Volume 21, No. 2, Art. 6 – May 2020

You Want Me to Draw What? Body Mapping in Qualitative Research as Canadian Socio-Political Commentary

Lisa McCorquodale & Sandra DeLuca

Abstract: There is a scarcity of literature written about body mapping as a method to understanding mindfulness practice, and even fewer examples of how to undertake this type of research in a tangible way. In this article, we discuss how body mapping was used as part of a qualitative study investigating working mothers' mindful practices. We present a novel approach to integrating mindfulness-based techniques with SOLOMON's body mapping method. We illustrate our experiences by 1. sharing an overview of body mapping as a method, and 2. reviewing practical issues we encountered including: a) ethical issues, b) how to approach analysis, and c) body mapping within social research. Body mapping can be a fun and expressive experience for participants of social research. It can also be a confusing and overwhelming experience for researchers and participants new to the method. Through the article, we offer some insights and assurances about how to proceed with body mapping projects, including details such as how to generate questions for body mapping sessions, and a thorough consideration of steps to consider for analysis.

Key words: body mapping; visual data analysis; arts-based inquiry; mindfulness; qualitative methods; ethics

Table of Contents

1. Introduction: The Body in Qualitative Research

2. Body Mapping

3. Study Procedures and Theoretical Framework

4. Practical Considerations

5. Ethical Considerations

6. Analyzing Body-Maps

7. Body-Mapping's Contribution to Social Research

7.1 Rich data

7.2 Socio-political critique

8. Limitations and Quality Assessment

9. Conclusion

1. Introduction: The Body in Qualitative Research

"My body has always been a question mark. Never quite knowing what it means. To be alive" (SURESH, 2016, §810).

As this opening statement suggests, the body is an oft-neglected entity. The body in qualitative research is particularly absent, with many qualitative methods relying on cerebral and intellectual data collection and analysis (PROSSER, 2011). Additionally, projects are commonly designed to either emphasize the mind (i.e., cognitive and linguist representations) or the physical body (i.e., objective biologically based scientific exploration), but the lived body, also worthy of serious philosophical and empirical investigation, is ignored (MUNHALL, 2012). Further, the body as a source of investigation is often an add-on to interview-based data methods rather than the primary source of data (DREW & GUILLEMIN, 2010). Alternatively, the lived body offers the opportunities to attune to ways humans think, feel, taste, touch and hear the world (MUNHALL, 2012). Body map storytelling (SOLOMON, 2002) is a research method that might access these experiences and is our focus in the remainder of this article. [1]

As a child, Lisa the first author could spend hours combing through old photo albums. Being drawn to images is perhaps part of what makes us human. Not surprisingly then, she selected a visual method, body-map storytelling, for her PhD dissertation. The study was a phenomenological investigation about what mindfulness practice means to working mothers with young children. We had a particular interest in how mindfulness practices support the health and well-being of working mothers and their families. Lisa and Sandra, the second author and project supervisor, met with seven women to better understand what it is like to mother young children while crafting interesting and meaningful careers. We are both acutely aware of social institutions and discourses that can make mothering while working complicated. [2]

Each of the women had a mindfulness practice, cultivated through formal intentional focus (e.g., seated meditation) or more informally through noticing daily life (WISE & HERSH, 2012). Mindfulness can be thought of as the process of "paying attention in a particular way; on purpose, in the present moment, and nonjudgmentally" (KABAT-ZINN, 2005, p.145). Our aim in this project was to understand how mindfulness is implicated in working mothers' day-to-day lives and we had many "lived body" questions. For example, how does mindfulness allow mothers to see their children and their work differently? How does it make them touch or move differently in the world? How do their experiences get expressed in their bodies? Further, we were aware that gaining an appreciation for how mindfulness is expressed in the body could lend additional insight into its value as a practice and wanted to select a method worthy of this potentiality. [3]

We have two aspirations in this article. First, we aim to foster the uptake of body map storytelling within qualitative health research. Second, we illustrate our experiences with body mapping by specifically, sharing an overview of body mapping as a method (Section 2), describing our study procedures (Section 3), reviewing practical issues encountered during the project (Section 4), considering ethical issues unique to body mapping (Section 5), exploring how we approached analysis (Section 6), and situating body mapping within social research (Section 7). [4]

Body maps are life-size human body images created by

"[u]sing drawing, painting or other art-based techniques to visually represent aspects of people's lives, their bodies and the world they live in. Body mapping can be a way of telling stories, much like totems that are constructed with symbols that have different meanings, but whose significance can only be understood in relation to the creator's overall story and experience" (GASTALDO, MAGALHAES, CARRASCO & DAVY, 2012, p.5). [5]

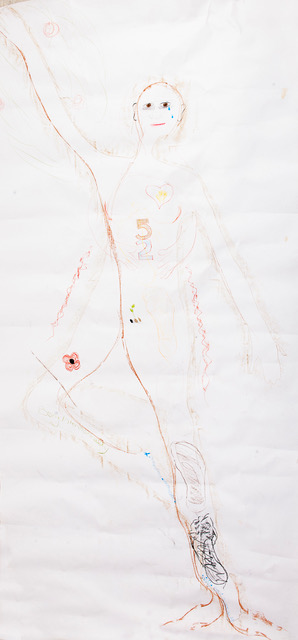

In the study described in this article we used body maps as storytelling (SOLOMON, 2002); as a way of illuminating working mother's experiences with mindfulness. Rather than privileging cerebral activity, body mapping elevates emotion and somatic experience in understanding the workings of "mind" and consciousness. This is particularly true during the body mapping creation phase of the process. Rather than elicit cognitively filtered answers from participates, body mapping encourages non-cognitive responses from participants (see Illustration 1 for a sample body map from this study). Body maps can be completed by individual research participants or collectively in groups (CORNWALL, 1992). The body maps become springboards for discussion to fully understand the lived experiences depicted. These discussions can take place while the maps are being drawn, or afterwards through either one to one interviews or in larger focus groups. In this study we used a combination of all three approaches to develop an understanding of the women's experiences.

Illustration 1: Sample body map [6]

In a body mapping session, participants trace their body to document their physical and emotional journey (HARTMAN, MANDICH, MAGALHAES & ORCHARD, 2011). Body map storytelling has a long history as a therapeutic process (CORNWALL, 1992; SOLOMON, 2002). Its research origins are arguable and there are relatively few published exemplars compared to other visual methods (although exemplars include DEW, SMITH, COLLINGS & DILLON SAVAGE, 2018; GASTALDO et al., 2012; MacGREGOR, 2009; MEYBURGH, 2006). Traditionally, body mapping has been seen as a means to include people who might otherwise be excluded from the research process due to limited literacy, difficulty articulating ideas, or general difficulties in communicating about complex emotions and topics (DREW & GUILLEMIN, 2010). Ideas and issues difficult to explore through verbal discussion alone may be more readily accessed through body mapping (CORNWALL, 1992). [7]

Body mapping was initially described by CORNWALL in her work with women in Zimbabwe where maps of the body were used to explore women's understanding of anatomy and physiology. Her work was based on MacCORMACK's (1985) seminal research in Jamaica using a drawing technique. Body maps where subsequently used as a way of storytelling life experiences (DE JAGER, TEWSON, LUDLOW & BOYDELL, 2016). In particular, the method evolved from the Memory Box Project in South Africa, an art-therapy for women living with HIV and AIDS (MORGAN, 2004). Body maps were used as a therapeutic way for women living with HIV/AIDS to document their stories and provide a keepsake for their families after they passed (e.g., MacGREGOR, 2009). It was then manualized by the Aids and Society Research Unit at the University of Cape Town to better understand women's HIV treatment literacy (CENTRE FOR SOCIAL SCIENCE RESEARCH, 2004). SOLOMON (2002) provided training on the method for body map storytelling facilitators. [8]

From its origins as a means of bringing attention to women's reproductive and HIV-related issues, others have brought the method to diverse populations, and with diverse intents. For example, ORCHARD (2017) writes in detail about her research experiences with body map storytelling and vulnerable men living with HIV and the effects of colonialism in two Canadian cities. CRAWFORD (2010) used body maps as a therapy to help adult men in North America better understand traumatic events. LAWS and MANN (2004) effectively showed how powerful body mapping can be in a focus group, noting that the youth in their study named body mapping as a particularly good activity out of a range of activities in a day long workshop; the youth shared that they learned a lot, most notably that others shared their feelings and had similar experiences. It is also typical of the work found in visceral geography which sees the body as the geographical space of inquiry and pays particular attention to how bodies feel internally—sensations, moods, physical states of being—in relation to surrounding spaces and environments within communities (HAYES-CONROY & HAYES-CONROY, 2010). DE JAGER et al. (2016) provide a systematic review detailing the history, development and uses of body mapping across various disciplines. They note, "body-mapping can be used as an interdisciplinary research method across diverse cultures to address critical issues in health and is amenable to sharing information between researchers and the public" (§49). In our study, we used body mapping as a method to understand how mindfulness contributes to the health and well-being of working mothers and their children. To our knowledge no researchers using body map storytelling have explored mindfulness from a phenomenological lens, and this may be a missed opportunity. Like many aesthetic works, body maps are created intuitively. Phenomenologists assume there are two primary modes of conscious processing: the natural attitude and the phenomenological attitude (MORAN, 2018, p.83). Life as it is experienced, not as it is conceptualized, theorized or categorized, is of utmost importance to phenomenologists (MUNHALL, 2012). Most of the time one's body is not presented as an intentional object but is implicit, tacit, or what phenomenologists calls "pre-reflective" (MORAN, 2018, p.83). The body is doubled in the sense that it is both subject and object. Mindfulness meditation practices often seek to reach these pre-reflective meanings (KABAT-ZINN, 2005). We suggest that body mapping can access non-cognitive experiences similar to the insights mindfulness and the phenomenological attitude can bring. While we briefly considered other methods, body mapping struck us as particularly well suited to understand experiences in a pre-reflective manner. [9]

3. Study Procedures and Theoretical Framework

In our phenomenological study we aimed to understand what mindfulness means to working mothers with young children. Each of the women had a mindfulness practice, cultivated through formal intentional focus (e.g., meditation) and more informally through noticing daily life (WISE & HERSH, 2012) (see Table 1 for participant details). Mindfulness is about "paying attention in a particular way; on purpose, in the present moment, and nonjudgmentally" (KABAT-ZINN, 2005, p.145). Mindfulness involves cultivating intention (i.e., the choice of where and how we direct our attention), a particular type of attention (i.e., productively disengaging from moment-to-moment experiences), and particular attitudes—such as non-striving, acceptance, and curiosity (KABAT-ZINN, 2013; SHAPIRO & CARLSON, 2009). The main research question framing this research was, in what ways might a mindfulness practice help women navigate their role as a working mother with young children? [10]

We married critical feminist thought with phenomenological inquiry (COHEN, KAHN & STEEVES, 2000; MUNHALL, 2012). Phenomenology is arguably a critical practice, seeking to separate tradition from lived experience where, "[p]henomenology has the potential to offer a critique of normative perspectives, of master narratives, or of dominant discourses" (PARK LALA & KINSELLA, 2011, p.204). Each wave of feminist thought also provided substantive support to our project (GILLIS, HOWIE & MUNFORD, 2007). First wave feminists or suffragists, those involved in the nineteenth-century women's movement, arose as a reaction to gendered exclusion from political, social, public and economic life. The next generation of feminists, in the 1960's and 1970's focused on issues which significantly impacted women's lives: reproduction, mothering, sexual violence, expressions of sexuality, and domestic labor. The third wave, and increasingly in the fourth wave, intersectionality, or layers of oppression, constitutive of many women's lives is highlighted as critical to equality (ibid.). We align ourselves with these latter waves of feminists (e.g., BUCHANAN, 2013; HEYWOOD, 2005; WALKER, 1995) who suggest that working mothers are in an impossible situation brought about by their social and political realities. Women often abandon self-care as a way to reconcile their personal and economic ambitions while meeting societal expectations of unwavering commitments to her children. Women continue to assume the bulk of childcare responsibility and are often exhausted, conflicted by competing demands, and experience social and economic marginalization (ASHER, 2012). Further, working mothers often find themselves in a rather unfortunate paradox. Working mothers are commonly seen as uncommitted employees and second-rate mothers; yet, women are also criticized if they chose to stay home with their children or opt to not have children at all (BUCHANAN, 2013). [11]

Mindfulness practice has the potential for women to reconsider their social realities and disengage from harmful societal expectations. We completed this research with seven women over the course of 4 months. These women were all white, middle class, and lived in a Canadian urban context in Southwestern Ontario. The participants are reflective of the many thousands of women in developed countries who may relate to the stories they shared.

|

Participant Name (Pseudonym), Age |

Children |

Work Status |

Marital Status |

Mindfulness Practice (formal and informal) |

|

Sally 31 years old |

Daughter 19-months old, expecting second child |

Works fulltime in a social services position |

Married, and spouse works fulltime |

Meditation practice 5-30 minutes, 4-5 days per week since she was a child |

|

Loja 48 year old |

Son 11 years old and daughter 13 years old |

Works a few jobs that equal fulltime work in social services |

Divorced and remarried, has primary shared custody |

Various forms of meditative practices for 36 years; some form of daily practice 5-60 minutes |

|

Sonyia 40 years old |

Son 7 years old and daughter 4 years old |

Works fulltime in a flexible career in both academia and health care |

Married, spouse works full time |

Daily meditation practice 10-45 minutes per day for 11 years |

|

Alicia 41 years old |

Daughters 7 and 5 years old |

Works fulltime in a flexible position in healthcare |

Married, spouse works full time |

Seated meditation 5-7 days per week for 15 years |

|

Joanne 40 years old |

Son 7 and Daughter 5 |

Part-time in health care |

Married, spouse works full time |

Seated meditation 20 minutes per day for 10 years |

|

Nina 39 years old |

Twin girls 6.5 years old |

Works part time in education for 13 years |

Married, spouse works fulltime |

Daily 20-60 minute seated mindfulness meditation for 4 years |

|

Siobhan 39 years old |

Daughters 8 and 5 years old |

Fulltime reduced in health care |

Married, spouse works fulltime |

Daily seated meditation for 15-20 minutes for 15 years |

Table 1: Description of study participants [12]

After gathering relevant demographic information, body-mapping sessions typically begin with participants marking their body outline on large paper, and responding to researcher's questions with markings (refer to Table 2 for the body-mapping questions used in this study). To create these questions, we narrowed and adapted the steps offered by SOLOMON (2002) and GASTALDO et al. (2012).

|

1. Participant(s) trace their body in a position that says something about their lives as women who practice mindfulness, and then highlight their body shape in a material of their choice (e.g., paint, chalk). |

7. Drawing a self-portrait: Participants asked to draw a self-portrait on the face of their body tracing that represents how mindfulness shapes the way they face the world |

|

2. Participant(s) highlight their body shape and hand/foot prints in paint as a way to demonstrate their presence in the world |

8. Creating a personal slogan: Participants create a personal slogan about the strength they receive from their mindfulness practice as a working mother. |

|

3. Drawing where you come from and where you are moving towards: Participants chose and drew a symbol to represent where they are coming from and what their dreams are for the future as a working mother |

9. Marks on the skin: Participants draw on marks that they have on their skin (physical) under their skin (physical or emotional) on their body-map to represent their physical and emotional interaction with the world as a working mother who practices mindfulness |

|

4. Painting in your support: Participants write the names of those who support them as working mothers on their body-map |

10. Participants create a symbol to explain to others what mindfulness means for them as a working mothers |

|

5. Body scanning—marking the power point: Participants visualize the point(s) on their body where mindfulness gives them their power (‘power point') then create a personal symbol to represent them and draw it on the power point |

11. Public message: their message to the general public about why they practice mindfulness as a working mother |

|

6. Creating a personal symbol: Participant draw a symbol on their power point on the map that represents how they feel about themselves and how they think of themselves in the world |

12. Participants decorate the rest of their body-map until they are satisfied that it represents them |

Table 2: Interview questions posed to participants to then be responded to visually on body-maps (adapted from GASTALDO et al., 2012, p.15 and SOLOMON, 2002, pp.13-60). [13]

We found relatively few published articles that explicitly described the process of creating body-maps, particularly for studies exploring mindfulness. Our intention here is to discuss practical and logistical issues we encountered to guide other potential researchers who might like to use body mapping. [14]

Once participants create their body maps they are asked to elaborate on their completed drawings through written answers (e.g., GASTALDO et al., 2012 asked participants to create a narrative to accompany their maps) and/or verbally in the course of a more typical research interview or focus group (e.g., GUILLEMIN & DREW, 2010 met one-on-one with participants). This allows participants to describe and clarify the contents of the body map, and provide a commentary around which the researcher can build their analysis (MAIR & KIERANS, 2007). The body mapping sessions and subsequent interviews are commonly audio-recorded for later transcription. This discussion is a departure from the more intuitive and embodied initial body mapping process where the participant and researcher(s) work together to understand what is depicted, as was done in the seminal work of GASTALDO et al. (2012) and SOLOMON (2002). [15]

Creating body maps is a relatively time intensive process, as such it may be wise to offer participants the choice as to how they would like to complete their maps. We opted to do so knowing our participants had limited time and we chose to honor how they wanted to offer their time to this project. Two women chose to meet for over four hours, and in that time they created their maps, and participated in a group interview where they shared the meanings behind their depictions. Others broke the session up into three separate meetings—two to create the map—and one to discuss the map. Some met in a group setting, and others wanted to work alone. These choices seemed to be practical considerations for the women who reported it would be easier to complete all aspects of the research in one day, rather than carve out time in an already full schedule for two or even three separate meetings. The time commitment required to complete body maps guided the women's choices as to how to complete their maps in this project and respecting their wishes did not impact this projects completion. From our perspective, this variation in body mapping sessions did not impact our analysis and findings, though waiting to discuss after the session seemed to lessen the emotion and passion the women had for their drawings. As such we suggest the time between body map sessions and interviews be less than a week. Most of the women talked while they were creating their maps offering what turned out to be the first stage of analysis. After completing a few body maps sessions, run by Lisa we began to invite discussion during the creation of the maps about what was being drawn and why. We actually found the audio-recorded conversation during the body-map session the most informative. We could gather in-the moment feedback from the women about why they were representing their experiences in a particular way. Some women had almost nothing to share in the interviews afterwards, as the conversations during the body-map sessions were rich and fulsome. The in-the-moment conversations during the body mapping sessions, as well as the interview after the body mapping sessions where both audio-recorded for transcription and analysis. [16]

Issues around ownership are also important to consider. Given the highly personal and emotional nature of our topic, many of the women expressed interest in keeping their maps when we no longer required them. While we were able to accommodate this request, clarity about what is possible with respect to ownership as part of the consent/ascent process is advised based on individual project needs. [17]

Deciding what materials to offer your participants can be challenging. It is important to offer appropriate materials so that experiences and ideas can come to life via words, symbols, or any other markings (see Table 3). An additional research advisor for this project had previous experience with body mapping and guided material selection for the women to choose from. As well, the first author ran a pilot body mapping session with colleagues to gain a sense of how sessions would run before the study began. No two projects will have the same materials list, though some may be more typical such as paint or chalk. For example, we provided wooden two-dimensional figures that could be used to represent children, and also had magazines present that contained images of families given this project focused on mothering. These items would likely be irrelevant for projects with a different focus.

|

Material |

Comments About the Materials |

|

Paper: Large enough to draw a body about 2 meters long |

We used heavy-weight paper cut to 3 feet x 7 feet size from a roll that I obtained at an art supply store, though others have used large cardboard pieces (CENTRE FOR SOCIAL SCIENCE RESEARCH, 2004). |

|

Art supplies: Glue, scissors, colored pencil crayons, markers, pens, washable paint, water, glue, charcoal, colored paper, magazines, beads, 2-dimensional wooden figures |

Once the women selected a medium they were comfortable with they tended to use that throughout their body-map. Many of the women selected charcoal to outline their bodies and this material tended to transfer very easily onto their skin and clothing. In future, we would advise participants to wear washable casual clothing. |

|

Additional materials: Mirror, camera, hand sanitizer and wet wipes, anatomical diagrams, tape recorder, notepad for analytical notes |

Some of the women used the mirror provided while creating their self-portrait as recommended in GASTALDO et al.'s (2012) and SOLOMON's (2002) materials list. The other materials were used primarily for use as researchers. |

Table 3: Material list (italics indicate materials used most frequently by the women) [18]

Last, researchers will need to store, transport and view a variety of data sources including transcribed data from the body map and interview sessions, multiple life-size body maps, field notes, and research journal entries. We encountered some difficulty during the analysis process in that the maps are very large and take up considerable room. The paper we used could be rolled up, but this risked smudging and therefore distorting images that could impact our analysis when chalk or charcoal was used. Transport issues should be considered before attending body-map sessions. For us, a car with large cargo space was needed to safely transport the maps. Further, we had to rent a room at a local library in order to look at all the maps simultaneously during the analysis phase. Researchers will also need a locked office to store their maps, as we did for security and confidentiality. [19]

Here we share ethical considerations that are potentially unique to body mapping research. There is a call for researchers to work "with rather than working on, about or for" participants (LUTTRELL, 2010, p.224). This is a particular strength of body-mapping. MAIR and KIERANS (2007) summarize what they call "draw and write investigation techniques … as 'user-centred', 'bottom-up' and 'participatory'" (p.121), and a technique that dissolves the barriers between the researcher and the researched. Despite this, we had some difficulty getting this body mapping project through institutional review board. Review members were concerned we could be harming participants by researching a deeply personal experience using such a highly reflective method. Alternatively, LAWS and MANN (2004) argue that vulnerable populations have an opportunity to heal when given the chance to explore past experience through body mapping. If undertaken in a supportive and understanding environment, participants have the opportunity to explore life experiences and regain confidence for future possibilities. At its best, PROSSER (2005a) notes that participation can be an important tool out of victimization, passivity and silence. Rather than pose a risk to participants, visual methods like body mapping, when executed thoughtfully, can communicate our deepest feelings. That said, Lisa who was the session facilitator, has a health and counseling background and felt equipped to navigate the potential emotions body mapping sessions can evoke. Each researcher needs to carefully consider their own skills and the vulnerability of participants responding in body mapping sessions. The method may be best suited to researchers with a health and social care background, and formal training in the method is advised. This is particularly relevant to projects working with vulnerable participants who have experienced trauma(s). Regardless, access to counseling support and knowledge of how people experience trauma is advised. [20]

Another ethical issue considered throughout the study related to confidentiality. Participants may be more readily identified based on the images they place on their maps. Visual researchers have ethical standards to uphold and, "an obligation to ensure that confidential information is protected" (PAPADEMAS, 2009, p.253). However, if participants are denied the opportunity to have input into how their information is shared, participatory methods such as body mapping run the risk of paternalism. For example, we encouraged participants to consider confidentiality when recording names of people on their maps. The following conversation with one of the participants describes this issue:

Lisa: "Ok write the names of those who support you as a working mom. You could also write down a law or policy. You will also want to consider anonymity, and protecting people's privacy. So for example would your husband mind if you put his name on your map?"

Participant: "Ok"

Lisa: "So for the last 7 years what has helped you do your role?"

Participant: "So my husband Bill [pointing to his given name she had just drawn on her map]." [21]

Despite our caution to consider whether to include his name she still placed his given name on her map. Several of the women wanted to honor the people who support them and did not want to protect identities. Another participant summarized her feelings about confidentiality when we revisited consent at the end of her body-mapping session: "You know there are first names on here, and not many people would put those names together and those that could?... I don't care. They are close to me and I am honoring them." [22]

Rather than sanitize the maps, we opted to keep the names the women placed onto their maps. Other researchers may opt to blur names during public exhibitions, and we may have done so if leaving identities revealed negative or difficult information about someone who had not given consent. In this case we decided that to honor those who support working mothers, when they themselves identified limited supports, was the right thing to do. Regardless, considering the women consented to their maps being used in a variety of public places including publications and presentations it was worth revisiting consent throughout the body mapping process. Opting to blur or delete names for public exhibitions would run counter to participant wishes. As described in our ethics application, we sought ongoing consent throughout the project. [23]

As the first body mapping session approached, we became increasingly conscious that being asked to produce images, as part of a research project may appear strange. And initially it appeared that our apprehensions were founded. We had a similar experience to GUILLEMIN and WESTALL (2008) in that despite being clearly informed about what the body mapping session would be like, many of the women appeared hesitant to do so during the initial research encounter. Body mapping is the first step in the research encounter, with interview questions coming organically from the drawings and images (GASTALDO et al., 2012). Nearly all participants expressed trepidation about the process and emphasized their lack of artistic ability. We followed GASTALDO et al.'s suggestion to offer magazines and other cut outs for those who did not want to draw. Notably, none of the women chose these materials and virtually each woman ended the session with a completely different sentiment. The following conversation with one of the participants exemplified a typical response. She started her session unsure and appeared anxious:

Participant: "And I can't do this wrong, can I?"

Lisa: "No absolutely not. This isn't about making it look pretty or an artistic exercise."

Participant: "Ok (long pause) ... So is this how you use the paint?" [24]

She ended her session this way: "Even though it's not beautiful it's fun, you are creative and being creative breeds health! This was so fun, I'm so excited about this!" The addition of food and drinks, as well as patience and a supportive atmosphere helped the women warm to the concept, and their initial hesitation became a non-issue soon after the women started sharing their stories through the body maps. [25]

SPENCER (2011) notes that visual data analysis is a balance of inductive processes—allowing the images to speak for themselves—and deductive processes, whereby structuring principles derived from theory are utilized. Although the use of visual research is gaining acceptance, DREW and GUILLEMIN (2010) suggest there is a relative lack of attention directed at how to rigorously analyze visual images. Analysis can be complicated by what KRISTEVA (1980, p.69) calls "prior codes," or "accumulated cultural knowledge." SPENCER (2011, p.19) also warns humans are notorious for falling into ‘trope-like' interpretations, essentially jumping to well-entrenched thoughts, frameworks or metaphors, almost in knee-jerk fashion. To understand latent and less obvious meanings, researchers should be willing to investigate beyond more obvious reading (BANKS, 2007), and understand that no two images will have the same reading—prior experiences are too diverse to reach unanimous understanding (SPENCER, 2011). We relied heavily on both GUBRIUM (2013) and ROSE (2012) to analyze the data and discuss each in turn below. [26]

ROSE (2012) offers a detailed account of qualitative visual data analysis using interpretive concepts of composition, semiology and discourse to provide a rich data-driven exploration of image meanings. Composition relies on interpreting the location and relation of different images on the map. Semiology, or semiotics, is the study of symbols and their meanings. Discourse is concerned with interpreting specific knowledge about the world, which shapes how the world is understood and how things are done in it (ROSE, 2012). While we read ROSE's text prior to beginning analysis, the complexity and richness of the process was partially lost on us until we experienced it for ourselves. It is our intention to offer exemplars from each of her three forms of analysis as possible guides for other researchers, particularly those exploring mindfulness through body map storytelling (see Table 4 for each image described below). [27]

Composition is about the spacing and placement of images on a map (ibid.). There were many instances where these concepts were highly relevant to the women's experiences. For example, one of the participant's maps was heavily concentrated on her head and heart with very little happening in her lower body. In conversation with her it was clear mindfulness strongly influenced her emotionally:

Participant: "I am really aware that there is very little going on down there [point to her legs]. It looks like mindfulness draws me to my core and is very central around my heart on this map. Yes very much so...and this wasn't necessary obvious to me until I started to draw" (see Table 4, Figure 1). [28]

Another participant's map was very bright with rich saturated colors. She stated that this represented how vividly she experiences life because of mindfulness, and in her words felt: "More love of everything so I think this is a cool symbol — just more love [said with emphasis]" (see Table 4, Figure 2).

|

Level of Analysis |

Images from the Participants and Description of Analysis |

|

|

Composition level of analysis |

|

|

|

Semiotic level of analysis |

|

|

|

Discourse level of analysis |

|

|

Table 4: Sample images and level of analysis [29]

Semiology is the study of symbols. ROSE describes both paradigmatic and denotive symbols. Paradigmatic, or culturally representative images or signs, are useful to understand messages on body-maps. For example, many of the women drew peace symbols reflecting the feeling of calm despite chaotic schedules and demands. This iconic image instantly conveys a message about the peace mindfulness offers (see Table 4, Figure 3). Alternatively, denotive images, or images that serve as representations, often need a narrative to fully anchor the participant's meaning. For example, many of the women drew images that depicted pain or difficult emotions including tears, blood and cuts on their skin. After discussion, however, it became clear that the pain and difficult emotions were seen as productive in their lives rather than a challenge or difficulty (see Table 4, Figure 4). [30]

To study discourse is to understand how particular forms of knowledge and formulations about the world get expressed. Foucault might say that discourse disciplines people into thinking and acting in certain ways (ibid.). The women's images seemed to both name and then resist popular discourses. For example, one participant depicted the white picket fence narrative of hetero-normative families but added the words prison to signify her resistance. Additionally, another participant drew her feet standing on a globe rejecting individualistic ways of thinking, saying about the image, "I'm more aware of the community that I want to contribute to" (see Table 4, Figures 5 and 6). [31]

In addition to the work of ROSE described above, we relied on the work of a few others. For example, GRBICH (2012) offers a unique chapter on how to analyze visual data in a way that gets beyond obvious meanings that we also found useful. She identifies one approach called structural analysis. Structural analysis asks, "what is the meaning of these images for participants" (p.208). DREW and GUILLEMIN (2010), building on her work and others (OLIFFE, BOTTORFF, JOHNSON, KELLY & LeBEAU, 2010; OLIFFE, BOTTORFF, KELLY & HALPIN, 2008) offer three analytic stages to highlighting this meaning-making: Participant engagement (Stage 1); researcher-driven engagement (Stage 2); and re-contextualizing (Stage 3). Each of these three stages on their own are unavoidably limited; they are cumulative and, together with ROSE's (2012) method identified above, provided us with a rich and rigorous analysis. [32]

In stage one, the participant's perspective of their body-map is elicited to understand their intention(s). In the context of visual research, reflexive epistemologies "hold that the meaning of the images resides most significantly in the ways that participants interpret those images, rather than as some inherent property of the images themselves" (SPENCER, 2011, p.7). While the researcher brings particular expertise, including their ability to theorize and see patterns, they cannot be the first level of analysis. The researcher is best placed to provide overall analysis to the research which occurs in stage two and three (DREW & GUILLEMIN, 2010). [33]

Stage two of the analytic process includes researcher-focused reflections and development of themes based on what was said/unsaid and included/avoided on the body-maps. Through the processes of documenting, coding and categorizing a variety of data sources, patterns/themes emerge and can be interrogated. ROSE's (2012) approach, exemplified above and GRBICH's (2012) analytic questions also helped us reach more critical insights at this stage (see Table 5). While these approaches were not explicitly phenomenological, they were well suited to this study, and helped us adopt a lens to view the lived experiences in a deeper way.

|

Sample Critical Questions |

|

Where is the viewer's eye drawn to in the image and why? What relationships are established between the components of the image visually? What do the different components of an image signify? Is there more than one possible interpretation of the image? Are the relations between the components of this image unstable? What knowledges are being deployed What relationships exist between components of the image(s) How do such other signs impact on and affect the image? How does the image reflect or depart from dominant cultural values? |

Table 5: Sample of critical questions to ask during analysis (adapted from GRBICH, 2012, p. 202) [34]

During stage three, we explicitly focused on working with applied theoretical frameworks and conceptualizations to finalize a robust analytic explanation. Theory is present at each stage of the research but is prioritized here. Based on this analysis, we eventually came to a few key insights that formed the central themes of the study. Phenomenology, as a way of thinking about the world and lived experiences was prioritized at this stage. For us, and others (e.g., DOLEZAL, 2015), phenomenology at its most rudimentary, is about questioning, testing, and rethinking assumptions and the taken for granted about the life experiences under investigation. From there, new interpretations that better account for that experience can be understood. In this study we saw these women as expressing feminist awareness as a result of their mindfulness practice. They seemed to recognize the paradox between their lived experiences and what the social world allows many working mothers. Much like SARTRE's (1956 [1943]) contention that the other teaches me who I am, the women in this study were able to see the normative view of working mothers without necessarily adopting it. As one of the women, Loja, shared:

"So for me I had to really deconstruct what it really means to be a wife and mom, and the ideals that had shaped my life, and nuclear family. When I say family I don't mean a tribe in Africa, I mean our middle class, urban Caucasian family life. Which I didn't consciously want or create, despite thinking of myself as a very independent, spirited women. But ... It is what I co-created with society. You know, capitulated. Believing it was the goal. I spent years struggling with the white picket fence and ... now I see my nature, and have stopped resisting, mindfulness has helped me meditate into more of who I am! I am the mom that is sitting on the beach reading philosophy to preserve my sanity! If spending more time with your kids is what you want, then do it, but honestly you aren't doing yourself or anyone else any favors by pretending that is what you want." [35]

Rather than buy into the have-it-all-do-it-all discourse many women are told to assume (SOMERVILLE, 2005), the women in this study seemed to know that the road would be challenging, and compromises would need to be made. The women described unrealistic employment expectations such as long hours away from home that structurally limit how high many working mothers are actually able to climb within their work setting hierarchy. Importantly, they did not make concessions in an effort to appear normative. For example, Alicia chose to leave a well-paying leadership position seeing the demands were impossible to reconcile with her family demands. Joanne, Nina and Siobhan all opted for part-time work. [36]

The most overwhelming and repetitive theme was the notion of redefining the self in more feminine terms. As each woman became increasingly grounded in her experiences and who she is through mindfulness, she paradoxically became aware of the conventional and constructed nature of herself and her reality. From here—on, women were able to define their roles as worker/mother in more authentic terms. Living mindfully seemed to offer women a more nuanced understanding of how patriarchy impacted their lives. The following interview excerpt with Sally describing her 5-2 image exemplifies her ability to reframe and define motherhood on her own terms (Illustration 1). She says:

"The five and two are from the personality theory, enneagram's. I am a five personality type: Intellectual, analytical. Whereas a two is the stereotypically mother who is the do all, be all, helps everyone ... it's that perfect image of the mother. I am not the two, but if you invert the two you have a five. The two is my daycare provider ... she's my daughter's other mother in a lot of ways. So I can be the five, and that's the working part of me, but I embrace that mirror image in order to continue in my roles. The two of us have to come together. I fully embrace her ... I can't be my daughter's only mother. Here is this two-mother who my daughter spends her day with, who enables me to be the five that I am and not try to force myself into the two that society tells me often that I have to be or that I should be." [37]

Sally's ability to reframe motherhood is one of several instances the women shared about how mindfulness supported their awareness of how patriarchal ideas influence their lives. [38]

7. Body-Mapping's Contribution to Social Research

Body-mapping and phenomenology paired well together in this study, though pairing with other methodologies may be as useful. As one participant stated, body-mapping is not a cerebral exercise:

"None of it was planned—I much prefer to go with my intuition, otherwise I will overthink it and write 60 pages. So I just choose to see what came in the moment, so some of it is quite known [to me] and are images and symbols that have come to me repeatedly when I became a mother." [39]

This comment struck us as representative of the type of data a phenomenological study seeks to elicit: "... embodied and intersubjective relations [and] first person intuitive experiences of phenomena" (DOLEZAL, 2015, p.x). Thus far body-mapping has been primarily used as a method within participatory action research projects, and has also been explicated linked to phenomenological investigations (DE JAGER et al., 2016). Further research is needed to see how fruitfully body-mapping might pair with other methodologies such as narrative inquiry. [40]

While there are many contributions body-mapping might make to qualitative research, we highlight two of the more important ways this method supported this study: First, what struck us about this method was the richness of the discussion and how quickly the women would access sensitive and powerful topics. Second, compared to qualitative interviews we have conducted in other projects, this method seemed to incite greater socio-political commentary. We discuss each of these in turn. [41]

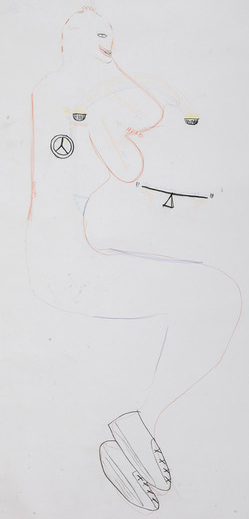

While the profile of visual methodologies has climbed since PROSSER (2005b) first articulated the challenges visual researchers face, the field is still in its infancy and confidence in the ability of visual images to provide important social findings are at times tenuous. When we initially started this project we were hopeful the visual data could stand alone, imagining the images would tell a tale without the need for additional interpretation through words. However, we found that it was only with words that we were able to fully understand what the women's experiences were like. The richness of this understanding however struck us as more powerful than words alone may have afforded. The blue eyes drawn by one of the participants illustrates our point (see Illustration 2). One of the steps in the body-mapping sessions was for the women to make a self-portrait. This particular participant used blue crayon to color her eyes. Initially, we assumed she was simply coloring in her natural eye color for her self-portrait; however, when looking at her closer her eyes were not actually blue. When we explored this with her in the interview there was a much richer understanding to be had. She shared that her eyes become blue-like when she cries and feels things deeply. She shared that mindfulness helps her feel all of her emotions without turning away from any of them. This experience highlights why MAIR and KIERANS (2007) argue that the text or verbal commentary, and not the drawings, should be the researcher's primary analytical focus (Stage 2 described above).

Illustration 2: Rich data imagery1) [42]

While this example demonstrates an important analytic insight, it also highlights the power of visual methodologies. Without the drawing we are not confident we would have come to the same discussion. It was such an important discussion that it prompted us to start to notice if this was common to other mothers who practice mindfulness. An overarching theme eventually emerged about mothers turning to the difficult emotions and painful parts of life; our discussion about the blue eyes was fundamental to its development. [43]

Body map storytelling is a data generating research method used to tell a story that can visually reflect social, political and economic processes (GASTALDO et al., 2012). Further, individuals' embodied experiences and meanings attributed to these processes, and how they shape participants lives become clearer (ibid.). The broader aims of this included attention to how women negotiate social-political influences as working mothers, and what role, if any, mindfulness plays:

"At first glance, contemplative mindfulness and critical inquiry seem at opposite poles of a reflective spectrum, yet Eastern and Western philosophers have described a dual dimension to reflective thought that incorporates both. Contemplative practices, such as mindfulness meditation, open a broad perspective on a problem and lead to clarity of intent that may be clouded by incessant probing" (WEBSTER-WRIGHT, 2013, p.557). [44]

The original Buddha, Siddhartha Gautama, may be seen as a man in critical relationship with his culture (COHEN, 2010). COHEN critiqued many of the assumptions held within the Indian caste system, questioning why social position was considered an inherited birthright. Despite these historical moorings, mindfulness is commonly situated, understood, and researched as an individual practice, rather than as a way of engaging in social critique (ibid.). Entering this study, we believed that mindfulness may be both an individual practice (e.g., a way to cope with everyday challenges), and one that can bring about social change (e.g., questioning social ideals constructed through institutions such as patriarchy, class or race). [45]

Given these critical underpinnings, we were concerned the participants would offer politically correct, sanitized or overly conscious drawings, particularly given motherhood is steeped in normative ideals. However, the depictions the women created seemed to authentically critique their social world. GANESH (2007) highlights that visual data is particularly suited to challenge power relations and social structures, and to envision a more hopeful future. There were few depictions of how happy mindfulness made them, or how ideal their families were. Body mapping does seem to be particularly well—suited for critical and political insights. The white picket fence prison and collective focus discussed above (Table 4, Figures 5 and 6) were one of many images that challenged dominant cultural narratives about motherhood and how patriarchal ideals shape this experience. [46]

This idea is supported by other researchers. MacGREGOR (2009) suggests, "... the exercise [of body mapping] will empower participants through the acquisition of knowledge and personal insight" (p.89). Likewise, in a recent systematic review of body mapping DE JAGER et al. (2016) notes the method has political roots with many projects including varying degrees of a social justice agenda. MacGREGOR (2009) shows that political messages permeated all the body-maps in her study with women living with HIV and AIDS. Additionally, SWEET and ESCALANTE (2015) found the women in their study used their body-maps to critique how unsafe neighborhoods can be for women and offered different possibilities to make safety a priority. [47]

8. Limitations and Quality Assessment

Body-mapping is not without its limitations. Some participants had more barren maps, which posed an analytical challenge. Perhaps this demonstrated a lack of interest on the participant's behalf, a lack of experience engaging with their thoughts aesthetically, or lack of confidence. With little imagery to work with it can be difficulty to reach more latent meanings or critical insights. Though BOYDELL et al. (2012) caution researchers from judging what counts as good representation of experiences. Notably, in our study the women who completed their maps in groups seemed less concerned about their artistic abilities, perhaps from the collegial conversational nature of the group. Women most comfortable with aesthetic mediums may have also chosen the group format. Alternatively, relatively barren maps may be important venues to better understand the phenomena under investigation. This is where the interviews were, with some participants, useful to fully understand the experiences depicted. Though for one participant in particular her map was relatively barren and the interview had correspondingly fewer critical insights. [48]

The use of images can be foreign for participants, who may already be intimidated by the idea of research. At times we found the participants wanted hints as to what to draw. One of the steps asked the participants to draw a symbol that represented their power point, or where they draw upon for strength. The dialogue below with two different participants about the same step exemplifies:

Participant: "Can you give me some hints?"

Researcher: "It could be a symbol, a word, a phrase, a number, a letter ..."

Participant: "hmmmm ... ok I am going to do a word" [49]

Another participant asked:

Participant: "So where do I draw it?"

Researcher: "Really anywhere."

Participant: "ok, I'm still not sure ... ummm"

Researcher: [after a long pause] "So, if it feels cerebral then you could place it on your head. If it feels bodily then maybe on your body." [50]

While this step was a challenge for some of the women, for others it was an opportunity to draw very powerful imagery. Rather than a flaw in the step or question, perhaps people who do not commonly engage with aesthetic mediums need additional support in body mapping research. At times we worried that our directions were too leading and wondered if seeing a sample body map may help participants appreciate the intent of the research. Ultimately we decided against this believing the ways people chose to visual depict their lives is incredibly diverse, and patience and time to deeply consider questions are essential. [51]

The imagery the women provided made analysis and meaning making a richer and more authentic process. However, we are conscious that body map storytelling requires additional time from participants, and participants must be given the opportunity to weigh the pros and cons of this time commitment. For us, the time was well spent and the women seemed to enjoy the process. This may not always be the case in other projects. Many of the women commented on how much they enjoyed and benefited from the process, so this alone bolsters us to consider using the method again as shared by one of the participants:

"You know that felt really good. You can go through your days and not notice what is helping you and why. This makes sense to me and it re-affirms that I need to keep doing what I need to keep doing and to prioritize ‘me time', which can feel expendable, and it shouldn't be!" [52]

We began this article by describing body mapping, and how we designed our study using body map storytelling to understand how mindfulness contributes to the health and well-being of working mothers who practice mindfulness. When we initially designed the project, we found few examples describing the process of designing and executing such a project. The passage below highlights both the fun and overwhelming nature of this method for researchers and participants new to the method:

Participant 1: It was hard to stay away from words!

Participant 2: I want to hear what yours is all about.

Participant 1: No I want to hear what yours is all about!

Participant 2: (laughing) It expresses all sorts stuff. I don't know where to start! [53]

In light of this experience, we aimed to offer both practical and ethical considerations other researchers may find useful when designing their own research project using body mapping. Throughout this article we have shared lessons learned and found the method a particularly fruitful paring with both the topic (mindfulness) and the methodology (phenomenology), though additional research is needed to understand how body mapping gets employed with other methodologies. To conclude, we highlight some key considerations discussed in the article: 1. the structure of session, 2. participant concerns, and 3. socio-political critique. [54]

First, we learned it is important to offer participants the choice whether to participate in a focus group or sole-participant session. As a participant in this dissertation study shared,

"And I thought about doing it as a group—oh it would be fun and be social and then I thought about doing the actual exercise. It would change my answers. I would be too easily influenced [pause] ... This is a more accurate representation of me, and it would be different with others in the room, and not in a positive way." [55]

When we did meet with women in a group format, the sessions were very social and supportive. Because the sessions were relatively long (2-4 hours each), we supplied some nourishment, and this seemed to help build a supportive atmosphere for the group-setting participants. This may be even more important for participants who have to travel distances to attend body mapping sessions. Further some participants wanted to complete all aspects of the research in one full day, whereas others wanted time in between body map construction and interview. These decisions all came from the participants and did not impact the analysis process or quality of the data from our perspective. [56]

Second, many participants expressed trepidation about the idea of visually representing their experiences. Most research participants volunteer to engage in research because they believe they can valuably contribute (COX & McDONALD, 2013), so to initially feel unprepared can be disconcerting. As we reflect back on the study, and knowing the positive note all the sessions ended on, we would worry less about participant hesitation and rather offer participant's patience, reassurance and time to warm to the idea of drawing as research (DOODY & NOONAN, 2013). [57]

Last, we had explicit interest in understanding how mindfulness helped working mother's critique problematic social constructions of motherhood. It is important for working women to share these narratives rather than perpetuate the belief that career and family is simply a matter of good balancing and time management. Living mindfully seemed to offer women a more nuanced understanding of how patriarchy impacted their lives. Body mapping was an invaluable way for the women to share these experiences, and we left the project firm in the belief that the method enabled us to understand the subject in a deeper way than interviews alone would have afforded us. [58]

While body mapping is certainly not the only method to support egalitarian research practices or incite political thinking, and does come with potentially serious ethical challenges, it is worthy of consideration for social and health research. Body mapping privileges the body in research in ways that we argue are simultaneously fun, accessible and meaningful for both participants and researchers. This article was written with the intent of encouraging other qualitative researchers to consider body mapping, seek appropriate training on the method, and also offer useful insights about project design and execution. [59]

1) The entire map was centered around the participant's heart suggesting mindfulness was very central to her emotions and life. <back>

Asher, Rebecca (2012). Shattered: Modern motherhood and the illusion of equality. London: Vintage Books.

Banks, Marcus (2007). Using visual data in qualitative research. Los Angeles, CA: Sage.

Boydell, Katherine M.; Volpe, Tiziana; Cox, Susan; Katz, Arlene; Dow, Reilly; Brunger, Fern; Parsons, Janet; Belliveau, George; Gladstone, Brenda M.; Zlotnik-Shaul, Randi; Cook, Sheila; Kamensek, Otto; Lafreneière, Darquise & Wong, Lisa (2012). Ethical challenges in arts-based health research. The International Journal of the Creative Arts in Interdisciplinary Practice, 11, http://www.ijcaip.com/archives/IJCAIP-11-paper1.pdf [Accessed: January 10, 2020].

Buchanan, Lindal (2013). Rhetorics of motherhood. Chicago, IL: Southern Illinois University Press.

Centre for Social Science Research (2004). Mapping workshop manual: Finding your way through life, society and HIV. Cape Town: Centre for Social Science Research, University of Cape Town, https://www.aidsfocus.ch/en/topics-and-resources/prevention-treatment-and-care/memory-work/mapping-workshop-manual-finding-your-way-through-life-society-and-hiv [Accessed: June 7, 2015].

Cohen, Elliot (2010). From the bodhi tree, to the analyst's couch, then into the MRI scanner: The psychologisation of buddhism. Annual Review of Critical Psychology, 8, 97-119.

Cohen, Marlene; Kahn, David & Steeves, Richard (2000). Hermeneutic phenomenological research: A practical guide for nurse researchers. London: Sage.

Cornwall, Andrea (1992). Body mapping in health RRA/PRA. RRA Notes, 16, 69-76, https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/c43d/29afeebd793b89615e2495bcea20453a520c.pdf [Accessed: May 22, 2015].

Cox, Susan & McDonald, Michael (2013). Ethics is for human subjects too: Participant perspectives on responsibility in health research. Social Science and Medicine, 98, 224-231.

Crawford, Allison (2010). If "the body keeps score": Mapping the dissociated body in trauma narrative, intervention, and theory. University of Toronto Quarterly, 79, 702-719, https://doi.org/10.3138/utq.79.2.702 [Accessed: October 15, 2019].

de Jager, Adele; Tewson, Anna; Ludlow, Bryn, & Boydell, Katherine (2016). Embodied ways of storying the self: A systematic review of body-mapping. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung / Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 17(2), Art. 22, http://dx.doi.org/10.17169/fqs-17.2.2526 [Accessed: January 19, 2020].

Dew, Angela; Smith, Louisa; Collings, Susan & Dillon Savage, Isabella (2018). Complexity embodied: Using body mapping to understand complex support needs. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung / Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 19(2), Art. 4, http://dx.doi.org/10.17169/fqs-19.2.2929 [Accessed: June 7, 2019].

Dolezal, Luna (2015). The body and shame: Phenomenology, feminism, and the socially shaped body. New York, NY: Lexington Books.

Doody, Owen & Noonan, Maria (2013). Preparing and conducting interviews to collect data. Nurse Researcher, 20(5), 28-32.

Drew, Sarah & Guillemin, Marilys (2010). From photographs to findings: Visual meaning-making and interpretive engagement in the analysis of participant-generated images. Visual Studies, 29(1), 54-67.

Ganesh, Tirupalavanam (2007). Commentary through visual data: A critique of the United States school accountability movement. Visual Studies, 22(1), 42-47.

Gastaldo, Denise; Magalhaes, Lilian; Carrasco, Christine & Davy, Charity (2012). Body-map storytelling as research: Methodological considerations for telling the stories of undocumented workers through body mapping. http://www/migrationhealth/ca/undocumented-workers-ontario/body-mapping [Accessed: October 10, 2014].

Gillis, Stacy; Howie, Gillian & Munford, Rebecca (2007). Introduction. In Stacy Gillis, Gillian Howie & Rebecca Munford (Eds.), Third wave feminism: A critical exploration (exp. 2nd ed., pp.xxi-xxxiv). Basingstoke: Palgrave.

Grbich, Carol (2012). Qualitative data analysis: An introduction. Los Angeles, CA: Sage.

Gubrium, Aline (2013). Participatory visual and digital methods. Walnut Creek, CA: Left Coast Press.

Guillemin, Marilys & Drew, Sarah (2010). Questions of process in participant-generated visual methodologies. Visual Studies, 25(2), 175-188.

Guillemin, Marilys & Westall, Carolyn (2008). Gaining insight into women's knowing of postnatal depression using drawings. In Pranee Liamputtong & Jean Rumbold (Eds.), Knowing differently: An introduction to experiential and arts-based research methods (p.121-140). New York, NY: Nova Science.

Hartman, Laura; Mandich, Angela; Magalhaes, Lilian & Orchard, Trina (2011). How do we "see" occupations? An examination of visual research methodologies in the study of human occupation. Journal of Occupational Science, 18(4), 292-305.

Hayes-Conroy, Jessia & Hayes-Conroy, Allison (2010). Visceral geographies. Geography Compass, 4(9), 1273-1283.

Heywood, Leslie (2005). Introduction: A fifteen-year history of third-wave feminism. In Leslie Heywood (Ed.), The women's movement today: An encyclopedia of third-wave feminism (Vol. 1, pp.xv-xxii). Westport: Greenwood.

Kabat-Zinn, Jon (2005). Full catastrophe living: Using the wisdom of your body and mind to face stress, pain, and illness. New York, NY: Random House.

Kabat-Zinn, Jon (2013). Some reflections on the origins of MBSR, skillful means, and the trouble with maps. In Mark Williams & Jon Kabat-Zinn (Eds.), Mindfulness: Diverse perspectives on its meanings, origins and applications (pp.281-306). New York, NY: Routledge.

Kristeva, Julia (1980). Desire in language: A semiotic approach to literature and art. New York, NY: Columbia University Press.

Laws, Sophia & Mann, Gillian (2004). So you want to involve children in research?: A toolkit supporting children's meaningful and ethical participation in research relating to violence against children, https://resourcecentre.savethechildren.net/library/so-you-want-involve-children-research-toolkit-supporting-childrens-meaningful-and-ethical [Accessed: October 10, 2014].

Luttrell, Wendy (2010). "A camera is a big responsibility": A lens for analysing children's visual voices. Visual Studies, 25(3), 224-237.

MacCormack, Carol (1985). Lay perceptions affecting utilization of family planning services in Jamaica. Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene, 88, 281-285.

MacGregor, Hayley (2009). Mapping the body: Tracing the personal and the political dimensions of HIV/AIDS in Khayelitsha, South Africa. Anthropology & Medicine, 16(1), 85-95.

Mair, Michael, & Kierans, Ciara (2007). Descriptions as data: Developing techniques to elicit descriptive materials in social research. Visual Studies, 22(2), 120-136.

Meyburgh, Tanja (2006). The body remembers: Body mapping and narratives of physical trauma. Counselling psychology. Dissertation, councelling psychology, University of Pretoria, South Africa, https://repository.up.ac.za/handle/2263/29236. [Accessed: May 22, 2019].

Moran, Dermot (2018). What is the phenomenological approach? Revisiting intentional explication. Phenomenology & Mind, 15, 72-90.

Morgan, Jonathan (2004). Long life: Positive HIV stories. Cape Town: Double Story Books.

Munhall, Patricia (2012). A phenomenological method. In Patricia Munhall (Ed.), Nursing research: A qualitative perspective (5th ed., pp.113-175). Mississauga: Jones and Bartlett Learning.

Oliffe, John; Bottorff, Joan; Kelly, Mary & Halpin, Micheal (2008). Analyzing participant produced photographs from an ethnographic study of fatherhood and smoking. Research in Nursing and Health, 31, 529-539.

Oliffe, John; Bottorff, Joan; Johnson, Joy; Kelly, Mary & LeBeau, Karen (2010). Fathers: Locating smoking and masculinity in the postpartum. Qualitative Health Research, 20(3), 330-339.

Orchard, Trina (2017). Remembering the body: Ethical issues in body mapping research. Cham: Springer.

Papademas, Diana (2009). IVSA code of research ethics and guidelines. Visual Studies, 24(3), 250-257.

Park Lala, Anna & Kinsella, Elizabeth Anne (2011). Phenomenology and the study of human occupation. Journal of Occupational Science, 18(3), 195-209.

Prosser, Jon (2005a). Introduction. In Jon Prosser (Ed.), Image-based research: A sourcebook for qualitative researchers (pp.1-5). Philadelphia, PA: Taylor and Francis Group.

Prosser, Jon (2005b). The status of image-based research. In Jon Prosser (Ed.), Image-based research: A sourcebook for qualitative researchers (pp.86-99). London: Taylor and Francis e-library.

Prosser, Jon (2011). Visual methodology: Towards a more seeing research. In Norman K. Denzin & Yvonna S. Lincoln (Eds.), The Sage handbook of qualitative research (pp.479-496). Los Angeles, CA: Sage.

Rose, Gillian (2012). Visual methodologies: An introduction to researching with visual materials. London: Sage.

Sartre, Jean Paul (1956 [1943]). Being and nothingness: An essay on phenomenological ontology. New York: Philosophical Library.

Shapiro, Shauna & Carlson, Linda (2009). The art and science of mindfulness. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

Solomon, Jane (2002). Living with X: A body mapping journey in the time of HIV and AIDS: Facilitator's guide. South Africa: REPSSI.

Somerville, Margaret (2005). "Working" culture: Exploring notions of workplace culture and learning at work. Pedagogy, Culture and Society, 13(1), 5-25.

Spencer, Stephen (2011). Visual research methods in the social sciences: Awakening visions. New York, NY: Routledge.

Suresh, David (2016). Howling at the moon. London: Platypus Press.

Sweet, Elizabeth & Escalante, Sara (2015). Bringing bodies into planning: Visceral methods, fear and gender violence. Urban Studies, 52(10), 1826-1845.

Walker, Rebecca (1995). Introduction: Becoming the third wave. In Rebecca Walker (Ed), To be real: Telling the truth and changing the face of feminism (pp.39-41). New York, NY: Anchor.

Webster-Wright, Ann (2013). The eye of the storm: A mindful inquiry into reflective practices in higher education. Reflective Practice, 14(4), 556-567.

Wise, Erica & Hersh, Matthew (2012). Ethics, self-care and well-being for psychologists: Reenvisioning the stress-distress continuum. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice, 43(5), 487-494.

Lisa McCORQUODALE, PhD is a professor in the School of Community Studies at Fanshawe College. Lisa has worked for 20 year as an occupational therapist and is a faculty member in the Honours Bachelor of Early Childhood Leadership Degree Program at Fanshawe College. She is also an adjunct professor at Western University. Her research focuses on how spirituality, including mindfulness and other reflective practices, might support the personal and professional lives of health and social care professionals, as well as young children and their families.

Contact:

Dr. Lisa McCorquodale

School of Community Studies

Fanshawe College

1001 Fanshawe College Blvd. N5Y 5R6

London, Ontario, Canada

Tel.: 519-452-4430, 4103

E-mail: lmccorquodale@fanshawec.ca

Sandra DeLUCA, PhD holds joint appointments at Fanshawe College and Western University. She is associate dean of the School of Nursing at Fanshawe College and an adjunct associate professor in the Arthur Labatt Family School of Nursing and Faculties of Education and Health Sciences at Western University. She is a researcher at the Centre for Education, Research & Innovation at the Schulich School of Medicine & Dentistry. Sandra has over 40 years of teaching experience in undergraduate programs in nursing education in college and university programs. For the past 15 years, she has taught graduate courses in health & rehabilitation sciences.

Contact:

Dr. Sandra DeLuca

Associate Dean, School of Nursing

Fanshawe College

1001 Fanshawe College Blvd. N5Y 5R6

London, Ontario, Canada

Tel.: 519-452-4430, 4645

E-mail: sdeluca@fanshawec.ca

McCorquodale, Lisa & DeLuca, Sandra (2020). You Want Me to Draw What? Body Mapping in Qualitative Research as Canadian Socio-Political Commentary [59 paragraphs]. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung / Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 21(2), Art. 6, http://dx.doi.org/10.17169/fqs-21.2.3242.