Volume 21, No. 2, Art. 11 – May 2020

A Taxonomy for Cultural Adaptation: The Stories of Two Academics When Teaching Indigenous Student Sojourners

Jayne Pitard & Meghan Kelly

Abstract: Difficult cultural encounters can impact both student sojourners and academics. In this article we present vignettes of separate experiences of an unforeseen cultural encounter in each of two groups of short-term adult student sojourners and we who taught them: One Indigenous group from Timor Leste entering Australia for a 12-week period, and one Indigenous group from Australia traveling to Greenland for a two-week period. We use a structured vignette analysis (PITARD, 2016) of each critical incident to present specific details of how these intense, unanticipated cultural experiences impacted us, the academics. Within our vignettes we see at work a process for cultural adaptation, which we have developed into a taxonomy to assist other teachers in their experiences with difficult cultural encounters to better understand what is happening as a means for stepping outside their own cultural boundaries.

Key words: cultural adaptation; academics; Indigenous students; cultural fluency; structured vignette analysis; short term student sojourners

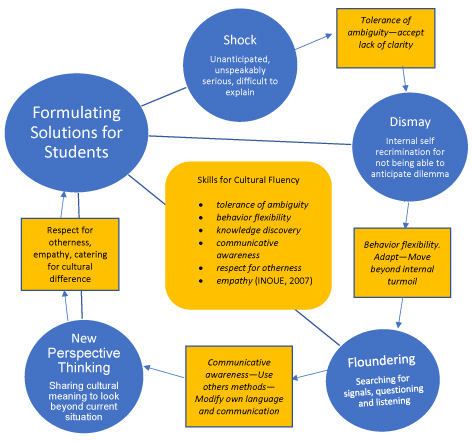

Table of Contents

1. Introduction

2. The Role of Culture in Student-Teacher Encounters

3. Methodology

4. Two Autoethnographic Vignettes

4.1 Group A

4.2 Group B

5. Challenges and Solutions

6. Conclusion

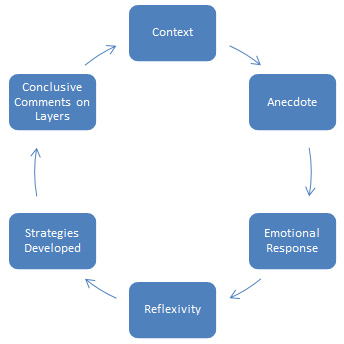

In this article we present vignette studies of ourselves, two white female Australian middle-aged academics from different Australian Universities who have taught adult Indigenous students as short-term sojourners: One group of twelve from Timor Leste (TL) and one group of seven Indigenous Australians from remote parts of Australia. Both groups had experience of, or a heritage of, human cruelty; the Timorese at the hands of the Indonesians (1975) and the Indigenous Australians at the hands of white governments. TL declared independence in 2002 and began the momentous task of rebuilding the nation. The Australian Indigenous population suffered slaughter, dislocation and removal of children (the stolen generation) throughout the history of modern Australia. [1]

We explore a moment of cultural unknowing for each of us through the use of autoethnographic vignettes to expose how cultural misunderstanding faced by the students impacted all group members, in particular us, the academics. We present the challenges the unforeseeable cultural encounters posed for us and share our personal experiences with a view to equipping future teachers so they can improve their responses when they encounter challenging moments of cultural misunderstanding. We achieve this by identifying the phases of our process in moving through our responses to cultural misunderstanding. In analyzing our experiences, our aim is to contribute in a practical way to the literature on cultural interaction and to prepare future teachers of sojourning adult Indigenous students for dealing with unforeseen cultural encounters. [2]

We each have over 30 years of experience in teaching at tertiary level at different universities. The opportunity for this research arose from the commonalities we both recognized when presenting our recent individual experiences at a conference.1) In witnessing each other's presentations we recognized the synergies in the coping strategies we each displayed. With ensuing discussion, we shared a particular event in each program that led to moments of cultural uncertainty, and it is these moments we discuss in this article. It must be noted, the focus of this article is not on the experiences of the student cohort, who in this instance were both groups of Indigenous students. Instead the students experiencing cultural challenges led to a focus on the resultant impact this had on us, the academics, and what we can learn from the academic standpoint. [3]

The overall success of both programs should not be overshadowed by the particularly difficult experiences we bring to this article. As teachers, we found ourselves in situations where we were forced to reflect on our professional practice, our assumptions and biases, and suspend our natural attitude towards our students in order to surmount a disparity in cultural understanding. We do not purport to speak on behalf of all academics who have groups of short-term study abroad students. Our stories and reflections highlight the experience of two teachers becoming the stranger in the group (GUDYKUNST, 2005). This encouraged group decision making to develop coping strategies, which was a positive outcome for all participants. Our aim in this article is to bring our lived experience into the realm of discussion in order to enhance understanding of the coping strategies of academics when they are with students who experience extreme cultural difference, and the subsequent impact this has on the teacher. [4]

We commence in Section 2 with a discussion on culture using HOFSTEDE's (2011) model, then introduce the inherent skills for cultural fluency as outlined by INOUE (2007). In Section 3 we discuss phenomenology and justify our use of vignettes, introducing a structured vignette analysis for revealing our stories. Using autoethnographic vignettes in Section 4 to address our moments of doubt and clarity we place ourselves in a context influenced by external factors. In Section 5 we discuss the challenges we faced and unpack the process we underwent in working through our shock and dismay. Based on our experiences, we develop a taxonomy for cultural adaptation which overlaps with the inherent skills for cultural fluency previously identified by INOUE. Section 6 concludes that our difficult cultural encounters required us to rethink our role, adapt to the situation and expand our cultural understanding in the moment, as the event unfolded. The use of our taxonomy for cultural adaptation can assist teachers to contemplate their own responses to such encounters and raise awareness of the need to be able to adapt in the moment. [5]

2. The Role of Culture in Student-Teacher Encounters

Culture is commonly regarded as a learned collection of general interpretations about "beliefs, norms and social practices" (LUSTIG & KOESTER, 2006, p.142); of a "historically shared system of symbolic resources through which we make our world meaningful" (HALL, 1959, p.4); a "collective programming of the mind" (HOFSTEDE, 2011, p.3) that differentiates a community of people from other communities of people. The work of anthropologist HOFSTEDE in the 1970s defined differences in countries considered to be high context and low context cultures. His model of six dimensions of national culture captures the differences between high context and low context cultures. HOFSTEDE's six dimensions of natural culture are power distance (power is distributed unequally), uncertainty avoidance (a society's tolerance for ambiguity), individualism versus collectivism (the degree to which people in a society are integrated into groups), masculinity versus femininity (the distribution of values between the genders), long term versus short term orientation (perseverance, thrift, and having a sense of shame versus respect for tradition, saving "face" and personal steadiness and stability), indulgence versus restraint (gratification of basic and natural human desires versus regulation of gratification through strict social norms). [6]

HOFSTEDE's model provides a framework for organizing data to highlight the perceived differences between cultures. It offered us a lens through which to analyze data gathered through our vignettes, particularly in identifying Indigenous cultures as high context, and modern Australia as low context. As evidenced in our vignettes, power inequity also presented as a barrier to cross cultural communication as the students deferred to our position as their teachers. HOFSTEDE argues that although certain aspects of culture are actually observable, their meaning may be vague or ambiguous. He contends that the interpretation of these practices gives them their cultural meaning. What is acceptable to one group of people can be absolutely offensive to another. He states that although certain aspects of culture are physically visible, their meaning is invisible. Their cultural meaning "lies precisely and only in the way these practices are interpreted by the insiders" (1991, p.8). [7]

HALL (1983) explains that people from high context cultures employ coded messages to convey information and are more influenced by situational cues such as facial expressions and context, whereas people from low context cultures transmit information directly and rely heavily on verbal and written communication. The cultural differences between high and low context are used to frame the groups of participants in this research. It should be noted however that the research of HOFSTEDE and HALL has been progressed by researchers over the decades, which has the benefit of offering greater insight for reflection on our experiences. In addition to awareness of several dimensions of culture including high and low context, we draw on the theories of cultural fluency which emphasize reliance on inherent skills required to communicate efficiently across cultures. INOUE (2007, n.p.) identifies skills which constitute cultural fluency as:

"tolerance of ambiguity (the ability to accept lack of clarity and to be able to deal with ambiguous situations constructively)

behavior flexibility (the ability to adapt own behavior to different requirements/situations)

knowledge discovery (the ability to acquire new knowledge in real-time communication)

communicative awareness (the ability to use communicative conventions of people from other cultural backgrounds and to modify own forms of expression correspondingly)

respect for otherness (curiosity and openness, as well as a readiness to suspend disbelief about other cultures and belief about own cultures)

empathy (the ability to understand intuitively what other people think and how they feel in given situations)." [8]

In the discussion of our vignettes later in this article, we highlight the requirement for all of these skills to be activated in responding to the situations with which we were confronted. But first, we discuss our methodology as it relates to our data and analysis. [9]

The shared experiences presented in our vignettes are portrayed as open and transparent reflections of a difficult cultural encounter. In presenting and analyzing these encounters we have used phenomenology as a basis for reflecting on our lived experience and to determine how our understanding of these encounters was shaped. HUSSERL (1970 [1936]) is often credited with developing the concept of phenomenology (FRIESEN, HENRIKSSON & SAEVI, 2012; LAVERTY, 2003; SCRUTON, 1995; VAN MANEN, 2014.). He contended the "life world" is understood as what we experience pre-reflectively, without the benefit of categorization or conceptualizations, and often includes what is taken for granted or considered as common sense. Returning to re-examine these taken for granted experiences underpins phenomenology with the intention of discovering new meaning. [10]

Enlarging on this theory, hermeneutic phenomenology fostered by HEIDEGGER (1962 [1927]) claims that to be human is to interpret. Therefore, meaning is not something that is final and stable, but is continually open to new insight through revision and reinterpretation, through coupling the study of the experience with its meanings. HEIDEGGER claimed an investigation of consciousness is necessarily influenced by the historicity of background of both the researcher and the participants, as pre-understanding is not something a person can step outside of or put aside. In fact, the assumptions and expert knowledge of a researcher can be valuable guides to hermeneutic research and can make the research a meaningful activity. HEIDEGGER asserts there is co-constitutionality in hermeneutic phenomenology, where the meanings arrived at, by the researcher, are a merging of the meanings articulated by both participant and researcher within the focus of the inquiry (KOCH, 1995). LOPEZ and WILLIS assert that rather than seeking purely descriptive interpretations of the real, perceived world in the narratives of the participants, a hermeneutic phenomenologist will focus on seeking out the meanings of the individuals' experiences and how these meanings influence the choices they make. "This might involve an analysis of the historical, social, and political forces that shape and organize experiences" (2004, p.729). DERVIN's (2003) emphasis on context in the pursuit of understanding the lived experience is re-enforced here. [11]

Using a hermeneutic (interpretive, descriptive) phenomenological approach (VAN MANEN, 1990) to studying the lived experience, we each recall an impactful moment where our students were confronted with a cultural situation that impacted on us (the academics) and which we had difficulty in understanding and negotiating. Exposing these experiences places a spotlight on us as teacher, and the need for us to adapt in the moment to challenging situations. At its core, this article is animated by an interest in understanding how we responded to the cultural challenges of working with students whose cultures are different from our own. [12]

We use autoethnographic vignettes to place ourselves at the center of a cultural interaction with our students as we explore and interpret the impact of the experience on us. The process of authoethnography involves writing about and analyzing selected epiphanies that stem from interactions involving being part of a culture (ELLIS, ADAMS & BOCHNER, 2011). CHANG (2007) states autoethnography is an ethnographic inquiry where the source of primary data is the autobiographic materials of the researcher. She argues that "autoethnography should be ethnographical in its methodological orientation, cultural in its interpretive orientation, and autobiographical in its content orientation" (p.207) and that autoethnographers should emphasize "cultural analysis and interpretations of the researcher's behaviors, thoughts and experiences in relation to others in society" (p.207). ALEXANDER (2005) confirms autoethnography "engages ethnographical analysis of personally lived experience" (p.423). ELLIS and BOCHNER (2000) contend the development of this genre of research has been driven by a desire to produce significant, accessible and evocative accounts of personal experience in order to intensify our ability to empathize with people who are different from us. Autoethnography permits us a wider research lens with which to study our lived experience as it allows the researcher's influence to be acknowledged as it accommodates and even embraces subjectivity. The vignette examples chosen for this article are not necessarily representative of other indigenous study groups; however, they have been chosen for their ability to reveal what we, as academics, were unable to know prior to our experiences, relaying both the circumstances of the experiences (the context) and a layered account of the effect it had on us (RONAI, 1995). [13]

Our vignettes are framed by a structured vignette analysis (PITARD, 2016) with five stages of recollection to connect the social to the cultural by exploring the self and the group within the cultural context. These include: context—an overview to inform the anecdote, to bring the reader on the journey; anecdote (within the vignette) written in the first person in the present tense to give voice to the unconscious deep sensations grounded in experience (SHIN YU, HARRIS & SUMNER, 2006) by each of us at the time of impact; emotional response—initial emotional and physiological responses to the experience; reflexivity—an analytical exploration of our reflexivity to expand our understanding of an interaction between the academic and the culturally different other, and how this progressed our understanding of the needs of our students; and finally, strategies developed which illuminate the progression towards solutions.

Figure 1: The framework for our structured vignette analysis (PITARD, 2016, §10) [14]

The anecdotes within the vignettes are written in the present tense as a means to recreate the epoche, the pre-reflective moment (VAN MANEN, 2014). They are presented in italics to distinguish them within the vignettes, as our anecdotes are central to the telling of our story. In our vignettes we recall and record our experiences of a critical incident to examine a cultural confrontation which invoked a turning point in the communication between the students and us. It should be noted that this analysis occurred after the student sojourners had completed their study tours. For this reason, the reliant source of data are the deep, post-experience recollections, through a structured vignette analysis, of each academic. These recollections are not meant to be regarded as factual statements as witnessed by all involved. Rather, we convey the essence of the experience through reflective intuition so that rather than hearing what we already know (HEIDEGGER, 1971 [1959]), we reveal the essence of the shock of recognizing our failure to know. [15]

4. Two Autoethnographic Vignettes

The data recorded in the following two structured vignette analyses were recorded individually by us and reflected upon after both sets of students had returned to their homes, some in remote places. The distance and difficulty of communication with these students precluded the opportunity to contact them to discover their versions of these incidents. We feel this does not detract from the data we provide here, as we categorically inform our readers that this is our own interpretive research undertaken from the standpoint of the academics. Each vignette provides the opportunity for us to present our own analysis of these experiences which serves as the foundation for reflexivity as a means of improving practice (ANGELIDES & GIBBS, 2006). [16]

We each led a group of students which, for the sake of identification, we have labeled Group A and Group B. Group A (led by PITARD) was a group of twelve Indigenous technical and vocational education and training (TVET) teachers, principals and policy makers from Timor Leste (TL), who visited Australia for twelve weeks to undertake a post graduate certificate in vocational education and training (VET). On-going project work and assessment continued when this group returned to TL. Group B (led by KELLY) was a group of seven undergraduate Indigenous Australian students from across Australia who visited the Nordic region to engage with other first nations peoples. [17]

All members of the groups were adults in tertiary education, ranging in age from early twenties to 65 years of age. At least four members of the TL group had previously studied in Australia, and one had studied in Switzerland, demonstrating their experiences of traveling abroad. Separate structured preparation was undertaken for each individual group by professionals who had experience in each culture. PITARD traveled to TL for one week to meet the students and the Minister for Education in TL to both experience the culture and context, and to gain an understanding of anticipated outcomes. It is important to note that members of Group A may not have been familiar to each other, while members of Group B were familiar to each other, having studied together at the Institute of Koorie Education, Deakin University. All students traveled as a group, not independently. Group B was accompanied by three academics, one of whom is an Indigenous academic from the Institute of Koorie Education, and KELLY, who was a contributor to the Australian Indigenous Design Charter, a ten step best practice protocol document for designers when working with Indigenous knowledges. Accommodation was arranged for both groups and, in the case of Group A, a stipend was deposited into a bank account each fortnight. [18]

The twelve students from TL were employed in vocational education, either through teaching in, or managing, a VET training college, or working on VET policy in the Department of Education in TL. The oldest student was 65 and the youngest 28 years of age. I had sole responsibility in delivering the graduate certificate in VET at the university where I teach in Melbourne, Australia. On behalf of the university and as their teacher, I opened individual bank accounts for the students to receive their weekly stipend which gave them the independence to manage their own finances. I provided them with public transport cards and showed them how to board a tram and train and provided them with maps of the city. They were each given a mobile phone so they could stay in contact both with me and with each other. I walked them around the local area and through the local fresh food market where they could shop on their walk home from the university. [19]

They had been in Melbourne for two weeks when a university colleague, with years of teaching experience in both Melbourne and TL, invited them on a Saturday afternoon visit to the Centre for Education and Research in Environmental Strategies (CERES), a community environment park. She told the students how to catch public transport to the venue and said she would meet them there. On the following Monday morning, I walked into our classroom at 9.30am and, as was my custom, asked them how their weekend had been. [20]

I feel immediate discomfort in the room. As I look at the faces of the students, none of them make eye contact with me. Recalling the proposed Saturday excursion with my colleague, I ask how their visit to CERES went. I am greeted by silence, before they look towards one of the better English speakers, who states they had a problem during their visit. As I look from student to student I see downcast eyes and begin to understand they are embarrassed.

"What happened?" I ask.

The appointed spokesperson explains that my colleague, Anne (pseudonym), suggested to the students they should go into the café and get themselves some lunch. She did not accompany them. They became confused and uncertain as they watched others choosing food and then paying for it.

I remain silent and unmoving as I try to understand what they are telling me with serious, unsmiling faces. Confusion must be evident in my facial expression and body language as they struggle to convey their message, but none of them is able to find their voice.

Finally, I ask: "What is the problem with that?"

The spokesperson says: "In Timor, if someone invites you to spend the day with them it is polite to provide food and drink."

"Oh," I respond. "In Australia that only happens if someone invites you into their home. If they take you on an excursion they would not expect to buy your lunch."

Blank faces. Silence.

"It doesn't matter," I say. "Anne would not be offended if you bought your own lunch."

Silence, eyes downcast. I sense there is something missing in this conversation, so I persevere.

"There is something you are not telling me? You all seem embarrassed."

Slight movement occurs and they all look towards the student who had spoken previously.

"We could not buy lunch because we did not take any money with us." [21]

I was careful not to express my shock. I chose to remain silent for several seconds to allow my mind to process that these students went the whole day without eating, because they were too embarrassed to express to my colleague that they did not bring money with them. [22]

I asked why they did not take money with them and the students explained that in Timor very few people carry money, and they personally rarely carry money with them. They live in communities where they eat in each other's homes, they do not pay for transport (there is no ticketed transport system), they do not buy much, except food to take home and cook. If someone invites them to an event, it is expected that the person who invites them will supply food and drink. Their uncertainty during their first excursion weighed heavily on them. My internal dialogue started in earnest as I berated myself for not foreseeing how this situation might occur. I had ensured they had money, that they knew how to withdraw money from the automatic teller machine (ATM) as there was only one ATM that I knew of in Dili, the capital of TL, and that they knew where and how to buy food for themselves. I had overlooked the protocol of what to expect in being invited on an outing. It was apparent to me that my colleague could not afford to buy lunch for twelve hungry adults, but what was not apparent to me was that the students had not been able to envisage that lunch would have to be bought for them. On reflection, I believe they anticipated a picnic style lunch, where my colleague would prepare food and bring it along with her. I felt dismayed at my insensitivity at not being able to anticipate this situation. I tried to hide this from them, to grapple with my self-recrimination without it showing in my facial expression and body language. I tried to stand still and to keep them in focus. [23]

The students supported each other through this difficult experience by deciding, as a group, to appoint a spokesperson to raise the issue in class. However, what became apparent to all of us was the disconnect between the students' expectation of the invitation and my anticipation of their enjoyment of their day out. We sat perplexed, and I realized I could not have anticipated this situation. I had to act immediately to relieve their discomfort and to move us all forward to a discussion on cultural difference. [24]

Our subsequent group conversation revealed broader cultural concerns they had discussed amongst themselves. Even though we had undertaken an orientation program, the level of discomfort was confronting for me. Revealing that not knowing who to greet (neighbors were not responding when greeted), having too much choice in supermarkets (amongst other anxieties), it emerged that their greatest fear was how to cope in an emergency without a community to turn to. Hospitals in TL are reserved for the extremely ill, and it is custom for the elders in a community to provide wisdom and knowledge to deal with crises. Understanding the nature of our emergency services and that they can be contacted by telephone day or night provided the students with huge relief. Speaking animatedly in Tetun, the students were able to convey to me their confusion and fear through the nominated student spokesperson, allowing me to re-align with the group to resolve cultural confrontation. This proved to be a breakthrough as the students demonstrated their commitment to support themselves by removing the guesswork in coping with the cultural shift they were experiencing. [25]

The Visual Communication Design Study Abroad Program was the first study abroad program for the Institute of Koorie Education (IKE) at Deakin University. IKE students travel from different rural, regional and metropolitan locations around Australia to attend IKE which is based in the Waurn Ponds Geelong Campus of Deakin University. Students participate in intensive workshops and live on campus for one or two-week sessions, four or five times a year. Students were accompanied by three academics, two of whom were new to the group and were the only non-Indigenous members. The third academic was an Indigenous professor from the institute. As organizers of the study abroad program, my colleagues and I coordinated two pre-departure meetings to discuss the aims of the program and prepare students for their travel experience. The program duration was ten days in total with time spent in Denmark and Greenland, plus a day visit to Sweden. The temperatures were expected to be extremely cold with subzero temperatures experienced in Greenland. Only one student had traveled abroad previously, the other six students had to apply to the Australian Government for passports. Again, the oldest student was over 60 years of age and the youngest was in her early 20's. Considerable time during the pre-departure sessions was spent calming nerves, talking through anticipated events, and preparing the students for the different climate. [26]

I have conducted a number of international study abroad programs; however, the level of excitement and anticipation was something I had not previously experienced. One student was bought to tears with the emotional realization that she was going to travel abroad when thinking that this would never be possible. In group discussions, the fear of what students would encounter and how they would cope, clearly articulated in conversations, was mitigated by the reassurance that at no point would anyone be alone. The students agreed to support each other in this experience. [27]

Early in the study abroad program the group of students visited THE NATIONAL MUSEUM OF DENMARK in Copenhagen. The museum houses many artifacts from around the world in their ethnographic collection. The museum promotes a voyage of discovery through collections including Oceania (2017), placing Australian Aboriginal artifacts from hunting and daily life in the Oceania category. The students were free to roam around the spaces and spent considerable time in the Oceania exhibition. Many artifacts were from the local regions of the students and in particular the two Torres Strait Islander students could identify materials their families currently use, taking great joy in sharing their stories. However, some artifacts were not correctly curated. Items that were not to be viewed by men (women's only business) and others not to be viewed by women (men's only business) had been placed together. This viewing had enormous impact on one female Torres Strait Islander. [28]

I hear fear in her voice as she asks:

"Can I go back to the hotel for a shower?"

"As soon as possible," she adds.

The other students linger. I sense there is something significant occurring but I do not understand the intensity in this student.

Thinking of our plans for the rest of the day and feeling dismayed at this disruption, I ask "How soon? Can we continue with our schedule for now?"

The distress in her face is confusing me as I proffer alternative plans which incorporate a shower later in the afternoon. An Indigenous Elder in the group quietly explains to me the importance of the shower. The student needs to cleanse herself having seen things she should not see.

"The rest of the group will understand."

Working with the Elder we consider a number of alternative plans. The discussion results in us taking the group for lunch near the hotel where the group can settle while the student showers. The students agree to this solution. [29]

I experienced a rush of emotions over this incident. Questions swirled quickly around my mind, followed by a re-evaluation of my response. Once the reasons were fully explained, I felt embarrassed by my initial responses. I had not made any cultural connection with the student's request for a shower. I was concerned I did not immediately trust the student's motives when I know her to be an honorable and dependable member of the group. I was disturbed that mistrust even entered my head when logically this was not reflective of past student behavior. How could I not read this as a sign of another pressing matter? I felt greatly inadequate when I did not understand the importance of cleansing herself of what she had seen and was embarrassed by my inability to immediately respond compassionately to the student who had faced a confronting experience. I reflected on whether I could have visited the site earlier to identify probable issues; however, I would not have recognized the exhibition was poorly curated. I was concerned I had no ability to warn the students prior to their entering the museum and was embarrassed that my behavior was reflective of the exhibition, where the dominant cultural group clearly demonstrated its lack of cultural understanding to Australian Indigenous communities. I felt as erroneous as the exhibition itself. [30]

I found I was challenged by my decision-making process as I worked through the number of ways I could address the student concerns. Two key points come to the fore in my mind. Firstly, I have reflected on my behavior at that moment and noted the need to trust and believe in the student cohort. However, impacting this trust was my need to consider the consequences any individual decision would have on the group, so I became more protective of the group than the individual who was in crisis. This is, upon reflection, quite a disturbing consequence of group travel. Secondly, I was concerned with the personal response of the student, and whether or not women's business and the response to the exhibition should remain in confidence. I did not feel it was my position to raise the issue with the other group members and I did not have the right to interpret her opinion if I was required to explain the issue to others. I therefore felt disempowered and left in an awkward position where I was not sure of my options for finding solutions. [31]

The Indigenous Elder took the lead on navigating the student cohort as I navigated the individual student requirements. I followed up with the National Museum in Denmark and they were apologetic but declared they were unable to curate the exhibition without Australian Indigenous input. They explained the collection was very old and established prior to more appropriate curatorial considerations and we were the first to inform them of this issue. They invited us to return and provide them with guidance but we had moved on to other destinations. [32]

The cultural encounters revealed in our vignettes were unable to be predicted by us. This is confirmed through our telling of these stories. Whilst our lack of ability to predict these situations may be questioned, our experiences resulted in a moment of extreme cultural distance from our students; a sense of unknowing, of floundering, of regret. PITARD had carefully planned her introduction to Australian life to ensure her students had the tools and knowledge to navigate their journey into a world of different cultural and social norms. She assumed that four students having experience of studying in Australia, all students being paid a stipend and having access to an ATM, conveyed to her students that carrying money was the cultural norm in Australia. In addition, she was aware that her colleague, Anne, who met them at CERES for their day out, already knew some of the students through her previous years of work in TL, and understood the cultural customs in TL. Anne too presumed the students would have the money to purchase their own lunch and that the experience of those students who had previously studied in Australia would guide the group. KELLY took her students to an Oceanic exhibition at a museum in Denmark, which she assumed would be curated sympathetically to align with the cultural sensitivities of her students. Even if she had visited the exhibition prior to taking her students, she would not have been able to recognize the inaccuracy in curating. This is reinforced by the fact that her Institute of Koorie Education colleague accompanying the group also did not notice that the exhibition was incorrectly curated. [33]

GUDYKUNST and NISHIDA (2001) believe the inability to predict the consequences of intercultural communication often results in apprehension, due to a lack of understanding of the implied rules by which the interaction will occur. GUDYKUNST (2005) regards uncertainty in intercultural communication as a cognitive phenomenon; an expanded state of consciousness where we are on alert as our anxiety level is heightened. This can result from an inability to predict attitudes, feelings and behavioral outcomes as a result of not being able to read both verbal and non-verbal cues. In explaining his theory of uncertainty and anxiety in intercultural communication (anxiety/uncertainty management [AUM] model), GUDYKUNST contends that to reduce uncertainty and anxiety, a person must have the communicative tools required to gather information in order to commence adaptation. As witnessed in the vignettes, we became aware that our inability to predict the impact of cultural difference on our students resulted in our own cultural anxiety in the moment, but our communicative and other cultural fluency skills allowed us to move forward towards resolving the issues. [34]

To assist us to understand the process we both used to move through these difficult cultural encounters, we have developed a taxonomy by mapping the skills needed for cultural fluency (INOUE, 2007) against the phases we experienced in these difficult cultural encounters. We provide both a written explanation, and a diagram to foster further understanding.

Phase 1: Shock in realizing there is an unanticipated issue that is so serious, it is almost unspeakable. Hearing the issue from the mouths of our students. Demonstrating tolerance for ambiguity by accepting the initial lack of clarity in what our students were trying to convey to us and questioning for clarity in an empathetic manner.

Phase 2: Dismay can be defined as distress caused by something unexpected.

Understanding the seriousness of the issues sent our internal voices of self-doubt and recrimination into overdrive in blaming ourselves for not anticipating these difficulties. Here we demonstrated our behavior flexibility by moving beyond the internal turmoil, returning our focus onto our students and their needs.

Phase 3: Floundering can be defined as struggling mentally; showing or feeling great confusion. We were floundering in the moment of shock and dismay. We found ourselves searching the faces of our students for signals as to how to overcome these issues because we did not have the answers within ourselves. Here we practiced communicative awareness and knowledge discovery through questioning and listening, understanding the implications of cultural difference for them, from their perspective.

Phase 4: New perspective thinking occurred after we listened to both the students in Group A and the Elder in Group B.

PITARD was enabled by her students to think beyond the current situation to address other possible future difficult encounters for her students. She listened to her students to discover the reason for their silence and stayed tuned to her students as they revealed a list of anxieties around our taken-for-granted processes in Australia.

KELLY was able to build her response on the Elder's explanation of the need for her student to cleanse herself immediately. She listened to the Elder who explained the situation and she turned to the traumatized student with a new understanding.

We realized how much we didn't know, and understood how much we took for granted of what constitutes being prepared in catering for cultural difference. We are indebted to these students for sharing with us their cultural meanings, as this assisted us in suspending our doubt about the urgency and authenticity of their needs, and to align with the group to find solutions.

Nothing remained the same for either us or the students after these conversations. A new meaning had evolved.

Phase 5: Formulating solutions was the final stage in the process of consulting with the group so that together, we could devise a plan for overcoming the stressful situations experienced by the students. This involved empathy in understanding and planning for contingencies that may arise in the future.

Figure 2: A taxonomy for cultural adaptation [35]

Our skills in cultural fluency (tolerance for ambiguity, behavior flexibility, knowledge discovery, communicative awareness, respect for otherness and empathy) enabled us to move through the moment of impact towards cultural bridging; however, our residual dismay at having failed our students is still very powerful within us. BENNETT (1998) contends this process of adjustment and adaptation is unique to every individual and will depend on the psychological personality of individuals and their ability to manage their experiences and reactions. In any study abroad program, there are many variables at play and, as SOBRE-DENTON and HART (2008) argue, a lack of individual attention and ease of cultural adaptation can be an issue when academics and sojourners are faced with extreme challenges. In this adjustment phase GUDYKUNST (1988) emphasizes the necessity of recognizing that at least one of the participants is a stranger. He argues that although the stranger is situated within the group at the time of the intercultural communication, he/she is outside the group in terms of cultural alignment. Here we consider the power inequity which existed between the students and the academics. In both Indigenous cultures, power distance (HOFSTEDE, 2011) renders the teacher as deserving respect, one not to be questioned. Inexorably, this power distance also renders the teacher as the stranger within the group, where the stranger is basing her responses to the group or culture on known or previously identified interactions within her own culture, often referred to as implicit theory or habitual reactions. As the stranger realizes her known ground rules or responses of habit do not apply with those from another culture, disorientation can result, creating heightened awareness of situation-behavior sequences (GUDYKUNST, 2005). The need to re-align with the group in order to resolve an ill-informed cultural encounter becomes the imperative. Our re-alignment with our groups was imperative in moving towards a solution. For Group A, PITARD re-aligned herself by asking the students to express and discuss all the fears and anxieties they were experiencing in their own adaptation to a new culture, placing herself as an outsider in the discussion. In the case of Group B, KELLY listened intently to the advice proffered by an Elder, again placing herself as an adjunct to the event, and together the group found a solution to the dilemma, [36]

By the very nature of our vocation and our years of experience as teachers, we believed we had the skills required to manage cultural adaptation. In fact, we believe we exhibited the skills for cultural fluency in our responses to the cultural miscommunications which occurred, but not before the impact of the moment led us to places of confusion and dismay, and the regret at having failed our students. Based on the experiences presented, we did not have the ability to predict or to anticipate the impactful cultural miscommunications which led to high uncertainty and anxiety experienced by both the students and us. For instance, we were forced to rethink our understanding of what it means to have a shower. For KELLY, it meant cleansing the external body. For the Indigenous person it means something else, an internal cleansing. [37]

We share our stories so other academics, when faced with unanticipated miscommunications in circumstances of cultural differences, might recall our stories and immediately put into use the skills of cultural fluency and cultural adaptation as outlined in our taxonomy. This may help to avert the confusion and dismay experienced by both our students and ourselves. [38]

In preparation for both programs, despite considerable time being dedicated to discussing the possible cultural impact on the students, we now identify that a failing in our preparation was that neither group sufficiently anticipated how to deal with unforeseen cultural differences between the students and academics. We felt well-prepared. For Group A, PITARD had undertaken research into the recent history of TL and its traditional culture, and had visited TL for one week prior to the students arriving in Australia in order to develop a greater understanding of the cultural background of her specific students. She felt she had acquired sufficient knowledge to guide her students through cultural difference. For Group B, KELLY had experience teaching Indigenous Australians and was a contributor to the Australian Indigenous Design Charter, a ten step best practice protocol document for designers when working with Indigenous knowledges. In addition, one of the accompanying academics was an Indigenous academic from the Institute of Koorie Education at Deakin University. [39]

We felt prepared, and in some respects we were. However, it is clear in retrospect that we had underestimated the extent to which we and the students were strangers to each other—how both were coping with a different way of being, not only within the different cultural environment, but also within the group itself. Our experience-based knowledge was insufficient for understanding at a deeper existential level the implications of what it meant to have a different history, background and culture. How we experienced our moments together, what we felt and thought, were—as in any human encounter—relative to who we are, reflecting the circumstances of our lives, the tradition and culture we have inherited. [40]

Through the use of a structured vignette analysis we have had the opportunity to reflect on our own reactions when placed in a situation where our students were confronted with difficult cultural experiences. It is clear now that the practices we took for granted in our culture blinded us to the other person's positioning. The student groups belong to high context cultures, where context is more important than the spoken word, where community forms the foundation of social structure, as it does in most collectivist cultures (HOFSTEDE, 2011). We, the academics, belong to a low context culture where communication is based on direct, verbal exchange. In other words, our communication styles and skills are based on different premises. The way in which members of each group came together for support and to find solutions to inter-cultural breakdown reflected our high- or low-context positioning, as well as our cultural beliefs. The preparation undertaken by each of us was not adequate for us to understand the personal depth and the cultural complexity of the student responses to unforeseen challenges. The encounters required us to rethink our role, adapt to the situation and expand our cultural understanding in the moment, as the event unfolded. While acknowledging that cross cultural communication is a two-way transmission, we learned it is not sufficient just to acknowledge this. It must be identified and practiced at a deeper level before academics are confronted with a situation they feel ill-prepared to negotiate. That is the purpose of the taxonomy presented in this paper, which was developed to explain the process as experienced by us in the moment. [41]

What we have discovered from experience is that establishing cultural fluency requires a deeper appreciation of the depth and the complexity of cultural difference than is normally provided in the preparation for teaching short-term adult student sojourners, including how to deal with what cannot be known prior to difficult cultural encounters. Given the impossibility of predicting every nuance of cultural misunderstanding prior to it happening, knowledge of culture is not enough. However, we believe the ability to quickly move through the stages of floundering, dismay and self-doubt is a skill which can be acquired and practiced. Our taxonomy allows us to move beyond bewilderment and gives us a starting point for dealing with whatever happens at these moments of difficult cultural encounters. At an emotional level, it provides the opportunity to overcome the element of initial surprise through anticipation of the likely phases we will move through. At a cognitive level, it may assist academics to avoid being trapped within their own cultural boundaries. [42]

1) We attended the Public Pedagogy Conference, Turning Learning Back to Front, Footscray, Melbourne, Australia, November 29-30, 2016. <back>

Alexander, Bryant Keith (2005). Performance ethnography: The re-enacting and inciting of culture. In Norman K. Denzin & Yvonna S. Lincoln (Eds.), The Sage handbook of qualitative research (3rd ed., pp.411-441). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Angelides, Panayiotis & Gibbs, Paul (2006). Supporting the continued professional development of teachers through the use of vignettes. Teacher Education Quarterly, 33(4), 111-121, https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ795229.pdf [Accessed: February 10, 2020].

Bennett, Janet M. (1998). Transition shock: Putting culture shock in perspective. In M.J. Bennett (Ed.) Basic concepts of intercultural communication: Selected readings (pp.215-224). Yarmouth, ME: Intercultural.

Chang, Heewon (2007). Autoethnography: Raising cultural awareness of self and others. In G. Walford (Ed.), Methodological developments in ethnography: Studies in educational ethnography (Vol. 12, pp.207-221). Oxford: Elsevier.

Dervin, Brenda (2003). Given a context by any other name: Methodological tools for taming the unruly beast. In Brenda Dervin, Lois Foreman-Wernet & Eric Lauterbach (Eds.), Sense-making methodology reader: Selected writings of Brenda Dervin (pp.111-132). Cresskill, NJ: Hampton Press.

Ellis, Carolyn & Bochner, Arthur P. (2000). Autoethnography, personal narrative, reflexivity: Researcher as subject. In Norman K. Denzin & Yvonna S. Lincoln (Eds.), The handbook of qualitative research (2nd ed., pp.733-768). Newbury Park, CA: Sage.

Ellis, Carolyn; Adams Tony & Bochner, Arthur P. (2011). Autoethnography: An overview. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung / Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 12(1), Art. 10, http://dx.doi.org/10.17169/fqs-12.1.1589 [Accessed: February 10, 2020].

Friesen, Norm; Henriksson, Carinna & Saevi, Tony (2012). Hermeneutic phenomenology in education: Method and practice. Rotterdam: Sense Publishers.

Gudykunst, William B. (Ed.). (1988). Language and ethnic identity. Clevedon, PA: Multilingual Matters.

Gudykunst, William B. (2005). Theorizing about intercultural communication. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Gudykunst, William B. & Nishida, Tsukasa (2001). Anxiety, uncertainty, and perceived effectiveness of communication across relationships and cultures. International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 25(1), 55-71.

Hall, Edward T. (1983). The dance of life: The other dimension of time. New York, NY: Doubleday.

Heidegger, Martin (1962 [1927]). Being and time. New York, NY: Harper.

Heidegger, Martin (1971 [1959]). On the way to language. New York: Harper & Row.

Hofstede, Geert (2011). Dimensionalizing cultures: The Hofstede model in context. Online Readings in Psychology and Culture, 2(1), https://doi.org/10.9707/2307-0919.1014 [Accessed: 5 September, 2019].

Husserl, Edmund (1970 [1936]). The crisis of European sciences and transcendental phenomenology (transl. by D. Carr). Evanston IL: Northwestern University Press.

Inoue, Yukiko (2007). Cultural fluency as a guide to intercultural communication: The case of Japan and the U.S. Journal of Intercultural Communication, 15, https://www.immi.se/intercultural/nr15/inoue.htm [Accessed: August 20, 2019].

Koch, Tina (1995). Interpretive approaches in nursing research: The influence of Husserl and Heidegger. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 21(5), 827-836.

Laverty, Susann M. (2003). Hermeneutic phenomenology and phenomenology: A comparison of historical and methodological considerations. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 2(3), 1-29, https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/full/10.1177/160940690300200303 [Accessed: June 10, 2019].

Lopez. Kay A. & Willis, Danny G. (2004). Descriptive versus interpretive phenomenology: Their contributions to nursing knowledge. Qualitative Health Research, 14(5), 726-735.

Lustig, Myron W. & Koester, Jolene (2006). Intercultural competence: Interpersonal communication across cultures (5th ed.). Boston, MA: Pearson Allyn and Bacon.

Pitard, Jayne (2016). Using vignettes within autoethnography to explore layers of cross-cultural awareness as a teacher. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung / Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 17(1), Art. 11, http://dx.doi.org/10.17169/fqs-17.1.2393 [Accessed: May 5, 2019].

Ronai, Carol R. (1995). Multiple reflections of child sex abuse: An argument for a layered account. Journal of Contemporary Ethnography, 23(4), 395-426.

Scruton, Roger (1995). A short history of modern philosophy: From Descartes to Wittgenstein. London: Routledge.

Shin Yu, Miao; Harris, Roger & Sumner, Robert (2006). Exploring learning during study tours. International Journal of Learning, 12(11), 55.

Sobre-Denton, Miriam & Hart, Dan (2008). Mind the gap: Application-based analysis of cultural adjustment models. International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 32, 538-552.

The National Museum of Denmark (2017). Oceania, http://en.natmus.dk/historical-knowledge/historical-knowledge-the-world/oceania/ [Accessed: May 17, 2019].

van Manen, Max (1990). Researching lived experience: Human science for an action sensitive pedagogy. Albany, NY: State University of New York Press.

van Manen, Max (2014). Phenomenology of practice. Left Coast Press, CA: Routledge.

Jayne PITARD currently supervises PhD students in the College of Arts and Education at Victoria University, Melbourne, Australia. Her own PhD research focused on her recent work with Indigenous students from Timor Leste. In her 30 years with Victoria University she delivered professional development to teaching staff, with a focus on experiential learning, and was an integral teaching partner in the Career Change Program, a Victorian Government initiative to train industry experts to teach in secondary schools. She has published articles on phenomenology and autoethnography, and contributed to the Springer (Singapore) "Handbook of Research Methods in Health Social Sciences," edited by Pranee LIAMPUTTONG (2017).

Contact:

Dr. Jayne Pitard

College of Arts and Education

Victoria University

PO Box 14428

Melbourne Vic 8001, Australia

E-mail: jayne@pitard.com.au

Associate professor Meghan KELLY is a senior lecturer in visual communication design at Deakin University and currently serves as the associate head of School for Teaching and Learning in the School of Communication and Creative Arts. In her research, she explores issues surrounding identity creation and representation in a cross-cultural context with a focus on Indigenous communities. Her passion for a global understanding of design extends into her teaching practice and continues to be explored in research projects and design opportunities. Together with Russell KENNEDY, she has written the Australian Indigenous Design Charter: Communication Design, and has traveled to Denmark, Greenland and Sweden to explore its transformation into the International Indigenous Design Charter. KELLY is a member of the Design Institute of Australia (DIA) and the International Council of Design (ico-D).

Contact:

Dr. Meghan Kelly

Associate Head of School (Teaching and Learning)

School of Communication and Creative Arts

Deakin University

221 Burwood Highway

Burwood Vic 3125, Australia

E-mail: meghan.kelly@deakin.edu.au

Pitard, Jayne & Kelly, Meghan (2020). A Taxonomy for Cultural Adaptation: The Stories of Two Academics When Teaching Indigenous Student Sojourners [42 paragraphs]. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung / Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 21(2), Art. 11, http://dx.doi.org/10.17169/fqs-21.2.3327.