Volume 18, No. 2, Art. 11 – May 2017

Participatory Assessment of a Matched Savings Program for Human Trafficking Survivors and their Family Members in the Philippines

Laura Cordisco Tsai, Ivy Flor Seballos-Llena & Rabia Ann Castellano-Datta

Abstract: Survivors of human trafficking often experience considerable financial difficulties upon exiting human trafficking, including pressure to provide financially for their families, challenges securing employment, lack of savings, and familial debt. Few evaluations have been conducted of reintegration support interventions addressing financial vulnerability among trafficking survivors. In this article, we present findings from a participatory assessment of the BARUG program, a matched savings and financial capability program for survivors of human trafficking and their family members in the Philippines. Photovoice was used to understand the experiences of two cohorts of BARUG participants. Survivors collaborated with research team members in conducting thematic analysis of transcripts from the photovoice sessions. Themes included: the positive emotional impact of financial wellness, overcoming the challenges of saving, applying financial management skills in daily decision making, developing a habit of savings, building a future-oriented mindset, receiving guidance and enlightenment, the learning process, and the change process. Findings reinforce the importance of interventions to support trafficked persons and their family members in getting out of debt and accumulating emergency savings, while also providing emotional support to survivors in coping with family financial pressures. The study also highlights the value of using participatory research methods to understand the experiences of trafficked persons.

Key words: photovoice; participatory research methods; human trafficking; saving; financial capability; individual development accounts

Table of Contents

1. Introduction

1.1 Overview of BARUG

1.2 Evaluation of BARUG using photovoice

2. Methods

2.1 Study participants

2.2 Photovoice process

3. Findings

3.1 Cohort A themes

3.2 Cohort B themes

4. Discussion

5. Limitations

6. Conclusion

The Philippines is a source country for human trafficking, and to a lesser degree, a transit and destination country. Men, women, and children in the Philippines are trafficked for work in a wide range of industries, including domestic work, sex work, online sexual exploitation, fishing, agriculture, construction, and hospitality-related jobs, among others (U.S. DEPARTMENT OF STATE, 2016). Adults and children are trafficked internally within the Philippines from rural areas to major metropolitan centers, such as Metro Manila and Cebu, and key tourist destinations, such as Boracay and Surigao. People are also trafficked from the Philippines throughout the Middle East, Asia and North America, with destinations including Malaysia, Japan, Hong Kong, Saudi Arabia, Kuwait, the United Arab Emirates, and the United States (ECPAT INTERNATIONAL, 2016; U.S. DEPARTMENT OF STATE, 2016). [1]

Poverty and financial vulnerability are common risk factors for human trafficking (BALES, 2011; SIMKHADA, 2008). When survivors exit human trafficking, the same factors that initially made them vulnerable to human trafficking are often still present; most relevant to the present study, these factors include lack of employment, debt, and the lack of a safety net in times of financial crisis (JOBE, 2010; LE, 2016). Many trafficking survivors face substantial financial difficulties when re-entering the community after being trafficked, including a lack of access to safe employment, lack of savings, responsibility to repay familial debts, and financial anxiety (BRUNOVSKIS & SURTEES, 2012a; JOBE, 2010; LE, 2016; LISBORG, 2009; RICHARDSON, POUDEL & LAURIE, 2009; SMITH-BRAKE, LIM & NHANH, 2015; TSAI, 2017a, 2017b). Financial stability is often a key priority for survivors themselves upon community re-entry. For instance, in one study with Filipina and Thai trafficking survivors, participants noted that financial difficulties were their primary concern upon re-entry. Some participants expressed that their financial challenges were more burdensome than other trauma they had experienced in their trafficking history and that their greatest concern was returning home having "failed" economically (LISBORG, 2009, p.4). Pressures to provide financially for the family upon community re-entry can strain family relationships, hinder the community reintegration process, and ultimately lead survivors to pursue risky employment opportunities (BRUNOVSKIS & SURTEES, 2012b; JOBE, 2010; SIMKHADA, 2008; SMITH-BRAKE et al., 2015; SURTEES, 2013; TSAI, 2017a). [2]

In the Filipino context, the family is commonly seen as the basic unit of society (ASIS, HUANG & YEOH, 2004; GALAM, 2015; MEDINA, 2001) and "the source of almost everything in life" (JOCANO, 1998, p.155). During difficult circumstances, family members are often expected to provide for one another financially; neglecting this responsibility can lead to familial discord and a loss of respect within the family (GALAM, 2015; JOCANO, 1998; MEDINA, 2001). Trafficking survivors in the Philippines are embedded within family systems that significantly shape their material and emotional well-being and the stability of the reintegration process (TSAI, 2017a). Further attention should be given to reintegration support interventions for survivors that alleviate financial pressures faced within survivors' familial networks, as well as interventions that help survivors cope with financial pressures experienced during the community re-entry process (BRUNOVSKIS & SURTEES, 2012a, 2012b; TSAI, 2017a). [3]

Evidence-based models for promoting economic security for trafficked persons are, however, limited. Although vocational training programs are widespread, many such programs do not connect survivors to sustainable employment opportunities upon completion and/or focus on skills that are not marketable or of interest to survivors (RICHARDSON et al., 2009; SURTEES, 2012). In the Philippines, several organizations have begun in recent years to provide employment-related assistance to trafficked persons upon community re-entry. For instance, in the nonprofit sector in Cebu, the following services are available specifically for trafficking survivors: career counseling, job readiness training, educational scholarships, tutoring, and job referral services. Additionally, a handful of social enterprise businesses have been created in Cebu to provide employment to survivors of human trafficking in the business process outsourcing, handicrafts, and food services industries. However, these social enterprises are small in scale and vary in their level of sustainability. At present, none of these organizations incorporate financial counseling or asset development into their interventions. Even if survivors are able to secure employment, lack of access to safe places to save money, personal and familial debts, recurring familial financial pressures, and the multiple layers of vulnerability faced by survivors upon re-entry means that survivors often remain vulnerable to financial crises and the associated consequences upon reintegration. In this article we present findings from a participatory assessment of the BARUG program, a matched savings and financial capability program for trafficking survivors and their family members in the Philippines. [4]

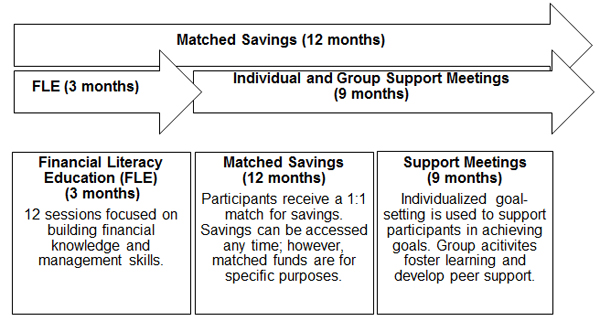

BARUG is a financial literacy and matched savings intervention designed, implemented, and funded by Eleison Foundation1) that aims to support the financial stability of trafficked persons in the Philippines. BARUG means "to stand up" in Cebuano, signifying that the program endeavors to support the economic self-sufficiency of participants. BARUG strives to build the capacity of survivors to cope with financial shocks, promote financial security, and support healthy family engagement around finances. Given the importance of familial support in the reintegration process and the connection between family financial stability and successful reintegration, survivors have the option to invite a family member to join the intervention with them (BRUNOVSKIS & SURTEES, 2012a, 2012b; SMITH-BRAKE et al., 2015). However, if survivors cannot identify a supportive family member who is interested in the program, they can join independently. The intervention uses a three-pronged approach: financial literacy education, matched savings, and support group meetings, as shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1: Structure of BARUG intervention [5]

The first stage of the intervention consists of a financial literacy education (FLE) course. The curriculum contains 12 sessions delivered once per week for two hours at a time covering savings, bank services, budgeting, debt management, and personal financial negotiation based upon an adapted version of MICROFINANCE OPPORTUNITIES' (2002) "Global Financial Education Program." Consistent with social cognitive theory (BANDURA, 1986, 1997), individualized goal-setting is integrated throughout the FLE curriculum. Participants set long-term and short-term financial goals and develop individualized plans to achieve their goals. The integration of goal setting into financial education has been proven to positively impact savings behavior (FRY, MIHAJILO, RUSSELL & BROOKS, 2008). [6]

The second component of the intervention is a matched savings program, an evidence-based asset development intervention that commences simultaneous to the FLE course (SHERRADEN, 1991). The matched savings component is informed by asset theory, which posits that assets improve household stability by cushioning income shocks and creating an orientation toward the future. In asset theory, the accumulation of assets results not only in improved financial well-being, but also generates psychological, social, and behavioral benefits (SHERRADEN, 1990, 1991). Institutional access to asset building mechanisms is, however, needed in order to build assets. Since low-income households do not have the same institutional opportunities as higher-income households, it is more difficult for low-income households to accumulate assets (CURLEY, SSEWAMALA & SHERRADEN, 2009; SHERRADEN, 1991). BARUG strives to address institutional gaps, providing participants the opportunity to open a savings account at a pre-screened bank partner or to make use of a savings deposit collection service provided by the program. For each peso that participants save during the program, their savings are matched at a 1:1 ratio, up to a match cap of 1,000 pesos savings per month (totaling a maximum of 12,000 pesos in matched savings in the one-year program). The matched savings process aims to incentivize participants to save and foster a regular habit of saving (SHERRADEN, WILLIAMS, McBRIDE & SSEWAMALA, 2004). Savings can be used for any purpose and withdrawn at any time. The matched funds can, however, only be used for specific purposes, including education, job training, medical expenses, business development, and family emergencies. [7]

Upon completion of the FLE course, monthly support meetings are held for 9 months. Each month, participants meet with a staff member (either individually or with a family member co-participant) to review their long-term and short-term goals, discuss progress toward achieving goals, celebrate successes, and brainstorm solutions to challenges. Additionally, monthly group meetings are held to give participants the opportunity to share about their respective successes and challenges in achieving their goals. Participatory group activities are conducted at these sessions to reinforce learning and build peer support networks, consistent with social cognitive theory (BANDURA, 1986, 1997). [8]

1.2 Evaluation of BARUG using photovoice

Photovoice is a community-based participatory research (CBPR) method grounded in empowerment education (FREIRE, 1970), feminist theory (WANG, BURRIS & PING, 1996), and documentary photography (WANG & BURRIS, 1994). Community members take photographs to share about their experiences, providing the opportunity to discuss the reality of their lives and recount their experiences in their own voices (FOSTER-FISHMAN, NOWELL, DEACON, NIEVAR & McCANN, 2005; MOLLOY, 2007; SUTTON-BROWN, 2014). Photovoice aims to identify community strengths and concerns, promote dialogue about shared experiences through collective discussions of photographs, and lead to social action (WANG, 1999). Since its initial application with Chinese women in Yunnan province (WANG & BURRIS, 1997), photovoice has been employed to address an array of social issues, including homelessness among women (BUKOWSKI & BUETOW, 2011), refugee migration (GURUGE et al., 2015), health care interventions for people with mental illness (CABASSA et al., 2012), mobility issues among people with disabilities (BISHOP, ROBILLARD & MOXLEY, 2013), and women's experiences of empowerment and disempowerment in microfinance (SUTTON-BROWN, 2011). [9]

In the current study, we used photovoice to understand the experiences of trafficking survivors and their family members participating in BARUG. A secondary goal of the study was to test the feasibility of using photovoice with trafficked persons. Consistent with the principles of participatory research, we recognized the importance of engaging BARUG participants as active stakeholders in the research process, rather than just the "subjects" of research (CARGO & MERCER, 2008; MARCU, 2016; MINKLER, 2004). Prior research has shown that participation in photovoice can build confidence, empowerment in being recognized as an expert, and a sense of ownership over one's own experiences (FOSTER-FISHMAN et al., 2005; JORGENSON & SULLIVAN, 2010; VAUGHN, FORBES & HOWELL, 2009). We aimed to collect data that could enhance programmatic effectiveness while building ownership over the project and empowering survivors in the process (CASTLEDEN, GARVIN & HUU-AY-AHT FIRST NATION, 2008; MIYOSHI & STENNING, 2008; PALMER et al., 2009). [10]

Participatory methodologies may be particularly fitting for research with trafficked persons. Trafficking survivors often experience a breakdown of trust through the deception involved in the trafficking process (YEA, 2016). Trust building and respect for survivors' autonomy and voices are essential to conducting research with trafficked persons that is sensitive to their prior experiences (EASTON & MATTHEWS, 2016; KELLY & COY, 2016; TSAI, 2017c). The current study makes a contribution to the literature, as it is, to our knowledge, the first study that has used photovoice with trafficked persons. First, we describe the methods employed during this photovoice project. Next, the findings of the photovoice project are presented, including themes identified by participating trafficking survivors themselves. We conclude with a discussion of the implications of this project for reintegration support and economic empowerment programming for survivors of human trafficking. [11]

From May 2015 until April 2016, we implemented BARUG with two cohorts of trafficking survivors and their family members in Cebu, Philippines. The cohorts were recruited from two organizations providing employment-related services to survivors of trafficking and abuse, including one non-governmental organization (NGO) and one social enterprise business. BARUG was implemented simultaneously but separately in each cohort. Purposive sampling was utilized to recruit participants (ABRAMS, 2010; ROBINSON, 2014). Each survivor who chose to participate in BARUG had the opportunity to bring one family member to join the program. The referring agencies assessed whether participants could be classified as "victims of trafficking" according to the Filipino Expanded Anti-Trafficking in Persons Act of 2012 (REPUBLIC ACT NUMBER 10364, 2012). As per this legislation, human trafficking is defined as:

"... the recruitment, transportation, transfer or harboring, or receipt of persons with or without the victim's consent or knowledge, within or across national borders by means of threat or use of force, or other forms of coercion, abduction, fraud, deception, abuse of power or of position, taking advantage of the vulnerability of the person, or, the giving or receiving of payments or benefits to achieve the consent of a person having control over another person for the purpose of exploitation which includes at minimum, the exploitation or the prostitution of others or other forms of sexual exploitation, forced labor or services, slavery, servitude or the removal or sale of organs. The recruitment, transportation, transfer, harboring, adoption or receipt of a child for the purpose of exploitation or when the adoption is induced by any form of consideration for exploitative purposes shall also be considered as 'trafficking in persons' even if it does not involve any of the means set forth in the preceding paragraph" (p.1). [12]

Consistent with the above definition, study participants included both survivors of trafficking for sexual exploitation, as well as labor trafficking into domestic work.2) One participant was trafficked into sex work in Singapore. All other trafficking survivors in the program were trafficked to or within Cebu, Philippines. [13]

Socio-demographic characteristics of study participants are presented in Table 1. The average age of participants in Cohort A was 23.9, and the average age of participants in Cohort B was 23.0. All BARUG participants graduated from high school before or during the program; most survivors in BARUG had completed high school with support from one of the referring NGO partners. All survivors in Cohort A held salaried positions in a business process outsourcing social enterprise. Most survivors in Cohort B were employed part-time in an NGO-run handicraft business while pursuing further education with support from the same NGO. Monthly income for Cohort A participants was, on average, substantially higher than that of Cohort B participants. BARUG was primarily developed for survivors of human trafficking and their family members. As shown in Table 1, one survivor of physical abuse and labor exploitation also participated in the program, as the referring partners served persons who had experienced multiple forms of violence and exploitation.

|

|

Cohort A (n=9) |

Cohort B (n=6) |

Total (n=15) |

|

|

Background of participant |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Survivor of trafficking into domestic work |

2 |

3 |

5 |

|

|

Survivor of trafficking into sex work |

4 |

2 |

6 |

|

|

Physical abuse and labor exploitation survivor |

1 |

0 |

1 |

|

|

Intimate partner of survivor |

2 |

1 |

3 |

|

Gender |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Female |

6 |

4 |

10 |

|

|

Male |

3 |

2 |

5 |

|

Age |

|

|

|

|

|

|

20-25 |

6 |

5 |

11 |

|

|

26-30 |

3 |

1 |

4 |

Table 1: Socio-demographic characteristics of study participants [14]

We conducted a photovoice project upon completion of BARUG to give participants3) an opportunity to share their experiences in the program and provide feedback on how to improve the program. Participation in the photovoice project was optional for BARUG participants; 15 out of 16 participants chose to participate in the photovoice process. The research question for the study was: What has been your experience participating in BARUG? The research question was intentionally broad to encourage participants to highlight the aspects of their experience that were the most meaningful to them, promoting ownership over the process and shared power between program participants and research team members (FOSTER-FISHMAN et al., 2005; KOLB, 2008; NEWMAN, 2010; SUTTON-BROWN, 2014). Research ethics approval was obtained from George Mason University and the Philippines Department of Social Welfare and Development (DSWD). Participants were invited to select their own pseudonyms, which have been utilized in this manuscript. The photovoice facilitator was trained in ethical guidelines regarding research and programming with trafficked persons (UNITED NATIONS INTER-AGENCY PROJECT ON HUMAN TRAFFICKING, 2008; ZIMMERMAN & WATTS, 2003). [15]

The photovoice project proceeded in six stages, taking a total of four months. With the exception of the final community event, the photovoice process progressed separately for each cohort, as trust and rapport had already been established within each cohort. All discussions were conducted in Cebuano, the primary language spoken by participants. In the first meeting, an introduction to photovoice was provided, along with a basic photography lesson (CATALANI & MINKLER, 2010; JORGENSON & SULLIVAN, 2010; KOLB, 2008). The research question for the study was discussed and participants were invited to take photographs in response to the research question. Given the broad nature of the research question, all participants felt comfortable moving forward with this research question. Participants were asked not to take identifiable photographs of other people due to concerns regarding confidentiality and safety (CAPOUS-DESYLLAS & FORRO, 2014). Prior to the second meeting, participants took photographs and selected three to five of their own photographs that best represented their experiences in BARUG. [16]

During the second meeting, participatory visual analysis was conducted. Each participant brought his/her photographs to the meeting; photographs were displayed for all participants to see. Each participant was invited to share a narrative about each of his/her photographs, describing the meaning of the photograph and how that photograph represented his/her experiences in BARUG (MARCU, 2016; SUTTON-BROWN, 2014; WANG & BURRIS, 1997). This discussion of the photographs and their meaning was audio recorded. During this meeting, participants in each cohort were invited to join a leadership team, which was responsible for conducting qualitative analysis of the transcripts. In Cohort A, two survivors of sex trafficking volunteered for the leadership team and in Cohort B, one survivor of labor trafficking volunteered. [17]

Between the second and third sessions, a transcriptionist, who was bilingual in Cebuano and English, transcribed the second session's discussion verbatim in Cebuano and then translated the Cebuano transcript into English (LOPEZ, FIGUEROA, CONNOR & MALISKI, 2008). The transcriptionist had previously observed the second session as a non-participant observer. The transcriptionist preserved the original words used by participants as much as possible during translation; for concepts that were difficult to translate into English or for which the literal translation into English was not immediately clear, the transcriptionist was asked to provide a brief explanation of those phrases or concepts (LIAMPUTTONG, 2010). The photovoice facilitator, who was also bilingual, reviewed the translated version of the manuscript to ensure conceptual equivalence (IRVINE et al., 2007; LIAMPUTTONG, 2010; LOPEZ et al., 2008). [18]

In the third stage, data analysis was conducted collaboratively between the survivor leaders and one member of the research team, giving participants the opportunity to interpret and represent their own experiences in the program (CASHMAN et al., 2008; PHOENIX et al., 2016; VAUGHN et al., 2009). A member of the research team met with the survivor leaders in each cohort separately, training survivors on line-by-line coding and thematic analysis (BRAUN & CLARKE, 2006; HERSHBERG & LYKES, 2012; MARCU, 2016; PHOENIX et al., 2016). The data were analyzed using thematic analysis, a "method for identifying, analysing and reporting patterns (themes) within data" (BRAUN & CLARKE, 2006, p.79). An inductive approach to thematic analysis was utilized; themes were identified from the data themselves rather than trying to link the data with an existent coding frame (BRAUN & CLARKE, 2006; HERSHBERG & LYKES, 2012). Given that none of the participating survivors had ever conducted qualitative data analysis before this project, it was important for the method employed in this study to be accessible. Thematic analysis has been identified as a comprehensible method that is particularly suitable for new researchers (DeSANTIS & NOEL UGARRIZA, 2000; VAISMORADI, TURUNEN & BONDAS, 2013). Thematic analysis is also an appropriate tool for exploratory studies on understudied phenomenon (HERSHBERG & LYKES, 2012; VAISMORADI et al., 2013). In this project, thematic analysis progressed in five stages, as articulated by BRAUN and CLARKE (2006): familiarizing oneself with data, generating initial codes, searching for themes, reviewing themes, and defining and naming themes. First, the research team member and survivors familiarized themselves with the data through active, repeated reading of the transcripts. Survivors and the research team member independently reviewed the manuscripts and independently conducted initial line-by-line coding of the transcript from their respective cohort (CHARMAZ, 2006; SALDAÑA, 2009). Consistent with CHARMAZ (2006)'s approach, survivors were instructed to stick closely to the data through line-by-line coding, trying to "see actions in each segment of data rather than applying preexisting categories to the data" (p.47). Survivors were also encouraged to code using gerunds to capture participants' experiences as a process and to use in vivo codes to reflect participants' own language as much as possible (CHARMAZ, 2006). To simplify the analysis process for survivors who had never conducted data analysis before, only one round of coding was conducted and all coding was conducted by hand rather than through a computer program (DALEY et al., 2010). The research team member and survivors then compared their codes, discussed reasons for any discrepancies, and collectively agreed upon a code for each line (GUEST, MacQUEEN & NAMEY, 2012). Once the research team member and survivors completed the list of codes, the group reviewed the codes and sorted the codes into conceptually similar categories. The group compared categories and grouped them into themes. The research team member and survivors reviewed all possible themes, compared themes, defined and refined themes, and discussed the narratives associated with each theme (BRAUN & CLARKE, 2006; HERSHBERG & LYKES, 2012). Survivor leaders selected one to three photos to represent each of the preliminary themes. All data analysis was conducted in Cebuano, in the primary language of the survivors themselves. Transcripts, codes and themes were translated from Cebuano into English for publication (LIAMPUTTONG, 2010). [19]

In the fourth stage, a member check was conducted with each cohort regarding the themes and the photos identified by leadership team members. Minor revisions were made in response to participant and research team member input. Once themes were finalized, the next step in the photovoice process involved the implementation of a community event to share findings with the community (CATALANI & MINKLER, 2010; SUTTON-BROWN, 2014). The community event involved members of both cohorts, participants' family members, and community partners (n=38). The community event entailed a display of photographs taken by each cohort representing the themes identified by each cohort. At the community event, BARUG participants presented the themes from their respective cohort, with each participant sharing at least one narrative about their experience in the program (GERVAIS & RIVARD, 2013). A closing exercise was conducted with community partners, family members, and BARUG participants to give attendees an opportunity to reflect on lessons learned from the participants' experiences. [20]

Following completion of the community event, a Cebuano version of the study findings and implications was distributed to all BARUG participants for their review, constituting a second member check. Participants confirmed that the findings presented in this manuscript reflect their experiences. [21]

Participants in each cohort identified themes that represented their experience in BARUG, as shown in Table 2. While some of the themes were similar across cohorts, some themes were unique to a specific cohort. Themes will be presented separately for each cohort below.

|

Cohort A Themes |

Cohort B Themes |

|

Positive emotional impact of financial wellness |

Developing a habit of savings |

|

Receiving guidance and enlightenment |

Building a future-oriented mindset |

|

Overcoming the challenges of saving |

Learning process |

|

Applying financial management skills in daily decision making |

Applying financial management skills in daily decision making |

|

Change process |

|

Table 2: Summary of themes generated through the photovoice process [22]

3.1.1 Positive emotional impact of financial wellness

Participants consistently mentioned experiencing positive emotional benefits from improved financial stability. During the financial literacy training, participants in Cohort A revealed to the facilitator that they had each taken loans equivalent to the size of their monthly salary from a moneylender who charged them 20% interest each payday. Participants would spend their entire salary every payday repaying the debt, necessitating another loan and deeper indebtedness. As a result, we decided to support participants in paying off their debts to the moneylender, giving survivors the opportunity to repay their debts to BARUG over time with no interest. Through this intervention, all participants were able to get out of debt in 5 months. Participants described the emotional impact of getting out of debt. One survivor of sex trafficking, Hazel,4) took a photograph of a raised fist to depict her experience. She stated:

"I took this picture because I remember that I always think that I don't have hope in life because of lots of debts ... I even thought about committing suicide because my debt affected me so much. I kept thinking about it. I was irritable and I easily get angry. We always fight with my partner and parents because of my problems with debt, but now I feel hopeful again" (Hazel, age 29). [23]

Another sex trafficking survivor, Denise, described the emotional impact of the program by sharing a photograph she took of a dumbbell. She stated:

"I took this picture because as we know, the dumbbell is a heavy thing, right? This is heavy to carry especially if it is your first time to use it. But the good news is, as you constantly use it, you will feel that it somehow becomes lighter until you will feel that you are used to carrying it. If I compare it to what I experienced in this program...we felt the heavy moments, especially that we have debts ... They, the BARUG, helped me without asking something in return. They made me realize the importance of savings. That's why from being heavy like a dumbbell, I trained myself to keep money until I didn't notice that it became lighter. Just like a dumbbell, it helps ease out our problems in life. Example, if you exercise, you feel that your body is lighter, you don't feel tired easily, you don't feel stressed, and you don't feel the problem ... It may be heavy at first, but as you go along, you will be the one to benefit from your decision" (Denise, age 26). [24]

3.1.2 Receiving guidance and enlightenment

Participants described BARUG as a program that broadened their perspectives on financial management and exposed them to new ideas and skill-sets. In describing the knowledge they acquired during the program, several participants used the language of light and enlightenment. For instance, one sex trafficking survivor, Jasmin, indicated that participating in BARUG taught her the importance of savings: "It enlightened our mind to prioritize savings because in our case, we only saved when there is extra. But now, we think of setting aside money for savings" (Jasmin, age 22). Another participant took a picture of a candle to depict her experience in BARUG. She said:

"The next picture is a candle; this picture is, BARUG is like a candle that lights my life because before I was hooked in debt here and there. I don't have idea how, it's like there's darkness in my path ... But when BARUG came, it's like a candle has been lit and it lightened my way of understanding with teaching about savings...I also experienced guidance through its light that I can see now what I have not seen before in my life" (Mars, age 30). [25]

Denise's partner took a photograph of a sign depicting the words "This Way" to denote that participating in BARUG exposed him to a new way of managing finances. He said:

"I took this picture that shows a way. There are two ways in your life. It's either you take the way where you are already contented with what you have or way to be more successful. Before a person becomes successful, there will be challenges or circumstances that this face. I will present to them my experience in BARUG that showed me the way, that guided us ... I like to share this picture because I want that all people go through the way of success" (Kael, age 21). [26]

3.1.3 Overcoming the challenges of saving

Many participants in BARUG initially found saving money to be a challenging task. Participants noted that in the beginning they were not accustomed to the habit of saving and they felt discouraged about saving seemingly small amounts of money. However, as participants adjusted to the habit of regularly saving small amounts, they began to see the benefits of having money available for unexpected emergencies and expenses. Jericho, a survivor of labor trafficking, took a picture of a coconut tree to describe this concept. He explained:

"This is a photo of a coconut tree, which represents the time I waited in order for me to enjoy the delicious fruits of saving money. Before I joined BARUG, I struggled about how to handle money. I was a one-day millionaire. I spent money carelessly until the time came when I had to borrow money from a loan shark with high interest. At that time, I had no choice left but to borrow money because I need it. This happened repeatedly. Then BARUG taught me how to save, to prioritize, to have self-discipline, and to save for my future. I started saving small amounts and growing it took a long time. I pushed myself knowing that this {is} the right time to start planning for my future. The result of my hard work is delicious, just like the coconut. I feel comfortable now that I have money and savings. In the past, I took a motorcycle by debt and paid monthly installments, but it was repossessed because I cannot afford the payment. Now, I have another motorcycle, but this time I used my savings to buy a second-hand one in cash" (Jericho, age 24). [27]

Although the process of growing savings took time, Jericho noted that having savings made him feel "light-hearted" because he had money to pay for unanticipated emergencies—for himself as well as for his family and friends. [28]

3.1.4 Applying financial management skills in daily decision making

Participants described financial skills that they developed in the program and discussed how these skills impacted their daily lives. One survivor of labor trafficking, Chelsea, provided examples of financial management strategies she started implementing after participating in BARUG. For instance, she took a photograph of an expense list, stating:

"Having an expense list is very important to me. It serves as a guide that tells me what are the most important things we need in my household and in the family. It also stops me from buying things that are not necessary. Having a list is one of the ways that I was able to save money. Through this list, I also learn how to prioritize things. Even how difficult life is, we need to prioritize, as this will help us prepare for possible emergencies in the future. Prioritizing is not easy. It takes hard work, discipline, managing and choosing what is best for everyone and not just for yourself. What I do is that two days before my payday, I already make a list. I also encode what I spend in an excel sheet on a regular basis. The expense list helps me see the big picture and realities in life" (Chelsea, age 21). [29]

The same participant also took a photograph of an envelope with coins to depict another technique she developed in the program. She said:

"I used to struggle with budgeting before, especially during payday...When I joined BARUG, they helped me realize that there are many ways you can do to save money. One of the ways that helped me is the envelope system...I withdraw all my money from the ATM. Then I transfer specific amounts to each envelope designated for savings, groceries, transportation, rice, and allowance. I am proud to say that right now I save at least 25% of my salary every payday ... I consider the envelope system my friend or 'forever' in budgeting" (Chelsea). [30]

Other participants spoke about learning how to prioritize their expenses in light of competing demands. For instance, one survivor of sex trafficking, Jessica, took a photograph of a wallet, stating:

"Before I was drowned with debt because I was just thinking about providing everything for my family's needs, even if I'm not really capable of doing it. And that's because I wasn't able to manage my own finances. But when BARUG came, it was really life-changing. I became more responsible of my own money. I also was able to adjust providing my family's needs. I was able to prioritize things that I needed to buy and I was able to separate the things that I need and the things that I just want" (Jessica, age 22). [31]

In addition to setting aside money for her own needs, participant Jessica also explained that she now finds it helpful to set an average daily budget for herself. [32]

Participants described the changes they made in BARUG as a process that took time. For example, Jessica discussed adjustments she made to the way she allocated money within her family. At the beginning of the program, Jessica would give her entire salary to her mother, who gave Jessica a stipend for her daily needs. However, at times Jessica's mother spent Jessica's salary in its entirety, leaving Jessica without money for her transportation to work. In these instances, Jessica would borrow money from other family members and arrive late at work, leading to her suspension at work. While participating in BARUG, Jessica reduced the amount of money she gave to her family, first setting aside money for her own transportation, toiletries, food, and personal savings. She described this transition as a challenging one:

"The adjustment is really, really, really hard. That adjustment happen when I was able to pay off or pay my debt or a loan from BARUG to pay my debt ... I have to adjust the money I will be giving to my mother because I still have to have a budget for myself ... When I adjusted the money to my mother from 2000 to 1200 to 1300 to 1500 and sometimes 1000,5) she was offended. She was mad. She felt bad because she felt I was not valuing the sacrifices she was giving or the family is giving me because I was thinking, she thought I was thinking about myself. But then as time goes by she just understood that it's not just for me, not just for them, but for the betterment of the whole family" (Jessica). [33]

Another participant, Denise, described her own change process through a photograph she took of a set of stairs. She said:

"I took this photo from the downstairs to up because it somehow relates to my experience here in BARUG. It was like the very beginning we started from scratch in regard with our financial issues and how we're going to handle it. Yes we also have a lot of plans and dreams before about how are we gonna budget the small amount of money. But the challenge there is on how, where, and when to start stepping up, like the stairs here in the photo .. .Especially with our savings, we started with a small amount until there is a time that we are there meeting our goal. So it's just a matter of taking one step at a time to move forward ... It was really just starting even with one step...I like to share this photo because when you see stairs, it's like stepping stone towards your goals...We started from the beginning. Then the time goes by, we already reached here {the top}. It's up to you if you go back or you will go further" (Denise). [34]

3.2.1 Developing a habit of savings

Similar to participants in BARUG Cohort A, survivors in Cohort B articulated that joining BARUG helped them to foster a regular habit of savings. Genex, a survivor of labor trafficking, reflected upon changes in his savings habits due to his participation in BARUG. Prior to joining the program, Genex stated that while he wanted to save, he found himself unable to save regularly and he felt stressed about repaying his debts. As he explained, "panic was a regular part of my life. I panic a lot because after spending all my money, I would often find myself not having any left for transportation to work." Genex took a photograph of a highly organized rack of shoes to reflect the change in his savings habits during the program. He described the change in his habits as follows:

"I chose this picture because my saving methods before the BARUG was so chaotic ... Learning in BARUG was a process, and my finances become organized just like these slippers on the rack. It reflects my attitude because after payday, I sometimes forget that I need to save for my transportation. But now after BARUG, my saving methods and tactics are more organized" (Genex, age 26). [35]

In addition to discussing savings practices for their day-to-day expenses, participants also mentioned the importance of saving money in case of emergencies and unexpected situations. For example, one survivor of sex trafficking described an incident in which she used money she saved during the program to buy milk for her child when she ran out of money:

"I was enlightened that I should save so that whatever happens there is money that I can get ... When my child didn't have milk to drink, it's really difficult if I just rely on my family, Miss, because sometimes the one that we rely on, in my case our elder sibling, it's not always that they have money. At that time, I was thinking where to get money, even just a small amount, and the payday was still far and there was no milk anymore. I tried to text the father of my child, but he said that we have the same payday and sometimes he does not receive on actual date, so I was really confused where to get the money. That's why I tried to text Miss Dayeen6) if I can withdraw, even just 300...Although there is no match, it was ok at least I have something to give to my child" (Emily, age 22). [36]

3.2.2 Building a future-oriented mindset

Participants reported that joining BARUG helped them plan for the future and develop a stronger orientation toward the future. Genex's partner, Catherine, took a photograph of a person7) looking at a sign in front of local NGO serving trafficked persons. In describing this photograph, she said: "I chose this because in my saving, I look at the future. It's not that I am just in this level to save, but I also look at the future." She outlined specific steps that she took to plan for the future by stating:

"When I became pregnant with my last child, Genex and I set a savings goal for my maternity needs because we did not want have money problems when I give birth. To prepare for this event, we deposit a certain amount in our savings in BARUG every month so I feel confident knowing that I will have less money-related worries when I give birth. In fact, a few weeks before my due date, I already started applying for a match and paid for the requirements ... We were able to use the funds according to the plans and we saw just how beneficial it is to prepare for events like this by saving" (Catherine). [37]

Another participant, a labor trafficking survivor, took a photograph of a lock and key to depict how her thinking has changed while participating in BARUG. She stated that she chose this photograph because it depicted "a thing that locks our mindset on trivial things ... When I attended BARUG, I realized that it is not important to choose things, for example, cellphone that are high-end as long as you can still communicate with your family" (Joey, age 24). She further explained the change in her thinking from participating in BARUG:

"I have this mindset before that I can spend my money on any trivial or unimportant things like cellphone, accessories, dresses, or any gadget that can satisfy my wants. I spend without minding about possible emergencies that might happen in the future. One experience that I had was when my sister was hospitalized. I didn't have money at all to do what the doctor recommended. But when I entered BARUG, my mindset was totally changed. I realized that by buying my wants, I was only thinking short-term. After attending few of the sessions, I decided to save even if I do not have a big or regular income. I made saving into a habit." [38]

Participants described BARUG as a learning process, noting new skills that they acquired such as setting savings goals, prioritizing expenses, and saving money and paying off debt simultaneously. One of the participants, Catherine, took a photograph of a bookshelf to represent "the importance of learning and getting information about how to savings {sic}, which is a powerful weapon." While participants discussed the relevance of the knowledge they acquired through BARUG, they also expressed a desire to continue to strengthen their knowledge after the program ended. As reflected below, Catherine described the importance of seeking new sources of knowledge to supplement what she learned in BARUG.

"The bookshelf represents all ideas that I want to learn...It's important that we gather ideas so I search well and not just rely in one source of update ... that's why this bookshelf is what I chose because in saving money, we need to be wise. That's why we need accurate and enough information so that the money that we save will not go to waste ... You need to be knowledgeable and wise so that whatever we have saved will not be wasted" (Catherine, age 22). [39]

3.2.4 Applying financial management skills in daily decision making

Similar to participants in Cohort A, participants in Cohort B described ways in which they applied financial management skills they developed in BARUG to their daily decision making. One participant in Cohort B, Genex, took a photograph of an envelope to depict a savings habit that he developed in BARUG. In describing his photograph, he said: "This is a basic learning that I got from BARUG, the envelope method, wherein your budget in month will be put in an envelope and labeled where the money will be used ...This can be used after BARUG will end." [40]

Another participant, Richard, took a photograph of a cellphone to depict his financial decision-making. Richard, a labor trafficking survivor, explained that he purchased a small, simple cellphone because it was affordable, saving money and enabling him to use the money he saved for more important purposes. In reflecting on his financial habits, Richard discussed the difficult decisions he had to make about how to allocate his financial resources when he received requests from his family for financial support. He described the challenges he faced saving money for his own needs while also desiring to provide financially for his extended family:

"In spending money, I always set limitations. I think very hard before spending. I do this not only when buying things, but also when giving money to my relatives in the province. For me it is okay to give, but I decided to put a limitation. I feel sad when I don't give them everything they want, but I also made them understand that I cannot always give them what they ask for because I was trying to save for my education...Because of my decision, I was able to save for my schooling" (Richard, age 24). [41]

While participating in BARUG, Richard set a savings goal for himself to pay for his college education through his own savings. During BARUG, Richard used his savings and matched funds to pay for his second year of college studying mechanical engineering, which he hopes will enable him to secure more stable employment and be in a better position to provide financially for his extended family. [42]

To our knowledge, the current study is the first to use photovoice with survivors of human trafficking. Photovoice provided an accessible mechanism through which survivors and their family members could share their lived experiences, be actively engaged in all stages of the research process, and provide programmatic feedback instrumental to improving the intervention (GERVAIS & RIVARD, 2013; MIYOSHI & STENNING, 2008; SUTTON-BROWN, 2011). Participants expressed excitement about the photovoice project and pride in their work. Findings demonstrate both the feasibility and benefits of using participatory research approaches like photovoice with people who have been trafficked. Prior research has identified retention issues and loss to follow-up as key challenges in research with trafficked persons (CHOO, JANG & CHOI, 2010; CWIKEL & HOBAN, 2005). This study, however, demonstrates that it is possible to engage trafficked persons in an extended participatory research process if a foundation of trust has been established with survivors from the outset. [43]

The current study reinforces the critical importance of listening to survivors' perspectives on their own experiences and partnering with survivors in assessing and refining services in the counter-trafficking sector (BOONTINAND, 2012). Participatory approaches have been underutilized in research on human trafficking and research presenting the perspectives of trafficked persons on their own experiences is lacking (AGHAZARM & LACZKO, 2008). The broader lack of survivor participation in the human trafficking research literature echoes concerns regarding the paternalism inherent in many common approaches to addressing human trafficking. Scholars and practitioners have consistently critiqued dominant factions of the counter-trafficking movement for intervening on behalf of trafficked persons without listening to, partnering with, or respecting the agency of those experiencing exploitation (CHEW, 2012; KEMPADOO, 2012; LIMONCELLI, 2009; MEYERS, 2014). It is essential that efforts to improve services in the counter-trafficking movement be conducted in partnership with trafficked persons themselves and with survivors' voices at the center of such reform efforts. [44]

In the current study, trafficking survivors and their family members were actively engaged not only in sharing their perspectives on the BARUG program, but also in analyzing the data they generated themselves. Findings hold implications for the design of reintegration support services that are sensitive to the experiences and perspectives of trafficked persons and their family members. During the photovoice process, trafficking survivors and their family members provided feedback instrumental to shaping the future of the program. For instance, BARUG was originally designed as a savings and financial capability program; the debt repayment component of the program was not included in the initial design of BARUG. However, the support participants received in exiting a cycle of debt appeared to be one of the most vital aspects of the program for their emotional well-being and one of the most urgent concerns for survivors themselves (BRUNOVSKIS & SURTEES, 2012a; SMITH-BRAKE et al., 2015). While scholars have noted that trafficked persons often incur debt during the migration process (BRUNOVSKIS & SURTEES, 2012a, 2012b), this was not the case for participants in this study. Instead, similar to SMITH-BRAKE et al.'s (2015) findings with reintegrated trafficking survivors in Cambodia, participants in this study (survivors and family members) were often entrenched in a regular cycle of debt from which they felt unable to exit. This debt was incurred at a familial level to cover daily needs and medical expenses. High levels of debt upon reintegration can heighten vulnerability, including vulnerability to re-trafficking (BRUNOVSKIS & SURTEES, 2012a). Findings not only reinforce the importance of safety nets for survivors and their families in times of crisis, but also highlight the importance of integrating financial education and debt reduction services into economic empowerment programming for survivors. [45]

Second, findings highlight the value of incorporating asset development into economic empowerment programming for trafficked persons and their families. Participants reported both financial and psychological benefits of asset development, expressing that having assets stimulated hope, created an orientation toward the future, built self-efficacy, and improved household stability by cushioning income shocks (SHERRADEN, 1991). These gains should not be underestimated. Prior research in the Philippines has shown that trafficked persons are often the ones that family members run to for help in times of crisis, reinforcing the importance of protection against financial shocks (TSAI, 2017a). Many trafficking survivors do not have networks they can turn to in emergencies, meaning that even temporary financial setbacks can have devastating consequences (BRUNOVSKIS & SURTEES, 2012a; SMITH-BRAKE et al, 2015). Research with trafficked persons has revealed high levels of financial anxiety, hopelessness, difficulties planning for the future, and challenges with delayed gratification (ARTADI, BJORKMAN & LA FERRARA, 2011; BRUNOVSKIS & SURTEES, 2012b; SMITH-BRAKE et al., 2015). When survivors are living at a subsistence level and face regular financial pressure from family members, it can be difficult to imagine a better future and/or take concrete steps toward that future, further heightening their vulnerability (SMITH-BRAKE et al., 2015). Participants in this study described BARUG as a program that helped them foster an orientation toward the future, feel more hopeful about the future, and regain a sense of control over their financial situation. Such gains have the potential for crosscutting impacts in many facets of survivors' lives, including their emotional well-being and family stability. [46]

Additionally, findings underscore the importance of services that not only help survivors attain their financial goals, but that also provide an emotionally supportive environment in which survivors can process financial pressures they may be experiencing in their families. Consistent with prior research, the current study reinforces the significance of financial pressures that trafficked persons often face within their families after exiting trafficking and the important role that survivors play in providing for family members (BRUNOVSKIS & SURTEES, 2012b; SIMKHADA, 2008; TSAI, 2017a, 2017b). Survivors in the photovoice project wrestled with the nature and degree of their responsibility to their extended families when confronted with their own needs (BRUNOVSKIS & SURTEES, 2012b; SMITH-BRAKE et al., 2015). In cultural contexts in which the well-being of the family as a collective is highly prioritized, survivors' sense of self is deeply connected to their families (LE, 2016). However, family financial obligations can also impair the psychosocial well-being of survivors, leading to hopelessness, despair, inability to concentrate, thoughts of suicide, and lack of motivation, among others (SMITH-BRAKE et al., 2015). Thus, the family plays a key role in the community reintegration process, both as a facilitator and inhibitor of integration (BRUNOVSKIS & SURTEES, 2012a, 2012b; SURTEES, 2013). This delicate tension reflects the importance of providing forums for trafficked persons to dialogue openly about filial piety and financial anxiety within the family (SMITH-BRAKE et al., 2015). Feedback from participants suggested that BARUG was a safe space in which survivors could explore these tensions and gradually achieve greater resolution on how to meet their own needs while also fulfilling responsibilities to their families. [47]

Findings should be considered in light of limitations. Although we carefully invited participants to share both positive and negative experiences in BARUG, participants overwhelmingly provided positive feedback on the program, raising concerns regarding social desirability bias. Prior to conducting the photovoice assessment, the BARUG team had facilitated several informal sessions with participants throughout the program to solicit their views on the program. In these sessions, participants provided both positive and negative feedback. Although participants were actively invited to continue to do the same in the photovoice project, this did not occur. Secondly, survivors' trafficking histories were not explicitly discussed during the BARUG intervention or the photovoice project. The photovoice project was implemented in a group setting in which non-trafficked family members were also present. The facilitator was trained to not raise the topic of human trafficking in order to preserve the confidentiality of survivors, as many survivors choose not to disclose their trafficking histories to family members due to concerns regarding social stigma (BRUNOVSKIS & SURTEES, 2012b). As a result, it was not possible to explore how survivors' trafficking histories may have affected their views on the program. [48]

In the counter-trafficking sector, substantial attention has been given to the human rights abuses that occur during the trafficking process; less consideration has been directed toward the vulnerability experienced by survivors upon their exit from human trafficking and return to life in the community (RICHARDSON et al., 2009). However, as referenced earlier, when survivors exit human trafficking, the circumstances that initially made them vulnerable to being trafficking are commonly still present, including lack of access to safe employment, absence of savings, familial debts, financial responsibility for family members, and the lack of a safety net in times of financial crisis (BRUNOVSKIS & SURTEES, 2012a; JOBE, 2010; LE, 2016; RICHARDSON et al., 2009; SMITH-BRAKE et al., 2015; TSAI, 2017a, 2017b). Financial concerns are often a key priority for survivors themselves upon community re-entry (LISBORG, 2009). Nevertheless, evidence-based models for supporting the economic security of survivors during the community reintegration process remain limited. [49]

In the current study, we utilized photovoice to understand the experiences of trafficking survivors and their family members in the BARUG program. The current study is, to our knowledge, the first study to use photovoice and one of the first to utilize a participatory research methodology with survivors of human trafficking. The photovoice method is rooted in the belief that people have a right to define their own experiences and participate in policy and programming decisions that impact their own lives (WANG, 1999). It is essential for trafficked persons to be engaged as partners in the process of building an evidence base around effective reintegration support and economic empowerment programming in the counter-trafficking sector. In research pertaining to empowerment programming, the means of collecting data should "not contradict the aims of empowerment" (RAPPAPORT, 1990, p.53). Participatory research approaches, such as photovoice, have the potential not only to generate data that is instrumental to improving economic empowerment programming for trafficked persons, but also empower survivors during the research process (FOSTER-FISHMAN et al., 2005). [50]

Findings hold important implications for policy and practice pertaining to reintegration support programming for trafficked persons. Reintegration support interventions must be developed with sensitivity to the sociocultural realities of survivors, including family, gender, generational, and cultural norms surrounding financial responsibility and decision-making (TSAI, 2017d). Findings underscore that economic empowerment for trafficking survivors cannot be reduced to a single dimension, such as access to employment. As articulated by survivors themselves, the study reinforces the importance of reintegration support interventions that support survivors in reducing debt and building assets as a safety net in times of financial crisis. Further, interventions striving to empower trafficked persons economically must also consider the household structures and dynamics that impact the use of financial resources (TSAI, 2017c). Findings reinforce the importance of interventions that provide emotional support to help survivors cope with financial pressures experienced during the community re-entry process (BRUNOVSKIS & SURTEES, 2012a, 2012b). Additionally, findings highlight the importance of safe, supportive environments in which survivors and their family members can explore family tensions surrounding financial responsibilities and achieve greater resolution on how to meet family and individual needs. [51]

Despite the important implications suggested here, this study has only begun to explore the potential value of financial capability, asset development, and debt reduction interventions in promoting the financial security of trafficked persons. Future research in this area should examine alternative models for supporting the financial security of trafficking survivors and providing emotional support to survivors during the community re-entry process. It is also recommended that future research be conducted in partnership with trafficked persons, with survivor voices at the center of efforts to improve reintegration support interventions in the counter-trafficking sector. [52]

Many thanks to the BARUG participants for sharing your life experiences and teaching us through the photovoice process. Thanks to Dayeen TUDTUD and Cherry BONACHITA for your assistance in implementing BARUG.

1) Eleison Foundation is a private operating foundation based in the United States that holds a representative office in the Philippines. The Foundation implements, funds, and conducts research pertaining to reintegration support programming for survivors of human trafficking. <back>

2) It is important to note that adults who voluntarily engage in sex work are not considered sex trafficking victims. However, any person who is forced to engage in sex work through any of the means included in this definition (i.e., force, fraud or coercion) would be classified as a trafficking victim (REPUBLIC ACT NUMBER 10364, 2012; UNITED NATIONS, 2000).Definitions of human trafficking are highly contested (CAVALIERI, 2011). However, a complete discussion of the controversy surrounding these definitions is beyond the scope of this article. <back>

3) The term "participant" refers to all BARUG participants, while "survivor" and "family member" will be used to refer to participants who fit these parts of the sample. <back>

4) Participants were invited to select their own pseudonyms, which have been utilized in this manuscript. <back>

5) The participant was referring to Philippine pesos. <back>

6) Dayeen was an employee of Eleison Foundation. She was responsible for collecting savings during BARUG. <back>

7) The person in the photograph was a staff member for the BARUG program. The photograph was taken from behind and as such the identity of the person in the photograph could not be determined by looking at the photograph. <back>

Abrams, Laura S. (2010). Sampling "hard to reach" populations in qualitative research: The case of incarcerated youth. Qualitative Social Work, 9(4), 536-550.

Aghazarm, Christine & Laczko, Frank (2008). Human trafficking: New directions for research. Geneva: International Organization for Migration.

Artadi, Elsa; Bjorkman, Martina & La Ferrara, Eliana (2011). Factors of vulnerability to human trafficking and prospects for reintegration of former victims: Evidence from the Philippines. Milano: Bocconi University.

Asis, Maruja Milagros B.; Huang, Shirlena & Yeoh, Brenda, S. A. (2004). When the light of the home is abroad: Unskilled female migration and the Filipino family. Singapore Journal of Tropical Geography, 25(2), 198-215.

Bales, Kevin (2011). What predicts human trafficking? International Journal of Comparative and Applied Criminal Justice, 31(2), 269-279.

Bandura, Albert (1986). Social foundations of thought and action: A social and cognitive theory. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall.

Bandura, Albert (1997). Self-efficacy: The exercise of control. New York: W.H. Freeman and Company.

Bishop, Jeffery; Robillard, Linda & Moxley, David (2013). Linda's story through photovoice: Achieving independent living with dignity and ingenuity in the face of environmental inequities. Practice, 25(5), 297-315.

Boontinand, Jan (2012). Feminist participatory action research in the Mekong region. In Kamala Kempadoo, Jyoti Sanghera & Bandana Pattanaik (Eds.), Trafficking and prostitution reconsidered: New perspectives on migration, sex work, and human rights (pp.175-198). Boulder, CO: Paradigm Publishers.

Braun, Virginia & Clarke, Victoria (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(1), 77-101.

Brunovskis, Anette & Surtees, Rebecca (2012a). A fuller picture. Addressing trafficking-related assistance needs and socio-economic vulnerabilities. Oslo: NEXUS Institute, https://nexushumantrafficking.files.wordpress.com/2015/03/a-fuller-picture_assistance-needs_nexus.pdf [Accessed: June 3, 2016].

Brunovskis, Anette & Surtees, Rebecca (2012b). Coming home: Challenges in family reintegration for trafficked women. Qualitative Social Work, 12(4), 454-472.

Bukowski, Kate & Buetow, Stephen (2011). Making the invisible visible: A photovoice exploration of homeless women's health and lives in central Auckland. Social Science & Medicine, 72(5), 739-746.

Cabassa, Leopoldo J.; Parcesepe, Angela; Nicasio, Andel; Baxter, Ellen; Tsemberis, Sam & Lewis-Fernández, Roberto (2012). Health and wellness photovoice project engaging consumers with serious mental illness in health care interventions. Qualitative Health Research, 23(5), 618-630.

Capous-Desyllas, Moshoula & Forro, Vanessa (2014). Using photovoice with sex workers: The power of art, agency and resistance. Qualitative Social Work, 13, 477-501.

Cargo, Margaret & Mercer, Shawna L. (2008). The value and challenges of participatory research: Strengthening its practice. Annual Review of Public Health, 29, 325-350.

Cashman, Suzanne B.; Adeky, Sarah; Allen III, Alex J.; Corburn, Jason; Israel, Barbara A.; Montaño, Jamie; Rafelito, Alvin; Rhodes, Scott D.; Swanston, Samara; Wallerstein, Nina & Eng, Eugenia (2008). The power and the promise: Working with communities to analyze data, interpret findings, and get to outcomes. American Journal of Public Health, 98(8), 1407-1417.

Castleden, Heather; Garvin, Theresa & Huu-ay-aht First Nation (2008). Modifying photovoice for community-based participatory Indigenous research. Social Science & Medicine, 66(6), 1393-1405.

Catalani, Carcia & Minkler, Meredith (2010). Photovoice: A review of literature in health and public health. Health Education & Behavior, 37(3), 424-451.

Cavalieri, Shelley (2011). Between victim and agent: A third-way feminist account of trafficking for sex work. Indiana Law Journal, 86(4), 1409-1458.

Charmaz, Kathy (2006). Constructing grounded theory: A practical guide through qualitative analysis. Los Angeles, CA: Sage.

Chew, Lin (2012). Reflections by an anti-trafficking activist. In Kamala Kempadoo, Jyoti Sanghera & Bandana Pattanaik (Eds.), Trafficking and prostitution reconsidered: New perspectives on migration, sex work, and human rights (pp.65-82). Boulder, CO: Paradigm Publishers.

Choo, Kyungseok; Jang, Joon Oh & Choi, Kyungshick (2010). Methodological and ethical challenges to conducting human trafficking studies: A case study of Korean trafficking and smuggling for sexual exploitation to the United States. Women & Criminal Justice, 20(1-2), 167-185.

Curley, Jamie; Ssewamala, Fred & Sherraden, Michael (2009). Institutions and savings in low-income households. Journal of Sociology & Social Welfare, 36(3), 9-32.

Cwikel, Julie & Hoban, Elizabeth (2005). Contentious issues in research on trafficked women working in the sex industry: Study design, ethics, and methodology. The Journal of Sex Research, 42(4), 306-316.

Daley, Christine Makosky; James, Aimee S.; Ulrey, Ezekiel; Joseph, Stephanie; Talawyma, Angelia; Choi, Won S.; Greiner, K. Allen & Coe, M. & Coe, Kathryn (2010). Using focus groups in community-based participatory research: Challenges and resolutions. Qualitative Health Research, 20(5), 697-706.

DeSantis, Lydia & Noel Ugarriza, Doris (2000). The concept of theme as used in qualitative nursing research. Western Journal of Nursing Research, 22(3), 351-372.

Easton, Helen & Matthews, Roger (2016). Getting the balance right: The ethics of researching women trafficked for commercial sexual exploitation. In Dina Siegel & Roos de Wildt (Eds.), Ethical concerns in research on human trafficking (pp.11-32). Heidelberg: Springer.

ECPAT International (2016). Sex trafficking of children in the Philippines. Bangkok: ECPAT International, http://www.ecpat.org/wp-content/uploads/legacy/Factsheet_Philippines.pdf [Accessed: March 14, 2017].

Foster-Fishman, Pennie; Nowell, Branda; Deacon, Zermarie; Nievar, Angela & McCann, Peggy (2005). Using methods that matter: The impact of reflection, dialogue, and voice. American Journal of Community Psychology, 36(3-4), 275-291.

Freire, Paulo (1970). Pedagogy of the oppressed. New York: Continuum Publishing.

Fry, Tim R.; Mihajilo, Sandra; Russell, Roslyn & Brooks, Robert (2008). The factors influencing saving in a matched savings program: Goals, knowledge of payment instruments, and other behavior. Journal of Family and Economic Issues, 29(2), 234-250.

Galam, Roderick G. (2015). Gender, reflexivity, and positionality in male research in one's own community with Filipino seafarers' wives. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung / Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 16(3), Art. 13, http://nbn-resolving.de/urn:nbn:de:0114-fqs1503139 [Accessed: March 10, 2017].

Gervais, Myriam & Rivard, Lysanne (2013). "SMART" photovoice agricultural consultation: Increasing Rwandan women farmers' active participation in development. Development in Practice, 23(4), 496-510.

Guest, Greg; MacQueen, Kathleen M. & Namey, Emily E. (2012). Applied thematic analysis. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Guruge, Sepali; Hynie, Michaela; Shakya, Yogendra; Akbari, Arzo; Htoo, Sheila & Abiyo, Stella (2015). Refugee youth and migration: Using arts-informed research to understand changes in their roles and responsibilities. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung / Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 16(3), Art. 15, http://nbn-resolving.de/urn:nbn:de:0114-fqs1503156 [Accessed: March 10, 2017].

Hershberg, Rachel M. & Lykes, M. Brinton (2012). Redefining family: Transnational girls narrate experiences of parental migration, detention, and deportation. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung / Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 14(1), Art. 5, http://nbn-resolving.de/urn:nbn:de:0114-fqs130157 [Accessed: March 10, 2017].

Irvine, Fiona E.; Lloyd, David; Jones, Peter R.; Allsup, David M.; Kakehashi, Bangor C.; Ogi, Ayako & Okuyama, Mayumi (2007). Lost in translation? Undertaking transcultural qualitative research. Nurse Researcher, 14(3), 46-59.

Jobe, Alison (2010). The causes and consequences of re-trafficking: Evidence from the IOM Human Trafficking Database. Geneva: IOM, https://publications.iom.int/system/files/pdf/causes_of_retrafficking.pdf [Accessed: March 1, 2017].

Jocano, Felipe Landa (1998). Filipino social organization: Traditional kinship and family organization. Manila: Punlad Research House.

Jorgenson, Jane & Sullivan, Tracy (2010). Accessing children's perspectives through participatory photo interviews. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung / Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 11(1), Art. 8, http://nbn-resolving.de/urn:nbn:de:0114-fqs100189 [Accessed: March 10, 2017].

Kelly, Liz & Coy, Maddy (2016). Ethics as process, ethics in practice: Researching the sex industry and trafficking. In Dina Siegel & Roos de Wildt (Eds.), Ethical concerns in research on human trafficking (pp.33-50). Heidelberg: Springer.

Kempadoo, Kamala (2012). The anti-trafficking juggernaut rolls on. In Kamala Kempadoo, Jyoti Sanghera & Bandana Pattanaik (Eds.), Trafficking and prostitution reconsidered: New perspectives on migration, sex work, and human rights (pp.249-260). Boulder, CO: Paradigm Publishers.

Kolb, Bettina (2008). Involving, sharing, analysing—potential of the participatory photo interview. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung / Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 9(3), Art. 12, http://nbn-resolving.de/urn:nbn:de:0114-fqs0803127 [Accessed: March 10, 2017].

Le, PhuongThao D. (2016). Reconstructing a sense of self: Trauma and coping among returned women survivors of human trafficking in Vietnam. Qualitative Health Research, 24(4), 1-11.

Liamputtong, Pranee (2010). Performing qualitative cross-cultural research. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Limoncelli, Stephanie A. (2009). Human trafficking: Globalization, exploitation, and transnational sociology. Sociology Compass, 3(1), 72-91.

Lisborg, Anders (2009). Rethinking re-integration. What do returning victims really want and need? Evidence from Thailand and the Philippines. Bangkok: UNIAP, http://un-act.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/07/SIREN_GMS-07.pdf [Accessed: May 27, 2016].

Lopez, Griselda I.; Figueroa, Maria; Connor, Sarah E.; & Maliski, Sally L. (2008). Translation barriers in conducting qualitative research with Spanish speakers. Qualitative Health Research, 18(12), 1729-1737.

Marcu, Oana (2016). Using participatory, visual and biographical methods with Roma youth. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung / Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 17(1), Art. 5, http://nbn-resolving.de/urn:nbn:de:0114-fqs160155 [Accessed: March 10, 2017].

Medina, Belen Tan Gatue (2001). The Filipino family (2nd ed). Diliman, Quezon City: University of the Philippines Press.

Meyers, Diana T. (2014). Feminism and sex trafficking: Rethinking some aspects of autonomy and paternalism. Ethical Theory and Moral Practice, 17(3), 427-441.

Microfinance Opportunities (2002). Global financial education program. Washington, DC: Microfinance Opportunities.

Minkler, Meredith (2004). Ethical challenges for the "outside" researcher in community-based participatory research. Health Education & Behavior, 31(6), 684-697.

Miyoshi, Koichi & Stenning, Naomi (2008). Designing participatory evaluation for community capacity development: A theory-driven approach. Japanese Journal of Evaluation Studies, 8(2), 39-53.

Molloy, Jennifer K. (2007). Photovoice as a tool for social justice workers. Journal of Progressive Human Services, 18(2), 39-55.

Newman, Susan D. (2010). Evidence-based advocacy: Using photovoice to identify barriers and facilitators to community participation after spinal cord injury. Rehabilitation Nursing, 35(2), 47-59.

Palmer, David; Williams, Lucy; White, Sue; Chenga, Charity; Calabria, Verusca; Branch, Dawn; Arundal, Sue; Storer, Linda; Ash, Chris; Cuthill, Claire; Bezuayehu, Haile & Hatzidimitriadou, Eleni (2009). "No one knows like we do"—the narratives of mental health service users trained as researchers. Journal of Public Mental Health, 8(4), 18-28.

Phoenix, Ann; Brannen, Julia; Elliott, Heather; Smithson, Janet; Morris, Paulette; Smart, Cordet; Barlow, Ann & Bauer, Elaine (2016). Group analysis in practice: Narrative approaches. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung / Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 17(2), Art. 9, http://nbn-resolving.de/urn:nbn:de:0114-fqs160294 [Accessed: March 10, 2017].

Rappaport, Julian (1990). Research methods and the empowerment social agenda. In Patrick Tolan; Christopher Keys; Fern Chertok & Leonard A. Jason (Eds.), Researching community psychology: Issues of theory and methods (pp.51-63). Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

Republic Act Number 10364 (2012). Expanded anti-trafficking in persons act. Republic of the Philippines. Metro Manila: Congress of the Philippines. Official Gazette, http://www.gov.ph/2013/02/06/republic-act-no-10364/ [Accessed: November 1, 2016].

Richardson, Diane; Poudel, Meena & Laurie, Nina (2009). Sexual trafficking in Nepal: Constructing citizenship and livelihoods. Gender, Place and Culture, 16(3), 259-278.

Robinson, Oliver C. (2014). Sampling in interview-based qualitative research: A theoretical and practical guide. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 11(1), 25-41.

Saldaña, Johnny (2009). The coding manual for qualitative researchers. Los Angeles, CA: Sage.

Sherraden, Michael (1990). Stakeholding: Notes on a theory of welfare based on assets. Social Service Review, 64(4), 580-601.

Sherraden, Michael (1991). Assets and the poor. Armonk, NY: M.E. Sharpe, Inc.

Sherraden, Michael; Williams, Trina; McBride, Amanda M. & Ssewamala, Fred M. (2004). Overcoming poverty: Supported savings as a household development strategy. St. Louis, MO: Washington University in St. Louis, Center for Social Development.

Simkhada, Padam (2008). Life histories and survival strategies amongst sexually trafficked girls in Nepal. Children and Society, 22(3), 235-248.

Smith-Brake, Julia; Lim, Vanntheary & Nhanh, Channtha (2015). Economic reintegration of survivors of sex trafficking: Experiences of filial piety and financial anxiety. Phnom Penh: Chab Dai.

Surtees, Rebecca (2012). Re/integration of trafficked persons: Supporting economic empowerment. Brussels: King Badouin Foundation, https://ec.europa.eu/anti-trafficking/sites/antitrafficking/files/reintegration_of_trafficked_persons_supporting_economic_empowerment_1.pdf [Accessed: May 23, 2016].

Surtees, Rebecca (2013). After trafficking: Experiences and challenges in the (re)integration of trafficked persons in the Greater Mekong Sub-region. Bangkok: UNIAP/NEXUS Institute, http://un-act.org/publication/view/trafficking-experiences-challenges-reintegration-trafficked-persons-greater-mekong-sub-region/ [Accessed: June 7, 2016].