tolerate negative affects and aloneness between sessions. The therapist received letters from the mother via the daughter's canvas bag. These letters contained requests for sorting out the daughter's diet and activity. The therapist often mediated between the texts of the two women when their verbal communication, fraught with fear of not saying the right words or of losing control of a situation by saying the wrong word, did not serve their needs. [19]

The daughter and mother focused on self and each other and actively filtered who they permitted into their relational space. In keeping others out, they formed an exclusive unit. This served to protect their relationship from which each drew validation. For example, writing of her disdain for the other girls enabled the daughter to externalize her own struggle with perfectionism:

"I hate the other girls ... one always brings up that I'm exercising ... the reason that I exercise is so I'll still be toned. She shouldn't be telling me what to do when she's way worse off than me. I don't have to take pills so I won't throw up. I never overeat and I don't have a weight issue in my family like her. ... That other girl pisses me off because she acts like she's so perfect. I wish she'd just accept that she's going to be a healthy person and get over it. You have to be like that if the only way you can keep weight off is by binging and purging, you are pretty pathetic" (DJ 05). [20]

The mother interspersed her concern for the daughter amid detailed accounts of incidents occurring at home and at school. The mother acknowledged the strangeness of writing to the daughter "when I have already visited you twice today and ate supper with you" (LM 24). Although she worried that her daughter would find the letters redundant, the mother continued to send daily cards and letters.

"After I finished the car wash stuff, I took the money up to the school. Next I went home & dusted, cleaned the upstairs bathroom and vacuumed. After that I did some laundry and then you were home with your dad. Life is not the same around here without you, dear. I hope you didn't tire yourself out too much playing basketball, even though it was a very short time. We all want you to recover from your anorexia so you can lead the happy life that you so deserve" (LM 8). [21]

The therapist believed the therapeutic alliance was critical to recovery, and the process of therapy naturally egocentric. She explored difficulties the daughter was having in her peer interactions and worked with the daughter to help her express her opinions and process responses to other eating disordered patients and treatment team members. There had been episodes of the daughter being excluded from the conversations of the other patients and, on one occasion, the daughter returned from an evening pass to find a layer of ice cubes hidden under the top sheet of her bed. The therapist assisted the daughter to articulate concerns in such a way that others could comprehend and the daughter could come to terms with her quandaries and vulnerabilities. Empathy, comfort, and reassurance on the part of the therapist enabled the daughter to feel understood. Although the daughter's positive relationship with her mother helped to sustain her during difficult times, the daughter did not consider her mother a good role model for she saw her mother's role as subservient and as victim within the family. In the follow-up interview to validate the researchers' interpretation, the mother acknowledged a history of being agreeable to others and tendency towards passivity. Over the course of therapy, the daughter worked to develop assertiveness, self-advocacy, and problem solving skills. [22]

Measuring up enabled the daughter and mother to maintain their exclusive relationship as others did not measure up to their standards. In addition, measuring up allowed the daughter to justify and maintain anorexic behaviors. By labeling herself as "never good enough," a "fat loser" with a "double chin," "saggy boobs," "chubby arms," "fat legs," and "flabby stomach" (DJ 07, Illustration 3), she perpetuated rigorous dieting, exercising and self-vigilance.

"I'm as close to a perfectionist as it gets. I have high standards for myself and low for others ... I'm really afraid to have a fat stomach and sides and a double chin. I want a small tight butt and firm legs. I don't really think I have any good physical qualities and I constantly feel others are superior to me. People sometimes seem to acknowledge me but I don't let myself realize it or hear it" (DJ 06).

Illustration 3: Measuring up sketch located in the daughter's journal (DJ 02) [23]

The daughter had not internalized a realistic measure for self-worth but rather she evaluated herself solely on physical appearance. She was aware of the limitation of basing self-worth on appearance and rebuked herself for measuring this way.

"Take away the clothes, pretty hair and color.

Take away the flesh and all possessions.

A core is left within which defines the being.

Many never see this, blinded by an image.

What will become of us?

Rewarded for shallowness

Small words flourish

As others become lost souls.

I see the inner core

The thoughts, beliefs, and emotions.

This is how I base their words

Yet, when self-applied, I fail" (DJ 04). [24]

To facilitate her daughter developing a more positive self-perception not based on physical image, the mother proclaimed the daughter as brilliant and excellent. The mother tried to help the daughter recognize and integrate her academic and artistic talents through measuring the daughter against extraordinary standards and pointing out the daughter's successes beyond the physical dimension.

"This card is a yellow house by Van Gogh. It seems to have a great deal of detail. You could paint a picture as good as or better than this. This is my opinion but you certainly have a lot of potential in art.

I want you to be able to open your mind to what can be in store for you. You have one of the finest intellectual abilities I have seen at your young age. You also have extremely talented creative skills. Most people I have met have one or the other—not both. To me, you would probably be considered a type of genius because you have strong abilities in all of your multiple intelligences. It is a terrible waste when your anorexia is trying to trick you into believing you are not succeeding" (LM 61). [25]

The therapist recognized the measuring up criteria used by the daughter and mother as similar and unrealistic. The therapist assisted the daughter to challenge internalized appearance standards by helping her identify and value functional accomplishments rather than impossible appearance ideals. For example, the therapist helped the daughter differentiate between perceiving her body as object (e.g., for admiring) and perceiving her body as process (e.g., needing strong legs for walking). While the mother had tried to focus on the daughter's performance, the therapist helped bridge the abstract, future-oriented standards of excellence used by the mother with more concrete, immediate measures an adolescent daughter could consider. [26]

Upon the therapist's request, the daughter created the metaphor of the fearsome anorexic bitch as a distinct external entity (see Illustration 4). This enabled the daughter to be perceived as vulnerable and the anorexic bitch as the problem.

"I want to do things I like, not what she likes" (DJ 05).

"Shut up bitch! Shut the fuck up! I don't think it will matter if I chuck [vomit] again. I can chuck and such and eat less but how will this get me anywhere?" (DJ 05)

"I only hurt. I want to be productive, dreams are there. She [anorexic bitch] smoothers them. I'm too scared to stand up. Not right now" (DJ 08).

"Don't eat,

Must exercise,

Stomach will get fat,

Hospital may be only answer,

DIE BITCH!" (DJ 07)

Illustration 4: "Anorexic Bitch" drawing located in the daughter's journal (DJ 13) [27]

The mother tried to soothe her daughter with loving words while also casting the anorexic bitch as an unwanted, destructive intrusion in their lives.

"You want to be released from the shackles of this disorder and no longer be a slave to it. It has destroyed so much of your life by not allowing you to do the very things you used to love to do like playing sports, enjoying a movies with friends, going to dances, and being part of your peer group" (LM 11).

"You must realize that everyone who cares about fighting your anorexic habits all have one goal in sight for the future. That is, for you to be a healthy young woman who can go on with her life in a normal manner—to finish school, go to college, become independent, have a career, perhaps a family. None of us want you to remain hospitalized for a long time without any success. Or to be continually at the mercy of your anorexia, the only thing preventing you from having a happy, normal future" (LM 40). [28]

In her practice, the therapist encouraged clients to separate from the eating disorder. Drawing the "anorexic bitch" (Illustration 4) helped the daughter articulate the influence of the eating disorder. To the therapist, the daughter described herself looking down upon the force screaming at her and controlling her thinking and behavior, including excessive exercising. The daughter explained that she must exercise to the point of being able to feel each vertebra "bump" along her spine. The daughter added that although she had drawn a beauty pageant on the television screen, she confided she was not watching the pageant as the anorexic bitch was demanding her supreme effort and obedience. The daughter added that having the television tuned in to the pageant helped keep the treatment team "off my case" for they assumed they knew the underpinnings of the eating disorder as the daughter "just wanting to look like a star." [29]

The daughter and mother did not openly communicate their suffering. Yet, as readers of their journals and letters, we were engulfed by the palpable experiences of their pain. The daughter's narratives are of feeling hurt, afraid, hopeless, powerless, controlled, lonely, and rejected.

"I feel scared

Scared of failing

Scared of succeeding

Scared of expectation

I want to change my life ...

I'm in a cage controlled by another so very close to me

Why won't someone set me free?

They see me struggle

Try to aid

But the key is hidden within

I just have to find it ...

But once I'm free

I'll be me

Dreams that seemed so far away

Will be accomplished and new ones put in place

I succeed and practice me

The flesh and fat

Is my pain

Looking at it I feel hopeless

Nothing else matters" (DJ 08). [30]

The mother's pain was stress and guilt. In maintaining the little princess image of her daughter, she had not recognized her daughter's current needs and difficulties. The mother described feeling guilty and berated herself for not perceiving her daughter as "shy" (LM 54), "not ready" to take her driving test (LM 71), and having outgrown "old [preadmission] clothes" (LM 51) and bedroom furniture which was "fit for about a 3-8 year old because it's so low to the floor" (LM 16).

"I can understand why you come across as angry and you take it out on us. This is not to say that you are always angry, but you get very impatient with us and are ready to kick our butts. When you feel this way, just remember that we are not very young and 'hip' or 'cool.' We are two middle-aged very stressed parents who are doing everything in our power to help you recover. At times we do and say things that we shouldn't because we are just bumbling, stumbling, old fools who just love you to bits!" (LM 64) [31]

The daughter's reference to being in a cage controlled by another conveyed her relationship with her father who she described as domineering and controlling. In their work together, the therapist helped the daughter identify and address issues of identity, intimacy, abandonment, resistance, boundaries, and interpretation. The daughter subsequently worked through the pain of her adolescent developmental transitions and other negative life events including discussing career uncertainties and grieving the death of a friend. The daughter ultimately developed self-care capacity which enabled her to leave her parents' home and pursue a career in the health professions. [32]

In this article, we analyzed and represented the stories of an adolescent daughter with anorexia nervosa, her mother, and her therapist. The daughter first became aware of experiencing pain when she was 2.5 years old. She had witnessed her mother being abused by her father. The development of a close relationship with her mother helped the daughter manage the pain by protecting her mother to some degree from the abuse; yet, this closeness to her mother stigmatized her by other family members. The mother-daughter relationship developed from being there for each other and was maintained via written communication, self-centering, and measuring up to stringent exclusive performance and appearance criteria. [33]

To the daughter, "the flesh and fat is my pain," a pain ravaging her to the point that "nothing else matters." Her use of the language of fat enabled her to address her difficulties through strenuous dieting and exercising. Translating situational and developmental concerns into "feeling fat" is socially acceptable for females (FRIEDMAN, 1997; MARTIN, 2007) and allows the body to serve as a vehicle for expressing distress as well as for bringing about desired change (LEAVITT & HART, 1991; LESTER, 1997). Clinical labels of "body image distortion," "body image disturbance," or "fat phobia" do not adequately convey the daughter's sense of hopelessness associated with her pain and with the peril of feeling controlled by an eating disorder. The labels limit the grasp of the daughter's inner turmoil, pathologizing and distancing her from her lived experience and meaning. [34]

Our finding of mirroring voices portrays a reciprocal iterative process between the mother and daughter that is not put forward in all too frequent narratives which tend to fault mothers for projecting their own difficulties onto their daughters (BENNINGHOVEN, TETCH, KUNZENDORF & JANTSCHEK, 2007; PRESCOTT & LePOIRE, 2002) and family members for enmeshing, overprotecting and distancing (DANCYGER, FORNARI, SCIONTI, WISOTSKY & SUNDAY, 2005; HUMPHREY, 1989). These dominant narratives continue despite findings of no pathology in mother-anorexic daughter relationships (COOK-DARZENS, DOYEN, FALISSARD & MOUREN, 2005; GARFINKEL, GARNER, & ROSE, 1983; VIDOVIC, JURESA, BEGOVAC, MAHNIK & TOCILJ, 2005) and findings portraying family dysfunction as a consequence rather than a cause of the eating disorder (ESPINA et al., 2003; HILLEGE, BEALE & McMASTER, 2006; LATTIMORE, WAGNER & GOWERS, 2000). Our finding of mirroring voices also does not account for causality. Instead, the finding conveys a structuring of maternal efforts to strengthen the daughter through validating her accomplishments and gifts, keeping her informed and included in the family, and encouraging her to resist the influence of the "anorexic bitch." [35]

This finding of daughter and mother actively disparaging and challenging the eating disorder contrasts with the narratives of HUGHES and HUGHES (2004) wherein HUGHES (the daughter) abandoned her "thin, tortured"(p.260) body and was not joined in the recovery effort by her mother. In our study, the daughter did not on her own abandon her anorexic self; rather, she and her mother confronted it in a united front. Together daughter and mother constructed the anorexia nervosa as an external identity, separate to the daughter and separate to their relationship with each other. In this way, the eating disorder was categorized as an enemy justifying their unified effort to face and resist. It is further possible that this strategy subtly allowed the mother and daughter to externalize issues of control in their tightly bonded relationship. Validating the daughter's rebellion against a common enemy served to decrease tension between mother and daughter. [36]

It was not possible to infer from the mother's letters if her high level of concern predated the onset of her daughter's eating disorder or if she experienced powerlessness in relating to her husband. Thus, our findings do not explicitly support extant explanations of parental high concern (SHOEBRIDGE & GOWERS, 2000) and powerlessness or helplessness on the part of mothers (MA & CHAN, 2003). The mother validated having a "soft spot" for her youngest daughter who had encountered peer and sibling harassment. Our finding of mirroring voices resonates with the contemporary view of anorexia nervosa described by KORB (1994) as a developmental crisis in the context of a loving close mother-daughter relationship. At the same time, however, the conspiratorial and collegial tone of the mother's letters exemplifies the "complex contradictory communications" style reported in HUMPHREY (1989, p.213) and other eating disorder family research. Further research may allow us to better understand the influence of the mother-daughter communication and relationship on eating disorder development and recovery. [37]

In this study, the voices of daughter, mother and therapist have come together to recount a time-bounded event in the lives of the three women. These narrative data are unique in their variety, richness, and origin. They provide multiple perspectives outside dominant medicalization of the human problem as anorexia nervosa and recovery. The diaries, letters and reflections were not artifacts of a research process and therefore were not influenced by the research process which, according to ALASZEWSKI (2006), may confer "special authenticity ... [as] diarists are under pressure to write an honest and accurate account ... telling it as it is or was and not only recounting the events but also the feelings associated with those events" (pp.47-48). The task to render authentic accounts has carried forward from religious motivations to have a relationship with God and from psychoanalytical motivations to monitor personal struggle and self-development (ALASZEWSKI, 2006). [38]

Nevertheless, we were conscious of the potential for distortion arising from using diaries as a source of knowledge in a research project given our observations of the many scribbled over, crossed out, and written over areas throughout the daughter's journals. Because diaries are not straight-forward records of experiences but imaginative, reworked, edited constructions that make it possible to review and re-examine experiences (ALASZEWSKI, 2006; CHARMAZ, 1999), we carefully attended to issues of rigor. We developed the core story and the threads used to interpret the realities represented within the texts through in-depth examination and comparison with each other. Rigor was enhanced through the availability of multiple documents from each participant, triangulation of the adolescent daughter's diaries and mother's letters with the therapist's reflections which all intersected the same time period, and follow up interviews with the daughter and mother. The daughter and mother validated that the results reflected their written dialogue and represented their stories. [39]

The findings aid understanding of how anorexia nervosa has been experienced and described within a specific daughter-mother dyad, and can provide insight into the decisions and behaviors that enable women to manage encounters with eating disorders. The diaries and letters were hitherto not revealed to health care professionals including the therapist. Thus the study adds the voices of women personally affected by anorexia nervosa to empirical literature and disciplinary knowledge. Vividly illuminated are the pain and peril of feeling shy, hopeless, scared, ignored, and ridiculed on the part of the daughter, and of overwhelming commitment and concern by her mother. The narrative approach allowed us to integrate the voices of the daughter, mother, and therapist. These voices which underscore the recovery process must ultimately guide responsive person-led care interventions. [40]

The combined perspectives of daughter, mother, and therapist offer a more comprehensive rendering than that conveyed in available individual accounts of eating disorders and recovery. In the core story of mirroring voices, the eating disorder served a protective function and was eventually resisted by recasting it as an objective external identity, an enemy requiring a unified team effort. The mother-daughter interaction thus provided a critical piece of the puzzle of anorexia nervosa and recovery. As mothers are often the primary care-givers for adolescent daughters across the duration of the eating disorder, it is critical to understand their experiences and the meanings they construct of these experiences in the context of caring for their daughters within the health care delivery system. Practitioners and policy makers might better support individuals and families affected by eating disorders by hearing their stories. [41]

Narrative forms are a legitimate way of understanding meaning and how it is created. A narrative approach provided a space for the voices of a teenaged daughter, her mother, and her therapist to be heard. The core narrative of mirroring voices portrays mother and daughter as united in effort to overcome the eating disorder. We have brought forward their narrative to stand alongside traditional academic and clinical narratives. [42]

In conclusion, we offer the daughter's words written 11 years after her first journal entry:

"That day I heard those two dreadful words [anorexia nervosa]

Is a day I hate to recall

But that day lead me to incredible strength.

I now know who I am,

where I stand,

and what I value.

I now care for others

I am far from perfect but

I am special" (Daughter, June 9, 2011). [43]

We are grateful to the daughter, mother, and therapist who consented to interviews and donated their diaries, letters and reflections to the analysis. We wish to thank the following for their support of this project: Alberta Heritage Fund for Medical Research; CIHR Strategic Training in Health Research (the EQUIPP Program), International Institute for Qualitative Methodology, University of Alberta; University of New Brunswick; Society for Assisted Recovery from Eating Disorders, Edmonton, Alberta.

Alaszewski, Andy (2006). Diaries as a source of suffering narratives: A critical commentary. Health, Risk & Society, 8(1), 43-58.

Banks, Carolise Giles (1992). "Culture" in culture-bound syndromes: The case of anorexia nervosa. Social Science Medicine, 34(8), 867-884.

Benninghoven, Dieter; Tetsch, Nina; Kunzendorf, Sebastian & Jantschek, Günter (2007). Body image in patients with eating disorders and their mothers, and the role of family functioning. Comprehensive Psychiatry, 48, 118-123.

Beresin, Eugene Victor; Gordon, Christopher & Herzog, David B. (1989). The process of recovering from anorexia nervosa. In Jules R. Bemporad & David B. Herzog (Eds.), Psychoanalysis and eating disorders (pp.103-130). New York: Guilford.

Bewell-Weiss, Carmen V. & Carter, Jacqueline C. (2010). Predictors of excessive exercise in anorexia nervosa. Comprehensive Psychiatry, 51, 566-571.

Brug, Johannes; Conner, Mark; Harré, Niki; Kremers, Stef; McKellar, Susan & Whitelaw, Sandy (2005). The transtheoretical model and stages of change: A critique. Observations by five commentators on the paper by J. Adams and M. White (2004) Why don't stage-based activity promotion interventions work? Health Education Research, 20(2), 244-258.

Bruner, Jerome (1987). Life as narrative. Social Research, 54, 11-32.

Charmaz, Kathy (1999). Stories of suffering: Subjective tales and research narratives. Qualitative Health Research, 9, 362-382.

Cook-Darrzens, Solange; Doyen, Catherine; Falissard, Bruno & Mouren, Mary-Christine (2005). Self-perceived family functioning in 40 French families of anorexic adolescents: Implications for therapy. European Eating Disorders Review, 13, 223-236.

Dancyger, Ida; Fornari, Victor; Scionti, Lisa; Wisotsky, Willo & Sunday, Suzanne (2005). Do daughters with eating disorders agree with their parents' perception of family functioning? Comprehensive Psychiatry, 46, 135-139.

Dellava, Jocilyn E.; Thornton, Laura M.; Lichtenstein, Paul; Pedersen, Nancy L. & Bulik, Cynthia M. (2011). Impact of broadening definitions of anorexia nervosa on sample characteristics. Journal of Psychiatric Research, 45, 691-698.

Denzin, Norman K. (1989). Interpretive interactionism. Newbury Park, CA: Sage.

Emden, Carolyn (1998). Conducting a narrative analysis. Collegian, 5(3), 34-39.

Espina, Alberto; Ochoa de Alda, Ifiigo & Ortego, Asuncion (2003). Dyadic adjustment in parents of daughters with an eating disorder. European Eating Disorders Review, 11, 349-362.

Evans, Lynette & Wertheim, Eleanor (2005). Attachment styles in adult intimate relationships: Comparing women with bulimia nervosa symptoms, women with depression and Women with no clinical symptoms. European Eating Disorders Review, 13, 285-293.

Frank, Arthur (1995). The wounded storyteller: Body, illness, and ethics. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press.

Friedman, Sandra (1997). When girls feel fat: Helping girls through adolescence. Toronto, ON: Harper Collins Publishers.

Garfinkel, Paul E.; Garner, David M. & Rose, Julia A. (1983). A comparison of characteristics of families with anorexia nervosa and normal controls. Psychological Medicine, 13, 821-828.

Garrett, Catherine (1996). Recovery from anorexia nervosa: A Durkheimian interpretation. Social Science Medicine, 43(10), 1489-1506.

Garrett, Catherine (1997). Recovery from anorexia nervosa: A sociological perspective. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 21, 261-272.

Gilbert, Adrienne A.; Shaw, Susan M. & Notar, Margaret K. (2000). The impact of eating disorders on family relationships. Eating Disorders, 8, 331-345.

Henderson, Katherine A.; Buchholz, Annick; Perkins, Julie; Norwood, Sarah; Obeid, Nicole; Spettigue, Wendy & Feder, Stephen (2010). Eating disorder symptom severity scale: A new clinician rated measure. Brunner-Mazel Eating Disorders Monograph Series, 18, 333-436.

Hillege, Sharon; Beale, Barbara & McMaster, Rose (2006). Impact of eating disorders on family life: Individual parents' stories. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 15, 1016-1022.

Hughes, Colleen S. & Hughes, Suzanne (2004). The female athlete syndrome: Anorexia nervosa—reflections on a personal journal. Orthopaedic Nursing, 23(4), 252-260.

Humphrey, Laura L. (1989). Observed family interactions among subtypes of eating disorders using structural analysis of social behavior. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 57(2), 206-214.

Jacobs, M. Joy; Roesch, Scott C.; Wonderlich, Stephen A.; Crosby, Ross; Thornton, Laura; Wilfley, Denise E.; Berrettini, Wade H.; Brandt, Harry; Crawford, Steve; Fichter, Manfred M.; Halmi, Katherine A.; Johnson, Craig; Kaplan, Allan S.; LaVia, Maria; Mitchell, James E.; Rotondo, Alessandro; Strober, Michael; Woodside, D. Blake; Kaye, Walter H. & Bulik, Cynthia M. (2009). Anorexia nervosa trios: Behavioral profiles of individuals with anorexia nervosa and their parents. Psychological Medicine, 39, 451-461.

Jennings, Piangchai S.; Forbes, David; McDermott, Brett; Hulse, Gary & Juniper, Sato (2006). Eating disorder attitudes and psychopathology in Caucasian Australian, Asian Australian and Thai university students. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry, 40, 143-149.

Jonat, Lee M. & Birmingham, Carl Laird (2004). Disordered eating attitudes and behaviours in the high-school students of a rural Canadian community. Eating & Weight Disorders, 9(4), 306-308.

Kearney, Margaret (1999). Understanding women's recovery from illness and trauma: Vol. 4. Women's mental health & development. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Kohut, Heinz (1977). The restoration of the self. New York: International Universities Press.

Kohut, Heinz (1984). How does analysis cure? Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Korb, Maria (1994). Anorexia as symbolic expression of a woman's rejection of her mother's life. Western Journal of Nursing Research, 16(1), 69-80.

Lamoureux, Mary M.H. & Bottorff, Joan L. (2005). "Becoming the real me": Recovering from anorexia nervosa. Health Care for Women International, 26(2), 170-188.

Lattimore, Paul J.; Wagner, Hugh L. & Gowers, Simon G. (2000). Conflict avoidance in anorexia nervosa: An observational study of mothers and daughters. European Eating Disorders Review, 8, 355-368.

Leavitt, Mira Zamansky & Hart, Daniel (1991). Development of self-understanding in anorectic and nonanorectic adolescent girls. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology, 12(3), 269-288.

Lester, Rebecca J. (1997). The (dis)embodied self in anorexia nervosa. Social Science Medicine, 44, 479-489.

Ma, Joyce L.C. & Chan, Zenobia C.Y. (2003). The different meanings of food in Chinese patients suffering from anorexia nervosa: Implications for clinical social work practice. Social Work in Mental Health, 176, 47-70.

Martin, Courtney E. (2007). Perfect girls, starving daughters: The frightening new normalcy of hating your body. New York: Free Press.

McComb, Jacalyn Robert; Cherry, Julie & Romell, Melissa (2003). The relationship between eating disorder attitudes and the risk of cardiovascular disease. Family and Community Health, 26(2), 124-129.

Mukai, Takao (1989). A call for our language: Anorexia from within. Women's Studies International Forum, 12(6), 613-638.

Poppink, Joanna (2011). Healing your hungry heart: Recovering from your eating disorder. San Francisco, LA: Conari.

Prescott, Margaret E. & LePoire, Beth A. (2002). Eating disorders and mother-daughter communication: A test of inconsistent nurturing as control theory. The Journal of Family Communication, 2(2), 59-78.

Schebendach, Janet E.; Mayer, Laurel E.; Devlin, Michael J.; Attia, Evelyn; Contento, Isobel R.; Wolf, Randi L. & Walsh, B. Timothy (2011). Food choice and diet variety in weight-restored patients with anorexia nervosa. Journal of the American Dietetic Association, 111, 732-736.

Shoebridge, Philip J. & Gowers, Simon G. (2000). Parental high concern and adolescent-onset anorexia nervosa. A case-control study to investigate direction of causality. British Journal of Psychiatry, 176, 132-137.

Sim, Leslie A.; Homme, Jason H.; Lteif, Aida N.; Vande Voort, Jennifer L.; Schak, Kathryn M. & Ellingson, Jarrod (2009). Family functioning and maternal distress in adolescent girls with anorexia nervosa. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 42, 531-539.

Soenens, Bart; Vansteenkiste, Maarten; Vandereycken, Walter; Luyten, Patrick; Sierens, Eline & Goossens, Luc (2008). Perceived parental psychological control and eating-disordered symptoms: maladaptive perfectionism as a possible intervening variable. Journal of Nervous & Mental Disease, 196(2), 144-52.

Sullivan, Victoria & Terris, Charlotte (2001). Contemplating the stages of change measures for eating disorders. European Eating Disorders Review, 9, 287-291.

Szekely, Eva A. (1989). From eating disorders to women's situations: Extending the boundaries of psychological inquiry. Counselling Psychology Quarterly, 2(2), 167-184.

Tereno, Susana; Soares, Isabel; Martins, Carla; Celani, Mariana & Sampaio, Daniel (2008). Attachment styles, memories of parental rearing and therapeutic bond: A study with eating disordered patients, their parents and therapists. European Eating Disorders Review, 16(1),49-58.

Thornton, Sara Jane (2007). Facing the sunshine: A young woman's emergence from the shadows of sexual abuse and anorexia. Salem, NH: Soaring Wings.

Toman, Erika (2002). Body mass index and its impact on the therapeutic alliance in the work with eating disorder patients. European Eating Disorders Review, 10, 168-178.

Vidovic, Vesna; Juresa, Vesna; Begovac, Ivan; Mahnik, Mirta & Tocilj, Gorana (2005). Perceived family cohesion, adaptability and communication in eating disorders. European Eating Disorders Review, 13, 19-28.

Weaver, Kathryn D.; Wuest, Judith & Ciliska, Donna (2005). Understanding women's journey of recovering from anorexia nervosa. Qualitative Health Research, 15(2), 188-206.

Kathryn WEAVER, PhD, RN combines the perspectives of clients with eating disorders, their families and health professionals to understand facilitators and barriers to recovery.

Contact:

Dr. Kathryn Weaver

Faculty of Nursing

University of New Brunswick

P.O. Box 4400, Fredericton, NB, Canada, E3B 5A3

Tel: +1 506 458 7648

Fax: +1 506 453 4519

E-mail: kweaver@unb.ca

URL: http://www.unb.ca/fredericton/nursing/people/profiles/kweaver.html

Kristine MARTIN-McDONALD, RN, BappSc (Nsg), MEd, PhD Kristine Martin-McDonald was invited to bring her expertise in narrative methodology to this project. Her research focuses on the qualitative aspects of self-management in chronic disease for populations in Australia and Canada.

Contact:

Dr. Kristine Martin-McDonald

Professor, Dean & Head of School, Nursing and MidwiferyVictoria University

Melbourne, Australia

Tel: +61 3 9919 2276

Fax: +61 3 9919 2719

E-mail: kristine.martin-mcdonald@vu.edu.au

URL: http://www.vu.edu.au/about-vu/our-people/kristine-martin-mcdonald

Judith SPIERS, RN, BA (Nursing), MN, PhD uses primarily qualitative approaches to explore the nature of chronic and often invisible illness and how this is constructed and understood in health professional-client interactions.

Contact:

Dr. Judith Spiers

Associate Professor

Faculty of Nursing

University of Alberta, Canada

Tel: +1 780 492 9821

Fax: +1 780 492 2551

E-mail: jude.spiers@ualberta.ca

URL: http://www.nursing.ualberta.ca/en/Staff/Faculty/JSpiers.aspx

Weaver, Kathryn; Martin-McDonald, Kristine & Spiers, Judith (2012). Mirroring Voices of Mother, Daughter and Therapist in

Anorexia Nervosa [43 paragraphs]. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung / Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 13(3), Art. 6,

http://nbn-resolving.de/urn:nbn:de:0114-fqs120363.