Volume 12, No. 3, Art. 12 – September 2011

On Blurred Borders and Interdisciplinary Research Teams: The Case of the "Archive of Mourning"1)

Cristina Sánchez-Carretero, Antonio Cea, Paloma Díaz-Mas, Pilar Martínez & Carmen Ortiz

Abstract: The main objective of this article is to present the "Archive of Mourning," a research project that focuses on the mourning ritual practices in public spaces that took place after the train bombings in Madrid on March 11th 2004. Due to the magnitude of these public mourning rituals, the impact of the bombings in Spanish society and the variety of voices expressed at the stations, a group of researchers working at the Spanish National Research Council (Consejo Superior de Investigaciones Científicas, CSIC) started a project to document and analyze the memorials at the stations. The twofold objective of documenting and analyzing the memorialization practices made this research project an interdisciplinary endeavor from the beginning; an initiative in which librarians, anthropologists and literature scholars collaborated.

Key words: grassroots memorials; mourning rituals; archives; March 11 train attacks

Table of Contents

1. Introduction

2. The "Archive of Mourning"

3. Lines of Research

3.1 Characterization of the grassroots memorial phenomenon from a comparative perspective

3.2 Analysis of urban movements in public spaces

3.3 Analysis of the messages deposited at the train stations

3.4 Analysis of religious iconography

4. Blurred Borders and Archives

The borders that separate the work done by library experts, archivists and museums professionals, on the one hand and the work conducted by researchers in the humanities and social sciences on the other, are becoming increasingly blurred. To conduct research on how to expand those borders is the goal of various international initiatives. The main objective of this article is to present an initiative in which librarians, anthropologists and literature scholars collaborated. The "Archive of Mourning" is the name of the project that combines the aforementioned disciplines: a research project that focuses on the mourning ritual practices in public spaces in the aftermath of the March 11 train bombings. [1]

Massacres, terrorist attacks and other events are memorialized in public spaces using a repertoire of public displays that are currently a recurrent pattern. These memorials arise at places where "traumatic" deaths take place. By "traumatic" we refer to certain deaths that originate a social response in which people do not necessarily know the deceased to experiment grief. Different objects are deposited usually at the place of the death (an accident, a murder, a massacre or a natural disaster, for instance). They differ from the institutional ones, such as monuments or official commemorations. The deaths that trigger these reactions are usually either linked to anonymous victims, who face an untimely death, or to the death of mass-mediated and popular characters. In both cases it is increasingly expected to find spontaneous shrines or grassroots memorials at the sites where the death took place. [2]

There are references of spontaneous memorials in public spaces from the nineteenth century, such as the1869 Lincoln Memorial (WIDMER, 2009), but the type of event described in this article is related to mass media and gained momentum in the late twentieth century. These memorials have in common their ephemeral quality, as they are not meant to last; they are non-institutional or non-official, as no organization is telling the grievers to place memorabilia at the places of the death; finally they are performative in the sense that they are intended to provoke certain actions, even if it is only a general protest, such as "this should not have happened." MARGRY and SÁNCHEZ-CARRETERO coined the term "Grassroots Memorials" (2011a) to name these practices, in order to overcome the problems attached to previous ways of referring to this phenomenon, such as "spontaneous shrines" (SANTINO, 1992, 2004, 2006a, 2006b; GRIDER 2001, 2007), "improvised memorials" (MARGRY & SÁNCHEZ-CARRETERO, 2007) or "temporary memorials" (DOSS, 2008). Grassroots memorialization is defined as "the process by which groups of people, imagined communities, or specific individuals bring grievances into action by creating an improvised and temporary memorial with the aim of changing or ameliorating a particular situation" (MARGRY & SÁNCHEZ-CARRETERO, 2011b, p.2). With this definition, the component of social action is brought to the front. [3]

After this introduction to the concept of "grassroots memorials," the next section presents the project, together with a description of the collection and the methodology; the last part includes a brief outline of the lines of research. [4]

On March 11th, 2004, around 7:30 am, ten bombs exploded in four commuter trains in the "Corredor del Henares," a train line that links the town of Alcalá de Henares and Madrid. The bombs, placed by Al-Qaeda, killed 192 people and injured a further 1,857, according to the official figures included in the judicial process. Immediately after the attacks many people gathered at the commuter train stations of El Pozo, Santa Eugenia and Alcalá de Henares, and at Madrid central station of Atocha to deposit offerings. The stations turned into shrines full of candles, flowers, writings, and other memorial elements (see Illustrations 1 to 5).

Illustration 1: Atocha train station, Madrid. Photograph deposited at the "Archive of Mourning" project

Illustration 2: Alcalá de Henares train station, Madrid. Photograph deposited at the "Archive of Mourning" project

Illustration 3: El Pozo train station, Madrid. Photograph deposited at the "Archive of Mourning" project

Illustration 4: El Pozo train station, Madrid. Photograph deposited at the "Archive of Mourning" project

Illustration 5: Santa Eugenia train station, Madrid. Photograph deposited at the "Archive of Mourning" project [5]

Due to the magnitude of the public mourning rituals, the impact of the bombings in Spanish society and the variety of voices expressed at the stations, a group of researchers working at the Spanish National Research Council (CSIC) started a project that documents and analyzes the memorials at the stations (SÁNCHEZ-CARRETERO, 2006). The twofold objective of documenting—producing materials that were going to be described and preserved—and analyzing the responses in the aftermath of the attacks, made this research project an interdisciplinary endeavor from the beginning, with librarians collaborating with other CSIC researchers. [6]

The collection that forms part of the "Archive of Mourning" started to be compiled right after the attacks. The first reactions, particularly the uses of public spaces at the train stations were the focus of interest of the anthropologists involved in the project. They started to photograph the stations, while later on, other materials, such as oral interviews, were also added. But the initial project changed considerably when CSIC signed an agreement with RENFE (The National Spanish Train Company) by which RENFE gave to this project the actual objects kept from the memorials at the different stations so that they could be classified, studied and kept in an adequate form in an academic environment. [7]

The "Archive of Mourning" is not an actual archive; technically it is a collection formed by multiformat documents, but as the project was named as such by the research team, the notion of "the archive" was maintained. The methodological model that was followed, was the same employed by similar projects conducted after the September 11th attacks in New York by the American Folklife Center at the Library of Congress, Washington (SÁNCHEZ-CARRETERO, KRUESI & SHANKAR, 2005).

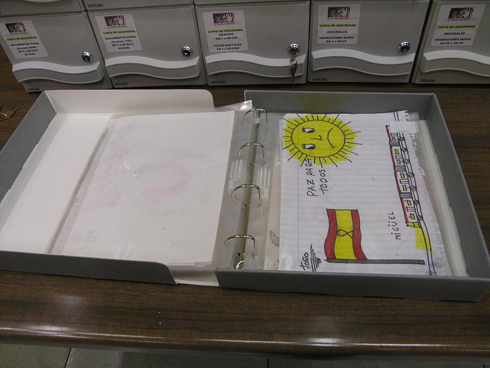

Illustration 6: Final disposition of the original documents [8]

The research team faced a new challenge because the photographic, video and audio materials had their own description and conservation requirements, completely different from the newly incorporated materials, such as papers, flowers, teddy bears, t-shirts, or calendars, among many others. [9]

This new reality made the research team re-think the original technical procedures and search for advice among professionals to guarantee the best conservation status for these materials. The first objective was to design a technical procedure to guarantee the final goals of the project. This procedure was organized according to the following phases2):

Delimitation of collection,

cleaning and conservation processes,

inventory of the collection,

cataloging and classification of the materials,

study and research,

diffusion of results. [10]

To develop the project, a team of professionals from various disciplines was put together (anthropologists, literature scholars, librarians, archivists, etc.) and institutional funding was obtained. Finally the project was supported by students from different institutions, such as the Universidad Autónoma de Madrid, The College of William and Mary (USA), American University (USA) and the Library of Congress. [11]

From the beginning, the collection was limited to the materials directly related to the mourning processes that took place during the first year after the attacks. The collection however, has some exceptions to this time limitation, incorporating some offerings that started to be prepared after the attacks, but were only completed several months later, for instance, the book made with children drawings from the Young Muslim Association, the catalog of photographs "Madrid in Memoriam" or some interviews about the March 11th mourning. [12]

The biggest technical difficulty was to create an organized collection from materials so fragile and diverse. The second phase—cleaning and conservation processes—demanded special care to avoid producing more damage to the already deteriorated objects and documents, which were extremely fragile. Archival and museum techniques were applied and conservation materials were employed, following standard procedures in archives and libraries.

Illustration 7: Cleaning process [13]

This phase of the project offered the first data of the collection:

Photographs: 2482

Objects: 495

Offerings made of paper: 6432

E-mails: 58732

Recordings: 64 [14]

After this phase, the team started the cataloging and classification of the collection with the objective of describing each document in a catalog so that information could be retrieved in a simple way. This process was developed according to the technical guidelines of the library system of the CSIC, following the criteria of the CSIC Unit of Information Resources for Research3) because the project's priority was to work with the resources available at the CSIC, as well as with their professionals and experts. In addition, due to the particularities of this collection, before starting the phase of description, a seminar was organized in 2005, dedicated to share and analyze the protocols followed by other institutions more experienced on these topics, such as the American Folklife Center at the Library of Congress (Washington) and various Spanish ethnographic museums. Since then, the seminar Archives and Memory has being organized by the CSIC and the Spanish Railway Foundation on a yearly basis. [15]

This information created a classification chart defining the identification codes of the archive in the digital catalog; the chart also delineated the most adequate fields, which could guarantee the normalized description of the documents of the collection according to the characteristics of the catalog. The CSIC Archives Catalog uses the MARC format and the fields have been selected according to the ISAD (G) (CONSEJO INTERNACIONAL DE ARCHIVOS, 2000). Due to this reason and in order to facilitate the information retrieval, the use of a controlled vocabulary was implemented.

Illustration 8: Treatment of digital photographs of objects [16]

Between 2005 and 2008, the phase of cataloging and classification was conducted. The sections of Photographs, Objects, Video Recordings and Oral Testimonies have been described to the level of document. [17]

In order to guarantee its public access, in March 2010 the collection—together with the databases— was deposited at the Historical Railway Archive (Archivo Histórico Ferroviario) which is part of the Spanish Railway Foundation (Fundación de los Ferrocarriles Españoles). The work done in the cataloging and classification phases allowed the members of the research team to have access to the various types of documents and develop the studies based on the collection. [18]

3.1 Characterization of the grassroots memorial phenomenon from a comparative perspective

Grassroots memorials are an international western phenomenon, in which mass media performs a relevant role. In the case studies analyzed in the book Grassroots Memorials edited by MARGRY and SÁNCHEZ-CARRETERO (2011a), social activism is one of the common elements of these memorials. Offerings are deposited at the sites of a traumatic death to ask for actions. "This shouldn't happen!" or "who is responsible?" are common ideas expressed in the texts. In addition, the unofficial nature of the memorials is another element that all examples have in common: there is no institution or organization that tells the mourners to go to these places. In this sense, the word "spontaneous" has been also used to describe these memorials as a synonym of "unofficial" or "noninstitutional" (SANTINO, 1992, 2004, 2006a, 2006b; GRIDER, 2001). [19]

MARGRY and SÁNCHEZ-CARRETERO (2011a) have further compared case studies from Holland, Spain, The United States, England, Italy, Poland, Venezuela and Bali to define the common elements of this type of contemporary memorialization briefly explained in the introduction of this article. In some cases, the victims are anonymous common citizens, such as the cases of the school shootings in the United States (Columbine 1999, Virginia Tech 2007 and Northern Illinois University 2008) or the memorials of terrorists attacks (such us September 11 and March 11); in other cases the deceased are widely known people, such as the memorials after the death of Pope John Paul II in Poland. Other memorials are triggered by natural catastrophes, such as the floods in Venezuela in 1999. Some of them take place after individual murders, such as the memorial dedicated to Carlo GIULIANI in Genoa in 2001, who was killed while participating in an anti G-8 demonstration, the killing of Theo VAN GOGH and Pim FORTUYN in Amsterdam in 2004, or the memorial dedicated to the judge FALCONE, murdered by the mafia in Palermo in 1992.

Illustration 9: Glass walls with graffiti at Atocha train station. Photograph deposited at the "Archive of Mourning" project

[20]

3.2 Analysis of urban movements in public spaces

Among the many aspects related to solidarity and support for the victims and condolences to their families, which took place after the March 11th train attacks, the demonstrations that spontaneously took over public spaces were of great importance and had an equally important mass media presence. The memorials at the stations, and particularly at Atocha train station, are the most significant ones, from the point of view of mourning rituals and memorializing processes. Atocha turned into a "pilgrimage" site in the sense that from March 11th to early June, 2004—when the offerings were cleaned out—thousands of citizens went to Atocha to leave their offerings and testimonies. [21]

This line of research explores the relationship between grassroots memorials and other types of commemorative monuments (ORTIZ, 2011). Grassroots memorials, spontaneous shrines or improvised memorials are linked to patterns related to folk culture and are clearly different from memorial monuments built to commemorate tragedies, violent events or traumatic circumstances of political transcendence. The ways in which political attitudes are expressed are also different in both types of memorials, although they have common elements. This type of memorials has a considerable impact upon monuments and official commemorative sites, due to the influence of mass media, and the increasing number of cases of grassroots memorials in various countries. For instance, the March 11 official monument built underneath Atocha train station includes the messages written by anonymous citizens at their on-line memorial site.

Illustration 10: A woman deposits an offering while a camera records it. Atocha train station, Madrid. Photograph deposited

at the "Archive of Mourning" project [22]

3.3 Analysis of the messages deposited at the train stations

The majority of the offerings deposited at the memorials located at the train stations in the aftermath of March 11th 2004 attacks have texts in various media (such as paper, banners, cards bearing religious images or estampas, pieces of clothing, various kinds of objects, brick or glass walls located at the stations). For this reason, a philologist was added to the research team to analyze these materials from the perspective of their creativity and literary communication, as well as in relation to the history of literature. [23]

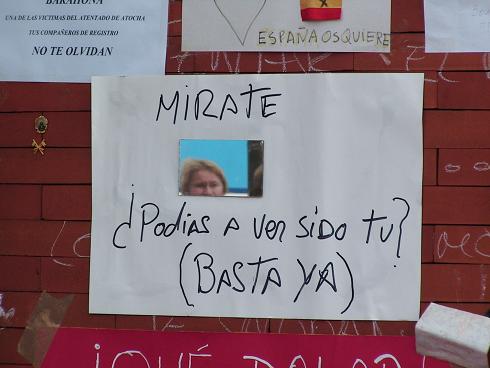

In this line or research, the following topics have been explored: the use of writing as an instrument of memorialization; the relationship between writing and orality, the consciousness of individual authorship compatible with the personal contribution to a collective literary work; the semantic importance of the material support of the texts and their interaction with the text itself; the use of artful devices—even by not so much literate people—such as metrical forms and rhetoric procedures; the relationship between the texts deposited at the memorials, the literary cannon and its reconfigurations through this relationship; finally the co-existence of various literary genres such as epistolography, chronicle, fiction narrative, sorrowful poetry or moral literature. The March 11 texts allow us to reflect on the function of literature at the beginning of the 21st Century, its cathartic value in moments of crisis and its role as an instrument of social cohesion (DÍAZ-MAS, 2011).

Illustration 11: Message saying "look at you. It could've been you." Photograph deposited at the "Archive of Mourning" project

[24]

3.4 Analysis of religious iconography

Among the various ways employed to express grief and solidarity at the memorials in Madrid in the aftermath of the March 11 attacks, the Catholic component is an important element, with a thousand examples of cards bearing religious images kept at the Archive of Mourning (CEA, 2011). The iconographic and textual formulas placed at the obverse and back of the cards show the importance of written liturgical formulas as well as non-canonical ones—but nevertheless considered to be saint. These formulas further show how sacred images are used both as pocket personal devotional objects and as a promotional mechanism for various religious congregations. The textual parts of the cards offer novenas, triduos, jaculatorias, anthems, and gozos (different forms of verses written in honor of the Virgin or a saint); others are written as mementos of a first communion or burial. [25]

In addition, there are prayers of magical character, which are reused in syncretic contexts such as santería. Images of Christ, virgins and saints, present at the March 11 shrines, show current rituals and practices of devotional life, wherein various socio-religious registers are present. For example, signs of faith inscribed in cards dedicated to San Pancracio, Santa Gema, San Judas Tadeo o Jesús de Medinaceli are next to the clearly promotional objectives of cards dedicated to José María Escrivá or Madre Maravillas. The phenomenon of apparitions and apocalyptic messages is also present, including devotions such as Sacred Heart, Lourdes, Fatima or la Dolorosa del Prado del Escorial. With this collection of religious cards the impact of solidarity could be represented in a hagiographic map of local, regional, national and international character. Finally, the utilitarian purpose of calendar-religious cards, as objects with an expiration date, is also present in the collection. At the March 11 shrines, popular devotion is one of the ways deployed to condemn what happened and express consolation and solidarity.

Illustration 12: Religious offerings at Atocha train station. Photograph deposited at the "Archive of Mourning" project [26]

4. Blurred Borders and Archives

Research projects such as the one presented here show that part of the research itself consists of being part of a blurring effort to transcend disciplines. In this case, the organization of a multiformat collection that documents the memorializing practices developed at the train stations of Atocha, El Pozo and Santa Eugenia was a constitutive part of the research project itself and not only a tool. From this point of view, this article stresses the importance of dedicating efforts —since the initial phases of our projects— to the organization of the sources that researchers generate and make decisions about where to place them.4) [27]

1) The "The Archive of Mourning" project was funded by the Spanish Ministry of Science and Innovation (HUM2005–03490) and is part of the CRIC (Cultural Heritage and the Reconstruction of Identities after Conflict) research project funded by the European Union 7FP (Ref. 217411). <back>

2) See MARTÍNEZ (2011) for a detailed description of this process. <back>

3) CSIC has an archive website at http://bibliotecas.csic.es/archivos/archivos.html [Accessed: June 15, 2011]. <back>

4) On the importance of depositing the sources generated during research projects in public archives, see the initiative of Qualidata. <back>

Cea, Antonio (2011). Sistema y mentalidad devocional en las estampas del 11M. Imágenes, palabras, tiempos, lágrimas. In Cristina Sánchez-Carretero (Ed.), El Archivo del duelo. Análisis de la respuesta ciudadana ante los atentados del 11 de marzo en Madrid (pp.175-205). Madrid: CSIC.

Consejo Internacional de Archivos (2000). Normas Internacionales de Descripción Archivística. Madrid: Ministerio de Educación, Cultura y Deporte.

Díaz-Mas, Paloma (2011). Literatura para la vida: textos en los santuarios del 11M. In Cristina Sánchez-Carretero (Ed.), El Archivo del duelo. Análisis de la respuesta ciudadana ante los atentados del 11 de marzo en Madrid (pp.83-133). Madrid: CSIC.

Doss, Erika (2008). The emotional life of contemporary memorials: Towards a theory of temporary memorials. Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press.

Grider, Sylvia (2001). Spontaneous shrines: A modern response to tragedy and disaster. New Directions in Folklore, 5, http://www.temple.edu/english/isllc/newfolk/shrines_update.html [Accessed: August 30, 2009].

Grider, Sylvia (2007). Public grief and the politics of memorial. Contesting memory of "the shooters" at Columbine High School. Anthropology Today, 23(3), 3-7.

Margry, Peter Jan & Sánchez-Carretero, Cristina (2007). The politics of memorializing traumatic death. Anthropology Today, 23(3), 1-2.

Margry, Peter Jan & Sánchez-Carretero, Cristina (Eds.) (2011a). Grassroots memorials. The politics of memorializing traumatic death. Oxford: Berghahn.

Margry, Peter Jan & Sánchez-Carretero, Cristina (2011b). Rethinking memorialization: The concept of grassroots memorials. In Peter Jan Margry & Cristina Sánchez-Carretero (Eds.), Grassroots memorials. The politics of memorializing traumatic death (pp.1-48). Oxford: Berghahn.

Martínez, Pilar (2011). La colección documental y bibliográfica del Archivo del Duelo. Creación, conservación y descripción. In Cristina Sánchez-Carretero (Ed.), El Archivo del duelo. Análisis de la respuesta ciudadana ante los atentados del 11 de marzo en Madrid (pp.69-81). Madrid: CSIC.

Ortiz, Carmen (2011). Memoriales del atentado del 11 de marzo en Madrid. In Cristina Sánchez-Carretero (Ed.), El Archivo del duelo. Análisis de la respuesta ciudadana ante los atentados del 11 de marzo en Madrid (pp.33-67). Madrid: CSIC.

Sánchez-Carretero, Cristina (2006). Trains of workers, trains of death: Some reflections after the March 11th attacks in Madrid. In Jack Santino (Ed.), Spontaneous shrines and the public memorialization of death (pp.333-347). New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

Sánchez-Carretero, Cristina (Ed.) (2011). El Archivo del duelo. Análisis de la respuesta ciudadana ante los atentados del 11 de marzo en Madrid. Madrid: CSIC.

Sánchez-Carretero, Cristina; Kruesi, Margaret & Shankar, Guha (2005). Mourning and grief in response to terrorism: AFC staff members address a symposium in Spain. Folklife Center News, Fall, 14-15.

Santino, Jack (1992). "Not an important failure." Spontaneous shrines and rites of death and politics in Northern Ireland. In Michael McCaughan (Ed.), Displayed in mortal light (no pagination). Antrim: Arts Council.

Santino, Jack (2004). Performance commemoratives, the personal, and the public: Spontaneous shrines, emergent ritual, and the field of Folklore. Journal of American Folklore, 117, 363-372.

Santino, Jack (Ed.) (2006a). Spontaneous shrines and the public memorialization of death. New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

Santino, Jack (2006b). Performative commemoratives: Spontaneous shrines and the public memorialization of death. In Jack Santino (Ed.), Spontaneous shrines and the public memorialization of death (pp.5-15). New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

Widmer, Ted (2009). New York's Lincoln Memorial. New York Times, 17 April, http://www.nytimes.com/2009/04/17/opinion/17widmer.html [Accessed: August 27, 2009].

Cristina SÁNCHEZ-CARRETERO is a staff researcher at the Spanish National Research Council (CSIC); anthropologist specialized in heritagization processes, and creation of new rituals, particularly in migration contexts.

Contact:

Cristina Sánchez-Carretero

The Institute of Heritage Sciences (Incipit), CSIC

San Roque 2, 15704 Santiago de Compostela

Spain

Tel.: +34 981540239

Fax: +34 981540240

E-mail: cristina.sanchez-carretero@incipit.csic.es

URL: http://csic.academia.edu/CristinaS%C3%A1nchezCarretero

Antonio CEA is a senior researcher at the Spanish National Research Council (CSIC). He is an anthropologist specialized in religious iconography.

Contact:

Antonio Cea

Institute of Language, Literature and Anthropology, CSIC

Albasanz 26-28, 28037 Madrid

Spain

Tel.: +34 91 6022300

Fax: +34 91 6022971

E-mail: antonio.cea@cchs.csic.es

URL: http://www.illa.csic.es/es/ficha1?apellido=Cea Gutiérrez&nombre=Antonio

Paloma DÍAZ-MAS is a senior researcher at the Spanish National Research Council (CSIC) and an expert in literature studies, particularly traditional and Sephardic literature.

Contact:

Paloma Díaz-Mas

Institute of Language, Literature and Anthropology, CSIC

Albasanz 26-28, 28037 Madrid

Spain

Tel.: +34 91 6022300

Fax: +34 91 6022971

E-mail: paloma.diazmas@cchs.csic.es

URL: http://www.illa.csic.es/es/ficha1?apellido=Díaz Mas&nombre=Paloma

Pilar MARTÍNEZ is the director of the Library "Tomás Navarro Tomás," Spanish National Research Council (CSIC).

Contact:

Pilar Martínez

Tomás Navarro Tomás Library

CCHS-CSIC

Albasanz 26-28, 28037 Madrid

Spain

Tel.: +34 91 6022649

Fax: +34 91 6022971

E-mail: pilar.martinez@cchs.csic.es

URL: http://biblioteca.cchs.csic.es

Carmen ORTIZ is a senior researcher at the Spanish National Research Council (CSIC). Anthropologist specialized in the history of anthropological ideas and practices in the modern period, and daily-life expressive culture in urban contexts.

Contact:

Carmen Ortiz

Institute of Language, Literature and Anthropology, CSIC

Albasanz 26-28, 28037 Madrid

Spain

Tel.: +34 91 6022300

Fax: +34 91 602 29 71

E-mail: carmen.ortiz@cchs.csic.es

URL: http://www.illa.csic.es/es/ficha1?apellido=OrtizGarcía&nombre=Carmen

Sánchez-Carretero, Cristina; Cea, Antonio; Díaz-Mas, Paloma; Martínez, Pilar & Ortiz, Carmen (2011). On Blurred Borders and

Interdisciplinary Research Teams: The Case of the "Archive of Mourning" [27 paragraphs]. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung / Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 12(3), Art. 12,

http://nbn-resolving.de/urn:nbn:de:0114-fqs1103124.