Volume 18, No. 2, Art. 1 – May 2017

Knowing Through Improvisational Dance: A Collaborative Autoethnography

Trish Van Katwyk & Yukari Seko

Abstract: This article is a collaborative autoethnographic reflection about two dance-based research projects. Our objectives for the projects were two-fold: to practice knowledge production and mobilization in a way that diverged from dominant traditional Western scholarship, and to re-examine our engagement with the self-injury focus of previous research. With our collaborative meaning making came new dilemmas and unanticipated relationship development. Through dance and collaborative writing, we discovered a vulnerability that could cast doubt on dominant knowledge practices. As a relational praxis, two stories converged to facilitate critically reflexive perspectives and less dominant ways of knowing directed toward social justice.

Key words: collaborative autoethnography; arts-based methods; dance-based research; knowledge practices; social justice

Table of Contents

1. Prologue

2. Phase One: Shall We Dance?

2.1 Trish: Excerpts from personal journal after the first dance workshop

2.2 Yukari: Self-reflection after the first dance workshop

3. Phase Two: Let the Dance Begin

3.1 Yukari: Excerpts from personal journal after the first dance workshop

3.2 Trish: Self-reflection during collaborative writing

4. Phase Three: Knowing Through Dancing

4.1 Yukari: Excerpts from personal journal after the second dance workshop

4.2 Trish: Excerpts from individual journal after the second dance workshop

5. Epilogue

5.1 Trish: Self-reflection during collaborative writing

5.2 Yukari: Self-reflection during collaborative writing

Appendix: "i could not read them" by Gabrielle VEGA (2007)

Knowledge and power are intertwined, so that those to whom power has been attributed are able to authenticate, validate and operationalize knowledge to uphold power relations (FOUCAULT, 1980). FOUCAULT's exploration into the symbiotic relationship between knowledge and power has inspired critical thinkers striving to unsettle the social constellations of power relations. Indigenous, feminist, queer, postcolonial, critical race, and critical disability studies are among the many that have explored deeply how the lives of individuals and communities most susceptible to oppressive knowledge practices have been altered, intruded upon, violated, and discarded. [1]

As researchers and academics, we find ourselves enmeshed in dominant knowledge practices as we progress through the ranks of academic achievement. We are now teaching these practices to students entering academia. Discomforts about the exclusive nature of some of these practices have caused each of us to pause. Yet, the pressures to soldier on without resistance are hard to ignore, particularly as we are both early in our academic careers and face the risk of refusal as our progress lies in the hands of more powerful players. While these pressures are persuasive, we remain compelled by the possibilities of less dominant ways of knowing that lay outside of the traditional academic worldview. [2]

Our dissatisfaction with positivist/objectivist epistemology resonates strongly with the recent call by qualitative researchers for alternative methods of inquiry (AUGUSTINE, 2014; BRIDGES-RHOADS, 2015; DENZIN, LINCOLN & GIARDINA, 2006; HOLBROOK & POURCHIER, 2014; ST. PIERRE & JACKSON, 2014; TUCK & YANG, 2014). These critical thinkers call into question traditional ways of doing science and highlight the researcher's subjective position that is always in flux and shifting over the course of research. They also express skepticism toward the tendency in science to reduce rich human experiences into flat "codes." ST. PIERRE and JACKSON (2014) describe it as "a superficial marker of a positivist scientism that appeals to certain social scientists who demand 'systematicity,' however mindless, in the name of ‘science" (p.715). When participants' life experiences are captured and then coded by researchers who dissect and filter data to create "evidence-based" knowledge, the end product often becomes unmoored from its original form. Such a process is convincingly described as a colonizing practice, with life stories being invaded in order to become a commodity territory of the researcher (HOLBROOK & POURCHIER, 2014; TUCK & YANG, 2014). [3]

One alternative inquiry rapidly growing in social and health sciences is arts-based research (BOYDELL, GLADSTONE, VOLPE, ALLEMANG & STASIULIS, 2012). Those seeking to understand rich and multiple dimensions of human experiences have turned to various arts-based approaches such as photography (PEARCE & COHOLIC, 2013; WANG & BURRIS, 1997), video (BRICKELL & GARRETT, 2015), theater (WHITE & BELLIVEAU, 2011), and dance (BLUMENFELD-JONES, 1995; YLÖNEN, 2003), to the extent that there remains almost no form of art unexplored as an arts-based research approach. Performative social science (PSS) is particularly concerned with the fusion of performance arts and social science (GERGEN & GERGEN, 2010; GUINEY YALLOP, LOPEZ DE VALLEJO & WRIGHT, 2008; JONES & LEAVY, 2014). These methods have shown to be valuable for embracing "emotional, sensory, embodied and imaginative ways of knowing that lend to richer knowledge production and communication processes" (BLODGETT et al., 2013, p.312). [4]

As non-artist social science researchers, the opportunity to experiment with dance-based research came to us rather unexpectedly, when Trish began collaborating with a professional dancer/choreographer to develop a dance project featuring youth mental health. Yukari's qualitative research on self-injury among youth initially served as the data to be represented. We received funding to collaboratively create a performative piece that used improvisational dance to represent the themes that had emerged from Yukari's research. Our decision to dance by ourselves—rather than having trained dancers perform on our behalf or asking young people who self-injure to dance their own stories– opened us up to an unanticipated way of knowing that included particular dilemmas and intimacies in our research relationships. We used autoethnography (ELLIS, 2004; ELLIS, ADAMS & BOCHNER, 2011) to more fully explore the vulnerability we experienced as novice dancers/social science academic researchers. Autoethnography is a qualitative research methodology where a researcher explores her/his unique life experiences in the context of the social and cultural institutions that have shaped the world the researcher inhabits (CUSTER, 2014). As autoethnographers, we intentionally exposed ourselves to our own vulnerability in order to critically (re)consider the social and cultural realities and inequalities that are created by the web of relationships in which we are embedded (MANOVSKI, 2014). As researcher-dancers conducting an autoethnography about that experience, we found ourselves in the enigmatic position of the "objecting object" (TUCK & YANG, 2014, p.814), that is, objecting to becoming mere objects of a research study. There was a dissonance that came out of choosing to be the medium and objects of our research, while objecting to research practices that potentially diminish the life experiences being studied. Although this dissonance is characteristic of autoethnographic inquiry, it nonetheless exposed us to our own vulnerability and insecurity. [5]

In this article we reflect on our experiences in the two dance-based studies, exploring how each of us differently approached this embodied mode of knowing to co-construct a shared knowledge. In the first dance-based study, we used dance to mobilize the knowledge that had been produced about self-injury in an earlier research study (SEKO, 2013; SEKO, KIDD, WILJER & McKENZIE, 2015). The exploration was focused on the impact on the researcher of "dancing data." In the second dance-based study, we explored the quality of the knowledge that is produced through dance, through the presentation of a performance inspired by a poem about self-injury (SEKO & VAN KATWYK, 2016). We chose to employ the method of collaborative autoethnography (CHANG, AMBURA, NGUNJIRI & HERNANDEZ, 2012; GALE, PELIAS, RUSSELL, SPRY & WYATT, 2013; GARBATI & ROTHSCHILD, 2016; PENSONEAU-CONWAY, BOLEN, TOYOSAKI, RUDICK & BOLEN, 2014; TOYOSAKI, PENSONEAU-CONWAY, WENDT & WEATHERS, 2009) to obtain an intimate and in-depth understanding of each other's experiences, and assigned ourselves as both the researchers and the objects of research. Following TOYOSAKI et al.'s (2009) innovative method of collaborative autoethnography, we intend our collaborative writing to be an act of self-construction and self-discovery, as well as a relationship-building activity, through which we share with readers an "insider" perspective as academics/researchers co-learning from each other's experience. [6]

Autoethnography founder Carolyn ELLIS (2004) insists that it is through autoethnography that we, the researchers, must interrogate and challenge ourselves in our capacity to actively reproduce a social system that is unjust and inequitable (p.10). Without critical self-observation, our efforts towards change remain superficial (BAUDER & ENGEL-DI MAURO, 2008). Collaborative autoethnography strengthens the critical approach to knowledge production, thus further challenging the relations that would lay claim to an individualized account of knowledge (GALE et al., 2013). [7]

Our autoethnographic exploration commenced immediately after the completion of the second dance project in Winter 2015. We began individually journaling our own experiences, and then wrote together to exchange personal and theoretical reflections on each other's writing. During the interim of our weekly writing meetings, we also shared a Google document to continue our collaboration. This served as a unique space for collaborative writing, as the technology enabled us to simultaneously work on the same document and instantly see the changes made by the other. We did not contract a curating/writing process ahead of time. The first author began the writing process with an extended, reflexive personal narrative and the skeleton of a literature review. She suggested a mirroring process, and the second author added her reflexive personal narratives to the written piece. As we began to weave together our personal narratives, we brought our resources, knowledge and ideas together so that we could contextualize the personal narratives with a rich collection of works by other arts-based, autoethnographic and/or critical researchers. We both experimented with form and placement of the contextualized reflexive narratives until we found a structure that worked for both of us. It felt, at times, similar to the collaborative choreography that had occurred in the dance studio, where we experimented with collaborative movement and sequencing until we felt a resonance with what was being danced. The decisions about what text remained and what text became invisible were made by each author about her own writing, which also paralleled the solo dance process, in which each dancer made her own decisions about her personal movements. Some of these movements felt comfortable and right for the dancer, while other movements felt unsuitable or awkward and were edited out of the personal dance piece, sometimes during and sometimes after the collaborative structuring work. [8]

There are a number of tools that can be used to support collaborative autoethnographic writing. For example, GALE and his co-writers (2013) used e-mail to document their long-distance exchanges. PENSONEAU-CONWAY and her colleagues (2014) used a Google document to conduct a collaborative writing in virtual real-time. Following their steps, we decided to share a Google document as a living document where an ongoing dialogue about our writing could be facilitated, tracked and elaborated. We both felt the bizarreness of witnessing each other's writing, editing, and commenting on the virtual document as it happened as if we were writing with a ghost behind the screen, but soon appreciated the rare opportunity to engage in each other's raw writing and to literally write together. Conversing back and forth for over three months, synchronously and asynchronously, on and off-line, we came to embrace what PENSONEAU-CONWAY et al. (2014) call "the unique gift" of collaborative writing, which makes visible our relationships, renders available the "impact brought on by relationships we may have never even known we had" and creates "critical intimacy in a context of care" (p.316), as we worked together to create and develop ideas, as well as sharing the vulnerability of critical self-examination. By engaging in this intimate, time- and labor-consuming task of co-writing, we brought our relationship forth into being (PENSONEAU-CONWAY et al., 2014) and questioned our unconscious allegiance to a dominant way of knowing that renders knowledge as context-independent, objectifiable and value-free phenomenon. With a collaborative reflexive exploration, we became immersed in a context of intricate relations and connections, which in turn enabled us to co-create knowledge. [9]

2.1 Trish: Excerpts from personal journal after the first dance workshop

One of my objectives for developing the dance-based research projects was to build a portfolio of arts-based research. I was compelled by the ideas of BARONE and EISNER (2012) who encourage scholars to use arts-based methods to bring their artistic ways of thinking into their research endeavors. I was also dedicated to exploring the possibilities that exist with a wide, inclusive knowledge practice. I attempt to redress the inequities created by omissions and disregard of knowledges that lay outside of a Euro-Western ontology that ruptures connections between being and doing in the surrounding environment. My research is collaborative and participatory, and my methods have included canoeing, dancing, cartooning, and sculpting. [10]

Profoundly aware that my activities run counter to a culture of deeply embedded norms, exchanges and assumptions, while supported at the institutional level, I have experienced in my activities a sense of the absurd and a non-belonging that unsettles my sense of identity. [11]

By exploring art as knowledge, I began a consideration of an alternative epistemology and, for a moment, decentralize Western epistemology (ANDREWS, 2009; DENZIN & LINCOLN, 2011). My position as a faculty member at a university has been built upon Western notions of knowledge, so that the training I have received and now provide is immersed in this one way of knowing (BATTISTE, 2002; BHATTACHARYYA, 2013; CUTFORTH, 2013; DENZIN & LINCOLN, 2011; MARTINEZ, 2013). Shifting to a space for another way of knowing threatens to destabilize a structure that may come crashing down—on my shoulders, on my privilege and status, and on my secure place within the academic construct as it stands. With this collaborative autoethnography, I questioned my own place of privilege within a system that is built upon a set of assumptions about knowledge and validity, whose tenacity and capacity burrow so deep within my bone marrow that I have only barely begun to perceive them. Of these assumptions, MANOVSKI (2014) writes:

"This is a set of beliefs that exist in a culture and is the real story that is taken for granted, transparent, and taken as true without question: the dominant story of the culture which would be very hard to break through––an ongoing story that we are born into, if we exist in that culture" (p.38). [12]

While determined to explore the knowledge that presents itself through, becomes produced by, and emerges out of art, I discovered in this intention an aspect that feels incongruous or nonsensical.

***

Like a UFO hovering midday over a metropolitan cityscape,

or a camel with a long cat's tail swishing behind,

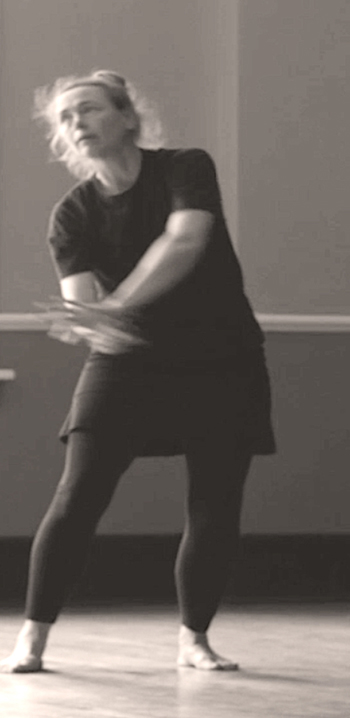

or polka dots on a large heritage home.

***

Will my efforts produce derision amongst my colleagues? Will my legitimacy as a scholar be compromised beyond recovery? Will

my promotion (security) be complicated by regretted obstacles? *** [13]

Earlier in 2015, I had developed a research proposal with a choreographer named Janet JOHNSON. She had asked if I wanted to bring dance into a support initiative for youth, although she did not have a specific initiative in mind. Shortly afterwards, Melissa ROOD, a recent graduate, approached me about being involved as a volunteer research assistant in this type of research. Melissa was actively employed in the theater industry, had received her education in a social sciences discipline, and was interested in finding ways to merge her connection to the art world with her social science education. We formed a small team of researchers who were all interested in standing on the bridge that could join the arts to the social sciences. [14]

Around that time, I was introduced to a postdoctoral researcher, Yukari SEKO, who had been studying the phenomenon of the online manifestation of self-injury for the past few years. I invited Yukari to have a conversation, in order to forge a connection that might bear some reciprocal fruit. Over coffee, Yukari described her struggles to remain self-aware of her own intentions as a researcher so that she would not cross that ethical line in the sand over into the "voyeur" region. She felt that she needed to understand more fully her engagement with the data that she had been gathering about self-injurious behavior. "Well, would you like to dance your data? I could do that with you," blurted out of my mouth. I held my breath, feeling that I had exposed a very unscholarly (and therefore, inappropriate) view of myself. Yukari was very quiet, for what seemed a very long time, then said, "Yeah, sure, I could do that." [15]

2.2 Yukari: Self-reflection after the first dance workshop

"Would you like to dance your data?"—asked Trish with a gentle smile.

***

Is she serious?***

I was caught off-guard by her invitation. Though I was aware of arts-based research, dancing my data was something that never came to my mind. I am a Communication researcher by training, having been exploring how young people with mental health difficulties express their pain on the Internet (SEKO, 2013; SEKO & LEWIS, 2016; SEKO et al., 2015). Once wearing a researcher's hat, a crown of logocentric, theory-obsessed mindset, it was hard to let my body speak on my behalf—it was beyond my imagination to let my body communicate. I was also intimidated by the idea of dancing without proper training and expertise, because the existing works that I knew were done either by professional dancers performing on behalf of non-artist researchers (BOYDELL, 2011) or by researchers who were also professional dance artists (BARBOUR, 2012; YLÖNEN, 2003).

***

Am I even qualified to "dance" my data? ... Perhaps not ... But then, Who else?*** [16]

Despite the initial apprehension, the idea of dancing my data attracted me deeply. Since 2007 I have been researching the phenomenon of self-injury, deliberate harming of one's body tissues by cutting, burning and other methods, focusing primarily on representations of self-injury shared across the Internet (SEKO, 2013; SEKO & LEWIS, 2016). Central to my inquiry has been a question as to how and why people, often anonymously, express their pain online for public consumption. Starting with personal blogs and text-based online forums, my research has gradually shifted to multimedia content-sharing platforms, where people create and post images featuring self-injury including photographs of their injured bodies. [17]

Most images I have studied for my doctoral dissertation were close-up shots of wounds and scars inscribed on bodies by their owners; some portrayed flesh and bleeding cuts, while others depicted bodies covered with countless scars and burns (SEKO, 2013). Analyzing graphic representations of self-injury was never pleasing. Although I do not have personal experience with self-injury, I often suffered from the pain emanating from the images. When observing open, bleeding wounds in particular, my skin tingled with an odd, galvanizing sensation, sending a shiver down my spine. Sometimes I even felt a cold razor blade grazing my thigh, carving words into my arm. As STRONG (1998) coined, the images cried a "bright red scream" (p.15) that somatically impacted me, triggered me to feel as if I was in their skin. [18]

But as the research progressed, my body became desensitized. As visual content was neatly coded into categories (such as body parts, methods of self-harm, conditions of injuries), I began treating the images as objective "data," rather than living documents bearing witness to poignant memories of self-injury. The more images I scrutinized, the less responsive my skin became. It was as though I was gradually stepping into the realm of "spectators" criticized by SONTAG (2003) numbing my capacity to empathize with those portrayed in the images. Although tables and graphs generated from the data convinced me that my research was progressing in a way that would satisfy my dissertation committee, I felt as though I was becoming a voyeur gazing at others' pain without taking responsibility for what was visible. With no capacity and skills to intervene, I could not help wondering, "Am I exploiting the experiences of people struggling with self-injury"? [19]

The ethical dilemma resurged when I conducted a series of online interviews with young people who self-injure (SEKO et al., 2015). Their stories of posting self-injury images online fascinated me, because they, through the active use of online media, resisted the dominant discourse that renders them "pathetic" or "vulnerable." But again, inside me, I felt a spectator longing for "insightful" and thus "publishable" data. Although the research received an ethical clearance from the institutional review board and I was equipped with a series of operating procedures to optimize participant safety, I was yet unsure if I was able to establish a respectful and ethical relationship with participants. As field notes and interview transcripts piled up, I started questioning whether I was to fetishize their suffering and serve up "pain stories on a silver platter for the settler colonial academy, which hungers so ravenously for them" (TUCK & YANG, 2014, p.812). [20]

As a result of the recurrent ethical conundrum pertinent to my research, I became particularly interested in arts-based research. Dance, theater, and other dynamic forms of performative arts appeared to be especially attractive ways of communicating my data. Performing data through an excessive, embodied method like dance also sparked my longing to bring the body back into my research, in a way that would fully address my emotional and somatic engagement with data and add intimate and subjective accounts hence absent from my previous publications (SEKO, 2013; SEKO & LEWIS, 2016; SEKO et al., 2015). Of course, this neither meant that I expected arts-based research to offer a panacea for the ethical dilemmas that faced me nor believed dance-based research to be fundamentally ethical. Rather, I was fascinated (and simultaneously frightened) by the idea of putting myself in the position of the observed, exposing my non-artist body to vulnerability, and unreservedly expressing my most intimate thoughts on self-injury. [21]

Gasping, with a hope that dance would potentially redress power imbalance associated with my research, I hesitantly nodded to Trish: "Yeah, sure, I could do that." [22]

3. Phase Two: Let the Dance Begin

3.1 Yukari: Excerpts from personal journal after the first dance workshop

The first "dance your data" workshop (held in Summer 2015) consisted of four weekly meetings. Trish, Janet, Melissa and I met at a bright, cozy dance studio run by Janet to embark on a journey to the unknown terrain. Uncertainty occupied our initial conversation, as it soon turned out each member brought disparate objectives to this project. Janet was excited about how our experimentation would eventually extend to involve youth who self-injure, while Melissa seemed open for any potential the project would entail. Trish, as the initiator of this project, had a broader objective to explore and produce an alternative way of knowing through arts-based methods against normative academic research. My objective to "dance my data" perhaps was the narrowest and the most ego-centric. I shared themes that had emerged from my past and present self-injury research, without knowing how these fragments would possibly transfer into a dance piece. [23]

Janet, a professional dancer and choreographer, then took the lead and gave us guidance about how to open up our bodies. We needed her to take leadership at this point, as the great obstacle now was to move away from the cerebral zone inhabited most comfortably via text and into an embodied space where our thoughts, knowledge and feelings would be expressed by bodily language. To let us be comfortable with our bodies and one another, Janet began each session with a short, ritualized gyrokinesis practice (a seated exercise composed of spiral movements) followed by a series of warm-up exercises. Through experiments with rhythm, gravity, walks and self-sculpture, we learned new ways of experiencing our bodies, corporeality and the self. As we went through warm-up exercises, my initial hesitancy was gradually replaced by curiosity and eagerness for self-exploration, and I felt more comfortable with myself and Trish, Janet and Melissa. Although we individually improvised movements and gestures, seeing and feeling my dance partners dancing beside me offered me a sense of comfort and belongingness. It was as if we were silently conversing with one another through bodily language, creating an intersubjective space to experiment and express ourselves. [24]

We picked up themes that had emerged from my research on self-injury (e.g., deep isolation, contesting desire for autonomy and attachment, stigma, fear, anxiety), improvised movements, and jotted down our thoughts in our individual journals. Through the cycle of imagining, improvising and journaling, we developed a series of short solo pieces and brought them together into one collaborative piece (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Collaborative improvization "The colors of self-injury" [25]

3.2 Trish: Self-reflection during collaborative writing

As Yukari noted, there was some uncertainty as we each encountered the various distinctions that have beleaguered many of the relationships that can occur in community-engaged participatory scholarship (BAUM, MacDOUGALL & SMITH, 2006). There were many distinctions within our research team: student-professor, research assistant/principal investigator, community member/ academic and artist/scientist. These were distinctions that stood silent but salient in the corners of the studio, breathing their claims to legitimacy into the sunny space. As women, we stood uncertainly, socialized to be relational and in tune to the needs of one another, yet unfamiliar with the complexity that was at play in that moment. [26]

Another distinction arose when we began to talk about self-injury. Yukari brought in a great deal of knowledge because of her in-depth research work, while I brought in knowledge as a clinician who had worked therapeutically with people who had self-injured. Janet and Melissa felt they did not have much knowledge at all about this issue. We spoke about stigma and about misconceptions, and we explored as a group some of the findings that had emerged from Yukari's research data. [27]

My own movements, as a mode of expression, have often stymied me. My knees and elbows are permanently scarred from the number of times I have fallen and scraped them. My hips carry the memory of table corners, banisters and doorframes I have collided into that left fleeting dark circles on tender skin. I am sure that my toes still retract each morning when I step out of bed, as they are certain to be stubbed by day's end. [28]

To turn to this body, a frame at the center of a series of uncoordinated spastic movements that miraculously move me through the tasks of everyday life, and remain open to its way of knowing seemed to be a risk of the highest order. I began to see the assumptions that were hidden within my trepidation and sense of risk. The assumptions emerged as voices in my head, imagined voices of colleagues whose tones are disdainful, patronizing and smug. They ask me "politely" how I will measure the robustness and validity of my dance-based research. They wondered how I would code this data and query about computer programs that might exist that could take a dance performance and access its codes and findings. These were laden with assumptions about what counts as reliable knowledge production. Of course, because the voices of my colleagues were in my head, these assumptions were my own. [29]

Autoethnography brought a consciousness, drawing these assumptions out so that their function could be re-assessed and re-searched. However, while I felt good about the revelations that had arrived, I was sobered by the question SPRY (2014) asks in her own autoethnographic work: "... is all of this theorizing, critiquing, and critically self-reflecting trumped by the fact that I can cut them off at any time and recede into the anonymity of an apoliticized white body?" (p.402). I must admit to myself that I stand to benefit from the many privileges I have been allotted, through the socialized markers of class, race, sexuality, language and ability. When the unsettling of power dynamics through my own immersion in alternative ways of knowledge becomes too uncomfortable, with too high a price, I can always go back to the safety I can access in the status quo. With privilege, that is my option. For me, this remains an unresolved consideration. [30]

While dance is a mode of knowledge expression that I have not intentionally engaged in before because of the risk I felt it to be, I recognize that unintentionally, for each individual, embodied knowledge is always being expressed. BOURDIEU (1990) described how we convey knowledge about our social identities continuously to one another through movement and posture. LEFEBVRE (1991) asserted that as we move through space, expressions of knowledge reproduce over and over again the exchanges, positionings, allowances and restrictions relevant to the space and our place in it. Qualitative researcher and dancer BARBOUR (2012) insists that embodied knowledge be recognized as a legitimate knowledge, even as it stands as an alternative epistemology to the knowledge that is traditionally accepted as valid in most Western post-secondary institutions. She writes: "Moving reveals the world and ourselves" (p.70). [31]

By interrogating the dominance of Western epistemology, we are also scrutinizing the social reproductions that BOURDIEU (1990) and LEFEBVRE (1991) refer to, as we question the social relations that determine valid knowledge and whose knowledge is deemed most legitimate (DU PLESSIS & ALICE, 1998). Arts-based research, including a dance-based approach, resists an allegiance to a positivist conception of knowledge insisting on only one way of knowledge that invades to take over alternative epistemologies (SPRY, 2014). Instead, arts-based approaches to research seek to find ways of knowledge production that are inclusive, participatory and community-based, drawing upon multiple ways of knowing. [32]

4. Phase Three: Knowing Through Dancing

4.1 Yukari: Excerpts from personal journal after the second dance workshop

A few months after the memorable summer, Trish invited Melissa and me to another opportunity to create a collaborative dance piece. On a cloudy afternoon of December 2015, we reunited at Janet's studio, our home for experimentation. This time we drew our inspiration from a poem written and donated to the project by Gabrielle VEGA, the moderator of a popular online community for people struggling with self-injury. I have been in touch with Gabrielle since 2012, when I sought her advice on how to ethically design and conduct the online interviews with people who post self-injury images online (SEKO et al., 2015). Through a series of bi-weekly online chat sessions, I gradually learned about Gabrielle, the poems she wrote, and how the online community has provided people struggling with self-injury a safe haven to be themselves. Gabrielle and I became co-researchers and collaborators, although we had never met in person. When the dance research continued, I was eager to have Gabrielle contribute in some way. To me, her poem "i could not read them" (Appendix) eloquently expressed the physical and psychological turmoil a person would experience with self-injury, which also closely resonated with many of the themes that emerged from my previous research. [33]

Prior to meeting in the dance studio, Trish, Melissa and I each chose a different section of the poem and individually devised dance movements. I decided to choreograph my favorite sentence featuring quickened heartbeats and swallowing charcoal (first 12 lines of the poem). Just as in previous qualitative studies, I began my process with repetitive readings of the passage assigned to me. But this time, instead of silently analyzing the text, I repeatedly read the lines out loud in different pitches, tempos and volumes to figure out the rhythm that would be best suited for my dance. As the entire poem was written in a first-person voice, I decided to use my own voice as mental guidance while contemplating how I would act it out. I then stood in front of a mirror with a copy of the passage and improvised several gestures and movements that literally physicalized the actions described in the poem, including beating my chest with interlaced fingers, swallowing pills and painting a wall with a piece of charcoal. Through repetitive experimentations and reflections, I deconstructed and reconstructed the movements to make them more abstract to express pain and despair behind the gestures (Figure 2).

Figure 2: Yukari "they flew and blurred and twisted like snakes" [34]

However, dancing Gabrielle's poem was quite different from quoting her words on a PowerPoint slide. During this creative process, I was unpleasantly surprised by how difficult it was to translate words into bodily language. My body deeply frustrated me; it turned out to be the most foreign medium I had ever used to convey a message. Apparently, I drew on culturally scripted, hegemonic perceptions of art as a professional enterprise (DAYKIN, 2008) and felt embarrassed about not being "good" at dancing like a pro. While intimidated by imagined spectators laughing at my poor performance, I nonetheless continued improvising movements with a hope to fully engage in the poem. [35]

Intriguingly, Melissa, despite her extensive experience in the world of art, expressed a very similar intimidation as she reflected on what it was like to view herself dancing:

"... the process felt so wonderful, and how I felt inside of the physical dancing was so satisfying. My imagination filled in the aesthetic value (which only really has value to myself), but seeing how the actual danced looked as incongruous to how the dance felt is what actually causes the greatest amount of unease" (ROOD, personal communication).

***

But do we have to dance like a pro to know differently?*** [36]

Looking back, what I was aiming to create was perhaps not dance—if you call dance a form of art performed exclusively by trained artists. My exploration was rather a muddy, experimental effort to improvise interpretative movements to express my engagement with the poem, previous dialogue with Gabrielle, and silent, bodily conversations with my dance partners/co-researchers. This embodied experience helped me realize my own vulnerability and limitation as a researcher, as well as the unprecedented possibility of utilizing my body as a means of not only knowledge dissemination but also engaged knowledge production. I developed what CANCIENNE and BAGLEY call "a physicality of knowing" (2008, p.176), a way of thinking improvisationally to construct a deep connection to the poem and Gabrielle's experiences. By paying attention to bodily reactions to emotional experiences, I came in agreement with YLÖNEN (2003) who expresses the physical and emotive excitement during her dance because "doors opened for me as a researcher to such bodily knowledge that cannot always be described in words" (p.554). In other words, the dance added a sensual, haptic quality to my understanding of Gabrielle's experience. [37]

4.2 Trish: Excerpts from individual journal after the second dance workshop

I bring into the dance a clinical knowledge about how ritualistic self-injury can be, about longing and the crushing solitude that can motivate self-injury, and about the sense of not belonging that can inspire self-injury but can also create the important solace that is found in an online community about self-injury. I was not aware that I had brought this knowledge into the dance until after I had made some decisions about movements. I know that I want only a few movements, but I want them to represent a ritual marked by repetitive, symbolic movement. With one arm, I create the mouth of a basket. I reach into the basket with my other arm. Then, my hands join, fingers fluttering to become wings that fly up into the sky until one hand covers the other and forces it down. I turn that hand into a straight blade and bring it down across the soft flesh of my inner arm, jerking up onto my toes at the same time. My scarred arm drops and then rises to form the mouth of a basket once more, with the other hand reaching in, joining hands and, again, with fluttering fingers, rises up in the air like a bird. Three times this happens as I turn until I have completed a circle. I bend my arms at the elbow and raise them up so that they are level with my face. My arms rotate so that the hands hover one on top of the other, without touching. I lower my arms and pull them apart in front of my face, closely examining the inside arm where the slicing gesture occurred in the first sequence. I bring a flow to my movements, with hands turning, hovering and then pulling apart. I want to know what is written in the flesh of my inner arms, but there is also a floating suspension where my hands and arms move close to one another without actually touching. I repeat this flow three times, and then my hands lock onto my elbows move them up so that they frame my face and I can no longer peer at my inner arms. My hands unclasp my elbows, which come together and come down slowly, passing over my face. Below my chin the movement stops, and then I rise my hands up with arms and elbows touching. I look up at my hands with their fingers spread wide. I move into a stable standing position, feet hip width. There is a sense of rootedness moving up through my body into my widespread fingers. This is how I stand to express a quiet freedom of not needing to know "the message that is contained within the scar script" on my arms (SEKO & VAN KATWYK, 2016) (Figure 3).

Figure 3: Trish "i would have not woken up" [38]

5.1 Trish: Self-reflection during collaborative writing

While writing this article, I was invited to present to an undergraduate class of students about some of the other research I am conducting. I spoke about the importance of context, which includes a consideration of the ways in which spaces are organized according to a particular set of ruling relations. The professor of the course closed the presentation with a gentle reminder to the class that histories profoundly shape our geographies so as to make it impossible to talk about current practice without a deep acknowledgment of the ruptures left behind by histories, or, more specifically, by the protagonists of history. These are the ruling voices that drove (drive) the events that forge bodily, spiritual, psychic and social injury (OUDSHOORN, 2015). I left the presentation reflecting about how the events of history are propelled by the truths and knowledge of the time. Our current truth and knowledge recedes into another history that, like all histories, leaves everlasting inscriptions in the future. This is the potential of knowledge, because of its immersion in the exercise of power. The harm that can be created by the ways in which knowledge gets enacted comes into contact first with those on the front line, the instruments of the powerful. [39]

During our collaborative self-exploration, we realized our deep immersion in a particular way of knowing, with an internalized disciplinary gaze, and thus have felt a sense of trepidation about "pushing the envelope." We have faced risk as we question the objectivity and generalizability of "good science." Our struggle mirrors what Katherine BOYDELL and her colleagues (2016) documented regarding the tensions experienced by arts-based health researchers with respect to academic legitimacy. With autoethnography, we have centered our subjective experiences. In the role of researcher-participant, we have practiced vulnerability in our resistance to research methods that would objectify others. Collectively, we have utilized one another's perspectives in our efforts to pull apart and articulate the assumptions that sustain the primacy of positivist science. Through this process, it has become clear to us that knowledge closely reflects and reproduces existing power structures, and thus deeply connects to a social justice issue, with concerns about the ways in which human rights are inequitably distributed based on the practices of knowledge. Social justice is closely tied to human rights, as the Universal Declaration of Human Rights was developed following World War II in response to the human rights atrocities committed during that war. The universal declaration states that every human being is entitled to human rights. However, although entitled, not every human being is able to exercise their human rights. Social justice occurs when the ability to exercise one's human rights is equitably distributed across humanity. The social justice lens, then, is the ongoing, close consideration of equity in order for the entitlement of human rights to be experienced by everyone (ASHCROFT & VAN KATWYK, 2016). Our social justice platform considers the ways in which collaborative autoethnography and arts-based research methods create opportunities for more just research relations by shifting the ways we validate knowledge and form relationships in research, raising new ethical possibilities. [40]

The dialogue and discoveries that we have enjoyed (the "unique gift" that is presented with collaborative writing) have allowed us numerous considerations. We prodded one another to dig deeper, and to reach further into a critical perspective. It is time now to consider the trail that this collaboration has followed. We tell each other to resist the temptation of a linear and orderly presentation while, at the same time, holding you, the reader, in our consciousness.

***

How can our collaboration also strive for a live, engaged connection with you? What is it that we offer to you, the reader?*** [41]

We offer this: a collaborative autoethnography that has been an exploration of our place in a web of relations that sustain the sovereignty of positivist notions about knowledge. Using critical reflexivity and the lived experience of researcher-participant, we have explored arts-based research as an attempt to understand the life experiences of others. With arts-based approaches, the objectives and practices of knowledge remain open to the depth and significance of subjective experience, becoming holistic so that a more inclusive encounter with the other is possible. It is in this way that knowledge—its validation, its expression, acquisition and the objectives of its practices—is intricately bound to considerations of social justice. We have asked: How do our practices of knowledge commodify (and dehumanize) the lives of an individual or community? How does making dominant one way of knowledge erase cultures, spiritualities and lives? How does such an erasure sanction exploitation and/or deprivation? [42]

5.2 Yukari: Self-reflection during collaborative writing

Among the many "gifts" our dance projects entailed, I found most serendipitous the embodied vulnerability brought to the fore through mutual witnessing of each other's dancing bodies and writing. While witnessing Trish dancing beside me and then witnessing her autoethnography unfolding over time on/off-line, I felt as though I was stepping into her personal embodied space. In return, with a trepidation and curiosity, I invited her to my territory, pulling up the curtain to the formerly concealed backstage of my academic life. Through the dance and this collaborative writing, we gradually immersed ourselves into inter-subjective meaning-making, let each other's voices overlap, echo, harmonize and dissonate, and eventually embraced our own vulnerability as an agent of knowledge co-construction. As we deeply engaged in this "relational praxis" (PENSONEAU-CONWAY et al., 2014, p.312), the membrane between us became thin, to the extent I am no longer able to claim authenticity over "my" individual contribution to this article. Rather, the knowledge this article intends to offer is inseparable from our newly constructed, unfinished and constantly changing relationship. Writing about myself is, in the end, writing about the self with others. [43]

For me, this realization is in strong alignment with KAUFFMAN's (1993) critique of commodified personal testimonies that perpetuate individualism, the ideology that depicts the individual as "removed from history, economics, and even from the unconscious ... as someone who always has choices, and whose choices are always 'free'" (p.269). The belief that anyone can reveal her/his "true" unique self through solitary self-expression is, as KAUFFMAN argues, a delusion that bears the danger of disguising systematic inequalities as individual malaise. As our autoethnography revealed, individual experience is always situated in social, cultural and material relations, and thus can best be defined through inter-subjective processes within which it unfolds. As such, I highly valued my relinquishing of analytical and representational control over my data and appreciated a level of comfort that I felt while using the "we" voice in this article. If our task as critical academics is "continually to cast doubt on the status of knowledge—even as we are in the process of constructing it" (p.274), writing together to go beyond perpetual individualism can be the first small, but convincing step toward social justice.

•••

Yet, I still hear SPRY's (2014) voice in my head: "Am I just trying to make myself feel better?" (p.401) Did I dance to justify

my exploitation of the experiences of Gabrielle and other people suffering self-injury?*** [44]

After the Winter project, I hesitantly sent the video clip of our second dance piece to Gabrielle, the poet. After a while, she wrote me back:

"How inspiring to see [the dance] live! I feel you're the one who got closest to the heart of what I felt when writing that poem, when thinking back on that moment in my life. That impulse towards self-annihilation is no longer the driving force of my life and part of that has been thanks to the inspiring people I've met because of my experiences (both online and offline)" (G. VEGA, personal communication). [45]

Although her compliment does not justify my researcher privilege of writing about others, I will carry her words like a talisman to continually question, demystify and reconceptualize the construction of knowledge. Let the dance go on. [46]

Sincere thanks go to Janet JOHNSON and Melissa ROOD, our co-researchers and dance partners, who made this project possible. We are also grateful to Gabrielle VEGA for donating her poem to the dance project. We gratefully acknowledge the support we received from the Renison University College Professional Development Grant as well as the Renison University College Internal Research Fund. Finally, we want to thank Calhoun BREIT for his photography and film work.

Appendix: "i could not read them" by Gabrielle VEGA (2007)

when i was seventeen

my heart beat so fast

onetwofiveten beats like that.

swallowing charcoal down

like water, the grit getting

in between my teeth

and on my fingers. i wanted

to paint the room with

charcoal but, oh god, the letters

on the sign were moving.

they flew and blurred and twisted

like snakes.

there were hands on my clothes,

it was too hot. water would do,

please. just give me water.

my breasts, an ugly word etched

on them, felt the cool air.

hands tugging my shirt

down. the stickiness of monitors

being attached. my mother

was a blur at my side, she had

no eyes. only a mouth that opened

like a cavern edged with teeth.

my hands shook, my body shook,

everything was coming down and

there was that salty dirty taste

in my mouth. i had vomited until

i fell on hands and knees. like a drunk

in the gutter i vomited until i was

weak and trembling and my mind

had gone off to keep another girl

company. one who didn't do things

like this.

i watched them put a needle

through my wrist, eyes crossing,

mouth working to try to talk. to

say something. please, don't go away.

there was no pain. blood gas.

they talked, a distant murmur.

please, honey, swallow that charcoal.

my mouth was open. i could not close

it and there was thick drool on my chin.

it was dying in reverse. outside there

must have been the sun and girls

laughing so that their teeth showed.

inside i sweated and i could not think.

i couldn't think. what were they saying?

speak english, please. speak something

i can't understand because the words

are flying and the shape of a u is like

an x with a broken limb.

i lay there stupid and shaking, half naked.

time had gone to sleep and, oh god,

there were scars on my arms that

twisted into words i could not read.

i was sure if i could read them i

would have not woken up.

Andrews, Elizabeth (2009). Arts-based research: An overview. Weblog post, November 8, http://www.personal.psu.edu/eja149/blogs/elizandrews/2009/11/arts-based-research-an-overview.html [Accessed: March 25, 2016].

Ashcroft, Rachelle & Van Katwyk, Trish (2016). An examination of the biomedical paradigm: A view of social work. Social Work in Public Health, 31(3),140-152.

Augustine, Sharon Murphy (2014). Living in a post-coding world analysis as assemblage. Qualitative Inquiry, 20(6), 747-753.

Barbour, Karen Nicole (2012). Standing center: Autoethnographic writing and solo dance performance. Cultural Studies <-> Critical Methodologies, 12(1), 67-71.

Barone, Tom & Eisner, Elliot W (Eds.) (2012). Art-based research. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Battiste, Marie (2002). Indigenous knowledge and pedagogy in First Nations education: A literature review with recommendations. Ottawa: Apamuwek Institute, http://www.afn.ca/uploads/files/education/24._2002_oct_marie_battiste_indigenousknowledgeandpedagogy_lit_review_for_min_working_group.pdf [Accessed: March 3, 2016].

Bauder, Herald & Engel-Di Mauro, Salvatore (Eds.) (2008). Critical geographies: A collection of readings. Kelowna: Praxis ePress, http://www.praxis-epress.org/CGR/CG_Whole.pdf [Accessed: March 5, 2016].

Baum, Fran; MacDougall, Colin & Smith, Danielle (2006). Participatory action research. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health, 60(10), 854-857.

Bhattacharyya, Gargi (2013). How can we live with ourselves? Universities and the attempt to reconcile learning and doing. Ethnic and Racial Studies, 36(9), 1411-1428.

Blodgett, Amy T.; Coholic, Diana A.; Schinke, Robert J.; McGannon, Kerry R.; Peltier, Duke & Pheasant, Chris (2013). Moving beyond words: Exploring the use of an arts-based method in Aboriginal community sport research. Qualitative Research in Sport, Exercise and Health, 5(3), 312-331.

Blumenfeld-Jones, Donald S. (1995). Dance as a mode of research representation. Qualitative Inquiry, 1(4), 391-401.

Boydell, Katherine M. (2011). Making sense of collective events: The co-creation of a research-based dance. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung / Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 12(1), Art. 5, http://nbn-resolving.de/urn:nbn:de:0114-fqs110155 [Accessed: September 26, 2016].

Boydell, Katherine M.; Gladstone, Brenda M; Volpe, Tiziana; Allemang, Brooke & Stasiulis, Elaine (2012). The production and dissemination of knowledge: A scoping review of arts-based health research. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung / Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 13(1), Art. 32, http://nbn-resolving.de/urn:nbn:de:0114-fqs1201327 [Accessed: March 26, 2016].

Boydell, Katherine M.; Hodgins, Michael; Gladstone, Brenda M.; Stasiulis, Elaine; Belliveau, George; Cheu, Hoi; Kontos & Parsons, Janet (2016). Arts-based health research and academic legitimacy: transcending hegemonic conventions. Qualitative Research, 16(6), 681-700.

Bourdieu, Pierre (1990). The logic of practice (transl. by R. Nice). Cambridge: Polity Press.

Brickell, Katherine & Garrett, Bradley (2015). Storytelling domestic violence: Feminist politics of participatory video in Cambodia. ACME: An International E-Journal for Critical Geographies, 14(3), 928-953.

Bridges-Rhoads, Sarah (2015). Writing paralysis in (post) qualitative research. Qualitative Inquiry, 21(8), 704-710.

Cancienne, Mary Beth & Bagley, Carl (2008). Dance as method: The process and product of movement in educational research. In Pranee Liamputtong & Jean Rumbold (Eds.), Knowing differently: Arts-based and collaborative research methods (pp.169-186). New York: Nova Science Publishers.

Chang, Heewon; Ngunjiri, Faith Wambura & Hernandez, Kathy-Ann C. (2012). Collaborative autoethnography (Vol. 8). Walnut Creek, CA: Left Coast Press.

Custer, Dwayne (2014). Autoethnography as a transformative research method. The Qualitative Report, 19(37), 1-13, http://nsuworks.nova.edu/tqr/vol19/iss37/3 [Accessed: January 18, 2017].

Cutforth, Nick (2013). The journey of a community engaged scholar: An autoethnography. Quest, 65(1), 14-30.

Daykin, Norma (2008). Knowing through music: Implications for research. In Pranee Liamputtong & Jean Rumbold (Eds.), Knowing differently: Arts-based and collaborative research methods (pp.229-243). New York: Nova Science Publishers.

Denzin, Norman K. & Lincoln, Yvonna S. (Eds.) (2011).The Sage handbook of qualitative research (4th ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Denzin, Norman K.; Lincoln, Yvonna S. & Giardina, Michael D. (2006). Disciplining qualitative research. International Journal of Qualitative Studies in Education, 19(6), 769-782.

Du Plessis, Rosemary & Alice, Lynne (1998). Feminist thought in Aotearoa/New Zealand differences and connections. Auckland: Oxford University Press.

Ellis, Carolyn (2004). The ethnographic I: A methodological novel about autoethnography. Walnut Creek, CA: AltaMira Press.

Ellis, Carolyn; Adams, Tony E. & Bochner, Arthur P. (2011). Autoethnography: An overview. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung / Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 12(1), Art. 10, http://nbn-resolving.de/urn:nbn:de:0114-fqs1101108 [Accessed: January 24, 2017].

Foucault, Michel (1980). Power/knowledge: Selected interviews and other writings, 1972-1977. New York: Pantheon.

Gale, Ken; Pelias, Ron; Russell, Larry; Spry, Tami & Wyatt, Jonathan (2013). Intensity: A collaborative autoethnography. International Review of Qualitative Research, 6(1), 165-180.

Garbati, Jordana F. & Rothschild, Nathalie (2016). Lasting impact of study abroad experience: A collaborative autoethnography. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung / Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 17(2), Art. 23, http://nbn-resolving.de/urn:nbn:de:0114-fqs1602238 [Accessed: January 24, 2017].

Gergen, Mary M. & Gergen, Kenneth J. (2010). Performative social science and psychology. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung / Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 12(1), Art. 11, http://nbn-resolving.de/urn:nbn:de:0114-fqs1101119 [Accessed: January 24, 2017].

Guiney Yallop, John J.; Lopez de Vallejo, Irene & Wright, Peter R. (2008). Editorial: Overview of the performative social science special issuer. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung / Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 9(2), Art. 64, http://nbn-resolving.de/urn:nbn:de:0114-fqs0802649 [Accessed: January 24, 2017].

Holbrook, Teri & Pourchier, Nicole M. (2014). Collage as analysis remixing in the crisis of doubt. Qualitative Inquiry, 20(6), 754-763.

Jones, Kip & Leavy, Patricia. (2014). A conversation between Kip Jones and Patricia Leavy: Arts-based research, Performative social science and working on the margins. The Qualitative Report, 19(19), 1-7, http://nsuworks.nova.edu/tqr/vol19/iss19/2 [Accessed: January 24, 2017].

Kauffman, Linda S. (1993). The long goodbye: Against personal testimony, or an infant grifter grows up. In Linda S. Kaufman (Ed.), American feminist thought at century's end: A reader (pp.258-277). Cambridge, MA: Blackwell.

Lefebvre, Henri (1991). The production of space. London: Blackwell.

Manovski, Miroslav Pavle (2014). Arts-based research, autoethnography, and music education, singing through a culture of marginalization. Rotterdam: Sense Publishers.

Martinez, Shantel (2013). "For our words usually land on deaf ears until we scream": Writing as a liberatory practice. Qualitative Inquiry, 20(1), 3-14.

Oudshoorn, Judah (2015). Trauma-informed rehabilitation and restorative justice. In Theo Gavrielides (Ed.), The psychology of restorative justice: Managing the power within (pp.159-182). Surrey: Ashgate.

Pearce, Kelly & Coholic, Diana. (2013). A photovoice exploration of the lived experiences of a small group of Aboriginal adolescent girls living away from their home communities. Pimatisiwin: A Journal of Aboriginal & Indigenous Community Health, 11(1), 113-124.

Pensoneau-Conway, Sandra L.; Bolen, Derek M.; Toyosaki, Satoshi; Rudick, Kyle C. & Bolen, Erin K. (2014). Self, relationship, positionality, and politics a community autoethnographic inquiry into collaborative writing. Cultural Studies <-> Critical Methodologies, 14(4), 312-323.

Seko, Yukari (2013). Picturesque wounds: A multimodal analysis of self-injury photographs on Flickr. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung / Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 14(2), Art. 22, http://nbn-resolving.de/urn:nbn:de:0114-fqs1302229 [Accessed: January 20, 2017].

Seko, Yukari & Lewis, Stephen P. (2016). The self—harmed, visualized, and reblogged: Remaking of self-injury narratives on Tumblr. New Media & Society, advanced online publication. doi: 10.1177/1461444816660783

Seko, Yukari & Van Katwyk, Trish (2016). Embodied interpretation: Assessing the knowledge produced through a dance-based inquiry. Aotearoa New Zealand Social Work, 28(4), 54-66.

Seko, Yukari; Kidd, Sean A.; Wiljer, David & McKenzie, Kwame J. (2015). On the creative edge: Exploring motivations for creating non-suicidal self-injury content online. Qualitative Health Research, 25(10), 1334-1346.

Sontag, Susan (2003). Regarding the pain of others. New York: Picador/Farrar, Straus and Giroux.

Spry, Tami (2014). By the roots: A postscript to Goldilocks. Text and Performance Quarterly, 34(4), 399-403.

St. Pierre, Elizabeth A. & Jackson, Alecia Y. (2014). Qualitative data analysis after coding. Qualitative Inquiry, 20(6), 715-719.

Strong, Marilee (1998). A bright red scream: Self-mutilation and the language of pain. New York: Penguin.

Toyosaki, Satoshi; Pensoneau-Conway, Sandra L.; Wendt, Nathan A & Weathers, Kyle (2009). Community autoethnography: Compiling the personal and resituating whiteness. Cultural Studies <-> Critical Methodologies, 9(1), 56-83.

Tuck, Eve & Yang, K. Wayne (2014). Unbecoming claims pedagogies of refusal in qualitative research. Qualitative Inquiry, 20(6), 811-818.

Wang, Catherine & Burris, Mary Ann (1997). Photovoice: Concept, methodology, and use for participatory needs assessment. Health Education & Behavior, 24(3), 369-387.

White, Vice & Belliveau, George. (2011). Multiple perspectives, loyalties and identities: exploring intrapersonal spaces through research‐based theatre. International Journal of Qualitative Studies in Education, 24(2), 227-238.

Ylönen, Maarit E. (2003). Bodily flashes of dancing women: Dance as a method of inquiry. Qualitative Inquiry, 9(4), 554-568.

Dr. Trish VAN KATWYK is an assistant professor and researcher trained in social work, She is committed to social justice, and focuses on redressing the inequities created by the omission or disregard of worldviews and knowledges that lay outside of a Euro-Western ontology that would rupture the connections between being and doing in the surrounding environment. The being and doing that Trish brings to her research are collaborative and participatory. Research methods have included canoeing, dancing, cartooning, and sculpting.

Contact:

Dr. Trish Van Katwyk

School of Social Work

Renison University College, University of Waterloo

240 Westmount Road North, Waterloo, ON, N2L3G4, Canada

E-mail: pvankatwyk@uwaterloo.ca

Dr. Yukari SEKO is a research associate at the Holland Bloorview Kids Rehabilitation Hospital in Toronto, Canada. Trained as a critical Internet scholar with acute interest in mental health, health promotion, and social determinants of health, she aspires a career spanning communication and culture studies and health research. Her research interests include visual narratives of pain, arts-based methodology, digital health promotion, and mental health and well-being of youth transitioning into adulthood.

Contact:

Dr. Yukari Seko

Bloorview Research Institute

Holland Bloorview Kids Rehabilitation Hospital

150 Kilgour Rd. Toronto, ON, M4G1R8, Canada

E-mail: yukari.seko@gmail.com

Van Katwyk, Trish & Seko, Yukari (2017). Knowing Through Improvisational Dance: A Collaborative Autoethnography [46 paragraphs].

Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung / Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 18(2), Art. 1,

http://nbn-resolving.de/urn:nbn:de:0114-fqs170216.