Volume 8, No. 3, Art. 9 – September 2007

Drugwatch: Establishing the Practicality and Feasibility of Using Key Professionals and Illicit Drug Users to Identify Emerging Drug Tendencies

Mark Mason, Oswin Baker & Rebecca Hardy

Abstract: The updated United Kingdom Anti-Drugs strategy highlights gaps in the current body of drug related knowledge. Although work has been addressing these gaps for a number of years now, it has proven challenging to establish the dynamics of emerging drug tendencies within local areas. Some work of this nature has been carried out within the UK, but these studies have been beset by problems. With this in mind the Drugs Analysis and Research Programme and Market and Opinion Research International (MORI) embarked on developmental work to assess whether a national project, involving progressive sweeps of interviews with key professionals and drug users, in ten areas of England and Wales, would help fill these gaps still further. Findings suggested that the overall process worked very well. Not only did the project prove feasible, but interviews were felt to have produced real time, policy relevant information. However, it was felt that the project was often resource hungry.

Key words: drug trends, early warning systems, monitoring, key individuals, drug use

Table of Contents

1. Background

1.1 Existing work in this area

1.2 Previous work in England and Wales

1.3 The development and aim of Drugwatch

2. Developing the Methodology

2.1 Interviews with key professionals

2.2 Interviews with illicit drug users

2.3 Research sites

2.4 Purposive sampling

2.5 Issues to be explored

2.6 The final model

3. Implementing the Model: First Sweep

3.1 The research team

3.2 Topic guides and interview methodology

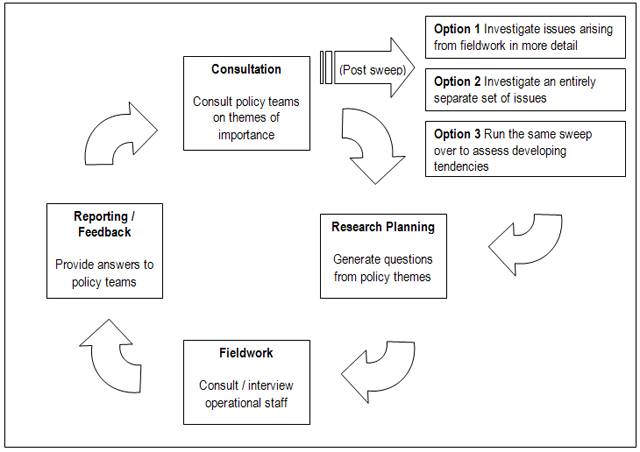

3.3 Data management

3.4 Generating interviews

3.5 Interviews with illicit drug users

3.6 Training the research team

3.7 Planning and conducting the interviews

4. Implementing the Model: Second Sweep

4.1 The research team and the topic guides

4.2 The adapted methodology: Interviews with key professional

4.3 The adapted methodology: Interviews with illicit drug users

5. Findings

6. Conclusions and Implications

6.1 Spotting tendencies

6.2 Resourcing and implications for the future

The updated United Kingdom Anti-Drugs strategy highlights the fact that there are knowledge gaps in the routes and methods used to supply illegal drug markets, and in the general dynamics of drug markets. This includes the need to understand the whole of the supply chain from importation, to sale at street level, the impact that this has on communities, the resulting demand for treatment within them, and an understanding of how new and emerging tendencies within these issues develop and spread. [1]

Although work has been addressing these knowledge gaps for a number of years now, it has proven challenging to establish the nature of the national drug situation and the dynamics of drug tendencies on a consistent, systematic basis within local areas across the country, in any amount of depth or detail. It is notably more difficult again to determine how local conditions shape the national picture. While a number of studies have been carried out to explore drug markets, these have inevitably individual localised snapshots, limited by time and geographical location for example MAY, HAROCOPOS, TURNBULL and HOUGH (2000). [2]

With this in mind it was decided that a more systematic approach, providing important contextual information as to how the National drug strategy was being implemented in local areas should be developed. To get at this information it was decided that a useful approach might be to interview service providers (hereafter known as Key Professionals or KPs) and service users in a number of sites across the country. [3]

The feeling was that KPs held a wealth of information that, when taken together, might provide a comprehensive snapshot of drug use patterns in communities across the country. Further, these individuals offered expertise that might alert policy makers to any short term changes or newly emerging problems concerning specific drugs, drug users and those susceptible to drug use. [4]

1.1 Existing work in this area

The more scoping work that was done, the more it became clear that (KP) interviews are a validated method of providing intelligence on emerging local issues. There are already a number of annual perceptual studies of the drug situation that are carried out in other countries. [5]

"Pulse Check" (Office of National Drug Control Policy [ONDCP], 2004) in the USA aims to describe local issues concerned with drug misuse and drug markets. It looks specifically at drug misusing populations, emerging drugs, new routes of administration, varying patterns, changing demand for treatment, drug-related criminal activity and shifts in supply and distribution patterns through telephone interviews with KPs at 21 sites across the United States. Respondents are asked about their perceptions of change in the drug situation. The study aims to interview the same respondents, or at least the same agencies, for consecutive sweeps of the survey. [6]

The collaborative European "Tendances Recentes Et Nouvelles Drogues" or TREND project (ALVAREZ et al., 2003) is aimed at identifying and describing emerging tendencies in relation to the illicit drug situation in France. This study also uses the KP approach to describe these patterns. Interviews are carried out with drug treatment workers and other healthcare professionals such as General Practitioners. TREND has the flexibility to focus on an emerging issue of concern, which might have been identified from a previous study. Previous issues have included the increased use of Rohypnol, the dance music scene and drug taking among skilled, young professionals. [7]

In Australia the "Illicit Drug Reporting System", IDRS (DARKE, TOPP & KAYE, 2001), utilises a qualitative KP survey as a monitoring component. The survey asks questions about the price, purity, availability and patterns of use of the four main, illicit drug types, classified as Class A by the UK Government: Heroin, Crack, Powder Cocaine and Ecstasy. It also acts as an early warning system for emerging tendencies in illegal drug markets. To set it apart from other studies other data sources are used in triangulation for the IDRS including an examination of existing indicators of drug use (e.g. arrest and seizure data). The IDRS is run at a number of sites annually throughout Australia, to provide the accurate information on which sound policy decisions must ultimately rest1). [8]

These studies should by no means be regarded as an exhaustive list of the canon of work relevant to this area. At a regional or city or town level, a number of projects have attempted to provide regular and timely feedback about local drug problems. Some of the more notable examples include:

The Antenna project has been providing annual updates on the youth and drug scene in Amsterdam, The Netherlands since 1993 (KORF & NABBEN, 2002).

A two-year research study in Berlin, Germany (DOMES & KRAUS, 2002) explored the ability of professional informants to accurately identify new drug tendencies as verified by statistical sources, and, more recently.

The Monitoring System Drogentrends for monitoring drug tendencies, comprising an open scene survey, a school survey and a trend scout panel was developed in order to monitor the German drug scene (KEMMESIES & HESS, 2001).

The Føre Var project was developed with the aim of establishing a system able to provide rapid and reliable identification, monitoring and reporting of drug and alcohol tendencies in the city of Bergen in Norway on an ongoing basis (MOUNTENEY & LEIRVAG, 2004).

The South West Drugs Supply pilot was a multi-agency initiative led by the Regional Availability Group in the South West of England with the aim of gathering information on the supply of drugs classified as Class A by the UK Government: Heroin, Crack and Powder Cocaine and Ecstasy (CURRAN, MAY & WARBURTON, 2005). [9]

1.2 Previous work in England and Wales

Some work of this nature had been carried out within the UK previously; these studies had been beset by practical and methodological problems. An initial scoping study found that existing work in this country covered two tiers of administration as their units of analysis: those projects attempting to measure tendencies and issues on a local basis and those operating at a regional level. Projects ranged in style, with some being information-gathering and audit exercises where existing reports and local intelligence were drawn on, while others were attempts at gaining new information from new sources (e.g. interviews with KPs). None had been published. [10]

1.3 The development and aim of Drugwatch

However while it looked as if some of these studies might fill existing knowledge gaps at a national level they were felt to be too ad hoc, and too narrow in focus, to be of overall use for this purpose. With this in mind the Drugs Analysis and Research Programme (DAR) within the Home Office, embarked on work to develop a model that could be implemented by a national social or market research agency. It was at this stage the study was named Drugwatch. After some initial scoping work in London and Bristol, DAR delivered recommendations as to the implementation, and design, of the Drugwatch project. Incorporating feedback from policy teams it was suggested that a national pilot should be implemented in sites across England and Wales involving telephone interviews with KPs and face-to-face interviews with illicit drug users (IDUs). Ten sites were initially chosen to give an overall indication of how the methodology might work. It was decided that if after piloting more project sites were needed a recommendation would be made to this effect. The ten sites initially chosen to be piloted were Bristol, Birmingham, Cardiff, Liverpool, Leeds, London2), Manchester, Middlesborough and Nottingham. [11]

As the aim of the work was principally to understand, and provide as close to real time information as possible, the implementation of the national drug strategy, it was felt that KP and IDU interviews would provide an excellent opportunity to provide this information. Further work was carried out within DAR to develop a methodology which was settled upon after consultation. This work would involve: [12]

2.1 Interviews with key professionals

The KP interviews in each region would provide essential information on day-to-day experiences in service delivery and perceptions of change in relation to drugs issues. These KPs would be identified as local professionals and community members who had regular contact with, and/or specialist knowledge of IDUs, drug supply, manufacture or treatment and their effect on local communities3). These might include law enforcement officers, drug treatment workers, health promotion workers, Drug Action Team (DAT), and Drug and Alcohol Action Team in Wales (DAAT), co-coordinators, youth workers, psychologists, researchers, counsellors and community groups. It was anticipated that approximately 10-15 KP interviews would be needed at each site to give a thorough enough picture of the drug situation in that area. This would become clearer as the interviews progressed. If it were felt more KP interviews were needed a recommendation would be made to this effect. [13]

2.2 Interviews with illicit drug users

It was also decided that interviews with IDUs should be carried out to supplement the knowledge of KPs. These interviews would provide essential feedback on service delivery and perceptions of change in the drugs market from the users' perspective. Illicit drug users have previously been identified as an appropriate group for detecting drug tendencies, due to their high exposure to many types of illicit drugs. They also have first hand knowledge of the price, perceived purity and availability of the main illicit drug classes. It was felt that IDUs might be recruited from places such as treatment and support agencies, needle exchange services, hostels and drop-in centres, and that approximately 5-8 people would be interviewed at each site. Choosing an appropriate number of drug users to interview was more problematic. Ideally the sample would have been much larger but it was felt that this number initially would be good enough to give a snapshot picture of the drug situation in the area. This would become clearer as the interviews progressed. If it were felt more KP interviews were needed a recommendation would be made to this effect [14]

It was anticipated that for the pilot the study would be conducted in 10 "barometer" sites across England and Wales. Based on where emerging tendencies might be most likely to occur first, sites were principally selected using the UK Government's Index Of Deprivation (ODPM 2004) which is a composite index of deprivation used since 1984 to help distribute funding nationwide to the country's most deprived areas, was used to assist with which sites should be sampled. These indices combine several measures such as: crime, health, education, income worklessness—through long-term limiting illness and other factors—and other general economic inactivity. It was felt that these areas of social and economic need provided an overall measure of multiple-deprivation in the area and establishing those areas where drug problems might emerge in the first instance. However two other indicators were also taken into consideration:

potential drug market activity e.g. whether the areas were designated High Crack and/or Drug Intervention Programme areas; and

geographic and demographic diversity4). [15]

In studying the nature and dynamics of drug using populations for this work it was felt impractical to consider a study of the complete population of some thousands. As well as time and financial resource restrictions, there were no guarantees that attempts to develop a random stratified sample would be successful. An incomplete sample could actually be less representative and actually less helpful especially when an appropriate or complete sampling frame did not exist. According to KENT (1999), researching a small sample carefully, may, in fact, result in greater accuracy than either a very large sample or a complete census. [16]

Purposive sampling was felt to be most appropriate in this case where a targeted sample was needed quickly and where sampling for proportionality was not the primary concern. KPs were identified as an appropriate group for detecting drug tendencies, due to their high exposure to many types of illicit drugs. They also have the first hand knowledge of the issues concerned with drug use and drug market dynamics. As a result it was also felt that they should be recruited in locations where new behaviour in illicit drug use might first emerge. [17]

There were essentially two dual aims of the pilot study. The first of these was to provide real time information about drug market dynamics. To explore these issues, questions in the following areas were developed: [18]

The second, twin aim of the study was to consider how the methodology worked, how it was implemented and how successful the study was as a whole. To explore this the following questions would need very careful consideration throughout:

What would be the best balance of occupations/perspectives within the KPs? Should individuals be retained for successive sweeps or new KPs be recruited each time? What would the optimum number of KI interviews be?

How time intensive would the IDU interview process be? Were there any issues of interviewer safety? Would it be more practical to continue the study "in house" or tender out to a social research company?

Would there be any scope for relating interview data to quantitative performance data? Was there any time lag between identifying issues qualitatively and them being reflected in quantitative data? [19]

In June 2004 a final model for the study was developed, which was felt would be just as much of a local engagement process as a study.

Figure 1: Process model [20]

At the reporting stage of the process the cycle comes back to the beginning, except that this time policy consultation is driven by the findings of the previous sweep. Policy teams can chose to investigate an issue which has arisen from the first sweep in more detail, or alternatively, a set of completely different issues that have arisen as a priority since the last sweep began, or run the same sweep over again to develop tendency monitoring. [21]

Two biannual sweeps were commissioned to begin in September 2004 to deliver results for December of that year, with a second beginning in March 2005 to deliver results in June 2005. [22]

3. Implementing the Model: First Sweep

One of the major questions in any large-scale research project relates to the make-up of the team. For a piece of quantitative research, such as a face-to-face survey of 1,000 members of the public, the core team can be quite small, with perhaps a couple of researchers supervising, a field manager overseeing the fieldwork and a team of dedicated field interviewers carrying out the interviews. [23]

Qualitative research, however, requires considerably more input from suitably trained researchers, more so in a project the size, length and complexity of Drugwatch. Given that face-to-face interviews would need to be conducted with drug users across the country, it was decided that this study would require a sizeable core team which allowed for a degree of continuity throughout the life of the project and would conduct all the interviews. [24]

Ten researchers were brought into the team, which was headed up by an Associate Director. Two Senior Research Executives headed up the twin elements of the study: one taking responsibility for supervising the KP interviews, with the other overseeing the drug user interviews. A further eight researchers made up the fieldwork team. It was then decided that each member of the team (along with the two senior research executives) would take responsibility for the pilot site. [25]

3.2 Topic guides and interview methodology

Two topic guides were developed for the project, one for the KPs and one for the IDUs, essentially building on good practice carried out in the developmental phases, and to enable some degree of continuity and comparison. The topic guides were developed to reflect the fact that the KP interviews would be carried out via telephone while the IDU interviews would be face-to-face. [26]

It was also important to differentiate the type of information which each of the interviews would be able to provide. When trying to engage with drug users, for instance, it was felt to be important that only information relevant to the research project was gathered, as opposed to issues such as individual drug use careers for example. The decision was therefore taken to keep the topic guides as focused as possible on knowledge of current drug use and supply patterns in the local area, with further sections where applicable on drug treatment and community initiatives. [27]

It was also decided that all the interviews would be tape-recorded. It was thought this would be helpful for a number of reasons: firstly, to ensure that reporting was not based purely on researcher recollection; secondly, it would allow for an element of back-checking to guarantee research quality; and lastly, for ease of transcription. [28]

Although reporting mechanisms were not felt to be an urgent consideration so early in the project, some time was spent in the initial stages looking into the issue of transcription and the recording of interview information, as it was felt that any decision would impact on the conduct on the interviews and the management of interview data. The conclusion was reached that it would be neither feasible nor a key project requirement to transcribe all the interviews, as it would be extremely difficult to manage 300 detailed transcripts. Instead, a proforma for recording KP responses was developed for the researchers to complete after each interview while reviewing and playing back the tape. This is shown in the Appendix. [29]

In making this decision, the whole data management issue was considered whether the interviews were transcribed or not, 300 depth interviews can generate a great deal of unwieldy information. The XSight data management package for large-scale qualitative studies was considered for handling the data requirements of the project. XSight is particularly useful if rapid analysis is needed as it can provides a range of frameworks for inputting, analysing and interpreting your findings that best suit researchers who have unique working styles and methodological approaches. While XSight allows qualitative information to be tracked and cross-referenced between interviews it was felt that the level of investment of time setting up the programming for an electronic analysis of these interviews would not provide only minimal returns. [30]

Although it involved a sizeable number of interviews in total, the reporting requirements of Drugwatch were broken down into manageable "packages" of 15 interviews. [31]

Once the interviews were carried out and key points placed onto the proforma, themes and issues were drawn out for each area by each researcher. The team then got together for a brainstorming session where they began to draw out patterns and tendencies at a national level. [32]

As it turned out through this process, a single contact to the DAT or DAAT coordinator was all that was required to generate significant numbers of potential interviewees in each site. Where these potential interviewees could be identified, it was found that around 40 per cent were treatment providers, 30 per cent were in the Criminal Justice System, 15 per cent were working with young people, 10 per cent had a strategic overview and around five per cent were from social/community services. As a simple indication of the interview penetration, somewhere between 12 and 26 leads were achieved per site. [33]

Interviews were then arranged with the leads at each site by a specialist recruiter, from outside the core project team, who was fully briefed as to the need to convert these contacts into interviews. If a particular lead was unwilling or unable to participate, they were asked to suggest further leads from them in an attempt to build up a snowball contact. [34]

All the interviews were carried out by the core project team, and to this end, spreadsheets were set up which allowed for central booking of interview slots. Each researcher aimed to conduct, record and make notes on ten telephone interviews, which were allocated on a "first come, first served" basis. The first sweep of KP interviews began in mid-October and were all completed by the first week of December 2004. [35]

3.5 Interviews with illicit drug users

The KP interviews were quickly and reliably carried out. It was decided not to run the IDU interviews concurrently for two reasons: firstly and primarily, not want to overstretch the researchers; and secondly, it was thought that the KP interviews would be a good method of generating opportunities to conduct the IDU interviews. [36]

3.6 Training the research team

While each member of the core research team had been chosen for their qualitative research abilities, it was desirable to ensure that they were all confident at interviewing such a hard-to-reach group as IDUs. It was felt that a vital element to any successful fieldwork was that the researchers were able to engage effectively with the target population, so that the information gathered from the interviews would not be compromised. [37]

An independent researcher and peer trainer was brought in to undertake some in-field training over a two week period. Researchers spent between half a day and a full day with the trainer in London, visiting drug treatment agencies, needle exchanges and community centres among others. Throughout this training, emphasis was made of "what not to do" as well as good practice when engaging with vulnerable people. [38]

The researchers learned about the importance of body language and clothing, the need for neutral interview locations, how to put interviewees at ease, how to make interviewees feel that they are being consulted because of their expertise and how to obtain informed consent to tape-record the interview. They also learned valuable lessons about personal safety. [39]

After all the researchers had been on these training sessions, the team met to discuss their experiences and good practice. Both of these elements, the training and the follow up meeting, were central to the later success of the interviews as the researchers felt that they had given them a great deal of confidence in preparation for the fieldwork. [40]

3.7 Planning and conducting the interviews

One of the primary concerns in the development of the fieldwork phase had been the safety of the field researchers when interviewing IDUs. It was therefore decided to "batch" the interviews so that a pair of researchers would visit a designated site for a two day period. It was felt that this would ensure safety and provide adequate time to familiarise themselves with the site and to snowball interviews where necessary. To reinforce safety, researchers were issued with identity cards, personal alarms if requested and each research pair was made up of one male and one female researcher. [41]

These five research pairs were each responsible for carrying out the IDU interviews in two sites, which were grouped as follows, with one member of each pair taking lead responsibility for organising interviews in one of their designated sites. [42]

As well as being prepared for the possibility of snowballing interviews with IDUs, it was felt that at least two appointments with IDUs should be pre-booked in each site. These appointments were arranged by the research pair through return calls to the KP interviewees. It should be remembered that the original KP interviews had been randomly allocated to the core research team and that this might have been thought to cause a problem when it came to recontacting those interviewees. [43]

There could have been two potential difficulties at this stage: Firstly, if neither member of the research pair responsible for a particular site had interviewed a specific professional, they may not have been familiar with the role of that professional. Secondly, the original interviewer may have been able to establish a rapport with the interviewee which would not be available to a "cold calling" member of the research pair. [44]

These difficulties did not however arise, largely due to the high level of information sharing among the core research team. If the members of a research pair needed to contact people who they had not personally interviewed, they were encouraged to speak to the original interviewer and to share interview notes. This meant that when they recontacted a professional interviewee to arrange appointments, they were quickly up to speed on the issues in the area and the role and responsibilities of the interviewee. [45]

The appointments which were arranged were recorded on a site sheet and were a key element to the success of the IDU interviews. The researchers had all been made aware of the pitfalls of recruiting people solely through drug projects and so were careful in their selection of appointment venues. Appointments were made with IDUs through outreach, day centres, needle exchanges, the probation service and prisons, as well as through treatment providers and through the drug users themselves. [46]

In all cases, these appointments were treated as the springboard for further interviews, to the point where some researchers found themselves being presented with more opportunities for interview by drug users themselves than were actually required. [47]

Results were delivered on time in December 2005. These are discussed in more detail later but some methodological changes were made for the second sweep which are discussed first. [48]

4. Implementing the Model: Second Sweep

Prior to the project it was decided that a number of methodological changes would be made between the first and second sweeps to fully examine the methodology. So once the reporting for the first sweep had been completed planning for the second began. The first step initially was to recap best practice in a seminar discussion and assess what might be retained and what might be changed in time for fieldwork to begin in March 2006. There was also discussion about what might be changed to provide a better understanding of how the processes worked. [49]

4.1 The research team and the topic guides

Both the research team and the topic guides remained broadly the same as in wave 1. The only amendment was to the KP topic guide where it was felt that the section on "community" did not provide as much value as it could have. This was therefore adapted slightly to ask about impacts to the local community as well as community responses to drugs. [50]

4.2 The adapted methodology: Interviews with key professional

The same interview methodology was maintained for wave 2, namely tape recorded interviews with KPs and tape recorded face-to-face interviews with IDUs. But for the purposes of the pilot, however a number of modifications were made to the recruitment process for KPs:

In four areas it was decided that the same professionals would be interviewed as in wave one;

in another four areas half of the original professional interviewees, were interviewed along with "new" interviewees; and

in the remaining two areas a full new set of KPs were interviewed. [51]

The reason for this variation was essentially to see if different KP interviewees would provide different perspectives, either enhancing the quality of information gathered or diminishing the use to which it could be made. This could be either because they worked in a different sector or fulfilled a different role, and so had not been recommended as a contact in the first wave. In particular it was felt important to identify:

what range of KPs were available for interview in local areas;

whether the information received from different KP interviewees would diverge radically from that gathered on the first wave, this would obviously then present problems about the presentation of qualitative findings on any future study should the work be rolled out on a regular basis. [52]

It was felt that with Drugwatch being a pilot the potential learning lessons of how well the process had worked would be enhanced by changing the interviewees at some sites. In the first four areas it was felt that this strategy would allow a certain amount of checking as to whether the situation had changed in the interviewees view, whether the interviewee is giving the same information as in wave one, or whether they were giving information which did not accord with what they had said in wave one. In the two areas where interviews were conducted with the "new" KPs, the research team were able to assess whether they reported anything different from the KPs interviewed in wave one. [53]

Finally in the four areas where a mix of existing and new KPs were interviewed the research team felt that would be able to assess the relative value which should be placed on interviewing the same or different people in consecutive waves. [54]

4.3 The adapted methodology: Interviews with illicit drug users

There were two modifications to this element of the research for the second sweep: firstly the researchers were encouraged to seek out new routes into drug user networks; while secondly after discussion it was decided that another element be added to the methodology. [55]

Given the nature of the study there was a feeling that it would be worthwhile to test how well IDUs knew their own networks and whether a suitably trained and assessed drug user could access information about drug use and supply which would not be made available to an outside interviewer. In one of the sites a current drug user was recruited, assessed and trained to carry out five IDU interviews. This would not replace those carried out by the fieldwork team at the site but effectively supplemented them allowing for a level of comparison between the two interview methodologies. Equally important was the fact that this would allow road testing of a drug user peer interviewer. There was a feeling that if they added value to the research findings this was a process that might add time and value to any wider roll out. [56]

Findings were produced for the two main aims of the work, which were to provide real time information and an assessment of the method and therefore the process. [57]

Findings from both sweeps are summarised below, in Table 1, to give an indication of the style of findings that a piece of work of this nature and scope might produce. They are presented as areas where KPs and IDUs have been able to highlight positive developments. They then move on to discuss continuing challenges around drug use, drug supply and treatment. Finally there is a short presentation of potentially new tendencies. [58]

Two of the key strengths of qualitative research are that it allows issues to be explored in detail and enables researchers to test the strength of people's opinion. However, as well as generating theory, the qualitative research in this context was used to be illustrative, rather than statistically representative of any region or group, and as a result this information does not allow conclusions to be drawn about the extent to which views are held nationally, on any great scale.

|

|

First sweep (December 2004) |

Second Sweep (June 2005) |

|

Positive developments

|

Improved access to treatment In general, there was a consensus among both the IDUs and KPs who were interviewed as part of this project that the quality and supply of treatment has improved over the last few years. Respondents generally felt this to be as a result of increased funding and better partnership working. Reduction in street dealing In nearly all the Drugwatch areas, drug-using interviewees reported an increased use of "closed" supply routes and a corresponding perceived decrease in "open" street buying. Some felt that this shift might be related to successful law enforcement crack-downs on dealers. Community responses are successful—where they exist According to KPs interviewed for the first sweep of Drugwatch, community-based solutions and public involvement are highly prized. When they are in place, these types of solutions are felt to be more successful than top-down delivery of treatment and preventative measures. |

Improved access to treatment A number of respondents from this sweep mentioned that the Drugs Interventions Programme had increased treatment capacity. The use of "dance drugs" perceived as having plateaued At some sites there was a perception among a number of KPs and IDUs that the use of "dance drugs" had reached a plateau in their area. Further to this however, was a perception that ecstasy was being replaced by increasingly inexpensive cocaine. |

|

Continuing challenges

|

Polydrug use of heroin and crack are still the main issue Polydrug use was largely felt by respondents to reflect the pattern of dealing, with crack and heroin often being sold together, sometimes for a discounted price. The majority of IDUs interviewed for this study felt that it was increasingly popular for a drug user to be using more than one drug regularly. Alcohol and cannabis use bigger concern than Class A drugs among those dealing with young people Many interviewees noted that IDUs often also misuse other substances. As such, treatment professionals in particular, reported that it was difficult to treat the misuse of Class A drugs in isolation from other misuse problems and broader social problems. The market can absorb shocks In all ten areas, it was felt by KPs and IDUs alike that drug markets could absorb significant shocks. The market in each area was felt to be a complex organism quickly reactive to external changes in supply and police interventions. Generally, local markets were seen as ranging from small-scale user/dealers through to professional dealers employing a pool of "runners" to deal. Many people interviewed felt that street dealing markets were becoming less prevalent, all the experienced IDUs involved in this study noted that they rarely experienced difficulty accessing drugs. The only time that a supply drought was mentioned was generally Christmas. Continued demand for improved access to treatment The majority of respondents felt that treatment is continually improving. However, across all the Drugwatch areas respondents from the treatment field felt that a number of service gaps remained, particularly among groups such as young people, female IDUs and Black and Minority Ethnic (BME) groups. Another common theme mentioned by a number of respondents in most areas was that treatment should be provided outside standard office hours. Crack and cocaine use A number of treatment interviewees suggested that while heroin use did not appear to have changed dramatically over the last few years, they were seeing more people reporting polydrug use of heroin and crack, which they were sometimes injecting at the same time. |

Polydrug use of heroin and crack is still the main issue Again polydrug use is seen as the largest continuing challenge. Although in the second wave there seems to be a general feeling that crack use was beginning to supersede heroin use. Alcohol and cannabis use bigger concern than Class A drugs among those dealing with young people Once again cannabis and alcohol misuse were seen as widespread by KPs and IDUs. In fact, these substances were seen, by KPs particularly, as the main problematic substances among young people. The market can absorb shocks The continued perception that drug markets could generally absorb enforcement activity. The market in each area was felt to be a complex organism quickly reactive to external changes in supply and police interventions. Continued demand for improved access to treatment Again there was a continuing perception by interviewees that a number of service gaps remained in the treatment domain specialising in some areas. Out of hours treatment was again mentioned as a continuing challenge. Earlier injection in non-traditional sites Once again the issue of earlier injection in non-traditional sites was mentioned by KPs and IDUs alike. Some respondents mentioned drug quality as a reason why IDUs were injecting into sites such as their groin earlier, although groin injection was not a universal finding, it was mentioned by a number of respondents independently as something which was now being seen as, and would continue to be, a continuing challenge. Crack and cocaine use The perceived use of crack and cocaine was being seen as a continuing challenge.

|

|

New tendencies

|

More customer-focused dealing A number of IDUs interviewed for the study felt that dealers have/had adopted a more "customer friendly" approach to their business. IDUs noted that dealers have dramatically changed the way they did business, bringing much more of a customer focus to their trade. Earlier injection in non-traditional parts of the body Across many sites, poorer drug quality was seen as a reason why IDUs were "taking more chances" i.e. injecting earlier in their drug use careers than had previously been identified and injecting in sites such as the groin. Some treatment workers felt this might be a growing trend and is of particular concern, given its linkages to negative health outcomes such as overdose and deep vein thrombosis. |

No new tendencies were identified since the completion of the first sweep

|

Table 1: First and second sweep findings [59]

The second, parallel aim of the work, as has been stated throughout was an examination of the methodology and how successful it was at answering the research questions was of high importance. The overall assessment of the process is discussed in detail within the conclusions, however good practice conclusions from the work are shown below.

|

The final wave of fieldwork was completed by the middle of June 2004, with both waves having been concluded extremely efficiently. All the interviews had been conducted, all had been recorded and noted and all had been done without compromising researcher safety or the robustness of the project. There were a number of methodological conclusions noted more specifically: |

|

Table 2: Good practice methodological conclusions [60]

6. Conclusions and Implications

Experience of the work and both waves of Drugwatch as a national pilot suggested that the implementation of the process did seem to work well. Interviewing KPs, both in the developmental work and the pilot, was found to be a relatively easy task, while engaging with drug users willing to contribute to the research findings was both manageable and fruitful. The study certainly seemed to interrogate the current "state of things" (or confirm understanding of what they are) and to get people to reflect on change over a time period of the past few years. It was quite heartening that some fairly consistent messages came out of most, if not all, of the research areas, which suggests that the approach is not confounded by a great deal of diversity between the make-up and experiences of different localities. [61]

One major issue was the timing of the waves. There were no real identifiable "new incidents" from the first sweep to the second, so there came a point of stalemate towards the end of the work. What might be the reason for this? Perhaps the main reason was felt to be that interviewees continually tended to think and talk about their experiences in terms of one or two years, as opposed to periods of six months. It now seems clearer that a relatively long time period would be needed to detect any meaningful changes or tendencies as they occurred, except in very discrete areas where, for example, new initiatives are being set up (e.g. DIP, or particular police operations) and lead to a step change in the way that things are being done. [62]

There is an argument to suggest however that the continued existence of the same issues might constitute the beginnings of a tendency in themselves, rather than simply an occurrence, and what is meant by tendencies? Is it something that just occurred once and then went away? Would it be something that appeared at one site in the first sweep, at two or three geographically linked sites in the second etc.? Or something that appeared at all sites in one sweep and then again in the second and third etc.? Basically all of these would seem to be correct. The perspective taken here then is that a tendency is a prevailing direction or drift. A major tendency is more than simply an important tendency. It is a tendency that will tend to define the future. A major tendency has explanatory potential and these are the tendencies that the project is aiming to identify. From that perspective then the mere discovery that there are no new issues does not make the project redundant. It simply reinforces the fact that certain issues are continuing in a certain direction and therefore becoming tendencies in themselves. [63]

The project did however highlight some of the potential limitations of the KP approach in terms of whether to keep the same informants (and risk that they exaggerate the changes they have noticed) or change and risk inconsistency in perspectives. There are also obvious difficulties in taking interview responses at face value, these are after all people's views, and therefore reflect what they believe and think, and the agendas that they are working on, as a result some of the information being gathered might seem a little hazy at times, and based on speculation rather than anything more concrete. There is probably a debate about what extent any research team involved in such work should filter information that appears speculative and/or inconsistent, or whether it should be included anyway and caveated appropriately. Whichever approach is taken, there is a potential that other professionals such as local researchers for example, with a stronger background or expertise in drugs, may be better placed to make these kinds of judgements about their own area. [64]

6.2 Resourcing and implications for the future

While it was felt to have been successful there was a feeling that the project was also resource hungry—at one point a team of four researchers were working full time on developmental work. This level of commitment doubled when the project was tendered out to a research company. Couple this with the fact that the project seemed to come to a point where there were clearly diminishing returns, as described above. [65]

As a result, while a sound idea, resourcing suggested the impracticality of making Drugwatch a quarterly or even biannual study, certainly at a national level where the input of a large number of KPs and IDUs is required to make the study worthwhile. [66]

As has been mentioned previously Drugwatch might be considered more of a process than a research study, in that it can "tap into" professional consciousness to consider the issues of key local importance. It can alert professionals from national agencies to issues that are developing quite quickly, and develop an important dialogue between local areas and national agencies. Contrary to some suggestions that local area representatives might suffer "consultation fatigue" during the process, feedback suggested that the majority of KPs interviewed actually felt empowered that national agencies were taking account of their views, and the challenges they were facing in their area. [67]

While the relationship building process of the study should not be underestimated the main strength of the work is in its speed of delivery. What this study found is that once the process is in place it is possible for a national agency to go into the field with a research question or questions, and gain quick and timely responses from across the country within months. [68]

This report has shown the development of an idea from its inception to its implementation. It has also shown a small snapshot of what might be produced with a methodology of this kind. With this in mind there does seem to be a potential future for a process such as this as a policy tool for use in future horizon scanning exercises or as part of the performance management process. Developmental and pilot work has found however that this needs to be on a different scale, and perhaps on a less frequent basis to provide a balance between information needs and value for money. [69]

One potential method might be that of a panel of KPs in each area from which to draw interviewees as these people are also kept in regular e-mail contact. This would allow for a simple electronic "health check" rather than a full wave at whatever periods might be considered most useful. This group might also be one who could utilise a "Delphi methodology" if the issue were one of predicting future tendencies. [70]

Potentially, this is also a method that might be most fruitfully adopted at the local or regional level, as a framework through which local areas collate the intelligence and latent knowledge that they have about any situation in their area, not necessarily just drugs. This seems to have been fruitful in previous work in this area (e.g. CURRAN et al. in Bristol, DOMES and KRAUS in Berlin; KAMMESIES and HESS in Frankfurt; and MOUNTENEY and LEIRVAC in Bergen). However this also then brings into consideration the issue of whether different methodologies might be more successful or even practical at different geographic levels. Smaller, more self contained areas such as DATs or DAATs or Crime and Disorder Reduction Partnerships might present more of an opportunity to explore issues which are of local concern in more detail rather than trying to consider more strategic issues across a geographically diverse area. [71]

Appendix: Drug Professional Interview Pro Forma

1) For example, IDRS findings in recent years indicating the increased availability and use in Australia of potent forms of methamphetamine have made this a priority area for the MCDS and the Commonwealth Government. Although it is undoubtedly the case that other findings, such as those of the Drug Use Monitoring Australia (DUMA) project, would have suggested this as an area for concern, the IDRS provides different information to that provided by DUMA, including terminology, frequency of use, routes of administration, price, purity, purchase quantities and other data, collected from a non-forensic population. <back>

2) Two boroughs in London, Camden and Croydon, were chosen to reflect the disproportionate nature of the issue in the capital. <back>

3) One of the issues that the pilot study aimed to explore was finding the appropriate unit of analysis for the respondents to speak with authority about. It was anticipated that in the pilot study respondents would initially be asked to speak about the situation in their Drug and Alcohol Action Team DA(A)T region. These are areas similar in size to local boroughs used to manage and administrate the provision of local drug services. <back>

4) Within this, there was an attempt to ensure that the research sites covered drug markets with varying characteristics. For example some sites could each additionally provide a very different perspective on emerging tendencies. Perhaps one might provide a particular insight into street-level drug markets; while another might also potentially identify higher-level supply issues; with a third possibly alerting to issues relating to its high level of drug-related crime for example. <back>

Alvarez, Javier; Bello, Pierre-Yves; Feijão, Fernanda; Karachaliou, Krystalia; Kontogeorgiou, Katerina; Lagerqvist, Jenny; Mickelsson, Kajsa; Siamou, Ioanna & Simon, Roland (2003). Emerging drug phenomena: A European manual on the early information function for emerging drug phenomena. Paris: Observatoire Français des Drogues et des Toxicomanies.

Curran, Kathryn; May, Tiggey & Warbuton, Hamish (2000). The South West drug supply pilot: Key findings. Institute for Criminal Policy Research, School of Law, Kings College London.

Darke, Shane; Topp, Libby & Kaye, Sharleen (2001). IDRS: Illicit Drug Reporting System. Illicit Drug Trends Bulletin, December. Sydney: National Drug and Alcohol Research Centre.

Domes, Reiner & Kraus, Ludwig (2002). An early recognition system for drug trends in Berlin. In EMCDDA (Ed.), Understanding and responding to drug use: The role of qualitative research (pp.233-236). Lisbon, Portugal: European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction.

Kemmesies, Uwe E. & Hess, Henner (2001). MoSyd. Monitoring-System Drogentrends. Frankfurt, Germany: Centre for Drug Research.

Kent, Richard (1999). Customer relationships in small manufacturing companies: The importance of Social Bonding. Ayrshire, Archie McLeod, NextLevel Associates.

Korf, Dirk J., & Nabben, Ton (2002). Antenna: A multi-method approach to assessing new drug trends. In EMCDDA (Ed.), Understanding and responding to drug use: The role of qualitative research (pp.8-9). Lisbon, Portugal: European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction.

May Tiggey; Harocopos Alex; Turnbull, Paul & Hough, Mike (2000). Serving up: The impact of low-level police enforcement on drug markets. London: Home Office.

Mounteney, Jane & Leirvåg, Siv-Elin (2004). Providing an earlier warning of emerging drug trends: The fore ver system. Drugs Education, Prevention and Policy, 11(6), 449-471.

Office of National Drug Control Policy (2004). Drug markets and chronic users in 25 of America's largest cities. Special topic: Local drug markets—A decade of change. Washington, D.C.: Office of National Drug Control Policy.

Office of the Deputy Prime Minister (2004). The English indices of deprivation 2004 (revised). London: Office of the Deputy Prime Minister.

Mark MASON has spent more than ten years in public sector environments carrying out, commissioning, managing and disseminating research. Working closely with policy makers and a range of stakeholders, his work has involved a wide range of clients in a number of areas. This has contributed to giving Mark a very wide base in managing and carrying out practical research issues. He has expertise in, and has previously published work in the areas of domestic violence, community safety and illicit drugs (especially drug markets, and drug supply and trafficking).

Contact:

Mark Mason, Senior Research Officer

Government Office for London

London Regional Research Team, 4th Floor

Riverwalk House, 157-161 Millbank, London, SW1P 4RR, UK

Tel: +44 (0) 20 7 035 0408

E-mail: mark.mason@homeoffice.gsi.gov.uk

Oswin BAKER is an Associate Director in MORI's Social Research Institute and has spent the last decade writing about social exclusion and researching hard-to-reach groups. He has previously worked at the Institute for the Study of Drug Dependence (now Drugscope) where he researched the drug-crime link, and as a consultant specialising in community consultation. Oswin has written extensively about drugs and social exclusion.

Contact:

Oswin Baker, Associate Director

Market and Opinion Research International

79-81 Borough Road, London, SE1 1FY, UK

Tel: +44 (0) 20 7347 3190

E-mail: oswin.baker@MORI.com

Rebecca HARDY worked in the Communities department of the Home Office before joining MORI. In both posts she has worked on community consultation issues, ethnic diversity and citizenship issues and published in all areas.

Contact:

Rebecca Hardy, Senior Research Executive

Market and Opinion Research International

79-81 Borough Road, London, SE1 1FY, UK

Tel: +44 (0) 20 7347 3190

E-mail: Rebecca.hardy@MORI.com

Mason, Mark; Baker, Oswin & Hardy, Rebecca (2007). Drugwatch: Establishing the Practicality and Feasibility of Using Key Professionals and Illicit Drug Users to Identify Emerging Drug Tendencies [71 paragraphs]. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung / Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 8(3), Art. 9, http://nbn-resolving.de/urn:nbn:de:0114-fqs070393.