Volume 22, No. 1, Art. 5 – January 2021

How to Involve Young Children in a Photovoice Project. Experiences and Results

Corinne Butschi & Ingeborg Hedderich

Abstract: For a considerable period of time, discussions on children and how they describe their own life-worlds did not form a part of research practice (CHRISTENSEN & JAMES, 2008). Although some methods are currently being applied with success in research with children, a more comprehensive implementation of different participatory methods is necessary which takes into account the child's peculiarities. One aim of the project "Learning Together, Living Diversity" was to involve children of kindergarten age in participatory research. To demonstrate diversity in a context close to everyday life and to start conversations with the children about this topic we used photographs taken by the children in their living environment. We aim to use the collected findings to develop a didactic method for early childhood education dealing with diversity in the sense of a basic form of existence: every person is unique, and this uniqueness should be perceived as enrichment. In this method, the early childhood phase and the institutional experiences embedded within it are considered fundamental to understand and accept the existence of various life-worlds.

Key words: research with children; participative research; group discussion; photovoice method; puppet interview

Table of Contents

1. Introduction

2. Participatory Research and Participatory Research with Children

3. Research Questions, Sample and Methods

4. Results and Discussion

4.1 How do young children see their world?

4.2 How can young children participate in research? Is the photovoice method suitable?

4.3 How Can Young Children Be Involved in Group Discussions?

5. Conclusion

5.1 Planning and introduction phase

5.2 Cooperation with the children and photography phase

5.3 Group discussions and talk about diversity

5.4 General conclusion regarding the photovoice method

Discussions about research with children as central informants of their own life-worlds were rare for a relatively long time. As CHRISTENSEN and JAMES formulated:

"Traditionally, childhood and children's lives have been explored solely through the views and understandings of their adult caretakers who claim to speak for children. This rendered the child as object and excluded him/her from the research process. In part, this perspective has been challenged by the perspective in which children have different cognitive and social developmental traits that the researcher who wishes to use children as informants needs to consider in their research design and research methodology" (2008, p.2f.). [1]

In recent years this view has been developed, and the focus is now more on research with children rather than on them. The photovoice method is a research method which enables the inclusion of other forms of expression alongside the verbal. It thus demonstrates considerable potential for use when researching groups for whom verbal communication is more difficult (e.g., young children, people with verbal disabilities). [2]

This contribution is based on a practical example of photovoice research: the project "Learning Together, Living Diversity," which was carried out from July 2016 to July 2019. In this international participatory project, we sought to research diversity from a child's perspective by working with children at kindergarten age (four to six). Two kindergartens in Switzerland (32 children) and two in Argentina (52 children) participated in the study. It was carried out using photovoice, a method which attempts to engage community participants—here, children—"as active research participants by giving them cameras and inviting them to take pictures dealing with various aspects of their lives" (JORGENSON & SULLIVAN, 2009, Abstract). In a subsequent interview, children in small groups were asked to explain their photographs and thus explore the subjective meaning of the images. [3]

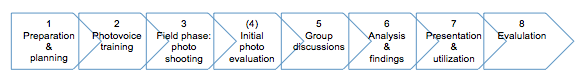

Our project had the primary aim of visually capturing the worldview of young children in order to find out which aspects of the child's life-world are of particular importance from his/her point of view. A secondary goal was to further increase the participation of kindergarten-age children by amplifying their voice and honoring their childhood experiences. The findings should help us to develop a didactic medium for early childhood education in the field of sensitization when dealing with diversity. In this article, we focus mainly on field research which includes children as co-researchers. We outline the practice of involving children in participatory research using the photovoice method, and describe the group interviews which form part of this method. [4]

We structured the article into five sections. Following this introduction, we situate in Section 2 briefly the photovoice method within the field of participatory research with children. In Section 3 we present the research questions of the project, the sample, and the methods we used. We delineate how the photovoice method was implemented with the children, and how we mastered challenges. We also briefly discuss the use of a hand puppet. In Section 4 we discuss the research questions and we list the themes photographed by the children alongside their various associations with diversity. Finally, in Section 5 we summarize key points and present a conclusion. [5]

2. Participatory Research and Participatory Research with Children

Participatory research is a generic term for a research approach which explores social reality on a partnership basis, thereby influencing and changing social reality (VON UNGER, 2012). It is therefore not to be seen as a method in itself, but rather encompasses a broad spectrum of different methods used in various fields of research. With the following small selection of different projects we intend to show how flexibly the approach can be used, and to illustrate how language, and local knowledge in particular, play a central role. [6]

RIECKEN, STRONG-WILSON, CONIBEAR, MICHEL and RIECKEN (2004) discussed a project conducted using the participatory action research (PAR) method with aboriginal teachers and youth in Canada; VON UNGER (2012) wrote about participatory health research; and PFEIFFER (2013) reported on a participatory video project conducted with young people aged 15 to 19 in Tanzania. Participatory research with active involvement was also used in the field of school development, as FEICHTER (2015) and WÖHRER (2017) showed. BERGOLD and THOMAS (2012) meanwhile, provided an excellent overview of participatory research in their introductory article for the FQS issue "Participatory Qualitative Research." [7]

Photovoice is a qualitative and participatory method which enables researchers to have a greater understanding of the issue being studied. Its use "in conjunction with both community knowledge and best practice evidence" may lead to "the development of effective and comprehensive strategies to address complex […] issues in a way that is also meaningful for the community involved" (NYKIFORUK, VALLIANATOS & NIEUWENDYK, 2011, p.104). The term "photovoice" was originally proposed by WANG and BURRIS (1994, 1997) in the early 1990s. Their methods included a number of distinct steps which outlined participant and policy-maker recruitment and data collection (see also WANG 1999). In this approach, participants take photographs of things which are meaningful to them. The photographs they choose are subsequently shared and discussed in a group setting with the aid of a facilitator-guide (for details, see VON UNGER, 2014; WANG, 1999). [8]

The photovoice method can be adapted by researchers, depending on the research question, time and cost factors, special characteristics of the research group or the research context, and so on. A photovoice process usually consists of seven phases (excluding Step 4 in Figure 1, which we added due to the design of our project):

Figure 1: Process steps in photovoice (VON UNGER, 2014, p.71, our adaptation) [9]

CHRISTENSEN and JAMES stated that "research with children has not only grown in volume, but in doing so, it has also generated a more engaged discussion of the particular methodological and ethical issues that this raises for social researchers" (2008, p.1). Such reflection on these issues brings new conceptual and theoretical problems into the methodological debate. The authors argued that "the particular methods chosen for a piece of research should be appropriate for the kind of research study, for its social and cultural context and for the kind of research questions that are being posed" (p.3). [10]

Conducting research with children HEINZEL (2012, p.24) noted that the main point of interest was the reality they experience and the position of the child within society. It is crucial to remember that adult researchers can only articulate the experiences and interests of children on this basis, even though the children themselves are involved in the research (ibid.). FUHS (1999) claimed that even child-appropriate research is based on those images of childhood that adults have from the child. DAVIS, WATSON and CUNNINGHAM-BURLE (2008), meanwhile, argued that it is important for adult researchers to form relationships in which children feel comfortable and to give them a feeling of control. [11]

Some methods have already successfully been employed in research with children, such as qualitative interviews (VOGL, 2019), puppet interviews (WEISE 2008, 2019) and picture-based interviews (which are also part of the photovoice method). A number of participatory approaches have also been employed, such as photovoice (VON UNGER, 2014; WANG & BURRIS, 1997), the mosaic approach (CLARK & MOSS, 2011; SCHÜTZ & BÖHM, 2019), and the MacArthur Story Stem Battery (EMDE, WOLF & OPPENHEIM, 2003; MÖGEL, 2019). The latter is also known as photo elicitation, and was first mentioned in 1957 in a work by COLLIER. [12]

Both photovoice and photo elicitation involve the use of photographs to gather information about a focus group for research, educational or healing purposes. However, photovoice offers more. Photovoice methodology is employed to empower and transform the community through participation in the research process; images are always taken by the participants, and more opportunities for participation are afforded than in photo elicitation. The main goal of the latter is the enrichment of research interviews through the use of images to gain new perspectives. The images are usually created by the researchers or by third parties, and they are intended to facilitate better understanding of their subjects (GOMEZ, 2020). Visual research methods such as these are becoming increasingly popular in the social sciences (MARGOLIS & PAUWELS, 2011), especially when research is concerned with including verbally vulnerable groups. [13]

The self-production of photos offers some methodological advantages. By allowing participants to photograph their surroundings themselves, researchers gain a context-sensitive, comprehensive and authentic insight into a field of investigation. This insight might not be possible with other methods or from a researcher's position. The images are well suited to the study of emotional processes because they facilitate access to cognitively less filtered information (ADOLPHS, DAMASIO, TRANEL, COOPER & DAMASIO, 2000; PAIVIO, 1990). The data quality of photographs is high as they are a rich source of interpretation. The information on photographs is characterized by implicit assumptions and ideas which are often not verbalized (MOSER, 2005). A further advantage is that photography is not language-bound, and different language groups can be reached simultaneously. This method therefore has considerable potential in involving groups for whom exclusively verbal and/or written communication poses difficulties, such as young children and also people with verbal disabilities. [14]

Photographs are associated with automatic processes like low abstraction, psychological proximity and primary emotions, while verbalization is related to more controlled processes such as high abstraction, high psychological distance and secondary emotions (AMIT, WAKSLAK & TROPE, 2013). The combination of photography and verbalization is therefore expected to result in deep individual psychological exploration processes. Moreover, it may be assumed that a child's observation of his or her own images promotes verbal processes. On the level of narrative and discussion, implicit knowledge can be made accessible through the effects of form-closure, condensation, and detailing. A narrative can thus take on a life of its own, and reveal latent structures of meaning (FLICK, 2011). [15]

Although photovoice is a time and resource-intensive method that requires flexibility and empathy, its openness to the views of children can provide important information for the production of didactic media tailored to the target group, or—depending on the interests at stake—for planning measures appropriate to the particular interests of the target group. In addition, the creation of a symbolic object such as a photograph and a high level of participation may be accompanied by the experience of pride, social influence and authenticity (e.g., CSIKSZENTMIHALYI, 1993; MALAFOURIS, 2013; WEGNER & SPARROW, 2004). [16]

Adults seeking to understand the lives and experiences of children are frequently confronted by the asymmetries of age, height and verbal skills between them and their interlocutors. In order to bridge these social and communicative distances, investigators have increasingly adopted innovative approaches such as drawing, mapping, diary-keeping, photography and video documentation (JORGENSON & SULLIVAN, 2009). Task-based activities of this kind, which involve young children as active participants in the research process, are not only more enjoyable for them than traditional methods, but are also assumed to enhance their ability to communicate their perspectives to the adult researcher. Furthermore, children's rights have become a significant field of study in recent decades, largely due to the adoption of the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child (UNCRC) in 1989 (REYNAERT, BOUVERNE-DE BIE & VANDEVELDE, 2009).1) Participation is one of the key children's rights, and this methodology could facilitate access to the younger children who are often ignored because they are not able to participate in written and verbal research. [17]

3. Research Questions, Sample and Methods

As we described in Section 2, research in which young children are able to participate actively is yet to become well established. This was the starting point of our project, along with the assumption that diversity is evident everywhere in the different subjective perspectives of children. From these presuppositions, the following three questions arose for us:

How do young children see their world?

How can young children participate in research? Is the photovoice method suitable?

How can young children be involved in group discussions? [18]

The project "Learning Together, Living Diversity" had an international orientation, including contacts established in both Switzerland and Argentina. Kindergarten teachers who wanted to participate with their children were sought out within the framework of a purposive sampling (PATTON, 2002). In order to capture many different child perspectives, the use of maximum variation sampling (ibid.) was chosen. This was achieved through the participation of public and private kindergartens in the two different countries. [19]

Two kindergartens from both countries participated. In selecting the kindergartens and interview partners, we assumed that heterogeneity can be found in any group of people, and will always have different characteristics. Two strategies were used to capture as many different aspects of diversity as possible. Firstly, the international orientation of the project should raise awareness even among very young children that beyond national borders, other countries have completely different languages, foods and ways of life. Secondly, the participation of different kindergartens (in different cities and countries, private or public) should show that the life-worlds of people can be very different depending on their geographical location, living environment and social situation, but despite this diversity there are still numerous commonalities. This research therefore does not undertake a comparison of growing-up conditions in different socio-economic milieus. [20]

As a result of longstanding contacts in Argentina and excellent cooperation with the local partners, the research project was well embedded in the local structures right from the start which simplified the establishment of field access and facilitated data acquisition. In Switzerland, a kindergarten from the Zurich Oberland region with a total of 19 children (ten boys, nine girls) aged four to six participated, as did an institution in the city of Zurich with 13 children (five boys, eight girls) aged three to six years. In Argentina, two kindergartens from Concordia, a town in the province of Entre-Rios, participated with 24 children (16 boys, eight girls) aged four to five and 28 children (16 boys, 12 girls) aged four to five, respectively. A total of 84 children took part in the project, including 47 boys and 37 girls. In both countries, children from private and public institutions participated. The data collection was staggered, as the project implementation in Switzerland and Argentina was delayed. Field research was carried out in Switzerland between March 2017 and July 2017, and in Argentina in October 2017. When selecting the kindergartens and interview partners we assumed, in line with the approach underlying this project, that heterogeneity will exist in any group of people, and always have different characteristics. [21]

The methodological approach was based on the photovoice method which was applied in a slightly modified form adapted to the circumstances. In the project, the children (co-researchers) were provided with special digital photo cameras suitable for children with which they could generate photos of their living environments. These photos served as the basis for the group discussions. Our modified photovoice method adapted VON UNGER's seven steps (2014, pp.71ff.), we added Step 4, as depicted in Figure 1. [22]

After the planning phase (1), the children were introduced to the project topic diversity and learned how to use the camera (2). In this phase a hand puppet was used. A hand puppet is not necessarily part of the photovoice method, but since the method offers room for flexible design, it can be useful in research with children. In this early part of the process, the greatest challenge posed was how to introduce the children to the topic of diversity. We did not use the word diversity, as we assumed the term was too abstract for children of kindergarten age. Instead, the children, the hand puppet, "Lisa," and we researchers explored the concept in mutual exchange, telling each other what they liked or disliked, what we liked to eat, which pets we owned, and so on. In this way the children were made aware that even their best friend can be completely different in certain aspects. [23]

"Lisa" then explained the function of the camera to the children; many of the participating children were familiar with this technique. It should be noted that the children's degree of familiarity with technology depends on many factors. The handling of cameras in particular may be unfamiliar when research is conducted with groups of children from economically and educationally disadvantaged families. The use of a hand puppet had a positive effect during our introduction phase and provided the situation with a playful component (WEISE, 2008). [24]

The photographer/field phase (3) was characterized by the independent work of the children (co-researchers). In order to give them a framework for the photography phase and to keep the assignment open (avoiding the problem of suggestiveness), the children were given easily understandable photo assignments. They were to take photographs of things which were meaningful for them. The photovoice study by RHODES, HERGENRATHER, WILKIN and JOLLY (2008) was used as a guideline by us in order to create open guiding questions. [25]

Another challenge lay in limiting the amount of photos taken by the children. Some took a large number of photos, exceeding the limit we had set. The excess photos ended up being deleted by parents who wanted to abide by the photo limit, effectively destroying what could have been valuable data. Sticker lists were used in which the children could paste one sticker per photo. This proved to be successful in only a few cases, because the children rarely had the list with them when taking pictures. Several children took a large number of photos which complicated the photo selection process. At this point, another solution had to be found. [26]

We therefore interposed a further step (4), namely an initial evaluation of the photos, so that any unusable images could be sorted out. Subsequently, eight favorite photos were selected in a participatory process with the respective child. This selection took place during the regular kindergarten lessons. Then, during the group discussions (5), the children were allowed to select two photos from their eight as key photographs. Finally, these key images were shared and discussed in groups of four to six with the aid of a facilitator-guide (for more methodological details, see VON UNGER, 2014; WANG, 1999). [27]

The issues discussed are addressed in Section 4. "Lisa," the hand puppet, was also present in some of the group discussions, but the effect was very ambiguous which made it impossible to draw conclusions about it. In Argentina in particular the presence of the hand puppet was more distracting than beneficial. The use of a puppet in this context must therefore be further tested. A memory game with which we intend to stimulate speaking and reflection about the theme of diversity will be developed, using the key photographs as well as their statements. The topic diversity is very abstract for children and it may be difficult to discuss it with words alone. The photovoice process provides an opportunity for the children to present this topic visually and to describe their experiences. After all, diversity was obvious in the many photos taken from the children's perspective. As a result, it was possible to jointly explore the subjective meaning of the images. [28]

The setting for the conversations was intended to be as informal as possible. In the ideal setting, researchers and children sit together on small chairs or on the floor in a circle, in a familiar environment (HOPPE, WELLS, MORRISON GILLMORE & WILSDON, 1995; MORGAN, GIBBS, MAXWELL & BRITTEN, 2002; VAUGHN, SCHUMM & SINAGUB, 1996). A total of 19 group discussions were conducted: nine of them in Switzerland, and ten in Argentina, with four to six children in each group taking part. The design of the discussions was based on VOGL (2005, 2019), who provided a practical overview of the special features and challenges of interviews and group discussions with children. The key to successful interviews with children is the selection of the right experiential topics and familiar forms of expression. As in conversational situations in general, verbal, interactive and cognitive skills play a central role—however, VOGL (2019) emphasized that children's ability to conduct conversations is often underestimated. According to this author, particular challenges when performing such interviews include the area of authority and generational relations, the effects of social desirability and the interpretation of acquired data. The author pointed out that younger children in particular may have a tendency to say "yes," and that their attention span may be short. We have taken up this advice, and designed our conversational situations to be as child-friendly as possible: the hand puppet was employed to avoid the authority gap and to give the situation a playful character, the duration of the conversations was based on the concentration span of the group, an attempt was made to initiate conversations among the children to avoid "yes"-answers as far as possible, and so on. In addition, where possible the discussions were conducted in places known to the children in order to minimize the potential for distraction. Since the conversations were based on photos taken by the children themselves, the children were mostly motivated, and the photos stimulated conversation. The group discussions were recorded using both audio and video to enable transcription of the conversations afterwards. Such discussions are demanding and require participants to have certain linguistic and social skills (VOGL, 2005). This raises the question of whether group discussions with young children are possible at all, or at what age they become possible, appropriate and useful. [29]

The superiority in numbers of the children was intended to reduce the imbalance between them and the adult researcher (NENTWIG-GESEMANN, 2002). The photos mostly served as narrative aids and triggers for conversations on certain topics which did not necessarily have a photo reference. No discussion rules were given, in order to promote the self-running nature of the discussion and the production of narrative episodes (SCHÜTZE, 1987). The children were given as much opportunity as possible to participate in the discussions. Questions from the interviewer often related to the topics addressed by the children or the photos. In situations in which the flow of conversation came to a standstill, questions following the SHOWED model were used (SHAFFER, 1984; RHODES et al., 2008, p.161).2) [30]

In the project we focused primarily on the process of researching with children using photovoice, and on the memory game as a final goal of the project. We were less concerned with analyzing of the content of the group discussions (some examples of which are illustrated below). Accordingly, we did not aim to develop a theory of how young children see their world, but rather asked how children can be integrated into participatory research and discussions. [31]

We showed great interest in what the children had said about the photos they had taken, but not in the sense of a rigorous data analysis. In order to conduct this "rough" but theory-driven analysis of the transcripts, we decided to orientate the grounded theory methodology (GTM) originally developed by GLASER and STRAUSS (2010 [1967]). It is important to note that one specific and distinct grounded theory (GT) does not exist—rather, an original methodology has been positioned, interpreted and implemented differently by researchers during the course of its development. For example, a fundamental difference in content exists between the very systematic GT by STRAUSS and CORBIN (1990) and the more positivistic GT approach by GLASER (2002), who argued it is advisable to enter the cognitive process without a broad prior knowledge of the object of research, and who pointed out why, in his view, GT is not constructivist. Later variants of GT have emerged through the differentiated work of former students of STRAUSS and GLASER (e.g., BÜCKER, 2020; VOLLSTEDT & REZAT, 2019). Central figures include CLARKE (2005), who argued for a postmodern orientation of the GT research style, and CHARMAZ, whose "Constructing Grounded Theory" (2006) clearly contrasts with that of GLASER (see also MEY & MRUCK, 2011). In spite of their differences, these varieties are characterized by the shared general direction of their data analysis component. [32]

We should emphasize that, in this article, no particular orientation of GT was intended; we were guided only by the method's basic orientation, namely the first step of the coding procedure, to elaborate our categories. In our evaluation, the complex procedure of GTM was not followed. Instead, we teased out relevant themes from the material in accordance with open coding and, with the GTM as a guideline, depicted the themes mentioned in different conversations and their relationship to each other. A more thorough application of the complex method of Grounded Theory, employing axial and selective coding on the data material in addition to open coding after STRAUSS and CORBIN (1990), would have led to many more insights. Generally, we believe that GTM lends itself well for use in participatory research (see e.g., SCHAEFER, BÄR & THE CONTRIBUTORS OF THE RESEARCH POROJECT ElfE, 2019). While analyzing the children's conversations, the GTM was framed for the first step of open coding in terms of an initial textual approach. [33]

Leaning towards and orientating ourselves towards that method was the most expedient approach, because rather than apply existing concepts to the data, we sought to work inductively and create codes, study the data and briefly define elements of the children's statements. The conversations were read carefully several times, analyzed in smaller extracts, and dissected into units of meaning. During open coding, codes were assigned to these units. This step of analysis was accompanied by the writing of memos in order to record reflections on the codes. Initially, several transcripts were open-coded simultaneously in this way by several researchers. The emergent codes were then compared and findings discussed. It quickly became apparent that many of the themes that were interesting and moving to the children were present in almost all of the conversations, regardless of whether the conversation took place in Switzerland or Argentina. [34]

After analyzing the children's narratives, these similar descriptions were grouped together based on the repetition of key topics, words or phrases. Similar to other inductive analyses, these groupings were then combined into more general conceptual categories. It became clear which topics overlapped. This, in turn, was an indication of which elements of the narrative were related and how. In this way, we were able to identify the categories in Table 1 and analyze in the contexts in which they appeared. The following section 4 is intended to give an idea about the topics children talked about (Table 1) and to provide an exemplary insight based on quotations (Table 2). [35]

Since a detailed presentation of the results would go beyond the scope of this article, we address the research questions briefly and concisely below, and present some examples of children's statements. [36]

4.1 How do young children see their world?

In order to understand how young children see their world, the main topics mentioned by the children are outlined in Table 1. Many of the children had approached the research task with the idea of creating a kind of inventory of what was in their immediate environment and what was important to them in a positive way. Excitingly, the subjects photographed by the children from Argentina and Switzerland were quite similar. For example, several children took pictures of their pets, favorite foods, or toys and books which meant something special to them. New satchels which indicated the coming transition to primary school were photographed by several children. Various children took photos which showed their family, and some also took pictures of objects that indicated leisure activities (a basketball, a football, a dance dress, a bicycle, and inline skates). Several of them took pictures of the television screen showing a series they liked; it became apparent that characters from animated films also played an important role in the lives of children. Characters from the films Frozen3) and Angry Birds4) were especially popular, alongside others from the Ninja Turtles5) and from Spiderman6). The photos also included pictures of characters, backpacks and bed linen showing subjects from these films. In the conversations it emerged that the contents of the cartoons were part of the children's common knowledge. It was also noticeable that pets played a crucial role in children's lives. [37]

The children's statements made it possible to depict networks of the children's life-worlds and to identify the connections between the individual topics. Very similar topics were discussed regardless of the country and kindergarten.

|

Pets |

Pets and animals were mentioned in all groups without exception. They often appeared in connection with the possessive pronoun "my," but also in comparison (who is taller or faster, barks louder, jumps higher, etc.). Mostly dogs were named, then cats and rabbits, and sometimes (in Argentina) parrots and horses. |

|

"Dialogue on a topic" and "Making contact" |

The analysis of the conversations required some differentiation of communication between the children. Therefore these two themes emerged: The first, "dialogue on a topic," was assigned to a text passage when a dialogue on a topic arose between the children which was mainly characterized by ego messages without the children responding to each other, asking questions or explicitly talking to each other. Secondly, "making contact" meant that the children were actively interacting with each other, asking questions about the photos or reacting to statements. Depending on the topic, more or less "contacts" were made. It was observed that "making contact" took place when, based on shared knowledge, an exchange of content on the topic was possible (e.g., shared experiences such as a birthday party, or generally known facts such as the content of an animated film). |

|

Adult influence |

Children sometimes made statements expressing the influence of adults (e.g., on the purchase of expensive items or on gender). |

|

Reaction to recording device and camera |

Children in many groups reacted similarly to the technique. They often looked curiously at the equipment and asked what it was. Sometimes they wanted to touch the recording device or speak into it. They would also wave into the camera, show their pictures, or admonish each other to look into the camera when speaking, so that the camera could record what was said. |

|

Media |

The media were of great importance in the everyday life of the children. Some of the photos showed a TV screen with a current TV series; other pictures presented different characters (such as illustrations of popular cartoon characters). Since these series and characters were familiar to many children, several conversations took place on such topics. |

|

Egocentrism, comparison and ownership |

Egocentrism is a developmental psychological term which explains that small children in particular have difficulty in adopting another's point of view and judging independently of their own (PIAGET, 1974 [1955]). This phenomenon became clear in the interviews. The children tried to distinguish themselves from others by introducing various elements during the interview that showed that they were better, louder, faster or the same as the others. In most cases, however, the words of the other child were hardly ever mentioned. |

|

Family and home |

Family members, relatives and siblings played an important role for the children, who often referred to them in the interviews. The family was a reference point for the children. They also showed where they were living with their family. |

|

Toys |

In the eyes of these children, toys were of particular importance. Subjects included dolls, stuffed animals, play figures, Lego, small kitchens, toy instruments, bicycles, trampolines, swings, inline skates, hobbyhorses, and others. Also included in the photographs, but rather rarely, were board games which can be played according to rules. Stuffed animals were also popular, as were play figures from well-known cartoon series or movies. |

|

Food |

Food was regularly photographed and often triggered conversations (who likes what, what was photographed, etc.). |

|

Dispute |

The topic of dispute appeared mainly in the context of siblings. Most of the children had older siblings with whom they argued from time to time. However, the description of the conflict was always given with a smile. |

|

Death |

Death was a topic that the children often dealt with in connection with their pets. In four out of seven interviews in Switzerland, a deceased pet was reported. |

|

Leisure and special events |

Leisure time and events seemed to have a special relevance for children. Many reported trips or special events (e.g., visits to the zoo, trips to the lake or to the city center, birthdays) as well as leisure activities (e.g., playing soccer, dancing). The narrative was often linked to the topic of family. |

Table 1: Topics the children wanted to talk about [38]

In addition to the content of the topics, two kinds of dialogues were identified: 1. "dialogue on a topic" and 2. "making contact." Taken together, all the categories revealed what is important in the eyes of the participating children. The children's pictures showed empirical truths, and the many different photos expressed lived diversity. We found that the pictures, when viewed in relationship to the narratives which accompanied them, afforded further insights into the production process and the real-life situations, and were thus uniquely effective in revealing children's points of view. [39]

The following examples (Table 2) of short statements from the children are translated into English by us, from the original Swiss German (Switzerland) and Spanish (Argentina). In Switzerland some children participated who had other native languages (Russian, English, and Spanish), but they expressed themselves mostly in Swiss German.

|

Thematic overlap "Pets" and "Death" (Julia7), 5 years, Switzerland) I = Interviewer J = Julia

|

J: This is Haki. But he died. He didn't like playing with balls. But he liked to go for a walk. Mommy cried when Haki died, and Daddy cried too. Not me. My brother always said (to the parents): Stop crying. I: Yes, when you have such an animal for a long time, it belongs a little bit to the family. J: They'd had him longer than us (means herself and her brother). They already had Haki before we were born. When we had not yet lived. They had him for a long time, twice as long as we are alive. They said they would not buy another. My brother always says "buy one again" and she (the mother) says no. |

|

Thematic overlap "Making contact" and "Toy" (Dennis, 6 years, Switzerland) I = Interviewer P = Puppet D = Dennis F / J / G = other children

|

I: What did Dennis photograph? P: A helicopter? And a radio? D: Yes. F: A real helicopter? J: This is just a robot helicopter, right? D: No, this is ... F: Is it actually a real one? J: A toy! D: No, it's just metal. It's just ... G: It can fly! D: It can't really fly. G: I know, but I'm telling you, it's a plane. |

|

Thematic overlap "Making contact" and "Toy" (Pia, 5 years, Argentina) P = Pia T / V = other children

|

P: This is my doll Pio, who sleeps with me every night He is very dirty, incredibly dirty and I like this flower, this rose (shows the flower on Pio's clothes). This is my bed which Pio lies on. Sometimes I go on vacation with my Pio, because I love him very much. T: Let me see! V: Pia? P: Pio! V: Pio is a man? P: Yes, because the Harlequins are men. |

|

"Leisure and special events" (Martina, 6 years, Switzerland) M = Martina

|

M: The gymnastic dress. I am in the gymnastics club. My sister is also in the gymnastics club and she is in the level K2.8) Well, we sometimes have floor gymnastics and high bar. |

|

"Adult influence" (Ivo, 6 years, Argentina) Int = Interviewer I = Ivo M / C = two girls

|

Int: Let me see the backpack you have there. Why did you take a picture of it? I: Because I like it. Int: What do you need it for? I: To go to kindergarten. M: And you like Spiderman! I: No! No, I actually wanted to choose a football backpack, but there was none. C: I wanted a football backpack! I (a bit loud and indignant): You wanted a football backpack, a backpack for boys! I wanted a football backpack! |

|

"Family and home" (Vincent, 5 years, Switzerland) V: Vincente

|

V: There in front (pointing to his picture with his finger) if you keep walking like this, there is a carpet with a small sofa. And then the carpet there is so black and then there is a small entrance with a small fireplace and then there is a small carpet and then there is a big long carpet. |

Table 2: Photos and related statements made by the children [40]

One might ask what these photos and statements have to do with diverse experiences. They have little to do with it in the direct sense, but the photos combined with the statements showed what the children like and partly also how they live. The children can see that other children may like different things, speak a different language at home, or may be afraid of dogs. Talking together about the photos creates the possibility to talk about diversity in an authentic way without having to use the abstract word. Diversity is understood as something that is ever-present. However, we could see that children—regardless of where they live—have things in common, e.g., riding a bicycle. The idea of using photos to start and develop a conversation about diversity originated in the idea of avoiding stereotypes and demonstrating that there is no "we here in country x and those there in country y"—rather, diversity and similarities transcend national borders and differences are a reason for exclusion rather than enrichment. At the same time, the children are able to discover this diversity themselves through conversation and photos. The next step involved processing the images as a memory game which researcher can use in the future as a stimulus to talk with children about diversity. The statements of the children who took the pictures can be used. [41]

4.2 How can young children participate in research? Is the photovoice method suitable?

As we found, kindergarten-age children can participate adequately in participatory research if the framework conditions are adapted to them. In this particular case, we observed that most of the participating children were well acquainted with the use of a digital camera and they took great pleasure in the act of taking photographs. However, this factor depends largely on the overall conditions in which children grow up. It can therefore be assumed that the implementation of a photovoice project requires introduction in the form of helping children use the technology depending on the group of children involved. If the research is conducted with groups of people for whom the use of the technology is new and unfamiliar, the implementation is expected to pose further challenges. [42]

New technologies come with greater possibilities for future participative research, although a great deal of care is necessary in handling the sensitive data and avoid undesirable dissemination. We see potential for future research particularly in the participatory selection of photos. In this project, the selection took place in an informal setting in kindergarten which proved very successful: in each case, an academic researcher sat down with children and their cameras in the same room where the other children enjoyed normal kindergarten lessons. This gave the situation a spontaneous element, and natural groups were formed, sometimes with several children looking into the camera. The process resulted in highly interesting comments and conversations. [43]

4.3 How can young children be involved in group discussions?

Children may be effectively involved in group discussions, but some particularities should be taken into account. VOGL (2005, p.30) pointed out the importance of a natural situation and communicativeness as well as openness as central characteristics of the qualitative approach in group discussions. Our experiences affirmed VOGL's statements, showing that the familiarity (and thus naturalness) of the room plays an important role. In one case in Argentina, for example, conversations at one school took place in the library, and at another in the principal's office; the potential for distraction was great, and the restlessness correspondingly higher. If the conversations took place in a room known to the children (which was the case in Switzerland in both institutions), the surroundings were more familiar, more natural and contained less potential for distraction. [44]

In contrast to pure interview forms, our group discussions also showed group dynamic processes (ibid.). Depending on the size and composition of the group, these processes vary; accordingly, it became apparent that the success and significance of group discussions depend very much on the willingness of the group members to participate. VOGL conducted group discussions with children from 1st to 9th grade and noticed that "the participants became calmer with increasing age: they talked less chaotically, making it more comprehensible, the breaks increased, they could concentrate longer and sat quietly on their chairs. But they were also decreasingly willing to express themselves" (p.57; our translation).9) VOGL first led discussions with groups of ten children, but then reduced the size of the groups to eight. Our experiences here are based on VOGL's observations. In this project, we found that the group size should be somewhat smaller for children aged four to six, namely a maximum of six children, or better only four or five. However, this may not be the same in all cases, as the characteristics of the children's group (motivation, joy in telling stories and listening, etc.) also has a significant influence on the discussion situation. [45]

Directly related to this, we observed a varying duration of concentration which corresponds to the data available in the literature. For example, as the authors of the "Merkblatt 'Konzentration'" [Factsheet "Concentration"] published by the Canton of Zug (Directorate of Education and Culture Office of Community Schools) stated: "The older the child, the longer she/he can concentrate. For children between five and seven years of age, the average is about 15 minutes; for seven to ten year olds about 20 minutes, for ten to twelve year olds about 25 minutes" (KANTON ZUG, 2014, p.1; our translation).10) Our experience has shown that for children aged four to five, a concentration time of just under ten to maximum 15 minutes seems realistic. [46]

The success of the hand puppet "Lisa" varied, and was higher in the introductory phase as opposed to the group discussions. The hand puppet proved to be helpful during the introductory phase and as an "icebreaker" to initiate contact with the children. Various other ambiguous effects were observed during the group discussions. From our point of view, the use of the hand puppet during the interviews was evaluated rather positively in some groups and rather negatively in others. In Argentina in particular, the puppet was rather distracting, with children tugging at it and putting their hands in its mouth. Moreover, the puppet required a high level of skill from the adult interviewers, as their hands were "trapped" in the puppet and the interviewer had to combine two roles (and maintain their separation in terms of vocal pitch as well as choice of words and gestures). These results coincide with those of ANDRESEN and SEDDIG, who evaluated video recordings of conversations with children in the presence of a hand puppet: "Particularly in the video recordings it became clear that the children reacted indifferently to the doll. The doll often caused irritation [...] Furthermore, the children talked partly to the doll, but partly also to the researcher who played it" (2014, p.292; our translation).11) In conclusion, the authors formulated "[...] that it should be carefully examined, tested and reflected upon how individual methods and applied methods affect children of different ages and what unintended effects the use of a hand puppet can have" (ibid.; our translation).12) [47]

With regard to the content of the conversations, children between four and six years old often talk from a first-person perspective and only start a common conversation in the form of a longer dialogue if the content on a topic is identical (e.g., what the interlocutors experienced together, or the content of an animated film). PIAGET emphasized that the pre-school and kindergarten age groups are characterized by the overcoming of "verbaler Egozentrismus" [verbal egocentrism] (1974 [1955], p.75; our translation). Children increasingly acquire the ability to recognize the perspective of their counterpart and to adapt their own speech and actions accordingly. [48]

According to MEAD (1973 [1934]), the ability to adopt perspective is the prerequisite for cooperative behavior. WELTZIEN stated: "In a mutual interactional confrontation, the perspective of the other is repeatedly taken. In order to create a reciprocity of perspective, common knowledge basis and the assumption that these knowledge bases also exist in the other are central premises" (2012, p.143; our translation).13) Following these explanations, one reason for the rather short conversations among young children might be that they have a relatively small store of shared general knowledge. Topics that were shared by several children were essential during our group discussions. The subjects photographed by the children and considered important were found mainly in their close family environment (family members, pets, toys, familiar places, TV series, etc.). It was noticeable that longer dialogues occurred principally when the subject was a mutual experience of several children. For instance, if several children had played with a child's dog at the same time, or if the children celebrated a birthday together, the shared experiences formed a common store of knowledge which enabled a conversation in which the children interacted with each other. By the same token, the children found it difficult to develop dialogue when the topic could be linked to individual experiences which were not shared with the rest of the group. Discussions on the topic of pets, for example, often led to each child talking about his/her experiences with a pet from their own perspective. The children hardly ever asked about the pets of others or commented on statements made by other children. Furthermore, conversations included conspicuously frequent use of comparatives and superlatives in connection with ego statements (whose dog runs faster, barks louder, etc.). [49]

The aim of the group discussions, of course, was not to ask the children "what do you understand by diversity," but to let them discover in their immediate everyday lives how different and diverse their friends were in certain respects, and how similar in others. The memory game that will ultimately emerge from the photos will aim to encourage the children to think about themselves and their fellow humans. For example, why did a child take a picture of a spider? Does he/she like spiders? Or is he/she afraid of it? Would I photograph a spider too? Why or why not? [50]

In this part, we will present the main findings of the photovoice project "Learning Together, Living Diversity" with children aged four to six. These may be split into four areas: the planning an introduction phase; cooperation with children and photography phase; group discussions; general conclusion regarding the photovoice method. [51]

5.1 Planning and introduction phase

It may be important to deal with the topic at the center of the project extensively in advance, especially if it is something more abstract like "diversity." What does diversity mean to the researchers? And for the children? How can diversity be understood? How does the topic become relatable for the respective groups?

The introductory event, in which researchers meet the children and introduce them to the topic and how the camera works in a playful way, is a good way to initiate contact. The hand puppet "Lisa" is particularly beneficial as an "icebreaker."

If possible, it would be ideal to work with the children on the respective topic over a longer period of time, e.g., by integrating it into the kindergarten curriculum during the project. [52]

5.2 Cooperation with the children and photography phase

Children are very motivated to participate in such a project, and especially to use a camera on their own which is seen as a special privilege.

A major challenge is ensuring the children keep a certain number of photos after taking them. Some of the children take a huge number of pictures which make the process of photo selection difficult. Parents may delete photos in order to abide by the limit, but deleting any photos is undesirable. We should therefore determine how to limit the number of photos taken by the children.

The open photo assignments employing the acronym SHOWN have proven to be successful. No concrete examples are given of what might be photographed, thus avoiding suggestiveness.

Natural groups and spontaneous conversations may be formed between the children about the photos when the process of the photo selection takes place during the lessons in normal kindergarten life. It seems desirable to conduct conversations in as natural an environment as possible in future group discussions. [53]

5.3 Group discussions and talk about diversity

The joint work of children and researchers during the picture-taking and photo selection phase enables all participants to get to know each other, which in turn has a positive effect on the process of group discussions.

While the hand puppet is beneficial at the introductory event, ambiguous effects such as boxing and putting hands into the mouth of the puppet mean that they may be disadvantageous for the group conversations (especially in Argentina).

Experience has shown that a group size of three to a maximum of six participants is appropriate for children of kindergarten age. However, as the age of the individual children as well as their character have a significant influence on the dynamics of the group, the ideal size of a group will vary. Managing this variability may be challenging.

The duration of the group discussions varies depending on its composition. We conclude that an average duration of 10-15 minutes (max. 20 minutes) should not be exceeded.

The group discussions are often dominated by self-statements on a topic.

Longer conversation sequences mainly occur when the subject of the conversation forms part of a shared body of knowledge (due to shared experiences, such as playing a game or celebrating a birthday together). Children rarely ask each other further questions if they are not familiar with the topic the other child is talking about. They are more likely to adapt statements to their own experiences and continue the conversation based on their subjective perspective.

Discussing the topic of diversity is challenging, but if diversity is expressed in the photographs in a way that is close to everyday life, the children are able to establish connections, discover similarities and differences, and thus engage in the topic without naming it.

The photographs taken by the children support the conversations. They show a stimulating effect and make it easier to start talking (even about topics that are not directly related to the photo content). Therefore, it can be conjectured that image-supported interviews within this setting have great potential.

As the images are yet to be used in further research (the development of a memory game), the process of "talking about diversity" using the photo cards is yet to be fully evaluated. It remains to be seen whether the photo cards are suitable for use as a narrative stimulus and for the stimulation of philosophical discussions about diversity. [54]

5.4 General conclusion regarding the photovoice method

The project "Learning Together, Living Diversity" has shown us that a photovoice project with young children can be undertaken efficiently. It remains important that adults broaden their perspective and face the children without expectations and assumptions. The children can only be guaranteed the individual space they need to tell us what is important to them if they are treated with openness. Even if their pictures seem strange at first, it is important to listen and look carefully in order to grasp the meaning. Sometimes this requires considerable restraint on the part of the adults.

Depending on their milieu, young children may already be highly adept at handling the technology. The amount of explanation and support in this area may thus vary significantly. It is certain, however, that modern technology may be used in participatory research with young children.

Methodological concepts must meet different requirements depending on the age of the children.

The photovoice method was proven to be particularly appropriate for the involvement of young children in the research process due to its openness and the possibility of flexible design. The same applies to the group discussions as part of a photovoice project.

In sum, our project has revealed that research with young children always requires a specific procedure adapted to the situation, open and flexible in order to make room for the children's abilities. The photovoice method corresponds to this requirement. [55]

Further research with young children using photovoice and other participatory research methods is still required. For the development and design of educational materials in the future, a more comprehensive and accurate understanding of children's perspectives is of enormous importance. Furthermore, children have the fundamental right to be heard and to have the opportunity to express themselves about issues that concern them. This avenue of research seems to be more than fitting in the coming decades. [56]

We would like to thank the Stifterverband der deutschen Wissenschaft (Leopold Klinge Foundation, which supported this project financially. We would also like to acknowledge Guillermina CHABRILLON (Universidad Nacional de Entre Rios, Argentina), who organized the fieldwork in Argentina. Further thanks go to the institutions in Switzerland and Argentina which participated in the project. Katja MRUCK from FQS was always there to assist and advise us.

1) See https://www.ohchr.org/Documents/ProfessionalInterest/crc.pdf [Accessed: August 15, 2020]. <back>

2) What do you see here? What is really happening here? How does this relate to our lives? Why does this concern, situation, strength exist? How can we become empowered through our new understanding? What can we do? <back>

3) Frozen is an animated movie produced by Walt DISNEY. It tells the story of a fearless princess who sets off on a journey alongside a rugged iceman, his loyal reindeer, and a naive snowman to find her estranged sister, whose icy powers have inadvertently trapped their kingdom in eternal winter. <back>

4) Angry Birds is an animated action movie created by the Finnish company Rovio Entertainment. It focuses on multi-colored birds who try to save their eggs from green pigs, their enemies. <back>

5) The Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtlesare four fictional teenage superhero turtles. From their home in the sewers of New York City, they battle petty criminals, evil overlords, mutated creatures, and alien invaders while attempting to remain hidden from society. <back>

6) Spider-Man is a fictional superhero. In the stories, he is the alias of Peter Parker, an orphan raised by his Aunt and Uncle in New York City after his parents died in a plane crash. His origin story has him acquiring spider-related abilities after a bite from a radioactive spider; these include clinging to surfaces, superhuman strength and agility, and detecting danger with his "spider-sense." <back>

7) The names of the children are anonymized. <back>

8) K2 means "Category 2." The girl wants to say that her sister is already a little better in gymnastics. <back>

9) Original quote in German: "[...] dass die Teilnehmer mit zunehmendem Alter ruhiger wurden: Sie sprachen weniger durcheinander, dadurch war weniger unverständlich, der Pausenanteil stieg, sie konnten sich insgesamt länger konzentrieren und saßen auch still auf ihren Stühlen. Aber sie waren immer weniger bereit, sich zu äußern." <back>

10) Original quote in German "Je älter das Kind, desto länger kann es sich konzentrieren. Bei Kindern zwischen 5 und 7 Jahren sind das im Durchschnitt ca. 15 Minuten, bei 7 bis 10 jährigen ca. 20 Minuten, bei 10 bis 12 jährigen ca. 25 Minuten." <back>

11) Original quote in German: "Insbesondere in den Videoaufnahmen kam deutlich zum Vorschein, dass die Kinder indifferent auf die Puppe reagierten. Die Puppe sorgte oft für Irritationen [...]. Des Weiteren sprachen die Kinder teilweise mit der Puppe, teilweise aber auch mit der Forscherin, die sie spielte." <back>

12) Original quote in German: "[...] dass sorgsam zu prüfen, zu erproben und zu reflektieren (sei), wie einzelne Methoden und eingesetzte auf Kinder unterschiedlichen Alters wirken und welche nicht intendierten Effekte etwa der Einsatz einer Handpuppe haben kann." <back>

13) Original quote in German: "In einer auf Gegenseitigkeit beruhenden interaktionalen Auseinandersetzung wird immer wieder die Perspektive des anderen eingenommen. Um eine Reziprozität der Perspektive herzustellen, sind gemeinsame Wissensbestände und die Annahme, dass auch bei dem jeweils anderen diese Wissensbestände vorhanden sind, zentrale Prämissen." <back>

Adolphs, Ralph; Damasio, Hanna; Tranel, Daniel; Cooper, Greg & Damasio, Antonio R. (2000). A role for somatosensory cortices in the visual recognition of emotion as revealed by three-dimensional lesion mapping. The Journal of Neuroscience: The Official Journal of the Society for Neuroscience, 20(7), 2683-2690.

Amit, Elinor; Wakslak, Cheryl J. & Trope, Yaacov (2013). The use of visual and verbal means of communication across psychological distance. Personality & Social Psychology Bulletin, 39(1), 43-56.

Andresen, Sabine & Seddig, Nadine (2014). Methoden der Kindheitsforschung. In Rita Braches-Chyrek, Charlotte Röhner, Heinz Sünker & Michaela Hopf (Eds.), Handbuch Frühe Kindheit (pp.289-298). Opladen: Budrich.

Bergold, Jarg & Thomas, Stefan (2012). Participatory research methods: A methodological approach in motion. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung / Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 13(1), Art. 30, http://dx.doi.org/10.17169/fqs-13.1.1801 [Accessed: July 10, 2020].

Bücker, Nicola (2020). Kodieren, aber wie? Varianten der Grounded Theory Methodologie und der qualitativen Inhaltsanalyse im Vergleich. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung / Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 21(1), Art. 2, https://doi.org/10.17169/fqs-21.1.3389 [Accessed: December 10, 2020].

Charmaz, Kathy (2006). Constructing grounded theory. A practical guide through qualitative analysis. London: Sage.

Christensen, Pia & James, Allison (2008). Research with children. Perspectives and practices (2nd ed.). New York, NY: Routledge.

Clark, Alison & Moss, Peter (2011). Listening to young children. The mosaic approach. London: National Children's Bureau.

Clarke, Adele E. (2005). Situational analysis: Grounded theory after the postmodern turn. London: Sage.

Collier, John (1957). Photography in anthropology: A report on two experiments. American Anthropologist, 59(5), 843-859.

Csikszentmihalyi, Mihaly (1993). Why we need things. In Steven D. Lubar & W. David Kingery (Eds.), History from things: Essays on material culture (pp.20-30). Washington D.C.: Smithsonian Institution Press.

Davis, John; Watson, Nick & Cunningham-Burle, Sarah (2008). Disabled children, ethnography and unspoken understandings: The collaborative construction of diverse identities. In Pia Christensen & Allison James (Eds.), Research with children. Perspectives and practices (2nd ed., pp.220-238). New York, NY: Routledge.

Emde, Robert N.; Wolf, Denni & Oppenheim, David (Eds.) (2003). Revealing the inner worlds of young children: The MacArthur story stem battery and parent-child narratives. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Feichter, Helene (2015). Schülerinnen und Schüler erforschen Schule. Möglichkeiten und Grenzen. Wiesbaden: Springer VS.

Flick, Uwe (2011). Designing qualitative research. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Fuhs, Burkhard (1999). Die Generationenproblematik in der Kindheitsforschung. In Michael-Sebastian Honig, Andreas Lange & Hans Rudolf Leu (Eds.), Aus der Perspektive von Kindern? Zur Methodologie der Kindheitsforschung (pp.153-161). Weinheim: Juventa.

Glaser, Barney G. (2002). Constructivistic grounded theory?. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung / Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 3(3), Art. 12, https://doi.org/10.17169/fqs-3.3.825 [Accessed: December 10, 2020].

Glaser, Barney G. & Strauss, Anselm L. (2010 [1967]). Grounded Theory: Strategien qualitativer Forschung (3rd ed.). Bern: Huber.

Gomez, Ricardo (2020). Photostories: A participatory photo elicitation visual research method in Information Science. Qualitative and Quantitative Methods in Libraries (QQML), 9(1), 47-63, http://www.qqml.net/index.php/qqml/article/view/588/551[Accessed: August 19, 2020].

Heinzel, Friederike (2012). Qualitative Methoden der Kindheitsforschung. Ein Überblick. In Friederike Heinzel (Eds.), Methoden der Kindheitsforschung. Ein Überblick über Forschungszugänge zur kindlichen Perspektive (pp.22.35). Weinheim: Beltz Juventa.

Hoppe, Marilyn J.; Wells, Elizabeth A.; Morrison, Diane M.; Gillmore, Mary R. & Wilsdon, Anthony (1995). Using focus groups to discuss sensitive topics with children. Evaluation Review, 19(1), 102 114.

Jorgenson, Jane & Sullivan, Tracy (2009). Accessing children's perspectives through participatory photo interviews. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung / Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 11(1), Art. 8, http://dx.doi.org/10.17169/fqs-11.1.447 [Accessed: August 19, 2020].

Kanton Zug (2014). Merkblatt "Konzentration". Zug: Direktion für Bildung und Kultur, Amt für gemeindliche Schulen Schulpsychologischer Dienst, https://www.zg.ch/behoerden/direktion-fur-bildung-und-kultur/amt-fur-gemeindliche-schulen/inhalte-ags/schulpsychologischer-dienst/publikationen/downloads/mb_konzentration.pdf/view [Accessed: October 23, 2019].

Malafouris, Lambros (2013). How things shape the mind. Cambridge, MA: MIT University Press.

Margolis, Eric & Pauwels, Luc (Eds.) (2011). The Sage handbook of visual research methods. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Mead, George H. (1973 [1934]). Geist, Identität und Gesellschaft – aus der Sicht des Sozialbehaviorismus. Frankfurt/M.: Suhrkamp.

Mey, Günter & Mruck, Katja (2011). Grounded-Theory-Methodologie: Entwicklung, Stand, Perspektiven. In Günter Mey & Katja Mruck (Eds.), Grounded Theory Reader (pp.11-48). Wiesbaden: VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften.

Mögel, Maria (2019). Wie erleben platzierte Vorschulkinder die Zugehörigkeit zu ihren komplexen Beziehungswelten? Forschen mit dem Geschichtenstammverfahren der MacArthur Story Stem Battery. In Ingeborg Hedderich, Jeanne Reppin & Corinne Butschi (Eds.), Perspektiven auf Vielfalt in der frühen Kindheit. Mit Kindern Diversität erforschen (pp.299-313). Bad Heilbrunn: Klinkhardt.

Morgan, Myfanwy; Gibbs, Sara; Maxwell, Krista & Britten, Nicky (2002). Hearing children's voices: Methodological issues in conducting focus groups with children aged 7-11 years. Qualitative Research, 2(1), 5-20.

Moser, Heinz (2005). Visuelle Forschung – Plädoyer für das Medium Fotografie. MedienPädagogik, 1(4), https://www.medienpaed.com/article/view/57/57 [Accessed: August 17, 2020].

Nentwig-Gesemann, Iris (2002). Gruppendiskussionen mit Kindern: die dokumentarische Interpretation von Spielpraxis und Diskursorganisation. Zeitschrift für qualitative Bildungs-, Beratungs- und Sozialforschung, 3(1), 41-63.

Nykiforuk, Candace I.J.; Vallianatos, Helen & Nieuwendyk, Laura M. (2011). Photovoice as a method for revealing community perceptions of the built and social environment. International Journal of Qualitative Methods 10(2), 103-124, https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/pdf/10.1177/160940691101000201 [Accessed: October 17, 2020].

Paivio, Allan (1990). Mental representations. A dual coding approach. New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

Patton, Michale Quinn (2002). Qualitative evaluation and research methods (3rd ed.). London: Sage.

Pfeiffer, Constanze (2013). Giving adolescents a voice? Using videos to represent reproductive health realities of adolescents in Tanzania. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung / Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 14(3), Art. 18, http://dx.doi.org/10.17169/fqs-14.3.1999 [Accessed: July 10, 2020].

Piaget, Jean (1974 [1955]). Die Bildung des Zeitbegriffs beim Kinde. Frankfurt/M.: Suhrkamp.

Reynaert, Didier; Bouverne-de Bie, Maria & Vandevelde, Stijn (2009). A review of children's rights literature since the adoption of United Nations Conventions on the rights of the child. Childhood, 16(4), 518-534.

Riecken, Ted; Strong-Wilson, Teresa; Conibear, Frank; Michel, Corrine & Riecken, Janet (2004). Connecting, speaking, listening: toward an ethics of voice with/in participatory action research. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung / Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 6(1), Art. 26, http://dx.doi.org/10.17169/fqs-6.1.533 [Accessed: August 10, 2020].

Rhodes, Scott D.; Hergenrather, Kenneth C.; Wilkin, Aimee M. & Jolly, Christine (2008). Visions and voices: Indigent persons living with HIV in the southern United States use photovoice to create knowledge, develop partnerships, and take action. Health Promotion Practice, 9(2), 159-169.

Schaefer, Ina; Bär, Gesine & the Contributors of the Research Project ElfE (2019). Die Auswertung qualitativer Daten mit Peerforschenden: ein Anwendungsbeispiel aus der partizipativen Gesundheitsforschung. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung / Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 20(3), Art. 6, http://dx.doi.org/10.17169/fqs-20.3.3350 [Accessed: October 13, 2019].

Schütz, Sandra & Böhm, Eva T. (2019). Forschungsmethodische Vielfalt. Der Mosaic Approach. In Ingeborg Hedderich, Jeanne Reppin & Corinne Butschi (Eds.), Perspektiven auf Vielfalt in der frühen Kindheit. Mit Kindern Diversität erforschen (pp.172-186). Bad Heilbrunn: Klinkhardt.

Schütze, Fritz (1987). Das narrative Interview in Interaktionsfeldstudien: erzähltheoretische Grundlagen, Teil 1. Hagen: FernUniversität Hagen.

Shaffer, Roy (1984). Beyond the dispensary: On giving community balance to primary health care. Nairobi: African Medical and Research Foundation (AMREF).

Strauss, Anselm. L. & Corbin, Juliet M. (1990). Basics of qualitative research: Grounded theory procedures and techniques. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Vaughn, Sharon; Schumm, Jeanne S. & Sinagub, Jane (1996). Focus group interviews in education and psychology. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Vogl, Susanne (2005). Gruppendiskussionen mit Kindern: methodische und methodologische Besonderheiten. ZA Information / Zentralarchiv für Empirische Sozialforschung, 57, 28-60, https://nbn-resolving.org/urn:nbn:de:0168-ssoar-198469 [Accessed: October 10, 2019].

Vogl, Susanne (2019). Mit Kindern Interviews führen: ein praxisorientierter Überblick. In Ingeborg Hedderich, Jeanne Reppin & Corinne Butschi (Eds.), Perspektiven auf Vielfalt in der frühen Kindheit. Mit Kindern Diversität erforschen (pp.142-157). Bad Heilbrunn: Klinkhardt.

Vollstedt Maike & Rezat Sebastian (2019). An introduction to grounded theory with a special focus on axial coding and the coding paradigm. In Gabriele Kaiser & Norma Presmeg (Eds.), Compendium for early career researchers in mathematics education (pp.81-100). Cham: Springer.

von Unger, Hella (2012). Partizipative Gesundheitsforschung: Wer partizipiert woran?. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung / Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 13(1), Art. 7, http://dx.doi.org/10.17169/fqs-13.1.1781 [Accessed: October 23, 2019].

von Unger, Hella (2014). Partizipative Forschung. Eine Einführung in die Forschungspraxis. Wiesbaden: Springer VS.

Wang, Caroline (1999). Photovoice: A participatory action research strategy applied to women's health. Journal of Women's Health, 8, 185-192.

Wang, Caroline & Burris, Mary A. (1994). Empowerment through photo novella: Portraits of participation. Health Education Quarterly, 21, 171-181.

Wang, Caroline & Burris, Mary A. (1997). Photovoice: Concept, methodology, and use for participatory needs assessment. Health Education & Behavior, 24(3), 369-387.

Wegner, Daniel M. & Sparrow, Betsy (2004). Authorship processing. In Michael S. Gazzaniga (Ed.), The cognitive neurosciences (3rd ed., pp.1201-1209), Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Weise, Marion (2008). Der Kindergarten wird zum "Forschungsort" – Das Puppet Interview als Forschungsmethode für Frühe Bildung. Ludwigsburger Beiträge zur Medienpädagogik, 11, 1-10.

Weise, Marion (2019). Es ist noch jemand mit uns hier. Puppet-Interviews in der Forschung mit Kindern. In Ingeborg Hedderich, Jeanne Reppin & Corinne Butschi (Eds.), Perspektiven auf Vielfalt in der frühen Kindheit. Mit Kindern Diversität erforschen (pp.158-171). Bad Heilbrunn: Klinkhardt.

Weltzien, Dörte (2012). Gedanken im Dialog entwickeln und erklären: die Methode dialoggestützter Interviews mit Kindern. Frühe Bildung, 1(3), 143-149.

Wöhrer, Veronika (2017). Rezension: Helene Feichter (2015). Schülerinnen und Schüler erforschen Schule. Möglichkeiten und Grenzen. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung / Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 18(1), Art. 12, http://dx.doi.org/10.17169/fqs-18.1.2758 [Accessed: July 10, 2020].

Corinne BUTSCHI received her M.A. in educational psychology and special education at the University of Zurich in 2015. She is a research assistant at the Institute for Educational Science at the University of Zurich at the Chair of Special Education with the main focus on society, participation and disability. Her research interests include early childhood and participatory research.

Contact:

Corinne Butschi, M.A.

Universität Zürich

Institut für Erziehungswissenschaft, Lehrstuhl Sonderpädagogik: Gesellschaft, Partizipation und Behinderung

Freiestrasse 36, CH-8032 Zürich, Switzerland

E-mail: corinne.butschi@ife.uzh.ch

Ingeborg HEDDERICH studied educational science and special needs education. Since 2011 she holds the chair of special needs education with the main focus on society, participation and disability at the University of Zurich. Her research is focused on early childhood, inclusion, migration, and participatory research, which she realizes in international cooperation with South American countries. Current publication (in German): "Perspektiven auf Vielfalt in der frühen Kindheit. Mit Kindern Diversität erforschen" [Perspectives on Diversity in Early Childhood. Exploring Diversity with Children] (ed. with Jeanne REPPIN & Corinne BUTSCHI, 2019, Bad Heilbrunn: Klinkhardt).

Contact:

Prof. Dr. Ingeborg Hedderich

Universität Zürich

Institut für Erziehungswissenschaft, Lehrstuhl Sonderpädagogik: Gesellschaft, Partizipation und Behinderung

Freiestrasse 36, CH-8032 Zürich, Switzerland

E-Mail: ihedderich@ife.uzh.ch

URL: https://www.ife.uzh.ch/de/research/gpb.html

Butschi, Corinne & Hedderich, Ingeborg (2021). How to Involve Young Children in a Photovoice Project. Experiences and Results [56 paragraphs]. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung / Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 22(1), Art. 5, http://dx.doi.org/10.17169/fqs-22.1.3457.