Volume 14, No. 1, Art. 17 – January 2013

Music as an Interpretive Lens: Patients' Experiences of Discharge Following Open-heart Surgery

Linda Liu, Jennifer L. Lapum, Suzanne Fredericks,

Terrence Yau & Vaska Micevski

Abstract: In this article, we highlight the use of music as an interpretive lens to understand patients' experiences of discharge following open-heart surgery. We adopted an arts-informed narrative methodology and interviewed participants at 1 and 4-6 weeks following discharge. Our secondary analysis followed an aesthetic approach that involved application of musical principles including rhythm, timing, and tone to frame our interpretation. We found that the tensions, harmony and relational dynamics between patients and practitioners were best elucidated when viewed through the lens of a solo concerto; this is orchestral work that features a soloist. Our findings have an impact on the discourse of patient-centered care and the need to re-orient communication measures so that practitioners can access the internalized space of patients' mind and body. Since music as an interpretive lens is embryonic in its development, its use has expansive implications for fostering aesthetic knowing in research and health care.

Key words: arts-informed research; music; narrative research; discharge planning; heart health; secondary analysis

Table of Contents

1. Introduction

2. Background

3. Methodology

4. Theoretical Framing of Analysis: Music as an Interpretive Lens

5. The Patient Concerto: Study Results

5.1 Setting the stage for discharge: Preoperative preparation

5.2 First exposition: Orchestra themes introduced

5.3 The second exposition: Patients' themes introduced

5.4 Development: Moments of tension

5.5 Recapitulation: Moments of support and affirmation

5.6 The unrealized cadenza

6. Discussion

7. Limitations and Future Research

8. Conclusion

The nature of music is its potential to carry one deep into human experience and transport listeners to a different time in their lives. People can often recall a song that captured them. For some, the song "Born This Way" by Lady Gaga provides positive identity affirmation. Whereas others are drawn into a range of emotions with Leonard COHEN's song "Hallelujah" or into a dark period in life with the song "Brick" by Ben Folds Five, which recounts a personal experience of abortion: "She's a brick and I'm drowning slowly." One might be drawn into a joyful state with BEETHOVEN's "Ode to Joy" or the classic song "Dancing Queen." Alternatively, one might be drawn into humanitarianism with K'NAAN's "Wavin Flag" or find oneself uplifted by the BEATLES song "Let it Be" with lyrics such as "when I find myself in times of trouble, Mother Mary comes to me, speaking words of wisdom, let it be." Whatever the song, music's ability to carry someone deep into an experience through the aesthetics of sound is powerful. [1]

For us, the powerful nature of music unintentionally emerged in the related study about patients' narratives of discharge in the context of open-heart surgery. Towards the end of our analysis (which involved narrative mapping), we visually mapped one individual's story on top of a a musical staff. We began to imagine the forms of music that best fit participants' stories; this prompted us to understand patients' stories in a unique way, which inspired another layer of analysis. In this article, we provide insight into a secondary analysis conducted from an arts-informed narrative approach using music as an interpretive lens. [2]

Heart surgery is a common intervention for cardiovascular disease that interrupts the rhythm of patients' lives. Despite its advantage, heart surgery can result in significant changes in physical, psychological and social functioning that can last six weeks post-discharge and even longer. These changes include fluid retention, heart rate and rhythm fluctuations, and the presence of symptoms such as nervousness, fatigue and pain (FREDERICKS, SIDANI & SHUGURENSKY, 2008). Being discharged and returning home is an unfamiliar experience filled with paradoxical feelings of relief and apprehension. Alongside of this, patients are expected to become self-sufficient in their recovery and adhere to discharge instructions (LAPUM, ANGUS, WATT-WATSON & PETER, 2011). [3]

An individual's recovery is influenced by discharge preparation received in hospital. Yet, discharge programs are not always comprehensive and conducive to patients' needs. Although evidence indicates that programs should address physical, psychological and social functioning in order to be effective (ELLIOT, LAZARUS & LEEDER, 2006; GARDNER, ELLIOT, GILL, GRIFFIN & CRAWFORD, 2005), this has not always been the case (ELLIOT et al., 2006). The majority of programs tend to focus on the physical functioning of individuals. Researchers have found that individuals report numerous psychological symptoms such as anxiety, depression, and stress (DOERING, CROSS, MAGSARILI, HOWITT & COWAN, 2007; ELLIOT et al., 2006; LaPIER & WILSON, 2007; SCHELLING et al., 2003; STOLL et al., 2000). Presence of these symptoms may reduce adherence to discharge instructions. Studies have reported that timing and dose of discharge teaching is critical and needs to be individualized so that content is tailored to patients' needs (FREDERICKS, GURUGE, SIDANI & WAN, 2010; FREDERICKS et al., 2008; GARDNER et al., 2005; LEEGAARD, NADEN & FAGERMOEN, 2008). Furthermore, technologized environments annexed with standardized routines can be problematic because they are often fast-paced and can limit patient contact (LAPUM, CHURCH, YAU, MATTHEWS DAVID & RUTTONSHA, 2012). [4]

Taking into consideration the momentous experience of discharge, we were interested in examining patients' transition to home. The purpose of our research was to explore the facilitators and barriers of an effective discharge. Because of the organic way that music entered the analysis, we advanced our narrative methodology by situating it within the arts; we detail this process next. [5]

In the primary study, a narrative methodology was employed, which entailed thinking with and attending to stories (FRANK, 2002). People often recount their experiences through stories because they have learned this practice of communication early in life (LAPUM, 2009) making storytelling a familiar way to interact. The tenets of contextuality and temporality (CONLE, 1999; CZARNIAWSKA, 2002; EMDEN, 1998) were used, which involved attention to the influences of context and time in storytelling. Since stories are told from particular vantage points (CONLE, 1999; FRANK, 2000), it was important to consider shaping forces, voices, and components of stories (e.g. characters, situations, and outcomes) (LIEBLICH, TUVAL-MASHIACH & ZILBER, 1998; LIEBLICH, ZILBER & TUVAL-MASHIACH, 2008). [6]

A convenience sample of ten individuals was recruited from a preoperative clinic at a large, urban hospital. The sample included five men and five women that underwent open-heart surgery including coronary artery bypass graft and/or valve repair or replacement. Participants were 37 to 80 years of age. Semi-structured interviews were audio-recorded and conducted in participants' homes at 1 week and 4-6 weeks following discharge. A selection of questions included: Tell me about being prepared for discharge? Tell me about going home? If you could change something about the discharge process, what would it be? Interviews lasted 30 to 90 minutes. Detailed fieldnotes were completed documenting researchers' observations of the context and non-verbal language. This study received ethics approval from the university and hospital institution involved. [7]

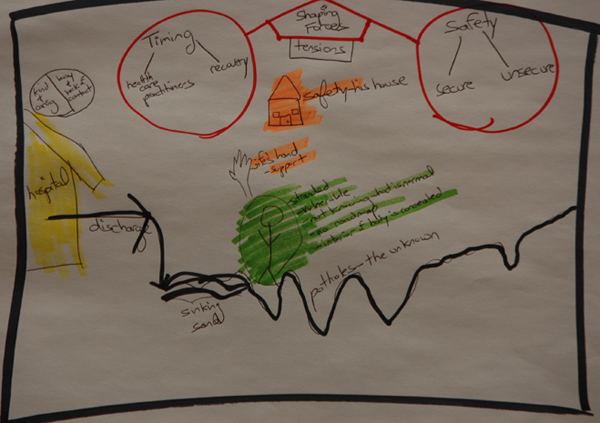

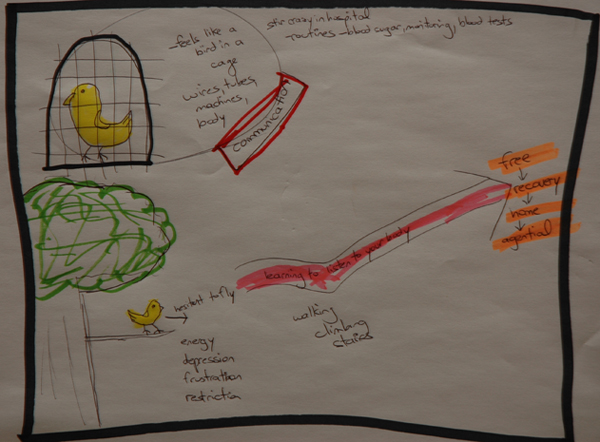

In addition to story content, a focus was placed on narrative form, how stories are put together and what structures participants draw upon to tell their stories (LIEBLICH et al., 1998). This type of analysis highlights contextual elements of stories and the dominant discourses that influence story construction. A key analytic tool was the use of narrative mapping which assisted researchers to highlight patterns and components of stories (LAPUM, 2009). For each interview, this involved constructing a visual map of the participant's story on an 8½ x 11 inch piece of paper (LAPUM et al., 2011). See Illustration 1 and 2 for examples of these narrative maps.

Illustration 1: The road to recovery

Illustration 2: Like a bird in a cage [8]

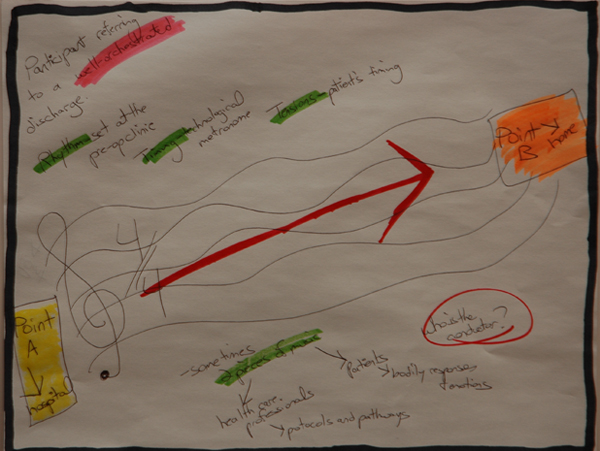

Towards the end of our primary narrative analysis, we began to map one participant's story on a musical score. A music score is a written form of musical notations and symbols (see Illustration 3 for this narrative map). The idea of a musical score emerged as a result of a participant describing discharge preparation as an "orchestrated process" in that the health care team was organized and that each event was clearly mapped out and timed accordingly. The incorporation of music at this stage of the analysis was unexpected and also prompted us to engage in analytic discussions about the other participants' stories. Layered discussions of the musical components documented on this score became the departure point for a secondary analysis of participants' narratives. We labeled this as a secondary analysis since we were already recognizing its expansive possibilities and knew that music as a novel approach would involve a significant amount of time exploring and delineating it as we engaged in a re-analysis of all of the data from this perspective. The core analytic team involved the first and second author. The rest of the authors were engaged in analytic discussions throughout the process.

Illustration 3: The orchestrated process [9]

4. Theoretical Framing of Analysis: Music as an Interpretive Lens

In the advent of a secondary analysis, we situated the narrative methodology within a theoretical framing that was informed by the arts. Arts-informed research engages the creative nature of arts (COLE & KNOWLES, 2001) and can draw attention to the complexities of human illness (STATE OF THE FIELD COMMITTEE, 2009). The arts is a way of inquiry (McNIFF, 2008) that is aesthetically-focused (BRESLER, 2006; McNIFF, 2008). In order to implement aesthetic knowing, we drew upon BRESLER's (2006) work to cultivate our senses so that we could re-see the world through the patient's lens; this involved sensitizing ourselves to the aesthetic components of participants' stories. Sense-oriented questions guided us such as: What are the emotional and physical sensations of being discharged? What do patients feel, hear and see? As per the primary study, we maintained a focus on stories in which the narrative analysis remained linguistically-oriented as well as focused on the form of stories. [10]

Since this was a secondary analysis, we employed our interpretive lens to act as a theoretical filter that provided a deep focus on understanding patients' stories from the standpoint of music. An interpretive lens provides a perspective that shapes the research process (CRESWELL, 2007). Music as an interpretive lens followed an organic and creative process in which the procedures were not laid out in advance, but emerged through iterative and dialogical engagement with participants' stories and discussions among the research team. [11]

Employing music as an interpretive lens in qualitative research has not been ventured before. In a recently published scoping review of arts-informed methods, music was not identified as an art genre/design in the current literature (BOYDELL, GLADSTONE, VOLPE, ALLEMANG & STASIULIS, 2012). Subsequently, it was important to remain open and creative as we engaged in an organic process as well as transparent in our interpretive decisions. We drew upon EISNER (2008) who emphasizes the importance for arts-based researchers to be multilingual in the arts as well as in the research data. The idea of multilingual required us to be simultaneously immersed in the data and the music. Thus, we sought to gain intimacy with principles of music theory and engaged in constant reflection of these concepts while dwelling in the data. [12]

The first author guided the process by drawing upon her expertise as a music teacher and pianist. The foundational elements of music including melody, rhythm, tempo, tone, harmony, expression and texture are the building blocks to music composition, performance, and listening. Aside from understanding these elements on a rational level, we engaged in music listening exercises to further cultivate our aesthetic knowing. By maintaining an organic process, music listening took many different forms. We allowed our senses to be guided by participants' stories by inquiring how their narratives could be described aurally. We considered and searched for music that evocatively described participants' narratives. We listened to music overlaid with participants' audio-files, and we listened to music while reading transcripts. Detailed fieldnotes were recorded to document our sensations of music listening while remaining engaged in participant data. Often, we discussed the following questions when reading transcripts and listening to music: What do you hear? What do you feel? What do you see? How does the music and patients' stories harmonize or clash? These questions maintained aesthetic attunement. [13]

We became further attuned to the aesthetic by engaging our senses in a number of ways. One particular way included attending a symphony as a means to engage in both music listening and the embodied performance. The aesthetics of live performances were documented in reflective fieldnotes. We also took a naturalized approach by taking walks outdoors during analysis. While dialoguing about the sights and sounds around us, we allowed our senses to guide and inspire conversations about participants' narratives. To highlight one example, while the first two authors stood in approximately the same space with eyes closed, their attention was drawn to different sounds. One author was attuned to the chirping birds in a tree almost immediately above her head while the other author was drawn to the disruptive sounds of a truck at a fair distance away. This analytic technique was particularly useful in highlighting the interpretive nature of both the aesthetics of sound and patients' experiences of discharge. [14]

5. The Patient Concerto: Study Results

Results are presented based on a solo concerto, which is orchestral work featuring a solo instrument; this form of music best elucidated tensions, harmony and relational dynamics in stories, and allowed us to understand the shaping forces and transitions of narratives. The concerto form has evolved in structure. The Classical era concerto emerged in the 18th century contains more structured patterns than later forms; it was this form that permitted deep insight into patients' narratives. During the analysis, we considered the different roles in the concerto and how this relates to discharge in the context of surgery. We likened the soloist to the patient in which he/she is featured in the concerto. The concerto also consists of the orchestra members. In this study, the orchestra is analogous to the various formal and informal caregivers. Like the orchestra, caregivers operated to highlight, complement and contrast the soloist. In a concerto, the conductor is involved in keeping the rhythm and ensuring that orchestral players are introduced at the right time. He/she can only listen for the soloist to complete his/her passage and cue other ensemble parts. The conductor role appeared as fluid in this study and was sometimes played by specific health care members, the family, and at times, the patient played both the conductor and soloist role. [15]

The soloist is the driving force and focal point of a concerto; likewise, in the context of patient-centered care, the patient should be the focus of care. Yet, what emerged from the data was that so often the orchestral parts are focused on complying with rhythms predetermined by clinical protocols and pathways that patients' own experiences are rendered less important. Music as an interpretive lens has assisted us to better understand the components of discharge and the tensions and harmonies that exist. Results are presented in six sections according to the phases of a solo concerto: 1. setting the stage; 2. first exposition; 3. second exposition; 4. development; 5. recapitulation; and 6. unrealized cadenza. Throughout this article, pseudonyms are used and the soloist is referred to as "she." [16]

5.1 Setting the stage for discharge: Preoperative preparation

Conceptualizing the preoperative phase analogous to an orchestral performance permits insight into the preparatory steps that patients undergo prior to surgery and their eventual discharge. Like the music score that players study prior to performance, patients are introduced to pathways. They are provided general timelines about recovery and milestones that have to be met in order for discharge. They are introduced to the players and their respective roles as well as patients' own role. As one participant stated: "It gave me insight into what was going to happen" (Doris). Participants reported the positive benefits of the preoperative clinic indicating that it not only set the expectations, but was "the foundation of all of it" (Mike). Patients were provided an awareness of what they will encounter and how to progress to discharge just as a music score lays out the instruments, range of notes to be played, and the pace of performance. While the orchestra is usually composed of resident players who have worked with each other, it is common that the soloist would be a visiting artist. The rehearsal provides the opportunity for the soloist to get to know the orchestral cast. In a similar manner, the patient is entering into an unfamiliar environment and the clinic provides a space to become familiar with the cast of players. [17]

In music, the conductor ensures that every player is moving in a coordinated fashion. While the role is designated to one individual during a performance, in our research this role appeared fluid. Participants' stories of the preoperative clinic revealed that the conductor was the nurse who organized patients' itinerary, which initiated the path to discharge. One participant indicated the nurse was efficient and effective in facilitating this process: "[it was] so well orchestrated. I've rarely seen somebody who is a combination of a drill sergeant and a very caring person" (Mike). The linguistic use of "orchestration" highlights the thorough and intricate planning similar to the arrangement of a piece of music. Without the caring presence and meticulous facilitation of practitioners, patients' flow through the process might not be smooth. Likewise, without rehearsal, the song may not be played with ease and aesthetic appeal. [18]

The manner in which tones are produced have the power to evoke different qualities of sound. As the movement and pace of the preoperative clinic itself presents a glimpse of how patients' surgery experience would play out, participants marveled at practitioners' competence. This competence instilled a tone of confidence that surgery would proceed in the same way and trust with practitioners: "[It] was very thorough. I was shocked how organized they were. They had everything ready, everybody lined up. You saw these people, so I felt good ... I didn't feel as scared" (Lisa). In addition, the patient's role in the process was highlighted. In the solo concerto, the soloist is the distinguishing feature of the performance and has proficiency to give a stellar performance. In heart surgery however, the patient is not a regular member of the health care team and often has never played the sick role. One participant indicated that the tone was set at the clinic about what to expect by initiating a particular "mindset":

"the expectation is set at the front, which is good, it was always on your mind. That was one of the ones that triggered on me. ... it helps your mindset ... in understanding why they're doing some of the things they're doing, so that you can lead up to discharge." (Mike) [19]

In order for patients to reach discharge successfully, adequate information must be given so that patients can acclimatize and actively contribute to their healing process. [20]

As in an orchestral performance, the timing of patient education is critical. Participants found that information provided preoperatively was helpful: "I thought that a lot of information I needed for discharge I got during the preadmission session as opposed to actually when I was in the hospital" (Stan). Information provided during this clinic helped individuals to make sense of their postoperative experience and prepare themselves for discharge while they were in a clear state of mind. Some participants indicated that there was also a wealth of information provided following surgery. They often felt that information, such as the discharge booklet, could have been provided earlier: "[It] would have been helpful for me to get a [discharge booklet], pre-op ... then I would have known. I don't know, then I could have asked the doctor questions in the hospital" (Abigail). The preoperative clinic also created a safe space for patients to address any personal fears. One participant recalls discussing his concerns with the psychiatrist: "I confided that I did have some anxieties, based upon previous surgeries and anesthesia. She was helpful, particularly with the question of delirium and that was where my anxiety was. She put a lot of that anxiety to rest" (Stan). The timing of these connections with practitioners was important so that patients had the opportunity to make sense of and absorb the information while in the best state of mind. [21]

5.2 First exposition: Orchestra themes introduced

The solo concerto commences with the exposition, which is the introduction of orchestra themes that are reoccurring musical ideas based on combinations of rhythm, melody, and harmony. The soloist plays a silent role during this period as the orchestra progresses through different themes. Considering an exposition in the context of heart surgery, in the immediate postoperative phase practitioners were the dominant players. Like playing through a well-rehearsed score, they meticulously assessed, monitored, and adhered to clinical pathways and protocols in order to move patients towards discharge. Participants recalled being strapped to a multitude of machines as nurses ensured that vital signs, body weight, bloodwork, drainage volumes and input/output values were progressing towards normal limits. One of the participants stated "every whisper of breath, every micro temperature change, everything" (Stan) was measured. Like the solo concerto, as the first exposition is nearing a close, patients are regaining agency and ready to enact their role. One participant noted that he was able to sense that he was getting better because the technology was being removed:

"The first thing, was taking off the urine bag, next was the intravenous. I had a heart monitor which is remote control. You can see it from the desk which I thought was fantastic. Then they came and said 'okay, we're disconnecting you.' One by one everything disappeared, that was the last one, the heart monitor. Then I felt wow! ... that's it—free." (Bob) [22]

Being liberated from devices was a significant indicator of hemodynamic stability and that the patient was progressing in recovery and near ready for discharge. [23]

Practitioners were also delivering information in a variety of modalities during the postoperative phase. Don recalled that he was given a discharge booklet and had the opportunity to attend classes to learn more about medications, physical recovery and the transition home:

"They made me aware of the standard information. I guess there are a couple of seminars in the last day or two, just in terms of what to expect ... I guess just part of the standard process; there was information available, whether it was attending the seminar in the ward or printed material ... just kind of reinforced some of the expectations to have when you go home like in terms of getting out and walking, it's going to take a while before you can drive again." (Don) [24]

Information provided postoperatively begins to bring the home into focus for patients to prepare for this transition. As Don indicated, he found the preparation "helpful." However, the repetition of his word choice "standard information" and "standard process" suggests that the content may not have been individualized and possibly not optimal. Outside of classes, participants also recalled having this discharge information reinforced by practitioners:

"The nurse who was on that day said, 'I don't want to see you back here. Don't lift things.' So there was a bit of don't lift things over 10 pounds, take it slow, you're going to feel tired; so they did a real quick Coles Notes of what the discharge video does." (Mike) [25]

Participants' narratives reflected how they were continually being prepared to take an active role. Like the concerto, practitioners will soon move into the background and become supporting players. [26]

5.3 The second exposition: Patients' themes introduced

As bodily markers indicate a positive progression towards stabilization, patients are poised to actively participate in working towards discharge. During the second exposition of a concerto, the soloist begins to play and the orchestra recedes to quietly accompany and support her part. Like the soloist in a concerto, some participants recalled actively participating in the process towards discharge and figuring out what needs to be done in order for them to go home:

"I said to Dr. L, 'you tell me what I have to do and I'll do it so I can go home tomorrow' [Laugh]. He told me what was required. So, he'd come in the morning of discharge and I said 'I did it plus a little bit more.' " (Joanne) [27]

This quote is reflective of the participant enacting her agency and adhering to the criteria for discharge. She pushed her body so that it would meet the physical indicators for discharge. Joanne also sought the assistance of a resourceful nurse: "ask any questions, she'd go find out and come back and tell me. I just found her very helpful." Participants recalled having to demonstrate a certain level of functional ability before they could be discharged and often referred back to the preoperative information: "It followed more or less the same manual of, 'you've got these things to narrow down before you get discharged.' So, [the nurse] said 'your weight, you've got to have a shower, you've got to dress yourself, you've got to be able to walk' " (Mike). Although practitioners make the final decision for discharge, Mike realized that he had to fulfill his part and comply with the score of pathways before he would be able to go home. [28]

For a number of participants, they were not ready to take on the soloist role as one would in a concerto. Several participants could not recall details about the hospital stay and how that shaped their discharge preparation. Patients can struggle with reduced cognitive capacity due to side effects of extended times on bypass, anesthetic and pain medications coupled with poor sleep and anxiety. Despite attending classes and having home care support to help with recovery, Abigail reported difficulty with absorption of information as it related to using a glucometer: "I was listening when she went over but it wasn't sinking in, because you know, how do you evaluate? Because I was taking it quite seriously but I was so tired." Aside from reduced cognitive capacity, grogginess and fatigue left many participants in a weakened state:

"In my mind, 'why am I failing?' I'm always in bed, I'm tired and I reacted to all of the pain killers, so if I took a pain killer, I'm in bed, I'm nauseated and I want to sleep. That's why I kept saying to them I don't need any of those. I'm fine. I have discomfort but I can deal with it, because I wanted to get out as soon as I can, but how can I recover when I'm in bed?" (Lisa) [29]

Reduced mobility left some participants in a vulnerable state wondering if they would be able to make the transition home. As a soloist would be expected to adhere to a music score, grogginess prevented participants from fulfilling their role and meeting pathways. One participant had little memory and recalled her transfer to a rehabilitation facility as "blank" and "hazy":

"I can vaguely remember them asking me if I had someone to transport me, and I did not. They finally sent me by ambulance ... They tell me ahead of time, and I was a little bit anxious about, you know, leaving, and, you know, 'am I ready?' " (Celine) [30]

Even though she was hemodynamically stable, she was unable to recognize the physical indicators of recovery. Although the first exposition appeared in participants' stories as relatively predictable themes (e.g., progression according to clinical pathways with practitioners as the dominant voices), the second exposition featured soloist themes as more varied and multidimensional. While some participants were able to absorb and apply the information given to them, some were less able to do so. [31]

5.4 Development: Moments of tension

In the solo concerto, the development presents an intermingling of orchestra and soloist themes. The varied themes begin to clash with the orchestra themes and create mounting tensions. The themes go through modifications and transformations of tone, rhythm and harmony, which usually lead to a heightened climax filled with tension. Similarly revealed in participants' stories, tension-filled moments occurred between the soloist (i.e., the patient) and the supporting orchestra cast (i.e., caregivers). [32]

While practitioners monitored individuals very closely, tensions were apparent in participants' accounts. Lisa recalled how contact was limited because of the perceived busyness of the unit:

"I felt more like a specimen. They bring in the stuff, they put it in you, they take it out. There's no explanation and if you do ask for it, they don't have time to thoroughly explain because they have to go to another patient. It would have been nice to know what they were looking for, and I don't know, and sometimes I'm, I was concerned about asking too many questions." (Lisa) [33]

As reflected in Lisa's narrative, patient-centered communication and authentic presence was sometimes neglected due to practitioners' preoccupation with clinical tasks. Their reduced presence discouraged Lisa from actively participating and searching for further informational support. In the case of Celine who was transferred to rehabilitative care and was on home oxygen prior to surgery, she recalled the detached presence as frustrating:

"The staff played dumb. They don't know how to do it 'you do it.' This changing my oxygen, figuring anything out, 'you do it. I don't know how to do it.' They just threw you into. ... maybe that's the way people learn how to get back into the natural life is doing things for yourself." (Celine) [34]

Her linguistic usage of "threw you into …" can be likened to the dissonance heard as orchestral and soloist themes clash and the rising tension. Even though most participants recognized that practitioners carried heavy workloads, rationalizing this did not remove their struggles and need for support. [35]

Transition from hospital to home can be a frightening experience for patients. There is a shift in the supporting cast in which the dominant players that provided monitoring and the associated technology are no longer present. As in a concerto, the soloist's role becomes prominent. Although the orchestra is still present, the nuanced way they play is different. The cast is now replaced by family, friends, and rehabilitation staff for some. These new cast members are unfamiliar with the patient's condition and do not necessarily have the expertise to detect abnormal changes leaving feelings of intense insecurity:

"If something nasty happened, how will things unfold? I suppose being there in the hospital with all the machinery and equipment and the bells and whistles, you have the feeling that even if catastrophe occurred, someone would catch you. If I now leave this cocoon, this nest, who is going to catch me? ... There is a very basic core of fear that something is going to go wrong. You almost feel it's like a ticking bomb and that something is going to explode. ... When you leave the hospital, you're on your own, so the only way I've managed to rationalize it is that another step has to be taken and that there is now even less chance of anything going wrong, but a little voice in the back says 'yeah, but it can go wrong,' and then what?" (Stan) [36]

The intense fear in Stan's excerpt was common among many participants' narratives. As one transitions towards home, the expectations to take on the soloist role can be overwhelming. The shift in the supporting cast in which practitioners are no longer physically present was daunting. [37]

In a solo concerto, "call and answer" phrases are often employed; this is when one voice expresses a music idea that resembles a call or question, while the second voice responds with an answer. At home following surgery, there is often no one to answer. Patients' contact with practitioners is limited in which they see their various doctors at one, four and six weeks. Participants' stories indicated day-to-day struggles and unanswered questions often related to unfamiliar bodily sensations and physical limitations:

"I would have asked them how long is this going to last in terms of physical, how many more days before I can sleep on my side? How long is it going to be before I can raise a glass of water without discomfort? How many more days I'll be so weak that I don't really want to leave the house? There is kind of threatening in my mind to go outside. This is a safe territory." (Len) [38]

There is a sense of insecurity in Len's story that limited his activities and impeded spatial movement beyond the house. It appeared that mere information and/or contact with someone who could have answered these questions may have alleviated his fears and potentially allowed him to move forth. In addition, mismatched expectations regarding recovery generated frustration. Lisa recalled: "Just because I had the plan in my head that, in two days, three days, I go home, I'll be fine, I'll feel great, but that's not the case." She had expected that recovery would be swift. However, Lisa was disappointed to find her expected timeline was drastically different from her physical reality. Even though an array of discharge information was provided, participants still reported inadequate information and support about specific markers that would guide their recovery and indicate success. [39]

5.5 Recapitulation: Moments of support and affirmation

As themes are elaborated and the music reaches a climax in the concerto, tension is released through the recapitulation; this is when the orchestra and soloist highlight their respective themes again. The recapitulation can be considered a restatement of original themes and serves as a unifying feature that precedes the grand conclusion. In a similar fashion, the transition home was a momentous event for participants, but it also carried undertones of conflict and frustration. The home was narrated as a space where participants were expected to take a leading role in recovery. The main components of the recapitulation appear in participants' stories as the voice of practitioners and the rise of familial support. [40]

As participants continued to strengthen their bodies to reach normalization, the voices of practitioners were still heard and they continued to play a role in shaping recovery. One participant recalled "hear[ing] them still in my head saying 'you got to push, your body's good, you should be working at this pace' so now it's helping" (Lisa). As in the recapitulation where themes are being re-introduced, it appeared in participants' stories that the teachings of practitioners continued to play out in the home. Although practitioners were no longer physically present, they continued to be an active voice and contributed to recovery. Stan found himself referring back to his hospital stay to evaluate his situation: "I'm doing what they recommended and things are going well, so it's got to be the right way and as far as I can see, everything is progressing. So I feel quite confident." By looking back to his early stage of recovery, Stan felt completely supported by his health care team, and this support imparted a sense of confidence in his ability to work towards recovery at home. In addition to applying information provided by practitioners, participants also recalled the emotional support: "Everybody is kind and caring. It's really a good process. Generally, attitude of all the personnel is just so commendable. It makes you feel, like we're going to get better." (Len). Len's use of third person pronoun "we're going to get better" suggests that the patient and health care team are in it together. The care and education provided by practitioners extended into the home and fostered patients' capacity to strive towards recovery. [41]

While the health care team transitions into the background during the home period, familial support begins to rise as dominant voices. Participants described how family and friends were often positive forces. Bob was comforted that he was going home with his wife: "I'm lucky that I had someone to come home to who cared about me. Some people don't have that. So I think that made it easier. If I had to come home to an empty place [voice trails off]." The trailing off of Bob's voice is indicative of the vulnerability associated with leaving the hospital. There is the sense that he was not ready to be the dominant voice in his recovery, like a soloist would be in a concerto. Having a loved one at home eased the transition and insecurity of leaving a hospital full of practitioners and technological monitoring. Receiving familial support helped participants to feel safe and less frustrated when performing activities: "The brain is saying 'push, push' but everything else is saying 'no you've got to calm down' ... thank goodness I do have support to say 'you got to sit, you can't do that, you can't lift' " (Lisa). While having someone at home helped participants to gain perspective, even having daily contact with people instilled hope and positive thinking. Joanne, who lived alone, was grateful that she was able to have her surgery in the summer so that she was able to sit outside on her porch and engage in conversations with passersby: "I never had any of these depressed days. But I spent a lot of time on the porch ... people are walking by, they stop and talk or they drive by and stop and talk. It gives you a big lift" (Joanne). Joanne's reflection indicates that engagement with people is important. The presence of a supportive network in the home builds a sense of community and can contribute to a positive outlook for patients. Likewise, the beauty found in the concerto form lies in the dynamic interactions and contrasts between the soloist and orchestra, and their ability to create a cacophony of tones or a unifying soaring melody. [42]

Towards the end of the concerto movement, a cadenza appears where the soloist interrupts the orchestra and launches into an improvised passage. As the orchestra falls silent, the soloist elaborates on a particular theme while displaying her virtuosity and stellar playing abilities. As she launches into the cadenza, the soloist is fully prepared to captivate the audience and becomes the focal point of the performance. In participants' stories, the cadenza appeared as yet unrealized. [43]

In this study, the cadenza appeared as the time at home where participants were expected to reach virtuosic capacity to lead their own recovery and be less dependent. However, at four to six weeks following discharge, participants indicated that they had not gained full mastery over their bodies. As one participant was reminded, "they [the surgical team] broke you" (Lisa). In referring to the literal cracking open of the sternum and moving the rib cage apart, Lisa realized the physical extent of surgery. The linguistic usage of "broke" suggests a body that is fragmented likened to the shattering of a porcelain figurine. While soloists have built up their bodies to attain proficiency in performance, patients have their bodies broken in order to achieve better health. As such, proficiency in recovery is challenging. [44]

As individuals strove towards recovery, they began to learn to gain mastery over their bodies. However, they did not feel confident enough to function independently and play the soloist part. Participants revealed that they continued to lean upon a supporting cast, and sought support through people or information. Len recalled the vulnerability he experienced when venturing beyond the home:

"I was holding my wife's hand but it's, it's as much physical as mental ... You're not feeling secure, you're not feeling safe, venturing outside of the house alone because you don't know whether you're going to have a dizzy spell or whatnot." (Len) [45]

It surprised Len that this insecurity continued to invade his thoughts at four weeks following discharge. Similarly, Bob found himself in a lonely struggle with his body. Despite the joy of returning home with the presence of family and friends and all the information he obtained about recovery, the act of waiting for his body to get stronger still hit him hard at four weeks following discharge:

"I started to get depressed. I mean, nobody could have helped me. A friend of mine kept saying, 'Soon you'll feel great.' I said, 'I know, I know.' I think it's because I felt like I was [in] jail; I couldn't get out. I couldn't drive. Anyway, I just felt sort of frustrated. But you know what? It came and went, and I didn't fall into such a deep depression." (Bob) [46]

Even though he felt supported by practitioners and family, it was a personal struggle for Bob to learn how to "listen to your body" and remain patient as the body eventually regained normalcy. While the virtuosic soloist may have trained her whole life to achieve the extraordinary skill to descend upon the stage and dazzle the audience, patients do not in a similar fashion train extensively to master the recovery process; it is something that they figure out along the way. [47]

At four to six weeks following discharge, participants were not ready to stand on their own unsupported. However, some narratives showed glimpses of hopefulness towards achieving normalcy. By referring to the "transitoryness of life" Stan's narrative highlighted fears of mortality. He recounted that his concerns were starting to fade: "I found myself in this state I think straight after the surgery of feeling very much that it was, you know, that things weren't for sure. I'm over that now and I think I've got a new resilience." Mortality appeared as an underlying sub-text in his narrative (e.g., "transitoryness of life" and "things weren't for sure"). His narrative resolution indicated that there is a resilience of the mind that is important in instilling a sense of confidence to dispel the fears of a failing body. Joanne, who lived alone, also revealed a resilient attitude:

"I never had really down, felt sorry for myself or anything like that. It's just kind of, 'oh this is not going to last.' I'll be able to do this tomorrow or the next day and gradually get back into your routine." (Joanne) [48]

A positive attitude assisted Joanne to resist the frustrations of physical limitations and remain patient in waiting for her body to strengthen. Not only must the virtuosic soloist possess the technical abilities to perform, but she must also have self-confidence in her abilities. As individuals continued to struggle with their bodies following discharge, continual emotional support may play an important role in empowering them to feel self-assured in their journey. [49]

Employing music as an interpretive lens led us to a nuanced understanding of the layers of patients' experiences. Music provided a theoretical filter in which our attention was drawn to the dynamics, harmonies and tensions between patients and their supporting cast. The solo concerto became the form that best facilitated a deep understanding of the narrative components of discharge. The soloist (i.e. the patient) is the central figure in the concerto wherein she is positioned slightly apart from the rest of the orchestra as well as the conductor. As such, attending to the aesthetics of the concerto form generated creative insight into the relationships between patients and caregivers. [50]

As in the development phase of the solo concerto, the transition from hospital to home is often tension-filled. Similar to other studies (LAPUM et al., 2011), we found that individuals were glad to return home, but also described insecurity and a yearning for further support. As practitioners were no longer present to assess and intervene as needed, individuals felt vulnerable at the potential of developing complications. As reported in other work (LIE, BUNCH, SMEBY, ARNESEN & HAMILTON, 2012), although individuals have a discharge booklet, they continued to seek reassurance and advice in determining whether certain physical sensations were normal. In the context of shortened length of hospital stays, individuals are expected to take an active role and engage in self-management (FREDERICKS, 2011); this can intensify existing tensions. While some were ready to actively work towards recovery, others struggled to implement expected routines. It appeared that the standardized information offered in hospital was not sufficient in addressing patients' moment-to-moment struggles at home. [51]

While the solo concerto movement builds to a grandiose finish that allows the soloist to display virtuosic ability, at four to six weeks following discharge often the patient does not feel prepared to function independently. Other studies have also indicated that recovery can extend much longer than expected and patients may continue to experience symptoms up to one year (GARDNER et al., 2005; THEOBALD, WORRALL-CARTER & McMURRAY, 2005). While some participants in our study carried a renewed resilience, others were anxious about returning to normal routines and not confident that they could arrive at a normalized state on their own. Often, the unexpected and extended recovery period disrupted the expected rhythm. This is a stark contrast to the concerto, where soloists are not only expected to dazzle the audience with their playing, but during the Classical era, it was expected that they would improvise the cadenza during a live performance. Classical era composers such as MOZART and BEETHOVEN were skilled virtuosos who were famous for producing impressive improvised passages. However, they would always later write a cadenza to complete the score for others to play (SWAIN, 1988). As the concerto form evolved in the 19th century, cadenzas were almost always composed a priori, and soloists were given the liberty of following the score or developing their own improvisation (SWAIN, 1988). Although the concerto functioned to highlight the soloist's virtuosic abilities, even some skilled musicians did not feel confident in exploring their improvisational abilities on stage and instead played from the score. In the same vein, participants' stories reflected that they were not ready to be virtuosic without a supportive cast (a cast that at discharge dwindled in numbers and shifted to that of family and friends). Furthermore, the in-hospital patient education and discharge booklet did not appear to clearly delineate the recovery path. As such, participants described struggling to interpret information and apply it to their home context. [52]

Since tensions continue into the home and the rhythm of individuals' daily lives remained disrupted, it appears that patients may benefit from continued support. Peer support can be an instrumental resource in exchanging knowledge and finding comfort in shared experiences (COLELLA & KING, 2004; HARRIS, 2010). Telephone follow-up programs may also be useful resources for individuals to discuss and potentially alleviate concerns (ROLLMAN et al., 2009). We found that it was the moment-to-moment struggles at home where participants needed to speak with someone to help them facilitate an evaluation of their symptoms. Through the lens of a solo concerto, the tensions between and separation of the soloist (i.e. patient) and the orchestra (i.e. practitioners and other caregivers) became more apparent. [53]

Unlike the solo concerto, where there is a designated conductor to guide, the conductor during recovery is a fluid role and at times, absent in participants' narratives. While narratives reflected that the nurse was the clear conductor preoperatively, there did not appear to be an identifiable figure during the postoperative phase. In a concerto, the conductor is integral in ensuring that all players understand their respective roles and are following the same rhythms. Yet, during the postoperative phase, there were numerous individuals, but one key person was not narrated as the main facilitator. Likened to a concerto without a conductor, patients felt lost and rhythms and harmonies were disjointed. As individuals return home and encounter a thinning orchestral cast and blurry score for recovery, they must themselves begin to conduct their own recovery. It may be worthwhile to explore the notion of a designated individual to guide patients and provide continuity of care to reduce anxieties and vulnerability. [54]

By appealing to the senses, music has the power to evoke aesthetic knowing, which may open possibilities for patient-centered care. DeNORA (2000) states that music can impart "shape and texture to being, feeling, and doing" (p.152). As our work has highlighted, the solo concerto facilitates an understanding of the dynamics of recovery, as well as making apparent the focus on physical indicators; although emotional and psychological dimensions of recovery are incorporated, they do not take precedence. Pathway-led approaches focus on the physical body and are reflective of the biomedical model. Emerging in the seventeenth century (CAPRA, 1982), the biomedical model focuses health care discourse on the physical body and a microcellular lens that is reliant on technological, diagnostic practices and treatment of the biological body (FOSS, 2002). Similarly, discharge parameters are focused on bodily indicators trending towards normal limits. We found that discharge was not determined by participants' own readiness and some described a sense of abandonment because they felt that there was no one to turn to with questions. While the biomedical model has brought forth understanding of the human body with enhanced diagnostics and therapeutics (LAPUM, CHEN, PETERSON, LEUNG & & ANDREWS, 2008), it has also led to tensions with a patient-centered care discourse. [55]

Music is an art that is not bound by frameworks and has a dynamic quality to pursue a new way of articulation. The use of music in arts-informed research can be powerful to highlight structural factors that persist in health care. Music can provide a new space to re-imagine a balanced discourse of patient-centered care and biomedical and technological practices. The concerto is a multi-movement symphonic work. However, in our study, it was the first movement form derived from Classical era of western music (1750 – 1850) that facilitated a deep understanding of participants' stories. While the Classical concerto was consistently used in the 18th and early 19th century, composers began to search for new ways to articulate the soloist-orchestra dynamic. As the Classical era of western music gave way to the Romantic era (1850 – 1900) and a postmodern movement, concertos were less structured and orchestral themes rarely initiated the movement. In the concertos of SCHUMANN and MENDELSSOHN, the orchestra commenced only as accompanying voices to support soloist themes (WILLIAMS, 2011). If we consider a postmodern concerto, the patient as soloist and her local and contextual knowledge would become a shaping force of the music (i.e. process of discharge and recovery) and the orchestra (i.e. caregivers) would develop closer attunement to the patient—something akin to a patient-centered approach to health care. [56]

The incorporation of music in health care research is in an embryonic stage of development. A few studies and theoretical papers have discussed music as a therapeutic modality (ANDREWS, KEARNS, KINGSBURY & CARR, 2010; COHEN, 2009; MAZER, 2009) and as a data collection method or an expressive output of research findings (BOYDELL, 2011; JONAS-SIMPSON, 2001). However, there appears to be little to no literature citing the use of music as an interpretive lens or framework for analysis, so our study has fallen in a novel realm of exploring the intermingling of music and health care research. An integral element of our process has been to use music as an interpretive lens in ways that is organic and fluid; thus, it takes shape based on a creative and aesthetic process and shifts with stories. [57]

7. Limitations and Future Research

It is worth noting that this was a secondary analysis in which music as an interpretive lens was employed specific to analysis. Perhaps employment of music earlier in the research process during study design would have transformed interpretation of data and further elicited the patient/soloist's unique frame of perception. However, the solo concerto did not emerge as a viable form until after the primary analysis was near completion. In addition, this study timeframe was restricted to four to six weeks after discharge. Future inquiries of this nature may consider a longer timeframe of tracking participants until they reach the point of being able to perform a virtuosic cadenza. [58]

Music is a broad discipline that encompasses different genres whose stylings evolve with space, time and cultural change. As we engaged with music in this study, our activities were mostly associated with European classical music, with a predominant focus on selections from the 18th and 19th century. This narrowed music selection may have eluded other types of knowing had we expanded our selection to other genres, time periods or ethnicities. It is possible that collaboration with professional musicians or composers may enhance the ways that we perceive the data and expand the ways through which we integrated music. In addition, the uptake of music as an interpretive lens in other areas of health care or other disciplines will facilitate its growth and its rigorous and creative application. [59]

Employment of music as an interpretive lens, specifically the solo concerto, is revealing of the subtle segregation between patients and the rest of their worlds. Although practitioners are intensely supporting the patient's recovery, ultimately the patient is positioned slightly apart. Of course, patients' recovery happens in a social world, but it also happens in the internalized space of the mind and body that is partially obscured. Drawing upon LEDER's work (1990), as practitioners we are only privy to certain internal rhythms of the body that are made visible through technological diagnostics and monitoring, but certain sensations and inner experiences can only be known by the patient. Considering the concealment of the body's inner workings, the patient as soloist who is positioned slightly apart is even more prominent. Furthermore, as the soloist approaches the cadenza, she is left to improvise without a musical score. Similarly, patients have a generalized pathway to guide recovery, but ultimately they too need to improvise and figure out how to perform in an unfamiliar body with unfamiliar sensations. [60]

By highlighting the unique position of the solo patient in the concerto form, it draws us to the importance of patient-centered care. If we consider the patient as a soloist, how can practitioners perform as a member of an exceptional orchestra in ways that better support patients? Practitioners are supporting patients through intensive assessment, monitoring, and teaching that is governed by pathways and focused on returning the physical body to stability. But, does this intensive focus inhibit practitioners from being drawn into the internalized space of the mind and body? [61]

The authors acknowledge the funding support they received related to this project: Ryerson University New Faculty grant (Jennifer LAPUM); Ryerson University Undergraduate Research Opportunities Scholarship programs (Linda LIU); and Ryerson University Faculty of Community Services Seed grant. We thank the research coordinator, Bruk RETTA, for her invaluable contribution to the study.

Andrews, Gavin; Kearns, Robin; Kingsbury, Paul & Carr, Edward (2010). Cool aid? Health, wellbeing and place in the work of Bono and U2. Health & Place, 17(1), 185-194.

Boydell, Katherine (2011). Making sense of collective events: the co-creation of a research-based dance. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung / Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 12(1), Art. 5, http://nbn-resolving.de/urn:nbn:de:0114-fqs110155 [Accessed: January 10, 2012].

Boydell, Katherine; Gladstone, Brenda; Volpe, Tiziana; Allemang, Brooke & Stasiulis, Elaine (2012). The production and dissemination of knowledge: A scoping review of arts-based health research. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung / Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 13(1), Art. 32, http://nbn-resolving.de/urn:nbn:de:0114-fqs1201327 [Accessed: February 15, 2012].

Bresler, Liora (2006). Toward connectedness: Aesthetically based research. Studies in Art Education, 48(1), 52-69.

Capra, Fritjof (1982). The turning point: Science, society, and the rising culture. New York: Simon and Schuster.

Cohen, Gene (2009). New theories and research findings on the positive influence of music and art on health with ageing. Arts & Health, 1(1), 48-63.

Cole, Ardra & Knowles, Gary (2001). What is life history research? In Ardra Cole & Gary Knowles (Eds.), Live is context: The art of life history research (pp.9-24). Walnut Creek, CA: AltaMira Press.

Colella, Tracey & King, Katherine M. (2004). Peer support. An under-recognized resource in cardiac recovery. European Journal of Cardiovascular Nursing, 3(3), 211-217.

Conle, Carola (1999). Why narrative? Which narrative? Struggling with time and place in life and research. Curriculum Inquiry, 29(1), 7-32.

Creswell, John (2007). Philosophical, paradigm, and interpretive frameworks. In John Creswell (Ed.), Qualitative inquiry and research design: Choosing among five approaches (2nd ed., pp.15-34). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Czarniawska, Barbara (2002). Narrative, interviews, and organizations. In Jaber Gubrium & James Holstein (Eds.), Handbook of interview research: Context & method (pp.733-749). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

DeNora, Tia (2000). Music in everyday life. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Doering, Lynn; Cross, Rebecca; Magsarili, Marise; Howitt, Loretta & Cowan, Marie (2007). Utility of observer-related and self-report instruments for detecting major depression in women after cardiac surgery: A pilot study. American Journal of Critical Care, 16(3), 260-269.

Eisner, Elliot (2008). Art and knowledge. In Gary Knowles & Ardra Cole (Eds.), Handbook of the arts in qualitative research (pp.3-12). Los Angeles, CA: Sage.

Elliot, Doug; Lazarus, Ross & Leeder, Stephen (2006). Health outcomes of patients undergoing cardiac surgery: Repeated measures using short form-36 and 15 dimensions of quality of life questionnaire. Heart & Lung: The Journal of Acute and Critical Care, 35(4), 245-251.

Emden, Carolyn (1998). Theoretical perspectives on narrative inquiry. Collegian, 5(2), 30-35.

Foss, Laurence (2002). The end of modern medicine: Biomedical science under a microscope. New York: State University of New York Press.

Frank, Arthur (2000). The standpoint of storyteller. Qualitative Health Research, 10, 354-365.

Frank, Arthur (2002). Why study people's stories? The dialogical ethics of narrative analysis? International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 1(1), 1-9.

Fredericks, Suzanne (2011). Coaching in the cardiovascular surgical population. Canadian Journal of Cardiovascular Nursing, 21(3), 30-33.

Fredericks, Suzanne; Sidani, Souraya & Shugurensky, Daniel (2008). The effect of anxiety on learning outcomes post-CABG. Canadian Journal of Nursing Research, 40(1), 127-140.

Fredericks, Suzanne; Guruge, Sepali; Sidani, Souraya & Wan, Teresa (2010). Post-operative patient education: A systematic review. Clinical Nursing Research, 19(2), 144-164.

Gardner, Genevieve; Elliot, Doug; Gill, Jaswin; Griffin, Melanie & Crawford, Matthew (2005). Patient experiences following cardiothoracic surgery: An interview study. European Journal of Cardiovascular Nursing, 4, 242-250.

Harris, Marianne (2010). Shared medical appointments after cardiac surgery-the process of implementing a novel pilot paradigm to enhance comprehensive postdischarge care. The Journal of Cardiovascular Nursing, 25(2), 124-129.

Jonas-Simpson, Christine (2001). Feeling understood: A melody of human becoming. Nursing Science Quarterly, 14, 222-230.

LaPier, Tanya & Wilson, Brian (2007). Prevalence and severity in patients recovering from coronary artery bypass surgery. Acute Care Perspectives, 16(3), 10-15.

Lapum, Jennifer (2009). Patients' narratives of open-heart surgery: Emplotting the technological. Unpublished PhD dissertation, University of Toronto, https://tspace.library.utoronto.ca/handle/1807/17789 [Accessed: December 1, 2011].

Lapum, Jennifer; Angus, Jan; Watt-Watson, Judy & Peter, Elizabeth (2011). Patients' discharge experiences: Returning home following open-heart surgery. Heart & Lung: The Journal of Acute and Critical Care, 40(3), 226-235.

Lapum, Jennifer; Chen, Sandra; Peterson, Jessica; Leung, Doris & Andrews, Gavin (2008). The place of nursing in primary health care. In Valorie Crooks & Gavin Andrews (Eds.), Primary health care: People, practice, place (pp.131-148). Burlington, VT: Ashgate Publishing Company.

Lapum, Jennifer; Church, Kathryn; Yau, Terrence; Matthews David, Alison & Ruttonsha, Perin (2012). Arts-informed research dissemination: Patients' perioperative experiences of open-heart surgery. Heart & Lung, 41(5), e4-e14.

Leder, Drew (1990). The absent body. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press.

Leegaard, Marit; Naden, Dagfinn & Fagermoen, May (2008). Postopertive pain and self-management: Women's experiences after cardiac surgery. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 63(5), 476-485.

Lie, Irene; Bunch, Eli; Smeby, Nina; Arnesen, Harald & Hamilton, Glenys (2012). Patients' experiences with symptoms and needs in the early rehabilitation phase after coronary artery bypass grafting. European Journal of Cardiovascular Nursing, 11(1), 14-24.

Lieblich, Amia; Tuval-Mashiach, Rivka & Zilber, Tammar (1998). Narrative research: Reading, analysis, and interpretation (Vol. 47). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Lieblich, Amia; Zilber, Tammar & Tuval-Mashiach, Rivka (2008). Narrating human actions: The subjective experience of agency, structure, communion, and serendipity. Qualitative Inquiry, 14(4), 613-631.

Mazer, Susan (2009). Music and nature at the bedside: Part one of a two-part series. Research Design Connections 2, http://healinghealth.com/images/uploads/files/Music_and_Nature_at_the_Bedside-_Part_One_of_a_Two-part_Series__Research_Design_Connections.pdf [Accessed: November 5, 2011].

McNiff, Shaun (2008). Art-based research. In Gary Knowles & Ardra Cole (Eds.), Handbook of the arts in qualitative research (pp.55-70). Los Angeles, CA: Sage.

Rollman, Bruce; Herbeck Belnap, Bea; Hum, Biol; LeMenager, Michelle; Mazumdar, Sati; Houck, Patricia et al. (2009). Telephone-delivered collaborative care for treating post-CABG depression: A randomized controlled trial. Journal of American Medical Association, 302(19), 2095-2103.

Schelling, Gustav; Richter, Markus; Roozendaal, Benno; Rothenhausler, Hans-Bernd; Krauseneck, Till; Stoll, Christian et al. (2003). Exposure to high stress in the intensive care unit may have negative effects on health-related quality-of-life outcomes after cardiac surgery. Critical Care Medicine, 31(7), 1971-1980.

State of the Field Committee (2009). State of the field report: Arts in healthcare 2009. Washington, DC: Society for the Arts in Healthcare.

Stoll, Christian; Schelling, Gustav; Goetz, Alwin; Kilger, Erich; Bayer, Andreas; Kapfhammer, Hans-Peter et al. (2000). Health-related quality of life and post-traumatic stress disorder in patients after cardiac surgery and intensive care treatment. Journal of Thoracic and Cardiovascular Surgery, 120, 505-512.

Swain, Joseph (1988). Form and function of the classical cadenza. Journal of Musicology, 6(1), 27-59.

Theobald, Karen; Worrall-Carter, Linda & McMurray, Anne (2005). Psychosocial issues facilitating recovery post-CABG surgery. Australian Critical Care, 18(2), 76-85.

Williams, Brooke (2011). The connections between the violin concertos of Felix Mendelssohn and Robert Schumann. Doctor of musical studies, James Madison University, Harrisonburg, Virginia http://search.proquest.com.ezproxy.lib.ryerson.ca/docview/867674322 [Accessed: December 1, 2011].

Linda LIU is a pianist and music teacher and in her fourth and final year of the Ryerson, Centennial and George Brown Collaborative Nursing Degree Program. She received a Ryerson University Undergraduate Research Opportunities Scholarship and worked with Dr. LAPUM to develop the use of music as an interpretive lens in this arts-informed study.

Contact:

Linda Liu, BSc

Daphne Cockwell School of Nursing

Ryerson University

350 Victoria Street, Toronto, Ontario, M5B 2K3

Canada

E-mail: linda.y.liu@ryerson.ca

Dr. Jennifer LAPUM is an Associate Professor who has developed an arts-informed program of research in the health sciences. She is a poet and researcher who uses arts-informed methods (poetry, narrative, images) to advance the capacity for humanistic approaches to health care as well as knowledge translation.

Contact:

Jennifer Lapum, PhD, RN

Daphne Cockwell School of Nursing

Ryerson University

350 Victoria Street, Toronto, Ontario, M5B 2K3

Canada

Tel.: ++1 416-979-5000 ex. 6316

Fax: ++1 416-979-5332

E-mail: jlapum@ryerson.ca

URL: http://www.dev.ryerson.ca/nursing/faculty/bios/lapum.html

Dr. Suzanne FREDERICK is an Associate Professor whose research focus is on exploring the characteristics of teaching (timing, mode, dose) and learning (influence of culture, sex, age and education) on health outcomes.

Contact:

Suzanne Fredericks, PhD, RN

Daphne Cockwell School of Nursing

Ryerson University

350 Victoria Street, Toronto, Ontario, M5B 2K3

Canada

Tel.: ++1 416-979-5000 ex. 7978

Fax: ++1 416-979-5332

E-mail: sfrederi@ryerson.ca

URL: http://www.dev.ryerson.ca/nursing/faculty/bios/fredericks.html

Dr. Terrence YAU is a cardiovascular surgeon whose clinical interests include advanced heart failure, heart transplantation, complex coronary artery surgery and valvular surgery. His research expertise is in clinical trials of cardiac stem cell transplantation and cardiac protection during heart surgery.

Contact:

Terry Yau, MD, Msc

Peter Munk Cardiac CentreToronto General HospitalUniversity Health Network200 Elizabeth Street Toronto, Ontario, M5G 2C4 Canada

Tel.: ++1 416-340-4074

Fax: ++1 416-340-3803

E-mail: terry.yau@uhn.on.ca

URL: http://www.uhn.ca/Focus_of_Care/Munk_Cardiac/cardiovascular_surgery/staff_profiles/yau.asp

Vaska MICEVSKI is an instructor who teaches nursing theory and research in the Ryerson, Centennial and George Brown Collaborative Nursing Degree Program.

Contact:

Vaska Micevski, MScN, RN

Daphne Cockwell School of Nursing

Ryerson University

350 Victoria Street, Toronto, Ontario, M5B 2K3

Canada

Tel.: ++1 416-979-5000

Fax: ++1 416-979-5332

E-mail: vmicevsk@ryerson.ca

Liu, Linda; Lapum, Jennifer L.; Fredericks, Suzanne; Yau, Terrence & Micevski, Vaska (2012). Music as an Interpretive Lens:

Patients' Experiences of Discharge Following Open-heart Surgery [61 paragraphs]. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung / Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 14(1), Art. 17,

http://nbn-resolving.de/urn:nbn:de:0114-fqs1301171.