Volume 21, No. 2, Art. 25 – May 2020

Anchoring Belonging Through Material Practices in Participatory Arts-Based Research

Kaisa Hiltunen, Nina Sääskilahti, Antti Vallius, Sari Pöyhönen, Saara Jäntti & Tuija Saresma

Abstract: How do people understand belonging and what kinds of stances toward belonging do they take? What kind of knowledge or ways of knowing (EISNER, 2008) does artistic practice yield about belonging? We ask these questions in this article, which is based on the research project Crossing Borders, in which we used participatory arts-based methods to study belonging. We invited participants to explore the notion of belonging in three parallel workshops drawing on different art forms, film, writing and visual arts. The goal of the workshops was for each participant to produce an artwork that deals with belonging.

In the article, we identify four stances that the participants expressed toward the concept of belonging and explore the ways in which their ideas were manifested in the artworks. We analyze the workshop discussions, the participants' interviews and the artworks, and demonstrate on both the conceptual and material level that artistic practice can provide extremely nuanced and situated knowledge, or ways of knowing, about belonging. We argue that the artworks anchor the ever-shifting stances into material forms and expressions. Artistic practice is thus one way of defining and contextualizing the fluid concept of belonging.

Key words: belonging; arts-based research; artistic practice; participatory research; collaboration; stance

Table of Contents

1. Introduction

2. Research on Art and Belonging

2.1 Previous research

2.2 Our approach

3. Researcher-Initiated Project With Participatory Methods

3.1 Objectives

3.2 Workshops

4. Stances of Belonging

4.1 Positive belonging

4.2 Searching for belonging

4.3 Struggling to belong

4.4 Skepticism toward belonging

5. Concluding Remarks

How do people understand and define belonging? What kinds of stances do people take in relation to the notion of belonging, and what kinds of attitudes does it evoke in them? Can art help people express their experiences of belonging and non-belonging and contest existing meanings of belonging? These are questions that we pose in a multi-disciplinary research project, Crossing Borders, which brings together researchers from the arts, cultural studies, social sciences and applied linguistics. [1]

In the project, we approach the concept of belonging through the material practices of art-making. In 2018, we researchers invited people to explore this notion with us in three parallel workshops, each one drawing on a different art form: film, writing, and visual arts. These workshops, which we consider the methodological contact zones (ESIN, 2017; PRATT, 2008) of this research project, were our main working method. In each one, the goal was for each participant to produce an artwork that deals with belonging. We organized the workshops in collaboration with the multicultural center Gloria and Jyväskylä Art Museum, Finland. Altogether 23 people from various backgrounds took part in the workshops and produced 31 artworks: nine short films, five sound works, eleven paintings, four installations and two sculptures. The artworks were presented in public events and in an exhibition at a local art gallery. [2]

In this article, we identify and discuss some of the many definitions, interpretations and stances that the participants expressed toward the concept of belonging in the three workshops, and the ways in which these ideas manifested themselves in the final artworks. We also discuss the types of knowledge artistic practice can yield about belonging, and how this knowledge contributes to research on art and belonging. We start by contextualizing the project and elaborating its aims against the background of earlier projects that have explored the connections between art and belonging (Section 2). Next, we introduce the workshops (Section 3). That is followed by a discussion of the negotiations and meanings of belonging that emerged in the workshops, and how those meanings were manifested in the artworks. We start each sub-section by focusing on the conceptual level, the thoughts and ideas that the participants expressed in the discussions and in the individual interviews. We use the term stance to describe the positions or perspectives toward belonging that the participants took. Next, in each sub-section, we take a closer look at how these stances were converted into artistic expression. Here the focus shifts to the art-making process and the artworks. Through five examples we illustrate the different ways in which the participants approached and expressed belonging in their works (Section 4). Finally, we sum up the discussion (Section 5). The images in the article are primarily visual field notes of ethnographic research, which take into account research ethics, such as some participants' wishes not to be identified from the photographs. Their purpose is not, therefore, to serve as aesthetic illustrations of the text, but as examples of research documentation. Our aim, and challenge, in the article is to identify the specific role of art in these negotiations of belonging. Following EISNER (2008), we ask what forms artistic knowledge, or knowing, about belonging takes. [3]

2. Research on Art and Belonging

Previous researchers exploring belonging have typically focused on social networks and relations among different groups, such as migrants and refugees, sexual minorities, disabled people and children, that have been defined as vulnerable and/or marginalized (LÄHDESMÄKI et al. 2016; ROUVOET, EIJBERTS & GHORASHI, 2017; WERNERSJÖ, 2015). The desired goal of such research has tended to be an increased sense of belonging (LÄHDESMÄKI et al., 2014, 2016). In our study we challenge the assumption of belonging only as a desirable state and point to the fact that for some people, non-belonging or an outsider position can be even positively liberating, and voluntarily adopted. Overall, our aim is therefore to widen the scope of research on belonging. [4]

Arts-based participatory methods have been used in several studies of belonging, especially in migration settings (e.g., CUTCHER, 2015; KORJONEN-KUUSIPURO, KUUSISTO & TUOMINEN, 2019; VACCHELLI, 2017). In Finland, too, arts-based participatory methods have been used in some earlier projects to study belonging. In a project with Somalian youth in Helsinki, several forms of expression were employed, among them documentary videos, a radio program, photography exhibitions and written stories, as a participatory method to explore the sense of belonging among young people who had experienced othering and exclusion (OIKARINEN-JABAI, 2017a; 2017b). In the research project Young Muslims and Resilience, the focus was on the lives of young Muslim women and men in Finland and how their sense of belonging was expressed through visual arts, writing, installations and short films (OIKARINEN-JABAI, 2019). In the THEATRE project, applied theater was used in the context of social-psychiatric rehabilitation to study the meanings that mental health care service users and people living in supported housing facilities gave to home, and what kinds of spaces of belonging and attachment the theater-making process could create for the participants (JÄNTTI & LOISA, 2018; JÄNTTI et al., 2018). The findings of the project exemplify how the sense of belonging grows and shifts in time. In Jag bor i Oravais [I live in Oravais] project (PÖYHÖNEN, KOKKONEN, TARNANEN & LAPPALAINEN, 2020), collaborative photography was used to explore lived experiences and the sense of belonging of young unaccompanied minors during their asylum process in a Swedish-dominated rural area of Finland. [5]

However, a closer analysis is still needed of how the sense of belonging is expressed in artworks produced in these kinds of projects, and how participants' thoughts about belonging are transformed into artworks during the creative process. One of our major aims in our project is to study the role of arts as a practice. [6]

In qualitative research, studies on belonging have been focused mainly on the linguistic resources used in the construction of belonging. As a result, the typical method has been the biographical-narrative interview (e.g., BALLENTHIEN & BÜCHING, 2009; CHAITIN, LINSTROTH & HILLER, 2009). The recent turn away from textuality and discursivity has meant an increased interest in, for example, material practices in the explorations of belonging (e.g., ESIN, 2017; ROOS, STOCKIE KOLOBE & KEATING, 2014). In addition, there is a growing amount of research, which understands language not just textual or discursive, but taking into account the whole semiosis, including material aspects (e.g., BRADLEY, MOORE, SIMPSON & ATKINSON, 2018). [7]

In our understanding of belonging, we rely on the distinction made by YUVAL-DAVIS (2010) between belonging and the politics of belonging. According to her, belonging refers to an emotional or ontological sense of attachment or of being at home. Belonging is articulated or politicized only when it is questioned or threatened. When people start to speak for and advocate belonging, it becomes the politics of belonging. The politics of belonging thus refers to political projects that are concerned with building societies and monitoring their borders. [8]

The concept of belonging is fluid and flexible, situated and socially constructed. It therefore needs to be defined anew in each context (LÄHDESMÄKI et al., 2016). This is also why we do not predefine the concept of belonging; rather, we are interested in the participants' own definitions, ideas and experiences. Nor do we have the explicitly emancipatory aim of strengthening participants' sense of belonging. [9]

We combine analysis of the participants' stances toward belonging with their expression in the final products of the workshops. In our previous research we have explored the multiple ways in which art, for example literature, films, theater and visual arts, can be used to represent, produce and challenge notions of belonging and the politics of belonging (HILTUNEN & SÄÄSKILAHTI, 2019; LEHTONEN & PÖYHÖNEN, 2019; SARESMA & JÄNTTI, 2014). Art can help us empathize and identify with others and it can help us in our own identity work. Art can also prevent belonging, not only through its content but also through formal strategies (HILTUNEN, 2019a; HILTUNEN et al., 2019). This is similar to the way in which the ideology of monolingualism may lead to the exclusion from literary circles of authors who use other than the dominant languages (LÖYTTY, 2017; PÖYHÖNEN et al., 2020; SARESMA, 2019). [10]

In our study, visual, sonic and textual approaches are used to enable multimodality and multi-sensoriality. We adopt a materialist viewpoint in which, following ST. PIERRE (2013), language is not dismissed but instead, language and materiality are thought to be outside of representational logic. This means that "the material is always already completely imbricated with the linguistic and discursive" (p.650). [11]

3. Researcher-Initiated Project With Participatory Methods

In the Crossing Borders project we use participatory arts-based methods and the project is researcher-initiated. We as researchers designed the project, devised the research questions and chose the methods, including the three types of collaborative workshops described here. Our research is thus not community-based, as it does not stem from the needs of any specific group of people (BELL & PAHL, 2018). Instead, it is we researchers who invite people to participate. We are also responsible for conducting most of the analysis, but there are opportunities for participants to contribute by writing blogposts and through social media, as well as by commenting on the researchers' output. [12]

In the participatory arts-based workshops, practitioners, researchers and artists worked with the participants who had been recruited, co-creating knowledge. Our way of conducting arts-based research comes close to other collaborative practices, of Jessica BRADLEY's and her colleagues' work (2018) and Anna Catherine HICKEY-MOODY's (2018) arts-based research, for example. In arts-based workshops, HICKEY-MOODY examined ideas of community, belonging, meaning, love and faith together with participants and through art-making practices. She describes aptly such research as a project of working with art, and as art of being and doing together. [13]

The objective of the Crossing Borders project is to explore by various means how recently-arrived migrants and long-term residents perform and narrate belonging through the arts, and how these performances and narratives are embedded in wider cultural and political contexts and social structures. Two of the workshops, the video workshop and the writing workshop, were therefore open to anyone living in the city of Jyväskylä at the time. Participants for these workshops were recruited through various social media groups and by advertising on local notice boards. In order to recruit participants with migration backgrounds, we advertised the workshops in the local multicultural center Gloria and on particular social media groups, such as Foreigners in Jyväskylä. About half of the participants, including, for example, the students, were living in the city of Jyväskylä temporarily. The third workshop was designed exclusively for professional visual and sound artists living in the Jyväskylä region. The invited artists worked with different art-making methods and techniques and had already found their own ways of expressing themselves through the medium of art. We hoped that they would reflect on their use of artistic strategies and provide art-specific knowledge. [14]

Although we sought to engage migrants, we do not perceive them as inherently vulnerable, and participation was not restricted only to groups that have been identified in previous research as "vulnerable" (LÄHDESMÄKI et al., 2014, p.91). However, certain vulnerabilities emerged during the relatively long process, and the workshops showed that vulnerability is situated and changing over time.1) We strove to bring together people from various backgrounds to discuss the notion of belonging. Following ESIN (2017), we understand the workshop environment as a methodological space that encompasses both the immediate surroundings and extended physical and social space (here in Finland and there in the participants' earlier countries of residence), and that is where the participants negotiated belonging and constructed their artworks.

Figure 1: Invitation to the "Tales of Belonging" video workshop [15]

The three workshops all took place in Jyväskylä during the first four months of 2018, and lasted approximately three to four months. In the research project we collaborated with two local institutions, the multicultural center Gloria and Jyväskylä Art Museum, which provided working space for the workshops. Gloria organizes multicultural and multilingual activities in the city. It is a welcoming meeting-place for recently arrived migrants and local residents. The involvement of the multicultural center encouraged migrants to participate and thus strengthened the aspect of migration in the project. Representatives of the multicultural center and the Art Museum also took part in the planning of the workshops. [16]

In the workshops, we researchers collaborated with practitioners from different fields of art and different areas of expertise. We worked as pairs or teams, planning and supervising the workshops together. The workshops were all different, but we agreed that they should all have certain common elements. The aim of all three workshops was that each participant should produce an artwork. The workshops consisted of discussions and various group and individual exercises, the aim of which was to activate the creative processes and support the participants in their art projects. Everyone, including the researchers, our partners and research assistants, took part in the discussions, sharing their ideas and thoughts. Plenty of time was reserved for the planning and creation of the artworks. The participants were encouraged to collaborate and help each other out in all phases of the process. Art-making was an integral part of the project rather than just one small element in a project using various methods (VAN DER VAART, VAN HOVEN & HUIGEN, 2018). [17]

Other common elements were a group discussion at the beginning of the workshop on meaningful objects and what makes them meaningful, and an interview with each participant toward the end of the workshop. Each participant was asked to bring along to the discussion an object that had personal significance for them. This object (e.g., a passport, a key-ring, a sea shell, etc.) was used as a starting point for a discussion about belonging, and it helped the participants to get to know each other. In the individual interviews, we asked the participants to look back and reflect on possible connections between the workshop, art-making practices and their experiences of belonging and non-belonging. Halfway through the workshops we gave the participants from all three workshops the opportunity to get to know each other and present their ideas for their artwork. Finally, in February 2019, the artworks of 21 of the participants in the three workshops were exhibited at the Jyväskylä Art Museum's Gallery Ratamo (see the exhibition catalogue, VALLIUS et al., 2019). [18]

A researcher and a video journalist supervised the video workshop, which had nine participants. The aim was that each participant should make a short film lasting approximately ten minutes. Given the limited period, all of the participants decided to make some type of non-fiction film. We discussed the different genres of documentary, but this was more for the sake of information and inspiration than as a guideline. About half of the participants had previous experience of filmmaking; only two had no experience at all. The workshop consisted of fifteen three-hour meetings, most of which took place in the multicultural center Gloria, which was already familiar to many of the participants. [19]

In the workshop we dove into the theme of belonging with a mind map exercise, which revealed the breadth of the topic. We went on to discussions about belonging, touching topics such as belonging to a place, emotions related to experiences of belonging, and voluntary and forced mobility. The participants approached belonging from very different angles, and it was clear that opinions differed on many issues. People spoke openly, drawing on their personal experiences and knowledge. We also watched and analyzed short films about loosely related topics. [20]

The actual filmmaking started with ideation, which included a lot of idea sharing and group exercises about researching for a film, for example. Ideation continued with summarizing the idea of the film that each one was going to make, and scriptwriting. Next, the participants practiced filming in groups and shot material for their films. Editing was the final and most time-consuming phase, taking about five weeks. Finally, the films were screened for public viewing on two evenings. [21]

Seven of the participants finished their short films, the styles of which range from an experimental short film to a documentary that combines observational and participatory modes. The films' themes include the bodily sense of belonging, belonging through music, olfactory memories of home, belonging by learning to cycle, defending a doctoral thesis in order to belong to academia, adaptation to a new culture, and the feeling of non-belonging (HILTUNEN, 2019b).

Figure 2: Ideation in the video workshop [22]

The writing workshop, "Words of Belonging," was led by three people, a researcher, a poet and a teacher of creative writing. The starting point in the workshop was crossing the boundaries between different art forms and genres. Instead of focusing merely on textuality, we encouraged participants to combine visual and auditory elements in their creative works. Sound was chosen as one expressive tool that we explored, and listening became a working method in the workshop. We thus paid attention to paralinguistic features of language and listened to the rhythms, tones and silences in each other's languages. Some of the participants were already engaged with the art form closest to them: either creative writing, painting or filming. Both the workshop design and the participants' differing interests led to the creation of multimodal creative works during the workshop. [23]

In the weekly meetings, we wrote about belonging and non-belonging, listened to readings of the texts produced, and shared our experiences and thoughts. The topics we touched upon included mobility, displacement, freedom, language barriers, taking the position of an outsider, voluntary non-belonging, difficult memories, family and other social ties, and art-making as a way of belonging. Writing assignments were used to initiate the creative processes. One such assignment was to write about experiences permeated with feelings of either belonging or non-belonging. In another meeting, the participants brought along a picture or a work of art that in one way or another inspired or involved meaningful aspects of belonging for them. [24]

The group worked dialogically and collaboratively, sharing ideas, feedback and thoughts, and helping each other to construct the final products. Help was provided in visualizing, filming and translating. As a result, short stories, visual and textual poems, autobiographical writings, sound and video poems, a filmic short story, a politically engaged video, paintings and sculptures were created. The meanings of belonging were further explored in the public events organized by the workshop. Two literary nights featuring the workshop participants' live readings and the premiers of the sound and video poems were organized as part of the workshop. The audience also had the chance to share their ideas on belonging. These events based on bodily presence enabled the participants to share experiences on a personal level.

Figure 3: Individual work in the writing workshop [25]

Seven local professional artists or people who had taken part in art exhibitions answered the call to take part in the visual arts workshop. The participants came from various cultural backgrounds; four of them had migrated to Finland. The artistic repertoire of the group included painting, drawing, graphics, installation art, photography, sound art and audiovisual expression. [26]

The workshop was designed by the researchers together with a museum lecturer, and three meetings were held at the Jyväskylä Art Museum. We had only three meetings because there was no need to learn the basics of artistic expression. Besides, the artists were used to working independently in their own workspaces with their own materials and tools, and that is where they finished the artworks they had started to plan in the workshop. [27]

The aim of the first meeting was to examine the participants' personal feelings of belonging. In addition to the meaningful object discussion, we approached the topic with a collage technique, using cuttings from magazines. In the second meeting we discussed belonging on the communal and societal level. The third meeting was earmarked for planning and sketching the final artworks, which would deal with the topics of belonging or non-belonging. There was the possibility of working either individually or as a group. Four artists started to plan a group artwork, but due to different scheduling problems they had to abandon the idea, and two of them ended up making their own individual artworks. [28]

In the visual arts workshop there was intense discussion about belonging, and the participants used various creative methods. The themes of belonging and non-belonging were approached from different angles, from personal feelings, experiences and different kinds of relationships to topical issues and conceptual examinations. Each artist participated in the exhibition, which included 11 works from this workshop.

Figure 4: Collaborative work in the visual arts workshop [29]

In this section, we will discuss the dimensions of belonging that surfaced in the workshop discussions and the interviews. We have named these dimensions stances. In sociolinguistics, stance-taking is a fundamental property of communication. Through stance-taking, individuals connect their communicative behavior with the broader social meanings and social life within which they interact (JOHNSTONE, 2009; OCHS, 1992). Here, we use the term stance to refer to the general position or perspective toward belonging that participants expressed in the discussions and in the interview. Our analysis of stance-taking emphasizes the importance of acknowledging collaborative practices in the construction of belonging through art-making. The collaboration and co-creation that were an essential part of the workshops entailed interactive and dialogical negotiation of the stances taken to belonging. [30]

For the sake of clarity, we have differentiated between various types of stances and exemplified them through different participants' experiences. In doing so, our intention is not, however, to reduce an individual participant's ideas on belonging to a single stance, but to identify these stances and highlight the fact that not only can belonging mean various things, but also that people position themselves to these meanings in different ways. As JAFFE (2009) notes, stance is achieved dynamically in ongoing interaction. Therefore, belonging was—and is—not perceived as a stable condition at any stage of the research. Several of the participants changed their views during the research process. For example, one participant may have expressed both optimism and skepticism. The changes in the stances toward belonging are linked to the nature of arts-based research, which foregrounds processualism, multiplicity, disruption and unpredictability. [31]

In the next section, we will present the four broad categories of stances that we identified: positive belonging, searching for belonging, struggling to belong, and skepticism toward belonging. Within each category, we first explore the ways in which the participants positioned themselves in relation to various notions of belonging. After that, we take a closer look at how the stances were expressed in the artworks made by six participants in the workshops, who are identified here only by the numbers 1–6. [32]

In line with most previous research, several participants saw belonging as a positive thing. They thus expressed a positive stance toward belonging and considered it to be something that could be achieved. For them, belonging meant attachment to a place and to people, and they had sought through their own activity to enhance the feeling of belonging. Even those who adopted a positive stance toward belonging did not expect that belonging to a new place, a new country of residence, for example, would come automatically. The fact that it requires effort, however, was not seen as a sacrifice, but rather as an adjustment, which could also be rewarding. One participant observed: "the sense of belonging grows in time, you have to give yourself time." [33]

Many of the participants had moved around a lot in their lives. When discussing aspects of belonging in positive terms, they emphasized their adaptability and ability to integrate: to attach themselves temporarily to new environments and groups. Despite some initial difficulties, some of the foreign participants had become attached to Finland even to the extent that it felt to them like a second home, which is a typical metaphor of positive belonging. One participant said that people generally feel that they belong to their country of birth, but it is possible later to achieve the feeling of belonging to another country. An apt comparison suggested by one of the participants as a model of a positive stance toward belonging was to the amoeba, exemplifying an understanding of belonging as a continuous process demanding flexibility. Belonging was thus defined as an ability that could be nurtured. [34]

Another participant defined belonging as a form of ownership, in which people or places claim ownership over one: "It has more to do with people around you who make you feel you are needed or missed. It has more to do with what's around you than what's inside you." She also noted that we need other people, even though society nowadays emphasizes individualism. For her, dependence and relationality were positive things. [35]

The positive stance toward belonging included optimistic and affirmative attitudes to the notion of belonging, which was seen as an achievable and desirable outcome of both integration and artistic processes in which the participants saw themselves as agents in their actions and communities. Art was thus a space where feelings of belonging and stances toward belonging could be negotiated. The process of making art also created spaces of belonging. [36]

4.1.1 Participant 1: Painting to belong

In the workshop discussions, Participant 1 objected to any categorizations and assumptions that were based on where artists or indeed people in general were born and raised. She thought there is no citizenship in art; rather, it is a democratic field and a universal language, where everyone is basically on the same line. [37]

She described art as a chronic illness, as she felt that she has to paint or do something creative all the time. For her, the process of making art, however, is a way of raising her spirits and a kind of escapist therapy. Through painting, she finds a refuge from anything distressing, and experiences a feeling of complete belonging. [38]

Participant 1 has a solid academic art education. In her artistic production, she has focused particularly on female figures. Participant 1 is interested in faces and personalities. For her, each person is an "event" composed of different emotions, and is the embodiment of philosophical and psychological aspects. In her artworks, moments, situations, thoughts and feelings are transformed into different subjects, allegories, metaphors and symbols. Many characters and elements in her works may seem ordinary, but for her they have a more profound meaning:

"Years ago, I had, for example, a painting series called ‘My Pearls'. The works consisted of a female figure and a pearl necklace. However, the topic did not portray the beauty or value of the jewel, but the philosophical thoughts of the journey of life. The works reflected the most beautiful and most important moments and memories which we have treasured and which we want to pass on to our children. Therefore, it is not just a female figure and a pearl necklace, but a completely different thing that the topic represents to me" (translated from Finnish by Antti VALLIUS). [39]

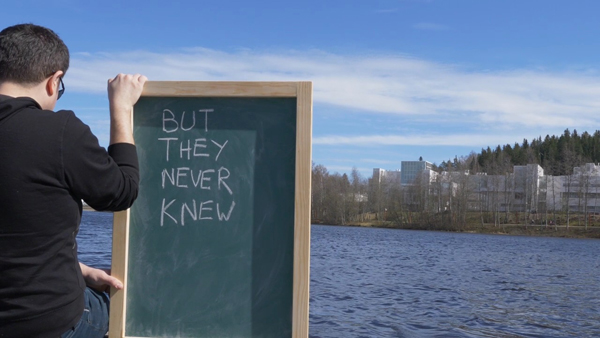

Her artworks are like milestones and checkpoints for certain feelings, memories and situations. She thinks that because life is short, she does not want to hold on to anything negative in her art, but the positive highlights or "pearls." Participant 1 thinks it is important that art should be positive and should carry a certain philosophical idea. The effect of art is reflected through the viewer into the surrounding world, and because of this she wants her work to suggest positive connotations and produce positive effects. [40]

Participant 1's artwork for this project was a kind of performance: at the opening of the exhibition to mark the end of the workshops she produced a painting from a live model. This process, in which she started from an empty canvas and finished with a portrait, was also video-recorded. The purpose of this work was to show the public how art is created and how the moment of inspiration, emotions, and the environment affect the artwork. With this kind of approach, the audience was able to see the whole process and what it was possible to create in this limited timeframe. Participant 1 thought that watching a live painting or a video of it could stimulate some members of the public to make their own art and to find happiness within it. The most important thing for her, however, was that the work was positive and celebrated the moment. At the same time, it illustrated her ability to achieve her own personal sense of belonging through painting.

Figure 5: Participant 1's work [41]

4.1.2 Participant 2: Biking to belong

Participant 2, from Tanzania, had come to Finland to study at university. She wanted to explore the world because she had never lived abroad before. Despite the initial culture shock, after living in Finland for a couple of years the country was becoming a second home to her. She understood belonging as attachment and connection to people and places. For her, adaptation meant trying out things like winter sports that were strange to her but that Finns do regularly. She also decided to learn to ride a bike in order to enhance her sense of belonging, but the attempt ended in a crash and some injuries and she decided to forget about cycling. In the workshop, she talked about this and saw something funny in it, worth telling other people. [42]

In her film, she relived the experience. The narrative consists of images of Participant 2 and her friend riding a bike slowly and carefully, accompanied by Participant 2's voice-over. The most challenging part of the production process for her was to make the story funny and to convey to the audience a sense of joy. Finding the right tone and attitude for the voice-over was crucial and she worried about this a great deal. With a deadpan style, however, she managed to make the audience at the premiere laugh. In the film, just before the accident there are animated elements to enliven it, such as the text "Very bad idea," making it tragicomic. The figure of a flying Finn comes and whisks her home. In the end, the voice-over comments that she has realized that she does not need cycling in order to belong, that there are other ways of belonging. Participant 2's positive stance toward belonging is also revealed in the way she saw the project through. Two other participants helped her with the filming, animation and editing. By reliving the cycling experience, she challenged herself even further: making the film encouraged her to practice cycling again: "I stepped out of my comfort zone, challenged myself. It helped me in some practical ways."

Figure 6: Participant 2's short film (a screenshot) [43]

Some participants claimed either that they had not quite found out where they belonged or that they were working on it. Their stance could be described as searching for belonging. They were wondering how, where or with whom they belonged. One participant, who had lived in many countries, said she had never felt she belonged either in her home country or with her family, and that she was looking for a place where she would feel like she belonged and where she could spend the rest of her life. For her, this mobile lifestyle was an attempt to deal with her situation or state, which she described as having an empty space inside her. She also expressed the idea that perhaps she could belong to the memories she creates. The idea that one needs to look for belonging within oneself was expressed in much stronger terms by another participant (discussed in the next section), who saw social relations, structures and material things as secondary to her own body and timeline, as she put it. These, she said, are the only enduring things in one's life. [44]

One participant said that he understood belonging as a continuous search for something. He believed that art could help one ponder questions of belonging and that it allows one to talk about things that are difficult to deal with. Three participants talked about the flow feeling they achieve when they are making their art. Having this kind of flow—Jeanne NAKAMURA and Mihaly CSIKSZENTMIHALYI's (2009) concept for "the experience of complete absorption in the present moment" (p.195)—while immersing themselves in something intrinsically rewarding, they lost a sense of time and place and felt they were one with the art-making process. For example, one participant described how, when painting, she sometimes forgets herself completely and feels like she would melt into her artwork. For her, the process of making art resembled an oceanic feeling. This feeling is defined in psychological and philosophical research mainly as a feeling of dissolution of the psychological and sensory boundaries of the self, which can lead to affective existential experiences of oneness with a given object, such as a work of art, or in a broader sense with the whole surrounding world (GOLDIE, 2008; SAARINEN, 2014). The conversations revealed that those who experienced a flow or an oceanic feeling during art-making felt somehow lost or unbalanced when they were not engaged in the making of art. The art-making process was thus seen both as an existential experience of being in the world and as a tool to search for this kind of belonging. [45]

4.2.1 Participant 3: Belonging to my own body

For Participant 3, the workshop coincided with major changes in her personal life and her search for a new kind of belonging. She had recently returned to Finland after having lived abroad for two and a half years. The topic of belonging was relevant to her as it "resonated with my own situation." She was finding it difficult to settle down in Finland again. She very quickly said that for her, belonging does not "have anything to do with social connections," nor even with primary groups like the family; these she considers temporary and easy to lose. Instead, she has started to look for belonging within herself, in her own "timeline" and bodily existence. In other words, she bases her belonging on those elements that remain with her when all other external structures are taken away: her own body and the meaningful actions she can perform with her body. She shared some of these ideas in the workshop discussions but kept most of them to herself until the interview, when she talked about the film she had been editing for some weeks but did not yet consider to be ready. [46]

Her film is an experimental documentary, in which she is the protagonist. The film is about finding a sense of belonging from within her own body at a time in her life when she does not feel any connection to the outside world. The film also features, almost as a second protagonist, a block of flats in the local student village. She had originally planned to make a documentary about foreign students living there, but in fact she ended up making a very personal film. In the film, she moves around and dances in the building, the various parts of which become metaphors for our relationship to the outer world. She likens us individuals, for example, to the bubbles that we can find inside fire safety glass, separated from each other by metal wires. Her moving figure is one element in the film, which plays with visual forms, sounds, and the words that her voice-over speaks. [47]

The voice-over starts by describing how we live with others, in cells like the apartments in the building; how we create routines and restrictions, create "bubbles for security" but also bubbles that divide us. She positions herself in the margins, whence she can observe the norms. She contemplates the relationship between the inside and the outside, not seeing clear boundaries between them. Finally, the voice-over says that when home disappears, one can only take hold of one's own hand and keep breathing. The voice-over describes the fragility of the body-home, but also declares, "This is your own. This is your home." [48]

This participant found a sophisticated cinematic expression for her thoughts about belonging. For her, making the film turned out to be a longer process than for the others; it was a search, and she continued to edit the film for several months after the workshop. She had had previous experience of filmmaking and so she had the skills to realize her vision, to find a subtle form for her subjective experiences and rather radical ideas. The most exciting thing for her was that the film would become a part of her. The excitement she felt is an indication that she was able to find a form for her thoughts by artistic means even though she had some doubts as to whether the audience would understand all of it. Her thinking about belonging involved a great deal of skepticism toward social structures and social relations, especially toward what she described as the rigidity of social relations in Finland. However, for her, belonging was possible and she seemed to have found ways to deal with the situation she was in. She defined belonging by saying, "At the moment it is belonging to my own body" (translated from Finnish by Kaisa HILTUNEN) suggesting that for her, too, it might mean something else at another time.

Figure 7: Participant 3's short film (a screenshot) [49]

Belonging had become a struggle for some participants, either as a result of experiences of exclusion and non-acceptance or because they had experienced major losses. They might have had a sense of belonging to a certain place, for example, but they were struggling now with other issues related to belonging. For one participant, the struggle was related to her return to her country of birth, Finland, where she felt she was not accepted because of her foreign accent, on account of which she experienced othering and exclusion. The situation was made worse for her because the people around her could not always relate to her problem and empathize with her:

"It's difficult for people, even my friends, to understand why I don't belong. Finns may say, stop pretending you're different! It's hard to find common ground in this field. I just don't belong where I'm officially meant to belong. (…) I've got the wrong passport basically." [50]

The struggles of belonging were also manifested in other ways. Shifting political relations between countries and political unrest within nation states caused worries and forced people to rethink their sense of belonging. One participant had lost his hometown in a massive earthquake. This event had completely destroyed his feelings of belonging on the spatial, social and emotional levels and had put him in the situation of struggling to belong. [51]

Professional art-making and one's position in the institutional art world was described as another site of struggle to belong. Two participants took the making of art quite seriously but were unsure about their status as professional artists. At the time of the interviews, both lacked formal art training, held no grant for making art and could not earn their livelihood by making art. In the absence of these characteristics commonly found among professional artists, they both felt that they were struggling to belong in the official art world. Both of them admitted that for them, networking with other artists and the local art scene, as well as with the Jyväskylä Art Museum as the representative of the institutional art world, were the main motivation for participating in the research. [52]

Notwithstanding a few exceptions, there was a clear absence in this group of a playful and light-hearted approach to belonging. For many participants, belonging meant a range of pressing issues that they felt they needed to work through. They reflected on the obstacles to belonging and cited difficult memories and traumas linked to personal development as root causes of their problems. For some, belonging was a process that involved distancing themselves from their family, for example, and working through their links to the past. [53]

Struggles to belong were related to clashes between social structures, the possibilities of belonging and people's desire to belong, the disappearance of the basis of belonging, and the lack of social support for belonging or of a recognition of belonging. Struggles to belong were both personal and professional, experienced in relation to social and institutional structures and communities. [54]

4.3.1 Participants 4 & 5: Restless belonging

Participants 4 and 5 are an Italian-Finnish artist couple, whose thoughts about belonging were heavily influenced by the earthquake that destroyed Participant 5's Italian home village in 2009. This traumatic experience led Participant 5 to lose the foundations of his feelings of belonging, and they both lost the place that was their second home. Participant 5 was forced to move permanently to Finland, his partner's home country, where he felt he did not belong. The couple's artistic approach toward belonging thus focused more on struggles or the difficulties of belonging and feelings of non-belonging. [55]

For the project's exhibition, the couple produced two installations, called "Kuuluminen/Appartenenza/Belonging" and "Rauhaton/Impaziente/Restless." In these works, art and artistic practice worked as a tool for them to think about the topic and deal with it and understand it more thoroughly. "Kuuluminen/Appartenenza/Belonging" can be interpreted as a representation that deals specifically with Participant 5's personal feelings and his experience of the loss of a personal sense of belonging. The work is made of concrete-like elements floating on thin lines in the air, and of trousers and a shirt molded in cement. The artwork can be connected to a number of themes such as balance, distortion and breakage, as well as the feelings of non-belonging, rootlessness and homelessness, which have all been characteristic of the couple's artistic production lately. In the work, cement dust covers and hardens the soft-woven clothing and the sky is raining rocks. It seems that the main idea behind the work was to create an absurd situation and through this provoke the viewer to think about what belongs where, and where everyone belongs. On the other hand, it is also possible to think that the work portrays that precise moment of the earthquake, when Participant 5's belonging turned into non-belonging with the collapse of the social and material infrastructure of the place of belonging of the whole community. It depicts the destruction of balance, but in a very balanced, harmonious and beautiful way. [56]

"Rauhaton/Impaziente/Restless," in turn, is a work that can be interpreted as an examination of and commentary on the global refugee crisis. In it, the subject of belonging or non-belonging is looked at as if from an outsider perspective. Participant 4 thought that although belonging is a very personal matter, it is often someone else who has the power to decide where people belong or what they can or should belong to. "Rauhaton/Impaziente/Restless" consists of a piece of old sewage pipe placed on a pedestal, a picture of a gloomy crowd painted on a piece of plywood, and real tree roots, which are reaching up a wall. The sewage pipe can be associated with a weapon because of its shape, or with a sewer on account of its original use. As a result, the human figures in the painting can be interpreted at the same time as either people fleeing war or as inferior human beings who are crawling out of the sewer. The latter interpretation can be linked in particular to the discrimination faced by many refugees. The roots can be seen as metaphors of fractured relationships or as beginnings of new attachments. In general, the work illustrates how art can handle complex phenomena simultaneously from many different perspectives and in a way from several different temporal angles as well. It also challenges the typical media coverage of refugees as flows and floods (see criticism, e.g., GABRIELATOS & BAKER, 2008). [57]

Although both works are independent, they settled in an interesting dialogue in the exhibition, where they were placed next to each other. In these artworks, the artists' personal experience and their trauma from the loss of home and second home can be seen as comparable to the general conflicts of the world and to other similar situations in which natural disasters, wars and conflicts destroy homes and drive people away from the places where they feel they belong. All these create homelessness, rootlessness and situations in which people struggle to belong.

Figure 8: Participant 4 and 5's works, "Rauhaton/Impaziente/Restless" on the left and "Kuuluminen/Appartenenza/Belonging" on the right [58]

4.4 Skepticism toward belonging

Skepticism toward belonging took several forms. One participant's stance toward belonging was affected by the idea of usefulness. He argued that belonging is no longer necessary, because people no longer need other people to make them feel safe. He connected belonging to the sense of security, which in the past was achieved through social relations, especially through kinship. To him, belonging signified at least partly dependence on other people, as opposed to independence and individuality, which he considered more positive and liberating. Some of the participants emphasized the connection between such a stance and the privileged position of Westerners today, arguing for example that people in the West have the luxury of not belonging. One participant claimed that because of their citizenship, Westerners can move around the world relatively freely and have more choice in life than people from less affluent parts of the world. However, even the most skeptical participant realized that to a certain extent belonging is useful and necessary. Even in his case, belonging and non-belonging were not seen as mutually exclusive. [59]

This stance included the view that there is something oppressive in the word belonging. In fact, one participant considered the word belonging too strong: to him it implied the necessity of belonging somewhere, whereas he was not sure if he wanted to belong anywhere. He recognized some groups, such as his own family and his working community, as being important to him, but he was not comfortable calling this type of connection belonging: "You need some level of belonging. You need to be a part of a community. However, is that belonging? Is being a citizen belonging?" [60]

In one case, the skepticism was a result of the participant's own background as a third-generation North American immigrant. She felt no attachment to any national identity but had developed a migrant identity. Her emotional reactions and experiences led her to think about belonging as a mutual relationship: she felt that belonging is based on the opinion and willingness of other parties. Therefore, if one does not want to belong somewhere, one is free to choose non-belonging. Further, if one does want to belong somewhere but someone or something—a person or a public or private body—does not want one to, the power exercised by the other leads to non-belonging. In her view, therefore, belonging is by no means automatic or straightforward, but a process that demands constant negotiation. [61]

Skepticism toward belonging, in some form or other, was expressed by a majority of the participants. In some participants the word belonging aroused ideas that they did not like; they would have preferred some other term to describe their attachments. For others, skepticism was linked to experiences of mobility and to the feeling of being a privileged citizen of a Western country. [62]

4.4.1 Participant 6: Freedom in isolation

In the exhibition catalogue participant 6 introduces himself as "abysmally normal" and does not want to reveal too much about himself, as he would like his work to speak for itself. His video explores the productive tensions between the individual and the group. It can therefore be seen as an allegory of collaborative arts-based practices in which both individual creative work and co-creation play a role, as well as of the nature of belonging as such. [63]

The video is a combination of text read by a narrator and a compilation of video footage shot both indoors and outdoors, in places chosen apparently at random. In the text, a group of individuals are searching for belonging. Places and environments are merely shifting contexts for the group, about whom very little is revealed. At issue is the quest for belonging, the search for one's place in the universe. There are no maps, advice or ready-made solutions that will help one to find belonging. Along the route, one has to deal with issues such as loss, alienation, amnesia and unresolved efforts to blend in. The quest for belonging ends in finding peace with oneself and building one's self-integrity. The text reads:

"Their map was torn off. And their route was unchartered. They asked the ones that they faced. They were never answered back. As if they knew what to ask.

First, they drank in silence. Then they gazed in silence. They wrapped themselves up in that silence and sought for more silence in it. They thought a shred of peace was hidden in it.

They listened as the ones they met chattered. They heeded to no avail. All words were in an alien language. And they nodded. All the feelings were alien.

They didn't get any closer. They didn't get any further. It was there all along. Just where they were not.

Some lost what was dearest to them. But then they forgot. What was lost was recovered in their amnesia. They found what wasn't there. They mimicked to understand. They twisted themselves to blend in. For once, they wanted to hear. There was nothing to hear." [64]

The text, full of ambiguities, leaves it open who the people are and where they are wandering. It seems to emphasize that belonging has nothing to do with place attachments or ethnicity, nationality or religion. This understanding of belonging is the antithesis of a belonging that is grounded, on the one hand, in place attachments and ideas that combine the self and place, and on the other hand in group identity. Rather, belonging means finding one's place in the universe. This understanding of belonging centers around existentiality. The avoidance of clear identity markers translates into the idea of "freedom in isolation." Isolation is a promise of happy non-belonging. In the end, the work poses the question of whether there is anything for which we need belonging. [65]

The journey of the anonymous group of people searching for the meaning of belonging ends in a void when they decide to take a leap into emptiness. If the work speaks allegorically about the process of art-making in a group searching for the meanings of belonging, it skeptically poses the question of whether there is any sense in exploring belonging through art-making. Participant 6 answered this when he recalled his experience of the workshop, explaining that

"the following months were filled with inspiring discussions, sharing, welding the group together, or dissecting ideas—and eventually creating our final works, with which we gave our own answers to the questions that we had been asking ourselves. I take great joy in my work as I see that it speaks for itself, encouraging interpretations, and nudged the viewers to pose their own questions, if not answers." [66]

Art-making may not lead to answers, but it may offer an opportunity to process unaddressed aspects of one's life and open up spaces for others to pose their own questions. Participant 6's work suggests that the creative process is more important than the finalized work of art, providing ways of knowing what belonging is rather than knowledge about belonging.

Figure 9: Participant 6's video (a screenshot) [67]

In this article, we have described how we analyzed the potential of artistic practice to explore the topic of belonging in the Crossing Borders project. We have shown that it is indeed possible to generate multifaceted ways of knowing about belonging through artistic practice, and we suggest that these ways of knowing are an important addition to the scholarly research on belonging. [68]

We have shown on both the conceptual level and the material level of the artworks that belonging can be understood, defined and expressed in a wide variety of ways. The four stances (positive belonging, searching for belonging, struggling to belong, skepticism toward belonging) and the examples of art produced in the three workshops of the Crossing Borders project give an idea of this multitude of meanings. The artistic methods employed in this project encouraged collaboration and sharing, and helped provide very nuanced and situated knowledge about belonging, which is often—but by no means always, or merely—related to personal experience and emotions. In general terms, our findings in this arts-based research serve to confirm our previous conceptual understanding of belonging as fluid, flexible and context specific (LÄHDESMÄKI et al., 2016). Even for the individual participants, the meaning of belonging changed over the course of the approximately four months that the workshops lasted, and many predicted that it would continue to do so in the future. [69]

These findings echo EISNER's (2008) suggestion that perhaps art should be considered a way of knowing rather than a form of knowledge. Knowing refers to ways of inquiry that is not expected to produce "nailed down facts" but rather "tentative conclusions" (p.3). Specific to artistic knowing, according to EISNER, are that "the arts address the qualitative nuances of situations" (p.9), art "has to do with empathic feeling," it "offers fresh perspectives" (p.10) and helps us get rid of old habits of perceiving and interpreting, and, finally, it "makes us aware of our capacity to feel" (ibid.). The artworks produced in the workshops were a way of expressing knowledge, or offered a way of knowing, that goes beyond traditional notions of language, "ineffable knowledge," as EISNER (p.5) says. The artworks also offer new perspectives toward belonging, such as bodily belonging and belonging through art-making, that merit further study. [70]

It appears that the collaborative artistic practice that emerged in this project is particularly suited to expressing personal stances of belonging or non-belonging. Participants took different positions toward the collaborative working methods. Some took advantage of the chance to work with others, while others preferred to work on their own. Several participants concentrated on dealing with their current situation and issues on a very personal level. However, some participants who disclosed a great deal about their own lives in the workshops decided not to make themselves the subject of their own artworks, at least not explicitly, preferring to focus, for example, on other people's experiences or on political issues. It seems, though, that even these works that on the surface seem to be distanced from personal issues had such issues in the background. [71]

The workshops provided the participants with a contact zone (PRATT, 2008) where they could learn from each other and test and develop their ideas about belonging. PRATT has defined contact zones as "social spaces where disparate cultures meet, clash, and grapple with each other, often in highly asymmetrical relations of domination and subordination—like colonialism, slavery, or their aftermaths as they are lived out across the globe today" (p.6). According to ESIN, the term, which PRATT developed to criticize imperial encounters, "has been expanded to include the interactions between global and local, transnational and national, identity and difference and space and time" (ESIN, 2017, §30). [72]

Also our workshops can be described as contact zones where different views about migration and mobility, for example, met and occasionally even clashed. Many, even most, of the participants noted that hearing other people's thoughts about belonging was important—for many, the most important thing—and affected their own thinking, sometimes helping them to clarify their own thoughts, sometimes confusing and challenging them. This, of course, applies to us researchers, too. This context needs to be taken into account when the artworks are discussed and analyzed. The ideas for the works were shaped in the workshop discussions (and certainly also outside of the workshops), where ideas were shared, different opinions heard, and feedback received. In the analysis, it is sometimes difficult to draw a clear line between the ideas expressed in the discussions and the ideas expressed in the finished works. This is also because we researchers were present in the workshops and were able to follow most of the discussions that contributed to the final artworks. [73]

As products of a researcher-initiated project, the artworks produced in the workshops are individual works of art in their own right, and subjects for analysis. They are also research outcomes. The artworks would not exist without the research project and the researchers, who invited people to participate and explore belonging. Although the works can be viewed as individual works of art—the ideas expressed in them and the aesthetic choices are the participants' own—the works also need to be seen and understood in the context of the research project. The finished works are a part, a continuation, of the whole process, which continues to affect those who took part in it in many ways. [74]

The artworks can be considered repositories of the changing understandings and stances that the participants took to belonging. The artworks anchor the ever-shifting stances into material forms and expressions that enable us to return to them later. Artistic practice is thus one way of defining and situating the fluid concept of belonging. Moreover, through the artworks, the ideas and negotiations that had their origins in the workshops are distributed more widely. In this project, this was made possible by the public events and the exhibition, which offered other people the opportunity to join the discussion and continue the negotiation about belonging. (The web gallery on the project's web site serves a similar, yet more limited purpose.) It was through the presentations and the context of the exhibition, the institutional art museum, that the artworks became independent works of art, going beyond their status as research material. We recognize that further analysis of the subtleties and specificities of the various forms and means of artistic expression, as well as of the creative process, is called for. [75]

This article is based on a research project Crossing Borders funded by the Academy of Finland (308520). We would like to thank all the people who participated in the Crossing Borders workshops and our collaborators, the multicultural center Gloria and Jyväskylä Art Museum.

1) The concept of vulnerability has recently been debated and contested in a number of fora. For this critical discussion, see e.g., HONKASALO (2018) and VIRONKANNAS, LIUSKI and KURONEN (2018). <back>

Ballenthien, Jana & Büching, Corinne (2009). Insecure belongings: A family of ethnic Germans from the former Soviet Union in Germany. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung / Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 10(3), Art. 21, http://dx.doi.org/10.17169/fqs-10.3.1373 [Accessed: April 17, 2020].

Bell, David M. & Pahl, Kate (2018). Co-production: Towards a utopian approach. International Journal of Social Research Methodology, 21(1), 105-117, https://doi.org/10.1080/13645579.2017.1348581 [Accessed: April 19, 2020].

Bradley, Jessica; Moore, Emilee; Simpson, James & Atkinson, Louise (2018). Translanguaging space and creative activity: Theorising collaborative arts-based learning. Language and Intercultural Communication, 18(1), 54-73.

Chaitin, Julia; Linstroth, J.P. & Hiller, Patrick T. (2009). Ethnicity and belonging: An overview of a study of Cuban, Haitian and Guatemalan immigrants to Florida. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung / Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 10(3), Art. 12, http://dx.doi.org/10.17169/fqs-10.3.1363 [Accessed: April 17, 2020].

Cutcher, Alexandra, J. (2015). Displacement, identity and belonging. An arts-based, auto/biographical portrayal of ethnicity and experience. Rotterdam: Sense Publishers.

Eisner, Elliot (2008). Art and knowledge. In J. Gary Knowles & Ardra L. Cole (Eds.), Handbook of the arts in qualitative research: Perspectives, methodologies, examples, and issues (pp.3-12). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Esin, Cigdem (2017). Telling stories in pictures: Constituting processual and relational narratives in research with young British Muslim women in East London. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung / Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 18(1), Art. 15, http://dx.doi.org/10.17169/fqs-18.1.2774 [Accessed: April 17, 2020].

Gabrielatos, Costas & Baker, Paul (2008). Fleeing, sneaking, flooding: A corpus analysis of discursive constructions of refugees and asylum seekers in the UK Press 1996-2005. Journal of English Linguistics, 36(1), 5-38.

Goldie, Peter (2008). Freud and the oceanic feeling. In Willem Lemmens & Walter Van Herck (Eds.), Religious emotions: Some philosophical explorations (pp.219-229). Cambridge: Cambridge Scholars Publishing.

Hickey-Moody, Anna Catharine (2018). Materialising the social. RUUKKU—Studies in Artistic Research, 9, https://doi.org/10.22501/ruu.371583 [Accessed: April 19, 2020].

Hiltunen, Kaisa (2019a). Sisään- ja ulossulkemisen strategiat Leijonasydämessä [The strategies of inclusion and exclusion in Leijonasydän]. In Kaisa Hiltunen & Nina Sääskilahti (Eds.), Kuulumisen reittejä taiteessa [Ways of belonging in the arts] (pp.78-101). Turku: Eetos.

Hiltunen, Kaisa (2019b). Seitsemän elokuvaa kuulumisesta. Lyhytelokuva menetelmänä ja tutkimuksen kohteena osallistavassa hankkeessa [Seven films about belonging. Short film as a method and research topic in a participatory research project]. Wider Screen, December 19, http://widerscreen.fi/numerot/ajankohtaista/seitseman-elokuvaa-kuulumisesta-lyhytelokuva-menetelmana-ja-tutkimuksen-kohteena-osallistavassa-hankkeessa/ [Accessed: April 19, 2020].

Hiltunen, Kaisa & Sääskilahti, Nina (Eds.) (2019). Kuulumisen reittejä taiteessa [Ways of belonging in the arts]. Turku: Eetos.

Hiltunen, Kaisa; Sääskilahti, Nina; Ahvenjärvi, Kaisa; Jäntti, Saara; Lähdesmäki, Tuuli; Saresma, Tuija & Vallius, Antti (2019). Kuulumisen neuvotteluja taiteessa [Negotiations of belonging in art]. In Kaisa Hiltunen & Nina Sääskilahti (Eds.), Kuulumisen reittejä taiteessa [Ways of belonging in the arts] (pp. 9-27). Turku: Eetos.

Honkasalo, Marja-Liisa (2018). Guest editor's introduction: Vulnerability and inquiring into relationality. Suomen antropologi, 43(3), 1-21.

Jäntti, Saara & Loisa, Janne (Eds.) (2018). Kotiteatteriprojekti. Teatteri toipumisen välineenä -hankkeen loppuraportti [The final report of the Theatre as a Tool to Recovery project]. Jyväskylä: Jyväskylän yliopisto.

Jäntti, Saara; Laakkonen, Riku; Mikkola, Tomi; Perhomaa, Janne; Salminen, Jarkko; Tanner, Jarno; Uskola, Tommi; Vuoristo, Mirka; Ylimäinen, Arto; Hakuni, Helena; Honkasalo, Marja-Liisa & Rajanti, Christa (2018). Kotiteatteriprojekti esittää: Hahmotelmia kodiksi [The THEATRE project presents: Sketches for home]. Tutkiva sosiaalityö, 73-84, http://talentia.e-julkaisu.com/2018/tutkivasosiaalityo/#page=73 [Accessed: April 19, 2020].

Jaffe, Alexandra (Ed.) (2009). Stance: Sociolinguistic perspectives. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Johnstone, Barbara (2009). Stance, style and the linguistic individual. In Alexandra Jaffe (Ed.), Stance: Sociolinguistic perspectives (pp. 2-43). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Korjonen-Kuusipuro, Kristiina; Kuusisto, Anna-Kaisa & Tuominen, Jaakko (2019). Everyday negotiations of belonging—making Mexican masks together with unaccompanied minors in Finland. Journal of Youth Studies, 22(4), 551-567, https://doi.org/10.1080/13676261.2018.1523539 [Accessed: April 19, 2020].

Lähdesmäki, Tuuli; Ahvenjärvi, Kaisa; Hiltunen, Kaisa; Jäntti, Saara; Saresma, Tuija; Sääskilahti, Nina & Vallius, Antti (2014). Mapping the concept(s) of belonging. In Stuart Picken & Jerry Platt (Eds.), ACCS2014 The Asian conference on cultural studies, conference proceedings 2014 (pp.85-99). Nagoya: The International Academic Forum, http://iafor.org/Proceedings/ACCS/ACCS2014_proceedings.pdf [Accessed: September 24, 2019].

Lähdesmäki, Tuuli; Saresma, Tuija; Hiltunen, Kaisa; Jäntti, Saara; Sääskilahti, Nina; Vallius, Antti & Ahvenjärvi, Kaisa (2016). Fluidity and flexibility of “belonging”: Uses of the concept in contemporary research. Acta Sociologica, 59(3), 233-247.

Lehtonen, Jussi & Pöyhönen, Sari (2019). Documentary theatre as a platform for hope and social justice. In Eeva Anttila & Anniina Suominen (Eds.), Critical articulations of hope from the margins of arts education. International perspectives and practices (pp.31-44). London: Routledge.

Löytty, Olli (2017). Welcome to Finnish literature! Hassan Blasim and the politics of belonging. In Katrien De Graeve, Riikka Rossi & Katariina Mäkinen (Eds.), Citizenships under construction: Affects, politics and practices (pp.67-82). Helsinki: Helsinki Collegium for Advanced Studies.

Nakamura, Jeanne & Csikszentmihalyi, Mihaly (2009). Flow theory and research. In Charles R. Snyder & Shane J. Lopez (Eds.), Oxford handbook of positive psychology (pp.195-206). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Ochs, Elinor (1992). Indexing gender. In Alessandro Duranti & Charles Goodwin (Eds.), Rethinking context: Language as an interactive phenomenon (pp.335-358). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Oikarinen-Jabai, Helena (2017a). Mulla on kans suomalaisuutta alitajunnassa—somalitaustaisten nuorten näkökulmia suomalaisuuteen ["I also have Finnishness in my unconsciousness": Young people with Somali background exploring Finnishness]. Lähikuva, 30(4), 38-56, https://doi.org/10.23994/lk.69010 [Accessed: April 19, 2020].

Oikarinen-Jabai, Helena (2017b). Suomensomalialaiset nuoret paikantumisiaan tutkimassa [Finnish Somalian youth exploring their local belonging]. Nuorisotutkimus, 35(1-2), 40-53.

Oikarinen-Jabai, Helena (2019). Young Finnish people of Muslim background: Creating "spiritual" becomings and coming communities in their artworks. Open Cultural Studies, 3(1), 148-160, https://doi.org/10.1515/culture-2019-0013 [Accessed: April 19, 2020].

Pöyhönen, Sari; Kokkonen, Lotta; Tarnanen, Mirja & Lappalainen, Maija (2020). Belonging, trust and relationships: Collaborative photography with unaccompanied minors. In Emilee Moore, Jessica Bradley & James Simpson (Eds.), Translanguaging as transformation: The collaborative construction of new linguistic realities (pp.58-75.). Bristol: Multilingual Matters.

Pratt, Mary Louise (2008). Imperial eyes: Travel writing and transculturation. New York, NY: Routledge.

Roos, Vera; Stockie Kolobe, Patricia & Keating, Norah (2014). (Re)creating community: Experiences of older women forcibly relocated during apartheid. Journal of Community & Applied Social Psychology, 24(1), 12-25, https://doi.org/10.1002/casp.2177 [Accessed: April 19, 2020].

Rouvoet, Marjo; Eijberts, Melanie & Ghorashi, Halleh (2017). Identification paradoxes and multiple belongings: The narratives of Italian migrants in the Netherlands. Social Inclusion, 5(1), 105-116, http://dx.doi.org/10.17645/si.v5i1.779 [Accessed: April 19, 2020].

Saarinen, Jussi Antti (2014). The oceanic feeling in painterly creativity. Contemporary Aesthetics, 12, https://www.contempaesthetics.org/newvolume/pages/article.php?articleID=704 [Accessed: April 19, 2020].

Saresma, Tuija (2019). Hajauttamisen ja poissaolon politiikkaa Mohsen Emadin elämässä ja runossa "YAMSA—A tribute to absence" [The politics of dislocation in Mohsen Emadi's life and his poem "YAMSA—A tribute to absence“]. In Kaisa Hiltunen & Nina Sääskilahti (Eds.), Kuulumisen reittejä taiteessa [Ways of belonging in the arts] (pp.201-228). Turku: Eetos.

Saresma, Tuija & Jäntti, Saara (Eds.) (2014). Maisemassa. Sukupuoli suomalaisuuden kuvastoissa [In landscape: Gender in imageries of Finnishness]. Jyväskylä: Nykykulttuuri.

St. Pierre, Elizabeth Adams (2013). The posts continue: becoming. International Journal of Qualitative Studies in Education, 26(6), 646-657.

Vacchelli, Elena (2017). Embodiment as qualitative research: Collage making with refugee, asylum seeking and migrant women. Qualitative Research, 18(2), 171-190.

Vallius, Antti; Haapakangas, Eeva-Leena; Pöyhönen, Sari; Saresma, Tuija; Jäntti, Saara; Hiltunen, Kaisa & Sääskilahti, Nina (Eds.) (2019). Crossing Borders—Rajojen yli. Taidenäyttely Galleria Ratamossa 7.2.-3.3.2019 [Art Exhibition in the Gallery Ratamo]. https://www.jyu.fi/hytk/fi/laitokset/solki/tutkimus/hankkeet/crossing-borders-nayttely.pdf [Accessed: April 27, 2020].

Van der Vaart, Gwenda; van Hoven, Bettina & Huigen, Paulus P.P. (2018). Creative and arts-based methods in academic research. Lessons from a participatory research project in the Netherlands. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung / Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 19(2), Art. 19, http://dx.doi.org/10.17169/fqs-19.2.2961 [Accessed: April 19, 2020].

Virokannas, Elina; Liuski, Suvi & Kuronen, Marjo (2018). The contested concept of vulnerability—a literature review. European Journal of Social Work, 23(2), 327-339.

Wernesjö, Ulrika (2015). Landing in a rural village. Home and belonging from the perspectives of unaccompanied young refugees. Identities, 22(4), 451-467.

Yuval-Davis, Nira (2011). The politics of belonging. Intersectional contestations. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Kaisa HILTUNEN is a senior researcher at the Department of Music, Art and Culture Studies, University of Jyväskylä. She is a film scholar who has recently studied belonging, representations of otherness and Nordic noir. She is currently interested in exploring the human relationship to nature through film.

Contact:

Kaisa Hiltunen

Department of Music, Art and Culture Studies

University of Jyväskylä

P.O. Box 35, 40010 University of Jyväskylä, Finland

Tel.: +358 400 613196

E-mail: kaisa.e.hiltunen@jyu.fi

Nina SÄÄSKILAHTI is a senior researcher at the Department of Music, Art and Culture Studies, University of Jyväskylä. In her research, she deals with belonging and politics of belonging in literature. She is currently working with creative practices of listening and new materialist arts-based research.

Contact:

Nina Sääskilahti

Department of Music, Art and Culture Studies

University of Jyväskylä

P.O. Box 35, 40010 University of Jyväskylä, Finland

Tel.: +358 40 6766287

E-mail: nina.saaskilahti@jyu.fi

Antti VALLIUS is a post-doctoral researcher at the Centre for Applied Language Studies, University of Jyväskylä. He is an art historian whose main interests are landscape and the visual representation of environment.

Contact:

Antti Vallius

Centre for Applied Language Studies

University of Jyväskylä

P.O. Box 35, 40010 University of Jyväskylä, Finland

Tel.: +358 40 8053840

E-mail: antti.s.vallius@jyu.fi

Sari PÖYHÖNEN is a professor of applied linguistics at the Centre for Applied Language Studies, University of Jyväskylä. In her research, she focuses on language issues of migration, asylum, settlement and belonging.

Contact:

Sari Pöyhönen

Centre for Applied Language Studies

University of Jyväskylä

P.O. Box 35, 40010 University of Jyväskylä, Finland

E-mail: sari.h.poyhonen@jyu.fi

Saara JÄNTTI is a senior researcher at the Department of Language and Communication Studies, University of Jyväskylä. In her research, she deals with the relation of mental health to space, place, home and belonging through literature and applied theater.

Contact:

Saara Jäntti

Department of Language and Communication Studies

University of Jyväskylä

P.O. Box 35, 40010 University of Jyväskylä, Finland

Tel.: +358 40 8053180

E-mail: saara.j.jantti@jyu.fi

Tuija SARESMA is a senior researcher at the Department of Music, Art, and Culture Studies, University of Jyväskylä, and adjunct professor at the Centre for Contemporary Culture, University of Jyväskylä and Cultural Studies, especially Gender Studies, University of Eastern Finland. Her research interests include belonging and exclusion, hate speech, intersectionality, and populist rhetoric.

Contact:

Tuija Saresma

Department of Music, Art and Culture Studies

University of Jyväskylä

P.O. Box 35, 40010 University of Jyväskylä, Finland

Tel.: +358 40 805 3841

E-mail: tuija.saresma@jyu.fi

Hiltunen, Kaisa; Sääskilahti, Nina; Vallius, Antti; Pöyhönen, Sari; Jäntti, Saara & Saresma, Tuija (2020). Anchoring Belonging Through Material Practices in Participatory Arts-Based Research [75 paragraphs]. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung / Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 21(2), Art. 25, http://dx.doi.org/10.17169/fqs-21.2.3403.