Volume 21, No. 3, Art. 5 – September 2020

"It's Like the Pieces of a Puzzle That You Know": Research Interviews With People Who Inject Drugs Using the VidaviewTM Life Story Board

John V. Flynn, Claire E. Kendall, Lisa M. Boucher, Michael L. Fitzgerald, Katharine Larose-Hébert, Alana Martin, Christine Lalonde, Dave Pineau,

Jenn Bigelow, Tiffany Rose, Rob Boyd, Mark Tyndall & Zack Marshall

Abstract: The Life Story Board (LSB) is a visual tool used in therapeutic circumstances to co-construct a lifescape that represents the personal, relational and temporal aspects of a person's lived experiences. We conducted a study of the drug use and harm reduction experiences of people who inject drugs through research interviews using the LSB to determine whether it has the potential to enhance qualitative research. Our team included community researchers who were current or former drug users and academic researchers. Interviews were conducted by two community researchers: an interviewer and a storyboarder who populated the LSB.

Results showed that interviewers and participants interacted with the LSB in different ways. The board functioned to situate the interviewers in the interview schedule, whereas participants often used the board as a way to validate or reinforce their life story. Participants expressed a variety of emotional and cognitive responses to the board. Overall, the LSB helped participants focus on their life story to recall specific occasions or incidents and enabled them to gain perspective and make greater sense of their lives. Both participants and interviewers engaged with the LSB in nuanced ways that enabled them to work together to represent the participant's life story.

Key words: Life Story Board; qualitative research tool; research interviews; people who inject drugs; life experience narratives

Table of Contents

1. Introduction

2. Background

2.1 Studies on the impact of drug use on cognition

2.2 The use of visual methods in interview research

2.3 Life history approaches in research with people who inject drugs

2.4 Previous studies on the LSB

3. Methods

3.1 Research team

3.2 Adapting the study tool

3.3 Interview schedule, design and training

3.4 Post-interview evaluation

3.5 Sampling and recruitment of participants

3.6 Data collection

3.7 Data analysis and interpretation

4. Findings

4.1 Socio-demographic portrait of participants

4.2 Themes arising from the data

5. Discussion

Appendix 1: Interview Prompt Questions

Appendix 2: Participant Evaluation Questions

Dedicated to the memory of John Flynn

The aim of our study was to assess how the VidaviewTM Life Story Board (LSB) could enhance qualitative research with people who inject drugs. The LSB is a visual interview tool with a play board and picture-magnets that facilitates the co-construction of a lifescape that represents the personal, relational and temporal aspects of a person's lived experiences (CHASE, 2013). The LSB was developed by CHASE in the 1990s to break down barriers to communication in therapeutic interviews and facilitate dialogue about difficult life situations (CHASE, 2000, 2008; CHASE, MEDINA & MIGNONE, 2012; CHASE, MIGNONE & DIFFEY, 2010), and has been used as a data elicitation tool in a number of research projects (MIGNONE, CHASE & STIEBER ROGER, 2019). Our study was the first to explore the use of the LSB in research interviews with people who inject drugs. [1]

As with individuals dealing with trauma, people who inject drugs may experience cognitive impacts including challenges remembering specific events (CHONGO, CHASE, LAVOIE, HARDER & MIGNONE, 2018; NEEDLE et al., 1995). In such circumstances, the LSB can potentially facilitate recall. In the present article, we focus on the experiences of people who inject drugs in research interviews where the LSB was used to support their narratives of drug use and harm reduction, with particular attention to the following question: is the LSB effective in helping participants recall life events? First, we provide an overview of studies on the impact of drug use, the use of visual methods in interviews, life-history approaches to research, and previous studies on the LSB (Section 2). Second, we present the methods used in our study (Section 3). Third, we present the findings, which show three over-arching themes: 1. self-representing and co-constructing, 2. responding to the visual aspect, and 3. gaining perspective and making sense (Section 4). Finally, we discuss how these findings add to our understanding of the impact of using the LSB, and the significance of these findings for qualitative interview research (Section 5). [2]

2.1 Studies on the impact of drug use on cognition

Research over the past 20 years has identified the potential for negative impacts on cognition as a result of sustained substance use. As techniques allowing us to study the science of neuroplasticity and substance use continue to evolve (NYBERG, 2014), there is growing evidence of the neurocognitive effects of chronic opioid use (GRUBER, SILVERI & YURGELUN-TODD, 2007), psychostimulants such as cocaine and methamphetamine (NYBERG, 2014; RESKE, EIDT, DELIS & PAULUS, 2010; TOLEDO-FERNÁNDEZ et al., 2018), and polydrug use (BLOCK, ERWIN & GHONEIM, 2002), which have been shown to cause deficits in cognitive domains such as complex attention, executive function, working memory, future recall, word imagery and long-term (or autobiographical) memory (ERSCHE, CLARK, LONDON, ROBBINS & SAHAKIAN, 2006; GANDOLPHE, NANDRINO, HANCART & VOSGIEN, 2013; GHONEIM, 2004; ROBBINS, ERSCHE & EVERITT, 2008). Despite existing evidence from the fields of basic and clinical science, these findings are rarely discussed in terms of how these cognitive effects may be impacting data collection with people who use injection drugs. [3]

2.2 The use of visual methods in interview research

The use of visual methods in social science research has become more common in recent years, and encompasses tools such as photography, video, drawing, diagrams, maps, timelines, body mapping, and more (CRAWFORD, 2010; GASTALDO, RIVAS-QUARNETI & MAGALHÃES, 2018; GROENEWALD & BHANA, 2015; JENKINGS, WOODWARD & WINTER, 2008; KOLAR, AHMAD, CHAN & ERICKSON, 2015; PAIN, 2012; PROSSER & LOXLEY, 2008; TARR & THOMAS, 2011; UMOQUIT, TSO, VARGA-ATKINS, O'BRIEN & WHEELDON, 2013; WOODGATE, ZURBA & TENNENT, 2017). Although terminology and approaches are far from standardized (UMOQUIT et al., 2013), researchers have proposed that these approaches can be categorized in terms of their aim (such as enabling communication, representing data, facilitating researcher-participant relationships, etc. (GLEGG, 2019)) and whether they are participant-led or researcher-led, in terms of who creates the visuals and/or sets the parameters for their creation (UMOQUIT et al., 2013). Further distinctions have been made that rest on the media used (e.g., photography and video vs. pen and paper) (ibid.). The incorporation of visual methods into social science research comes from a number of sources, including the use of photography in anthropology and (to a lesser extent) sociology (PARKIN & COOMBER, 2009; PROSSER & LOXLEY, 2008) and, as is particularly the case with diagramming techniques, psychological therapy and social work (BRAVINGTON & KING, 2019). [4]

Studies on the use of such methods for qualitative research have shown how they can facilitate interaction and, in particular, enrich the elicitation of data from research participants, particularly in interviews. For this reason, visual methods have been used by some researchers in interviews about drug use with people from marginalized populations (MARCU, 2016) and particularly with people who inject drugs. For example, in interviews with 30 current injectors, DENNIS (2017a, 2017b) used body mapping, a "creative drawing method" (2017a, p.340) in which participants are asked "to draw their bodies in relation to how they felt before, during and after injecting drugs" (2017a, p. 340), and found that this approach allowed for narrative forms alternative to the linear narratives that typically emerge from interviews. RHODES and FITZGERALD (2006) explored various ways in which visual methods can contribute to qualitative research on addictions, as did PARKIN and COOMBER (2006) for public injecting. However, as DENNIS (2019) later pointed out, "little has changed" (p.128) in terms of how often visual methods are used in drug research, and in terms of discussions about why they may be beneficial when engaging in research with people who use drugs. [5]

2.3 Life history approaches in research with people who inject drugs

Another important, yet infrequently used approach to research with people who inject drugs is the use of the life history method, which allows for the exploration of an individual's experiences in a timeframe (HARRIS & RHODES, 2018). HARRIS and RHODES used this in the Staying Safe study to explore the life from birth of "people who have been injecting for the long term and remain hepatitis C free" (p.1125). They noted that this contrasts with other studies that only "focus on the life since drug use commencement" (p.1123). In their study, these authors incorporated visual methods through the use of a hand-drawn timeline, co-constructed with participants. However, the timeline was used for data elicitation, rather than as a study output. RANCE, GRAY and HOPWOOD (2017) conducted a secondary analysis of the same data to focus on a single interview and life history, in order to explore identity formation in the interview, and noted that an exchange regarding the interviewee's timeline "highlights the essentially collaborative, co-constructed nature of the research interview: its 'joint accomplishment'" (p.119). [6]

2.4 Previous studies on the LSB

The usefulness of the LSB has been the focus of eight scientific studies to date, all published within the last five years (MIGNONE et al., 2019). These studies focused on qualitative research data collection with marginalized communities including Indigenous men living with HIV (CHONGO et al., 2018), children (KOSHYK & WILSON, 2018; STEWART-TUFESCU, HUYNH, CHASE & MIGNONE, 2018), immigrants and newcomers (CHASE & LUDWICK, 2016; MIGLIARDI, 2017; TICAR, 2018), people who inject drugs (BOUCHER et al., 2017), and young people living with homelessness and mental health-related issues (NAPASTIUK, 2015). A recent methodological review conducted by MIGNONE et al. (2019) noted that these studies focused on the feasibility of incorporating the LSB into data collection, how it functioned as a tool for information elicitation, what factors served as facilitators or barriers to its use, and how it performed in relation to more traditional interview approaches. Findings from this review suggest that the LSB can be successfully employed with a range of study participants, it is a useful tool for data collection and it supports engagement between interviewer and study participants. Although these studies help us to understand the way the LSB has been used, there is little information about how participants interact with this data collection tool and in what ways it supports the recall of historical information and narrative details. [7]

The Participatory Research in Ottawa: Understanding Drugs (PROUD) Community Advisory Committee (CAC) was created in May 2012 to design and carry out a cohort study aiming to better understand the prevalence and context of drug use and HIV incidence among people who use drugs in Ottawa (LAZARUS et al., 2014). The PROUD sub-study of social context and life experiences that surround harm reduction practices among people who inject drugs has been described previously (BOUCHER et al., 2017); we complement this work in the present study by exploring how the LSB data collection tool was incorporated into the qualitative interviews for that sub-study. [8]

The research team for this project included both community and academic researchers. Five members from the PROUD CAC were hired as community researchers for the study based on skills related to data collection, interests and lived experiences. Community researchers were involved in each step of the study including design, data collection and data validation. Our team also included a full-time community research coordinator who provided linkage between and support for community researchers and academic researchers. She was chosen for this role because she is well known and respected in the community, and in particular had demonstrated her skills in connecting with a wide range of people who inject drugs. The community research coordinator helped to facilitate practice LSB interviews, was involved in recruiting participants, and provided cultural interpretation in relation to data collection and analysis. The community research coordinator and the community researchers in the present study are current or former drug users. All community researchers were remunerated for their involvement. [9]

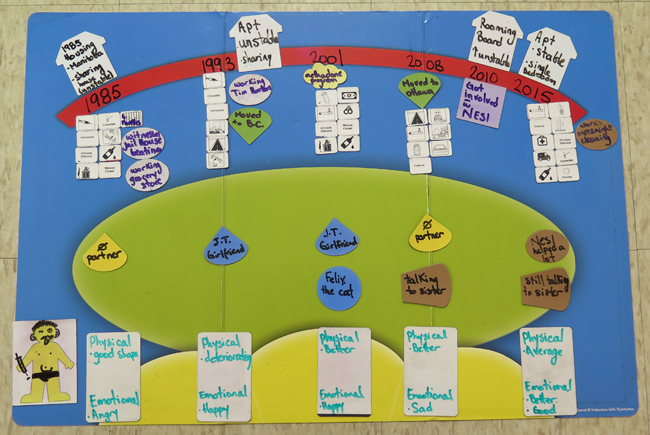

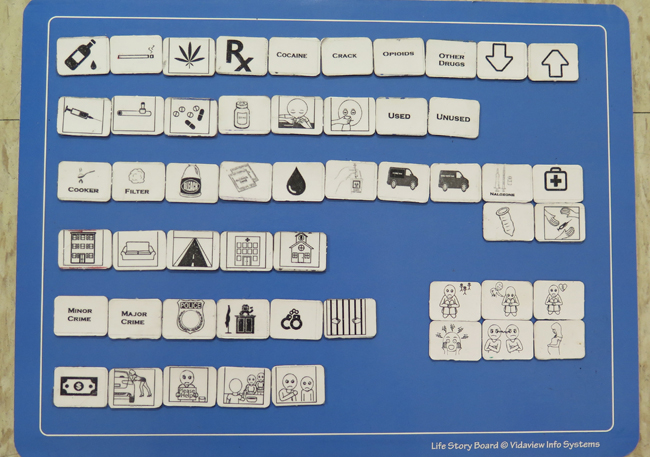

The LSB tool allows the storyboarder to visually represent a participant's lifescape. As mentioned, the tool is composed of several different types of picture magnets and a board with designated areas to represent the temporal, personal and relational aspects of participants' lives (Figure 1). For this study, the tool's creator, Dr. Rob CHASE, offered three days of training to the research team. The community researchers, including the community research coordinator, customized additional picture magnets for themes they felt would better represent the lived experiences of study participants than those provided with the LSB, for example, those representing different types of drug use. These symbols and icons were added to the original set that is provided with the LSB. This kind of customization is encouraged in the LSB Toolkit Handbook (CHASE, 2013). Figure 2 shows the magnets chosen for use in this study, including both magnet labels provided in the LSB kit and additional labels developed by the community researchers. As can be seen, these include both visual and verbal elements. Further training was provided to the community researchers regarding research ethics and qualitative interviewing methodology. They were trained in both the role of interviewer, who was primarily responsible for asking interview questions, and storyboarder, who created the visual representation to illustrate the story with the guidance of each participant. The board was primarily used to gather and organize participants' information and to facilitate the process of the research interview. Although digital photographs were taken of the board at several intervals during each interview, the visual information from the LSB is not analyzed here.

Figure 1: The Vidaview Life Story Board™ populated with simulated data

Figure 2: Customized picture-magnets for the Vidaview Life Story Board™ [10]

3.3 Interview schedule, design and training

The research team designed the semi-structured interview schedule to collect data on the following topics: personal histories of harm reduction practices, facilitators and barriers to harm reduction, and suggestions for improving harm reduction services and supports (see Appendix 1). In addition to prior practice sessions with the community research coordinator, each community researcher conducted a minimum of six practice interviews with CAC and other community members to ensure all team members were comfortable and that the interviews would be conducted using a consistent approach. [11]

The research team also designed a brief semi-structured interview schedule for an evaluation to be conducted with each participant by the community research coordinator at the end of their LSB interview in order to elicit information about their experience as a research participant. Topic areas included facilitators and barriers to using the LSB tool, and benefits and challenges to being interviewed by community researchers (see Appendix 2). This component also served to conclude each study experience on a positive note by helping the participant gain some perspective on their own story, and see particular life events as part of a bigger picture. [12]

3.5 Sampling and recruitment of participants

The goal of our recruitment strategy was to reach people who had used drugs and who could talk about their harm reduction practices over time. To do so, the community research coordinator worked with an additional person with lived experience hired for this purpose from the PROUD CAC. Both had previously conducted recruitment for research focused on drug use and were very familiar with the neighborhoods where people who use drugs tend to access services, or to purchase or use drugs. We used purposeful sampling with maximum variation (PALINKAS et al., 2015) and recruiters were asked to attend to gender and other aspects of diversity. [13]

To be included in the study, potential participants had to be at least 18 years of age, be currently living in Ottawa, and self-identify as having injected drugs within the past 12 months. On interview days, both recruiters approached individuals near community service locations, introduced themselves, and explained that they were looking for people to participate in a research study for people who inject drugs. They then asked whether the person might know someone who would be interested in participating. In this way, they did not directly ask anyone if they themselves used drugs. If the person said they were interested or requested more information, the recruiters then offered more details explaining that the project was focused on personal histories with harm reduction practices, and clarified whether the person would be willing to be interviewed about this topic. If the approached individual expressed interest in participating, recruiters explained that the research project included two back-to-back interviews: one interview of 60 to 90 minutes that would be conducted by two community researchers, and a second follow-up interview of 20 to 30 minutes with the community research coordinator to discuss their experience with the study. Those willing to participate were given an appointment card with the time and location of the interview. If they were not available on the same day, they were informed of upcoming interview days and times at the local interview site. [14]

In recognition of their time and contribution to the research, we provided participants with an honorarium of $30 CAD. We offered this in two forms, cash and grocery store gift card, but no participants chose the gift card option. We provided 4 bus tickets (value of $6.20 CAD) to reimburse each participant for their travel to and from the interview location. Finally, we also provided snacks during the interview. Research Ethics Board approval for all aspects of the study (including the main interview with the LSB and the post-interview evaluation) was obtained from the Bruyère Research Institute and the Ottawa Health Sciences Network. [15]

All interviews took place in private rooms in one of three community health centers in downtown Ottawa during July and August 2015. The community researchers chose these settings because they knew they provided extensive services for people who use drugs, and therefore were likely to be familiar to study participants and thus increase their comfort (although such familiarity was not a criterion for inclusion in the study). The interviews lasted between 29 and 130 minutes, with an average length of 83 minutes. The evaluations lasted between four and 23 minutes, with an average length of 11 minutes. Given the potential for participants to experience heightened emotions based on interview content, and to ensure both participants and community researchers had access to additional support, we arranged for a social service provider to be on site during each of the interviews (but not present in the interview room). However, only one of the study participants expressed a need for such support. [16]

As described above, two community researchers led each interview: one interviewer was primarily responsible for asking participants questions, and one storyboarder created the visual on the LSB to illustrate each participant's narrative. Written informed consent was obtained by the community researchers at the beginning of each interview. The names of the participants for this study have been replaced by pseudonyms to preserve anonymity. If not already known to the participant, community researchers self-identified as current or former drug users so that participants would be aware they were peers. [17]

After introducing the LSB to the participant, the interviewer or storyboarder asked the participant to represent themselves visually on a designated medium-sized magnet. This was so that the participant could interact and familiarize themselves with the board early on in the interview. This was the only time participants were asked to draw or write anything on the board, as this function was generally carried out by the storyboarder during the rest of the interview. In this respect, our methodology differs from past studies focusing on the LSB, in which participants were asked to populate the board themselves (MIGNONE et al., 2019). The board was populated using symbols and icons that represent different aspects of life, including family, friends, and other forms of support, important life events, and everyday activities to create a visual lifescape. [18]

3.7 Data analysis and interpretation

The content of each audio-recorded participant interview and participant evaluation was transcribed and identifying information was removed. After transcription, the community research coordinator reviewed each transcript for inaudible words, and provided contextual details and cultural interpretation of information not familiar to the transcribers or the academic research team. Transcripts were coded using a conventional content analysis approach (HSIEH & SHANNON, 2005), which is useful for developing models or building concepts (LINDKVIST, 1981). One member of the academic research team read through three transcripts to identify themes related to participant experiences with the LSB. These initial themes concerned participants' responses to the LSB, how the LSB functioned in the interview process and how it functioned to facilitate participants' recall of and reflection on life events. Subsequently, three members of the academic research team met to review the preliminary themes and to decide on a coding framework for the rest of the transcripts. Themes were initially expanded to include additional types of participant interaction with the LSB, such as participants' referring to it to fill in gaps or situate themselves in their story, and interviewers'/storyboarders' reference to the participant's co-constructed life story. One member of the academic team coded the remaining transcripts and returned to the team with information from the transcripts grouped according to these themes. The team then engaged in a dialogue to structure the sub-themes and themes. We grouped our initial themes under three broad categories pertaining to the way the LSB facilitated participants' self-representation, types of responses to the LSB and how it offered perspective on participants' life histories. Each initial theme thus became a subtheme under one of these categories. [19]

Twenty-four interviews and evaluations were conducted; of these, two were unusable due to technical errors. As a result, 22 interviews and evaluations were analyzed and form the basis of our results. We analyzed the text of the interviews to better understand how interviewers, storyboarders and participants interacted with the board, whereas we drew on the evaluations for participants' own reflections on their experiences with the LSB. [20]

4.1 Socio-demographic portrait of participants

Interviews and evaluations from 22 participants are included in this study. Participants' ages ranged from 30 to 66 years. Participants reported initiating injection drug use at age 13 to 49 years, and the number of years participants had been injecting drugs ranged from four to 45 years. No participants reported prior experience with a visual interview tool as a research participant. Participants recounted a diversity of life experiences: some mentioned having been incarcerated, others shared their experiences of living with HIV or hepatitis, while others reported histories of sex work or having experienced homelessness. Many of the participants also recounted histories of abuse and violence. [21]

4.2 Themes arising from the data

Three overarching themes emerged during data analysis: 1. self-representing and co-constructing, 2.responding to the visual aspect; and 3. gaining perspective and making sense. Each theme is described in detail below. [22]

4.2.1 Self-representing and co-constructing

The participants, interviewers and storyboarders interacted with the board in several different ways. Participants represented themselves visually on the board at the beginning of each interview at the request of the interviewers. The board was also used as a way for participants and the interviewers to situate themselves in their story or the interview schedule. In some cases, gaps in the board were noticed by the interviewer or storyboarder, which prompted them to revisit or address missing sections of the interview schedule. Finally, the board was used by the interviewers as a way to separate sections of the interview. We elaborate on each of these elements below. [23]

4.2.1.1 Participants represented themselves on the board

As mentioned, the interviewer or storyboarder asked the participant to represent themselves visually on the board at the beginning of the interview. At this juncture, the interviewer or storyboarder often resorted to humor to make the participant feel more at ease. For example:

"Interviewer: Now we got this little guy here. I just, what we use him for is just to kind of, just do whatever you want to put on it. Just (whispers) don't put a huge penis on it.

David1): (laughs) That's exactly what I want.

Interviewer: Just to make it look like you. You know, hair, I don't know, glasses. Whatever. You don't even have to, but if you'd like to. It just goes on our board.

David: I thought, I thought it'd be you showing where [inaudible]

Interviewer: Oh, that's a good idea! There you go!

(talking all at once)

Interviewer: Whatever you like, curly hair, brown hair, no hair, boobs. I don't know. Whatever identifies. (pause) Okay, that's enough (laughs). (pause) Okay. (all laugh) Not bad at all.

Okay, I just want to make sure that this is uh, on our thing, okay?

David: Oh, okay. I can't believe I got to do this.

Interviewer: You're going bald, eh? No, I'm joking (laughs).

David: I might be, I don't know! (laughs)

Storyboarder: Your roots are showing! (laughs)

Interviewer: We're bad, eh? We're bad.

David: Rootsy. Just call me rootsy.

Interviewer: God I wish we had some real snacks.

David: I put some underwear on it.

Interviewer: Oh, nice.

David: Cause I'm kinda shy.

Interviewer: What the devil is that? Never mind.

David: That's my little belly.

Interviewer: Oh, it's your wee belly. Isn't that cute!

David: (laughs)

Interviewer: You're in the speedo days, eh? (laughs)

David: (laughs)

Interviewer: You got the little speedo shorts on it (laughs).

David: Um. That's what I want. (pause) Alright. There we go. I guess that's good" (Extract #1, interview, lines 56-80). [24]

4.2.1.2 The board functioned as a place marker in the interview schedule

The majority of the interviews involved a short break, after which the board was useful in helping the interviewer to seamlessly resume the interview. The board also often acted as a place marker in the interview schedule in cases where the discussion expanded on the original interview topics. For example, participants and interviewers frequently exchanged information regarding the newest treatments for Hepatitis C or the perceived quality of housing-related services. In these instances, the storyboarder or the interviewer used the board to redirect the interview when they felt it was an appropriate time to do so. For example:

"Mark: ... Everyday a person gets it hey. I think it's Hep A, no it's B.

Interviewer: Oh, they have a shot, a three-shot ...

Mark: Oh, do they?

Interviewer: Yeah. It's called Twinrex or something like that, it's for Hep A, B & C, oh Hep A & B.

Mark: Oh well maybe I'll check that out for sure.

Interviewer: Yeah, they offer it here actually.

Mark: Oh okay.

Storyboarder: So were you drinking in '95?" (Extract #2, interview, lines 364-371). [25]

The board was also used as a place marker by the participants:

"Interviewer: Yeah. You know I talk about it. And uh, put it right on her, and she ended up going down for the whole thing. They weren't hit. They worked for somebody else. But the [inaudible] told them, if you don't tell us where ... I couldn't believe, I thought. And you're supposed to be this great, great guy. Going around [inaudible]. Okay, so let's try and get done some more. Okay, where are we?

David: 1991.

Storyboarder: So, were you injecting drugs or using any drugs, and what were they?

David: I was injecting heroin, and uh ..." (Extract #3, interview, lines 330-333). [26]

4.2.1.3 Gaps on the board prompted interviewers to ask additional questions

The visual aspect of the board also seemed to promote more natural conversation between the participant and the interviewers. While in conversation, the interviewers were able to easily identify which sections of the interview they still needed to cover based on the remaining gaps on the board as it was in development. For example:

Interviewer: "Okay, so now what we're going to do, Vanessa, is we're going to fill in from this point to this point. Has there been any point in these two times where your drug use and your harm reduction have changed?" (Extract #4, interview, line 123) [27]

4.2.1.4 The populated board was used to demarcate phases of the interview

The board was used by the interviewer and storyboarder to document the more concrete aspects of the interview, such as the participant's perceived progression of their mental and physical health, and their history of drug injection and harm reduction. However, the interviewers seemed to make a clear distinction as to when the board should and should not be used. The interviewers treated the questions designed to be posed towards the end of the interview as not involving the board (i.e., questions 9-13 in Appendix 1). These questions were perhaps more abstract in nature or at least were conceived as more difficult to render visually. One example of this clear separation is given in the interview with Steven, when the interviewer says "Okay so that pretty much finishes that. Now I've just got a few questions to ask" (Extract #5, interview, line 423). [28]

4.2.2 Responding to the visual aspect

Participants expressed a range of responses to the board, varying from more expressive and cerebral perceptions to comments about its material aspects. The participants also referred to the board as a way to corroborate or emphasize their life story to the interviewers or the evaluator. [29]

4.2.2.1 Participants expressed both emotional and cognitive responses to the board

Participants generally responded positively to the use of the board during the interview. David expressed this sentiment, "I just like the visual thing a lot. It's the first time I've done this. And I like it a lot. Like I wish I could take a picture of it" (David, Extract #6, evaluation, line 991). Similarly, Steven seemed to enjoy being able to see how his emotional state evolved over time:

"Evaluator: Oh cool, awesome. Can I ask you what you enjoyed about it so much, or one or two of the things that you enjoyed about it?

Steven: What I really enjoyed about it is how I was lost back here...

Evaluator: Yeah ...

Steven: ... And how I'm happy at the end" (Extract #7, evaluation, lines 526-529). [30]

For Michael, the use of the board during the interview seemed to have almost a therapeutic outcome:

"Storyboarder: So this is your life story as you told us.

Michael: Yeah, okay.

Storyboarder: That's how it looks from start to finish.

Michael: That is so cool man. That is right on.

(...)

Michael: Okay. Yeah man thanks for taking the time to do that, that's kind of...

Storyboarder: It's pretty cool eh?

Michael: You know what I feel like I lifted ... it feels like I've gotten 300 pounds off of my shoulders" (Extract #8, interview, lines 797-800, 802-804). [31]

For Angela, the use of the board offered a more informal and more playful way of collecting research data:

"Angela: It doesn't feel so clinical.

Evaluator: That's totally what I thought. It doesn't have that sterile...

Angela: Yeah, it's more like ... I feel more like a kid in kindergarten or something like that.

Evaluator: Good!

Angela: Or like childlike!

Evaluator: Yes because it's playing, you get to play.

Angela: Yeah and it's like the pieces of a puzzle that you know" (Extract #9, evaluation, lines 718-724). [32]

Some participants noted that the board had made it easier for them to share difficult life events. For example, Sebastian mentioned that the board had helped him to unpack certain past experiences: "It got me to open up about some things" (Extract #10, evaluation, line 518). Similarly, when asked whether the board could trigger negative thoughts, Angela responded that it did bring back difficult memories, but also allowed her to be somewhat objective:

"Evaluator: Can it pull up negative thoughts?

Angela: It can but it can also like ... I mean I had a little cry when I brought up my brother and when he passed and that but you know we went and had a smoke and I was able to calm myself down and come back to the board and look at 'Okay that was this, now you know let's move on to the next.' It's kind of neat getting from this end to this end" (Extract #11, evaluation, lines 647-648). [33]

However, some participants reacted negatively to the way the board's visual representation reminded them of difficult experiences. For example:

"Evaluator: How would you rate your overall experience with the Life Story Board?

Jennifer: Three. It's pretty bad.

Evaluator: Yeah and can you tell me why?

Jennifer: Well because there's so much shit.

Evaluator: Is it ...

Jennifer: It's a shit storm is what it is.

Evaluator: Is too much for ... Does it leave too much open ... it's not organised?

Jennifer: Yeah, it's organised, but it's just leaving a lot of things open right, open wounds" (Extract #12, evaluation, lines 659-666). [34]

For Vanessa, visualizing her life story on the populated board raised difficult emotions:

"Evaluator: What kind of emotions?

Vanessa: Sadness.

Evaluator: Yeah?

Vanessa: Yeah.

Evaluator: Can I ask why?

Vanessa: Because I am not talking with my kids right now" (Extract #13, evaluation, lines 233-238). [35]

Participants also had cognitive responses to the board. When asked by the evaluator if there was anything that she liked about the interviewing process, Patricia responded "I guess I found the whole process interesting. To have things put on the timeline, and those key factors that are displayed. It's interesting to look at" (Extract #14, evaluation, line 562). For Matthew, the process of populating the board was reassuring and transparent:

"Matthew: So when people ask me questions and they are writing down their own personal notes, I get all paranoid because I had ...

Evaluator: Because it's you.

Matthew: ... Yeah and I had no guarantee that they're writing what I'm saying.

Evaluator: Oh that's good!

Matthew: So this way it made me feel a little bit more comfortable that they're actually writing what I say.

Evaluator: Because you're a part of it.

Matthew: Yeah.

Evaluator: Yeah! I mean if they're facing you ...

Matthew: I know I'm not telling them one thing and they're writing down the complete opposite because it's right here in front of me" (Extract #15, evaluation, lines 580-588). [36]

Finally, most participants enjoyed the overall process of using the board during the interview. As Sebastian put it, "[i]t's a good way of doing it. It makes sense. It puts it right before your eyes ... It makes it more real" (Extract # 16, evaluation, line 463). [37]

4.2.2.2 Participants and interviewers responded to the physical aspects of the board

The interviewers (including the evaluator) and the participants often referred to the physical aspects of the board. At times they expressed that they felt the board was perhaps too small to capture their entire life story. For example, when the interviewer asked Jennifer if she had been involved in any minor or major crime, she replied: "Is there enough room on the board?" (Extract #17, interview, line 295) The storyboarder also remarked that the space on the board was too limited to include all of Mark's relevant lived experience:

"Interviewer: Okay so 1997 or is it 1998?

Mark: '98.

Interviewer: '98.

Mark: I got out.

Interviewer: You got out of jail. Okay you forgot to put 97 for jail.

Mark: Yeah '97 ...

Storyboarder: Well we'll just go to '98 because I'll mark jail in here.

Interviewer: Okay.

Storyboarder: Because we're running out of space.

Interviewer: Yeah we are.

Mark: Oh yeah we still got until 2015 hey" (Extract #18, interview, lines 423-433). [38]

However, participants generally reacted positively to the magnets and other physical aspects of the board. For example, Donald asked the evaluator if he could take a few of the magnets, perhaps because he wanted souvenirs from his involvement in the research project:

"Donald: Hey, can I take a couple of these?

Evaluator: Yeah.

Donald: You think I could?

Evaluator: Yeah, absolutely.

Donald: I don't want to steal them, so I'd rather ask. Just let me take two, please?

Evaluator: Yeah, no, totally.

Donald: Yeah?

Evaluator: Yeah, absolutely.

Donald: Okay, thank you" (Extract #19, evaluation, lines 565-573). [39]

4.2.2.3 Participants referenced the populated board once it was complete

Participants and interviewers consistently referred to what had been drawn or written on the board as a way to validate, reinforce or confirm what had been shared by the participant. Once complete, the board was also used as a way to transition from the interview to the evaluation. For example, when the evaluator entered the interviewing room, David used the populated board as a way to introduce himself to the evaluator before they began the formal evaluation:

"David: I guess this is supposed to be me.

Evaluator: Did you draw this? (laughs)

David: Yeah!

Evaluator: Oh! In your undies!

David: Yeah, yeah. I had to put underwear on cause I'm a little shy.

Evaluator: Of course! (laughs)

David: And that's my little belly.

Evaluator: Is this you at home in the morning?

David: Yeah" (Extract #20, evaluation, lines 1031-1039). [40]

The board also seemed to support meaningful conversations about coping with difficult life experiences. For example:

"Evaluator: And if you really ... this is the thing, like we can look at this and we would be like 'Holy fuck look how bad we fucked up.'

Angela: Yes.

Evaluator: 'Look at this' and we've gotten in and out, in and out ... but if you think about it, you're still ...

Angela: Right here!

Evaluator: ... And you're still right here and you're only right here on this. This is just the end ... this little tiny story but you ...

Angela: Yeah but this is where I'm at now! See my marijuana and my medication and I'm a flag girl in construction! And I need more peer support, but I'm doing better.

Evaluator: But you know that you're working towards something.

Angela: Yeah, exactly" (Extract #21, interview, lines 649-656). [41]

4.2.3 Gaining perspective and making sense

All participants were able to co-construct a visual lifescape of their drug use and harm reduction practices with facilitation by the community researchers, and were unanimous in saying that they would repeat the experience of being interviewed with the same visual board or a similar one. They articulated that the board enabled them to reflect on their lives, often mentioning that they gained insight about their drug use, how their addictions had evolved over time, and the hardships they had overcome, for example:

"Steven: Well I think when I look at the board now and compare that to how I was in 2009 when I was taking care of my mom just before she passed away and at the same time I couldn't see my kids ... from losing my mom and not being able to see my kids, I just basically wanted to kill myself with drugs.

Evaluator: Yeah.

Steven: And I think now I realize that my mom would be proud of myself that I have my addiction in check" (Extract #22, interview, lines 609-611). [42]

Similarly, Mark mentioned, "[i]t was good. It's a whole insight about the addiction and its problems" (Extract #23, evaluation, line 651) while for Matthew the interview experience with the board reminded him of important personal relationships: "I never sat down and thought about how many people I actually know and how many people I'm actually close to" (Extract #24, evaluation, line 568). [43]

Others felt that the board had helped them to realize that they would benefit from certain changes in their lives. Caroline articulated this well: "Just the fact that it puts my life right now into perspective. Like I got to do some shit. Like I got to wake up" (Extract #25, evaluation, line 385). For Patricia, the board was useful in organizing her past life experiences:

"I think it was a good tool. Because normally I think of an event, or maybe couple of consecutive events, or within one year, but looking at your life on a larger timeline isn't what the normal thinking process is" (Extract #26, evaluation, line 570). [44]

Angela echoed this perception eloquently, while adding that the board made it easier to broach certain topics:

"Angela: Yeah, it's very good. I found it very good. I found it really cathartic actually.

Evaluator: Really!

Angela: I talked about stuff that I thought I wasn't able to talk about without completely cracking up but looking at the board sort of made it easier for me.

Evaluator: Did it give you a focus?

Angela: Focus yeah, a focus. I actually was able to make sense of some things.

Evaluator: Did you find it helped you?

Angela: I could see you know like how it got sort of progressively worse and then it sort of gets progressively better. But that's because it's kind of like me ... it's gotten very bad, then it got better, and then it got really bad again.

(...)

Evaluator: Did you learn anything new about yourself?

Angela: I did actually! I learned that you know anything is really possible and that, you know, I'm just a work in progress. Like you know, I'm not here anymore, I'm over here" (Extract #27, evaluation, lines 598-604, 689-690). [45]

The board also helped participants remember certain life events. For Angela, it was the action of physically putting information down on the board that prompted her memories:

"Evaluator: And a lot of times it's hard to remember certain events.

Angela: Yeah.

Evaluator: When you're sitting and just talking to someone ...

Angela: Yeah but then when you put it down on like this, things come back to you because you go 'Oh fuck yeah I remember at that time ... ' especially when you are doing it in small increments like that" (Extract #28, evaluation, lines 735-738). [46]

When asked what he preferred about the whole interview process, Jason mentioned that it was the fact that the board helped him remember life events that really stood out:

"Evaluator: What was your favorite part ... what did you like about it the most?

Jason: I just remembered ... I forgot some things you know what I mean.

Evaluator: Oh good!

Jason: You forget hey.

Evaluator: So was it having the visual, did that ...

Jason: I looked at it, I got to touch, you know what I mean, and I have to see, and I would go 'oh yeah I remember that now. I remember in Calgary and the fuckin crack whores and 'cause I ran a stroll there hey,' you forget about all that stuff" (Extract #29, evaluation, lines 435-440). [47]

Our study extended prior research on the LSB by investigating its usefulness in facilitating research with people who inject drugs, specifically their recall of personal histories of drug use and harm reduction practices. The findings suggest that the LSB was a helpful tool in this regard, as it helped participants to focus on their life stories and to identify specific occasions or incidents. Through this study, we have new insights into the ways that the board facilitated participation and the sharing of personal information as demonstrated in the interviews themselves, rather than relying solely on self-report. Several benefits were observed. [48]

One advantage of using the board during the research process was that it facilitated the organization of participant information in a logical and chronological order because of the temporal markers on the board (i.e., the timeline). Some researchers have argued that timelines may not represent how people actually think about their lives because they are too linear, and also that they may have a linearizing effect on the interview process (BAGNOLI, 2009; BRAVINGTON & KING, 2019). However, as BRAVINGTON and KING pointed out, "[t]he act of construction also introduces an element of dynamism into the linear structure of an interview" (2019, pp.508-509), an effect that was clearly the case with the LSB in our interviews. Further, the LSB itself acted as a place marker in the interviews, enabling interviewers and participants to engage in a less formal and more natural conversation, as the interviewers could easily return to the interview schedule when they believed it appropriate to do so. These results were consistent with participants' feedback regarding the use of the LSB in the study by CHASE et al. (2012). However, in that study some interviewers felt the LSB periodically drew attention away from the participant, an outcome that was rarely observed in the current study. This difference may be attributable to the fact that in our study one person (the storyboarder) was dedicated to populating the board, thus leaving the interviewer freer to focus on the interview itself. [49]

This tool provided a more transparent means of recording information than either notes or recordings. Some participants found the process of populating the LSB in front of them to be transparent and reassuring, and in the evaluations, participants consistently referred to the populated board to confirm, reinforce or validate what they had shared with the interviewers. This transparent and participatory co-construction may be an additional factor in participants' positive response to the populated board, in contrast to the strongly negative reaction on the part of some participants in HARRIS and RHODES' (2018) study when they were presented with computer-generated versions of their completed life-grids, which the researchers had created between participants' first and second interviews. [50]

Another strength of the LSB was that it seemed to support the community researchers, who were newer to qualitative interviewing. That is, the board was useful in capturing the life experiences of participants and thus facilitated the interview process. A methodological difference in the present study was that participants were not asked to populate the board themselves (except at the very beginning of the interview, when they were asked to draw themselves on a magnet that was then placed on the board). In this way, our use of the LSB combined features of both participant- and researcher-led diagrammatic elicitation (GLEGG, 2019; UMOQUIT et al., 2013). [51]

Seeing their life stories visually depicted on the board seems to have enabled participants to gain perspective on and make greater sense of their lives, which echoes findings by CHONGO et al. (2018), MEDINA-MUÑOZ et al. (2016) and NAPASTIUK (2015). Indeed, participants in our study noted that the board facilitated the process of sharing difficult life events and unpacking past hardships, which may be related to the LSB's origin as a tool to support counseling sessions. Here, the board also played a role in prompting the participant's memory, which likely allowed for a more complete picture of their drug use and harm reduction practices to emerge. The facilitation of recall is consistent with findings from the interviews with children in the study by STEWART-TUFESCU et al. (2019). [52]

In terms of GLEGG's (2019) typology of visual methods, our findings show that the LSB performs well for at least three of her five purpose-based categories, namely, to 1. enable communication (e.g., by supporting topic transitions), 2. facilitate the relationship (e.g., by positioning the participant as a collaborator and co-constructor), and 3. enhance data quality and validity (e.g., by facilitating probing and improving recall). Given our study design, the role of the LSB in enhancing data quality was perhaps its most important aspect. [53]

As a potential methodological limitation, we are aware that in many cases participants, interviewers and storyboarders were acquainted. This may have affected their interactions, and may have had a confounding effect on the impact of the LSB in drawing out the participant's life story. It may also have had an influence on the participants' evaluation of the whole process, including their comfort with providing more negative impressions. Although we tried to create space for the participants to openly share their feedback by having the community research coordinator conduct the evaluation interviews, rather than the community researchers, participants may still have felt pressure to reflect positively on the process. In addition, the community research coordinator, as another community member, was also acquainted with some, if not all, of the participants. Such dynamics should be considered in future studies involving community researchers that seek to evaluate visual tools such as the LSB. [54]

A further consideration with our particular approach to qualitative research (i.e., using a visual data elicitation tool and having community researchers conduct the interviews) is that it is a fairly labor- and resource-intensive process, both for data collection, including the peer training aspect, and for data analysis. However, we would argue that any limitations of this approach are outweighed by the access to study participants and the richness of the data it makes possible. [55]

As a research tool in our study, we observed a few other limitations with the LSB. The physical dimensions of the board meant that only a limited number of experiences could be recorded, as was mentioned by some participants and interviewers. However, the way the board is designed to have both a sequential timeline and conceptual areas means that it combines the strengths of both timeline and network approaches to diagrammatic elicitation (BRAVINGTON & KING, 2019; GLEGG, 2019). In some instances, we also observed that the need to populate specific details on the board interfered with the interview flow, resulting in a side conversation between the interviewer and the storyboarder (data not shown). [56]

However, these limitations appear to be minor, given the role the LSB can play in facilitating the process of life story interviewing, consistent with other visual methods such as timeline diagramming (HARRIS & RHODES, 2018; KOLAR et al., 2015) and the lifegrid approach (GROENEWALD & BHANA, 2015). Our study has shown that both participants and interviewers engaged with the LSB in nuanced ways that enabled them to collaborate productively in representing the participant's life story, an approach which allowed participants to gain new insight into the meaning of their own lives. This points to the potential the LSB has to help marginalized groups and communities find their own voice and strengthen their self-understanding. Building on this strength, future avenues of research could involve comparing different interview modes, such as with/without the LSB and with/without a storyboarder (i.e., with the participants themselves populating the board), to better understand the specific aspects whereby this tool enhances the life story interview process. [57]

We are grateful to all study participants and PROUD Community Advisory Committee members for their contributions to this research. In particular, we want to acknowledge Rangi METCALF, peer researcher, for conducting the participant recruitment with the community research coordinator. We also wish to acknowledge Dr. Rob CHASE, who is the creator of the Vidaview Life Story BoardTM, for his support and for providing initial training to the research team.

Funding for this research was provided by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR) Social Research Centre for HIV Prevention (HCP-97106). Claire KENDALL is supported by a CIHR-Ontario HIV Treatment Network New Investigator Award. Zack MARSHALL was supported by a CIHR Fellowship at the time of this project.

Appendix 1: Interview Prompt Questions

Let's start by you telling me a bit about yourself. How old are you? What area do you live in or near? Do you live in an apartment, house, shelter, are you homeless, etc.? How long have you lived in Ottawa?

Tell me what the term harm reduction means to you.

For the purpose of this interview, we use the term harm reduction to mean "all the ways you reduce your risk in your routines or decisions as an injection drug user." Would you say you do or have ever practiced harm reduction?

When did you start using injection drugs? Did you use any harm reduction practices when you first started using injection drugs? [If yes] What were they? [If no] Why not?

How has your injection drug use changed over time? Has your use of harm reduction changed over time? [If yes] How? [If no] Why not?

What does your injection drug use look like at this point in your life? Do you use harm reduction practices at this time? [If yes] What are they? [If no] Why not?

Has there been a person (friend, service provider, etc.) who has supported you or influenced you in regards to harm reduction? Who has taught you the most about harm reduction so far in your life? Have there been others who have helped you throughout your time using injection drugs? Who are these people to you/what did or do they mean to you?

Apart from learning about harm reduction from people you know, are there other places where you get information about harm reduction and injection drug use? [e.g. online, drug user groups, print resources, needle distribution, community health centre etc. If online, ask for specific websites]

What services do you wish had been available to you but were not? What do you think services could be doing differently now?

Are there people or circumstances that get in the way of you practicing harm reduction?

Do you find there are some harm reduction practices that are encouraged or supported more than others? [If yes] Which ones? Has anyone ever suggested that your harm reduction practices are not a good idea or the best option? [If yes] Can you tell me more about that?

Is there anything about your personal ethnicity, gender or sexual identity that you think is relevant to your harm reduction practices?

Do you wish to change the ways you practice harm reduction in your life? [If yes] What do you want to do differently? [If nothing] Why not?

Ask the following questions repeatedly at all different parts of the participant's story.

Where were you living at the time?

Do you think it was stable housing?

Did it affect your harm reduction practices? How?

How were your personal relationships at the time?

Did they affect your harm reduction practices? How?

How was your physical health at the time?

Did it affect your harm reduction practices? How?

How was your mental health at the time?

Did it affect your harm reduction practices? How?

Other than injection drugs, did you use any other drugs at the time?

Did you practice harm reduction in your use of these drugs? How?

Did you have any contact with law enforcement at the time?

Did it affect your harm reduction practices? How?

What was your employment situation like at the time?

[If unemployed] How did you make money?

[If employed] Did you make money in other ways as well?

Did it affect your harm reduction practices? How?

Follow up on any of the above questions!

Appendix 2: Participant Evaluation Questions

1. On a scale of 1 to 10, where 10 is perfect, how would you rate your overall experience with the Life Story Board?

1 _______________________________________________________ 10

1.1 What did you like about the interview?

1.2 What did you not like about the interview?

1.3 Have you ever participated in an interview for a research project before? If yes, how did this experience compare to your previous interview experience? In what ways was it similar or different?

2. On a scale of 1 to 10, where 10 is perfect, how well did the Life Story Board help to portray your harm reduction practices?

1 _______________________________________________________ 10

2.1 Can you tell me more about your reason for your choice of number?

2.2 What was it like to see your experiences mapped out on the board?

2.3 Did using the Life Story Board help you remember details you might have forgotten otherwise?

2.4 Was there anything that made using the Life Story Board confusing for you?

2.5 What did you think of the little pictures on the magnets?

2.6 Did you learn anything new about yourself during this interview?

2.7 Did you learn anything new about harm reduction during the interview?

3. This is the first time we have used the LSB board with peer researchers. In your interview, there were two peer researchers, one had the role of the interviewer who asked the main questions, and the other person we call a storyboarder.

On a scale of 1 to 10, where 10 is perfect, how would you rate your experience with the interviewer:

1 _______________________________________________________ 10

3.1 What did you like about your experience with the interviewer?

3.2 Is there anything that would have made your experience better?

On a scale of 1 to 10, where 10 is perfect, how would you rate your experience with the storyboarder:

1 _______________________________________________________ 10

4. Two last questions:

4.1 If you were asked to participate in another interview using the Life Story Board, would you say yes?

4.2 Is there anything else you would like to tell us about your experience today?

1) The names of the participants for this study have been replaced by pseudonyms to preserve anonymity. <back>

Bagnoli, Anna (2009). Beyond the standard interview: The use of graphic elicitation and arts-based methods. Qualitative Research, 9(5), 547-570.

Block, Robert I.; Erwin, Wesley J. & Ghoneim, Mohamed M. (2002). Chronic drug use and cognitive impairments. Pharmacology Biochemistry and Behavior, 73(3), 491-504.

Boucher, Lisa M.; Marshall, Zack; Martin, Alana; Flynn, John V.; Lalonde, Christine; Pineau, Dave; Bigelow, Jennnifer; Rose, Tiffany; Chase, Robert M.; Boyd, Rob; Tyndall, Mark & Kendall, Claire (2017). Expanding conceptualizations of harm reduction: Results from a qualitative community-based participatory research study with people who inject drugs. Harm Reduction Journal, 14, 1-18.

Bravington, Alison & King, Nigel (2019). Putting graphic elicitation into practice: Tools and typologies for the use of participant-led diagrams in qualitative research interviews. Qualitative Research, 19(5), 506-523.

Chase, Robert M. (2000). The butterfly garden: Batticaloa, Sri Lanka. Final report of a program development and research project (1998-2000), http://vidaview.ca/wp-content/uploads/2010/01/BFG-2000-book.pdf [Accessed: March 7, 2019].

Chase, Robert M. (2008). The Life Story Board: A pictorial approach to psychosocial interviews of children in difficult circumstances. Unpublished monograph, http://vidaview.ca/wp-content/uploads/2010/01/LSB_monograph_2008.pdf [Accessed: March 7, 2019].

Chase, Robert M. (2013). The Vidaview Life Story BoardTM toolkit handbook. Winnipeg: vidaview.ca.

Chase, Robert M. & Ludwick, Dianne (2016). Newcomer worker voices matter: Learning from the group story. Unpublished report, MFL Occupational Health Centre, Winnipeg, Manitoba, Canada.

Chase, Robert M.; Medina, Maria Fernanda & Mignone, Javier (2012). The Life Story Board: A feasibility study of a visual interview tool for school counsellors. Canadian Journal of Counselling & Psychotherapy / Revue Canadienne de Counseling et de Psychothérapie, 46(3), 183-200.

Chase, Robert M.; Mignone, Javier & Diffey, Linda (2010). Life Story Board: A tool in the prevention of domestic violence. Pimatisiwin, 8(2), 145-154.

Chongo, Meck; Chase, Robert M.; Lavoie, Josée G.; Harder, H.G. & Mignone, Javier (2018). The Life Story Board as a tool for qualitative research: Interviews with HIV-positive Indigenous males. International Journal of Qualitative Methods 17(1), 1-10, https://doi.org/10.1177/1609406917752440 [Accessed: August 20, 2018].

Crawford, Allison (2010). If "the body keeps the score": Mapping the dissociated body in trauma narrative, intervention, and theory. University of Toronto Quarterly, 79(2), 702-719.

Dennis, Fay (2017a). The injecting "event": Harm reduction beyond the human. Critical Public Health, 27(3), 337-349.

Dennis, Fay (2017b). Conceiving of addicted pleasures: A "modern" paradox. International Journal of Drug Policy, 49, 150-159.

Dennis, Fay (2019). Making problems: The inventive potential of the arts for alcohol and other drug research. Contemporary Drug Problems, 46(2), 127-138.

Ersche, Karen D.; Clark, Luke; London, Mervyn; Robbins, Trevor W. & Sahakian, Barbara J. (2006). Profile of executive and memory function associated with amphetamine and opiate dependence. Neuropsychopharmacology, 31(5), 1036-1047.

Gandolphe, Marie Charlotte; Nandrino, Jean Louis; Hancart, Sabine & Vosgien, Véronique (2013). Autobiographical memory and differentiation of schematic models in substance-dependent patients. Journal of Behavior Therapy and Experimental Psychiatry, 44(1), 114-121.

Gastaldo, Denise; Rivas-Quarneti, Natalia & Magalhães, Lilian (2018). Body-map storytelling as a health research methodology: Blurred lines creating clear pictures. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung / Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 19(2), Art. 3, http://dx.doi.org/10.17169/fqs- 19.2.2858 [Accessed: May 13, 2020].

Ghoneim, Mohamed M. (2004). Drugs and human memory (Part 2). Anesthesiology, 100(4), 1277-1297.

Glegg, Stephanie M.N. (2019). Facilitating interviews in qualitative research with visual tools: A typology. Qualitative Health Research, 29(2), 301-310.

Groenewald, Candice & Bhana, Arvin (2015). Using the lifegrid in qualitative interviews with parents and substance abusing adolescents. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung / Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 16(3), Art. 24, http://dx.doi.org/10.17169/fqs-16.3.2401 [Accessed: May 13, 2020].

Gruber, Staci A.; Silveri, Marisa M. & Yurgelun-Todd, Deborah A. (2007). Neuropsychological consequences of opiate use. Neuropsychology Review, 17(3), 299-315.

Harris, Magdalena & Rhodes, Tim (2018). "It's not much of a life": The benefits and ethics of using life history methods with people who inject drugs in qualitative harm reduction research. Qualitative Health Research, 28(7), 1123-1134.

Hsieh, Hsiu-Fang & Shannon, Sarah E. (2005). Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qualitative Health Research, 15(9), 1277-1288.

Jenkings, K. Neil; Woodward, Rachel & Winter, Trish (2008). The emergent production of analysis in photo elicitation: Pictures of military identity. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung / Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 9(3), Art. 30, http://dx.doi.org/10.17169/fqs-9.3.1169 [Accessed: May 13, 2020].

Kolar, Kat; Ahmad, Farah; Chan, Linda & Erickson, Patricia G. (2015). Timeline mapping in qualitative interviews: A study of resilience with marginalized groups. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 14(3), 13-32, https://doi.org/10.1177/160940691501400302 [Accessed: September 16, 2019].

Koshyk, Jamie & Wilson, Taylor (2018). Exploring the impact of the Abecedarian early childhood intervention on parents and caregivers in a subsidized housing complex. Unpublished report, Red River College, Winnipeg, Manitoba, Canada.

Lazarus, Lisa; Shaw, Ashley; LeBlanc, Sean; Martin, Alana; Marshall, Zack; Weersink, Kristen; Lin, Dolly; Mandryk, Kira & Tyndall, Mark W. (2014). Establishing a community-based participatory research partnership among people who use drugs in Ottawa: The PROUD cohort study. Harm Reduction Journal, 11(26), 1-8.

Lindkvist, Kent (1981). Reliability and content analysis. In Karl Erik Rosengren (Ed.), Advances in content analysis (pp.23-41). Beverly Hills, CA: Sage.

Marcu, Oana (2016). Using participatory, visual and biographical methods with Roma youth. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung / Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 17(1), Art. 5, http://dx.doi.org/10.17169/fqs-17.1.2270 [Accessed: May 13, 2020].

Medina-Muñoz, María-Fernanda; Chase, Rob; Roger, Kerstin; Loeppky, Carla & Mignone, Javier (2016). A novel visual tool to assist therapy clients’ narrative and to disclose difficult life events: The Life Story Board. Journal of Systemic Therapies, 35(1), 21-38, https://doi.org/10.1521/jsyt.2016.35.1.21 [Accessed: March 7, 2019].

Migliardi, Paula (2017). African immigrant women living with HIV: An exploration of care and support. Unpublished report, Sexuality Education Resource Centre, Winnipeg, Manitoba, Canada.

Mignone, Javier; Chase, Robert M. & Stieber Roger, Kerstin (2019). A graphic and tactile data elicitation tool for qualitative research: The Life Story Board (LSB). Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung / Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 20(2), Art. 5, http://dx.doi.org/10.17169/fqs-20.2.3136 [Accessed: May 9, 2020].

Napastiuk, Pavlina (2015). A training report to use Lifestory BoardTM to address the met and unmet needs of Vancouver's homeless/street involved youth. Master thesis, social work, University of Victoria, British Columbia, Canada, https://www.uvic.ca/hsd/socialwork/assets/docs/student-research/PNapastiuk Project.pdf [Accessed: March 7, 2019].

Needle, Richard; Fisher, Dennis G.; Weatherby, Norman; Chitwood, Dale; Brown, Barry; Cesari, Helen; Booth, Robert; Williams, Mark L.; Watters, John; Andersen, Marcia & Braunstein, Mildred (1995). Reliability of self-reported HIV risk behaviors of drug users. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors, 9(4), 242-250.

Nyberg, Fred (2014). Structural plasticity of the brain to psychostimulant use. Neuropharmacology, 87, 115-124.

Pain, Helen (2012). A literature review to evaluate the choice and use of visual methods. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 11(4), 303-319, https://doi.org/10.1177/160940691201100401 [Accessed: December 6, 2019].

Palinkas, Lawrence A.; Horwitz, Sarah M.; Green, Carla A.; Wisdom, Jennifer P.; Duan, Naihua & Hoagwood, Kimberly (2015). Purposeful sampling for qualitative data collection and analysis in mixed method implementation research. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research, 42(5), 533-544.

Parkin, Stephen & Coomber, Ross (2009). Value in the visual: On public injecting, visual methods and their potential for informing policy (and change). Methodological Innovations Online, 4(2), 21-36, https://doi.org/10.1177/205979910900400203 [Accessed: December 7, 2019].

Prosser, Jon & Loxley, Andrew (2008). Introducing visual methods. Southampton: ESRC National Centre for Research Methods, http://eprints.ncrm.ac.uk/420/ [Accessed: December 3, 2019].

Rance, Jake; Gray, Rebecca & Hopwood, Max (2017). "Why am I the way I am?" Narrative work in the context of stigmatized identities. Qualitative Health Research, 27(14), 2222-2232.

Reske, Martina; Eidt, Carolyn A.; Delis, Dean C. & Paulus, Martin P. (2010). Nondependent stimulant users of cocaine and prescription amphetamines show verbal learning and memory deficits. Biological Psychiatry, 68(8), 762-769.

Rhodes, Tim & Fitzgerald, John (2006). Visual data in addictions research: Seeing comes before words?. Addiction Research & Theory, 14(4), 349-363.

Robbins, T.W.; Ersche, K.D. & Everitt, B.J. (2008). Drug addiction and the memory systems of the brain. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 1141(1), 1-21.

Stewart-Tufescu, Ashley; Huynh, Elizabeth; Chase, Robert M. & Mignone, Javier (2019). The Life Story Board: A task-oriented research tool to explore children's perspectives of well-being. Child Indicators Research, 12(2), 1-19.

Tarr, Jen & Thomas, Helen (2011). Mapping embodiment: Methodologies for representing pain and injury. Qualitative Research, 11(2), 141-157.

Ticar, Jessica Ellen (2018). Embodied transnational lives among Filipina/o/x youth in urban educational spaces. Gender, Place & Culture, 25(4), 612-616.

Toledo-Fernández, Aldebarán; Brzezinski-Rittner, Aliza; Roncero, Carlos; Benjet, Corina; Salvador-Cruz, Judith & Marín-Navarrete, Rodrigo (2018). Assessment of neurocognitive disorder in studies of cognitive impairment due to substance use disorder: A systematic review. Journal of Substance Use, 23(5), 535-550.

Umoquit, Muriah; Tso, Peggy; Varga-Atkins, Tünde; O'Brien, Mark & Wheeldon, Johannes (2013). Diagrammatic elicitation: Defining the use of diagrams in data collection. The Qualitative Report, 18(30), 1-12, https://nsuworks.nova.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1487&context=tqr [Accessed: December 7, 2019].

Woodgate, Roberta L.; Zurba, Melanie & Tennent, Pauline (2017). Worth a thousand words? Advantages, challenges and opportunities in working with photovoice as a qualitative research method with youth and their families. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung / Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 18(1), Art. 2, http://dx.doi.org/10.17169/fqs-18.1.2659 [Accessed: May 13, 2020].

John V. FLYNN† obtained his bachelor's degree in social work from the University of Ottawa in 2016, and earned a master's in social work and human rights at the University of Gothenburg in Sweden in 2018. He was a coordinator and researcher on the PROUD study, and was integrally involved in the authorship of the present article, leading the writing of the manuscript up until his untimely death in early 2019.

Contact:

c/o Bruyère Research Institute

43 Bruyère Street, Annex E

Ottawa, Ontario K1N 5C8, Canada

E-mail: ckendall@uottawa.ca

Claire E. KENDALL is an associate professor with the Department of Family Medicine, University of Ottawa; clinician investigator at the C.T. Lamont Primary Health Care Research Centre, Bruyère Research Institute; and a practicing family physician with the Bruyère Family Health Team. She is an adjunct scientist at ICES and in the Clinical Epidemiology Program at The Ottawa Hospital Research Institute. Dr. KENDALL holds a Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR) – Ontario HIV Treatment Network New Investigator Award in the area of health services/population health HIV/AIDS health services research. She is principal investigator on the Advancing Primary Healthcare for People Living with HIV in Canada (LHIV), a $2.5 million interdisciplinary and transnational CIHR Team Grant. Dr. KENDALL is also principal investigator on the PROUD study. Her research relies on multiple methodologies, including secondary analysis of the health administrative data held at ICES, primary collected cohort survey data, qualitative methods, and the meaningful involvement of patients and people with lived experience.

Contact:

Dr. Claire Kendall, MD CCFP MSc PhD

CT Lamont Primary Health Care Research Centre

Bruyère Research Institute

43 Bruyère St. Annex E

Ottawa, Ontario K1N 5C8, Canada

E-mail: ckendall@uottawa.ca

Lisa M. BOUCHER is a PhD candidate at the University of Ottawa, School of Epidemiology and Public Health, and trainee at the Bruyère Research Institute. She is a coordinator and researcher on the PROUD study. She is supported by a Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR) Doctoral Research Award: Priority Announcement – HIV/AIDS. In her research, she focuses on substance use, socioeconomic marginalization, and chronic health issues.

Contact:

Lisa M. Boucher

CT Lamont Primary Health Care Research Centre

Bruyère Research Institute

43 Bruyère Street, Annex E

Ottawa, Ontario K1N 5C8, Canada

E-mail: LiBoucher@bruyere.org

Michael L FITZGERALD is a research associate at the CT Lamont Primary Health Care Research Centre, Bruyère Research Institute in Ottawa.

Contact:

Michael L. Fitzgerald

CT Lamont Primary Health Care Research Centre

Bruyère Research Institute

43 Bruyère Street, Annex E

Ottawa, Ontario K1N 5C8, Canada

E-mail: MFitzgerald@bruyere.org

Katharine LAROSE-HÉBERT is an adjunct professor in the School of Social Work and Criminology at the University of Laval. Her research includes work on the organization and supply of mental health services, harm reduction and substance use, and judicialization and diversion of marginalized populations.

Contact:

Katharine Larose-Hébert

School of Social Work, Faculty of Social Sciences, Laval University

Charles de Koninck Hall, 1030, avenue des Sciences-Humaines

Québec, Québec G1V 0A6, Canada

E-mail: katharine.larose-hebert@tsc.ulaval.ca

Alana MARTIN is a community support worker at Somerset West Community Health Centre and harm reduction worker at Centretown Community Health Centre. She is a community research coordinator on the PROUD study.

Contact:

Alana Martin

PROUD Community Advisory Committee

CT Lamont Primary Health Care Research Centre

Bruyère Research Institute

43 Bruyère Street, Annex E

Ottawa, Ontario K1N 5C8, Canada

E-mail: alanamartinottawa@hotmail.com

Christine LALONDE is a community researcher with the PROUD Community Advisory Committee.

Contact:

Christine Lalonde

PROUD Community Advisory Committee

CT Lamont Primary Health Care Research Centre

Bruyère Research Institute

43 Bruyère Street, Annex E

Ottawa, Ontario K1N 5C8, Canada

E-mail: gertyandgladis@outlook.com

Dave PINEAU is a community researcher with the PROUD Community Advisory Committee.

Contact:

Dave Pineau

PROUD Community Advisory Committee

CT Lamont Primary Health Care Research Centre

Bruyère Research Institute

43 Bruyère Street, Annex E

Ottawa, Ontario K1N 5C8, Canada

E-mail: djpineau@gmail.com

Jenn BIGELOW is a community researcher with the PROUD Community Advisory Committee.

Contact:

Jenn Bigelow

PROUD Community Advisory Committee

CT Lamont Primary Health Care Research Centre

Bruyère Research Institute

43 Bruyère Street, Annex E

Ottawa, Ontario K1N 5C8, Canada

E-mail: jenn.bigelow.dual@gmail.com

Tiffany ROSE is a community researcher with the PROUD Community Advisory Committee.

Contact:

Tiffany Rose

PROUD Community Advisory Committee

CT Lamont Primary Health Care Research Centre

Bruyère Research Institute

43 Bruyère Street, Annex E

Ottawa, Ontario K1N 5C8, Canada

E-mail: rosetiffany83@gmail.com

Rob BOYD is the director of the Sandy Hill Community Health Centre's OASIS program, which provides harm reduction based health and social services (including HIV and Hepatitis C treatment) for people who use drugs who experience barriers to health and recovery due to stigma, poverty, criminalization and mental illness.

Contact:

Rob Boyd

Sandy Hill Community Health Centre

221 Nelson Street

Ottawa, Ontario K1N 1C7, Canada

E-mail: rboyd@sandyhillchc.on.ca

Mark TYNDALL is a professor in the School of Population and Public Health at the University of British Columbia. His research focuses on public health and disadvantaged populations. His current interests include addiction, poverty, homelessness, drug overdose, drug policy, and harm reduction including supervised injection sites, regulated drug distribution and nicotine harm reduction (e-cigarettes/vaping).

Contact:

Mark Tyndall

School of Population and Public Health, Faculty of Medicine

University of British Columbia

2206 East Mall

Vancouver, British Columbia V6T 1Z3, Canada

E-mail: mark.tyndall@ubc.ca

Zack MARSHALL is an assistant professor in the School of Social Work at McGill University. Building on a history of community work in the areas of HIV, harm reduction, and mental health, he explores interdisciplinary connections between public engagement, knowledge production, and research ethics.

Contact:

Zack Marshall

School of Social Work

McGill University

3506 University Street Suite 300, Wilson Hall

Montreal, Québec H3A 2A7, Canada

E-mail: zack.marshall@mcgill.ca

Flynn, John V.; Kendall, Claire E.; Boucher, Lisa M.; Fitzgerald, Michael L.; Larose-Hébert, Katharine; Martin, Alana; Lalonde, Christine; Pineau, Dave; Bigelow, Jenn; Rose, Tiffany; Boyd, Rob; Tyndall, Mark & Marshall, Zack (2020). "It's Like the Pieces of a Puzzle That You Know": Research Interviews With People Who Inject Drugs Using the VidaviewTM Life Story Board [57 paragraphs]. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung / Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 21(3), Art. 5, http://dx.doi.org/10.17169/fqs-21.3.3459.