Volume 13, No. 1, Art. 9 – January 2012

The Self-Conscious Researcher—Post-Modern Perspectives of Participatory Research with Young People

Claire McCartan, Dirk Schubotz & Jonathan Murphy

Abstract: Research in young people by young people is a growing trend and considered a democratic approach to exploring their lives. Qualitative research is also seen as a way of redistributing power; with participatory research positioned by many as a democratic paradigm of qualitative inquiry. Although participatory research may grant a view on another world, it is fraught with a range of relationships that require negotiation and which necessitate constant self-reflection. Drawing on experiential accounts of participatory research with young people, this paper will explore the power relationship from the perspective of the adult researcher, the young peer researcher and also that of the researched. It will explore the self-conscious exchange of power; and describe how it is relinquished and reclaimed with increasing degrees of compliance as confidence and security develops. Co-authored by a peer researcher and adult researchers, this paper will illustrate a range of practical examples of participatory research with young people, decode the power struggle and consider the implications. It will argue that although the initial stages of the research process are artificial, self-conscious and undemocratic it concludes that the end may justify the means with the creation of social agency knowledge, experience and reality.

Key words: peer research; power; social action; participatory methods

Table of Contents

1. Introduction

2. Why Involve Young People in Participatory Research?

3. Power Relationships in Participatory Research

3.1 The research projects

3.2 Structural and social hierarchies

3.3 Participation capital

3.4 Emotional power

4. Experiences of the Power Continuum—Struggle, Exchange and Redistribution

4.1 The conscious exchange of power

4.1.1 Reciprocity—money, experience, skills and experience

4.1.2 Training

4.2 Relinquishing power

4.2.1 Challenges for the adult research

4.3 The researched

5. Being Post-Modern/Conclusion

Participatory research methods are increasingly popular and can be seen as an effective and more inclusive way of engaging excluded or hard to reach populations in the research process (WRIGHT, CORNER, HOPKINSON & FOSTER, 2006; COADY et al., 2008). Whilst undertaking a feasibility study on behalf of the Scottish Executive it was noted that there were more than 50 ongoing participatory research projects in the UK alone (BROWNLIE, 2009). Another Scottish study describes the change in perspective in research with children and young people from research on children to research with children and, more recently, research which seeks to empower children (BORLAND, HILL, LAYBOURN & STAFFORD, 2001). The global framework for the involvement of children and young people in decision making is provided by the United Nations Convention for the Rights of the Child from 1989, which has also been used to justify participatory research practice. There is an increasing desire in government to acknowledge and encourage the voice of children and young people in policy making and hence ultimately in social research. This is significant because acknowledgment by government means that government will (or at least claims it will) seriously look at work that involves lay researchers in order to inform policy making. One of the examples of this in Northern Ireland was the establishment of the Participation Network in 2006, which was set up in order to provide training and consultation to the public sector on the involvement of children and young people in decision making processes. This follows the legal framework set by the Ten-year Strategy for Children and Young People in Northern Ireland, which vows to create "a culture where the views of our children and young people are routinely sought in matters which impact on their lives" (OFMDFM, 2006, p.13). [1]

Participatory research with children and young people is considered to have a number of different positive outcomes. It is a means of empowering the excluded, accessing richer data and can enable the effective implementation of findings (JAMES & CHRISTENSEN, 2008; JAMES & PROUT, 1998; CLARK, HOLLAND, KATZ & PEACE, 2009; FLICKER, MALEY, RIDGLEY, BISCOPE & LOMBARDO, 2008). This article will draw on the experiences from different projects and reflect on the peer researchers' personal accounts of the research process: Attitudes to Difference (NCB NI & ARK/YLT, 2010); Out of the Box (KILPATRICK, McCARTAN & McKEOWN, 2007) and Cross-Community Schemes (SCHUBOTZ et al., 2008). [2]

For the purpose of differentiating between the two different profiles of the researchers under examination, the university-based salaried researcher will be referred to as the "adult researcher" and the younger sessional researcher as the "peer researcher" from here on in. [3]

2. Why Involve Young People in Participatory Research?

There is now little disagreement that listening to children and young people can improve policy delivery in matters affecting them (CAVET & SLOPER, 2004; COYNE, 2005), and as stated above, the UNCRC and respective national, regional and local legislative frameworks provide the opportunity for young people to get involved if they wish. The question remains to what extent young people's voices are really listened to or just tokenistically? [4]

Young people are often employed as peer researchers because they have skills that adult researchers do not possess. They speak the same language as the research participants, they have access to hard-to reach groups and they have first-hand insights into matters affecting young people, as they are often affected by these issues themselves. What young people do not possess and have to be equipped within a relatively short period of time are the research skills required to elicit these lived experiences, record them appropriately and to analyze the data collected. It is reasonable to argue that it is impossible to train lay researchers rapidly in statistical research methods and complex qualitative analysis. It is equally reasonable to contend that young lay researchers' experiences and skills are best used in eliciting and exploring lived experiences of their peers and helping to make sense of these experiences. [5]

As far back as 1967, the advocates of grounded theory (GLASER & STRAUSS, 1968 [1967]) promoted multi-disciplinary teams for data analysis, and they emphasized that the involvement of laymen and women in these teams would not be a hindrance but rather a desirability. It is no coincidence that the formulation of natural codes is the first step in the data analysis procedure of grounded theory. GLASER and STRAUSS argue that it is this first step of coding data that expert social researchers have most difficulty with because they may be pre-occupied with the baggage of social theory that they have acquired over the years. Peer researchers do not carry this baggage. However, participatory research projects are not exempt from demonstrating scientific rigor. According to GLASER and STRAUSS (1968 [1967]), scientific rigor can be measured against the four criteria of fitness, understanding, generality and control. GUBA and LINCOLN (1981) introduced the terms of credibility, fittingness, auditability and confirmability to the debate of rigor in qualitative research. Auditability, which refers to the need to document a decision trail and to lay open the data analysis process so that other researchers can confirm the findings, seems to be critical for participatory research projects, in particular as qualitative research is often considered to be a more emotive, human response, presenting an accessible narrative for illuminating stories behind statistics. The role of the qualitative researcher, including peer researchers, is therefore to become a conduit through which the meaning can be explained. [6]

3. Power Relationships in Participatory Research

"The focus of participative research should be as much about disempowerment therefore as empowerment" (JONES, 2000, p.37).

There are different rationales and motivations for undertaking qualitative research; it may access areas of study that quantitative research are less amenable, it can help generate theory and concepts as opposed to testing hypotheses and it can provide opportunities to understand social phenomena in a natural setting by exploring meanings, experiences and views (POPE & MAYS, 1995). One of its strengths is often seen in the way of redistributing power, enhancing the role of the researched and a means of hearing society's hidden voices. Paulo FREIRE's work (1996 [1986]) describes how oral and life history methodologies can help people develop historical awareness and understanding of their lives enabling them to view their lives differently. The growing body of participatory disability research also demonstrates the mechanisms of reclaiming personal histories and providing contextual understanding which can lead to individual and collective empowerment (WARD, 1997; GILLMAN, SWAIN & HEYMAN, 1997; ATKINSON, 2004). The contribution of feminist researchers such as Janet FINCH (1999 [1984]) in our understanding of power relations in interview situations and social research in general cannot be underestimated. [7]

Research participants are sometimes unaware of their own power, perceiving that researchers already have more knowledge (GIBSON-GRAHAM, 1994). Participatory research has the potential to do more than investigate and elucidate phenomena; the learning processes involved have independent merit. The researched becomes the researcher; afforded the opportunity to identify the research questions, ask and help answer them. Participant researchers having had a role in gathering data, can also influence how it is subsequently distributed and implemented. This can often lead to innovation, moving away from traditional academic methods to potentially more relevant and meaningful outputs (for example see CAMPBELL & TROTTER, 2007). [8]

The physical and intellectual process of participatory research has the potential to penetrate much deeper and go well beyond the actual production of research findings. The social worlds of the adult researcher and the researched can be very different with both partners facing exclusion on a number of levels, for example the social hierarchies of sex, gender and age. Participatory research methods create a means by which the social interface between these arenas can temporarily or permanently be altered. It can empower both partners, creating an insight into another world. Participatory research can help create an alternative access point for both the adult researcher and the peer researcher, circumventing traditional structures and relationships, allowing for social exchange, the retrieval of richer data and greater understanding. It also requires the researcher to think differently, calls for them to strip down the aims and objectives, view it from alternative perspectives and reconsider how the interface between research and real life is perceived and understood. It can pervade other people's lives on the margins, making research accessible and relevant to their lives also, removing a layer and strata which may have blocked access in the past. [9]

In our view participatory research can be a desirable way to conduct qualitative research enabling the enquirer the chance to explore an environment in partnership with a gatekeeper who has access to the phenomenon under investigation. However, it also has the potential to exploit both its participants and researchers, failing to produce robust research which serves its partners with integrity and with little or no value to inform policy and practice. By becoming more flexible and considering the fluid nature of the power relations at play, real value can be drawn from participatory research. [10]

An illustration of some of the power relationships is drawn from three different projects involving peer researchers in Northern Ireland. [11]

The first project (Attitudes to Difference) was undertaken by the National Children's Bureau (NCB) in conjunction with ARK, a social research initiative by Queen's University Belfast and the University of Ulster. The research explored attitudes to and contact with people from minority ethnic communities in Northern Ireland (NCB NI & ARK/YLT, 2010). Attitudes to Difference was funded by the Office of the First Minister and Deputy First Minister of the Northern Ireland government (OFMDFM) and was a mixed-methods project which involved twelve 15-16 year old peer researchers in the qualitative elements of the research, namely conducting focus groups and one-to-one interviews with young people. The peer researchers were also involved in the data analysis and dissemination of the findings. [12]

The second project (Out of the Box) involved twelve peer researchers tracking a longitudinal sample, over two and a half years, of young people excluded or at risk of exclusion from school and investigated the outcomes following different types of alternative education provision (KILPATRICK et al., 2007). This was funded by the Department of Education in Northern Ireland and OFMDFM. [13]

The final project (Cross-Community Schemes) (SCHUBOTZ et al., 2008) used mixed methods to explore young people's attitudes to, and participation in, cross-community schemes in Northern Ireland. Eight 16-year olds were recruited as peer researchers as a follow-up to the Young Life and Times survey run by ARK (2009). It was funded by the EU Programme for Peace and Reconciliation for Northern Ireland and the Border Regions of Ireland (PEACE II). [14]

3.2 Structural and social hierarchies

In the main, participatory research projects follow the same logic as any other research project. Significant levels of intellectual energy are required before a study can even commence—whether this is by responding to a tender document or proactively writing a funding application to undertake a research project. There are some examples of young people initiating and planning research projects themselves that they then conduct themselves, but these are in the clear minority. Thus, the actual process of developing a research proposal, applying for and securing funding helps contribute to largely unavoidable hierarchies from the outset. Most research questions are formulated and studies designed long before the peer researchers are recruited and with some exceptions only those with an academic track record have a reasonable chance of securing funding from reputable sources. More often, participatory projects only become participatory once the study design has been ratified by those providing the money. This crystallizes the argument that the participation agenda can be tokenistic (see KELLETT, 2005) due to the relatively inflexible funding structure for academically sound research. [15]

The participation agenda in research in the main part has been driven by both the academic community and the rights base agencies that lobby policy makers. The direct policy orientation which is an essential element of participatory research sets it apart from non-applied academic research and blue-sky thinking in which the benefits of lay participation are less obvious. Nonetheless, the role of the professional researcher, having a clear focus on the aims and objectives as well as the deliverables and time-line of the research project, contrasts sharply with the position of most peer researchers joining the project. Whilst many demonstrate an interest or even passion about the subject area they are about to research and may feel strongly about their right to be listened to in matters that affect them, lay researchers have few concrete preconceptions or expectations about the specifics of the research project they are embarking on (see KILPATRICK, McCARTAN, McALISTER & McKEOWN, 2007 for examples). The professional researcher works within a familiar environment and has a set of aims and objectives he or she works towards which tends to place the professional researcher in a more powerful position, intentional or not. Adult researchers work within an acquired and widely observed and monitored framework of procedures and protocols relating to research activity. Ethical codes, bureaucracy and data protection commitments underpin any plan of work and the administrative structures which ensure that data is collected and stored appropriately. Adult researchers will have identified the research question they wish to answer and considered all the implications of their methodological approach before embarking on the study; young people unfamiliar with the modus operandi will not have prepared in this way. [16]

The area of research is also filled with technical references and assumed knowledge and terminology does much to exclude and alienate those who are outsiders to the research community. Academic institutions follow the same rules and principles, and suffer the same restrictions, as other large professional and bureaucratic organizations (WEBER, 1968 [1922]). Academia has developed a professional code of practice that regulates the rules and standards of research to defend the rights of research participants and aims to protect its members (i.e. academics) whilst inevitably and paradoxically at the same time restricting their professional freedom and flexibility. Academia has developed a particular language that is specific to this field of practice. The use of a lay-friendly rather than high-level academic language within projects involving peer researchers is a necessity to attempt to rebalance inequalities. However, simply rethinking language does not necessarily redistribute power. This only deals with the interface between the peer researcher and the adult researcher, the encounter between the peer researcher and the world they negotiate is more complex. One difficulty of co-opting young people as citizen researchers is when they are still competing to be recognized as citizens, "[y]oung people still lack the legitimacy that young people now have as research subjects" (BROWNLIE, 2009, p.711). This alludes to the fairly recent developments in the sociology of childhood in which children and young people have been recognized as actors in their own right. [17]

In our experience of working with young people, the immediate and instant hierarchies around social constructs require negotiation—be it on the grounds of the age/experience differential, gender and class. A young peer researcher entering the research context will invariably have less experience as a researcher than their adult co-researcher. The adult/adolescent relationship also has particular significance, as adolescence is a complex developmental period where the rules and boundaries between adults are tested and renegotiated as young people make their transition to adulthood (BERNSTEIN, 1980; LARSON & RICHARDS, 1994; LEIBENLUFT, McCLURE, NELSON & PINE, 2005). THOMAS (2007) links the existing subordination of young people and the view that they are "citizens in waiting" to BOURDIEU's concept of habitus as well as his ideas of social and cultural capital. Both of these are important theoretical considerations when thinking about the motivations to, and consequences of, involving young people in decision-making and participatory research, as THOMAS explains in his article. The research relationship presents an unfamiliar environment in which to present one's adolescent self. Contrary to most school and home environments where rules are predominantly set by adults and where young people are often afforded little room to negotiate these rules, participatory research projects recruit adolescents as experts. [18]

Research involving young people is increasingly popular and can help access the hard to reach, but the potential for exploiting young people has been well evidenced in the literature (TROTTER & CAMPBELL, 2008; McLAUGHLIN, 2006; SMITH, MONAGHAN & BROAD, 2002). One area less well explored is the power relations among peers themselves and how trust and confidence within a group can be manipulated and exploited. Anna CONNOLLY (2008) challenges the participation agenda; in her research with young women excluded from school, she contends that participatory research with young people is "at best unfeasible and at worst, unethical" (p.205). By co-opting young people as researchers, this places them in an elevated position among their peers, emulating the adult/child research relationship. SMITH et al. (2002) also alert caution that young people have the potential to misuse power and knowledge within the research situation (a debatable yet significant point to also consider here is the practical issue of data management and peer researchers' compliance with data protection legislation). Peer researchers approach the peer group with changed roles, responsibilities and identities, some of which are not clearly identifiable or understood by their peer group. The power differential is challenged and can be somewhat precarious. JONES (2000) explains this in more detail, participatory methodologies do not necessarily vest power in the researched nor may the research participants seek or necessarily need to be empowered. [19]

Most peer researchers already have some degree of power displayed by the simple act of having the confidence to volunteer their skills and abilities or demonstrated by the power bestowed by gatekeepers who trust these competencies. In the Attitudes to Difference project (NCB NI & ARK/YLT, 2010) the power differential became acutely personal following the initial training session. Overall, twenty young people from five different schools who had applied to become peer researchers had participated in the research methods training, but it was clear that only ten could be selected as peer researchers, and gender, ethnicity and school quota would be applied within reason. Following the training session, the merits of all peer researcher applicants were discussed by an established school-based peer group of 16-17 year olds who had participated in the training. In their discussion, they selected those who they thought would be appropriate recruits for the research project. They identified those who they thought were "up to the task" and rejected those who they felt wouldn't be capable of carrying out the work of the peer researcher. There was also the opinion expressed that the project would be "doomed" if certain individuals were picked. The young people felt knowledgeable and equipped to make this decision on account of their own strengths and abilities in comparison to the other applicants. Although they had no influence over who was selected to join the research team, they were confident that they would be represented in the final group. Once the names of the peer researchers were announced, some applicants felt the adult research team had made a mistake, compelled to adhere to politically correct positive discrimination (on academic grounds, not sectarian). Securing a position on the team had become increasingly important. It was only when the project got underway that some peer researchers realized that they had misjudged other participants who had skills and qualities highly effective for the role of peer researcher, which the adult research team had obviously identified. This is an example of a one-sided non-confrontational struggle but clearly illustrates the perceptions of power and the desire to exchange it. Roger SMITH and colleagues (2002) highlight the implications that this power struggle can have for data validity and reliability and the inherent danger of over-ruling the professional researcher. [20]

WILES, CHARLES, CROW and HEATH (2006) explore the concept of consent and negotiation drawing on examples from peer research within academia. They describe the paternalistic relinquishment of intellectual responsibility based on the peer group membership, by giving the participants the opportunity to veto or corroborate the data post-interview. The points the authors make have relevance for the peer researcher-adult researcher relationship. The realm of consent and negotiation is different with peer researchers as group membership (based on age, gender or sport, leisure or social activities) is capitalized on and young people may not have considered all the permutations of the research relationship for their group membership. [21]

Most researchers can be exposed to emotional risk (DICKSON-SWIFT, JAMES, KIPPEN & LIAMPUTTONG, 2009; COLES & MUDALY, 2010) and at times may reveal more about themselves than they anticipated (SMITH et al., 2002). Examples of this process were quite evident on peer research project on community participation in Northern Ireland (SCHUBOTZ et al., 2008). Peer researchers hosted focus groups within their youth groups; existing friendships established over time had created a safe and open environment to discuss some difficult issues. However, this reliance on existing friendships and safety exposed some extreme views around religion and culture. When challenging issues are raised, peer researchers and their fellow participants should be given the opportunity to consider the longer term implications of having access to this knowledge. [22]

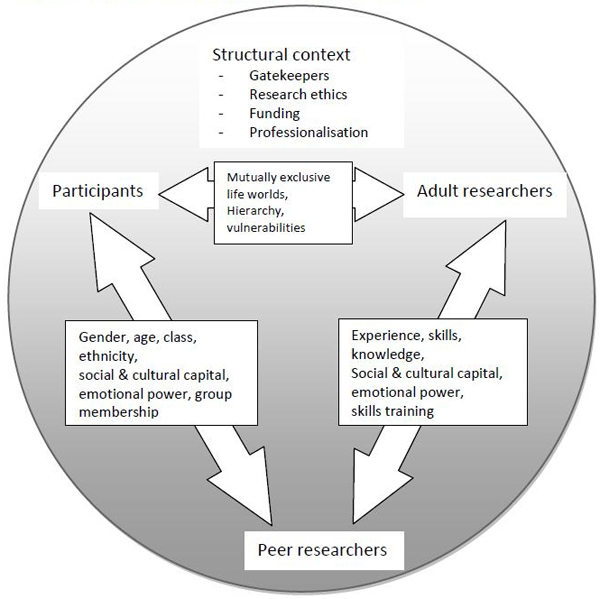

Some of the subject matter and disclosure during case study interviews during the Out of the Box fieldwork was distressing for the peer researchers and participants (KILPATRICK et al., 2007). Although this can be considered cathartic and an altogether necessary process for participants (ENGLAND, 2005; McLEOD, 1994) the adult research team had an added responsibility of placing the peer researchers in a position of vulnerability. As DENTITH, MEASOR and O'MALLEY (2009) admit, "research is a very human act" (p.164). The research team had to rely on appropriate support mechanisms to offer signposting support to young people in need of help, but also emotional support to the peer researchers having to deal with these difficult issues. [23]

A female peer researcher on Out of the Box project subsequently discovered that one of the research participants that she had been interviewing over a period of two years had dropped out of the study following a problem with alcohol misuse. This was difficult for her to deal with, she had had a

"mere gut feeling that something wasn't right. On reflection this is a hard thing for me to accept. After a lengthy discussion with my fellow peer researcher, I accept that I could have done nothing more, if she had not disclosed any information, how can I act upon it?" (KILPATRICK et al., 2007, p.32). [24]

This experience demonstrates one of the benefits of involving young people in research, in terms of their personal development and life skills—namely, the learning that they cannot control everything, nor are they responsible for everything that happens. [25]

4. Experiences of the Power Continuum—Struggle, Exchange and Redistribution

4.1 The conscious exchange of power

4.1.1 Reciprocity—money, experience, skills and experience

The appropriate payment of peer researchers is discussed in the literature and Sarah NEILL (2005) refers to some of the issues raised about payment, including inducement and coercion. Most concede that it helps to preside over the peer researcher contract, establishes some level of expectation and places some value on the important role they play. However, it must also be considered as both a motivating and mitigating force. [26]

From the outset power must have the potential to be exchanged between partners—the professional research team wants access to rich data using innovative methods from highly involved and committed peer researchers. The peer researchers do have some element of power at this stage of the relationship as they are well placed to deliver these objectives. In terms of reciprocity, the benefits of their involvement need to be clear and accessible and these are invariably packaged as financial reward, CV/application form enhancement, preparation for the higher education/labor market and the opportunity to make a difference (usually in this order). [27]

Paying peer researchers is important on a number of levels. It recognizes and values their input in a meaningful and relevant way, it can widen the appeal of involvement to a more diverse pool of recruits (not only driven by altruism) and attempts to establish a parity of esteem between adult and peer researchers. [28]

For the peer researcher co-author of this article, the potential to earn money was pivotal to his involvement. He was interested in research and the experiences of ethnic minorities in Northern Ireland but the fact that money was available really helped decide whether to become involved or not; payment was the motivating factor that gave him the "push" to make the effort to get involved. [29]

Enabling young people to develop the knowledge, skills and responsibility to help conduct research signals the conscious exchange of power, and indeed moves towards working with rather than on young people. It has been suggested that power sharing in research can also enable young people to acquire an insight into more equitable social relationships (FLICKER et al., 2008), [30]

In Attitudes to Difference, once fieldwork was underway, peer researchers were required to facilitate focus group sessions with fellow 6th formers in a local school. For some, this was nerve wracking at first, trying to develop the confidence to work with a group of young people of a similar age. By drawing on the skills and strategies during the training session, peer researchers' confidence grew and it wasn't long before the group was engaged. The training session covered the difficulties that might arise and peer researchers felt they had been equipped to cope. [31]

The research team, in providing appropriate and effective training, enabled young people in developing confidence. Simultaneously, the peer researchers belonged to the social group and had greater proximity to them potentially gave them more power than the adult researchers. During the focus groups, the peer researchers felt they managed proceedings well and appreciated the adult researchers taking more of a back seat role. [32]

By belonging to the peer group, the peer researcher moves into a position of privilege, enabling participants to be open and honest in their opinions. Some of the discussion at the focus groups centered on minority ethnic groups and clearly the adult researchers found some of the more extreme views uncomfortable. Their feelings were discussed at the team debrief at the close of the session. As a peer researcher, this was an illustration of how impartial the role of peer researcher can be because of their cultural proximity to the young participants. At times, the adult worker physically recoiled at some of the statements made, but peer researchers weren't surprised. They could see the participants' point of view and had greater empathy; it wasn't so startling that somebody had these opinions. This demonstrates well, the peer researcher's position; that participants feel comfortable expressing strong opinions among their peers without fear of recourse. [33]

A male peer researcher on Out of the Box, also spoke about being "privileged," both by being given access to learn more about young people's lives but also working with the adult researchers. Of the research team he felt "I also had the privilege of working with and being trained by people who were very skilled, knowledgeable, friendly, supportive and professional and person-centred ... and kept me 'in the picture' at all times" (KILPATRICK et al., 2007, p.30). As the researcher's confidence and research skills grew, he became a de facto peer researcher team leader, motivating and organizing a small team based in a local area. He arranged weekly times to meet over a cup of coffee and discuss fieldwork with his fellow peer researchers, discussed problems and provided practical assistance to the team including arranging interview rooms and transport. This role was negotiated and appointed on a peer group level and if imposed by the adult researchers may not have been as successful. The peer researcher and his colleagues were located around a two-hour journey from the university-based team and his proactive approach helped to maintain interest and commitment over the relatively lengthy life span of the project (two and a half years). [34]

This peer researcher also played an important role at steering group meetings, adeptly explaining problems with attrition and data collection. At the final steering group meeting with the funders of the research, he demanded a meeting with the Minister for Education to discuss the findings, to which they agreed. At the end of the project, this peer researcher reflected on his role. He said: "One of the high points for me was having the opportunity to meet so many different types of people from the 'people in suits', the trainers/facilitators, peer researchers and above all the young people" (KILPATRICK et al., 2007, p.29). [35]

The desire to change things at policy level was also evident in how Jason (name anonymized) responded to the people he interviewed. This challenged the adult research team's protocols and required them to reconsider the peer research relationship. The stories of two particular individuals affected Jason personally and he felt compelled to assist them. After discussion with the adult researcher team, Jason offered sign posting information to both young people, but he also maintained contact with them long after the research ended. Through his role in a youth organization, he was able to manage this in a professional and supported environment but it did reveal a significant change to the standard research relationship. [36]

This was clearly a learning process for the adult research team and demanded trust and rationale to consider the implications for the research but it demonstrates the power shift as peer researchers build self-confidence, earn merit and contribute to the decision-making of the team. [37]

4.2.1 Challenges for the adult research

There are times when compliance with academic integrity conflicts with the operational aspects of participatory research. Loath to contaminate research subjects, sites and data, a common sense approach is often demoted, priority given to maintaining reliability and rigor in the research process. Working with peer researchers can challenge and question this practice and positions the peer researcher as an active agent within the exchange. For example, revised or new approaches to gathering data may be adopted during the research and those undertaking projects with lay researchers have to be mindful of the possibility of this from the start, for example when seeking ethical approval for the research. [38]

Skilled qualitative researchers can extract data but can lack the penetration of someone who belongs and is identified with a particular social group. The small group of peer researchers recruited for the Cross-Community Schemes research wasted no time in bonding, notably demonstrated by mobile ring tones being exchanged during the first coffee break. Lunch was provided on site, but the peer researchers ate quickly and decamped to the park for the rest of the lunch break; a rapport had also been established with the adult researchers but we were politely excluded from their "down time." [39]

Struggle did occur at times, when peer researchers came up with ideas that the research team had negative experiences or felt was unworkable. In Out of the Box, the team of peer researchers wanted to meet the research participants before commencing fieldwork. They thought innovatively about how to engage with hard to reach young people in the sample and one researcher sourced free movie tickets and arranged an initial meeting at the local cinema; unfortunately no-one turned up. Based on previous experience, the adult researchers possibly wouldn't have tried this approach but it was a necessary step in the power exchange, granting some power and decision-making to the peer researchers while subsequently recapturing part of it in order to move on to the next stage of the research. [40]

In contrast, peer researchers demonstrated positive and innovative approaches to data gathering. They very seldom lost heart when trying to contact participants and relied on their informal social networks and local knowledge to track down individuals. For the Cross-Community Schemes research focus groups, Facebook and other social networking sites encouraged participation and mobile phone texting was used extensively in the hours and minutes prior to the arranged meeting times. This privileged access to their peer group helped participation but at times could frustrate the adult researcher. On more than one occasion, the adult research team would arrive to observe a focus group with only one or two individuals; however, a burst of activity on mobile phone or computer generally produced a healthy number of participants. [41]

Reflecting back on the unique role of the peer researcher, a role which at times demands being a confidante, a mentor, a covert and overt intelligence gatherer challenges the adult researcher. Subtle expressions of power—responding to requirements and needs of research participants goes slightly against the grain of the qualitative researcher, fearing that their involvement will influence or direct an individual. The role of the peer researcher has the power to respond without guilt or fear. Whilst academic research may teach one to isolate emotional responses—it is wrong not to respond when researching young people's lives (see DUNCAN, DREW, HODGSON & SAWYER, 2009 for illustration). [42]

There are difficulties then, managing the power exchange but the commitment to providing research with scientific rigor must remain the goal throughout. Participatory research is not necessarily more valid than other forms of research, however it enables the voice of the researched to be adequately represented and in the process the challenges of power differentials are minimized as much as possible. As SMITH et al. (2002) state, "[i]t cannot be taken as self-evident that participatory research is ideologically purer, or inherently better in its conduct and delivery, than research conducted to other methodological conventions" (p.194). [43]

Vulnerabilities and power with others involved also needs analysis. DENTITH et al. (2009) describe research conducted in the UK with young mothers; their findings were seized upon and sensationalized by the national press which risked exposing the identity of the participants. Identity protection is always of paramount importance in research which undertakes to guarantee anonymity and confidentiality but is particularly important when working with peer researchers and their participants because they can be in a position of vulnerability as they expose their lives to scrutiny. In DENTITH's research, however, this misrepresentation and misunderstanding by the newspapers and local media allowed for the development of new skills in practice and dissemination. [44]

5. Being Post-Modern/Conclusion

So, how can we position participatory research with all its benefits and risks attached to it for both lay and academic researchers in the contemporary post-modern society? [45]

Wendy BASTALICH (2009) outlines the three broad positions of post-modern theory for social research methodology: 1. situational co-construction of interview data between researcher and participant; 2. research interview emphasizes the social and cultural lenses that determine the stories that interviews produce and; 3. produces local, specific subject knowledge failing to reflect on deeper, more enduring social structures and relations. Involving young people as researchers is post-modern; by constructing knowledge through a tripartite exchange which challenges and reinterprets the power status between adults/professionals and young people/research subjects; creating the potential for the active role of the researcher to be redefined. [46]

Debate within the realm of children and young people's participation in research calls for a new approach, ranging from a continuum (PUNCH, 2002), developing a new paradigm embracing the inherent differences of children's research with no less rigor than adult's (KELLETT, 2005), or demanding a new model of intergenerational research (DENTITH et al., 2009). Regardless of the appropriateness of the model, it is necessary to acknowledge the differences of working with young people in research. It arguably is a more emotionally risky terrain to negotiate and requires equal rigor to that of quality adult–led and delivered research. It does however demand flexibility and the potential to exchange power either temporarily or permanently. This needs to be both constructed and carried out in an artificial and self-conscious way, a post-modern approach, which acknowledges the fluctuating levels of power among the research partners. We have made an attempt to develop a model that visualizes the actors influencing the power relations in a participatory research project (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Model of power relations in participatory research [47]

As FLICKER and colleagues suggest, "participation is not static. As youth develop trust with an organization or facilitator, and in their own skills and abilities, they will most likely demand increased control and participation" (FLICKER et al., 2008, p.298). SCHOSTAK and SCHOSTAK (2008) warn that resistance to these changes should be expected, as they challenge the powerful. The power exchange will continue to ebb and flow but as discussed has the potential to deliver a range of outcomes on an emotional, structural and social level. [48]

We would like to express our sincere thanks to all the young people that we have worked and learned with during the course of the research projects described in this paper:

NCB NI & ARK/YLT: Adrian, Aoife, Caoimhe, Eryn, John, Jonathan, Leah, Nicole, Ruben, Samantha, Ruth and Vanda.

Out of the Box: Aidan, Claire, Clare, Clare, Dee, Jamie-Lee, Jenna, Kevin, Kitty, Michaela, Orla, Rachel, Regina and Sandy.

Cross-Community Schemes: Aaron, Ashleigh, Bróna, Felicity, Laura, Maria and Sinead.

ARK (2009). Young life and times survey, 2008, http://www.ark.ac.uk/ylt/2008/index.html [Accessed: December 20, 2011].

Atkinson, Dorothy (2004). Research and empowerment: Involving people with learning difficulties in oral and life history research. Disability & Society, 19(7), 691-702.

Bastalich, Wendy (2009). Reading Foucault: Genealogy and social science research methodology and ethics. Sociological Research Online, 14(2), http://www.socresonline.org.uk/14/2/3.html [Accessed: March 29, 2011].

Bernstein, Robert (1980). The development of self-esteem during adolescence. Journal of Genetic Psychology, 136, 231-245.

Borland, Moira; Hill, Malcolm; Laybourn, Ann & Stafford, Anne (2001). Improving consultation with children and young people in relevant aspects of policy-making and legislation in Scotland. Edinburgh: Scottish Parliament.

Brownlie, Julie (2009). Researching, not playing, in the public sphere. Sociology, 43(4), 699-716.

Campbell, Carol & Trotter, Joy (2007). Invisible young people: The paradox of participation in research. Vulnerable Children and Youth Studies, 2(1), 32-39.

Cavet, Judith & Sloper, Patricia (2004). The participation of children and young people in decisions about UK service development. Child: Care, Health and Development, 30(6), 613-621.

Clark, Andrew; Holland, Caroline; Katz, Jeanne & Peace, Sheila (2009). Learning to see: Lessons from a participatory observation research project in public spaces. International Journal of Social Research Methodology, 12(4), 345-360.

Coady, Micaela; Galea, Sandro; Blaney, Shannon; Ompad, Danielle; Sisco, Sarah & Vlahov, David (2008). Project VIVA: A multilevel community-based intervention to increase influenza vaccination ratges among hard-to-reach populations in New York City. American Journal of Public Health, 98(7), 1314-1321.

Coles, Jan & Mudaly, Neerosh (2010). Staying safe: Strategies for qualitative child abuse researchers. Child Abuse Review, 19(1), 56-69.

Connolly, Anna (2008). Challenges of generating qualitative data with socially excluded young people. International Journal of Social Research Methodology, 11(3), 201-214.

Coyne, Imelda (2005). Consultation with children in hospital: Children, parents' and nurses' perspectives. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 15(1), 61-71.

Dentith, Audrey; Measor, Lynda & O'Malley, Michael (2009). Stirring dangerous waters: Dilemmas for critical participatory research with young people. Sociology, 43, 158-168.

Dickson-Swift, Virginia; James, Erica; Kippen, Sandra & Liamputtong, Pranee (2009). Researching sensitive topics: Qualitative research as emotion work. Qualitative Research, 9(1), 61-79.

Duncan, Rony; Drew, Sarah; Hodgson, Jan & Sawyer, Susan (2009). Is my mum going to hear this? Methodological and ethical challenges in qualitative health research with young people. Social Science and Medicine, 69, 1691-1699.

England, Kim (2005). Getting personal: Reflexivity, positionality, and feminist research. The Professional Geographer, 46(1), 80-89.

Finch, Janet (1999 [1984]). "It's great to have someone to talk to": The ethics and politics of interviewing women. In Alan Bryman & Robert G. Burgess (Eds.), Qualitative research (Vol. 2., pp.66-80). London: Sage.

Flicker, Sarah; Maley, Oonagh; Ridgley, Andrea; Biscope, Sherry & Lombardo, Charlotte (2008). e-PAR. Using technology and participatory action research to engage youth in health promotion. Action Research, 6(3), 285-303.

Freire, Paulo (1996 [1986]). Pedagogy of the oppressed. Harmondsworth: Penguin.

Gibson-Graham, J.K. (1994). Stuffed if I know!: Reflections on post-modern feminist social research. Gender, Place & Culture, 1(2), 205-224.

Glaser, Barney G. & Strauss, Anselm L. (1968 [1967]). The discovery of grounded theory. Strategies for qualitative research. London: Weidenfeld and Nicolson.

Gillman, Maureen; Swain, John & Heyman, Bob (1997). "Life" history or "case" history: The objectification of people with learning disabilities through the tyranny of professional discourse. Disability and Society, 12(5), 675-693.

Guba, Egon G. & Lincoln, Yvonna S. (1981). Effective evaluation. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

James, Allison & Christensen, Pia (Eds.) (2008). Conducting research with children. London: Falmer Press.

James, Allison & Prout, Alan (1998). Constructing and reconstructing childhood. London: Falmer Press.

Jones, Adele (2000). Exploring young people's experience of immigration controls: The search for an appropriate methodology. In Beth Humphries (Ed.), Research in social care and social welfare (pp.31-47). London: Jessica Kingsley.

Kellett, Mary (2005). Children as active researchers: A new research paradigm for the 21st century? NCRM Methods Review Papers, NCRM/003, http://eprints.ncrm.ac.uk/87/1/MethodsReviewPaperNCRM-003.pdf [Accessed: March 29, 2011].

Kilpatrick, Rosemary; McCartan, Claire & McKeown, Penny (2007). Out of the Box—Alternative education provision in Northern Ireland, Research Report No. 45. Bangor: Department of Education.

Kilpatrick, Rosemary; McCartan, Claire; McAlister, Siobhan & McKeown, Penny (2007). "If I am brutally honest, research has never appealed to me ..." The problems and successes of a peer research project. Educational Action Research, 15(3), 351-369.

Larson, Reed & Richards, Maryse (1994). Divergent realities, the emotional lives of mothers, fathers and adolescents. New York: Basic Books.

Leibenluft, Ellen; McClure, Erin; Nelson, Eric & Pine, Daniel (2005). The social re-orientation of adolescence: A neuroscience perspective on the process and its relation to psychopathology. Psychological Medicine, 35(2), 163-174.

McLaughlin, Hugh (2006). Involving young service users as co-researchers: Possibilities, benefits and costs. British Journal of Social Work, 36(8), 1395-1410.

McLeod, John (1994). Doing counselling research. London: Sage.

NCB NI & ARK/YLT (2010). Attitudes to difference. Young people's attitudes to and experiences of contact with people from different minority ethnic and migrant communities in Northern Ireland. London: National Children's Bureau.

Neill, Sarah (2005). Research with children: A critical review of the guidelines. Journal of Child Health Care, 9(1), 46-58.

OFMDFM (2006). Our children—Our pledge. A ten-year strategy for children and young people in Northern Ireland 2006-2016. Belfast: Office of the First Minister and Deputy First Minister.

Pope, Catherine & Mays, Nick (1995). Qualitative research: Reaching the parts other methods cannot reach: an introduction to qualitative methods in health and health services research. British Medical Journal, 311(6996), 42-45.

Punch, Samantha (2002). Research with children: The same or different from research with adults? Childhood, 9(3), 231-241.

Schostak, John & Schostak, Jill (2008). Radical research: Designing, developing and writing research to make a difference. London: Routledge.

Schubotz, Dirk & McCartan, Claire; with McDaid, Aaron; McIntyre, Bróna; McKee, Felicity; McManus, Maria; O'Kelly, Sinead; Roberts, Ashleigh & Whinnery, Laura (2008). Cross community schemes: Participation, motivation, mandate. Final project report. Belfast: ARK.

Smith, Roger; Monaghan, Maddy & Broad, Bob (2002). Involving young people as co-researchers: Facing up to the methodological issues. Qualitative Social Work, 1(2), 191-207.

Thomas, Nigel (2007). Towards a theory of children's participation. International Journal of Children's Rights, 15, 199-218.

Trotter, Joy & Campbell, Carol (2008). Participation in decision making: Disempowerment, disappointment and different directions. Ethics & Social Welfare, 2(3), 262-275.

Ward, Linda (1997). Funding for change: Translating emancipator disability research from theory to practice. In Colin Barnes & Geoff Mercer (Eds.), Doing disability research (pp.32-49). Leeds: The Disability Press.

Weber, Max (1968 [1922]). Economy and society: An outline of interpretive sociology. New York: Bedminster Press.

Wiles, Rose; Charles, Vikki; Crow, Graham & Heath, Sue (2006). Researching researchers: Lessons for research ethics. Qualitative Research, 6(3), 283-299.

Wright, David; Corner, Jessica; Hopkinson, Jane & Foster, Claire (2006). Listening to the views of people affected by cancer about cancer research: An example of participatory research in setting the cancer research agenda. Health Expectations, 9(1), 3-12.

Claire McCARTAN is Research Assistant at the Institute of Child Care Research at Queen's University.

Contact:

Claire McCartan

Institute of Child Care Research

Queen's University Belfast

6 College Park, Belfast BT7 1LP

Northern Ireland

Tel.: +44 28 9097 5296

Fax: +44 28 9097 3943

E-mail: c.j.mccartan@qub.ac.uk

URL: http://www.qub.ac.uk/research-centres/YDS/BYDSMeettheTeam/

Dr Dirk SCHUBOTZ is Director of Young Life and Times at ARK, a joint initiative between Queen's University and the University of Ulster.

Contact:

Dr Dirk Schubotz

ARK, School of Sociology, Social Policy & Social Work

Queen's University Belfast

Belfast BT7 1NN

Northern Ireland

Tel.: +44 28 9097 3947

Fax: +44 28 9097 3943

E-mail: d.schubotz@qub.ac.uk

URL: http://www.ark.ac.uk

Jonathan Murphy is a peer researcher, he recently completed his "A" Level examinations, and started university in autumn 2010. He has been involved in a number of peer research studies with ARK and the National Children's Bureau NI.

Contact:

Jonathan Murphy

c/o Dr Dirk Schubotz

ARK, School of Sociology, Social Policy & Social Work

Queen’s University Belfast

Belfast BT7 1NN

Northern Ireland

E-mail: jmurphy53@qub.ac.uk

McCartan, Claire; Schubotz, Dirk & Murphy, Jonathan (2012). The Self-Conscious Researcher—Post-Modern Perspectives of Participatory

Research with Young People [48 paragraphs]. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung / Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 13(1), Art. 9,

http://nbn-resolving.de/urn:nbn:de:0114-fqs120192.