Volume 12, No. 3, Art. 10 – September 2011

Secondary Analysis of Qualitative Interview Data: Objections and Experiences. Results of a German Feasibility Study

Irena Medjedović

Abstract: The German feasibility study on archiving and reusing qualitative interview data has surveyed experts, namely qualitative researchers. Their views, ideas and problems have to be considered as central conditions if the aim is to open up the horizon for the theory and practice of secondary analysis. Although the overall results of the feasibility study can be regarded as quite positive, this contribution takes a closer look at the issues of secondary analysis of qualitative data. The analysis shows that there are some concerns and open issues associated with this new and unfamiliar research strategy. On the methodological side specificity and context sensitivity of qualitative research are raised as objections. On the ethical side concerns relate to an assumed breach of the confidential relationship to the research subject constituted within an interview. Furthermore, considerations concerning competition also play a role when researchers are asked to provide their data for reuse by others. This article provides a further step for a discussion about qualitative secondary analysis (in Germany), by pointing out the critical aspects of secondary analysis. But the experience of the expert researchers who were interviewed suggests that the problems associated with secondary analysis do not necessarily constitute unsolvable obstacles.

Key words: secondary analysis; qualitative interviews; feasibility study; data fit; context; research ethics

Table of Contents

1. Introduction

2. The German Feasibility Study on Archiving and Reusing Qualitative Interview Data

2.1 The quantitative survey

2.2 The qualitative survey

3. Results from the Feasibility Study

3.1 Urgency of establishing an archive

3.2 Problems and objections surrounding secondary analysis of qualitative data

3.3 Learning from experiences with secondary analysis of qualitative data

4. Some Conclusions

In Germany as in many other countries there is an abundance of experience with secondary analysis of quantitative data. In particular, the "Data Archive for the Social Sciences" (formerly the Central Archive for Empirical Social Research, ZA) of the GESIS Leibniz-Institute for the Social Sciences—the German institution for Social Science Infrastructure Services—1) in Cologne has for more than 50 years supported and promoted this tradition of social science and multidisciplinary research by providing the opportunity to use a wide range of social science data for secondary analysis. A similar picture cannot be drawn for the area of qualitative research in Germany. In spite of the growing relevance of qualitative methods since the 1970s, there is no widespread culture of data sharing in qualitative research nor can one find an institution providing a user-oriented data service for qualitative material on a nationwide scale. In view of this situation the "Archive for Life Course Research" (ALLF)2) at the University of Bremen addresses itself to the task of improving the unsatisfactory methodological and data-related conditions through projected national archival development. [1]

As a first step, a nationwide feasibility study on archiving and secondary use of qualitative interview data has been conducted. This mainly empirical study was submitted and carried out jointly by ALLF and GESIS and provides the scientific basis for building up an archive. [2]

Although the overall results of the feasibility study can be regarded as quite positive towards the aim of establishing a culture of data sharing and archiving in qualitative research, this contribution takes a closer look at the issues of secondary analysis of qualitative data. I begin with an outline of what German qualitative researchers see as the prevailing objections and problems concerning secondary qualitative data analysis. Further, contrasting these issues with experiences researchers actually had, should aid analysis as to whether and how the identified obstacles can be overcome with regard to establishing secondary analysis in qualitative research. [3]

I illustrate these points drawing on results of the feasibility study. Before dealing with the issues of secondary analysis, it is necessary to provide some background information on the project. [4]

2. The German Feasibility Study on Archiving and Reusing Qualitative Interview Data

Qualitative data, especially interview data, are a rich and often not fully exploited source of research material. Moreover, given the growing importance of qualitative empirical research, the progress of computer-supported data collection and preparation, as well as the development of software to support data analysis, it is surprising that there is no significant research culture to encourage the reuse and secondary analysis of qualitative data collected by other researchers. [5]

As already mentioned at the beginning, in the area of quantitative empirical social research, the GESIS "Data Archive for the Social Sciences" at the University of Cologne has amongst others during the last 50 years helped to establish a policy of reciprocity, of give and take of research data in Germany. There is currently no other comparable institution in Germany which collects, archives, documents and provides qualitative data for scientific secondary use. The responsibility for the data rests with the individual researcher. Often the data is stored in offices or at home, where as a rule it is not accessible for others and where the long-term storage is uncertain. [6]

As a result of these considerations the German Research Foundation (DFG) financed a cooperation project for the Archive for Life Course Research (ALLF) at the University of Bremen and the GESIS, to explore the feasibility of a service infrastructure for qualitative research and to examine the desiderata the scientific community demands of such an institution. The feasibility study3) aimed to explore whether and to what extent social science researchers can be considered as potential data depositors, on the one hand, and future re-users of qualitative data for research and academic teachings, on the other. For this purpose, it combined a nationwide quantitative and a qualitative survey of qualitative researchers, using the results to inform the criteria and concepts for archiving qualitative data (see MEDJEDOVIĆ, WITZEL, MAUER & WATTELER, 2010). [7]

At first, managers of qualitative projects in the social sciences were surveyed by means of a standardised questionnaire. The sample was drawn from the SOFIS-Databank (formerly FORIS) with support from the GESIS department "Specialized Information for the Social Sciences" in Bonn. As a result, approximately 18,000 projects working with qualitative methods in the period from 1984 till 2003 were identified. Of these, all those projects were chosen which started in 1993 or later, used qualitative interviews or expert interviews and contained information about a project manager. After checking these addresses, 1,750 projects with 1,104 project managers remained. The rate of return was 39% (with 430 cases). [8]

One aim of the questionnaire survey was to take stock of the available data material in Germany. Part of this stocktaking were questions on the whereabouts of the data, data formats, state of anonymisation and documentation, as well as an estimation of necessary steps of data processing to make the data available to others. Moreover, the willingness was asked to place the data from finished or future projects at the disposal of others. A further block of questions dealt with the reuse and secondary analysis of data: Who uses, or has used, own data and in which context? Have the respondents themselves ever used the data compiled by other persons, and what experience did they make when doing so? Are they interested in a secondary analysis of qualitative data in the future? Finally, we asked some questions regarding the support for establishing an archive for qualitative data and the type of services the respondent would expect from such an archive. The questionnaire contained both closed-ended and open-ended questions.4) [9]

The qualitative survey was drawn on the sample theoretically founded on the sample of the quantitative survey. Of the 430 respondents of the quantitative survey, 36 researchers were asked for an interview in order to explore the topic in more depth and answer still open issues. This supplementary qualitative survey aimed to investigate the researchers' willingness and more precise conditions for the provision, processing and archiving of their data; as well as their views on the reuse of their data by other researchers, particularly with regard to possible needs for retaining control towards users of their data. Moreover, besides investigating the problems, objections and scepticism of qualitative researchers towards archiving and secondary analysis of qualitative data in general, the survey also focussed on the perspective of potential re-users, i.e. their interest in reusing data and demands on conditions for conducting a secondary analysis, for instance an appropriate data processing and documentation. [10]

Based upon the statements the respondents made in the questionnaire survey, the sub-sample was selected via a mix of the following criteria: experienced with reuse; experienced with providing data; setting conditions for data provision, especially "control over data dissemination"; refusal of data provision and secondary analysis, especially because of "context sensitivity". A further aspect of the sample was to represent a reasonable number of both supporters and non-supporters of the formation of an archive. Moreover, researchers were selected whose research projects seemed to be suitable for archiving. [11]

The survey was conducted by means of problem-centered interviews (WITZEL, 2000), which are guided interviews that combine focused with narrative techniques. In the end, a total of 36 interviewees were asked to elucidate their experiences with secondary analysis and providing data for reuse, including related difficulties; to explain associated objections, problems or conditions; and also to comment on special topics, e.g. context and role of documentation, confidentiality and anonymisation, and common data processing practices; as well as—rather at the end of the interview—on the desiderata for an archive. [12]

3. Results from the Feasibility Study

The surveys of the feasibility study emerged to be a rich source for exploring the issue of secondary analysis as well as the archiving of qualitative data. First, I will outline some overall results regarding the feasibility of establishing a service organisation for archiving and disseminating qualitative data. Then, I will deal with problems and objections surrounding secondary analysis which arise mainly from the lack of experience with secondary analysis. Namely, why have researchers so far neglected a secondary analysis of qualitative data? And for what reasons do researchers refuse to provide their data for secondary analysis? In a third step, I will draw on reported experiences with secondary analysis some of the surveyed researchers actually had. Analysing these experiences should help to explore to what extent and how the assumed problems really occur. In other words: Do the objections against secondary analysis of qualitative data constitute obstacles which are insurmountable? [13]

3.1 Urgency of establishing an archive5)

The importance of establishing an archive became immediately apparent from the fact that much research data is in danger of becoming lost. The feasibility study sought to identify the whereabouts of research data from circa 1,100 German projects with a total of 80,000 qualitative interviews. The results were re-assuring at first glance: data has been lost from only 13% of all reported projects. But taking into consideration that 60% of the reviewed projects were just finished in 2003-2004 or were still ongoing and that the period under review comprised only the last ten years, the amount of unrecoverable data is already substantial. [14]

Given the situation described above, it seemed surprising that data from roughly one quarter of the projects was described as already archived. However, further inquiries through the expert interviews carried out as part of the feasibility study revealed that material described as archived had simply been stored in a room in their institution, which does not even fulfil the basic standards of a professional archive. That often means that only original audio tapes or partly transcribed interview texts exist, the material is often not anonymised, it is kept without physical security, and that there is no public access to data, or accompanying documentation or cataloguing. [15]

Despite existing uncertainty, lack of knowledge and scepticism concerning the opportunities and advantages of reusing qualitative data material (see the following sections), 80% of the respondents were in favour of the idea of building up an infrastructure for archiving their research as a source of qualitative data in Germany. Part of the feasibility study was to take stock of qualitative material in Germany. Analysis showed a large number of projects based on qualitative interviews, with around 60% of the project leaders willing in principle to pass on the data to others for re- or secondary analysis. Moreover, 65% of the respondents could imagine conducting secondary analysis in the future.

"Just taking the number of project managers interviewed in the feasibility study who signalled a willingness to give their data to an archive, this already adds up to more than 400 data sets which in principle could be archived and thus potentially could be made available for secondary use to the scientific community. Over 60% of these datasets derive thematically from sociology, political science and educational research and, according to the primary investigators, they are to a high extent usable for further research projects (90%), and for teaching and dissertations (in each case 75%)" (OPITZ & MAUER, 2005, p.12, translated from the German). [16]

Although the overall results of the feasibility study can be regarded as quite positive towards the aim of establishing a culture of data sharing and archiving in qualitative research, I will now take a closer look at the issues of secondary analysis of qualitative data. To understand and resolve these issues is a precondition for establishing a data service with the goal to promote the scientific reusing of the provided data in research and academic teachings. [17]

3.2 Problems and objections surrounding secondary analysis of qualitative data

Many of the various articles on secondary qualitative data analysis deal with doubts about its feasibility. This scepticism ranges mainly from epistemological and methodological objections to ethical and confidentiality concerns. As already mentioned at the beginning, the debate in Germany is just in its infancy. The feasibility study aimed to explore the obstacles to secondary analysis which prevail in the German scientific community.6) [18]

Apparently in contrast to the state of the debate in Germany, the results of the feasibility study show that the secondary analysis of qualitative data is already being conducted to some degree. More than half of the respondents reported that their qualitative data had been reused; in most of these cases the respondents reused them themselves. Further, more than one third of the respondents stated that they had conducted a secondary analysis of qualitative data, albeit using own data in the majority of cases. However, in 20% of the secondary analyses quoted the data were taken from other sources than their own or that collected by colleagues. Thus, although the results indicate that the great majority of examples of reuse and secondary analyses of qualitative data are of own data, given the absence of an archive for qualitative data, an unexpectedly high number of researchers already seem to reuse other researchers' data. [19]

These results of the quantitative survey can thus be regarded as quite positive towards the aim of establishing secondary analysis in qualitative research, but they have to be specified by the results of the qualitative survey, which point at an unfamiliarity with this new method of secondary analysis and its definition. [20]

As far as reuse of own data is concerned, this is done in the case of academic teaching, one's own dissertation, as well as for research purposes—such as for instance preparing a new research project, or undertaking supplementary analyses of aspects which (as a result of very restricted time and research resources) were not considered or fully addressed in the primary study. Researchers use their data beyond the end of the original research, thus acting in the sense of "continuous analytical exploration" (ÅKERSTRÖM, JACOBSSON & WÄSTERFORS, 2004, p.345). However, these cases are often seen as part of the original research and do not count as secondary analysis7). Therefore it is assumed that secondary analysis of own qualitative data is even more commonplace than the quantitative results imply. On the other hand, in terms of secondary analysis of qualitative data collected by others, it appears the opposite way around, as reusing other researchers' data seems to be less common than the quantitative results indicate: Not all of those cases stated in the questionnaire turned out to be such in the face-to-face interview. For instance, in one case the respondent had not reused qualitative data, but the results of a qualitative research project. In other cases the interviewed researchers simply did not mention their experiences with others' data, rather they reported on secondary analyses of their own data. Or in the extreme, it even seemed like the interviewee evaded the issue altogether. [21]

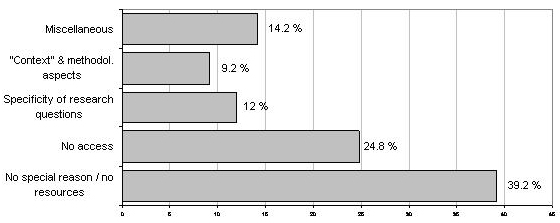

But let us turn to the other group of respondents, i.e. the "inexperienced" qualitative researchers. About 60% (n=270) of the 430 respondents of the quantitative survey stated that they had never conducted a secondary analysis of qualitative data, whether of their own or other researcher's data. Figure 1 lists the reasons given by these respondents.

Figure 1: Reasons for not having conducted a secondary analysis [22]

As can be seen in Figure 1, a substantial quantity of the respondents had no special reason, no need or no time and resources for secondary use, or was working to full capacity with their own data collection, or answered with a combination of those reasons. The common denominator of these different statements seems to be that researchers are still far from taking secondary analysis into account. One can imagine a researcher answering: "Why should I?" In other words, like almost every new thing, secondary analysis of qualitative data also has to face established habits. According to prevailing practice, researchers are working to full capacity with their own data collection and see no need for using other researchers' data—which furthermore would represent a less accepted means for career and reputation; thus, research is dominated by the primacy of primary research. Moreover, in view of these research habits and as well the lack of a service infrastructure to enable access to qualitative research data, it is not surprising that nearly one quarter of the respondents reasoned that there were no appropriate data available, or that they had no knowledge about the existence of any data for reuse or how to find data. [23]

However, finding appropriate (or "fitting") data is—by definition—one important issue in secondary research in general (HEATON, 1998, 2004). While the issue of data fit also contains aspects like the extent of missing data (HINDS, VOGEL & CLARK-STEFFEN, 1997), and the methods used to produce the data (THORNE, 1994), the key aspect provided in Figure 1 seems to be the question of feasibility of a secondary qualitative data analysis in terms of the specific research question: 12% of the respondents stated that their research questions or interests were too specific to think of already existing fitting data. In this respect, the overall results of the survey indicate a researcher's view on qualitative research as characterised by its specificity. As it is collected for a particular set of research aims and objectives, qualitative research data is regarded as hardly being suitable for any secondary research question. Conversely, no suitable qualitative data is assumed to exist for one's very own and special research question, unless having been collected by oneself. [24]

Compared to the illustrated objections and problems surrounding secondary analysis, the figures (see Figure 1) related to methodological objections—and especially the context-issue—play a rather minor role.8) This result contrasts the major relevance that prevailing debates and literature on archiving and secondary analysis of qualitative data attribute to the issue of research context (see e.g.: CORTI, 2006; CORTI, WITZEL & BISHOP, 2005; HAMMERSLEY, 1997; MAUTHNER, PARRY & BACKETT-MILBURN, 1998; VAN DEN BERG, 2005). However, whenever research data are being analysed outside of the context in which they were collected, the risk of decontextualisation is a crucial point; especially in qualitative research, "because analyzing social events within their social context is generally considered as one of the hallmarks of qualitative research" (VAN DEN BERG, 2005, p.18). Grounded in this argument, respondents challenge the feasibility of secondary analysis of qualitative data in principle. Underlying the assumption that qualitative data are highly constructed by the research process in which they are collected, the notion of secondary analysis by other researchers than members of the original research team raises respondents' fears of misuse and misinterpretation of data. When data even are regarded as a product of the interaction between the particular researcher and particular participant, contextual knowledge is perceived to be only obtainable through personal involvement in the research at the time of its collection, i.e. in the interview itself. In other words, from this perspective being there (CORTI & THOMPSON, 2004; HEATON, 2004) is crucial for data analysis. [25]

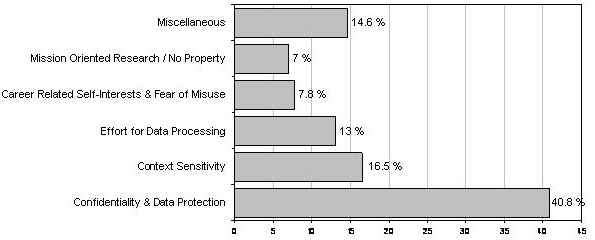

Scepticism about secondary analysis of qualitative data also produces consequences for the researchers' willingness to provide their own data for reuse. Having no data for reuse would withdraw the base for possible secondary analyses. Therefore objections have to be viewed from this perspective as well. About 20% (n=80) of the respondents refuse to provide their data in principle. Figure 2 shows the objections given by these respondents.

Figure 2: Objections against providing own data for secondary analysis9) [26]

When dealing with qualitative data, especially with interviews which are characterised by the content of private and sometimes sensitive information about the interviewees and their lives, the obligation to observe confidentiality and data protection is the prime problem seen by the researchers when asked about providing their data (see Figure 2). Such concerns of the researchers go beyond legal obligations, but regard ethical considerations related to the researcher's sense of responsibility for the interview relationship and the protection of the interviewee10). On the one hand, from this perspective anonymisation—especially of more biographical interviews—is viewed as an essential but not sufficient way to overcome confidentiality concerns; in addition, consent agreements with interviewees, as well as special agreements with re-users, or restricted access terms and conditions are required. On the other hand, from the perspective of a user anonymisation can lead to a loss of important context information and so damage the value of the data for secondary analysis (see: CORTI, DAY & BACKHOUSE, 2000; THOMSON, BZDEL, GOLDEN-BIDDLE, REAY & ESTABROOKS, 2005). [27]

Moreover, the Figure 2 indicates that also career-related self-interests and concerns about misuse of data play a role when researchers are asked to provide their data for reuse by others. Complementary to established research habits dominated by doing primary research, it is unusual to share data and by this means to enable others to benefit from own data instead of oneself. Further, the idea of giving away one's own data to other researchers for secondary use raises fears of exposure11) and criticism. From this viewpoint, a researcher conducting a secondary analysis could challenge the original study and its results. The challenge of one's own research results is seen rather in terms of a comparison with other's competing theoretical approaches than proof of analytic inaccuracy or faults. Used to having exclusive authority for interpretation, providing one's own data to others would mean losing this authority. The feeling of uncertainty about the aims of possible users due to a loss of control over own data appears even stronger in the responses of researchers who do not reject providing their data, but set conditions: About 30% required retention of control over data dissemination. [28]

Finally, in view of these many objections it is not surprising that researchers regard the effort for data processing to be of little use. The effort for data processing in order to prepare the data in an appropriate way for secondary analysis represents another major argument of the respondents against data provision (see Figure 2). This objection reflects a research practice without standard guidelines: For instance, more than 40% of the respondents stated that their interview data have either not been transcribed at all or at least not fully, and anonymisation of the data is insufficient for dissemination. Even if anonymised, the qualitative survey indicates a diversity of approaches, ranging from simply erasing ("blackening") identifying information in the transcripts, through replacing identifying information by pseudonyms, up to changing identifying information in terms of "putting people off the scent". Documentations are restricted to rather short study descriptions, as is common for scientific papers or research proposals and reports. [29]

After having illustrated the main problems and objections against secondary analysis based on the results of the feasibility study, it would be useful to contrast these with experiences researchers actually had with secondary analyses of qualitative data. [30]

3.3 Learning from experiences with secondary analysis of qualitative data

The illustrated problems and objections around secondary analysis among researchers pose challenges to qualitative social science research. As secondary qualitative data analysis is a relatively new common practice and has yet to be widely established, these open methodological questions have to be answered. For this purpose, performing (exemplary) secondary analyses—and maybe the consulting and training of different strategies of secondary analyses—would be the best way to approach not only the unfamiliarity with secondary analysis, but also the unresolved methodological problems. Indeed, as yet few experiences with secondary analysis of qualitative data can be found in the literature (see e.g. contributions in WITZEL, MEDJEDOVIĆ & KRETZER, 2008). [31]

But what about the experiences with secondary analysis of the respondents of the German feasibility study? As already noted at the beginning of the previous section, more than one third of the respondents stated in the questionnaire that they had already conducted a secondary analysis of qualitative data, i.e. 158 respondents. So some experience with secondary analysis of qualitative data does exist. In order to meet and analyse the elucidated doubts more in depth, some selected results concerning these experiences are presented in the following pages. These results are based on the narratives and accounts the respondents made in the interviews. It is maybe surprising that in the questionnaire survey only 33 (of the 158) respondents stated that they had difficulties during their secondary analyses. In the main, these respondents had problems in comprehending the data because of insufficient documentation and information on the context of data collection. The second major field of difficulties concerned incomplete data sets or deficiently processed data, like imprecise transcripts. But contrary to expectations one may have, these difficulties appeared also when researchers were reusing their own data. As time goes by, memories wane, intellectual and emotional involvement with the research fades (MAUTHNER et al., 1998); and against the background of a research practice without standard guidelines (for processing and documenting the research process and the collected data in a proper way), one's own collected data can then appear almost as "foreign". Thus, the acquainted issues of secondary qualitative data analysis can concern all research data, even those issues which are typically associated with (reusing) other researchers' data. [32]

Now to the interviews12). The assumed risk of decontextualisation is one of these issues. Examining the experiences especially with secondary analyses of other researchers' data, researchers actually state the absence of personal involvement in the interview situation as one issue. Using only transcripts, first-hand impressions about the general interview atmosphere, sound and expression of the voice of the interviewee, non-verbal expressions of the interviewee, and occurrences influencing the course of the interview are missing. As qualitative researchers who emphasise these basic elements of qualitative research, they had missed "not having been there". However, they do not consider this as an exclusive feature of secondary analysis, and least of all as an obstacle to secondary analysis, as it is common research practice to work in teams where several investigators are involved in data collection. In one case, the research team of the secondary analysis conferred with the primary researcher who had collected the data, and obtained by this means helpful pieces of missing meta-information on the interview data. In a second case, the secondary researcher could benefit from a detailed documentation on the framework of the interviews (including written notes of selection and approaching activities, interview location, living conditions of the interviewee, and memos on subjective impressions of the interviewer) which the primary researcher had drawn. These modes of contextualisation still left some questions, but as FIELDING (2004, p.99) argues: "Qualitative researchers have always been in the position of having to weigh the evidence". [33]

Given the great importance of contextualisation, confidentiality concerns can be a risk for secondary analysis—namely the anonymisation. The feasibility study involves one example where the secondary researcher worked with anonymised interview transcripts. Afterwards, the anonymisation emerged as distorting the analysis because the characteristics of the interviewees had been changed into false contextual information. Thus, the strong ambition of researchers to protect their interviewees by an anonymisation strategy in terms of "putting people off the scent" is rather less useful for secondary analysis. [34]

Besides the respondents who missed being there and who emphasise appropriate contextualisation, other cases show that contextualisation or its degree also depends on the research goal, as well as the theoretical and methodological approach of the secondary analysis. For instance, for interpretation methods which aim to reconstruct social structures following interaction processes (e.g. "sequential analysis", see e.g. MAIWALD, 2005), contextual knowledge beyond the interaction or the "text" is explicitly excluded from interpretation. [35]

However, as a common ground of these different approaches of analysis, complete and detailed transcriptions of the interviews emerged as an essential precondition for secondary analysis. It later transpired that even the researcher's own data turned out to be insufficiently transcribed, so that the researcher had to work parallel with the audiotapes. [36]

Maybe due to the fact that the experiences mainly draw on informal ways of data sharing within acquainted circles, no special problems occurred regarding the first steps of data selection. The researchers of the secondary analyses either were in contact with members of the primary research team which had collected the data, or had access to all research documents and records. Besides those secondary analyses actually conducted, there were also cases where initially interested researchers decided not to use data for secondary analysis, although the topic of the data set had seemed suitable at first glance. The ultimate decision about the usability of a particular data set can only result from a close examination: In one case this decision was made after examining some transcripts more closely. In another case the researchers based their decision on descriptions of case studies which they found in publications of the project. [37]

A further question is to what extent the specificity of qualitative research (with its particular research aims and objectives) constricts the feasibility of a secondary analysis. The interview survey shows that the experiences regarding the depth and breadth of the data were indeed quite different. On the one hand researchers came up against limitations concerning the depth of the primary data. Secondary analysis generated results for the new analytic focus applied to the data, but not in an exhaustive sense. On the other hand, there are contrasting experiences where data had even more potential for analysis than expected. The data fit certainly depends in the first instance on the focus and the richness of the particular data itself. [38]

But data fit also depends on how the analyst is approaching secondary analysis. For instance, in one case the analysis was characterised by a bottom-up approach and an iterative research procedure (as grounded theory methods typically provide; see GLASER & STRAUSS, 1967). At the starting point the research team conducted a secondary analysis of a pre-existing (and "foreign") data set of interview transcripts. The secondary analysis was one step; namely the first in gaining scientific insight. The research team approached the data with no definite research question. In dealing with the data the researchers identified new aspects and assumptions which had not been explored by the primary analysis. Based on new hypotheses, they decided to undertake their own supplementary data collection and so they conducted further interviews. From my point of view, this example with its rather open and bottom-up approach contrasts an approach where secondary analysis serves for a ready-made question or proving predefined theoretical concepts which therefore requires data fit in a much more rigorous sense. [39]

Moreover, the interview survey indicates not only that the specificity of qualitative research constitutes no barrier for secondary analysis, but contrariwise that secondary analysis can offer the potential even to overcome the specificity of its insights, and provides the opportunity for generalisability and a cumulative research (see also: FIELDING, 2004; HAMMERSLEY, 1997). One respondent was conducting an assorted analysis (combined primary research with secondary analysis), drawing on different data sets with different populations. Comparing these populations, the research team assumed the possible development of a typology and generalisation of theoretical concepts. [40]

Having presented examples concerning the difficulties a researcher might face during a secondary analysis of qualitative data,—as far as data of others is concerned—the first precondition still remains: the willingness of the data collector to provide the data. Therefore, researchers' fears of exposure and of criticism can be a barrier to secondary analysis. Here indeed examples can be found which hint at a certain amount of risk. Even within a primary research context where several researchers or research teams deal with the same or similar research question, conflicts concerning interpretation may occur. On the opposite side one can find researchers who consider different perspectives or approaches to be interesting and an advantage because they can lead to a more comprehensive picture of the researched object. And one further interview of the study shows that in addition the secondary researcher also could communicate his/her results to the primary researcher. While the process was in this case not free of conflicts, these were not of a principle nature and did not refer to interpretation. Rather than challenging his work, the primary researcher had the impression that the secondary analysis enhanced its value. [41]

So, what conclusions can be drawn from the presented issues and experiences for the feasibility of secondary analysis of qualitative (interview) data and its establishment in the German scientific community? [42]

The feasibility study has surveyed experts, namely qualitative researchers. Their views, ideas and problems referring to secondary analysis of qualitative data have to be considered as central conditions, if the aim is to open up the horizon for the theory and practice of secondary analysis. Many views and objections have to be seen against the background of a lack of experience, necessitating work to increase familiarity with this new method and sensitise researchers for the potentials of secondary analysis. Maybe one way of supporting the progress of a new valuation of secondary analysis in the prevailing research culture is by conducting exemplary secondary analyses. Some objections are not restricted to secondary analysis, but concern qualitative research in general; and in this context are discussed rather constructively. Dealing with methodological issues of secondary analysis then also means advancing qualitative methods overall. [43]

Especially the issues of contextualisation and data fit do not constitute insurmountable obstacles. As respondents' experiences with secondary analyses of other researchers' data have shown, "not being there" is a fact—but not a barrier. In this regard, the assurance of traceability of the research context is a helpful condition (via detailed and complete interview transcriptions as well as detailed documentation on the framework, data collection and the study as a whole). To what extent, then, the data and the aim of the secondary analysis fit depends in the first instance on the focus and richness of the particular data, but also on how the researcher is approaching secondary analysis, or in other words: "the interaction with textual data" (THORNE, 1994, p.273). [44]

Further questions, such as the facilitation of data access and the development of standard guidelines for data processing—which would serve also primary researchers—could best be solved by a central archive and data service (for basic considerations about an archive concept see MEDJEDOVIĆ et al., 2010). Taking the aforementioned into account, there are also some more serious objections for which solutions have not yet been found. For instance, it will be hard to change established research habits which form prevailing careers. How to meet researchers' fears of exposure and criticism, if not by providing a forum for a free and open debate—certainly quite a controversial one?13) [45]

1) See: http://www.gesis.org/en/institute/gesis-scientific-sections/data-archive-for-the-social-sciences/ [Accessed: September 6, 2010]. <back>

2) See: http://www.lebenslaufarchiv.uni-bremen.de/ [Accessed: September 6, 2010]. <back>

3) Project "Archivierung und Sekundärnutzung qualitativer Daten – eine Machbarkeitsstudie", 2003-2005. Team: Prof. Karl F. SCHUMANN, Dr. Andreas WITZEL, Irena MEDJEOVIC, Diane OPITZ, Britta STIEFEL (Bremen); Prof. Wolfgang JAGODINSKI, Dr. Ekkehard MOCHMANN, Reiner MAUER (Cologne). <back>

4) For further results of the quantitative survey see OPITZ and MAUER (2005), MEDJEDOVIĆ et al. (2010). <back>

5) The reported, mainly quantitative results in this section have been published in: OPITZ and MAUER (2005), WITZEL and MAUER (2012) and MEDJEDOVIĆ et al. (2010). <back>

6) The presentation and discussion of the empirical results in this part draws on the interpretations of the quantitative data complemented by the qualitative results. <back>

7) Indeed—as HEATON (1998, p.10) already pointed out—it is not easy to decide "where primary analysis stops and secondary analysis starts". <back>

8) When the researchers were asked to reflect on the preconditions for reusing (foreign) interview data, the issue gains more importance; as well as in the context of providing one's own data for secondary analysis: see Figure 2. <back>

9) "No property" means that researchers conducted the research on behalf of a third party. Therefore the researchers have no property in the data and cannot decide on its (further) use. <back>

10) KUULA (2012) describes researcher's perception of the interview relationship as emotional and private, which contrasts the interviewee's perception of the same relationship as a rather institutional interaction. <back>

11) Fears of exposure and misinterpretation have already been recognised as one barrier to archiving qualitative data (CORTI, 2000, p.25; CORTI & THOMPSON, 2004, p.337). <back>

12) Due to the fact that the expert interviews were conducted in German language, this article contains no direct citations from the interview transcripts. <back>

13) In the UK, exposure of the arguments to the literature has enabled full discussion and now archiving and sharing is quite routine practice. Further, many post graduate courses in the UK are covering secondary analysis of qualitative data. <back>

Åkerström, Malin; Jacobsson, Katarina & Wästerfors, David (2004). Reanalysis of previously collected material. In Clive Seale, Giampietro Gombo, Jaber F. Gubrium & David Silverman (Eds.), Qualitative research practice (pp.344-357). London: Sage.

Corti, Louise (2000). Progress and problems of preserving and providing. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung / Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 1(3), Art. 2, http://nbn-resolving.de/urn:nbn:de:0114-fqs000324 [Date of Access: June 22, 2006].

Corti, Louise (Ed.) (2006). Making qualitative data more re-usable: issues of context and representation. Methodological Innovations Online, 1(2), http://erdt.plymouth.ac.uk/mionline/public_html/viewissue.php?id=2 [Date of Access: September 9, 2010].

Corti, Louise, & Thompson, Paul (2004). Secondary analysis of archived data. In Clive Seale, Giampietro Gobo, Jaber F. Gubrium & David Silverman (Eds.), Qualitative research practice (pp.327-343). London: Sage.

Corti, Louise; Day, Annette & Backhouse, Gill (2000). Confidentiality and informed consent: issues for consideration in the preservation of and provision of access to qualitative data archives. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung / Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 1(3), Art. 7, http://nbn-resolving.de/urn:nbn:de:0114-fqs000372 [Date of Access: March 6, 2006].

Corti, Louise; Witzel, Andreas & Bishop, Libby (Eds.) (2005). Sekundäranalyse qualitativer Daten / Secondary analysis of qualitative data. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung / Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 6(1), http://www.qualitative-research.net/index.php/fqs/issue/view/13 [Date of Access: Aug. 3, 2005].

Fielding, Nigel (2004). Getting the most from archived qualitative data: epistemological, practical and professional obstacles. International Journal of Social Research Methodology, 7(1), 97-104.

Glaser, Barney G., & Strauss, Anselm L. (1967). The discovery of grounded theory: Strategies for qualitative research. New York: Aldine.

Hammersley, Martyn (1997). Qualitative data archiving: some reflections on its prospects and problems. Sociology, 31(1), 131-142.

Heaton, Janet (1998). Secondary analysis of qualitative data. Social Research Update, 22, http://www.soc.surrey.ac.uk/sru/SRU22.html [Date of Access: June 8, 2006].

Heaton, Janet (2004). Reworking qualitative data. London: Sage.

Hinds, Pamela; Vogel, Ralph & Clark-Steffen, Laura (1997). The possibilities and pitfalls of doing a secondary analysis of a qualitative data set. Qualitative Health Research, 7(3), 408-424.

Kuula Arja (2012/submitted). Un nouveau regard sur l'éthique. In Magdalini Dargentas, Mathieu Brugidou, Dominique Le Roux & Annie-Claude Salomon (Eds.), L'analyse secondaire en recherche qualitative: une nouvelle pratique en sciences humaines et sociales. Paris: Lavoisier.

Maiwald, Kai-Olaf (2005). Competence and praxis: sequential analysis in German sociology. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung / Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 6(3), Art. 31, http://nbn-resolving.de/urn:nbn:de:0114-fqs0503310 [Date of Access: Aug. 31, 2006].

Mauthner, Natasha S.; Parry, Odette & Backett-Milburn, Kathryn (1998). The data are out there, or are they? Implications for archiving and revisiting qualitative data. Sociology, 32(4), 733-745.

Medjedović, Irena; Witzel, Andreas; Mauer, Reiner & Watteler, Oliver (2010). Wiederverwendung qualitativer Daten. Archivierung und Sekundärnutzung qualitativer Interviewtranskripte. Wiesbaden: VS Verlag.

Opitz, Diane & Mauer, Reiner (2005). Erfahrungen mit der Sekundärnutzung von qualitativem Datenmaterial – Erste Ergebnisse einer schriftlichen Befragung im Rahmen der Machbarkeitsstudie zur Archivierung und Sekundärnutzung qualitativer Interviewdaten. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung / Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 6(1), Art. 43, http://nbn-resolving.de/urn:nbn:de:0114-fqs0501431 [Date of Access: June 8, 2005].

Thomson, Denise; Bzdel, Laura; Golden-Biddle, Karen; Reay, Trish & Estabrooks, Carole A. (2005). Central questions of anonymization: a case study of secondary use of qualitative data. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung / Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 6(1), Art. 29, http://nbn-resolving.de/urn:nbn:de:0114-fqs0501297 [Date of Access: February 22, 2006].

Thorne, Sally (1994). Secondary analysis in qualitative research: issues and implications. In Janice M. Morse (Ed.), Critical issues in qualitative research methods (pp.263-279). London: Sage.

Van den Berg, Harry (2005). Reanalyzing qualitative interviews from different angles: The risk of decontextualization and other problems of sharing qualitative data. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung / Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 6(1), Art. 30, http://nbn-resolving.de/urn:nbn:de:0114-fqs0501305 [Date of Access: February 21, 2006].

Witzel, Andreas (2000). The problem-centered interview. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung / Forum Qualitative Social Research, 1(1), Art. 22, http://nbn-resolving.de/urn:nbn:de:0114-fqs0001228 [Date of Access: April 3, 2005].

Witzel, Andreas & Mauer, Reiner (2012/submitted). Considérations préalables à la création d'un centre d'archives de données qualitatives. In Magdalini Dargentas, Mathieu Brugidou, Dominique Le Roux & Annie-Claude Salomon (Eds.), L'analyse secondaire en recherche qualitative: une nouvelle pratique en sciences humaines et sociales. Paris: Lavoisier.

Witzel, Andreas; Medjedović, Irena & Kretzer, Susanne (Eds.) (2008). Secondary analysis of qualitative data / Sekundäranalyse qualitativer Daten. Historical Social Research, 33(3).

Irena MEDJEDOVIC, Dipl.-Psych., is head of the research unit "Qualification and Competence Research" of the Institute Labour and Economy (IAW) at the University of Bremen. Until December 2010, she worked at the Archive for Life Course Research where she was involved in establishing a national service infrastructure for archiving qualitative data. Her current major research interests include vocational education and training research, qualification research, occupational life course research, and methods, especially qualitative methods and methodological issues of secondary qualitative data analysis.

Contact:

Irena Medjedović

Forschungseinheit Qualifikationsforschung und Kompetenzerwerb

Institut Arbeit und Wirtschaft

Universität Bremen

Wilhelm-Herbst-Straße 7

28359 Bremen, Germany

Tel.: +49 / (0)421 / 218 4387

Fax: +49 / (0)421 / 218 4560

E-mail: imedjedovic@uni-bremen.de

URL: http://www.iaw.uni-bremen.de/ccm/navigation/forschungseinheiten/fequa/

Medjedović, Irena (2011). Secondary Analysis of Qualitative Interview Data: Objections and Experiences. Results of a German Feasibility Study [45 paragraphs]. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung / Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 12(3), Art. 10,

http://nbn-resolving.de/urn:nbn:de:0114-fqs1103104.