Volume 21, No. 2, Art. 7 – May 2020

Capturing Meanings of Place, Time and Social Interaction when Analyzing Human (Im)mobilities: Strengths and Challenges of the Application of (Im)mobility Biography

Julia Kieslinger, Stefan Kordel & Tobias Weidinger

Abstract: In this article, we suggest (im)mobility biography as a method for reconstructing human (im)mobilities and related negotiations of meanings of place, time and social interaction. Based on biographical-narrative approaches and participatory ideals the combination of life history interviewing with a participatory timeline tool is the best fit for capturing individuals' life-worlds over time. After presenting theoretical presuppositions on relational meanings of place, time and social interaction, we provide an overview of biographical and participatory research in the context of human (im)mobilities and sketch methodological origins of the life history interview and the timeline tool. Furthermore, we address issues essential for planning and preparing (im)mobility biography, and demonstrate two different applications of the method in migration contexts in Germany and Ecuador. Subsequently, we present options for analysis and interpretation of textual and graphical data outputs. Keeping in mind strengths and challenges, we consider (im)mobility biography a valuable method for capturing (im)mobile life-worlds as well as contextual embeddedness of individual decision-making on moving or staying. Especially in terms of its participatory orientation, the visualization of migration trajectories facilitates structuration and memorization of life histories, allows for shared analysis even at the interview stage, and encourages participants to reflect on their biographies.

Key words: new mobilities paradigm; migration studies; participatory research; qualitative research; biographical research; life history interview; timeline tool; life-worlds

Table of Contents

1. Introduction

2. Conceptual Thoughts

2.1 Place, time and social interaction

2.2 Biographical research in the context of human (im)mobilities

2.3 Participatory research in the context of human (im)mobilities

3. The Application of (Im)mobility Biography

3.1 Getting started: Planning and preparing sound research on (im)mobilities

3.1.1 Becoming familiar with participants' life-worlds

3.1.2 Actors' involvement: Establishing contacts in the field and working with co-investigators

3.1.3 Joint elaboration of data collection materials with co-investigators

3.1.4 Involvement of participants: Sampling, inter-personal relations and forms of gratitude

3.2 Implementation: Information and data collection

3.3 Data processing, analysis and interpretation

4. Discussion of Strengths and Possible Challenges

Alongside the emergence of the new mobilities paradigm (e.g., ADEY, 2006; CRESSWELL, 2010, 2011; HANNAM, SHELLER & URRY, 2006; SHELLER & URRY, 2006), mobile life-worlds1) have increasingly been addressed by various subdisciplines of the social sciences, while at the same time uneven structures that enable or prevent people from being mobile have become of scientific interest (BAUMAN, 1998). Since the diversity of mobilities, ranging from residential mobility (e.g., migration), to everyday patterns of being on the move for a huge variety of reasons, is widely acknowledged in the social sciences (URRY, 2007), data collection methods often do not adequately respond to this perspective. In an era of mobilities (URRY, 2003), established ways of collecting empirical primary data are also challenged, mostly due to the processual and transformative nature of human (im)mobilities, their complex temporal and spatial dimensions (SALAZAR, 2018), their social meanings and power structures (CRESSWELL, 2010; MASSEY et al., 1993) and group interactions and arrangements (MATA-CODESAL, 2015). Encountering criticism of a sedentarist bias, multi-local or mobile research approaches in particular are presented as promising to capture the complex mobility trajectories and perspectives of various actors in different places (e.g., BÜSCHER, URRY & WITCHGER, 2011; D'ANDREA, CIOLFI & GRAY, 2011; FAY, 2007). They are sparsely applied, however, mostly due to structural constraints, such as limited funding for repetitive and often time-consuming field trips. [1]

In the light of these constraints, we suggest approaching mobile life-worlds and lived spaces elsewhere by means of retrospectives. Such a diachronic research perspective, that accesses their biographies, is able to capture individuals' negotiations between mobility and staying over a period of time. Thus, this life-course approach takes a relational perspective, which is especially relevant since "people's pre-move thoughts and their moving behavior at a given time point cannot be easily understood without some knowledge of their past experiences of (im)mobility" (COULTER & VAN HAM, 2013, p.1054). At the same time, to capture a deep understanding of individuals' life-worlds at a certain moment, a synchronic perspective is needed. The structures of participants' everyday lives, the meanings they attribute to place and their social embeddedness need to be unraveled. By considering their life-worlds, participants can be encouraged to reflect upon past and present places of residence, while uneven structures and power asymmetries between the researcher and the participant can be addressed. [2]

Therefore, in this article, we suggest (im)mobility biography as a method based on biographical-narrative approaches and participatory ideals that combines the research tools of life history interviewing (ATKINSON, 2001; GOODSON, 2017a; JACKSON & RUSSELL, 2010) with a timeline tool (see the time-related method of participatory rural appraisal, described by KUMAR 2002). In particular, we present a participatory instrument of inquiry that is able to capture mobility processes, as well as staying at a certain place for a certain time. Our suggested method is based on a subject-centered approach, focusing on the individual as well as their embeddedness in social interactions, e.g., family or household. To overcome language and cultural barriers and foster powers of recall, verbal sequences are combined with graphical interactions. We present two different modes of application, first in the context of forced migration in rural Germany, using a place-oriented approach, and second, in Ecuador, where complex social network constellations were focused. [3]

The remainder of this article comprises a review of the literature that presents key presuppositions on relational meanings of place, time and social interactions (Section 2.1). Afterwards, we relate this to biographical and participatory research, and illustrate its relevance in the context of human (im)mobilities (Section 2.2). We highlight crucial aspects of the preparation of (im)mobility biography and its implementation, as well as opportunities for data processing (Section 3). We conclude by discussing strengths and challenges of (im)mobility biography (Section 4). [4]

In the course of a qualitative research design, we follow a subject-centered perspective, assuming that individuals construct social meanings. In such a social constructivist approach, the meanings of places, life events and life time(s), as well as the respective social contacts of individuals are of particular interest, whilst people refer to them relationally. We therefore present a state-of-the-art, theoretically informed position on the role of place, time and social interactions in an era of mobile life-worlds. These considerations serve as the foundation for methodological reflections and the development of (im)mobility biography. [5]

2.1 Place, time and social interaction

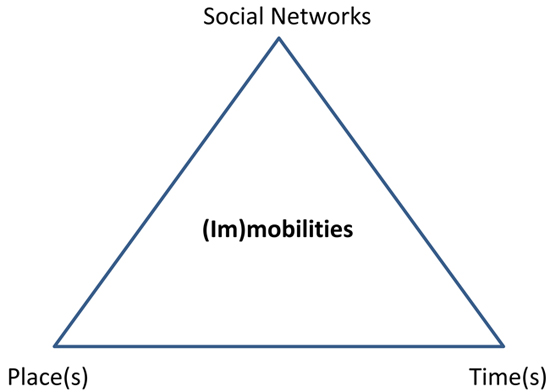

Through the lens of the new mobilities paradigm (ADEY, 2006; CRESSWELL, 2010, 2011; HANNAM et al., 2006; SHELLER & URRY, 2006), being mobile and staying at places are considered to be mutually interrelated (BELL & OSTI, 2010; URRY, 2003). Accordingly, human beings constantly negotiate the meanings of places in different spatial contexts and refer to them in decision-making processes about whether to stay or move on. In this process, time and the length of stay in a specific place enables individuals to have particular experiences. Time, however, is also taken into account in terms of life events and life experiences and therefore refers to a life-course perspective that is often processed in retrospect. Finally, and as a further anchor for our proposed triad of analysis (Diagram 1), we assume that individuals negotiate (im)mobilities within their social networks and interactions and thereby rely on accumulated social capital. As shown in the diagram, negotiations always take place in relation to other times, places and social networks.

Diagram 1: Triad of analysis: Framework of relational negotiations of (im)mobilities [6]

When considering individual and group decisions about residential (im)mobilities, the establishment of place-based belonging can be addressed as an indicator for deciding in favor of a place, i.e., staying. Thus, an understanding of the meanings of place(s) is crucial for knowing whether one will stay or move on. In the social sciences, issues of space and place have increasingly become of scientific interest alongside the spatial turn (SOJA, 1989). Overcoming essentialist conceptions of place, individuals or groups ascribe certain meanings and values to place as a physical material location in space, which is thus seen as a product of social activity (TURTON, 2005). Especially in the context of mobilities, and in particular of the deterritorialization that results, the ways and processes through which individuals develop attachments to places are core issues of scientific discussions (VAN DER VELDE & VAN NAERSSEN, 2011). The development of place-based-belonging, understood as a personal feeling of being at home in a place (YUVAL-DAVIS, 2006), strongly encourages fixity and finally staying (HAARTSEN & STOCKDALE, 2018). Individuals establish and re-negotiate place-based belonging via everyday practices, whilst a strong social attachment to place correlates significantly with duration of residence (SCANNELL & GIFFORD, 2010). Increasing mobilities, resulting in experiences at other places, also emphasize the need to address the meanings of place(s) as relational (MASSEY, 2005; MURDOCH, 2005). Accordingly, places are constructed in relation to other places, including those experienced in the past. As illustrated by the example of lifestyle migrants, for instance, individuals have historically laden imaginaries and narratives of life here and elsewhere (SALAZAR, 2011) and thus construct temporarily contextualized meanings of places. How the meanings of places are constructed was recently analyzed with regard to youth (e.g., MOROJELE & MUTHUKRISHNA, 2012; WILSON, COEN, PIASKOSKI & GILLILAND, 2019), and to the elderly, who ascribe meanings to places according to their physical and mental health (KORDEL, 2015). [7]

Time has to be considered in research on human (im)mobilities since individual notions and understandings of time, e.g., historical time, generational time, life course or personal time, determine decisions about whether to leave or stay, and for how long. Acknowledging the subjectivity of life-time (FILIPP & AYMANNS 2010), Alexandra FREUND and Paul BALTES (2005, p.35) derive age-specific demands upon individuals, so-called "development tasks,"2) resulting from biological changes and/or transitions into new roles. Generating the objectives to which individuals orient their actions, making them elementary for self-regulation and development (BRANDTSTÄDTER & GREVE, 2005), these tasks are often associated with negotiations of (im)mobilities. The decision to stay or to move, however, is also affected by life events and life experiences. Whilst the former can be addressed from an individual or collective perspective, its characteristic sequence forms the life course. The life course approach considers individual lives as unique biographies, which are created by the life events people experience (COULTER & VAN HAM, 2013). Life experiences are strongly related to the intentions and objectives of individuals (HINSKE, 1986), whereby the (dis)confirmation of their own blueprints for action and the means used to realize them are repeatedly reevaluated (FILIPP & AYMANNS, 2010). When people are looking (back) on their lives, they consolidate their experiences and insights into life histories (ibid.). In doing so, they take a relational perspective and especially engage in two temporal dimensions that are permanently synchronized (ALHEIT, 1988): a cyclical daily life time perspective of recent and spontaneous orientation to action, necessary for daily routines, and a linear life time perspective referring to the sequencing of single actions and experiences, which is necessary for subjective continuity and coherence. From the individual's perspective, the determinants of migration might change over a life-time with effects on the likelihood, direction and distance of a move (NÍ LAOIRE & STOCKDALE, 2016). Taking into account the life course perspective, decisions about migrating and staying depend on the perceived ability of the recent abode to provide opportunities for individuals and households in different life domains at different life course stages (KLEY & MULDER, 2010; NÍ LAOIRE & STOCKDALE, 2016). Apart from the emic perspective, life course thinking reveals the interconnection of human (im)mobilities with socio-biographical dynamics and wider contextual factors, including social, economic, political and technological conditions (HOLZ-RAU & SCHEINER, 2015; NÍ LAOIRE & STOCKDALE, 2016). [8]

Individual life courses are always embedded in social structures on a personal (e.g., family, friendships and neighborhood networks) but also on a "systemic" level (e.g., economic, political or administrative organization) (HOLZ-RAU & SCHEINER, 2015; SEWELL, 1992). Therefore, the consideration of social interactions in (im)mobility biographies is crucial to understand decision-making on moving or staying. Two prominent perspectives on social interaction in migration research derive from the different approaches of social capital and networks (GARIP, 2008; GEIGER & STEINBRINK, 2012). The former, defined as a resource of actors in order to realize their interests (COLEMAN, 1988), is inspired by key thinkers Pierre BOURDIEU (e.g., 1983) and Robert PUTNAM (e.g., 1993). The latter developed the distinctions between bonding capital (connection to people of the narrow group), bridging capital (connection to wider society) and linking capital (connections to people in positions of authority). In terms of recently arrived people, "social capital is commonly conceptualized as resources of information or assistance that individuals obtain through their social ties to prior migrants" (GARIP, 2008, p.591). Further, the accumulation of migrant social capital has been related to the cumulative causation of migration where flows become self-sustaining (MASSEY, 1990). At the same time, migrant social capital can eventually dampen the effects of other socio-economic factors (DUNLEVY, 1991; MASSEY & ESPINOSA, 1997). Studies show that the effect of migrant social capital varies for different groups of individuals in different settings (FUSSELL & MASSEY, 2004; KANAIAUPUNI, 2000). An individual's mobility biographies are embedded in social structures like household or family networks in the sense of relationally "linked lives" (BAILEY, BLAKE & COOKE, 2004, p.1618; see also ELDER, KIRKPATRICK JOHNSON & CROSNOE, 2003), where events in the lives of others may influence individual biographies (COULTER & VAN HAM, 2013). This is also related to (im)mobility interactions and arrangements (MATA-CODESAL, 2015) where someone's mobility may depend on somebody else's immobility (BAUMAN, 1998). Such constellations may result in transnational life-worlds (for transnationalism see GLICK-SCHILLER, 1997), transnational social fields (CARLING, 2002), transnational livelihoods (GEIGER & STEINBRINK, 2012) or transnational care chains (HOCHSCHILD, 2000; YEATES, 2012). [9]

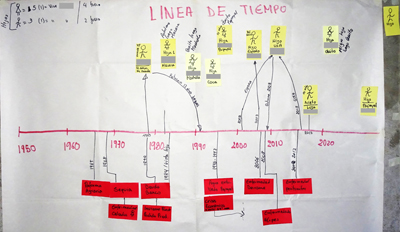

2.2 Biographical research in the context of human (im)mobilities

Key to biographical research is the reconstruction of life histories in a meaningful context, whilst the subject relates events, actions and experiences to others (ROSENTHAL, 1993). According to Roswitha BRECKNER and Monica MASSARI (2019, p.6), "biography constitutes one of the most significant areas of interference between institutionalised social reality and the experiential world of individuals." Biographical approaches and techniques have a long scholarly tradition and have been applied in many disciplines in the humanities, including anthropology, sociology, psychology, education or geography (for an overview see ATKINSON, 2001; GOODSON, 2017b; JACKSON & RUSSELL, 2010; for debates in FQS see KÖTTIG, CHAITIN, LINSTROTH & ROSENTHAL, 2009; RIEMANN, 2003 and ZINN, 2010). Biographies are commonly acknowledged to be socially constructed (e.g., BRECKNER & MASSARI, 2019; HOLSTEIN & GUBRIUM, 2000; SCHÜTZE, 1983) and narratives are always "relational"—that is, they are related to their temporal, spatial and social contexts (JACKSON & RUSSELL, 2010, p.185). Accordingly, temporal patterns may not necessarily correspond to chronological, objective time, but rather follow a subjective time frame (FISCHER, 1982, pp.138-215). Further, biographies are processual and past, present and future perspectives are interrelated and different points of view have developed in different periods of life (FISCHER-ROSENTHAL, 1989; RIEMANN & SCHÜTZE, 1991; SCHÜTZE, 2008). Biographical perspectives also reveal the role of history, memory and tradition in the social construction of place (JACKSON & RUSSELL, 2010; NASH & DANIELS, 2004; RILEY & HARVEY, 2007). The embeddedness of individuals in wider society and the role of relationships, group interactions and memberships are considered constitutive in the construction of biographies (BERTRAUX 1981; BERTRAUX & THOMPSON, 1997). Thus, biographies are constituted by "both social reality and the subject's worlds of knowledge and experience, and (...) constantly affirmed and transformed within the dialectical relationship between life history knowledge and experiences and patterns presented by society" (FISCHER-ROSENTHAL & ROSENTHAL, 1997, p.138, as cited in SIOUTI, 2017, p.181). Consequently, narratives should address the contextual background via grounded conversation and by triangulation of data sources (GOODSON, 2017a). [10]

Since its beginnings in the 1920s, biographical interviewing has been applied in migration research. A pioneer work is the study of "The Polish Peasant in Europe and America" by sociologists William I. THOMAS and Florian ZNANIECKI ([1958] 1918-1920) who belonged to the Chicago School and developed life history as an innovative research method to explain migration-specific social phenomena. After losing its momentum in the 1930s, the biographical approach has since the 1970s regained relevance and has become an interdisciplinary field in migration studies (for a detailed description see APITZSCH & SIOUTI, 2007; BRECKNER & MASSARI, 2019; GOODSON 2017b; SIOUTI, 2017). Since the 1990s, biographically oriented research on migration phenomena has expanded steadily, acknowledging different migration processes (e.g., GÜLTEKIN, 2003; McDOWELL, 2005; THOMSON, 1999). The emergence of the transnational perspective in migration research and subsequent critiques on traditional epistemic and methodological approaches in the context of the nation-state ("methodological nationalism," WIMMER & GLICK SCHILLER, 2003), have boosted methodological development in biographical research (APITZSCH & SIOUTI, 2014; RUOKONEN-ENGLER & SIOUTI, 2013, 2016; TUIDER, 2011). In migration studies, various authors highlight the biographical approach as valuable for capturing unanticipated reasons for moving or staying, relationships between different factors and emotional dimensions (BLUNT, 2007; HALFACREE & BOYLE, 1993; MORSE & MUDGETT, 2018; NÍ LAOIRE, 2000). Besides, as a counterpart to being on the move, negotiations of belonging and home were addressed by means of biographical approaches, as in the case of the home-making processes of retirement migrants (KORDEL, 2015) or life course perspectives on the diverse staying processes of rural young adults (STOCKDALE, THEUNISSEN & HAARTSEN, 2018). [11]

To date, narrative interviews, as introduced by Fritz SCHÜTZE in the 1980s (1983) and aiming to reconstruct life histories by means of biographical narratives are established methods of inquiry in the social sciences. Currently, a variety of biographical tools of inquiry, ranging from full-length personal life history to the collection of oral histories or case studies (NÍ LAOIRE, 2000), are being discussed, while terms like oral histories, life stories and life histories or biographical narrative interviews are sometimes used interchangeably (JACKSON & RUSSELL, 2010). We take the life history interviewing tool as a starting point for (im)mobility biography, since this is crucial to capture the complexity of human (im)mobilities, but also requires the researcher to make him or herself familiar with people's life-worlds at different stages of the research process (JACKSON & RUSSELL, 2010). With regard to its application, there is not just one "proper" way (GOODSON & SIKES, 2017). First and foremost, the life history interview is a collaborative process between interviewee and interviewer: it brings order and meaning to the life being told and can be more than gathering empirical data, as it is a "valuable experience for the person telling the story" (ATKINSON, 2001, p.125). This is especially important with regard to the positionality of researchers in the knowledge production process (BOTTERILL, 2015; CARLING, BIVAND ERDAL & EZZATI, 2014) and has been profoundly discussed in transnational research settings (RYAN, 2015; RUOKONEN-ENGLER & SIOUTI, 2013, 2016; SHINOZAKI, 2010; TUIDER, 2011). For the development of a participatory method, life history interviews serve as valuable due to their collaborative orientation. [12]

2.3 Participatory research in the context of human (im)mobilities

Participatory research comprises methodological approaches and techniques "geared towards planning and conducting the research process with those people whose life-world and meaningful actions are under study" (BERGOLD & THOMAS, 2012, §1). Participatory methodology is seen as a "research style" (§2) and "an orientation to inquiry" (REASON & BRADBURY, 2008, p.1) that aims to cooperatively investigate and influence social reality, to involve actors from society as co-investigators, to elaborate means for individual and collective self-empowerment of partners and to enable participation in society (BERGOLD & THOMAS, 2012; VON UNGER, 2014). Participatory research practice has arisen in different scientific disciplines like education, sociology, social work, psychology, health, politics and development studies. Accordingly, a huge variety of approaches and terminology exists (for developments in the German and Anglo-American sphere, see VON UNGER, 2014). Famous approaches include participatory action research (e.g., FREIRE, 1968 in education studies), community based participatory research (e.g., ISRAEL, SCHULZ, PARKER & BECKER, 1998 in health studies) and the participatory rural appraisal (e.g., CHAMBERS, 1994 in development research). Central to the scientific debates are different conceptualizations of the way research partners participate (BERGOLD & THOMAS, 2012), e.g., "participation as means" or "participation as end" (KUMAR, 2002, p.26), and whether the focus is limited to the collaborative research process or is also on social change, as is postulated in the action research paradigm (LEWIN, 1946; REASON & BRADBURY, 2008). [13]

Key to participatory research are collaborative investigation and, an attempt to even up power imbalances between researcher and participant, but as well as to consider inequalities within the field itself, i.e., among participants. Therefore, the whole research process, from planning to implementation and data processing should be guided by the questions: who is participating, when, in what kind of processes and how (VON UNGER, 2014)? Proper ways for participants to be involved and the degree to which they participate have been discussed in different fields of research (ARNSTEIN, 1969; HART, 1992; KUMAR, 2002; PRETTY, 1994; WRIGHT, VON UNGER & BLOCK, 2010). Investigations into human (im)mobilities require a special dedication to actors' involvement and critical reflection on the positionalities and roles of the people involved. Firstly, the presence and absence of people in the field at the moment of research could result in biased sampling and may lead to misinterpretations. Therefore, it is necessary to become familiar with the life-worlds and routines of potential participants and to take into account whose perspectives are considered and which information may be lacking. Secondly, uneven power structures in (im)mobility contexts and the high vulnerability of the people concerned, especially in the case of forced migrants, call for methodological strategies to balance power relations and to foster the empowerment of research partners both during and after the research process. Hence, for methodological development, research tools must be carefully selected with consideration for participants' life-worlds and techniques should be jointly elaborated. In (im)mobilities research, participatory methodologies have been applied in migration research (TORRES & CARTE, 2013; VAUGHN, JACQUEZ, LINDQUIST-GRANTZ, PARSONS & MELINK, 2017), in refugee research (DONÁ, 2007; ELLIS, KIA-KEATING, ADEN YUSUF, LINCOLN & NUR, 2007; LINDSAY, DHILLON & ULMER, 2017), in research with children and youth (FARMER, 2017; GREEN & KLOOS, 2009; JERVES, DE HAENE, ENZLIN & ROBER, 2018), and place-based belonging (WEIDINGER, KORDEL & KIESLINGER, 2019). [14]

For methodological development in our research settings, we refer to the principles of PRA defined by CHAMBERS (1994, p.1253) as "a growing family of approaches and methods to enable local (rural and urban) people to express, enhance, share and analyze their knowledge of life and conditions, to plan and to act." Accordingly, people should be equally able to partake in research, and participants' own words, ideas and understandings should be respected; research methods should be flexible and inventive (BEAZLEY & ENNEW, 2014). Visual tools are especially valuable in the case of (im)mobilities research as they enable the participation of both literate and illiterate people equally and are useful to overcome language and cultural barriers. Besides, the visual manifestation reinforces the meaning of the issue talked about and stimulates participants' memories (CHAMBERS, 1994). In order to capture the temporal dimensions of people's life-worlds, different time-related PRA tools have been developed (for an overview see KUMAR, 2002), among them the timeline tool, which explores an aggregate of past events and their chronology. In order to jointly develop (im)mobility biographies of individuals based on biographical-narrative and participatory ideals and to grasp related meanings of place, time and social interaction, we combine the timeline tool with the life history interviewing tool (ATKINSON, 2001; GOODSON, 2017a; JACKSON & RUSSELL, 2010) and term this method "(im)mobility biography." [15]

3. The Application of (Im)mobility Biography

In this section, we discuss the application of (im)mobility biography with special emphasis on the diversity of (im)mobility trajectories and biographies. We sketch practical decisions to be made when planning and preparing its implementation within a study design, highlight the relevance of approaching participants' life-worlds to tackle the social meanings of (im)mobilities (CRESSWELL, 2010), and safeguard a participatory orientation. In order to demonstrate different opportunities for conducting (im)mobility biography, two modes of implementation in distinct migration contexts will be illustrated: in Germany, a place-based orientation was emphasized, while in Ecuador we focused on social network constellations. Finally, we discuss the processing, analysis and interpretation of textual and graphical data outputs. [16]

3.1 Getting started: Planning and preparing sound research on (im)mobilities

Given the processual and transformative nature of human (im)mobilities, their complex temporal and spatial dimensions, their social meanings and power structures, we consider the following issues to be essential prerequisites for participatory oriented qualitative research in this field: first, familiarity with the life-worlds of the people concerned, second, actors' involvement and working with co-investigators, and third, joint elaboration of data collection materials. In particular, researchers should initiate a mutual learning process prior to practical application of the method. The following explanations should not be understood as chronological but as cyclical and often parallel working steps. [17]

3.1.1 Becoming familiar with participants' life-worlds

As shown before, (im)mobility biographies are highly determined by the diversity of people's life-worlds and associated with complex spatial and temporal patterns as well as social interactions. Besides desk research, e.g., by means of local media, blogs, and social networks, becoming familiar with participants' life-worlds includes gathering information on individually important or meaningful places (meeting points, for example), avoided or unused places, and ways of moving around (such as means of transport, infrastructures). For the temporal dimension, an understanding of temporalities (e.g., historical events, seasonality, day-night time), and routines (e.g., circadian cycles) is seen to be important. Finally, actors' roles (e.g., their positions, responsibilities, rights and duties) as well as forms of organization on different scales (e.g., family, household, local authorities) should be captured. Site visits and "hanging out" (RODGERS, 2004, p.48, in the context of forced migrants), combined with observation and informal talks, to mention just a few options, might be ways to get access to the field, followed by guided interviews, participatory workshops or group discussions, depending on social hierarchies, actors' capacities and how much time is available for gathering more detailed information on certain topics of interest (BERNARD, 2006; DESAI & POTTER, 2014; KUMAR, 2002). Apart from collecting contextual information with regard to the research topic, this process provides helpful insights that enable critical reflection on the research design with regard to content (e.g., the relevance of the research from local stakeholders' perspective, reference points for time or place), feasibility (the methodology selected, time and place of realization), cultural sensitivity and ethical issues. The latter includes voluntary participation and informed consent, confidentiality, privacy and data protection as well as avoiding exposure, embarrassment and harm to participants. This is especially important and challenging in (im)mobility research (examples of forced migration see CLARK-KAZAK, 2017; MacKENZIE, McDOWELL & PITTAWAY, 2007). In parallel, the researcher gets to know local organizational structures and actors' positions in the field, necessary for the establishment of contacts and actors' involvement. [18]

3.1.2 Actors' involvement: Establishing contacts in the field and working with co-investigators

A core issue in participatory research methodologies is actors' involvement and the question of who will participate in the research process, when, how and which roles participants will assume (BERGOLD & THOMAS, 2012; KUMAR, 2002; VON UNGER, 2014). Not limited to but especially relevant in research on (im)mobilities, the presence and absence of actors at the time of research must be considered and reflected on critically with regard to the question of whose voices are heard and whose perspectives may remain hidden. We recommend starting with actors' involvement right at the beginning and being flexible during the whole research project, as participation is processual and a question of confidence. During different phases of research, manifold actors get involved according to their skills, positions, and the organizational and/or content-related tasks they take over. Therefore, at the beginning, it is necessary to identify important actors in the field (e.g., key informants, gatekeepers, local stakeholders and stakeholder groups, interview participants) and to establish contacts. Besides, the researchers' self-reflection on their own position, and being clear about this with potential participants helps to avoid false hopes, e.g., regarding personal benefits or local development issues. Apart from this, establishing networks may help with logistics (e.g., facilities, contacts, official announcements) and the visibility of one's research in local contexts, and can therefore enhance willingness to participate. At the same time, researchers must be aware of temporarily absent actors, who may provide important perspectives on the research issue. Their involvement should be considered, if possible. [19]

We recommend reflecting on how co-investigators (BERGOLD & THOMAS, 2012; VON UNGER, 2014) are to be involved in (im)mobility biography as possible members of the research team (e.g., as local field workers or interpreters). Co-investigators3), familiar with the language, local conditions and organizational structures, ways of living and cultural peculiarities of target groups, could act as mediators between researchers and actors of interest, or may help detect absent actors or those hard to reach. Depending on their skills and the degree of involvement in all different research phases they may fulfill functions like facilitating contacts, organizing meetings, testing data collection tools, becoming interviewers or supporting data processing and analysis. Working with research partners who do not have an academic background in the social sciences requires training measures (e.g., knowledge transfer workshops, including role-plays) and advice in the daily interaction of the research team, dealing with such things as the principles of participatory research, communication skills, ethical concerns, data protection and data management. It is important to consider the processuality and re-negotiation of the allocation of roles within the research team and in interaction with other actors in the field, making necessary conscious self-reflection and dialogue (MARSHALL & REASON, 2007). With regard to the accomplishment of (im)mobility biography, roles within the research team and the roles of participants have to be clear for everyone. In order to shift power from the interviewer to the participants, there should be open discussion in which participants are able to direct the interview themselves (e.g., in making decisions about when to talk, write or draw, or whether they want to write themselves). [20]

3.1.3 Joint elaboration of data collection materials with co-investigators

The materials for collecting data on (im)mobility biographies comprise an interview guide with instructions for the application of the timeline tool (e.g., use of materials, working steps, the roles of different interviewers), and writing and drawing tools for the graphic elaboration, accompanied by protocols for the documentation of notes. All materials should be closely worked out together with co-investigators. In doing so, the guiding questions can be discussed with regard to comprehension, simple everyday language, the use of terms and differing concepts in intercultural contexts (e.g., migration vs. mobility) and necessary additional information can be identified (e.g., the characteristics of household members). Furthermore, certain reference points and definitions, such as the starting point of the timeline, or what counts as a household, need to be determined, orienting participants and interviewers in the process. For the timeline tool, the materials have to be prepared, including tape, pens, paper sheets with timelines and different colored paper cards (to represent individuals, individually important life events, living places and meaningful places). The materials should be kept as simple as possible and supplied in generous quantities. After testing the operation of the tool by means of role plays, the working steps and their chronological order are defined and principle roles are assigned to at least three interviewers (e.g., asking questions, taking notes, observing interviewer-participant relations, doing requests and check backs, helping with materials). The joint elaboration of data collection tools is essential to ensure that everyone is talking about the "same things," to enable critical reflection on individual presuppositions or expectations and to reveal questions or insecurities regarding the procedure or organizational aspects of the interview. From an organizational point of view, voice recorders and cameras are necessary for the application of (im)mobility biography. Recording the interview is especially important as (im)mobility biography is very demanding of conversational and organizational skills due to the high flexibility of the interview situation and the joint elaboration of the timeline. Taking pictures of the resulting timelines is necessary because at the end both textual and visual data output have to be analyzed together. [21]

3.1.4 Involvement of participants: Sampling, inter-personal relations and forms of gratitude

Participant involvement strongly builds upon the experiences gathered during the field visits and the approximation to life-worlds with regard to the meanings of places, ways of moving around, temporalities, routines, roles and forms of local organization, and finally valuable contacts with other actors. To avoid bias of place (KUMAR, 2002) and due to the aforementioned recommendations of local actors which may cause an (un)intentional exclusion of certain participants (BERGOLD & THOMAS, 2012), we selected various points of access to participants in rural districts and drew on cold acquisition at different places, using gatekeepers and snowball sampling. In order to prevent timing bias (KUMAR, 2002), we considered different temporalities, like daily or weekly routines (e.g., work in the fields, commuting for work or educational purposes) as well as seasonal peculiarities (e.g., workloads in agricultural production, climatic conditions). Recruitment was therefore undertaken at different times of day, week and year. Since we were interested in obtaining views from a diverse range of people, we conducted nonprobability sampling, i.e., purposive sampling (BERNARD, 2006) to access in-depth life stories. [22]

Interview appointments were made by means of a personal face-to-face approach during field trips or by telephone, and participants' preferences regarding time and place were also considered. In order to establish a confident inter-personal relationship between the researcher, team and participant, preliminary talks and explanations are helpful. Such talks could be achieved as part of the process during the different phases of the research project e.g., as informal and accidental meetings and during the researchers' visibility in public places, or by means of separate appointments, such as icebreaker meetings (WEIDINGER et al., 2019). During these talks, the researchers present themselves, talk about the aim of the study, their institutional background, the research issue, data protection regulations, the use of voice recorders and cameras as well as the interview situation and procedure. Additionally, participants' questions and doubts, and the best ways for future application of (im)mobility biography (e.g., locations, timing, data collection tools) are discussed. It is not uncommon for these participants to become multipliers in facilitating access to further interview partners. [23]

Especially in participant-oriented research and alongside actors' engagement, discussion about the appropriate way to say thank you to participants is crucial. In our view, every participant should be reimbursed for their expenditure of time, including members of the extended working team such as co-investigators, the same way as interview participants (e.g., farmers or homemakers who sacrifice their usual duties in their everyday business). While it may be common to remunerate co-investigators, in the case of interview or workshop participants, financial payments should be questioned critically. In both study settings, therefore, we decided to bring along presents as symbolic compensation, which were appropriate to the local conditions, provided added value for participants and were the same for everyone. In rural Ecuador we selected foodstuffs that people would normally have to buy at local markets, while power banks for mobile devices were given to participants from a refugee background in Bavaria, Germany. [24]

3.2 Implementation: Information and data collection

As mentioned before, we conducted (im)mobility biography in two distinct migration contexts, whilst two different modes were applied. After preliminary talks mentioned above, the research team initially presented itself and gave a short introduction regarding the research issues and aims, the institutional background, data protection and the procession of the method. [25]

The first mode of implementation of (im)mobility biography is considered as place-oriented. Taking an individual's arrival at a certain place as a starting point, this approach is especially valuable for capturing a temporally limited period of a participant's life up to the present. Respondents' places of residence served as a temporal structuration of (life) time, evoked emotions and feelings as well as practices associated with these places, and thus unraveled the ascribed meanings of place, time and social interaction. Thus, the place-oriented mode of implementation was more focused on, but not limited to, the individual life trajectory. [26]

This mode was applied in a case study conducted with recognized refugees, who lived in two rural districts, Regen and Neustadt a.d. Aisch-Bad Windsheim in Bavaria, Southern Germany, between September 2018 and March 20194). In the course of a narrative interview up to 1.5-hours long, participants were invited to talk about their past experiences of places by means of (im)mobility biography. [27]

The (im)mobility biography began with an opportunity to empathize with the participant about their time of arrival in Germany. Accordingly, the initial stimulus for narration aimed to place the participants in that specific period of time, e.g., by asking them about how they recognized that they were in Germany, or any specific memories, possibly associated with feelings and emotions. The core of this mode of implementation, however, encompassed narratives about places participants lived in. For each place, participants were invited to talk about the time spent at those places, including negative and positive experiences. Simultaneously or afterwards, the name of the place, the type of accommodation and the period of time spent there were fixed on small cards and arranged chronologically on a prepared blank timeline (see Photo 1). In order to capture both staying and moving, onward mobilities were stressed. The reasons and circumstances for moving on, either self-determined or externally driven, are considered crucial for the evaluation of agency over one's own (im)mobility. After completion, a second stimulus was provided in order to capture individually important life events during this time. In particular, participants were asked to talk about events associated with legal issues (visas, recognition as a refugee, permission to work) as well as family-related occurrences. The latter were addressed as especially important since intergenerational aspects can enrich the evaluation of the (life) time period addressed. Finally, similar to the first step, events mentioned were fixed on small, colored cards and were arranged on the paper timeline sheets by the participants. A third stimulus then invited the participant to reflect on the drawn places and events in order to differentiate between the meanings of places and times in light of their overall desires. In concrete terms, it was asked whether the places they had lived in, and the events that had taken place, e.g., time spent in Germany, had been expected to be like this beforehand. If foreseen in the course of a wider project, the place-oriented implementation of (im)mobility mapping is able to lead to a subsequent module that deals with the present, by inviting the participant to talk about their arrival in the place where they currently live.

Photo 1: (Im)mobility biography of a Syrian participant in his 30s residing in the district of Regen, Germany. Please click here for an enlarged version of Photo 1. [28]

The second mode of implementation of (im)mobility biography focuses more on complex family and inter-generational constellations by addressing (im)mobile persons in a certain group (e.g., household, family). Having identified members of the group as well as family constellations, either during a previous talk or right at the beginning of the interview, this approach takes departures, arrivals and periods of stay of the different members as a starting point and enables researchers to capture constellations of absence and presence in a limited period of the participant's lifetime. In doing so, overlap between different temporalities and possible coincidences can be addressed. People's (im)mobilities serve as structuration of a (life) time whereby related causes and effects are discussed, revealing meanings of place, time and social interaction. [29]

This mode was applied in a case study conducted with stayers, re-migrants and newcomers in the rural district [cantón] of Macará in Southern Ecuador, between October 2016 and October 20175). In the course of a narrative interview of up to 1.5-hours, participants were invited to talk about their past and recent experiences with (im)mobilities of different household members by means of (im)mobility biography. [30]

If not undertaken during the preliminary talks, the initial phase of (im)mobility biography aimed at the identification and fixation of certain reference points. Therefore, narrative stimuli were provided to grasp an individual's lifetime at the recent place of residence, and their recent household constellation (including members and roles as well as former household members). In order to manage large numbers of people, names and certain personal data (e.g., relation to the participant, age, gender, place of residence of former members) were recorded in prepared excel lists, and notes were taken in the margins of the timeline paper sheets (see Photo 2). In the second phase, stimuli were offered for capturing narrations about (im)mobile household members, whereby the participants were first invited to talk about people who had left the household, the decision-making process, reasons for and feedback effects of migration and the role of social relations. Simultaneously or afterwards, small cards were drawn up for each person with the name, relation to the participant and destination; they were arranged on the paper timeline sheets and dates of outmigration and return were marked. As (im)mobility interactions and arrangements play an important role in decision-making, stayers' perspectives are necessary to fully understand group dynamics and household constellations. Thus, secondly, participants were asked to talk about people who had never left the household, and again decision-making, reasons for staying and feedback effects as well as the role of social relations were addressed. In the third phase we focused on externally driven events or circumstances by encouraging participants to talk about individually important or critical life events concerning livelihoods and the well-being of family or household members, which were written on distinct colored cards and arranged chronologically on the timeline. In the last phase, stimuli for reflection were provided, with regard to possible interdependencies between the (im)mobilities of distinct household members and between the (im)mobilities of household members and the life events stated above.

Photo 2: (Im)mobility biography of an Ecuadorian family reported by the head of household (born in 1939) residing in the district

of Macará, Ecuador. Please click here for an enlarged version of Photo 1. [31]

For data documentation purposes and subsequent analysis, in each implementation mode, a picture of the (im)mobility biography was taken and the original product was handed over to the participant at the end6). After the interviews and jointly with the co-investigators, minutes were completed for each interview, encompassing information about the process and any difficulties that occurred as well as the main results. [32]

3.3 Data processing, analysis and interpretation

As is widely acknowledged in visual studies, "a picture or a photograph has no meaning in and of itself, it is the interpretation and explanation that is important" (MORROW, 2001, p.266). Thus, according to Virginia MORROW, the timelines produced must not be considered an end product, but have to be analyzed and made sense of, framing them verbally or visually (BAGNOLI, 2009). A peculiarity of an (im)mobility biography is that processes of data collection and analysis overlap, not least due to its participatory character. Already during the interview, the visualization of the biography allows for the shared analysis and interpretation of data by both participant and researcher. Since participants' perspectives are acknowledged, more valid data can be generated. [33]

Depending on the research aim, an (im)mobility biography can be processed and analyzed differently, either form- or content- and either holistic- or category-oriented (LIEBLICH, TUVAL-MASHIACH & ZILBER, 1998). Accordingly, four different kinds of analyses can be distinguished following the typology of narrative analysis suggested by Catherine KOHLER RIESSMAN (2005, 2008): thematic analysis, structural analysis, dialogic/performance analysis and visual analysis. While the first would emphasize meanings, i.e., what is told and drawn within an (im)mobility biography, with the ideal being to find common thematic elements between participants, the second, in contrast, would address the process of telling, i.e., how things are said and narrated, including language use, dialect, pauses or other verbal idiosyncrasies (ATKINSON, 2001). Thus, it fits well with in-depth analyses of only a few interviews. Dialogic or performance analysis, in turn, investigates "timelining" (SHERIDAN, CHAMBERLAIN & DUPUIS, 2011) as a performative act and would therefore focus on co-constructiveness between participants and the research team in order to reveal power structures during the conversation. This analysis is especially useful for interviews with more than one person, and focus groups in particular. A visual analysis of the (im)mobility biography, finally, is interested in the production process of the timeline during the narration in order to identify what was and what was not visualized on it for what reason (and how). [34]

For our implementation modes we drew on a combination of thematic and visual analysis. Being aware of the fact that transcription inevitably involves interpretation (ATKINSON, 2001), interviews were initially transcribed verbatim with an emphasis on connections between the spoken word and the graphic elicitation of the timelines in particular. Images of the timelines, in turn, were edited graphically in order to catalog specific elements. To validate results and dissolve data discrepancies, it was necessary in some cases to include a "loop," i.e., an interactive dialogue that enabled participants to comment on the transcript and address open questions (ATKINSON, 2001; GODSON & SIKES, 2017). Finally, both the transcript and the timelines were coded openly using the same coding system (see the elaboration of a coding system in the course of grounded theory methodology, following CORBIN & STRAUSS, 1990), which enabled us to link the text to "visual-based quotations and to interrogate data on multiple levels" (BAGNOLI, 2009, pp.567-568). [35]

For data analysis and interpretation we followed the conceptual ideas of BAILEY (2009) and COULTER, VAN HAM and FINLAY (2016), who stated that life-course perspectives on (im)mobility are implicitly relational through time and space (ibid. p.358). With regard to the former, it was important for us to understand "how people move through time, use time or relate to time" (NEALE & FLOWERDEW, 2003, p.192) during the "timelining" process. This is important not least against the backdrop of different concepts of time (KUMAR, 2002) as well as of experiences shared inter-generationally. Accordingly, our data treatment focused on practices of "doing" (im)mobility in order to identify how individuals reveal and produce the ties linking them together and connecting them to broader structures (COULTER et al., 2016, p.354). On the micro level, thus, the linked lives of individuals, i.e., social ties within and beyond the household, were of interest. Thereby, differences with regard to gender were taken into consideration. On the meso level, secondly, the effects of the neighborhood or locality, i.e., the actions of different stakeholders in local politics or within the labor and housing market, e.g., were addressed, while differences between places provided an important point in the analysis of (im)mobility. On the macro level, thirdly, long-term changes in policies and cultural norms were taken into account, allowing for pre-post-comparisons, e.g., due to socio-ecological changes. Overarching agency respectively unequal power relations were seen as vital to understand individual decision-making about mobility and immobility (HALFACREE & BOYLE, 1993). [36]

In terms of the storage and publication of data, it was important to take into account issues of shared authority between the research team and participants, as well as the protection of sensitive data on (im)mobilities. The latter not only encompasses personal data that relate directly to individuals or groups, which are mostly protected by means of data protection acts in many countries, but may also include information about processes and modes of operation of the (im)mobility regimes. The disclosure and publication of data on human trafficking, onward mobilities that counteract state regulations, regular places of residence and temporary absence can sustain or even aggravate conditions of vulnerability of the people concerned. This may have negative effects on their ability to renew residence permits, uphold land titles or receive social welfare benefits, and may lead to the imposition of new penalties by state and non-state actors. [37]

4. Discussion of Strengths and Possible Challenges

This article has suggested (im)mobility biography as a method that tackles the challenge to recapitulate biographies in mobile settings and simultaneously addresses biographies in relation to spatially and temporally distant places and other people. The time-related visual and participatory method presented here aims to understand individuals' and groups' life-worlds in a relational sense. Drawing on experiences gained in two different modes of implementation, we could identify the following (dis)advantages for both biographical research in light of complex (im)mobility trajectories and the aim to empower the participants according to the principles of participatory research. [38]

Firstly, (im)mobility biography is a method which is able to consistently apply a relational approach in the social sciences. Identifying meanings ascribed to either places or people at a certain time in someone's biography enhances our understanding of life-worlds in the present. As highlighted for life history interviews, we contend that the suggested biographical method encourages "a dialogical relationship between past and present, where past events are viewed through the lens of the present and where present-day concerns shape what is remembered and forgotten from the past" (JACKSON & RUSSELL, 2010, p.187). Thus, (im)mobility biography serves as a means to understand individuals' current practices and decisions about (im)mobility. Simultaneously, the method is able to strengthen the contextualization of life events and experiences. Secondly, implementing (im)mobility biography stimulates interaction and discussion and especially helps to structure individually important events chronologically as life histories "seldom conform to a strict chronology and are characterized by recaps, leaps forward and references across time and space" (p.186). Since participants could sometimes hardly remember specific events, both in terms of the time when they happened and the contexts and constellations in which they were embedded, (im)mobility biography helps us acquire valid qualitative data from the past. For the participant, graphic visualization strongly supports the ability to remember and structure life events, while the researcher can use it as a stimulus to foster and deepen the narration process. However, the principles of subjective storytelling and internal consistency must be kept in mind (ATKINSON, 2001). By reconstructing decision-making processes for moving or staying, the method presented here approximates people's agency. Whether and to what extent decisions are made autonomously can be illustrated, and, as a consequence, can make the participants reflect upon their agency, e.g., within hierarchically structured family constellations, but also in wider structures in (im)mobility contexts. Like other participant-oriented approaches (e.g., mobility mapping, WEIDINGER et al., 2019), (im)mobility biography is addressed as a means of data acquisition, which gives participants autonomy over the ways they choose to express themselves. Moreover, it is less dependent on language and literacy. In accordance with other activating approaches, participation in the (im)mobility biography "was seen as a welcome change and alternative to everyday life as well as an enjoyable activity" (p.18). Since the principles of participatory research particularly encompass the empowerment of individuals or groups, (im)mobility biography can help to encourage a reflection on current life-worlds and the alignment of oneself in terms of past experiences. [39]

Challenges in terms of the application of this time-related visual method firstly arise from the resource intensity of (im)mobility biography. Since up to 1.5 hours have to be scheduled for its implementation and three interviewers are necessary to warrant a smooth process, resources have to be provided. During the implementation, participants could sometimes hardly remember certain aspects, or faced gaps which they might not be able to fill. It could therefore be challenging for the interviewer who might lack relational references for the life history, which could hamper contextual embeddedness and the interpretation of the (im)mobility biography. Moreover, interviewers should anticipate that some parts of the story may only be reconstructed jointly with those who shared the same experience, but who may be absent during the interview. In case the participant strives to share a more complete life history, strategies that meet this obstacle, like consulting other people via phone or face to face contact or using social media posts should be encouraged. Most challenging, however, is the proper handling of the interpersonal relations developed between participants and the researcher team, since private, personal and sensitive information is shared during the interview. In case participants are not willing to talk about negative experiences (because they feel it is not socially desirable, for instance), the researcher has to build confidence and encourage them to continue. In case strong emotions are elicited (maybe concerning failed migration trajectories or hard living conditions at different locations), she or he has to balance the situation and find the right moment to make a smooth transition to another topic to avoid causing harm and trauma. Thus, the researchers "have to be guided by an ethic of care, a strong sense of discretion and a recognition that they are probably not qualified to deal with deep-seated psychological issues" (JACKSON & RUSSELL, 2010, p.179). Accordingly, interviewers should have to hand contact details for health and psycho-social services. [40]

To sum up, for migration studies, we contend that (im)mobility biography captures individuals' complex temporal and spatial patterns of moving on and staying put, as well as social meanings, underlying power structures and group interactions. For qualitative research, the suggested method reminds us that due to a participatory orientation expressed via the shared analysis of (im)mobility biography, data collection and analysis may take place simultaneously, which should be recognized as a strength, rather than a deviation from structured research designs. [41]

1) We draw on the concept of KRAUS (following SCHÜTZ & LUCKMANN, 1973) who considered life-worlds as "a person's subjective construction of reality, which he or she forms under the condition of his or her life circumstances" (KRAUS, 2013, p.153). <back>

2) Translations from German texts are ours. <back>

3) Whilst, in participatory research, all participants are subsumed under the term co-investigators (BERGOLD & THOMAS, 2012; VON UNGER, 2014), here, in order to enhance readability, we distinguish between co-investigators as part of the research team and participants. <back>

4) The implementation was embedded in a larger, multi-perspective project on the future prospects of recognized refugees in rural areas of Germany. The project was supported by funds of the Federal Ministry of Food and Agriculture (BMEL), based on a decision of the Parliament of the Federal Republic of Germany via the Federal Office for Agriculture and Food (BLE) under the rural development program. The particular group of recognized refugees was chosen since it is assumed that they have various experiences with negotiation of forced and voluntary residential (im)mobilities during the asylum procedure and afterwards (KORDEL & WEIDINGER, 2019). The study was based on a modular design in order to capture the past, present and future life-worlds of individuals. (Im)mobility biography paved the way for subsequent mobility mapping (WEIDINGER et al., 2019), and was necessary to meet the need for relational reflection on individuals' life-worlds. <back>

5) The implementation was embedded in a larger, multi-perspective project on (im)mobilities and related socio-ecological transformations in rural Ecuador. Households were chosen as one actor group since it is assumed that the distinct roles and duties of household members to ensure livelihoods may foster different (im)mobility desires, necessities and abilities which are permanently negotiated and may result in (im)mobility interactions or arrangements. The study was based on a modular design in order to capture the past, present and future life-worlds of individuals within different household constellations. (Im)mobility biography paved the way for a more detailed analysis by means of cause-effect diagrams (KUMAR, 2002) on certain household members' (im)mobilities. Similar to the above mentioned case study, (im)mobility patterns of recent members in everyday life were detected by means of mobility mapping in order to understand roles, duties and livelihood strategies. <back>

6) Depending on the research interest, photos of the timeline can also be taken during the interview process in case the production process itself is of specific interest. <back>

Adey, Peter (2006). If mobility is everything then it is nothing: Towards a relational politics of (im)mobilities. Mobilities, 1(1), 75-94.

Apitzsch, Ursula & Siouti, Irini (2007). Biographical analysis as an interdisciplinary research perspective in the field of migration studies, https://www.york.ac.uk/res/researchintegration/Integrative_Research_Methods/Apitzsch%20Biographical%20Analysis%20April%202007.pdf [Accessed: July 3, 2019].

Apitzsch, Ursula & Siouti, Irini (2014). Transnational biographies. Zeitschrift für Qualitative Forschung, 15(1-2), 11-23, https://nbn-resolving.org/urn:nbn:de:0168-ssoar-461021 [Accessed: July 3, 2019].

Alheit, Peter (1988). Alltagszeit und Lebenszeit. In Rainer Zoll (Ed.), Zerstörung und Wiederaneignung von Zeit (pp.371-386). Frankfurt/M.: Suhrkamp.

Arnstein, Sherry R. (1969). A ladder of citizen participation. Journal of the American Planning Association, 35(4), 216-224.

Atkinson, Robert (2001). The life history interview. In Jaber F. Gubrium & James A. Holstein (Eds.), Handbook of interview research. Context and method (pp.121-140). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Bagnoli, Anna (2009). Beyond the standard interview: The use of graphic elicitation and arts-based methods. Qualitative Research, 9(5), 547-570.

Bailey, Adrian J. (2009). Population geography: Lifecourse matters. Progress in Human Geography, 33(3), 407-418.

Bailey, Adrian J.; Blake, Megan K. & Cooke, Thomas J. (2004) Migration, care, and the linked lives of dual-earner households. Environment and Planning A, 36, 1617-1632.

Bauman, Zymunt (1998). Globalization: The human consequences. Cambridge: Polity.

Beazley, Harriot & Ennew, Judith (2014). Participatory methods and approaches: Tackling the two tyrannies. In Vandana Desai & Robert B. Potter (Eds.), Doing development research (pp.189-199). London: Sage.

Bell, Michael M. & Osti, Giorgio (2010). Mobilities and ruralities: An introduction. Sociologia Ruralis, 50(3), 199-204.

Bergold, Jarg & Thomas, Stefan (2012). Participatory research methods: A methodological approach in motion. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung / Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 13(1), Art. 30, http://dx.doi.org/10.17169/fqs-13.1.1801 [Accessed: July 31, 2019].

Bernard, H. Russell (2006). Research methods in anthropology. Qualitative and quantitative approaches. Lanham, MD: Altamira.

Bertaux, Daniel (Ed.) (1981). Biography and society. The life history approach in the social sciences. Beverly Hills, CA: Sage.

Bertaux, Daniel & Thompson, Paul (Eds.) (1997). Pathways to social class. A qualitative approach to social mobility. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

Blunt, Alison (2007). Cultural geographies of migration: Mobility, transnationality and diaspora. Progress in Human Geography, 31(5), 684-694.

Botterill, Katherine (2015). "We don't see things as they are, we see things as we are": Questioning the "outsider" in polish migration research. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung / Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 16(2), Art. 4, http://dx.doi.org/10.17169/fqs-16.2.2331 [Accessed: July 31, 2019].

Bourdieu, Pierre (1983). Ökonomisches Kapital, kulturelles Kapital, soziales Kapital. In Reinhard Krekel (Ed.), Soziale Ungleichheiten (pp.183-198). Göttingen: Otto Schwarz & Co.

Brandtstädter, Jochen & Greve, Werner (2005). Entwicklung und Handeln: Aktive Selbstentwicklung und Entwicklung des Handelns. In Wolfgang Schneider & Friedrich Wilkening (Eds.), Theorien, Modelle und Methoden der Entwicklungspsychologie (pp.409-459). Göttingen: Hogrefe.

Breckner, Roswitha & Massari, Monica (2019). Biography and society in transnational Europe and beyond. An introduction. Rassegna Italiana di Sociologia, 1, 3-18.

Büscher, Monika; Urry, John & Witchger, Katian (Eds.) (2011). Mobile methods. Abingdon: Routledge.

Carling, Jørgen (2002). Migration in the age of involuntary immobility: Theoretical reflections and Cape Verdean experiences. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, 28(1), 5-42.

Carling, Jørgen; Bivand Erdal, Marta & Ezzati, Rojan (2014). Beyond the insider-outsider divide in migration research. Migration Studies, 2(1), 36-54.

Chambers, Robert (1994). Participatory rural appraisal (PRA): Analysis of experience. World Development, 22(9), 1253-1268.

Clark-Kazak, Christina (2017). Ethical considerations: Research with people in situations of forced migration. Refuge: Canada's Journal on Refugees, 33(2), 11-17, https://doi.org/10.7202/1043059ar [Accessed: January 1, 2020].

Coleman, James Samuel (1988). Social capital in the creation of human capital. The American Journal of Sociology, 94(Suppl.), 95-120.

Corbin, Juliet M. & Strauss, Anselm L. (1990). Grounded theory research: Procedures, canons and evaluative criteria. Zeitschrift für Soziologie, 19(6), 418-427.

Coulter, Rory & van Ham, Maarten (2013). Following people through time: An analysis of individual residential mobility biographies. Housing Studies, 28(7), 1037-1055.

Coulter, Rory; van Ham, Maarten & Findlay, Allan M. (2016). Re-thinking residential mobility: Linking lives through time and space. Progress in Human Geography, 40(3), 352-374.

Cresswell, Tim (2010). Towards a politics of mobility. Environment and Planning D: Society and Space, 28, 17-31.

Cresswell, Tim (2011). "Mobilities I: Catching up". Progress in Human Geography, 35(4), 550-558.

D'Andrea, Anthony; Ciolfi, Luigina & Gray, Breda (2011). Methodological challenges and innovations in mobilities research. Mobilities, 6(2), 149-160.

Desai, Vandana & Potter, Robert B. (Eds.) (2014). Doing development research. London: Sage.

Doná, Giorgia (2007). The microphysics of participation in refugee research. Journal of Refugee Studies, 20(2), 210-229.

Dunlevy, James A. (1991). On the settlement patterns of recent Caribbean and Latin immigrants to the United States. Growth Change, 22(1), 54-67.

Elder, Glen H.; Kirkpatrick Johnson, Monica & Crosnoe, Robert (2003). The emergence and development of life course theory. In Jeylan T. Mortimer & Michael J. Shanahan (Eds.), Handbook of the life course (pp.3-19). New York, NY: Springer.

Ellis, Heidi B.; Kia-Keating, Maryam; Aden Yusuf, Siraad; Lincoln, Alisa & Nur, Abdiraham (2007). Ethical research in refugee communities and the use of community participatory methods. Transcultural Psychiatry, 44(3), 459-481.

Farmer, Diane (2017). Children and youth's mobile journeys: Making sense and connections within global contexts. In Caitriona Ní Laoire, Allen White & Tracey Skelton (Eds.), Movement, mobilities, and journeys (pp.245-269). Singapore: Springer.

Fay, Michaela (2007). Mobile subjects, mobile methods: Doing virtual ethnography in a feminist online network. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung / Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 8(3), Art. 14, http://dx.doi.org/10.17169/fqs-8.3.278 [Accessed: July 31, 2019].

Filipp, Sigrun-Heide & Aymanns, Peter (Eds.) (2010). Kritische Lebensereignisse und Lebenskrisen. Vom Umgang mit den Schattenseiten des Lebens. Stuttgart: Kohlhammer.

Fischer, Wolfram (1982). Time and chronic illness. A study on social constitution of temporality. Berkeley, CA: Publisher not identified.

Fischer-Rosenthal, Wolfram (1989). Life story beyond illusion and events past. Enquête, 5, http://enquete.revues.org/110 [Accessed: January 1, 2020].

Freire, Paulo (1968). Pedagogy of the oppressed. New York, NY: The Seabury Press.

Freund, Alexandra M. & Baltes, Paul B. (2005). Entwicklungsaufgaben als Organisationsstrukturen von Entwicklung und Entwicklungsoptimierung. In Sigrun-Heide Filipp & Ursula M. Staudinger (Eds.), Entwicklungspsychologie des mittleren und höheren Erwachsenenalters (pp.35-78). Göttingen: Hogrefe.

Fussell, Elizabeth & Massey, Douglas (2004). The limits to cumulative causation: International migration from Mexican urban areas. Demography, 41(1), 151-171.

Garip, Filiz (2008). Social capital and migration: How do similar resources lead to divergent outcomes? Demography, 45(3), 591-617.

Geiger, Martin & Steinbrink, Malte (2012). Migration und Entwicklung: Merging Fields in Geography. IMIS-Beiträge, 42, 7-36, https://repositorium.ub.uni-osnabrueck.de/bitstream/urn:nbn:de:gbv:700-2013091811577/1/imis42.pdf [Accessed: January 29, 2020].

Glick Schiller, Nina (1997). From immigrant to transmigrant: Theorizing transnational migration. In Ludger Pries (Ed.), Transnationale Migration (pp.121-140). Baden-Baden: Nomos.

Goodson, Ivor (2017a). Introduction. Life histories and narratives. In Ivor Goodson, Ari Antikainen, Pat Sikes & Molly Andrews (Eds.), The Routledge international handbook on narrative and life history (pp.3-10). New York, NY: Routledge.

Goodson, Ivor (2017b). The story of life history. In Ivor Goodson, Ari Antikainen, Pat Sikes & Molly Andrews (Eds.), The Routledge international handbook on narrative and life history (pp.23-33). New York, NY: Routledge.

Goodson, Ivor & Sikes, Pat (2017). Techniques for doing life history. In Ivor Goodson, Ari Antikainen, Pat Sikes & Molly Andrews (Eds.), The Routledge international handbook on narrative and life history (pp.72-88). New York, NY: Routledge.

Green, Eric & Kloos, Bret (2009). Facilitating youth participation in a context of forced migration: A photovoice project in Northern Uganda. Journal of Refugee Studies, 22(4), 460-482.

Gültekin, Nevâl (2003). Bildung, Autonomie, Tradition und Migration. Doppelperspektivität biographischer Prozesse junger Frauen aus der Türkei. Opladen: Leske + Budrich.

Haartsen, Tialda & Stockdale, Aileen (2018). S/elective belonging: How rural newcomer families with children become stayers. Population Space and Place, 24(4), 1-9. https://doi.org/10.1002/psp.2137 [Accessed: July 31, 2019].

Halfacree, Keith H. & Boyle, Paul J. (1993). The challenge facing migration research: The case for a biographical approach. Progress in Human Geography, 17(3), 333-348.

Hannam, Kevin; Sheller, Mimi & Urry, John (2006). Editorial: Mobilities, immobilities and moorings. Mobilities, 1(1), 1-22.

Hart, Roger A. (1992). Children's participation from tokenism to citizenship. Innocenti Essays, 4, https://www.unicef-irc.org/publications/pdf/childrens_participation.pdf [Accessed: January 1, 2020].

Hinske, Norbert (1986). Lebenserfahrung und Philosophie. Stuttgart: Frommann-Holzboog.

Hochschild, Arlie Russell (2000). Global care chains and emotional surplus value. In Will Hutton & Anthony Giddens (Eds.), On the edge: Living with global capitalism (pp.131-146). London: Jonathan Cape.

Holstein, James A. & Gubrium, Jaber F. (Eds.) (2000). Constructing the life course. New York, NY: General Hall.

Holz-Rau, Christian & Scheiner, Joachim (Eds.) (2015). Räumliche Mobilität und Lebenslauf. Studien zu Mobilitätsbiografien und Mobilitätssozialisation. Dortmund: Springer VS.

Israel, Barbara A.; Schulz, Amy J.; Parker, Edith A. & Becker, Adam B. (1998). Review of community-based research: Assessing partnership approaches to improve public health. Annual Review of Public Health, 19, 173-202.

Jackson, Peter & Russell, Polly (2010). Life history interviewing. In Dydia DeLyser, Steve Herbert, Stuart Aitken, Mike Crang & Linda McDowell (Eds.), The Sage handbook of qualitative geography (pp.172-192). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Jerves, Elena; De Haene, Lucia; Enzlin, Paul & Rober, Peter (2018). Adolescent's lived experiences of close relationships in the context of transnational families: A qualitative study from Ecuador. Journal of Adolescent Research, 33(3), 363-390.

Kanaiaupuni, Shawn M. (2000). Reframing the migration question: An analysis of men, women, and gender in Mexico. Social Forces, 78, 1311-1347.

Kley, Stefanie A. & Mulder, Clara H. (2010). Considering, planning and realizing migration in early adulthood. The influence of life-course events and perceived opportunities on leaving the city in Germany. Journal of Housing and the Built Environment, 25, 73-94.

Köttig, Michaela; Chaitin, Julia; Linstroth, John P. & Rosenthal, Gabriele (Eds.) (2009). Biography and ethnicity. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung / Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 10(3), http://www.qualitative-research.net/index.php/fqs/issue/view/32 [Accessed: January 1, 2020].

Kohler Riessman, Catherine (2005). Narrative analysis. In Nancy Kelly, Christine Horrocks, Kate Milnes, Brian Roberts & David Robinson (Eds.), Narrative, memory & everyday life (pp.1-7). Huddersfield: University of Huddersfield.

Kohler Riessman, Catherine (2008). Narrative methods for the human sciences. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Kordel, Stefan (2015). Striving for the "good life"—Home-making among senior citizens on the move. An analysis of German (pre)retirees in Spain and Germany in a continuum of tourism and migration. Dissertation, Human Geography, University of Erlangen-Nuremberg, Germany.

Kordel, Stefan & Weidinger, Tobias (2019). Onward (im)mobilities: Conceptual reflections and empirical findings from lifestyle migration research and refugee studies. Die Erde, 150(1), 1-16, https://doi.org/10.12854/erde-2019-408 [Accessed: January 27, 2020].

Kraus, Björn (2013). Erkennen und Entscheiden. Grundlagen und Konsequenzen eines erkenntnistheoretischen Konstruktivismus für die Soziale Arbeit. Weinheim: Juventa.

Kumar, Somesh (2002). Methods for community participation. A complete guide for practitioners. London: ITDG Publishing.

Lewin, Kurt (1946). Action research and minority problems. In Kurt Lewin & Gertrud Weiss Lewin (Eds.), Resolving social conflicts (pp.201-216). New York, NY: Harper & Brothers.

Lieblich, Amia; Tuval-Mashiach, Rivka & Zilber, Tamar (1998). Narrative research: Reading, analysis, and interpretation. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Lindsay, Vecchio; Dhillon, Karamjeet K. & Ulmer, Jasmine B. (2017). Visual methodologies for research with refugee youth. Intercultural Education, 28(2), 131-142.

MacKenzie, Catriona; McDowell, Christopher & Pittaway, Eileen (2007). Beyond "do no harm": The challenge of constructing ethical relationships in refugee research. Journal of Refugee Studies, 20(2), 299-319.

Marshall, Judi & Reason, Peter (2007). Quality in research as "taking an attitude of inquiry". Magement Research News, 30, 368-380.

Massey, Doreen (2005). For space. London: Sage.

Massey, Douglas S. (1990). Social structure, household strategies, and the cumulative causation of migration. Population Index, 56, 3-26.

Massey, Douglas S. & Espinosa, Kristin E. (1997). What's driving Mexico-U.S. migration? A theoretical, empirical, and policy analysis. American Journal of Sociology, 102, 939-999.