Volume 22, No. 2, Art. 13 – May 2021

Re-Figuration of Spaces as Long-Term Social Change: The Methodological Potential of Comparative Historical Sociology for Cross-Cultural Comparison

Jannis Hergesell

Abstract: Analyzing social change from a historical perspective is one of the longest established strategies of sociological comparison. Numerous classic sociologists have examined cross-cultural (long-term) social change with a historical-comparative methodology in an effort to understand the differences and similarities of transformation processes in the present by reconstructing their past. As such, there are comprehensive historical-sociological preliminary works, which are intended as a means of analyzing the long-term and large-scale social change that is currently leading to a fundamental, worldwide restructuring of spatial orders, referred to as the re-figuration of spaces. Nevertheless, no one has applied the comparative methodology of historical sociology to the empirical analysis of the re-figuration of spaces so far. Instead, research on the re-figuration is currently restricted to research designs focused on the present. Therefore, I propose considering the methodological potential of historical-comparative methodology for research on the re-figuration of spaces. I start by discussing existing preliminary historical-sociological work on comparison strategies for analyzing cross-cultural, large-scale social change. Then, I will show how the re-figuration of spaces can be understood as long-term social change. On this basis, I will outline a universally comparative, causal-analytic, historical-sociological methodology of research on the re-figuration of spaces.

Key words: figurational sociology; historical sociology, historical-comparative social research, cross-cultural comparison; sociology of space; spatial analysis; re-figuration of spaces

Table of Contents

1. The Re-Figuration of Spaces From a Historical-Sociological Perspective

2. Methodological Approaches in Historical-Comparative Sociology

2.1 Levels of analysis in historical-comparative research

2.2 Types of comparison in historical-comparative research

2.3 Theoretical-methodological fields in historical-comparative research

3. The Causal–Analytic School's Procedure for Constructing Comparative Dimensions, Structural Characteristics and the Re-Figuration of Spaces

4. Re-Figuration of Spaces as Long-Term Social Change

5. Structural Characteristics of the Re-Figuration of Spaces

5.1 Polycontexturalization

5.2 Mediatization

5.3 Tanslocalization

6. An Outline for a Historical-Comparative Methodological Approach to Analyzing the Re-Figuration of Spaces

6.1 Step 1: Initial case studies in the present

6.2 Step 2: Identification and conceptualization of structural characteristics

6.3 Step 3: Periodization and reconstruction of long-term social structural changes

6.4 Step 4: Intra-case, inter-case comparison and theory formation

7. Summary and Conclusion

1. The Re-Figuration of Spaces From a Historical-Sociological Perspective

Structural-spatial transformation processes usually unfold over an extended period of time. Therefore, the causes of current spatial phenomena often originate in bygone times. This so-called longue durée [long-term social processes] (BRAUDEL, 1976) can range from several centuries (or even millennia) to a couple of decades. For example, BRAUDEL (1990) reconstructed the beginning and course of the economic and social history of the Mediterranean with the claim of a histoire totale [all-encompassing history]. He illustrated that the ancient origins of mutual effects between geographical framework conditions and social structures have significant potential for explaining developments in the spatial structuring of the Mediterranean Sea's geographical space that take place at a much later stage. ELIAS (1989, 1997 [1939]) also demonstrated the analytical benefit of a historical perspective in the sense of longue durée on spatial transformation processes, for example, by reconstructing the constitution of nation states in the modern era. The developments of this long-gone era still shape spatial nation state structures today. Without the reconstruction of the nation-building process that began at that historical time, many cultural and political characteristics of modern nations, such as military conflicts, economic relations as well as the European unification, could not be explained causally. [1]

Therefore, spatial researchers must take into account the historical trajectories of today's spatial transformation processes and their unfolding over time both theoretically and methodologically, especially when examining long-term, fundamental transformation processes (BAUR, 2015). This applies in particular to research on the re-figuration of spaces (KNOBLAUCH, 2017; KNOBLAUCH & LÖW, 2017; LÖW, 2018). Scholars engaged in the analysis of re-figuration research assume a current, cross-cultural transformation of spatial dynamics and analyze this transformation process by comparing different contemporary re-figuration phenomena. Nevertheless, until now, researchers have developed their comparative dimensions, which are necessary for their research agenda, by using theoretical and methodological approaches focusing mainly on the present day. Researchers on the re-figuration of spaces have developed a theoretical-conceptual framework for understanding spatial change in the contemporary world. That is why re-figuration researchers have also focused their methodological-methodical approaches on the present, such as ethnographies or interviews. Thus, they have so far excluded process-generated data that provide information about the (more distant) past, thus neglecting existing approaches in historical-comparative research. [2]

Although several scholars have dealt with the methodological implications of the entanglement of time (process) and space (BECKER, 2019; LAUX, HENKEL & ANICKER, 2017; SCHILLING & KÖNIG, 2020), their approaches have referred almost exclusively to spatial-temporal short-term processes (at the analytical micro-level), for example in ethnographic (CHRISTMANN, 2014; SCHELLER, 2020) or discourse analytical (HAMANN & SUCKERT, 2018; HANNKEN-ILLJES, 2007) studies—the longue durée and macro-level phenomena were mostly ignored. Similarly, methodological topics relevant to time-sensitive or processual sociology, such as the interaction of time, space, and materiality (SØRENSEN, 2007), have recently been addressed, but not in regard to historical-comparative analyses of long-term processes (for an exception, see FREHSE, 2017, 2020). For historical sociologists, this is irritating because various approaches in socio-historical (and especially in historical-comparative) research share the core thesis of re-figuration that "culture(s)" or "space(s)" are not given entities, but rather that an understanding of apparently clearly demarcated spaces is historically grown and depends on time-specific interpretations (KOSELLECK, 2018 [2003]; SPOHN, 1998). In this context, the question arises as to which established social structures are transformed during a re-figuration. The specifics of the re-figuration process, as the most significant social change at the moment, can only be comprehended by means of historical comparison with previously dominant forms of large-scale social change, such as rationalization or modernization. Additionally, the term re-figuration, which is derived from figurational and process sociological theory, implies a privileged consideration of the temporal dimensions of spatial transformation processes. Furthermore, KNOBLAUCH and LÖW (2017) noted that social science researchers have increasingly taken an interest in the current massive transformation of spatial orders, referred to as re-figuration (of spaces), although this has already been going on for decades (or longer). These two basic assumptions, the historical contingency of perception of cultures and the currently accelerating but historically evolved social change of cultural spaces, obviously imply a socio-historical perspective: the re-figuration of spaces can only be causally grasped by analyzing and comparing the regional historical roots of the current global transformation process. This understanding is a fundamental prerequisite for providing comparative dimensions for an empirically grounded, cross-cultural comparison of the ongoing process of re-figuration. [3]

A socio-historical perspective in the research on re-figuration of spaces is not only conceptually reasonable, but numerous preliminary works can be used as an orientation towards time-sensitive research on re-figuration, since the consideration of temporality (or historicity) in the analysis of cross-cultural social change is not new. Quite the contrary, many classic sociologists have raised cultural, space-related questions based on historical-comparative methodology (KALBERG, 1994; TILLY, 1984). WEBER (1922 [1920]), as the most prominent example, worked out the specifics of occidental rationalism in contrast to other forms of (oriental) rationalities. His comparative studies of the major world religions explained their historically grown differences by reconstructing their sociogenesis. In this way, WEBER (2002a [1904], p.103) presented in detail the causes of their geschichtliches So-und-nicht-anders-Gewordensein [being-historically-so-and-not-otherwise]. As the term re-figuration suggests, the historical-sociological work of ELIAS can be used to provide methodological starting points for the development of comparative dimensions for research on the re-figuration of spaces. ELIAS (1977 [1939]) understood space and time not only as inseparably interwoven, but also explicitly used a historical perspective to explain contemporary, space-related phenomena. For example, he reconstructed historical developments in France and Germany to show the contemporary differences between the French (and English) understanding of civilization and its German counterpart culture. The list of classic sociologists who have used comparative methodologies goes on. [4]

The reluctance to use the potential of historical-comparative methodological for analyzing re-figuration can be traced back to several causes. A general reason could be the neo-liberal orientation of the modern university, in which "money flows to present-centred (or 'hodiecentric') research, which politicians, policy-makers and administrators believe to be useful [...] a belief in which a large proportion of mainstream sociologists find it advantageous to share" (LAW & MENNELL, 2017, p.1). LAW and MENNELL even came to the following conclusion: "In its origins, sociology was comparative-historical sociology" (ibid.). However, they added immediately afterward: "It no longer is": a diagnosis that can be confirmed in the currently ongoing sociological occupation with the re-figuration of spaces. This is a long-standing predominant trend that ELIAS (2006 [1983]) criticized as a retreat of sociologists to the present day. [5]

A practical reason behind the disregard for historical-sociological methodology in social science spatial research is certainly also the fact that both the classics (BAUR, ERNST, HERGESELL & NORKUS, 2019) and many of the more recent historical-sociological studies (MAHONEY, 2004) have rarely explicitly addressed their methodological (and methodical) approaches. There is no systematic process for how to develop (historical-)comparative dimensions for the purpose of cultural comparison. This makes it more difficult to use the underlying methodological work of the historical-sociological classics for the operationalization of contemporary (space-related) research questions. For this reason, the studies of historical-comparative researchers often remain invisible to other disciplines involved in space-related research. In addition to these disciplinary boundaries, the circulation of the state of historical-comparative research is often tied to language communities, in which members perceive each other only to a minimal extent leading to a limited spread of methodological approaches. [6]

In this article, I will argue that research on large-scale, long-term processes, such as the ongoing re-figuration of spaces, needs to be cross-cultural and historical-comparative in order to empirically examine and theoretically elaborate the thesis of a worldwide, fundamental transformation of social structures. Especially if the state of research is not very far advanced, it is necessary to construct dimensions of comparison to generate cross-case, generalizable findings. This is a core competence of historical sociologists, which WEBER called ursächlich erklären [causal explanation] (2002b [1920], p.653) and ELIAS denoted as "the progressive discovery of change-immanent structures and regularities, of the order of changes in the sequence of time itself" (2007 [1984], p.105). The historical-sociological methodology that both scholars used for their cross-cultural comparisons lends itself to the research on the re-figuration of spaces. Only the historical-comparative perspective enables one to identify what is distinctive and specific with regard to the re-figuration of spaces and what distinguishes it from previous fundamental processes of transformation. Comparative-historical sociology offers a broad repertoire of methodological approaches, which—depending on the empirical and theoretical research interest—allow for a systematic cross-cultural (and cross-case) comparison of re-figuration phenomena. Additionally, a historical-sociological perspective on the reordering of spatial structures represents a further advantage over the previous, merely present-day-focused research. Through the historical reconstruction of re-figuration phenomena, researchers can not only descriptively analyze differences and similarities between contemporary re-figuration phenomena, but they can also comprehensively understand their historical development and course. Thus, the previously unused methodology of historical sociology can advance the state of research on the re-figuration of spaces in two respects:

In addition to a broad methodological repertoire of comparative approaches for the purpose of present-day analysis, re-figuration researchers can apply the genuine interest of historical sociologists in uncovering patterns in the sociogenesis of transformation processes to cross-cultural comparison.

Moreover, they can grasp the causal relationships between historical and contemporary developments in the process. [7]

Therefore, I will discuss the unused potential of historical-comparative methodology for cross-cultural, space-related research (Section 2). In particular, I aim to harness historical-comparative approaches for conceptualizing comparative dimensions, which scholars can use in the research agenda on the re-figuration of spaces. For this purpose, I will first examine various historical-comparative schools concerning their potential to capture long-term (cultural) change, to theorize transformation processes through comparison, and to answer current research questions by reconstructing the past. In the next step towards a historical-comparative approach to research on the re-figuration of spaces, I will specifically discuss the eligibility of historical-sociological comparative approaches for the analysis of large-scale, long-term social change and the application of Struktureigentümlichkeiten [structural characteristic(s)] (ELIAS, 1978 [1970], p.131) for conceptualizing comparative dimensions (Section 3). I will then show how the re-figuration of spaces can be understood as long-term social change in the sense of historical sociology (Section 4), driven by its three central structural characteristics: polycontexturalization, mediatization, and translocalization (KNOBLAUCH & LÖW 2017) (Section 5). Subsequently, I will propose an outline of a historical-comparative methodological approach for cross-cultural research on the re-figuration of spaces consisting of consecutive steps (Section 6):

an empirically grounded analysis of structural characteristics in the present to conceptualize comparative dimensions;

the application of these dimensions in a historical reconstruction to achieve a causal understanding of re-figuration phenomena;

the comparison of different periods of individual re-figuration phenomena (intra-comparison) and between cross-cultural re-figuration phenomena (inter-comparison). [8]

2. Methodological Approaches in Historical-Comparative Sociology

In the long tradition of historical-comparative sociology, a wide range of analytical levels and methodological approaches can be found. The spectrum encompasses both the more in-depth analysis of individual historical processes, which is typical for historiographical studies and a genuine sociological interest in uncovering structures and social dynamics for the purpose of generalization (BEST, 2008; SCHÜTZEICHEL, 2004). Therefore, with the following explanations, I do not aim to provide a comprehensive overview of the state of research on historical-comparative sociology, but rather to discuss which preliminary historical-comparative works are appropriate for generating comparative dimensions for cross-cultural comparison based on previous systematizations. [9]

2.1 Levels of analysis in historical-comparative research

Researchers on the re-figuration of spaces have described a global and long-term process of change. Hence, their methodological approach requires, as TILLY put it, systematic access to "big structures and large processes" (1984, p.11). A commonality of such approaches in comparative socio-historical research is the following basic assumption:

"We must look at [processes] comparatively over substantial blocks of space and time, in order to see whence we have come, where we are going, and what real alternatives to our present condition exist. Systematic comparison of structures and processes will not only place our own situation in perspective, but also help with the identification of causes and effects" (ibid.). [10]

TILLY (pp.61-65) distinguished four levels of analysis in his systematization of historical-comparative research methodologies. These different approaches are respectively accompanied by different procedures generating comparative dimensions:

1. The world-historical level, in which specific characteristics of an era are classified in the history of mankind, such as the development of epoch-specific modes of production (e.g., industrialization or the accumulation of capital) or typical forms of socialization such as urbanization, nation-building or secularization. At this level of analysis, the aim is to generate general statements about these main structures by comparing different world systems. TILLY described this approach as

"the hugest comparison of human affairs" and accordingly adds: "Personally, my eyes falter and my legs shake on this great plain. […] I don't believe, in any case, that we have established any well-documented and valuable general proposition at the word-historical scale" (p.63).

2. The world-systemic level, in which the essential and dominant structures of a social unit are examined at a global level:

"Here large-scale processes of subordination, production, and distribution attract our attention. Relevant comparisons establish similarities and differences among networks of coercion and among networks of exchange, on the one hand, and among processes of subordination, production, and distribution, on the other" (ibid.).

Even at this level of analysis, generalizations remain controversial and empirically difficult to confirm.

3. The macrohistorical level, in which particular big structures and large processes, as well as their different characteristics, are taken into consideration: This includes analysis units such as states, regional dominant modes of production or local organizations and associations such as companies, armies, etc.

"At this level, such large processes as proletarianization, urbanization, capital accumulation, statemaking, and bureaucratization lend themselves to effective analyses. Comparisons, then, track down uniformities and variations among these units, these processes, and combinations of the two" (pp.63-64).

4. The microhistorical level, in which the role of particular individuals and groups within these processes are analyzed as well as their everyday experiences and actions, which are related to the large-scale processes. At this level of analysis,

"[t]he necessary comparisons among relationships and their transformations are no longer huge, but they gain coherence with attachment to relatively big structures and large processes: the relationships between particular capitalists and particular workers reveal their pattern in the context of wider processes of proletarianization and capital concentration" (p.64). [11]

Within TILLY's systematization of approaches to historical-comparative research, the macrohistorical level of analysis is the most appropriate for research on the re-figuration of spaces. This is because although the re-figuration of spaces is a global and comprehensive transformation process, it is not empirically approachable in the sense of the world-systemic level, meaning the isolated analysis of a single unit, but rather it has to be initially subjected to a separate analysis of various re-figuration phenomena (or units). By comparing these various re-figuration phenomena, or rather by synthesizing the results of their analyses, it becomes possible to understand re-figuration as a coherent transformation of large processes and big structures. The macrohistorical level of analysis described by TILLY makes it possible to apply an inductive and empirically driven re-figuration research (see BENDASSOLLI, 2013, concerning inductive theory formation), in which researchers address the most diverse phenomena and relate them to each other using a comparative research program. Using the macrohistorical level approach, researchers can thus capture both the individual characteristics of individual re-figuration phenomena (units in TILLY's words) and the superordinate structures of spatial change in such comprehensive transformation processes, as represented by the current, worldwide and comprehensive transformation process of spatial order. [12]

2.2 Types of comparison in historical-comparative research

SPOHN (1998) noted that within historical-comparative research, these different levels of analysis are simultaneously accompanied by fundamentally different orientations of disciplinary methodological research interests: During historiographical comparisons, researchers try to stick closely to the analyzed sources and to achieve as much contextual depth as possible, whereby the number of dimensions of comparison and compared cases (or units) must remain relatively small. In contrast, researchers engaged in historical-sociological comparisons tend to set the depth of context aside, favoring generalization and striving primarily for a systematic and theory-based comparison of cases and dimensions. SPOHN delved into the systematization proposed by TILLY (1984) (Figure 1) and emphasized the number of cases analyzed in conjunction with the number of dimensions of comparison. TILLY named four extreme poles in his systematization of the level of analyses (see also BÜHL, 2003):

The individualized comparison (one comparison dimension for at least two cases) is designed "to contrast specific instances of a given phenomenon as a means of grasping the peculiarities of each case" (TILLY, 1984, p.82). TILLY cited as an example a study by BENDIX (1978) in which he compared political developments in Britain and Germany to find out why British workers were much more involved in national political decisions than German workers.

The encompassing comparison (recording all constitutive elements within a case) "places different instances at various locations within the same system, on the way to explaining their characteristics as a function of their varying relationships to the system as a whole" (TILLY, 1984, p.83). TILLY cited WALLERSTEIN's (for example 1974) research on world system analysis as the baseline for such a comparison strategy.

The universalizing comparison (at least one comparison dimension in as many cases as possible) "aims to establish that every instance of a phenomenon follows exactly the same rule" (TILLY 1984, p.82). TILLY suggested as an example of this approach the efforts to formulate a natural history of economic growth. In such a case, it is necessary to formulate assumed necessary and sufficient conditions for economic growth, which would then have to be found universally in every investigated case.

The variation-oriented comparison (as many dimensions of comparison as possible with as many cases as possible) "is supposed to establish a principle of variation in the character or intensity of a phenomenon by examining systematic differences among instances" (ibid.). As an example, TILLY cited a study by PAIGE (1975) in which he examined the various effects that result from variations between "different sorts of rural political actions" (TILLY, 1984, p.82) and the type of income of workers and the upper class as well as government repressions.

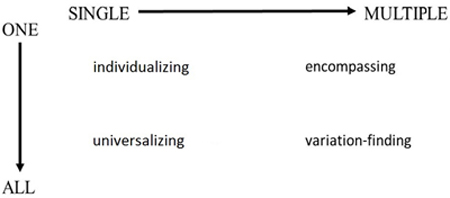

Figure 1: Systematization of historical-comparative methodological approaches (TILLY, 1984, p.81, my modification) [13]

Universalizing comparisons are most suitable for building conclusive comparative dimensions for empirical analyses of the re-figuration process. Only with this kind of comparison is it possible for researchers to examine whether the re-figuration is actually a global transformation process that affects all spheres of sociality: "The purpose of the universalizing comparison is to prove that the same laws can be found in all cases" (BÜHL, 2003, p.87)1). [14]

2.3 Theoretical-methodological fields in historical-comparative research

As already emphasized, the decision for a level of analysis is always closely linked with the choice of a (social) theoretical perspective (SKOCPOL & SOMERS, 1980; VOGELPOHL, 2013). Therefore, in addition to the systematization of conceivable dimensions of comparison, the underlying theoretical decisions must also be taken into account when choosing a specific historical-oriented methodological approach for research on the re-figuration of spaces. KALBERG (1994, pp.3-9) formulated such systematizations of historical-comparative schools, providing further orientation about which historical-comparative methodology is suitable for the analysis of the re-figuration of spaces. KALBERG categorized the historical-comparative sociology into three (competing) theoretical-methodological fields:

World system theory emerged in the 1970s, mainly from the works of BERGSEN (1983), GOLDFRANK (1979), ROBINSON (1981), and WALLERSTEIN (1974). Researchers who advocate this approach assume the existence of a world economy and explain historical processes using variables of a world system model. For example, factors such as "urbanization, capital accumulation, and political stability" can explain the developments of geographical regions "in terms of their location and functional relationship to the single and cohesive international marketplace" (KALBERG, 1994, p.4). Thus, the basic assumption of the world system theory is that the relations of a region (or space) to a world system allows for statements about their respective socio-cultural development. Accordingly, the key to understanding individual contextual spaces is the formulation of "laws of the world system" (p.5), which serve as a reference and explanation for the characteristic development of individual cultures. The criticism of this approach is, not surprisingly, that here a theoretical model is applied to a wide variety of phenomena, and thus it is not possible to grasp the concrete characteristics of an individual case (or rather culture). In this way, the "[u]niqueness, historical circumstances, and well-defined processes" (ibid.) are neglected, contextual-specific phenomena are disregarded. KALBERG divided the critics of the world system theory into two groups:

Representatives of the interpretative-historical approach place the historical development of an individual case and its respective specific manifestations at the center of their research interest. They aim for an empirically grounded theory formation oriented towards individual cases (KALBERG, 1994). Therefore, by comparing individual cases with one another, their intention is not to achieve generalizability that extends beyond the individual case. KALBERG cited the work of BENDIX (1976) and BENDIX and BERGER (1970) and called their "method of 'contrasting concepts'” (KALBERG, 1994, p. 5) as typical for this approach. The classification and contextualization of the individual case's historical development are thus carried out by comparison with other cases examined in detail. KALBERG considered interpretative approaches to be less suitable for testing hypotheses or generating theories and more appropriate for carrying out the "accurate construction of concepts" (1994, p.5) when reconstructing individual cases. According to his argumentation, the analysis of causal relationships refers only to the historical development within the investigated case and must be made on the basis of the "historical detail and chronology of events provided rather than by reference" (p.6) to a superordinate theoretical model.

Scholars of the causal-analytical approach share the criticism of the world system theory, but in contrast to the interpretative-historical approach, they aim to reveal general causal relations. The goal of causal-analytical historical-comparative researchers is the "construction of explanatory theories" (p.7), but not in the sense of universally causal laws. The postulated causal mechanisms have always to be carried out based on a detailed investigation of individual empirical cases—theory formation in the causal-analytical school is thus explicitly empirically grounded.

"Moreover, and again unlike adherents of the interpretative historical approach, their construction of causal arguments is guided by explicit research designs that aim to demarcate sources of variation and to produce valid inferences despite small number of cases" (ibid.). [15]

In this way, a controlled comparison is possible, in which researchers identify (possible) causes of a certain historical process by comparing it with other processes, thus allowing them to construct overarching theories. KALBERG cited the work of MOORE (1969) as a typical example of causal-analytical, historical-comparative research. MOORE examined the emergence of democracy, fascism, and communism by comparing different developments in participation in political decision-making processes in response to changes in agricultural modes of production across eight nation states. First, cause-effect relationships within the individual cases are reconstructed in detail and then compared with each other. Thus, by comparing the different historical lines of development, general causes can be identified and theoretical generalization can exceed the individual case. Another example cited in this approach is SKOCPOL (1979), who compared successful and failed revolutions in France, China, and Russia. In this way, she worked out the conditions for successful revolutions by first reconstructing and subsequently comparing individual, relevant historical developments, such as crises in the relationship between the state and the agricultural economy. This approach can be used to identify necessary and sufficient conditions for social revolutions (KALBERG, 1994). [16]

In KALBERG's systematization, the difference between the interpretative-historical and causal-analytical school consists primarily of the fact that researchers of the interpretative-historical approaches work out causality by reconstructing a detailed chronicle of a certain case. Thus, the scope of their statements on cause-and-effect mechanisms is always limited to one individual case. In contrast, the researchers of the causal-analytical school aim to formulate a theory at a higher aggregation level, whereby a detailed analysis of individual cases is only possible to a limited extent. [17]

Concerning the characteristics of the different historical-sociological schools identified by KALBERG, the perspective of the causal-analytic school is particularly apt for research on the re-figuration of spaces: in contrast to world system theory, researchers on the re-figuration of spaces cannot refer to an elaborated theory. Therefore, the deductive or hypothesis testing approach of the world system analysis is not adequate. Additionally, the perspective of researchers of interpretative-historical approaches, which focus on individual cases, is not a preferable option because it does not provide a methodological basis for generalization of patterns and mechanisms beyond single cases. However, the perspective of causal-analytical school is ideally suited for empirically grounded theory formation, which is also the aim of the research agenda of researchers on the re-figuration of spaces. This does not mean that research pursued in this way is solely confined to the analysis of causalities in historical developments. Nevertheless, the causal-analytical approach is particularly suitable since it enables researchers to perform systematic generalization beyond the individual case through the identification of cause-and-effect relationships. Therefore, the methodology of causal-analytically oriented historical sociology can be used as a tool to develop historically derived, substantial comparative dimensions for cross-cultural research on the re-figuration of spaces. [18]

To sum up the discussion so far, historical-comparative sociologists have developed various theoretical-methodical approaches to conceptualize comparative dimensions through historical reconstructions for the purpose of cross-cultural comparison. The approaches most suited to analyze the re-figuration of spaces are macro-historical approaches aimed at universal comparison and with a causal-analytical stance. Before I can use the previous explanations for a proposal towards a universally comparative, historical-causal oriented methodology of re-figuration, it is first necessary to discuss the concrete procedure employed by causal-analytic historical sociologists to construct comparative dimensions: the identification and reconstruction of structural characteristic. [19]

3. The Causal–Analytic School's Procedure for Constructing Comparative Dimensions, Structural Characteristics and the Re-Figuration of Spaces

For causal-analytical historical sociologists, the guiding methodological principle is that causes and courses of social change can be investigated by identifying and reconstructing structural characteristics (ELIAS, 1978 [1970], p.131). The underlying assumption of this concept is grasping current social structures by understanding their sociogenesis (e.g., ELIAS, 1997 [1939]). Researchers can use the analysis and reconstruction of structural characteristics to "direct the effort of cognition at the progressive discovery of change-immanent structures and regularities, of the order of changes in the sequence of time itself" (ELIAS, 2007 [1984], p.105). SCHWIETRING summarized this approach as the prerequisite for "explaining the existence of a fact through its history, thus interpreting that fact as part of a process that has led from the past to the present and has the future as an open horizon in front of it" (2015, p.151; see also KOSELLECK, 1989). [20]

Causal-analytical historical sociologists aim to understand the underlying order and structure of fundamental transformation processes that have a decisive influence on current society.

"From the viewpoint of the earlier figuration [or process], the latter is—in most if not in all cases—only one of several possibilities for change. From the viewpoint of the later figuration, the earlier one is usually a necessary condition for the formation of the later" (ELIAS, 1978 [1970], p.160). [21]

It is precisely this kind of large-scale, long-term social change (or transformation process) that causal-analytical historical sociologists capture through the analysis of structural characteristics. There are various terms for "structural characteristic[s]" (p.131) in the socio-historical state of research, for instance: process laws, path dependencies, trajectories, process patterns (also social patterns or driving forces) (AMINZADE, 1992; BAUR, 2005; BEST, 2008; BÜHL, 2003; CLEMENS, 2007; HERGESELL, 2019; KAVEN, 2015; SCHÜTZEICHEL, 2015; SOUZA LEÃO, 2013). All these concepts have in common that, methodologically speaking, they represent concepts with which long-term, cause-and-effect relationships and patterns in social change can be identified. In short, structural characteristics run like a thread through a process's historical development—analyzing them serves as a tool for understanding current events in the present through the reconstruction of the past (see also SCHÜTZEICHEL, 2004). [22]

WEBER represents an archetype of this methodological approach with his diagnosis of rationalization, driven by the spread of zweckrationales Handeln [purposive-rational action] (WEBER, 2002b [1920], pp.675) and legale [legal] respectively bürokratische Herrschaft [bureaucratic domination] (WEBER, 2002c [1922], p.717). Another prominent example is ELIAS's (1977 [1939]; 1997 [1939]) work "Über den Prozess der Zivilisation" [On the Process of Civilization]. ELIAS identified and reconstructed affect control, shifting of power balances, and increasing interdependencies as the driving structural characteristics behind Western society. Both WEBER and ELIAS determined these respective structural characteristics empirically. The validity of their concepts can be seen based on the fact that their identified and reconstructed structural characteristics manifested (to a greater or lesser extent) in almost all spheres of life in the cultural spaces examined. [23]

Thus, the concept of structural characteristics is a conducive methodological tool for cross-cultural comparisons, such as research on the re-figuration of spaces, for two reasons:

The understanding of the re-figuration of spaces is genuinely based on an Eliasian understanding of society as a constantly changing mesh of relationships (figurations) (ELIAS, 1978 [1970]), which can only be analyzed and understood by identifying its structural characteristics.

The methodological approach of identifying and reconstructing structural characteristics is designed for comparing similarities and differences in the course of social processes. Thus, it is a tool for constructing comparative dimensions for cross-cultural comparison. [24]

The added value of such an approach to the current research on the re-figuration of spaces is to understand re-figuration processes, consisting of their structural characteristics, as the specific and dominant form of social change for the present time by reconstructing and subsequently comparing their historical development. For the diagnosis of the re-figuration of spaces, such empirically grounded proof is still missing. In the following sections, I will discuss how historical-comparative methodology can contribute to such a further theoretical conceptualization of re-figuration. In this context, one needs to keep in mind that, unlike WEBER and ELIAS, the pursued explanatory power of research on the re-figuration of spaces is global and therefore, very ambitious. [25]

4. Re-Figuration of Spaces as Long-Term Social Change

When analyzing structural characteristics, researchers focus primarily on the macro-level of social change, which extends over a long period of time—the longue durée (BRAUDEL, 1976; see also BAUR, 2015; SPOHN, 2015), from several decades to millennia. ELIAS described this as follows: "continual, long-term, that is transformations of human-made figurations or aspects of them that usually need no less than three generations to unfold […]" (2003 [1986], p.270; see also TREIBEL, 2008). [26]

It can be assumed that such a fundamental process of change, the re-figuration of spaces, has existed for a considerable amount of time while affecting almost all areas of sociality. An example of such a process unfolding in the long term is WEBER's work on (occidental) rationalization. The beginning of rationalization started with the spread of Protestantism, which successively developed an elective affinity with the spirit of capitalism (WEBER, 1922 [1920]). The process of rationalization thus dates far back in time, transpiring over centuries and extending into all areas of life to this day. Also, the process of civilization examined by ELIAS (1977 [1939]; 1997 [1939]) has been evolving since the Middle Ages, through various stages of development, and is still influential today. [27]

For the analysis of the re-figuration of spaces, such a long-term orientation is necessary, too. For example, in their study on food markets, BAUR, FÜLLING, HERING, and KULKE (2020) examined how local interactions between consumers and retailers are entwined with worldwide trading relations (see also HERING & BAUR, 2019). Upon closer examination, these economic relationships can be traced back to long ago. For example, the beginning of long-distance trade (or, to put it boldly, the beginning of globalization) dates back (at least) to the Neolithic Age (ROBB & FARR, 2005). From the perspective of historical-comparative sociologists, the current cross-cultural transformation process, which is referred to as the re-figuration of spaces, is a long-term social change shaped by specific structural characteristics. [28]

In order to understand what distinguishes the transformation process in the re-figuration of spaces from other forms of large-scale social change and to construct specific comparative dimensions for future research, it is necessary to examine the structural characteristics within the re-figuration process by means of a universally historical-comparative methodological approach. This means that as many re-figuration phenomena as possible have to be empirically examined to identify common structural characteristics. Structural characteristics identified in this way serve as comparative dimensions, which researchers can use to compare the results of an individual re-figuration phenomena analysis with results from other empirical studies. Thus, it can be empirically verified what characterizes the current restructuring of spatial orders as a global process, while at the same time distinguishing regional and contextual differences. [29]

Researchers who support a historical-comparative, causal-analytic, historical-sociology methodology aim to figure out the core of the re-figuration of spaces that dominates all re-figuration phenomena during their sociogenesis (and therefore also the present). Before I can elaborate on a more concrete proposal for this kind of methodological approach, it is first necessary to explain the existing theoretical hypothesis of re-figuration. [30]

5. Structural Characteristics of the Re-Figuration of Spaces

Re-figuration means, first and foremost, an increasing parallelism of old and new forms of social order.

"We speak of a re-figuration because it is not about a dissolution of modernity and its typical structures and differentiation. As we have seen in the example of the re-marking of knowledge […], clear traits of modernity remain as structuring principles in the Communication Society as well. In contrast, communicativization, infrastructuralization, and translocalization introduce a new figuration. This new figuration in turn strengthens tendencies towards dehierarchization, de-structuring and interconnectedness, which makes borders permeable, blurs structural categories and exceeds systems" (KNOBLAUCH, 2017, pp.396-397). [31]

Contemporary society is thus characterized by a fundamental process of change, which is particularly evident in the restructuring of spatial orders.

"If one applies the concept to space, this means that fluid and relational spatial forms (such as networks, layers, clouds, group orbits, etc.) are increasingly coexisting, intermingling or overlaying with territorial spatial forms (such as nation-states, zones, camps, colonies, etc.)" (LÖW, 2018, p.52). [32]

Furthermore, LÖW described the re-figuration of space:

"The term 're-figuration' describes, firstly, the process that has cumulated into a turning point in the late 1960s. While the quality of the social process changed around this time, there is no clearly demarcated starting or end point. Secondly, re-figuration refers to the tension between 'logics' of spatial processes and spatial structures" (pp.52-53). [33]

LÖW thus portrayed re-figuration in relation to spatial orders as an ambivalent process in which homogenization and heterogenization interact (see also Bewegung and Gegenbewegung [movement and counter-movement] in ELIAS's figurational sociology, TREIBEL, 2008). In this process, actions and places are decoupled, emerging territorial logics are no longer only ortsgebunden [bound to places] (LÖW. 2018, p.30), and spatial productions take place maßstabsübergreifend [across scales] (p.58). [34]

This momentous diagnosis of a "massive transformation that we have been witnessing in the last decades" (KNOBLAUCH & LÖW, 2017, p.2) contrasts with a both empirically and theoretically inadequate state of research. Therefore, the general hypothesis of the re-figuration of spaces should be understood as a starting point for a research program. In order to conduct this research program empirically, KNOBLAUCH and LÖW (pp.11-15) referred to three central aspects that are related to re-figuration and simultaneously characterize the ongoing transformation of spatial order: polycontexturalization, mediatization, and translocalization. These three aspects are first to be understood as heuristics. "Since we consider these aspects as hypothetical, we shall sketch these categories in a preliminary way, allowing for additions and corrections by empirical studies" (p.3). [35]

If polycontexturalization, mediatization, and translocalization are understood as structural characteristics, their historical-comparative reconstruction can contribute to advancing the research program on the re-figuration of spaces. If the heuristic proposed by KNOBLAUCH and LÖW stands up to an empirical examination, the structural characteristics of the re-figuration have one thing in common: Because the transformation process they shape is global, they can be observed worldwide and follow common, location-independent patterns. On the downside, these globally apparent structural characteristics encounter highly diverse, regional, and context-specific structures and will consequently be found empirically in various forms. Therefore, using polycontexturalization, mediatization, and translocalization in historical-comparative social research as comparative dimensions offers researchers both the advantage of examining and further developing the theoretical concept of re-figuration and of generating concrete, empirical findings for individual re-figuration phenomena. Furthermore, the historical reconstruction of the genesis of the structural characteristics polycontexturalization, mediatization, and translocalization offers an advantage over previous research approaches on the re-figuration of spaces in that researchers can not only draw conclusions about the present (by comparing contemporary phenomena), but also gain a profound understanding of the historical causes of re-figuration. To do so, I shall discuss these three structural characteristics in more detail before offering a proposal for their reconstruction and use as comparative dimensions. [36]

One key hypothesis of re-figuration researchers is that "bounded social spaces as social contexts of communicative actions" (KNOBLAUCH & LÖW, 2017, p.11) are currently changing. As a result, the borders of formerly demarcated, contextual spaces blur and a growing number of spatial syntheses occur. Based on the work of LUHMANN (1997) on the impossibility of conceiving modern society as clearly defined functional units (KNOBLAUCH, 2017), KNOBLAUCH and LÖW inferred that functional references in the constitution of social spaces increasingly lose their demarcation and, thus, communication becomes polyvalent. Therefore, polycontexturalization maintains that communication refers to different references in various subsystems simultaneously. Regarding the re-figuration of spaces,

"polycontexturalization means that different institutional orders or frames occur simultaneously at one location. […] Polycontexturalization is a process implying bodies, things and meaning, thus affecting space. Parallel to the acceleration of temporal structures, polycontexturalization means the simultaneous relevance of different spatial scales, dimensions and levels. Polycontexturalization implies that we do not expect the mere dissolution of territorial and homogenizing spatial logics" (2017, p.12). [37]

Polycontexturalization denotes that the constitution of spatial orders goes beyond different levels of social aggregation (micro-macro level) and that in this process, "simultaneous references […] to different spatial scales (global, supranational, national, urban, local) of society" (LÖW, 2018, p.57) accelerate. As an example of polycontexturalization, KNOBLAUCH and LÖW cited the work from MASSEY (1993) that sojourning, promenading or shopping in modern inner cities never takes place only in one local context, "but is embedded in global economies, transnational relations between locals and visitors as well as their languages, religions and consumer cultures" (KNOBLAUCH & LÖW, 2017, p.12). [38]

For a methodological elaboration of polycontexturalization as a structural characteristic of re-figuration of spaces, this means that these phenomena must be detectable in empirical studies. For example, researchers need to ask:

Can the assumed simultaneity of institutional orders and frames be found in all parts of modern society?

Are there different stages of polycontexturalization?

Is polycontexturalization a gradual or categorical phenomenon?

Do primarily global references influence the polyvalent restructuring of spatial orders, or rather local, contextual characteristics, or historically grown relations to other contextual spaces that have existed for a long time and are not related to re-figuration? [39]

Answering these questions serves as the basis for conceptualizing polycontexturalization as a structural characteristic of re-figuration and thus, as a valid comparative dimension across cases. [40]

Mediatization is another structural characteristic that shapes re-figuration and can be considered a comparative dimension for research on the re-figuration of spaces. "To the extent that communicative action is being transformed by new technical media, spaces are refigured in a way we will refer to as mediatization" (KNOBLAUCH & LÖW, 2017, p.12). [41]

The usage of new (digital) media, or more precisely, the specific procedures and practices inscribed in these technologies (LINDE, 1982), shapes the re-figuration of spaces. Since new media spread worldwide into all areas of life and thus change (communicative) actions, they also have a significant influence on how spatial orders are currently transformed. KNOBLAUCH and LÖW noted: "mediatization is a mega-process linked to the basic order and transformation of societies" (2017, p.12). [42]

Mediatization is thus a considerably more diffuse aspect of re-figuration than polycontexturalization. This makes it much more difficult to empirically identify mediatization as a structural characteristic, to capture its specific effects on the restructuring of spatial order and, subsequently, to use mediatization as a comparative dimension for the analysis of the re-figuration of spaces. Empirically, the demarcation to other structural characteristics is certainly difficult. However, KNOBLAUCH and LÖW stated that a "specific form of mediatization unfolding in recent decades" (p.13) can be observed, which is linked to the re-figuration of spaces. The crucial issue of this phenomenon is, as KNOBLAUCH and LÖW pointed out with reference to COULDRY and HEPP (2016), the change of the classic mass media with its one-sided communication towards a many-to-many communication in the new media, but also an increase in the frequency and density of one-to-one- and one-to-many communication. According to CASTELLS (2009), this transformation could also be described as mass self-communication, which goes hand in hand with a new form of communication that is no longer hierarchical or characterized by central, institutional actors (KNOBLAUCH & LÖW, 2017). The associated change in communication conditions also has a massive impact on the spatial dimension of communication. This leads to a recontextualization of situations and increased mobility of actors and objects.

"This way, mediatization provides for new potentials and new contexts for action. […] Mediatization does not only affect interpersonal interaction; rather, it is also an institutional process which refigures spaces far beyond the 'media system': it produces new forms of 'communication work' including the methods of industrial production, the dissociation of classical formal organization and the move towards network, circulatory and transnational forms of institutional cooperation […]. The role of mediatization for the re-figuration of space is due to the insertion of the digitalized, interactive and smart intra-active communication technologies into chains of action; it also depends on the construction and standardization of huge infrastructures of communication technologies; although the 'information gap' demonstrates sharp asymmetries on a global scale, the ongoing expansion of infrastructures is one basic driving force for the mediatization of communicative action" (p.13). [43]

In order to empirically identify and flesh out mediatization as a structural characteristic of re-figuration, which can be examined historical-comparatively, it is first necessary to figure out how the production of spatial knowledge by new media can be observed empirically in concrete phenomena—for example, in terms of subjective spatial orientation or cultural and context-related identity constitutions. Especially in the case of such a complex process as mediatization, it is to be expected that in addition to the already assumed effects on the transformation of spatial orders, further phenomena will be found inductively during empirical studies. Mediatization dissolves national and regional boundaries of communication and is, therefore, less dependent on regional-contextual social structures. The effects of mediatization on the transformation of spatial orders will likely be found in relatively similar forms in different regional-contextual areas. For this reason, the structural characteristic mediatization has a high analytic potential as a comparative dimension. On the downside, mediatization as a "mega-process linked to the basic order and transformation of societies" (p.12) is particularly closely interwoven with other transformation phenomena. So it is also possible that mediatization in different contextual spaces could lead to varying effects, because of interactions between new mediatized forms of communication and historically grown communication orders—whether or not this is the case remains an empirical question. [44]

Finally, it is assumed that the transformation of spatial order is driven and shaped by a third structural characteristic—translocalization.

"Translocality here refers to the embedment of social units, such as families, neighbourhoods and religious communities, into circulations linking their different locations. Circulation means mobility based on the expansion, intensification and integration of different infrastructures. It makes it possible to relate the specific location of institutions, networks and individuals with other locations" (p.14). [45]

As a consequence of the re-figuration of spaces, certainties in the accustomed spatial references diminish, accompanied by an increased awareness of the complexity of spatial contexts: localities increasingly become a subject of debate. These proceed not only in a consensual way, for example when legal opinions of international operating actors (such as corporations) and national legal orders meet, but also when "conflicts between individuals, networks and organizations" (p.15) occur (see also LÖW, 2018). In contrast to GIDDENS's (1991) analysis of disembedding during globalization, KNOBLAUCH and LÖW (2017) did not understand translocalization as the dissolution of social relations from local contexts. They referred to the embedding of social units (for example, families) in new forms of spatial relationships, meaning simultaneous anchorages in several places (see also LÖW, 2018). [46]

Furthermore, translocalization differs from previous globalization diagnoses as globalization is a process that can be traced back a considerable period of time, "while translocalization has only become dominant in the last decades" (KNOBLAUCH & LÖW, 2017, p.15). The specifics of translocalization additionally differ from already described globalization phenomena, since translocalization does not describe spatial transformations as isolated or vertically structured phenomena. Thus, the third structural characteristic of re-figuration does not describe the separation into "here and there, close and far, local and global" (ibid.), but rather encompasses the simultaneity and interdependence of locality and non-locality. Translocalization leads to the virtual presence of actors without a physical co-presence, simultaneous actions in different places and the synthesis of virtual and physical (or real) places. A physical presence is no longer a prerequisite for direct interactions, but nevertheless, a concrete presence is generated in the sense of a "connected presence," as formulated by KNOBLAUCH and LÖW (ibid.) in reference to LICOPPE (2004). However, KNOBLAUCH and LÖW defined translocalization not only as a phenomenon of digitalization and the use of technological means of communication but also considered it inseparable from the circulation of persons and objects. In this context, translocalization is not primarily a detraditionalization process (as described by globalization research), instead "translocalization involves the creation of new spaces," leads to increased transnational mobility and "increases the relationality of locations," thus leading to "more selective and reflexive forms of belonging to locations" (2017, p.16). As an example, KNOBLAUCH and LÖW cited the work of BECK (2002) and identified global warming as a translocal phenomenon, which has consequences for some locations although those consequences are generated by actors belonging to other locations. [47]

Consequently, in order to conceptualize translocalization as a structural characteristic for historical-comparative research, it is necessary to analyze empirical phenomena that reveal the simultaneities and interactions of different actors at multiple locations. In doing so, it is particularly important to ensure that translocal re-figuration phenomena are not equated with those of mediatization, since these often appear similar. However, translocalization represents an independent structural characteristic that encompasses the spatial changes that (communicative) action undergoes through mediatization (KNOBLAUCH, 2017). In addition, the empirical analysis of translocalization presents researchers with the difficult task of investigating connections between actions and contexts that are spatially (but also temporally) distant. The perspective of causal-analytical historical sociologists is particularly suitable for this problem, as it focuses on cause-and-effect mechanisms over long periods of time and long chains of action. In summary, the developments and effects of translocalization phenomena have to be studied in location-independent contexts along with intertwining, long-term actions (with and without a physical co-presence of the actors) in different localities. [48]

6. An Outline for a Historical-Comparative Methodological Approach to Analyzing the Re-Figuration of Spaces

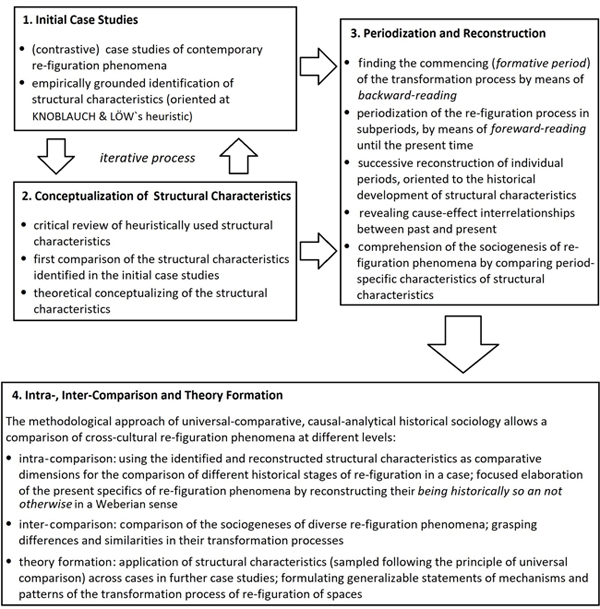

How to can the methodology of historical-comparative sociology be used in general, and in particular the conceptualization of structural characteristics aiming to build comparative dimensions for the cross-cultural comparison and analysis of the re-figuration of spaces? In the current state of research, it is not yet possible to produce an elaborate and practical guide for a historical-comparative methodology of research on the re-figuration of spaces. Hence, I will formulate a rough draft of such a methodology below (Figure 2), which deals with how structural characteristics can first be identified (and if necessary adapted or revised) in the present, how single periods of re-figuration phenomena can be understood by means of historical reconstruction, how empirically grounded comparative dimensions can be conceptualized, and finally how researchers can apply it in cross-cultural comparison.

Figure 2: Proposal for a research design on the re-figuration of spaces, which is based on the universally comparative, causal-analytic

methodology of historical sociology [49]

6.1 Step 1: Initial case studies in the present

In the sense of universal comparison, as proposed by TILLY (1984), the research process begins with the selection of re-figuration phenomena in the present, which should be as heterogeneous as possible. These selected phenomena are investigated in initial case studies. Based on a purposeful, contrasting case selection, the sampling criteria for the figuration phenomena should be distinct, with spatial and/or contextual differences, a wide scope of social areas (such as the economy, education, sport, etc.), and different levels of social aggregation (micro- and macro-level). With these initial case studies, researchers aim to identify the structural characteristics of the re-figuration process empirically in individual cases and to describe them using a thick description. [50]

Re-figuration of space researchers have proposed a thesis for a global transformation of spatial orders that is shaped and driven by three structural characteristics: polycontexturalization, mediatization, and translocalization. Consequently, these three structural characteristics have to be empirically verifiable worldwide—that is, independently of social areas, different cultures or geographical regions. At the same time, it can be assumed that these three structural characteristics exhibit context-specific distinctions that render it difficult to identify generalizable aspects of social change related to the re-figuration process. The first step towards a historical-comparative approach is therefore to grasp the manifestation of the structural characteristics descriptively in the present by analyzing phenomena that are currently considered typical of re-figuration. [51]

This procedure allows us to examine whether the heuristics of the structural characteristics (see Section 5) can actually be found empirically, or whether the heuristic has to be modified, extended or rejected. Especially in a research program as ambitious as that for the re-figuration of spaces, it is crucial to critically scrutinize theoretical assumptions at early stages in the research process: the basic theoretical concepts must first prove themselves in initial present-day case studies before researchers can carry out s large-scale, cross-case historical comparison in the sense of longue durée. In principle, there are three approaches to conceptualize structural characteristics (BAUR, BRAUNISCH & HERGESELL, 2021; HERGESELL, BAUR & BRAUNISCH, 2020):

Analytical specification: it is possible to investigate already known processes further based on in-depth preliminary work and knowledge about the research object (or by reading pertinent literature). Thus, researchers can carry out an analytical specification of the structural characteristics. Since the state of research on re-figuration does not permit this yet, this possibility is currently not appropriate.

Theoretical consideration: it is also possible to derive a research interest based on theoretical considerations and to use theoretically generated theses as guidance for empirical investigations. Of course, this procedure requires quite advanced preliminary theoretical work. Otherwise, empirical findings obtained in this way risk being uninterpretable in relation to the theoretical preliminary work, empirical results are forced into unsuitable theoretical concepts or unexpected (explorative) findings are ignored.

Empirical grounding: researchers can also use a much more complex and inductive, albeit essentially more relevant object procedure to identify structural characteristics. Using this approach, researchers have the advantage of a focused theory formation and reduced risk of not being able to react sensitively to unexpected empirical findings. The empirically grounded identification of structural characteristics requires prior empirical (case) studies in the present before universal, generalizable structural characteristics of the re-figuration process can be formulated (BAUR & HERING, 2017; BAUR et al., 2021; HERGESELL, 2019). In multiple initial case studies, the dominant dynamics of a social transformation are first worked out and then reconstructed historically in a second step in order to understand their sociogenesis, courses, and patterns. In this way, researchers can comprehend cause-and-effect principles within the structural characteristic's interaction much more precisely than in analyses mainly focused on the present. This procedure is therefore a two-phase research process. A prior analysis in the present precedes the historical reconstruction, aiming to generate generalizable comparative dimensions. The first phase serves as an inductive determination of those processes, which characterize the re-figuration and therefore have to be reconstructed historically. [52]

A combination of the second (theoretical consideration) and the third (empirically grounded identification) approach is adequate for the proposed historical-comparative methodology. As discussed in the section above, KNOBLAUCH and LÖW (2017) have already developed a heuristic of three structural characteristics (polycontexturalization, mediatization, and translocalization) based on theoretical considerations, which can be used as a basis for the development of comparative dimensions. However, this heuristic has yet to prove itself empirically and requires empirical driven elaboration in order to provide sufficient orientation for ensuring historical reconstruction. Therefore, given the current state of research, the most efficient approach is to apply KNOBLAUCH and LÖW's heuristic as a theoretical orientation for the empirically driven, successive identification of structural characteristics in initial case studies on re-figuration phenomena. [53]

The first step in the research process can be illustrated by the research of BAUR et al. (2020) on consumers' and producers' spatial knowledge (see also HERING & BAUR 2019) and the research of CASTILLO ULLA, HEINRICH, MILLION and SCHWERER (2021) on the spatial knowledge of children and young adults in planning contexts (see also MILLION, CASTILLO ULLA, HEINRICH & SCHWERER, 2020), both as part of the CRC re-figuration of spaces research agenda. BAUR et al. (2020) and HERING and BAUR (2019) investigated which spatial knowledge of consumers and producers becomes relevant in the fresh produce trade and how this knowledge changes as a result of the re-figuration. CASTILLO ULLA et al. (2021) and MILLION et al. (2020) analyzed the changes in the spatial knowledge of children and young adults since the 1970s. The researchers wanted to find out how the re-figuration of spatial knowledge affects contemporaneous educational and planning processes. [54]

In both research projects, the researchers investigated re-figuration phenomena, which showed verifiable effects in the present, but which originated in the past. They investigated re-figuration in two very different fields (economy and education), which is why their research is suitable for examining whether and which constant structural characteristics of re-figuration can be found across the cases. According to the procedure in step 1, it would be necessary in both projects to examine, by means of theoretical consideration and empirically grounded identification, which patterns characterize the re-figuration process in the individual cases. After the researchers have empirically elaborated and described these patterns, they can evaluate whether these patterns correspond to the three structural characteristics polycontexturalization, mediatization, and translocalization, and how they are concretely shaped in their individual cases. [55]

For example, BAUR et al. (2020) (in theory) considered that polycontextual effects of re-figuration have to be found along supply chains by necessity due to the spatial position of the involved actors (see also HERING & BAUR, 2019). The purpose of the initial case studies is now to provide first-hand evidence for this theoretical consideration and, if necessary, to differentiate it based on empirical findings. Thus, the structural characteristic of polycontexturalization could be presented in detail for the case involving the fresh produce trade. [56]

As a second example, CASTILLO ULLA et al. (2021) considered that points of change in the spatial knowledge of children and young adults could be related to processes such as the rise of car culture, political emancipation movements, and changing educational models, which triggered current polycontexturalization (see also CASTILLO ULLA, MILLION & SCHWERER, 2018; MILLION et al., 2020). In the first step of the research process, the researchers will have to examine whether the considered effects can actually be verified, how they can be described in detail, and whether they can be interpreted as a phenomenon of polycontexturalization. [57]

Ideally, in as many and diverse initial case studies as possible, research teams will examine whether and in which individual manifestations KNOBLAUCH and LÖW's (2017) theoretical conceptualization of the three structural characteristics can be confirmed. However, in practice, it will be difficult to comprehensively examine all three structural characteristics in any initial case studies. This underlines the importance of including a sufficient number of case studies that make it possible to illustrate concrete empirical findings for particular re-figuration phenomena. [58]

6.2 Step 2: Identification and conceptualization of structural characteristics

After (initial) empirical findings have been obtained in the respective contemporary case studies, in Step 2, researchers will carry out a theoretical conceptualization of the discovered structural characteristics that characterize and prompt the re-figuration phenomena. This step will take place iteratively with the first one and aims to conceptualize the structural characteristics inductively based on empirical evidence. The researchers need to theoretically conceptualize (thick description) the structural characteristics identified in their respective initial case studies and thus successively test their findings in the present to determine their eligibility as cross-case historical-comparative dimensions. This can be achieved, on the one hand, by analyzing re-figuration phenomena rigorously in separate case studies and, on the other hand, by comparing the respective findings with those of other initial case studies in order to evaluate the structural characteristics for transferability or to identify singular specifics of individual re-figuration phenomena. [59]

Ideally, the research teams for the various initially case studies will work closely together at this stage in the research process and discuss the theoretical conceptualization of their cases critically. Step 2 will be complete when the structural characteristics have been classified enough to be separated from other processes in the subsequent historical reconstruction (Step 3) and their causal relationship with the initially analyzed re-figuration phenomenon has become apparent. [60]

For example, BAUR et al. (2020) should have asked whether the dissolution of fixed spatial references and an increase in communication between previously uninvolved actors in the fresh produce trade associated with the structural characteristic polycontexturalization can be found in comparable ways in other re-figuration phenomena. Is it possible to apply the discovered patterns to other phenomena in the re-figuration process? Does polycontexturalization also show itself in the transformation process of children and young adult's spatial knowledge (CASTILLO ULLA et al., 2021) through the blurring of fixed spatial references and increased communication between previously dependent actors? If not, which differences might have been missed by the researchers in the theoretical conceptualization of the structural characteristic of polycontexturalization and should be reconsidered? [61]

Of course, the theoretical conceptualization should ideally not remain limited to a single structural characteristic or only a few research fields. Especially in such an extensive research agenda as the re-figuration of spaces, researchers should compare the findings of as many and heterogeneous initially case studies as possible. For example, in Step 2, the research teams could also discuss whether the empirical findings of the structural characteristics mediatization and translocalization is comparable to the effects of artificial intelligence in smart cities (LÖW, 2019) due to the use of locative media leading to a cyber-physical conflation of conventional and virtual communication spaces (LETTKEMANN & SCHULZ-SCHAEFFER, 2020). [62]

In concrete terms, in Step 2, researchers have to determine in which social contexts, at what levels of social aggregation, and with the involvement of which actors the structural characteristics shape the social transformation of spatial order in a dominant and cross-case pattern. However, the conceptualization of the structural characteristics must first be regarded as preliminary. In order to understand their fundamental sociogenesis and to use them as substantial comparative dimensions for a large-scale, cross-cultural analysis of re-figuration, it is necessary to reconstruct the emergence of the structural characteristics identified in the present through historical reconstruction (Step 3). The conceptualization in the present lays the groundwork for this reconstruction as a primary investigation. In addition to validating theoretical assumptions (see for example KNOBLAUCH & LÖW's heuristic from 2017), the empirical investigation in the present has another essential objective. Since the sociogenesis of re-figuration phenomena is very complex, it is impossible to fully reconstruct all the processes leading to the current social transformation of re-figuration. Therefore, focusing on the structural characteristics identified in initial case studies is a precondition for a systematic historical reconstruction of the sociogenesis of re-figuration processes and the subsequent comparison thereof. [63]

6.3 Step 3: Periodization and reconstruction of long-term social structural changes

If the structural characteristics are conceptualized theoretically in the respective initial case studies, it will be necessary to identify in Step 3 the formative Periode [formative period] (BERKING & SCHWENK, 2011, p.256; see also HERGESELL et al., 2020) of their impact, and thus the beginning of the re-figuration process. Thereby, the structural characteristics are also distinguished from previous or concurrent processes of change. [64]

The re-figuration process will then be successively reconstructed from the beginning of its development up to the present-day, whereby the structural characteristics serve as guidelines of this reconstruction. This will enable a profound understanding of the re-figuration process's course, its mechanisms and patterns. In this way, the structural characteristics are presented in detail as drivers of the re-figuration process for each individual case and, at the same time, their function as a comparison dimension is refined. Thus, after conceptualizing the structural characteristics in Step 2, their historical development, which leads to re-figuration in the present, can be systematically reconstructed from their inception in Step 3. [65]

As KNOBLAUCH and LÖW (2017) noted, the re-figuration of spaces has been apparent for several decades. Nevertheless, it is only in the recent past that the transformation of spatial orders has increasingly become evident as the most dominant process in contemporary society. In order to understand how this development occurred and how their fundamental driving forces (i.e., their structural characteristics) revealed their social impact, a detailed historical reconstruction is necessary. Only by reconstructing the sociogenesis of re-figuration phenomena from its beginning is it possible to access the mechanisms and patterns of these transformation processes systematically. For this purpose, a socio-historical research procedure is appropriate that enables the successive, separate reconstruction of single developments during the sociogenesis of a social entity and then reveals causal connections between these developments: the so-called periodization (BAUR, 2005, pp.82; see also BAUR, 2017; HERGESELL et al., 2020), meaning the subdivision of a process into individual subperiods. [66]

On the one hand, periodization is necessary in order to provide empirical access to the immense complexity of historical processes. On the other hand, it allows researchers to carry out a comparison at multiple levels:

The developments of the structural characteristics polycontexturalization, mediatization, and translocalization can be compared within different periods, and thus researchers can understand the specifics of their effects in the present within one case in the sense of the Weberian causes of their being-historically-so-and-not-otherwise.