Volume 19, No. 1, Art. 15 – January 2018

Visual Arts as a Tool for Phenomenology

Anna S. CohenMiller

Abstract: In this article I explain the process and benefits of using visual arts as a tool within a transcendental phenomenological study. I present and discuss drawings created and described by four participants over the course of twelve interviews. Findings suggest the utility of visual arts methods within the phenomenological toolset to encourage participant voice through easing communication and facilitating understanding.

Key words: arts-based research; arts-informed research; participant voice; visual arts; drawing; art elicitation techniques; transcendental phenomenology; graduate student mother; DocMama; mothers and art; gender

Table of Contents

1. Preface

2. Arts-Based Methods and Becoming a Mother in Academia

3. Arts-Based Research

4. Arts and Phenomenology

5. Walking through the Study: Steps of Data Collection and Analysis

5.1 Phenomenological interviewing using visual arts

5.2 The participants: DocMamas sharing experience

5.2.1 DocMama1: A business major with one child

5.2.2 DocMama2: A social sciences major, pregnant with her second child

5.2.3 DocMama3: A science major with one child

5.2.4 DocMama4: An education major with one child

6. Discussion

I walked through the dark atrium of the library, retrieving a key from the friendly albeit aloof student receptionists at the library counter. Ascending a grand staircase, I gingerly walked past students quietly reading and taking notes. Through the grand space I walked, moving beyond the stacks of books, searching for the closed, locked door with the proper number. Once inside, the white walled room was immediately filled with fluorescent light as I switched the light on. It wasn't a particularly welcoming space, too sterile, too cold, and only slightly larger than the table inside. I soon got to work to prepare the space for interviews with the new mothers. I diffused essential oils to improve the stagnant air and rearranged the table, arranging the chairs side-by-side to help reduce the power imbalance between researcher and participant. On top of the tables, I placed plain white printer paper, a variety of markers and colored pencils. I was now ready to begin my first interview and art elicitation. [1]

2. Arts-Based Methods and Becoming a Mother in Academia

What is the experience of becoming a first time mother within a doctoral program? How do people navigate this space? It was from my own nuanced experiences of becoming a mother in a doctoral program that these questions emerged and a transcendental phenomenological study commenced, a study for my dissertation that incorporated visual arts methods. In this article, I detail the process of using visual arts—drawings created and described by participants to explain their experience of becoming a mother while in their doctoral program. [2]

When I began my doctoral studies, I did not have any children and did not plan to study motherhood. Yet by the end of my first year, I was pregnant with my son. Becoming a mother in my doctoral program was a major transition in my life, one which opened my eyes to the structural obstacles and personal challenges of being a mother in academia. From a small cohort of doctoral studies in my program, two other colleagues also became pregnant with their first child. Even though we were all in the same program, in the same year, all having become pregnant for the first time, our academic experiences with the university, faculty, and courses varied greatly. [3]

With the increase of women in doctoral programs, there has also been an increase of women becoming mothers. Being enrolled in a doctoral program stands in contrast to full time employment. Doctoral students in the U.S. are expected to pay for their education or at best work part-time in exchange for certain benefits, none of which typically include maternity leave. Doctoral students as mothers juggle additional "plates" which are incomparable to typical employment. As MASON (2009) explains, graduate students are at "their peak childbearing years" (§5). She notes in an interview about her extensive survey of doctoral students that

"More than two-thirds of the women in our doctoral survey agreed that the ages between 28 and 34 would be the optimal time to have a first child—the very years in which they are struggling to obtain a Ph.D. Yet 33 is now the average age at which women receive a Ph.D., and they cannot expect to achieve tenure before they are 39. They can see their biological clocks running out before they achieve the golden ring of tenure" (ibid.). [4]

In Europe, women are regularly outnumbering men for the first time in many fields (EUROSTAT, 2017). Likewise, in the US, graduate students are predominantly women (OKAHANA, FEASTER & ALLUM, 2016, p.4). Yet structural and individual challenges persist for women progressing through the academic pipeline, from junior to senior positions. Women in academia face challenges individually and institutionally that are exacerbated once they have become mothers. For those who choose to combine being a mother with a tenure track position face challenges that have yet to be fully understood and/or addressed. These often-simultaneous "ticking clocks" of tenure and biology are of concern for many junior women academics as they aim to reach unrealistic goals (see MASON, WOLFINGER & GOULDEN, 2013; SALLEE, WARD & WOLF-WENDEL, 2016; WARD & WOLF-WENDEL, 2017). [5]

Mothers in academia are often the primary caretaker and have limited paid leave (if at all) for maternity leave and breastfeeding. WOLFINGER, MASON and GOULDEN (2008) explain in their longitudinal study of doctoral student recipients in the US, "family and children account for the lower rate at which women obtain tenure-track jobs" (p.389). Challenges faced by academic mothers can be seen in other countries as well, even in Nordic countries with high levels of family policy supports (MAYER & TIKKA, 2008). Likewise, within academia, graduate student mothers face internal and external obstacles and challenges (CHUNG, 2015; DEMERS, 2014; KULP, 2016; SWARTS, 2016; TIU WU, 2013; TREPAL, STINCHFIELD & HAIYASOSO, 2014; TUCKER, 2016; ZHANG, 2011), such as guilt, costs of childcare, and perceptions by others on academic focus. While there is an increase in the number of studies on the topic of women and mothers in academia, few studies have examined graduate student mother experiences and needs (COHENMILLER, 2014a; PHILIPSEN, 2008). [6]

Both within the U.S. and in Europe supporting mothers in academia can be seen as a means towards gender equity (HARVÁNKOVÁ & COHENMILLER, 2017). However, there is still a need to further understand these experiences across cultural borders. The growing need for more research and policy to support early academics led to this study. In this article I describe the study of doctoral student mothers and the visual arts approach used to encourage communication and understanding. The subsequent sections lay the groundwork for the study situating it within the research on arts-based research and phenomenology, followed by a description of the study, sample drawings and descriptions of the experiences before and after creating the artwork. The resultant description and discussion highlight the utility of the drawing as a tool for transcendental phenomenology to encourage participants' voice through easing communication and facilitating understanding. [7]

Arts-based research (ABR) has been expanding in its use to understand and explore topics important for issues of equity and social justice, allowing researchers to reach a wider audience (LEAVY, 2017). Similarly, the topic of doctoral student motherhood and mothering in academia is an emerging topic that has been noted as needing more research (COHENMILLER, 2016a; MASON et al., 2013; PHILIPSEN, 2008; TUCKER, 2016). Through increasing our understanding of the experiences and challenges for mothers in academia, we have seen that additional supports can be addressed to improve recruitment, retention and equity for women in the profession (COHENMILLER, 2014a; PHILIPSEN, 2008). [8]

Researchers have found incorporating arts-based research (ABR) a useful tool to address sensitive topics (KNOWLES & COLE, 2008). Within educational research, ABR supports new perspectives: "Arts-based educational research is founded on the belief that the arts have the ability to contribute particular insights into, and enhance understandings of phenomena that are of interest to educational researchers" (O'DONOGHUE, 2009, p.352). STICKLEY et al. (2016) have shown that arts can support wellbeing in general, while HOGAN (2015) explained how arts were used to support women's transition to motherhood. In interviewing mothers, sensitive topics could include typically private aspects such as physical and emotional aspects (e.g., birthing, nursing, post-partum depression), changes in one's identity (LANEY, HALL, ANDERSON & WILLINGHAM, 2015), and pressures related to societal expectations (TREPAL et al., 2014). ABR's capacity to bring about new perspectives and address sensitive topics makes it suitable to include in a phenomenological study of doctoral students who are also mothers. As a doctoral student mother at the time of the study, I knew of the potential challenges of both speaking about such a sensitive topic and also articulating the experience. [9]

Using the arts within and for research has become increasingly popular. Some commonly used terms that refer to various uses of arts within research include such terminology as arts-based research (ABR), arts-informed research, arts-inspired research, a/r/t/ography1), and visual methods. Within this article, I use the terminology described by LEAVY (2017) that distinguishes arts-based methods, such as drawings and paintings, from arts-based research as a philosophical approach. [10]

The arts are used in many ways in research, such as in supporting programs with historically disadvantaged groups (COHOLIC, COTE-MEEK & RECOLLET, 2017), with vulnerable children (COHOLIC & EYS, 2016), with international children addressing their concerns for the future (HOLDEN, JOLDOSHALIEVA & SHAMATOV, 2008), for social change working with adults (HAYES & YORKS, 2007), and for studying wellbeing (COHENMILLER & DEMERS, 2017). By incorporating ABR, additional insights are possible: "This philosophical belief system, which developed at the intersection of the arts and sciences, suggests that the arts are able to access that which is otherwise out of reach" (LEAVY, 2017, p.14). Such use of arts-based research has been brought to prominence in the social science and educational research through the work of EISNER (2008), HAYWOOD ROLLING (2013), LAWRENCE-LIGHTFOOT and DAVIS (1997), LEAVY (2015, 2017), and PINK (2012), to name a few. [11]

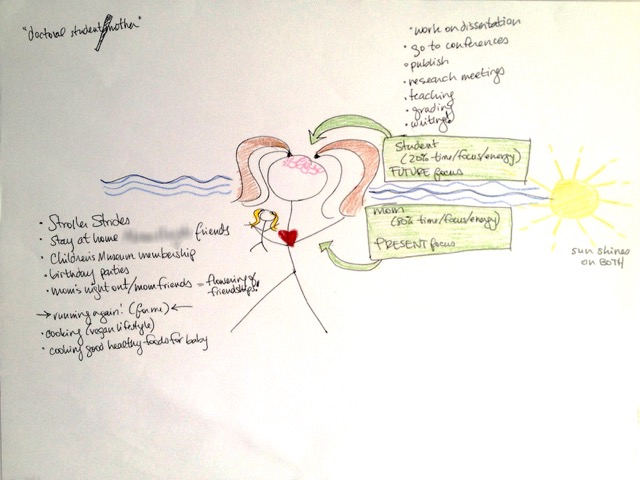

The use of ABR can provide a means to support participants in expressing themselves. For example, LEAVY (2017) provides an overview of how ABR can support participants and address emergent questions, at times being participatory and at times not: "This approach has the potential to bring forth data that would not emerge with written or verbal communication alone ..." (p.20). [12]

Arts-based research provides a way to understand experiences in multiple ways. Some researchers utilize ABR approaches within the data collection, within the data analysis, and/or within the findings. ABR assists in exposing additional ways of understanding while potentially broadening the audience (LEAVY, 2015). Using the arts within qualitative research has been practiced across disciplines, from sociology to education, and within multiple types of methods from focus group, interviews, to methodologies such as autoethnography. [13]

While there is limited research using the arts to specifically study doctoral student mothers, or even graduate student parents, the integration of arts to study the experiences of mothers outside of academia is not new. For example, there are conferences that focus on it; The Museum of Motherhood hosts a yearly conference on motherhood and mothering. At this interdisciplinary conference, arts-based methods, analysis and performance have been central to understanding the varied experiences and representations of mothers, motherhood, and mothering. Other conferences are encouraging the arts in studying mothers in society including using popular culture to examine motherhood and mothering (SOUTHWEST POPULAR/AMERICAN CULTURE ASSOCIATION, 2017). [14]

However, there is little empirical research on ABR and mothering within academia. A few exceptions are the dissertation study discussed here (COHENMILLER, 2014b), another dissertation study incorporating ABR methods within an autoethnographic study of being a Korean doctoral student mother (CHUNG, 2015), and follow-up studies (also using arts-based methods) conducted with motherscholars (COHENMILLER, 2016a, 2016b; COHENMILLER & DEMERS, 2017). [15]

Art has long been a subject of phenomenological philosophical texts. For HEIDEGGER (2002 [1950]), aesthetics and the arts were considered essential, "an expression of human life" (p.57). Furthermore, others examining phenomenology and the arts, such as noted philosophers HENRY and MARION, examined phenomenological aesthetics and looked at art as a means for understanding the invisible and visible (GSCHWANDTNER, 2014). The process of creating art can then be considered transformative. As GSCHWANDTNER elucidates of Marion's attention to aesthetics,

"[c]reating a work of art is actually a process of making visible, transferring a phenomenon from one reality to another, even a kind of popularizing move in which a phenomenon so far inaccessible is made accessible for a larger group of viewers" (pp.306-307). [16]

While MARION and HENRY explored artwork created by others (e.g., KANDINSKY), participants within a phenomenological study can engage artistic aspects of themselves by using visual arts methods when they put pen to paper and are guided to create drawings based upon a researcher prompt—accessing new means of representation and making the invisible, visible. [17]

Art as such can be used to uncover lived experience (DEWEY, 2005 [1934]). One such way to expand on the researcher's toolkit is through artistic expression—as an aesthetic representation to express human life (HEIDEGGER, 2002 [1950]) or to add depth to understanding experience. LAWRENCE-LIGHTFOOT and DAVIS (1997) note the relevance of artistic expression, "[i]t was against this colorful historic canvas—from Rousseau to James to Dewey to DuBois to Geertz—that I began to draw the artistic and scientific form that overlapped to shape my version of social science portraiture" (p.8). [18]

Drawings or other art forms created by participants can help provide a way for individuals to think about, reflect, and actually see their experiences. Arts can provide a mental break, a physical space, and opportunity to think more deeply. GUENETTE and MARSHALL (2009) suggest that drawings can provide a useful means of communication for some participants to "have the opportunity to switch from a purely verbal way of expressing oneself to a more creative form. It can also provide valuable distance from what has been experienced; a 'break' from a more intense verbal process" (p.87). For other participants, drawings may provide insights to descriptions of experiences formerly dormant. [19]

Art creation can be considered in line with highly descriptive text, metaphors and analogies that can articulate experience, but used instead with pen on paper to create images. By providing an additional avenue for participants to describe their experiences, creating art can allow both for individuals to better express their experience and also for the researcher to read between the lines of the experience described/drawn. Ultimately it appears that through participant's artistic representations, the phenomenologist can gain valuable insight into the life-world of the individual experience. [20]

In phenomenological methodology, a tradition that tends to rely on textual analysis, art can be utilized to complement the methodology by providing insights into human thought through allowing participants to articulate their experience in multiple manners. Phenomenology involves specific methodologies and steps to uncover depth of human experience. As such, phenomenologists attempt to uncover the wide range of experiences traversing verbal, emotion, memory and perception, to name a few (SMITH, 2013, §7), to understand the common thread, or essence. To be understood fully, it is paramount then to recognize the range of experiences. [21]

5. Walking through the Study: Steps of Data Collection and Analysis

For this study, I focused on the ways in which visual arts could be used within a transcendental phenomenological philosophical tradition (HUSSERL, 1931; VAN MANEN, 1990) in order to understand the experience of doctoral students. Each woman interviewed had become a mother for the first time while in her doctoral program. At the time of the interviews, each participant had one child. The children ranged in age from six months to six years old. As WANG, COEMANS, SIEGESMUND and HANNES (2017) explain, there are differences between research about art, art as research and art in research. In this case, the visual arts were used as arts in research meaning that they provided a means to an end, supported qualitative inquiry, and as the artist-researcher, I was an insider with knowledge and experience of the topic. [22]

Recognizing that becoming a mother is a sensitive topic, the use of drawings as a form of visual art method was seen as a way to bring insights that could be challenging for participants to express consciously (HAYES & YORKS, 2007, p.96). In this way, I hoped to support participants in sharing their experiences while grasping the harder to reach concepts of new motherhood as a doctoral student. [23]

5.1 Phenomenological interviewing using visual arts

For interviewing, I used SEIDMAN's (1991) protocol that focuses on interviewing each participant three times using a broad set of overarching open-ended questions. I started with the historical situational interview which provided the context of the experience, then transitioned to the second interview discussing relationships relating to the experience, and finally in the third and final interview which addressed reflections about the experience. [24]

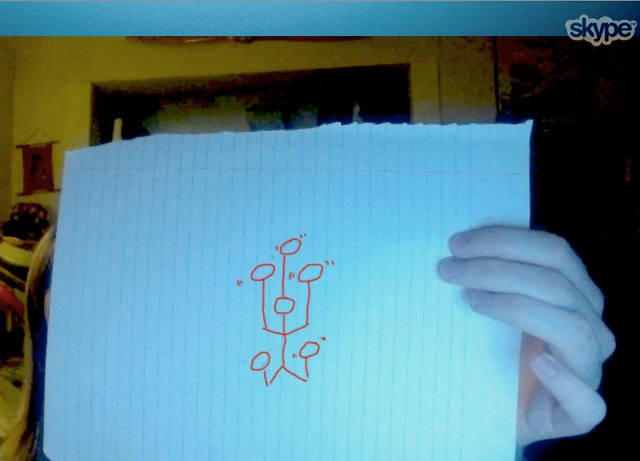

As a supplement to this interviewing protocol, I incorporated visual arts methods within each of the three 1-2 hour interviews by having participants create a subject specific drawing at the end of the interview. (See Table 1 for the questions that guided the interview and drawing elicitation.) [25]

Drawings were requested that related directly to the primary research question. In interview one, when I asked participants to describe the process of becoming a mother in academia, I therefore followed up by asking participants to draw a picture of themselves as a doctoral student mother. As such, I moved a blank 8 ½ x 11" paper to the space in front of the participant and laid the various colors next to it. I then explained that the goal was to represent their ideas about their experiences and not to draw a "beautiful" picture. They could therefore represent themselves in any way they could (e.g., stick figures, colors, black and white, through metaphors, with words, etc.) and thus not to worry about their drawing ability.

|

Interview # |

Transcript A: Guiding Interview Question (guided by SEIDMAN, 1991) |

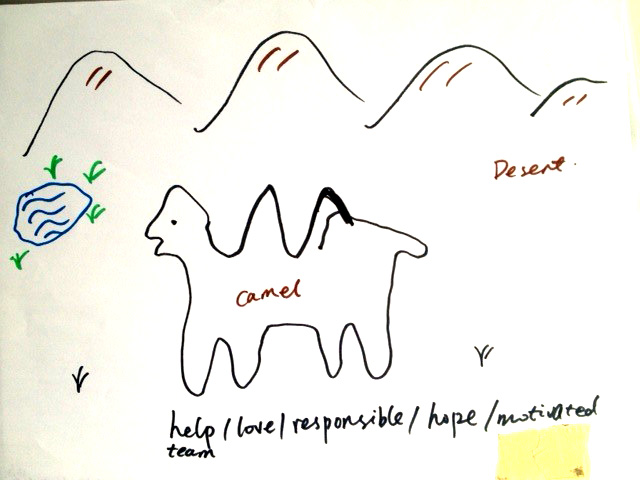

Transcript B: Guiding Question to Elicit a Drawing and Description |

|

Interview 1: History |

Can you reconstruct your journey of becoming a mother while in your doctoral program? |

Draw yourself as a doctoral student mother.

|

|

Interview 2: Relationships |

Can you tell me about your relationships with other people before and after becoming a mother in your doctoral program (e.g., with peers, professors, staff)? |

Think back to the various types of academic situations and all the various academic relationships you have been involved in. Draw yourself as a doctoral student mother in one of these academic interactions. |

|

Interview 3: Reflections |

What have you learned about becoming a mother while in a doctoral program? |

Draw yourself as a doctoral student mother as you see yourself and draw yourself as you think others in academia see you. |

Table 1: Interview questions with guiding question to elicit a drawing and description [26]

After participants had created the drawing I asked the participant, "can you tell me about it?2)" They then explained their drawing to me, noting the importance (or lack of importance) of different components, while I recorded their response for later transcription and analysis. After creating the drawing, the participant was asked to describe her work, a process similar to data creation and discussion as used in photovoice (LEAVY, 2017), but in this case with hand-drawn images. Through this process of integrating visual arts methods in the three interviews conducted with each of the four participants led to a total 12 interviews and 13 drawings created by participants (one participant spontaneously created an additional drawing during the interview). [27]

5.2 The participants: DocMamas sharing experience

Doctoral student mothers—"DocMamas" (COHENMILLER, 2014b)—were recruited from a Hispanic serving institution (HSI)/research university in the Southwest, United States. Within the university, there were five colleges that enroll doctoral students from which participants were selected based upon a common phenomenological approach of criterion sampling (CRESWELL, 2007). I sought women who were currently enrolled in different departments/colleges who had become mothers for the first time while in their doctoral program of study. By selecting participants from various colleges across the same university, I expected to gain greater breadth about the overall phenomenon. [28]

After proceeding through the ethical review board procedures, participants were located through discussions with contacts at the university across the five colleges enrolling doctoral students: business, education, engineering, natural sciences, and social sciences. However, there were no potential participants who met the criteria within engineering, as I had been told that all new mothers had recently graduated. I contacted faculty and staff across the remaining four colleges and inquired about their knowledge/enrollment of doctoral students who had become mothers while in their program of study. If a potential participant was identified, the faculty or staff member forwarded to the student a recruitment letter via e-mail. Those who were interested in participating were asked to e-mail me. [29]

As a part of the consent form, it was explained how each participant would receive a pseudonym to assist in protecting confidentiality and that they could withdraw from the study at any point. While five participants e-mailed indicating their interest in joining the study, one withdrew prior to beginning the study. Participants (DocMama1, DocMama2, DocMama3, DocMama4) were told that the process would involve filling out a questionnaire and taking part in three interviews in which they would answer questions and draw pictures relating to being a doctoral student mother. Interviews were conducted over the course of four months and began as soon as the first participant was identified. Each interview was digitally recorded and transcribed. For three of the four participants, the interviews were conducted face-to-face, at the university campus. For DocMama3, from the natural sciences, one interview was conducted face-to-face and two interviews were conducted via Skype due to her moving out of town. [30]

5.2.1 DocMama1: A business major with one child

The drawings provided multiple opportunities and insights within the interviews. For some interviews, drawing was a prompt for the participant to talk about additional details of the experience. Through drawing, participants created another means of articulating their thoughts and sharing them (see Figure 1).

Figure 1: "Doctoral student/mother"— Representation of being a doctoral student mother (Drawing by DocMama1) [31]

For example, DocMama1, a business major who was married with one young child at the time, spoke easily and at length when asked to talk about her experience of becoming a mother for the first time in a doctoral program. Over the course of approximately an hour and a half, she described her experience of becoming a mother. As she finished her explanation, I asked her to draw a picture to represent herself as a doctoral student mother. [32]

At this point, I was not sure what would come of the drawings. Would there be anything additional for her to talk about? Would she be okay with spending time drawing after the time she had already spent talking about her experience? Would the drawings present new insights? My questions were soon answered. After approximately fifteen minutes of concentrated drawing using a variety of colored Crayons, DocMama1 finished her drawing with a satisfied smile, gazing at her depiction. In the center of the page was a large stick figure with pigtails, curly pink circles in the head, a big red heart in the chest, and in one hand of the figure, a tiny stick figure with matching pigtails. Behind the stick figures were drawn wavy multi-shaded blue lines and a bright yellow sun on the far right of the page with the words, "Sun shines on BOTH." Throughout the page were multiple words and explanations. At the top of the page on the far top left were written "doctoral student/mother." Pointing to the top of the primary stick figure was a large green arrow emerging from a green text box with the following words,

"Student

(20% time/focus/energy)

FUTURE focus" [33]

Above these words was a bulleted list written in black:

"work on dissertation

go to conferences

publish

research meetings

teaching

grading

writing" [34]

A similarly large green arrow pointed to the heart center of the stick figure with the following words within a green text box:

"Mom

(80% time/focus/energy)

PRESENT focus" [35]

On the opposite side of the stick figure in the lower left section of the image, there was another bulleted list of words written in black, apparently referencing the "Mom" text box:

"Stroller Strides [a class where mothers bring their strollers and babies to complete exercises]

stay at home friends

children's museum membership

birthday parties

mom's night out/mom friends—flowering friendships!

-> running again! (for me) <-

cooking (vegan lifestyle)

cooking good healthy foods for baby" [36]

When asked to tell me about what she had created, DocMama1 explained that she felt like she was struggling as if she were a swimmer with a heavy weight to manage the balance between graduate school and mothering,

"So there's this sense that I'm swimming through it all [grad school and being a mother], but that I now carry her [my daughter] while I swim. Which is like ... a lot harder of a way to swim, but that it [carrying my daughter] makes it [school] better ... " [37]

She continued to explain that while it was hard to do everything, she felt very positive about life in general since having a child, "so my sunshine [in the drawing] is that it's everything ... it's like plusses and better because now, because now, I'm swimming for a reason." DocMama1 explained that becoming a mother had put her life in perspective. She pointed and described each section of the drawing saying that having a child

"puts it [life] all into perspective, which I get some things I never had before, that makes this [points to the school side of the drawing] richer, and makes [points to the student side of drawing] more of a break and a thing I enjoy more than I realized I enjoyed because it wasn't rare." [38]

Through pointing at the drawing and each individual section, DocMama1 described aspects of her feelings that she had not yet mentioned in her earlier portion of the interview. She described her drawing further and explained that doing the PhD was a "make it or break it" experience and once she had become a mother, made her cherish each part of her life more:

"You know I loved it. I loved that 'Captain grad student' [being the best] kind of view [of myself]. But now that it's rare and I don't get to do it all the time, it makes me realize I do want to spend time getting in the flow [of academic work]. I do love my writing. And she [my daughter] reminds me of that in a way, I don't know if I had lost touch with it, but I didn't know it was so precious until I didn't get to have it, right?

I feel like I've always been swimming and trying to be a good person and a good grad student. She [my daughter] makes it harder but better." [39]

The amount of descriptive material to unpack was immense and richly filled with information about the experience of becoming a doctoral student mother. While similar information could have potentially been elicited from additional interviewing, the opportunity to draw appeared to create a different space to speak about less visible aspects of the experience. [40]

Prior to drawing the picture, DocMama1 spoke about the details of becoming a mother and about the practical aspects, such as who was supportive and in what ways, where she found a location to pump milk, and what her colleagues said in reaction to her news. But her deeper feelings and thus her nuanced experience about becoming a mother were only described after she drew the picture. DocMama1 delved into aspects of her experience that included deep feeling and passion about being a mother and a student. Her emotions became palpable as she showed me in colors and then verbal description, how it felt to be a new mother in academia. [41]

5.2.2 DocMama2: A social sciences major, pregnant with her second child

After the first interview, I moved on to a differing experience with DocMama2, a social sciences major who was married with one child and pregnant with a second. Instead of speaking in metaphors and at length like DocMama1, DocMama2 concisely noted her experience of becoming a mother while in her doctoral program within only a few minutes. While I asked follow-up questions, which were all answered succinctly, the feeling of the overall interview changed once she had a chance to draw a picture (see Figure 2).

Figure 2: "This is what everyone thinks I do and this is what I do." Representation of self as doctoral student and mother (Drawing by

DocMama2) [42]

With paper and colored pencils in hand, DocMama2 created her drawing to represent herself as doctoral student and mother. She created a separation on the page with two sides designated by a strong black line and a semi-circle at the top of the page hanging over both portions. On the left hand side, there was a drawing of three people who she explained to be her husband, herself and her child kicking a ball. DocMama2's representation involved a woman with hair sticking up erratically, arms outstretched above her head and a large smile spread across her face. On the right hand side, the image is of a person, wearing a long skirt, with long, kempt hair and arms calmly at the sides of the body. The top of the image with the semi-circle has squiggly blue lines and a small circle with a smile at the top. When asked to tell me about the picture, DocMama2 explained that she created multiple images to represent what others think she does as an academic, what her parents think she does, and what she really does:

"So I view this [the drawing] sort of as, well over here [on the right side] is sort of the academic side of me ... and I'm feeling poised... and like I'm doing my job. And mature. But there is a big line here, separation [in the middle of the drawing]. And this one over here [on the left] is representing me with my husband and my son, playing. And my hair is all over the place because I'm a bit frantic, but I'm very happy. Not to say that I'm not happy over here [on the academic side]. But I'm very happy in that environment [at home].

But again, I feel like this divide [in the picture] is that going back to 'what my parents think I do, what everyone else thinks I do, what I really do' because I feel like many people who know me well, view this [my life] as a very separated existence. That when I am in an academic setting, I am in an academic setting and I compartmentalize and I approach things from a very different perspective than when I'm at home, having fun, with my kids. And people on both sides of that line think this as well." [43]

While DocMama2 detailed how her picture showed what others thought of her being a mother and a doctoral student, the emotional and deeper context of her experience came through when she began describing her actual experience:

"But this part up here [at the top of the drawing], which is very figurative, that's where I feel that I am. And what I see this as, is sort of, bringing them [the academic and family] both together. I love water, it calms me [referring to the picture of the waves she is in] and I feel like even though this seems very hectic [pointing to the picture of her with her family] and crazy, because it's what I want to do, I find it calming. Which is why I drew water. This is me keeping my head above water. I am just barely keeping my head above water [laugh] ... but that is okay, because I am happy. The smiley face is happy." [44]

Prior to creating the drawing, DocMama2 was quite succinct in her description of becoming a mother. She detailed the framework of which semester she became pregnant, how her colleagues responded, and how she managed the practical aspects of who took care of the baby while she was studying. She did not describe any struggles she faced and there was little that she was trying to keep her "head above water." There was a clear change from detailing the "shopping list" (GUENETTE & MARSHALL, 2009, p.86) to expanding upon and discussing the experiences in-depth. After creating the drawing, DocMama2 began to describe her feelings, touching upon a willingness and thus more nuanced explanation of her experience as challenging, to balance everything yet enjoying the process at the same time. [45]

The literal physical and emotional space of creating a drawing appeared to support an increased ease of interaction. Perhaps the affordance of a pause in the interview process for creating the drawing as a type of stress reducer (SANDMIRE, GORHAM, RANKIN & GRIMM, 2012) or a chance to collectively gaze at a separate item (not having to look at one another's eyes), appeared to support DocMama2 in thinking about and sharing her experience. [46]

5.2.3 DocMama3: A science major with one child

The first interview with DocMama3, a science major who lived out of town with her young child, I conducted via Skype. This meant that instead of being able to arrange a space allowing for quiet discussion with paper and colors available, I had to rely on the participant's ability to create a space that was conducive for interviewing. The timing was arranged easily and plans for the interview and coloring were made. However, the quiet space and access to coloring materials was not as simple as we had both anticipated. Ultimately, DocMama3 participated in the interview in the living room of her parent's home while her father worked to take care of her toddler who often came into the living room. For the drawing part of the interview, DocMama3 quickly found a piece of lined paper and a pen (see Figure 3).

Figure 3: Spinning plates. Representation of being a doctoral student mother (Drawing by DocMama3) [47]

The initial amount of description and explanation about the experience of becoming a mother in the doctoral program was presented in a structured way that included minimal details about the change in her life. After follow up questions which elicited minimal additional information, I moved to having DocMama3 draw a picture to represent herself as a doctoral student mother. After a quick couple of minutes, where she looked down at the paper while I engaged myself in other work as our computers remained on, she returned with a simple line drawing. She held her drawing up to the computer screen for me to see and take a photograph of. At first, I was once again unsure if the drawing would allow for more insights. This time I felt concern about the speed at which the drawing was created and that we were not face-to-face. [48]

In the image, there was a stick figure with no facial features but instead sticks emerging from the hands, legs, and one on top of the head, with circles on top of each stick. Along the side of four of the circles were double lines indicating movement. After seeing the image, I asked DocMama3 to explain it. She described the struggle she feels in trying to balance everything in her life, like trying to keep a hold of many spinning plates:

"It's like you have a bunch of different ... plates. Some are cheap plates and some are very expensive plates and [my daughter] would be a really expensive plate I guess [laughs] and you've got to decide where to put all the different plates and keep them spinning and keep everything going. Um, despite everything else that's going on I guess. Just trying to stay focused on keeping everything going." [49]

My initial concerns about the benefit of a quickly drawn image were put to rest. DocMama3 continued describing her experience, mentioning how she felt before she became pregnant in comparison to that day, "I think I did feel a little similarly [to the current image], but I think I was like, "there are two plates" and so I was like "this is kind of easy, oh I'll just put this plate in the cabinet for a little while" [laughs]." She explained how in being in the doctoral program with a child she felt much more pressure, "it's like 'oh crap, I've got to do this, and this and this and this.' Make sure I'm keeping track of everything." [50]

In DocMama3's explanation of the drawing, she expanded upon her experience of being a mother in her program, detailing aspects that were not previously mentioned, becoming more at ease, and describing the extreme challenges of managing it all, "I think it didn't seem as hectic as it did before. I thought it was hectic, but now it really seems like hectic in comparison." In this way, through the use of creating a simple drawing, DocMama3 was able to tap into her feelings about how it felt to become a mother, providing nuance that was not previously discussed. [51]

5.2.4 DocMama4: An education major with one child

DocMama4 who was a non-native English speaker from China detailed many aspects about her experience, feelings and concerns about becoming a mother while in her doctoral program in education. For instance, she explained her caution in telling her doctoral advisor about being pregnant. DocMama4 noted her concern that she would have to leave the program, a common occurrence in China she explained, but was happily surprised in the US, "the program [was] very warm and welcoming, they said 'Congratulations! We will prepare a cubicle for you, a baby cubicle.' It's okay. They were supportive and they [wanted to throw a] party 'bring baby, bring baby' " (see Figure 4).

Figure 4: Camel with an oasis in the distance. Representation of self as doctoral student and mother (Drawing by DocMama4)

[52]

After her explanations, I asked her to draw a picture to represent herself as a doctoral student and mother. As she had already provided a broad description of her experience, it was unclear how much additional information would be provided with the incorporation of a drawing. When DocMama4 began her depiction, she chose the colored markers and began drawing. Within a few minutes, she happily showed me her picture. In the middle of the page was a black line drawing of a Bactrian camel [a two humped camel indigenous to Central Asia] with the word "camel" written in the middle. Behind the camel were black line drawings of mounds with brown double lines within each, with the word "desert" written to the far right of the page. On the far left within the desert was a small blue circle with curvy lines within and four small green grasses/plants. To each side of the camel was a black grass/plants and beneath the camel the words "help / love / responsible / hope / motivated / team." [53]

When asked to tell me about the drawing, DocMama4 explained the metaphor of a camel as representative of herself. Her description provided a new aspect of her experience, one that related to additional nuance of her feelings of being a mother and a doctoral student. DocMama4 mentioned the responsibility she felt as represented by the camel, "The responsibility to the work, working and family for the people ... Responsibility. I feel more responsible than before." She continued to explain that she felt different than she did before having a child, again providing aspects of her experience that she had not fully expanded upon before creating the drawing. DocMama4 described that she felt in helping the family, "Before I was maybe just a horse, like run faster, to be the first one. Always be the first one to be the best ... how you [can] make all the family happy, good." [54]

After drawing the camel and explaining how it represented herself, I came to see an understanding of the weight she felt as a doctoral student mother. In this case, even with an extensive initial amount of descriptive details in the interview, the imagery provided further depth of understanding and subtle experience that allowed her voice to further shine through. [55]

Overall, for all participants, I noticed a vivid change in depth or breadth of description within their experience. As EISNER (2006) explains of the ability of the arts in research, "[t]he arts provide access to forms of experience that are either un-securable or much more difficult to secure through other representational forms" (p.11). For DocMama1 who easily spoke about her experience, the addition of drawing demonstrated nuance previously unmentioned resulting in an exceptionally clear picture of her experience of becoming a doctoral student mother. For DocMama2 who was hesitant to share details about her experience, drawings appeared to provide an outlet for her to focus on while speaking that eased the interaction between us as researcher-participant, increasing our rapport. Likewise, for DocMama3 who spoke succinctly and directly, her drawings helped me better understand her feelings, adding clarity and additional depth related to the experience. Furthermore, for DocMama4, a non-native English speaker, being able to draw appeared to provide a way to explain her experience through metaphors that she could show in the imagery and then describe in full detail. In the end, for the participants creating visual arts through drawing not only facilitated communication and understanding but also more importantly, encouraged participant voice. [56]

In deciding to engage in a phenomenological study using multiple in-depth interviews with each of the participants, I went on a journey—a journey to see the lives of others. Through using visual arts methods—having participants draw pictures as a part of each interview—I was able to literally and figuratively see the experiences described. I found that through the process of creating the drawings (e.g., pauses to draw, physical materials to develop, thought process to create) and also in discussing the created images, the participants and I were able to reach a deeper level of communication and understanding. The use of visual arts supported the participants to communicate their ideas in ways that may have not emerged without many additional interviews, if at all. Thus, drawings as a visual arts method used within a transcendental phenomenological study provide a way to enable, encourage and support participant voice, in particular when researching sensitive topics. [57]

Using visual arts elicitation allowed for a depth of feeling and experience as seen before and after participants created and explained their drawings. For the four participants, I saw drawings as providing insights that helped communicate their ideas to me as the researcher and for themselves in articulating their experiences. Through seeing participant drawings, it is possible for a researcher to quickly see the experience, in this case facilitating an understanding of the experiences of doctoral student mothers in academia. The drawings provided an outlet for allowing the voice of participants to come through, including showing experiences ranging from challenges, dynamic relationships, burdens, and joys, all presented in visual form. [58]

Could this depth of description ultimately have resulted from additional interviews? Perhaps. Yet I saw across all interviews with each participant that additional comfort, ease, and feeling were provided only after offering the chance to create a drawing. Creating drawing allowed participants to access their voice, speaking about their feeling and articulating their experiences in nuanced and subtle ways not previously mentioned. For others who are considering additional phenomenological tools, it appears that visual arts methods can provide a valuable benefit to encourage participant voice and understanding. In the future, additional studies could explore further aspects of integrating visual arts methods within phenomenology, such as the timing of when to elicit a drawing, using other art forms, having the researcher analyze the artwork, and the potential limits of the method. [59]

I would like to thank Katja MRUCK and the anonymous reviewers of FQS for their detailed feedback that has greatly contributed to enhancing this article. I also received valuable suggestions on earlier related concept papers from participants at the Sociologists for Women in Society (SWS) conference and from Jennifer WOLGEMUTH through her mentorship as part of the Qualitative Research SIG of the American Educational Research Association (AERA).

1) A/r/tography is the integration of arts in educational research. "A/r/t is a metaphor for artist-researcher-teacher" (LEAVY, 2009, p.3). <back>

2) The choice of words was important to the process of the drawing. By asking for the participants to "tell me" about the image, instead of "describe it" I hoped to encourage the participants to describe the aspects they felt important to explain about the image instead of an externally required description of each aspect. <back>

Chung, Yunjeong (2015). Cross-cultural adaptation in the discourse of education and motherhood: An autoethnography of a Korean international graduate student mother in the United States. PhD Dissertation, Pennsylvania State University, Philadelphia, PA, USA.

CohenMiller, Anna S. (2014a). Drawing motherhood: Presentation of self as mother and academic. Paper presented at the Sociologists for Women in Society conference, Nashville, TN, USA, February 6-9, 2014.

CohenMiller, Anna S. (2014b). The phenomenon of doctoral student motherhood/mothering in academia: Cultural construction, presentation of self, and situated learning. PhD Dissertation, University of Texas at San Antonio, San Antonio, TX, USA, https://media.proquest.com/media/pq/classic/doc/3372828831/fmt/ai/rep/NPDF?_s=K%2BHEqpwwXKnDBxdng7kzGS9sw7w%3D [Accessed: November 24, 2017].

CohenMiller, Anna S. (2016a). From the inside out: An ethnographic arts-based study of mother-scholars. Paper presented at the European Conference on Educational Research (ECER), Dublin, Ireland, August 22-26, 2016.

CohenMiller, Anna S. (2016b). Artful research approaches in #amwritingwithbaby: Qualitative analysis of academic mothers on Facebook. LEARNING Landscapes, Special Issue, Artful Inquiry: Transforming Understanding, 9(2), 181-196.

CohenMiller, Anna S. & Demers, Denise (2017). The ambivalence of being neither fully at work nor fully at home: Arts-based participatory action research with motherscholars to enhance wellbeing. Paper presented at the International Congress of Qualitative Inquiry (ICQI), Champagne-Urbana, IL, USA, May 17-20, 2017.

Coholic, Diana A. & Eys, Mark (2016). Benefits of an arts-based mindfulness group intervention for vulnerable children. Child and Adolescent Social Work Journal, 33(1), 1-13.

Coholic, Diana A.; Cote-Meek, Sheila & Recollet, Debra (2017). Exploring the acceptability and perceived benefits of arts-based group methods for Aboriginal women living in an urban community within Northeastern Ontario. Canadian Social Work Review / Revue Canadienne de Service Social, 29(2), 149-168.

Creswell, John W. (2007). Qualitative inquiry and research design: Choosing among five approaches. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Demers, Denise (2014). "I am the captain of the ship": Mother's experiences balancing graduate education and family responsibilities. PhD Dissertation, Southern Illinois University Carbondale, Carbondale, IL, USA.

Dewey, John (2005 [1934]). Art as experience. New York: Perigree Books.

Eisner, Elliot W. (2006). Does arts-based research have a future?. Studies in Art Education, 48(1), 9-18.

Eisner, Elliot W. (2008). Persistent tensions in arts-based research. In Melissa Cahnmann-Taylor & Richard Siegesmund (Eds.), Arts-based research in education: Foundations for practice (pp.16-27). New York: Routledge.

Eurostat: Statistics Explained (2017). Number of tertiary education students by level and sex, 2015 (thousands), http://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics-explained/index.php/Tertiary_education_statistics [Accessed: July 12, 2017].

Gschwandtner, Christina M. (2014). Revealing the invisible: Henry and Marion on aesthetic experience. The Journal of Speculative Philosophy, 28(3), 305-314.

Guenette, Francis & Marshall, Anne (2009). Time line drawings: Enhancing participant voice in narrative interviews on sensitive topics. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 8(1), 85-92, http://journals.sagepub.com/doi/abs/10.1177/160940690900800108 [Accessed: November 1, 2017].

Harvánková, Klára & CohenMiller, Anna S. (2017). Motherhood at the beginning of a scientific career: A case study in the Czech Republic. Paper presented at the European Conference on Educational Research (ECER), Copenhagen, Denmark, August 22-25, 2017.

Hayes, Sandra & Yorks, Lyle (2007). Lessons from the lessons learned: Arts change the world when … New Directions for Adult and Continuing Education, 116, 89-98.

Haywood Rolling Jr., James (2013). Arts-based research primer. New York: Peter Lang Publishing.

Heidegger, Martin (2002 [1950]). Off the beaten track—The origin of the work of art (ed. and transl. by J. Young & K. Haynes.). New York: Cambridge University Press, http://users.clas.ufl.edu/burt/filmphilology/heideggerworkofart.pdf [Accessed: September 16, 2017].

Hogan, Susan (2015). Mothers make art: Using participatory art to explore the transition to motherhood. Journal of Applied Arts & Health, 6(1), 23-32.

Holden, Cathie; Joldoshalieva, Rahat & Shamatov, Duishon (2008). "I would like to say that things must just get better": Young citizens from England, Kyrgyzstan and South Africa speak out. Citizenship Teaching and Learning, 4(2), 6-17.

Husserl, Edmund (1931). Ideas (transl. by W.R. Boyce Gibson). London: George Allen & Unwin.

Knowles, J. Gary & Cole, Ardra L. (Eds.) (2008). Handbook of the arts in qualitative research: Perspectives, methodologies, examples, and issues. Los Angeles, CA: Sage.

Kulp, Amanda M. (2016). The effects of motherhood during graduate school on PhD recipients' paths to the professoriate. PhD Dissertation, University of Kansas, Lawrence, KS, USA.

Laney, Elizabeth K.; Lewis Hall, M. Elizabeth; Anderson, Tamara L. & Willingham, Michele M. (2015). Becoming a mother: The influence of motherhood on women's identity development. Identity, 15(2), 126-145.

Lawrence-Lightfoot, Sara & Davis, Jessica Hoffman (1997). The art and science of portraiture. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Leavy, Patricia (2009). Method meets art: Arts-based research practice. New York: Guilford Press.

Leavy, Patricia (2015). Method meets art: Arts-based research practice (2 ed.). New York: Guilford Press.

Leavy, Patricia (2017). Research design: Quantitative, qualitative, and mixed methods, arts-based, and community-based participatory research approaches. New York: Gilford Press.

Mason, Mary Ann (2009). Why so few doctoral-student parents?. The Chronicle of Higher Education, http://chronicle.com/article/Why-So-Few-Doctoral-Student/48872/ [Accessed: April 2, 2017].

Mason, Mary Ann; Wolfinger, Nicholas & Goulden, Marc (2013). Do babies matter?: Gender and family in the Ivory Tower. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press.

Mayer, Audry L. & Tikka, Paiva M. (2008). Family-friendly policies and gender bias in academia. Journal of Higher Education Policy & Management, 30(4), 363-374.

O'Donoghue, Dónal (2009). Are we asking the wrong question in arts-based research?. Studies in Art Education: A Journal of Issues and Research, 50(4), 352-368.

Okahana, Hironao; Feaster, Keonna & Allum, Jeff (2016). Graduate enrollment and degrees: 2005-2015. Washington, D.C., http://cgsnet.org/ckfinder/userfiles/files/Graduate_Enrollment Degrees Fall 2015 Final.pdf [Accessed: August 29, 2017]

Philipsen, Maike Ingrid (2008). Challenges of the faculty career for women: Success and sacrifice. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Pink, Sarah (Ed.) (2012). Advances in visual methodology. London: Sage.

Sallee, Margaret; Ward, Kelly & Wolf-Wendel, Lisa (2016). Can anyone have it all? Gendered views on parenting and academic careers. Innovative Higher Education, 41(3), 187-202.

Sandmire, David A.; Gorham, Sarah R.; Rankin, Nancy E. & Grimm, David R. (2012). The influence of art making on anxiety: A pilot study. Art Therapy, 29(2), 68-73.

Seidman, Irving (1991). Interviewing as qualitative research. New York: Teachers College Press.

Smith, David Woodruff (2013). Phenomenology. In Edward N. Zalta (Ed.), The Stanford encyclopedia of philosophy, https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/phenomenology/ [Accessed: August 10, 2017].

Southwest Popular/American Culture Association (2017). Call for papers, 39th SWPACA annual conference, http://southwestpca.org/conference/call-for-papers/ [Accessed: March 7, 2017].

Stickley, Theo; Parr, Hester; Daykin, Norma; Clift, Stephen; De Nora, Tia; Hacking, Sue; Camic, Paul M.; Joss, Tim; White, Mike & Hogan, Susan J. (2016). Arts, health & wellbeing: Reflections on a national seminar series and building a UK research network. Arts Health, 9(1), 14-25.

Swarts, Susan Elaine (2016). Socialization experiences of doctoral student mothers: "Outsiders in the sacred grove" redux. PhD Dissertation, University of California, Los Angeles, CA, USA, https://escholarship.org/content/qt9sz3x0fd/qt9sz3x0fd.pdf?nosplash=4ec6f19880f4bbf7333bf1c5a7799f10 [Accessed: November 24, 2017].

Tiu Wu, Aimee (2013). Learning to balance: Exploring how women doctoral students navigate school, motherhood and employment. Ed.D. Dissertation, Teachers College, Columbia University, New York, NY, USA.

Trepal, Heather C.; Stinchfield, Tracy A. & Haiyasoso, Maria (2014). Great expectations: Doctoral student mothers in counselor education. Adultspan, 13(1), 30-45.

Tucker, Amber (2016). Talkin' back and shifting black: Black motherhood, identity development and doctoral study. PhD Dissertation, University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee, Milwaukee, WI, USA, https://dc.uwm.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=2430&context=etd [Accessed: November 24, 2017].

van Manen, Max (1990). Researching lived experience: Human science for an active sensitive pedagogy. London: The University of Western Ontario.

Wang, Qingchun; Coemans, Sara; Siegesmund, Richard & Hannes, Karin (2017). Arts-based methods in socially engaged research practice: A classification framework. Art/Research International: A Transdisciplinary Journal, 2(2), 5-39, https://journals.library.ualberta.ca/ari/index.php/ari/article/view/27370 [Accessed: October 2, 2017].

Ward, Kelly & Wolf-Wendel, Lisa (2017). Mothering and professing: Critical choices and the academic career. NASPA Journal About Women in Higher Education, 10(3), 1-16.

Wolfinger, Nicholas H.; Mason, Mary Ann & Goulden, Marc (2008). Problems in the pipeline: Gender, marriage, and fertility in the ivory tower. The Journal of Higher Education, 79(4), 388-405.

Zhang, Qisi (2011). An exploration of the identities of Asian graduate student mothers in the United States. PhD Dissertation, Indiana University of Pennsylvania, Indiana, PA, USA, http://knowledge.library.iup.edu/etd/689/ [Accessed: June 16, 2017].

Anna S. COHENMILLER, PhD, is an assistant professor in the Graduate School of Education at Nazarbayev University in Kazakhstan. Specializing in interdisciplinarity and arts-based qualitative methods, her research centers on gender, diversity and access. Current research includes such topics as interdisciplinarity in collaborative teams, the gendered nature of organizations, and recruitment/retention of graduate student parents in academia. COHENMILLER is also the Founder of The Motherscholar Project and Editor-in-Chief of Dialogue: The Interdisciplinary Journal of Popular Culture and Pedagogy.

Contact:

Anna S. CohenMiller

Graduate School of Education

Nazarbayev University

53 Kabanbay Batyr Avenue, C3, 5005

Astana, Kazakhstan, 010000

E-mail: anna.cohenmiller@nu.edu.kz

URL: https://annacohenmiller.academia.edu

CohenMiller, Anna S. (2018). Visual Arts as a Tool for Phenomenology [59 paragraphs]. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung / Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 19(1), Art. 15, http://dx.doi.org/10.17169/fqs-19.1.2912.