Volume 9, No. 1, Art. 21 – January 2008

Power, Conflict, and Spirituality: A Qualitative Study of Faith-Based Community Organizing

Brian Christens, Diana L. Jones & Paul W. Speer

Abstract: Community organizing is a process of garnering power and taking collective action which is often initiated by groups with little individual economic or social power. Through collective action, organizing groups are able to exert influence in societal systems, many times outside or against the direction of existing power structures. As such, conflict is inherent in the community organizing process. The analyses in this article are based on a series of in-depth interviews conducted with highly active members of community organizing that is operated through faith-based institutions. Analyses reveal multiple connections between dimensions of power, conflict, and spirituality. The paper presents these connections and moves toward emergent hypotheses about the functioning of power and conflict in faith-based community organizing.

Key words: organizing, power, conflict, empowerment, community, spirituality, civic engagement

Table of Contents

1. Introduction

2. Case Study Background

3. Methodology

4. Themes

4.1 Power

4.2 Power and spirituality

4.3 Power and conflict

4.4 Conflict and spirituality

5. Discussion: Power, Conflict, and Spirituality

Appendix 1: Interview Schedule

Community organizing in the United States is exercised in a variety of ways. Typologies outlining the array of organizing strategies have been offered by many, including FISHER (1994), STALL and STOECKER (1998), ROTHMAN (1996), DELGADO (1994), and SMOCK (2004). Some categorizations are based on ideology (FISHER, 1994) others on practice (ROTHMAN, 1996; STALL & STOECKER, 1998) and others are a blending of both (SMOCK, 2004). The most common typological distinction is ROTHMAN's (1996; see also ROTHMAN, ERLICH & TROPMAN, 1968) division of community organizing by practice. He identifies social planning, community development and social action as the three major practice approaches in the field. Social planning is often associated with rational and professional community work. Often these approaches engage professionals on behalf of community and implicit in their work is that resources are available, just inefficiently managed. Community development approaches instead are often associated with self-help and are deeply anchored in a place-based focus. Community development approaches are often characterized as delivering goods and services to residents of target neighborhoods—often with an implicit assumption that residents affected by problems are, in some way, deficient and in need. Social action is contrasted with these two approaches by an emphasis on direct participation of residents and an explicit interest in developing power that can influence the flow of external resources into the target area. The assumption in social action efforts is not that target communities are deficient, but that they lack social power. [1]

This study is focused on a type of community organization that most closely resembles a social action approach. This approach is strongly associated with Saul ALINSKY (1971) who provided a basic model for community organizing that was popularized in cities across the United States throughout the late 1960s and 1970s. Although many community groups exercise collective power in a democratic context, the ALINSKY model stood out for its radical approach to power and conflict, which stressed decisive action to build power within organizations working for change. For ALINSKY, organizing entailed diverse groups within specific neighborhoods banding together to pressure for change. His methods stemmed from union organizing of the early 20th Century and he felt that by combining locally based schools, churches, associations and the like to work for their common self-interest, power could be held by local organizations which were controlled by local residents and not just institutions and corporations within the broader community. Although ALINSKY'S successes were mixed, his influence remains. Nevertheless, with economic restructuring and globalization, the power of traditional, or ALINSKY-style, organizing has waned as this tactical approach became less effective. In particular, the scale at which decision-making operates in advanced capitalist economies is much greater than what a locality-based approach can address (FISHER & SHRAGGE, 2007; ORR, 2007). [2]

In more recent years, several ALINSKY-styled networks of community organizing have turned to religious congregations, which tend to be relatively stable, as a base for community organizing in a post-industrial economy. Religious groups have played a particularly central role in American public life for centuries (TOCQUEVILLE, 2001) and continue to play multiple prominent roles. Estimates are that between 10 and 15 percent of private employment in the United States is affiliated with religious groups (QUEEN, 2002). This applicability of community organizing is not limited to the United States—applications and impacts have been documented throughout the world, including Germany (SZYNKA, 2002). [3]

The transition from an ALINSKY-styled approach to one that is anchored in religious congregations (of multiple denominations and faiths) elevates certain tensions and contradictions between ALINSKY'S boisterous style and the somewhat pious style associated with religion. ALINSKY quoted the Christian Bible to support the conflictual element of his style of community organizing; "The classic statement on polarization comes from Christ: 'he that is not with me is against me' (Luke 11:23)" (ALINSKY, 1971, p.134). How might we understand the blending of this embrace of conflict with religious congregations? [4]

Importantly, there has been an evolution in the social action approach to organizing since ALINSKY. There remain some community organizations that adhere strongly to the ALINSKY model, yet other social action approaches have changed substantially. Generally, across most social action approaches that have evolved from ALINSKY, there remain several common features. The building block of this organizing style is the one-on-one relationship, a process through which listening, sharing and common values of everyday citizens can emerge. As issues emerge that are affecting the community, the members research that issue to understand the magnitude of the problem, the causes of the problem and potential solutions. Next, action steps are taken to address the causes of the problem. Action steps may take the form of collaboration with other organizations. And, these actions often have a target: an individual or group that is pressured. As with ALINSKY, the intended result is sometimes polarization and a fight. [5]

Faith-based community organizing (FBCO) has been discussed as a valuable route to individual and collective power and empowerment (SPEER, HUGHEY, GENSHEIMER & ADAMS-LEAVITT, 1995; BOYTE, 1989; WOOD, 2002; ROBINSON & HANNA, 1994; WARREN, 2001). It is also more generally recognized for its relationship to community development and community building (RUBIN & RUBIN, 2000; McNEELY, 1999). There is a tendency among social scientists to focus more on social movements than on local community organizing (STALL & STOECKER, 1998). And, among studies of faith-based community organizing, there is a tendency to treat faith and spirituality as incidental to organizing (SLESSAREV-JAMIR, 2004). While we identify this form of community organizing as "faith-based," it might also be called "institution based," "values-based," or "congregation-based" depending on the rubric that is used. [6]

The analyses in this article are based on interviews attained through action research collaborations with a community organization affiliated with PICO1), a national network of faith-based community organizing groups, with over 50 projects in the United States. "Since 1972 PICO has successfully worked to increase access to health care, improve public schools, make neighborhoods safer, build affordable housing, redevelop communities and revitalize democracy" (PICO, 2004). PICO claims no connection to ALINSKY, although their social action approach clearly has had some influence from the ALINSKY style. Nevertheless, while their approach has evolved dramatically so that there is little outward ALINSKY influence remaining in this network, conflict is still a phenomenon that is present at times within PICO organizing. Although religious groups have played a strong, and perhaps increasing, role in the shaping of public policy at various levels of government (PESHKIN, 1986), faith-based community organizing is not directly associated with the religious groups themselves. Rather, it is an approach that networks members associated with a congregation, parish, mosque, synagogue, or other faith-based group. This strategy has been adopted due to the social capital that religious groups often foster within their networks (SCHNEIDER, 1999). In addition, situating power-based community organizing within the context of religious institutions potentially bolsters the legitimacy of the work and deepens the cultural resources available to those involved (WOOD, 2002). How the use of intentional conflict strategies and alteration of power relationships operate within this faith-based framework, however, is not fully understood. [7]

The PICO model builds community organizations by working with religious congregations of all faiths. The relationship with each congregation is developed independently, and local organizing work continues at this congregation level and occasionally on issues that cut across the community. PICO professional organizers do not necessarily belong to any faith. The network's website states that, "PICO believes that religion brings us together rather than divides America; that our varied faith traditions call on us to act to make our communities and our nation better places to live" (PICO, 2004, n.p.). Despite this inclusive and tolerant view of religion and its role in the public arena, the organizing model that PICO uses at times encourages conflict and even radicalism in the pursuit of justice. Conflict-based strategies, such as are often employed by PICO, have generally been in decline in the U.S. (FISHER & SHRAGGE, 2000), as well as within the PICO network. Partnerships, collaborations, and other forms of community development (RUBIN & RUBIN, 2000) have become more common, while attempts to achieve radical change at the grassroots level have been less frequent. Conflicts engaged by PICO are not based on religious issues, but on issues of quality of life and social justice. Due to the faith-based setting of the organizations, however, these issues are often suffused by religious belief. [8]

This analyses presented in this study utilize methodologies associated with the naturalistic paradigm (ERLANDSON, HARRIS, SKIPPER, & ALLEN, 1993), and did not begin with a specific theoretical question and proceed to empirical testing. Observations and interviews provided data that were then coded according to themes. Relationships between categories in the analyses emerged during this process. Linkages to theory arose subsequently and are part of the discussion of the data and the analyses. [9]

The interviews with the members of a faith-based community organizing network were conducted with an eye toward understanding the interplay between the organizing process and individual perceptions of that process, including the way that experience is framed in terms of spirituality, and the way that spirituality influences action (see Appendix 1). The interviews lasted between 30 and 90 minutes, were tape-recorded, then transcribed and entered into a coded database. Categories of spirituality, power and conflict were established through an initial open re-reading of the interviews. Parent categories (Organizing, Personal Experiences, Issues, Local Context, and Results) were established to contain sub-categories. A subsequent process of selective coding took place. Categories were analyzed independently and for relationships to each other. During the analyses, the associations between the exercise of power and the dynamics associated with conflict emerged, as well as associations between both of these variables and spirituality. [10]

The data for this study were gathered as a part of the Skipper Initiative, which was developed to explore how the quality of life for children and families could be improved through community organizing. Through a five-year study, qualitative depth interviews with leaders and members of five cities and five PICO organizing sites throughout the United States were conducted. Although the overall research project is quasi-experimental and involves quantitative data analysis, the current study focuses on data gathered from ten depth interviews conducted with individuals over two visits to one of the five organizations. The participants were identified and recruited for participation in the study by the leaders of the local organization. The criteria for selection included length of time involved with the organization, depth of involvement, and perceived level of knowledge of the organizing process and the local context. A sample including individuals with varied roles and perspectives was requested. While roles differed, the respondents were all stable members or leaders of the organizing group, with a history of involvement in the community and this organization. [11]

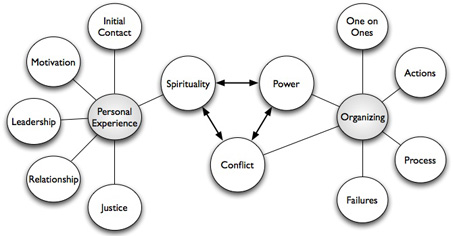

During initial analysis of the qualitative data the overlapping of the themes of power, conflict and spirituality were evident. While it is not demonstrable that there is causation or coherent correlation between these variables, it is the case that they are often associated in the subjective accounts of the study participants. Figure 1 illustrates the hierarchy of the coded categories and the relationships between the categories of power, conflict, and spirituality. This paper discusses data from these three themes alongside relevant previous research, and then discusses relationships between the three themes in a theoretical context.

Figure 1: Coded categories [12]

Within the process of community organizing, power is a central theme (ROBINSON & HANNA, 1994; WARREN, 2001; WOOD, 2002). Many parts of community organizing processes are designed to build power for purposes including the mobilization of members, the attainment of influence, the ability to speak and be heard, the reinterpretation of existing information, and the enforcement of decisions and concessions (SPEER et al., 2003). Social power in community organizing operates at multiple levels in a fluid way. It is fluid because it cannot exist except in relationship between groups of people or individuals (FOUCAULT, 1980). And, it is built or diminished both by the interactions of the members of the organizing group, and by the group's interactions with outside entities. [13]

Organizers and leaders within the organization seek to simultaneously build power and empower those with whom they are working. They also seek to understand the power relationships within the realms in which they hope to achieve change. The analyses of power within the community at large help them to know where to apply pressure for leverage within systems.

"I also think we hadn't done a really, really good job at what we call power analysis, which is to really understand what are the workings of the government in the city, who you need to be talking to. We probably weren't talking to the right people at our public meeting, or at least not all of them."2) [14]

The desire to understand the workings of power outside the organization is associated with the central goals of the organization. The exercise of power within this framework becomes much more effective when pressure is applied with an understanding of these power dynamics. The organization simultaneously tries to build its own power. Within the organization, there is a sense that the power-building process is moving forward, "I mean, you know, nothing's going to change overnight—or even in my lifetime—but you can make progress. And if you look at some of the things that have happened in individual cities, individual communities, it's pretty amazing." [15]

Spirituality is defined according to DOKECKI, NEWBROUGH and O'GORMAN (2001) as including the psychological sense and/or experience of being a part of or connected to a realm of existence beyond one's immediate self or situation. Contained within such a definition is a sense of relationality, or unity with others and with the natural environment. As a component of the spirituality of the participants in this study, there is a faith in the existence of a religious or supernatural realm that cannot be seen. CHAPMAN writes, "spiritual in its origin, faith demands expression and embodiment in every aspect of personal and social existence. Faith exists not in the abstract, but in relating and living in the concrete realities of specific situations" (1991, p.31). The interviewees are participants in an organization that uses faith- based institutions as its basic organizing units. Speaking of the unity within her faith-based institution, one participant asked rhetorically, "Well, what else unites people in this country?" The association between power and spirituality is strong. Interviewees made frequent reference to their spiritual lives when talking about power and organizing. For example, according to one interviewee, "[power-based organizing has] really helped me to think about, you know, those aspects of my faith and to say, 'yeah, this is really what it's about'." Additionally, the power of the organization and its successes are sometimes credited to spiritual entities.

"And we would talk about it as a board and feel, 'I don't know what's going to happen, I don't know how we're going to deal with this'. And within a month or two something would fall in our lap that would take care of it. And over and over again we have said, 'wow you can't help but feel that the hand of God was right there with you making sure that this need was met in some way.'" [16]

Not every interviewee is as adamant about the intersection of spirituality and organizing work as the PICO leader above. For example, another interviewee stated, "I really don't think there was so much of a Christian direction as it [the organization] was just some structure of getting people involved and looking together, keeping them working together." This particular organization has worked not just with congregations; they have also worked closely with a group that is more akin to a homeowner's association, potentially blurring the lines between faith-based and neighborhood organizing. Although the idea of community organizing as a religious ministry was advanced by some of the interviewees, they were often quick to point out that they do not view organizing as charity work. According to some, though, the exercise of power through organizing can be the action component of a spiritual "calling." [17]

One participant stated, "so it's … I think 'calling' is correct, that is a correct term and there is a definite religious basis to it on my part. So there you are." This idea of community organizing as central to one's spiritual calling or ministry is used to explain the continued participation in the organizing process, or the discontinuation in participation in some cases.

"We have some people that just come in for the issue, and then they drop out. And then we have some people who really understand what community organizing is about, and those people kind of stick with it. You know, they see that it's not just an issue thing, [but] that this is a ministry of the church and they continue in it. But those are far and few." [18]

The existing relationships and a sense of spiritual calling function in ways that sustain participation in organizing. In the words of one participant, "Well, I don't think you can separate organizing from ministry because that's what it is; we're here to do justice as far as ministry is concerned. And community organizing is one of those ways to do justice. It's not a charity thing; it's justice." Thus, the exercise of power through organizing and the values or responsibilities that come from spirituality or spiritual teaching are viewed as inextricable by at least some portion of those involved with faith-based community organizing. [19]

Racial/ethnic, professional, family, and community identities also enter into interviewees' descriptions of the power of organizing. A spiritual/religious identity is sometimes mentioned in conjunction with these identities, making the segregation of a distinct "spiritual/religious identity" questionable.

"Because of my involvement in church and seeing all the needs that people have, I become more involved. And I guess as a social worker, that's what I am. We find a lot, that's what my father was, too, so I come from a family of real Latino spirit. It's the spirit of 'we work together and we stay together'. And we can accomplish things that way as a group, as a community, but on your own you can't do anything." [20]

From the descriptions in the overlap between these two strands of data (power and spirituality), it is apparent that spirituality sometimes plays a role in organizational decision-making. Other times, it is simply a shared background, or how and/or why people become "more involved." The frequent associations with faith and spirituality pervade descriptions of the organizing process. Certain traditions of faith-based institutions are adapted to the organizing process in creative ways, as can be seen in the following description of collective action.

"Well, um, a lot of people do charity stuff, you know. They think that's a great thing, they're doing great work. But my goal here is to educate people, to form people, to have an experience—sort of a conversion—where they find out that community organizing is what's really needed to change the system." [21]

Collective action takes on the role of a cultural value. A leader, in this case, compares the move toward collective action to "a conversion." The faith-base of the organization, then, provides more than ready-made social capital for the organizing process. It is central to the identity, motivations, and understandings of the people involved in the process. Elements of spiritual experience or religious tradition can also serve as powerful metaphors for elements of the organizing process. PICO's structural position is enhanced by what WOOD (2002) calls the "primary community" that is present in the congregations. "PICO's close structural ties to the religious institutions of civil society have substantially unburdened the organization of the need to generate meaning and create primary community in members' lives" (p.143). [22]

As members of a group doing community organizing, the participants in this research are engaging in democratic processes that are inherently conflictual at times. As DEUTSCHE (1996) points out, highly functioning democracies involve competing claims and are certainly not characterized exclusively by harmonious processes in the public sphere as some nostalgic commentators suggest. WOOD writes that faith-based organizing, through its mixture of strategies that involves conflict, counters dominant strands in American culture that seek therapeutic solutions to problems, rather than potentially conflictual attempts to alter structures. "Political elites rarely welcome new contenders for political power, so conflicts arise as challenger groups push to overcome entrenched opposition from powerful groups" (WOOD, 2002, p. 202). The interviewees in this study communicated about the role of conflict in the exercise of power. One respondent offered the following assessment of the organizing process: "It is not a clean thing. It is a messy thing. There are terrible decisions that are involved." [23]

Conflict operates in community organizing at the intraorganizational level (between members of the group, e.g. CHAVES, 1993) and at the interorganizational level (between members or representatives of the group and outsiders/members of other organizations, e.g. HARDY & PHILLIPS, 1998). The strategies of community organizing often provoke interorganizational conflict, and the nature of the democratic processes operating within the organization ensures some intraorganizational conflict, although descriptions of the latter were far fewer in the interviews. Conflicts can be seen as both naturally occurring and necessary, or as the result of intentionality. Conflict resolution studies show that constructive resolution (to at least the partial satisfaction of involved parties) of conflict is possible (KEMPF, BAROS & REGENER, 2000). [24]

The conflictual nature of organizing involves interorganizational confrontation if a powerful structure is blocking a desired change. Once a "target" (the term designating the relevant public official, decision maker, or leader) has been pressured and has made a concession, the functioning organizing group continues to ensure that promises are being kept and that public figures are held accountable for their decisions regarding the issue. One interviewee described this ongoing process as follows:

"Everyday pushing, pushing, pushing. Okay, how much did you get done? How much more do you need to do? And if they don't do it within the limit that we have, well we'll have to raise hell, you know, and find out why not and keep after them. If they want our votes for the next election, then they have to do their job this year and then we'll have more people to vote for them next year when your election comes up again. That's how we're doing it." [25]

This "raising hell" concept is certainly in line with ALINSKY-style organizing. The fact that interviewees have experience with prolonged public conflict speaks to the health of the organizing process in this research setting. Among participants, there is a definite sense of the controversy of their activities.

"I mean we've been called Communists and things like that in the newspaper that we have, or Nazis … because we're upsetting the apple cart, you know. We're questioning our officials. We're challenging. So sometimes that's what happens. And we don't like to do that, but that's what we have to do. And it works sometimes. Sometimes it doesn't work." [26]

More than this, some respondents have a strong sense that the conflict surrounding their exercise of power may involve a certain amount of risk and personal sacrifice. Many engaged in the work are not only willing to acknowledge those risks, but consider them important dynamics for making change. Their understanding allows participants to find meaning and purpose within such conflict.

"There are some real costs. People pay with their lives for doing things like this. And that's really true. To say that … that's the case with all progress, however … Who's going to live and who's going to die? Well, there isn't anybody in town except [our organization] who can begin to deal with those issues. The other not-for-profits associated with affordable housing have no basis whatsoever to try and begin to even bring anything to that. They would avoid the question. So what I would say … that's why [our organization] is exceptional and that's why their work is so very, very important." [27]

If the organization can be said to be exercising power through conflict, there is also indication that individuals feel empowered regarding interorganizational conflict through their identities with the organization. For example, one participant in this research told a story that included the following statement, "I got in their face pretty big time. The two people from the Affordable Housing Board who were present at the meeting became very critical of me afterwards because we don't do that towards city council people. But that's what I thought needed to be done." [28]

Many interviewees comment on the difficulty of the work and the adaptation that is necessary to do it successfully.

"A lot of people just aren't made for this kind of work because it is so long-term and it's hard work and it's not easy. You don't see results the next day. It's not a feel good thing the next day. It's a lot of effort." [29]

The organizing process, then, as described by the participants in this research, is "messy" and "not easy." It requires prolonged participation in order to see results. It requires comfort with conflict, confrontation of power, and, in some cases, prolonged conflict. There are potentially hostile or retributive reactions to this sort of activism, ranging from dramatic accusations in the local press to the perception that violence is a possible form of retribution. [30]

Conflict-based strategies, however, are not always employed, as evidenced by participants who—at least some of the time—focus more on collaboration and partnership than controversy. The following illustrates the advantages of this perspective: "I mean if you come at it in an adversarial way, you're building walls instead of bridges. And the bridges are what make it work." Thus, the adversarial or conflict-ready model of community organizing is subordinated for some participants to processes involving interorganizational collaborations. Many times, collaborative strategies are initially sought, and conflict is a last resort. This type of community organizing does not pursue conflict for its own sake, but does so when necessary to achieve certain ends. It is possible for participants to have extensive organizing experience without encountering the need for conflict. [31]

The network of social ties at the interpersonal level is a key component of what can allow an organization to be resilient. Views on how and under which circumstances the organization should operate are not homogeneous. These divergences sometimes give rise to intraorganizational conflict. In some instances, this internal conflict reaches a stage of incommensurability, which involves one party or another leaving the organization.

"And another gentleman who was pretty active on our LOC [local organizing community] for quite a while and ultimately ended up deciding that he was actually going to go and work on the affordable housing board at the city. Because for him, he wanted to be inside the wheel in the bureaucracy and he thought that was more effective. And some people believe that and then more power to them." [32]

Reports of situations such as this one are rare, however, with most of the intraorganizational conflict seeming to be resolved. It is possible that because the data were collected by interviewing only currently highly active members, they do not capture the less satisfied members who may have left or declined leadership positions. Nearly every instance of intraorganizational conflict is mentioned in the context of faith or spirituality. [33]

The internal conflicts between members of the organization that were discussed during these interviews involved strategy, values, and policy debate. Regardless of specific topic of debate, the intraorganizational conflict is understood by the participants in this research to be governed by a shared understanding of faith and spirituality.

"And we have the capacity to talk about issues that divide us. We had a board meeting a couple of months ago talking through the issue of should we accept or apply for a grant from an openly gay foundation. And there are going to be people on our board who really religiously have a hard time with that, and other people who, even from a religious perspective have thought it through and differ with what most of the traditional mainline churches still teach about that. To be able to have a conversation, a civil conversation about that, where you respect people's differences, where you can see people struggling with that even they believe one thing they're willing to listen to somebody's different opinion and come to a conclusion. That's social capital. That's a network of relationships among us where we can have those conversations and come out with an agreement that everybody can live with." [34]

This ability to collaborate across potentially divisive topics is something that is reiterated several times in the data from these interviews. The relationship between the social capital of the organization and the fact that it is comprised of faith-based institutions enters into this discussion, as can be seen in the quote above.

I think it's the faith aspect because we can subordinate what our own political preferences might be to something that's even more important to us. And I can also believe that even if someone disagrees with me politically, if they come from a faith perspective it's much easier for me to assume that they have thought about this. They've made these decisions conscientiously. Even though we share the faith, they might have chosen to live it out or vote differently or focus on different things when they voted one way and I voted another. [35]

The shared ideological background in a particular faith creates a commonality that subordinates otherwise significant differences in strategy, values, or specific policy opinions, sometimes averting intraorganizational conflict. There is no mention in these interviews of faith or spirituality detracting from the ability of the organization to act as a unified whole. While faith and spirituality tend to act as unifying factors in the internal conflicts, it is less clear that they are operating consistently one way or another in interorganizational conflicts between the organization and other societal forces and players. These external conflict approaches of conflict-readiness and conflict averseness each appear to have associations with faith and spirituality for the participants in the study. [36]

The conflict-averse approach is used to describe interviewees (or, more often, others in the organizations that these interviewees describe) who are uncomfortable with more adversarial approaches in organizing.

"She ultimately decided that it wasn't for her, you know. And many people do. Because for some people it is too, the whole organizing process, it is too confrontational. It's not nice. It's not nice to put your city council folks up there and ask them point blank, will you support something; please answer yes or no. You know, no waffling is allowed. And some people don't feel comfortable with that. They think that, in fact there are some people who would say that that isn't consistent with Christian values. And those of us who are passionate about the process and have been through the process don't feel that way." [37]

There are some members of the organization that feel that a more collaborative approach should be taken when the organization interacts with other sectors of the community. Many processes that end in instances of interorganizational conflict begin with hope for a collaborative solution (see SPEER et al., 2003). This conflict-averse characterization, however, is different, in that the description of it in these interviews appears to avoid conflict as a matter of principle. This is viewed as being "consistent with Christian values" in the quote above. [38]

Both a conflict-averse and a conflict-ready approach to organizing can be legitimated by association with spiritual or faith-based principles. This overlapping rationalization can be seen even in what amounts to substantive divergence in the following two statements:

"I firmly believe the Creator kind of directs me wherever he needs me. And I'm not one who's soft-spoken, by any stretch of the imagination. When I have to speak out, I will."

"She doesn't like getting in people's faces. She's a youth minister. So is her husband. Very religious people." [39]

Many interviewees stayed far from the dogmatism that is sometimes associated with religious views when characterizing their ideological positions. They stated, for instance, that context and, more specifically, other people take precedence over principles.

"Community is extremely important, and the faith community I think is more important than doctrine. Some people do things on principle, and some people do things for people and won't sacrifice people to a principle. And I don't think I would. Maybe that's the basic philosophical difference." [40]

This view that people and community are more important than doctrine and principles can be seen across these interviews. This willingness to place the collective good over the specific religious beliefs of each faith-based institution is related to the issues that are selected by the groups. While there is no particular guiding political or philosophical orientation, the issues that emerge from the process are related to the well being of the collective (including immigrants and the poor) and therefore fall on the left side of the political spectrum. Each issue taken up by the group, though, is addressed individually, and ideological positions are not predetermined. The same leader that provided the quote above illustrated the implications of her view at the interpersonal level.

"I just remember my mother-in-law was so angry with one of her daughters when she married a second time. She divorced her first husband; married a second one and that was just a terrible, scandalous thing to do. But her first husband was not a good person, and the second one was. So that's where you get hung up on the principle and forget the people." [41]

Faith, spirituality, and religion are sufficiently differentially understood, or flexibly interpreted, as to contribute to the rationalization of nearly opposite phenomena. Both conflict-readiness and conflict-aversion can build legitimacy in the spiritual realm. Similarly, divergent political views are accepted if one has exercised reason under the conviction of their values that are established in faith. As WOOD (2002) observes, the larger, federated structure of the organization can accommodate a diversity of motivations and interpretations (p.71), and the congregations tend to keep conflicts separate from their worship setting (p.72). While much of the discourse around faith is apolitical, there are statements that politicize some aspect of faith and spirituality. One interviewee stated that, "the war in Iraq would be one example. There's a huge tradition of non-violence in the very, very early Christian church that we've just virtually lost." [42]

5. Discussion: Power, Conflict, and Spirituality

Power, as it operates in community settings, is multidimensional. The multidimensionality of social power at work in community organizing is captured by GAVENTA (1980), drawing on LUKES (1974) in an analysis of failed attempts at community organizing in the Appalachian Mountains in the United States. GAVENTA describes three instruments of power. The first instrument is the most common conception of power, and is manifested through superior bargaining resources that can be used to reward and punish other organizations or individuals. The second instrument concerns the definition of agendas, rules, and issues in public discourse. This instrument can also construct or eliminate barriers to public participation. Lastly, social power shapes consciousness through information control that affects perceptions used to form identities, myths, and ideology. This third instrument of power tends to be the least visible in operation. It is this instrument of power that is capable of dictating rationality (FLYVBJERG, 2001). [43]

ALINSKY-style organizing is particularly focused on public exercise of power. It attempts to build a public reputation and confront issues in the public sphere. STALL and STOECKER (1998) differentiate the ALINSKY model from more feminist approaches as being a form of organizing that is more "masculinist" and more public. Indeed, in some instances other organizing approaches are designated as "organizing communities," rather than "community organizing." The application of ALINSKY-style community organizing to existing faith-based organizations, as in the current case, blurs the line between these two forms, as the faith-based groups pre-exist the organizing consortium. Additionally the explicit focus on relational elements is apparent in the one-on-one relationship on which the organization is built. PICO has observed that if participants initially come together exclusively because of an issue rather than because of their interpersonal relationships, the ties are not likely to last beyond the focus on the issue (SPEER & HUGHEY, 1995). Nevertheless, the "macho power" (STALL & STOECKER, 1998) element identified in ALINSKY-style organizing is still present in the group's more instrumental undertakings. [44]

Interorganizational conflicts highlight the operation of these public forms of power to punish and reward other individuals and organizations. This is akin to GAVENTA's first instrument of power. The second instrument of power is engaged by group members during the organizing process, often preceding overt conflict. Research by group members, increasing involvement, and conducting power analyses of the surrounding social environment show the use of the second instrument of power. These analyses suggest that the third instrument of power—which shapes rationality and defines what constitutes valid knowledge—is subtly engaged by the participating members of this FBCO. Existing belief systems are adapted in various ways toward the achievement of greater social justice and quality of life for the members of the organization. The differential ways that spirituality is constructed by the interviews illustrates the use of this instrument. [45]

The understanding of community organizing as justice work appears to have increasing appeal to members of faith-based institutions (SLESSAREV-JAMIR, 2004). This is a component of what has allowed the PICO network of community organizations to be successful and to sustain growth over recent decades. While spirituality is a nearly universal component of the understandings of the interviewees, the ways in which it manifests itself are divergent. A central question that has emerged from this analysis is whether there is a qualitative difference in the forms of faith or spirituality that is being used to support both different means and ends. Given that faith can be a bulwark in conflict and a reason for avoiding conflict, that it can be used in support or opposition of nearly any political stance, it is difficult to make the case for a unidirectional influence of spirituality on any variable. This finding builds on the multitude of historical roles of spirituality and religion as motivator in converse processes of liberation and oppression, violence and non-violence, free inquiry and knowledge suppression, etc. [46]

If these data point to any unified functions of spirituality in faith-based community organizing, it is the exercise of the third dimension of power (shaping ideologies and identities) and the suppression, resolution, or avoidance of intraorganizational conflict. The analyses highlight the different constructions of conflict at several levels that are possible in conjunction with spirituality. Our theoretical understanding of power leads us to believe that each of these mechanisms and instruments can be applied for the alteration of power relationships both within the organization and in relation to other groups. Future research should continue to explore the process of faith-based community organizing in terms of power and conflict. A central need is for research that examines these phenomena alongside measures of effectiveness in organizing—across locations and time. [47]

Appendix 1: Interview Schedule

Interview schedule is intended as an aid only. All questions may be used or not used if the conversation dictates. Questions may be modified or asked in any order:

How did you get involved with community organizing?

What were some of your initial experiences/impressions? Stories?

Can you explain the organizing process to me? Sequence of events?

What has been your role in this process? Change over time?

Have you met many people through the organizing process?

What do you hope to achieve through involvement in organizing?

Does organizing relate at all to your faith/spirituality?

What have been some of the biggest successes/failures that you have experienced in organizing?

What are the fundamental issues that drive you/your organization?

Do you feel more powerful because of your role in organizing?

How has organizing affected other areas of your life?

Can you give me an example of how your activity in organizing has affected another area of your life?

Has it changed your view of the way that society operates? Examples?

Has your involvement in organizing altered your role in the neighborhood or your social life?

Do you feel more connected to/distant from the community?

What is your favorite/least favorite part of the organizing process?

1) PICO (People Improving Communities through Organizing) has moved away from the acronym, and is using PICO or the PICO National Network as a name. <back>

2) Inset quotations are from the interview data. <back>

Alinsky, Saul D. (1971). Rules for radicals: A pragmatic primer for realistic radicals. New York: Vintage.

Boyte, Harry C. (1989). Commonwealth: A return to citizen politics. New York: Free Press.

Chapman, Audrey R. (1991). Faith, power, and politics: Political ministry in mainline churches. New York: Pilgrim Press.

Chaves, Mark (1993). Intraorganizational power and internal secularization in protestant denominations. American Journal of Sociology, 99(1), 1-48.

Delgado, Gary (1994). Beyond the politics of place: New directions in community organizing in the 1990s. Oakland, CA: Applied Research Center.

Deutsche, Rosalyn (1996). Evictions: Art and spatial politics. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Dokecki, Paul; Newbrough, John, R. & O'Gorman, Robert T. (2001). Toward a community-oriented action research framework for spirituality: Community psychological and theological perspectives. Journal of Community Psychology, 29(5), 497-518.

Erlandson, David A.; Harris, Edward L.; Skipper, Barbara L., & Allen, Steve D. (1993). Doing naturalistic inquiry: A guide to methods. Newbury Park: Sage Publications.

Fisher, Robert (1994). Let the people decide: Neighborhood organizing in America. Boston: G.K. Hall & Company.

Fisher, Robert & Shragge, Eric (2000). Challenging community organizing: Facing the 21st Century. Journal of Community Practice, 8(3), 1-19.

Fisher, Robert & Shragge, Eric (2007). Contextualizing community organizing: Lessons from the past, tensions in the present, opportunities for the future. In Marion Orr (Ed.), Transforming the city: Community organizing and the challenge of political change (pp.193-217). Lawrence, KS: University Press of Kansas.

Foucault, Michel (1980). Power/knowledge: Selected interviews and other writings 1972-1977. New York: Pantheon.

Flyvbjerg, Bent (2001). Making social science matter: Why social inquiry fails and how it can succeed again. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Gaventa, John (1980). Power and powerlessness: Quiescence and rebellion in an Appalachian Valley. Urbana, IL: University of Illinois Press.

Hardy, Cynthia & Phillips, Nelson (1998). Strategies of engagement: Lessons from the critical examination of collaboration and conflict in an interorganizational domain. Organization Science, 9(2), 217-230.

Kempf, Wilhelm, Baros, Wassilios, & Regener, Irena (2000). Socio-psychological reconstruction-integration of quantitative and qualitative research methods in psychological research on conflict and peace [22 paragraphs]. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung / Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 1(2), Art.12, http://www.qualitative-research.net/fqs-texte/2-00/2-00kempfetal-d.htm [Retrieved September, 2007].

Lukes, Stephen (1974). Power: A radical view. London: Macmillan.

McNeely, Joseph (1999). Community building. Journal of Community Psychology, 27(6), 741-750.

Orr, Marion (2007). Transforming the city: Community organizing and the challenge of political change. Lawrence, KS: University of Press of Kansas.

Peshkin, Alan (1986). God's choice: The total world a fundamentalist Christian school. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

PICO (2004). About P.I.C.O, http://www.piconetwork.org/aboutpico.asp [Retrieved November, 2004].

Queen, Edward L. (2002). Public religion and voluntary associations In Edith L. Blumhofer (Ed.), Religion, politics, and the American experience: Reflections on religion and American public life (pp.86-103). Tuscaloosa: The University of Alabama Press.

Robinson, Buddy & Hanna, Mark G. (1994). Lessons for academics from grassroots community organizing: A case study of the Industrial Areas Foundation. Journal of Community Practice, 1, 63-94.

Rothman, Jack D. (1996). The interweaving of community intervention approaches. Journal of Community Practice, 3(3/4), 69-99.

Rothman, Jack D.; Erlich, John, L. & Tropman, John E. (1968). Strategies of community intervention: Macro practice (6th ed.). Itasca, IL: Peacock Publishers.

Rubin, Herbert & Rubin, Irene (2000). Community organizing and development (3rd ed.). Boston, MA: Allyn & Bacon.

Schneider, Jo Anne (1999). Trusting that of God in everyone: Three examples of Quaker-based social service in disadvantaged communities. Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly, 28(3), 269-295.

Slessarev-Jamir, Helene (2004). Exploring the attraction of local congregations to community organizing. Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly, 33(4), 585-605.

Smock, Kristina (2004). Democracy in action: Community organizing and urban change. New York: Columbia University Press.

Speer, Paul W. & Hughey, Joseph (1995). Community organizing: An ecological route to power and empowerment. American Journal of Community Psychology, 23(5), 729-748.

Speer, Paul W.; Hughey, Joseph; Gensheimer, Leah, & Adams-Leavitt, Warren (1995). Organizing for power: A comparative case study. Journal of Community Psychology, 23, 57-73.

Speer, Paul W.; Ontkush, Mark; Schmitt, Brian; Raman, Padmasini; Jackson, Courtney; Rengert, Kristopher M., & Peterson, N. Andrew (2003). Praxis: The intentional exercise of power: Community organizing in Camden, New Jersey. Journal of Community & Applied Social Psychology, 13, 399-408.

Stall, Susan & Stoecker, Randy (1998). Community organizing or organizing community? Gender and the crafts of empowerment. Gender and Society, 12, 729-756.

Szynka, Peter (2002). Community organizing and the Alinsky tradition in Germany. Retrieved from COMM_ORG: The On-Line Conference on Community Organizing and Development, http://comm-org.wisc.edu/papers2002/szynkag.htm [Retrieved July, 2006].

Tocqueville, Alexis de (2001). Democracy in America (mass market paperback). New York: Signet Classic.

Warren, Mark R. (2001). Dry bones rattling: Community building to revitalize American democracy. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Wood, Richard L. (2002). Faith in action: Religion, race, and democratic organizing in America. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Brian CHRISTENS and Diana L. JONES are PhD students in Community Research & Action at Peabody College at Vanderbilt University.

Paul W. SPEER is associate professor of Human & Organizational Development at Peabody College at Vanderbilt University.

Brian, Diana, and Paul write and conduct research on development, community psychology, action research, participation, community organizing, and power.

Contact:

Brian Christens

Box 90, GPC

Vanderbilt University

Nashville, TN 37203

USA

E-mail: B.Christens@Vanderbilt.edu

Christens, Brian; Jones, Diana L. & Speer, Paul W. (2007). Power, Conflict, and Spirituality: A Qualitative Study of Faith-Based Community Organizing [47 paragraphs]. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung / Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 9(1), Art. 21, http://nbn-resolving.de/urn:nbn:de:0114-fqs0801217.