Volume 18, No. 2, Art. 9 – May 2017

She Said, She Said: Interruptive Narratives of Pregnancy and Childbirth

Alison Happel-Parkins & Katharina A. Azim

Abstract: In this article, we explore narrative inquiry data we collected with women who attempted to have a natural, drug-free childbirth for the birth of their first child. The data presented come from semi-structured life story interviews with six women who live in a metropolitan city in the mid-southern United States. Using creative analytic practice (CAP), the women's experiences are presented as a composite poem. The (re)presentation of the women's narratives in the poem emphasizes the tensions between what women desired and planned for in contrast to what they actually experienced during pregnancy and birth. The poem illustrates the politics of agency, the ways in which consent is bypassed or assumed in some medical institutions in the United States, and the resilience of the women.

Key words: natural childbirth; medicalization; narrative inquiry; creative analytic practice; composite poem; informed consent; agency

Table of Contents

1. Introduction

2. Childbirth in Context: Institutional Medicalization and Local Alternatives

3. Methodology and Method

4. Analysis and Representation

5. Discussion

6. (Re)Presenting Birth Differently

Frame #1

"I'm sitting across from my OBGYN [Obstetrics and Gynecology doctor] and finally tell him I decided to have a homebirth. He looks shocked, and finally sputters, 'Well, if you want to put your own wants ahead of your baby's, then go do whatever you want!' Stunned and feeling attacked, I momentarily question my decision, despite all the research I had done on different birthing options. He continues, 'That's selfish and unsafe, and I recommend you reconsider. I think all babies should be born in the hospital.' Hearing these snide remarks, I remind myself of the many people in my life who support my decision, because otherwise I might lose confidence in my choice."

Frame #2

"I'm not from here, and when I got pregnant I couldn't believe that this city doesn't have any birthing centers. I always assumed I would have the ability to labor in a birthing tub. So I started calling around to the hospitals in my insurance network to see what birth options they provide. The first one I called marketed themselves as a state-of-the-art Women's Center, and the woman I talked to laughed at me when I asked if they provided women with birthing tubs. It's an understatement to say that I was extremely discouraged. I don't see how you can give birth in this town without drugs unless you're having a baby in your living room."

Frame #3

"I was very confident in my ability to have an unmedicated childbirth. Women in my family birth fast, and I have a pretty high pain tolerance. In hindsight, though, it seems I was over-confident. I was young, I was liberated, I had done my research. Once I was admitted to the hospital after I had labored at home for hours, they immediately put me on a Pitocin1) drip without my knowledge or consent. When I found out and confronted them, the nurses just laughed in my face and said, 'Honey, you're in the hospital. That's how we do things here!' "

The above frames were based on data collected from women in the mid-southern United States who wanted to have a drug-free childbirth for the birth of their first baby. The aim of the broader study, from which these frames derive, was to examine the experiences of women who attempted an unmedicated, "natural" childbirth through individual life story interviews. In what follows, we will first describe the specific, national and local, contexts within which our participants made decisions about their pregnancies and births (Section 2). Next, we discuss the chosen methodology and methods of data collection (Section 3), followed by an in-depth discussion of how and why we (re)presented the data through a composite poem (Section 4). We end with an analysis of both the rich content of the women's narratives, as highlighted through the poem (Section 5), and a discussion of how Creative Analytic Practice can be used to open up productive and provocative spaces by the inclusion of transgressive data (Section 6). [1]

2. Childbirth in Context: Institutional Medicalization and Local Alternatives

Participants in this study sought to have a drug-free childbirth for the birth of their first baby. Although the individual experiences of the women differed, the women's pregnancies and childbirth experiences were shaped by their geographical and social contexts, and by the national and local practices and policies of the medical institutions in which they gave birth. While the United States spends more than any other country on health care, $111 billion exclusively for maternal care facility charges (CHILDBIRTH CONNECT, 2012), these monetary investments are not reflected in maternal and infant health indicators. For example, the U.S. ranks 51st in infant mortality rates (CHEN, OSTER & WILLIAMS, 2015). Similarly, while maternal mortality rates have decreased internationally by 34%, maternal mortality rates for women in the U.S. have nearly doubled since 1990 (ALLEN, 1998; BINGHAM, STRAUSS & COEYTAUX, 2011; GASKIN, 2011; HODGES, 2009). Since these deaths are preventable, some researchers and women's health advocates assert that the alarmingly high infant and maternal mortality rates are not simply a national concern but a human rights failure (BINGHAM et al., 2011). [2]

The increased medicalization of pregnancy and childbirth is one reason that healthcare costs in the U.S. are so high for pregnant and birthing women (GOODMAN, 2007; OECD, 2013). Routinized medical procedures often lead to what researchers have termed the cascade of intervention (INCH, 1981; TRACY & TRACY, 2003), often resulting in unnecessary medical interventions that lead to even further increasingly invasive procedures. In fact, Cesarean sections have become the most common surgical procedure in the U.S. (HAMILTON, MARTIN & VENTURA, 2014). Unsurprisingly then, Cesarean rates in the U.S. are 3-4 times higher than the numbers recommended by the World Health Organization (WHO). The WHO recommends that Cesarean rates stay between 5-15%, yet in the U.S. 32% of women give birth by Cesarean section (HAMILTON et al., 2014; WHO, 2009). This increased rate may be partly due to the fact that most women in the United States have limited access to midwives or doulas (GOODMAN, 2007; MILLER & SHRIVER, 2012) or birthing options (BOUCHER, BENNETT, McFARLIN & FREEZE, 2009; MacDORMAN, DECLERCQ & MATHEWS, 2013; MADI & CROW, 2004). [3]

While the above statistics for the U.S. are informative, they do not adequately represent the internal disparities that are present within the country. For example, the city in which this study took place has one of the highest infant and maternal mortality rates in the country (FINERMAN, WILLIAMS & BENNETT, 2010). These rates are, in part, due to the prevalence of concentrated poverty and structural racism plaguing the city. Many women struggle for access to basic health care, and all women, regardless of socioeconomic status, lack birthing options. There are no free-standing or in-hospital birthing centers in the city, and the nearest one is located 200 miles away.2) One benefit of birthing centers is their lower rates of medically unnecessary interventions (MANSFIELD, 2008; RAISLER, 2000). Due to the above-mentioned factors, women in this city who prefer a drug-free birth for their child do not have many options and thereby often have limited control over their childbirth experiences. [4]

Despite the structural barriers to access health care and birthing options, there are a number of grassroots groups and organizations working toward creating services available to pregnant women. For example, there are two midwifery groups that provide alternative and homebirthing options. Additionally, a local doula collective trains and places volunteers in reproductive health clinics and hospitals throughout the city. This collective is currently in the process of raising money for the construction of the first free-standing birth center in the larger metropolitan region. The birth center will be connected to, and overseen by, a local reproductive health clinic. Meanwhile, these advocacy groups have been helping connect pregnant women with doulas-in-training that provide their services free of charge or for a reduced price. These grassroots initiatives are an indication of women's unmet needs and preferences for alternative, non-invasive birthing options. [5]

Given this unique social context, we sought to better understand the experiences of women in this mid-southern metropolitan city who attempted to mitigate the medicalization of childbirth by planning to have a drug-free labor and birth. Our guiding research question was: How do first-time mothers who decided to attempt labor and birth without medical intervention conceptualize and experience childbirth? [6]

Narrative inquiry was our chosen methodology which guided our data collection. According to CHASE (2005), narrative inquiry focuses on the uniqueness of a person's experiences, in specific events and in interaction with others. The stories told by participants are understood as flexible, situated, dynamic, and context-dependent (ibid.; see also CLANDININ & CONNELLY, 2004; RIESSMAN, 2008). Through narrative inquiry, researchers use storytelling as a method of inquiry, allowing for the individual's experiences, thoughts, and beliefs, their emotions and interpretations to surface in interviews, but more importantly in the analysis and (re)presentation. These aspects of their stories are then simultaneously understood as being linked to the larger contextual discourses. [7]

We conducted semi-structured life story interviews with six women who had attempted to have a natural, drug-free labor for the birth of their first child. Our research criterion for this study was that potential participants had intended to have a natural, drug-free childbirth for the birth of their first child. Six women were ultimately recruited via snowball sampling (PATTON, 1990). The six women were between 30 and 45 years old, five were White and one was Black. All research participants were middle class and living in or around this mid-southern city. The research question guiding our study was: How do first-time mothers who decided to attempt labor and birth without medical intervention conceptualize and experience childbirth? [8]

Approval from the Institutional Review Board (IRB) at our university, which evaluates fulfillment of ethical and institutional guidelines on research with human subjects, was sought and obtained. During the meetings with the research participants, the women gave their verbal and written consent, and the interviews lasted from 45-90 minutes. In this study, HAPPEL-PARKINS conducted the interviews, AZIM transcribed them verbatim, and both analyzed the data. HAPPEL-PARKINS is a White woman from the mid-western United States, who works as an assistant professor at a local university. She first became interested in natural childbirth when she attended a doula training while in graduate school. At the time the interviews were conducted, she had no children; however, during data analysis, she was pregnant and gave birth to her first child in a home birth. AZIM is a White woman from a metropolitan city in Germany, who has completed her doctoral studies in the mid-southern U.S. She is active in a local doula collective and has no children of her own. She regularly volunteers at two local women's clinics. [9]

4. Analysis and Representation

We undertook this analysis after publishing a traditional thematic analysis of the data (HAPPEL-PARKINS & AZIM, 2016). As we were coding and reducing the data, we both felt uneasy about how much of the women's voices and lives we were excluding from our representation. This analysis uses creative analytic practice (CAP), and it is a way for us to centralize the women's voices while also presenting their stories in an artistic and engaging format. Following many proponents of CAP, we believe it is important for academics to (re)present their data in accessible and provocative ways (BERBARY, 2011, 2012; RICHARDSON & ST. PIERRE, 2005). According to LINCOLN and GUBA (2005), the goal of CAP is to

"break the binary between science and literature, to portray the contradiction and truth of human experience, to break the rules in the service of showing, even partially, how real human beings cope with both the eternal verities of human existence and the daily irritations and tragedies of living that existence" (p.211). [10]

CAP allows us to contextualize the women's experiences, as opposed to reducing and/or generalizing them, and facilitates a rich exploration of the various discourses at work in the women's lives. As PARRY and JOHNSON (2007) explained, the purpose of CAP is "to reflect experiences in ways that represent their personal and social meanings rather than simplifying and reducing to generalize" (p.120). [11]

We chose to represent our data through the creative analytic practice of research poetry. Because the interviews with our participants were so emotionally charged—in some instances women were explicitly describing life and death situations—we wanted to honor the emotionality of the data. As POINDEXTER (2002) stated, "[t]he advantage of research poetry may be that core narratives and strong emotions can be communicated with an economy of words" (p.713). Similarly, as FURMAN (2006) asserted, we believe "poetry often has the capacity to penetrate experience more deeply than prose" (p.561), or, in our case, traditional data (re)presentation and analysis. In addition to validating the emotions and seriousness of our participants' stories, research poetry, or as some call it poetic inquiry (BUTLER-KISBER, 2010), also enables us to highlight the nuances and complexities inherent in the data. As SZTO, FURMAN and LANGER (2005) explained, "poetry allows for reduction of data ... yet allows for the subtleties that we value in qualitative research" (p.145). Ultimately, our aims are congruent with POINDEXTER's (2002), who suggested that "[t]he resulting poem may bring points to the fore, clarify and make the account more compelling, create a different effect, engage the reader and listener, and tell us something about lived experience that we did not previously understand" (p.713). Finally, this form of representation is especially appropriate for feminist researchers who wish to keep women's in vivo descriptions, phrasing, meaning, etc. intact. As CHADWICK (2009) stated, there is still a paucity of research about pregnancy and childbirth that is "articulated from the embodied perspective of the birthing woman" (p.110). The research poem is a space where the women's own renderings of their experiences are (re)presented. Perhaps relatedly, the research poem may also be more accessible than other forms of data representation (JANESICK, 2016), which is an attribute some feminist researchers strive for (LAHMAN et al., 2011). [12]

While we kept the women's words, phrases, and voices intact and central, as GLESNE (1997) outlined, we simultaneously illuminated the fictional/contrived/constructed nature of all data (re)presentations by depicting their stories through one larger composite research poem. The poem we subsequently created from our data allowed for a holistic, evocative representation of participants' experiences and stories (BUTLER-KISBER, 2002; FURMAN, 2006; LAHMAN et al., 2011; RICHARDSON, 2000; SPARKES, 2008). All the women's narratives were used in the poem, although we did not do any auditing to ensure they were equally represented, as we do not subscribe to post-positivistic practices such as data saturation. Instead we worked to create a composite research poem that represented the combined experiences of the women. An advantage to using a composite poem is that it underscores the impossibility of (re)presenting a/the Truth of a narrative(s) (ELLIS, 2004; PARRY & GLOVER, 2011), allowing researchers to work with transgressive data that is often ignored in more traditional analyses. Following GLESNE's description of creating what she calls poetic transcriptions, we 1. only used words and phrases said by the participants; 2. we "could pull ... phrases from anywhere in the transcript and juxtapose them" (1997, p.205); and 3. had to honor the context in which the words and phrases were said, and also honor our participants' "way of saying things" (ibid.). Throughout the process, we attempted to create what CHARMAZ calls an "artful weaving of participants' words," which "shows the rhythm, grace, and expressiveness of their voices and the passion in their words" (2012, p.490). [13]

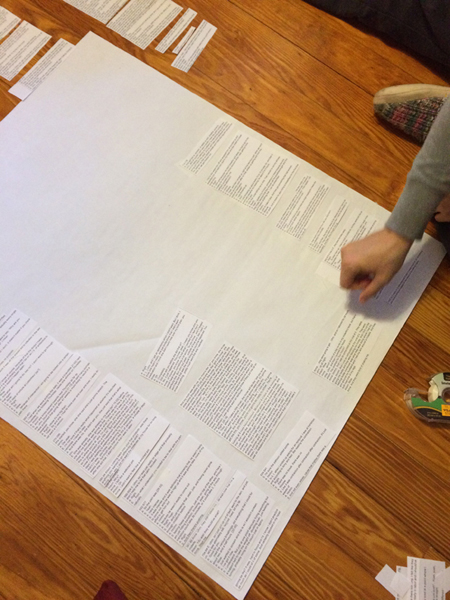

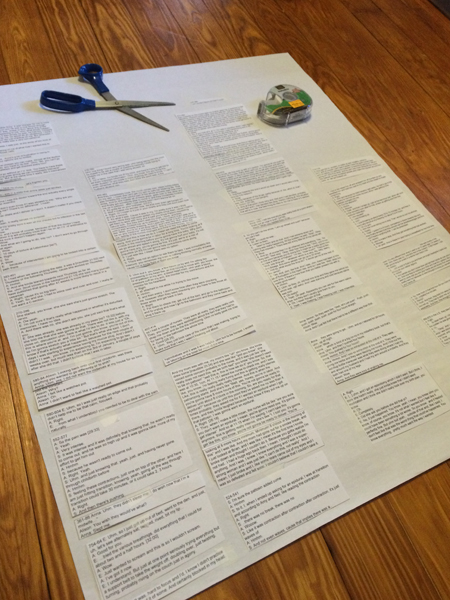

Initially, while immersing ourselves in the data by reading and rereading the interview transcripts, we both independently noticed two parallel storylines in the narratives of the women: one on their actual childbirth experiences and the other of how they wished or had envisioned their birth to take place. This second storyline was often accompanied by self-reflexive thoughts that relied on their current time and distance from their first childbirth. Often, the contrast between the two storylines was striking. Using structured coding (SALDAÑA, 2009), we printed off two sets of interview transcripts, then independently went through the transcripts and physically cut out the data that fell under either category. Afterwards, we compared and discussed our selected data, and placed them into chronological order on an oversized poster in order to see the progressing storylines in their entirety. Here, we selected subtitles that represented the different pre-, peri-, and postnatal stages of the composite narrative (see Figures 1 and 2).

Figure 1: Initial attempt at arranging transcript excerpts

Figure 2: Chronological arrangement of transcript excerpts [14]

The process of arranging transcript excerpts was inherently messy, and looking at the interview fragments chronologically was productive as we thought through our data; this way of arranging the fragments also reflected how the women narrated their experiences. Visually seeing the data in a loose chronology helped us work toward our ultimate research poem. After physically (re)arranging the fragments and discarding the many duplicate chunks of data, we then transferred the texts to a digital word document and worked independently at what POINDEXTER described as diamond cutting. This process consists of "carving and chipping away in the transcript of material other than that which contains the kernel of the phenomenon" (2002, p.709). The results were poem-like data slices, which we then compared, discussed, and read out loud repeatedly, experimenting with placement and rhythm until we came to consensus as to how we wanted to present the data. As we negotiated this process, we continuously and critically interrogated if we were staying true to the meaning of what was being said and the context in which it was said. Through extensive conversations, we combined and further condensed the selected data in order to create the final poetic (re)presentation, or, what LANGER and FURMAN (2004) refer to as, narrative data "in compressed form" (§3). The poem is constructed to encourage a juxtaposed reading: the left side delineates the women's factual and oftentimes linear descriptions of their labors and births, while the right side depicts their wishes, desires, and/or retrospective self-reflections. The four parts of the poem are reflective of the linearity of the women's narratives, starting at the end of their pregnancies and preparations for the upcoming births, at the onset of their labor, during the intensification of their labor and subsequent birth, and the poem ends with the women's post-partum experiences and reflections.

|

1 |

4.1 The OB was a nice enough doctor |

|

|

2 |

but did not educate me in ANY way. |

|

|

3 |

S/he would |

|

|

4 |

get my numbers, |

|

|

5 |

do an ultrasound. |

|

|

6 |

I was in and out. |

|

|

7 |

It was a very non-personal relationship. |

|

|

8 |

There was no empowering of me about |

|

|

9 |

how I wanted this to happen. |

|

|

10 |

S/he called the shots. |

|

|

11 |

I had to pick an induction date. |

|

|

12 |

It was either |

|

|

13 |

next Thursday |

|

|

14 |

or the following Thursday |

|

|

15 |

because s/he worked on Thursdays. |

|

|

16 |

|

I wanted a home birth, |

|

17 |

|

but it wasn't an option. |

|

18 |

|

I would have had to pay out of pocket. |

|

20 |

My insurance told me which hospitals |

|

|

21 |

I could choose from. |

|

|

22 |

I called the hospitals to ask about a birthing tub. |

|

|

23 |

They laughed at me. |

|

|

24 |

They were like, "What?!?!" |

|

|

25 |

There's a lot of frustration in being here, |

|

|

26 |

in this city, |

|

|

27 |

because your options are so limited. |

|

|

28 |

I had no choices. |

|

|

29 |

The doctors tell you what you |

|

|

30 |

can |

|

|

31 |

and can't |

|

|

32 |

do. |

|

|

33 |

|

… And I get it. I do. |

|

34 |

But, they have |

|

|

35 |

mechanized |

|

|

36 |

everything for their convenience. |

|

|

37 |

In the final weeks, |

|

|

38 |

every time I saw the doctor |

|

|

39 |

I was resentful. |

|

|

40 |

And I didn't even know if I was allowed to say, |

|

|

41 |

"Why are you checking me? |

|

|

42 |

I either dilate and I deliver or I don't. |

|

|

43 |

It doesn't matter if you check me." |

|

|

44 |

|

They're trained as surgeons. |

|

45 |

|

They're very comfortable with that role. |

|

46 |

|

And I'm glad they are. |

|

47 |

Primrose Oil? |

|

|

48 |

Red Raspberry Leaf Tea? |

|

|

49 |

Anything I brought up |

|

|

50 |

outside of the typical |

|

|

51 |

medical field or OB-establishment, |

|

|

52 |

"Sorry, that's outside my training." |

|

|

53 |

|

I appreciated her honesty, |

|

54 |

|

but a midwife could have |

|

55 |

|

guided me |

|

56 |

|

in those things |

|

57 |

|

so that I could have had the |

|

58 |

|

birth I wanted. |

|

59 |

She said she's just gonna stretch |

|

|

60 |

the cervix. |

|

|

61 |

She was already, |

|

|

62 |

she was already |

|

|

63 |

down there |

|

|

64 |

before she told me that she was gonna do |

|

|

65 |

that. |

|

|

66 |

There was no discussion. |

|

|

67 |

… Then I lost my mucus plug. |

|

|

68 |

4.2 I didn't believe I was in labor |

|

|

69 |

When my contractions started, |

|

|

70 |

I just got up out of bed, went to the den, and just alternately |

|

|

71 |

sat |

|

|

72 |

…twisted |

|

|

73 |

……writhed |

|

|

74 |

………bit my lip … tried the various breathings, |

|

|

75 |

did everything that I could |

|

|

76 |

for two and a half hours. |

|

|

77 |

Just wanted to scream, but |

|

|

78 |

|

I didn't want to wake my husband. |

|

79 |

|

I wish I hadn't been so on edge |

|

80 |

|

so that I could have dealt |

|

81 |

|

with the pain better |

|

82 |

|

on my own. |

|

83 |

|

I needed to be calm, |

|

84 |

|

focused, |

|

85 |

|

in order to deal with the pain |

|

86 |

|

naturally. |

|

87 |

I was in agony. |

|

|

88 |

It was hard to focus, |

|

|

89 |

|

and I know I didn't practice enough. |

|

90 |

|

The entire time I'm thinking, |

|

91 |

|

I wish I knew what I was doing. |

|

92 |

|

I wish I knew a better way. |

|

93 |

|

I wish I could figure it out. |

|

94 |

|

I wish I had a |

|

95 |

|

damn midwife or doula. |

|

96 |

When I arrived, laboring, at the hospital, |

|

|

97 |

they took me to a room by myself. |

|

|

98 |

They asked me questions, |

|

|

99 |

which I found jarring. |

|

|

100 |

They asked me if I was abused. |

|

|

101 |

I can't remember what they said |

|

|

102 |

because I was |

|

|

103 |

out of my mind. |

|

|

104 |

|

I wanted … ambiance. |

|

105 |

They played hokey pokey with my vein. |

|

|

106 |

That was the most painful part of my whole labor. |

|

|

107 |

The nurse immediately hooked me up to Pitocin. |

|

|

108 |

They didn't read my chart. |

|

|

109 |

I asked, |

|

|

110 |

"What is that? |

|

|

111 |

I don't wanna be on any medicine." |

|

|

112 |

And the nurse's demeanor changed, |

|

|

113 |

"Honey, you're in a hospital and |

|

|

114 |

this is how we do things here." |

|

|

115 |

There was no option. |

|

|

116 |

I was immediately insecure. |

|

|

117 |

She assured me, |

|

|

118 |

"It's not gonna hurt your baby, you're gonna be fine |

|

|

119 |

It's just gonna help contractions come along." |

|

|

120 |

I'm in fight or flight and |

|

|

121 |

not thinking normally. |

|

|

122 |

There was nothing I could do. |

|

|

123 |

4.3 A few hours go by |

|

|

124 |

I'm sitting there trying to process everything |

|

|

125 |

with the IV of Pitocin in my arm, |

|

|

126 |

a blood pressure cuff on, |

|

|

127 |

a fetal monitor hooked up, |

|

|

128 |

all attached to me while I'm trying to move. |

|

|

129 |

I have to get back in bed |

|

|

130 |

whenever they check me. |

|

|

131 |

And I have to unplug to get up. |

|

|

132 |

|

I always assumed that I would have the option |

|

133 |

|

to labor in a birthing tub. |

|

134 |

|

That's how I managed pain for menstrual cramps. |

|

135 |

|

So I just |

|

136 |

|

I just |

|

137 |

|

assumed |

|

138 |

|

that's how I would |

|

139 |

|

I would |

|

140 |

|

handle labor. |

|

141 |

My mom voiced her concern to the nurses. |

|

|

142 |

She told them: |

|

|

143 |

We, |

|

|

144 |

the women in our family, |

|

|

145 |

birth fast. |

|

|

146 |

The nurse, again, |

|

|

147 |

"This is how we do it here." |

|

|

148 |

Once it started to get really |

|

|

149 |

Pitocin-intense |

|

|

150 |

that's when the patronizing started. |

|

|

151 |

Laughing, she said: |

|

|

152 |

"Well, yes, honey, you're in labor. |

|

|

153 |

You're gonna have 8 more hours of this!" |

|

|

154 |

|

Looking back, |

|

155 |

|

my body was progressing. |

|

156 |

|

It was doing what it was supposed to |

|

157 |

|

before the Pitocin. |

|

158 |

"So, are you ready for the epidural yet?" |

|

|

159 |

|

I wish everyone hadn't been |

|

160 |

|

tired and exhausted |

|

161 |

|

by the time I was ready to |

|

162 |

|

push. |

|

163 |

My birth music changed. |

|

|

164 |

Metallica. |

|

|

165 |

The nurse yells, |

|

|

166 |

"Call the doctor!" |

|

|

167 |

And instantly it was a flood of panic. |

|

|

168 |

"The baby's here, the baby's crowned." |

|

|

169 |

|

I felt excited because |

|

170 |

|

it was about over |

|

171 |

|

and |

|

172 |

|

I knew I was right. |

|

173 |

She gloves her hand, |

|

|

174 |

puts her forearm in me, |

|

|

175 |

and pushes the baby back. |

|

|

176 |

Holds her inside of me. |

|

|

177 |

18 minutes. |

|

|

178 |

She waits until the doctor can arrive |

|

|

179 |

to be the one to "deliver" the baby. |

|

|

180 |

|

… there had to be another way … |

|

181 |

|

I wanted to be free to follow my instincts |

|

182 |

|

rather than being told when it was time |

|

183 |

|

to do something with my own body. |

|

184 |

I had an episiotomy, |

|

|

185 |

|

which I didn't want. |

|

186 |

She didn't look at my birth plan. |

|

|

187 |

It just happened. |

|

|

188 |

|

It's not what I wanted, |

|

189 |

but it could've been |

|

|

190 |

something a lot worse. |

|

|

191 |

4.4 Lying on a bed in a sterile room that's cold |

|

|

192 |

with cold IV fluid in you |

|

|

193 |

there are bright headlights shining on your nether regions. |

|

|

194 |

And people you don't know have just had |

|

|

195 |

their hands all over and in you. |

|

|

196 |

And now they're holding your child |

|

|

197 |

and now he's upstairs. |

|

|

198 |

|

But people want to come visit you, |

|

199 |

and your hands are still bloody |

|

|

200 |

from where you briefly held him |

|

|

201 |

because no one's thought to bring you |

|

|

202 |

something to wash your hands off … |

|

|

203 |

|

I wanted him to stay in the room. |

|

204 |

In the U.S., they take the baby away |

|

|

205 |

… to clean them up. |

|

|

206 |

|

I tried to hold on a little bit, |

|

207 |

but all of a sudden he was gone. |

|

|

208 |

I felt bloody, |

|

|

209 |

and vulnerable, |

|

|

210 |

and open, |

|

|

211 |

and exposed, |

|

|

212 |

and not in a position to |

|

|

213 |

|

say something assertively. |

|

214 |

Everything medical felt like it got in the way. |

|

|

215 |

|

And I just, I, I wished |

|

216 |

|

that there had been more |

|

217 |

|

flexibility. |

|

218 |

I didn't realize that in a………….hospital |

|

|

219 |

you do not have………………….rights |

|

|

220 |

You do not call any……………...shots |

|

|

221 |

They're completely in…………...control |

|

|

222 |

and they manage………………..everything |

|

|

223 |

they make sure to assert their…authority |

|

|

224 |

and their position of……………..power |

|

|

225 |

I mean, it, it dehumanized it. |

|

|

226 |

It made it something you have to endure |

|

|

227 |

instead of the result of something happy. |

|

|

228 |

|

If the medical establishment wasn't so medical, |

|

229 |

|

they could treat pregnancy as something that |

|

230 |

|

happens |

|

231 |

|

instead of as an illness. [15] |

Following RICHARDSON (1993), we used creative analytic practice (CAP) to assemble this poetic representation of our participants' stories. This allowed us to contextualize their narratives, honoring the nuanced layers of their experiences, opinions, and desires. As CHAWLA (2008) explains, the poem "moves back and forth between description, voice, and interpretation" (§40), facilitating conversations about the various intricately connected discourses at work in the women's lives, which inform our discussion. [16]

By default, our selection criteria for participants necessitated that the women who we interviewed were well-positioned (and privileged) to attempt to either work outside of, or fight against, the medicalization of pregnancy and childbirth. Our participants engaged in a significant amount of self-education prior to and throughout the pregnancy (lines 25-36, 47-52), including reading and watching women-based books and documentaries, connecting with like-minded women in their communities and on social media, contacting local midwives and doulas. They refused to believe and actively resisted fear-based messages propagated by their doctors, the media, traditional birthing classes etc. In these messages, childbirth is conceptualized as pathological (CHADWICK & FOSTER, 2014) and as an inevitably medicalized process that is inherently harmful to the child and the mother (FAHY & PARRATT, 2006; FOX & WORTS, 1999). Instead, the women sought out their own sources of information in attempts to better understand alternative conceptualizations of childbirth, conceptualizations not reliant on unnecessarily invasive medical interventions. The women's stories are inspiring in this way; regardless of how institutionalized the medicalization of pregnancy and childbirth were within their social and cultural context, they attempted to resist this through self-education, personal advocacy, and networking with other like-minded women and natural childbirth advocates (lines 83-86, 142-145). For example, as reflected in the poem, our participants had engaged in substantial self-education throughout their pregnancy on birth options and had inquired about them with local medical providers (lines 22-28). However, as shown through the juxtaposition of the right and left sides of the poem, the women's desires for natural childbirth were often impossible (due to structural constraints), seen as unnecessary, or not taken seriously by their nurses and/or physicians, undermining their ability to enact what they learned through self-education (lines 108-115, 132-140, 181-188, 203, 215-217). [17]

Although the women tried to enact agency and create an environment conducive to fulfilling their wishes to have a non-medicalized birth, they were often unsuccessful for a myriad of reasons. Time and again in their narratives, they provided examples of how their preparation and personal empowerment were superseded by individuals and medical institutions that enacted a technocratic model of pregnancy and childbirth (DAVIS-FLOYD, 2001). For example, one of the women was forced to pick an induction date, despite her wishes to have a drug- and intervention-free childbirth (lines 11-15). Here, the doctor prioritized her own work schedule over the wishes of the woman. Similarly, another of our participants was "stretched" (an intervention during which the membrane is separated from the amniotic sac, thereby inducing labor) by her doctor without her consent, which subsequently started her labor (lines 59-67). Although this procedure does not involve drugs or medication, it can still be classified as an unnecessary and invasive intervention, particularly if it is done without the knowledge or consent of the woman. One of our other participants had a similar, yet more offensive, non-consensual medical intervention. The doctor performed an episiotomy without her knowledge or consent while she was pushing (lines 184-190). This was done in spite of the fact that her birth plan explicitly stated that she wanted no medical interventions. Another woman who also explicitly delineated her wish to have a drug-free, natural childbirth in her birth plan, and who reiterated that wish immediately upon her arrival at the hospital, was given Pitocin upon her admittance to the hospital (lines 105-122). Again, this was a non-consensual intervention, and she was ridiculed by the administering nurse when she attempted to resist the procedure. This specific situation is illustrated in the third frame of our introduction. [18]

At the most basic level, performing non-consensual medical procedures and interventions on women is both illegal and unethical (LOTHIAN, 2012; O'CATHAIN, THOMAS, WALTERS, NICHOLL & KIRKHAM, 2002). In fact, the Committee on Ethics of the AMERICAN CONGRESS OF OBSTETRICIANS AND GYNECOLOGISTS [ACOG] (2007) insists that informed consent reaches far beyond the formality of a signed consent form and is a required, essential practice to protect the respect for pregnant and laboring women's autonomy. Quoting JONSEN, SIEGLER and WINSLADE's (2006) work on clinical ethics, the Committee defines informed consent as "the willing acceptance of a medical intervention by the patient after adequate disclosure by the physician of the nature of the intervention with its risks and benefits and the alternatives with their risks and benefits" (in ACOG, 2007, p.5). Unfortunately, as research shows and is reflected in our data, non-consensual medical interventions on pregnant and birthing women appear to be a common occurrence and, at times, routinized within hospital policies and procedures (BUECHLER, 2007; DAVIS-FLOYD, 2001; DIAZ-TELLO, 2016). Informed consent is a basic standard of medical care throughout the world, and, revisiting BINGHAM et al. (2011), we contend that non-consensual medical intervention during labor and birth constitute a human rights abuse/violation. [19]

Interestingly, some of the women who we interviewed seemed to have come to terms with their experiences of non-consensual medical interventions, and this was often done when the women realized, as one of them explained, that "it could have been something a lot worse" (line 189-190, 29-36). In other words, because of their self-education, the women knew that invasive, non-consensual medical interventions are common experiences for many birthing women in the United States, and they even described feelings of relief when the interventions they were subjected to were not too invasive. These sentiments reflect a commonsensical belief within the United States that as long as the birthing experience produces a "healthy baby," then the experiences, emotions, or desires of the birthing woman would come secondary to the perceived needs of the baby (lines 117-122, see also BECK, 2004; BORDO, 2003; SCHILLER, 2015). Our participants' complicity with, or resignation to, this widespread understanding is a clear indictment against what is considered acceptable standards of practice for birthing women. An alarmingly high number of birthing women in the United States suffer trauma during and immediately after the birth of their babies (lines 199-213, see also BECK, 2006, 2011; CHADWICK, COOPER & HARRIES, 2014; SIMKIN, n.d.), sometimes resulting in symptoms most commonly associated with war veterans' diagnoses of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). The fact that postnatal women and war veterans can experience similar, trauma-induced medical symptoms is a clear signal that our current medical institutions are failing women. [20]

One way some communities within the U.S. address this issue is by creating alternative spaces for women to give birth, such as birthing centers and with the help of midwives and doulas. Unfortunately, for the women in our study, there were no alternative spaces to birth outside of the technocratic model of childbirth since there are currently no birth centers or standardized doula services in the city, and only one hospital that provides nurse-midwives. As our composite poem shows, although most of the women in our study expressed their desire to birth naturally with access to a midwife or doula (lines 53-58, 94-95), they did not see homebirth as a viable option (lines 16-19, 25-28). Time and again, women were scared to birth at home and expressed their desire for the hospital environment to be altered in order to facilitate the kind of birth they desired (lines 22-24, 47-58, 94-95, 132-140, 181-183, 203, 214-217). Even though they knew that hospitals most likely could not, or would not, provide them the type of environment conducive to birthing drug-free, the women still chose to subject themselves to the technocratic model of birth that the hospitals fostered despite their understanding that this exponentially increased their chances of medical intervention. We found this simultaneously perplexing and understandable. It was perplexing because research strongly suggests that out-of-hospital births are just as, if not more so, safe as in-hospital births for women with low-risk pregnancies (GIBBONS et al., 2010; MacDORMAN et al., 2013; RYAN, SCHNATZ, GREENE & CURRY, 2005; TRACY, SULLIVAN, WANG, BLACK & TRACY, 2007) and, as was discussed earlier, the women in our study had done a significant amount of self-education prior to and during pregnancy. The women's wishes to birth in a hospital were understandable, though, because of the prevalence of negative representations and misunderstandings of home birth that circulate both nationally and locally (HAPPEL-PARKINS & AZIM, 2016). Home birth is often described as potentially harmful to the child and to the mother's well-being, and women who choose to birth at home are regularly labeled as selfish and accused of putting their own needs ahead of those of their baby (DAVIS, 2004; FAHY & PARRATT, 2006). For many women, including those in our study, home birth may even be unrealistic since their insurance companies refuse to cover any of the midwifery services associated with a home birth (lines 16-21) (for two of the largest insurance companies' stances, see AETNA, 2016; CIGNA, 2014). Regardless of the reasons for choosing to birth in the hospital, we suggest that this choice positioned women as simultaneously resisting and perpetuating the very discourses that curtailed their options and choices. Their choice to give birth in a hospital inevitably gave power to the very institutions and discourse they actively tried to resist. [21]

A final important point to note is that, while the analysis here focuses on individual women's stories and experiences, the context surrounding these women was created by a number of structural and institutional forces that need to be challenged and ultimately revisioned and reconstituted. The poem ends with a structural critique of the medical establishment that was shared by our participants (lines 214-231). It illustrates the mechanisms that facilitate the disempowerment women often feel when childbirth is overly medicalized. While it is not within the scope of this article to address specific recommendations or action plans here, future research could explore the institutional culture and policies that lead to nurses being over-worked and under-valued (DRAKE, LUNA, GEORGES & STEEGE, 2012), the arguable miseducation that doctors and nurses receive about natural childbirth (STAPLETON, KIRKHAM & THOMAS, 2002), and the overall culture (including cultural norms, national discourses, media representations, etc.) of medicalization of pregnancy and childbirth (HADFIELD, RUDOE & SANDERSON-MANN, 2007; MORRIS & McINERNEY, 2010) that informs decision-making at every level. [22]

6. (Re)Presenting Birth Differently

Experiences are nuanced, complex, and sometimes contradictory. Contrary to the assumptions that undergird traditional, thematic representations of qualitative data, people's experiences often cannot, and should not, be encapsulated in easily digestible, unidimensional representations. We sought to (re)present the women's narratives and experiences in an accessible way that respected the emotionality and complexities often present in the women's narrations of their birthing experiences. The poem illustrated how they sought to navigate institutional spaces in which they often felt ignored, unheard, or marginalized. It also showed the effects the women's various decisions had on their experiences and postpartum reflections. [23]

The act of co-creating the composite poem was a productive step in our data analysis. Engaging in the physical act of cutting out data slices, arranging and rearranging them, and negotiating our way through the creation of the four different sections of the poem facilitated analysis in ways we did not initially understand or recognize. This process helped us to acknowledge and examine similarities, overlaps, commonalities, differences, and contradictions in the women's experience. We were continuously reminded of the complexities of the embodied and emotional experiences that are inherently part of pregnancy and birth but often omitted from birth narratives (CHADWICK, 2009). [24]

Once we began to recognize that all the participants narrated what we first labeled as "wish data," data that described desires or longing for experiences that, for whichever reason, could not be actualized, we then made an effort to read for instances of desirous/future-orientated/not-actualized speech. This data is often excluded from analysis since it does not represent an actualized experience (VISWESWARAN, 1994). We decided to incorporate these parts of our participants' narratives, which can be seen in how the composite poem focused on both the participants' actualized experiences, and on their memories and desire for different, or even future, experiences. These data were often expressed through emotive and/or sensual language. ST. PIERRE (1997) describes this as transgressive data—data that are often ignored or silenced within traditional representations that seek to conform to post-positivist understandings of validity or trustworthiness. Arguing for the inclusion of such transgressive data, ST. PIERRE suggests we be "suspicious of everyday language" (p.175) and the omissions or refusals encouraged by traditional data analysis and representation. In research with women's experiences of pregnancy and childbirth, traditional representations of data can work to mute or even silence the emotional tenor and embodied understandings prevalent in women's narratives. The composite poem works to honor transgressive data, particularly emotional and sensual data, while also creating new understandings through alternative (re)presentations. DEMMER (2016) emphasizes the necessity for researchers to incorporate physical and bodily sensations into the research as part of meaningful data. While we did not collect this type of data through, for example, observations and specific interrogations of present embodied sensations during the interview, we did privilege the participants' descriptions of their embodied experiences and centered them through the use of poetic representation. In fact, using CAP allowed us to move beyond a factual account of the women's experiences and even beyond an examination of structural and institutional influences. Instead, our (re)presentation helped us explore the entanglements (BARAD, 2007) of a multitude of factors, including the women's range of emotions, geographical context, socio-economic status, questions, family expectations, personal wishes and desires, insecurities, celebrations, self-education, etc. [25]

As is true of all methods of analysis and representation, research poems generate issues even as they address or challenge common critiques of traditional analysis and representation (PREISSLE, 2006). On the one hand, while this representation attended to important contextual details, there was still a reduction of the data that some find problematic. This feature is inherent to poetic representation (SZTO et al., 2005) and, coupled with the overt subjective liberty afforded to the authors through the use of CAP, is vulnerable to critique from those situated within objectivist or post-positivist epistemological and methodological traditions (KORO-LJUNGBERG, YENDOL-HOPPEY, SMITH & HAYES, 2009). On the other hand, as has been explored, poetic representation of narrative data can be accessible to a wider audience than traditional analysis and representation. It can also be a space in which emotions are demarginalized and validated. [26]

As the poem illustrates, women simultaneously work within and against the personal, local, national, and discursive limits within which they are entangled. The composite poem allows for these complexities of women's experiences to be honored by creating space for emotional and sensual data—data which represent different, equally important, ways of knowing too often ignored or bracketed within traditional research. Alternative approaches to data analysis and (re)presentation, as presented through the composite poem, can ameliorate these omissions and demarginalize transgressive data. [27]

1) Pitocin is a synthetic oxytocin that is generally administered intravenously to induce, progress, and augment labor contractions. <back>

2) See https://www.birthcenteraccreditation.org/find-accredited-birth-centers/#mapkeycabc [Accessed: February 24, 2017]. <back>

Aetna (2016). Home births, No. 0329, April 19, http://www.aetna.com/cpb/medical/data/300_399/0329.html [Accessed: September 7, 2016].

Allen, Sarah (1998). A qualitative analysis of the process, mediating variables and impact of traumatic childbirth. Journal of Reproductive and Infant Psychology, 16(2-3), 107-131.

American Congress of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) (2007). ACOG Committee Opinion No. 390: Ethical decision making in obstetrics and gynecology. Obstetrics & Gynecology, 110(6), 1479-1487.

Barad, Karen (2007). Meeting the universe halfway: Quantum physics and the entanglement of matter and meaning. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

Beck, Cheryl T. (2004). Birth trauma: In the eye of the beholder. Nursing Research, 53(1), 28-35.

Beck, Cheryl T. (2006). Pentadic cartography: Mapping birth trauma narratives. Qualitative Health Research, 16(4), 453-466.

Beck, Cheryl T. (2011). A metaethnography of traumatic childbirth and its aftermath: Amplifying causal looping. Qualitative Health Research, 21(3), 301-311.

Berbary, Lisbeth A. (2011). Post-structural writerly representation: Screenplay as creative analytic practice. Qualitative Inquiry, 17(2), 186-196.

Berbary, Lisbeth A. (2012). "Don't be a whore, that's not ladylike:" Discursive discipline and sorority women's gendered subjectivity. Qualitative Inquiry, 18(7), 606-625.

Bingham, Debra; Strauss, Nan & Coeytaux, Francine (2011). Maternal mortality in the United States: A human rights failure. Contraception, 83(3), 189-193.

Bordo, Susan (2003). Unbearable weight: Feminism, Western culture, and the body. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

Boucher, Debora; Bennett, Catherine; McFarlin, Barbara & Freeze, Rixa (2009). Staying home to give birth: Why women in the United States choose home birth. Journal of Midwifery & Women's Health, 54(2), 119-126.

Buechler, Elizabth J. (2007). Informed consent challenges in obstetrics. CRICO, 25(3), 19-20.

Butler-Kisber, Lynn (2002). Artful portrayals in qualitative inquiry: The road to found poetry and beyond. Alberta Journal of Educational Research, 48(3), 229-239.

Butler-Kisber, Lynn (2010). Qualitative inquiry: Thematic, narrative and arts-informed perspectives. London: Sage.

Chadwick, Rachelle J. (2009). Between bodies, cultural scripts and power: The reproduction of birthing subjectivities in home-birth narratives. Subjectivity, 27(1), 109-133.

Chadwick, Rachelle J. & Foster, Don (2014). Negotiating risky bodies: Childbirth and constructions of risk. Health, Risk & Society, 16(1), 68-83.

Chadwick, Rachelle J.; Cooper, Diane & Harries, Jane (2014). Narratives of distress about birth in South African public maternity settings: A qualitative study. Midwifery, 30(7), 862-868.

Charmaz, Kathy (2012). Writing feminist research. In Sharlene Nagy Hesse-Biber (Ed.), The handbook of feminist research: Theory and praxis (2nd ed., pp.475-494). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Chase, Susan E. (2005). Narrative inquiry: Multiple lenses, approaches, voices. In Norman K. Denzin & Yvonna S. Lincoln (Eds.), The Sage handbook of qualitative research (3rd ed., pp. 651-679). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Chawla, Devika (2008). Poetic arrivals and departures: Bodying the ethnographic field in verse. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung / Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 9(2), Art. 24, http://nbn-resolving.de/urn:nbn:de:0114-fqs0802248 [Accessed: September 15, 2016].

Chen, Alice; Oster, Emily & Williams, Heidi (2015). Why is infant mortality higher in the US than in Europe? American Economic Journal: Economic Policy, 8(2), 89-124.

Childbirth Connect (2012). United States maternity care facts and figures, http://transform.childbirthconnection.org/wp-content/uploads/2012/12/maternity_care_in_US_health_care_system.pdf [Accessed: September 7, 2016].

Cigna (2014). Cigna administrative policy: Home birth, January 15, https://www.supercoder.com/webroot/upload/general_pages_docs/document/AD_A002_administrativepolicy_home_birth.pdf [Accessed: September 6, 2016].

Clandinin, D. Jean & Connelly, F. Michael (2004). Narrative inquiry: Experience and story in qualitative research. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Davis, Elizabeth (2004). Heart and hands: A midwife's guide to pregnancy and childbirth. Berkeley, CA: Celestial Arts.

Davis-Floyd, Robbie (2001). The technocratic, humanistic, and holistic paradigms of childbirth. International Journal of Gynecology and Obstetrics, 75, S5-S23.

Demmer, Christine (2016). The interview situation and experiences of the body; Enriching biographical research processes by

the inclusion of sensory perception. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung / Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 17(1), Art. 13,

http://nbn-resolving.de/urn:nbn:de:0114-fqs1601139 [Accessed: September 9, 2016].

Diaz-Tello, Farah (2016). Invisible wounds: Obstetric violence in the United States. Reproductive Health Matters, 24(47), 56-64.

Drake, Diane A.; Luna, Michele; Georges, Jane M., & Steege, Linsey M.B. (2012). Hospital nurse force theory: A perspective of nurse fatigue and patient harm. Advances in Nursing Science, 35(4), 305-314.

Ellis, Carolyn (2004). The ethnographic I: A methodological novel about autoethnography. Walnut Creek, CA: AltaMira Press.

Fahy, Kathleen M. & Parratt, Jenny A. (2006). Birth territory: A theory for midwifery practice. Women & Birth, 19(2), 45-50.

Finerman, Ruthbeth; Williams, Charles & Bennett, Linda A. (2010). Health disparities and engaged medical anthropology in the United States Mid-South. Urban Anthropology, 39(3), 265-297.

Fox, Bonnie & Worts, Diana (1999). Revisiting the critique of medicalized childbirth: A contribution to the sociology of birth. Gender and Society, 13(3), 326-346.

Furman, Rich (2006). Poetic forms and structures in qualitative health research. Qualitative Health Research, 16(4), 560-566.

Gaskin, Ina May (2011). Birth matters: A midwife's manifesta. New York, NY: Seven Stories Press.

Glesne, Corrine (1997). That rare feeling: Re-presenting research through poetic transcription. Qualitative Inquiry, 3(2), 202-221.

Gibbons, Luz; Belizán, José M.; Lauer, Jeremy A.; Betrán, Ana P.; Merialdi, Mario & Althabe, Fernando (2010). The global numbers and costs of additionally needed and unnecessary caesarean sections performed per year: Overuse as a barrier to universal coverage. World Health Report, Background Paper, No. 30, http://www.who.int/healthsystems/topics/financing/healthreport/30C-sectioncosts.pdf [Accessed: March 9, 2017].

Goodman, Steffie (2007). Piercing the veil: The marginalization of midwives in the United States. Social Science & Medicine, 65(3), 610-621.

Hadfield, Lucy; Rudoe, Naomi & Sanderson-Mann, Jo (2007). Motherhood, choice and the British media: A time to reflect. Gender Education, 19(2), 255-263.

Hamilton, Brady; Martin, Joyce & Ventura, Stephanie (2013). Births: Preliminary data for 2010. National Vital Statistics Report, 62(3). Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/nvsr/nvsr62/nvsr62_03.pdf [Accessed: March 9, 2017].

Happel-Parkins, Alison & Azim, Katharina A. (2016). At pains to consent: A narrative inquiry into women's attempts of natural childbirth. Women & Birth, 29(4), 310-320.

Hodges, Susan (2009). Abuse in hospital-based birth settings?. Journal Perinatal Education, 18(4), 8-11.

Inch, Sally (1981). Birthrights. London: Hutchinson.

Janesick, Valerie J. (2016). Poetry inquiry: Transforming qualitative data into poetry. In Norman K. Denzin & Michael D. Giardina (Eds.), Qualitative inquiry through a critical lens (pp. 59-72). New York: Routledge.

Koro-Ljungberg, Mirka; Yendol-Hoppey, Diane; Smith, Jason Jude & Hayes, Sharon B. (2009). Epistemological awareness, instantiation of methods, and uninformed methodological ambiguity in qualitative research projects. Educational Researcher, 38(9), 687-699.

Lahman, Maria K.E.; Rodriguez, Katrina L.; Richard, Veronica M.; Geist, Monica R.; Schendel, Roland K. & Graglia, Pamela E. (2011). (Re)Forming research poetry. Qualitative Inquiry, 17(9), 887-896.

Langer, Carol L. & Furman, Rich (2004). Exploring identity and assimilation: Research and interpretive poems. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung / Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 5(2), Art. 5, http://nbn-resolving.de/urn:nbn:de:0114-fqs040254 [Accessed: September 15, 2016].

Lincoln, Yvonna S. & Guba, Egon G. (2005). Paradigmatic controversies, contradictions, and emerging confluences. In Norman K. Denzin & Yvonna S. Lincoln (Eds.), The Sage handbook of qualitative research (3rd ed., pp.191-216). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Lothian, Judith A. (2012). Risk safety, and choice in childbirth. Journal of Perinatal Education, 21(1), 45-47.

MacDorman, Marian F.; Declercq, Eugene & Mathews, T.J. (2013). Recent trends in out-of-hospital births in the United States. Journal of Midwifery & Women's Health, 58(5), 494-501.

Madi, Banyana C. & Crow, Rosemary (2004). A qualitative study of information about available options for childbirth venue and pregnant women's preference for a place of delivery. Midwifery, 19(4), 328-336.

Mansfield, Becky (2008). The social nature of natural childbirth. Social Science & Medicine, 66(5),1084-1094.

Miller, Amy C. & Shriver, Thomas E. (2012). Women's childbirth preferences and practices in the United States. Social Science & Medicine, 75(4), 709-716.

Morris, Theresa & McInerney, Katherine (2010). Media representations of pregnancy and childbirth: An analysis of reality television programs in the United States. Birth, 37(2), 134-140.

O'Cathain, Alicia; Thomas, Kate; Walters, Stephen J.; Nicholl, Jon & Kirkham, Mavis (2002). Women's perceptions of informed choice in maternity care. Midwifery, 18(2), 136-144.

Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) (2013). Health at a glance 2013: OECD indicators, https://www.oecd.org/els/health-systems/Health-at-a-Glance-2013.pdf [Accessed: September 10, 2016].

Parry, Diana C. & Glover, Troy D. (2011). Living with cancer? Come as you are. Qualitative Inquiry, 17(5), 395-403.

Parry, Diana C. & Johnson, Corey W. (2007). Contextualizing leisure research to encompass complexity in lived leisure experience: The need for creative analytic practice. Leisure Science, 29(2), 119-130.

Patton, Michael Q. (1990). Qualitative evaluation and research methods. Newbury Park, CA: Sage.

Poindexter, Cynthia Cannon (2002). Research as poetry: A couple experiences HIV. Qualitative Inquiry, 8(6), 707-714.

Preissle, Judith (2006). Feminist research ethics. In Sharlene Hesse-Biber (Ed.), Handbook of feminist research: Theory and praxis (1st ed., pp.515-532). London: Sage.

Raisler, Jeanne (2000). Midwifery care research: What questions are asked? What lessons have been learned? Journal of Midwifery and Women's Health, 45(1), 20-36.

Richardson, Laurel (1993). Poetics, dramatics, and transgressive validity: The case of the skipped line. The Sociological Quarterly, 34(4), 695-710.

Richardson, Laurel (2000). Evaluating ethnography. Qualitative Inquiry, 6(2), 253-255.

Richardson, Laurel & St. Pierre, Elizabeth A. (2005). Writing: A method of inquiry. Norman K. Denzin & Yvonna S. Lincoln (Eds.), The Sage handbook of qualitative research (3rd ed., pp.959-978). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Riessman, Catherine K. (2008). Narrative methods of the human sciences. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Ryan, Kristi; Schnatz, Peter; Greene, John & Curry, Stephen (2005). Change in Cesarean section rate as a reflection of the present malpractice crisis. Connecticut Medicine, 69(3), 139-141.

Saldaña, Johnny (2009). The coding manual for qualitative researchers. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Schiller, Rebecca (2015). All that matters. Women's rights in childbirth. Guardian Shorts.

Simkin, Penny (n.d.). What to do during a traumatic labor and birth to reduce the likelihood of later Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder. Prevention and Treatment of Traumatic Childbirth (PATTCh), http://pattch.org/resource-guide/what-to-do/ [Accessed: September 5, 2016].

Sparkes, Andrew C. (2008). Sports and physical education: Embracing new forms of representation. In J. Gary Knowles & Ardra L. Cole (Eds.), Handbook of the arts in qualitative research (pp.653-664). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

St. Pierre, Elizabeth A. (1997). Methodology in the fold and the irruption of transgressive data. International Journal of Qualitative Studies in Education, 10(2), 175-189.

Stapleton, Helen; Kirkham, Mavis & Thomas, Gwenan (2002). Qualitative study of evidence based leaflets in maternity care. British Medical Journal, 324(7338), 639-643.

Szto, Peter; Furman, Rich & Langer, Carol (2005). Poetry and photography: An exploration into expressive/creative qualitative research. Qualitative Social Work, 4(2), 135-156.

Tracy, Sally K. & Tracy, Mark B. (2003). Costing the cascade: Estimating the cost of increased obstetric intervention in childbirth using population data. BJOG: An International Journal of Obstetrics & Gynaecology, 110(8), 717-724.

Tracy, Sally K.; Sullivan, Elizabeth; Wang, Yueping A.; Black, Deborah & Tracy, Mark (2007). Birth outcomes associated with interventions in labour amongst low risk women: A population-based study. Women & Birth, 20(2), 41-48.

Visweswaran, Kamala (1994). Fictions of feminist ethnography. Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press.

World Health Organization (WHO) (2009). Monitoring emergency obstetric care: A handbook. Department of Reproductive Health Care, Geneva, http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/44121/1/9789241547734_eng.pdf [Accessed: September 10, 2016].

Dr. Alison HAPPEL-PARKINS is an assistant professor in counseling, educational psychology and research at the University of Memphis, Tennessee, USA. Her empirical work centers around women's health and reproductive rights, and her theoretical work uses ecocritical and ecofeminist frameworks to interrogate K-12 public school curriculum and practices in the USA.

Contact:

Alison Happel-Parkins

Counseling, Educational Psychology and Research

University of Memphis

College of Education

100 Ball Hall

Memphis, TN USA 38152

Tel: + 1 901 678 2841

E-mail: aahappel@memphis.edu

Dr. Katharina A. AZIM is a clinical lecturer in psychology at the University at Buffalo (SUNY), New York, USA. Her academic interests center on ethnic identity and Middle Eastern-North African/Arab/Muslim psychology, on the one hand, and women's reproductive health, agency, and rights in the USA, on the other. Methodologically, she uses postcolonial feminist and poststructural theories, narrative inquiry, and autoethnography.

Contact:

Katharina A. Azim

Department of Psychology

University at Buffalo (SUNY)

346 Park Hall

Buffalo, NY USA 14260

Tel.: +1 716 645 0226

E-mail: kbarth@buffalo.edu

Happel-Parkins, Alison & Azim, Katharina A. (2017). She Said, She Said: Interruptive Narratives of Pregnancy and Childbirth

[27 paragraphs]. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung / Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 18(2), Art. 9,

http://nbn-resolving.de/urn:nbn:de:0114-fqs170290.