Volume 17, No. 3, Art. 6 – September 2016

Outsider Indigenous Research: Dancing the Tightrope Between Etic and Emic Perspectives

Felicia Darling

Abstract: With an example of a single study, I describe the strategic application of etic and emic approaches (in outsider research) to incorporate more insider perspectives. I introduce an iterative methodological model that instantiates the etic and emic theories into methodological practices. The model centers on the concept of methodological flexibility (methods that flex to accommodate insider perspectives). Reframing the balancing etic and emic perspectives in terms of the iterative model and methodological flexibility achieves two goals. Firstly, it supports the process of researcher reflexivity. Secondly, it enables a practical discussion of methodological adaptations that encourage emic perspectives throughout all phases of a study: design, data collection, and analysis. Drawing from my mixed methods study in the Yucatán, I further describe the model for balancing the two polar perspectives. Practical methodological recommendations made could inform other studies conducted by outsiders in indigenous or other communities.

Key words: mixed methods; outsider research; etic; emic; mathematics education

Table of Contents

1. Introduction

2. Emic and Etic Theory

3. The New Iterative Model

4. The Design Phase: Building in Methodological Flexibility

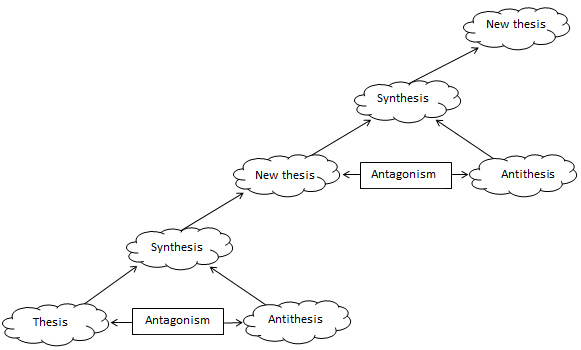

4.1 Theoretical commitment: Adopting a theory

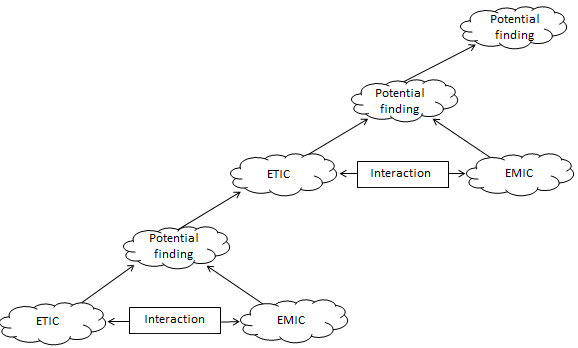

4.2 Recruiting cultural insiders

4.3 Methodological commitments

5. The Data-Collection Phase: The Iterative Model and Methodological Flexibility

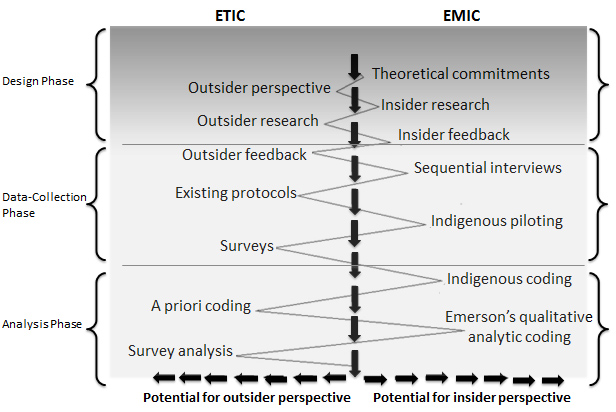

5.1 Navigating the iterative process: Two examples

5.2 Piloting and adapting protocols

6. The Analysis Phase and Beyond: Following Through with Initial Commitments

7. Conclusion

8. Discussion

Appendix 1: Matrix of Research Questions, Data Sources, and Analysis

Appendix 2b: Notes Integrative Memos

BRANNEN (2005) recommends that researchers strategically apply both qualitative and quantitative techniques throughout all phases of mixed methods research and those methodological choices made in the data collection phase determine methodological directions during the analysis phase. The same holds for balancing emic and etic approaches. Although I will discuss etic and emic theory in more detail later, in brief, an emic perspective means an insider perspective while an etic perspective means an outsider perspective. Commitments, made early on, will support the iterative process of balancing etic and emic perspectives throughout the three phases of a study: the design, data-collection, and analysis phases. More specifically, in the design phase, outsider researchers must explicitly make theoretical and methodological commitments to ensure methodological flexibility (i.e., methods are a response to insider feedback). [1]

Throughout the data-collection phase, researchers will navigate this iterative process and maintain methodological flexibility. Finally, researchers must follow through with initial theoretical and methodological commitments in the analysis phase as they continue to balance insider and outsider perspectives. In sum, the strategic application of etic and emic approaches in all three phases of research produces novel results that are informed by how indigenous community members make sense of their world. [2]

The article is structured into three main discussions. In the first part, I describe the etic-emic theory and introduce a conceptual model. The model that describes the dialectic process through which etic and emic approaches inform methodological practices. [3]

Second, I describe specific strategies to both engage in this iterative process, and promote methodological flexibility throughout the design, data-collection, and analysis phases of research. For the purpose, I draw examples from my six-month study in a Yucatec Maya village. The study explored community approaches to problem solving in everyday life and examined what the degree to which formal math instruction capitalized upon these cultural assets. Results indicate that community members approached problem solving using autonomy, and local teachers missed opportunities to capitalize on these cultural assets when teaching math (DARLING, 2016a, 2016b). [4]

Finally, I summarize my methodological recommendations for doing outsider research in indigenous and other communities. Refer to Appendix 1 for a complete list of methods and analyses. [5]

The etic-emic theory was introduced into social science literature by U.S. linguist and anthropologist, Kenneth PIKE (1967). The emic theory explains the insider's view of a phenomenon. Emic approach yields "accounts, descriptions, and analyses expressed in terms of the conceptual schemes and categories regarded as meaningful and appropriate" by those "native members of the culture" being studied (LETT, 1990 p.130). On the other hand, the etic theory describes making sense of an event through the eyes of an external observer. An etic approach yields accounts, descriptions, and analyses expressed in terms of existing "conceptual schemes and categories regarded as meaningful and appropriate by the community of scientific observers" (ibid.). Over the last 50 years, scholarly literature discussed the challenges of emphasizing one perspective over the other. Although many researchers came to regard etic and emic categories as existing more on a continuum than as a strict dichotomy (MORRIS, LEUNG, AMES & LICKEL, 1999; SACKMANN, 1991; ZHU & BARGIELA-CHIAPPINI, 2013), still research frequently framed the tension between the two perspectives as something that needed to be resolved. [6]

However, the two categories of etic and emic remain largely theoretical and the conversations about practically applying the theories can be challenging. For example, the concept of having either an exclusively etic or emic approach when conducting outsider research is paradoxical. At the extreme pole, an etic approach to data collection would mean that the researcher is oblivious to how a researcher's presence, behavior, attitudes or methodological decisions influence insider responses. In an exclusively emic approach, the researcher would merely internalize conceptions and assumptions of study subjects and therefore compromise his or her ability to be objective or communicate findings to an outside community of researchers. Still, one can discuss using methods that lean toward either the emic or etic pole. Advantages of a more emic approach are that it respects community perspectives and tends to illuminate novel, nuanced, more valid findings of the culture being studied (MORRIS et al., 1999). An advantage of a more etic approach is that it invites the potential for cross-cultural analysis (ibid.). [7]

Here, I introduce a new methodological model to describe how emic and etic theory is instantiated in methodological practices. These practices are framed in terms of methodological flexibility, which I define as the potential for methods to flex in order to respond to insider feedback. Together with methodological flexibility, the model addresses the issue of researcher reflexivity. Reflexivity is

"simultaneously being receptive to new cultural domains of understanding and attempting to maintain space for this throughout the entire research process by ceding researcher control beyond the initial phase of negotiation, and extending participation into data collection, analysis and distribution" (NICHOLLS, 2009, p.124). [8]

BLAIKIE (1991) advocates that outsider researchers must work with and seek to understand insider perspectives to complete a study (see also e.g., RIECKEN, STRONG-WILSON, CONIBEAR, MICHEL & RIECKEN, 2005; ROMM, 2015). They traverse the tightrope between emic and etic approaches. Therefore, outsider research requires a certain level of reflexivity on the part of the researcher (BETTEZ, 2014; MOSSELSON, 2010; NICHOLLS, 2009; PILLOW, 2003; RUSSELL & KELLY, 2002). To balance an emic approach, a researcher checks participants' perspectives against findings in the greater body of research. To counter an etic approach, more careful attention must be paid to cultural nuances and characteristics that can be potentially overlooked by an outsider. This balancing is part of the iterative process and is supported by methodological flexibility. [9]

The model is based on ALLAN’s schematic of HEGEL’s dialectic model in Figure 1.

Figure 1: HEGEL's dialectic model (ALLAN, 2005, p.73) [10]

HEGEL's iterative model describes how two competing theses (a thesis and an antithesis) are synthesized into a new thesis through a process of resolving antagonistic tensions (LAUER, 1977). The newly synthesized thesis is then influenced by the same dialectical tension to produce another new thesis, and this iterative process continues (ibid.). In Figure 2, I have adapted ALLAN's depiction to conceptualize how the theoretical categories manifest in fieldwork.

Figure 2: Emic-etic dialectic model (adapted from ALLAN, 2005, p.73) [11]

The thesis and antithesis, represent the tendency toward the etic and emic poles. Although etic-emic theory exists along a continuum, it is inapplicable at the extreme poles. Therefore, while the interaction between the two categories is dynamic, it is not necessarily antagonistic. Consequently, in Figure 2, I have substituted the word "interaction" for "antagonism." [12]

In this model, a researcher has an etic approach (thesis). Through a dynamic and iterative process of interaction, the etic approach (thesis) is acted upon by the emic approach (antithesis). Through this synthesis of different perspectives, a potential finding emerges. This potential finding is then acted upon by the same dialectical tension to produce another potential finding, and this iterative process continues. The model begins with the etic approach because a more etic perspective is inherent in outsider research. Insider perspectives are part of the synthesis process, as they are incorporated with the etic perspectives to inform potential findings. [13]

In Figure 3, a more detailed model illustrates how emic and etic theory is instantiated in specific methodological moves throughout all phases of a study.

Figure 3: The praxis: Emic-etic theory meets on-the-ground practices (adapted from KIMBELL, 2015, p.6) [14]

The zigzag pattern represents the dynamic interaction that exists between methodological realities or commitments that yield either more etic or emic perspectives. The boundaries between the three phases are permeable. For example, the theoretical commitments made in the design phase will continue to inform methodological decisions and potential findings throughout the study. Also, the list of methods in Figure 3 is not meant to be exhaustive. Rather, the purpose of the schematic is two-fold. First, it illustrates the dialectical nature of the instantiation of etic and emic theories in practice. Second, it demonstrates that insider and outsider methodologies inform each other in a dynamic and iterative manner:

In the design phase, an outsider perspective is balanced by theoretical and methodological commitments and that builds methodological flexibility (methods may flex in response to insider feedback).

In the data-collection phase, existing protocols are informed by piloting protocols in the local community.

In the analysis phase, a priori coding and survey analysis draw from an etic perspective to establish potential findings. [15]

However, by negotiating an agreement on open-codes with a cultural insider, the researcher incorporates insider feedback into the analysis and that increases the potential for insider perspectives. [16]

4. The Design Phase: Building in Methodological Flexibility

Methodological flexibility is built in the design phase of a study. Still, there are three theoretical and methodological considerations that a researcher needs to attend. First, s/he should choose a theory of data collection and analysis that will support the iterative process of incorporating both emic and etic perspectives as the study evolves. Second, s/he must consider specific selection criteria when recruiting cultural insiders before design begins. Finally, one must explicitly commit to implementing flexible methods, which are responsive to insider feedback. [17]

4.1 Theoretical commitment: Adopting a theory

The first concern is to adopt a theory of data collection and analysis that supports both: the iterative model of incorporating insider perspectives and methodological flexibility. For example, in my observations and field notes, I adopted a theory of qualitative analytic coding as described by EMERSON, FRETZ and SHAW (2011). It is distinguished from grounded theory in that grounded theory implies that data is pure and therefore the theory is discovered, whereas EMERSON et al. argue that data is already influenced by initial conceptual and analytic commitments inherent in decisions the researcher makes in the early stages of the study. They argue that the field worker renders the data meaningful and creates, rather than discovers theory. It is implicitly acknowledged that a researcher's assumptions, biases, and perspectives influence each methodological decision he or she makes to some extent. It explicates the assumption that outsider researchers tend to skew results toward the etic perspective. This theoretical commitment highlights that: in practice, an exclusively emic approach to outsider research is impossible. Also, this theoretical commitment forms the foundation of this iterative model and informs data-collection and analysis throughout the study. As illustrated in the model in Figure 2, when conducting an outsider research, etic perspectives by default will influence potential findings more than emic. By explicitly committing to EMERSON et al.'s theory, I position myself to be more reflexive. This initial theoretical commitment supports the iterative methodological process and methodological flexibility throughout all three phases of the study. [18]

4.2 Recruiting cultural insiders

The second concern is the recruitment of the initial cultural insider. Before I discuss criteria for selecting cultural insiders, let me state a little about myself. I am a cultural outsider in this indigenous community. Although I had lived in rural poverty, I was White, born in the U.S., a native English speaker, and educated. My initial contact with the community was through an educational project run by a transnational colleague with ties to the local indigenous community. Therefore, my initial cultural insider was a young indigenous woman who had participated in this local project from 6 years old to 22 years old. [19]

Cultural insiders provide guidance in the early stages of the study design. The careful selection of cultural insiders fosters the model. It is important that the cultural insiders have strong connections to both: the most vulnerable, under-represented community members as well as central political figures in the community. Since cultural insiders connect the researcher to subsequent insiders, the study benefits from input from a full range of community perspectives. Before designing a study, a researcher must connect with an initial cultural insider and become familiar with the body of insider research (if it exists). Outsider feedback and research are readily available to any outsider researcher. For example, my initial cultural insider was one of the very few indigenous youth (in the Yucatán) to obtain a bachelor's degree. She had participated in a local project that helped indigenous students complete school. On the one hand, she came from an impoverished family. Her house did not have the plumbing. Her mother passed away during this study due to lack of access to adequate health care. On the other hand, she was well regarded by the local school and political leaders for her outstanding educational achievements. Her broad range of social connections helped to diversify my sample of interviewees since I did snowball sampling. With her as an initial cultural insider, I was able to explore how a factory worker, a cilantro farmer, a business owner, a nurse, and a moto taxi driver approached solving problems in everyday life. As the study progressed, I recruited five more cultural insiders from distinct familial and social networks. [20]

When recruiting cultural insiders, another consideration is the perceived status differences between the researcher and insider consultants (BOTHA, 2011). The perceived status differences between the researcher and cultural insiders are important to identify and negotiate early on (do you mean, early in the study design?). It is crucial that cultural insiders are assertive enough to challenge researcher assumptions, methods, or potential findings that do not reflect community values and perspectives. Cultural insiders will also act as consultants and partners throughout the design, data collection, and analysis phases. Consequently, researchers should plan ahead to write field notes and memos in the native language of the cultural insider as the both will negotiate codes and analyze data. [21]

In conclusion, the careful consideration of cultural insider characteristics early on is important because insider feedback is crucial for pushing your methods along the continuum toward an emic approach. With the assistance of cultural insiders—equal partners in the study design—I was able to tailor my methods to solicit a more local perspective. [22]

4.3 Methodological commitments

The final area of concern is methodological commitments. A researcher must commit to those initial methods, which support the iterative process of incorporating insider perspectives and promote methodological flexibility. Plus, a researcher must lay the groundwork (in design phase) so that she or he may pilot and modify protocols (in data-collection phase). Here, I discuss two examples of methodological flexibility from my study. The first is an example of an initial interview protocol. The second is a metacognitive tool, which supports piloting and modification of protocols. [23]

For the initial interview protocol, I used snowball sampling to conduct 14 community interviews. These served as a set of cases rather than a representative sample. As described in SMALL (2009), I did a sequential analysis of interviews with cultural insiders. I refined and re-evaluated theory. I conducted as many interviews as needed until I reached saturation. Data collection and analysis of interviews was a simultaneous process. The theory and themes, which emerged from earlier interviews, clued up the follow-up questions for the next interview. In other words, the first interview produced findings that clued up the next interview, and the final interview yielded no novel findings. In this way, I was able to incorporate community feedback to refine questions for subsequent interviews. Analyzing the interview transcripts with cultural insiders will guide researchers to select the community members for a subsequent interview and modify protocols. In my study, I committed to SMALL's interview protocol that ensured methodological flexibility and insider feedback informed the results. For example, I gradually transitioned from one interview question, "How do you use math in everyday life?" to another, "How do you improvise in everyday life?" Doing so enabled me to broaden the definition of "using math," to include how local people approached problem-solving in everyday life. [24]

Here, I discuss two metacognitive tools to ensure methodological flexibility. Not only a researcher must commit to flexible-initial methods (those that are responsive to insider feedback) but also she or he must plan ahead to pilot and modify existing protocols throughout the data-collection phase. Those established interview protocols and surveys (that have proven to be robust or reliable in other contexts) may not be appropriate or productive in the new setting. Therefore, these may need to be modified (either slightly or radically). [25]

The first metacognitive tool is having a system to match each research question with each protocol. This tool ensures that each protocol (since it is adjusted to insider feedback) continues to address the research question, which it originally intended. For this, the researcher should create an analysis table (see Appendix 1) and write the research question over each protocol. In my study, there were occasions where I radically changed the protocol to accommodate the ways by which the community made sense of its world. As I navigated through these modifications, the research question acted as a beacon. Later (in the data-collection section), I discuss some specific protocol-adaptations. [26]

The second metacognitive tool is the structure of field notes. This tool lays the groundwork for incorporating insider feedback into the process of piloting and modifying protocols throughout the study. Also, the tool supports researcher reflexivity. The tool makes the researcher's dialogue (about balancing insider and outsider feedback) explicit. For example, my field notes contained four columns. The first three columns contained events observed, notes on my observations, and daily memos. The fourth column was specifically for methodological-adaptations. I would write integrative memos in a separate row, every 1-3 days or 2-3 entries. Now, column 4 included reflections of how feedback (insider or outsider) informed the methodological-adaptations (see the snapshot of field notes in Appendix 2a and 2b). Column 4 entries were key for monitoring the evolution of ideas around methodological-adaptations. For example, I gave two real-life math tasks, which invited the 9th grade Yucatec Maya students to improvise. These were followed by two attitudinal questions. After Task 1, I asked a typical question used in U.S. studies: "Did you like the task? Why or why not?" All of the 62 students responded that they liked Task 1, but my observations and field notes indicated otherwise. After consulting with two 9th grade cultural insiders, Yamilet and Erick, I wrote the following notes in column 4. "Erick is like, Ha, ha. [Students] are not going to be honest about what they did not like." Both Yamilet and Erick said that none of the students would say (on paper) that they did not like the activity. After piloting and modifying the attitudinal questions for Task 2, the 62 students offered equal numbers of negative and positive responses with regards to Task 2. Therefore, making the process of modifying methods more transparent allows the researcher to explicitly include the voices of local student insiders into the dialogue about methods. This feature streamlines the process of incorporating insider feedback into the iterative process to generate findings. [27]

In conclusion, during the design phase of a study, it is important to attend to certain theoretical and methodological considerations, as well as selection criteria for a cultural insider. Attention invested early on will support the researcher as he or she navigates the iterative process of balancing insider and outsider feedback throughout the data-collection and analysis phases. Cultivating methodologically flexibility will push potential findings more toward an emic perspective as the iterative, dialectical process of synthesizing etic and emic perspectives is realized (see Figure 2 and 3). [28]

5. The Data-Collection Phase: The Iterative Model and Methodological Flexibility

In this section, I discuss how etic and emic theories meet on-the-ground practices. Although theoretically etic and emic categories exist at the extreme poles, these extremes do not make much practical sense in terms of methodology. At one extreme pole—the etic approach to collecting data would assert that protocols are interchangeable. It would assume that the protocol designs do not influence participant responses and be equally relevant for all research subjects in every cultural context. At another extreme pole—the emic approach to collecting data might consist of spending an extended period living in a community, internalizing participants' perspectives and incorporating local biases and assumptions into results. In application, etic and emic perspectives interact in an iterative, dialectical process to generate potential findings (Figure 2). In outsider research, the starting point for this process is always more etic due to the researcher’s intrinsic perspective. Here with the help of two examples from my study, I illustrate the iterative process of synthesizing emic and etic perspectives (in the data-collection phase) to generate potential findings of a more emic nature, and the methodological flexibility. [29]

5.1 Navigating the iterative process: Two examples

In this paragraph, I describe the first example of navigating the iterative process of balancing emic and etic perspectives. During my second day in the village, I introduced the game of hopscotch to 8 or 9 children aged 4 through 14. An advantage of being an outsider is that local events may be radically different from the researcher's own cultural experiences. Therefore, an outsider researcher may notice a phenomenon that an insider may overlook as an everyday occurrence. Two days into my six-month study I witnessed a pivotal event in the Yucatec Maya community in my study. This moment laid the groundwork for two of my study's major findings. As was common, children played outside unsupervised, so I was the only adult with the 8 or 9 youth. I explained the "rules" of hopscotch and directed them to throw small, flat rocks. Instead, the children threw flat, giant, tiny, round, and square rocks—and then sticks, coins, and rolled paper. When I said, "throw the rock to the highest number, "12," a 14-year old girl grabbed a chalk and drew a "13" at the top. I was puzzled. I was the "authority" at the game of hopscotch—yet these children were not "following the rules." One point of this example is to show that an etic perspective can get you to the door of how local people make sense of their world. However, soliciting insider perspectives opens that door and invites you in. I could have concluded that Yucatec Maya students do not follow directions well. However, through an iterative process of consulting with cultural insiders and insider research, this initial finding led to one of the major findings of the study. That is: in day-to-day life, the local community members approach problem-solving with autonomy and an improvisational mindset. [30]

I have chosen a second example of the iterative model from the latter part of my study. For five months, I had been observing and interviewing three indigenous, middle school math teachers to explore if math teachers capitalized on community approaches to problem-solving in the classroom. In the U.S., I had taught math to socioeconomically disadvantaged students for 22 years. Compared to the U.S. 9th graders, Yucatan students appeared extremely attentive to authority. For example, when an adult entered the classroom, all of the 32 uniform-clad students instantly ceased all activity, stood up, and in unison chimed, "Buenas tardes Maestro Noé [Good afternoon, Professor Noé]." If Maestra Judit said in a barely audible tone, "Silencio," the room fell immediately silent. If Maestro Olegario merely pointed toward a student's pants as he entered the classroom, the student altered his cuff, without hesitation. On the one hand, as the teacher was presenting material, most of the students would either talk (louder than the teacher) or shout out the class window. At the ten-minute break during the class, at least one-third of all the students was consistently off task. Moreover, students would complete assignments at their own pace and in the order that they chose. As the teacher was explaining a math problem, 11 students would talk about matters other than math; 13 would take notes silently; 9 would talk about a different math problem and would not take notes. The entire scenario was somewhat chaotic. [31]

Simultaneously, I arrived at two competing potential findings. First, these students were extremely attentive to authority and teachers commanded respect. Second, these students were dismissive of authority and teachers expected little in the way of respect. [32]

Through an iterative process of synthesizing insider and outsider perspectives, I was able to arrive at novel findings (informed by insider feedback). First, I referenced outsider research. LAREAU's (2011) study discusses a similar autonomy or independence among working class students in the US. That helped me identify the on-going phenomenon as autonomy. Then, I consulted with an insider, Maestro Olegario, a veteran teacher. He continuously helped me with making sense of the competing realities. He informed that the local teachers provide libertad [freedom to act]; the students would improvise while learning and completing tasks; consequently, students would learn to take responsibility for their actions. My new potential finding was that: unlike in LAREAU's study, the teachers of Yucatec Maya schools accommodated student autonomy—and even cultivated it. Again, I consulted with outsider research. BOALER's (2002) study describes an unexpected chaos at an urban UK school where low-income and minority students excel because teachers let students use their own methods for completing math tasks (at their own pace) and in their own way. Then, I incorporated BOALER's reasoning into my potential findings. I was able to reason that maybe Yucatan teachers accommodated student autonomy in terms of finishing assignments rather than solving math problems. Furthermore, the classroom observations and teacher interviews corroborated the potential finding that the teachers encouraged student autonomy in terms of how students completed their tasks rather than solving math problems. The iterative process continued even after completing my study. Recently, I consulted research about indigenous heritage students from México, and this introduced the concept of respeto [respect] into the "final" results (RUVALCABA, ROGOFF, LÓPEZ, CORREA-CHAVÉZ & GUTIÉRREZ, 2015). [33]

5.2 Piloting and adapting protocols

In this section, I describe methodological flexibility using an example of when I radically adapted an interview protocol for teachers. When considering "established" protocols, the function of the protocol is fixed, while the form is adaptable. A researcher must pilot each protocol, and thus needs to be aware of which research question each protocol is seeking to answer. As mentioned earlier, an analysis table helps to keep track of this (see Appendix 1). When I conducted the initial 11 community interviews, I had planned in the design phase that the protocol and questions would evolve and be informed by the responses of the previous interviewees. However, the structured teacher interview protocol was an established, well-piloted protocol that I had used in a previous study in the U.S. It was a three-tiered interview protocol. The first two parts were the classroom observations of the lesson and the interviews about the lesson. In the third part, I conducted a self-directed, video stimulated recall (VSR) interview. Teachers watched selected video clips of their teaching. Then they responded to the prompt, "Every time you make a decision, stop the video and tell me what you are doing and why." In the U.S. this protocol addressed the research question, "How do teachers' beliefs inform their practices?" In the U.S., I had intentionally allowed the teachers to have autonomy over when to stop the video and to respond as they liked. However, when I piloted the VSR interview protocol with a Yucatec Maya elementary school teacher, it yielded no findings of beliefs at all. Therefore, I had to adapt the protocol. [34]

I consulted with one of the seven, at this point, cultural insiders in my study. Focusing on his feedback and the research question that this protocol was seeking to address, I modified the protocol. Because I was an outsider, I had planned to give the three teachers a self-directed interview, so I would not influence their responses. However, I wanted to find out how their beliefs informed their practices. Therefore, I adapted this protocol to verbally prompt them to stop the video when I saw something interesting and then asked them questions about their practices in each specific moment. In the end, I successfully conducted this modified, three-tiered protocol with the two younger teachers in the study. However, even within a culture, there are individual differences that need to be accommodated. The third teacher, Olegario, who was 65, was not amenable to the VSR interview at all—or even being observed or videotaped. Although I still addressed my research question with this third teacher, the three-tiered interview protocol went through such major transformations that by the end of the study it was unrecognizable. [35]

I was able to use my refined, three-tiered interview protocol with two of the three teachers in the study to explore how beliefs informed practices. Maestro Noé, a new teacher, did not mind me coming unannounced to observe his math classes. Still, it took over five observations before I was able to approach him about videotaping. Maestra Judít, with ten years of experience, allowed me to videotape her class after we met only once. However, the veteran teacher, Maestro Olegario, did not welcome my presence in his math class. During my second classroom observation, he simply left the classroom, unannounced, leaving me to supervise 48 students, whom I did not know, for 50 minutes. During two other attempts to observe, he told me that he was not teaching that day—even though he was. I tried many strategies to observe his math class. I switched my language from "I want to observe" to "I want to attend" your class. I tried gaining his confidence by recruiting him to be a cultural consultant. I spoke with the principal. I consulted with other cultural insiders for strategies. Eventually, I adopted a completely different interview protocol for him. I did not use the three-tiered interview with observations, pre- and post-interviews, and a video stimulated recall interview, to answer the question of how his beliefs were connected to practices. In fact, I only formally observed one of his math classes and conducted one formal interview. Instead, my data from Maestro Olegario was cobbled together from observations of his ethics class, over 40 hours of about 32 informal interviews that included many hours of just standing around talking at school while he interacted with students in his self-assigned role as a student advisor and supervisor. Also, I collected data from a visit to his house, a ride in his car, and introductions to his horse, dog, turkeys, and close friends. By radically adapting my protocol while keeping a close eye on the research question it was intended to answer, I gained access to Maestro Olegario's beliefs about teaching, his students, his community, and his classroom. On his terms and in his own words, I found out how his beliefs informed his practices. In the end, he provided the richest information from his almost 30 years teaching in the school and 62 years in the community, because I radically adapted my protocol to accommodate his ways. [36]

In conclusion, as an outsider-researcher, it is important to become knowledgeable about navigating the iterative process and maintaining methodological flexibility throughout the data-collection phase to remain responsive to insider feedback. [37]

6. The Analysis Phase and Beyond: Following Through with Initial Commitments

Balancing insider and outsider feedback in the analysis phase of a study is as crucial as it is in the design and data-collection phases. In fact, theoretical and methodological commitments made in the design phase should carry forward into the analysis phase. As one can see in Figure 3, methods like quantitative analysis of survey questions and a priori coding on interviews increase the potential for a more etic perspective in outsider research. However, EMERSON et al.'s (2011) qualitative analytic coding and working with local coders to develop open-codes increases the potential for a more emic perspective. Thinking back to the dialectic model in Figure 2, insider and outsider perspectives interact to synthesize new potential findings. This is why it is important to verify all analyses and findings with at least one cultural insider on an on-going basis. Ideally, a cultural insider should participate in the coding and analysis of all interviews. When using a priori codes, an outsider researcher tends to incorporate the biases inherent in the corpus of literature into analyses. If using open codes, a researcher has the tendency to approach it with a particular set of lenses and assumptions. Therefore, negotiating an inter-rater agreement and calculating inter-rater reliability on all codes with a cultural insider will ensure that the researcher is pulling the thread of insider perspectives throughout all phases of the study. Finally, after findings have been established, a cultural insider could co-present with the outsider researcher at formal and informal presentations about the study results. Also, co-publishing with insiders in scholarly journals written in the native language of the target community will subject findings to the scrutiny of insider researchers. Collaborating with the primary cultural insider in my study to analyze data, co-present study results, and co-publish in the native language of the community helped to push my findings toward a more emic perspective. [38]

In this article, I have introduced a conceptual model that depicts the iterative process through which emic and etic perspectives are synthesized to create potential findings. This model enables a more on-the-ground discussion of how etic and emic theory is instantiated in methodological practices. Central to this model is the idea of methodological flexibility, which I define as responsiveness to insider feedback. Focusing on methodological flexibility in the design, data-collection, and analysis phases of a study support researcher reflexivity. Also, I have offered specific practical recommendations for outsider researchers seeking to do mixed methods or ethnographic studies in indigenous communities. [39]

As anthropologists, sociologists, and educational researchers conducting outsider research in indigenous communities, we are responsible for ensuring local perspectives inform our findings (BOTHA, 2011). We must "take persons seriously while looking through them—as much as possible in their own terms—to the world in which they are struggling" (McDERMOTT & VARENNE, 2006, p.19). As outsider researchers, we seek to work from and with our etic perspective in ways that incorporate more emic perspectives. Recommendations in this article are important, not only for outsider researchers doing research in indigenous communities but also in other classroom settings where the researcher is not explicitly from the student community. These methodological recommendations ensure that community perspectives are incorporated into all phases of a study, ultimately influencing research results. [40]

Appendix 1: Matrix of Research Questions, Data Sources, and Analysis

|

Question |

Data sources |

Data analysis |

|

1. Which community approaches to solving problems in everyday life are relevant for math instruction in school? |

Field notes from observing 500 hours of community activities over 5 months. |

Open coding. Wrote initial memos, then focused coding and integrative memos. |

|

|

14 interviews from a range of community members. Snowball sampling used. |

Audiotaped & transcribed. Open-coding, a priori coding, or statistically considered items. |

|

|

15 hours of community advisory interviews with 6 persons to verify findings with school and community members. |

Audiotaped & transcribed. Open coding. Wrote initial memos, then focused coding and integrative memos. |

|

2. What is considered "legitimate" math knowledge and what traits make someone "good" at math according to community members, students, and teachers? |

14 interviews with community members, 5-10 formal and informal interviews with each of 3 teachers, 6 student interviews, 15 classroom observations. |

Audiotaped and transcribed (some). Open coding. Wrote initial memos, then focused coding and integrative memos. |

|

|

280 student surveys |

Descriptive statistics, correlation analysis, subgroup analysis. |

|

3. In which ways does math instruction, capitalize upon, or miss opportunities to capitalize upon, student approaches to problem-solving?

|

Series of 5-10 informal interviews with each of 3 teachers. |

Open coding. Wrote initial memos, then focused coding and integrative memos. |

|

|

One 1-hour VSR interview with each of 3 teachers on selected clips from one lesson. |

Audiotaped & transcribed. Open-coding for teacher beliefs and reported practices. |

|

|

Field notes from observations of 5 lessons from each of 3 teachers. |

Open coding. Wrote initial memos, then focused coding and integrative memos. |

|

|

1 videotaped lesson for each teacher. |

Transcribed, open-coding for observed teacher practices. |

|

|

280 student surveys with math mindset questions. |

Qualitative and quantitative analysis. |

|

|

Observed 2 one-hour student tasks with 60 9th grade students that draw upon student abilities to improvise—with follow-up interviews with 3 students. |

Videotaped & transcribed. Open coding. Wrote initial memos, then focused coding and integrative memos. Attitudinal question on tasks was a priori coded. |

Appendix 2a: Field Notes1)

|

Event |

Field notes |

Memos |

Methods notes |

|

4/22/15 Interview with Yamilet for Task #2 |

Arrived at Yamilet's house 30 minutes early. Erick told me she lived just up the road by the bar, so I skedaddled up there from his house even though I was supposed to meet her in the plaza at 9:00am. Last time she was a little late, so I went to her house. She lived across from a bar. It was an unkempt rugged part of the road with garbage around it. I knocked and there was dog pee outside the door. Her brother came to the door, half-dressed. Obviously, I woke them up. I peeked in the kitchen and there was a hammock in there as well as a couple others in a room off the kitchen. Yamilet came out smiling as if she had not just been woken up. She said that they all stayed up late last night. I wondered where her parents were ... Her abuela [grandmother] seemed to loom in the background during the interview listening. She would slowly walk back and forth. Maybe she was suspicious, maybe just curious. I am sure that she spoke Maya and maybe some Spanish. |

People who speak Maya in Ixil are not in the schools. This generation can understand some Maya, but they do not speak it. Still, one cannot know the influence that the Maya Culture has on the kids. It is in their households. Ex: "A" knows the story about his grandmother's 3 sticks to tell the time of day. The necklace of limes for the dog to wear to ward off colds and flu. The traditions and the dancing. |

Next task should be an open-ended task like this. It should be real life like this. It should be multiple entry points like this. It was not high enough ceiling and It was not aligned with the curriculum. Task one was aligned to the curriculum and high ceiling enough, but it was faux multiple entry points. It just gave the students the freedom to draw what they wanted. They DID like that part of the problem, though. Also, students needed the training to accept that they can do whatever they want to solve these real-life problems. They seemed very hung up in the, "Is this 'math' [school math] or does this just use common sense" (Jorge). |

|

4/22/15 Interview with Erick for Task #2 |

7:55 I got there. His mom let me in and invited me into her living room with comfy chairs and couches. He came in dressed and awake, unlike last time. We started right on time at 8am with the interview. #1 Erick's group said They would fill the tank before the 7.5 hours that it took to empty the tank on Monday and Tuesday. He said that the process they used began with going around the group asking for everyone's opinion. Based on the discussion, they wrote in their notebooks and went from there. At first, they did not like the problem. #2, He said his group started looking at the problem as if it was a math problem and calculated the hours, km and money, but then finally realized that it was easy and did not require math. #3 He says that moto taxis do not have equations to solve problems in daily life. #7 He still gives a problem of adding or subtracting as an example of a math problem in daily life. It is math class, where are the equations and formulas. We realized it was easy when we did not have to use math. |

I did not, but should have ... included questions on Task 2 follow-up that asks about if they like the improvisation part of the task. Do they have opportunities to do real-life problems in class and how close was this to a real-life problem? |

Both Yamilet and Erick confirmed that Question 2 would get at some negative answers. They helped me refine the attitude question from Task 1 because they said students would not be honest with me about that. In Task 2 interviews, give the students the survey to pilot it. Also, interview a kid who has a job. Or stick with same two focal students ... Yamilet and Erick and Jorge. |

Appendix 2b: Notes Integrative Memos

|

4/12/15 Developing Student Task #2 |

This student task was chosen because it was based on real life and it was really open-ended. These students do not have open-ended problems to solve at school because their teachers adhere to the curriculum, but they do face these problems in real life on a daily basis. I wanted to see if the curriculum (which does not have open-ended real-life problems) was a missed opportunity for capitalizing on students' abilities to improvise. Also, I thought I would explore if a community-focused goal of earning money for the school motivated students. In Task #1, the two students interviewed said that they liked the free part of the last task but did not like the math part. In this problem, I tried to make it a real math problem and not try to teach them anything specific from the content in the curriculum. I wanted to see what they do when there really are not constraints on the approach and there is no expected ending point. This problem taps into their autonomy AND their improvisation skills both. Because there are two constructs that I am looking at in this study: 1. autonomy, and 2. improvisational skills. Where do they overlap? Where do they show themselves in the classroom? Where are the places where teachers either capitalize upon and cultivate these skills and where there are missed opportunities to do so? |

1) I wrote all field notes by hand and then transcribed them. Original field notes have been revised for clarity. <back>

Allan, Kenneth (2005). Explorations in classical sociological theory: Seeing the social world. New York: Pine Forge Press.

Bettez, Silvia Cristine (2014). Navigating the complexity of qualitative research in postmodern contexts: assemblage, critical reflexivity, and communion as guides. International Journal of Qualitative Studies in Education, 28(8), 932-854.

Blaikie, Norman W. (1991). A critique of the use of triangulation in social research. Quality & Quantity, 25(2), 115-136.

Boaler, Jo (2002). Experiencing school mathematics: Traditional and reform approaches to teaching and their impact on student learning. New York: Routledge.

Botha, Louis (2011). Mixing methods as a process towards indigenous methodologies. International Journal of Social Research Methodology, 14(4), 313-325.

Brannen, Julia (2005). Mixing methods: The entry of qualitative and quantitative approaches into the research process. International Journal of Social Research Methodology, 8(3), 173-184.

Darling, Felicia (2016a). Is this math? Community approaches to problem solving in a Yucatec Maya village. Manuscript submitted to Educational Studies in Mathematics.

Darling, Felicia (2016b). Incorporating cultural assets in Yucatec Maya math classrooms: Opportunities missed?. Manuscript submitted to Journal for Research in Mathematics Education.

Emerson, Robert M.; Fretz, Rachel I. & Shaw, Linda L. (2011). Writing ethnographic fieldnotes. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

Kimbell, Richard (2015). The "why?" questions. Design and Technology Education: An International Journal, 20(1), 5-7, http://ojs.lboro.ac.uk/ojs/index.php/DATE/article/view/2016 [Accessed: June 1, 2016].

Lareau, Annette (2011). Unequal childhoods: Class, race, and family life. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

Lauer, Quentin (1977). Essays on Hegelian dialectic. New York: Fordham University Press.

Lett, James (1990). Emics and etics: Notes on the epistemology of anthropology. In Thomas N. Headland, Kenneth L. Pike & Marvin Harris (Eds.), Emics and etics: The insider/outsider debate (pp.127-142). Tousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

McDermott, Ray & Varenne, Hervé (2006). Reconstructing culture in educational research. In George Dearborn Spindler (Ed.), Innovations in educational ethnography: Theories, methods, and results (pp.3-31). Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

Morris, Michael W.; Leung, Kwok; Ames, Daniel & Lickel, Brian (1999). Views from inside and outside: Integrating emic and etic insights about culture and justice judgment. Academy of Management Review, 24(4), 781-796.

Mosselson, Jacqueline (2010). Subjectivity and reflexivity: Locating the self in research on dislocation. International Journal of Qualitative Studies in Education, 23(4), 479-494.

Nicholls, Ruth (2009). Research and indigenous participation: Critical reflexive methods. International Journal of Social Research Methodology, 12(2), 117-126.

Pike, Kenneth L. (1967). Language in relation to a unified theory of the structure of human behavior. Berlin: De Gruyter Mouton.

Pillow, Wanda (2003). Confession, catharsis, or cure? Rethinking the uses of reflexivity as methodological power in qualitative research. International Journal of Qualitative Studies in Education, 16(2), 175-196.

Riecken, Ted; Strong-Wilson, Teresa; Conibear, Frank; Michel, Corinne & Riecken, Janet (2005). Connecting, speaking, listening: Toward an ethics of voice with/in participatory action research. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung / Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 6(1), Art. 26, http://nbn-resolving.de/urn:nbn:de:0114-fqs0501260 [Accessed: May 13, 2016].

Romm, Norma Ruth Arlene (2015). Conducting focus groups in terms of an appreciation of indigenous ways of knowing: Some examples from South Africa. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung / Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 16(1), Art. 2, http://nbn-resolving.de/urn:nbn:de:0114-fqs150120.[Accessed: May 14, 2016].

Russell, Glenda M. & Kelly, Nancy H. (2002). Research as interacting dialogic processes: Implications for reflexivity. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung / Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 3(3), Art. 18, http://nbn-resolving.de/urn:nbn:de:0114-fqs0203181 [Accessed: May 12, 2016].

Ruvalcaba, Omar; Rogoff, Barbara; López, Angélica; Correa-Chávez, Maricela & Gutiérrez, Kris (2015). Children's considerateness of others' activities: Respeto in requests for help. Advances in Child Development and Behavior, 49, 185-206.

Sackmann, Sonja A. (1991). Uncovering culture in organizations. Journal of Applied Behavioral Sciences, 27(3), 295-317.

Small, Mario Louis (2009). How many cases do I need? On science and the logic of case selection in field-based research. Ethnography, 10(1), 5-38.

Zhu, Yunxia, & Bargiela-Chiappini, Francesca (2013). Balancing emic and etic: Situated learning and ethnography of communication in cross-cultural management education. Academy of Management Learning & Education, 12(3), 380-395.

Dr. Felicia DARLING is currently the education specialist in mathematics at the Monterey County Office of Education in Salinas, California, USA. She is a Fulbright Scholar who received her PhD in mathematics education from Stanford University in 2016. Her research focuses on teacher beliefs and practices that promote math achievement for students who are historically underserved, such as non-native English speakers, students with unique approaches to learning math, ethnic/racial minorities, indigenous students, and socioeconomically disadvantaged students.

Contact:

Felicia Darling

Monterey County Office of Education

901 Blanco Rd., Salinas, CA 93901

Canada

Tel.: +1 707 483 5113

E-mail: fdarling@monterycoe.org

URL: http://www.feliciadarling.com

Darling, Felicia (2016). Outsider Indigenous Research: Dancing the Tightrope Between Etic and Emic Perspectives [40 paragraphs].

Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung / Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 17(3), Art. 6,

http://nbn-resolving.de/urn:nbn:de:0114-fqs160364.