Volume 17, No. 1, Art. 11 – January 2016

Using Vignettes Within Autoethnography to Explore Layers of Cross-Cultural Awareness as a Teacher

Jayne Pitard

Abstract: With this article I aim to progress the use of vignettes within autoethnography by explaining the conceptual framework for my structured vignette analysis. In researching my role as a teacher of a group of Timor-Leste vocational education professionals I have undertaken a phenomenological study using autoethnography to highlight the existential shifts in my cultural understanding. I use vignettes to place myself within the social context, to explore my positionality as a researcher and to carefully self-monitor the impact of my biases, beliefs and personal experiences on the teacher-student relationship. To assist my analysis I developed a structured method for analysing each vignette to reveal layers of awareness that might otherwise remain experienced but concealed. In my analysis I describe the context, the experience told as a personal story, the emotional impact on me of this experience and my reflexivity to the described experience. I identify strategies I developed resulting from the impact the experience had on my interactions with my students. This structured vignette analysis reinforces the necessity of all these research elements within autoethnographic writing. I provide an example to highlight the usefulness of this method.

Key words: autoethnography; phenomenology; vignette; structured vignette analysis; reflexivity; cultural understanding

Table of Contents

1. Introduction

2. The Use of Vignettes Within Phenomenology

3. Structured Vignette Analysis

4. An Example of a Structured Vignette Analysis

5. Impact of Structured Vignette Analysis on My Teaching Practice

6. Scope and Limitations

7. Conclusion

Autoethnography is a contentious qualitative research methodology which speaks from the heart about existential experiences (ANDERSON, 2006; DENZIN, 2006; ELLIS, ADAMS & BOCHNER, 2011). It allows scholars to focus on "ways of producing meaningful, accessible and evocative research grounded in personal experience" (§2). Autoethnography is self-focused and context-conscious (NGUNJIRI, HERNANDEZ & CHANG, 2010; REED-DANAHAY, 1997). It is a constructive method for researching the teacher-student relationship (the teacher and the students are from diverse cultures and economic backgrounds), as it allows an in-depth exploration of the researcher as a teacher. Over 12 months on behalf of my university I delivered a graduate certificate in vocational education and training (GCVET) to a group of 12 Timorese technical and vocational education and training (TVET) professionals. In 2012 I travelled to Timor-Leste (TL) initially to meet the students and gain an understanding of the TVET system in TL. The 12 students travelled to Melbourne for a three-month study on campus and completed their qualification through implementation of a major project in TL. I returned to TL nine months later for their final assessment. The interface between these students and me as their teacher is the subject of my research in which I seek to understand the impact of cultural difference on the teacher-student relationship. I conducted a two-part study: firstly, from the perspective of myself as the teacher (autoethnography) and secondly, from the perspective of the students (case studies). At its core, my research is animated by an interest in understanding how I responded to the cultural challenges of working with a group of Timorese students and how these students responded to learning in another culture. The phenomenology presented as a harmonious methodology to study my experience, and the lure of speaking from my heart (about the lived experience through the use of vignettes within autoethnography as a method) was compelling. ELLIS et al. (2011) state autoethnography, as a method, is both process and product. As my research progressed, however, the dichotomy of finding a sense of structure within the process of autoethnography presented as an issue. [1]

With this article I aim to describe my journey towards developing the structure I sought within the process of writing my autoethnography. I wrote 13 vignettes describing existential moments in my cultural shift and these needed to be described in context without an overarching narrative. Each vignette had to stand alone as a text and follow a pathway which would connect all 13 vignettes. To achieve this I developed a structured vignette analysis framework to guide the writing of each vignette. This article is designed to draw the reader into the world of phenomenology, initially to distinguish the role of the anecdote in recreating the epoche, the pre-reflective moment of an experience (VAN MANEN, 2014). It then describes my quest to avoid self-indulgent introspection in writing about my epoche, which led to the development of a structured vignette analysis to create a collaborative journey between the author and the reader. I conclude with an example of a vignette which occurred on my first day of teaching my students. [2]

2. The Use of Vignettes Within Phenomenology

Phenomenology is essentially the study of lived experience or the life world (VAN MANEN, 1990). It considers the world as lived by a person and not as an experience that is separate from a person (LAVERTY, 2003). Phenomenology is a methodology that is helpful for us to understand the nature and meaning of everyday experience. With this method we can investigate the meaning of participants' experiences of a phenomenon in which the researcher is either an observer or a participant (VAN MANEN, 1990). In essence, "phenomenology describes how one orients to lived experience" (p.4). HUSSERL (1970 [1936]) asserts that all knowledge begins with experience, but not every experience produces knowledge. How we interpret the lived experience determines whether developed knowledge will result. Generally we can see the experience as something that happens to us (beyond our control) and which we react to in the moment, and then we can see the experience as something we become conscious of and begin to interpret. The pre-reflective stage is when the experience happens to us, before we consciously start thinking about it. We suspend our judgement and set aside our assumptions, to instead analyse the phenomenon itself, in its purity. HUSSERL describes it as "an epoche—we call it the 'transcendental reduction' ... an accomplishment of a reduction of 'the' world to the transcendental phenomenon 'world'" (p.58). This stage is referred to variously in the literature as the epoche, transcendental reduction, phenomenological reduction or bracketing (FRIESEN, HENRIKSSON & SAEVI, 2012; HUSSERL, 1970 [1936]; LAVERTY, 2003; VAN MANEN, 2014). According to HUSSERL the epoche dictates that any phenomenological description must be written in the first person to ensure it is described as it is experienced. [3]

2.1 Autoethnography as a phenomenological research tool

Within a phenomenological framework, the use of autoethnography as a research tool places the self at the centre of a cultural interaction, as it explores the impact of an experience on the writer. Autoethnography is an approach to research and writing to "describe and systematically analyse (graphy) personal experience (auto) to understand cultural experience (ethno)" (ELLIS et al., 2011, §1). Autoethnography retrospectively and selectively indicates experiences based on, or made possible by, being part of a culture or owning a specific cultural identity. Telling about the experience though must be accompanied by a critical reflection of the lived experience to conform to social science publishing conventions (ELLIS et al., 2011). The use of vignettes to examine and analyse lived experiences can provide a window, through which the reader can gain an understanding of the insight which comes from placing a person with one cultural identity in a setting of different cultural norms. [4]

CHANG (2007) warns against self-indulgent introspection in autoethnography which tends to alienate the reader from the cultural interaction taking place. She argues that "autoethnography should be ethnographical in its methodological orientation, cultural in its interpretive orientation, and autobiographical in its content orientation" (p.207). Autoethnography should emphasise "cultural analysis and interpretations of the researcher's behaviours, thoughts, and experiences in relation to others in society" (ibid.). My aim for using autoethnography as a methodology is to understand the impact of cultural difference on me, my teaching and my relationship with my students. I also intended to draw the reader into the inner workings of the social context studied, thereby enhancing the reader's understanding and knowledge of the culture studied. This could be explained as a collaborative journey between the reader and me, as the author. [5]

REED-DANAHAY (1997) proposes that autoethnography connects the social to the cultural by exploring the self within the cultural context, to extend knowledge and understanding of the sociological setting within a culture. CHANG (2007) also emphasises the cultural (ethnographic) nature of autoethnography stating that this characteristic of autoethnography distinguishes it from other forms of narrative writing by connecting the personal to the cultural, the self to the social, where the self refers to the ethnographer self. ALEXANDER (2005) states that autoethnography "engages ethnographical analysis of personally lived experience" (p.423). The development of this genre of research has been driven by a desire to produce significant, accessible and evocative accounts of personal experience to intensify our ability to empathize with people who are different from us (ELLIS & BOCHNER, 2000). Autoethnography permits us a wider research lens with which to study our lived experience, as it allows the researcher's influence to be acknowledged, as it accommodates and even embraces subjectivity. The process of autoethnography involves writing about and analysing selected epiphanies that stem from interactions involving being part of a culture (ELLIS et al., 2011). ELLIS et al. propose that it is a duty of autoethnographers in analysing their personal experience to consider ways others may experience similar epiphanies. They further contend that it is in the analysing of personal experience in such epiphanies that the characteristics of a culture become familiar to those inside and outside the culture. In the autobiographical style of writing used in autoethnography, it is important to show through personal descriptive writing how the epiphany was invoked through thoughts, emotions and actions. Emphasising ethnographic performance, ALEXANDER (2005) states that showing is "less about reflecting on the self ... as an act of critically reflecting culture, an act of seeing the self through and as the other" (p.423). This showing can make writing emotionally rich; but to enable the reader to consider the events in a more abstract way it needs to be balanced with some telling. Telling is a style used by an author to state what happened from a less emotional, involved standpoint (ELLIS et al., 2011). [6]

With the challenges of CHANG (to focus on the cultural interaction to distinguish it from other forms of narrative; 2007), ELLIS et al. (to consider the ways others may have experienced my epiphanies; 2011) and ALEXANDER (to balance my writing with showing and telling; 2005), I searched for analytical and representational strategies that would enable me to increase self-reflexivity and honour my commitment to the actual whilst providing the reader with an opportunity to think about the events in a more abstract way. To conform to this version of autoethnography, I used anecdotes to describe (show) moments of cultural existential crises and explored my experiences, by reflecting on my reactions and subsequent actions, in dealing with these crises (telling). Adopting this method of self-conscious reflexivity (ELLIS & BOCHNER, 1996) has specified my exact relation to self and my culturally different students (ALEXANDER, 2005). I strived for this process of showing and telling through the use of narrative vignettes and memory recall based on notes recorded as the event happened, followed by an analysis of my reflexivity to these crises. I have endeavoured to shun self-indulgent introspection by emphasising the cultural impact in my analyses of my narrative vignettes. They are not a simple story of my life. They are a story of my interaction with another culture. [7]

VAN MANEN (2014) uses the term anecdote to describe writing about the reduction moment or epoche. He states that "what makes anecdotes so effective is that they seem to tell something noteworthy or important about life" (p.250). He describes the use of the anecdote in autoethnographic writing to give voice to the unconscious, deep and pathic sensations experienced in the reduction moment. He contends that phenomenological writing should try to find "expressive means to penetrate and stir up the pre-reflective substrates of experience as we live them ... to discover what lies at the ontological core of our being" (p.240). We should use the expression of our anecdotes, the words we use to express our pre-reflective experience, to stir up memories of the event that remained previously unknown to us (in the unconscious). In this regard I allowed myself the liberty of writing freely whilst expressing my lived experience within vignettes, and only allowed myself reflection and editing when writing my analyses of the moments described in my vignettes. This almost hypnotic, trance-like state of expressing the existential moments captured in my anecdotes allowed my unconscious to divulge the depth of my experience. HUMPHREYS (2005) uses embedded autoethnographic vignettes with the intention of creating stories to stimulate an emotional response and provoke understanding from his readers (p.842). He connects with his innermost feelings during periods of career stress and describes experiences that his audience can connect with also. The reader is transported to the moment of truth for HUMPHREYS. In another method of connecting with innermost feelings SALDANA (2003) describes the use of ethnodrama in performance vignettes as "the reduction of field notes, interview transcripts, journal entries and so forth to salient foreground issues ... the 'juicy stuff' for 'dramatic impact'" (pp.184-185). The results are a participant's or researcher's combination of "meaningful life events" (p.221). [8]

To make sense of the cultural impact of outstanding (impactful, transformational) interactions with my Timorese students, I have mentally transported myself to the pre-reflective moment using my journal entries and photographs as prompts to write my autoethnographic vignettes. Whilst I acknowledge the retelling of these stories has already altered the pre-reflective experience simply through putting the experience into words (VAN MANEN, 2014), the anecdotes are the closest I could transport myself to the pre-reflective moment of happening. These vignettes present a record of how I made sense of what happened, as a practitioner. This practice of structured analysis in my interactions with my students allowed me to examine my own contribution to the way our relationships developed. It was essential for me to use my reflexivity as a means to achieve an expansion of my understanding of myself and my students in our interactions. I used a wide-angle lens with a focus on the social and cultural aspects of the personal, revealing multiple layers of awareness, to understand the experience as lived. In so doing I have exposed the "vulnerable self that is moved, refracted and resisted" during the process of showing, but I have attempted to focus on the social and cultural in my analysis, the telling (HAMILTON, SMITH & WORTHINGTON, 2008, p.24). [9]

3. Structured Vignette Analysis

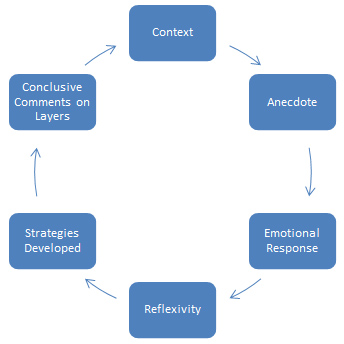

The use of a structured vignette analysis has the advantage of revealing several layers of awareness in my writing, described by RONAI (1995) as the layered account. The different voices of the researcher add to the richness of the analysis as the personal leads into the academic reflexive voice. I achieved this through the development of a six-step framework (Figure 1). Each of these layers adds a different perspective to my vignettes. The six steps in my structured vignette analysis are listed in Figure 1 and explained individually.

Figure 1: Structured vignette analysis [10]

Truth is negotiated through dialogue and the context of that dialogue is vital to the shaping of the data. It is through the dialectical process (the tolerance for holding apparently contradictory beliefs; PENG & NISBETT, 1999) that members of a community with different cultural backgrounds come to an understanding of their social world. The researcher and the participants are "changed" by the experience and the new knowledge is a result of this interaction, bound by the timing of the interaction and the context in which the interaction took place. "Context is something you swim in like a fish. You are in it. It is you," according to DERVIN (1997, p.130). DERVIN proposes that most writers about context postulate its meaning as a focus on process. She states it is "attention to process, to change over time, to emergent and fluid patterns" (p.116). Context becomes known when the researcher turns the research lens back on the researcher. Interpretivism and constructivism manifest understanding of the meanings behind the actions of individuals to understand "the entire context, at both the macro and micro environmental level" (PICKARD, 2007, p.13). With the context relevant to each individual vignette, the reader discovers the progress of the researcher and the students over time. [11]

In narrative anecdotes, the pre-reflective impact is recalled to return the researcher to the conditions before reflection or the written word impacts on the recall, to restore contact with the lived experience (VAN MANEN, 2014). VAN MANEN prescribes "a certain succinctness" in the style of the anecdote (p.252). He suggests "a set of guidelines for gathering powerful narrative material or for editing appropriate lived experience descriptions into exemplary anecdotes:

An anecdote is a very short and simple story.

An anecdote usually describes a single incident.

An anecdote begins close to the central moment of the experience.

An anecdote includes important concrete details.

An anecdote often contains several quotes (what was said, done and so on).

An anecdote closes quickly after the climax or when the incident has passed.

An anecdote often has an effective or 'punchy' last line: it creates punctum" (ibid.). [12]

This relates to the immediate physiological and emotional responses experienced as the existential crisis unfolds. An emotional response is involuntary and unconscious. HOCKENBURY and HOCKENBURY (2011) describe three components to an emotional response: a subjective experience, a physiological response and a behavioural response. [13]

BERGER's definition of reflexivity takes into account the positionality of the researcher:

"Reflexivity is commonly viewed as the process of a continual internal dialogue and critical self-evaluation of a researcher's positionality as well as active acknowledgement and explicit recognition that this position may affect the research process and outcome" (2015, p.220). [14]

The emphasis on reflexivity as a process, rather than an attitude or a single action, aligns with my philosophy that reality is constantly in flux and the moment we observe reality, it is already changing. The automatic internal dialogue commences as soon as we experience something, and being aware of that internal dialogue and taking control of it is the essence of reflexivity. To take control of this internal dialogue BERGER argues that

"researchers need to increasingly focus on self-knowledge and sensitivity; better understand the role of the self in the creation of knowledge; carefully self-monitor the impact of their biases, beliefs, and personal experiences on their research; and maintain the balance between the personal and the universal" (ibid.). [15]

Counter transference is a term used in psychodynamic language (BERGER, 2015) to explain the impact of clinical practitioners' own history and issues on their understanding of and reactions to the client. According to HUGHES and KERR (2000), FREUD believed the practitioner's formative dynamics (assumptions based on personal life experience and important, impactful early relationships with adults such as parents) could transfer to the patient, and vice versa. He coined the term counter transference to describe this process. Transference involves the projection of assumptions based on a previous experience to a present experience (HUGHES & KERR, 2000). Reflexivity in research is the researchers' acknowledgement of and response to the impact of their own history and life issues on their interactions with their research participants. Reflexivity acknowledges that counter transference occurs in research involving participants, from the participants to the researcher, and from the researcher to the participants. As a white Australian female, 64 years of age, married with three children, English speaking with knowledge of French, with 26 years of teaching experience at the university but no previous experience teaching students from a different culture, I was forced to acknowledge my own inadequacies in teaching students whose life experience was in many ways much deeper than mine. This was juxtaposed with my level of education and multifaceted experience of travel and lifestyle which placed me in a position of seeming to have skills to cope with the situation. But I was a "babe in the woods" unaware of the impact my students would have on me. [16]

The practice of reflexivity in my interactions with my students allowed me to examine my own contribution to the way our relationships developed. Reflexivity has been increasingly recognised as an essential strategy in the process of producing knowledge through qualitative research. "Since the researcher is the primary 'instrument' of data collection and analysis, reflexivity is deemed essential," WATT (2007, p.82) explains. It was essential for me to use my reflexivity as a means to achieve an expansion of my understanding of myself and my students in our interactions. According to RUSSELL and KELLY (2002), reflection allows researchers to become aware of not only what enhances their ability to see, but also what may inhibit their seeing. [17]

Using reflexivity to expand my understanding of an interaction between myself and the other offers an opportunity to develop strategies to transform future interactions into more positive experiences. This section of my layered account records how I changed my approach to interacting with my students to accommodate for the difference which had become evident to me. Sometimes this involved using different teaching strategies and sometimes further questioning of myself and the students to understand how best I could accommodate their needs. Questioning my assumptions exposed taken-for-granted attitudes that did not apply to the students from TL. [18]

3.6 Conclusive comments on layers

Bringing together the different layers of my account provides a concise summary of the effects of this experience and how I strived to move forward to further develop my understanding of a different culture. [19]

4. An Example of a Structured Vignette Analysis

My autoethnography is based on my teaching practice with a group of TVET students from TL. The questions I seek to answer with my vignettes and analysis are:

What happens when a first world educator, in her own environment, is drawn together with students in an environment new to them?

What particular strategies does the educator develop to assist her to deal with difference?

What teaching strategies does the educator develop to assist her to move from understanding and applying through to analysing, evaluating and creating, working together effectively? [20]

TL is a devastated country. After approximately 500 years of governance the Portuguese withdrew from TL in 1975. Nine days later TL was invaded by Indonesia on the pretext of protecting its citizens in Timorese territory. A bitter fight for independence by the Timorese led to a 1999 United Nations referendum in which the Timorese voted overwhelmingly for their independence. Indonesia withdrew destroying most of the nation's infrastructure in its wake. TL declared its independence in 2002. During this struggle for independence TL lost one quarter of its population (GOVERNMENT OF TIMOR-LESTE, 2015). [21]

The United Nations has criteria for defining least developed countries: gross national income per capita, instability of agriculture production, instability of exports of goods and services, share of agriculture, forestry and fisheries in GDP, under five mortality rate, adult literacy rates, secondary school enrolment ratio, percentage of population undernourished, and victims of war or invasion (UNITED NATIONS DEVELOPMENT POLICY AND ANALYSIS DIVISION, 2015). The Australian Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade (DFAT) website states:

"Over two thirds of Timorese still live below US$2 a day. The country's mainly subsistence-based agriculture sector struggles with low productivity and limited access to markets. The private sector is small and weak. Businesses face considerable obstacles, including difficulties accessing finance, a low-skilled workforce and poor infrastructure. The maternal mortality rate is the highest in the region, while school enrolment has improved, but the quality of education remains poor. Women face significant barriers in accessing education and employment and high rates of domestic violence. And nutrition remains a major concern: 50 per cent of children under five years have stunting—one of the highest rates in the world." [22]

This data is provided to inform readers on the cultural difference between myself and my students. Six of the students had not travelled outside TL. Two had studied in Australia and four had studied in other countries including Indonesia and Switzerland. I am a teacher of 27 years at a University in Melbourne, Australia, and had no experience of teaching international students from a least developed country. [23]

The TL students flew directly from Dili in TL via Darwin in the north of Australia and arrived in Melbourne on a cold day in early July 2013. We spent the first day settling them into their apartment accommodation, buying supplies of food, opening bank accounts, purchasing public transport passes and mobile phone accounts. These expenses were provided through a Victorian State Government grant which also covered their airfares and weekly allowance. I taught them how to use an ATM at the bank, catch a train and tram, and how to use the washing machine and dishwasher in their apartments. Two students had studied in Australia and they assisted in the process. On their second day we launched into study at the university. [24]

The university classroom allocation system generally allowed for a maximum of three-hour sessions, timetabled over a full semester. As a result of my unusual short-term request for a dedicated classroom for this group of students for a 12-week period, we were allocated a small internal classroom. On our first day together in a classroom, which had no windows to the outside world, I was keen for them to get to know me and themselves, and to learn to trust me and each other. I briefly told them my life story, emphasising my professional career. This act of emphasising my professional career rather than my personal life was my first indication that I was uncertain how to relate to them. I already regarded them as the other, wary of getting too personal, contrary to my attempt to get them to trust me. I invited them to participate in a get-to-know-you activity which I had used successfully with many past groups of Australian students. This was an opportunity for real bonding and I stumbled through it in a state of uncertainty. [25]

I had prepared an activity in which students would walk in pairs to a private space anywhere in the university. They were instructed to tell their story, whatever they chose to tell, for 15 minutes without being interrupted by the other person. Their partner was to listen without taking notes, to not interrupt and to remember as much of the story as possible so they could retell it to the wider group. The purpose of this activity was primarily to get to know each other. With this activity the students use skills in listening without interrupting, speaking at length without prompts, and remembering salient points from a personal story. Participants could share or choose not to share aspects of their lives. There was no pressure to disclose more than they were comfortable with. On this occasion, I was unable to foresee the emotions this activity might rouse. Below is an extract from my journal. [26]

As the pairs drift back into the room, I ask for a volunteer to tell the first story. The youngest member of the group raises his hand. He stands and commences to tell the story told to him. He paints a picture of a person who has suffered under the harsh regime in TL prior to 1999, who has lost family members and close friends. About four minutes into his retelling he begins to sob. Tears stream down his face. My heart begins to race as I become alarmed that I am intruding into a space in his head and heart that I am not qualified to handle. I fear for him and his fellow countrymen that I am opening up wounds that are still too raw to speak about. My vision blurs as I panic and ask him to sit down. I struggle to find my voice as I apologise to the group saying I had not realised this exercise would recall experiences too difficult to speak of, and that we will cease the activity and move onto something else. They sit very still looking towards me. They seem far away from me, not with me. I am not able to read their emotions from their facial expressions or body language. I suggest a 20-minute break so we can all compose ourselves. [27]

I had not anticipated that this activity would awaken such memories and I asked myself why I had not foreseen this. My past experience with this exercise with local students was stories of personal achievement, professional challenge, experience in vocational education, and sometimes insight into personal aspiration. Why did I not give the time to think through the consequences of this activity to understand the volatility of the experiences that may surface in the conversations between the students from TL? I think I got as much fright from my lack of foresight as I did from the realisation I had to handle a situation I did not feel qualified for. I am not a psychologist or professionally qualified to deal with post-traumatic stress, which is what I instantly labelled this in my mind. I panicked. I apologised for evoking such difficult memories and told them we would cease the activity immediately. I did not discuss this with them. I did not seek feedback or comment. I simply ceased the activity and told them to take a break. Then I moved on. [28]

It distresses me even now to think about this incident as I now feel I did not respond appropriately. This was confirmed by one of the students in interview at the end of their course who told me the group was confused as to why I stopped the activity as they had enjoyed the exchange of stories. The emotional response from the student, who stood and retold his pair's story, was commonplace to them. I asked myself why I did not see that also. Why did I not imagine that retelling the stories in a safe environment in a faraway culture, although emotional in the recollection, might be traumatic for them? The answer is I have no experience to match theirs. I based my reaction on my own experience of a world where trauma is "swept under the carpet" and largely goes unacknowledged. I am 64 years of age and growing up in the 1950s and 1960s in Australia (we now know) meant keeping secrets about unrepeatable misdemeanours on the vulnerable in our society. I attended Catholic primary and secondary schools, and religious personnel I came into contact with have been tried and convicted on charges of gross indecency towards children. I have witnessed people's trauma in the media, on television and in newspapers, and personal accounts in books, blogs and articles. As an adult I acknowledge the travesty of what happened when I was a child and beyond. But faced with a situation, where unspeakable violence had been imposed on the vulnerable in TL, the child in me wanted to "sweep it under the carpet" and move on, as I had been taught to do. The social conditioning of my childhood had implicitly been activated. I feel shame that I was not able to stay with the students on that day and bear to hear what they wanted to tell. I feel I failed them. I feel I am a casualty of my own society yet I have spent years studying, reading, discussing and in psychoanalysis breaking down the barriers to understanding my perception of my world and how this can differ profoundly to others' perception of a similar world. Years of grounding collapsed in a single misunderstood interaction with an other from a different (unexperienced by me) culture. And I was only on my second day with these students. [29]

Asking myself if it is the responsibility of my university to provide some strategic training for dealing with students from a traumatised nation, I fled to my office to seek solace from my university colleagues. I felt ill equipped and unprepared to deal with traumatised students who had experience of massacre and loss of loved ones. My preparation for teaching these students had been of my own volition. I had chosen to read about the history of TL and research papers on the development of the political system and education infrastructure. I had also read some research papers on teaching international students, most of which discussed cultural tendencies to being reserved and having difficulty in contributing to class discussions. I had not read any psychological research on dealing with victims of trauma. My colleagues listened and expressed empathy, but a few minutes of empathy did little to assuage my guilt. I had no choice but to return and continue to work with my students. [30]

My reflexive response to this incident was to be careful and to avoid discussions of lives and experiences. This changed over time as I became more aware of the students' working conditions and experience. We discussed work contexts and strategies with enthusiasm, especially in relation to their major project assignments. However, I know little of their private lives except what I gleaned from my conversations with them on our weekend outings. Despite this by the end of the 12 weeks I had become much attached to them as a group, and individuals within the group had contributed enormously to my own understanding of overcoming difference. [31]

4.6 Conclusive comments on layers

Establishing knowledge of each other leading to trust was foremost in my mind in introducing the walk-and-talk activity. I had not taken the time to think through what stories might emerge as a result of this activity. This produced shame in me for failing to protect them as part of my duty as their teacher. It generated an explosion of panic and unpreparedness in me which initiated childlike self-searching and self-blaming. I could not have foreseen this happening; however, it assisted me to understand I had not prepared myself adequately to deal with the cultural difference I was experiencing. I needed to become more aware of their needs and more aware of my own lack of knowledge of who these students were. [32]

5. Impact of Structured Vignette Analysis on My Teaching Practice

During my teaching experience with the Timorese I kept journal entries of my personal experience, notes on teaching strategies commenting on what worked and what did not, notes on conversations I had with students, photographs of students' mind maps (which became their favourite method of learning), photographs of notes from the whiteboard in the classroom. At the commencement of most days as a group we would list on the whiteboard what we hoped to achieve for the day and I would photograph the white board for my records. I would photograph the whiteboard at the end of the day along with mind maps drawn noting any discrepancies which had arisen during the course of the day. These methods of recording my interactions with the students provided rich data to inform my vignettes. [33]

To capture as closely as possible the pre-reflective experience in my vignettes, I used my journal entries as a springboard to create a trance-like state in which I propelled myself back in time to the actual experience, the point of contact. I allowed the vision to flow, capturing the essence of body language, facial expressions, physical sensations, such as a racing heart and altered spatial awareness. This process was supported variously by my notes from the end of each day on my teaching strategy, photographs, e-mails to and from students and visual prompts such as the mind maps. [34]

Using the structured analysis of my vignettes I developed a critical awareness of how these existential crises shifted my thinking on how I was teaching the Timorese. After the experience outlined in the vignette above I had to regain confidence in my ability to teach this group and to develop teaching strategies to compensate for the difference I perceived. It was a journey both for them and for me and it was essential our pathways of understanding crossed sooner rather than later for them to gain what they needed from me. My realisation of my lack of knowledge of the cohort and the assumptions I carried with me into the classroom was enhanced with this structured vignette analysis. I developed a process for questioning my assumptions that were based on my life experience, and the assumptions of the students based on their life experience which assisted both them and me to come to a better understanding of their needs and how best to manage those needs. [35]

This research is a phenomenological study of the teacher-student relationship between me as an Australian teacher and the students from a developing country. I use autoethnography as a methodological tool to highlight the existential shifts in my cultural understanding. In my study I refer to the terms epoche, phenomenological reduction and bracketing used variously to describe the transcendental reduction (HUSSERL, 1970 [1936]) of the lived experience as described in my autoethnography. Whilst my work references these terms to assist in explaining the transcendental reduction or pre-reflective stage of studying my lived experience, the focus of my research is not on a serious analysis and critique of these concepts. These terms are offered by way of assisting the reader to understand the phenomenological nature of my autoethnography and are not intended to provide an in-depth analysis of the terms themselves. [36]

While my autoethnography is a story about me as a first-time teacher of international students and, in particular, this group of students, I have produced within my vignettes not just a story of a single incident as an anecdote but have located this anecdote within a broad framework which future researchers could utilise in their research process. I have used this framework as a strategy to move forward as a teacher, not just as a vignette to discuss a particular incident. It is a process for exploring a particular incident within a broad framework to assist the development of a considered, strategic response by me as the teacher. My selection of the six categories used to explore more fully the anecdote itself, and my reaction to it, was a deliberate choice. Since my study is about students from a developing country, many of whom have not previously travelled outside TL and me as a teacher with limited previous experience of teaching international students, the categories within my framework that seemed most relevant were those that relate to emotion. This is why I included the categories of emotional response and reflexivity. The categories of context and strategies developed relate to my professional self as a teacher in a particular setting. My practised reflexivity assisted me as a teacher to develop a more appropriate and respectful manner towards my students and to plan for future contingencies whilst teaching this group of students. [37]

In my structured vignette analysis, I use the term vignette in reference to my framework of six-stage analysis. My anecdote sits within the six stages of the vignette. The use of the terms anecdote and vignette are often interchanged in qualitative research methodology and my search for an explanation of their interchangeability resulted in my preference to use the term vignette to describe my six-step structured framework. I use the term anecdote to distinguish the narrative of my lived experience, which is Step 2 in my framework and I have written my anecdote, my lived experience, in the present tense. It is presented in italics to distinguish it within my vignette, as the anecdote is central to the vignette. The "Sage Encyclopaedia of Qualitative Research Methods" does not contain an entry for anecdote and describes vignettes as "stimuli that selectively portray elements of reality to which research participants are invited to respond" (HUGHES, 2008, p.918). No entry is describing vignettes as autobiographical stories written within an autoethnography. However, ELLIS et al. (2011), HUMPHREYS (2005) and RONAI (1995) all use the term vignette to describe the writing of their personal experiences within autoethnography. Earlier writers on phenomenological research use the term anecdote to describe the telling of their lived experience and VAN MANEN (2014) provides a set of guidelines for writing powerful narrative material in an anecdote. He states an anecdote should be short and simple; it should describe a single incident and begin close to the essential experience and should finish with impact. VAN MANEN's guidelines do not include an emotional response, an analysis of one's reflexivity or of strategies developed as a result of the experience. By adding these categories I have moved beyond VAN MANEN's guidelines prompting me to adopt the term vignette as used by contemporary researchers to describe my autoethnographical reflections. [38]

The use of autoethnography as a research tool has been useful to me. It has allowed me to explore in wholeness and without bashfulness the unique experience of teaching students from a dissimilar culture for the first time. Autoethnography gave me the freedom to be introspective in my reflexivity, to be as honest as I could be to the actual interactions I experienced with the students and to account for their perspectives to avoid indulgent subjectivity. To achieve the balance in my writing that I knew would redeem it from indulgence I developed a framework for reporting on my existential crises. This structured vignette analysis (context, vignette, emotional response, reflexivity, strategies developed) places the reader within the epoche (pre-reflective moment) and through the emotional journey of the writer providing some concluding comments on the layers exposed. Recalling the context enabled my emotional transportation to the epoche allowing me to explore the moment of panic and shame. I was then gently funnelled towards the exploration of my reflexivity. The strategies I developed as a result of each experience are a true window for the reader to see into the soul of my dawning cultural understanding. [39]

This research provides a rich story of a first-time teacher of international students adapting to building a relationship with students from a developing country, some of whom had no experience of another culture. Whilst this story is about one teacher with one group of students, it is hoped the framework developed for the structured vignette analysis can assist other teachers in the future, to similarly use this process to document their important work with international students. [40]

Alexander, Bryant K. (2005). Performance ethnography: The re-enacting and inciting of culture. In Norman K. Denzin & Yvonna S. Lincoln (Eds.), The Sage handbook of qualitative research (3rd ed., pp.411-441). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Anderson, Leon (2006). Analytic autoethnography. Journal of Contemporary Ethnography, 35(4), 373-394.

Berger, Roni (2015). Now I see it, now I don't: Researcher's position and reflexivity in qualitative research. Qualitative Research, 15(2), 219-234.

Chang, Heewon (2007). Autoethnography: Raising cultural awareness of self and others. In Geoffrey Walford (Ed.), Methodological developments in ethnography 12 (pp.207-221). Oxford: Elsevier.

Denzin, Norman K. (2006). Analytic autoethnography, or déjà vu all over again. Journal of Contemporary Ethnography, 35/4, 419-428.

Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade (DFAT) (2015). Overview of Australia's aid program to Timor Leste, http://dfat.gov.au/geo/timor-leste/development-assistance/pages/development-assistance-in-timor-leste.aspx [Date of access: May 4, 2015].

Dervin, Brenda (2003). Given a context by any other name: Methodological tools for taming the unruly beast. In Brenda Dervin & Lois Foreman-Wernet (with E. Lauterbach) (Eds.), Sense-making methodology reader: Selected writings of Brenda Dervin (pp.111- 132). Cresskill, NJ: Hampton Press.

Ellis, Carolyn & Bochner, Arthur P. (1996). Composing ethnography: Alternative forms of qualitative writing. Walnut Creek, CA: AltaMira Press.

Ellis, Carolyn & Bochner, Arthur P. (2000). Autoethnography, personal narrative, reflexivity: Researcher as subject. In Norman K. Denzin & Yvonna S. Lincoln (Eds.) Handbook of qualitative research (2nd ed., pp.733-768). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Ellis, Carolyn; Adams, Tony E. & Bochner, Arthur P. (2011). Autoethnography: An overview. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung / Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 12(1), Art. 10, http://nbn-resolving.de/urn:nbn:de:0114-fqs1101108 [Date of access: April 14, 2014].

Friesen, Norm; Henriksson, Carinna & Saevi, Tone (2012). Hermeneutic phenomenology in education. Method and practice. Rotterdam: Sense Publishers.

Government of Timor-Leste (2015). History, http://timor-leste.gov.tl/?p=29&lang=en [Date of access: April 21, 2015].

Hamilton, Mary Lynn; Smith, Laura & Worthington, Kristen (2008). Fitting the methodology with the research: An exploration of narrative, self-study and autoethnography. Studying Teacher Education, 4(1), 17-28.

Hockenbury, Don H. & Hockenbury, Sandra E. (2011). Discovering psychology. New York: Worth Publishers.

Hughes, Patricia & Kerr, Ian (2000). Transference and countertransference between in communication between doctor and patient. Advances in Psychiatric Treatment, 6(1), 57-64. http://apt.rcpsych.org/content/aptrcpsych/6/1/57.full.pdf [Date of access: March 10, 2015].

Hughes, Rhidian (2008). Vignettes. In Lisa Given (Ed.), The Sage encyclopedia of qualitative research methods (pp.919-921). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Humphreys, Michael (2005). Getting personal: Reflexivity and autoethnographic vignettes, Qualitative Inquiry, 11, 840-860.

Husserl, Edmund (1970 [1936]). The crisis of European sciences and transcendental phenomenology (transl. by D. Carr). Evanston IL: Northwestern University Press.

Laverty, Susann M. (2003). Hermeneutic phenomenology and phenomenology: A comparison of historical and methodological considerations. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 2(3), Art. 3, http://www.ualberta.ca/~iiqm/backissues/2_3final/pdf/laverty.pdf [Date of access: June 14, 2014].

Ngunjiri, Faith W.; Hernandez, Kathy-Ann C. & Chang, Heewon (2010). Living autoethnography: Connecting life and research [Editorial]. Journal of Research Practice, 6(1), Art. E1, http://jrp.icaap.org/index.php/jrp/article/view/241/186 [Date of access: July 7, 2014].

Peng, Kaiping & Nisbett, Richard E. (1999). Culture, dialectics, and reasoning about contradiction American Psychologist, 54(9), 741-754.

Pickard, Alison J. (2007). Research methods in information. London: Facet.

Reed-Danahay, Deborah E. (1997). Leaving home: Schooling stories and the ethnography of autoethnography in rural France. In Reed-Danahay (Ed.), Auto/ethnography: Rewriting the self and the social (pp.123-144). Oxford: Berg.

Ronai, Carol R. (1995). Multiple reflections of child sex abuse: An argument for a layered account. Journal of Contemporary Ethnography, 23(4), 395-426.

Russell, Glenda M. & Kelly, Nancy H. (2002). Research as interacting dialogic processes: Implications for reflexivity. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung / Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 3(3), Art. 18, http://nbn-resolving.de/urn:nbn:de:0114-fqs0203181 [Date of access: April 15, 2014].

Saldana, Johnny (2003). Longitudinal qualitative research: Analyzing change through time. Walnut Creek CA: AltaMira Press.

United Nations Development Policy and Analysis Division (2015). What are least developed countries (LDCs)?, http://www.un.org/en/development/desa/policy/cdp/ldc_info.shtml [Date of access: April 13, 2015].

van Manen, Max (1990). Researching lived experience: Human science for an action sensitive pedagogy. Albany, NY: State University of New York Press.

van Manen Max (2014). Phenomenology of practice. Meaning giving methods in phenomenological research and writing. Walnut Creek, CA: Left Coast Press.

Watt, Diane (2007). On becoming a qualitative researcher: The value of reflexivity. The Qualitative Report, 12(1), 82-101, http://www.nova.edu/ssss/QR/QR12-1/watt.pdf [Date of access: July 7, 2014].

Jayne PITARD is currently a PhD candidate in education at Victoria University, Melbourne, Australia. She is completing a thesis focused on her teaching of a group of students from Timor- Leste. She has held various teaching and research positions within Victoria University for the last 27 years.

Contact:

Jayne Pitard

College of Education

Victoria University

PO Box 14428

Melbourne, Vic, 8001

Australia

Tel.: +61 418 321198

E-mail: jayne@pitard.com.au

Pitard, Jayne (2016). Using Vignettes Within Autoethnography to Explore Layers of Cross-Cultural Awareness as a Teacher [40

paragraphs]. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung / Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 17(1), Art. 11,

http://nbn-resolving.de/urn:nbn:de:0114-fqs1601119.