Volume 22, No. 2, Art. 1 – May 2021

Participatory Childhood Research With Concept Cartoons

Raphaela Kogler, Ulrike Zartler & Marlies Zuccato-Doutlik

Abstract: Participatory research with children is frequently characterized by adaptations of methods intended to embrace children's perspectives as co-researchers. Within the framework of a participatory qualitative study on the issue of divorce, a method deriving from the didactics of teaching was advanced. For the first time in social science research with children, the method was made useable for research with children: Concept cartoons, in which text-based and visual elements are interconnected, assist in encouraging children to engage in discussions and in involving them in various phases of the research. In this article, we present this approach to the participatory development and application of concept cartoons. The joint process of designing and using concept cartoons with 60 eight- to ten-year-old children elucidated the important incentives for discussion, as well as the potential this methodological approach has as a participatory research tool. The use of concept cartoons in this study made it possible to reconstruct children's associations and experiences and to gain insight into their concepts of parental divorce. Based on the participatory prospects in childhood research, we introduce the method and its potential, while highlighting participatory development and the pathways to application in social science research with children.

Key words: childhood research; concept cartoons; participatory research; group discussions; visual methods; sociology of childhood

Table of Contents

1. Participatory Research With Children

2. Concept Cartoons

2.1 Elements of concept cartoons

2.2 Concept cartoons in the didactics of teaching

3. Concept Cartoon Discussions as a Social Science Research Method

3.1 The participatory development of concept cartoons

3.2 The implementation of concept cartoon discussions

3.3 Texts and images in discussion process

3.4 Analysis and further development

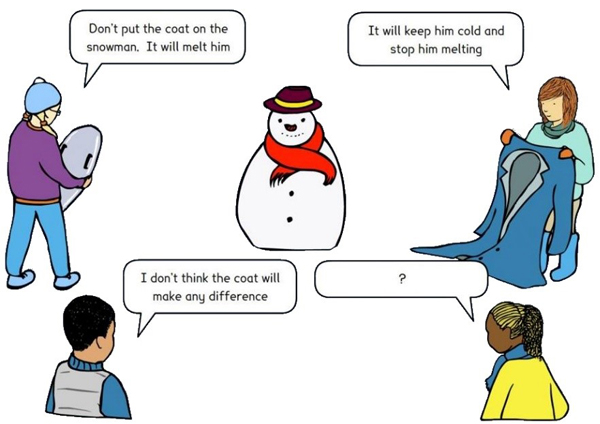

4. Conclusion: Concept Cartoons in Social Science Childhood Research

1. Participatory Research With Children

Participatory research approaches have been strongly enhanced over the past years (BERGOLD & THOMAS, 2012; VON UNGER, 2014; WÖHRER, ARZTMANN, WINTERSTELLER, HARRASSER & SCHNEIDER, 2017). In this process, the degree of participation has varied among non-scientists and their possibilities to help shape and develop the research process. Participatory researchers focus on dialog and partnership with co-researchers in many ways (HAFENEGER, 2005; MOSER, 2010). An open and cyclically organized style of research that allows for co-constructions of knowledge is extensively considered to be a consensus. Joint democratic decision-making and self-determination are also increasingly aspired to in research projects with young people (BETZ, GAISER & PLUTO, 2010; HUNLETH, 2011; RIEKER, MÖRGEN, SCHNITZLER & STROETZEL, 2016; ROSS, 2017). At the latest since the 1990s, the sociology of childhood has advocated the hypothesis that research should principally be done with and not on children and that children are to be seen as competent social actors with their own rights. The concepts of childhood as a socially constructed life phase and children as social actors who articulate their points of view independently are pivotal (ALANEN, 2014; HONIG, 2009; JAMES & JAMES, 2012; MEY & SCHWENTESIUS, 2019). The sustained boom of participatory projects in childhood research is intended to offer more than a mere collection of childlike subjective perspectives (ALDRIDGE, 2017; EßER & SITTER, 2018; GROUNDWATER-SMITH, DOCKETT & BOTTRELL, 2015). Questions as to how and to what extent children's impulses can be integrated in research, and in what way children can possibly be involved in developing research tools, have been the matter of debates on the methodical and methodological aspects of children's participation. [1]

In participatory research with children, researchers often face the challenges of method combinations in an attempt to ensure participation. Adaptations of methods are also frequently found, while flexibility in the research process is a central premise in including children (BARKER & WELLER, 2003; BENDER, 2011; CLARK, 2010; GROUNDWATER-SMITH et al., 2015; WYNESS, 2013; ZARTLER, 2014, 2018a). However, the possibilities of participation are diverse and there is no standardized approach in participatory research. Instead, there are various models to exemplify degrees of participation in research. The so-called ladder of participation is most frequently used as a stage model. Based on ARNSTEIN (1969), who was the first to publish this eight-rung ladder, participatory studies continue to work with this hierarchical model which in part has been adapted (e.g., FRANCIS & LORENZO, 2002; VON UNGER, 2014; WRIGHT, VON UNGER & BLOCK, 2010). Co-researchers' participation extends from non-participation to self-led and self-determined research. HART (1992) adapted this ladder for use in research with children and adolescents by transforming the rungs to actions and aligning them with the requirements of child-related research. The spectrum ranges from children's decorative participation, informative involvement and consultation, active collaboration, and codetermination to self-administered projects (ERGLER, 2017; WRIGHT et al., 2010). Meanwhile, as research at a higher rung of the ladder does not per se imply higher quality, and as participation does not need to be warranted to the same extent in all stages of participatory studies, criticism has become more frequently leveled against the use of the participation ladder. Children's collaboration should not be considered less beneficial than research determined by children themselves (ERGLER, 2017; EßER & SITTER, 2018). [2]

Especially in childhood research, participatory projects have been carried out with various possibilities to become involved in the research process. There is a common fundamental agreement in participatory projects with children to strive for facilitating research from children's perspectives, not to research on but with them, and to give them a voice (MAND 2012; MASON & WATSON, 2014; ROSS, 2017; WALLER & BITOU, 2011; ZARTLER, 2018a). Participatory research is not intended to instrumentalize children as alibi participants, but rather to take them seriously as co-researchers, as research would not be possible without their involvement:

"The question may become obsolete as to whether children 'fit' a chosen approach in research methodology. Children would thus be able to participate in co-creating and 'reworking' the research situation to find the form of expression that suits them. Only then will qualitative reconstructive childhood research meet the claim to the object adequacy of its methods" (NENTWIG-GESEMANN, 2013, p.763).1) [3]

Attention must be paid to questions regarding dependencies and negotiation processes between (adult) researchers and children in terms of generational order; to questions regarding research ethics, data protection and possible implications for the results of scientific publications; and to the extent of possible participation. The methods frequently applied in childhood research are also adequate for research with adults, for which they originally were conceived. In part, these methods have been adapted. However, children are "researched" with ethnographic methods and without self-determined elements instead of seeing them as active subjects and treating them as such (PUNCH, 2002). Reducing the hierarchical divide between adults and children to the largest extent possible can reveal new perspectives on a given research object (ATKINSON, 2019; CHRISTENSEN & PROUT, 2002; EßER & SITTER, 2018; GALLACHER & GALLAGHER, 2008; GALLAGHER, 2008; WILLUMSEN, HUGAAS & STUDSROD, 2014; ZARTLER, 2018a). [4]

Participatory studies with children increasingly apply visual methods: Researchers from various disciplines have proposed combinations of traditional qualitative methods (group discussions, interviews, and participant observations) and visual techniques in an attempt to generate opportunities to participate and to integrate children's perspectives with the aid of visual forms of expression. This process potentially empowers children to become involved independently from language-related or text-based input (CLARK, 2010; ELDÉN, 2013; GRANT, 2017; GUILLEMIN & DREW, 2010; HORGAN, 2017; JOHNSON, PFISTER & VINDROLA-PADROS, 2012; MANNAY, 2016; NENTWIG-GESEMANN, 2007). The growing number of arts-based research with children also points to the potentials of combined visual, narrative, and text-based techniques in childhood research (BLAISDELL, ARNOTT, WALL & ROBINSON, 2019; LEAVY, 2019; MAND, 2012). In this context, methodically sound and systematically applicable visual, participatory methods are increasingly being searched for. [5]

Derived from an educational context, concept cartoons are a methodical approach that was especially developed to be applied with children and that may be considered a child-centered method due to its visual character. With concept cartoons, children can discuss various standpoints from their own perspectives, and their statements can be made accessible for social science research. Although group discussions and focus groups with children are key to the spectrum of childhood research methods (GIBSON, 2012; LANGE & MIERENDORFF, 2009; MORGAN, GIBBS, MAXWELL & BRITTEN, 2002; VOGL, 2014, 2015), and visual methods and aids are also being more frequently applied (ELDÉN, 2013; FASSETTA, 2016; HORGAN, 2017; KOGLER, 2018; ZARTLER, 2014; ZARTLER & RICHTER, 2014), to our knowledge, concept cartoons have not yet been used in social science research with children. This is remarkable, particularly in view of the numerous advantages such concept cartoons offer to scientific application. This research gap formed the methodical basis for a study in which concept cartoons on the issue of divorce and separation were developed and discussed with eight- to ten-year-old children in a participatory manner (ZARTLER, KOGLER & ZUCCATO-DOUTLIK, 2020). [6]

Concept cartoon discussions are based on visual elements. The objective of using single images with speech bubbles is to present concepts and notions regarding a defined theme in the form of illustrations and to stimulate discussions. Derived from the didactics of natural science teaching, concept cartoons provide an enormous potential for child-oriented social research: Children themselves can substantially help to form the instrument already in the phase of development, while bringing in their perspectives on the research topic. Based on qualitative group discussions, the children's ideas, opinions, and general concepts can be captured in discussing visual, text-based, and creative elements. Moreover, children can independently develop concept cartoons on a research topic. This method is thus located at the interface between visual and verbal empirical methods. [7]

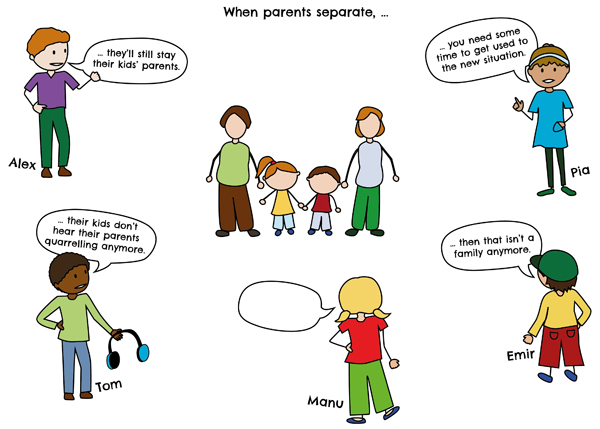

In the following, we will present concept cartoons and their original use in the didactics of teaching (Section 2); review their development and application as a social science research method on the basis of an example from our research practice (Section 3); and discuss the potentials, advantages, and challenges of concept cartoons in participatory research with children (Section 4). [8]

In general, cartoons refer to stories consisting of several images with consecutive strands and characters. In colloquial speech, such cartoons are also called comics. By contrast, the term concept cartoon relates to a single image in which a group of fictional persons converses about a certain topic (STEININGER, 2016, 2017). Concept cartoons and comics have in common that the focus is on the linkage of images and writing, and thus of visual and verbal sign systems, which lead to constitutions of meaning (DÖRNER, 2007; GRÜNEWALD, 2000). [9]

Occasionally referred to as concept dialogs in educational science (SCHOMAKER & LÜSCHEN, 2012), concept cartoons have been in use in school teaching for some years (KEOGH & NAYLOR, 1999; STEININGER, 2017). Characteristically, concepts that are central issues of such cartoons serve as starting points for debates. An everyday life relationship is established with an illustration of the topic in the form of a single image and several text elements, in which drawn concept cartoon characters (cartoon figures) discuss a topic with speech bubble statements. Combining text-based and graphic elements, concept cartoons, their core elements, and didactic importance will be introduced in the following. We will then refer to current experiences with this methodological approach. [10]

2.1 Elements of concept cartoons

Concept cartoons are made up of visual parts (an image and concept cartoon characters) and text-based elements (a title or guiding question and statements in speech bubbles), with which a topic is jointly negotiated.

Image: The center of a concept cartoon is occupied by an illustration of the thematic contents, which takes up relatively most space. The image determines the theme visually, which is an advantage for visually interested children as opposed to text- or language-based techniques. The visual representation also serves as a conversation stimulus by standing both in the center of the concept cartoon for the observers (children) and, in terms of contents and space, in between the cartoon characters grouped around. Upon initial perception, the image elucidates the topic of discussion, while stimulating the observers' phantasy and communication.

Concept cartoon characters: Concept cartoons contain characters or figures that vary as to number, characteristics, and appearance depending on the (research) context. Three (e.g., MIN-JIN & CHING-DAR, 2011) to eight figures (e.g., BUCHBERGER, EIGLER & KÜHBERGER, 2019) can be found in the cartoons. The characters are arranged around the illustration in a semicircle or circle, thus symbolizing a conversational situation. They are intended to allow the discussants to (culturally and socially) identify themselves with the figures which are adapted to the target group in terms of age and appearance (YIN & FITZGERALD, 2017). It has been recommended to diversify characteristics and apply various categories of diversity in order to reproduce social pluralism (BUCHBERGER et al., 2019; KABAPINAR, 2009). The figures' diversity and distinctness trigger sympathy or dislike among the observers and thus subsequently invigorate the discussion of contents. Children pay close attention to the characters' visual representation and address their clothes, hair and skin colors, facial expression and gestures, and their postures. It is advisable to give the characters first names in the development phase: Based on comparative experimental designs, for example, KABAPINAR (2009) established that name-bearing figures are more efficient and more strongly stimulate discussions than anonymous and alternating figures.

Title and/or guiding question: Concept cartoons generally have titles, with which the topic to be discussed is described (based on the centrally positioned image) and which are mostly phrased as guiding questions, statements, or texts to be completed. The title of a concept cartoon is to build on the discussants' and cartoon characters' everyday worlds and to be easily comprehensible.

Speech and/or thought bubbles: The concept cartoon characters' textual statements regarding the negotiated topic are a key element in terms of methodology. The short, comprehensible, and concise statements serve to take up specific attitudes towards the topic and/or an answer to the question formulated in the title. As to contents, the statements are to express controversial perspectives and stimulate discussion. Both colloquially formulated ideas and misinformation or scientific theses in the statements can thus be reflected. It is not the purpose of this method to identify one single appropriate answer, but rather to induce the discussants' thoughts and arguments (STEININGER, 2016, 2017; STENZEL & EILKS, 2005). Therefore, at first sight, the characters' individual statements should ideally appear to be plausible and of equal value. The statements in the speech or thought bubbles are graphically and individually allocated to the characters. In addition, many concept cartoons contain an empty speech or thought bubble (e.g., NAYLOR & KEOGH, 2014 [2000]). Such empty bubbles are intended to epitomize to the observers that there may also be different ideas, notions, and arguments regarding the topic. This way, the discussants are to be animated to independently formulate their own answers—an idea based on the didactic techniques of text completion. [11]

2.2 Concept cartoons in the didactics of teaching

Concept cartoons were originally used as a didactic method in the educational setting. In the 1990s, NAYLOR and KEOGH in England developed and tested concept cartoons with the aim to advance problem-oriented learning among students (KEOGH & NAYLOR, 1997, 1999; NAYLOR & KEOGH, 2013, 2014 [2000]; NAYLOR, KEOGH & DOWNING, 2007). The didactic application of concept cartoons is based on the (learning) theories of social constructivism. These theories take into account that children construct their knowledge through interaction, both by dealing with the illustrations, cartoon characters, and textual elements, and with the students and teachers who are present (NAYLOR & KEOGH, 1999; BALTA & SARAC, 2016). Proceeding from the assumption that children are able to phrase distinct perspectives, these concept cartoons invite them to playfully participate in a fictional discussion of the illustrated figures (STEININGER, 2017). Such social interactions between peers promote critical thinking and reasoning rather than asking the children ex cathedra knowledge questions about the topic. The children can argue via the characters' statements and do not have to disclose their own opinions. Concept cartoons can thus reinforce the childrens' competencies (SHURKIN, 2015) and are seen "as a methodical answer to the question as to how constructivist learning theory, scientific concepts, and learning at school can be related to one another" (BUCHBERGER et al., 2019, p.6). [12]

Applying concept cartoons as a teaching strategy for problem-oriented, active and collaborative learning in discussions is considered to be a substantial didactic element (BALIM, INEL-EKICI & ÖZCAN, 2016; DABELL, 2008; JAMAL, IBRAHIM & SURIF, 2019; KOVALAINEN & KUMPULAINEN, 2005; YIN & FITZGERALD, 2017). This active form of learning stimulates children to develop thinking and solution strategies by formulating unmediated thoughts and ideas with regard to a given topic. Based on the different arguments and responses in the speech bubbles, children recognize that various perspectives, ideas and ways of processing information are possible. The application of concept cartoons has proven itself in small groups, in which more intensive discussions take place between the participants, rather than in pairs or in classroom settings (STEININGER, 2017; STRANDE & MADSEN, 2018). Using concept cartoons enhances critical negotiations of contents and may reveal knowledge needs (WOOLMAN, 2019; YIN & FITZGERALD, 2017). At once, integrating several plausible, scientific standpoints that are close to everyday life into the bubble texts can serve to illustrate the diversity of a topic (BUCHBERGER, et al. 2019; FENSKE, KLEE & LUTTER, 2011; SHURKIN, 2015). By considering and discussing the concept cartoons, the learners are to empathize with the cartoon characters' possible world of experience and relate to their patterns of explanation and reconstructions. Logical thinking and reasoning are promoted and everyday life concepts with less explanatory power are jointly identified and scrutinized within the group (LEMBENS & STEININGER, 2012). [13]

This application of concept cartoons also contributes to reducing the complexity of a topic by means of visual and text-based elements (NAYLOR & KEOGH, 2013). The numerous variants of adaptation facilitate such applications with various age groups (JAMAL et al., 2019): By now, concept cartoons have been developed for grade and secondary schoolers alike, and the approach is put to use worldwide in various teaching subjects. Apart from natural science teaching, these cartoons are applied in math classes (DABELL, 2008; SEXTON, GERVASONI & BRANDENBURG, 2009), in fostering economic thinking (YIN & FITZGERALD, 2017), and in history lessons (BUCHBERGER et al., 2019). In Europe, concept cartoons have been used particularly in England and Turkey (e.g., TOKCAN & TOPKAYA, 2015). Many examples can also be found in German-speaking countries, primarily in natural science teaching (BARKE, ENGIDA & YITBAREK, 2009; LEMBENS & STEININGER, 2012; STEININGER, 2016, 2017; STENZEL & EILKS, 2005). Apart from topical subjects and divergent country-specific contexts, concept cartoons have occasionally been developed with regard to attitudes and social value judgments (FENSKE et al., 2011; HORLOCK, 2012), as well as in political and social science lessons (KÜHBERGER, 2017). Discussions published in the didactic literature have also focused on how concept cartoons can find their way into teaching as a digital tool (AKAMCA, ELLEZ & HAMURCU, 2009; YIN & FITZGERALD, 2017). [14]

KEOGH and NAYLOR (1997) developed the initial concept cartoons for natural science classes to stimulate discussions between students and encourage them to reason their own thoughts and ideas. Illustration 1 shows a classic example which NAYLOR and KEOGH (2014 [2000]) adapted and published in an anthology of natural science concept cartoons.

Illustration 1: Classic concept cartoon (NAYLOR & KEOGH, 2014 [2000], p.44)2) [15]

This concept cartoon illustrates a natural science concept (the state of aggregation) by reference to the question as to what would happen if a snowman were dressed with a coat. The four depicted concept cartoon characters express different ideas in this connection. Conducting various discussions about this cartoon in various grades with 8- to 14-year-old children, KEOGH and NAYLOR (1997, 1999) established that the concept cartoon served to enhance the disposition to discuss and learn natural sciences. By the same token, interest was also more generally aroused in the subject matter. Follow-up studies demonstrated further positive effects, such as shy and reserved children involving themselves by overcoming language barriers, or understanding of and relating to third parties' problem-solving strategies in terms of problem-centered learning (NAYLOR & KEOGH, 2013). Based on these insights, (English-language) concept cartoons were abundantly developed for natural science education (NAYLOR & KEOGH, 2014 [2000]; TURNER, SMITH, KEOGH & NAYLOR, 2014). With much nuance, STEININGER (2016, 2017) dealt extensively with the concept cartoon technique in chemistry courses. She showed variations, such as teachers who distributed concept cartoons with exclusively empty bubbles among the students and who thus were able to capture ideas about the topic without effects coming from preformulated perspectives. [16]

In spite of the divergent ways in which concept cartoons have been implemented, a great many advantages of this method have been identified: Educationalists are in agreement about the fact that access to and interest in a topic can be facilitated and increased (BIRISCI, METIN & KARAKAS, 2010; CHIN & TEOU, 2009; STEININGER & LEMBENS, 2011; STENZEL & EILKS, 2005). Furthermore, subject contents can be specifically imparted with concept cartoons, thus contributing to disseminating knowledge (EKICI, EKICI & AYDIN, 2007; KEOGH & NAYLOR, 1999; ORMANCI & SASMAZ-ÖREN, 2011; STEININGER, 2017). In addition, discussing such cartoons reveals knowledge gaps in a playful fashion. This teaching aid helps children question their own standpoints, values, and knowledge by empathizing with other children and cartoon characters who are present (BARKE et al., 2009; BIRISCI et al., 2010; BUCHBERGER et al., 2019; FENSKE et al., 2011; HORLOCK, 2012; KABAPINAR, 2009). The advancement of argumentations and discussions among children is an important objective in working with concept cartoons. Stimulated by these cartoons, the discussants can put ideas into words, autonomously bring in their knowledge and everyday life experiences with the topic, express assumptions, and phrase counterarguments (KAPTAN & IZGI, 2014; LEMBENS & STEININGER, 2012; NAYLOR et al., 2007; SHURKIN, 2015; STEININGER, 2017; WOOLMAN, 2019). These experiences in the didactics of teaching point to the large potential associated with concept cartoons as a social science method. [17]

3. Concept Cartoon Discussions as a Social Science Research Method

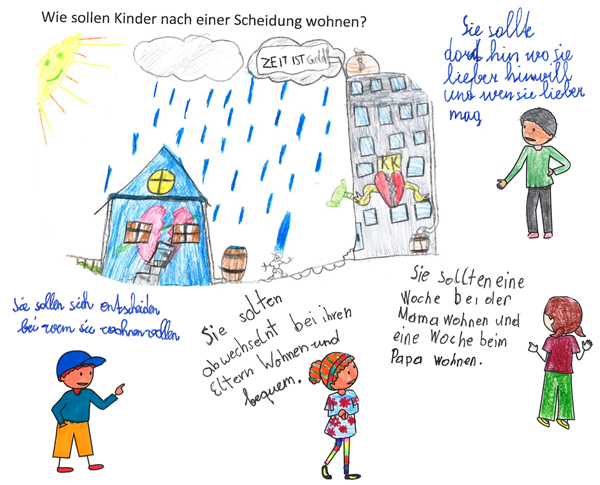

Studies about concept cartoon discussions as a didactic method sporadically indicated that, due to their adaptability, such discussions could also be applicable as a method of inquiry and research, or at least in teaching social sciences, in an attempt to capture children's perspectives (BUCHBERGER et al., 2019; FENSKE et al., 2011; JAMAL et al., 2019; KAPTAN & IZGI, 2014; STEININGER, 2017). In psychologically oriented social research, qualitative vignettes have occasionally been applied as a stimulus in writing in order to generate narrations (BARTER & RENOLD, 2000; JENKINS, BLOOR, FISCHER, BERNEY & NEALE, 2010). Less frequently, single images (O'CONNELL, 2013) and illustrated stories (DÖRNER, 2007) have been applied as vignettes. However, the development and application of concept cartoons as an instrument of social science inquiry in participatory childhood research is a novel approach, which we used and adapted in the framework of a study and which is presented in the following. [18]

3.1 The participatory development of concept cartoons

In our study, SMiLE – Scheidung mit Illustrationen erforschen (SMiLE – Exploring Divorce with Illustrations; 2017-2019)3), concept cartoons were adapted for the first time in childhood research to assess children's perspectives and communication processes. In terms of context, the objective of this investigation was to appreciate children's concepts and bodies of knowledge regarding parental divorce. One of the starting points was the suggestion that children aged eight to ten years develop thoughts concerning separation and divorce regardless of their own family situations. Current notions in communicative exchange with peers were at the core of this study rather than subjective experiences of one own parents' separation. Apart from content-related questions regarding the children's concepts in the context of divorce research (ZARTLER, 2018b, 2021; ZARTLER et al., 2020), we investigated the methodical and methodological question as to how concept cartoons and related discussions can be applied in social science research with children. [19]

In this framework, 60 students (30 girls and 30 boys) growing up in various family forms worked together with us on this topic. Four school classes of an urban and a rural region of inquiry in Austria participated in. The two regions were selected on the basis of content-related criteria (e.g., divorce frequency, infrastructure) along the lines of a most-different-cases research design (ANCKAR, 2008; BEHNKE, BAUR & BEHNKE, 2006). All children from the participating classes were allowed to participate in the study. We spent more than 100 hours with the children during regular class time. Based on an innovative participatory research approach (CLARK, 2010; GROUNDWATER-SMITH et al., 2015; VON UNGER, 2014), concept cartoons were developed and applied as assessment instruments together with the children. The children were continuously involved in the research process—in specifying the thematic orientation of the individual cartoons in terms of the overall topic of parental divorce, in the content-related and graphic development of the cartoons (construction of the assessment instrument), and in the assessment. Moreover, the children participated by giving feedback regarding the results of the evaluation and in disseminating and presenting the results. A multi-method research design included a multitude of child-oriented possibilities to participate (games, short stories, etc.). This participatory approach allowed us to gradually develop and subsequently apply concept cartoons about parental separation and divorce. Guidelines on research ethics were carefully adhered to and the participating children's rights as competent subjects were observed (ALDERSON & MORROW, 2011; CHRISTENSEN & JAMES, 2017; CHRISTENSEN & PROUT, 2002; ZARTLER, 2018a). [20]

The concept cartoons were developed in three phases of the SMiLE study: 1. Identification of the children's concepts by means of qualitative group discussions as a basis for developing the topics, guiding questions, illustration ideas, and speech bubble statements; 2. Preparation of visual materials by the participating children and collection of their ideas and notions in the form of handicraft pictures and drawings; 3. Further text-based and graphic development as well as communicative validation of the concept cartoon discussions with the children. These three phases are presented in the following.

Identification of concepts: Children can conduct open, dynamic conversations in group discussions, thus making it possible to systematically work out the participants' interactions, collective orientations, and relevant themes at the manifest level (FLICK, 2011; MORGAN et al., 2002; VOGL, 2011, 2015). Group discussions are familiar to children from everyday school life and offer the possibility to react to peers' statements. In developing the concept cartoons in the SMiLE study, group discussions primarily served to reconstruct the children's current concepts and knowledge of separation and divorce. In order to systematically capture their fundamental ideas and notions, twelve qualitative group discussions were carried out. The group sizes and lengths of discussions varied between three and seven participants and 1.5 and 2 hours, respectively. In each case, three thematic areas were put up for discussion: a) family definitions and images; b) general understanding about the meaning and process of divorce and separation; and c) possible changes related to divorce and separation for children and other family members. During many research stays, and together with the children's other contributions, their elicited ideas served as a basis for the way in which the thematic concept cartoon contents were aligned.

Preparation of visual materials: In order to gather the participating children's verbal and visual inputs regarding the topic, they repeatedly crafted visual materials in our presence in the classes. Both individually and in groups, the children were able to realize their ideas freely and creatively in the form of handicraft pictures and drawings, thus making important self-determined contributions to developing the concept cartoons. For example, the children expressed imagined divorce processes and addressed ritual actions in their illustrations, such as discarding wedding rings as symobolizing a terminated partner relationship. They also dealt with living situations following parental separation, custody and contact regulations, and parental controversies. In doing so, they used many symbols, including broken hearts and thunderbolts.

Further development and communicative validation: The content-related and graphic implementation of the concept cartoon elements in the SMiLE study was discussed with a scientific board consisting of experts in developmental psychology, educational science, didactics, family law and family court assistance, counseling, and method development. For the most part, the ideas the participating children formulated for the individual cartoons and their statements during the group discussions were only slightly adapted. Their visual materials were graphically processed and, together with the speech bubble texts, communicatively validated with the children. This was done by discussing cartoon interpretations and designs and obtaining feedback regarding the methodic approach (LEGEWIE, 1987; MEYER, 2018; MRUCK & MEY, 2000). [21]

The group discussions were analyzed by applying thematic coding (FLICK, 2011), the documentary method (BOHNSACK, 2014) and by integrating the children's visual materials. As a result, four thematic sets of issues were identified and20 concept cartoons were developed: family images, parental separation and the divorce process, changes following divorce, and actors in the divorce process. Attention was paid to the variability of subtopics within the four thematic sets and to the generation of various types of concept cartoons: The cartoons designed either focused more strongly on the children's current state of knowledge and notions (knowledge cartoons) or chiefly supported their discussions and reasoning (discussion cartoons). During the phase of development, scientific insights from divorce research as well as the children's contributions, which were in part taken over verbatim, were considered in the formulated bubble statements. In this way, for example, a discussion cartoon with the title "How do children celebrate their birthdays after a divorce?" and a knowledge cartoon, "What are half siblings and step siblings?," were developed. The 20 concept cartoons with 80 speech and thought bubbles thus illustrate topics relevant to the children and possible perspectives in children's everyday language. [22]

In graphically preparing the illustrations, we paid attention to making the image elements visually representing the topic easily identifiable and comprehensible to the children. On the one hand, the children's handicraft pictures and drawings were used as an inspiration and foundation, discussed in the classroom, and graphically processed. On the other hand, the participating children were explicitly asked how they would graphically represent certain topics or issues. [23]

Five concept cartoon characters were developed based on the children's input and experiences drawn from available didactic studies. These individual characters articulate different ideas and assumptions regarding a graphically visualized topic. We were mindful of variety and chose corresponding first names in developing the figures. It is important to avoid the names of the children or teachers participating (in the study) as well as highly unusual and long names that are difficult to read or unknown within the given sociocultural context. In designing the characters by the names of Alex, Emir, Manu, Tom, and Pia, we considered various characteristics and categories of diversity: For instance, the first name Emir was chosen to integrate a frequently used name from a cultural background known to the children (about one fourth of the children participating in the SMiLE study had a migration background). The figures Alex and Manu were deliberately given gender-neutral first names, while gender-stereotypical appearances (such as clothing) were avoided. In allocating the speech bubbles to the individual characters, attention was paid to variation, such that the figures were not to be continuously identified with the same similar (e.g., particularly elaborated or strongly controversial) statements or only with empty bubbles. Furthermore, the concept cartoon characters became "stereotypical figures [...] whose answers are classed as right or wrong from the very start" (BUCHBERGER et al., 2019, pp.7f.). After the developmental phase, the 20 concept cartoons underwent a pretest in that they were presented to children of different ages who were not involved in the study and who were asked for their comments. [24]

Each concept cartoon contained all the characteristic elements mentioned above: an illustration in the center, characters with the children's concepts in speech bubbles, a figure with an empty bubble, and a title. Illustration 2 shows one of the cartoons developed on the issue of parental separation and the divorce process, which is outlined in the following.

Illustration 2: "When parents separate"4) [25]

This concept cartoon integrates the childrens' thoughts and ideas as articulated in the open group discussions. Alex formulated the concept of "parental separation as the dissolution of a partner relationship" ("When parents separate, they'll still stay their kids' parents"). This figure is intended to impart the concept and put it up for discussion, that parental divorce does not equal the termination of the parent-child relationship. Furthermore, the changes going along with separation are addressed by translating the notion of "divorce means changes that initially cause insecurity" in Pia's statement into the involved children's words ("When parents separate, you need some time to get used to the new situation"). Emir formulated another relevant topic from a child's perspective: changes in family constellations and borderlines due to parental divorce ("When parents separate, then that isn't a family anymore"). This statement puts the diversity of family definitions up for discussion and was taken quite controversially by the children involved. The issue of parents quarreling before, during, and after separation, which is critical to children, was integrated into the cartoon with the statement "When parents separate, the kids don't hear their parents quarreling anymore." [26]

In visual terms, one frequently mentioned and drawn family constellation was chosen as an illustration: two children holding hands in between a man and a woman. The depicted family members were deliberately not given facial features or mimic movements in order to stimulate discussions in the absence of shown emotions and to avoid predetermining interpretations of the guiding statement "When parents separate" by depicting laughing and cheerful or sad and crying faces. The headphones in Tom's left hand are another graphic element. This was inserted as the children participating in the group discussions mentioned several strategies applied not to be forced to hear their parents quarreling, including the use of headphones. An empty speech bubble was assigned to the concept cartoon character Manu. [27]

3.2 The implementation of concept cartoon discussions

The 20 concept cartoons developed in the SMiLE study were the subject of 115 discussions with the involved children. In small groups of three to seven children, several thematically different cartoons were viewed and discussed in one- to two-hour rounds of discussion. The individual cartoons stimulated discussions of various lengths. On average, the children debated the cartoons for approx. 15 minutes, whereas that shown in Illustration 2 animated the participating children to engage in approx. twice as long conversations. [28]

In order to elucidate our application in practice, the concept cartoon discussions about the "When parents separate" concept cartoon are presented in the following. Before the discussion, a researcher functioning as moderator explained the purpose and process to the small groups. It was emphasized that the questions were not skill questions and that it was not the objective to identify correct answers in the speech bubbles. The children were given a cartoon they had not developed themselves, but rather had been co-constructed by other participants in the study. The children were motivated to empathize with the concept cartoon characters' statements and explanations, to join fictional discussions between the discussants, and to exchange views. The A4 format, color-printed and laminated cartoon was presented to the children, most of whom were sitting in a (semi-) circle. The moderator then asked stimulating questions regarding the conditions related to how the childrens' thoughts had emerged and their contexts ("Why do you think so?"; "Where have you heard that from?"). All conversations were recorded with audio equipment and transcribed verbatim. [29]

Ideal-typically, and based on STEININGER (2017, pp.79ff.), the course of a concept cartoon discussion can be structured in three phases: orientation, argumentation, and interaction/cooperation. These phases shift repeatedly during a narration, with various types of accounts taking place and, at once, various sorts of data developing at the verbal, text-based, and visual levels. The biographical experiences and knowledge of those involved are incorporated into the discussion, together with experiential and orientational knowledge from the media and other sources of information. [30]

The orientation phase is at the beginning of a concept cartoon discussion: The participants comment on and interpret the image and text and relate this directly to subjective experiences and bodies of knowledge. During this initial phase, children are occasionally surprised at the topic or the arguments phrased in the bubbles, which may lead to their wanting to know more about the topic from one another and from the moderator. The initial interpretations and statements regarding the "When parents separate" cartoon in this phase were diverse, which was associated especially with the children's diverse perspectives and experiences. In part, they asked other participants in the small group—and at times, the children they supposed had gone through parental separation—personal questions regarding the topic. In this phase, some children talked about their experiences with parental separation, such as Ines5) (single-parent family): "I was so, well, I can breathe at last." [31]

In the argumentation phase, the participants narrate and reason ideas and thoughts regarding the topic in order to identify points of reference and explanations for the concept cartoon characters' statements as well as their own notions. In addition, they explain their own definitions and advocate their subjective perspectives, for instance, by outlining their understanding of a topic upon other children's request, e.g., divorce is "when parents don't see each other anymore" (Larissa, nuclear family). The argumentations regarding the "When parents separate" cartoon were linked to the children's individual concepts in that statements were corroborated with their own family images: "For example, if I've got a teddy bear that I really love, then it also belongs to my family" (Teresa, nuclear family). In this connection, it was shown that the orientation and argumentation phases can be distinguished in ideal-typical terms, yet they tend to merge during the discussion. Using concept cartoon discussion offers the advantage that the participants can express their arguments regardless of their own biographical experiences. The possibility to make statements about the characters rather than about themselves, and thus to become involved in the conversation, motivated the children in our study to participate even if they did not want to or could not share their own experiences. In the depersonalized argumentations, they made use of imagined images to elucidate their reasoning: "For me, that [when parents separate] would actually almost be like a, a half-burnt forest. Because you lose half of the forest, that's like losing half of the family" (Milena, single-parent family). [32]

The argumentations and explanatory strategies did not exclusively refer to the concept cartoon characters' and children's statements, but also to the illustration in the center of the picture, which thus functioned as a statement itself. In the present case, it was repeatedly discussed which of the two children in the center could be living with which parent following divorce:

"They have two kids, like there, and the father goes somewhere else with the son and the mother stays, because he's got the color of his eyes and the color of his skin and hair from him, then he goes along with Papa and goes somewhere else. And the mother and the girl stay at home" (Zuzy, stepfamily). [33]

The interaction and cooperation phases are central to the narration and conversation process, in which the discussants deliberate, defend their own and other figures' and children's comments, identify themselves with statements, and contradict presented arguments. By bringing in a variety of several people's concepts, the participants are guided by those people's bodies of knowledge and observations while putting forth inquiries and counterquestions. At the same time, statements made by those present and the cartoon characters are doubted or attempts made to convince the other participants of one's own ideas. In the SMiLE study, this was done by referring to the potential consequences of parental divorce: "But maybe when they separate, it may also be that one of the parents becomes gay or lesbian. Then the kid's got a stepmother, so to say" (Milena, single-parent family). The children also deliberated cooperatively to find plausible answers and identified parallels between the concept cartoon characters' and their own perspectives, or those of others present:

"Weronika: Emir's right that it isn't a family anymore. It's a family, but they don't live together anymore and they don't have a child together anymore.

Zuzy: They don't spend much time together anymore. But you say he's right. That's no family anymore if you say he's right!

Weronika: Yeah, because they don't have much together.

Zuzy: But they're still a family" (Weronika, nuclear family; Zuzy, stepfamily). [34]

Occasionally, the children aligned or identified themselves with concept cartoon characters, or defended their statements: "So, I believe Alex is right, because they, when they separate, then they're still parents because they made the child" (Anka, stepfamily). They also came up with biographical events for the figures by assuming that a cartoon character would also have separated parents or would be going through a separation. This applied especially to the character with an empty bubble. The children expressed their understanding that this figure could not or did not want to say anything about the topic: "Well, maybe she just doesn't want to say it, because maybe the others would laugh at her, that the others, that their parents simply are together and they aren't" (Ines, single-parent family). Overall, the interaction and cooperation phases were highly important in terms of contents and time, as elucidated by the large discussion-generating potential of the concept cartoons. [35]

3.3 Texts and images in discussion process

Text-based elements can be integrated during and after a concept cartoon discussion by letting the discussants put suggestions down in writing to fill in the empty bubble. As it is not necessary to verbalize what one thinks about the topic, but rather what the concept cartoon character with the empty bubble could think and say, additional depersonalized statements about the topic become possible. From a methodical perspective, this is another (text-based) option for children getting involved. [36]

In the SMiLE study, the children formulated their own or further possible statements for the empty speech or thought bubbles. To this end, preprinted empty bubbles were provided. Some of the children subsequently read out their bubble texts and put them up for discussion in the groups. Others did not comment on their wordings but gave us their written statements anonymously. The children frequently argued that Manu, the figure given an empty speech bubble in the presented concept cartoon, also did not have to say anything about the topic of "when parents separate"—perhaps she simply wanted to say nothing at all. In some of the bubbles, the children expressed that Manu's parents perhaps only separated temporarily: "When parents separate, it's also possible that they just do that for a couple of weeks" (Ronja, nuclear family). Some of the children phrased their texts in a subject-denoting form by giving Manu a voice: "When parents separate, do I have to decide?" (Rene, single-parent family) Open questions which could be asked by the children of separated parents were also put down in writing in the form of a bubble text for Manu: "How do the parents feel?" (Joshua, nuclear family) Text-based elements, and thus the possibility to avoid asking questions right beside the present children, also illustrated the participants' insecurity with regard to the topic of parental separation. Content-related questions were written into the preprinted bubbles, e.g., "When parents separate, do you see one parent less often?" (Alesa, nuclear family) Advice for parents was also formulated in the bubbles, such as how they should react after separating: "When parents separate, then a calm explanation is good for the child instead of screaming around" (Ines, single-parent family). [37]

In particular, the visual elements of the concept cartoons generated a multitude of narrations and discussions. The children argued in discussing the "When parents separate" cartoon that in this case, all family members still "liked one another" after the parents had separated: "You can see that, because almost everybody's holding hands" (Gustav, single-parent family). Observing the illustration led to both positive and negative associations: "The parents ought to have their arms differently when they're quarreling" (Ida, nuclear family). The children paid attention to and questioned every graphic detail of the concept cartoons. In the present case, the number of people in the center of the picture resulted in a need for discussion and further ideas about parental separation: "Because there are two parents and two kids in the picture, and when they separate, then the mother can have a child and the father can have a child" (Dino, nuclear family). [38]

The children addressed the concept cartoon characters from a situational, graphic and personal perspective: Situationally, they reacted to the circular arrangement of the figures, through which the participants were able to identify with the illustrated children: "I think, that's like, like we do it, now, in the group, and they're talking about it" (Ida, nuclear family). Graphically and personally, the concept cartoon characters' appearances and possible life stories were repeatedly addressed. Comprehensive biographies were thought up for the individual figures, e.g., for Tom and his dark skin: "I don't think Tom has a family. Maybe he's from [...] Syria or so and escaped" (Michael, nuclear family). Overall, the discussion of the visual elements and the possibility to participate by drawing up the bubble texts led to the childrens' contentful and amplifying contributions. [39]

3.4 Analysis and further development

In analyzing the concept cartoon discussions, we pursued the objective to capture and interpret the children's concepts, knowledge structures, and patterns of orientation.6) Although the analysis phase was the only one in the project not to be carried out with the children involved, the results were discussed with them. Apart from the concept cartoon discussions, the wealth of material comprised group discussions, qualitative interviews, and participant observations. Three techniques of analysis were applied to this material: The documentary method (BOHNSACK, 2014) was primarily employed to reconstruct the orientation patterns and thus work out the immanent contents and motives of what had been recounted. Furthermore, the entire material was analyzed by applying thematic coding (FLICK, 2011) to thematically capture communication contents. Following this, Grounded-Theory-based axial coding (CORBIN & STRAUSS, 2015 [1990]) was used in some places to interpret the arrangement, strategies, and basic conditions of the children's individual concepts. [40]

Apart from specific methods, we generally recommend a two-step evaluation procedure in analyzing concept cartoon discussions:

Separate content-related analyses of each concept cartoon by comprehensively analyzing all discussions about one cartoon: These analyses resulted in insights into communication processes and bodies of knowledge regarding a specific topic and individual statements made by the concept cartoon characters and/or notions regarding that topic. In the case of the "When parents separate" cartoon, for example, this cartoon-centered analysis revealed differences in conceiving parental separation and divorce from the children's perspectives. Some of them considered both to be equal while others identified substantial differences, outlining separation as temporary and divorce as final: "Separation isn't really losing completely and divorce is losing, and when you separate, you can see each other again, and I think when you divorce, you can't see each other again" (Nils, stepfamily).

Cross-theme and cross-case analyses of all concept cartoon discussions: These analyses allowed us to highlight the children's ideas concerning parental separation and divorce across the individual concept cartoon topics. Cross-theme analysis allowed us to identify and interpret concepts regarding children's voices in divorce proceedings, amongst other concepts. The participants debated the children's roles in the cartoon discussions, thus addressing the scope of possibilities to participate in the event of parental separation from their own perspectives: "Well, parents arrange those things, because kids don't have a say, not really" (Lena, nuclear family); "Children have a voice, but parents are the ones to decide" (Alesa, nuclear family). [41]

Following the stages of participatory preparation, application, and scientific analysis, the concept cartoons in the SMiLE study underwent further participatory development and were tested in various variants with the participating children in order to reflect the applicability of concept cartoon discussions in social research. This process comprised autonomous adaptations of the 20 concept cartoons the children had developed and the conception of new concept cartoons and illustrated stories that were self-determined in content-related and graphic terms. The participants in the small groups were given variations of the developed concept cartoons, e.g., illustrations including titles and characters, yet without bubble texts. The students were able to bring in their own ideas and perspectives without being influenced by depicted contents or formulations. Additional variations included cartoons without central illustrations, which the children were able to draw up themselves. Finally, cartoons that only included titles were presented to gather further ideas from the children. [42]

In terms of self-determined participation, some of the children expressed their wish during the research stays to realize their own concept cartoons without the adult researchers' involvement. Largely within the framework of the study, the small-group participants created cartoons considering family-related topics and divorce processes. Illustration 3 shows one of the children's concept cartoons with the title "Where should children live after divorce?."

Illustration 3: Concept cartoon of our participating children "Where should children live after divorce?"7) [43]

Apart from single images, the children also designed illustrated stories in the form of comics. Illustration 4 shows a segment from such a story.

Illustration 4: Segment of a comic "Quarreling goes on"8) [44]

Furthermore, the participatory character was emphasized when the children presented the concept cartoons they had developed on the occasion of a public closing event at the two research sites. The children expressed core messages regarding the research topics and their involvement resulted in materials for other children. These jointly developed practice-oriented materials (a flyer for children, teaching materials for teachers and children) are freely accessible at the project website. [45]

4. Conclusion: Concept Cartoons in Social Science Childhood Research

Visual elements to generate image-supported narratives, argumentations, and reasonings are increasingly put to use in qualitative social research (e.g., BARTER & RENOLD, 2000; BENDER, 2011; BLAISDELL et al., 2019; ESIN, 2017). It is surprising that concept cartoons as a technique at the interface between visual and text-based approaches have yet not been applied in social science (childhood) research. On account of the many potentials and advantages associated with this approach, it seems sensible and expedient to incorporate concept cartoon discussions into sociological childhood research as a qualitative, visual-narrative, and text-based method. Still, a reflective approach to the challenges of practicability remains necessary. [46]

To date, concept cartoons have been especially applied in the didactics of teaching. For the first time, they were further developed in the study presented here and made usable for participatory social science childhood research. Concept cartoons link to present knowledge, animate discussions, promote the discussants' willingness to reason, support in phrasing ideas on the topic, and bridge language barriers. They also make it possible to verbalize fictional characters' statements rather than one's own opinions, increase the thirst for knowledge and motivation among those involved, and reveal the diversity of notions regarding a defined topic (FENSKE et al., 2011; JAMAL et al., 2019; KEOGH & NAYLOR, 1999; NAYLOR & KEOGH, 2013, 2014 [2000]; WOOLMAN, 2019). The possibility to develop concept cartoons at a participatory level and the combination of verbal, visual, and text-based data in discussion groups are probably their most crucial advantage in methodical and methodological terms. Visual and text elements are closely connected and are discussed in groups, permanently accompanied by argumentations, reasonings, and identifications with other discussants' or the concept cartoon characters' statements. [47]

The visual elements of concept cartoons play a key role in this connection, beginning with the development of the characters themselves, who are to reflect great diversity, and the (semi-)circular arrangement of the figures, which reminds the children of the discussion they themselves are currently involved in. This also applies to the possibility to stimulate their comments with richly varied illustrations and the integration of a central image as a (further) statement on the topic under investigation. From a methodical perspective, empty speech and thought bubbles are also an advantage as they prompt children to argue in a depersonalized fashion. In discussing the cartoons, the children share their subjective orientational and experiential knowledge at various levels, which can be reconstructed in the analysis phase. [48]

Another advantage of concept cartoons is that research topics can be discussed apart from biographical experiences and that the researchers do not require information in advance about the extent to which the participants bring along certain knowledge or experiences. Particularly with such sensitive topics as parental separation and divorce, children's perspectives can thus be made available in research beyond narrations of one's own experiences. Regardless of their own family situations or levels of experience and knowledge, all children can cooperate in this way in the research and communicate their concepts. [49]

Other studies on the topic of parental separation focusing on children's perspectives (e.g., BIRNBAUM & SAINI, 2012; MARSCHALL, 2016; SMART, 2006; SMART, NEALE & WADE, 2001) have also advocated a methodical approach that facilitates the impartation of ideas and experiences, as is the case with concept cartoon discussions. As compared to the qualitative group discussions, interviews and participant observations carried out in this study, the concept cartoon discussions and the children's independently designed concept cartoons served to identify other, as yet unidentified, concepts. These concepts included the relevance of the right to a say from the children's perspectives. Unlike the mentioned studies on the topic of parental separation, concept cartoons allowed the children's depersonalized arguments and perspectives on the topic to be captured. [50]

In applying concept cartoon discussions, the possibilities of peer learning are of interest to childhood research: On the one hand, the children involved learn from one another in discussing and inquiring about (sensitive) topics in small groups. On the other hand, communicative exchanges unfold via the depicted characters which animate the children, on their own initiative and without request, to draft explanatory strategies for the figures' statements and to develop their life stories. In this connection, the children's ideas and concepts regarding the topic again become apparent. Communication dynamics become distinct within the group in the various phases of narration and discussion. Communication processes can be reconstructed and deconstructed and cross-case analyses be carried out. For this reason, no case reconstruction is possible with this method at the level of individual participants. [51]

Using concept cartoon discussions in participatory research makes it possible for quiet and shy children to become involved. In general, participatory social research with children is considered to be a challenge, as co-researchers' active involvement requires much flexibility in the research process. Each phase of research—problem definition, construction of the assessment instrument, assessment, analysis, and dissemination of insights—is to be observed separately and the meaning and possibilities of participation to be consistently negotiated. Applying the method facilitates various degrees of participation in the phases of topic definition, construction, assessment, and insight dissemination, and thus in joint research with children of various age groups. Even younger children with less developed speaking, reading, and writing skills can be empowered to collaborate in the research. The use of concept cartoon discussions as a social science research method proved to be an inspiring and motivating activity for children. By means of the many creative possibilities to communicate, the children involved also had a very good time with this research technique. Finally, their independently designed concept cartoons, or elements of those cartoons, can be drawn upon to present and disseminate research results. [52]

Applying concept cartoons as a social science research method, resource issues become a challenge, especially when the objective is also to develop them in studies. Apart from content-related knowledge concerning the research topic, methodical implementation also requires methodological knowledge, graphic competencies, and considerable time resources for the stepwise participatory processes of cyclical research. Moreover, flexibility during research is considered to be an essential premise. Aspects of research ethics, including parents' consent prior to contacting potentially participating children, as well as the necessary formal preconditions for cooperating with schools are to be comprehensively taken into consideration and to be planned and implemented in project management. At times, these challenges have let researchers reach their limits in everyday scientific life. [53]

In view of their many advantages, and in spite of the challenges, we argue the case for a more comprehensive use of concept cartoon discussions in social science (childhood) research. Their application and continuing development require further, targeted methodical research and differentiated methodological analyses in an attempt to support the advancement of concept cartoons into the realm of social science research with adults. [54]

1) All text passages from non-English texts are translated by us. <back>

2) We are grateful to Stuart NAYLOR and Millgate House Education for allowing us to reproduce this concept cartoon. <back>

3) The SMiLE study was financed by the Austrian Federal Ministry of Education, Science and Research Sparkling Science program. <back>

4) We own the copyright to the following images. <back>

5) All of the children's names are pseudonyms. The family forms in which the children were living at the time of the study are additionally stated. <back>

6) For several content-related results, see ZARTLER et al. (2020). <back>

7) Our translation of the children's concept cartoon with the title "Where should children live after divorce?": "Time is money" [in the center of the illustration]; "She should go to where she prefers and to whom she likes more" [figure to the right]; "They should decide whom they want to live with" [child with the base cap]; "They should split their time between their parents and live comfortably" [girl in the middle]; "They should spend a week with their mama and a week with their papa" [figure in the right corner]. <back>

8) Our translation of the part of children's comic: "Quarreling goes on ..."; woman at the left: "Why would you say that? The two will stay with me"; man standing at the middle: "Emir will stay with ME!"; Thought bubble next to the girl "Clueless"; bubble of both children "Do our parents still like us?" <back>

Akamca, Güzin Özyilmaz; Ellez, A. Murat & Hamurcu, Hülya (2009). Effects of computer aided concept cartoons on learning outcomes. Procedia – Social and Behavioral Science, 1(1), 296-301.

Alanen, Leena (2014). Theorizing childhood. Childhood, 21(1), 2-6.

Alderson, Pia & Morrow, Virgina (2011). The ethics of research with children and young People. London: Sage.

Aldridge, Jo (2017). Introduction to the issue. Promoting children's participation in research, policy and practice. Social Inclusion, 5(3), 89-92.

Anckar, Carsten (2008). On the applicability of the most similar systems design and the most different systems design in comparative research. International Journal of Social Research Methodology, 11(5), 389-401.

Arnstein, Sherry R. (1969). A ladder of citizen participation. JAPA – Journal of the American Institute of Planners, 35(4), 216-224.

Atkinson, Catherine (2019). Ethical complexities in participatory childhood research. Rethinking the "least adult role". Childhood, 26(2), 186-201.

Balim, Ali G.; Inel-Ekici, Didem & Özcan, Erkan (2016). Concept cartoons supported problem based learning method in middle school science classrooms. Journal of Education and Learning, 5(2), 272-284.

Balta, Nuri & Sarac, Hakan (2016). The effect of 7E learning cycle on learning in science teaching. A meta-analysis study. European Journal of Educational Research, 5(2), 61-72.

Barke, Hans-Dieter; Engida, Temechegn & Yitbarek, Sileshi (2009). Concept Cartoons. Diagnose, Korrektur und Prävention von Fehlvorstellzungen im Chemieunterricht. Praxis der Naturwissenschaften – Chemie in der Schule, 8(58), 44-49.

Barker, John & Weller, Susie (2003). Is it fun? Developing children centred research methods. International Journal of Sociology and Social Policy, 23(1/2), 33-58.

Barter, Christine & Renold, Emma (2000). "I wanna tell you a story". Exploring the application of vignettes in qualitative research with children and young people. International Journal of Social Research Methodology, 3(4), 307-323.

Behnke, Joachim; Baur, Nina & Behnke, Natalie (2006). Empirische Methoden der Politikwissenschaft. Vienna: UTB.

Bender, Saskia (2011). Empirische Zugriffe auf ästhetische Erfahrungen bei Kindern durch Materialtriangulation. In Jutta Ecarius & Ingrid Miethe (Eds.), Methodentriangulation in der qualitativen Bildungsforschung (pp.321-335). Opladen: Barbara Budrich.

Bergold, Jarg & Thomas, Stefan (2012). Partizipative Forschungsmethoden. Ein methodischer Ansatz in Bewegung. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung / Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 13(1), Art. 30, http://dx.doi.org/10.17169/fqs-13.1.1801 [Accessed: March 2, 2020].

Betz, Tanja; Gaiser, Wolfgang & Pluto, Liane (Eds.) (2010). Partizipation von Kindern und Jugendlichen. Forschungsergebnisse, Bewertungen, Handlungsmöglichkeiten. Schwalbach: Wochenschau Verlag.

Birisci, Salih; Metin, Mustafa & Karakas, Mehmet (2010). Pre-service elementary teacher's views on concept cartoons. A sample from Turkey. Middle-East Journal of Scientific Research, 5(2), 91-97.

Birnbaum, Rachel & Saini, Michael (2012). A scoping review of qualitative studies about children experiencing parental separation. Childhood, 20(2), 260-282.

Blaisdell, Caralyn; Arnott, Lorna; Wall, Kate & Robinson, Carol (2019). Look who's talking. Using creative, playful arts-based methods in research with young children. Journal of Early Childhood Research, 17(1), 14-31.

Bohnsack, Ralf (2014). Rekonstruktive Sozialforschung. Einführung in qualitative Methoden. Opladen: Barbara Budrich UTB.

Buchberger, Wolfgang; Eigler, Nikolaus & Kühberger, Christoph (2019). Mit Concept Cartoons historisches Denken anregen. Ein methodischer Zugang zum subjektorientierten historischen Lernen. Frankfurt/M.: Wochenschau Verlag.

Chin, Christine & Teou, Lay-Yen (2009). Using concept cartoons in formative assessment. Scaffolding students' argumentation. International Journal of Science Education, 31(10), 1307-1332.

Christensen, Pia & James, Alan (Eds.) (2017). Research with children. Perspectives and practices. London: Taylor & Francis.

Christensen, Pia & Prout, Alan (2002). Working with ethical symmetry in social research with children. Childhood, 9(4), 477-497.

Clark, Alison (2010). Young children as protagonists and the role of participatory, visual methods in engaging multiple perspectives. American Journal of Community Psychology, 26(1-2), 115-123.

Corbin, Juliet & Strauss, Anselm (2015 [1990]). Basics of qualitative research. Techniques and procedures for developing grounded theory (4th ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Dabell, John (2008). Using concept cartoons. Mathematics Teaching Incorporating Micromath, 209, 34-36.

Dörner, Olaf (2007). Comics als Gegenstand qualitativer Forschung. Zu analytischer Möglichkeiten der Dokumentarischen Methode am Beispiel der "Abrafaxe". In Barbara Friebertshäuser, Heide von Felden & Burkhard Schäffer (Eds.), Bild und Text. Methoden und Methodologie visueller Sozialforschung in der Erziehungswissenschaft (pp.179-196). Opladen: Barbara Budrich.

Ekici, Fatma; Ekici, Erhabn & Aydin, Fatih (2007). Utility of concept cartoons in diagnosing and overcoming misconceptions related to photosynthesis. International Journal of Environmental and Science Education, 2(4), 111-124.

Eldén, Sara (2013). Inviting the messy. Drawing methods and "children's voices". Childhood, 20(1), 66-81.

Ergler, Christina (2017). Beyond passive participation. From research on to research by children. In Ruth Evans, Luise Holt & Tracey Skelton (Eds.), Methodological approaches. Geographies of children and young people 2 (pp.97-115). Singapore: Springer.

Esin, Cigdem (2017). Telling stories in pictures. Constituting processual and relational narratives in research with young British Muslim women in East London. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung / Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 18(1), Art. 15, http://dx.doi.org/10.17169/fqs-18.1.2774 [Accessed: March 2, 2020].

Eßer, Florian & Sitter, Miriam (2018). Ethische Symmetrie in der partizipativen Forschung mit Kindern. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung / Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 19(3), Art. 21, http://dx.doi.org/10.17169/fqs-19.3.3120 [Accessed: March 2, 2020].

Fassetta, Giovanna (2016). Using photography in research with young migrants. Addressing questions of visibility, movement and personal spaces. Children's Geographies, 14(6), 1-15.

Fenske, Felix; Klee, Andreas & Lutter, Andreas (2011). Concept-Cartoons as a tool to evoke and analyze pupils' judgments in social science education. Journal of Social Science Education, 10(3), 46-52.

Flick, Uwe (2011). Qualitative Sozialforschung. Eine Einführung. Reinbek: Rowohlt.

Francis, Mark & Lorenzo, Ray (2002). Seven realms of children's participation. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 22(1-2), 157-159.

Gallacher, Lesley-Anne & Gallagher, Michael (2008). Methodological immaturity in childhood research? Thinking through "participatory methods". Childhood, 15(4), 499-516.

Gallagher, Michael (2008). "Power is not an evil". Rethinking power in participatory methods. Children's Geographies, 6(2), 137-150.

Gibson, Jennifer E. (2012). Interviews and focus groups with children. Methods that match children's developing competencies. Journal of Family Theory & Review, 4(2), 148-159.

Grant, Thomas (2017). Participatory research with children and young people. Using visual, creative, diagram, and written techniques. In Ruth Evans, Luise Holt & Tracey Skelton (Eds.), Methodological approaches. Geographies of children and young people 2 (pp.261-284). Singapore: Springer.

Groundwater-Smith, Susan; Dockett, Sue & Bottrell, Dorothy (2015). Participatory research with children and young people. Los Angeles, CA: Sage.

Grünewald, Dietrich (2000). Comics. Berlin: De Gruyter.

Guillemin, Marilys & Drew, Sarah (2010). Questions of process in participant-generated visual methodologies. Visual Studies, 25(2), 175-188.

Hafeneger, Benno (Ed.) (2005). Kinder- und Jugendpartizipation in Deutschland. Entwicklungsstand und Handlungsansätze. Opladen: Barbara Budrich.

Hart, Roger (1992). Children's participation. From tokenism to citizenship. Florence: UNICEF – United Nations Children's Fund.

Honig, Michael-Sebastian (2009). How is the child constituted in childhood studies?. In Jens Qvortrup, William A. Corsaro & Michael-Sebastian Honig (Eds.), The Palgrave handbook of childhood studies (pp.62-77). Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

Horgan, Deidre (2017). Child participatory research methods. Attempts to go "deeper". Childhood, 24(2), 245-259.

Horlock, Jo (2012). What will your students be talking about this summer? Talking sport and fitness using concept cartoons. School Science Review, 93(345), 49-54.

Hunleth, Jean (2011). Beyond on or with. Questioning power dynamics and knowledge production in "child-oriented" research methodology. Childhood, 18(1), 81-93.

Jamal, Siti N.B.; Ibrahim, No H.B & Surif, Johari B. (2019). Concept cartoon in problem-based learning. A systematic literature review analysis. Journal of Technology and Science Education, 9(1), 51-58.

James, Allison & James, Adrian (2012). Key concepts in childhood studies. London: Sage.

Jenkins, Nicholas; Bloor, Michael; Fischer, Jan; Berney, Lee & Neale, Joanne (2010). Putting it in context. The use of vignettes in qualitative interviewing. Qualitative Research, 10(2), 175-198.

Johnson, Ginger; Pfister, Anne & Vindrola-Padros, Cecilia (2012). Drawings, photos and performances. Using visual methods with children. Visual Anthropology Review, 28(2), 164-178.

Kabapinar, Filiz (2009). What makes concept cartoons more effective? Using research to inform practice. Education and Science, 34(154), 104-118.

Kaptan, Fitnat & Izgi, Ümit (2014). The effect of use concept cartoons attitudes of first grade elementary students towards science and technology course. Procedia – Social and Behavioral Sciences, 116, 2307-2311.

Keogh, Brenda & Naylor, Stuart (1997). Starting points of science. Sandbach: Millgate House.

Keogh, Brenda & Naylor, Stuart (1999). Concept cartoons, teaching and learning in science. An evaluation. International Journal of Science Education, 21(4), 431-446.

Kogler, Raphaela (2018). Bilder und Narrationen zu Räumen. Die Zeichnung als visueller Zugang zur Erforschung sozialräumlicher Wirklichkeiten. In Jeannine Wintzer (Ed.), Sozialraum erforschen. Qualitative Methoden in der Geographie (pp.261-277). Berlin: Springer.

Kovalainen, Minna & Kumpulainen, Kristiina (2005). The discursive practice of participation in an elementary classroom community. Instructional Science, 33(2), 213-250.

Kühberger, Christoph (2017). Concept Cartoons für den Politik- und Geschichtsunterricht. Ein subjektorientierter Zugang zur Diagnostik und Methodik. Wahlen und wählen – Informationen zur Politischen Bildung, 41, 23-29, http://www.politischebildung.com/wp-content/uploads/izpb41_kuehberger.pdf [Accessed: February 11, 2021].

Lange, Andreas & Mierendorff, Johanna (2009). Methoden der Kindheitsforschung. Überlegungen zur kindheitssoziologischen Perspektive. In Michael-Sebastian Honig (Ed.), Ordnungen der Kindheit. Problemstellungen und Perspektiven der Kindheitsforschung (pp.183-210). Weinheim: Juventa.

Leavy, Patricia (2019). Introduction to arts-based research. In Patricia Leavy (Ed.), Handbook of arts-based research (pp.3-21). New York, NY: The Guilford Press.

Legewie, Heiner (1987). Interpretation und Validierung biographischer Interviews. In Gerd Jüttemann & Hans Thomae (Eds.), Biographie und Psychologie (pp.138-150). Berlin: Springer.

Lembens, Anja & Steininger, Rosina (2012). Verstehendes Lernen durch Concept Cartoons. In Sascha Bernholt (Ed.), Konzepte fachdidaktischer Strukturierung für den Unterricht (pp.352-354). Berlin: LIT-Verlag.

Mand, Kanwal (2012). Giving children a "voice". Arts-based participatory research activities and representation. International Journal of Social Research Methodology, 15(2), 149-160.

Mannay, Dawn (2016). Visual, narrative and creative research methods. Application, reflection and ethics. London: Routledge.

Marschall, Anja (2016). Children's perspectives on post-divorce family life. Continuity and change. In Shannon Grant (Ed.), Divorce. Risk factors, patterns and impact on children's wellbeing (pp.117-130). New York: NY: Nova Science Publishers.

Mason, Jan & Watson, Elizabeth (2014). Researching children. Research in, with, and by children. In Asher Ben-Arieh, Ferran Casa, Ivar Frønes & Jill Korbin (Eds.), Handbook of child well-being. Theories, methods and policies in global perspective (pp.2757-2796). Dordrecht: Springer.

Mey, Günter & Schwentesius, Anja (2019). Methoden der qualitativen Kindheitsforschung. In Florian Hartnack (Ed.), Qualitative Forschung mit Kindern. Herausforderungen, Methoden und Konzepte (pp.3-47). Wiesbaden: Springer VS.

Meyer, Frank (2018). Yes we can(?) Kommunikative Validierung in der qualitativen Forschung. In Frank Meyer, Judith Miggelbrink & Kristine Beurskens (Eds.), Ins Feld und zurück – Praktische Probleme qualitativer Forschung in der Sozialgeographie (pp.163-168). Berlin: Springer.

Min-Jin, Lin & Ching-Dar, Lin (2011). Guiding undergraduate students to collaborate in the design and development of concept cartoon with the support of TINS. In Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers (Ed.), IEEE 3rd International Conference on Communication Software and Networks (pp.240-244). Xi'an: Piscataway.