Volume 9, No. 1, Art. 10 – January 2008

Case Reconstruction, Network Research and Perspectives of a Procedural Methodology

Stephan Lorenz

Abstract: The procedure Bruno LATOUR developed in Politics of nature (2004) is interpreted in a methodical way and in relation to proved methods of case reconstruction. The resulting methodological model, referred to as a procedural methodology, is outlined and discussed, including its promises and problems. The procedural methodology is appropriate for integrating the various requirements for doing research and it builds bridges across different "qualitative" methods, methodology, and contemporary society analysis, just as between social and environmental research. Its main characteristics are worked out as procedurality, sequentiality, multidimensionality, reflexivity, and transdisciplinarity.

Key words: methodology; case reconstruction; grounded theory; objective hermeneutics; network; sociological theory; Latour; environmental sociology; transdisciplinarity

Table of Contents

1. Bruno LATOUR's Procedure Model

2. Methodical Interpretation

2.1 Research process

2.2 Techniques of interpretation

2.3 Generalization

3. Consequences of a Procedural Methodology

4. Outlook: Quantitative, Qualitative or Procedural Research—A Question of Time?

A combination of different methods is expected to discover new findings and is often essentially required to special research subjects, e.g. in environmental or sustainable research. The more heterogeneous these methods are, the more methodological reasons must be given to legitimate different methods combinations. Hence, the attempt to win a joint and generalized perspective on different methods of qualitative research is made. These are in particular assorted case reconstruction methods, namely Grounded Theory and Objective Hermeneutics, as well as the network approach, which is linked to LATOUR's Actor-Network Theory. In respect to develop an integrative perspective, I referred to Bruno LATOUR's "political" procedure model. In comparison to the older Actor-Network Theory1), which was elaborated in a four-phase translation model of network construction (CALLON, 1986), it is based on the procedure model from Politics of Nature2). Thus, in my interpretation, case reconstruction methods can be associated with new methodological contexts. [1]

If successfully accomplished, this paves the way for incorporating other qualitative methods into a procedural methodology. This promises to be an extremely productive path since it allows combining rather heterogeneous methods and research requirements. Furthermore, the procedural model provides specific criteria for gauging research because it offers links to contemporary sociological analysis by way of sharing the same central structural problem: uncertainty—that is how to deal with equivocal demands and contingent options. The most sophisticated answers to this problem that social theory has in store are of a reflexive and procedural nature and seek to process rather than eliminate uncertainty3)—in other words, the ability to adapt is retained by avoiding ultimate postulates. LATOUR's approach (2001a) explicitly aims at addressing uncertainty via a "political" procedure, which by design produces only interim results. Thus, dealing with uncertainty is the meta-requirement underlying the seven procedural requirements discussed below. [2]

A procedural methodology can serve to provide an empirical foundation to social analysis. In a reflexive manner it places the structural problem of uncertainty into the center of this methodology. The common structural problem becomes the theoretical, methodological and empirical uncertainty. Thus criteria of quality and evaluation are provided for either the empirical research itself or the research subject showing if uncertainties are empirically eliminated, "shortened" or procedurally handled respectively. [3]

The basics of the methodological program will be outlined and discussed in this article. LATOUR's process model will firstly be displayed and its particular scientific competences will be postulated (1). In this context it will be shown how different methods and research demands, techniques of interpretation as well as possibilities of generalization, can be illustrated within this model (2). Afterwards the results of this methodological conception will be discussed, both—potential chances and problems (3). In the end an outlook on a more general significance of the procedural methodology within contemporary methods and research discussions will be given. [4]

1. Bruno LATOUR's4) Procedure Model

In Politics of Nature, Bruno LATOUR (2004, 2001a) developed a procedural model of politics. The adherence of the model is expected to ensure that all the concepts of similar meaning, such as the "collective," "the common world," as well as the "republic" will be democratically composed step by step. This essentially means that none and no one will be excluded in advance. Human as well as non human beings shall have the opportunity to assemble in a self-understanding collective or shall explicitly be excluded of this. In a wider sense, it is a politicized model of reality and knowledge. "Politics" is therefore related to the generating process of shared realness, which is basically legitimated through the adherence of the procedures. [5]

I now wish to examine to what extent this procedure can be used as a guideline for methods. This examination seems to be more promising than concentrating on the network imagery of LATOUR's Actor-Network-Theory, which he himself never used in Politics of Nature.5) In this context, I will instead refer to the methodically productive concepts of the "assembly" and the "procedure." This methodological perspective can be justified by two specific reasons: 1. LATOUR himself (being a sociologist of sciences) regards the "political" procedure as being modeled on scientific experiments.6) Thus, he talks about an experimental procedure and its experimental records (protocols). 2. Sciences are expected to deal with the procedure demands by particular competences (besides other professions). [6]

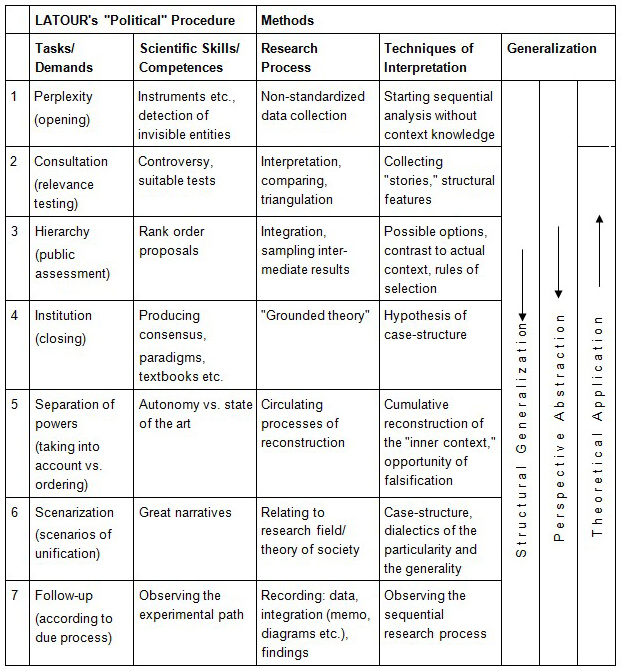

LATOUR's procedural model is displayed in the following table. It shows seven designated demands, together with the appropriate scientific competences. Furthermore, it demonstrates the methodological interpretation, which will be discussed in the following paragraphs in more detail.

Table 1: Procedural model and methodological interpretation [7]

Process tasks and scientific competences: There are seven tasks to accomplish within the procedure. Since the end of the procedure turns into a new beginning, instead of coming to a final settlement, these tasks have to be worked on in either a successive (1-4, 6) or parallel (5, 7) way.7) Science comprises special skills and competences—as other professions (politics, economics ...)—when coping with procedural demands, meaning sciences as well have to participate in all of these tasks (not only in some it). [8]

LATOUR designates the first task as perplexity—meaning openness towards the new. More precisely it is the openness to integrate new members (called "propositions" as "associations between humans and nonhumans," see LATOUR, 2001a, pp.286, 297) into a collective due to the process of investigation. At this point it becomes obvious that scientists dispose lots of instruments that enable them to perceive new entities. By discovering the new, scientists let "the world speak" and "things articulate themselves" (see LATOUR, 2001a, pp.93ff., 116ff.): Therefore, it is necessary to deal with "the world" in a new manner. Hence, the second task is introduced: The relevance tests (consultation). What are the qualities of the new, what are its characteristics, and how can one deal with it? A variety of scientific tests is conducted and discussed in a controversial manner. As a third step, sciences offer arrangement proposals. In order to define the significance of the new, it is hypothetically integrated into an existing public order or into scientific knowledge respectively. In a fourth step, the procedure succeeds by a process of closure: The new entities convert into established ones and become part of paradigms, textbooks, seminars, institutes etc.—of the common world. [9]

In the (democratic) procedure the first two tasks form the power of involvement (LATOUR: "power to take into account"), which is indicated by openness for the new, curiosity and attention. Tasks three and four constitute the regulative power ("power to put into order"). It is the supporting force, which keeps up established structures and functions. While the "power of involvement" permanently challenges the established order by the new, the "regulative power" restricts access to the new. To guarantee both functions, the procedure meets a fifth requirement, namely the separation of these powers. Hence, the scientific competence allows a distinction between the current state of research on one hand, and the autonomy of researching on the other. [10]

The composed or articulated collective needs a sixth requirement: The "scenarization of unification." It involves imaginations of the common world as well as the comprehensive self- and world-understanding. Therefore, sciences provide "great narratives," e.g. provisional theoretical interpretations, and multiply them. Finally, the observation of the whole procedure has to be controlled in task seven. The observation and documentation of the experimental record ("protocol") provides the basis for the creation of learning processes due to scheduled iterated procedures. [11]

LATOUR's procedure model guarantees a democratic composition of the collective. What has formally been excluded during the procedure may always claim access again. There is no final end in the procedural model because of the ongoing, never ending, process. [12]

There are three possibilities to represent LATOUR's process model in a methodical way. Firstly, the model will be set in relation to the research process as a whole. Secondly, as an interpretation technique itself, and it will thirdly refer to generalizations. Thus, the elements of the proven case reconstruction methods will be displayed by LATOUR's process model. The research process is represented by the methodology of Grounded Theory (STRAUSS, 1994; STRAUSS & CORBIN, 1996), whereas the techniques of interpretation will be represented by the methods of Objective Hermeneutics (OEVERMANN, 1996, 2000a).8) In the following paragraphs it will proved that this model-conception combines and integrates different methodical requirements and approaches. [13]

According to Grounded Theory Methodology (GTM) sensu STRAUSS (and CORBIN) a precondition of discovering new findings is an unbiased view of the world. It is not an uninformed view because knowledge, interests and pre-understandings have been explicated as far as possible. Then, surveys that are not standardized assure informative data. Secondly, these data are extensively interpreted and compared. As a third step, it is possible to elaborate memos and diagrams of integration (STRAUSS, 1994), meaning to construct hypothetical relations. New comparative perspectives are developed. If this procedure has made progress so far, it fourthly leads to the implementation of Grounded Theory (GT). Within this research process it becomes apparent that data collection and data analysis mutually refer to each other (see HILDENBRAND, 2000, pp.33ff.). This assumption is almost similar to LATOUR's process model because the beginning and the end of the procedure merge consistently into one another. Hence, it fulfills a necessary fifth task: The separation of powers. This step allows both powers to define the intermediate results ("ordering") as well as to take these again into consideration by new data ("taking into account"). The sixth task has to be realized: The scenarization of a comprehensive image. In the context of the research process it means that the results have to be related to corresponding fields of societal theories. Thus, the findings can be differentiated or classified respectively according to a wider research context. [14]

The research process needs to be recorded and documented ab initio. That is the basic principle to gain a cumulative insight. To put it bluntly, it is always possible to return to older data even if the last page of the research report is being written (STRAUSS, 1994, p.46). While the GT can be displayed by LATOUR's procedure model, the GTM provides some research resources which specify the conceptional procedure in a methodical way. Particularly, the possibilities of data collection and interpretation such as cumulative integration and comparing have to be mentioned (encoding paradigm, theoretical sampling etc.).9) [15]

2.2 Techniques of interpretation

The verification of LATOUR's procedure model for interpretation presupposes a change of perspective. While the research process has previously been considered a whole, the procedure will now focus on data in detail. The procedure will start at single sequences being either a sentence or a phrase, or just a single word. Consequently, the sequential analysis by OEVERMANN will be displayed along the procedure demands (see Table 1). [16]

The first task of LATOUR's procedure model—perplexity—will be ensured due to the methodological negation of context knowledge. By this means the unbiased analysis of the respective part of the text can (newly) be regarded as unknown. The second step—the consultation—is realized by collecting everyday narratives ("stories") relating to this sequence. Hence, the objective meaning consisting of structural features and general readings can be extracted. The confrontation of the objective meaning with the given context fulfills task three, i.e. hypothetically contrasting the general meaning with the actual text to generate the concrete meaning. The continuation of the detailed sequential analysis shows the selection rules as particular meaning of the case against the background of the objective meaning. Thus, as task four, the case structure can be formulated as a strong and momentous hypothesis that is relevant for falsification (see WERNET, 2000, p.68). [17]

The potential falsification or differentiation refers to the permanently new beginning of the procedure at any further text sequence. The explicit possibility of falsification accomplishes task five, the separation of powers. This constitutes the methodical disconnection of the structural hypothesis and the further extensive interpretation of the following text sequence. Task six, the scenarization, can be paraphrased by the means Objective Hermeneutics: The dialectics of the particularity and generality reconstructs the case structure as one possible structural option amongst others. For every single case reconstruction the "demand of particularity" as well as the "demand of generality" (OEVERMANN, 2000a, pp.123f.) is applied. According to OEVERMANN (1996, p.17) this is the reason why always more than one case is known by a single case reconstruction. Task seven is finally realized by the exact compliance of sequentiality. It guarantees successive progression in the discovery process until the case structure is completely reconstructed. [18]

As said above, a proven method enables to transform LATOUR's abstract procedure into concrete terms. In this case, Objective Hermeneutics provides the means to take the procedure as a technique of interpretation. [19]

Referring to an interpretation of the procedural model as a possibility of methodical generalizations, I would like to discuss three variants, namely the structure generalization, perspective abstraction and theory application. [20]

The structure generalization concept10) again relies on the work of OEVERMANN (1996, 2000a). As a matter of fact there is no methodical difference to what has already been achieved by the sequential case reconstruction (see above: interpretation technique) because the sequential analysis always also raises the "demand of generality," as already seen. In other words: A case reconstruction is always a genuine, original determination of a type (OEVERMANN, 1996, p.15, see also 2000a, p.58 and WERNET, 2000, pp.19f.). Therefore, Table 1 displays the structural generalization parallel to the notes about the interpretation technique over the entire procedure. [21]

Perspective abstraction does not mean anything else than a structure generalization just with a varied perspective of questioning. The case reconstruction always follows a particular question, which itself can be asked more generally. The results of case reconstruction are not simply generalized meaning the generalization has to be grounded in the data as well. The whole work of interpretation is newly required from the same data (see Table 1). Depending on research interests, it may be useful to complete the case reconstruction by such a special kind of generalization (see for example LORENZ, 2005, pp.231ff; 2007a). [22]

Thirdly, the application of theories or theoretical paradigms enables to put empirical phenomena in a more general context. Depending on special interests in knowledge or use, it could be of importance as well (see again LORENZ, 2005, pp.231ff.; LORENZ, 2007a). Displayed against the background of the procedural model one immediately notices the limited powers of persuasion as well as the particular requirements. That is why the path of the process is just turned around (see the arrow in Table 1). Therefore it must be questioned if this is admissible at all. Following this way it is obviously not possible to discover really new findings because the task of perplexity is failed. On the other hand one might argue that just the observance of the procedure—although in reverse—offers criteria for a professional application of theory. So far as the validity of procedure demands is acknowledged in principle the subject of research or application respectively is not simply subsumed. Of course, the case is analyzed out of the theory, but still along the procedure in reverse direction. Thus it has not been "forgotten" that theoretical validity results from processes of negotiation which might have taken quite other courses by little deviations.11) This acknowledgment guarantees the readiness to re-start the procedure at any time. [23]

3. Consequences of a Procedural Methodology

The explanations above have demonstrated that LATOUR's procedural model can be interpreted in methodical terms without any problem. On one hand this model enables to formulate the basics of a general methodological concept—of a procedural methodology—which allows to integrate different methodical demands and approaches. On the other hand the established approaches offer possibilities to realize concrete research demands according to the abstract procedure. [24]

The represented suitability of the procedure model gives sufficient reason to develop such a procedural methodology. However, further chances and problems, which are connected with the integration of case reconstructive social research methods and LATOUR's perspective of environmental sociology, must be sketched. [25]

1. Case versus network: The case concept can be applied to very different research objects. However, it is not always made clear what precisely is referred to as the "case". In particular, the case is often not clearly distinguished from research interests, research questions, objects of research and/or data. Such imprecision is even found in distinguished textbooks and manuals (see for example WERNET, 2000, p.50; BUDE, 2006, p.60). In case of aggregate entities all the way up to entire societies, the proper delimitation of the research object can only be established in the course of the research process. The case determination must therefore be seen as the result of the research process rather than as its precondition (see MAIWALD, 2005). The case concept is most convincing whenever a case largely corresponds with a person. However, the connection with persons provides a basis for the comparison of cases beyond the "single case" analysis. If this homogeneousness and comparability is not given, the network concept might be more productive. In this way it will obviously be widespread in (laboratory) science and engineering research. The problems connected with "network" have partly been mentioned above and will be discussed further below. Anyway, the potential of the procedural concept is to be applicable to case studies as well as network research. [26]

2. Assembly (and collective) instead of network12): (German) environmental sociology has recited LATOUR mostly in a theoretical manner, while the methodical discussion has made less progress (see BRAND & KROPP, 2004; VOSS & PEUKER, 2006). Where it is debated it is related to the Actor-Network Theory as developed in sciences and engineering research. Following the criteria of case reconstructive social research, LATOUR's procedural model, methodologically interpreted, turns out to be highly productive. The "political" procedure as a methodical guide is possibly more beneficial for environmental sociology than the network-metaphor. The attempt to link everything with everything and "to follow the actors" will probably result in a standstill. Instead of analyzing the plurality, it is performed rhetorically and selected intuitively—so to speak it tends to become research at will, e.g. unimportant. The only quantitative multiplication of references in postulated networks is hardly appropriate to gain knowledge. Against that, the differentiation between the "power to take into account" and the "power to put into order" and then the procedural connection of both is more promising. Thus, there are good prospects for cumulative findings because both are methodically assured: Instead of following the actors, one will sequentially discover which ways they did not go and to which selection rules they obeyed on their course. [27]

In Politics of Nature LATOUR establishes the concept of the "collective" which is constituted by the "political" process. At least in Germany the concept of collective is politically burdened. Therefore, it is better to speak of an "assembly," which LATOUR himself used and which meets as well all the political and content implications. In contrast to the network, the concept of assembly includes the movements between common grounds and dividing lines. The network suggests a connection of all and can rarely show political dividing-lines. In an assembly people having quite different opinions, interests, and positions come together. Whereas one expects conflicts as well as controversies about the shared subject of the assembly, others don't. Eventually there is an exit or exclusion option. However after all the "assembly" always implicates rules—no matter if these rules of assembling are observed or violated. [28]

3. Reality model and method I: The activity of research is still mentioned, namely as the "work of assembling." In this case the "work of assembling" stands for both: a model of reality and methodical acting. This method has actually been borrowed from the understanding of reality and is therefore appropriate to function as a reconstruction methodology. It is therefore a shared characteristic with the case reconstructive approaches which develop their methodical doctrines hand in hand with their understanding of everyday life. The methodology of Grounded Theory draws no distinct line between everyday acting and research. Thus, the latter is just relieved of concrete action pressure and the routines of everyday life. OEVERMANN regards everyday acting as sequentially structured. He organizes the methodical acting as well in a sequential way.13) The researcher does not get entangled in the great network because of the relative differentiation between subject and method. Out of this reason the researcher takes a distanced point of view without establishing an absolute difference. [29]

4. Sophisticated procedure, reduced concept of action: There is also a difference between researched reality and method in that the methodical model by design has to be as comprehensive and demanding as possible whereas in the reality of research we must expect short cuts and other procedural strategies pulling in the opposite direction. LATOUR's model is conceived to satisfy sophisticated demands and is elaborated in contrast to simplified conceptions (2001a, pp.127ff.). Drawing on OEVERMANN, it can be characterized as a model of crisis and not of routine.14) Therefore, it is not the only real and legitimate one but nevertheless has to make a comprehensive claim. Simplification in empirical reality (resulting from routines, action for the sake of action, ideology or exertion of power) can only be identified in view of the entire, unabridged process.15) Only such a comprehensive view puts us in a position to judge whether dropping certain steps of the procedure might be acceptable. In a similar manner, this also applies to case-reconstructive social research. Researchers must be free from the need to act and have to command (procedural) competence or at least some degree of knowledge beyond the everyday common sense level, otherwise it would be impossible to compare and systematize different cases. [30]

The demanding procedure model contrasts with a widened but therefore also reduced understanding of action. In his endeavor to give "things" a seat in the "assembly," for LATOUR (2001a, p.108), any modifying transformation becomes an action. So the question is how far such "acting" things, with such a minimum of skills, could be able to meet the demands of the procedure. Even if, for environmental or engineering research interests, one accepts such a concept of action as a basic concept, the need to qualify the acting contributions is raised.16) A qualification could be at least discussed. However, is it not just the refusal of qualification, which at least could be contested, that implicitly plays to the advantage of an informal expert takeover of the due process? From a methodical viewpoint, this centrally concerns the differentiation between researcher and object of research and, in a wider sense, between research objects constituted through social meaning and those that exist apart from such meaning. [31]

5. Reality model and method II: The orientation of the comprehensively formulated methodology on the understanding of the object enables to recognize the empirical (none) realization of the procedure. Of course, the methodical demands and competences are not the same as those on the object side. However, method and object share the common "meta"-demands of the procedurality itself, e.g. the never closing process and the creation demand connected to it. The tasks have to be reformulated in the relation to the object in question. This would be possibly hypothetical as far as it is oriented at the procedure model.17) This must of course be understood as a result and not as the starting point of the inquiry. [32]

6. Dialectics and network: LATOUR's reproach is rhetorically convincing: dialectics always depend on the separation of what belongs together, namely nature and society (see 2001a, pp.73ff.). However, dialectics do not separate. It actually unifies what has been separated or what is separating. There is sensitivity for connections as well as for distances which need to be denied in the "great network."18) In the network one follows (often more intuitively, selectively at random) the (sense-) relations that are always given explicitly or implicitly (with any utterance, any action, any event ...) but only horizontally, at the same "level." Dialectics can change levels. This allows a qualification of sense relations which is achieved by the dialectics of generality and particularity. Thus, the structural generalization is made possible. The procedure model on the other hand enables both: horizontal relations which became particularly relevant in earlier steps as well as vertical relations in subsequent steps of the procedure. [33]

Besides the differentiations on the object there are also differences in the relation of researchers and the objects of investigation (see above, reality model and method I). The network approach radicalizes the participant perspective: Researchers are always part of what is going on, they cannot jump out of the "great network." In the dialectics one would neither take only an observing position nor get entangled with the object; instead one reflects a distancing relation to it. [34]

7. Transdisciplinarity and sense: The aspirations of case-reconstructive research and environmental sociology are very akin if one conceives of transdisciplinarity as an approach to research that involves a variety of disciplines and is geared toward providing practical knowledge. "Qualitative" methods are not limited to certain humanities or social science disciplines (HITZLER, 2007). From professional research one may learn in which way research knowledge can be applied to social practice. However, within "qualitative" research there are deep divergences according to HITZLER which are crucially connected with the understanding of sense and its interpretation. Here, it seems to be obvious to search for a comprehensive, common "sense"-paradigm. From an environmental-sociological point of view another conclusion is of course possible. In fact a strong advocated position is found in environmental sociology, e.g. by systems theory: the differentiation of nature and society finds a non-crossing difference in the distinction of sense versus non-sense. On the other hand there is a similarly strong position, being for example connected with LATOUR's concepts. One might therefore ask why the variety of sense concepts can be explained in a way in which no clear boundaries between sense and non-sense exist. For transdisciplinary environmental research the clarification of these dividing-lines is even more important because the integration of nature and its sciences into its own work should be possible. By his procedure LATOUR offers a model that formulates the claim to overcome the separation of nature and society by the "political" assembly. Whether he is actually successful or if he has essentially presented a polemic against the "theorists of differences" is not settled yet. The procedural model—in its abstract shape—could probably be used by the sciences in various ways, not at last because it derives from the scrutiny of laboratory experiments by the sociology of sciences. However, the differences between nature and society, subject and object etc. have not yet been overcome. Therefore, we should again refer to a pending differentiation and qualification of a concept of action (see above, sophisticated procedure, reduced concept of action). As long as environmental sociology wants to realize the integration of nature and society by reducing strategies, it will rightly meet considerable opposition within sociology. [35]

4. Outlook: Quantitative, Qualitative or Procedural Research—A Question of Time?

The controversies amongst supporters of varied research approaches have traditionally been related to quantitative concepts on one hand and qualitative concepts on the other. What "quantitative" actually means is pretty easy to explain: Investigations are depicted in ratios by the help of mathematical operations. Apart from that anything else is "qualitative." It obviously says nothing about research quality at all which leads to the assumption that it could be good or bad in both approaches. Quantitative research can never work without qualitative elements such as suggesting hypothesis, designing research, interpreting results etc. Doing "quantitative" research simply means using special techniques of handling data. Conversely, qualitative research would prematurely give up the use of numbers and figures if it were to define itself merely as "not quantitative." [36]

The distinction between quantitative and qualitative research as a question of paradigms is an asymmetrical manner right from the beginning on. Other differentiations have therefore been tried to meet the matter better. Relating to data collection, we might differentiate between standardized and not standardized approaches with a large area of more or less standardized collections. Relating to research process another way is the characterization of reconstruction on one hand and the subsuming on the other—known from OEVERMANN (1996, see BOHNSACK, 1993). Then the confrontation of understanding versus explanation as a third version, namely the questioning of the meaning of "sense," is introduced as recently advocated again by HITZLER (2007). [37]

The procedural understanding of research does not work along these differentiation patterns. At best it converges with a reconstructive approach. In this case it becomes obvious that the procedural methodology does not only mark the logics of research. It also questions the strict distinction between areas constituted by meaning and areas existing apart from meaning19) and does not exclude "subsuming" elements as far as the procedure allows to methodically control the process of doing so (as a deliberate short cut or reversal of the procedure).20) Due to these reasons the procedural understanding of research is not necessarily related to a dichotomy-constructed opponent. [38]

The chances and limits of a procedural methodology are closely connected to the sociological analysis of contemporary society mentioned at the beginning of this article, and, in a wide sense, represents the political dimension of such a methodology. In a modern society, observations of social uncertainties and insecurities are plentiful. Whether they are described as late modern confusion ("Unübersichtlichkeit"; HABERMAS, 1996), traced to acceleration processes (ROSA 2005), increased diversity of options (SCHULZE, 1992; GROSS, 1994), and processes of disembedding associated with the welfare state (CASTEL, 2000), or analyzed as reflexive modern (BECK, GIDDENS & LASH, 1996), post modern (BAUMANN, 2003) or "amodern" (LATOUR, 1995) is of secondary importance to our context. Claims of a procedural methodology being appropriate to the times nevertheless to some extent requires taking a stance on contemporary social analyses. There must neither be calling for "anything goes" nor is there any need to fall into the new-old certainties following the usual lamentations of loss. The procedural methodology organizes multilayered and mutually related learning processes—from detailed interpretations as far as to whole research projects. Procedural methodology proceeds uncertainty and does not eliminate it; it sustains uncertainty and just suspends it temporarily. Furthermore, the procedural methodology rests on a research understanding that is basically transdisciplinarily oriented. Hence, it enables problem-related research (see GROSS, 2006; BECHMANN, 2000), e.g. researching actors are regarded as actors amongst others of the same value cooperating with them with special competences. [39]

To sum up, five important hallmarks of the procedural methodology can be characterized. At the beginning there are the concepts of procedurality and sequentiality meaning that an orientation for the procedure is observed successively as well as entirely over and over again. The third hallmark the multidimensionality consists of an interlinked plurality of procedure paths which spread to different levels. In connection to this crucial point the fourth hallmark is introduced, namely reflexivity, meaning to create a relation between the understanding of object and method within the context of a diagnostics of contemporary society. At this point a bridge to problem-related research arises and thus it results in the fifth hallmark, the transdisciplinarity. [40]

So the procedural methodology stands for a promising program, on the one hand. On the other hand, it is just a new perspective which definitely needs and responses to given and proven methods. Being just a procedure model, meaning being nothing more than a theoretical "skeleton," it can only gain its "flesh," its strength from the experience of research methods. The procedure defines requirements that have to be dealt with. How this is to be accomplished in concrete instances and in view of concrete research objects requires a further specification of concrete methodical means. The contribution of a procedural methodology is an offer of interpretation which newly sorts out the variety of methods in an "up to date" manner and integrates them (so to speak: assembles them). Whether, in the end, LATOUR's process model—with its seven tasks—provides the best foundation for this or which elements of the proven methods could constitute basic components of a procedural methodology—these questions and all the problems raised above can only be stated here. They need controversial discussions and differentiating answers. The procedure and the procedure of the procedure have to be started again. [41]

1) Also take a look at my article (LORENZ, 2008a) which has not yet been mentioned in the German copy. <back>

2) The German translation of the original title Politiques de la nature is given as Das Parlament der Dinge (LATOUR, 2001a), in English: Politics of Nature (LATOUR, 2004). I will therefore use in the German version the expression "parlamentarisches Verfahren" (parliamentary procedure) instead of "political procedure." There is of course a difference because the term "parliamentary" emphasizes the democratic kind of political procedures. <back>

3) Elsewhere I have discussed these questions around uncertainty, between theory of society and its empirical research, exemplified on the basis of organic food consumption (LORENZ, 2007a, 2005). Here it is just important to clear up the problem of uncertainty as a structurally shared one for theoretical as well as empirical subjects and methods. It actually underlines the (connecting) significance of the procedurality, as a particular way of dealing with uncertainty for the developed methodology in this article. <back>

4) The methodical presentation as well as interpretation of LATOUR's concept (see Section 1 and 2) were first elaborated in LORENZ (2008b). The results were transferred from this article to a great extent. <back>

5) LATOUR himself refers critically to the terminology of the Actor-Network Theory and its problems: "I will start by saying that there are four things that do not work with actor-network theory; the word actor, the word network, the word theory and the hyphen!" (LATOUR, 1999, p.15) He nevertheless stays with this choice of words (see LATOUR, 2005). <back>

6) See GROSS (2006) for a discussion of LATOUR's notion of experiment in comparison to the scientific one. The thrust of GROSS's reasoning in the paragraph "Ausblick: Experimentelle Praxis als Prozeduralisierung von Kontingenz" (p.178) largely corresponds with the main concern of this article; its basic methodological underpinnings will be outlined below. <back>

7) See LATOUR (2001a, pp.180ff., 206ff.; for a diagram displaying the proceedings pp.163, 181). LATOUR (pp.150ff.) discusses tasks one to four by the example of prions (proteins probably responsible for "mad cow disease"). <back>

8) Elsewhere I elaborated the particular suitability of Grounded Theory Methodology for the research process on the whole and the suitability of Objective Hermeneutics as a technique of interpretation. However, this differentiation is just simplified. Both methods should be perceived more comprehensively in a complementary relation (LORENZ, 2005, pp.67ff., see also HILDENBRAND, 2004). See LORENZ (2006) for some basic information on the here presented considerations about the relation between case reconstruction methods and LATOUR, or more generally: about transdisciplinary methods. <back>

9) That GTM perfectly fits in with a procedural methodology can be argued from a theory of science perspective drawing by STRÜBING (2004), who elaborates the "iterative cyclical approach" as a main feature of GTM. <back>

10) The fact that LATOUR (see 2001a, b) opposes against structuralistic theory is not important at this point. The procedure can actually be read as a structural generalization. Moreover, according to his procedural model (not to the Actor-Network approach) one might ask if he really avoids a structural concept or not. <back>

11) We might, for example, think of a physician who makes his diagnosis quite fast based on a few symptoms. In this case the professionalism would be less characterized by routine short cuts of scrutiny rather than by going back through the procedure. All procedure steps are acknowledged then. That ensures the sensitivity to go in the direction of the "due process" of face application problems. <back>

12) In a later article (LORENZ, 2008a) I have made my point more clear: The problem of Actor-Network Theory is not the use of "network" but its double use and meaning. There is a general understanding of a "networked world' and another one of constructed networks according to the above (paragraph [1]) mentioned Actor-Network Theory model. BOLTANSKI and CHIAPELLO (2003) for example distinguish the "project" from the network. The "project" constitutes an operating structure within a world of only flexible connections. Similarly the assembly (or collective) must be regarded as such an operational structure within unstructured (potential) connections. <back>

13) The categorical difference OEVERMANN postulates between theory and practice is based on the differentiation between the logics of knowledge and the logics of action (OEVERMANN 2000b). Occasionally it is over-stressed (and strictly applied it would not permit any problem-related co-operation of scientific and non-scientific actors). The intention is not to oppress practical work by research (LORENZ 2005, p.73, fn.116). <back>

14) LATOUR (2001a) himself refers to HABERMAS' procedural understanding of politics. HABERMAS' claim is not to reduce social phenomena—especially from normative aspects—by making theoretical decisions in advance (HABERMAS, 1994). The difference to HABERMAS is at least the understanding of action. <back>

15) As an example I refer to LORENZ (2007a). The text describes the autochthonous reflexive and "shortened" patterns of orientation on the basis of organic-food consumption which are related, amongst others, to the LATOURian theory. <back>

16) A variety of action types is given by HABERMAS (1988), which can be applied here. For an instructive, systematic-idealtypical contrasting of engineering versus educational acting see GIEGEL (1998). "Things" could be qualified as ILLICH has done with the "tools" (1998, pp.48, 57ff.). <back>

17) As an example for education to sustainable development, see LORENZ (2007b). <back>

18) Elsewhere (LORENZ 2006, p.124) I referred to the proclamation of the "end of nature." By giving up all differences between nature and society one eliminates uncertainties, which should be avoided by the procedural concept. <back>

19) On one hand OEVERMANN differentiates between sciences and humanities as well the differentiation between sense-structured and non sense-structured research subjects. On the other hand he takes the validity of the sequential analysis approach in sciences as given (1996, pp.4f., 27; 2000a, pp.113f.). <back>

20) OEVERMANN (see for example 1983, p.246) also approves of such "short cuts" for purposes of research economy. <back>

Bauman, Zygmunt (2003/2000). Flüchtige Moderne. Frankfurt a.M.: Suhrkamp.

Bechmann, Gotthard (2000). Das Konzept der "Nachhaltigen Entwicklung" als problemorientierte Forschung—Zum Verhältnis von Normativität und Kognition in der Umweltforschung. In Karl-Werner Brand (Ed.), Nachhaltige Entwicklung und Transdisziplinarität: Besonderheiten, Probleme und Erfordernisse der Nachhaltigkeitsforschung (pp.31-46). Berlin: Analytica-Verlag.

Beck, Ulrich; Giddens, Anthony & Lash, Scott (1996). Reflexive Modernisierung. Eine Kontroverse. Frankfurt a.M.: Suhrkamp.

Bohnsack, Ralf (1993). Rekonstruktive Sozialforschung. Einführung in Methodologie und Praxis qualitativer Forschung (2nd edition). Opladen: Leske & Budrich.

Boltanski, Luc & Chiapello, Ève (2003/1999). Der neue Geist des Kapitalismus. Konstanz: UVK.

Brand, Karl-Werner & Kropp, Cordula (2004). Naturverständnisse in der Soziologie. In Dieter Rink & Monika Wächter (Eds.), Naturverständnisse in der Nachhaltigkeitsforschung (pp.103-140). Frankfurt a.M.: Campus.

Bude, Heinz (2006). Fallrekonstruktion. In Ralf Bohnsack, Winfried Marotzki & Michael Meuser (Eds.), Hauptbegriffe Qualitativer Sozialforschung (2nd edition, pp.60-62). Opladen: Verlag Barbara Budrich.

Callon, Michel (1986). Some elements of a sociology of translation: Domestication of the scallops and the fishermen of St. Brieuc Bay. In John Law (Ed.), Power, action and belief. A new sociology of knowledge? (pp.196-230) London: Routledge & Kegan Paul.

Castel, Robert (2000/1995). Die Metamorphosen der sozialen Frage. Eine Chronik der Lohnarbeit. Konstanz: UVK.

Giegel, Hans-Joachim (1998). Die Polarisierung der gesellschaftlichen Kultur und die Risikokommunikation. In Hans-Joachim Giegel (Ed.), Konflikt in modernen Gesellschaften (pp.89-152). Frankfurt a.M.: Suhrkamp.

Groß, Matthias (2006). Kollektive Experimente im gesellschaftlichen Labor—Bruno Latours tastende Neuordnung des Sozialen. In Martin Voss & Birgit Peuker (Eds.), Verschwindet die Natur? Die Akteur-Netzwerk-Theorie im umweltsoziologischen Diskurs (pp.165-181). Bielefeld: Transcript.

Gross, Peter (1994). Die Multioptionsgesellschaft. Frankfurt a.M.: Suhrkamp.

Habermas, Jürgen (1988/1981). Theorie des kommunikativen Handelns. Frankfurt a.M.: Suhrkamp.

Habermas, Jürgen (1994/1992). Faktizität und Geltung. Beiträge zur Diskurstheorie des Rechts und des demokratischen Rechtsstaats. Frankfurt a.M.: Suhrkamp.

Habermas, Jürgen (1996/1985). Die Neue Unübersichtlichkeit. Frankfurt a.M.: Suhrkamp.

Hildenbrand, Bruno (2000). Anselm Strauss. In Uwe Flick, Ernst von Kardorff & Iris Steinke (Eds.), Qualitative Forschung. Ein Handbuch (pp.32-42). Reinbek: Rowohlt.

Hildenbrand, Bruno (2004). Gemeinsames Ziel, verschiedene Wege: Grounded Theory und Objektive Hermeneutik im Vergleich. Sozialer Sinn, 2, 177-194.

Hitzler, Ronald (2007). Wohin des Wegs? Ein Kommentar zu neueren Entwicklungen in der deutschsprachigen "qualitativen" Sozialforschung. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung / Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 8(3), Art. 4, http://nbn-resolving.de/urn:nbn:de:0114-fqs070344.

Illich, Ivan (1998/1973). Selbstbegrenzung. Eine politische Kritik der Technik. München: C.H.Beck.

Latour, Bruno (1995). Wir sind nie modern gewesen. Versuch einer symmetrischen Anthropologie. Berlin: Akademie-Verlag.

Latour, Bruno (1999). On recalling ANT. In John Law & John Hassard (Eds.), Actor network theory and after (pp.15-25). Oxford: Blackwell.

Latour, Bruno (2001a/1999). Das Parlament der Dinge. Für eine politische Ökologie. Frankfurt a.M.: Suhrkamp.

Latour, Bruno (2001b/1994). Eine Soziologie ohne Objekt? Anmerkungen zur Interobjektivität. In Berliner Journal für Soziologie, 11, 237-252.

Latour, Bruno (2004). Politics of nature. How to bring the sciences into democracy. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Latour, Bruno (2005). Reassembling the social. An introduction to actor-network-theory. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Lorenz, Stephan (2005). Natur und Politik der Biolebensmittelwahl. Kulturelle Orientierungen im Konsumalltag. Berlin: wvb, http://nbn-resolving.de/urn:nbn:de:0168-ssoar-53695.

Lorenz, Stephan (2006). Potenziale fallrekonstruktiver Sozialforschung für transdisziplinäre Umweltforschung. In Martin Voss & Birgit Peuker (Eds.), Verschwindet die Natur? Die Akteur-Netzwerk-Theorie im umweltsoziologischen Diskurs (pp.111-127). Bielefeld: Transcript.

Lorenz, Stephan (2007a). Unsicherheit und Entscheidung—Vier grundlegende Orientierungsmuster am Beispiel des Biokonsums. Schweizerische Zeitschrift für Soziologie, 33(2), 213-235.

Lorenz, Stephan (2007b). Unsicherheit, Reflexivität und Prozeduralität—Zur Empirie und Methodik von Kompetenzkriterien in der Bildung für nachhaltige Entwicklung. In Inka Bormann & Gerhard de Haan (Eds.), Kompetenzen der Bildung für nachhaltige Entwicklung. Operationalisierung, Messung, Rahmenbedingungen, Befunde (pp.123-139). Wiesbaden: VS-Verlag.

Lorenz, Stephan (2008a). Von der Akteur-Netzwerk-Theorie zur prozeduralen Methodologie: Kleidung im Überfluss. In Christian Stegbauer (Ed.), Netzwerkanalyse und Netzwerktheorie. Ein neues Paradigma in den Sozialwissenschaften (pp.579-588). Wiesbaden: VS-Verlag.

Lorenz, Stephan (2008b). Latours "parlamentarisches" Verfahren als Methode—für eine prozedurale Methodologie. In Karl-Siegbert Rehberg (Ed.), Die Natur der Gesellschaft. Verhandlungen des 33. Kongresses der Deutschen Gesellschaft für Soziologie in Kassel 2006 (CD, pp.3653-3661). Frankfurt a.M.: Campus.

Maiwald, Kai-Olaf (2005). Competence and praxis: Sequential analysis in German sociology. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung / Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 6(3), Art. 31, http://nbn-resolving.de/urn:nbn:de:0114-fqs0503310.

Oevermann, Ulrich (1983). Zur Sache. Die Bedeutung von Adornos methodologischem Selbstverständnis für die Begründung einer materialen soziologischen Strukturanalyse. In Ludwig von Friedeburg & Jürgen Habermas (Eds.), Adorno-Konferenz 1983 (pp.234-289). Frankfurt a.M.: Suhrkamp.

Oevermann, Ulrich (1996). Konzeptualisierung von Anwendungsmöglichkeiten und praktischen Arbeitsfeldern der Objektiven Hermeneutik (Manifest der objektiv hermeneutischen Sozialforschung), unpublished manuscript.

Oevermann, Ulrich (2000a). Die Methode der Fallrekonstruktion in der Grundlagenforschung sowie der klinischen und pädagogischen Praxis. In Klaus Kraimer (Ed.). Die Fallrekonstruktion. Sinnverstehen in der sozialwissenschaftlichen Forschung (pp.58-148). Frankfurt a.M.: Suhrkamp.

Oevermann, Ulrich (2000b). Das Verhältnis von Theorie und Praxis im theoretischen Denken von Jürgen Habermas—Einheit oder kategoriale Differenz? In Stefan Müller-Doohm (Ed.), Das Interesse der Vernunft. Rückblicke auf das Werk von Jürgen Habermas seit "Erkenntnis und Interesse" (pp.411-464). Frankfurt a.M.: Suhrkamp.

Rosa, Hartmut (2005). Beschleunigung. Die Veränderung der Zeitstruktur in der Moderne. Frankfurt a.M.: Suhrkamp.

Schulze, Gerhard (1992). Die Erlebnisgesellschaft. Kultursoziologie der Gegenwart. Frankfurt a.M.: Campus.

Strauss, Anselm L. (1994). Grundlagen qualitativer Sozialforschung. Datenanalyse und Theoriebildung in der empirischen und soziologischen Forschung. München: Wilhelm Fink Verlag.

Strauss, Anselm L. & Corbin, Juliet (1996/1990). Grounded Theory. Grundlagen qualitativer Sozialforschung. Weinheim: Beltz.

Strübing, Jörg (2004). Grounded Theory. Zur sozialtheoretischen und epistemologischen Fundierung des Verfahrens der empirisch begründeten Theoriebildung. Wiesbaden: VS Verlag.

Voss, Martin & Peuker, Birgit (Eds.) (2006). Verschwindet die Natur? Die Akteur-Netzwerk-Theorie im umweltsoziologischen Diskurs. Bielefeld: Transcript.

Wernet, Andreas (2000). Einführung in die Interpretationstechnik der objektiven Hermeneutik. Opladen: Leske & Budrich.

Stephan LORENZ, Dr. phil., sociologist (M.A.), is researcher and lecturer at the Friedrich-Schiller-University in Jena (Germany). Beside qualitative methods his research interests include phenomena of the "affluent society," (food) consumption, environment and sustainability and sociology of culture.

Contact:

Stephan Lorenz

Friedrich-Schiller-Universität Jena

Institut für Soziologie

Carl-Zeiss-Str. 2, D-07743 Jena

Germany

Tel.: 03641/945509

Fax: 03641/945512

E-mail: Stephan.Lorenz@uni-jena.de

URL: http://www.soziologie.uni-jena.de/StephanLorenz.html

Lorenz, Stephan (2009). Case Reconstruction, Network Research and Perspectives of a Procedural Methodology [41 paragraphs]. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung / Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 9(1), Art. 10, http://nbn-resolving.de/urn:nbn:de:0114-fqs0801105.