Volume 20, No. 3, Art. 12 – September 2019

Qualitative Content Analysis: From Kracauer's Beginnings to Today's Challenges

Udo Kuckartz

Abstract: At the beginning of the 1950s, when communication research was at its peak, KRACAUER coined the term "qualitative content analysis." Today, the method is one of the most frequently used social research methods in Germany. Building on KRACAUER's line of argument, in this article I identify three fields for further development of the method: first, a more qualitative type of analysis following the formation of categories and the data coding process; second, a case orientation complementing category-based analysis, which is characteristic of qualitative research but has so far played a negligible role in qualitative content analysis; third, a stronger reference to the international methodological discussion where qualitative content analysis remains a little known method. In addition, I further reflect on methodological considerations, concluding by focusing on standards and quality criteria and advocating for the continued development of methodological rigor.

Key words: qualitative analysis methods; qualitative content analysis; category formation; methodological rigor; coding frame; coding; case analysis

Table of Contents

1. Introduction

2. And Beyond 1: Call for a More Strongly Qualitative Analysis (Building on KRACAUER)

3. And Beyond 2: Call for a Supplementary Case Orientation

4. And Beyond 3: Qualitative Content Analysis in the Context of the International Methods Discourse

5. Methodological Aspects of Qualitative Content Analysis

6. Summary and Looking Ahead: Qualitative Content Analysis on the Way to Rigorous Analysis

This article is based on a lecture entitled "Qualitative Content Analysis: From Kracauer's Beginnings to the Concept of 'Rigorous Analysis'," which I gave at the conference "Qualitative Content Analysis – and beyond?" in October 2016 at the Pädagogische Hochschule Weingarten, Germany (JANSSEN, STAMANN, KRUG & NEGELE, 2017). Already, these five words in the conference title "Qualitative Content Analysis – and beyond?" clearly indicate the area of tension in which qualitative content analysis is situated. The three words "qualitative content analysis" are a typical example of what is called "manifest content" in classical content analysis: these words could be reliably and validly coded without any problems. For example, they could be assigned to the category "research methods > qualitative > content analysis," since they clearly do not refer to grounded theory methodology, discourse analysis according to FOUCAULT or—to give an example from the field of quantitative methods—multiple regression analysis. [1]

But what about the two words "– and beyond," and let's not forget the question mark. What is that all about? The original German title of the conference included these words in English, i.e., "Qualitative Inhaltsanalyse – and beyond?" But why this switch to English? Why the preceding dash, and why the question mark at the end? [2]

Two people who think about the title of the meeting and interpret it will still agree that the conference will presumably address discuss topics that go beyond the current state of qualitative content analysis. Perhaps it might also be possible to reach an agreement that these two English words signal that the international discourse on qualitative methods should also play a role at the conference. But the dash and the question mark—by those we might be quickly led into an area of risky interpretation. [3]

The "– and beyond?" might remind you of the mysterious inscription Frederick II. wrote above his newly built Sanssouci Palace in Potsdam in 1747, namely "sans, souci."—with a comma in the middle and a dot at the end. The cultural scholar Heinz Dieter KITTSTEINER (2011) wrote a 92-page book—partly an interpretive parody—on the meaning of that comma: "Das KOMMA von SANS, SOUCI. Ein Forschungsbericht" [The COMMA of SANS, SOUCI. A Research Report]. With this extensive kind of interpretation, he goes beyond the concept of interpretation as this is understood in the context of qualitative content analysis; it may be intellectually brilliant, but there is hardly any chance of achieving an intersubjective agreement of interpretation, and this is a core point of qualitative content analysis. It is based on the presumption that a match is achievable through precise category definitions and training of coders. [4]

Incidentally, Frederick II. might have been amused at KITTSTEINER's interpretation, because his intentions regarding the comma were perhaps completely different to those surmised by KITTSTEINER. Either way, one cannot conclude from the sheer length of the interpretation—and the associated effort—that it is ipso facto a more complete and better interpretation. Well, I don't want to make any further attempts at interpreting the "– and beyond?" at this point. I understand these two words as an invitation to reflect "beyond," to point out perspectives and innovation potentials that go beyond the current state of qualitative content analysis and which are worth discussing. [5]

The "qualitative content analysis" method has been extremely popular in German-speaking countries for some time and has been described in detail in the relevant literature (KUCKARTZ, 2014, 2018; MAYRING, 2015 [1983]; SCHREIER, 2012, 2014; STAMANN, JANSSEN & SCHREIER, 2016). In the "Handbuch Methoden der empirischen Sozialforschung" [Handbook of Methods of Empirical Social Research] published by Nina BAUR and Jörg BLASIUS (2014), which is one of the most successful books in the social sciences with more than eight million downloads1), the chapter on qualitative content analysis tops the ranking list of the most frequently downloaded articles with more than 105.000 downloads. You can also look at the fact that workshops on qualitative content analysis, such as the Berliner Methodentreffen, the largest German-language conference on qualitative methods, are the first to be fully booked. On the other hand, it cannot be denied that in project outlines and third-party funding applications, qualitative content analysis is often only mentioned in the form of name-dropping. In many project proposals, methods sections contain phrases like the following: "The data was analyzed following the qualitative content analysis method" or even shorter "analyzed according to Mayring" or "analyzed according to Kuckartz." Applicants seem to assume that the method of analysis has already been sufficiently described and completely overlook the fact that there are different variations of qualitative content analysis. In my book "Qualitative Text Analysis" (KUCKARTZ, 2014), I differentiate between three main forms, MAYRING (2015 [1983]) distinguishes as many as eight different variations, not to mention the many others described by Margrit SCHREIER (2014) in a thoroughly systematized way (see also STAMANN et al., 2016). [6]

For this reason, in the following article I should not actually speak of "the" qualitative content analysis, but always refer to it in the plural as qualitative content analyses. That would certainly be more correct, but it is a bit cumbersome, which is why I prefer to do without it. With regard to the content of this article, the commonalities of the different variations are also sufficiently great to justify this. [7]

Back to the title of the Weingarten conference "Qualitative Content Analysis – and beyond?." Three points that I find particularly interesting for a discussion about "and beyond" are dealt with in the following,

firstly, an expanded view towards a more strongly qualitative analysis (Section 2),

secondly, an extension towards a case-oriented perspective (Section 3), and

thirdly, an expanded view in the direction of the international methods discourse (Section 4). [8]

As the title of this article indicates, I will trace a line from KRACAUER's beginnings to meaningful extensions of contemporary qualitative content analysis as a methodologically rigorous process. Over the course of the conference, and at the various forums, many questions were raised—both very general, with an epistemological and methodological background, and very specific, with concrete references to research techniques. Accordingly, in Section 5, I address some of the basic methodological issues. [9]

2. And Beyond 1: Call for a More Strongly Qualitative Analysis (Building on KRACAUER)

KRACAUER—this is unfortunately largely unknown—was in fact the person who in the early 1950s deliberately introduced the term "qualitative content analysis" into the world of research methods or, more specifically, content analysis (KRACAUER, 1952). He was an empirical sociologist, journalist and philosopher and was associated in many ways with the Frankfurt School (KRACAUER & BENJAMIN, 1974; SPÄTER, 2016). In 1933 he emigrated to France and later to the USA, where he became familiar with American propaganda research, which primarily worked with content analysis (KRIPPENDORFF, 2012). American propaganda research during the Second World War was well known, received considerable funding, and its method was specifically called "content analysis." In other words, in the consciousness of the general public, and also within the English-speaking scientific community, a link was created between a concrete research practice and the name of a method that continues to have an effect to this day. [10]

In 1952, in an essay entitled "The Challenge of Qualitative Content Analysis," KRACAUER criticized the prominent methodological concept of content analysis in propaganda research, as expressed in particular in the works of Harold LASSWELL (JANOWITZ, 1968) and Bernard BERELSON (1952) in the well-known definition "Content Analysis is a research technique for the objective, systematic, and quantitative description of manifest content of communications" (BERELSON, 1952, p.18). BERELSON had intended to restrict content analysis to the analysis of manifest content. KRACAUER criticized this programmatic limitation to the manifest content and pleaded for a broader content analysis, which also allows researchers to take into account the latent content, and he chose the term "qualitative content analysis." [11]

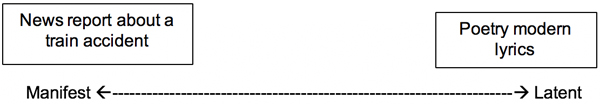

KRACAUER took on BERELSON's terms of manifest and latent content, however he placed the terms "manifest" and "latent" on a continuum (KRACAUER, 1952, p.634) as visualized in Figure 1:

Figure 1: The continuum of manifest and latent content [12]

At one end of the continuum, according to BERELSON, is the manifest content, for example the succinct newspaper report about a train accident. Readers will have no problems understanding such a newspaper article—they agree on the interpretations, the content is manifest, and can therefore also be coded with high reliability. At the other end of the continuum ("latent content") is, per BERELSON, modern poetry. To clarify, take the following example2):

"There must be some way out of here

Said the joker to the thief

There's too much confusion

I can't get no relief

Businessmen, they drink my wine

Plowmen dig my earth

None will level on the line

Nobody offered his word, hey!" [13]

What is the meaning of this text? A joker speaks to a thief, there must be a way out of here, there is too much confusion, businessmen drink my wine, farm workers dig up my earth, etc. Here, two readers will hardly come to identical interpretations of the content. According to BERELSON, content analysis can therefore only be practiced reliably for manifest content. [14]

KRACAUER (1952) argued, on the other hand, that this would put communication research in an awkward position; while its object was not the analysis and interpretation of modern poetry, it could also not be limited to the analysis of manifest content. In such research, manifest and latent content is always interwoven, and it is above all the latent content that is connected in a complex way with the research questions and research goals. According to KRACAUER, the overemphasis on quantification means that the analysis is less precise and blurred, and he cited the practice of mapping the characteristics and directions of communication on scales as an example. "In such instances coding is often performed on the basis of a graded scale which defines a continuum ranging from 'very favorable' to 'very unfavorable', from 'very optimistic' to 'very pessimistic', or the like" (p.631). [15]

This procedure of dividing complexity into elementary scales is inevitably simplifying and clouds the analysis: "They render arbitrary, for example, the real gap between 'very favorable' and 'favorable'; and they place under one uniform cover (e.g. 'favorable') a great variety of treatments whose differences are perhaps highly relevant to the purposes of the analysis" (p.632). [16]

Quantification and subsequent statistical analysis are carried out on a highly uncertain basis and relied upon only for this purpose, inevitably leading to inaccurate analyses. These statistical analyses carried out in the mathematical universe, the correlations and precise calculations of probabilities, may then be less accurate, more distorting, and less representative than the qualitative data on which they are based. "Quantitative analysis is in effect not as objective and reliable as they believe it to be" (p.637). Above all, if the material being analyzed has characteristics further in the direction of "latent content" on the continuum, a qualitative analysis is required where qualitative and quantitative analyses do not represent radically opposite approaches but can complement each other meaningfully. [17]

Anyone who knows the concepts of today's qualitative content analysis will probably be a little stumped by KRACAUER's example. Doesn't this form of analysis, which KRACAUER criticizes, closely resemble the one that Philipp MAYRING (2015 [1983]) presents as a particularly detailed example of content structuring analysis? In this case, MAYRING works with the scale values "high self-confidence," "medium self-confidence," "low self-confidence," and "self-confidence not accessible" (p.89, my translation). The variations proposed by KUCKARTZ (2018) and SCHREIER (2012) are similar. [18]

The approach is indeed similar to the kind of analysis that KRACAUER criticized and which prompted him to call for a qualitative content analysis. This is about translating text content into variables, which can be placed on ordinal, as well as nominal and interval scales. The variables are called categories here, but they have a functionally equivalent meaning. The qualitative data coded in this way is then statistically analyzed in the form of a "cases x categories" matrix. An example of such a matrix created by coding qualitative material is shown in Table 1. Category (variable) A is ordinally scaled (with the three levels "optimistic," "as well as," "pessimistic"), Category B is used to make only the dichotomous distinction between "present" and "non-existent," and Category C contains the frequency of a certain behavior and displays an interval scale level.

|

|

Category A |

Category B |

Category C |

|

Person 1 |

optimistic |

present |

3 |

|

Person 2 |

as well as |

non-existent |

5 |

|

Person 3 |

pessimistically |

present |

2 |

|

Person n |

... |

... |

... |

Table 1: Result of content analytical coding: "Cases x categories" matrix [19]

This form of analysis is quite legitimate and, in many cases, appropriate to the issue at hand. But there is also the option of analyzing the coded material qualitatively, because behind every cell of the matrix there are text passages—at least if the coding was done in such a way that segments of the data were assigned to a category or subcategory. The "cases x categories" matrix can also be presented in qualitative format, not with category characteristics in the cells, but with the underlying text passages. In a topic-oriented analysis, the coding process results in a structure of the qualitative data that can be represented in the form of such a matrix: the cases are displayed horizontally in the columns—these can be persons, families, institutions, etc. Vertically, the columns are subdivided into to the categories formed by the researchers, for example in Table 2 according to topics.

|

|

Theme A |

Theme B |

Theme C |

|

|

Person 1 |

Text passages from person 1 to topic A |

Text passages from person to topic B |

Text passages from person 1 on topic C |

|

|

Person 2 |

Text passages from person 2 to topic A |

Text passages from person 2 to topic B |

Text passages from person 2 on topic C |

|

|

Person 3 |

Text passages from person 3 to topic A |

Text passages from person 3 to topic B |

Text passages from person 3 on topic C |

|

Table 2: Result of content analytical coding: the "cases x categories" matrix with original text passages [20]

A qualitative content analysis of this matrix now requires you not to enter the world of mathematics and counting—or, rather, not only this world—but also to carry out the analysis in the qualitative realm. How can this be achieved? This is where codified methods are necessary. In my opinion, thematic summaries are a good place to start, i.e., by creating—for each cell of the matrix—a case-related thematic summary of all text passages available for that person on a specific topic. In other words, the further analysis is based on the code assignments of the researchers. [21]

This approach is fundamentally different from paraphrasing texts or text passages at the beginning of conducting a qualitative content analysis, because the thematic summary is not a summary of the raw texts but of the results of the content structuring coding process on a case-by-case basis. This means that a further condensed analysis level is inserted between the primary data and the categories. So, this is my first suggestion for going beyond the current state of qualitative content analysis, namely, to actually carry out a more strongly qualitative analysis, depending on the project and question at hand, possibly also in combination with a quantitative analysis of the categories. [22]

3. And Beyond 2: Call for a Supplementary Case Orientation

The second point on which, in my opinion, qualitative content analysis should be extended beyond the status quo concerns the fundamental direction of the analysis. KRACAUER had a qualitative content analysis in mind that was more holistic, i.e., the material is not only evaluated in a category-oriented way, in its individual parts, but also analyzed it in a case-oriented way. I come back to the matrix "cases x categories" of Table 2; but now in an extended form, which also contains the results of a case-oriented analysis (case summaries) and category-based analysis (e.g., thematic summaries).

|

|

Theme A |

Theme B |

Theme C |

|

|

|

Person 1 |

Text passages from person 1 to topic A |

Text passages from person 1 to topic B |

Text passages from person 1 on topic C |

→ Case summary for person 1 |

|

|

Person 2 |

Text passages from person 2 to topic A |

Text passages from person 2 to topic B |

Text passages from person 2 on topic C |

→ Case summary for person 2 |

|

|

Person 3 |

Text passages from person 3 to topic A |

Text passages from person 3 to topic B |

Text passages from person 3 on topic C |

→ Case summary for person 3 |

|

|

|

Category-based summary of |

|

|

|

|

|

|

↓ |

↓ |

↓ |

|

|

|

|

Theme A |

Theme B |

Theme C |

|

|

Table 3: Category-oriented and case-oriented analysis of the "cases x categories" matrix [23]

The usual perspective of qualitative content analysis is for the researchers to look vertically into the columns and make a summary analysis of the respective category and possibly its subcategories. This way, for example, the category of self-confidence is analyzed—in a qualitative way as a verbal summary and/or in a quantitative way as a frequency analysis of the categories and subcategories (MAYRING, 2015 [1983], p.89). This is necessarily a more atomistic view. You don't have to be a gestalt psychologist to find it useful to turn your gaze 90 degrees and look into the rows, i.e., to analyses in a case-oriented way. The case analysis is carried out in such a way that it is based only on the parts of the material coded with the analytical categories. It is therefore a case analysis on the basis of the material parts processed, interpreted and categorized from the perspective of the research question. With the help of advanced case analyses, we can group cases together due to their similarity into groups and clusters. In this way, for example, typologies can be formed, target groups determined, and similar patterns identified. [24]

With regard to such a case-oriented analysis, it is, of course, also necessary to reflect on how this analysis can be practiced in a methodically controlled manner. It can be performed qualitatively, i.e., only based on the text segments; no numbers are used and correlations between categories are described linguistically without using statistical operations. However, quantitative aspects can also be integrated, e.g., the frequency of categories and the correlation of categories can be calculated. My second proposal is therefore: let us broaden the perspective of category orientation to include a case-by-case view. [25]

4. And Beyond 3: Qualitative Content Analysis in the Context of the International Methods Discourse

In a one-on-one conversation during the break of a workshop on "mixed methods," a doctoral student asked me: "Is it really necessary to read English methods literature?" I was initially a little surprised by the directness of the question. However, this reluctance to engage with English literature as expressed in the question is by no means an isolated case. Time and again, when I ask in a preliminary survey before a methods workshop about the literature participants have read on the subject of "analytical methods," I find that no English literature is mentioned; and this happens in doctoral student colloquia, not just in courses with bachelor or master students. And yet, it is difficult to deny that the social sciences have long been internationalized and that the global language of science is English. So, it is obvious to ask: what is the status of qualitative content analysis in the international context? Is it well known? Is it popular? Is it used often? Or are there other methods of analyzing qualitative data on the international scale? [26]

The first perhaps somewhat surprising result of such research is that qualitative content analysis is relatively unknown in the relevant English methodological literature. In addition to the textbook by SCHREIER (2012), there are some pertinent publications—primarily in the fields of nursing science and public health (BENGTSSON, 2016; ELO et al., 2014; GRANEHEIM & LUNDMAN, 2004; HSIEH & SHANNON, 2005)—but in the handbooks (e.g., DENZIN & LINCOLN, 2018) and the literature giving an overview of (qualitative) methods (e.g., CRESWELL & POTH, 2018), qualitative content analysis is virtually ignored. This has both historical and contemporary reasons. KRACAUER's call for a qualitative content analysis, which was presented at the beginning of this article, was not widely discussed in American methodological publications of the 1950s and 1960s and did not establish the qualitative content analysis method. Both personal factors concerning the author's biography3) and structural factors in the development of social research at the time4) are responsible for this. The little attention that qualitative content analysis receives in today's English-language method literature also applies to other methods common in Germany, such as the documentary method (BOHNSACK, 2014). What are the reasons for this? An important reason might be the long lack of German-speaking authors in English literature, especially in textbook literature. The handbooks and dictionaries, e.g., the "Handbook of Qualitative Research" published by DENZIN and LINCOLN (2018), do not refer to qualitative content analysis, either. American colleagues of mine raised one not insignificant point, namely the association of content analysis with quantitative methods, which is founded in the history of content analysis (see above). A "qualitative content analysis" therefore appears to be either a conceptual contradiction, as contradictio in adjecto, or it is classified from the outset as a procedure for the quantitative analysis of qualitative data. [27]

When I was planning the English translation of my 2014 book on qualitative content analysis, my American colleagues strongly advised against entitling it "Qualitative Content Analysis." The title alone is associated with the risk of being classified in the wrong category. I then avoided the term "content analysis" and chose "Qualitative Text Analysis" as the title of the book and am very satisfied with the response to the book. It has since been translated into Japanese and Chinese. [28]

So, what other analysis methods for qualitative data are described in the English-language research literature? Firstly, there is a much stronger focus on research styles and approaches—and not on individual methods. One's own research is described as ethnographic research, field research, grounded theory-oriented research, narrative research, action research, social justice research, mixed methods research etc. and within these approaches analytical procedures are presented. The corresponding research reports, books and articles also contain chapters on the methods used to analyze the data—as in CRESWELL and PLANO CLARK (2018)—but it is rather unusual to label the methods used with certain scholars. If you take a closer look, you will often find forms of analysis that are similar to the content structuring content analysis, but are much more strongly qualitatively oriented (CRESWELL, 2016). [29]

There are also numerous methods textbooks in the narrower sense, such as "Qualitative Data Analysis: Practical Strategies" (BAZELEY, 2013), "Analyzing Qualitative Data: Systematic Approaches" (BERNARD, WUTICH & RYAN, 2017), "Qualitative Inquiry and Research Design" (CRESWELL & POTH, 2018), "Applied Thematic Analysis" (GUEST, MacQUEEN & NAMEY, 2012), "The Coding Manual for Qualitative Researchers" (SALDAÑA, 2015), "Interpreting Qualitative Data" (SILVERMAN, 2014), and other monographs. A relatively broad spectrum of analytical possibilities is usually discussed in these textbooks. The textbook by MILES, HUBERMAN and SALDAÑA (2013), almost 300 pages and providing a fascinating wealth of concrete suggestions for analysis, is a prototype. [30]

It must be said—and not without a certain amount of admiration—that many innovative and valuable suggestions are made in this literature as regards the possibilities of analysis, compared to which the current state of qualitative content analysis appears to be a relatively narrow and not especially nuanced procedure. This also applies to the topic of "codes and coding," where very sophisticated and detailed literature is available, while here in Germany "diffuse Begrifflichkeiten" [diffuse terms] (SCHREIER, 2016, n.p.) are used. [31]

For the future development of qualitative content analysis, it is therefore of great importance that it becomes more present on the international stage, i.e., that it is mentioned in the relevant methodological literature and in the manuals. Its chances are not bad, at least far better than ten years ago. It is also an invitation to those who write about the qualitative content analysis method to do so, whenever possible, in English. So, this is my third proposal of going beyond its current state: a greater orientation towards the international discourse itself and a stronger focus on introducing methodological ideas into the international discourse. [32]

5. Methodological Aspects of Qualitative Content Analysis

In the previous sections, I presented three possible extensions of qualitative content analysis. In the following section I will deal with another form of extension, namely a reflection on its methodological and epistemological foundations. This is expressed prototypically in two questions posed in the context of the conference "Qualitative Content Analysis – and Beyond?," both in the working groups and in the forum: firstly, the question of the "methodological positioning" of qualitative content analysis and, secondly, the question "How qualitative is qualitative content analysis in relation to the central requirements of openness and understanding of meaning in the research process?" [33]

As regards the first question: STAMANN et al. (2016, §6) already asked the question concerning the methodological positioning of qualitative content analysis, and criticized the lack of a foundation in a framework theory (see also SCHNEIDER, 2016). From my point of view, there is a misunderstanding of qualitative content analysis here. Qualitative content analysis is a method, it is not a methodology, nor is it an epistemology. It does not presuppose a particular approach to this world and its social phenomena and problems. Unlike FOUCAULT's discourse analysis (DIAZ-BONE, 2010) it is not based on a background theory from which it was developed as a specific method. The term "method" comes from the ancient Greek μέθοδος [methodos] and means "way to something." A method is a means of gaining knowledge, a planned process based on rules—similar to a gasoline engine, for example, which is a process for generating energy by combustion such that a Toyota Camry, for example, can be powered by it. Methods can be applied in very different contexts, so it is quite possible to apply qualitative content analysis in the context of a grounded theory study or in the context of discourse analysis. The question as to whether qualitative content analysis is "compatible" with certain research styles (as formulated by MEUSER (2011, p.90) cannot be answered with respect to qualitative content analysis itself, but only concerning the respective research approach. It is therefore incumbent, for example, on the proponents of reconstructive social research as per BOHNSACK (2014) or discourse analysis to formulate corresponding declarations of compatibility or incompatibility. [34]

As to the second question "How qualitative is the qualitative content analysis in relation to the central requirements of openness and understanding of meaning in the research process?," in this question it is implicitly assumed that there is a "qualitative continuum" in methods, i.e., that methods can be more or less qualitative. In fact, some representatives of certain strains of qualitative research have cultivated this view and see themselves as the "truly" qualitative ones, while deeming other directions of qualitative research to be only half-heartedly qualitative or even denying them the qualitative attribute altogether, since they use inadmissible "shortcut strategies" and do not devote enough time to "real" qualitative research—possibly due to the constraints placed on them by third-party funded projects and/or commissioning bodies. Attributing such values does not seem appropriate to me in the area of qualitative approaches, just as it doesn't in the area of quantitative approaches. It makes no sense to speak of a slight number or a somewhat mean value calculation—nor is a multiple regression more quantitative (i.e., better) than a discriminant analysis or an analysis of variance. Nor is it necessary to assign such a value to qualitative methods: the objective hermeneutics method is no more qualitative than phenomenological analysis or qualitative content analysis. A multiculturalism based on mutual respect should rather be cultivated here. [35]

As far as openness and understanding of meaning are concerned, these are undisputedly central characteristics of qualitative research. In this respect, the question of how openly qualitative content analysis is carried out as a method and what role the understanding of meaning plays in this context is very justified. As far as "openness" is concerned, it is necessary to explain exactly what is meant by "openness," which can be localized at different levels of the qualitative research process and by different actors. For the research participants, openness means being able to answer a question or a topic completely freely and openly. This means that, unlike in a standardized survey, no predefined answers are presented between which the research participants must choose, and which thus provide the framework for thinking. "Openness" is different at the level of the researchers: does openness here mean that researchers are not allowed to ask specific questions? That they in a sense have to wait for narrations from the research participants during a face-to-face interview after an initiating stimulus? Or does openness even mean that the researchers should approach the research object and the research participants like a tabula rasa? This would mean that they should go into the field without any prior knowledge, should not read any specialist literature and research reports beforehand, but should get involved in the research situation in an unbiased way and not be blinded by existing theories? Openness, as you can see at first glance, is a very broad field. Hence, the research process of a project must be explained as precisely as possible. In order to assess the openness of qualitative content analysis, the context of the whole project needs to be considered, in particular the category formation and the coding process. Qualitative content analysis is, I repeat, no style of research, no methodology, and certainly no paradigm according to which research is designed and research designs are conceived. It is an analysis method and, as such, can be used in many research contexts, disciplines and designs. It is used to analyze the material by means of categories; these can be defined in advance or formed directly from the material itself, where mixed forms are of course possible. In this respect, qualitative content analysis is open to a greater or lesser extent depending on the research approach chosen. The characteristic feature of qualitative content analysis is its high degree of flexibility; it can be used to work with a coding frame derived from theory as well as to develop categories based entirely on the material. [36]

The question of the understanding of meaning in the context of qualitative content analysis is of fundamental importance and we will therefore dig a little deeper here. The term "meaning" is highly charged; it is primarily a philosophical and theological category. Many readers will automatically think of the same fundamental questions, such as the question about the "meaning of life," for example. Is there a way to understand the meaning of life, and to understand it correctly? Philosophers have been worried about this question for thousands of years. Some have found a short answer, as Douglas ADAMS (1979) describes in his book "Hitchhiker's Guide to the Galaxy," where the answer "42" is produced after seven million years of computing time. The question "What is the meaning of life?" naturally, like other questions about meaning, is implicitly based on the premise that such a meaning exists at all. But not every linguistically correct statement is necessarily associated with a subjective meaning. Modern personal assistant software such as Apple's Siri, Cortana (Microsoft) or Alexa (Amazon) can formulate sentences in natural language that make sense linguistically but are subjectively meaningless. [37]

What's more, the term "meaning" can of course also be used in a variety of different senses itself. There is the sense of "meaning" as it is used in the aforementioned existential question, "What is the meaning of life?" Similar questions here would be "What is the purpose of life?" or what is life worth?" Moreover, according to the Merriam-Webster dictionary, "meaning" can also refer to 1. the thing that is conveyed especially by language (or by an action, for example), and 2. the thing a person intends to convey. [38]

With the above question about understanding meaning in the context of qualitative content analysis, we usually aim at understanding the meaning of a linguistic expression. But perhaps the second is also meant to understand a person's true intentions. It seems important to me to stress at this point that these are different perspectives. To formulate it clearly, qualitative content analysis was not developed to discern the latter; with it we do not aim to understand the "true" intentions or inner states of a person, which falls within the professional field of psychology or psychoanalysis/psychotherapy and cannot easily be practiced by non-psychologists. Our everyday life also shows that it is extremely difficult to understand other people "correctly" in this sense. Understanding meaning in the context of qualitative content analysis focuses on understanding the meanings and concepts associated with a linguistic expression. It may make sense to consider hermeneutics here. It can provide important rules for understanding; after all, it has long been concerned with the subject of understanding meaning and involves the role of prior knowledge, the meaning of contexts, and the relationship between the part and the whole (KUCKARTZ, 2018). The basic requirement for understanding meaning in the context of qualitative content analysis is to achieve agreement between the researchers (coders) with regard to meaning and thus the coding of the material. Explanations of the categories used in the analysis (e.g., in the coding manual or the code memos) also make it possible for the recipients of the research to comprehend this understanding. The content analysis work of the research team is therefore not about developing probable and unlikely readings, but about creating an intersubjective understanding and assigning qualitative data material to as precisely defined categories as possible—where these are certainly also able to be developed based on the material itself. [39]

6. Summary and Looking Ahead: Qualitative Content Analysis on the Way to Rigorous Analysis

In this article, I identified three areas where "beyond" seems attractive and useful.

I'm arguing for conducting a more strongly qualitative analysis in the phase after the coding process—which may take place in several cycles. Frequency analyses of the categories are not sufficient and a classification of the qualitative data on scales is, as KRACAUER already argued, often far too rough. This requires a more specifically qualitative analysis; an analysis that not only based on numbers, but that is also concerned with the diversity and also the ambiguity of the data. Qualitative content analysis should therefore become more strongly qualitative and interpretive, with limits placed in regard to interpretation where no intersubjective agreement of interpretations can be achieved in the research team. In this respect, qualitative content analysis is a procedure into which the principles of hermeneutics have been incorporated and used in its practice, but it is not a hermeneutic procedure focused on an extensive preoccupation with meanings and different readings.

I suggested that content analysis should not be focused solely on the categories. Qualitative content analysis researchers should develop a dual perspective and analyze the data in both categories and cases. Case orientation can be very valuable because, in our culture, storytelling is of great importance and the results of the analysis can be better communicated by means of in-depth case analyses. A case-oriented analysis also does more justice to the basic principles of qualitative research approaches, because the consideration of the subjective dimension—of authentic voices of the living world, so to speak—is precisely what distinguishes qualitative research. If, for example, public health research and nursing science research call for the gold standard of randomized controlled trials to be extended to include qualitative research (PLANO CLARK et al., 2013) then it is obvious that it should be research that focuses precisely on the subjective dimension. A purely category-based evaluation of qualitative interviews conducted will often fall short of this requirement in this context.

This point is probably of great importance from the point of view of professional policy: researchers using qualitative content analysis should be more internationally oriented, should not isolate the method to a small German-speaking bubble, but should pitch in amongst the many global proposals for a modern analysis of qualitative data. Employing such a modern qualitative data analysis, researchers can make use of the many innovative possibilities of computer-aided analysis. These range from the inclusion of multimedia data via synchronous access to audio/video recordings and transcriptions, to visualizations, concept maps, mixed methods analyses, geo-links, and much more (BAZELEY & JACKSON, 2013; FRIESE, 2014; KUCKARTZ, 2010; RÄDIKER & KUCKARTZ, 2019). This requires further reflection on how to integrate these modern techniques—and many concrete suggestions can be found in the English methodological literature. [40]

The last sentence in KRACAUER's essay of 1952 was: "One final suggestion: a codification of the main techniques used in qualitative analysis would be desirable" (p.642). This is the proposal of methodological rigor, the way to a rigorous analysis in the sense of CRESWELL and others. I deliberately use the term "methodological rigor" here to emphasize that it should involve clearly explicated analytical steps, i.e., avoiding the thicket of procedures and concepts that SCHREIER (2014) rightly criticized, for instance. Instead, we should aim for transparency and clear information about how one came to one's inferences, how exactly the coding and analysis process took place, such as the number of times the material was analyzed. In short, it is about the analysis process and how it was conducted during the project. Ultimately, this methodological rigor is also necessary to assess the quality of a study that uses qualitative content analysis, whether in a purely qualitative or a mixed methods project. However, methodological rigor should not be misunderstood in such a way that the same quality criteria should apply as in quantitative research; instead, standards should be developed that are appropriate to the logic of the research process of qualitative content analyses. Necessarily, we thus need to discuss the standards and quality criteria of qualitative research; a broad field beyond qualitative content analysis in its narrower sense. Thus, the question of which criteria are to be defined to reach an agreement between several coders cannot be answered in such a way that coefficients developed for a completely different type of analysis within the framework of a paradigm of measurement and quantitative analysis can be adopted one-to-one. [41]

Even the transferability of the term "reliability" is questionable, since this term originates from measurement theory and qualitative research does not understand itself merely as measurement. So why should we adopt measurement accuracy criteria in qualitative research and, for example, calculate coefficients such as Kappa or KRIPPENDORFF's Alpha (KRIPPENDORFF, 2012) as part of our research? Those who use such coefficients of agreement should visualize the logic of these coefficients, the hidden curriculum, so to speak. The formula for Kappa is as follows:

p0 is the measured agreement value of the two raters and pc is the randomly expected agreement. The decisive factor for the agreement measurement is therefore the consideration that

there is a random probability for the agreement of coders for given coding units and a given coding frame. [42]

Here is an example from the field of quantitative content analysis: you have a predefined text section (coding unit) and ten disjunct codes, of which only one can be assigned at a time. The probability of a random assignment of a code is then p=.10, i.e., 10%. If you have only five codes, the probability of random assignment of a certain code would be 20%. However, this scenario does not correspond at all to the logic of qualitative content analysis, where the material is analyzed without a pre-determination of coding units, and where statements or meaning units are assigned to codes or codes are (newly) developed based on the material. [43]

Let's take a rather typical case where we are working with ten main categories that have an average of eight subcategories, that is, with a total of 80 codes. The probability—when a text is coded by two independent coders—of the same subcategory being randomly assigned to a predefined segment is extremely low (1.25%). Therefore, coefficients oriented towards the compensation of random correspondence are questionable in the usual coding process of qualitative content analysis. A further problem is that the size of the text segments obviously plays a role, because the smaller the coded segment is, the less likely it is that two code assignment ends coincide. After taking all circumstances into account, KUCKARTZ and RÄDIKER (2019) have come to the conclusion that the use of Kappa and other reliability coefficients of this type should be reconsidered within the logic of qualitative content analysis, as these coefficients are in most cases inappropriate. It is almost as if you wanted to use an alcohol breathalyzer to measure the air pressure in a bicycle tire. Yet, the development of adequate and generally accepted instruments for assessing the quality of coding in the context of qualitative content analysis remains a desideratum for the time being. Here, it is advisable to follow up the general discussion on quality criteria in qualitative social research; criteria must be found which have an appropriate relationship to qualitative content analysis. [44]

Methodical rigor first and foremost means transparency and explanation, such as answers to questions like: How was the coding frame developed? How are the categories and subcategories defined? How was the agreement of the coders ensured? Methodical rigor also means thinking about the individual steps of the analysis—especially the qualitative ones—and revealing these evaluation steps and their justifications. Qualitative content analysis is more than categorizing the material and then simply counting the coding frequencies. For example, what role theory construction played in the analysis process and how it was implemented in practice should be explained (RUST, 2018). [45]

The crucial questions are: "What happens after the coding process?," "What are the details of the analysis phase that follows the coding process?," "What are the possibilities for further analyses, especially complex analyses?" and last but not least, "What further possibilities for qualitative analysis are there?" Progressing from here and developing methodological rigor is likely the central task facing qualitative content analysis in its further development. [46]

1) http://www.springerlink.com [Accessed: August 15, 2019]. <back>

2) Lyrics by Bob DYLAN, Song "All along the watchtower." <back>

3) On a personal level, it is important to note that KRACAUER, who as a Jewish social scientist was forced to emigrate to America from Nazi Germany, had been a member of a scientific culture other than the American empirical one. Like many emigrated social scientists, KRACAUER was more oriented towards social philosophy and the humanities. His essay on qualitative content analysis was published in the well-known journal Public Opinion Quarterly in a special issue on communication research, edited by Leo LÖWENTHAL. It contained contributions by many scientists from Germany, which as a country was more politically left wing and steeped in a more philosophically oriented academic tradition. Furthermore, as his biographer Jörg SPÄTER (2016, pp.497-511) notes, KRACAUER was essentially a free agent, i.e. he did not have a professorship, had no private enterprise funding his work, did not form a school like the Frankfurt colleagues associated with ADORNO and HORKHEIMER, but was rather a classical intellectual with worldwide connections. KRACAUER's main interest was in the communication medium of film; his book "From Caligari to Hitler: A Psychological History of German Film" (KRACAUER, 2004 [1947]) is a classic in film sociology and his theory of film (KRACAUER & HANSEN, 1997) is still frequently quoted today. <back>

4) At the structural level, the strong development of social research toward quantification, under the dominance of behaviorism after the Second World War, certainly played a significant role. At the same time, approaches combining qualitative and quantitative methods, as proposed by LAZARSFELD (1972) for example, were strictly empirical-pragmatic and not oriented toward social-philosophical science. This aspect of the history of social sciences can be mentioned here only in passing; for further details see SPÄTER (2016). KRACAUER died in 1966, and it took twenty years for his essay on qualitative content analysis to be published in a German translation. MAYRING, who introduced the term qualitative content analysis to Germany in his book first published in 1983, referred to the translated version of 1972 and not to the original article of 1952. <back>

Adams, Douglas (1979). The hitchhiker’s guide to the galaxy. London: Pan Books.

Baur, Nina & Blasius, Jörg (Eds.) (2014). Handbuch Methoden der empirischen Sozialforschung. Wiesbaden: Springer VS.

Bazeley, Patricia (2013). Qualitative data analysis: Practical strategies. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Bazeley, Patricia & Jackson, Kristi (2013). Qualitative data analysis with NVivo. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Bengtsson, Mariette (2016). How to plan and perform a qualitative study using content analysis. NursingPlus Open, 2, 8-14.

Berelson, Bernard (1952). Content analysis in communication research. Glencoe: Free Press.

Bernard, H. Russell; Wutich, Amber & Ryan, Gery Wayne (2017). Analyzing qualitative data: Systematic approaches (2nd ed.). Los Angeles, CA: Sage.

Bohnsack, Ralf (2014). Rekonstruktive Sozialforschung: Einführung in qualitative Methoden (9th rev. and exp. ed.). Opladen: Barbara Budrich.

Creswell, John W. (2016). 30 essential skills for the qualitative researcher. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Creswell, John W. & Plano Clark, Vicki L. (2018). Designing and conducting mixed methods research (3rd ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Creswell, John W. & Poth, Cheryl N. (2018). Qualitative inquiry and research design: Choosing among five approaches (4th ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Denzin, Norman K. & Lincoln, Yvonna S. (Eds.) (2018). The Sage handbook of qualitative research (5th ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Diaz-Bone, Rainer (2010). Kulturwelt, Diskurs und Lebensstil: eine diskurstheoretische Erweiterung der Bourdieuschen Distinktionstheorie (2nd exp. ed.). Wiesbaden: VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften.

Elo, Satu; Kääriäinen, Maria; Kanste, Outi; Pölkki, Tarja; Utriainen, Kati & Kyngäs, Helvi (2014). Qualitative content analysis: A focus on trustworthiness. SAGE Open, 4(1), https://doi.org/10.1177%2F2158244014522633 [Accessed: June 4, 2019].

Friese, Susanne (2014). Qualitative data analysis with ATLAS.ti (2nd ed.). Los Angeles, CA: Sage.

Graneheim, Ulla Hällgren & Lundman, Beril (2004). Qualitative content analysis in nursing research: Concepts, procedures and measures to achieve trustworthiness. Nurse Education Today, 24(2), 105-112.

Guest, Greg; MacQueen, Kathleen M. & Namey, Emily E. (2012). Applied thematic analysis. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Hsieh, Hsiu-Fang & Shannon, Sarah E. (2005). Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qualitative Health Research, 15(9), 1277-1288.

Janowitz, Morris (1968). Harold D. Lasswell's contribution to content analysis. Public Opinion Quarterly, 32(4), 646-653.

Janssen, Markus; Stamann, Christoph; Krug, Yvonne & Negele, Christina (2017). Tagungsbericht: Qualitative Inhaltsanalyse – and beyond?. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung / Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 18(2), Art. 7, http://dx.doi.org/10.17169/fqs-18.2.2812 [Accessed: June 4, 2019].

Kittsteiner, Heinz D. (2011). Das Komma von SANS, SOUCI: ein Forschungsbericht mit Fußnoten (4th ed.). Heidelberg: Manutius.

Kracauer, Siegfried (1952). The challenge of qualitative content analysis. Public Opinion Quarterly, 16, 631-642.

Kracauer, Siegfried (1971 [1930]). Die Angestellten. Aus dem neuesten Deutschland. Frankfurt/M.: Suhrkamp.

Kracauer, Siegfried & Hansen, Miriam (1997). Theory of film: The redemption of physical reality. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Kracauer, Siegfried (2004 [1947]). From Caligari to Hitler: A psychological history of the German film (edited by L. Quaresima; rev. and exp. ed). Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Krippendorff, Klaus H. (2012). Content analysis: An introduction to its methodology (3rd ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Kuckartz, Udo (2010). Einführung in die Computergestützte Analyse qualitativer Daten (3rd ed.). Wiesbaden: VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften.

Kuckartz, Udo (2014). Qualitative text analysis: A guide to methods, practice & using software. Los Angeles, CA: Sage.

Kuckartz, Udo (2018). Qualitative Inhaltsanalyse: Methoden, Praxis, Computerunterstützung (4th ed.). Weinheim: Beltz Juventa.

Kuckartz, Udo & Rädiker, Stefan (2019). Analyzing qualitative data with MAXQDA. Text, audio, and video. Cham: Springer Nature.

Lazarsfeld, Paul F. (1972). Qualitative analysis; historical and critical essays. Boston, MA: Allyn and Bacon.

Mayring, Philipp (2015 [1983]). Qualitative Inhaltsanalyse: Grundlagen und Techniken (12th ed.). Weinheim: Beltz.

Meuser, Michael (2011). Inhaltsanalyse. In Ralf Bohnsack, Winfried Marotzki, & Michael Meuser (Eds.), Hauptbegriffe Qualitativer Sozialforschung (pp.89-91). Opladen: Barbara Budrich.

Miles, Matthew B.; Huberman, A. Michael & Saldaña, Johnny (2013). Qualitative data analysis: A methods sourcebook (3rd ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Plano Clark, Vicky L.; Schumacher, Karen; West, Claudia; Edrington, Janet; Dunn, Laura B.; Harzstark, Andrea; Melisko, Michelle; Rabow, Michael W.; Swift, Patrick S. & Miaskowski, Christine (2013). Practices for embedding an interpretive qualitative approach within a randomized clinical trial. Journal of Mixed Methods Research, 7(3), 219-242.

Rädiker, Stefan & Kuckartz, Udo (2019). Analyse qualitativer Daten mit MAXQDA: Text, Audio und Video. Wiesbaden: Springer VS.

Rust, Ina (2018). Theoriegenerierung als explizite Phase in der qualitativen Inhaltsanalyse. Auf dem Weg zur Einlösung eines zentralen Versprechens der qualitativen Sozialforschung. Working paper, Leibniz Universität Hannover, http://t1p.de/Theoriegenerierende-Inhaltsanalyse [Accessed: June 4, 2019].

Saldaña, Johnny (2015). The coding manual for qualitative researchers (3rd ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Schneider, Werner (2016). Was ist der Inhalt eines Textes? Anmerkungen zur Praxis qualitativer Inhaltsanalyse aus wissenssoziologisch-diskursanalytischer Perspektive. Presentation, Conference "Qualitative Inhaltsanalyse – and beyond", Oktober 5, 2016, Weingarten, Germany.

Schreier, Margrit (2012). Qualitative content analysis in practice. London: Sage.

Schreier, Margrit (2014). Varianten qualitativer Inhaltsanalyse: ein Wegweiser im Dickicht der Begrifflichkeiten. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung / Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 15(1), Art. 18, http://dx.doi.org/10.17169/fqs-15.1.2043 [Accessed: June 4, 2019].

Schreier, Margrit (2016). Kategorien – Codes –Kodieren. Versuch einer Annäherung an diffuse Begrifflichkeiten. Presentation, Conference "Qualitative Inhaltsanalyse – and beyond", Oktober 5, 2016, Weingarten, Germany.

Silverman, David (2014). Interpreting qualitative data (5th ed.). London: Sage.

Später, Jörg (2016). Siegfried Kracauer: eine Biographie. Berlin: Suhrkamp.

Stamann, Christoph; Janssen, Markus & Schreier, Margrit (2016). Qualitative Inhaltsanalyse – Versuch einer Begriffsbestimmung und Systematisierung. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung / Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 17(3), Art. 16, http://dx.doi.org/10.17169/fqs-17.3.2581 [Accessed: June 4, 2019].

Udo KUCKARTZ is a social scientist and professor emeritus for educational research and methods of social research at the Philipps University of Marburg, Germany. The methodological focuses of his work include mixed methods, qualitative content analysis and computer-aided methods of qualitative content analysis. He has written numerous monographs and scientific articles in journals and handbooks, including the books "Qualitative Text Analysis: A Guide to Methods, Practice & Using Software," "Mixed Methods," and "Analyzing Qualitative Data with MAXQDA. Text, Audio & Video." His book "Qualitative Text Analysis" has been translated into Chinese and Japanese.

Contact:

Prof. em. Dr. Udo Kuckartz

Philipps University Marburg

Department of Education

Bunsenstr. 3

35027 Marburg, Germany

Tel.: +49 30 83202400

E-mail: kuckartz@uni-marburg.de

Kuckartz, Udo (2019). Qualitative Content Analysis: From Kracauer's Beginnings to Today's Challenges [46 paragraphs]. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung / Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 20(3), Art. 12, http://dx.doi.org/10.17169/fqs-20.3.3370.