Volume 23, No. 1, Art. 4 – January 2022

Biographical Reconstructive Network Analysis (BRNA): A Life Historical Approach in Social Network Analysis of Older Migrants in Australia

Rosa Brandhorst & Lukasz Krzyzowski

Abstract: While qualitative approaches in social network analysis have been flourishing, the research processes, especially data analysis, are still often informed by the structural network analysis paradigm. Furthermore, there is a lack of analytical approaches and systematic discussion on possible ways to analyze network data collected in the qualitative interpretative research paradigm. To close this gap, we propose a methodological approach that builds on the cultural turn in social network analysis that advocates a focus on subjective patterns of interpretation and historical/processual configurations. We formulate a biographical network analytical perspective, analyzing the development of a social network through a person's life history. Based on a case study derived from a research project on transnational support networks of older migrants in Perth, Australia, we aim to explicate the analytical procedure of the biographical reconstructive network analysis (BRNA). BRNA is a collaboratively developed analytical procedure for social network data collection and analysis. During the BRNA data collection, both the biographical-narrative interview and ego-centric network maps are implemented. The BRNA data analysis procedure is informed by biographical reconstructive research principles to fully understand and reconstruct the dynamics of social networks during the life course.

Key words: biographical reconstructive network analysis; qualitative network analysis; biographical research; social support networks; personal social network analysis, network dynamics; interpretative research

Table of Contents

1. Introduction

2. Interpretative, Biographical and Processual Perspectives in Social Network Analysis

3. BRNA—Explanation of the Method and its Implementation: Transnational Support Networks of Older Migrants in Australia

3.1 BRNA data collection

3.1.1 Step I: The biographical-narrative interview

3.1.2 Step II: Ego-centric network maps

3.2 BRNA data analysis

3.2.1 Step I: Sequential analysis of the social network

3.2.2 Step II: Analysis of presentation of the network map

3.2.3 Step III: Reconstruction of the social network history

3.2.4 Step IV: Contrastive comparison of the life history, the social network map and life story

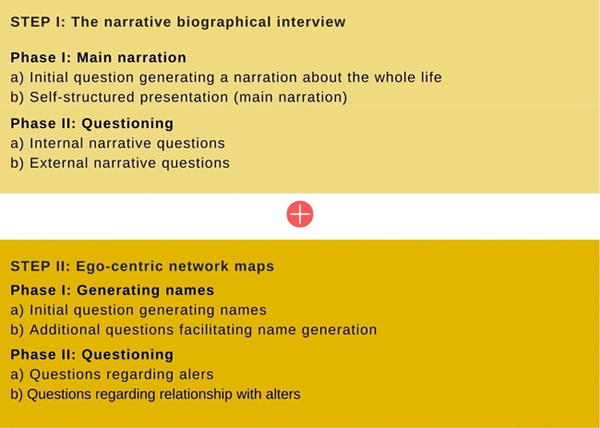

3.2.5 Step V: Development of types and contrastive comparison

4. Conclusion

While qualitative approaches in social network analysis have been flourishing, the research processes, especially data analysis, are still often informed by the structural network analysis paradigm (DIAZ-BONE, 2007; HERZ & OLIVIER, 2012; HERZ, PETERS & TRUSCHKAT, 2015; HOLLSTEIN, 2010). In fact, the majority of qualitative network studies rely on mixing methods and aggregative approaches that focus on patterns, themes and structures (BERNARDI, 2011; CROSSLEY & EDWARDS, 2016; HOLLSTEIN, 2011). This knowledge cannot be underestimated, but we argue that knowing structural patterns of relations provides neither a nuanced picture of networks nor insight into relational, interactive and processual aspects of network formation and the "Meaning Structure" (FUHSE, 2009). Furthermore, there is a lack of analytical approaches and systematic discussion on possible ways to analyze network data collected in a qualitative and particularly interpretative network analysis paradigm (DIAZ-BONE, 2007). Often even qualitative approaches tend to follow a quantitative, structural deterministic logic (OANCEA, PETOUR & ATKINSON, 2017). For example, ego-centric maps (KAHN & ANTONUCCI, 1980), commonly used in qualitative network data collection, capture only a current state of personal networks that are analyzed by predefined categories and structural measurements. [1]

The dynamic aspects of networks are usually investigated with the convoy model (KAHN & ANTONUCCI, 1980; PLATH, 1980). The core assumption of the convoy model is that individuals are accompanied by significant others during their life course. Relationships play different roles in the lives of individuals and are in their nature multidimensional, vary in their type (i.e., friend, parents), importance, structure (i.e., frequency of contact), and functions (i.e., exchange of support, transfer of information). Notably, the past experiences with meaningful relationships affect current and future convoys. Even though the model focuses on the change of relationships over time, it captures "objective" circumstances under which social relations emerge as most important and influential by implementing the pattern-centered approaches to cluster and profile social convoys (ANTONUCCI, AJROUCH & BIRDITT, 2014; BIRDITT & ANTONUCCI, 2007). The spatial and temporal boundaries of network formation as well as critical events, including transnational migration, identification of key decision-making episodes for network re-configuration are often ignored (WISSINK & MAZZUCATO, 2018). [2]

Our approach builds on the relational sociology and the cultural turn in social network analysis that advocates a focus on subjective patterns of interpretation, and processual configurations in network analysis (CROSSLEY, 2010). The main advocates of the cultural turn in social network analysis, EMIRBAYER and GOODWIN (1994), accused network analysis of structural determinism, which neglects subjective patterns of interpretation, actors' beliefs, and the significance of sociocultural and political discourses and historical configurations. EMIRBAYER (1997) suggested that to understand the social world relationally, researchers have to pay closer attention to unfolding relations and dynamics of social networks as a configurational process of (trans)forming personal relations into certain kinds of figurations1). As agents of our lives, people form relations that are navigated through interdependency and are able to reconfigure relations and networks. Relationships are formed therefore on shared values, cultural tastes, status, social expectations, and norms (LIZARDO, 2006). [3]

There are recent innovative approaches in qualitative social network analysis that focus on subjective patterns of interpretation and on processual perspectives (e.g., RYAN, MULHOLLAND & AGOSTON, 2014). SOMMER and GAMPER (2021) demonstrated that qualitative approaches to social network analysis are particularly useful to study temporal and spatial changes of social ties and agency of network members. This argument is also supported by KINDLER (2021), who applied qualitative social network analysis to research migrant networks and underlying contextual factors enabling or disabling forming of ties in a particular institutional and cultural context in a host country. RYAN and D'ANGELO (2018), RYAN and DAHINDEN (2021) as well as WISSINK and MAZZUCATO (2017) used longitudinal network analytical methods to capture the network changes of migrants. The proposed methodological approach in this article follows these qualitative, interpretative and processual perspectives in social network analysis, contributing to developing a biographical network methodology (see also ARMITAGE, 2016; BILECEN & AMELINA, 2017; HOLLSTEIN, 2002). [4]

In this article we aim to discuss the benefits of combining a network perspective with a biographical perspective for a better understanding of the formation and contextualized configuration of social networks. This leads us to formulate a reconstructive biographical network analytical perspective, proposing a historical-processual lens, analyzing the development of the network through a person's life history. We examine the lived relationships that were formed in certain historical, biographical and relational settings to fully understand the ego-centric maps generated by the interviewees. Based on a case study drawn from the qualitative research project "Aging and New Media: A New Analysis of Older Australians' Support Networks," we aim to explicate the analytical procedure of the biographical reconstructive network analysis (BRNA). We propose BRNA data collection: a method triangulation of the biographical-narrative interview supplemented by ego-centric maps, and a BRNA data analysis procedure informed by reconstructive biographical research (ROSENTHAL, 1995, 2004, 2018) to study social networks. [5]

In this article, we will first describe the current discussion on including an interpretative and biographical perspective in the analysis of social networks (Section 2). Afterwards, we will present our research context and explicate our method procedure in detail by means of a case study (Section 3), leading on to conclusions (Section 4). [6]

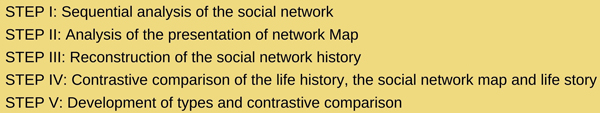

2. Interpretative, Biographical and Processual Perspectives in Social Network Analysis

Social network analysis originally drew from the structuralist social network tradition (WELLMAN & BERKOVITZ, 1988). Formal social network analysis promotes relational and structural properties of human and non-human relations. The metaphorical usage of the concept of "network" was replaced with structural models and procedures distinguishing different types of network structures based on the variation of relationships and quantitative measurements. An individual's actions are, according to this perspective, determined by the social network structure i.e., structural determinism. Subjective patterns of interpretation as well as processual and interactional dimensions of networks and the agency of individuals were understudied. The main focus has been on quantitatively investigated actors, ties, dyads, positional properties of actors in networks, and structural properties of networks (WASSERMAN & FAUST, 1994). This approach diminishes the active role of individuals in creating, maintaining and interpreting their networks and relationships, as well as the situational, contextual, and historical aspects of agency (HOLLSTEIN & PFEFFER, 2010; HOLLSTEIN & STRAUS, 2006). As a consequence, critics of structural analysis suggest that focusing on: 1. the structure of social relationships, 2. the individual actors, and 3. the connections they form does not provide sufficient analytical richness, and that configurational aspects are omitted (PACHUCKI & BREIGER, 2010; WHITE, 2008). [7]

However, social anthropology has significantly contributed to the development of social network research by focusing on single case studies and data-based hypothesis generation within cases and/or across cases (BRADY & COLLIER, 2004). This approach stems from the foundations of qualitative interpretative social research by the Chicago School of Sociology. THOMAS and ZNANIECKI (1958 [1918-1920] made the first attempt to empirically apply the principle of reconstructing subjective perspectives and the interactive constitution of interactions on the basis of an individual case. Rather than having a priori hypotheses and theories, these approaches to social networks tend to develop hypotheses and theories based on within case study and cross case study analyses. BOTT (1957) conducted ethnographic research following analytic induction principles resulting in the development of methodological anchor points for anthropologically- driven social network analysis. Another example is the seminal work of the Manchester School of Anthropology (MITCHELL, 1969) adding a set of concepts describing social networks (e.g., durability or density). These approaches can be seen as first steps towards a cultural turn and a qualitative interpretative perspective in social network analysis, on which our approach of the BRNA builds on. [8]

Formal SNA has been further criticized for examining relational structures in their Sosein [being-as it-is resp. current manifestation], dismissing their genesis (HEPP, 2010, p.227) and interactional "processuality." As social relationships are formed during the life course, they are based on definitions of situations that are shaped by previous experiences and manifest as personalized strategies toward social worlds (STRAUSS, 1993). [9]

In analyzing the meaning of social relationships and networks it is important to understand that forming ties can have different meanings over time and for different members of the network. BIDART and LAVENU (2005) stressed that "networks of personal relations evolve over time. They reflect and go with socialization. Their history and dynamics contribute to their present structure" (p.359). In this article we aim to discuss the knowledge gain of combining a relational network perspective with a biographical perspective. A biographical perspective helps to trace the becoming of social phenomena such as social networks in the life course (ROSENTHAL, 2012). One can only fully understand a current social network if one knows how the relationships were established and developed over time. Furthermore, current meaning structures and practices can only be fully understood in relation to the layering of experiences and dynamics of the biography. Hence, the current decisions to maintain a relationship or establish contact, or provide or withdraw social support, are not only shaped by the current situation and relationships, but also dependent on past biographical experiences and on patterns of interpretations of these relationships acquired during the life course (HOLLSTEIN, 2002). [10]

Hence, to understand a social network, its meaning structures and the development of the social relations over time need to be reconstructed. The composition of networks or the positions within them do not translate automatically into actions—as suggested by the convoy model. Instead, personal actions depend on the situational understanding of a current position that is informed by previous experiences and patterns of meaning (HOLLSTEIN, 2002). Social networks are not only present per se but are constantly produced through interactions and relationships formed across the life course. Implementing a biographical perspective to social network research generates a contextual and processual understanding of social network dynamics instead of a correlational examination of variables. [11]

The question of different structural positions of actors in social networks can be better understood by implying a biographical perspective, including previous experiences and personal interpretation into the social network analysis. This would shield SNA from network "amnesia": a tendency to diminish processual and relational foundations of social networks (SALVINI, 2010, p.373). There are developing analytical approaches in the field of social networks that call for inclusion of biographical, retrospective, and processual perspectives in the analysis of social networks and vice versa. BILECEN and AMELINA (2017) discussed the potential of including a social network analytical perspective in biographical research, combining ego-centric network maps with semi-structured interviews. RYAN and D'ANGELO (2018) used longitudinal network analytical methods to understand the network change in the life course and through time, combining narrative approaches and network visualizations. A longitudinal approach to the study of social networks provides an opportunity to conduct systematic, empirical observations of network re-configurations and to go "beyond the snapshot" by integrating the temporal, spatial, and relational nature of social networks into micro-level methodological frameworks (KINDLER, 2021; RYAN & DAHINDEN, 2021; RYAN & D'ANGELO, 2018; WISSINK & MAZZUCATO, 2017). BRANDHORST (2015) used a reconstructive biographical and multi-sited ethnographical approach in the analysis of transnational family networks. KRZYZOWSKI (2017) implemented a geographical map-elicitation technique to generate migrants' social networks combined with multi-sited ethnography and a qualitative longitudinal research design. The multi-sited approach allows researchers to capture a spatial dimension by incorporating the perspectives of network members residing in various locations. Temporal dimensions of transnational networks were investigated during three waves of qualitative research, including in-depth interviews and online focus groups. However, a longitudinal approach to network research is time consuming, can be applied only for a relatively short period of time, is burdensome for study participants, and still cannot sufficiently explore transformative past life events, turning points, and critical events (LUBBERS, MOLINA & MCCARTY, 2021). Visual methods for network data collection and representation, including photo-based elicitation of retrospective personal network data are further increasingly used in network research (D'ANGELO, RYAN & TUBARO 2016; TUBARO, RYAN & D'ANGELO 2016). [12]

ARMITAGE (2016) proposed a visual biographical network method to explore the social history of networks. It combines life story interviews and social network maps. By linking these methods ARMITAGE aimed to uncover the current social network, "its composition and structure, originated and evolved to its current state" (p.3). His approach is instructive for the BRNA method as he combined a biographical approach with a network analytical lens and sees both approaches as complementing perspectives on the researched phenomenon. Whereas ARMITAGE used qualitative life stories for in the data collection, the structural measurements were implemented to the network data analysis. BRNA follows this vein of the biographical and processual perspectives; however, it goes a step further by developing a qualitative interpretative biography-led analytical perspective on social networks. [13]

In the same vein, HOLLSTEIN (2002) in her study on widowhood analyzed the changes of relationships in the biography using a qualitative network methodology. Her analytical approach simultaneously aimed at tracing the change of social networks and capturing subjective meaning structures on the level of single case studies. She worked with biographical-narrative interviews that were then combined with network name generators to trace the rules of change of informal social relationships and the individual meaning of these. Based on these case studies, HOLLSTEIN developed types of network transformation. [14]

The proposed methodological approach of the BRNA in this article follows these qualitative interpretative and processual perspectives in social network analysis. However, we take the biographical perspective on social networks a step further by proposing a biography-led procedure of analysis. We adhere to the principle of reconstructive biographical research that assumes that social phenomena can only be understood and explained if their genesis is reconstructed (ROSENTHAL, 1995, 2004, 2018). We propose a specific methodological procedure, which we introduce and explicate below as BRNA to analyze the becoming of social networks within a life history. [15]

3. BRNA—Explanation of the Method and its Implementation: Transnational Support Networks of Older Migrants in Australia

In this section we present BRNA, drawing on a case study taken from our sample of the Australian Research Council-funded research project "Ageing and New Media: A New Analysis of Older Australians' Support Networks," led by Loretta BALDASSAR and Raelene WILDING. The aim of this study (conducted from 2017 to 2020) was to analyze proximate and distant, local and transnational support networks of older Australians and older migrants in Australia. First, we describe the BRNA data collection, followed by BRNA data analysis. [16]

In the data collection of biographical reconstructive network analysis (BRNA) we propose a triangulation of the biographical-narrative interview (SCHÜTZE, 1976, 1983, 2005 [1984]) with ego-centric network maps (originating in the hierarchical mapping technique, KAHN & ANTONUCCI, 1980). In Fig. 1 we present the BRNA data collection procedure that consists of two steps, reflecting the two methods used for data collection:

Fig. 1: A data collection procedure [17]

3.1.1 Step I: The biographical-narrative interview

Developed by SCHÜTZE in the 1970s, the biographical-narrative interview has become a well-established method in social sciences and has been developed further in terms of questioning techniques (ROSENTHAL, 1995, pp.186-207; SCHÜTZE, 1977, 1983). According to SCHÜTZE (1977), narrations are particularly suitable for studying people's actions, experiences and interpretations. The biographical-narrative interview stems from the idea to ask about the entire life story, independent of the research questions. Hence, while conducting an interview, we did not focus on parts or individual phases of the biography where our researched phenomenon (i.e., migration or the current social support network) becomes relevant. Instead we looked at the social phenomenon in the context of the life course based on the narration produced by the interviewee, embedded in an autonomous presentation of his/her own life. This allowed us to follow the principle of openness of interpretative research and to only ask about topics that were mentioned by the interviewee. [18]

The biographical-narrative interview is divided into two phases as suggested by SCHÜTZE (1983, 2005 [1984], see Fig. 1). In the initial stage the interviewer asks about the interviewee's life story. In our research project the initial narrative question was: "Could you tell me about your life story, from your birth until today". Subsequently, in the phase of main narration the interviewee produced a long, self-structured narration, uninterrupted by the interviewer. After the main narration the second phase (questioning) began and the interviewer asked internal narrative questions about the issues that the interviewee had mentioned in the main narration, following the thematic structure of the main narration and trying to keep as close as possible to the vernacular of the interviewee. To evocate narrations, narrative-generating questions were posed2). In the final stage, the external narrative questions, the interviewer asked questions about topics which were not mentioned in the interview but might have been relevant to the research topic. [19]

By starting the interview as an open narration, we were able to gather information on the dynamics of the interviewee's personal network in a particular historical and social context. Having the ego-centric map component at the beginning of the interview would most probably influence the narration. Therefore, the ego-centric map was introduced at the final stage of BRNA step I (see Fig. 1). [20]

3.1.2 Step II: Ego-centric network maps

The second stage of BRNA starts with introduction of the ego-centric network map (KAHN & ANTONUCCI, 1980), a well-established procedure to capture emotional closeness and importance of network relationships. We introduced the network map at the end of the external narrative questions of the interview. The name generator was based on importance of people in life, according to the interviewee's perspective. We started with the initial question:

"Think about the people who have been most important to you and list them in the circles. In the inner circle please place people who are most important and very important for you. In the outer circle place people that are less important, but should still be named." [21]

We also asked additional questions facilitating the generation of names:

The inner circle included the participant's response to the question "think about people who are so important that it is hard to imagine life without them."

The second circle consisted of "people to whom you may not feel quite that close but who are still important to you."

The outer circle comprised "people whom you haven't already mentioned but who are close enough and important enough in your life that they should be placed in your personal network." [22]

During the second phase of the ego-centric network map, we asked questions about each network member, relationships formed with the interviewee, and the exchange of support. Including ego-centric maps allowed us to better understand the current composition of the personal network. The name generators were particularly useful to gather information about the meaning ascribed to particular relationships and to the personal network as such. The relation-oriented questions focused on the support network and gave us information about different forms of social support and care important to the interviewee at the time of conducting the interview. [23]

Following a biographical perspective, in order to understand a current social support network, it is not enough to interpret the synchronic presentation of the ego-centric network map generated by ego (interviewee). Instead we need to understand the genesis of the social network, and to analyze the social network in the process of its creation, reproduction and transformation. According to reconstructive biographical research in order to understand and explain people's actions it is necessary to understand both the subjective perspective of the actors and the courses of action (ROSENTHAL, 2004). To arrive at an understanding, we analyzed the current perspective shown in the interview text and the ego-centric network map and the course of action and social network dynamics as manifested in the life history in the past separately. [24]

In the BRNA data analysis, we followed the steps of case reconstruction according to ROSENTHAL (1995, 2004, 2018), 1. the sequential analysis of biographical data, 2. the text-and thematic field analysis, 3. the reconstruction of the experienced life history, 4. the microanalysis of individual text segments, 5. the contrastive comparison of the life history and the life story, and 6. the formulation of types. However, in our proposed BRNA method we added analytical steps that focus on the social network. In the following (see Fig. 2), we explicate in detail our proposed methodological procedure and our proposed five steps of BRNA data analysis:

Fig. 2: BRNA data analysis [25]

In a reconstructive analysis, categories are not derived from a theory or the results of the first interview analysis. Instead, every interview is analyzed separately and particular segments of the interview are reconstructed in relation to the whole interview and the historical context and structural rules that link parts of the whole biography (ROSENTHAL, 1995). The principle of reconstruction can be applied most consistently with a method that follows abductive and sequential reasoning. The sequential analysis requires the interpretation of biographical data, interview text segments and social network data in a historical, processual order, according to the sequence of their creation (ROSENTHAL, 2004). It demands the decontextualization of the interviewer's knowledge of how the interview continues or respectively how the biography develops. The biographical case reconstruction, reconstructs the interaction sequences or the production of a spoken text step by step in small analytical units. The formulation and testing of hypotheses is based on the procedure of abduction, developed by PEIRCE (1980 [1933]). Here hypotheses are derived and tested within a particular case (see Step I).3) [26]

3.2.1 Step I: Sequential analysis of the social network

The first step of analysis, sequential analysis of the social network, is informed by the principles of the sequential analysis of biographical data of the biographical case reconstruction, in which the lived life as experienced by the interviewee (and free of the interpretation of the biographer) in the temporal sequence/chronological order of the events in the life course is analyzed (ROSENTHAL, 2004, p.54). Retrospective data or the reconstruction of the patterns of action and meanings of social relationships in the past are not unproblematic. It would be best to trace a biography longitudinally across the whole life course. However, the sequential analysis of biographical data tries to approximate itself as far as possible to the actions in the past. [27]

We briefly present the procedure of the sequential analysis of biographical data only to better understand the sequential analysis of the social network. To start with, each biographical datum was interpreted independently of the knowledge that we had from the interview4). To each biographical datum we formulated hypotheses that explain this datum and follow-up hypotheses. We tried to reconstruct the context with which the biographer was confronted and imagine what challenges, conflicts, motivations, opportunities or developments might result from this event. In order to ensure intersubjectivity, both authors conducted the analysis together providing different insights based on personal differences such as gender, place of birth (Germany and Poland), life experience, and methodological perspectives. [28]

The analysis helped us to see with which situations/context the interviewee was confronted at a specific point in time, which possibilities of action existed, and which decisions he/she made. During the process of data analysis, we took into consideration that narratives, including life history narrations, are not accurate reflections of the reality (GERGEN & GERGEN, 2010). In fact, what is narrated about past events is structured by what is remembered and is interpreted within temporal and social context of the current life situation. [29]

The analysis of one biographical datum is followed by the analysis of the next datum, which shows the interpreter the path that was followed by the biographer. The following provides an example of the procedure of the analysis of a biographical datum, drawing on the case of John5). The first datum, with which we begin the analysis, is John's birth:

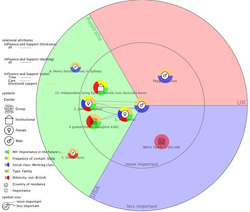

Biographical datum I: John was born in 1930 in Sheffield, an industrial town in Yorkshire, England, as the first child into a working-class family. His father worked in the steel industry; his mother was a housewife. Both parents had many siblings. The whole extended family lived close by and the men of the family were employed in the heavy steel industry, except for John's father's brother, who lived in Melbourne, Australia. [30]

We analyzed first this datum using the procedure of abductive reasoning (PEIRCE, 1980 [1933]). We started by looking at an empirical phenomenon to formulate all possible hypotheses6) explaining this phenomenon (abductive inference). In the next step we deducted from the hypotheses follow-up hypotheses (deductive inference). In this case, we deducted from each hypothesis assumptions about the further and possible development of John's family system and his future life history. We asked ourselves what effects this particular historical context and family constellation would have on John's life course and his decisions. After this, the empirical testing was carried out (in the sense of inductive inference), which means that we tested our hypotheses with the following biographical data in the empirical case (ROSENTHAL, 2018). As an example, we present only two outcomes of the procedure described above:

I.1. John's life is shaped by industrial working culture. All male relatives, including his father, are employed in the steel industry. [31]

On the basis of this abductive hypothesis, we can deduce follow-up hypotheses, how this could affect John's subsequent life (step of deduction). One of the hypotheses is that:

I.1.1. John will be discouraged from continuing in the education system. He will follow the example of his father, leave school after the compulsory years and work in the steel industry. [32]

At this stage, we can also formulate a counter-hypothesis:

I.2. Despite growing up in the industrial town Sheffield in a working-class family, John's parents have aspirations of social mobility. [33]

If this hypothesis is confirmed, the subsequent follow-up hypotheses are possible:

I.2.1. John's parents will try to send him to a better school, outside of the working-class area.

I.2.2. John will go to secondary school instead of doing an apprenticeship like most young men in the neighborhood. [34]

After raising all possible hypotheses and follow-up hypotheses, we turn to the next biographical datum and see how John's life history continues. This is the moment of empirical testing in abductive reasoning (step of induction/inductive inference). Following the biographical data we can see that after the obligatory school years, John leaves school and begins an apprenticeship as a pattern maker. This seems to confirm/verify Hypotheses I.1 and I.1.1: John will be discouraged from continuing his education. Instead, he will follow the example of his father, and leave school after the compulsory years and work in the steel industry. [35]

In the sequential analysis of the social network, we aimed to reconstruct the social network of John at specific points in his life. This procedure allows capturing personal network transformations and analyzing the structuring power that governs those changes. Similarly to the sequential analysis of biographical data, we follow the sequence of the lived life using hypothetical ego-centric maps. This step formulates two types of hypotheses regarding possible transformations in personal network composition:

network hypotheses on future network members/groups—placed on the reconstructed ego-centered network map as possible/expected alter(s);

network hypotheses on increasing/decreasing importance of certain network members in the future—an attribute defining alter(s) in terms of their projected increased importance in the ego's life. [36]

The following example of the sequential analysis of the social network presents one of the hypotheses:

I.3. The family network members belong to the same social class and they do not have outgroup ties with members of other social classes in Sheffield. [37]

We formulated also a follow-up hypothesis:

I.3.1. John will reproduce family roles and class position in the UK, and maintain a homogenous network, limiting his options for upward social mobility. [38]

As well as we can formulate a counter-hypothesis:

I.4. John will have ties with people outside his close family, providing him access to new resources.

I.5. Via his uncle in Melbourne and the connection to Australia, John will have contact with people outside of the British working class in the steel industry in Sheffield. [39]

If we look at the later biographical datum (the uncle from Melbourne visited John's family) and the further biographical datum (uncle in Australia nominated John's father and family for migration, and guaranteed accommodation), Hypothesis I.5 becomes more plausible than the other. Based on sequential/abductive reasoning, we are developing hypotheses about the composition and structure of the social network at that point in time, and how it might develop, e.g., which resources within the network ego/John might mobilize in the future, whether the network stays family-focused and homogeneous or if this might change, e.g., with the migration. Based on these hypotheses we develop several ego-centric network maps. The one from John's childhood looks like this:

Fig. 3: Social network map 1. Please click here for an enlarged version of Fig. 3. [40]

At this point we did not know much about John's relations with the alters. Only the relationship with his father and his influence on John's life was available from the data. The network composition and network members' characteristics presented in Fig. 3 are empirically grounded: derived from the abductive sequential procedure. Based on the first step of the BRNA data analysis it was possible to retrieve meaningful (and influential) network members as well as personal and relational characteristics of the biographer's social network that structure and influence further network transformations. [41]

The second map presents a visualization of network-related hypotheses related to future (possible)/new network members such as new working class/upper/middle class network members and future (possible) changes in importance:

Fig. 4: Social network map 2. Please click here for an enlarged version of Fig. 4. [42]

The importance of actual network members such as John's uncle living in Australia as well as hypothetical new network members (working/upper/middle class network members) may increase (Fig. 4; green color means projected, hypothetical increase in importance of particular alters, network members). The importance of extended family members in the UK on the other hand might decrease, whereas John's nuclear family might remain stable. Due to the relation with the integration broker/the uncle, John's family obtains access to employment and housing, as well as formal and informal networks within the majority society. They live in a British and British-Australian community and have good starting conditions. John, like his parents and uncle, stays in a relatively ethnically homogeneous network of white Australian and especially British migrant population. John's network after the migration presents like this:

Fig. 5: Social network map 3. Please click here for an enlarged version of Fig. 5. [43]

At this stage we are able to introduce relational characteristics of the personal network, as we now know that the uncle financially supported John's family and helped in buying a house. He was also providing the family with information regarding, for example, employment opportunities. We can also claim that the British community provided John with certain opportunities and therefore the "British community" appears in the map. Looking at the network and our follow-up network hypotheses (increased importance of the British community through the uncle's ties), we expected John's network to continue to be homogeneous in terms of ethnicity and social class within the British-Australian working-class migrant community. However, this follow-up-hypothesis was falsified, with the following biographical data, summarized here as: John encountered ethnic diversity after migration, developed networks through frequenting a Catholic dancing evening that served as a meeting point with other migrant groups, made the acquaintance of Alexandra, a Greek woman at the social dances, whom he would later marry and have two children with. Here, we will provide a brief summary of John's family life and his relationships with his son and daughter:

John has a son and a daughter. His son Steven traveled for work and since 1985 has been living in Brisbane. John's daughter Janet quit school, married at the age of 19 and had three children and became a housewife. Here we can see that care is a female task in the family. After the daughter separated from her husband, John and his wife helped her with childcare and housing. Here, we could hypothesize that the daughter at a later stage will feel obligated to reciprocate the care. John's daughter later remarried. She was living in Melbourne until 2000 when her second husband had a back accident and was advised to move to a warmer climate. [44]

In this article we will focus only on four important biographical dates that relate to John's family life and social support network in older age:

Biographical datum X: In 2000 the daughter moved to Perth. [45]

To this biographical datum the following network hypotheses can be formulated:

X.1. John and his wife perceive their daughter as a main carer in the future, and see aged care as an obligation within the family (close family system and responsibility).

X.1.1 They will move to Perth to be with their daughter.

X.1.1. The daughter will not agree.

X.1.2. The daughter will agree, and John and his wife move to Perth. [46]

Counter-hypotheses to X.1. are:

X.2. John has strong ties to friends and stays in Melbourne but loses a main source of informal family support.

X.2.1. Together with Alexandra, John will invest in an aged care home in Melbourne to stay close to their friends.

X.2.2. Non-family ties to friends and former colleagues will gain in importance.

X.2.3. Their son will move back to Melbourne.

X.2.4. The daughter will take care of John from a distance through communication technology and locally organized social networks.

Fig. 6: Social network map 4. Please click here for an enlarged version of Fig. 6. [47]

John's social network when he retired is presented in map 4. It shows possible options for John regarding care arrangements: family (wife, children and grandchildren), friends/extended family members, and an institutional aged care facility. Friends and (extended) family members living in Melbourne as well as an independent living facility/residential aged care home were placed on the map as hypothetical new alters with possible increased importance for John's social support. His son lived relatively close while his daughter decided to relocate to Perth. These hypotheses and visualized network maps on the basis of the hypotheses will at a later stage of the analysis in the III reconstruction of the social network map history then be verified or falsified by looking at the passages of the interview in which the interviewee speaks about the social network and this phase of his life. [48]

3.2.2 Step II: Analysis of presentation of the network map

The analysis of presentation of the network map follows the procedure of the text- and thematic field analysis (TTF) of the case reconstruction (ROSENTHAL, 1995, 2018). In the TTF the interviewees' present perspective, interpretation of their life and their interest in self-presentation are considered, as well as the situational factors of the interview such as the interview context, the interaction with the interviewer, network co-construction during an interview (RYAN, 2021), and the framing of the interview—as influencing the presentation of the life story and network maps by the interviewee (BLUMER, 1973 [1969]). How did the definition of the situation and the interest of self-presentation in front of the interviewer shape the narration? In our case, the researcher's own migration experience and European origin created a feeling of trust and understanding for the interviewee, John, and facilitated storytelling (RYAN, 2015). It is not only important to understand the current perspective of the interviewee. The aim is, according to ROSENTHAL (2004),

"to find out which mechanisms control selection and organization and the temporal and thematic linkage of the text segments. The underlying assumption is that the narrated life story does not consist of a haphazard series of disconnected events; the narrator's autonomous selection of stories to be related is based on a context of meaning—the biographer's overall interpretation" (p.57). [49]

The linked elements of the interview text, the self-presentation and generated ego-centric network map develop a pattern of story production based on "retrospective or narrative explanation of the happening" (POLKINGHORNE, 1995, p.19). In the text-and thematic field analysis and the analysis of the presentation of the network map we try to reconstruct this overall interpretation of the biographer and his/her temporal and social context that structures the process of remembering and self-presentation. [50]

In TTF we analyzed parts of the biography that were not or only briefly mentioned, while others were told at length; which relationships or persons were mentioned and which were not; and which themes were left out. What might be the thematic field (ROSENTHAL, 2018)? Here we especially focused on the analysis of the life story, the interview, particularly on the self-structured presentation of the biography: hence, the transcript of the main narration. In the analysis of presentation of the network map we took a closer look at the second step of BRNA data collection (see Fig. 1), when the interviewee was asked to name people that are most important in his life and place them in the ego-centric network map. During the second step of BRNA data analysis, we asked ourselves which network member (an alter) was put first, and which relationship was not mentioned at all, how John might have intended to present his network in front of the interviewer as well as how the questions and the interview situation might have impacted the shape of ego-centric network generated by John in the BRNA data collection. This analysis of the presentation of the social network map is a relatively novel approach (see e.g., ALTISSIMO, 2016; HERZ et al., 2015; D'ANGELO & RYAN, 2019), as the influence of the interest of self-presentation and the current interpretation of the interviewee on the production of the ego-centric networks is often not analyzed in SNA approaches. The reconstruction of the production of the current social network, resulting from the framing in the interview situation and the interviewee's current network position and interpretation of his or her network, can at a later stage be compared with the reconstructed biographical networks from the life course. In the process of TTF the text is divided into sequences based on the criteria of change of speaker, change of text sort (argumentation, description, narration) and change of content, and then analyzed abductively and sequentially. [51]

When we analyzed the synchronic product of the ego-centric network map, we also had to consider ego/the interviewee's interest of self-presentation and his/her present perspective. Hence it is necessary to bear the results of the TTF, i.e., the thematic field and the interviewee's interest of self-presentation in mind when interpreting the ego-centric network map generated by the interviewee and the presentation of a social network during the interview (external narrative questions in the narrative biographical interview; see Fig. 1). Let us give a brief insight into the procedure of the TTF for better understanding of the analysis of presentation of the network map. Let us consider the first sequence in John's interview. Rosa BRANDHORST conducted the interview with John in the bungalow of the aged care facility. John was eager and very interested to give the interview and showed the interviewer around in the house and showed photos of his children. His wife prepared tea and cookies.

Sequence I: When BRANDHORST asked him to tell his life story, John began with his date and place of birth: "IP: Well, I was born in 1930, in Sheffield in Yorkshire, just had normal schooling. Nothing spectacular. I never got any real high education. Lived between nine and 15 in war years." [52]

Based on this first text sequence, we can develop different hypotheses:

I.1. As John is asked about the biography, he wants to name a few crucial dates in his life in chronological order, the war and his migration are one of them. [53]

One of the formulated follow-up hypotheses is:

I.1.1. John will continue like this and name his wedding, the number of children, his jobs and retirement in report form, hence the main narration will be short. [54]

Another possible hypothesis could be:

I.2. John wants to present his life as a "normal life," and himself as a "normal" representative of his generation of British post-war migrants. [55]

The follow-up hypotheses to this are:

I.2.1. If I.2 is confirmed, John will continue to have a shorter controlled self-structured narration, in report form/description or argumentation.

I.2.2. He will name the "ordinary/normal" stations/trajectory of his life and frame it into the British post-war experience.

I. 2.3. He will avoid telling parts of his life story that are not so normal. [56]

As another counter hypothesis and follow-up hypothesis, we could formulate:

I.3. This only served as an introduction to his life story.

I.3.1. In the next sequence John will focus on the main theme in the form of a longer narration. [57]

Now the next sequence of the interview text is considered. This serves as an empirical test of the formulated hypotheses above. Comparing the hypotheses and follow-up hypotheses above with this sequence, we can see which can be verified and which falsified.

Sequence II: Here John tells a longer sequence in report form on the bombing of Sheffield and the family's decision to move to Australia. [58]

Hypothesis I.2, that John wants to present himself as a "normal representative" of his generation of British post-war migrants, and the follow-up Hypothesis I.2.2 that he will name the "ordinary/normal" stations/trajectory of his life and frame it into the British post-war experience, can be verified. Furthermore, hypothesis I.3, that the first part was just an introduction, and follow-up Hypothesis I 3.1, that he will now move on to the main theme of his life story, is plausible here, but needs to be confirmed in the following sequences of the interview text. As more and more hypotheses are verified and falsified, we can trace a structure in the presentation and the text that leads us to the formulation of the thematic field and the interest of self-presentation of the interviewee, reflecting the current perspective of the interviewee. In John's case we can summarize his interest of self-presentation as follows: John wishes to present himself as an ordinary British post-war migrant. [59]

Having this current perspective of the interviewee in mind, in the second step of BRNA data analysis, analysis of presentation of the network map, we focus on the production of the ego-centric network map by the interviewee during the interview, and the sequence and order of alters placed on the ego-centric map, and we also analyze the framing of the interview situation. In SNA the production process and the interaction between interviewee and interviewer is seldomly examined. In this analytical step, we analyze the presentation/interpretation of this network in the moment of the network production. Here we consider the interaction between interviewee and interviewer, the reaction of the interviewee towards the questions and the interview framing (BLUMER, 1973 [1969]; TÖPFER & BEHRMANN, 2021). Similarly to the TTF, we formulated hypotheses on how John presents and interprets his social network during the interview. Below we present the network map that John produced and a sequence of names placed in the ego-centric network maps:

Fig. 7: Ego-centric network map produced during the interview (numbers indicate the sequence of naming alters). Please click here for an enlarged version of Fig. 7. [60]

The ego-centric map produced during the interview shows that strong ties predominate. The sequence of introducing alters follows the rule that family members who take care of John were mentioned first. John was highly interested in the printed ego-centric network map and eagerly positioned his social ties in the network map. First John mentioned his wife, then his daughter and her children. The hypothesis here would be that with this presentation of his network John wants to prove that there is no need for more formal assistance as his family takes great care of him. First John wanted to put his son a bit more distant in the network map, then hesitated and put him closer in the inner circle. Here social expectation might have been a factor. In the time of the interview John felt his son’s presence and support less, so his son appeared less important, on the other hand he had to respond to the social expectation to find both children equally important.

"IP: and then Steven, as close as Janet? IP: Yeah, as absolutely. Oh absolutely. Yeah. Although he doesn't live here" (Transcript of the interview with John, p.49). [61]

By this stressing by repetition, John seemed to convince himself that his son should be equally important or placed equally close to him in the ego-centric network map. John talked of their visits and emotional support. John's son Steven however appears to be more important in the current network map than the biographical data analysis suggested. According to John's description of relationships and his produced network map, Steven lives on the East Coast but tries to support his parents through ICT and helping them with how to use the computer. John's brother Henry and his cousin Peggy, with whom he grew up, were also mentioned. Furthermore, in John's network presentation, detailed information regarding his grand- and great-grandchildren was revealed. The great-granddaughters and a grandson who live in Perth were presented as especially important. John talked of frequent visits, which he previously had not mentioned. Here different insights into John's support network are revealed; furthermore, situations of reciprocal care and support are narrated.

"Yeah, when he comes back from his stint up at Newman, he'll always come around here. He'll come sometimes and have breakfast with us. And he goes mad because I haven't got enough bread. Well, if you would have told me I would have brought some. And we'll see their children now—at the moment—every Tuesday and the weekend" (Transcript of the interview with John, p.50). [62]

3.2.3 Step III: Reconstruction of the social network history

In the reconstruction of the experienced life history in the biographical case reconstruction (ROSENTHAL 1995, 2004, 2018), that informs the third step of BRNA data analysis, we again focus on the lived life as experienced in the past and at the sequential structure of the lived life as experienced. Here "the biographical significance of individual experiences in the past and above all to the timeline of the life history, its temporal gestalt" (ROSENTHAL, 2004, p.59) is examined. In practice, we return to our analysis of the biographical data and compare the known events/biographical data and our hypotheses with the passages of the interview in which the interviewee speaks about them. Having in mind the knowledge about the interest of the self-presentation obtained in text- and thematic field analysis, we now re-examine the text for traces of past perspectives on the respective events. The hypotheses raised in the first analytical step are falsified or verified by analyzing them together with the interview text passages, or other new hypotheses are found (ROSENTHAL, 2004). During this analytical step we can also select segments of the interview text for microanalysis, to decipher in particular the text's latent structures of meaning (ROSENTHAL, 2004, p.60). In the microanalysis the text is investigated in an abductive and sequential inference line by line, oriented on the method of objective hermeneutics (OEVERMANN, 1983). [63]

In the third step of the BRNA data analysis, the reconstruction of the social network as experienced, we compare our reconstructed social network data and hypothesis and reconstructed ego-centric maps from sequential analysis of the social network with the passages of the interview in which the interviewee speaks about them. Based on the knowledge of the previous analytical steps we are able to draw a more precise picture of the development and structure of the current network. At this point, we will present the network map and our network hypotheses and compare them with the passages of the interview in which the interviewee spoke about them. We will only show the biographical data regarding the move of John and his wife to Perth to follow their daughter. From this biographical datum we formulated social network hypotheses and created a hypothetical network map of John's social network and its significance in this decision in this situation in life:

Fig. 8: Social network map reconstructed in Step I of BRNA data analysis. Please click here for an enlarged version of Fig. 8. [64]

We present a hypothetical composition of John's remembered social network after relocation to Perth on Fig. 8. The network hypothesis regarding the possible increasing importance of John's son as well as his friends and extended family members in Melbourne were not confirmed. Instead, John and his wife followed their daughter to Perth. We formulated the network hypothesis that the importance of the grandchildren in John's life might increase. Let us now have a look at the passages of the interview text in which John spoke about his move to Perth to live with his daughter and compare these with the network map and the network hypotheses formulated in the first step of BRNA data analysis.

"Well, her [daughter's] husband had a very serious accident in Melbourne and didn't work for about seven years. And he was advised to get into a warmer climate. Melbourne is a pretty cold climate sometimes. So moving to Perth for them seemed the right move into a warmer climate [...] So that's when we came over for a holiday to visit them and to visit Alex's sister, because she was here as well. And in fact, it was our second visit to Perth. And so we came over to visit Janet, our daughter, and her husband and her kids. And while we were here, we got this thought that, well, Madam here, she got the idea that we might start living here. Which we did. We went back home. In the next week we—we sat on it for a week. And then I said if we're really serious about this moving to Perth, we've got to do something about it. So we called an estate agent, and three days later we'd sold the house. Just like that [...] just because of our daughter. [...] Steven was in New South Wales. And our daughter had moved over here, so there we were in Melbourne without either of them. [...] So we moved to Perth. And we like the place, anyway. So it wasn't a case of just following her here. We liked it, you know. So that's where we are. And then we see Steven, our son—about once or sometimes if we're lucky twice a year" (Transcript of the interview with John, p.16). [65]

Looking at this text sequence, the hypothesis that the daughter was the primary carer was verified. When John and Alexandra found themselves alone in Melbourne and both children moved away, they chose to move to their daughter. Alternative options were possible for John in Melbourne. However, based on retrospective investigation of network dynamics we observe that John's social support network was governed by the persistence of "traditional family" norms and gender roles within the household, and the continuity of a close family network providing care. The daughter reproduced the traditional gender role as a family carer and engaged in generalized care reciprocity. Furthermore, John and his wife's close ties to their grandchildren seem to be important reasons in their decision of relocating from Melbourne to Perth. The significance of the grandchildren, in fact, provides us with a new reading here: that not only are the ties to the daughter close, but also to the grandchildren who also can provide practical support. John (as we do not have information on his wife's perception over the care arrangements) decided to invest in family care instead of buying into a residential aged care facility, or independent living in an aged care home. This investment strategy failed, however, when John's daughter and her family left the house they had bought together and moved to Osborne Park, a suburb in Perth. John and his wife moved to a bungalow in a residential aged care home close by.

"I've gone through all this sickness period. And then our daughter—she'd lived out at Quinn's Rocks as well. And they then bought into a Baker's Delight bakery. Because our son-in-law had been a baker for years, but he'd gone out of that business. But they saw the opportunity to get into one of these Baker's Delights franchises, which was in Woodlands. [...] And because they were—rather than traveling from Quinn's Rocks to Woodlands every day for the business, they bought a house in Osborne Park. Now we were still happy to stay out at Quinn's Rocks. We were happy out there. But our daughter got very upset about the fact that she wasn't available to us when we needed her for anything. Which we didn't really, but she come out one day and she was terribly upset that she lived so far away from us. So that's what prompted us then to start looking elsewhere. Well, we saw lots of houses in this area. [...] But some of the houses were absolutely—we thought we just can't afford to do that. We can't afford to get less for our house to pay more for another one. I mean, we were retired. We weren't working. So while looking at a house in—I don't know where the hell we were. Somewhere down here. The agent said, 'Are you interested in a retirement village?' And I said, 'Well, I am. But Alex is not particularly happy about it.' She didn't feel that she wanted to move to a retirement village. He said, 'Well, there's a brand-new place over in Osborne Park, that is just opening up now. Would you like to have a look at it?' What else do you do on Sunday afternoon? Who cares? I said, 'Yeah, okay.' So we followed him in his car. We drove in here. Half the place was still empty. There was about 16 or 17 units out of 40 were still empty. Brand new places. And he brought us into this particular one. He took us in others as well, but he brought us into this particular one, and I fell in love with it. Alex wasn't all that excited, but I was. And we sort of did it from then. Our daughter was living in Osborne Park. I was all anxious about it. And it was certainly downsizing from the house we had in Quinn's to this. The size suited us. And I loved the idea of this village. Alex wasn't happy about it. But she went along with it. And now you couldn't get her out of here with a team of horses" (Transcript of the interview with John, p.17f.). [66]

Here, it becomes clear that the daughter moved out of the shared house because of her husband's business opportunities. Simultaneously, by moving out she broke away from her role and defied her parents' expectation of her being the principle carer. The passages when John said that their daughter was so upset: "But our daughter got very upset about the fact that she wasn't available to us when we needed her for anything," "but she came out one day and she was terribly upset that she lived so far away from us," show that the daughter still felt responsible to provide care and had felt guilt when leaving her parents alone in the distant northern suburb. The decision to move to the aged care facility was probably not taken by John and his wife, but was rather a move triggered by their daughter and her guilty conscience. [67]

3.2.4 Step IV: Contrastive comparison of the life history, the social network map and life story

The fourth analytical step of BRNA data analysis, contrastive comparison of the life history, the social network and life story'7), aims to find explanations for the differences between the interviewee's past and present perspectives. It brings together the analysis of the experienced life history (the lived life as experienced) and the narrated life story. "In other words, contrasting helps find the rules for the difference between the narrated and the experienced. The question of which biographical experiences have led to a particular presentation in the present is also pertinent here" (ROSENTHAL, 2004, p.61). Here we try to understand why the interviewees present themselves this way, and how this perspective developed in their life history (HEATH, FULLER & JOHNSTON 2009). Furthermore, we have a look how the interviewees evaluate/interpret their social network today and how this perspective might have developed during their biography and depending on their position and support within the social network. [68]

Regarding the case of John, we could find the following interpretations on how his biographical experiences have led to his current self-presentation: As a migrant John was confronted with the expectation to fit into Australian society. He learned early that focusing on British privilege or on his professional achievements would create envy in the Australian population. Standing out or highlighting one's own professional success is not well-received in Australia. This led to the self-presentation as an ordinary British migrant. In his self-structured narration in the interview John thus underplays the significance of his professional career, in an effort to not stand out. Hence, we contrasted John's experienced life history and the history of his social network, with the current perspective of John on his life embedded in social relationships. By doing so, we managed to reconstruct John's current social network in its genesis. Furthermore, we could provide interpretation of how John's history of social network led to the current presentation of the life history and of the current ego-centric social network produced in the interview. A comparison between the current ego-centric network map that John produced during the interview and the hypothetical, reconstructed ego-centric maps developed in the sequential analysis of the social network shows the importance of close family members (especially the daughter) within in John's ego-centric network produced in the interview, is linked to her role as a primary caregiver after John's retirement, and led to the move of John and his wife into their daughter's house in Perth. Although she was not the primary carer anymore, after John moved to the residential aged care facility, she still occupied a central position in his social network and was placed as a second on the map (see analysis of presentation of the network map). John named especially people in his ego-centric network that were present in his daily life and main providers of emotional and hands-on care in the time of the interview. Our hypothesis regarding increasing importance of family members (especially the daughter) as well as institutional care support was confirmed. [69]

3.2.5 Step V: Development of types and contrastive comparison

The biographical case reconstruction leads to the development of types, in the form of an abstraction of the concrete case study. Based on thorough, in-depth reconstruction of an individual case, based on what John remembered and how it was interpreted as well as on the biographical data, we can formulate a type in a form of a pattern of social network interpretation in biographical narratives. [70]

The case reconstruction aims at theoretical instead of statistical generalization. Generalization from a single case and on the basis of contrastive comparison of several cases is required here (ROSENTHAL, 1995).

"The frequency of occurrence is of absolutely no significance in determining the typical in a case, in the sense used here. The rules that generate it and organize the diversity of its parts are determinant for the type of a case. The effectiveness of these rules is completely independent of how often we find similar systems of rules in social reality." (ROSENTHAL, 2004, pp.61f.). [71]

To formulate a type, we returned to our research question and to the interpretation of the social phenomena. In our research question we looked not at the social network per se, but at the ways older migrants can mobilize local and distant/transnational social support, and their ways of local or transnational aging. We aimed to formulate processual types of changing social relationships and social support embedded in these. The reconstruction of a biography or of a genesis of a social phenomenon makes it possible to construct processual types, that abstract a rule structure of social action based on the reconstructed cases (SCHÜTZ, 1971 [1953], p.24). Hence, we looked at the development of the social network, and of reciprocal support provided during the life course as well as at the presentation of the network map. Furthermore, we abstract this social network and the social support of a single case to a more general type of network change. In the following, we present John's processual social support type embedded in the social networks:

Fig. 9: Processual network type: Pattern of social network remembering and interpretation in biographical narratives. Please click here for an enlarged version of Fig. 9. [72]

John's personal network developed from ethnically homogeneous (all the alters were British) to heterogeneous (diverse network composition). His initial strong ties with the British community in Australia were mediated by the uncle and were initially effective in creating bridging capital (PUTNAM, 2000) and incorporating John into Australian society. John's personal network expanded and became more heterogeneous through marriage with a daughter of Greek migrants. In time, John's network became very dense and was composed mostly of family members. We can see the persistence of traditional family and gender roles within the household, and the continuity and even an increase of a close family-focused network. At the same time, we see that in older age and after retirement the importance of ties with colleagues and friends has decreased while the ties to family increased in importance. [73]

Combining a deductive and formalized, originally quantitative method based usually on statistical generalizations, like formal social network analysis and ego-centric map as a data generation tool, with a reconstructive, interpretative methodology we are entering dangerous terrain. While the BRNA method might encounter criticism from the side of structural network analysis for not adhering to the network analytical concepts, taking subjective meaning (individual agency) before structure, and for not taking cohesion, equivalence and especially interrelation as principles in the analysis a priori. Instead of designing SNA in a way that allows for testing a hypothesis based on standardized data for modeling, our approach is open to discovering biographical aspects and events intertwined with larger social processes that structure relationships, and can be to some degree explored retrospectively. We recognize limitations of the retrospective approach to researching social networks, including cognitive ability to reflect on the past events and various factors influencing the remembered, processed and narrated history. However, John as a biographer tended to point at transformative and critical events structuring his narratives in the making: narratives of themselves and narratives of the past and present relationships8). We might also encounter criticism from the side of biographical theoretical, reconstructive research for introducing a social network perspective into the analysis and developing network maps within the analysis. One might criticize that we introduce a research question or categories in our research, not adhering to the principle of openness in interpretative and especially reconstructive biographical research, or any method in the tradition of objective hermeneutics. We could reply to this criticism, however, with that just as the biographical interview follows a biographical perspective, and certain concepts of gestalt theory, we introduce a social network perspective in this method triangulation. [74]

At the same time this method triangulation might satisfactorily address the criticism of EMIRBAYER and GOODWIN (1994) of structural determinism of the network analysis that

"neglects altogether the potential causal role of actors' beliefs, values, and normative commitments- or, more generally, of the significance of cultural and political discourses in history. It neglects as well those historical configurations of action that shape and transform pregiven social structures in the first place" (p.1425). [75]

In our methodological approach instead, we consider the causal role of actors' beliefs, the significance of discourses in history, and the historical configurations of action that shape and transform social structures. BRNA's special potential further lies in its life historical/processual approach, and the possibility to trace the creation, development and transformation of a social network over a whole life course (without having to make ego-centric network maps with the interviewees over the whole life course) and to analyze how the social network, actors' beliefs and actions, social discourses and structures are intertwined. [76]

In respect to the research project on older migrants' social support networks, this biographical reconstructive social network approach has special potential, as it enables researchers to trace social networks before migration, after migration, and in the process of ageing, and to assess their impact on the access to resources the biographers could mobilize at that time and the decisions the biographers made. Furthermore, we can see how decisions of the biographer are intended to change their social networks, making them more heterogeneous as they leave social groups, or gain access to new ones. We can also see how decisions and actions in the past—like migration—can profoundly transform social networks. To analyze the social support networks of these older migrants, it is not sufficient to look at their synchronic structures, but instead we have to trace them throughout their life course. Only with the knowledge of a developed social structure can we make assumptions on the strength or reliability of certain ties and relationships and can we explain when some alters in the network stop providing support or distance themselves. [77]

This research was jointly supported by the German Research Foundation Grant BR 5645/1-1 (awarded to R. BRANDHORST) and the Polish Ministry of Science and Higher Education "Mobility Plus" fellowship (awarded to L. KRZYZOWSKI).

1) Our understanding of figuration is based on ELIAS (1987) and ELIAS and SCOTSON (1990 [1965]). <back>

2) Detailed explanation of the technique of narrative-generating questions is provided e.g., by ROSENTHAL (2018, pp.139-154). <back>

3) Our understanding of hypothesis is informed by abduction (PEIRCE 1980 [1933]). In contrast to deductive and inductive methods, hypotheses are formed and tested on the basis of a single case. With this abductive reasoning we navigate further directions of processual and retrospective investigation of social networks (BRADY & COLLIER, 2004). <back>

4) We suggest doing the analysis in a group with people who did not conduct the interview or read the interview transcript and hence do not have previous knowledge about the biographical case and its development. <back>

5) Names and biographical data have been anonymized. <back>

6) It would be beyond the scope of this article to present all hypotheses or biographical data. Hence, we focus on crucial moments and changes of social networks within John's life history. <back>

7) This step approximates the step contrastive comparison of the life history and the life story of the biographical case reconstruction (ROSENTHAL 1995, 2004, 2018). <back>

8) Cognitive psychology confirms that compared to life experiences that occur later in life, early life experiences are recalled easier, more accurately, and in a larger number. In other words, older memories are encoded for retrieval easier due to the transformative nature remembered events and "culturally shared representations of the timing of major transitional events" (BERNTSEN & RUBIN, 2004, p.1). <back>

Altissimo, Alice (2016). Combining egocentric network maps and narratives: An applied analysis of qualitative network map interviews. Sociological Research Online, 21(12), 152-164, https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/full/10.5153/sro.3847 [Accessed: June 15, 2019].

Antonucci, Toni; Ajrouch, Kristine & Birditt, Kira (2014). The convoy model: Explaining social relations from a multidisciplinary perspective. The Gerontologist, 54(1), 82-92.

Armitage, Neil (2016). The biographical network method. Sociological Research Online, 21(2), 1-15, https://www.socresonline.org.uk/21/2/16.html [Accessed: September 21, 2021].

Bernardi, Laura (2011). A mixed-methods social networks study design for research on transnational families. Journal of Marriage and Family, 73(8), 788-803.

Berntsen, Dorthe & Rubin, David (2004). Cultural life scripts structure recall from autobiographical memory. Memory and Cognition, 32(5), 427-442.

Bidart, Claire & Lavenu, Daniel (2005). Evolutions of personal networks and life events. Social Networks, 27(4), 359-376.

Bilecen, Başak & Amelina, Anna (2017). Egozentrierte Netzwerkanalyse in der Biographieforschung: Methodologische Potenziale und empirische Veranschaulichung. In Helma Lutz, Martina Schiebel & Elisabeth Tuider (Eds.), Handbuch Biographieforschung, (pp.597-610). Wiesbaden: Springer VS.

Birditt, Kira & Antonucci, Toni (2007). Relationship quality profiles and well-being among married adults. Journal of Family Psychology, 21(4), 595-604.

Blumer, Herbert (1973 [1969]). Der methodologische Standort des Symbolischen Interaktionismus. In Arbeitsgruppe Bielefelder Soziologen (Hrsg.), Symbolischer Interaktionismus und Ethnomethodologie. Reader S.80-146). Reinbek: Rowohlt.

Bott, Elizabeth (1957). Family and social network. London: Tavistock.

Brady, E. Henry & Collier, David (Eds.) (2004). Rethinking social inquiry: Diverse tools, shared standards. Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield.

Brandhorst, Rosa M. (2015). Migration und transnationale Familien im sozialen Wandel Kubas. Eine biographische und ethnographische Studie. Wiesbaden: Springer VS.

Crossley, Nick (2010). The social world of the network. Combining qualitative and quantitative elements in social network analysis. Sociologica, 1, 1-34.

Crossley, Nick & Gemma Edwards (2016). Cases, mechanisms and the real: The theory and methodology of mixed-method social network analysis. Sociological Research Online, 21(2), 217-285, https://www.socresonline.org.uk/21/2/13.html [Accessed: July 15, 2019].

D'Angelo, Alessio & Ryan, Louise (2019). The presentation of the networked self: Ethnics and epistemology in social network analysis. Social Networks, 67, 20-28.

D'Angelo, Alessio; Ryan, Louise, & Tubaro, Paola (2016). Visualisation in mixed-methods research on social networks. Sociological Research Online, 21(2), 15, http://www.socresonline.org.uk/21/2/15.html [Accessed: July 10, 2021].

Diaz-Bone, Rainer (2007). Gibt es eine qualitative Netzwerkanalyse?. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung / Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 8(1), Art. 28, https://doi.org/10.17169/fqs-8.1.224 [Accessed: December 14, 2019].

Elias, Norbert (1987). Die Gesellschaft der Individuen. Frankfurt/M.: Suhrkamp.

Elias, Norbert & Scotson, John L. (1990 [1965]). Etablierte und Außenseiter. Frankfurt/M.: Suhrkamp.

Emirbayer, Mustafa (1997). Manifesto for a relational sociology. American Journal of Sociology, 103(2), 281-317.

Emirbayer, Mustafa & Jeff Goodwin (1994). Network analysis, culture, and the problem of agency. American Journal of Sociology, 99(6), 1411-1454.