Volume 15, No. 1, Art. 14 – January 2014

Public Library Representations and Internet Appropriations

Paula Sequeiros

Abstract: May the changes in the representations of the public library be propitiated by readers' appropriations of the Internet? To answer this question, a theoretically-driven and empirically-based research was developed in a public library in Portugal, combining the analysis of documents uses, the ethnography of space and Internet use, of social relations developed while reading, with the analysis of representations of the public library. No clear-cut association emerged between social-demographics or user profiles, and representations, in general. No disruptive Internet "impact" was found: Internet use may contribute to reinforce traditional representations of the library, while it may also update and democratise other representations. If the library and the Internet are represented as synonymous, the former does not make sense without the latter; but an Internet widespread and intensive use conflicts with the image of an institution dedicated to high-brow culture. Changes in uses of the public library are, instead, clearly associated with new types of readers, which in their turn reflect changes in urban social composition.

Key words: social representations; Internet; public libraries; reading practices; readers profiles; ethnographic observation; in-depth interviews; Portugal

Table of Contents

1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Framework—From the Research Question to a System of Concepts

2.1 Technology

2.2 Space

2.3 Social representations

2.4 Representations of the Internet

3. Methodology

4. Results

4.1 The space—urban insertion

4.2 Space provided—concepts, form and function

4.3 Space appropriated—general traits

4.4 Emotions

4.5 Personalisation, privacy, surveillance

4.6 Conviviality

4.7 Social differences and inequalities

4.8 Library readers' profiles

4.9 Appropriations of the Internet in a public library

4.10 What is a library?

5. Practical and Ethical Implications of Library Representations

6. Conclusions

A cell phone rings, no one picks it. Several heads raise, there are frowning gazes. There is a calm ambiance, a vivid though not aggressive light flows through large windows. Reading is resumed at other places. At the end of the room almost all seats are occupied: many access the Internet at in-house computers or at their portables through Wi-Fi. People of all ages, of both sexes, are absorbed by screen contents. They spend most of their time e-mailing. Time is not wasted if using dedicated stations, connectivity is timed, there are people waiting for their turn. Between "philosophy" and "foreign literature" stacks, young people chat, whispering. A girl browses books looking for an idea—where is it? Several people are using their laptops in the facing tables, some wear earphones, studying amidst their scattered books and belongings. By the mezzanine, a boy sits motionless, his gaze lost. A middle-aged man glances at a girl in unusual, eye-catching clothes who just came in. Others read some newspaper, sinking into couches. Some peep and take favourable positions, waiting for their favourite titles to be returned. A man, accompanied by his son, takes a nap in a soft couch after lunch time. As if coming from afar, a smothered noise superimposes, at times: children are laughing nearby, a mother runs after one of them, the assistant scolds another "you may not go on top of that!". Two brothers are painting miniature soldiers on a low table, they took paints and brushes off their backpacks while their mother observes them. A little boy plays a game in the computer using his personal profile recorded during previous visits. Downstairs, and seating in couches there are several men leaning back, legs stretched, feet crossed, headphones on, watching videos on large TV sets. Outside, a peacock strolls by a large glazed façade aperture, no one notices it. A homeless man comes in, a tanned skin denotes the lack of a roof, and some others lag behind. A middle-aged woman observes them carefully, "What are those people doing, here?". [1]

This scene is fictional only by making several time segments co-occur in a single moment, the actual events occurred at different moments. They could have happened just so, on a single day and at a precise hour. This is a public library, so much life, so many lives. [2]

What do those people do there, what drives them, what would they say if questioned "As for you, what is a library?", or else "Draw me a library" as SAINT-EXUPÉRY's Little Prince might ask if coming out of one of those album boxes. [3]

Public libraries were created as places for books, as reading spaces. What are they nowadays? A place where playing is allowed, where the Internet is intensively accessed, is it still a library? More precisely: imagine, many years ago, someone sitting in a library, surrounded by envelopes, paper and stamps and updating her personal correspondence—would that be allowed? Those practices seem to have sneaked into a place where they were not expected, the Internet appears to have paved the way for them. [4]

The Internet is presently accessible within public libraries in Portugal. State directed programs for this purpose started in 1996. Public libraries do not have e-mailing software installed, readers use Webmail interfaces instead. The Internet is an appreciated resource, connectivity is intensively used, and a few readers visit the library only because of it. Along with this, public library usage has changed in recent years and research on actual reader's uses, including Internet uses, remains scarce. So the research question emerged: while affording new practices within public libraries, is the Internet also shaping changes in readers' representations of what a library is? If so, what is the direction of those changes, what is their meaning? [5]

This is a succinct description of the questioning underlying a research project I developed from 2008 to 2010 (SEQUEIROS, 2010). The following text will give an account of its theoretical and empirical building and of its final results. First, I shall address theoretical/conceptual issues. Second, the reasons for my methodological options are stated. Third, I present the main results, arranged according to the analytical categories constructed from empirical data and from previous theory, which include the design of case-specific readers' profiles and the representations of what a public library is. Fourth, I discuss these representations, considering their differences as to practical and ethical implications of their mobilisation in libraries for prescribing and legitimating practices, and for policy change. Finally I conclude with a synthesis of these results and interpretations, with remarks as to occasional limitations and clues for future directions in this line of research. [6]

2. Theoretical Framework—From the Research Question to a System of Concepts

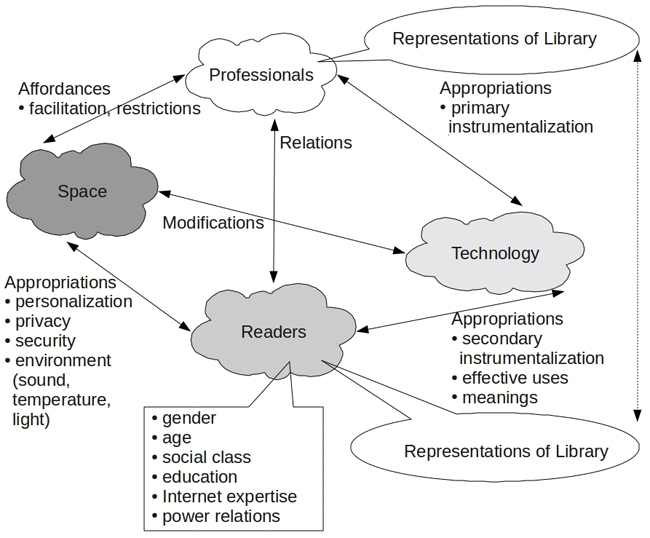

To answer that question, I drew a conceptual map to depict an approach to reading practices, including the use of documents, space and the Internet, which might contemplate for the social relations developed while reading, and which could facilitate the analysis of representations of the public library. Three main concepts and their inter-relations emerged then as fundamental in this theoretical frame: technology, space and people, especially library readers but also library professionals and managers. [7]

Next I will briefly present the theoretical contexts where the concepts of technology and space were borrowed from, to provide those terms with a more precise and deeper meaning. Likewise, I shall refer to the concept of representations I adopted for this research. [8]

E-mailing and chatting are common and popular uses and motivators for visiting a public library. Their intensive use has already been documented for Canada (CURRY, 2002), the United Kingdom (BOUGHEY, 2000) and Australia (HARDY & JOHANSON, 2003). [9]

In my view, though, these practices became more tolerated than accepted. This communicational facet was not previously foreseen in libraries objectives and sometimes it was even discouraged (HÉDON, 1997) more at an informal than at a regulatory level, according to research done at another and at this Portuguese public library (SEQUEIROS, 2004, 2010). Actually, I am persuaded that Webmail interfaces eventually propitiated the contouring of restrictions—namely the absence of installed, dedicated software—which were initially placed on emailing and chatting inside public libraries. [10]

Technological artefacts, produced within specific historical and social conditions, are the product of those very conditions. Simultaneously, they are also able to shape social life as people relate to produce and use artefacts, according to Andrew FEENBERG (1992). That is, the humans/artefacts relation, being framed by society, especially by social-economic and power relations, is still a bi-directional and non-deterministic one. The assumption that technology may only be understood within the particular context of its application results from this premise (FEENBERG, 2002, p.45). A particular trait in FEENBERG's approach (p.76) is that technological artefacts have, from inception, sets of rules embedded in their core which classify activities as allowed or forbidden, and that these rules are associated with a specific meaning or a purpose which, in turn, explain that classification. However, an artefact may be appropriated for unforeseen, undesired purposes through the tactics of users—a secondary instrumentalisation—resisting and contouring the underlying strategies of those with the power to conceive it and develop it—through a primary instrumentalisation (FEENBERG, 1992). And so the apparent neutrality of technology is deconstructed: purposes and ends are intimately tied to technology uses; and, although invisible, the interests, social positions and values of the social groups that develop technological artefacts underlie the rules of their usage. This, in its turn, explains how artefacts produce but also reproduce values associated to forms of social hegemony. Furthermore, ethical and political dimensions are thus added to technology studies from this theoretical point of view. Within this dynamic configuration, technology may then be regarded as propitiating changes in practices, representations and social relations within the spaces where it is applied (FEENBERG, 1992). It should be noted that propitiation and affordance are terms currently associated with non-deterministic approaches within the field of technology studies. They refer to inbuilt, preconceived or not, attributes thought to facilitate or inhibit certain appropriations of technology, as opposed to attributes thought of as determining the forms of appropriation. [11]

The places chosen to read in may vary from person to person, some prefer absolute silence, others avoid it; some prefer comfortable, cosy places, some read even while standing in public transportation. However library buildings aim at attaining a level of specialisation and technicality that provides for optimal conditions. Aesthetics and symbolism may also stand out as relevant features, especially if bearing in mind that these are frequently public, eye-catching buildings, associated to institutional power. [12]

The activities of public library readers and the social relations developed among them and with the staff take place within spaces purposefully designed or requalified to house such activities. So, a theoretical perspective of space focusing on relations and activities appeared to be fit for this analysis. Such is the perspective of LEFÈBVRE's social-spatial theory (1991 [1974]) which begins by asserting that space simultaneously produces and reproduces social practices, being both their condition and their result; deriving from social-economic past relations, from specific historical contexts, space also shapes future actions, affording or forbidding them. Space is an object of study difficult to seize: visibility, tied to a sensorial dimension, tends to overburden an initial approach to space through a saturation of images. The formal, aesthetic dimension conceals, more than it unveils, the sociability of space. A comprehensive analysis of space requires that other senses and reflexivity are convoked so that the dimensions of structure and function add to and interlink with form. [13]

Ownership of space, in the particular case of public libraries, may be easily conceived of, but the same does not necessarily apply to the power issues underlying the use of space. Accordingly, not only the dominated but also—or even especially—the appropriated spaces must be researched, as the latter reflect the power of the weak. Users tactics deployed to circumvent strategic issues embedded in spatial design are a central theme in CERTEAU's work (1984). Special attention was dedicated to spatial appropriation and to practiced space, along with ethnographic hints to overcome the dominance of the eye—space visibility—and to be able to observe users' actual practices by moving through it and resorting to another sense—kinaesthesis. [14]

Thinking about a public library forms a mental image charged with symbolic, emotional, cultural values, and this image may not resemble the one held by others visiting the same library as ourselves. Though our personal or vicarious experiences may be diversified, we tend to think of objects through shared mental images which condense the meanings we attach to them (JODELET, 1984). These images act like categories, organising the way we think and integrating new knowledge into pre-existing knowledge systems. Social representations also have practical features as they orient, give meaning to and structure reality and actions upon reality. Presenting some individual traits, representations are nevertheless socially constructed, reflecting cultures, values, ideologies and traditions of social groups. As shared constructs, they allow us to communicate with others. [15]

In their construction process, representations are anchored in the shared social realities they refer to, revealing the dynamics that encompasses them. Representations may undergo objectification processes, e.g. when inertia makes them crystallise in times of change. Contrasting features of rigidity and innovation tend to coexist, even within a singular system of thought. [16]

I shall now address the interrelations among these main concepts and which aspects or conceptual facets I focused on. [17]

2.4 Representations of the Internet

Previous research by BRUCE (1999, p.191) pointed to the fact that a few categories are fit to describe how users think of the Internet and which are the analogies most frequently associated to them: "web/grid/road system: analogies stressing connectivity and structure"; "information store/library", stressing information aspects of the Internet; "brain/large organism", are analogies with a living organism. [18]

Researching the metaphors commonly used to refer to the Internet, HØYLAND (2001) concluded that the metaphor of place is the most widely used, the Internet being frequently thought of as a world. As the technology became more pervasive, metaphors evolved then to more complex forms—such as biological or viral war—and others lost their weight as the information highway. In contrast to its technical infrastructure, the Internet is rarely thought of as a net. Next to space, the metaphors of path and force are also recurrent. [19]

Referring to the spatial metaphors so popular in our imagination and speech, KLAINBAUM (2006, Chapter 4) advances the idea that they are shaped by the sense of "movement through information" afforded by the Internet, along with the social interaction experienced while navigating. [20]

CAVANAGH's contribution (2007) is also of importance for this topic, in that she stresses that the metaphor of space is presently being replaced by metaphors based on networks and connections, due to the massive commodification of the Internet and its appropriation by large businesses. She also alerts to the fact that the metaphor of network is ideologically contaminated by the pre-notion of a network society, a society supposedly homogeneous, libertarian and participative. [21]

The following conceptual map depicts all these concepts and their interrelations conceived as a result of this theoretical analysis. It should also be noted that, as the empirical work advanced, the definition of the limits of concepts, the facets—e.g. analytical dimensions—considered for each concept, and the interrelation of concepts became an ongoing effort, both reflecting stages of clarification of ideas and procedures, and also contributing to their advancement and concretisation.

Figure 1: Conceptual map [22]

While trying to understand a probable connection between reading practices and social representations, I became interested in designing an approach that might provide results from an intensive analysis of the context for both the practices and the representations. Taking into consideration the meanings that social actors and actresses give to their doings and thoughts was also central to this research design and fit the research questions. For this purpose, Michael BURAWOY's extended case method (1998) was adopted as an adequate and central methodological frame. [23]

This method highlights the principle of reflexivity: theoretical advancement is produced departing from existing theory, to reconstruct it and improve it—theory does not simply emerge from data. Reflexivity combined with ethnography—a method to research what communities actually do, to contrast expectations or norms with actual practices, to provide a rich analytical context—open up for results that question asserted common sense or scientific theories. A single case, although unique by definition, may provide results which are transferable to similar contexts, in a way similar to individual learning constructed from vicarious experiences. [24]

Complexity is another principle sustained by BURAWOY, and one which is specially stressed by feminist theorists: human societies are complex, diverse, and societies should be envisaged as shaped by processes which are heterogeneous, locally and historically framed, and therefore simplistic cause-effect explanations should be avoided, along with the traditional binaries that constrain scientific thinking—e.g. subject and object of knowledge, male and female, dominant and dominated as a simplistic, "black & white", positivist way of thinking about society. [25]

The need to construct a dialogical relationship with the observed, searching for their own interpretations and socially constructed meanings, and a need for the researcher to be committed with the purpose of her/his investigation are also principles of importance in HARAWAY's approach (1988) which I adopted. [26]

Envisioning public reading in libraries as a public service, I assume my commitment with the provision of democratic spaces to be enjoyed as places of encounter and discovery (AUDUNSON, 2005; CALHOUN, 2005), for culture, leisure, information or learning purposes and also assume that the provision of reading resources is to be collectively enjoyed by communities. [27]

Almeida Garrett Municipal Library in Porto, Portugal, was chosen as the object of this study. Inaugurated in 2001, it had since maintained high occupation levels, its readers were socially diverse; it had a purposefully designed building, with innovative solutions making it a case study in the architectural field. Apart from its updated holdings, there was wired and wireless Internet access and several computers were available for public use. Contrary to heritage libraries, recreational reading was a common activity, along with studying and news reading. The Portuguese Institute of Public Libraries and the Book was also consulted to inform this choice. [28]

Ethnographic observation was directed at readers' practices for several days, at different times of the day (BURAWOY, 1998) from March 2008 until the beginning of 2009. Special attention was paid to preferred places, to all activities besides reading, and to conflicts, accessibility, gender and age distribution of visitors, attitudes, and body postures in the different library areas. Observation was particularly useful to compensate for the difficulties readers felt in expressing orally how they used and felt this space, as well as to trace reader's tactics, e.g. the tricks they used to access highly requested resources, such as daily newspapers. Photography helped to analyse body postures and facial expressions, subsequently. [29]

I also used in-depth, semi-structured interview techniques (KVALE, 1996; SEALE, 2004) to analyse the practices and discourses of readers, staff, management and architect, while I made an aesthetic and functional analysis of the building and its insertion in the city. Informal talks with several staff members proved to be valuable for their opinions, doubts and clues. In order to communicate with young children, I asked them to draw me a library (EDER & FINGERSON, 2002). This was complemented by informal conversations with them and with relatives or teachers accompanying them. [30]

For these interviews, a non-probabilistic theoretical sample was constructed according to the perceived social diversity in the library, taking into account gender, age, occupation, ethnic origin, visual and motion disabilities, and power relations. I interviewed twenty-nine users, one library manager, two assistant librarians, the maintenance supervisor and the architect. Readers were occasionally asked to evaluate space while moving through the very places they were referring to, which helped to clarify their statements. [31]

Almeida Garrett library was built inside the city's largest public park. Its recently re-qualified gardens preserve their romantic layout and include a diversity of large-sized centenary trees. This park has a privileged view over the river Douro. It lies within fifteen minutes walking distance from Porto's second, modern centre, and within less than twice the distance from the historical one. An enormous domed pavilion, built in 1956, replaced the 19th century iron-and-glass Crystal Palace, which gave its name to the park. A children's park is also to be found. Palácio is a frequent leisure destination, especially for families with children. The area is well served by public transportation. [32]

Excerpts from statements collected during interviews and informal conversations shall be quoted in the following paragraphs. [33]

"To bring a garden into the library without carrying a building into the garden" was his main concern, declared the architect José Manuel Soares. The 900 m2 building has a main façade of UV filtering glass concealed by a curtain of halved pine wood logs transversally aligned, preventing over-exposure to sunlight and allowing for "transparency" towards the garden and for "maintaining a relationship with the surroundings and the specificity of the place". [34]

Although only children make a point of visiting the park itself, several adults felt that the library is "integrated in nature", as voiced by a female reader (28 years, unemployed, degree in management), and also that "it eases your mind", in the words of a frequent male visitor (retired). [35]

4.2 Space provided—concepts, form and function

The architect was given two main guidelines by the town Councillor for Culture: a library welcoming enough for those about to have a first contact with books, for students, or just to read a newspaper and a building in continuity with the public space. But, "contrary to a shopping-mall", he planned for a sense of orientation, and for an occasional sighting of the relation with the city. He also provided for a diversity of areas, with the possibility for creating "our own secluded spots", "within a great unity", while providing a "debatable space" adaptable over time. Profiting from EU funding, the budget allowed for experimentation and for the use of noble materials. [36]

In this three levels building, he tried to use the hierarchy of spaces to create areas with decreasing noise, to allow for a visualisation of the whole space and also to dissociate levels from the status of future dwellers, a common feature in public buildings. The lobby extends across two levels. An art gallery is on level two, a white marble staircase leads to the reception desk of the library in level one. An auditorium and a cafeteria share this level with the main library's reading spaces. An elevator is publicly available for all levels, the technical services and the garage are on level zero. [37]

Light coloured wood was used to cover the floor and for furniture. The glass walls display the garden's and the city's life, the few blind walls are painted white, the ceiling has a wavy surface for acoustic improvement. [38]

In a slightly lower floor, closest to the reception, is the children's area including a room for the aloud reading activities. The reading spaces for adults spread across two levels and a new visitor may easily understand there are several areas being used for different activities although no clear physical separation exists among them. The exceptions are some specialised places: a workstation is dedicated to the blind and amblyopic in level one; the void of the centrally located mezzanine reveals the multimedia area in the inferior level; the Internet may be accessed from several in-house computers placed together but also through wireless connection. [39]

4.3 Space appropriated—general traits

Several readers referred to the building positively, as "very pleasant", "cosy", frequently mentioning its luminosity and transparency. I interpreted this transparency, above all, as a hypallage (LEFÈBVRE, 1991 [1974])—the transference of a physical quality to an emotional one—used by readers to express the ambiance of openness and tranquillity they sense. And also as an architectural successful translation of the concepts of free access and circulation, inscribed in the construction program. [40]

Silence was not an important issue, some, mainly the younger, preferred a light murmur to an absolute silence. Complaints occasionally arose from cell phones ringing. Actually, users were the ones pressing for silence, especially frequent users, not librarians (SEQUEIROS, 2011). In this and other respects, a tacit code of conduct (CERTEAU, 1984) was being enacted, while no formal regulation was in force except for the use of Internet workstations. Some complaints about noise were actually triggered by readers who felt that some others, such as homeless persons, were out of their milieu for not complying with the "estimated legitimate practices" (BOURDIEU & DARBEL, 1966), the adequate attitudes and body postures. [41]

Generally readers declared they found there a pleasant, collectively woven ambiance, adequate for reading, not separating but rather amalgamating sensory—noise included—, aesthetic, social and affective dimensions (LEFÈBVRE, 1991 [1974]) in the recurrently used term ambiance. For this reason I advanced the concept of reading atmosphere to name this multidimensional reality (SEQUEIROS, 2011). [42]

Reading, by itself, builds a personal space on top of the physical space. Aural technology—MP3s, CDs in portable computers—is used by many, especially students, to create yet additional space and to reinforce privacy (BULL, 2006). [43]

Accessibility is ensured, inside the library, for readers with motion disabilities. [44]

Readers also spoke of their emotions while reading in this library. Beyond from the already mentioned feeling of openness, tranquillity, organisation, and concentration were also referred to as traits they valued. Students referred to a feeling of togetherness (BAKARDJIEVA, 2003), to a form of "intrinsic order" (female student, 40), as a collective sense of concentration stimulating their individual tasks. [45]

For some, becoming a reader in a public library was an accomplishment to be proud for, as a result of overcoming social-economic constraints or disability barriers. [46]

4.5 Personalisation, privacy, surveillance

The mezzanine was originally equipped with wooden top, waist-level removable shelves. Readers began removing the shelves, pulled chairs from adjacent tables, and started using that wooden surface to work upon, as I mentioned. The management accepted this change, and presently this is one of the most coveted areas. Other particular forms of space appropriation and tactics for place-making were observed. Children are allowed to bring in toys and drawing materials, some tables have a special lining for these activities, and a hand-washing basin is available nearby. Additional space is sometimes created and reserved by readers, particularly students, through the tricks of a silent competition (CERTEAU, 1984): scattering personal objects over adjacent tables is a signal that company is unwanted. [47]

Readers' privacy requirements revealed to be associated to gender or social class and also to housing conditions: a young woman disliked being stared at "in an unpleasant way" by men, while the homeless reader was not bothered by other readers peeping into his PC screen; the young couple with two babies, living in a single room of a social-housing apartment with twelve other relatives, and the 40-year old woman living in a therapeutic community, all felt that the library was the only place where they could enjoy some privacy. [48]

The most socially or physically fragile—the man wearing clutches, the homeless person, an African immigrant—were those who appreciated being in a library the most. The library is sensed as a safe space. [49]

Reading may not be a solitary activity: children are usually accompanied by adults, adolescents and young adults enter in pairs or groups, frequent users appreciate watching familiar faces and "pleasant gazes" (retired male reader). A public library is a place for conviviality, loners were numerous there. Proximity without propinquity (PARK in TONKISS, 2005) is frequently sought in urban centres. Casual interaction among readers was common, especially within the same activity areas. [50]

Social diversity may be appreciated, seniors like watching younger people and children, the homeless reader declared to enjoy the existing social and age diversity. [51]

Conviviality, alongside with gratuity, was one main motivator for visits, according to the interviewed, confirming GIVEN and LECKIE's view that "libraries may need to do more to encourage the view of 'library as interactive place' versus 'library as quiet space'" (2003, p.382). The conviviality role of libraries has been evoked in literature (AUDUNSON, 2005; AUDUNSON, VÅRHEIM, AABØ & HOLM, 2007; FISHER, SAXTON, EDWARDS & MAI, 2007; GIVEN & LECKIE, 2003; LECKIE, 2004) notably as places with no consumption requirements (AABØ; AUDUNSON & VÅRHEIM, 2010). Low-income people use libraries to meet others more than high-income ones, in cases reported by AABØ et al. (2010). And in times of economic recession, libraries providing public, free resources may register an increasing use (AMERICAN LIBRARY ASSOCIATION, 2010; BERTOT, JAEGER, MCCLURE, WRIGHT & JENSEN; LAIDLER, 2008; LECKIE & HOPKINS, 2002; LIZDAS, 2009; OBLANDER, 2008). [52]

4.7 Social differences and inequalities

This library, as most libraries in Portugal (FORTUNA et al., 1999), is predominantly used by students and intellectual or skilled professionals. Both unskilled workers and upper-class readers were almost absent among the interviewed. Less educated readers seemed to have a preference for the multimedia area: "upstairs is more for reading, down here is more for leisure, to be more relaxed" (truck driver, in his 40s, immigrant, African ethnicity). Bodily postures observed there denote this relaxed attitude. [53]

As to gender, male visitors appear to prevail slightly. However, a gender difference was clear in the absence of middle-aged and elderly women, their leisure time being most likely more confined to domesticity. No evidence for ethnic segregation was observed nor reported during interviews. The most economically deprived showed a particular appreciation for this public service and a concern over its future as such. [54]

A retired female reader felt uncomfortable with the presence of "those social exceptions"—the homeless readers—for allegedly making "lots of noise" and sleeping in the multimedia couches, while another male retired reader stated: "you accept them, they also have the right to be here ...". I could observe several readers taking a nap, mostly after lunch, and not being disturbed for it. The homeless may be just an urban figure serving as a scapegoat for subjective insecurity feelings which amplify real insecurity situations (FERNANDES, 2003). The fact is that some users complained about the way couches were being used and the staff remarked that TV sets were being occupied for too long by homeless and other unusual readers. [55]

Subsequently, the management decided to remove one TV set and this place became the object of additional control. All this made the multimedia area a place where social inequalities and power relations were made visible, at least at a certain time. On the contrary, the appropriation of space in the mezzanine was not opposed to. Very likely, the fact that it was being used for study and research, and the type of users initiating this change—mostly students—accounts for the different responses from managers, staff and other users. Here, both the users and the usages were associated to conventional and serious library visits, while more leisurable practices and less educated people were not. [56]

I relied on HARAWAY's view (1988) on the use of metaphors to add sense to the features of readers' profiles, profiting from common situated knowledges, such as characteristics associated to animals in folk tales, and simultaneously profiting from values and meanings declared by the observed, themselves. As this library is located inside a large garden where animals occasionally appear, the following metaphors arose (for a detailed description of these profiles, see SEQUEIROS, 2013). [57]

Occupational users want to occupy their time actively, being presently employed or not, and so organise their activities in detail. Their stays may last for the whole day, several days or one week. They feel motivated by an environment that favours study and by the use of free resources. They may search for some matter of personal interest or prepare for job competitions. They occupy tables to write and plug in their laptops. They prefer the same regions as students and scholars, further referred to. [58]

Strolling readers have no specific purpose in mind, just stroll around and spend time in a pleasant and accompanied way, although generally not interacting. While doing it, they glance at displayed documents. Less qualified, they are manual workers, retired, unemployed people; some are children. Above all they use the multimedia area, couches, circulating zones. [59]

Recreational readers search for a recreation and conviviality space within this library. Sometimes they bring in their own toys, attend events, especially aloud reading. They may join other children in games, or take part in some school visit. The most often used regions are the children's and the multimedia areas. Almost all of them profit from the opportunity to take a walk in the garden or go to the children's park. Not all of them are children, an interviewed adult appreciates the multimedia area to relax in. [60]

Student readers enter the library sometimes in groups or pairs. Their ages range from 24 to late 30s. They are motivated by conviviality, and a relaxed, togetherness environment. The library's bibliographic resources are not much used; they visit it as many university libraries do not allow group study. They carry their own books, laptops, and some use mobile audio, such as MP3s, to create additional privacy. They prefer tables near power sockets, workstations with Internet access on ground or inferior floors, sometimes reserving extra space by scattering personal belongings. They may require silence from other readers; some prefer a light background murmur to a complete silence. [61]

Scholar readers indulge in researching some favourite theme, frequently local history, studying autonomously at their own pace. Conviviality also draws them. As experienced users, sometimes frequent users, they know every corner. They take notes and write essays. Their discrete presence is highly regarded both by other users and staff. [62]

Informed readers' aim is to keep up with the news from newspapers or magazines. Usually, they do not read other documents, just a few of them use the Internet The elderly predominate, they are almost exclusively male. Their motivations, may be reading as a mental exercise to prevent memory loss, getting outside their homes, meeting other people. They tend to be reserved persons, no significant social interaction was observed. Their attitude is discrete, not so relaxed as in the multimedia area. They occupy the press corner and the sofas which have a high rotation all day long, readers sometimes having to wait for their turn. [63]

Resident readers are a subgroup of regular visitors, but not a subgroup of any particular profile characterised previously. I borrowed this term from the staff who use it to refer to this group of persons who usually visit the library several hours a day, several days a week. They tend to concentrate around the mezzanine as a privileged spot to visually control the whole place. This subgroup is mainly composed of scholars but also of occupational readers. [64]

These mainly elder and male readers may benefit from the special care of an attentive female librarian who may enquire on their health if she notices an occasional absence. They use the complaints book, a resource scarcely known to other users. This familiarity, their positioning within the space and the frequency of their visits all facilitate their acting as a pressure group. They have a noticeable role in the tacit regulation of conducts, namely in the production of the reading atmosphere. [65]

4.9 Appropriations of the Internet in a public library

Readers must use a card to access the Internet through a library computer, being allowed one hour per session, or two if there is no waiting queue; if logging in from a personal laptop, an ID and password are required. The system controlling these cards is also enabled to filter searches, although readers are not alerted to this constraint. Considering that the library holds several titles that may be considered controversial, this option stands not only unjustified, but also as elusive and incoherent. Filtering systems have been considered unethical, and inefficient for not being able to detect the context associated with the terms they blacklist (HEINS, CHO & FELDMAN, 2006; MINOW, 1997; SEQUEIROS, 2007). [66]

Apart from a current and intensive use for e-mailing and chatting—also researched in other public libraries—the Internet is used in as many diverse ways as there are library readers. Uses go from reading newspapers online, above all the foreign press, collecting medical and child care information, locating job offers, doing searches for school assignments, gathering information on leisure activities and travelling, practising information and communication technology (ICT) skills, to visiting sites, and to accessing religious contents. Two interviewees also posted to their blogs from there. Almost all Internet readers are cumulative ones: they read several types of documents in different document supports. A few go to the library expressly to access the Internet—their personal narratives involved severe expense cuts at home and unemployment, or else finding a pretext to get out of home and meet other people. Some also said that they would not return to the library, or that they would visit it less, should free access come to an end. The library's workshops on Internet use and the support by the staff were highly valued. [67]

Just a few of the interviewees were non-Internet users, and, coincidently or not, all were elderly persons. Their reasons to stay away from the medium went from finding it non-reliable, not so in-depth as printed books, to not wanting to get addicted or to conceiving the Internet as being able to unconsciously influence them when writing their essays. [68]

Not all the interviewees were comfortable when it came to define what a library is. If a spontaneous answer did not occur, I proposed the association of a library with other similar places (home, school, coffee shop) or tried to elicit some meaningful keywords in association to the public library. Children were asked to draw a library. [69]

From all the collected answers, no generalised association between representations and readers' profiles, social class, gender or education was signalled. The only clear association found was with students reading activities, as further detailed. [70]

It should be noted that associations with similar places were discarded by readers and that, in general, the library was felt as a unique place. The association with a bookshop only emerged once to express the positive difference of a library being used for free. The comparison with home emerged for those not having satisfactory housing conditions, the homeless reader, the student living in a therapeutic community; the couple living within the crowded apartment stressed their idea that it was not like home precisely because home was not a pleasant place. [71]

Asked whether they saw themselves above all as readers, users or clients, almost all of them chose the terms reader or user. In Portuguese, this differentiation is clearer since there are two words, utilizador and utente, to designate a user in Portugal; the former is currently used by library professionals to designate their readers, being also used to refer to ICT users, for example; the latter is directly associated with public services and it was the only one readers picked from those two terms. [72]

A reader (young father visiting the library with wife and their two small children) explained that he felt he was a user because of the similarity with a health care system user—"we even get cards as well"—because health services were free too. In a similar line of thought, several readers expressed concern about foreseeable cuts in library services, as cuts in other public services were already implemented. [73]

Leaning on the knowledge I gathered from behaviour in other Portuguese libraries, I am convinced that this particular library's features as to spatial and social interaction may be responsible for responses which might not be found in other more traditional public libraries. [74]

Readers' representations are presented next, categorised for an easier treatment and interpretation. [75]

The majority of the interviewed readers picture the library as a collection of diverse, abundant, available, and free of charge resources to be explored collectively. All of them being cumulative readers, the Internet is referred to as a resource among others. All the children's drawings depicting what a library is contained computers. [76]

The Internet integrates this representational image of resources, in coherence with a traditional vision of the library as an encyclopaedic container, in a manner signalling no disruptive or revolutionary changes. [77]

At a representational level, this similarity between libraries and the Internet emerges in some texts, as signalled by BRUCE (1999, p.191). KLAINBAUM (2006, Chapter 4) refers to it and, furthermore, stresses the social interactional dimension of the Internet. [78]

4.10.2 A library is entertainment

This is a current category evoked by readers with diverse use profiles, one that is shared by people who like to engage in magazine reading, in children's activities, and in film watching. [79]

Knowing that communication is the most frequent purpose for Internet usage in libraries, it is likely that online conviviality may be reinforcing this representation, most of all, updating and making it more popular, in line with what is happening in other countries where less scholarly and more popular purposes are assigned to public libraries. [80]

4.10.3 A library is a place to work

In similarly frequent answers, the library is represented as a place to study and research, congregating above all, as might be expected, answers from users with the reading profile of students, of occupational readers and some Internet users. [81]

Holding organised collections, with an atmosphere of togetherness and concentration, being also a space of relaxation and where spatial appropriation is allowed, the library is a place represented as a good alternative to being at home, a place where it is possible to chat in a low voice, to meet others, to listen to music while studying. These characteristics also sustained why these readers preferred a library instead of a coffee shop or a shopping-mall. [82]

Unlike all the others, this representational image is clearly anchored in the personal daily life of these readers, and a very self-centred one as far as the social group of students is concerned. The association to Internet use is clear, many of these readers use the wireless connection. [83]

In accordance with an instrumental reader profile, an instrumental use of the library space was conceived as place plus connectivity. [84]

Some readers equated library with culture, although using different gradients for this concept in their speech: from erudition—"a cultural cathedral"—to an everyday, common use—"a cultural centre". One of them is a female cumulative reader, who occasionally uses the Internet, although she questions its reliability. Another retired reader, a male, does not use the Internet for fear of losing originality in his writings. A third one is a highly skilled middle-aged unemployed man, who conceives the library through a mixed image of culture and resources. Coincidentally or not, the ones representing the library solely as culture are both elderly persons who dissociate cultural practices from navigating through the Internet, thought of as a popular and uncontrolled medium. [85]

4.10.5 A library is connection

In other words, a library is the Internet. This is how two adolescent sisters, living in a nearby social housing project, expressed their representation. They only go to the library when their home access time expires. The question arising here is precisely whether this type of users will increase in a near future, as it seems likely to, making way for a relation with the library not through public reading but through free access to the Internet, "as in a post office station", borrowing the words of a fellow librarian. [86]

Other sparsely mentioned representations picture the library as a space of discovery: "it is a wrapped package with a bow; and the moment you open books looks like you're opening a gift" (female student, 40 years); being a place to study "it can also be a surprise" (male student, 22). Or they picture it as a place for "learning", for "personal development" (female student, 37). All of these were Internet users. [87]

4.10.6 The representations of professionals

One library manager expressed her conviction that a library is "a public service, and so, preferably free of charge", a place where "everyone is welcome, propitiating access to books, information, films, a series of information and cultural services". [88]

Another one had a different conception: it "is OK" to have Internet access to attract users, but if they only go there to e-mail or chat then the library would be in real "danger" of "doing exactly the same as a coffee shop with Internet" does. She sees access as a means to seduce users into superior activities, such as reading books or attending the community of readers' sessions, as a path to individual improvement. [89]

Among assistant librarians and technical staff the collected images pointed to a place which allowed for diversified uses, from culture to leisure, to conviviality, according to personal tastes. It should be noted that these images, I believe, are tied to this library's specific organisational culture, as the paternalistic tone of "cultural improvement", almost absent here, commonly permeates library professionals' discourses. [90]

In the architect's discourse, a similarity with that of some readers could be found; for instance, when he referred to the fact that this is "a collective space" with the possibility for "strong individualities", and a place to enjoy resources in diversified ways. [91]

5. Practical and Ethical Implications of Library Representations

Representations are forms of knowledge orienting towards action, prescribing and legitimating practices. Accordingly, how may the mentioned representations be mobilised in the cultural or leisure fields and what are the ethical dimensions underlying those representations?

Representing a library as resources points to a vast openness of practices, being vague as to actual uses, it does not exclude or prescribe any specific kind.

Picturing the library as entertainment is seldom a purpose for advocacy in the national professional milieu, although it may lead to frame diversified and popular uses of public libraries.

As to a library as a place to work, it should be noted that no declaration from interviewees verbalised some form of self-assigned superior status. However, this image, although associated to an instrumental use, a use closely tied to the educational system, is frequently evoked by library managers to legitimate funding requests, which, even if meaning well, eventually de-qualifies all other uses.

Representing the library as culture is the image that requires, in my opinion, a more critical reflection for three reasons. First, because I think it is very common among professionals in other libraries. Secondly, because according to these results, it scarcely coincided with the representations of readers. And finally because this is the representation that lacks an ethical foundation the most: this representational frame conceals the idea that only those with the legitimate credentials of an "appropriate" culture are welcome. It excludes popular culture and recreation—where the Internet is comprised, according to some declarations—opening a space, at most, for practices serving as a springboard to reach the "right" culture or practices directed at the "betterment" provided by studying. Not surprisingly, a reader who adhered to this representation expressed her uneasiness for having to share the space with "those social exceptions", the homeless persons or those not exhibiting the adequate manners to be in such a place. Likewise a library manager feared that an intensive Internet use might collide with the cultural features of a public library. [92]

The Internet is nowadays a resource adding to the previously existing resources in public libraries, modes of reading being frequently cumulative. Some go deliberately to the library to access it. This technology is being used in line with everyday practices and interests, and notably as a relational tool, connecting friends, relatives and co-workers. Surfing in a conviviality ambiance and accessing it for free, as a public service, reinforces identities and meanings associated to it. Staff support is appreciated and a motive for visits, in what the public library differentiates itself from other facilities providing access. [93]

Library readers represent themselves as users of a valued public service which they wish should continue to receive funding to pursue its purposes. Many among them represent the library as a collection of diverse resources for diverse uses, as entertainment, as a place to study, as culture or as connection to the cyberspace. Only among students was an association found between a social condition and a representation, that of a place to study in. Other representations did not present associations to social class, gender, ethnicity, education or reading profiles. [94]

Contrary to common-sense assertions, Internet integration within a public library did not impose fundamental changes on the representation of what a library is. Paradoxically, if represented as resources, the Internet is another resource adding to the traditional ones, and this image is updated and reinforced in its encyclopaedic dimension. When represented as entertainment, Internet appropriations for communication purposes also integrate within a pre-existing image, while simultaneously popularising and turning it more consonant with contemporary times. When represented as a place to study, Internet use affords new forms of work in an updated continuity with a traditional role, while it also guarantees the continuous visits of students and occupational readers. The library as connection is a representation that totally adheres to these technological propitiations, being a condition for the presence of a particular type of user. The only negative association with the Internet was found in some forms of representation of the library as culture, and this is only if culture is equated with privilege. In these specific forms, readers conceive library usage as bestowed on a cultivated sector and not on a vast audience without any legitimate credentials. [95]

Changes in present day public library practices and representations, on the other hand, appear to be clearly tied to new forms of urban life. Libraries are nowadays visited by new types of readers, from homeless to unemployed yet qualified persons, whether still young or middle-aged, immigrants, persons living alone, retired readers as frequent visitors—a group now having enough education to allow them to become high-potential prospect users. It should be reminded that even children, those coveted users, are relatively recent visitors to a public library. [96]

Bearing in mind that representations structure behaviours and prepare responses to new situations, I may conclude, in a negatively constructed discourse, that a library without Internet would not be so public—or would not exist at all in some personal sceneries—, and positively, that it is so and may go on being so precisely because they provide Internet access and services. This reasoning is partially in line with the traditional images of a public library while it simultaneously lends new contours to them, delimiting new uses, and lends new meanings to representations renovated by Internet appropriations. [97]

Issuing from a single case study, these conclusions may be adequate for libraries with similar contexts. If not fully nor partially applicable, the conclusions may still contribute to an area of studies—social studies of public libraries—where little research has been published. In Portugal, three years after these research results were first published, very difficult financial constraints and budget cuts are being imposed on public libraries and public services in general, ICT services are being redesigned and re-packaged, and public library policies are being challenged. The central theme for this research should be revisited and redesigned to ascertain for significant ongoing or foreseeable changes in representations of the public library and their association with recent technological developments. [98]

My doctoral research project was supported by the FCT, Ministry of Science, Portugal, and the POPH/FSE.

|

|

|

Aabø, Svanhild; Audunson, Ragnar & Vårheim, Andreas (2010). How do public libraries function as meeting places? Library & Information Science Research, 32(1), 16-26.

American Library Association (2010). New survey shows U.S. public libraries in financial jeopardy: Cuts reduce hours, staffing at thousands of libraries as patron demand escalates. Media, http://www.ala.org/ala/newspresscenter/news/pressreleases2010/january2010/trendstudy_ors.cfm [Date of Access: January 25, 2010].

Audunson, Ragnar (2005). The public library as a meeting-place in a multicultural and digital context: The necessity of low-intensive meeting-places. Journal of Documentation, 61(3), 429-441.

Audunson, Ragnar; Vårheim, Andreas; Aabø, Svanhild & Holm, Erling Dokk (2007). Public libraries, social capital, and low intensive meeting places. Information Research, 12(4), http://informationr.net/ir/12-4/colis/colis20.html [Date of Access: January, 7 2010].

Bakardjieva, Maria (2003). Virtual togetherness: An everyday-life perspective. Media, Culture and Society, 25, 291-313.

Bertot, John Carlo; Jaeger, Paul T.; McClure, Charles R.; Wright, Carla B. & Jensen, Elise (2009). Public libraries and the Internet 2008-2009: Issues, implications, and challenges. First Monday, 14(11), http://firstmonday.org/htbin/cgiwrap/bin/ojs/index.php/fm/rt/printerFriendly/2700/2351 [Date of Access: April 22, 2010].

Boughey, Alan (2000). Implementing the "new library": The people's network' and the management of change. Aslib Proceedings, 52(4), 143-149.

Bourdieu, Pierre & Darbel, Alain (1966). L'amour de l'art: les musées et leur public. Paris: Les Éditions de Minuit.

Bruce, Harry (1999). Perceptions of the Internet: What people think when they search the Internet for information. Internet Research: Electronic Networking Applications and Policy, 9(3), 187-199.

Bull, Michael (2006). Investigating the culture of mobile listening: From Walkman to iPod. In Michael Bull; Kenton O'Hara & Barry Brown (Eds.), Consuming music together: Social and collaborative aspects of music consumption technologies (pp.131-149). Dordrecht: Springer.

Burawoy, Michael (1998). The extended case method. Sociological Theory, 16(1), 4-33, http://cue.berkeley.edu/ecm.pdf [Date of Access: April 11 2009].

Calhoun, Craig (2005). Rethinking the public sphere. Brooklyn: Social Science Research Council, http://www.ssrc.org/calhoun/wp-content/uploads/2008/08/rethinking_the_public_sphere_05_speech.pdf [Date of Access: April 11, 2009].

Cavanagh, Allison (2007). Sociology in the age of the Internet. Maidenhead: McGraw-Hill. International.

Certeau, Michel de (1984). The practice of everyday life. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

Curry, Ann (2002). What are public library customers viewing on the Internet? An analysis of Burnaby transaction logs. Report submitted to Industry Canada, School of Library and Archival Studies, University of British Columbia, Vancouver, http://tinyurl.com/8v7qc [Date of Access: April 11, 2009].

Eder, Donna & Fingerson, Laura (2002). Interviewing children and adolescents. In Jaber F. Gubrium & James A. Holstein, (Eds.), Handbook of interview research: Context and method (pp.181-201). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Feenberg, Andrew (1992). Subversive rationalization: Technology, power and democracy. Inquiry, 35(3-4), http://www.sfu.ca/~andrewf/Subinq.htm [Date of Access: April 2, 2010.]

Feenberg, Andrew (2002). Transforming technology: A critical theory revisited. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Fernandes, Luís (2003). A imagem predatória da cidade. In Graça Índias Cordeiro, Luís Vicente Baptista & António Firmino da Costa (Eds.), Etnografias urbanas (pp.53-62). Oeiras: Celta.

Fisher, Karen E.; Saxton, Matthew L.; Edwards, Phillip M. & Mai, Jens-Erik (2007). Seattle public library as place: Reconceptualizing space, community, and information at the Central Library. In John E. Buschman & Gloria J. Leckie (Eds.), The library as place (pp.135-160). Westport, CT: Libraries Unlimited.

Fortuna, Carlos; Antunes, Lina; Lopes, João Teixeira; Cruz, Sofia Alexandra; Fontes, Fernando; Monteiro, Ana; Aleixo, André & Pinto, Rui Pedro (1999). Sobre a leitura. Lisboa: IPLB, Observatório das Actividades Culturais.

Given, Lisa M. & Leckie, Gloria J. (2003). "Sweeping" the library: Mapping the social activity space of the public library 1. Library & Information Science Research, 25, 365-385.

Haraway, Donna (1988). Situated knowledges: The science question in feminism and the privilege of partial perspective. Feminist Studies, 14(3), 575-599.

Hardy, Gary & Johanson, Graeme (2003). Characteristics and choices of public access Internet users in Victorian public libraries. Online Information Review, 27(5), 344–358, http://www.emeraldinsight.com/10.1108/14684520310502306 [Date of Access: December 23, 2012].

Hédon, Guy (1997). L'évolution des utilisateurs d'Internet en bibliothèque: la bibliothèque de Grand'Place à Grenoble. Bulletin des Bibliothèques de France, 44(5), 40-45, http://bbf.enssib.fr/consulter/bbf-1999-05-0040-006 [Date of Access: December 30, 2009].

Heins, Marjorie; Cho, Christina & Feldman, Ariel (2006). Internet filters: A public policy report (2nd ed.). New York: Brennan Center for Justice at NYU School of Law, http://www.fepproject.org/policyreports/filters2.pdf [Date of Access: December 30, 2009].

Høyland, Britt (2001). Embodiment in cyberspace: How we conceptualise the Internet: A cognitive linguistic approach. Bergen: The University of Bergen, https://bora.uib.no/handle/1956/1733?language=no [Date of Access: December 30, 2009].

Jodelet, Denise (1984). Représentation sociale: phénomèmes, concept et théorie. In Serge D. Moscovici (Ed.), Psychologie sociale (pp.357-389). Paris: Presses Universitaires de France.

Klainbaum, Daniel (2006). Place and digital media. Masters thesis, Georgia Institute of Technology, Atlanta, http://hdl.handle.net/1853/10554 [Date of Access: December 30, 2009.]

Kvale, Steinar (1996). Interviews: An introduction to qualitative research interviewing. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Laidler, John (2008). Library use rises as economy falls. The Boston Globe, October 16, http://www.boston.com/news/local/articles/2008/10/16/library_use_rises_as_economy_falls/ [Date of Access: December 30, 2009].

Leckie, Gloria J. (2004). Three perspectives on libraries as public space. Feliciter, 6, 223-236.

Leckie, Gloria J. & Hopkins, Jeffrey (2002). The public place of central libraries: Findings from Toronto and Vancouver. Library Quarterly, 72(5), 326-372, http://polaris.gseis.ucla.du/ewhitmir/leckieandhopkins.pdf [Date of Access: April 2, 2010].

Lefèbvre, Henri (1991 [1974]). The production of space. Oxford: Blackwell.

Lizdas, William J. (2009). Libraries' many benefits rediscovered in hard economic times. JSOnline, January 21, http://www.jsonline.com/news/38082709.html [Date of Access: December 30, 2009].

Minow, Mary (1997). Filters and the public library: A legal and policy analysis. First Monday, 2(12), http://www.firstmonday.org/issues/issue2_12/minow/index.html [Date of Access: December 30, 2009].

Oblander, Terry (2008). Economy gets people out of the house, into libraries. The Houston Chronicle, August 2, http://www.chron.com/disp/story.mpl/nation/5920609.html [Date of Access: January 25, 2009].

Seale, Clive (2004). Researching society and culture (2nd ed.). London: Sage.

Sequeiros, Paula (2004). Pasando el tiempo en la Net: Apropiaciones juveniles de la Red en el espacio de una biblioteca pública. Masters thesis,Universitat Oberta de Catalunya, Barcelona, http://eprints.rclis.org/6823/ [Date of Access: October 7, 2013].

Sequeiros, Paula (2007). Filtros na Internet e conteúdos disponíveis nas bibliotecas públicas: Entre a abertura e a censura. In João Teixeira Lopes (Ed.) Práticas de dinamização da leitura (pp.16-26). Porto: Sete Pés, http://eprints.rclis.org/9089/1/FiltrosELIS.pdf [Date of Access: October 7, 2013].

Sequeiros, Paula (2010). Ler uma biblioteca nas inscrições de leitores, espaço e internet: Usos e representações de biblioteca pública. Doctorship thesis, Faculdade de Letras da Universidade do Porto, http://hdl.handle.net/10760/15815 [Date of Access: October 7, 2013].

Sequeiros, Paula (2011). The social weaving of a reading atmosphere. Journal of Librarianship and Information Science, 43(4), 261-270.

Sequeiros, Paula (2013). Reading in public libraries: Space, reading activities and user profiles. Qualitative Sociology Review, IX(3), 220-240, http://www.qualitativesociologyreview.org/ENG/Volume26/QSR_9_3_Sequeiros.pdf [Date of Access: October 7, 2013].

Tonkiss, Fran (2005). Space, the city and social theory: Social relations and urban forms. Cambridge, MA: Polity.

Paula SEQUEIROS is a post-doc researcher with the Centre for Social Studies, University of Coimbra and a researcher with the Institute of Sociology, University of Porto. Her main interests are the sociology of public libraries and reading. She has a degree in history, a postgraduate degree in documentary sciences, a Master's Degree in information society and knowledge and a Doctorship in sociology. She was a member of the Executive Board of E-LIS, an Open Access Archive in Library and Information Sciences.

Contact:

Paula Sequeiros

Centro de Estudos Sociais

Colégio de S. Jerónimo, Apº 3087

3000-995 Coimbra

Portugal

Tel.: 351 239 855 570

Fax: 351 239 855 589

E-mail: paulasequeiros@ces.uc.pt

URL: http://www.ces.uc.pt/investigadores/index.php?action=bio&id_investigador=672

Sequeiros, Paula (2013). Public Library Representations and Internet Appropriations [70 paragraphs]. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung / Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 15(1), Art. 14,

http://nbn-resolving.de/urn:nbn:de:0114-fqs1401141.