Volume 19, No. 2, Art. 16 – May 2018

The Creative and Rigorous Use of Art in Health Care Research

Megan Nguyen

Abstract: The adoption of arts-based research methods is gaining popularity in health care yet few of these methods integrate the arts throughout the inquiry. Given that so much of the human experience is imbued with emotion and complexity, it would be counter-intuitive to omit research methods, such as the arts, that mobilize different ways of thinking. The purpose of this article is to discuss the creative and rigorous use of art throughout the research process, drawing on the example of a graduate research study that explored women's narratives of intimate relationships while living with irritable bowel syndrome. The findings reveal that the arts can evoke a different kind of knowing and can portray the artist's personal thoughts and feelings without the use of words. Embracing creative functioning through the arts necessitates surrendering conventional ways of pursuing knowledge. This work advances research to date on arts methodology by explicating how the arts can be used to support each stage of the research.

Key words: arts-based research; arts-informed research; qualitative inquiry; qualitative methodology; intimate relationships; health care research; irritable bowel syndrome

Table of Contents

1. Introduction

2. Background

3. Engaging Art and Reflexivity

4. Using Art in Literature Syntheses

5. Using Art in Theory and Methodology

6. Using Art in Data Collection Methods

7. Using Art in Findings and Interpretation

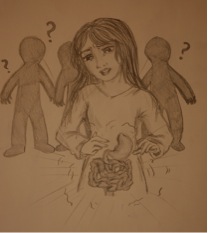

8. Using Art in Dissemination

9. Conclusion

Qualitative research often pertains to the indefinable and unfathomable and thus necessitates an approach that embraces creative and imaginative inquiry (GUNARATNAM, 2007; McNIFF, 2011). In my graduate research (NGUYEN, 2015), I embarked upon an artistic inquiry to explore women's narratives of intimate relationships while living with irritable bowel syndrome (IBS). I used narrative interviews, an arts-informed activity, and drew upon critical feminist theory to gain a deeper and contextualized understanding of women's personal narratives. The decision to incorporate art into my study was born from early discussions with my graduate supervisor where we learned of our shared interest in the arts. Following these discussions about the use of poetry in her doctoral research, my personal interest in sketching, and the emergence of art in health care research, we explored the potential of integrating the arts into my study. The use of art emerged as a method in my study when my supervisor asked me to systematically journal a reflexive account throughout the research in any way that I could best articulate my assumptions, biases, and interpretive conclusions. Sketching became a method that allowed me to explicate reflexive accounts that were authentic and rigorous. Similar to previous arts-based research in health care, I had initially intended to use art as a data collection method and a medium of data that would be analyzed. In addition, I had planned to use art as a tool for reflexivity. However, the use of arts evolved as I moved through each stage of the research, unexpectedly playing a more profound role than I had anticipated. Similar to the practice of a/r/tography, I wholly immersed myself in the inquiry as both artist and researcher, engaging the interconnectedness between my identities to invite new ways of imagining and understanding (SPRINGGAY, IRWIN, LEGGO & GOUZOUASIS, 2008). My immersion in and active engagement with the artistic process opened my awareness to the invaluable role that art can play within and throughout qualitative inquiry. This finding provides direction with regard to advancing arts-based research within the field of health care by integrating the arts throughout the research process rather than confining its use to the stages of data collection and analysis. [1]

The purpose of this article is to discuss the creative and rigorous use of the arts throughout the research process. The use of art in a progressive manner is demonstrated in all domains of the research study. The use of first person writing style is integrated throughout this article to capture my personal journey as artist and researcher. However, I preface that it was through a collaborative effort with my thesis supervisor and committee members that this work flourished. [2]

First, I will detail the rationale for incorporating the arts into my graduate study and then provide an overview on arts-based research and its adoption in the field of health. Next, I will discuss the potential value and engagement of art throughout the research process by drawing on my experience of using art in all stages of my graduate study (in reflexivity, the literature synthesis, theory and methodology, data collection methods, findings and interpretation, and dissemination). I will conclude with a reflection on engaging art in my graduate research and potential arenas for future arts-based research. [3]

The adoption of arts-based research methods is steadily gaining popularity in the field of health care (HODGINS & BOYDELL, 2014; LAPUM, RUTTONSHA, CHURCH, YAU & MATTHEWS DAVID, 2012). Arts-based research is a method of inquiry in which art constitutes the foundation of systematic investigation (LEDGER & McCAFFREY, 2015; McNIFF, 2011). Often, arts-informed research is differentiated as involving the integration of art into the inquiry; however, it does not comprise the basis of exploration (KNOWLES & COLE, 2008). In my study, an arts-informed approach was utilized. A narrative methodology, underpinned by critical feminist theory acted as the basis of inquiry and the systematic framework into which the arts were integrated throughout to support rigor, reflexivity, and analysis and to enrich the data. From a critical feminist perspective, the social, gendered, historical, and political processes that mediate dialogue (SCOTT, 1999) and the stigma surrounding bowel problems might have constrained how participants told their stories in addition to what they recounted (NGUYEN, 2015). Furthermore, these processes shaped and impacted the way I, as the researcher engaged with the inquiry, from the questions I asked to the way I interpreted the data. As such, I felt that it would be valuable and fitting to use an arts-informed methodology in combination with a critical feminist lens because both aim to shed light on and challenge taken-for-granted ways of thinking and knowing (LEAVY, 2015; SCOTT, 1987). Furthermore, both approaches involve introspection and the intention to deeply understand rather than merely describe phenomena (ibid.). It is through the interruption of dominant ways of thinking that change can be imagined and negotiated to empower those that are constrained by such ideologies (HOOKS, 1995; SCOTT, 1999). It was my hope to shed light on and understand the potential attitudes and practices in IBS care that constrain women's voices and experiences in order to understand the way care can be improved. Maintaining the lens of critical feminism heightened my sensitivity to and awareness of my assumptions and preconceptions about gender, intimate relationships, and IBS, thereby enabling a deep and critical navigation of the research. In so doing, I was able to uncover the layers of the women's stories by using both a critical feminist perspective and an arts-informed narrative approach. [4]

The employment of art as a means of inquiry carries powerful potential in health care research because of its capacity to convey and represent experiences using variable and unique forms of expression (CAPOUS-DESYLLAS, 2013; OSEI-KOFI, 2013). Artistic expression in research transpires in an infinite number of forms, including poetry (LAPUM, YAU & CHURCH, 2015), sculptures, collage (KLORER, 2014), sketches (HENARE, HOCKING & SMYTHE, 2003; HUSS, KAUFMAN, AVGAR & SHOUKER, 2015), creative writing (MacDONNELL & MacDONALD, 2011), dance (BOYDELL, 2011), and installation art (LAPUM et al., 2012). [5]

The arts have triggered emotion, augmented deep reflection, and emulated one's inner reality through their symbolism (JACK, 2012; LATHAM, 2014; RIEGER & CHERNOMAS, 2013). The artistic process is a valuable method of inquiry within research exploring the human condition because it encourages the researcher to embrace ambiguity (GILBERT et al., 2016); as one must do when investigating the vastness and complexities of experience. Although arts-based studies exist in health care research, few integrate the use of art throughout all stages of the inquiry. For example, the use of art often occurs in the stages of data collection and analysis and manifests through participants' creation of artwork in a number of arts-based research studies (GILBERT et al., 2016; LORENZ, 2011; WELLS, RITCHIE & McPHERSON, 2012). In these studies, participants' narrative accounts about the artwork and the artwork itself were interpreted through iterative discussions and thematic analyses. Unlike my study, these researchers did not use or create art as a means to make sense of the background literature, the study methodology, and the participants' stories and artwork. This significant omission was a missed opportunity to strengthen rigor and reflexivity, and to enrich the analysis because the arts engage a different way of knowing. Moreover, a researcher's involvement in creating art within the inquiry and documentation of this artistic process is scarce. Given that art is a means for individuals to reflect, respond to, and generate meanings surrounding an experience (LATHAM, 2014; McNIFF, 2007), a researcher's involvement in art making throughout the study is valuable and has the potential to move arts-based research forward. [6]

3. Engaging Art and Reflexivity

In my study, I engaged in sketching throughout each stage of the research as a way to foster reflexivity. A unique aspect of my arts-informed research was my involvement in creating art and the incorporation of art at the outset of my study. The artistic process enables emotions to flow and the subconscious to surface (LATHAM, 2014; NOY, 2013). Thus, the researcher must surrender to the inherent ambiguity within the artistic process in order to give way for emotional provocation and uninhibited responses to emerge (LATHAM, 2014). This authentic expression of one's inner world can help inform self-understanding and conjure insight (JACK, 2012; LATHAM, 2014). As such, I immersed myself in the creative and iterative process of self-expression, intuitive thinking, and meaning-making in developing my sketches (GILBERT et al., 2016; LATHAM, 2014). Others have used artistic media such as poetry and photography to achieve this insightful form of reflexivity during their research journeys (CARTER, LAPUM, LAVALLEE & SCHINDEL-MARTIN, 2014; LAPUM, 2008). [7]

Beginning with my own story, I reflected on the personal impetus for exploring women's experiences of intimate relationships and IBS and began to sketch. Like GILBERT et al. (2016), I recognized that the arts provided me with a vehicle to revisit and examine past memories. In this reflective state, I sketched a personally significant moment that I shared with my sister in her illness journey with IBS (see Illustration 1).

Illustration 1: "A shared moment" (NGUYEN, 2015, p.7) [8]

This sketch depicts the shared moment in which I developed a deeper sense of empathy and compassion for my sister's well-being and for others encountering IBS. Explicating reflexivity requires self-transparency—an act that commands the researcher to be raw, honest, and vulnerable (BERGER, 2015; CARTER et al., 2014; OSEI-KOFI, 2013). The act of sketching this image enabled me to connect with my inner self and relive the feelings I experienced in the shared moment with my sister. Like SALOM (2013), I found that sketching facilitated self-awareness. It was through this self-awareness in which I realized that my preconceived assumptions about gender led me to invalidate my sister's feelings of sadness and anxiety related to IBS. Ascribing to the gendered norm, which suggests that women are emotional, I dismissed my sister (who identifies herself as a female) as being overly sensitive about her experience of IBS. I felt vulnerable as I recalled my lack of empathy and sensitivity towards my sister during her earlier experience with IBS. It was difficult to openly face these memories and acknowledge past behavior that upon reflection, I now regret. The use of art as a tool for reflexivity assisted me in adopting and integrating a critical feminist perspective as it facilitated my self-awareness, thereby pushing me to consider my own taken-for-granted assumptions about gender. Engaging a critical feminist orientation to my research was crucial because it helped me become aware of "the social conditions that mediate and constitute individuals' experiences [and knowledge], and the social structures that lead to constraints of [thinking and] behavior" (NGUYEN, 2015, p.23), including my own. A deeper understanding of people's experiences and identities can be gained from a collective consideration of their social relationships and personal background. [9]

It is imperative to engage a reflexive account throughout the conduct of qualitative research due to the heavy involvement of interpretation (BERGER, 2015; CARTER et al., 2014), on the part of the researcher, who is considered a tool in the inquiry (RICHARDSON, 2000). Reflexivity is an ongoing process whereby the researcher locates and appraises her or his positionality within the inquiry. This active awareness enables the researcher to understand and explicate the potential impact of one's positioning on the collection, interpretation, and representation of research data (BERGER, 2015; LATHAM, 2014). The arts can be useful in facilitating reflexive processes because there is an intimate quality in creating and sharing personal artwork, in that one's emotions and deeply personal definitions are involved and shared (FOSTER, 2007; LAVALLEE, 2009; OSEI-KOFI, 2013). Echoing the work of OSEI-KOFI (2013), reflexive sketching enabled me to harness an alternative mode of knowing that deepened my journey of introspection, and understanding how I was situated in the research process. As I sketched, I took on a deeply introspective stance taking into account my own personal biases and my position as researcher in the study (NGUYEN, 2015). Like others (HENARE et al., 2003; KNOWLES & COLE, 2008; LORENZ, 2011), I found that the emotional processes triggered by creating art opened a portal through which I accessed and intimately connected with my innermost emotions. The arts can help preserve the epistemological integrity of the research and reinforce rigorous inquiry by providing a medium to facilitate reflexivity (LAPUM, 2008). Given the importance of engaging in reflexivity early on in and throughout the research process, and the value of art in facilitating reflexive thinking, future arts-based research can benefit from involving the arts in every stage of the inquiry. [10]

4. Using Art in Literature Syntheses

The use of art as a form of inquiry is underdeveloped in the domain of literature reviews and syntheses. However, given that the purpose of reviewing the literature is to critically synthesize multiple perspectives on an area of interest, engaging a different lens and way of knowing by purposefully integrating the arts is fitting. In my thesis, I reviewed research studies, theoretical literature, and literature reviews related to IBS, chronic illness, and intimate relationships and divided my literature synthesis into two sections: 1. IBS; and 2. intimate relationships and chronic illness (NGUYEN, 2015). I used the arts in the form of sketching my initial thoughts about and responses to what I was reading in the literature. I often find the extensive process of reviewing large volumes of literature can be overwhelming. However, similar to others (HUSS et al., 2015; SALOM, 2013), sketching assisted me in visually grouping together multiple ideas in organizing the literature synthesis. This visual unification supported a coherent rendition of the critical review. I was able to define themes as well as gaps within the literature more clearly using what HUSS et al., characterize as visual skills. Furthermore, similar to LAPUM et al. (2012), I recognized that my engagement with the arts in reviewing the literature forced me to reject previously learned research processes. This unlearning was fueled by the originality of art-making and its lack of rigid structure (EALES & PEERS, 2016). While sketching, I contemplated how to translate my cognitive understanding of the literature into images. This thought process propelled me to continually pause and think deeply about the literature, which supported my focus and critical eye. Given that the research used a critical feminist lens to understand the women's experiences with IBS, the solicitation of purposeful thinking was invaluable to my review of the literature. In line with a critical feminist perspective, sketching helped to heighten my awareness of taken-for-granted knowledge and exposed me to a clearer understanding of the social processes and culturally specific meanings that shape language (SCOTT, 1987), and thus literature. [11]

Illustrations 2 and 3 depict the sketches I developed in response to reviewing and making sense of the literature.

Illustration 2: "Stigmatized, disrupted" (NGUYEN, 2015, p.33)

Illustration 3: "Interlocking hands" (p.42) [12]

While reviewing the literature on IBS and chronic illness and intimate relationships, I reflected on my thought processes while reflexively sketching:

"I felt moved by participants' experiences of actual or perceived stigmatization, and their feelings that their bodies were disruptive to their everyday lives. I tried to put myself in their position to understand how they felt and sketched an illustration to capture the themes of stigma and disruption … The drawing depicts a focus on the stomach in an irritable state to represent the disruptiveness of IBS. The shadowed figures and question marks convey the potential for women diagnosed with IBS to experience perceived or actual stigmatization" (p.32). [13]

In reviewing the visual representation of the theme of disruption and stigma (see Illustration 2), what was missing from the image raised my attention to the gap in IBS literature regarding intimate relationships. While previous IBS research revealed that individuals experience stigma and perceive their body as disruptive in social contexts, what was noticeably absent from the literature and consequently, my sketch is the way individuals experience IBS in the context of intimate relationships. Illustration 3 exhibits a prominent theme found in the literature on intimate relationships and chronic illness regarding how chronic illness affects both partners in an intimate relationship. I gained insight into the way that intimate partners' support facilitates adjustment to the illness and fosters intimate relationship development. As such, I sketched an illustration of interlocking hands to show the significance of individuals' intimate relationships during the experience of chronic illness. Mirroring a gap in the IBS research, my sketch also does not provide insight into the shared journey of IBS in intimate relationships and how such partnerships are experienced while living with this disorder. My sketches emphasize the importance of support and the shared nature of living with chronic illness in intimate relationships. The absence of these aspects from my sketch with specificity to IBS drew my attention to this gap in the literature. These visual syntheses of the IBS literature helped me to see recurring themes as well as facilitated my recognition of knowledge gaps through what was missing in the images. [14]

Art can play a valuable role in critically reviewing the literature because its symbolic language can introduce different viewpoints, and thus, shed light on what might have been overlooked (LATHAM, 2014; RIEGER & CHERNOMAS, 2013). Furthermore, the intentionality present in the process of creating art can allow researchers to dwell on the literature as it elicits reflection and draws attention to fine details (LATHAM, 2014). Engaging emotive processes and sensory knowing through the arts can help researchers comprehensively and critically deconstruct the literature, thereby enriching and advancing insight (LATHAM, 2014; OSEI-KOFI, 2013). [15]

5. Using Art in Theory and Methodology

The complexity of art calls for multiple ways of knowing, which can support individuals in deconstructing abstract concepts (NGUYEN, MIRANDA, LAPUM & DONALD, 2016; OSEI-KOFI, 2013; RIEGER & CHERNOMAS, 2013) and provide a means for understanding a kind of knowledge that words might not always sufficiently convey (HENARE et al., 2003; KNOWLES & COLE, 2008). Furthermore, its evocative quality can facilitate vicarious experiences that enable others to come close to people's situations. Such qualities support the development of empathetic knowing, which is invaluable for enabling researchers to learn about people's experiences (KNOWLES & COLE, 2008) and fostering emotional competence (LAPUM, HAMZAVI et al., 2011). [16]

As such, I drew upon the power of creating art to support the rigorous employment of the methodological approach (narrative inquiry) and theoretical lens (critical feminist theory) in my study. In doing so, I discovered that a complimentary fit transpired between the artistic process and the narrative inquiry underpinned by critical feminist theory. The abstract quality and extensiveness of research methodologies and theories can often be overwhelming to grasp. As such, I utilized the symbolism of art and its capacity to comprehensively amalgamate a plethora of feelings, ideas, and concepts into a single image (HUSS et al., 2015) to visually define narrative inquiry and critical feminist theory (see Illustration 4 and 5).

Illustration 4: "The magnifying glass" (NGUYEN, 2015, p.23)

Illustration 5: "The unraveling script" (p.52) [17]

Creating art to make sense of an arts-informed methodology and theoretical lens was a novel approach to using art in health care research that supported my understanding and subsequently, rigorous employment of narrative inquiry and critical feminist theory. [18]

I reflected as I sketched Illustration 4:

"I compared the lens of critical feminism to a magnifying glass because they both act as an aid to help individuals examine things closely and purposefully. Under the magnifying glass, I drew symbols to represent [concepts/constructs that] I closely and critically examined using this theoretical lens, which are gender, social, historical, and political processes" p.23). [19]

Critical feminism sheds light on how gendered and social norms, and historical and political processes are embodied in a way that shapes individuals' sense of their identity, their experiences, and their situatedness in the world (PITRE, KUSHNER, RAINE & HEGADOREN, 2013; SCOTT, 1999). The standard gender signs were used to symbolize gendered processes while the collection of figures symbolized people and their social context/processes. The tree was used to represent historical processes, as tree roots are reminiscent of history. The scale portrayed the balance and dynamics of power that occur within social relations and was used to symbolize political processes. With regard to Illustration 5, I sketched an unraveling script to emphasize the way an account is shared through its content and form. The content of stories is symbolized through the scriptures themselves while the script's unfolding represented how stories take on different forms. I included a chalk overlay filter to the drawing because "a chalk drawing can represent childhood and therefore, seemed appropriate for conveying how storytelling is a familiar method of communication shared by all humans often from a young age" (NGUYEN, 2015, p.52). [20]

I was able to solidify my understanding of abstract concepts by exercising an aesthetic mode of knowledge consolidation while choosing, articulating, and implementing theory and methodology in my study. This understanding was imperative to my critical exploration of the holistic content and form of women's narratives. In line with a critical feminist perspective, it was crucial to approach the inquiry in a way that fostered unmediated self-expression amongst participants and addressed the value-laden nature of language (SCOTT, 1987). The issue with using narratives alone is that language is laden with meanings that are inextricably tied to and shaped by culture, history, and social context (NGUYEN, 2015). Similar to LORENZ (2011), I found that the original and personal quality of art lent itself to supporting emotional and subjective expression. I question whether language alone has the same capabilities. The unique and personal quality of art was invaluable for supporting a critical feminist approach to the research because it addressed the potential limitations of language and encouraged authentic self-expression. The generic nature and linearity of written words often cannot adequately capture the depth and quality of emotions and experiences whereas art can allow for a very personalized representation of one's inner world (EALES & PEERS, 2016; FOSTER, 2007; JACK, 2012). [21]

6. Using Art in Data Collection Methods

I included an arts-informed activity as a means to stimulate storytelling akin to the way that photo-elicitation is utilized to promote deep discussion during research interviews (TORRE & MURPHY, 2015). In line with the core principles of photo-elicitation, the participants' artistic expressions were used as a tool to facilitate reflection during interviews and help the women interpret their experiences as opposed to acting as an object for analysis (ANGUS et al., 2009). However, I did not want to place restrictions on what forms of art participants could engage in within this study. My rationale for providing participants with the flexibility to engage in various art forms of their choosing was to enable their voices to come through in the research. Participants used various art forms to convey their experiences such as photographic images, stories, paintings, and poetry. The freedom to choose different artistic media allowed participants to use art forms that best supported their ability to communicate their personal stories. [22]

The inclusion of an arts-informed activity stimulated reflection and the development of a fulsome dialogue between participants and myself as the researcher (. Echoing previous work (LORDLY, 2014), the artistic creation process enabled participants to gain epiphanies and fresh insight on former experiences and feelings that some had not been previously aware of before participating in the aesthetic activity. "Participants' engagement in creating and discussing their art pieces produced rich descriptions of their experiences, which contributed to meaningful analytic interpretations and representation of their narratives" (NGUYEN, 2015, pp.141-142). [23]

One of the participants (pseudonym Sun) created a short vignette and also brought a photographic image that her husband took of her abdomen (see Illustration 6).

Illustration 6: "Bloated" (NGUYEN, 2015, p.73) [24]

The focus of the vignette was an interaction between Sun and her husband during her experience of bloating related to IBS. The richness of description and storytelling in Sun's vignette enabled me to vividly imagine what she was feeling in that moment and visualize the characters' interaction. Prior to reading her vignette, I had not considered the emotional magnitude of bloating in one's experience of intimate relationships and IBS. However, the imaginative quality of her vignette facilitated my ability to picture the moment, understand, and appreciate her personal experience. [25]

A second participant (pseudonym Michelle) created a painting (see Illustration 7), which portrayed her concealment of IBS during intimate relationships and the inner turmoil she experienced.

Illustration 7: "The painting" (p.93) [26]

Michelle explained the layers of her painting, articulating that the swirling and messy colors at the base represented her stomach and the inner turmoil she experienced in relation to living with IBS during her intimate relationships. The green at the top of the painting represented her metaphorical shield and her attempt to hide her IBS from intimate partners. Michelle explained that she intuitively painted in response to her feelings. Although abstract, I felt the emotion in her brush strokes and choice of colors. Listening to Michelle's story while viewing her painting was an emotional experience for me because the symbolism was graphic and striking. Furthermore, Michelle shared that she experienced a revelation about her feelings in creating the artistic piece, one that she was not aware of before doing the activity. The strong emotion communicated in Michelle's painting enabled me to understand her experience on an affective level. The engagement of affective thinking deepened my insight into the research question. [27]

A third participant (pseudonym Lisa) composed a poem (see Illustration 8).

Illustration 8: "The hidden teacher" (p.110). Click here to download the PDF file. [28]

The poem portrays Lisa's transformative healing journey in which she reconciles the fear and pain she experienced with a personal practice of self-compassion and love. Her emotionally charged poem triggered a visceral response within me. I was deeply moved by the vicarious experience of emotion that her poetry enabled. The emotional connection I felt to her poetry facilitated my capacity to deeply understand her story. Furthermore, Lisa's artistic piece helped me understand the significant turning point within her narrative in which she reconstitutes the meaning of her experience with intimate relationships and IBS. Her poetry provided me with insight and emotional understandings that might not have occurred if the artistic activity had been omitted. [29]

Creating and sharing art is done on a personal level, which helps to maintain authenticity and preserve a humanistic approach to inquiry (LORDLY, 2014; OSEI-KOFI, 2013). Furthermore, the act of sharing one's self-expression through art can create a starting point from which individuals can open up and deeply connect with one another (LORDLY, 2014). This personal level of sharing facilitates trust, which is particularly crucial in research exploring sensitive and taboo topics such as intimate relationships and IBS. Forms of art such as poetry can provide a haven in which individuals can safely engage in self-introspection (LAPUM, HAMZAVI, et al., 2011). Similar to other studies (LORDLY, 2014; WELLS et al., 2012), I found that "the incorporation of an arts-informed activity provided an opening into a sensitive topic and the opportunity for … [the] women to lead the discussion with what was most important to them" (NGUYEN, 2015, p.149). The arts also reinforced a rigorous methodological and theoretical approach by helping to ensure that women's stories were explored in a way that honored their highly personalized experiences and inner world. Furthermore, the artistic process helped to elucidate the phenomenon of human experience in an authentic and contextualized way. [30]

7. Using Art in Findings and Interpretation

What I found was that the arts were a useful tool that deepened and enhanced my own analytic interpretations (FOSTER, 2007). While previous arts-based studies in health care research have involved participants in creating artwork that was subsequently analyzed, my research was unique in that I, the researcher, also engaged in creating artwork and utilized it as a method for understanding participants' art pieces. Creating art allowed me to fully and actively engage with the research by allowing my identities as researcher and artist collectively to inform meaning making in my analysis (SPRINGGAY et al., 2008). Not only did participants' artwork enrich my understanding of their narratives, my own participation in creating art to interpret the data deepened my analysis by promoting reflection and emotional awareness, and by calling upon a different way of thinking about women's stories. Indeed, the mergence of art and text in my analysis broadened my capacity to think creatively and imaginatively—a disposition to meaning making that might have been constrained by dominant discourse (LEAVY, 2012). Additionally, a comprehensive representation of the analysis is possible because the arts can articulate the emotional and visceral quality of human experience that traditional research methods often lack (EALES & PEERS, 2016). My engagement as a co-creator of art in my study revealed a possible way to advance arts-based methodology in healthcare research by including the utilization of art as a tool for analysis in addition to its existing use as medium for data collection. [31]

In my study, the arts unexpectedly became "deeply integral to meaning making and analysis" (NGUYEN, 2015, p.153). I systematically drew as I moved through the analytic phase. Illustrations 9, 10, and 11 highlight my analytic interpretations of the women's narratives.

Illustration 9: "Concealment" (p.95)

Illustration 10: "A transformative lesson" (p.114)

Illustration 11: "Complex emotional labor" (p.128) [32]

Like LEAVY (2012), the critical feminist stance I took on in my research was an effort to expose how dominant ways of thinking shape knowledge and experience. The use of art in research can reveal the prevailing social ideologies and behaviors that have been taken up as natural by inviting the researcher to question her or his assumptions. For example, the artistic process assisted my critical feminist interpretation of the women's accounts because of the critical and reflective thinking that the arts engaged. Participating in the artistic process facilitated my capacity to critically reflect upon and make sense of the women's narratives because I "considered the salience and rationale behind every pencil stroke and color choice I made in terms of their stories" (NGUYEN, 2015, p.143). This critical and reflective thinking is understood as the deliberate contemplation that occurs in creating art within arts-based research (SALOM, 2013). Such critical and reflective thinking is vital in interpreting and presenting research findings because decision-making and rationale are foundational to the study's rigor (BERGER, 2015). Akin to GUNARATNAM (2007), the personalized and intricate nature of art deterred me from dabbling into making assumptions and generalizing participants' experiences. Similar to GUNARATNAM, I also found that unlike words, the uniqueness, elusiveness, and ambiguity of the arts shifted me away from ordering and categorization and instead, into deep thinking. Furthermore, like LATHAM (2014), the subjectivity inherent in personal art helped me gain a contextualized understanding and thus capture the uniqueness of people's experiences. Echoing GUNARATNAM's work (2007), I found that the creative functioning facilitated by the arts helped me delve into the depths of the internal and external world that the limitations of cognitive thinking often cannot breach. The use of art in analysis can support rigor by adding another layer to interpretation through its solicitation of creative and intuitive thinking (LATHAM, 2014) along with sensory knowing (OSEI-KOFI, 2013). [33]

In line with previous work (VESSEL, STARR & RUBIN, 2013), I found participants' artistic pieces to be highly personal—this led me to feel an intimate connection with participants' artistic pieces, which enabled resonance with and deep understanding of their unique stories. The creation of art can be viewed as a reaction to an experience and thus, a way to make sense of it (GUNARATNAM, 2007). Employing the arts in the process of interpretation can aid the researcher in gaining an empathetic understanding of participants' stories as the tone of artwork (their inner world) can be felt (ARNOLD, MEGGS & GREER, 2014; JACK, 2012). The employment of art in research is not about the quality of the final product but rather, the emotions and vulnerability inherent in the artistic process that connects people and humanizes the research (GUNARATNAM, 2007). Sketching different images helped me make sense of, bring together, and present the results in a way that preserved the uniqueness and multifaceted complexity of participants' experiences. [34]

Following reflection of Michelle's narrative, I created a visual representation of concealment, which was central to her story (see Illustration 9). It was crucial to convey her feelings of confinement and inner turmoil, as it was important to her experience of concealment. Corroborating the work of SALOM (2013) on image making in arts-based inquiry, my movements in the process of sketching were made in response to the feelings and sensations that viewing her painting provoked within me. Engaging in this process enabled me to deepen my analysis by integrating sensory knowing. The harmony between body and mind facilitated through sketching in response to emotional and sensory provocation is characterized by SALOM as contemplative action. Like SALOM, I found that engaging in the contemplative process of creating art facilitated my emotional awareness, which was helpful in analyzing Michelle's emotionally charged art piece. I sketched Michelle as a robot to reflect her self-comparison of living robotically, which highlighted her challenge of developing an emotional connection to intimate partners. I continued to reflect as I sketched my response to Michelle's art piece:

"Within the abdominal area of the robot, I sketched a drawing of Michelle crouched into a ball behind black drapes. I chose this positioning to convey a sense of isolation and disconnectedness from the outer world. The black drapes were drawn closed to represent how she felt enclosed, and the concealment of her inner turmoil. I felt that a dark color for the curtains was appropriate as it conveys concealment or something that is difficult to see, akin to the lack of light at night. I colored the sketch of Michelle using the same colors as she did to represent her inner turmoil within the painting she created (yellow, dark red, brown, and black). I depicted a smile on the robot to convey Michelle's effort to conceal her inner turmoil from intimate partners. [To represent Michelle's attempt to remain composed during her relationships], I colored the robot green because it is a cool tone that can convey a sense of calmness. A hand, which represents Michelle's intimate partners, holds the robot's hand and extends off the page. The anonymity of the intimate partners symbolizes Michelle's lack of focus on her previous intimate relationships as she prominently focused on her IBS and inner emotions" (NGUYEN, 2015, p.96). [35]

Using Lisa's account in which growth and learning were central, I created a sketch that portrayed the transformative lesson she underwent during her experience (see Illustration 10). Drawing on the capability of art to provoke emotion through colors in particular (SALOM, 2013), I utilized color to help me interpret the emotional tone of Lisa's story and art piece. In so doing, I portrayed Lisa as though she were rising to symbolize the transcendent quality of her growth that she experienced in retrospect. Although a yellow glow surrounds her in the sketch, a grey darkness is depicted on the outside perimeter. The contrast between the light yellow and dark grey "symbolizes the transformation in her perception of the experience (from demon to teacher) and the change from fear to self-compassion" (NGUYEN, 2015, p.115). I continued to reflect as I sketched:

"I also chose to depict darkness on the outside perimeter of the glow that surrounds Lisa to represent the ongoing conscious practice of self-compassion to address her fears and pain. I depicted Lisa embracing herself and chose to color the center of her chest in red-orange tones in the shape of a heart to symbolize warmth and convey self-compassion" (ibid.). [36]

In dwelling on the three women's stories, I focused my next sketch on the theme of complex emotional experiences that seemed to stand out from their accounts. Creating a metaphorical representation of the women's experiences was made possible through the visual thinking that the arts facilitate (SALOM, 2013). In the following passage, I deconstruct the meaning of my artistic response:

"The drawing features multiple turning gears enclosed inside a heart. The heart symbolizes the emotional experiences. The abundant turning gears convey the emotional labor involved in women's experiences of intimate relationships. The various colors weaving through and around the gears represent the myriad of emotions the women felt and managed. The picture's aesthetically complex nature mirrors the complexity of participants' emotional experiences" (NGUYEN, 2015, p.128). [37]

Art can play a powerful role in the dissemination of study findings because it can provide a boundless medium for self-expression and allow participants' voices to be heard, thus moving the personal to a political level (FOSTER, 2007; HENARE et al., 2003). Literary forms of dissemination alone may be less apt for representing participants in a holistic way because words are limiting (BARRY, 2017). The use of art to present study findings honors and preserves the uniqueness and personal quality of participants' stories and can thereby support authentic representation. For example, fashion shows can preserve personhood in knowledge dissemination by making it possible for participants to partake in and co-construct the way findings are shared through the freedom with which they are able to represent self via clothing and performance (ibid.). Moreover, art's capacity to communicate emotion could be harnessed in the dissemination of study findings to support the accessibility of knowledge to lay audiences (LEDGER & McCAFFREY, 2015) because unlike verbal means of communication, emotion is a universal language. Artistic modes of dissemination encourage the application of an emotional lens for understanding that disrupts traditional ways of thinking (LAPUM et al., 2012). Because art can provide a means for audiences to vicariously experience the lives of others (KNOWLES & COLE, 2008), it is an invaluable tool for understanding that could be utilized in the dissemination of study findings. I have carried on the integration of art from inquiry to dissemination by including images of the art from my IBS research in the development of this manuscript and conference presentations. I included the images in the sections to which they correspond to provide a visual representation in addition to the literary rendition of my work. In continuing to work with the arts in future research, it is my intention to explore other potential avenues of arts-based dissemination such as installation art, theater, film, and fashion shows to make research findings more accessible to wider audiences. [38]

I embarked upon an artistic inquiry as I interwove the arts throughout my research to explore women's narratives of intimate relationships while living with IBS. Through this journey, I gained insight into the creative and rigorous use of art in research. I discovered that the arts can bring forth a type of knowing that caters to unspeakable human emotions (KNOWLES & COLE, 2008) and can portray the artist's personal thoughts and feelings without the use of words (EALES & PEERS, 2016; FOSTER, 2007; JACK, 2012). The arts' integration of different types of knowledge adds depth and dimension to the researcher's lens of interpretation (LATHAM, 2014; OSEI-KOFI, 2013). However, as LATHAM (2014) remarked, embracing creative functioning through the arts necessitates a letting go of conventional ways of pursuing knowledge. Although the arts enriched my research, its obscurity and the multi-modal methods of knowing it calls for, made the process challenging. However, in line with previous work (EALES & PEERS, 2016; GILBERT et al., 2016), it is this complexity that pushed me into deep and critical thinking thereby reinforcing the study's rigor. Therefore, it might be valuable to explore the engagement of the researcher as a co-creator of art in future research involving arts-based methods. Because of the value that art added to every stage of the research in my study, exploration of the systematic integration of art throughout the inquiry potentially holds merit in future research regarding arts-based methodology. Furthermore, further research with respect to audiences' and stakeholders' perceptions of artistic modes of dissemination would provide valuable insight into the capacity of art to disseminate findings and translate knowledge as little has been documented in this domain. Other disciplines oriented towards understanding human experiences and emotions could benefit from the employment of arts-based research methods. Therefore, discipline- and context-specific investigations of using arts-based research are worth exploring. Given that so much of the human experience is imbued with emotion, uncertainty, and complexity, it would be counter intuitive to omit research methods, such as the arts, that mobilize different ways of thinking and invite the unknown. [39]

I would like to thank my thesis supervisor, Dr. Jennifer LAPUM, and committee members, Dr. Margaret MALONE and Dr. Annette BAILEY for their invaluable support and guidance. The completion of my Master's study and the development of the ideas that were key to this manuscript would not have been possible without your creative and expert insights. I am immensely grateful for your ongoing encouragement and support.

Angus, Jan E.; Rukholm, Ellen; Michel, Isabelle; Larocque, Sylvie; Seto, Lisa; Lapum, Jennifer; Timmermans, Katherine; Chevrier-Lamoureux, Renee & Nolan, Robert P. (2009). Context and cardiovascular risk modification in two regions of Ontario, Canada: A photo elicitation study. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 6(9), 2481-2499, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19826558 [Accessed: April 18, 2017].

Arnold, Alice; Meggs, Susan M. & Greer, Annette G. (2014). Empathy and aesthetic experience in the art museum. International Journal of Education Through Art, 10(3), 331-347.

Barry, Ben (2017). Enclothed knowledge: The fashion show as a method of dissemination in arts-informed research. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung / Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 18(3), Art. 2, http://dx.doi.org/10.17169/fqs-18.3.2837 [Accessed: February 27, 2018].

Berger, Roni (2015). Now I see it, now I don't: Researcher's position and reflexivity in qualitative research. Qualitative Research, 15(2), 219-234.

Boydell, Katherine (2011). Using performative art to communicate research: Dancing experiences of psychosis. Canadian Theatre Review, 146(1), 12-17.

Capous-Desyllas, Moshoula C. (2013). Representation of sex workers' needs and aspirations: A case for arts-based research. Sexualities, 16(7), 772-787.

Carter, Celina; Lapum, Jennifer L.; Lavallee, Lynn F. & Schindel Martin, Lori (2014). Explicating positionality: A journal of dialogical and reflexive storytelling. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 13, 362-376, http://journals.sagepub.com/doi/full/10.1177/160940691401300118 [Accessed: April 18, 2017].

Eales, Lindsay & Peers, Danielle (2016). Moving adapted physical activity: The possibilities of arts-based research. Quest, 68(1), 55-68.

Foster, Victoria (2007). Ways of knowing and showing: Imagination and representation in feminist participatory social research. Journal of Social Work Practice, 21(3), 361-376.

Gilbert, Mark A.; Lydiatt, William M.; Aita, Virginia A.; Robbins, Regina E.; McNeilly, Dennis P. & Desmarais, Michele M. (2016). Portrait of a process: Arts-based research in a head and neck cancer clinic. Medical Humanities, 42(1), 57-62.

Gunaratnam, Yasmin (2007). Where is the love? Art, aesthetics and research. Journal of Social Work Practice, 21(3), 271-287.

Henare, Diane; Hocking, Clare & Smythe, Liz (2003). Chronic pain: Gaining understanding through the use of art. British Journal of Occupational Therapy, 66(11), 511-518.

Hodgins, Michael & Boydell, Katherine M. (2014). Interrogating ourselves: Reflections on arts-based health research. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung / Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 15(1), Art. 10, http://dx.doi.org/10.17169/fqs-15.1.2018 [Accessed: April 18, 2017].

Hooks, Bell (1995). Art on my mind: Visual politics. New York: New Press.

Huss, Ephrat; Kaufman, Roni; Avgar, Amos & Shouker, Eytan (2015). Using arts-based research to help visualize community intervention in international aid. International Social Work, 58(5), 673-688.

Jack, Kirsten (2012). "Putting the words 'I am sad', just doesn't quite cut it sometimes": The use of art to promote emotional awareness in nursing students. Nurse Education Today, 32(7), 811-816.

Klorer, Gussie P. (2014). My story, your story, our stories: A community arts-based research project. Art Therapy: Journal of the American Art Therapy Association, 31(4), 146-154.

Knowles, Gary J. & Cole, Ardra L. (Eds.) (2008). Handbook of arts in qualitative research: Perspectives, methodologies, examples, and issues. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Lapum, Jennifer (2008). The performative manifestation of a researcher's identity: Storying the journey through poetry. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung / Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 9(2), Art. 39, http://dx.doi.org/10.17169/fqs-9.2.397 [Accessed: April 18, 2017].

Lapum, Jennifer; Yau, Terrence & Church, Kathryn (2015). Arts-based research: Patient experiences of discharge. British Journal of Cardiac Nursing, 10(2), 80-84.

Lapum, Jennifer; Ruttonsha, Perin; Church, Kathryn; Yau, Terrence & Matthews David, Alison (2012). Employing the arts in research as an analytical tool and dissemination method: Interpreting experience through the aesthetic. Qualitative Inquiry, 18(1), 100-115.

Lapum, Jennifer; Hamzavi, Neda; Veljkovic, Katarina; Mohamed, Zubaida; Pettinato, Adriana; Silver, Sarabeth & Taylor, Elizabeth (2011). A performative and poetical narrative of critical social theory in nursing education: An ending and threshold of justice. Nursing Philosophy, 13(1), 27-45.

Latham, Soosan D. (2014). Leadership research: An arts-informed perspective. Journal of Management Inquiry, 23(2), 123-132.

Lavallee, Lynn F. (2009). Practical application of an indigenous research framework and two qualitative indigenous research methods: Sharing circles and Anishnaabe symbol-based reflection. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 8(1), 21-40, http://journals.sagepub.com/doi/full/10.1177/160940690900800103 [Accessed: April 18, 2017].

Leavy, Patricia (2012). Introduction to visual arts research special on a/r/tography. Visual Arts Research, 38(2), 6-10.

Leavy, Patricia (2015). Method meets art. London: The Guilford Press.

Ledger, Alison & McCaffrey, Triona. (2015). Performative, arts-based, or arts-informed? Reflections on the development of arts-based research in music therapy. Journal of Music Therapy, 52(4), 441-456.

Lordly, Daphne (2014). Crafting meaning: Arts-informed dietetics education. Canadian Journal of Dietetic Research and Practice, 75(2), 89-94.

Lorenz, Laura S. (2011). A way into empathy: A "case" of photo-elicitation in illness research. Health, 15(3), 259-275.

MacDonnell, Judith A. & MacDonald, Geraldine J. (2011). Arts-based critical inquiry in nursing and interdisciplinary professional education: Guided imagery, images, narratives, and poetry. Journal of Transformative Education, 9(4), 203-221.

McNiff, Shaun (2007). Arts-based research, https://www.uni-mozarteum.at/files/pdf/fofoe/ff_abr.pdf [Accessed: April 18, 2017].

McNiff, Shaun (2011). Artistic expressions as primary modes of inquiry. British Journal of Guidance and Counselling, 39(5), 385-396.

Nguyen, Megan (2015). Women's experiences of intimate relationships while living with irritable bowel syndrome. Unpublished master's thesis, Ryerson University, Toronto, Ontario, Canada.

Nguyen, Megan; Miranda, Joyal; Lapum, Jennifer & Donald, Faith (2016). Arts-based learning: A new approach to nursing education using andragogy. Journal of Nursing Education, 55(7), 407-410.

Noy, Pinchas (2013). A theory of art and aesthetic experience. Psychoanalytic Review, 100(4), 559-582.

Osei-Kofi, Nana (2013). The emancipatory potential of arts-based research for social justice. Equity and Excellence in Education, 46(1), 135-149.

Pitre, Nicole Y.; Kushner, Kaysi E.; Raine, Kim D. & Hegadoren, Kathy M. (2013). Critical feminist narrative inquiry: Advancing knowledge through double-hermeneutic narrative analysis. Advances in Nursing Science, 36(2), 118-132.

Richardson, Laurel (2000). Writing: A method of inquiry. In Norman K. Denzin & Yvonna S. Lincoln (Eds.), Handbook of qualitative research (pp.923-948). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Rieger, Kendra L. & Chernomas, Wanda M. (2013). Arts-based learning: Analysis of the concept for nursing education. International Journal of Nursing Education Scholarship, 10(1), 1-10.

Salom, Andree (2013). Art therapy and its contemplative nature: Unifying aspects of image making. Art Therapy: Journal of the American Art Therapy Association, 30(4), 142-150.

Scott, Joan W. (1987). On language, gender, and working-class history. International Labor and Working Class History, 31(31), 1-13.

Scott, Joan W. (1999). Gender and the politics of history, http://hdl.handle.net/2027/heb.00103.0001.001 [Accessed: April 18, 2017].

Springgay, Stephanie; Irwin, Rita L.; Leggo, Carl & Gouzouasis, Peter (Eds.) (2008). Being with a/r/tography. Rotterdam: Sense Publishers.

Torre, Daniela & Murphy, Joseph (2015). A different lens: Using photo-elicitation interviews in education research. Education Policy Analysis Archives, 23(110-111), 1-23, https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ1084022.pdf [Accessed: April 18, 2017].

Vessel, Edward A.; Starr, Gabrielle G. & Rubin, Nava (2013). Art reaches within: Aesthetic experience, the self and the default mode network. Frontiers in Neuroscience, 7(258), 1-9, https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fnins.2013.00258/full [Accessed: April 18, 2017].

Wells, Francesca; Ritchie, Dawn & McPherson, Amy C. (2012). "It is life threatening but I don't mind": A qualitative study using photo elicitation interviews to explore adolescents' experiences of renal replacement therapies. Child: Care, Health and Development, 39(4), 602-612.

Megan NGUYEN is a research assistant at the Women's College Hospital Research Institute for Health System Solutions and Virtual Care and is a PhD student in the Department of Public Health at the University of Toronto. She holds a master of nursing degree from the Daphne Cockwell School of Nursing at Ryerson University (2015). Her main research interests are within the arena of critical qualitative research and supportive care in cancer.

Contact:

Megan Nguyen

Women's College Hospital

Institute for Health System Solutions and Virtual Care

76 Grenville St, Toronto, ON M5S 1B2

E-mail: megan.nguyen@mail.utoronto.ca

Nguyen, Megan (2018). The Creative and Rigorous Use of Art in Health Care Research [39 paragraphs]. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung / Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 19(2), Art. 39, http://dx.doi.org/10.17169/fqs-19.2.2844.