Volume 23, No. 1, Art. 3 – January 2022

Co-Production of Knowledge and Dialogue: A Reflective Analysis of the Space Between Academic and Lay Co-Researchers in the Early Stages of the Research Process

Marilena von Köppen, Susanne Kümpers & Daphne Hahn

Abstract: Co-production of knowledge, where academic and lay researchers work as partners, is a central characteristic of participatory action research. It requires the participants to engage in a transformative dialogue. But how can co-production of knowledge function in the care home setting? We addressed this question in a specific interaction between academic and lay researchers in an action research project sited in a nursing home in Germany. Drawing on Paulo FREIRE and Mikhail BAKHTIN, we developed seven dialogue criteria and applied them as sensitizing concepts. In order to further a critical analysis, in our data analysis we combined three methodical approaches: 1. analytical autoethnography, 2. sequential analysis in the tradition of objective hermeneutics, and 3. reflection with critical friends. This innovative triangulation allowed for rich and complex interpretations. We found that all seven dialogue criteria are important to co-production of knowledge and should direct the process between academic and lay researchers.

Key words: co-production of knowledge; dialogue; research relations; lay co-researchers; action research; asymmetry; analytical autoethnography; sequential analysis; objective hermeneutics; critical friends

Table of Contents

1. Introduction

1.1 Social constructionism and the space between academic and lay co-researchers

1.2 Nursing homes: Not an easy setting

1.3 Project PaStA

1.4 Research interest

2. Theoretical Background

2.1 Paulo FREIRE

2.2 Mikhail BAKHTIN

2.3 Interim conclusion

3. Materials and Methods

3.1 Data

3.2 Analytical methods

4. Results

4.1 Segment 1

4.2 Segment 2

4.3 Segment 3

4.4 Segment 4

4.5 Segment 5

5. Discussion

5.1 Dialogue criterion 1: Orientation on shared search for knowledge

5.2 Dialogue criterion 2: Promotion of polyphony and avoidance of monologues

5.3 Dialogue criterion 3: Horizontal relationships in a space without hierarchical structures

5.4 Dialogue criterion 4: Dialogue historically and culturally sited

5.5 Dialogue criterion 5: Generative themes that are relevant for the dialogue partners

5.6 Dialogue criterion 6: Seeking to overcome limit-situations by shifting the bounds of the conceivable and feasible

5.7 Dialogue criterion 7: An attitude that promotes a reflective, playful and curious approach

Co-production of knowledge, where academic and lay researchers work as partners, is a central characteristic of participatory research (BORG, KARLSSON, KIM & McCORMACK, 2012). Action researchers also seek to avoid treating the subjects of research as passive objects and information sources, recognising instead their right to involvement in the process (COLEMAN, 2015). Action research is "with, rather than on people" (HERON & REASON, 2006 [2001], p.144). Co-production of knowledge involves more than integrating different experiences and opinions; it means—centrally—working together with others

"who have similar concerns and interests to yourself, in order to: (1) understand your world, make sense of your life and develop new and creative ways of looking at things; and (2) learn how to act to change ways of looking at things you may want to change and find out how to do things better" (ibid.). [1]

This "dual objective" (VON UNGER, 2014, p.46)1)—of understanding and action—is the yardstick by which participatory action research is to be judged. That still leaves us with the question of how co-production of knowledge is to be realised in research practice. [2]

1.1 Social constructionism and the space between academic and lay co-researchers

We begin by considering social constructionism as a meta-theory of relationality (GERGEN & GERGEN, 2015; HERSTED, NESS & FRIMANN, 2020a; McNAMEE & HOSKING, 2012). Social constructionism holds that "what we take to be the truth about the world importantly depends on the social relationships of which we are a part" (GERGEN, 2015, p.3). In other words, truth is not external and objective, a "thing" to be sought and found, but an (inter-)personal construct that is always historically and culturally sited and thus never neutral. "In effect, neither of us can make meaning alone; it is in the coordination of our actions—or co-action—that meaning is born, sustained, or dies" (p.123). Such an understanding of knowledge has consequences. Taking the relationality of truth and knowledge seriously requires (Western) scientists to abandon two deeply entrenched traditions:

"The first is the tradition of the individual 'knower,' the rational, self-directing, morally centered and knowledgeable agent of action. Within the social constructionist perspective, we find that it is not the individual mind in which knowledge, reason, emotion and morality reside, but rather in human relationships. The social constructionist action researcher shifts the attention from the individual actor to coordinated relationships (McNamee 2010). The second is that the social constructionist researcher's focus is not a concern about uncovering truth or reality as it is, but an attempt to understand how people make sense of their everyday social world. Constructionist research is therefore concerned with seeking explanations about how social experience is created and given meaning (Turnbull 2002)" (HERSTED, NESS & FRIMANN, 2020b, pp.7-8). [3]

It follows that the focus of research must be on the space between the participants, rather than the academic researcher producing knowledge in isolation. As GERGEN (2015) put it: "The magic lies between" (p.105). The point is to construct worlds together rather than separately. This requires the participants to engage in a transformative dialogue "specifically aimed at bringing about a new and more promising future" (p.121). What that means concretely for research practice is the question we address in this contribution. [4]

1.2 Nursing homes: Not an easy setting

The setting in which our research took place was residential care for older people. In 2019, 4.13 million people in Germany required care, 19.8 percent of whom lived in residential facilities (STATISTISCHES BUNDESAMT, 2020, p.19). In projections for Germany in 2030 it has been suggested that the proportion of the population who spend their final years in residential care will continue to grow (SCHWINGER, KLAUBER & TSIASIOTI, 2020, p.8). Unlike in Scandinavia—where Denmark, for example, stopped construction of new care homes in 1987 to encourage the development of new forms of care (STULA, 2012, p.14)—residential homes for older people will continue to play an important role in Germany for the foreseeable future. [5]

The situation is naturally complex and can only be briefly outlined in the following. Residential composition is a central characteristic. The populations of residential institutions tend to be older and less healthy than those cared for in their own home (STATISTISCHES BUNDESAMT, 2020, p.11). One reason for this is that older people often want to remain in their own home as long as possible (BUNDESMINISTERIUM FÜR FAMILIE, SENIOREN, FRAUEN UND JUGEND, 2017, pp.227-228). It is thought that the mean length of stay in residential institutions for older people has fallen, although the data are inadequate (PATTLOCH, 2014; WAHL & SCHNEEKLOTH, 2007; WISSENSCHAFTLICHE DIENSTE, 2011). This trend obviously brings with it changes in care-related and psychosocial needs and relationships. HEIMERL and SCHUCHTER (2013) concluded:

"Care homes are no longer 'places to live' where sprightly older people spend their lives when the housework gets too much. Instead, have become 'places to die' where ever more residents are already seriously ill and in need of care when they move in. The length of stay has become increasingly short" (p.17). [6]

A second aspect relates to the political and societal context. The discourse is characterised by concerns that demographic ageing will be associated with a cost explosion. The principle of prioritising outpatient care2) was anchored from the outset in the German care insurance system because long-term residential care was regarded as (too) expensive. Growing pressure on residential institutions to obey the rules of economic efficiency often leads to underfunding and exacerbates a structural staffing crisis characterised by shortages of nurses and other qualified staff such as care assistants. Staffing shortages have tangible effects: residents, staff and family members all complain that time is lacking. This complaint functions as a placeholder for shortages of staff, funding and time that have significant impacts on the quality of life and health of all those who live and work in these residential facilities. [7]

Challenges, finally, are also associated with the institutional arrangements that govern residential care homes. GOFFMAN (2017 [1961], p.2) coined the term "total institution" to describe institutions that monitor and control all the activities of their residents: work, sleep, meals, recreation and so on. Prisons and psychiatric institutions are typical examples. The problem with total institutions is that it is impossible to escape their rules. A strongly asymmetrical power imbalance between inmate and staff leaves little room for freedom. Today's care homes are not, it must be said, as a rule typical total institutions. In recent years great effort has been put into opening them up. Proposals for a fourth and fifth generation of care homes showed how residential care can be opened and integrated into residential quarters (MICHELL-AULI & SOWINSKI, 2013). Nevertheless, even today, care homes still exhibit traits of the total institution. Many residents spend their entire day there. Interaction, activities, mealtimes and sleeping hours are often regimented and outside the influence of those they apply to. [8]

The empirical basis of our investigation is the participatory research project "Partizipation in der stationären Altenpflege" (PaStA) [Participation in Care Homes], which we conducted in Fulda, Germany in two nursing homes after the relevant ethics committee provided approval.

|

Title |

PaStA Participation in care homes. Enhancing the quality of life through participation in shaping daily life in care homes: development and implementation of participatory group processes with residents, family care providers and volunteers |

|

Academic team |

Project leaders: Prof. Dr. Susanne KÜMPERS; Prof. Dr. Daphne HAHN Researcher: Marilena VON KÖPPEN University of Applied Sciences Fulda, Germany |

|

Cooperation partners |

Two nursing homes in Fulda with different operators, residential and care concepts, size and location. |

|

Funding |

Bundesministerium für Bildung und Forschung [German Ministry for Education and Research] |

|

Duration |

January 2017 – December 2020 |

Table 1: Project PaStA [9]

Standing in the tradition of action research, we investigated possibilities for care home residents to participate in shaping their everyday lives. We sought to initiate group processes that promote participation and co-determination in ways that contribute to well-being and quality of life (and thus also to health). In the present contribution we focus on the group process conducted with residents in one of the two investigated care homes. This was a comparatively small facility with 62 places, operated by a non-profit organisation at a location on the outskirts of the city. Few of the residents were able to leave the building unassisted, for example to take the bus into town. After making initial contact with the care home's management, the first author spent several months visiting regularly and familiarising herself with its structures and routines through activating interviews. In consultation with the home's management the academic team (comprising the project leaders and the academic researcher) decided to establish a project group with interested residents in order to research and strengthen the possibilities of participation. Obstacles associated with the funding mechanisms and the nursing home structures precluded involving the nursing home residents in the earliest stages of research design. In that sense this was a participatory project initiated by the academic side. [10]

The residents were informed about the project group by care assistants and chose whether to participate. Participation fluctuated over the course of the project; a core group of five residents attended consistently. The participating residents were all female, aged between 80 and 95 years, with cognitive, psychological and physical restrictions (mild dementia, depression, mobility). The project group comprised the participating residents, the head of care assistants and the first author. The group held meetings over the course of the subsequent seven months, during which a participatory project selected by the residents themselves was realised. The group grew herbs on the balconies off the communal living and eating spaces, which residents were free to use to season their meals. A special role was played by the head of the care assistants, who functioned as gatekeeper by speaking with residents about the herb boxes and helping them to participate. [11]

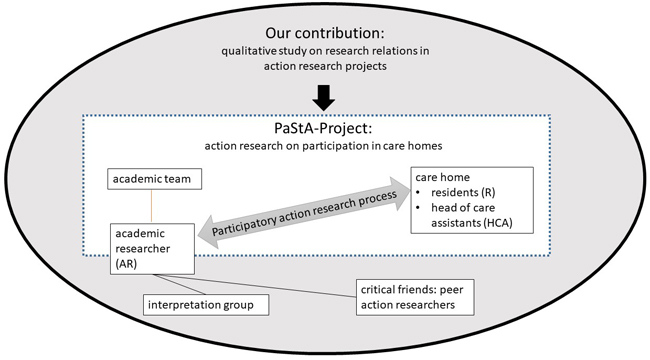

We set out to explore the challenges involved in initiating and sustaining a transformative dialogue in the setting of a residential care home. Our aim was to study how co-production of knowledge can function in a care home setting. This involved developing criteria for the dialogue process and investigating the influence of the specific institutional context. To analyse the co-production of knowledge we employed data documenting the research process from the PaStA project. As Figure 1 illustrates, our research concerned a meta-level in relation to the project, with implications for the research design. While in PaStA, we employed a participatory research design and sought to maximise the residents' active involvement in all stages of the research process, in our secondary analysis we used methods based in the qualitative paradigm. Here co-production was the object of the research but not the research method: we conducted a qualitative study about a participatory project.

Figure 1: The present contribution in relation to PaStA [12]

Rather than examining the entirety of the research process and describing the development of the project group over its seven months of activity, we elaborated the concrete interaction practice of the participants in the context of a specific excerpt from a single discussion. This micro-analytical perspective allowed us to dissect in detail what occurred in the space between the academic researcher and the residents. We focussed in particular on the beginning of the research process because the initial interactions and negotiations have a crucial influence on the research relationships and the process as a whole. Examining an excerpt at the micro-level generated insights for deeper critical reflection. Our goal was thus not to present an especially successful example of co-production of knowledge, but to enter a process of exploration together with you, our reader. [13]

Hence, in Section 2 we introduce the concept of dialogue, which is central to both action research and social constructionism, and consider what challenges they present and what insights they offer for successful co-production. In Section 3 we describe the data and the analytical methods we used to comprehend the diversity of the described situations. We present the findings and associated insights in Section 4. Our objective is to demonstrate the difficulties that arose, especially at the beginning of the research process, and show how we responded to them. We conclude with a critical discussion of the benefits and limits of co-production of knowledge in the care home setting in Section 5. [14]

The object of our research interest was the "space between" the academic researcher and the residents. We wanted to understand what happened there, and how co-production of knowledge actually occurred. Because, as social constructionism implies, the epistemological processes do not occur within the individual but in a relationship constituted by dialogue, we had to configure our analytical tools accordingly. First, we had to identify a suitable starting point for analysing the space between and what happens there. [15]

We began with Brazilian popular educator and philosopher Paulo FREIRE, whose ideas and practice have hugely influenced participatory research. DARDER (referring to SANTOS, 2014) described him as an "early epistemologist of the South" (DARDER, 2018, n.p.). In his "Pedagogy of the Oppressed" (1996 [1970]), FREIRE criticised the legacy of Portuguese colonialism and brutal repression of the poor and indigenous in 1960s Brazil. FREIRE's pedagogy was universal and intimately bound up with social and political revolution; the teacher was always also an activist. His goal therefore was "to intentionally shift the focus away from a dehumanizing epistemology of knowledge construction toward a liberating and humanizing one" (DARDER, 2018, n.p.). The development of critical consciousness, which FREIRE called conscientisation, is a central concept. Conscientisation does not occur automatically, but requires "critical pedagogical interactions that nurture the dialectical relationship of human beings with the world" (DARDER, 2018, n.p.). [16]

Dialogue, which FREIRE saw as "a requirement of human nature" (2000 [1997], p.92), is the foundation of critical pedagogical interactions. He employed the term in an emancipatory sense: dialogue is the basis for empowerment, for facilitating a transformation of the historical and social situation. This is rooted in an understanding that all human beings, even those who are repressed and disadvantaged, are capable of critically reflecting their condition in dialogue. This even applies to those who are apparently trapped in naive or fatalistic ideas. Dialogue requires a horizontal relationship between the dialogue partners. In a radical departure from the conventional model where teachers (or researchers) regard their knowledge as their own property, which they generously share with their students, FREIRE's dialogue involved the two sides meeting as equals and entering into a process of mutual inquiry (SHOR & FREIRE, 1987). For this to occur, the dialogue must be characterised by love, humility, faith, mutual trust, hope and critical thinking (FREIRE, 1996 [1970]). [17]

The process of conscientisation begins with learning how people understand their reality. "The starting point for organizing the program content of education or political action must be the present, existential, concrete situation, reflecting the aspirations of the people" (FREIRE, 1996 [1970], p.76). FREIRE used in this context the concept of "generative themes", which comprise the "issues, ideas, values, concepts, and hopes that characterize an epoch as well as obstacles which impede people's fulfillment" (MORRIS, 2008, p.63). The question of which concrete themes are relevant within a project is not for the researcher alone to determine, but must be the outcome of cooperation between the researcher and the people who would normally be merely objects of study, but now become co-investigators (FREIRE, 1996 [1970], p.87). This presupposes a free, open space:

"Freire explains ... that generative themes cannot emerge in a context of alienation, where human beings are divorced from reality. This is so, given that the formation of generative themes requires the space and place for freely naming the limit-situation and considering the collective impact of our perceptions and the realities of life" (DARDER, 2018, n.p.). [18]

The non-existence of generative themes is impossible: "The fact that individuals in a certain area do not perceive a generative theme, or perceive it in a distorted way, may only reveal a limit-situation of oppression in which people are still submerged" (FREIRE, 1996 [1970], p.103). These "limit-situations" describe the obstacles that constrain people's freedom and lead to hopelessness and passivity. They can only be overcome through "limit-acts", "through action upon the concrete, historical reality in which limit-situations historically are found. As reality is transformed and these situations are superseded, new ones will appear, which in turn will evoke new limit-acts" (pp.80-81). [19]

Beyond the bounds that create limit-situations lies what FREIRE called "untested feasibility" (p.83). These are the unverified but conceivable possibilities that arise as soon as people understand the limit-situations as "the frontier between being and being more human, rather than the frontier between being and nothingness" (p.83). In that moment "they begin to direct their increasingly critical actions towards achieving the untested feasibility implicit in that perception" (ibid.). [20]

Our second central source of inspiration on the conditions of co-production of knowledge was the Russian philosopher Mikhail BAKHTIN. He too believed that "life is by its very nature dialogic" (1984 [1963], p.293). This applies both at the ontological level (human existence is constituted through dialogue) and at the ethical level (human life should be dialogical). But what characterises dialogue? Put in the simplest terms, a dialogue comprises an utterance, a response and the relationship between the two. It is the relationship that generates meaning (HOLQUIST, 2002, p.38) and the relationship that makes knowledge possible. "Truth is not born nor is it to be found inside the head of an individual person, it is born between people collectively searching for truth, in the process of their dialogic interaction" (BAKHTIN, 1984 [1963], p.110). But that does not mean that the objective is to fuse the voices of the various communication partners into one. Quite the contrary: their difference is essential for dialogue. Otherwise it would only be a monologue that reduces the other to an object by negating its self (RULE, 2011, p.929). BAKHTIN consequently saw dialogue as the "single adequate form for verbally expressing authentic human life" (1984 [1963], p.293). [21]

In the sphere of research, too, the point is not for researchers to merge into their field of research and adopt its culture and opinions as their own. BAKHTIN was clear that the researchers must preserve their "outsideness": "our goal should be the dialogic one of 'creative understanding'" (MORSON & EMERSON, 1990, p.54):

"Creative understanding does not renounce itself, its own place in time, its own culture; and it forgets nothing. In order to understand, it is immensely important for the person who understands to be located outside the object of his or her creative understanding—in time, in space, in culture. For one cannot even really see one's own exterior and comprehend it as a whole, and no mirrors or photographs can help; our real exterior can be seen and understood only by other people, because they are located outside us in space and because they are others" (BAKHTIN, 2010 [1979], p.7). [22]

The dialogue is characterised by endlessness. BAKHTIN (1984 [1963], p.53) spoke of "unfinalizability": the world is open-ended and future development is always possible (MORSON & EMERSON, 1990, p.36). This idea also surfaces in the concept of "carnival". "'Carnival' is Bakhtin's term for a bewildering constellation of rituals, games, symbols, and various carnal excesses that constitute an alternative 'social space' of freedom, abundance, and equality, expressing a utopian promise of plenitude and redemption" (GARDINER, 1993, p.767). The carnivalesque space is thus a realm of playful experimentation with new kinds of human relationship, with counter-models to the omnipotent socio-hierarchical relationships of non-carnival life (BAKHTIN, 1984 [1963], p.123). In carnival, hierarchies are turned on their head. [23]

To what extent did the ideas of FREIRE and BAKHTIN help us in our search for a better understanding of the co-production of knowledge? What they share in common is the significance they ascribe to dialogue. They both argue, if from different perspectives, that the principle of dialogue is inherent to human nature and vital for the generation of knowledge. Clearly "dialogue" in this sense is not referring to any arbitrary type of interaction, but describes a very complex and specific matter. If we attempt to bring the two theories together, a successful dialogue can be described as follows: Dialogue is 1. a shared search for knowledge, of which no dialogue partner is in sole possession. Instead, dialogue seeks to promote (or assumes) 2. polyphony; otherwise, it is a monologue. The conditions for dialogue are 3. horizontal relationships and a space characterised by openness and the absence of hierarchical structures. Dialogues are 4. always historically and culturally sited, so their context cannot be ignored. The starting point of dialogue 5. lies in generative themes, in the topics that truly move people at a particular historical juncture. It seeks 6. to overcome limit-situations, in the sense of the limits of the conceivable created by asymmetrical power relationships. Its success demands that the attitude of the dialogue partners 7. is characterised by love, humility, faith, mutual trust, hope and critical thinking and promotes a reflective, playful and curious approach. Employing these seven dialogue criteria as sensitizing concepts, we then examined a concrete research interaction and investigated the extent to which it represented a dialogue (and thus co-production of knowledge) under the criteria outlined above. [24]

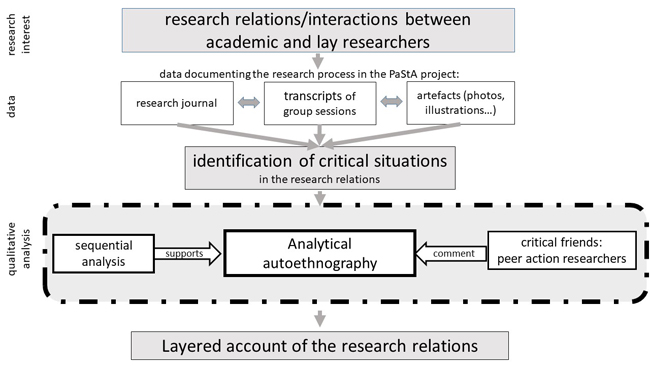

Methodologically, we proceeded by identifying a critical situation in the research relations (Figure 2). The interactions between academic researcher and the residents are documented in various forms. The principal source is transcripts of the group meetings, augmented by field notes, research journal entries and artefacts such as photographs and posters. Participants gave informed consent (written and verbal) to data collection and analysis and the relevant ethic committee (University of Applied Sciences Fulda, Germany) provided approval. As critical situation, we selected the first minutes at the beginning of the first group meeting. These first minutes were so important because it is here that the academic researcher and the co-researchers met for the first time and began to negotiate their (power) relationship. For purposes of analysis we divided the sequence into five segments to enable analysis at the micro-level (and to enable the reader to follow the interaction blow by blow). In the next step, we analysed the segments using analytic autoethnography. Sequential analysis and reflections by critical friends supported this step. We then integrated the findings (still at segment level) by generating thematic clusters. On that basis we were then able to formulate hypotheses and interpretations concerning the interactions and finally examine how the interpretations developed and changed from segment to segment. This enabled us to reconstruct and analyse the ongoing interaction and critically reflect on it in relation to the concept of dialogue.

Figure 2: Data analysis [25]

We began with the transcript of the investigated sequence from the first group meeting that comprised five residents (R), a care assistant (CA) and the academic researcher (AR). We divided the transcript into five segments for purposes of analysis. [26]

Segment 1

After introducing herself as a member of the local university of applied sciences and very briefly outlining the research project, the academic researcher (AR) opened the session with a fictitious story:

AR: "I would like to read you a little story. It's called 'Frau Meyer wakes up in a care home'. Frau Meyer slowly wakes up. It all feels unfamiliar: the bed, the duvet, the light. For a moment Frau Meyer is unsettled. But then she remembers, she is in a care home. The first night in new surroundings. She arrived yesterday, direct from the rehabilitation hospital where she spent four weeks learning to walk again after a fall and a hip operation. Her children advised her to make the move because the building where she lived had no lift and she had been rather lonely lately. Will that change here? What should she expect here? Will she be happy? Frau Meyer thinks for a moment: at home she would make herself a cup of coffee, sit at the little table and look out of the window. She feels wistful. But then she sighs, slowly pulls back the bedcover and starts the day ..." [27]

Segment 2

At first, the story did not prompt much response. After a couple of minutes the academic researcher asked a question:

AR: "What would you have wished for back then when you ... if you ... yourself, if you can't remember the day exactly, but which you so to speak ... what would you have wished for, that here, that should happen here or how it should be?" [28]

Segment 3

R2 responded directly:

R2: "Normal."

AR: "Normal means?"

R2: "Just how it is, yeah, that is ... " [29]

Segment 4

After a brief pause R2 explained (continuing from Segment 3):

R2: "... one gets up, drinks a coffee and does something or other."

R1: "Eats a crusty roll. That's how to start the day, that always tastes good. Well it's true isn't it!"

AR: "Yeah."

R1: "Yes, yes, well I'm always really looking forward to it."

R2: "We don't get that at home, do we, we have to go and fetch them ourselves." [laughs] [30]

Segment 5

R1 spoke again (continuing from Segment 4):

R1: "You get everything put in front of you, well that's super isn't it?"

AR: "Okay, okay."

R1: "I think so too, mmh, yeah." [31]

So how should we analyse this brief excerpt and explore its relevance to our research question? Social constructionism stresses the importance of allowing the various facets of encounter and relation found in the data to coexist in the analysis even if they are contradictory: "Instead of simplifying or reducing phenomena, social constructionist approaches tend to unfold multiplicity and complexity and give space for uncertainty and dissensus rather than seeking consensus" (HERSTED et al., 2020b, p.13). We therefore allowed the idea of polyphony to guide our analysis. As outlined above, the term originated from BAKHTIN (1984 [1963]). It reflects the existence of different kinds of knowledge and thus of more than one "correct" path to knowledge (HERSTED et al., 2020b, pp.8-9). For the current article, we therefore selected three different methods of analysis, each of which was associated with different assumptions about the generation of knowledge. Our goal was to use these diverging perspectives on the interaction processes to obtain a wide-ranging and complex picture of the space between the academic researcher and the residents. [32]

Our starting point was the utterances of the dialogue partners. As GERGEN wrote: "Our lives are built around shared ways of talking" (2015, p.72). Language is not simply a "mapping device" representing and describing reality; language and its usage are "constitutive" of reality (HERSTED et al., 2020b, pp.9-10): "Traditions of language use construct what we take to be the real world" (GERGEN & GERGEN, 2015, p.402). It follows that "[s]cientific theories, explanations and descriptions of the world are not so much dependent on the world in itself as on discursive conventions" (ibid.). [33]

3.2.1 Analytic autoethnography

An autoethnographic account by the academic researcher formed the heart of our analysis. In the autoethnographic approach researchers—including their experiences and emotional involvement (PITARD, 2017)—become the object of research (ELLIS, ADAMS & BOCHNER, 2011; HOLMAN JONES, ADAMS & ELLIS, 2016; TLALE & ROMM, 2019). The idea is to speak

"reflexively and dialogically about and from within relationships—whether, for example, from within the different voices of the researcher's inner dialogue, between the researcher(s) and other texts, between the researcher and others in outer dialogue, between writers and readers of research writing" (SIMON, 2013, §33). [34]

We chose this approach to illuminate the interactions between the academic researcher and the residents from a personal, subjective perspective. The principal source of data were the researcher's field journal, including e-mails, meeting notes and photographs. This gave insights into her subjective thoughts and experiences. In order to elucidate the significance of the scattered fragments, she processed them into a personal narrative. Building on the analytic autoethnography described by ANDERSON (2006) and ANDERSON and GLASS-COFFIN (2016 [2013]) we integrated theoretical and research-based observations:

"The final characteristic of analytic autoethnography is its commitment to an analytic agenda. The purpose of analytic ethnography is not simply to document personal experience, to provide an 'insider's perspective,' or to evoke emotional resonance with the reader. Rather, the defining characteristic of analytic social science is to use empirical data to gain insight into some broader set of social phenomena than those provided by the data themselves. This data-transcending goal has been a central warrant for traditional social science research" (ANDERSON, 2006, pp.386-387). [35]

In order to deepen the analysis and derive a dense description, we augmented the autoethnographic approach with two further analytical strategies: sequential analysis and critical reflection with peer action researchers. We employed sequential analysis to dissect the specific language game (WITTGENSTEIN, 2009 [1953]; see also GERGEN, 2015) between the academic researcher and the residents. Sequential analysis plays a role in a number of research styles, first and foremost (at least for the German context) in OEVERMANN's objective hermeneutics (2000; see also WERNET, 2014). The central idea here is that texts are interpreted sequentially, statement by statement. The tradition of objective hermeneutics thus builds on the idea that social action is not constituted by isolated acts, but instead every act refers to the past and opens up new possibilities for the future. In other words, there are sequential relationships between acts. That does not necessarily imply causality: one act does not determine the next, but merely defines the space within which it may occur. The approach of sequential analysis is therefore to consider what plausible alternatives would have been conceivable at a particular point and then to examine which of them was actually chosen. The decisive aspect here is the choice itself rather than the subjective intentions of the actors. In objective hermeneutics the reconstruction of the act thus claims to uncover the latent structures of meaning. The process of sequential analysis of interactions identifies particular selection patterns which can then be used to construct a case structure (SAMMET & ERHARD, 2018, pp.32-33). In the present contribution, we analysed data from the audio recording of the first group meeting with residents. The recording was transcribed according to ROSENTHAL's transcription rules (2015, p.100) and analysed collaboratively in an interpretation group. This served the quality criterion of intersubjectivity and enhanced the validity of the interpretation, as well as serving to help the academic researcher to distance herself from the material. [36]

3.2.3 Reflection with critical friends

Our third method harnessed the great potential inherent to reflection, in this case in interaction with other action researchers. The academic researcher shared her thoughts and findings with the academic team and a group of external peer action researchers, who functioned as critical friends offering new and different perspectives on the material. The objective was not so much to assess or judge the research process but to encourage collective learning of the kind discussed under the action learning paradigm (McGILL & BROCKBANK, 2004). Experiences gathered by the critical friends in their own projects, where they have equally encountered the problem of shaping research relationships, also flowed into the discussion making it possible to contextualise the PaStA project within a larger framework. Various methods and techniques of reflection were employed to stimulate the process of inquiry, as described by SCHÖN (1983, "reflective practitioner") and THOMPSON and THOMPSON (2018, "critically reflective practitioner"). We also made the findings gained using the first two methods into an object of reflection themselves, creating what one could call a double-loop reflection. [37]

Our application of the three methods generated a multitude of observations and interpretations, some of which confirm each other, while others contradict or deepen. The next question was how to tie these findings together. The objective of a social constructionist approach is not homogeneity; we were not seeking to fit all the findings into a single logical picture. Our interest was depth of interpretation. Our hope was that the three methods in combination enable a deeper and more complex reflection on the research interactions than would be possible from a single perspective. Our description of the results followed the division into segments outlined above. We laid out, step by step, the hypotheses and interpretations developed in relation to the interactive space between the academic researcher and the residents. [38]

The interaction we intended to study began with the academic researcher's announcement that she meant to read a story. In her research journal, she noted what she hoped this would achieve:

"The idea is that they all probably remember their first night in the new surroundings. And that they all had wishes, fears and expectations. My assumption is that after I have read the story it will be relatively easy to start a discussion that interests them. And then we can say that the point of the group is to talk about their experiences together and think about what could be done better." [39]

In other words, the academic researcher hoped that the story would help to start a discussion. She wanted to start the relationship with a topic that was interesting for the residents and which she believed to be generative (see Dialogue criterion 5 from above). At the same time, she was seeking to give the residents an impression of the possible form and content of the meetings. Thus, the academic researcher's objective was to initiate a joint search for knowledge (Dialogue criterion 1). [40]

Using sequential analysis we could now identify latent structures of meaning associated with this approach. First of all, it was clear that the academic researcher did not ask the residents whether they wanted to hear a story, or which one. She automatically assumed the right to begin the relationship in this manner. Given that it is unusual for one adult to read other adults a story, there are few contexts where this would not appear infantilising. In the context of a reading, the story would be understood as a contribution intended to be entertaining or thought-provoking for the listener; it would be offered in its own right. In this case, the "story" represents a literary form whose enjoyment is appropriate for adults. Another plausible possibility is reading a story in an educational context, for example where a professor uses a story to illustrate her lecture. In such a situation, the story functions as an example from which one should draw a lesson. In this case reading aloud is a means associated with a concrete end, a didactic device. Both these forms have consequences for the relationships involved. In the case of a public reading one may speak of a symmetrical relationship between reader and listener to the extent that the listeners chose to attend and perhaps even paid admission. In principle, this is a service about which both sides agree. This is quite different from a situation where one person chooses a story from which others are supposed to draw a lesson. In this case the relationship between the participants is characterised by asymmetry, as in a teacher/student relationship. We saw here that although the academic researcher intended to open a space that was (as far as possible) non-hierarchical (Dialogue criterion 3), her concrete actions were contradictory and ambivalent. [41]

The continuation of the sequential analysis, where the story is interpreted, confirms this ambivalence. First of all, the story appeared incomplete. It was merely a snapshot of Frau Meyer waking up without plot or punchline. Ultimately, it was not really a story at all, but a prompt inviting the listeners to contribute their own experiences waking up in the care home for the first time. The statement "The first night in new surroundings" is grammatically incomplete. It requires a continuation, for example describing the first night as difficult or long or restless. This supports the theory that the story was a prop that the academic researcher was using to demonstrate or achieve something. [42]

There was more evidence that the relationship was asymmetrical. The story was told from the perspective of an omniscient narrator. Although the moment of waking up in a care home is a very intimate and private one, the narrator appeared to know all Frau Meyer's thoughts and feelings. Reading aloud transferred the omniscience to the academic researcher, creating the impression that she was an expert who knows everything about the situation of waking up in a care home—which is impossible of course. And this implicitly undermined the idea of co-production of knowledge (Dialogue criterion 1). [43]

The words with which the story was announced are also noteworthy. The academic researcher chose to call it "a little story". The diminutive had multiple implications: First of all, the story might have been short in the temporal sense. This communicates that its duration was limited and that, for example, no special attention span was required in order to follow it. But "little" could also mean that the story was about something not terribly complex, or that it presented something complex in a simple form. The story would then not just have been short in duration, but also not very taxing cognitively. But why should the academic researcher have supplied this information in advance? One interpretation would be that she suspected cognitive impairments among her listeners and wanted to reduce the difficulty of the task. Here she would have also been acting considerately by reassuring her listeners that the task is manageable. The concrete wording addressed the residents in a manner that undermined the horizontality of the relationship (Dialogue criterion 3). [44]

The story itself also painted a very passive picture (implicitly of the residents): The protagonist Frau Meyer was described as a thoughtful, sceptical person. In the scene, her radius of action was restricted to her bed. Her only movement was slowly pulling back the bedcover. The visual image created for the listener was equally limited: apart from the light nothing was learned about the appearance of the room; apparently, it contained only the bed. The emotions were also bland. There were two brief mentions of emotional states, and these were immediately resolved without further exploration ("For a moment Frau Meyer is unsettled. But then she remembers, ..."; "She feels wistful. But then she sighs, ..."). Stronger feelings were absent, there was no climax. The same applied to the displacement that Frau Meyer feels, which was downplayed. Describing it as merely "unfamiliar" implied that the narrator saw this uncomfortable feeling as resolvable simply through familiarisation: If Frau Meyer simply woke up in the care home often enough, the situation would no longer be unfamiliar. All that is lacking was routinisation. Altogether the narrator painted a picture of a woman characterised by fatalism and conformity. The academic researcher's story appeared to promote passivity and accepting the inevitable over drive and desire for change. This created a clear discrepancy with her actual ideal of confident, active residents grasping the opportunity of the project and taking charge of the planning. Here the micro-analysis revealed that the chosen story may not in fact have been suitable to overcome the limiting situation (Dialogue criterion 6; see FREIRE (1996 [1970], p.31). [45]

The launch of the group process was later reflected with the critical friends (CF). They emphasised that the importance of finding suitable dialogue input should not be underestimated. CF3 observed that the question "What story do you tell and how and why?" was both difficult and crucial, because the thought processes generated by the input already pointed in a particular direction that might in fact be irreversible. CF2 also pointed out the difficulties created by the high expectations presented in the scene. These different intertwining expectations could lead to confusion and impede the dialogue, which actually presupposes openness (Dialogue criterion 3):

"If you read this story aloud then it is about the expectations they had as residents when they arrived at the care home. And at the same time your own expectations are also very present. You are also starting something yourself, you are there for the first time. The processes kind of run in parallel. You have expectations but they also have expectations. Or you want to know what their expectations are." [46]

In the situation, the residents did not respond to the story as the academic researcher expects. They remained silent. Then, according to the research journal, two residents said that they could not remember moving in. Only one was willing or able to respond to the story at all, saying that the transition had been hard. "But she doesn't give details either." The academic researcher was disappointed by the response: "The silence feels uncomfortable." The theme she chose transpired not to be generative (Dialogue criterion 5). [47]

Finally, the head of care staff intervened and related from her perspective what she would find difficult if she moved into a residential institution. The academic researcher commented in her diary: "I become uneasy. I have the feeling I am losing control over the discussion, although only a few minutes have passed. I don't want to end up with only [the head of care staff] on the recording." This entry revealed the pressure the academic researcher felt to produce results. She had a conception of what she wanted to capture on the audio recording and was unable to drop the thought. CF4 observed:

"in that moment your interest [as academic researcher] is not only in the dynamics of the moment but also in what will be on the recording afterwards and the idea that you need to direct it in a particular direction. That is understandable because the question of what is on the tape is not irrelevant to the research. But it also shows that especially in participatory research there are meta-ideas about how things should be". [48]

These idealisations concerning the research process created pressure to bring about a particular course of action and behaviour. But this hindered openness and playful experimentation (Dialogue criterion 7)—on the part of the academic researcher as well as the residents. Already at this early stage of the interaction, the possibilities and freedoms of all involved were conditioned and constrained by conscious and unconscious expectations. [49]

After reading the story failed to generate the desired discussion, the academic researcher asked the residents what their wishes were. The very use of the term "wishes" is open to interpretation. "Wishes" are often something intimate and personal. In German, one might be asked what one wishes for in a restaurant, but in that context the scope of the wishes is defined, for example by the menu. If, as is the case here, one is asked about past hypothetical wishes and encouraged to remember and reflect, the question is driving at private (perhaps even secret or unspoken) yearnings and emotions. To inquire about these would only appear legitimate in a context characterised by familiarity—either where one is speaking with family or friends or because the person asking the questions is entitled to trust on the basis of their role (therapist, doctor, priest). The first was plainly not the case. Thus, the academic researcher was apparently asserting a role that entitled her to ask the residents such a highly personal question. This again raised the question of equality in the relationship (Dialogue criterion 3). [50]

The term "wishes" also contains another dimension. Wishes are expressed in contexts associated with the magical; the person making the wish normally has no control over its fulfilment. By asking the residents about their wishes the academic researcher was assigning them a passive role. They were addressed not as holders of rights they can insist on but as wish-makers dependent on wish-fulfillers. Actively and independently overcoming the limit-situation was not a possibility (Dialogue criterion 6). Instead, the question of wishes reiterated the asymmetrical nature of the relationship between academic researcher and residents, where the latter were assigned a passive role dependent on the assistance of others. [51]

The critical friends also discussed the question of wishes and what it says about the relationship between the academic researcher and the residents. CF1 pointed out that the academic researcher enjoys a knowledge advantage. She knew the project's objectives and had thought about how to initiate the group process; for the residents the entire situation was new and confusing:

"Well I'm just imagining if someone I don't know comes and asks me what I wish for, then I would find that very abstract. I would probably wonder what the question is driving at. What are you after? What good does it do me to tell you? Will the wish be fulfilled if I tell it you? Or are you just wanting me to provide information? So what—what is ... what is the expectation? What should I give you? For us this question about wishes is always so clear, but for the people being asked it's unclear in the first place, so what should I say there then?" [52]

The academic researcher also sensed the ambiguity that characterises the situation:

"Why am I asking about wishes? I want to create a space where the residents can think and plan freely and without limits. But I am not even so sure about my own openness. My assumption is that if you live in a care home there's quite a lot you have to do without. You have to put up with quite a lot. The most obvious wish is that residents want to go 'back home'. But I certainly can't offer them that. Nor more staff or bigger rooms. Does that make me a fraud? I go into the discussion and ask an open-ended question about wishes, but I already know that within the project only particular wishes are possible. They could go into town and choose what they want to buy, or go on an outing to a place that means something to them, or talk to someone without pressure of time ..." [53]

These thoughts underline the great importance of context (Dialogue criterion 4). The academic researcher and the residents were not meeting in a contextless space; the institution of the care home demanded consideration. This turned the researcher/residents dyad into a triad that always also included the care home. One indication of this was found in the way the question about wishes was formulated: the academic researcher was not asking generally about wishes but specifically what should happen "here". But she was aware that this was not unproblematic, because the context also created a limit:

"I so want to do justice to the idea of empowerment and that also means being able to think freely. Is it not precisely my job as the academic researcher to create a safe space where all ideas can be raised and rejected, imagined and planned? But I am not free myself either. My wishes for this research are also limited and constrained. How do I deal with that? I have no answer, but still I think it's important to ask the question about wishes." [54]

In the third segment, a resident spoke. She answered the question about wishes with a monosyllabic "normal". For her, that adequately answered the question. This response is open to different interpretations. It could represent R2's attempt to ward off the academic researcher's question (in the same way as a teenager might counter a parent's question about how school was with a terse "normal"). In this case, one could conclude that R2 felt the academic researcher's question to be intrusive or inappropriate. That would have revealed a disturbance in the communication resulting from contradictions in the preceding dialogue. In that case the attempt to achieve polyphony (Dialogue criterion 2) would have failed. [55]

Another interpretation is also possible: R2 was seriously seeking to answer the question about yearnings and hopes and intimate thoughts, and normality was what she actually wished for. In that case, she would have been recognising the academic researcher's right to ask such questions and accepting the dialogue prompt. In this second interpretation, the brief "normal" served a placeholder function: The concept of the normal stood for a whole world of social actors, interactions and structures, which R2 took so for granted that she saw no need to spell it out. Normal was "Just how it is, yeah". But it was unclear what this normality relates to: Did she mean life in the care home? Did that mean life there was how she would have wished? Or was R2 wishing for a normality that did not (or could not) exist in a care home, for example the normality of life before moving there? [56]

The academic researcher was disappointed by the response. She noted: "The question about wishes was not a success. The brusque answer that everything should be 'normal' is kind of frustrating." She suspected: "Perhaps the idea of thinking and talking about wishes is simply so left field that it just doesn't work? Maybe there is not enough thought headspace to develop wishes and utopias?" But, as CF3 pointed out, normality was not banal. The objective of dialogues—to overcome the limits of the conceivable (Dialogue criterion 6)—needed not necessarily mean completely overturning reality. Maintaining normality could also be the objective of the shared search:

"Well, ... if the residents can continue to live their normality, then of course that's quite a big thing. If they can have the normality they had at home—being able to decide for themselves what they do when and that being seen as normal—then that would be a major gain for autonomy and self-determination." [57]

There might have been other reasons for residents to choose not to name concrete wishes. CF1 observed that the cautious and perhaps inhibited response was understandable, given that the academic researcher was not going to get out her magic wand and fulfil them: "... well that's also what makes one sceptical, now to ... express or reveal these wishes, because what good does it do me to think about them ... to name a wish if—if I know that it's not going to be fulfilled?" CF1 warned that one must be cautious about conveying an expectation that we were going to change things together: "And how much of it can then really be realised". It must have been remembered that the residents form an involuntary community and would certainly not all choose to live together or even be friends. There might have been reasons for residents to choose not to reveal everything about themselves that actually did have nothing to do with the academic researcher, but arise from the group dynamics. The head of care staff raised an alternative scenario: one could learn about wishes without asking about them directly. This presupposes a slower, less focussed but still attentive dialogue (Dialogue criterion 7):

"She [the head of care staff] also believes that a lot is explained by biography and that being asked directly about one's wishes creates a difficult, even overwhelming situation. She says that in her work as care assistant, wishes are often implicit in the conversation and interaction with the resident. For example, when she is planning an outing she doesn't get much response if she asks: 'So where are we going to go to next time?' But when they are out and about someone will suddenly mention a place they would like to see again." [58]

R2 continued after a brief pause and started explaining what normal means: "one gets up, drinks a coffee and does something or other". It is conspicuous that she did not speak in the first person but used the de-individualised "one" ("man" in German). "One" is used where the speaker is subsumed in the general, or wishes to be. In this interpretation R2 was speaking on behalf of all the residents at the meeting. At the same time, her expression identified a difference or front between the residents and the academic researcher. While this created polyphony (Dialogue criterion 2) by creating a counterweight to the academic researcher, it also inhibited it by presenting the residents as a homogeneous and monolithic group. [59]

Her description of normality took the form of a list of activities. This contrasted to the earlier "that should happen here" with which the academic researcher assigned the residents a rather passive role. R2 used the active form here ("one gets up" rather than "one gets woken up"). This assigned the residents the active part, amplified by the existence of options: While getting up and drinking coffee (breakfast or afternoon coffee) are the same for all, the schedule is open in-between. Therefore, the possibilities of action are not fixed for everyone; we are not in the military where everything is done in lockstep. Instead, R2's "something or other" emphasised the variability in the way things are done. At the same time, there was something aimless about the expression, as if it were about filling the time within the framework prescribed by the institution (for example the times for coffee). [60]

In this everyday routine, there was no mention of helpers nor were restrictions discussed (one might have expected to hear "then our breakfast is prepared", "then the sister helps me get dressed"). The caretakers and helpers are either so normal that they are not mentioned at all, or they are perceived simply as assistance, as an aid like a wheelchair which there is no need to mention. It is also conceivable that R2 associated a "normal" life with a life without care needs and therefore described an everyday life where helpers do not exist. Restrictions and care needs certainly do not appear to dominate the internal image of a normal day. [61]

Then R1 joined in and continued the description of the normal. She also saw the residents in the active role: they eat what they want, namely crusty rolls. The adjective "crusty" has positive connotations, its use is an expression of enjoyment and appreciation. There are several potential interpretations of R1's specific choice of crusty rolls as her example. First of all, it indicates the importance of meals in the everyday routine. It is a dominant and apparently also generative theme (Dialogue criterion 5): it motivates residents much more than the events when they moved to the home. At the same time, it might also indicate distancing from the overwhelming majority of residents who are fed by helpers and would be unable to chew a "crusty" roll. The residents attending the meeting thus establish themselves as the "healthy" elite in the care home. Finally, the statement "Eats a crusty roll" sounds as if it could be taken from an advertising brochure for the care home. In this interpretation, the contribution might suggest that R1 wanted to defend the care home against attack by the academic researcher (whose question about wishes implies dissatisfaction). This is further reinforced by the next statement: "That's how to start the day." The expression suggests that R1 would be able to list many more positive examples, that there are many other possibilities for positively connoted activities in the home. This paints everyday life in the care home in a good light. No indications of unfulfilled wishes are revealed. This line of argument continued with R1 asserting "that always tastes good". She did not express this as her personal opinion but formulated an apodictic statement for the collective that excludes all who disagree with it. Even if the follow-up, "Well it's true, isn't it!" suggests that there may have been an expression of doubt in the situation (for example one of the others shaking his or her head), R1 dismissed the contradiction. She asserted the power of interpretation. [62]

R1 answered the academic researcher's response (a brief "Yeah" that can be interpreted as a neutral prompt or as scepticism) with an energetic and engaged "Yes, yes, well I'm always really looking forward to it." The repetition created a double climax—committing the fellow residents to the opinion of R1 and R2, and contradicting the academic researcher. The care home cannot or must not be criticised, making the dialogue into a monologue (Dialogue criterion 2). It is interesting that R1 switched to the first person here, to express her subjective pleasure. This is the first instance in the discussion where a resident appeared as an individual. One could conclude that this relativised the claim to represent a group opinion and indirectly acknowledged that the other residents' experiences may be different. Immediately after this, however, R2 switched to "we" and thus continued to treat the residents as a block. The collective "we" encompasses the group (and possibly all the home's residents) but not the academic researcher, who do not share the experiences in the home. R2 supported the strategy of defending the care home by not mentioning anything negative, and explained what is special about the crusty rolls: "We don't get that at home do we, we have to go and fetch them ourselves." The reference to "at home" is notable. This must refer to the place of residence before moving into the care home, yet R2 used the present tense here. This suggests that the residential facility is not "at home" but also that the prior place of residence is as present as if it still existed. By comparing breakfast at home with breakfast in the care home R2 turned the rolls into a parameter of normality: Fresh rolls are not normal at home, but they are in the care home. In the care home context, she spoke of rolls in the plural, while at home only one is fetched ("it"). In this way, the care home is associated with the idea that abundance is normal, while frugality belongs to "home". The categorical "don't" in "don't get that at home" backs up the interpretation of experienced shortage of (particular) foods. Rolls have to be fetched, making them a luxury for which "extra" effort is undertaken. While everyday life in the care home was thus far described as consisting of activities, R2 described a passive role for the first time here: "We don't get that at home". But the function of the negation was to underline that such passivity was not possible at home where the rolls had to be fetched (requiring spatial mobility). In the care home, conversely, the rolls are brought to them. [63]

R1 spoke again and formulated a conclusion: "You get everything put in front of you." Here she picked up the theme of the passivity of the residents. It is conspicuous that no subject is mentioned here. Whereas the residents have thus far spoken of themselves not as individuals but as a group ("we", "one"), in the moment where something is served out the subject reference vanishes: it remains unclear who gets what and from whom. The only thing that is clear is the totality of the statement: "everything". The academic researcher viewed the connotation implicit in the formulation as more negative than positive: "to me getting everything put in front of me is the opposite of participation, of self-determination and dignity, it makes one passive". But R1 connected her description with a positive exclamation: "well that's super isn't it?" Again, different interpretations are possible. R1 could have meant the statement ironically or sarcastically. In that case, she would be criticising the practice of getting everything served up but signalling that she cannot express this openly or directly, perhaps for fear of reprisal. Up to this point, however, there was no indication of irony on the part of R1 and the next statement—where R1 reiterated her approval ("I think so too, mmh, yeah")—would appear to confirm that it was not. A second interpretation would be that R1 is bluntly describing a practice ("You get everything put in front of you") but did not perceive it as negative. In this case getting everything put in front of you is especially good. [64]

The academic researcher wrote that she was reminded of the concept of "acquired needlessness" (THEUNISSEN, 2000, p.126). This arises where a person learns in the course of an institutional biography that needs are standardised and there is no place for personal choice. "In the institutional mainstream individual wishes, abilities, needs, worries, resources and yearnings fall by the wayside" (SCHULZE-WEIGMANN, 2011, p.45). The academic researcher wondered how she should deal with this. Accept the "wall of satisfaction" or attempt to break through it? CF2 said she believed that "active silence" needs to be taken seriously; it represents a strategy because certain things are simply too hurtful to speak aloud. She was referring to a concept of silence as agency: "Agency, well silence as agency, means that certain things are simply not said and that can also be regarded as a strategy, as a group strategy." [65]

In the excerpt, the academic researcher continued with "Okay, okay", which is open to multiple interpretations. One would be that she has slipped into the role of a person entitled to trust on the basis of her position (such as therapist or priest). In that case, the response would serve to maintain the narrative flow and indicate active listening. Another interpretation would be that the academic researcher is retreating: Asking about wishes was interpreted as an attack on the care home against which the residents defended themselves by expressing their satisfaction, leading the academic researcher to defer. In that case her "Okay, okay" would have a conciliatory tone and signify acceptance that the residents do not wish to criticise, or cannot do so. [66]

The academic researcher wrote in her journal: "I wonder what I'm doing here. It is an ethical dilemma. Should I encourage people who say they are satisfied to change things (and in the process perhaps face their own dissatisfaction)? What does the right not to participate mean?" The critical friends also considered the challenge of this situation. CF1 felt that it would be desirable to begin by agreeing to a shared definition of change. She questioned the assumption of action researchers that change is always good and desirable:

"... especially with older people when they already have their routines and so on, change can stir up feelings that are better left alone. I mean those are only interpretations, but in psychoanalytical terms a routine is good for ensuring that—that things remain as they ... as they are. In order to avoid stirring up matters that would be painful or whatever." [67]

The academic researcher and the head of care staff agreed that they did not want to cajole the residents, but they did want to expand the bounds of the thinkable (Dialogue criterion 6):

"it is important to express wishes, that we perhaps want to see the residents' group as a place where they can be reminded of their wishes and so to speak empowered (my term) to express them. ... Perhaps the motto for the PaStA project in care home 2 is less to organise another outing or a new activity but more to establish and promote a culture of wishes? Allowing the imagination to roam, thinking outside the box, losing a bit of the acquired needlessness?" (Research journal, protocol, January 28, 2018) [68]

The starting point of our research was the question of how joint production of knowledge by academic and lay researchers can occur in practice. We found inspiration in the work of FREIRE and BAKHTIN, who both thought deeply about transformative dialogues. We were able to condense their ideas into seven criteria for an ideal dialogue. In order to investigate the challenges and difficulties that arise when these ideas are put into practice, we subjected an initial part of an audio transcript to micro-analysis. The subject of the interaction was the academic researcher's efforts to initiate a dialogue with the residents of a care home so as to generate knowledge about the possibilities of participation in residential care. In the sequence at hand the academic researcher read a story to a group of residents and asked them about their wishes concerning daily life in the care home. [69]

For the purpose of grasping the full complexity of the interaction, we investigated the academic researcher's subjective perspective (using an autoethnographic approach), the latent structures of meaning (using sequential analysis following objective hermeneutics), and the observations of critical friends (with collective reflection of the process). This enabled us to undertake a thorough reflection on the dialogue. What have we learned from the analysis? In order to answer that question, we now revisit the seven criteria that guided our investigation and consider what they say about the preconditions for co-production of knowledge. [70]

5.1 Dialogue criterion 1: Orientation on shared search for knowledge

As noted at the beginning, co-production lies at the heart of participatory research. Our example demonstrates, however, how difficult this is to truly realise (as opposed to merely paying lip service). In the case of PaStA, the initiative for the research project came exclusively from the academic team. Its members wrote the application, secured the funding, located interested care homes and finally—via the services of the care assistants—invited residents to take part. In other words, at the point where the academic researcher encountered the residents, she had already been working on the project for a year and a half and had gained a multitude of insights and experiences, while the residents—lacking this prior knowledge entirely—were confronted for the first time with the expectation that they were going to join a "participatory project". Although the academic researcher had already spent time in the care home and was a familiar face for most of the residents, the analysis clearly shows the stresses inherent in the situation. Such excessive demands will inevitably have consequences, as we saw in the reactions of the residents: at least at first, they adopted a defensive stance and declined to respond to the academic researcher's input. The insight to be drawn from this is that co-production cannot be treated as a premise or starting point. It needs to be generated and fulfilled in the course of the process. Thus, the question is not whether the academic researcher and the residents originally set off on a collective search but whether the search became a collective one in the course of the project. For this reason, participatory researchers devote great attention to the establishment and negotiation of partnership (DURAN et al., 2013; ISRAEL et al., 2008; RUSSELL & KELLY, 2002). This would appear all the more relevant where the participatory project is initiated by the academic researchers. [71]

But to what extent is such an initiative legitimate at all? What gives the academic researchers the right to initiate a process of liberating education (FREIRE, 1996 [1970])? Does this not mean that the very foundation of cooperation is itself characterised by asymmetry? Given that the dominant narrative in a community (here the institutional order of a care home) can have a paralysing influence and generate apathetic compliance rather than insubordination, there is a danger of the process of conscientisation being suffocated in a "culture of silence" (DARDER, 2018, n.p.). In this case, people are satisfied with a "placatory practice that attempts to make life just a little bit better around the edges" (LEDWITH, 2016, pp.8-9), but remain at the same time oppressed (FREIRE, 1996 [1970]). A critical intervention is required to initiate liberation—not by the researchers explaining the world in a monologue but by beginning a mutual reflective dialogue that leads to conscientisation. [72]

5.2 Dialogue criterion 2: Promotion of polyphony and avoidance of monologues

Giving marginalised groups and individuals a possibility to contribute their ideas and breaking the monologue are important elements of successful dialogue after BAKHTIN and FREIRE. The point is not for all participants to speak with a single voice but to admit as much polyphony as possible. In the investigated example we saw how difficult it can be for the participants to permit this to occur. In the case of R1 and R2, one sees a rhetorical attempt to speak not only for themselves but for the group—which meant suppressing other, possibly diverging, opinions. This created a significant challenge for the moderator, in this case the academic researcher. Counteracting the attempt to homogenise without cutting the thread of the dialogue demands great competence in the facilitation of group processes. The sequence discussed here is too short to ascertain whether it was eventually possible to establish a polyphonous discussion culture. But it can already be noted that it is especially important at the beginning to clarify that nobody will be excluded. In addition to knowledge about research and research methods this demands a great deal of experience in dealing with groups and shaping group processes (LEDWITH & SPRINGETT, 2010, pp.141-147). Therefore, where academic researchers assume moderating roles (which will often be the case), they also need the opportunity (and willingness) to acquire the necessary skills and abilities. [73]

5.3 Dialogue criterion 3: Horizontal relationships in a space without hierarchical structures

Dialogue criterion 3 demands that the academic and lay researchers meet as equals. The few minutes of discussion analysed here demonstrate how difficult this idea is to realise, how quickly asymmetries can end up being reproduced after all. Interacting "as equals" is not something we can simply decide to do. As the analysis shows, something as trivial as reading a "little" story and asking about wishes can introduce asymmetricality into a relationship. That is not to say that the academic researcher intentionally planned to demonstrate her power. But such forms of behaviour can, for example, indicate that the complexity of the identity as care home resident was not adequately taken into consideration, that certain expectations were not, or not completely, fulfilled—for example, that residents are willing and able to communicate about everyday life in the home—or that conflicts of goals existed. The academic researcher was committed by the logic inherent to every research project to produce results within a specific space of time. She therefore had concrete goals, in this case, for example, to discover participation possibilities in the care home and ways they can be improved. At the same time, this goal orientation stood in the way of a genuinely horizontal relationship. In such a context, the collaboration between the academic researcher and her lay co-researchers could not be negotiated as between equals, but was already predefined. This contradiction created a tricky dilemma for co-production of knowledge, to which there were no easy answers. Power differentials are a social reality that participatory research can only seek to lessen or compensate. The dissolution of hierarchical structures must remain a utopia. Nevertheless, this does not exempt researchers from consistently reflecting on and (re)negotiating the power relationships in their research practice. Our contribution describes one such example of self-reflection. It reveals in particular the potential importance of micro-analyses (in this case of the announcement of a "little story"). The crux is to employ the (limited) situational possibilities and windows of opportunity that participatory research produces to shift the bounds of thought and action—at least a little. In the present example, this occurred when the project group proposed, planned and implemented the idea of growing herbs on the balconies. In that moment, the women contributed their life experience and shaped the course of the project according to their wishes. [74]

5.4 Dialogue criterion 4: Dialogue historically and culturally sited

Dialogue criterion 4 reminds us that successful dialogue is only possible if there is an understanding for the other in the concrete historical and cultural contingency. Dialogues do not occur in isolation from their context. In our example, it quickly became clear that "the care home" was always present, with its institutional order characterised by hierarchical relations and dependencies. This largely prevented the question about wishes from unfolding its utopian potential; in fact, it triggered defensiveness. In other contexts, the same question might have been well suited to encourage people to think about their visions for the future. Here instead it led to conformity with the home's inherent logic: "You get everything put in front of you, well that's super isn't it?" (R1) The question was how the academic researcher handled this. She could regard the statement as complete rejection of the idea of transformation and terminate the process. Or she could read the statement as information about the limits of the concrete transformation potential. In that case, knowledge about the specific situation of the dialogue partners (living in an institution and having to come to terms with the given conditions) helped her to understand the resistance to change at this point. [75]

5.5 Dialogue criterion 5: Generative themes that are relevant for the dialogue partners