Volume 16, No. 3, Art. 15 – September 2015

Refugee Youth and Migration: Using Arts-Informed Research to Understand Changes in Their Roles and Responsibilities

Sepali Guruge, Michaela Hynie, Yogendra Shakya, Arzo Akbari,

Sheila Htoo & Stella Abiyo

Abstract: This article presents the findings from a community-based qualitative study that utilized an arts-informed method to understand the changes in refugee youth's roles and responsibilities in the family within the (re)settlement context in Canada. The study involved 57 newcomer youths from Afghan, Karen, or Sudanese communities in Toronto, who had come to Canada as refugees. The data collection method embedded a drawing activity within focus group discussions. We present these drawings, as well as explanations and discussions to capture the complexities of their experiences. The data analysis involved 1. reflective dialogue between each participant and her/his own drawing; 2. group dialogue, reflection, and elaboration on meanings in the drawings; and 3. the research team's reflective dialogue. The findings revealed that the youths' roles and responsibilities have both changed and increased following migration, often involving interpretation and translation, and providing financial and emotional support to their family members, in addition to engaging in household chores and educational pursuits. Use of drawings as a data generation method enriched the findings of focus group discussions, and vice versa in a number of ways. We also present implications for future research involving arts-informed methods.

Key words: across group analysis; Afghan youth; arts-informed research; arts-informed method; Canada; drawings; immigration; multilevel data analysis; Karen youth; migration; qualitative research; refugee youth; roles and responsibilities; Sudanese youth; within group analysis

Table of Contents

1. Introduction

2. Background

3. Study Purpose

4. The Communities of Focus

4.1 The Afghan community

4.2 The Karen community

4.3 The Sudanese community

5. Method

6. Results

6.1 Individual level analysis and interpretation

6.2 Within group analysis and interpretation

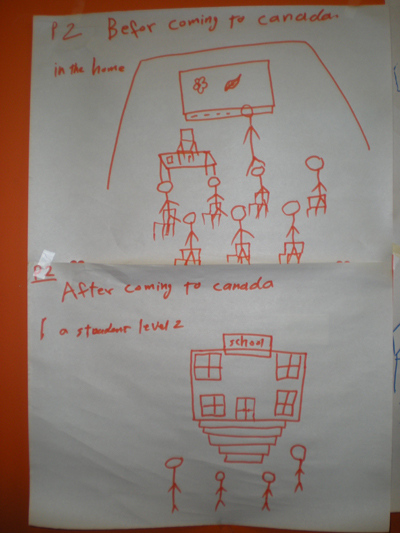

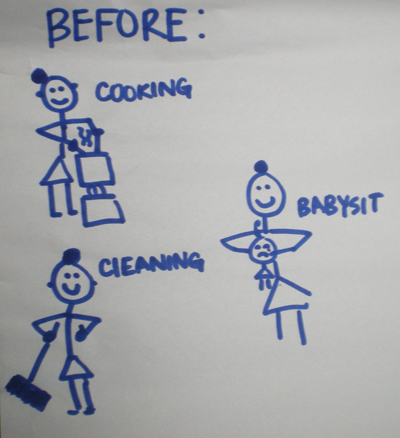

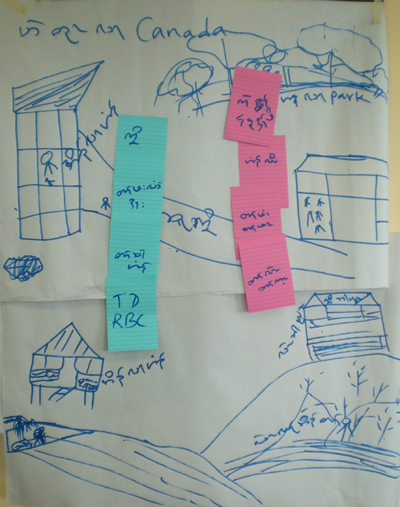

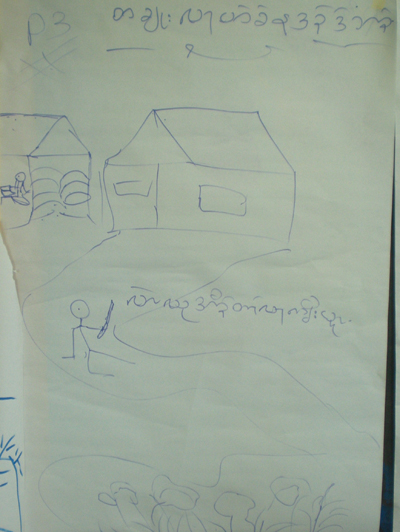

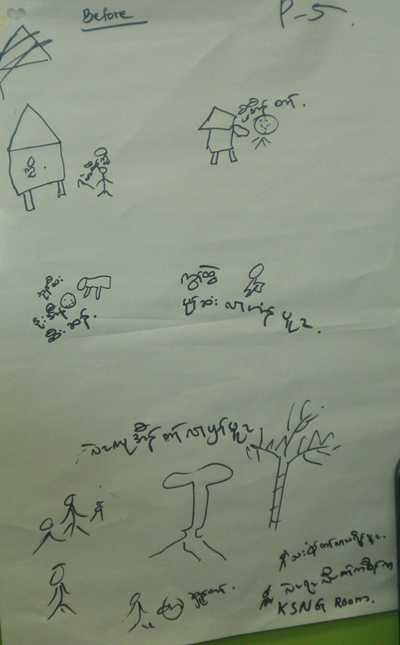

6.3 Across group analysis

7. Discussion

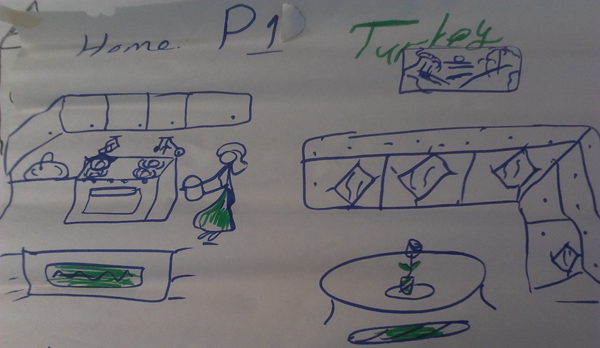

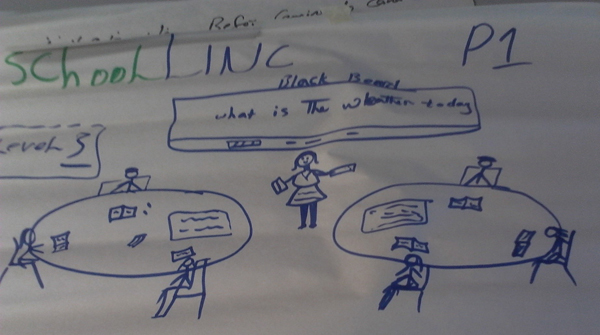

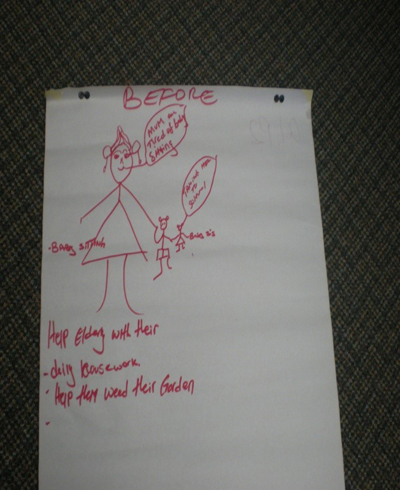

8. Lessons Learned and Final Thoughts

Most of the literature on refugees has focused on forced migration and trauma they have experienced in pre-migration contexts or the persistent challenges they face in post-migration contexts, with a large proportion of the literature documenting impacts of pre- and post-migration experiences on their mental health, using various psychometric instruments (e.g., HALCÓN et al., 2004; MARSHALL, SCHELL, ELLIOTT, BERTHOLD & CHUN, 2005; MONTGOMERY, 2011). While generating rich evidence about forced migration, traumatic experiences, health and mental health of refugees, studies that rely heavily on conventional research methods, standardized psychometric instruments and textual expressions alone, and data collected in dominant languages alone may be failing to capture the everyday nuances and complexities of migration and health of refugees. Moreover, these studies and research methods may serve to reinforce stereotypical perceptions of refugees as helpless victims that need to be studied, uplifted, and cured. [1]

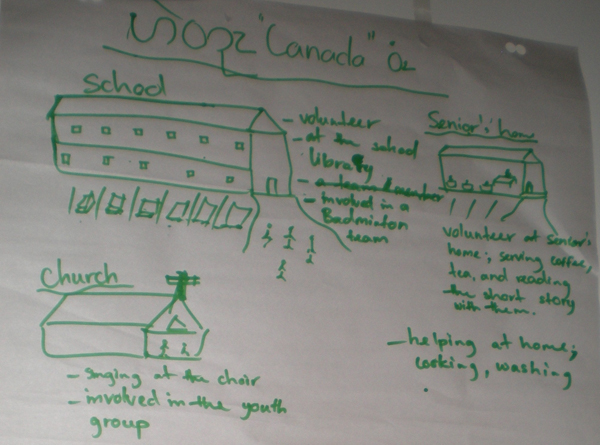

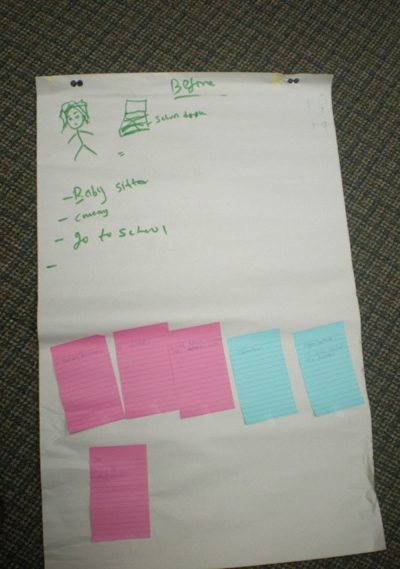

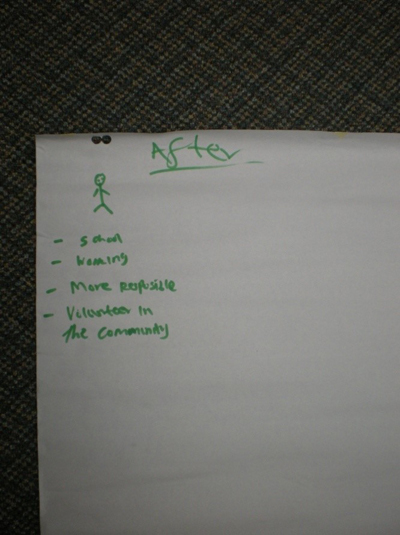

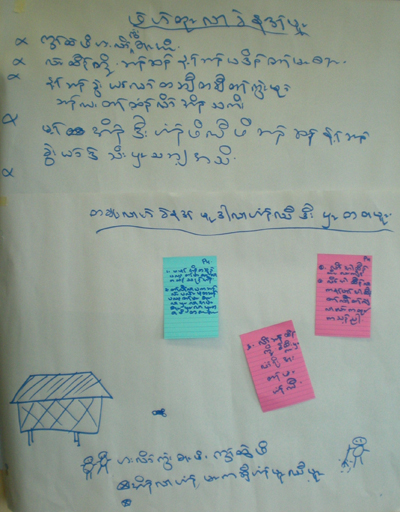

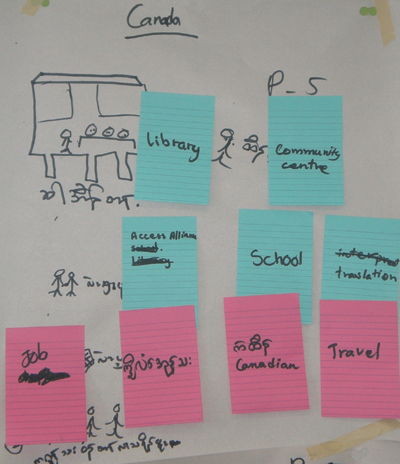

More recently, however, there has been an interest in understanding refugee migration experiences using new methodologies that allow for diverse forms of expressions beyond textual and linguistic modes (e.g., KHAWAJA, LINOS & El-ROUEIHEB, 2007). Arts-informed research, in general, has gained attention as a valid approach to enhancing understanding of and communicating the diversity and complexity of human experiences through alternative processes and forms of inquiry (BALL & GILLIGAN, 2010; COLE & KNOWLES, 2011). Arts-informed research can be particularly useful in research with people facing linguistic and/or communication barriers because it offers creative and aesthetic forms of communication avenues that can complement verbal and/or written communication (PAUWELS, 2010; PROSSER, 2011; ROSE, 2012). Researchers employing arts-informed visual methods (e.g., drawings, photography, film) have highlighted how these non-linguistic creative methods can open opportunities to capture other forms of knowledge and expressions including tacit knowledge, felt/emotional, and symbolic expressions (BAGNOLI, 2009; ESTRELLA & FORINASH, 2007) in multidimensional ways. Many visual arts-informed methods have the added benefit of geospatial representation of experiences and perspectives (e.g., through drawing or photo of participants home), which, in turn, has its own intrinsic narrative and analytical value that may not be captured by textual expressions alone (BAGNOLI, 2009; ESTRELLA & FORINASH, 2007; RODRIGUEZ-JIMENEZ & GIFFORD, 2010). Proponents of arts-informed research methods also point to how, compared to text or spoken language alone, creative/visual expressions can evoke stronger, quicker and often more empathetic responses from fellow participants (in focus group discussion sessions during data collection) and other stakeholders (BAGNOLI, 2009; FREY & CROSS, 2011; RODRIGUEZ-JIMENEZ & GIFFORD, 2010). It may be particularly useful in cross-cultural contexts; it has long been recognized that even with careful translation, ensuring that concepts are understood the same way across cultures is challenging (BRISLIN, 1983; LEONG, LEUNG & CHEUNG, 2010). Triangulating by utilizing the emotional and cognitive ways of knowing that arts-informed research provides can make the findings "more culturally exact and explicit" (HUSS, 2007, p. 962). For these reasons and more, a growing number of researchers working with marginalized communities are using arts-informed methods. In this article, we report the processes and the findings of an arts-informed research project on the pre- and post-migration roles and responsibilities of Afghan, Karen, and Sudanese refugee youth that elicited their own accounts and interpretation of their experiences, challenges, and strengths in these areas. We conclude with lessons learned and recommendations for more effective and empowering utilization of arts-informed methods when working with vulnerable refugee youths. [2]

Approximately 25,000-35,000 refugees arrive in Canada every year; of these, about 20% are youth aged 15-24 years (CIC, 2010, 2014). Compared to those who arrive as economic immigrants, refugees arriving in Canada generally have less education and limited fluency in English and French (ibid.). They often have less time to plan their departure and arrival and may experience more challenges (re)settling in their new country (KHANLOU & GURUGE, 2008). The challenges they face are shaped by the context within which they leave their country of origin, their border-crossing experiences, and the post-migration supports and services available to them in the new country (GURUGE & BUTT, 2015; HYNIE, GURUGE & SHAKYA, 2012; SHAKYA et al., 2014). They may have escaped political instability or war and/or experienced family separation or death, and have limited access to food, health care, education, and employment in the pre-migration context (UNHCR, 2013). Girls, women, and the youth are particularly vulnerable to sexual exploitation and trafficking during displacement and/or border crossing (ibid.). Even in the best of circumstances, differences in ethnocultural, linguistic, social, economic, and political contexts between the country of origin and the new country can make the (re)settlement experience challenging. Refugee youth also face considerable challenges in the post-migration context including educational challenges, discrimination, racism, and limited access to and gaps in refugee-specific services (UNHCR, 2013). [3]

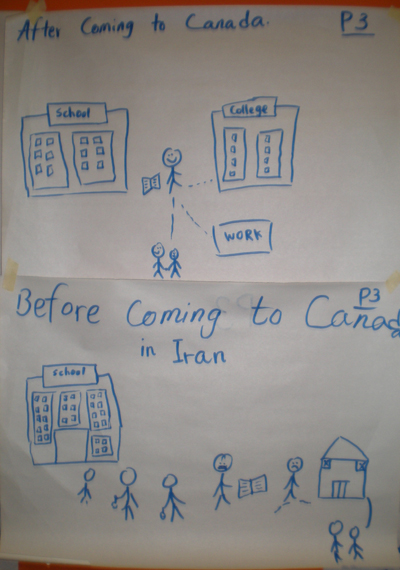

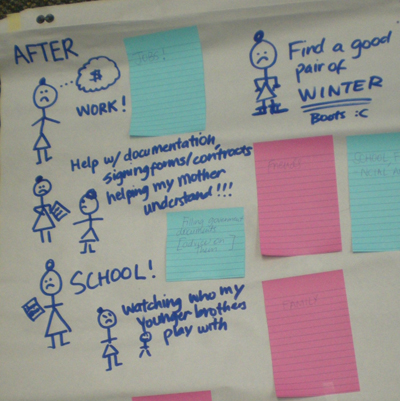

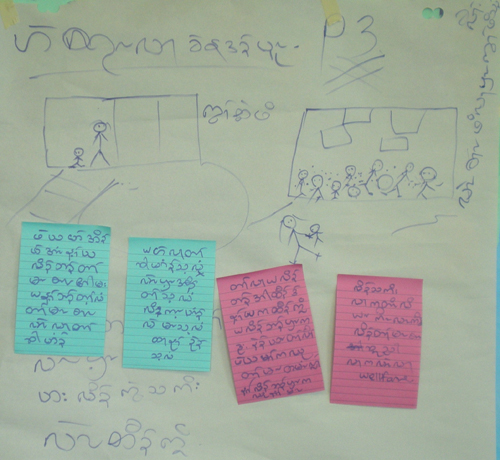

All youths, especially teenagers, experience considerable (biological, social, economic, educational, and employment) changes as they move into adulthood, and their roles and responsibilities often change over time (EAST, 2010; FULIGNI & PEDERSON, 2002; TELZER & FULIGNI, 2009). However, youths who are refugees or immigrants in a new country may face additional or sudden changes that go beyond "normal growing up," including rapid changes in their roles and responsibilities at home and/or in the community, often without the usual support of family and friends (GLICK, 2010; HYNIE et al., 2012; MORALES & HANSON, 2005). Even when they live with parents and family members in the new country, the acculturation gap between the generations might lead to changes in their roles and responsibilities at home. For example, children and the youth, in general, typically learn the new language more easily and quickly than adults (BIRMAN, 2006) and may become the spokesperson for the family or a primary breadwinner, thus taking on roles normally held by parents (OZNOBISHIN & KURMAN, 2009; TRICKETT & JONES, 2007; WALSH, SHULMAN, BAR-ON & TSUR, 2006). Helping their families (and communities) in such ways can be beneficial to the youth, increasing their sense of self-worth, self-efficacy, competency (ORELLANA, 2001), and feelings of independence and maturity (FULIGNI & PEDERSON, 2002; McQUILLAN & TSE, 1995). However, taking on these extra roles and responsibilities can also be daunting and negatively affect their health as well as achievement of their own life goals. [4]

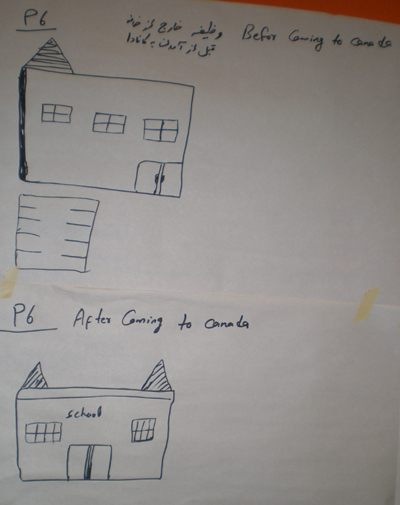

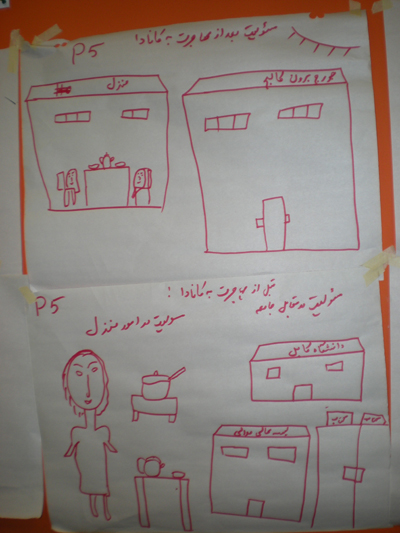

The purpose of this study was to understand the roles and responsibilities refugee youth from Afghan, Karen, and Sudanese communities take on in the post-migration context in Canada. In particular, we wanted to understand their pre-migration roles and responsibilities and how these have changed since their arrival in Canada. [5]

We selected Afghanistan, Burma, and Sudan for this study, as they have been among the top source countries for sponsored Convention refugees1) to Canada since 2006. They have undergone protracted wars, resulting in many individuals being killed or displaced. Yet, their experiences have been missing from the Canadian health research context. [6]

In recent history, Afghanistan has experienced instability, war, and destruction beginning with the Soviet invasion in 1979. Since then, the country has undergone civil wars, proxy wars from outside the country, and most recently the invasion and occupation by the United States and its allies in 2001 (TOBER, 2007). Many sought refuge in neighboring countries such as Iran and Pakistan (ibid.), while others continued their escape into Canada, Europe, and the United States. Although more than five million Afghans have returned to the country since 2002, an estimated 2.7 million Afghan refugees still live outside the country (UNHCR, 2011). Afghanistan has been a key source country for refugees to Canada since the mid-1990s with approximately 48,000 currently residing in Canada, half of whom are settled in Toronto (STATISTICS CANADA, 2006). [7]

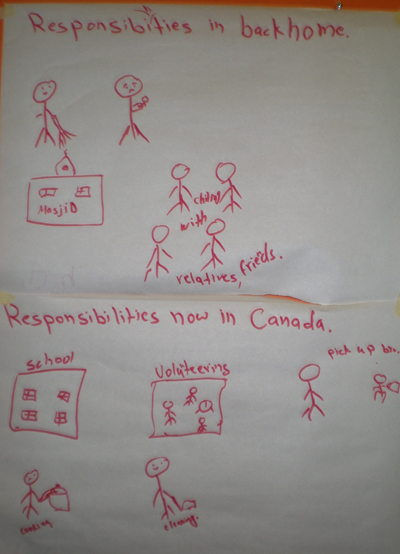

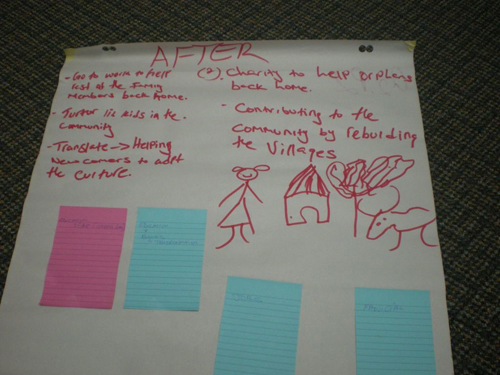

After Burma's independence in 1948, the Burmese who came to power increasingly persecuted the minority ethnic groups in the country. Karen is the largest ethnic minority group. According to KAREN HUMAN RIGHTS GROUP (2011a), thousands of Karen civilians were forced to do hard labor (e.g., building roads, carrying military equipment to battlefields), shot at, injured, raped, tortured, and killed and that entire Karen villages were burnt down, leaving families homeless and without any belongings, farms/fields, livestock, and friends and family. Many Karens were forced to hide in jungles for months and even years without food, medicine, and other basic needs (KAREN HUMAN RIGHTS GROUP, 2011b). Approximately 160,000 Karen refugees currently live in nine refugee camps along the Thai-Burmese border; many have lived in these camps for more than 20 years (KAREN REFUGEE COMMITTEE, 2012). Some of the camps (e.g., Mae La Oon, with over 40,000 refugees) are unsuitable and unsafe for human settlement. Since 2006, approximately 5,000 Karen refugees have resettled in Canada; of these, 500-800 live in Toronto. No Census Canada statistics are available for this community. [8]

Since 1955, Sudan has undergone two civil wars and multiple armed conflicts. An estimated 640,000 Sudanese are refugees worldwide (USCR, 2007). Between 2000 and 2009, approximately 13,000 Sudanese arrived in Canada, of which approximately 3,000 (25%) settled in Toronto (THE MOSAIC INSTITUTE, 2009). The Sudanese community in Canada is composed of many ethnic groups, including Arab, Dinka, Beja, Nuer, and Nuba, among others (LESCH, 1998). This community is also religiously diverse: North Sudanese are predominantly Muslim, and South Sudanese are predominately Christian. Sudanese refugees living in Canada are also linguistically diverse; they may speak Arabic and/or African languages such as Juba, Dinka, and Nuer. Many Sudanese in Canada have lived in refugee camps or have previously been refugees in neighboring African countries and/or endured multiple displacements within Sudan, prior to (re)settling in Canada. [9]

We used an arts-informed research method, which is a qualitative approach influenced by, but not based on, the arts (COLE & KNOWLES, 2011). The main purposes of arts-informed research are to generate data using alternate (to conventional) ways and to reach a wider audience by making the findings more accessible (COLE & KNOWLES, 2011; PAUWELS, 2010; PROSSER, 2011; ROSE, 2012). COLE and KNOWLES (2011) further emphasized that the "knowledge advanced in arts-informed research is generative rather than propositional and based on assumptions that reflect the multidimensional, complex, dynamic, inter-subjective and contextual nature of human experience" (p.124). [10]

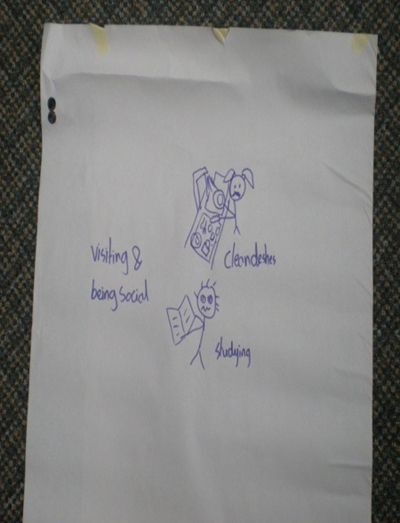

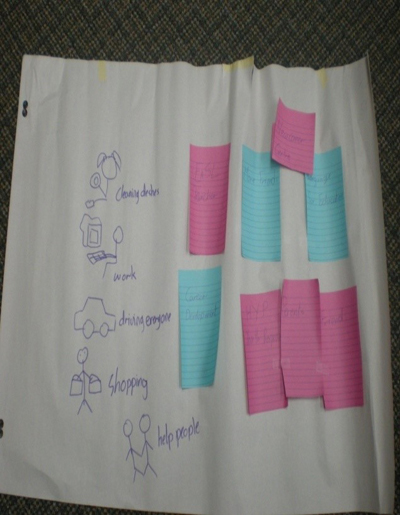

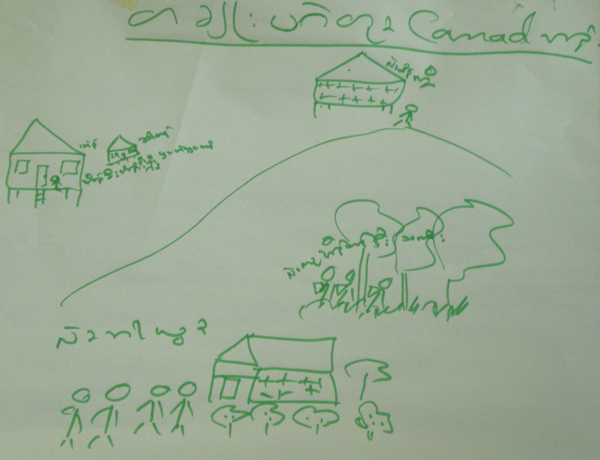

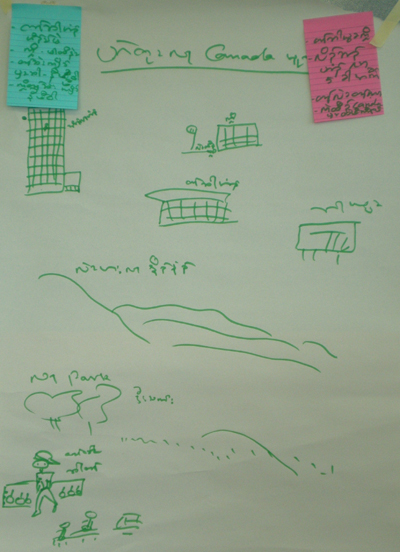

Following ethics approval from the appropriate agencies, we established a multidisciplinary research team of academic and community partners and eight refugee youth peer researchers from the three communities. In line with community-based participatory research framework (KREIGER, 2002; MINKLER & WALLERSTEIN, 2003), peer researchers received three months of research training and were actively involved in paid capacity in all phases of the study, including research design, data collection, data analysis, and writing. Three of the lead peer researchers were re-engaged with new funding to collaborate as co-authors for this article. [11]

Altogether, 57 participants were recruited using a number of strategies: distribution of flyers to community centers and student associations, presentations at schools with high numbers of newcomer youth students, Facebook invitations, announcements at youth-focused events, word of mouth, and face-to-face or telephone contacts with those who did not have computer access. Potential participants were youth 16 to 24 years old who self-identified as belonging to the Afghan, Karen, or Sudanese communities, and who had come to Canada within the last five years as government-assisted refugees, privately sponsored refugees, or through the in-Canada refugee claimant process. See Table 1 for a summary of the demographic characteristics of the participants.

|

Group |

N |

Mean years in Canada |

Status upon arrival: S, G, W, R2) |

Living with family |

Understand English "very well" |

Employed |

Student |

|

|

Afghan |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

16-19 F |

7 |

2.4 |

4/3/0/0 |

7 |

3 |

2 |

5 |

5/0/1/0 |

|

16-19 M |

5 |

1.0 |

1/2/0/2 |

3 |

4 |

0 |

5 |

5/0/0/0 |

|

20-24 F |

6 |

2.5 |

3/2/0/0 |

5 |

3 |

0 |

3 |

0/0/3/1 |

|

20-24 M |

6 |

0.5 |

0/2/0/1 |

2 |

1 |

1 |

4 |

1/1/3/1 |

|

Karen |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

16-19 F |

6 |

2.5 |

1/5/0/0 |

5 |

0 |

2 |

6 |

6/0/0/0 |

|

16-19 M |

7 |

1.8 |

0/7/0/0 |

6 |

0 |

3 |

4 |

5/0/1/0 |

|

20-24 F |

5 |

2.0 |

0/4/0/1 |

4 |

0 |

2 |

5 |

2/0/3/0 |

|

20-24 M |

5 |

1.2 |

0/4/0/1 |

4 |

0 |

3 |

2 |

0/0/4/0 |

|

Sudanese |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

20-24 F |

4 |

2.3 |

1/2/0/1 |

4 |

3 |

2 |

4 |

0/3/0/1 |

|

20-24 M |

6 |

2.8 |

0/0/3/1 |

2 |

4 |

3 |

6 |

0/6/0/0 |

Table 1: Demographic characteristics of the participants [12]

We planned to conduct four gender-specific and age-specific (16-19 and 20-24 years) focus groups per community, but due to recruitment challenges, we were only able to conduct 10 of the 12 focus groups; no focus groups were conducted with younger Sudanese (female and male) youth. Each focus group included 4-7 participants, facilitated by peer researchers from the same community. The discussions were conducted in Dari with Afghan participants, Sgaw with Karen participants, and English with Sudanese youth. [13]

Each participant was invited to draw two pictures: one depicting pre-migration roles and responsibilities, and the second depicting post-migration roles and responsibilities. The participants were given flip chart paper and color pens, and 10 to 15 minutes to complete the activity. The drawings were then displayed on the walls around the room. Each participant was asked to briefly present her/his drawing to the group. Once all participants had their individual turns reflecting on and explaining their drawings to the group, the floor was open to all for reflection and clarification of the drawings within the group. This was followed by a semi-structured focus group discussion of roles and responsibilities in which participants were encouraged to refer to their drawings wherever appropriate. In a later part of the focus group discussion, the youths were also asked to list the services they had used and the services they needed on sticky notes, which were added to the flip chart drawings. [14]

Having participants engage in the drawing activity met several of our methodological goals: 1. It was a fun activity that helped make participants feel at ease; 2. it allowed participants to produce something tangible and feel a sense of ownership during their engagement in the data collection process; and 3. the drawings also provided a visual reference point (a map) for participants to express themselves and to compare and contrast their ideas and experiences with other participants and direct the overall discussion. [15]

The data analysis and interpretation was based on the participants' own explanations rather than on external frameworks or theories, and involved the following levels of analysis: 1. the reflective dialogue between each participant and her/his own drawing (that is, individual level analysis and interpretation); 2. the group dialogue, reflecting and elaborating on meanings in the drawings across the group (that is, within group analysis and interpretation); 3. the reflections of the peer (refugee youth) researchers from the same ethnocultural backgrounds in response to the comments and questions from the rest of the research team about the findings from individual level and within group (that is, pertaining to 1 and 2); and 4. the research team's reflections about the findings across the three communities (that is, across group analysis and interpretation). To examine implications of direct references to drawings in focus group discussions, the research team compiled and closely analyzed coded data summary of all references to drawings. For easier navigation through different levels of analysis, we have provided the reflections of the peer (refugee youth) researchers immediately alongside 1 and 2. [16]

This is a unique and novel approach to data analysis within arts-informed approach. In line with arts-informed research (COLE & KNOWLES, 2011; KNOWLES & COLE, 2008; ROSE, 2012), the findings are presented with some ambiguity to involve the reader/audience in an active process to allow for multiple interpretations and responses. The article focuses on the female participants from the three communities. [17]

6.1 Individual level analysis and interpretation

First, we present drawings and the "texts" that demonstrate the reflective dialogue between the individual and her own drawing, depicting the changes in individual roles and responsibilities before and after migration to Canada. Alongside, we have presented a reflection from a peer researcher from the same community of each participant's drawings. [18]

To demonstrate the reflective dialogue between each participant and her own drawing(s), we have provided here drawings and comments from two participants (one Afghan and one Karen) from the 16-19 age group. [19]

The first drawing and the reflections are from Participant 3, in the Afghan focus group:

Picture 1: Before and after drawing by Participant 3 in the Afghan female 16-19 years focus group

P3: "In Afghanistan I didn't work, for example, I did painting, study and ... I watered the garden, helped my father and mother with some other jobs. In Canada we do shopping, cooking, cleaning the house, and ironing. In school I am with my friends and study there." [20]

Reflections of the Afghan peer (youth) researcher (Arzo)

The participant's own explanation of the above drawing seems to indicate that her responsibilities at home have changed after coming to Canada. The changes can be felt in the fullness of the activities shown in the "after" image. While the "before" image depicts more recreational activities such as drawing/painting and watering plants, the "after" image is more task-focused involving shopping, cooking, cleaning, ironing, and studying. Also, there is a sense of involvement of more technology (iron, TV, computer) in the "after" image. The "after" drawing also shows the importance of friendships. The importance of education as a constant can be seen in both the before and after contexts. [21]

Next we have presented drawings and reflections from Participant 3 in the Karen focus group:

Picture 2: Before drawing by Participant 3 in the Karen female 16-19 years focus group

Picture 3: After drawing by Participant 3 in the Afghan female 16-19 years focus group

P3: "Before I came to Canada, I went to school and read in the evening. Sometimes I washed clothes and cleaned the house. After coming to Canada, on a regular basis, I go to school, and do volunteer work in the school library and at a senior home. I also cook rice and clean things. In the community, I sing in the church choir, and take part in youth groups." [22]

Reflections of the Karen peer (youth) researcher (Sheila)

In the "before" picture, only the images of the school and the home can be seen. In the "after" drawing, images include a school, a nursing home and a church. In addition, the participant has listed her responsibilities at each of these places. For example, she wrote that she played badminton as part of a team at the school. The two images differ in a number of other ways. First, in the after drawing, the buildings are bigger, the people are smaller, and the space is more crowded. The details of the built environment can also be seen: for example, the school has two floors and a big parking lot. This participant and her family were sponsored by the church; the importance of which may be shown by the image of a church. The participant also volunteers at the church and sings in the choir. The after drawing perhaps is indicative of shifting of goals. For example, there is no image of her home which, perhaps, indicates reduced importance of activities at home in the post-migration context in comparison to educational and employment pursuits. The image of the nursing home where she volunteers is indicative of her present interest in becoming a nurse. [23]

6.2 Within group analysis and interpretation

This section presents the reflective dialogue within each focus group that captures the participants' individual reflections as well as group-based discussion about the drawings (involving clarifications and questions about and comparisons between each other's drawings, which helped identify similarities and differences across individuals within the group from the same community). For this purpose, we have provided drawings from the 20-24 year age groups from all three communities. [24]

6.2.1 Afghan female 20-24 group

Picture 4: Before drawing by Participant 1 in the Afghan female 20-24 years focus group

Picture 5: After drawing by Participant 1 in the Afghan female 20-24 years focus group

P1: "Before coming to Canada, we were in Turkey, Istanbul, and my responsibility was helping my mother at home. Although my cooking was (is) not good, I did a little; I drew this picture a little bit more big (laughing), I cooked because no one could tell me that I didn't do anything! (Laughing). After I came to Canada, I am going to school, and have no other specific responsibilities. Sometimes I do some volunteer jobs, that's it."

Picture 6: Before and after drawing by Participant 4 in the Afghan female 20-24 years focus group

P4: "My responsibilities in Afghanistan were just cleaning the house, looking after my younger siblings, going to the mosque, and meeting my relatives and friends. I didn't have other responsibilities. But when I came to Canada, I started going to school, because in Afghanistan, in our homeland, since the situation was bad we couldn't go to school. I do some volunteer jobs right now and pick up my little brother from school. Also I do some cooking and cleaning."

Picture 7: Before and after drawing by Participant 2 in the Afghan female 20-24 years focus group

P2: "Here is the picture in Afghanistan, before coming to Canada, I was a teacher there, and I had 60 students either in or out of house. I taught dressmaking as well as flower making. Besides, I taught three-dimensional drawings, but now after coming to Canada, I am a student myself!"

Picture 8: Before and after drawing by Participant 3 in the Afghan female 20-24 years focus group

P3: "Before coming to Canada, I was going to school, I had finished grade 10, and I intended to finish grade 12, but I knew that once I finished grade 12, I wouldn't be allowed to go to school. Because in Iran, Afghans were not allowed to go to school. But after I came to Canada, I finished high school and I am going to college right now. I also got married and I can work. In Iran, I had to stay at home after finishing school. Most Afghan girls who are related to us got married either by force or because the schools were too expensive. No Afghan girl in our family had attended college or university, because they were not allowed."

Picture 9: Before and after drawing by Participant 6 in the Afghan female 20-24 years focus group

P6: "Before coming to Canada, we were living in Pakistan, and then we came here from Pakistan. I was busy with my school as well as working. When I finished school, I started working in an office. But the situation got worse and worse, both in terms of schooling and working. Then we had to leave there. Here, I also study and work now."

Picture 10: Before and after drawing by Participant 5 in the Afghan female 20-24 years focus group

P5: "Because I come from an open-minded family, I was allowed to study while I was in Afghanistan. I graduated from high school when I was very young, and then I entered Kabul University and studied for two years, but I couldn't finish it, because we came to Canada. My responsibility at home was cooking, cleaning, and some other jobs around the house. After coming to Canada, I am studying at a college and now it's my last year. I do some housekeeping as well." [25]

6.2.1.1 The group's own reflections of their roles and responsibilities based on their drawings

P6: "When I look at the drawings, I see that all are the same. Maybe in her opinion, someone stays at home and doesn't go to school and only does the housekeeping. And the others do two jobs at the same time. But if you really look at them, all are the same—going to school, taking care of family, and housekeeping are important."

P5: "I also think they are almost similar, because we are girls and [as such] have the same responsibilities; I mean housekeeping and going to school. I see all the [before] drawings are about home and school."

P1: "When I look at these pictures, I see that everybody went to school or was at home before coming to Canada. But after coming to Canada, they change their minds, because they want to have a different life here. They want to learn English, and they want to make progress and compensate for the lack and losses in their lives." [26]

6.2.1.2 Afghan (youth) peer researcher's (Arzo's) reflection of the drawings across participants in this group

In the Afghan group's drawings, the lack of home structure in the "before" image is striking. Since Afghanistan has undergone over 30 years of war, all of the Afghan youths, who attended the focus group, were either born in times of war or living in Iran and Pakistan as refugees. They are accustomed to moving from one "home" to another or being confined to basements during bombing. Similarly, the idea of school back home may mean going to a class in someone's home with a group of other students because school buildings may be unsafe or non-existent. In the before images, space is also shown as shared and communal. In the after image, services are confined to particular buildings and spaces. The individual drawings perhaps are indicative of the diversity of this seemingly homogenous group of participants (e.g., some had lived in Afghanistan while others had lived in Iran or Pakistan). Education appears prominent across drawings both before and after coming to Canada. [27]

6.2.2 Sudanese female 20-24 group

Picture 11a: Before drawing by Participant 4 in the Sudanese female 20-24 years focus group

Picture 11b: After drawing by Participant 4 in the Sudanese female 20-24 years focus group

P4: "This is before I came to Canada, I had to cook, clean, and baby-sit. But when I came to Canada I have to think about working to get money to help support me and my family. And also for school and I also have to help my mom with signing documentation because it is a lot and some stuff is confusing, so I have to help with that. I also have to focus on school and all the pressures that come with it, like fitting in and having the right clothes to wear. I also have to watch who my brother plays with, especially where we live is not the best environment so I have to make sure that my brother is hanging out with the right kids. And also, the weather is a huge concern and it changes like crazy. I have to think about buying new winter clothes."

Picture 12a: Before drawing by Participant 1 in the Sudanese female 20-24 years focus group

Picture 12b: After drawing by Participant 1 in the Sudanese female 20-24 years focus group

P1: "This is my picture before coming to Canada. I cook, babysit, clean, and go to school. After coming to Canada, I continue with school, work, do shopping, and have more responsibilities like volunteer and community work."

Picture 13a: Before drawing by Participant 2 in the Sudanese female 20-24 years focus group

Picture 13b: After drawing by Participant 2 in the Sudanese female 20-24 years focus group

P2: "These are my responsibilities before I came to Canada: babysitting, going to school, and helping elders in the community to weed their gardens and do their daily chores. And these are my responsibilities now in Canada, they are more than ever. People back home are looking to you because they think in Canada you have a lot of things to help them with. Here, you go to work to help your family members but still you have to send money to help people back home. I also contribute to the community by translating and helping newcomers to adapt to the new culture. And I do charity to help the old friends back home. I also contribute to the community by sending money to rebuild the villages that I worked on."

Picture 14a: Before drawing by Participant 3 in the Sudanese female 20-24 years focus group

Picture 14b: After drawing by Participant 3 in the Sudanese female 20-24 years focus group

P3: "Before I did not have a lot of responsibilities. Cleaning the house and studying was the big concern. When I come to Canada, the home responsibilities remained the same, other responsibilities are added. I have to work and support my family. I have to drive everyone because I am the only one with a license. I hate driving. I have to do grocery shopping every day, every two days. I hate that. And then helping people because I am also volunteering with newcomers. I believe that newcomers need somebody who is closer to their status to understand them. So I feel it is so important for me to do this. These are my responsibilities." [28]

6.2.2.1 The group's own reflections of their roles and responsibilities based on their drawings

P1: "Huge difference because back home you tend to rely on your parents ... don't have to think about your finances, just school work. But here you are not going to depend on your parents for everything because no matter how educated your parents are there are no good jobs here compared to how they used to work back home being the main source of income. Here they have to struggle on their own so we are not going to sit back and rely on them. So there is more responsibility here than ever compared to back home."

P2: "I am kind of surprised, like nobody cares what is going on back home. It seems (we think) more about ourselves and our responsibilities here, and we are not thinking about contributing to (those) back home."

P3: "There are a few, and they all got a lot of responsibilities after coming to Canada."

P4: "Like when I look at this drawing, it shows a lot of helping back home. Why didn't you help those back home when you were

there."

P2: "Okay the thing is when you are back home, you are a child and you are not expected to do more. You just go to school

and you rely on your parents. You can't work, there is no job when you are young so you just go to school and depend on your

parents. But now you are more grown and tend to look back on what is going on back there. Here you can work and there are

a lot of things you can do, little differences you can make back home. So, personally from where I come from, things might

have been different from where you guys came from. But from where I came from, I was born outside Sudan but from the pictures

and things I have seen there are lot of damages due to the war. A lot of villages need to be rebuilt ... schools, health care, it tends to be more pressure on us than ever. For the southerners we have a certain group we have to contribute to send money back home and build stuff."

P3: "For me, in my case, because we are still young, finding a job is easier for me, for us, as kids. For my parents they can't find jobs. In this way I feel responsible. They rely on us."

P4: "They don't think you have the capability to do something and also in terms of education. If you got an education back in Africa and you come here they don't respect it as much. They think that you don't know much. They just put low standards on what you should do. Also I think family ties is not as strong because there is so many stuff, so many responsibilities that you have in this country you tend to forget the old stuff. Like, you know, just chilling with your family and going out and all that."

P1: "Also, school wise you have more pressures. Usually back home the main thing is education. You have the same people with the same type of things. When you come here, you have pressure to fit in. You have to conform to a certain way to fit in so people can relate to you." [29]

6.2.2.2 Sudanese (youth) peer researcher's (Stella's) reflection of the drawings across participants in this group

The commonalities between the drawings and the participants' reflections on the drawings seem to suggest that there is a considerable difference and change in terms of the roles and responsibilities before and after coming to Canada. Also, from the drawing and in their own words there appears to be an urge to help people—in Canada or back home. The responsibilities seem to shift from self to others. Whereas they were dependent on their parents back home, in Canada they seem to take on a major responsibility in supporting their families financially—especially, given that their parents cannot find jobs. Except in one drawing, there are no home-like structures or any indication of environmental factors (such as trees), which is common across pictures and in the images before and after. For many Sudanese "home" does not exist; during times of war, home is just a structure made of sticks or tents that allows storage of some food and few belongings that most people had carried with them while they were fleeing from their original homes. The financial responsibility that they shoulder is a common concern. Education appears to be important across drawings because as refugees, Sudanese believe that the only way to better their lives is through education, even as the responsibilities increase in Canada. Another similarity is that while they all seem to maintain the same responsibilities at home (e.g., washing dishes, babysitting, and cooking), these do not seem to be reiterated in the after part. These responsibilities seem to be overshadowed by the fact that they have to take up newer and perhaps "more important" ones. [30]

6.2.3 Karen female 20-24 group

Picture 15: Before and after drawing by Participant 1 in the Karen female 20-24 years focus group

P1: "Before I came to Canada, I was a student. My daily work were, house cleaning, cooking early in the morning, going to school at 8 AM, in the evening pig feeding, on Saturday looking for food, on Sunday going to church. Sometimes I helped sell in the shop and I worked one time monthly for Karen Student Network Group (KSNG). Now I am here with my family. We are being looked after and protected well. We have all our rights."

Picture 16: Before and after drawing by Participant 4 in the Karen female 20-24 years focus group

P4: "Before I came to Canada I looked after my baby at home. Being a housewife I had no time to go out. Now I am in Canada, I have to look after my baby, I have to go to school also. I receive an allowance from the government. Sometimes there are programs for us and we are invited to attend the meeting or the training. Here, although being a housewife, I have all the rights as a person."

Picture 17a: Before drawing by Participant 3 in the Karen female 20-24 years focus group

Picture17b: After drawing by Participant 3 in the Karen female 20-24 years focus group

P3: "When I was in refugee camp my daily works were house cleaning, washing, going to church on Sunday. On Saturday ... with my friends we were looking for food in the jungle, in rainy season we went up hill searching for bamboo shoot. But when I am in Canada now, I stay in an apartment of a high-rise building, go to school, send my baby to day care, come back in the evening, and walk my children to park for them to play."

Picture 18a: Before drawing by Participant 5 in the Karen female 20-24 years focus group

Picture 18b: After drawing by Participant 5 in the Karen female 20-24 years focus group

P5: "When I was in the camp, I lived an easy life. My parents cooked for me. Mom woke me up at 7 AM for breakfast and then I went to school. I came back home in the evening and helped sell things for my mother. Sometimes I went to church and searched food. We distributed news for KSNG, once a month. Now I am in Canada. I go to school and stay at home. I have no work to do. Sometimes I go for walks with my friends. When there is work to do, I go and sell things."

Picture 19a: Before drawing by Participant 2 in the Karen female 20-24 years focus group

P2: "When I was in refugee camp, I had no job to do. My daily activities were cooking, cutting firewood, washing, going to the church on Sunday, and that's all."

Picture 19b: After drawing by Participant 2 in the Karen female 20-24 years focus group

P2: "Now when I am in Canada, I have a lot of activities, caring for baby at home, taking baby to daycare, walking baby to the park, going to the hospital on appointment days, shopping on Sundays, and playing when there is time. I intend to go to school in the coming school term." [31]

6.2.3.1 The group's own reflections of their roles and responsibilities based on their drawings

P4: "We can see many great differences. Here, going to school you need to learn very hard and listen very carefully. When we were in Mae La U camp we did not need to try very hard. In the camp we received monthly foods and need, no worry for food and rent. Here we have to pay our rent and spend money wisely. We must work very hard and end up with fatigue in the evening. There are many house works, so we have less time to visit friends and neighbors. People in the refugee camp have enough time to visit friends and relatives, and speak with each other as much as they want. Conditions here are not like that in the camp."

P2: "As for me, I was quite happy in the camp, but money was very rare. Having no money and the food supply was not enough. The income comparison between there and here is very great. There, people have freedom of worship, but do not have permission to travel. Here we have freedom to travel anywhere. We have to work very hard to get enough money, monthly, to make ends meet. We search for money, buy, and eat delicious food. We are tired also. Here we work much and we eat much. Sometimes we go outing, for example, yesterday I went to the zoo. There are many great differences in shopping, travelling, and so on."

P1: "In refugee camp, I never work in the community. I was a housewife and worked in house, washing, cooking, cleaning, etc. Coming here there are great changes; I never see snow before. Everything is new to me. Here I travel by bus. There, travel on foot, step on mud make us dirty but we could manage. Here, we have to take all the precautions before we go out. Dress everyone with warm clothes, neat and tidy so the comfort is better. In the camp we did not need to dress ourselves too much."

P3: "One great change that I see here is—here, man and woman have equal right. In the camp we see that the standard of woman is below man. Here, we have equal right without any boundary."

P1: "In the camp women have to look and take care of their babies and have no time to study. Here although we have school children at home to care about we all still have chance to go to school and study. Men, women, old, and young all have equal right. There are no boundaries between married and unmarried persons. They all have equal right."

P4: "In the camp some people are very busy working in the community. Camp leaders have to write monthly planning and report and all who work with them are busy all the time. I was not one of them. Working there had no time limit. Some people work all day and come back home late at night. Most of the works are voluntary. In Canada, time is very precious. There is plenty of time in refugee camp. Time is not important there. We value friendliness and visit each other and meet often. Here, people value time to work most of the time to get enough money for their expenditure. Here, if you have appointment, you must be on time. If you are late, it will become difficult for the ones who help you."

P1: "When I was in the camp, I used charcoal to make fire and cook with it. Here, we use electric oven to cook and we only need to switch on and off. The situations are totally different. Work is getting easier and the living standards are becoming higher."

P4: "I had had some knowledge that could be used there for KSNG. Here, my knowledge is not enough and not up to standard to be used. I am useless. I feel that it is tight for me. Because everyone has equal right, we need to work harder."

P2: "Canada is a developed country, which gives and respects equal rights for everyone. This is different than refugee camp."

P5: "As for me, a big change is police attitude. Police there always try to find fault upon you and threaten you. They stop us, search our things, charge us, and detain us. Police here are good. They help us when we ask for help. When they meet us they say 'Hi' and smile at us. When I first arrived I was scared of the police, very much. Whenever I heard the sound of the police vehicle, I wanted to run away. Gradually I came to realize that I need not worry meeting a policeman. They are really friendly." [32]

6.2.3.2 Karen peer (youth) researcher's (Sheila's) reflection of the drawings across participants in this group

Participants' drawings and their descriptions of their individual drawings conveyed that before coming to Canada, their responsibilities included household chores, such as cooking, cleaning, and sweeping the floor and/or the street, which are in line with the gender role expectations of the Karen girls. They also went to school and engaged in related activities. In general, the drawings show that their life revolved around the home. Overall, Karen youth's roles and responsibilities have changed as well as increased after coming to Canada. Upon a closer look at the drawings, we can observe other common differences between the before and after images. The first is the difference between the before and after images of homes and the school buildings, which is a reflection of the change in context—rural refugee camp-based homes and schools and those in an urban setting in a country such as Canada. The second (common) differences between the before and after images pertains to the shift in the centrality of household roles: in the after images, participant's life seems to include more community and social life. Volunteering and participating in youth group or choir in church are examples of such (newly added) roles. [33]

The focus group discussion went beyond the drawings, during which the participant youth from the three communities reported that their roles and responsibilities both increased and changed. In other words, in addition to continuing the same kind of responsibilities that they held prior to migration, they took on more and different responsibilities at home as well as outside the home (i.e., in the community). [34]

Many youth spoke about having the same responsibilities in Canada as they had prior to migration (e.g., cooking, cleaning, and babysitting). They felt busier in Canada because they had more schoolwork, a part-time job, or increased responsibility to their family in addition to continuing the tasks they had done prior to migration. Most often the youth felt that they had the assistance of their parents and other family members for their school work or part-time jobs in the pre-migration context; however, in the post-migration context, they often did them on their own or with little support from the family (in some cases, because their family members were not in Canada). [35]

Some of the new family responsibilities that the participants took on in the new context were highlighted: acting as interpreters for their parents and grandparents; providing financial support to the family; providing emotional support for their family; and being intermediary between their family members and the organizations or institutions (e.g., accompanying family members to medical appointments, reading letters, doing bank transactions, and helping with official documents). These additional responsibilities were not related to the youth becoming older but were owing to their greater understanding (in comparison to their parents) of the new language and the culture. Participants also spoke about financially supporting those family members who had not migrated with them, and of their desire to send money back to the community they had come from in order to help rebuild it. The youth also spoke of the importance of helping other newcomers, refugees, and members of their community in Canada (e.g., helping newly arrived friends with finding accommodation and moving). In many cases, the new responsibilities were not necessarily spoken about in a negative way, rather simply a fact of their present circumstances as well as an opportunity for personal growth or greater feelings of self-worth or self-efficacy. [36]

A summary of the themes and supporting excerpts from the focus group discussions across 16-19 and 20-24 female participant focus groups from the three communities is presented in Table 2.

|

Themes |

Excerpts |

|

Increased responsibilities |

"The expectations are higher ... They expect me to provide more. They expect me to ... do more than I was doing before" (Sudanese female, 20-24 years focus group). |

|

Positive change |

"It makes me organized, you know, what I'm going to do and it makes me more responsible, more accountable for my actions" (Sudanese female, 20-24 focus group). |

|

Negative change |

"Because of my family role, such as fulfilling all the roles as shopping, cooking, cleaning house, sometimes I don't find enough time to go to join the group that ... that's one way these roles affect other parts of my life. And also, and usually on Saturday when I ... like in refugee camp we, every week we had time to visit friends, hang around, and have fun. But here it's very hard to meet up with friends and I really can make it like once or twice a month, not every week, consecutive weeks" (Karen female, 16-19 years focus group). |

|

Acting as interpreter for parents and grandparents |

"Sometimes when the visitor comes to see my parent and I need to interpret for them, sometimes they use a difficult word ... so I cannot explain it, cannot interpret" (Karen female, 16-19 years focus group). |

|

Providing financial support to the family |

"When we were in Afghanistan, we didn't have to work outside because of any financial or economical problem. Over there my father worked. But here, we all have to work and we have to support our family financially. I think this is a kind of change" (Afghan female, 16-19 years focus group). |

|

Providing emotional and moral support for their family |

"If we try to teach them, they themselves do not feel good about themselves. My father is exactly like that always. Whatever we tell our father, he says that because he does not understand English. I don't know what to say" (Karen female, 16-19 years focus group). |

|

Being intermediary between their family members and the organizations or institutions

|

"Before when we were in another county, my father knew their language, and he was almost responsible for everything. But here, because I and my brother know English more and better than my father, then our responsibility increases as well. We have to take our grandmother and our father to doctors' appointments and also solve the problems at home. Here the responsibilities fall more on the children because they learn English much faster, that's why" (Afghan female, 16-19 years focus group). |

|

Volunteering in the community |

"After I came to Canada, I go to regular school, do volunteer in school library, at a senior home and also I cook rice, clean things" (Karen female, 16-19 years focus group) |

|

Sending money back home

|

"I know you're trying to minimize the amount of money you have, and I also had to send some money home. That was a given, so trying to adjust here ... trying to adjust, you're trying to get with the lifestyle that's here, which is a little more expensive than back home and send some money home because you're abroad" (Sudanese female, 20-24 years focus group). |

Table 2: A summary of the themes and supporting excerpts from the focus group discussions regarding the changes in roles and responsibilities [37]

The multiple data collection methods (i.e., drawings and individual reflections on them, and focus group discussions) we used in this study were complementary: the drawings provided unique insights into certain aspects of their lives. For example, the magnitude of the difference in youth's (built and natural) environments came up in the drawings that were not discussed in the focus groups. The sense of cohesion versus scattered and chaotic patterns in the drawings is also interesting. On the other hand, the focus group discussions provided unique information on other aspects of their lives, such as racism. In addition, the drawings also provided more contextual information that enriched the understanding gained from the focus groups. For example, the focus group discussions did not provide much information about the nature of "home," the immediate and surrounding environment and the issues of displacement, and how the youth perhaps understood, interpreted, and lived the realities of being refugees in their hometowns and/or refugee camps and their lives in the post-migration context. For example, their before drawings are "emptier" than the after drawings. Also, the responsibilities before coming to Canada seem to have been less time and place oriented than those after coming to Canada. This can be observed in the use of space and where the participants situate themselves and their activities. The after drawings contain more buildings and the activities are depicted in boxes or closed forms whereas there is more fluidity in the activities in the drawing about the pre-migration context. In some instances, the after coming to Canada drawings list activities in a compartmentalized form, in well-organized rows with fixed spaces in between them. Both the drawings and the focus group discussions confirmed the areas of change (and increase) in roles and responsibilities in the lives of refugee youth in the post-migration context. The focus on work versus play was discussed in the focus groups and was reinforced in the drawings. [38]

8. Lessons Learned and Final Thoughts

As discussed earlier, we embedded the drawing component into our focus group in line with arts-informed method to provide multiple and complementary modes of expression for participants. A key lesson learned from this process relates to the importance of providing adequate time and opportunity for the participants to 1. conceptualize and produce the drawings; 2. refer to, interpret, and discuss their drawings; and 3. add to or change their drawings as the focus group discussion unfolds. Facilitators need to ask specific follow-up questions that clarify and expand the link between the drawings and discussions. Sample follow-up questions include: How is what you just said represented in your drawing? How would you represent that in your drawing? It is also important to provide individual turns in discussing each person's drawing to ensure (similar to what can take place in focus group discussions) that those who are more verbal or comfortable in the language do not take more time or control the discussion. Other researchers who have used arts-informed methods also echo the importance of having a thoughtful investigative organizational structure to facilitate richer engagement and follow-up discussions (FREY & CROSS, 2011; RODRIGUEZ-JIMENEZ & GIFFORD, 2010). [39]

We were aware that different participants have different comfort levels with doing and sharing their drawings in group setting. Facilitators did emphasize to participants not to worry about artistic value of the drawings. As is the case often with arts-informed research, some participants verbalized that they were not good at drawing and some did minimal amount of drawing or just used text. The types and depth of the drawings participants did were influenced by other participants' drawings as they were looking at each other's drawings during the activity. Similarly the changes in facilitators' instructions also may have influenced the drawings. For example, Sudanese facilitators placed emphasis on writing or text rather than drawing. [40]

These challenges are similar to those faced in terms of verbal communication within focus groups where the type of comments and the depth of the conversation are influenced by the other group members as well as the facilitators' questions and comments. Some of these challenges can be overcome through better facilitation processes. For example, the drawing exercise can combine free drawing with some facilitated components, where the facilitators guide all participants to draw (or write) some elements. A potential facilitated drawing exercise could be as follows: first, draw yourself before and after coming to Canada; then, draw your home before and after coming to Canada; now, draw the responsibility you consider the most important before and after coming to Canada. This way all participants have some elements drawn through a facilitated process; the rest can be free drawn. As part of lessons learned, several practitioners of arts-informed research have highlighted that fully open structure does not inherently result in richer participation and, in fact, may appear intimidating to some people (FREY & CROSS, 2011). As part of facilitative drawing process, facilitators may also do their own drawing on a flipchart to encourage co-participation between the facilitators and the participants. [41]

Participants need to be encouragingly reminded that there is no such thing as bad drawings. Participants need to be given the option of writing texts when they are having a hard time drawing or when they feel it is not possible to capture something adequately (e.g., discrimination, racism). Facilitators can give examples of how texts can be creatively used to portray views and experiences (e.g., the size, form, or the placing of texts) and the combination of drawings and texts can also be powerful. Facilitators can remind the participants that "visual silences" can have meaning. [42]

These methodological steps can ensure that arts components are integrated with other data generation methods in a more seamless and interactive way while overcoming some of the barriers and hesitations that participants may face in creating and sharing their drawings. Crucially, involving community and peer researchers in collaborative analysis can provide rich contextual interpretation of arts-informed data, including capturing very subtle culturally specific nuances, contradictions, as well as "silences" in visual representation of lived experiences. Based on our experience, we also recommend the multilevel data analysis approach we have presented here in analyzing data in arts-informed research. [43]

The first author would like to thank Dr. Jennifer LAPUM, School of Nursing at Ryerson University, Toronto, Canada, for her feedback on a previous version of this article.

1) A Convention refugee is "a person who meets the refugee definition in the 1951 Geneva Convention relating to the Status of Refugees. This definition is used in Canadian law and is widely accepted internationally. To meet the definition, a person must be outside their country of origin and have a well-founded fear of being persecuted for reasons of race, religion, nationality, membership of a particular social group or political opinion" (http://ccrweb.ca/en/glossary) [Accessed: July 30, 2015]. <back>

2) S = private sponsorship, G = government assisted refugee, W = World University Service of Canada sponsorship, R = refugee claimant <back>

3) English as a Second Language classes <back>

4) Some youths reported more than one place of current education. <back>

Bagnoli, Anna (2009). Beyond the standard interview: The use of graphic elicitation and arts-based methods. Qualitative Research, 9(5), 547-570.

Ball, Susan & Gilligan, Chris (2010). Visualising migration and social division: Insights from social sciences and the visual arts. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung / Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 11(2), Art. 26, http://nbn-resolving.de/urn:nbn:de:0114-fqs1002265 [Accessed: November 20, 2013]

Birman, Dina (2006). Acculturation gap and family adjustment findings with Soviet Jewish refugees in the United States and implications for measurement. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 37(5), 568-589.

Brislin, Richard W. (1983). Cross-cultural research in psychology. Annual Review of Psychology, 34, 363-400.

Citizenship and Immigration Canada (CIC) (2014). 2014 Annual report to parliament on immigration. Ottawa: CIC, http://www.cic.gc.ca/english/resources/publications/annual-report-2014/ [Accessed: May 20, 2014]

Citizenship and Immigration Canada (CIC) (2010). Canada facts and figures immigration overview permanent and temporary residents. Ottawa: CIC, http://www.cic.gc.ca/english/pdf/research-stats/facts2010.pdf [Accessed: May 20, 2014]

Cole, Arda & Knowles, Gary J. (2011). Arts-informed research. In J. Gary Knowles & Arda L. Cole (Eds.), Handbook of the arts in qualitative research: Perspectives, methodologies, examples, and issues (pp.55-70). Los Angeles, CA: Sage.

East, Patricia L. (2010). Children's provision of family caregiving: benefit or burden? Child Development Perspectives, 4(1), 55-61.

Estrella, Karen & Forinash, Michele (2007). Narrative inquiry and arts-based inquiry: Multinarrative perspectives. Journal of Humanistic Psychology, 47(3), 376-383.

Frey, Ada F. & Cross, Cecilia (2011). Overcoming poor youth stigmatization and invisibility through art: A participatory action research experience in greater Buenos Aires. Action Research, 9(1), 65-82.

Fuligni, Andrew & Pederson, Sara (2002). Family obligation and the transition to young adulthood. Developmental Psychology, 38(5), 856-868.

Glick, Jennifer (2010). Connecting complex processes: A decade of research on immigrant families. Journal of Marriage and Family, 72(3), 498-515.

Guruge, Sepali & Butt, Hissan (2015). A scoping review of mental health issues among immigrant and refugee youth in Canada: Looking back, moving forward. Canadian Journal of Public Health, 106(2), e72-e78.

Halcón, Linda L.; Robertson, Cheryl L.; Savik, Kay; Johnson, David R.; Spring, Marline A.; Butcher, James N.; Westermeyer, Joseph J. & Jaranson, James M. (2004). Trauma and coping in Somali and Oromo refugee youth. Journal of Adolescent Health, 35(1), 17-25.

Huss, Ephrat (2007). Houses, swimming pools, and thin blonde women. Qualitative Inquiry, 13(7), 960-988.

Hynie, Michaela; Guruge, Sepali & Shakya, Yogendra B. (2012). Intergenerational relationships through the eyes of Afghan, Karen and Sudanese refugee youth in Canada: Role reversal or resettlement champions? Journal of Canadian Ethnic Studies, 44(3), 11-28.

Karen Human Rights Group (2011a). "All the information I've given you, I faced It myself": Rural testimony on abuse in eastern Burma since November 2010. Thematic report KHRG #2011-06, http://www.khrg.org/sites/default/files/khrg1106.pdf [Accessed: March 30, 2012].

Karen Human Rights Group (2011b). Attacks on health and education: Trends and incidents from Eastern Burma, 2010-2011. Thematic report KHRG #2011-05, http://www.khrg.org/khrg2011/khrg1105.pdf [Accessed: March 30, 2012].

Karen Refugee Committee (2012). Newsletter and Monthly Report, January 2012, http://www.burmalibrary.org/docs13/KRCMR-2012-01-red.pdf [Accessed: March 30, 2012].

Khanlou, Nazilla & Guruge, Sepali (2008). Refugee youth and identity: On the margins of mental health promotion theory, research and practice. In Maroussia Hajdukowski-Ahmed, Nazilla Khanlou & Helene Moussa (Eds.), Not born a refugee: Refugee women reclaim their identities in research, education, policy and creativity (pp.173-179). Oxford: Berghahn Books and Refugee and Forced Migration Studies.

Khawaja, Marwan; Linos, Natalia & El-Roueiheb, Zeina (2007). Attitudes of men and women towards wife beating: Findings from Palestinian refugee camps in Jordan. Journal of Family Violence, 23(3), 211-218.

Knowles, Gary J. & Cole, Ardra L. (Eds.) (2008). Handbook of the arts in qualitative research: Perspectives, methodologies, examples, and issues. Los Angeles, CA: Sage.

Kreiger, James (2002). Using community-based participatory research to address social determinants of health: Lessons learned from Seattle partners for healthy communities. Health Education and Behavior, 29(3), 361-382.

Leong, Frederick; Leung, Kwok & Cheung, Fanny, M. (2010). Integrating cross-cultural psychology research methods into ethnic minority psychology. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology, 16(4), 590-597.

Lesch, Ann M. (1998). The Sudan: Contested national identities. Arab Studies Quarterly, 23(2), 111-114.

Marshall, Grant N.; Schell, Terry L.; Elliott, Marc N.; Berthold, S. Megan & Chun, Chi-Ah (2005). Mental health of Cambodian refugees 2 decades after resettlement in the United States. JAMA, 294(5), 571-579.

McQuillan, Jeff & Tse, Lucy (1995). Child language brokering in linguistic minority communities: Effects on cultural interaction, cognition, and literacy. Language and Education, 9(3), 195-215.

Minkler, Meredith & Wallerstein, Nina (Eds.) (2003). Community-based participatory research for health. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Montgomery, Edith (2011). Trauma, exile and mental health in young refugees. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica, 124, 1-46.

Morales, Alejandro & Hanson, William (2005). Language brokering: An integrative review of the literature. Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences, 27(4), 471-503.

Orellana, Marjorie Faulstich (2001). The work kids do: Mexican and Central American immigrant children's contributions to households and schools in California. Harvard Educational Review, 71(3), 366-389.

Oznobishin, Olga & Kurman, Jenny (2009). Parent-child role reversal and psychological adjustment among immigrant youth in Israel. Journal of Family Psychology, 23(3), 405-415.

Pauwels, Luc (2010). Visual sociology reframed: An analytical synthesis and discussion of visual methods in social and cultural research. Sociological Methods & Research, 38(4), 545-581.

Prosser, Jon (2011). Visual methodology: Toward a more seeing research. In Norman K. Denzin & Yvonna S. Lincoln (Eds.) The Sage handbook of qualitative research (pp.479-495). London: Sage.

Rodriguez-Jimenez, Anthony & Gifford, Sandra M. (2010). "Finding voice": Learnings and insights from a participatory media project with recently arrived Afghan young men from refugee backgrounds. Youth Australia Studies, 29(2), 33-41.

Rose, Gillian (2012). Visual methodologies: An introduction to researching with visual materials. London: Sage.

Shakya, Yogendra B.; Guruge, Sepali; Hynie, Michaela; Htoo, Sheila; Akbari, Arzo; Jandu, Barinder; Murtaza, Rabea; Spasevski, Megan; Berhane, Nahom & Forster, Jessica (2014). Refugee youth as "resettlement champions" for their families: Resilience, empowerment and vulnerabilities. In Laura Simich & Lisa Anderman (Eds.), Refuge and resilience (pp.131-154). New York: Springer.

Statistics Canada (2006). 2006 Census of population. Ottawa: Statistics Canada, http://www12.statcan.ca/census-recensement/2006/index-eng.cfm [Accessed: June 20, 2012].

Telzer, Eva H. & Fuligni, Andrew J. (2009). Daily family assistance and the psychological well-being of adolescents from Latin American, Asian, and European backgrounds. Developmental Psychology, 45(4), 1177-1189.

The Mosaic Institute (2009). Profile of a community: A "smart map" of the Sudanese diaspora in Canada. Toronto: The Mosaic Institute, http://media.wix.com/ugd/102a59_a320a979b9235408ae805c6c95dbca88.pdf [Accessed: November 4, 2014].

Tober, Diane (2007). "My body is broken like my country": Identity, nation, and repatriation among Afghan refugees in Iran. Iranian Studies, 40(2), 263-285.

Trickett, Edison & Jones, Curtis (2007). Adolescent culture brokering and family functioning: A study of families from Vietnam. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology, 13(2), 143-150.

U.S. Committee for Refugees and Immigrants (USCR) (2007). World refugee survey 2007. Arlington, VA: USCR, http://www.uscrirefugees.org/2010Website/5_Resources/5_5_Refugee_Warehousing/5_5_4_Archived_World_Refugee_Surveys/5_5_4_5_World_Refugee_Survey_2007/5_5_4_5_1_Statistics/RefugeesAndAsylumSeekers_Worldwide.pdf [Accessed: June 4, 2013].

United National High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) (2011). Population levels and trends. In Tarek A. Chabaké & Joseph Tenkorang (Eds.), UNHCR statistical yearbook: Trends in displacement, protection and solutions (pp.20-31). Geneva: UNHCR, http://www.unhcr.org/516286589.html [Accessed: August 4, 2012]

United National High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) (2013). UNHCR's engagement with displaced youth: A global review. Geneva: UNHCR, http://www.refworld.org/pdfid/5142d52d2.pdf [Accessed: June 4, 2014].

Walsh, Sophie; Shulman, Shmuel; Bar-On, Zvulun & Tsur, Antal (2006). The role of parentification and family climate in adaptation among immigrant adolescents in Israel. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 16(2), 321-350.

Dr. Sepali GURUGE is a Professor in the School of Nursing at Ryerson University, Toronto, Canada. Her research focuses on the complex intersections of gender, race, class, and health throughout the pre-migration, border crossing, and post-migration contexts. In particular, her work has advanced knowledge in the area of violence against women and elder abuse in immigrant communities in Canada. Her most recent project (Strength in Unity, funded by Movember Foundation) aims to engage over 2,000 boys and men from East, South, and Southeast Asian communities in Toronto, Calgary, and Vancouver, to address the stigma of mental illness in their communities in Canada. She is currently the Co-Director of the Centre for Global Health and Health Equity as well as Co-Lead of the Centre for Research and Education on Violence against Women and Children at Ryerson University. Her commitment to applying a global health perspective to immigrant health has led to collaborations with colleagues in Asia, Africa, Europe, and South and North America. She has published in several languages, making her work accessible beyond English-speaking audiences. Dr. GURUGE has received numerous awards for her work, and in 2014, was selected to be part of inaugural cohort of the College of the New Scholars, Artists, and Scientists of the Royal Society of Canada.

Contact:

Sepali Guruge, RN, PhD

Professor, Daphne Cockwell School of Nursing

Ryerson University

350 Victoria Street

Toronto, Ontario, Canada. M5B 2K3

Phone: +1 416 979 5000 ext. 4964

Fax: 416-979-5332

E-mail: sguruge@ryerson.ca

URL: http://www.immigranthealthresearch.com/

Dr. Michaela HYNIE is a cultural psychologist who is currently an Associate Professor in the Department of Psychology at York University, UK, and the founder and Director of the York Institute of Health Research's Program Evaluation Unit. Dr. HYNIE is interested in engaged scholarship; working in partnership with students, communities and organizations, both locally and internationally, on research addressing complex social issues. Her work centers on the relationship between different kinds of social connections (interpersonal relationships, social networks) and resilience in situations of social conflict and displacement, and interventions that can strengthen these relationships in different cultural, political and physical environments. This includes work on culture, migration and health inequities; climate change adaptation and environmental displacement; and social integration of refugees. Dr. HYNIE's work has been funded by the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council, Grand Challenges Canada, the Canadian Institutes of Health Research, the Lupina Foundation, and a range of health and human services agencies.

Contact:

Michaela Hynie, PhD

Associate Professor, Department of Psychology

York University

4700 Keele Street

Toronto, Ontario, Canada. M3J 1P3

Phone: +1 416 736 2100 ext. 22996

E-mail: mhynie@yorku.ca

Dr. Yogendra SHAKYA is the Senior Researcher Scientist at Access Alliance Multicultural Health and Community Services and an Adjunct Professor at Dalla Lana School of Public Health, Canada. Dr. SHAKYA's research focuses on understanding how critical determinants (including employment, income, education, discrimination, linguistic barriers, and social isolation/exclusion) impact the health status and healthcare access for immigrants, refugees and racialized communities. He has ten years of experience leading dozens of successful multi-phase, multi-collaborative research projects. He is particularly interested in building evidence and mobilizing social/policy action to overcome health disparities. Dr. SHAKYA is a recognized leader in implementing and promoting community-based research practices and has trained hundreds of marginalized community members (including youth), and engaged them in leadership capacity as co-producers of knowledge.

Contact:

Yogendra Shakya, PhD

Senior Research Scientist, Access Alliance Multicultural Health and Community Services

340 College Street, Suite 500

Toronto, Ontario, Canada. M5T 3A9

Phone: +1 416 324 8619 ext. 286

E-mail: yshakya@accessalliance.ca

URL: http://www.accessalliance.ca/

Ms. Arzo AKBARI was a peer youth researcher on the Refugee Youth Research Project at Access Alliance Multicultural Health and Community Service, Toronto, Ontario, Canada. She is a graduate of the University of Toronto with a background in political science, languages and literatures. Ms. AKBARI is a community member and activist who is passionate about social justice issues. She has participated in various community-based research projects throughout the GTA, and enjoys sharing and learning about lived experiences of compassion, courage and resilience.

Contact:

Arzo Akbari

Access Alliance Multicultural Multicultural Health and Community Services

340 College Street, Suite 500

Toronto, Ontario, Canada. M5T 3A9

E-mail: arzoakbari@gmail.com

Ms. Sheila HTOO came from remote refugee camps in Thailand to Canada in 2004 as a sponsored refugee student. Since 2007, Ms. HTOO has been a peer researcher and knowledge exchange leader of Access Alliance's several community-based research projects including the Refugee Youth Health Project and the Knowledge-to-Action (KTA) Initiative. She has also been working with the newly emerging populations in Toronto as a medical interpreter and an outreach worker. Recognizing many unique needs and challenges faced by the underserved Karen refugee community in Toronto and in Canada, she acts a strong community advocate and is very interested in making changes through community-based research and participatory planning processes with marginalized communities. She holds a Master of Science degree in planning from the University of Toronto, and is currently a PhD Candidate in the Faculty of Environmental Studies at York University, Toronto, Ontario, Canada.

Contact:

Sheila Htoo

Access Alliance Multicultural Multicultural Health and Community Services

340 College Street, Suite 500

Toronto, Ontario, Canada. M5T 3A9

E-mail: sheilahtoo85@gmail.com

Ms. Stella ABIYO is a community worker with over seven years of experience within community settings assisting new immigrants, refugee youth, and women fleeing and living in domestic violence situations as well as persons who have been diagnosed with mental health issues. Ms. MONA worked as a Refugee Youth Peer Researcher on the Refugee Youth Research Project at Access Alliance Multicultural Health and Community Services, Toronto, Ontario, Canada. She holds Honors Bachelor of Arts in women and gender/equity studies, Diploma in assaulted women/children counseling advocate and recently graduated with a Bachelor of social work. She is currently working as a housing support worker, with women who have been diagnosed with mental health issues. Ms. ABIYO has developed an interest in the intersectionality of mental health and immigration processes particularly those coming into Canada from war zones, and hopes to make this the chore of her interactions with individuals diagnosed with mental health.

Contact:

Stella Abiyo

Access Alliance Multicultural Multicultural Health and Community Services

340 College Street, Suite 500

Toronto, Ontario, Canada. M5T 3A9

E-mail: abiyo.mona@gmail.com

Guruge, Sepali; Hynie, Michaela; Shakya, Yogendra; Akbari, Arzo; Htoo, Sheila & Abiyo, Stella (2015). Refugee Youth and Migration:

Using Arts-Informed Research to Understand Changes in Their Roles and Responsibilities [43 paragraphs]. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung / Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 16(3), Art. 15,

http://nbn-resolving.de/urn:nbn:de:0114-fqs1503156.