Volume 18, No. 1, Art. 10 – January 2017

Researching the Dynamics of Birth Registration and Social Exclusion for Child Rights Advocacy: The Unique Role of Qualitative Research

Admire Chereni

Abstract: In response to the persistent problem of deficient birth registration, NGO-led coalitions in Zimbabwe are seeking to build a strong case for prioritizing universal birth registration. Beside efforts to amplify children's right to birth registration as defined in international rights conventions, these coalitions seek to construct a causal relationship between birth registration and social exclusion outcomes. The idea that the absence of birth registration intensifies social exclusion for children has become something of a mantra in birth registration activism, but despite the surveys conducted in Zimbabwe and other developing countries, data to demonstrate the dynamic interplay of birth registration and social exclusion are lacking. In this article I illustrate that qualitative research can bridge this gap and strengthen birth registration activism.

Key words: birth registration; child advocacy; content analysis; key informant interviews; lived experience; motivational frame; narrative; qualitative research; social exclusion

Table of Contents

1. Introduction

2. Child Advocacy and Birth Registration Activism in Zimbabwe

2.1 The notion of child advocacy

2.2 Birth registration advocacy in Zimbabwe

3. Study and Methods

3.1 Conceptual framework

3.2 Methods of data collection and analysis

4. Exploring the Dynamics of Birth Registration and Social Exclusion—An Illustration

4.1 Survey approaches in birth registration research

4.2 The potential of qualitative approaches in exploring birth registration and social exclusion

4.2.1 Case Study 1: Mai Taruvinga's struggle for legal documents

4.2.2 Analysis

4.2.3 Case Study 2: Musiyiwa

4.2.4 Analysis

5. Discussion and Conclusions

This article seeks to contribute to an emerging area in child advocacy in Zimbabwe—birth registration activism. In Zimbabwe networks comprising international non-governmental organizations (INGOs) and local interest groups are asking for universal birth registration. The rationale for such demands is very strong: in Zimbabwe only 38 per cent of children will be registered by their fifth birthday (ZIMSTAT, 2015). Proponents of universal birth registration recognize that in a country that is slowly recovering from a protracted political and economic crisis, expanding birth registration to every child requires the involvement of many stakeholders—including the government and grassroots (parents, caregivers, families, and communities). However, as I argue, a motivational frame suited to get all the allies and constituents involved in birth registration activism is missing from the picture. This has negative implications for the success of child rights activism in general and child birth registration activism in particular. [1]

Just as children's rights research uncritically adopts the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child (UNCRC, or simply the Convention) as the ultimate frame of reference (QUENNERSTEDT, 2013), birth registration activism tends to build its motivational frame on international children's rights discourse. The central plank of this frame is the child's right to a name, identity, and nationality, as enshrined in the Convention. The point often underscored in advocacy messages is that the state's failure to ensure that every birth has been registered, and that every child has a valid birth certificate, is a violation of children's human rights. Framing the lack of a birth certificate as a human rights violation is premised on the idea that children are "social actors, subjects in their own right, not merely objects of social concern or the targets of social intervention" (FREEMAN, 1998, p.440). Nonetheless, the transformative power of the assertion that children are people in their own right will more likely be neutralized by various context-specific notions of childhood which tend to deviate from the normative visions of the ideal childhood encapsulated in the Convention (see for example, BOURDILLON, 2011; MAYALL, 2000). Thus, as a motivational frame—a perspective of the problem facing children and policy options—the normative position on the rights of children is rather less appealing to the grassroots and other potential allies whose buy-in is necessary for effective advocacy and policy reforms. [2]

In response to what appears to be a rather apparent threat to the normative visions of childhood, or what Michael WABWILE (2010, p.381) characterized as an "international legal order aimed at facilitating universal fulfillment of [children's] rights," birth registration advocates underscore the short- and long-term social exclusion impacts of a child not having a birth certificate. Connecting birth registration and social exclusion outcomes in a causal way is useful for reframing the challenge of birth registration around which advocacy might progress. [3]

A central concern of this article, however, is that there are no sufficient data to demonstrate the dynamics of birth registration and social exclusion. This need not imply that research on birth registration and deprivation in Zimbabwe does not exist. Aspects of birth registration have been explored in a number of regular surveys in Zimbabwe, including the Census, Multiple Indicator Cluster Survey (MICS), and the Demographic Health Survey (DHS). In all fairness, surveys generate important insights into the magnitude of deficient birth registration and some of the conditions which might determine certain birth registration outcomes. For example, household wealth is one of the factors associated with positive birth registration outcomes. Still, I contend that existing surveys hardly show how multiple dimensions of deprivation interact with birth registration outcomes. Consequently, for birth registration activists, the job of convincing potential stakeholders that birth registration is a problem requiring priority attention remains challenging. Even more difficult is convincing policy makers and the grassroots to support specific policy reforms. [4]

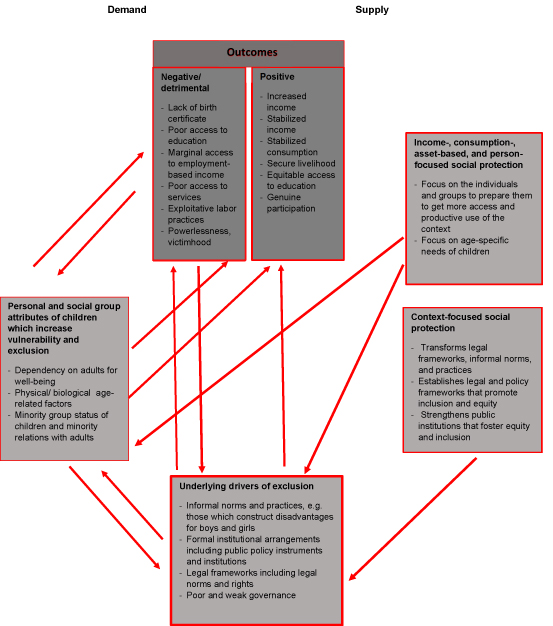

In this article, I suggest that qualitative research can trace interconnections of personal, social, and institutional barriers to birth registration, and generate data that are conveniently usable in birth registration advocacy. I provide a rationale for using qualitative interviews and demonstrate the utility of narrative approaches. Examples are drawn from a mixed-methods study of birth registration and child-sensitive social protection conducted in the Bindura district in the Mashonaland Central province in Zimbabwe. After the introduction, I review concerns in child advocacy and provide background information on birth registration activism in Zimbabwe (Section 2). Thereafter follows a discussion of the mixed-methods study from which this article draws (Section 3). This section focuses on the concepts and methods used to guide the study. It precedes the section which elaborates the central idea advanced in the article—that stories shared by interviewees have immense potential for capturing the dynamics of birth registration and advocacy (Section 4). In it, the ways in which descriptive statistics and narratives were used to explore the dynamic interaction of birth registration and dimensions of exclusion are discussed. The rationale and potential of narratives are illustrated in this section. Finally, a concluding section which underscores the insights elaborated upon in the text is provided. [5]

2. Child Advocacy and Birth Registration Activism in Zimbabwe

2.1 The notion of child advocacy

In a review of meanings and practices of advocacy in the field of social work, I observed that the notion of advocacy is often elaborated upon in terms of binaries as in case vs. cause advocacy and passive vs. active advocacy (CHERENI, 2015). For case advocacy, the advocate represents the rights and interests of an individual or a small group of people. However, the advocate seeks to bring about widespread changes in the norms, legislation, and policies which have a bearing on people's well-being. Passive advocacy and active advocacy can be viewed as opposite ends of an empowerment continuum. In the former, the individual (or even social group) is less empowered and relies on the advocate to promote his or her cause. In the latter, however, the individual speaks on his or her own behalf. The passive-active binary suggests that empowerment is the ultimate goal of advocacy. To a larger extent, this view is relevant in child advocacy where children—the subjects of advocacy—are typically seen as those who lack the necessary competence to make decisions (FREEMAN, 1998). Thus, although advocacy is a rather "polysemous concept" (CHERENI, 2015, p.3), it is fair to assert that the notion captures the processes, practices, and outcomes of speaking to and on behalf of an individual or groups of people. [6]

However, as Michele CASCARDI, Cathy BROWN, Svetlana SHPIEGEL and Ariel ALVAREZ (2015) argued, child advocacy is a distinct field and therefore has a particular meaning. From the perspective of these authors, the goal of child advocacy is to empower children by promoting their "self-expression and participation" (p.5; emphasis added), while taking cognizance of the fact that the empowerment of children is contingent upon the well-being of families and communities in which they grow. One is then made to think that both case and cause advocacy are equally important for child advocacy. Responding to a few cases of child maltreatment is necessary and urgent since it ensures the continued provision of services to those children. Similarly, seeking to change cultural and legislative norms that perpetuate children's vulnerability in society is important. [7]

However, in order to appreciate child advocacy and its dimensions, it is instructive to critique some of the key discourses which, historically, have constructed children's subordination to adults. Historically, as Michele CASCARDI et al. observed, the Enlightenment and Romantic periods, with their characteristic debates around the notions of paternalism and childhood, have had significant purchase on children's status in society. Childhood came to be understood as a less indistinct socially constructed phase of life, while children were typically deemed vulnerable, powerless, and lacking competence for autonomy (see also FREEMAN, 1998). This view of childhood and children justified adult paternalism—an ideology whereby adults and institutions of society assume the "duty to protect and decide what is best for [children] in society, with little regard for [their] own preferences or autonomy" (CASCARDI et al., 2015, p.2). These ideas have structured adult engagement with children in the arenas of policy making and practical responses to child maltreatment in the United States and abroad. For example, coupled with values and assumptions about the best interests of the child, the ideology of paternalism has inspired a kind of child advocacy which emphasizes protection at the expense of participation of children (ibid.; see also FREEMAN, 1998). [8]

And yet, while agreeing that ideological, theoretical, and values-based constructions do structure societal responses to child maltreatment, Berry MAYALL's (2000) treatise on the sociology of childhood and children's rights suggested that the construction of children's subordinate status is certainly not restricted to a particular epoch or even domain. Far from it, the "familialization, individualization, and scholarization" of childhood which work to maintain children's inferior status are ongoing institutionalized processes. By familialization, MAYALL (p.250) denoted societal action to ensure that children grow up in an ostensibly apolitical, private, domestic, and happy sphere where they "develop, unmolested by the stresses of public life." By this account, the notion of a child is conflated with that of family (and mother). Moreover, positive child outcomes are largely, if not solely, dependent on particular visions of family. Scholarization captures the entrenched belief that quality companionable learning (ROBERTS, 2010) occurs solely when children perform activities as pupils, and not as paid workers. Individualization captures the predominance of case work (focusing on the individual needs of the child) in responding to children's maltreatment. According to MAYALL (2000), these ideas have shaped a social order characterized by an enduring adult-child division where children are deemed vulnerable, defenseless, incompetent, and inadequate versions of adults needing adult socialization. [9]

From the work of CASCARDI et al. (2015), MAYALL (2000), and others (see for example, JAMES, 2007), one finds that for child advocacy, confronting and deconstructing perspectives that work to position children as inferior to adults is a top-priority task. Berry MAYALL's (2000) treatise is, nevertheless, more informative. From her work one can deduce that politicizing childhood is a move with critical, theoretical, and practical importance for child advocacy because, first and foremost, enduring processes of familialization, individualization, and scholarization, among other things, have framed childhood as a politically neutral conceptual space (ibid.). Thereby perspectives of childhood and children preclude meaningful critical engagement with the assumptions that underpin societal responses to child maltreatment. It seems to me that Berry MAYALL's work is an important exercise in deconstruction; it implicates those perspectives, theories, and the conceptual vocabulary that adults have framed for children in adult politics. Consequently, unlike CASCARDI et al. (2015), who tend to theoretically conflate child empowerment with family well-being, MAYALL appears to claim that for academics and activists alike, a necessary first step for child-empowerment work is actually "to rescue children and childhood from a conceptual space that has been declared apolitical" (2000, p.247). The priority task in child-empowerment work, then, is to disentangle childhood from family in order to position children as a unique (MAYALL, 2000), though not heterogeneous social grouping (JAMES, 2007). This is what child advocacy seeks to achieve in the first place. [10]

The next section provides a background discussion on advocacy for universal birth registration in Zimbabwe. [11]

2.2 Birth registration advocacy in Zimbabwe

Birth registration activism is a nascent area of child advocacy. Nonetheless, it is possible to identify some of its basic characteristics. As in other countries, NGO-led advocacy around birth registration in Zimbabwe has assumed what Paul NELSON and Ellen DORSEY (2007) termed "New Rights Advocacy" (NRA). The tenets of NRA can be summarized as follows:

Reliance on international human rights standards influence social and economic justice in domestic settings. Child-serving organizations tend to draw extensively on human rights discourses circulating in international circles.

However, organizations involved in NRA experiment with other approaches to meet the ends of social and economic justice; including litigation, research, and documentation.

Child-serving organizations tend to draw on social and economic rights for their motivational frames.

Human-serving organizations that use NRA maintain a less straightforward relationship with Global South states. Sometimes they collaborate with Global South governments, often under the guise of ensuring the sustainability of programs after the eventual withdrawal of foreign funding. In so doing, these organizations reinforce the sovereignty of the Global South states. At times, however, they condemn recalcitrant states, assuming more confrontational undertones in their messages, while adopting more adversarial tactics. [12]

In relation to advocacy for birth registration, one finds visible issue networks or coalitions of child-serving organizations in Zimbabwe that seek to perpetuate an international legal normative order where children's rights are realized (WABWILE, 2010). The cast of children's rights defenders that promote birth registration in Zimbabwe comprises the United Nation’s family of agencies ostensibly led by UNICEF, INGOs such as "Save the Children and Plan," as well as a multiplicity of child-serving organizations and civic interest groups. Academics domiciled in local universities are joining this loose coalition. The UNICEF-funded "Child-Sensitive Social Protection" (CSSP) program at the Women's University in Africa is a case in point. Among other things, the program collects data on multiple indicators with the goal of monitoring the country's progress toward the realization of children's rights—including birth registration. Rather than taking an adversarial stance against the government, the CSSP program seeks to build coalitions with government authorities as a precondition for successful policy reforms. [13]

Other advocacy activities in the broader civil society have assumed a more confrontational stance, suggesting that the tactics used in children's rights activism are not necessarily limited to collaboration. For example, in 2011, Save the Children and other organizations generated a periodic review which summarized Zimbabwe's progress in eliminating child maltreatment, particularly children's lack of birth certificates, through the formulation and implementation of legislation and policy. Although the consequences of such domestic and international activism are not easy to tell, it is possible to think that the periodic review sought to mobilize shame so as "to appeal to international authority to force changes in domestic human rights policy" (NELSON & DORSEY, 2007, p.192). This situation confirms the authors' assessment that human service organizations which adopt NRA tend to adopt a pragmatic posture—trying out different ways of bringing about policy reforms. [14]

For example, apart from strategies that seek to mount pressure on the government to install and implement policies that encourage universal birth registration, some child-serving organizations have begun to provide child services to deserving households with certain conditions. Acquisition of a birth certificate for the deserving child is one of the conditions households should meet to ensure continued access to targeted social protection benefits. In collaboration with the Government of Zimbabwe, UNICEF is trying out a number of conditional cash-transfer programs which explicitly aim to improve birth registration for orphaned and vulnerable children under the age of five years. These programs target ultra-poor households—especially those that are severely labor constrained—to increase child outcomes, including birth registration (UNICEF & MINISTRY OF LABOUR AND SOCIAL SERVICES, 2011). [15]

In line with Paul NELSON and Ellen DORSEY's (2007) conceptualization of NRA, children's rights defenders advocating universal birth registration tend to rely, rather uncritically, on children's human rights discourses in the international arena in order to move governments to action. Indeed, while making the case that countries which lag behind in expanding birth registration to all children are violating the rights of unregistered children, the NGO-led coalition adopted the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child (UNCRC) and other international conventions as the ultimate frame of reference for children's human rights, without questioning its universal applicability (QUENNERSTEDT, 2013). For example, at relevant meetings and workshops, members of the NGO-led coalition in Zimbabwe tend to amplify Article 7 of the UNCRC, which states that every child "shall be registered immediately after birth" (UNITED NATIONS, 1989, as cited in UNICEF, 2002, p.3). Article 24 of the United Nations International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR) is also cited to achieve similar ends. Adopted by the General Assembly in 1966, Article 24 states that "every child shall be registered immediately after birth and shall have a name" (cited in UNICEF, 2002, p.3). [16]

Still, those engaged in birth registration advocacy are conscious of the fact that to simply rehash children's rights in international conventions does not seem to provide an effective motivational frame to garner the support of various influential actors in society, especially the grassroots. Subsequently, proponents of universal birth registration seek to advance the argument that denying a child his or her right to birth registration intensifies that child's social exclusion throughout the life cycle. Understood as a state of ultra-deprivation and non-participation in normatively prescribed domains of society—including education, sport, and the labor market (HOBCRAFT & KIERNAN, 2001)—social exclusion maintains children in a perpetual state of invisibility, inaccessibility, and anonymity in policy circles. Throughout childhood, the argument goes, a child may not legitimately access social and child protection services necessary for well-being (UNICEF, 2013). Strictly speaking, he or she is not a target for social protection because his or her existence is not known to social planners in the first place. Birth registration therefore is the right to have rights, without which children may not effectively exercise their economic and social rights and political freedoms. [17]

So, drawing on the international legal normative framework, proponents of universal birth registration in Zimbabwe have connected child poverty with birth registration, presenting the latter as a predictor of the former (ibid.). Nonetheless, relying on international human rights discourses to frame a motivational perspective for advocacy has become the Achilles' heel of birth registration activism in Zimbabwe. According to Barbara KLUGMAN (2011), a motivational frame for advocacy could be more effective if augmented with research which, in this case, demonstrates the interaction between birth registration and social exclusion. Yet, while big-sample surveys such as the "Multiple Indicator Cluster Survey" (MICS) and the "Demographic Health Survey" (DHS) have been regularly used in Zimbabwe to explore child outcomes—including birth registration—data to persuasively illustrate the dynamic interplay of birth registration and social exclusion are largely unavailable. [18]

Therefore, there is a need to complement statistical models and measures with qualitative approaches in order to generate readily usable data to construct motivational frames that are equal to the task of moving people "to take action, making them want to get involved" (KLUGMAN, 2011, p.157). The following sections illustrate how qualitative research can be used to augment existing quantitative studies in ways that strengthen child advocacy. [19]

The insights examined in this article were generated from a mixed-methods study titled "Birth Registration and Child-Sensitive Social Protection: A Case of Bindura District in Zimbabwe." The objectives of the study were threefold. Firstly, the study sought to document the experiences of unregistered children with regard to access to and exclusion from social services and legal protection. Secondly, it aimed to explore the nature of inclusion of unregistered children in social services and benefits. Lastly, the study attempted to develop recommendations for good practice models for an effective response to issues of unregistered children. [20]

In any scientific study, there is a need to create a bridge between abstract constructs and empirical phenomena (ADAMAS & BEUTOW, 2014). A conceptual framework provides that bridge; it helps the researcher to decide the kind of literature to consider, the variables and concepts to examine, and suitable methods to follow (LESHEM & TRAFFORD, 2007). The conceptual framework helps the researcher to "preview" what is going on in the field (MAXWELL, 1996). In keeping with these methodological insights, Ann QUENNERSTEDT (2013, p.241) argued that a conceptual framework is necessary to "understand the complexities surrounding the realization of children's human rights in various societies and parts of society." [21]

In order to make sense of birth registration and social exclusion in connection with children's access to social protection, the categories of social exclusion, social protection, child-sensitive social protection, and birth registration require explication. Social protection describes responses by public, private, and voluntary organizations and informal networks that are designed to strengthen the capacity of communities, households, and individuals to sufficiently respond to loss of income and assets and risk and vulnerability which emerge in an environment of poverty (ROELEN & SABATES-WHEELER, 2012). Among children, social protection can take the form of universal and categorical provision where all children in a country, region, or defined group benefit. Furthermore, social protection can assume the form of targeted social provision where selected children receive benefits. [22]

Social protection is designed to have a positive impact on the outcomes and drivers of social exclusion (BABAJANIAN, 2013). For example, the focus of social protection programs such as school fee waivers, school feeding programs, and free oral care is to ensure education, nutrition, and health outcomes. Conditional cash transfers that specify acquisition of the potential beneficiary's birth certificate as one of the conditions of the continued flow of benefits will more likely ensure positive birth registration outcomes. Birth registration can also fit in the social protection category since it contributes to children's access to and exercise of social and economic rights. [23]

Thus, social protection programs can improve specific child outcomes. But as Babken BABAJANIAN observed, a social protection program cannot have positive effects on all dimensions of deprivation and well-being. For example, a school feeding program may not successfully address other dimensions of well-being such as confidence, self-esteem, and internal locus of control due to the stigma associated with such programs. Therefore, it is possible that, depending on the design, social protection programs for children may perpetuate negative birth registration outcomes. [24]

In thinking about social protection and social exclusion, it is pertinent to reiterate that social protection programs are meant to address the outcomes and drivers of social exclusion (BABAJANIAN & HAGEN-ZANKER, 2012). These outcomes include multiple dimensions of deprivation as well as underlying drivers. Since social protection responds to the outcomes and drivers of social exclusion, one can identify two sides of social welfare programming, namely demand and supply. In the study on which this article is based, two categories of social protection were identified on the supply side. First, there is a group of social protection programs that are income-, consumption-, and asset-based, and person-focused in orientation. These respond to vulnerability, that is, the reduced capability of an individual to anticipate, cope with, and withstand the effects of risk. Therefore, the overriding goal of this category of social protection is to enhance individuals' capacity to manage risk and make the best use of the context in terms of constructing livelihoods and well-being (ROELEN & SABATES-WHEELER, 2012). The second category of social protection programs constructs vulnerability as an aspect of the environment. By this account, vulnerability can be addressed by transforming legal and policy frameworks, as well as informal norms and practices which produce and reproduce social exclusion for some groups of people. [25]

At the core of debates about child-sensitive social protection is the idea that despite the diversity of the contexts of care and registration status, children's vulnerability is child-specific and child-intensified. This idea implies that children tend to experience vulnerability differently than adults. On top of that, the impacts vulnerability has on children are often long-term and irreversible in nature (ibid.). As hinted at above, just as drivers of deprivation and vulnerability potentially give rise to social exclusion outcomes, supply-side social protection initiatives designed to construct social protection for children may aggravate social exclusion outcomes. These aspects of social protection and social exclusion are illustrated in Figure 1. Also in Figure 1, birth registration is conceived of as an outcome of a complex interplay of social protection, household agency, and multiple drivers of social exclusion. Nonetheless, as Babken BABAJANIAN and Jessica HAGEN-ZANKER argued, the complexity of social exclusion dynamics is such that outcomes may be transposed with drivers. This suggests that birth registration may be viewed as both an outcome and a driver of deprivation.

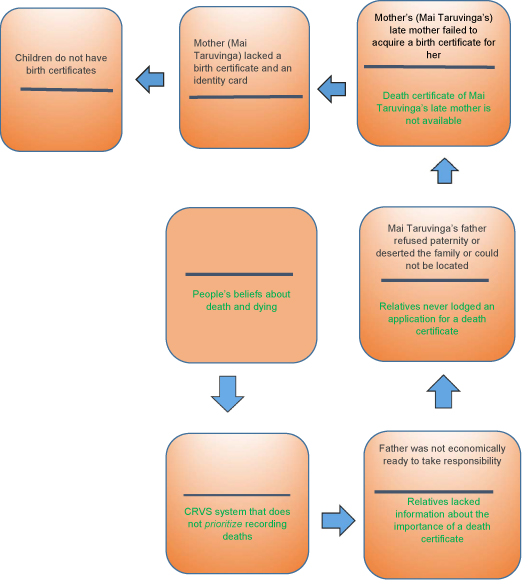

Figure 1: A conceptual framework of birth registration and social exclusion outcomes [26]

3.2 Methods of data collection and analysis

The study on which this article draws adopted a mixed-methods design comprising a questionnaire survey and qualitative interviews. The survey included representatives of 105 households in three different wards in the Bindura district1). Questionnaire respondents were typically parents and guardians of children who were responsible for the care of dependent members of the household on a daily basis. Apart from the questionnaire, explorative semi-structured interviews (KVALE, 2007) with five key informants were also used to produce qualitative data. The key informants were purposefully selected (GUETTERMAN, 2015) based on their potential to provide unique viewpoints about birth registration. All key informants had dealt with children's issues in different capacities; for example, as government officials, community leaders, and care givers. Importantly, key informants related to the topic of birth registration at a more personal level, hence their accounts were generated with minimal probing. For this reason the personal narratives complied with some of the standards of using told stories in narrative research (JONES, 2003). [27]

Directed content analysis, one of the approaches to thematic content analysis (HSIEH & SHANNON, 2005), enabled some form of comparison between the told story and the lived experiences of the participants, in ways that generated social meaning. The method enabled me to apply the conceptual vocabulary in the conceptual framework to the interview data in ways that generated relevant categories, including chronological patterns, as well as the dynamic interplay of various constituents of the storyteller's social life. For example, directed content analysis revealed connections between negative birth registration outcomes and multiple underlying dimensions. However, it is important to note that not all categories were generated prior to fieldwork. Directed content analysis accommodates new categories in order to generate rich analyses of the interviewees' stories. To understand and visually display the connections between birth registration and social exclusion outcomes as well as other categories of interest, I employed perceived causal pathways. The term "pathways" is typically used to represent causal conceptions in explanations of reality (BERENZON GORN & SUGIYAMA ITO, 2004). In this article, I use perceived causal pathways as part of social constructionism in which the interviewee assumes an active role in the construction of reality (ibid.). In order to generate perceived causal pathways, I occasionally prompted the interviewee to explain by asking "why." [28]

While this article focuses on the qualitative aspects of the study, I believe that including some of the pertinent details of quantitative sampling will increase methodological clarity. In keeping with the need to construct a representative sample, the study adopted a multi-stage random sampling approach. First, enumeration areas2) (EAs) that had scored the highest occurrence of incomplete birth registration in Bindura in the Multiple Indicator Cluster Survey (MICS) of 2014 (ZIMSTAT, 2015) were randomly selected. In the next stage, the EAs were stratified according to settlement and land-use patterns. Four main strata emerged; namely rural-communal areas, urban areas, mining areas, and resettlement areas. The stratum of resettlement areas included former white-owned commercial farms that were divided into smaller A1 plots and distributed to black farmers after 2000. Eventually, five EAs were randomly picked and within each EA, households were randomly selected. Table 1 communicates the outcome of the sampling procedures, as well as the number of households chosen in each EA.

|

EA |

Ward |

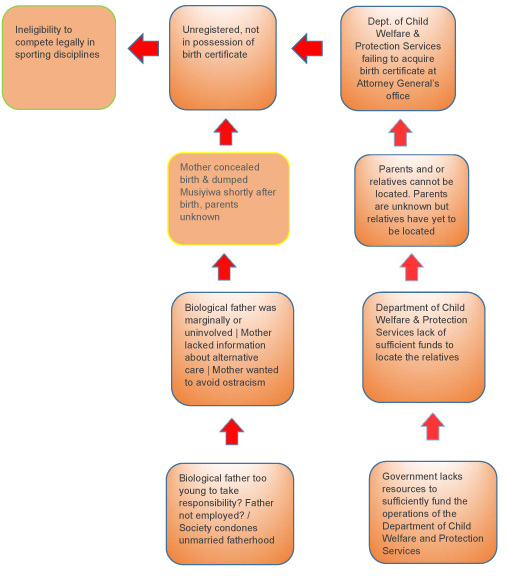

Settlement and major land-use characteristics |

Households |

|

110 |

08 |

Post-2000 resettlement area, rural, farming |

15 |

|

060 |

10 |

Communal area, rural, farming |

13 |

|

050 |

09 |

Urban, high to medium density |

27 |

|

010 |

01 |

Urban, low density, mining |

25 |

|

061 |

04 |

Urban, high density |

25 |

|

Total |

number |

of households |

105 |

Table 1: The distribution of selected households by EA [29]

4. Exploring the Dynamics of Birth Registration and Social Exclusion—An Illustration

This section makes the case for the use of qualitative approaches in advocacy-oriented research. It first illuminates the shortfalls of survey approaches in understanding the dynamic links between birth registration and social exclusion. Then it examines how a qualitative approach can aid research into birth registration and social exclusion. Stories told by participants are used to illustrate the role of qualitative research in making visible the interconnections between personal, self, and institutional (see for example, DE TONA, 2006). [30]

4.1 Survey approaches in birth registration research

Thus far, birth registration research in Zimbabwe and other developing countries has relied on the quantitative survey method. However, despite their popularity, quantitative surveys on birth registration have largely remained descriptive, emphasizing analyses of co-relation between selected variables and birth registration outcomes, rather than causality (see for example, PELOWSKI et al., 2015). For example, better birth registration outcomes are known to have a strong correlation with household access to a regular income. Similarly, the level of education of the parent or caregiver is strongly associated with improved possession of a birth certificate. Consequently, existing survey research argues that income poverty and low levels of education are some of the barriers to successful birth registration. [31]

Still, such conclusions do not sufficiently demonstrate the link between birth registration outcomes and social exclusion. The study on which this article draws illustrates the limits of descriptive surveys in addressing the causal dynamics of social exclusion and birth registration. When asked to explain why they have yet to acquire birth certificates for all children, participants identified various obstacles to birth registration. Table 2 presents the barriers; ranked in terms of the frequency by which they were mentioned by the participants.

|

Reason |

% |

|

Distance and mistake on birth certificate |

1 |

|

Born out of the country |

1 |

|

Lack of information |

1.9 |

|

No longer interested |

2.9 |

|

Insufficient papers |

2.9 |

|

Officials declined / turned back/away |

2.9 |

|

Procrastination |

3.8 |

|

Delivered at home |

4.8 |

|

Parents divorced/separated |

7.6 |

|

Parent(s) deceased / Whereabouts unknown |

7.6 |

|

Costs |

12.4 |

|

Not applicable |

50.5 |

|

Total |

100 |

Table 2: Perceived barriers to birth registration [32]

From Table 2 one appreciates that the barriers to birth registration form a mixed package, with various types of personal effects in it. One finds personal factors such as attitudes and motivation; cultural and social factors, including death and divorce; and economic factors, where the cost is the major impediment to birth registration. Still, activists wanting to frame appealing advocacy messages may find it difficult to connect personal barriers—such as "lack of interest," "procrastination," and poor information-seeking behavior—with institutional constraints to birth registration. There is therefore a need to capture the complex processes by which various personal and structural factors interact over time to produce birth registration outcomes. [33]

Quantitative designs such as "Randomized Control Trials" (RCTs), hypotheses testing, and the use of models can potentially establish causality, and can reveal the interplay of personal, social, and institutional factors (PALINKAS, 2014). However, while such quantitative approaches are driven by the need to achieve a high level of precision and accurately attribute causality, in most cases the causes of an outcome are multifactorial. In other words, numerous factors are necessary for a certain birth registration outcome, but not all of them sufficiently determine the outcome of birth registration in all individual cases. Furthermore, surveys are generally time-consuming and require huge amounts of financial and human resources. [34]

4.2 The potential of qualitative approaches in exploring birth registration and social exclusion

Although some scholars argue that all methods of attributing causation have inherent weaknesses (ibid.), this section demonstrates that qualitative approaches can generate readily usable data that are relevant for mobilizing both the collective recognition and a standardized articulation of the problem of deficient birth registration in Zimbabwe. Furthermore, trade-offs can be made between precise measurement vis-à-vis participants' views which provide the "real-life" stories behind numbers. [35]

Still, seeking to popularize qualitative approaches in an area where surveys have been predominant will more likely face resistance. Consequently, a reasoned argument for the adoption of qualitative approaches in research about birth registration and social exclusion is in order. The rationale for making better use of qualitative research in studying birth registration and social exclusion outcomes can be mobilized from various fields of scholarship, but two seem to be particularly relevant. Writings about the heuristic and analytical potential of "narratives," "life stories," "told stories," and "qualitative interviews" for generating insight into people's experiences constitute the first field. The principles underlying Robert CHAMBERS' (1994) work on "Participation, Rural, and Appraisal (PRA) represent the second field. As the reader might appreciate, PRA tools and principles were developed in isolation from the rising popularity of personal narratives and qualitative interviews as approaches for generating data to understand social experience. However, a combination of the two broad approaches and techniques, I argue, provides a more solid rationale for using qualitative approaches to pin down social dynamics of birth registration outcomes and social exclusion. [36]

The interview between Carla DE TONA, Ronit LENTIN, and Hassan BOUSETTA (DE TONA, 2006, §12) cogently illustrates the potential of qualitative research in understanding social dynamics:

"[T]he story of one life tells a lot about society, not only about that person. If you listen well to a life story, to how people narrate, you actually learn a lot about transition, about change, about social reproduction, about political structure, about the relation between the state and the individual, the relation between the genders, social classes and between races or ethnic groups. [The story] is actually a very rich source of material." [37]

According to Carla DE TONA, one person's narrative potentially deepens our understanding of underlying processes of transformation and marginalization which produce gender and political orders through relations of power. This implies that the stories people tell can reveal how birth registration is implicated in multiple processes of marginalization. Carla DE TONA's views echo Prue CHAMBERLAYNE and Annette KING's (2000, quoted in JONES, 2003, p.60) observation that biographical research tools are strategically suited to explore subjective and cultural formations, making visible the interconnections of the personal and social. Kip JONES (2003) further observed that when exploring the concerns of participants, life stories and narratives transcend the limits of the self and society. A life story reveals how structural and institutional arrangements exert influence on a person's life, constraining his or her options. Conversely, a story makes visible the feelings, aspirations, frustrations, and efforts that people devise as they seek to construct human well-being. In other words, agency—that is, how, through their actions, individuals achieve desired improvements in their life conditions—is revealed in the stories people tell. Hence the story reveals the social life masked by statistical models and numbers. [38]

Interviewee accounts arguably establish causality; they make visible how various constituents of the interviewee's social experiences are connected. Although in-depth qualitative interviews generate subjective perceptions of the interviewee's situation and circumstances, they also illuminate social meanings (ibid.). It is undeniable that the interviewee's told story constitutes "constructed versions of the social world" (CROUCH & McKENZIE, 2006, p.485) since the interview participant organizes themes and sections of the interview, electing to adopt or leave out some details as he or she tells the story. However, epistemologically speaking, the respondent's point of view is the window through which the researcher can access that person's experience. Furthermore, such experience is accorded the status of reality (JONES, 2003). [39]

Nonetheless, it is necessary to point out that, in order to make sense of that reality, the social context in which social experience is embedded should be analyzed. It is through in-depth analyses—which invariably require theoretical elaboration—of the conditions in which social experience unfolds that causality is attributed. According to CROUCH and McKENZIE (2006, p.486), the interviewee's experience is "imbricated in a social milieu which is ontologically prior to both the respondents' and the interviewers' actions, and therefore causally related to them." This implies that the interviewee's lived life or the social life influences the told story. Moreover, certain conditions in the context of the lived experience tend to shape the interviewee's told story about birth registration and social exclusion. When subjected to in-depth text analyses, interviewee narratives can illuminate chronological patterns in an individual's social life. Despite the fact that the interviewee constructs the order and themes of the life story during the encounter with the researcher, the interview account is, in most cases, presented as a chronological chain of events (JONES, 2003). Sets of events are causally related to others since some events always occur prior to others. In other terms, some events almost always follow others in a given temporal space. For example, marriage and birthing experiences precede the acquisition of a birth certificate for the baby. Events that make up one's marriage and birthing experiences influence birth registration and social exclusion outcomes. [40]

Apart from the heuristic and analytical value of personal narratives, Robert CHAMBERS' (1994) ideas on PRA provide a strong rationale for the use of qualitative approaches in advocacy-oriented research in birth registration. According to him, PRA and its earlier versions—Rapid Rural Appraisal (RRA)—were developed partly in response to the "many defects and high costs of large-scale questionnaire surveys" (p.1253). While the procedures, techniques, and tools of PRA are largely tangential to the current discussion, the underlying principles are very informative. The first principle, optimal ignorance, is about determining what is not worth knowing for effecting policy reforms, and not researching it. Avoiding what is not worth knowing for birth registration activism will save money while helping to generate evidence in a timely fashion. The second principle from Robert CHAMBERS' work is appropriate imprecision, which refers to not measuring what is unnecessary to measure. Again this saves the time that coalitions spend on data collection and problem definition. If there is one key lesson to be learned from Robert CHAMBERS' principles of PRA, it is the need to adopt a strategic stance when conducting research to support the advocacy effort of civil society coalitions. There is no need to rely solely on sophisticated quantitative analyses to generate appropriate campaign messages to fit into a specific advocacy strategy if interviews are equally effective. This need not imply that qualitative interview protocols require less intellectual and theoretical investment. Rather, the point emphasized here is that activists may find the work of translating the scientific language and formats used in reporting results of quantitative surveys into a viable frame daunting. Since, as observed, qualitative approaches reveal the life behind the numbers, one is inclined to think that personal narratives do generate readily usable accounts. [41]

Another principle of interest here is maximizing diversity by purposively selecting case studies. Seeking diversity implies that qualitative research for advocacy may concentrate on exposing the outliers—those cases that illustrate both the worst-case scenarios and the desirable outcomes. [42]

The following section first presents birth registration accounts told by two participants. Since the participants were motivated to talk about their struggles with birth registration, one can assert that the manner in which the stories were generated complies with the principle of eliciting open-ended narratives with very little probing (JONES, 2003). [43]

4.2.1 Case Study 1: Mai Taruvinga's struggle for legal documents

When doing fieldwork in a resettlement area in Bindura, I considered that Mai Taruvinga's household was rather outstanding, at least in terms of the acquisition of birth certificates for the children. What I found remarkably extraordinary about Mai Taruvinga's household was the fact that although she lived on a remote farm, none of her children lacked a birth certificate. [44]

As I looked at her with immense curiosity, I could not help but probe her to tell me how she managed to obtain birth certificates for all four her children. She continued to gaze at the bare earth on which she sat and retorted in a soft manner, "It was a miracle." Then, after a pause, she looked up at me as if she was searching for any verbal cues to confirm my belief in miracles before she went on. Mai Taruvinga's account of her struggle to obtain papers was quite revealing. Until mid-2013, she neither possessed a birth certificate nor a national identity card. Her four children also did not have birth certificates but they were enrolled in school––thanks to the school authorities who understood their plight. [45]

Mai Taruvinga could have acquired birth certificates and other documents for herself and her family a long time ago but she could not overcome one obstacle, she confessed. The Registrar General's Office required Mai Taruvinga's late mother's death certificate before they could accept her application for a birth certificate. When explaining why getting her late mother's death certificate issued was a necessary step in the birth registration and certification, she began with a confession, "I do not know my father." Mai Taruvinga's parents, I learned, had either divorced before she was born or her father had refused paternity. Consequently, Mai Taruvinga had to adopt her maternal family name at school. However, she only went as far as the sixth grade before she dropped out. [46]

At some point, Mai Taruvinga's mother attempted to acquire a birth certificate for her. Her efforts were shattered when she failed to locate the father. Mai Taruvinga suspects that she might have located her father but he was simply not forthcoming. To say Mai Taruvinga's mother gave up trying to acquire her daughter's birth certificate is not an exaggeration, I learned. As time went on, Mai Taruvinga decided to start her own family, taking the customary marriage route. Since most customary marriages are not registered at the Registrar's Office, Mai Taruvinga had little incentive to acquire her birth certificate and national identity card when she married her husband. Because she did not have legal documents, she could not apply for her children's birth certificates. [47]

Then one day, Mai Taruvinga's mother died in her sleep. No one could have guessed the cause of death since she had no history of known illnesses. Mai Taruvinga's mother was buried the next day. No autopsy was done. After a few months, the belongings of Mai Taruvinga's mother were shared among close relatives according to the Shona traditional custom3). [48]

When Mai Taruvinga's son started Grade 7, she realized that a birth certificate was needed to register his candidacy for public examination in that school year. At that time she knew that she had no option but to pursue all the necessary legal documents for her family. The starting point was to lodge an application for her mother's death certificate. Speaking about the application procedure for the death certificate she said, "It's never easy." After the initial application, Mai Taruvinga, her brother, and her 14-year-old son each visited the Registrar General's Office twice to follow up. Mai Taruvinga informed me that each time she followed up at the Registrar General's office, she had to walk more than eight kilometers to reach the main dirt road to get a shuttle to the Registrar General's Office in Bindura at a cost of US$6 per return trip. [49]

She disclosed that, at some point, one of the officials at the Registrar General's Office asked for a bribe in order to fast-track the application for the certificate. Still another official, Janet, a woman in her mid-thirties, found out about it and vowed to help her. That is how Mai Taruvinga acquired her mother's death certificate, her own birth certificate, and a national identity card. Janet wrote official letters to relevant authorities to help Mai Taruvinga access birth notification papers and other documents required to apply for a birth certificate. As soon as the birth notifications and other documents were available, Janet processed Mai Taruvinga's application for birth certificates on the same day. This is Mai Taruvinga's miracle: to be in possession of birth certificates for all her children. [50]

This made her household considerably extraordinary. In terms of accommodation, however, Mai Taruvinga and her children were not in any sense unique. Not unlike her neighbors, they lived in a brick-and-mortar house located in a compound, which formerly belonged to a white commercial farmer. Until the fast-track land reform program in the early 2000s, when the government apportioned his farm to scores of A1 African farmers, the white farm owner had housed his farm workers in the compound. [51]

A thematic content analysis of Mai Taruvinga's narrative generates a number of insights about birth registration and social exclusion. [52]

Through in-depth thematic content analysis, it is possible to identify various constituents of the participants' social lives, and how they interact to influence birth registration and social exclusion outcomes. Thematic analysis of narratives makes visible the conditions within which the situation of non-possession and birth registration unfolds. When closely examining the personal narrative presented above, the interplay of the multiple barriers which give rise to negative birth registration outcomes emerge. Table 3 below summarizes the multiple barriers which affected Mai Taruvinga's initial situation of non-possession of birth certificates.

|

Micro-level factors |

Macro-level factors |

|

|

Personal attributes and interpersonal/relational factors |

Informal norms and practices |

Institutional factors |

|

Low levels of parents' education; income poverty; parents' lack of birth certificates, lack of death certificates to prove death of a parent; death, conflicts over paternity, unmarried fathering, lone parenting; lack of knowledge; and attitudes toward death registration. |

Shared beliefs and practices associated with death and dying; and shared expectations of fatherhood. |

Cumbersome procedures for acquiring requisite vital documents; transactional costs; weaknesses of the central registrations and vital statistics system regarding registering deaths and causes of death; complacency of Registrar General officers; and alleged corrupt tendencies |

Table 3: Barriers to successful registration for Mai Taruvinga's family [53]

Apart from establishing the conditions which gave rise to the situation of non-possession of a birth certificate, which was the subject of the encounter between the interviewee and the researcher, the narrative communicates the chronology of events as they unfolded over time. Importantly, in telling these events, Mai Taruvinga implicitly or explicitly attributed a causal relationship between them. For example, she seemed to suggest that her father's situation of unmarried fatherhood influenced her chances of possessing a birth certificate. Since Mai Taruvinga presented her life story chronologically, it is possible to construct a perceived causal pathway of events:

Figure 2: Barriers to successful registration for Mai Taruvinga's family [54]

The perceived causal pathway presented in Figure 2 can answer the question of why her children did not have birth certificates prior to mid-2013. Figure 2 combines two pathways. It shows that Mai Taruvinga's lack of a birth certificate and a national identity card can be explained by different pathways (black vs. green highlighting). An interesting perceived causal connection is the relationship between the availability of a deceased parent or relative's death certificate and the possession of a birth certificate among descendants. The perceived causal connections among shared beliefs about death and dying, people's propensity to apply for a deceased relative's death certificate, and the existence of a Civil Registrations and Vital Statistics System (CRVS) system that fails to prioritize registration of deaths, are equally interesting. [55]

In Mai Taruvinga's story, one finds that economic dimensions were entangled in non-economic facets of life. These combined factors have had undeniable impact on Mai Taruvinga's birth registration. In addition, the economic marginality of the father may have influenced his unmarried fatherhood, as shown in Figure 2. [56]

I learned about Musiyiwa—a 15-year-old teen who had lived in alternative care since he was barely a week old—from Mr. Kugotsi, the social worker at the Children's Home. Speaking of Musiyiwa, Mr. Kugotsi related that, not unlike other children under the institution's care, Musiyiwa had no recollection of his mother. Three or so days after his birth, Musiyiwa's mother, who had successfully concealed his birth, clandestinely abandoned him in a cul de sac. He had no knowledge of his relatives either. But that fact of life could not entirely hold him back as far as sport was concerned. Mr. Kugotsi's estimation of his sporting abilities was very positive. He reckoned that Musiyiwa was naturally talented in track and field sports and he invested a lot of effort in practice. The headmaster of a local authority school, located a stone's throw away, shared this opinion. Musiyiwa made the school's athletics team. [57]

The noun "musiyiwa" is vernacular which, when literally translated to English, means "the one who has been left out" or the "one who has been left behind." I use the name in the context of this research to anonymize his identity. I chose this name because it succinctly captures his involvement in sport at school. Despite his enduring passion for sport, Musiyiwa had to contend with huge barriers in order to compete at interschool and higher levels. When he was first selected to represent the school team, his breakthrough was rolled back momentarily: he had no valid birth certificate to prove his age and aspects of identity such as place of origin and details of parents. Strictly speaking, Musiyiwa could not compete without a birth certificate. Yet the social worker at the institution and the school head concurred that competing in interschool competition was good for Musiyiwa's self-efficacy, and it was good for the school too. The headmaster, Mr. Kugotsi, recounted, had reckoned that Musiyiwa's involvement in competitions would help to put the name of the school on the map. [58]

As a remedy, the school authorities agreed to do something rather unconventional. They let Musiyiwa use a fellow pupil's birth certificate in the competitions. And it worked, at least from the school's point of view. Musiyiwa actually competed at sub-national and national levels and collected accolades in recognition of his abilities. But for Musiyiwa, something was not right, the social worker revealed. The schoolmate's name rather than his name was on the accolades. This has remained a sore point for Musiyiwa. [59]

As far as not possessing a birth certificate was concerned, however, Musiyiwa's situation was not that unusual. Many children who end up in the institution were committed there by the Department of Child Welfare and Probation Services due to safety concerns. Mr. Kugotsi detailed that, ideally, a set of official documents is required to sufficiently place a child in alternative care. These include a probation officer's report, police report, medical examinational report, an age estimation report, and a birth certificate. However, in the case of Musiyiwa and his ilk, placement was sort of an emergency. The probation officers placed them without the requisite documentation. Ordinarily, the Children's Home expects that, in such circumstances, the probation officers make the documents available in a matter of weeks. In reality, however, the probation officers tend to take months, even years, before they arrange the requisite documents. Mr. Kugotsi clarified why many children at the institution did not have birth certificates for years. He revealed:

"Normally what happens is that [at] the Child Welfare and Probation Services Department [they are] very concerned [...] when a child is still in their custody. Once the child has been committed to SOS or Chinyaradzo, they seem to take ... yeah, relax. And this [acquiring the birth certificate] becomes our [the Children's Home] responsibility to go and remind them that this child has no birth certificate. ... It becomes a burden on us... You face the child every day. She asks ... I want to participate in sport, I don't have a birth certificate. He says I want to sit for Grade 7 examinations, I don't have a birth certificate." [60]

Mr. Kugotsi further clarified that, "from the viewpoint of the Department of Child Welfare and Probation Services, acquiring a birth certificate is normally a hassle ... Why? Because the probation officer's report [typically] reflects names of [the child's potential] relatives. The Registrar General's Office requires that those relatives be traced before a birth certificate can be issued." Tracing relatives was a huge a setback for Musiyiwa because his probation officer's report indicated that blood relatives exist somewhere in the Gweru countryside. His birth certificate could not be processed until a witness had been located. Mr. Kugotsi revealed that in 2009, 87 out of 150 children at the institution lacked birth certificates. Fifty out of 120 children at the institution had no birth certificates in 2014 compared with 27 out 120 who lacked a birth certificate in 2015. [61]

The second case study is a narrative of how Musiyiwa and other children in alternative care have been excluded from important activities and occupational environments that ordinarily support civic integration. It illustrates how many factors interact over time to create conditions that give rise to negative birth registration outcomes. Ultimately, these dynamics have marginalized Musiyiwa as far as sporting activities at school were concerned. Musiyiwa's disadvantaged situation is, arguably, a consequence of the interaction of personal attributes, relational factors, cultural norms and practices, as well as institutional aspects. Personal factors include Musiyiwa's marginal social interactions emanating from the unknown whereabouts of his parents and relatives (see Table 3). [62]

Additionally, one can speculate that gender stereotypes that ostracize women who have children out of wedlock, while condoning, even accepting unmarried fatherhood, may have contributed to the fateful decision to conceal Musiyiwa's birth. Moreover, the complacency of duty bearers, including social workers in the Department of Child Welfare and Probation Services and police, and institutional cultures of inefficiency work to further marginalize Musiyiwa. Figure 3 illustrates the perceived causal pathways that explain Musiyiwa's marginal participation in sport at school.

Figure 3: Socio-cultural, economic, and institutional factors that have influenced birth registration and social exclusion

outcomes for Musiyiwa [63]

From Figure 3, one can speculate that economic factors equally affect institutional functioning and the ways in which obligations in human relationship are met. Economic factors such as unemployment may explain Musiyiwa's father's unmarried fatherhood and his lack of involvement (see Table 4).

|

Micro-level factors |

Macro-level factors |

|

|

Personal attributes and interpersonal/relational factors |

Informal norms and practices |

Institutional factors |

|

Musiyiwa's lack of information about his parents' whereabouts; Musiyiwa's mother's lack of information about alternative care, e.g. foster care and adoption. |

Society accepts or condones unmarried fatherhood; gender stereotypes. |

Cumbersome procedures for acquiring requisite vital documents; weaknesses of the CRVS systems regarding registering births of children of unknown parents; complacency of social workers. |

Table 4: Barriers to successful registration for Musiyiwa [64]

What follows from the methods and findings examined above for birth registration advocacy? This question is addressed next. [65]

Although advocacy for birth registration and social inclusion of children is emerging in Zimbabwe—as illustrated by the existence of networked non-governmental organizations demanding the expansion of birth registration to all children—a cogent, more appealing motivational frame to enlist the support of various stakeholders and influence tangible policy reforms is missing. According to Barbara KLUGMAN (2011), an empirically driven motivational frame (or a perspective of the problem and policy options) is indispensable if the nascent child advocacy coalescing around birth registration and other children's rights is to score tangible policy gains. Demands for the expansion of birth registration currently draw more on international rights discourses than empirical research. Consequently, as a motivational frame for universal birth registration, the claim that the absence of birth registration complicates social exclusion for the non-registered child is effective as far as it goes. Despite the fact that surveys have been conducted in Zimbabwe, data that demonstrate the dynamic interplay of the multiple dimensions of social exclusion are largely missing. [66]

Thus, although the survey remains the prominent method in birth registration research, it has apparent limits as far as revealing the dynamic interplay of birth registration and dimensions of social exclusion is concerned. The difficulty of capturing social dynamics through quantitative methods was discussed elsewhere (BABAJANIAN & HAGEN-ZANKER, 2012). In light of these limits, I have argued for increased adoption of qualitative methods in advocacy-oriented research on birth registration and social exclusion. To illustrate the efficacy of qualitative research in revealing the interplay of various dimensions of exclusion and birth registration outcomes, the article first considered survey results of barriers to birth registration. Existing surveys typically illuminate correlation of a given perceived barrier and birth registration. The ways in which multiple factors give rise to marginalization and affect birth registration and social inclusion outcomes remain concealed in such descriptive quantitative research. [67]

It is not untrue that other sophisticated quantitative approaches such as experimental designs and modeling can generate measures of causality between selected variables and birth registration. Still, as Lawrence PALINKAS (2014) argued, these sophisticated approaches do not overcome the challenge of measuring and attributing causality where multiple factors have influenced a given outcome. Social exclusion is a multidimensional phenomenon (BABAJANIAN & HAGEN-ZANKER, 2012) which denotes multiple dimensions, including structures and processes that sustain disadvantage. Subsequently, the analyses of social exclusion are almost always multifactorial (TANTON, HARDING, DALY, McNAMARA & YAP, 2010). [68]

In this article, I used narratives of two participants to demonstrate the utility of biographical methods for advocacy-oriented research in birth registration. The cases presented demonstrated that biographical methods can potentially reveal the dynamic interaction of multiple factors that give rise to social exclusion outcomes over time. Personal narratives can generate relevant data to demonstrate the interplay of factors that give rise to circumstances of disadvantage and non-birth registration. The case studies provided in the foregoing sections suggest that personal and relational factors; cultural norms, beliefs, and values; as well as institutional factors are, at once, implicated in social exclusion outcomes. The story of Mai Taruvinga demonstrates that personal traits and relational factors interact with social facts emanating from shared societal beliefs and informal norms and practices, as well as institutional arrangements—albeit in complex causal ways. For example, the fact that the relatives of the deceased grandmother never attempted to apply for her death certificate prior to or just after the burial ceremony has more to do with shared beliefs about death and dying than the economic status of the significant others. Unlike the administration of the deceased's estate, which requires the involvement of bureaucrats, the customary practice of sharing personal belongings of the deceased among deserving relatives does not provide an incentive for the acquisition of a death certificate. Similarly, customary marital arrangements do not provide an incentive for the acquisition of a birth certificate at the time of marriage. In a story, the manner in which social facts originating from cultural formations and institutional arrangements affect birth registration is distinctly represented. [69]

In analyzing the second case study, I speculated that gender stereotypes which ostracize unmarried motherhood while condoning unmarried fatherhood may have influenced Musiyiwa's isolation from his parents and relatives, in the first place. Subsequently, the requirements of the CRVS system—for example, the requirement that the confirmed relatives of children in alternative care be present —the lack of information about the whereabouts of Musiyiwa's parents or relatives derailed birth registration. Through the use of perceived causal pathways, I have demonstrated that interviews are especially suitable for establishing causal connections among multiple constituents of the lived life. [70]

Biographical methods can easily be adapted to projects that seek to generate advocacy-oriented research in a time-effective manner. To illustrate this attribute of biographical methods, I borrowed some of the principles that made PRA popular—for example, optimal ignorance, appropriate imprecision, and maximizing diversity. When combined with relevant conceptual frameworks and in-depth and systematic content analysis of data, biographical methods can generate insights for succinctly framing the research problem and policy options for advocacy. Importantly, when research is needed to generate data for motivational frames, stories may be more readily usable than research built on number crunching. As Kip JONES (2003) contended, what interviewees share about their lived experiences and self-concepts builds something much more than any hypothesis or research question can generate. The case studies demonstrated that a story can make visible the multitudes of relationships, beliefs, and institutional arrangements which give rise to the situation that is the subject of the encounter between the interviewee and the researcher. Such connections are possibly revealed through in-depth text analyses and reconstruction of perceived causal pathways that represent causality in a visual manner. [71]

Even when insights from the story are visually presented, they still communicate the aspirations and frustrations of social life; they make visible the agency of those people who care for children. Personal narratives can easily be transformed into personal testimonies which help the "support base and allies to pin down the problem definition, to shape and test potential policy options, and to analyze a changing policy environment" (KLUGMAN, 2011, p.153). Arguably, then, interviews and the narratives they generate are fodder for those engaged in birth registration activism. The results generated by the mixed-methods study, particularly the insights from the interviews, suggest that demands for universal birth registration have to be subsumed in perspectives that cast the problem of birth registration as a bigger challenge of the CRVS system. The analysis of the narratives demonstrated that birth registration is intertwined with the registration of marriages and deaths. What interviewee accounts can show is that motivational frames that focus exclusively on birth registration may not send the right messages about the problem of birth registration in Zimbabwe. [72]

Insights considered in the article were generated in the context of a study funded by UNICEF Zimbabwe through a small research grant that was administered by the Women's University in Africa. My sincere thanks go to Tawanda MASUKA, Jekoniya CHITEREKA and Eve MUSVOSVI, who were part of the research team.

1) Ward and district are units of political administration in Zimbabwe. The district of Bindura is located in the Mashonaland Central province and has 33 wards. <back>

2) Enumeration areas are the smallest geographical units drawn in every census to collect census data. <back>

3) The custom is known as kubata nhumbi. The ceremony reflects what legal officials do when executing the deceased’s estate. <back>

Adamas, Peter J. & Beutow, Stephen (2014). The place of theory in assembling the central argument for a thesis or dissertation. Theory & Psychology, 24(1), 93-110.

Babajanian, Babken (2013). Social protection and its contribution to social inclusion. London: ODI.

Babajanian, Babken & Hagen-Zanker, Jessica (2012). Social protection and social exclusion: An analytical framework to assess the links. London: ODI.

Berenzon Gorn, Shoshana & Sugiyama Ito, Emily (2004). Between traditional and scientific medicine: A research strategy for the study of the pathways to treatment followed by a group of Mexican patients with emotional disorders. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung / Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 5(2), Art. 2, http://nbn-resolving.de/urn:nbn:de:0114-fqs040229 [Date of Access: December 17, 2016].

Bourdillon, Michael (2011). A challenge for globalized thinking: How does children's work relate to their development? South African Review of Sociology, 42(1), 97-115.

Cascardi, Michele; Brown, Cathy; Shpiegel, Svetlana & Alvarez, Ariel (2015). Where have we been and where are we going? A conceptual framework for child advocacy. Sage Open, 5(1), 1-10, http://journals.sagepub.com/doi/full/10.1177/2158244015576763 [Date of Access: December 17, 2016].

Chambers, Robert (1994). Participatory rural appraisal (PRA): Analysis of experience. World Development, 2(9), 1253-1268.

Chereni, Admire (2015). Advocacy in the South African social welfare sector: Current social work research and possible future directions. International Social Work, Online First, http://journals.sagepub.com/doi/full/10.1177/0020872815580042 [Date of Access: December 18, 2016].

Crouch, Mira & McKenzie, Heather (2006). The logic of small samples in interview-based qualitative research. Social Science Information, 45(4), 483-499.

De Tona, Carla (2006). "But what is interesting is the story of why and how migration happened". Ronit Lentin and Hassan Bousetta in conversation with Carla De Tona. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung / Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 7(3), Art. 13, http://nbn-resolving.de/urn:nbn:de:0114-fqs0603139 [Date of Access: March 14, 2016].

Freeman, Michael (1998). The sociology of childhood and children's rights. The International Journal of Children's Rights, 6, 433-444.

Guetterman, Timothy C. (2015). Descriptions of sampling practices within five approaches to qualitative research in education and the health sciences. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung / Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 16(2), Art. 25, http://nbn-resolving.de/urn:nbn:de:0114-fqs1502256 [Date of Access: December 17, 2016].

Hobcraft, John & Kiernan, Kathleen (2001). Childhood poverty, early motherhood and adult social exclusion. British Journal of Sociology, 52(3), 495-517.

Hsieh, Hsiu-Fang & Shannon, Sarah E. (2005). Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qualitative Health Research, 15(9), 1277-1288.

James, Allison (2007). Giving voice to children's voices: Practices and problems, pitfalls and potentials. American Anthropologist, 109(2), 261-272.

Jones, Kip (2003). The turn to a narrative knowing of persons. One method explored. NT Research, 8(1), 60-71.

Klugman, Barbara (2011). Effective social justice advocacy: A theory-of-change framework for assessing progress. Reproductive Health Matters, 19(38), 146-162.

Kvale, Steinar (2007). Doing interviews. London: Sage.

Leshem, Shosh & Trafford, Vernon (2007). Overlooking the conceptual framework. Innovations in Education and Teaching International, 4(1), 93-105.

Maxwell, Joseph A. (1996). Qualitative research design: An interactive approach. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Mayall, Berry (2000). The sociology of childhood in relation to children's rights. The International Journal of Children's Rights, 8, 243-259.

Nelson, Paul & Dorsey, Ellen (2007). New rights advocacy in a global public domain. European Journal of International Relations, 13(2), 187-216.

Palinkas, Lawrence A. (2014). Causality and causal inference in social work: Quantitative and qualitative perspectives. Research on Social Work Practice, 24(5), 540-547.

Pelowski, Mathew; Wamai, Richard G.; Wangombe, Joseph; Nyakundi, Hellen; Oduwo, Geofrey O.; Ngugi, Benjamin K. & Ogembo, Javier G. (2015). Why don't you register your child? A study of attitudes and factors affecting birth registration in Kenya, and policy suggestions. The Journal of Development Studies, 51(7), 881-904.

Quennerstedt, Ann (2013). Children's rights research: Moving into the future—Challenges on the way forward. International Journal of Children's Rights, 21, 233-247.

Roberts, Rosemary (2010). Wellbeing from birth. London: Sage.

Roelen, Keetie & Sabates-Wheeler, Rachel (2012). A child-sensitive approach to social protection: Serving practical and strategic needs. Journal of Poverty and Social Justice, 20(3), 291-306.

Tanton, Robert; Harding, Ann; Daly, Anne; McNamara, Justine & Yap, Mandy (2010). Australian children at risk of social exclusion: A spatial index for gauging relative disadvantage. Population, Space and Place, 16, 135-150.

United Nations International Children's Emergency Fund (UNICEF) (2002). Birth registration: Right from the start. Florence: Innocenti Research Centre, https://www.unicef-irc.org/publications/330/ [Date of Access: November 27, 2016].

United Nations International Children's Emergency Fund (UNICEF) (2013). A passport to protection: A guide to birth registration programming. New York: UNICEF, https://www.unicef.org/protection/files/UNICEF_Birth_Registration_Handbook.pdf [Date of Access: March 10, 2016].

United Nations International Children's Emergency Fund (UNICEF) & Ministry of Labour and Social Services (2011). Lessons learned from ongoing social cash transfer programmes in Zimbabwe. Harare: UNICEF & Ministry of Labour and Social Services, https://www.unicef.org/zimbabwe/ZIM_resources_lessonscashtransfer.pdf [Date of Access: January 10, 2016].

Wabwile, Michael (2010). Implementing the social and economic rights of children in developing countries: The place of international assistance and cooperation. International Journal of Children's Rights, 18, 355-385.

ZIMSTAT (2015). Zimbabwe multiple indicator cluster survey 2014. Final report. Harare: ZIMSTAT, http://www.zimstat.co.zw/sites/default/files/img/publications/Health/MICS2014/MICS2014_Key_Findings_Report.pdf [Date of Access: March10, 2016].

Admire CHERENI is a post-doctoral research fellow at the Centre for Anthropological Research, University of Johannesburg, South Africa.

Contact:

Dr. Admire Chereni

Centre for Anthropological Research

House 10, Research Village Bunting Road Campus

University of Johannesburg

Box 524, Auckland Park, 2006 Johannesburg, South Africa

Tel.: +27 (0) 76 1993 954

E-mail: admirechereni@gmail.com