Volume 22, No. 3, Art. 16 – September 2021

Creating Space by Spreading Atmospheres: Protest Movements From a Phenomenological Perspective

Sandrine Gukelberger & Christian Meyer

Abstract: How are spaces constituted through social action, and how do they constitute social action? We address these questions by studying how protesters appropriate spaces by occupying streets and public buildings and by spreading specific atmospheres. We apply Alfred SCHÜTZ's phenomenological take on the constitution of multiple realities in terms of "province of meaning" as a heuristic device to capture the diversity of protest atmospheres along with their spatial, affective, and epistemic dimensions—those embodied and situated as well as virtual. This perspective allows us to describe empirical examples of protest situations in South Africa and Senegal where "the streets" and the media meet. Our research material spans documents, tweets, video material collected online, and ethnographic interviews. In this article, we look at how embodied practices reproduce and manifest particular "provinces of meaning" and "protest atmospheres," and how these embodied practices are complemented by social media practices. Our proposed approach not only provides an example of how a social space is created and refigured through social protest, but also allows a further understanding of the situational emergence of protests as collective action that creates "we-experiences." The phenomenological perspective goes beyond the widespread mind/body dualism that underlies so many interpretations of social movement culture.

Key words: phenomenological sociology; sociology of space; refiguration of spaces; social movements; protest cultures; atmospheres; province of meaning; appropriation of spaces; Senegal; South Africa; ethnography; video analysis

Table of Contents

1. Protest Movements and the Appropriation of Spaces

2. The Phenomenological Take on Atmosphere and SCHÜTZ's "Province of Meaning"

3. A Phenomenological Approach to Protest Movements

4. Protest Cultures and the Appropriation of Spaces

4.1 Embodied practices and symbolic collective action

4.2 Medial re-configurations of social protest

5. Refiguring Protest Spaces

1. Protest Movements and the Appropriation of Spaces

Protest movements can be thought of as alternating between organizational and thematic tasks, often performed in partly isolated working groups or through digital communication, and the public manifestation of opinions through marches and rallies. In these latter forms of demonstration, protest movements—along with their claims—also establish and disseminate atmospheres. Such atmospheres are witnessed not only by those who protest but also by observers, as media reports ubiquitously illustrate: "Young protesters marched in a joyful atmosphere chanting slogans about global warming like '1, 2, 3 degrees, it's a crime against humanity'" (AUTHOR UNKNOWN, 2019, n.p., reporting on the "Fridays for Future" protests) or "We do not know for sure what groups may attend, but we are mindful that the current atmosphere is highly charged, and protests that begin peacefully do not always remain that way" (PHILLIPS, 2018, n.p., reporting on student protests against white supremacy at the University of North Carolina in 2018). [1]

Accordingly, Anouk VAN LEEUWEN, Bert KLANDERMANS and Jacqueline STEKELENBURG (2014) and Anouk VAN LEEUWEN, Jacqueline STEKELENBURG and Bert KLANDERMANS (2016) began both of their articles on protest atmospheres with a brief overview of newspaper coverage on people from all over the world describing atmospheres in relation to protest events. They also alluded to scholars who reported on protest atmospheres (e.g., DELLA PORTA, ANDRETTA, MOSCA & REITER, 2006), or referred to such atmospheric synonyms as mood (WADDINGTON, 2007) or climate (BESSEL & EMSLEY, 2000). Thus, they highlighted that protest atmospheres may adopt different qualities, such as "good, positive, peaceful, calm, collaborative, friendly, respectable, festive, holiday, negative, chaotic, serious, tense, hostile, aggressive, volatile, or violent" (VAN LEEUWEN et al., 2014, p.82). [2]

The English term "atmosphere" stems from Greek and denotes the gaseous envelope around our planet. Besides this spatial definition, since the eighteenth century, it has also been used to circumscribe ambiances and feelings related to places, things, or artistic works (RADERMACHER, 2018; RIEDEL, 2019). Using these etymological roots as a point of departure, in this article, we focus on how mediatization changes spatial atmospheres in the cultural context of protest in South Africa and Senegal. We are interested in how protest movements spread atmospheres and thereby appropriate spaces, and in doing so, we pay particular attention to the affective and epistemic dimension of protest situations. We argue that protest movements situationally establish, through different media (ranging from atmospheres, to techniques of the body, to social media), a specific so-called province of meaning. [3]

We situated our research of protest movements within the interpretative paradigm and based it on grounded theory methodology (GLASER & STRAUSS, 1999 [1967]; STRAUSS, 2008 [1987]), utilizing its ideas of circular research processes—collecting data, analyzing data, writing text—and following its principals of theoretical sampling. We derived our data from different protest events in South Africa and Senegal. Among these data are documents, tweets, and online video materials we collected from the internet. For the detailed sequential analysis of individual video recordings, we aligned ourselves with the methods of video-supported ethnomethodological conversation analysis (MEYER, 2014). In this respect, in our analysis we treated the online video materials as various accounts of social situations and protest events. Robert SCHMIDT and Basil WIESSE (2019, §5) highlighted online participant videos of protest situations as "natural," as they are not made for research purposes, but by participants themselves, "which they then disseminate on the Internet, where the accounts are interpreted, commented on and analysed many times over" (§15). In accordance with SCHMIDT and WIESSE, we consider such data sources as a "product of the situative relevance of the participants and the attraction of temporary centres of attention that form in these social situations" (§17), but view them from a phenomenological perspectives as actors' constructs.1) In addition to these data, we therefore conducted four ethnographic interviews (BÖHRINGER, KARL, MÜLLER, SCHRÖER & WOLFF, 2012; OBERZAUCHER, 2014) with persons who positioned themselves as activists. These interviews included activists' interpretations of selected video sequences. In order to get access to interview partners, Sandrine GUKELBERGER has built working relationships with activists when starting her ethnographic fieldwork in South Africa on urban politics (18 months between 2005 and 2007) as well as in Senegal when researching protest movements (two months between 2013 and 2014 and nine weeks in 2019). These diverse forms of embodied knowledge as a resource for and as a topic of ethnography, together with the video analysis permit us to explore the affective and epistemic dimension of protest situations. [4]

To do so, in Sections 2 and 3, we refer to the phenomenological concept of atmosphere (BÖHME, 1995; GRIFFERO, 2014 [2010], 2017 [2013]), specifically, however, as a province of meaning (SCHÜTZ, 1945) and connecting it to public space (ARENDT, 1970; BUTLER, 2015). This will allow us to develop a phenomenological approach to protest movements—one that views them as a particular type of sociality. We thereby explore how a phenomenological approach relates to the central concept of the refiguration of spaces, featured in the previous and this issue of FQS (BAUR, MENNELL & MILLION, 2021; KNOBLAUCH & LÖW, 2017, 2020), and more precisely how it is linked to public spaces. This helps us in describing empirical examples of protest situations in South Africa and Senegal in Section 4, and in looking at how movements create an atmospheric protest situation that enables both agency and a so-called collective we experience. In our examples of protest movements, the protesting person is depicted as "a moving, speaking, cultural space in and of itself" (LOW, 2003, p.16), and collective embodied practices thus act as "centre[s] of agency, [...] location[s] for speaking and acting on the world" (p.10). In Section 5, we conclude our findings with reference to the refiguration of spaces. [5]

2. The Phenomenological Take on Atmosphere and SCHÜTZ's "Province of Meaning"

As highlighted in our introduction, journalists and the activists themselves, that is to say, external and internal observers, often describe protest situations as atmospheric. In this respect, Friedlind RIEDEL (2019) linked situations to atmospheres in the following way:

"[Atmosphere] fundamentally exceeds an individual body and instead pertains primarily to the overall situation in which bodies are entrenched. The concept of an atmosphere thus challenges a notion of feelings as the private mental states of a cognizant subject and instead construes feelings as collectively embodied, spatially extended, material, and culturally inflected. [...] Atmospheres are thus modes in which the world shows up or coalesces into an indivisible and intensive situation or in which a group of bodies comes to exist as a felt collective. In this regard, atmosphere operates as a medium that brings into appearance that which cannot be deduced from or reduced to the bodies present in a situation" (p.85). [6]

We can apply this definition to protest situations, where atmospheres arise and spatially extend a feeling of collectiveness. We want to use this idea to elaborate upon what enables people to act collectively when they join protest situations. We therefore understand atmospheres as media that animate protestors to experience situations, or reality, in a certain manner. In other words, atmospheres constitute the preconditions for the perception and experience of situational reality. SCHÜTZ (1945), in his text "On Multiple Realities," called the ensemble of these atmospherically shaped styles of reality Sinnprovinzen [provinces of meaning]. Each province of meaning is characterized by "essential elements" through which the individual actor experiences reality. Even though SCHÜTZ referred to the totality of these elements as a cognitive style, they encompass embodied and affective ways of experiencing reality as well. This style of experiencing reality includes the following essential elements (pp.537f., 552):

a specific tension of consciousness, meaning a way in which the ego's consciousness is directed towards what one experiences;

a specific epoché, meaning a way in which experience is epistemically accessed;

a prevalent form of spontaneity, meaning a way in which ego pragmatically assesses action upon the outer world;

a specific form of experiencing one's self in relation to what one experiences;

a specific form of sociality, meaning a way in which one's relations to others are experienced;

a specific time-perspective, meaning how time is experienced in relation to the outer world and the world populated by other persons. [7]

SCHÜTZ explored these dimensions in provinces of meaning such as "phantasying" (p.558), "dreaming" (p.559) and "scientific theorizing" (pp.563f.), and juxtaposed them to the "natural attitude" of everyday life (p.569), "Sleep," for example,

"may be defined as complete relaxation, as turning away from life. The sleeping self has no pragmatic interest whatsoever to transform its principally confused perceptions into a state of partial clarity and distinctness, in other words to transform them into apperceptions" (p.560). [8]

According to SCHÜTZ, provinces of meaning are holistic and "finite"—incommensurable with each other—so that the transition from one province of meaning to another is experienced as a "shock." These experiences of shock, he said,

"befall me frequently amidst my daily life [...]. They show me that the world of working in standard time is not the sole finite province of meaning but only one of many others accessible to my intentional life. [...] Some instances are: the shock of falling asleep as the leap into the world of dreams; the inner transformation we endure if the curtain in the theater rises as the transition into the world of the stage-play; the radical change in our attitude if, before a painting, we permit our visual field to be limited by what is within the frame as the passage into the pictorial world [...]; the child's turning toward his toy as the transition into the play-world; and so on" (pp.552f.). [9]

As we will show, protest movements equally possess features in which they are experienced by the individual participants. We will consider the features specific to protest movements in detail in Section 4. However, as we see it, the transition from the province of meaning of "everyday life" to another, such as the one associated with high performance sports (MEYER & VON WEDELSTAEDT, 2017), or that of social protest organized as a movement, is not necessarily a shocking experience for the individual. It is instead achieved only through elaborate and time-consuming social practices. In this article, we highlight in particular the social practices in protest situations that

set the conditions for this transition, for instance via social media;

allow for the manifestation of a province of meaning; and

allow for the appropriation of spaces. [10]

3. A Phenomenological Approach to Protest Movements

Several phenomenological approaches to protest movements were formulated by Simon RUNKEL (2018) and VAN LEEUWEN et al. (2014, 2016). They argued that such an approach deepens our comprehension of collective engagement, protest dynamics, and mobilization. RUNKEL (2018) referred to Hannah ARENDT (1970), saying that the atmospheres arising in collectively shared situations are important for strengthening the solidarity among protesters. Protesters "acting in concert" (ARENDT, 1970, p.82) also create a "new public space" (ARENDT, 1998 [1958], p.219). ARENDT called this a "space of appearance" (p.199), which comes into existence through collective action and speech. Accordingly, a "space of appearance" emerges on a street or on a square through protesting bodies who gather, move, and talk together, and lay claim to a certain space as public space (BUTLER, 2015). This also corresponds with the central concept of the refiguration of spaces in the FQS thematic issues, particularly in reference to Hubert KNOBLAUCH and Martina LÖW (2017, 2020). They argued that "the category 'space' itself needs to be deconstructed as the social is a decidedly spatial phenomenon, and they suggested to develop an empirically-grounded theory of contemporary social change as processual, spatial-communicative reconfiguration" (BAUR et al., 2021, §5). In this respect, Judith BUTLER (2015) rightly pointed out that protests do not take place in public spaces, but instead "reconfigure the materiality of public space and produce, or reproduce, the public character of that material environment" (p.71)—insofar as they are spatial themselves, but also, as we shall see later, for example, when protesters destroy statues. [11]

Such a perspective thus is focused on:

how movements create an atmospheric protest situation that enables a collective "we experience;" and

how individual agency is turned into an empowering atmospheric dimension for this enabling of a "we." [12]

In this respect, the studies of VAN LEEUWEN et al. (2014, 2016) were among the first to empirically investigate protest atmospheres and their affective side. In their studies of protests on the streets in different contexts in Europe, they concentrate especially on "the affective state that people attribute to the idiosyncratic features of a demonstration" (VAN LEEUWEN et al., 2014, p.84)—in other words, on the perceived protest atmosphere, in relation to police aggression for instance (VAN LEEUWEN et al., 2016). In our article, we go beyond these studies, which, in our view, treat the atmospheres of protest overly as a matter of subjective perception. Instead, we will investigate the atmosphere of social protest as a type of sociality that is produced by the participants through embodied practices. To detail the properties and experiential foundations of the type of sociality represented by social protest, we use SCHÜTZ's model of province of meaning and his experiential styles. [13]

We argue that protest movements establish, through different media (ranging from atmospheres, to techniques of the body, to social media), a province of meaning that is rendered recognizable through particular practices, specifically, varying social situations, and at differing times. Accordingly, while provinces of meaning are intersubjectively accomplished, participants perceive them at the same time as external and objective (GARFINKEL, 1967). The province of meaning of a social protest therefore enables participants to coordinate their actions, to establish a "we," and to act collectively. The practices used for establishing the particularities of the province of meaning of protests draw on—and reactivate—experiential reservoirs, in addition to repertoires of political action that are specific to the members of the protest collective. [14]

Hence, in a phenomenological approach, protest movements are understood as types of sociality that are characterized by typical properties that concern their experiential style. These properties distinguish themselves from those of everyday situations. They can be best identified by treating them as elements of a finite province of meaning, which in turn create an atmosphere of action allowing for particular affectivities and embodied forms of collective participation. The creation of affective involvement through the establishment of the province of meaning of protest is thus crucial for protest movements and is accomplished through practices that we will describe below. [15]

In our approach, we focus on aspects that are often neglected in relevant theories on social protest movements. For example, theories on opportunity structure (e.g., TARROW, 1989, 1994) center on the structural conditions of social movements but overlook their experiential dimensions. Approaches interested in frames and framings (e.g., GERHARDS & RUCHT, 1992), in turn, analyze the configurations of protest claims in their semantic and discursive aspects, yet disregard their embodied, participatory, and affective qualities, qualities which we regard as being of key importance. More closely related to our approach are theories of social performance (e.g., JURIS, 2014) that are interested in cultural practices and communication in order "to move beyond the mind/body dualism that underlies so many accounts of social movement culture" (p.229). However, we adopt a different perspective to the experiential reservoirs of social protest and performance. Our contribution to overcoming the dualism mentioned above is grounded in a phenomenological perspective, which pays particular attention to the fine-grained dynamics of situational emergence and the sequential dynamic of protest atmospheres. In the following section, we will address the properties of the type of sociality specific to protest movements in an empirical way, that is to say, the properties of social protest in South Africa and Senegal, where "the streets" and social media meet. [16]

4. Protest Cultures and the Appropriation of Spaces

This section centers around two protest movements: The #FeesMustFall student protest movement, which aims to decolonize the university system in South Africa; and the social movement Y'en a Marre, looking to establish a participatory political system in Senegal. Through these examples, we can explore the role that the province of meaning of protests adopts within a "space of appearance" (ARENDT 1998 [1958], p.199). [17]

4.1 Embodied practices and symbolic collective action

Beginning in 2015, the #FeesMustFall movement in South Africa has sought to decolonize the University of the Witwatersrand in Johannesburg, thereby mobilizing, especially via social media, students at universities all over the country (HODES, 2016; PETERSON, RADEBE & MOHANTY, 2016). On 9 March 2015 at the University of Cape Town, a student started throwing excrements onto the statue of Cecil John Rhodes. This student asked others to join him in removing this colonial statue from its prominent position on the university campus. The movement subsequently gained support from other protesters across the nation, as did the corresponding hashtag, which in itself has sustained a new social movement: #RhodesMustFall—a collective of students and staff members who campaign together against institutional racism at the University of Cape Town. A new similar movement was mobilized later that same year, after a 10.5% increase in university fees was announced, and which culminated in a march on the South African Union Buildings in November 2015, accompanied by the hashtag #FeesMustFall. Related protests also broke out at other universities in South Africa, which continue to reference #FeesMustFall (BARAGWANATH, 2016; for the role of social media in the case of #RhodesMustFall, FRANCIS & HARDMAN, 2018; TIMM KNUDSEN & ANDERSEN, 2019). [18]

The students laid claim to a particular space as public space by holding speeches, marches, and sit-ins accompanied by typical symbolic calls, songs, dances, naked protests, and artistic performances. They used their bodies to physically articulate their critiques and collective frustrations with rising costs and fees, to enact resistance, and thereby refigured public space. In this case, however, the students' rage was not only addressed at the government but also at society as a whole. The meaning of decolonization as understood by the #FeesMustFall movement and its predecessor, the #RhodesMustFall movement, is far from homogenous and relates to such varied subjects as (DANIEL, 2019):

the embodied pain, which for the students denotes black pain, and which they claim exists as structural and symbolic violence at universities in South Africa;

the Eurocentric content of their instruction;

intersectional forms of discrimination of, for instance, lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer und intersexual (LGBTQI*) students;

political dominance. [19]

On 23 September 2016, the #FeesMustFall movement at the University of the Witwatersrand marched to the headquarters of the "Congress of South African Trade Unions" (COSATU) to deliver a memorandum to its leaders. In front of the building, numerous demonstrators sat down on the street, while others stood and listened to one of the speakers, who called out loudly—without technical support—for COSATU to support the students' struggle as a societal struggle (Video 12)). In his speech, he asked COSATU not just to speak but to take action and to represent the interests of the "masses"—of "the black people." After having questioned whether COSATU are simply defenders of the "white monopoly" and "capital" (0:00-0:27 min.), he stopped talking shortly thereafter. A young man standing next to him took over and shouted "Amandla!" [power] (in isiXhosa) while simultaneously extending his arm in the air and making a fist. The crowd responded loudly with "Awethu!" [To us] in isiXhosa3), a South African version of the historical rallying cry "Power to the People!" while simultaneously extending their arms and making fists (0:27-0:32 min.). This call-and-response with associated gestures is used for different purposes in different political contexts, ranging from diverse protest situations to party political meetings of former underground movements such as the South African Communist Party or the African National Congress (GUKELBERGER, 2018; for call-and-response as a general feature of political rhetoric in specific African contexts, MEYER, 2009) Figures 1 and 2 show conventionalized representations of this well-known gesture, which is re-enacted and re-actualized time and again by protesters.

Figure 1: "Amandla! Awethu!" tracing of a symbol from http://www.amandla-awethu.com/ [Accessed: April 15, 2019]

Figure 2: A silhouette of Nelson MANDELA and his "Amandla! Awethu!" gesture, tracing of the image, https://www.123rf.com/profile_bluefern?mediapopup=24495539 [Accessed: April 15, 2019] [20]

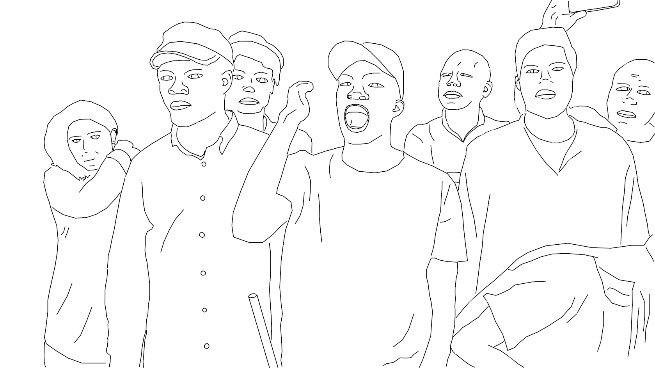

Figure 3 depicts how the young man, while shouting "Amandla!," is in the act of extending his arm into a straight position (followed by a downwards motion to a resting position). Through the synchronous upper body movements of contraction and expansion (including the movements of their mouths), the protesters in the crowd confirm their alliance with the joint response "Awethu!"

Figure 3: Students building alliances in front of syndicate building, tracing of a still from video (0:30 minute), https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=lb9PNRnyyUo [Accessed: April 15, 2019] [21]

This coordinated interaction through call-and-response forms a dynamic and moving cohesion amongst the protestors (who were either sitting or standing closely together around those who sat). After this quick interactive sequence between the young man and the protesting crowd, the speaker (on the right side next to the young man) took control of the situation and continued with his speech. Once more, he directly addressed COSATU and the urgent need for them to support the student protests. Bodily expressions such as the one described here have been, since the time of apartheid, associated with struggles against oppression and, as the speaker emphatically pointed out during his speech, against oppressed students in the South African context (0:53-0:55 min.). [22]

During his speech, the speaker can be seen holding a wooden stick in his left hand (Figure 3). One activist from Cape Town, who has connections to networks of student protesters in Johannesburg, explained to us the meaning behind wooden sticks:

"The sticks are a decorative tool [which stands] for pride of African Culture carried by warriors. In the main, so not only in protest, sticks are carried by [isiXhosa speaking] people and the spears and shields by [isiZulu speaking] people" (ethnographic interview 1, March 22, 2019, p.2). [23]

These sticks were also carried by other student protesters as they marched on COSATU headquarters (e.g., Videos 1 and 24); for the use of a speaker's stick in rhetoric in specific African contexts, MEYER, 2009). In different protest situations that occurred throughout that day, various shouts, songs, and dances referencing the anti-apartheid struggle could be seen and heard. In two examples, one of the speakers called out "Mayibuye!" [We must fight for it] in isiXhosa, with the crowd responding "iAfrica!," while at the same time extending their arms and making fists (e.g., Tweet 15), 0:00-0:14 min.); and the protesting crowd danced and sang "Siyaya noma kubi" (isiXhosa), which translates to: "We are marching forward no matter what dangers lie ahead" (e.g., Tweet 1, 0:15-0:21 min.). [24]

One particular dance performed by many students during the #FeesMustFall protests is known as the toyi toyi dance (e.g., Video 2). It comprises coordinated foot-stomping and dance movements involving the arms. It denotes a "jogging dance that imitated the physical training of guerrilla camps, as well as the wooden guns frequently carried at non-violent protests and the many songs and slogans which celebrated ANC guerrillas as heroes [...]" (SEIDMAN, 2000, p.165). There are many different variations of how the toyi toyi dance has become integrated into protests, in combination with hand-clapping, Amandla-Awethu call-and-response, and many different liberation songs. Figures 4 and 5 illustrate how this dance can be applied as a medium of protest. Figure 4 documents students performing toyi toyi in a circle to protest against the announcement of increases in university fees at University of the Witwatersrand.

Figure 4: "Students performing toyi toyi in a circle inside a university building," tracing of a photograph, https://www.dispatchlive.co.za/news/opinion/2016-09-22-radicals-are-right-off-base/ [Accessed: April 15, 2019] [25]

Figure 5 shows student protesters marching and simultaneously rhythmically performing coordinated toyi toyi movements through the campus at Fort Hare University.

Figure 5: Students performing toyi toyi against a hike in fees while marching through campus, tracing of a photograph, https://ewn.co.za/2015/10/20/FeesMustFall-Consensus-reached-on-increases [Accessed: April 15, 2019] [26]

In both cases, they were protesting against an increase in fees and what they perceived to be a corrupt university administration. At University of the Witwatersrand, student protesters coordinated their practices (hand-clapping, call-and-response, etc.) either when stopped during their march or when moving forward outside faculty buildings (Video 36), 0:10-0:16 min.), as well as while inside the buildings during their occupation (Video 47), 1:48-2:09 min.). Especially in the moments when hundreds of students acted in unison, their body movements and powerful sounds appropriated these public spaces with intensity and concentrated agency (Video 4, 1:48-2:09 min.). Michela VERSHBOW (2010) summarized these protest devices from a historical point of view in the following way:

"The power of this [Amandla/Awethu] chant [and dance] builds in intensity as it progresses, and the enormity of the sounds that erupt from the hundreds, sometimes thousands of participants was often used to intimidate government troops. As one activist puts it, 'The toyi-toyi [dance] was our weapon. We did not have the technology of warfare, the tear gas and tanks, but we had this weapon' (Power to the People 2008)" (p.1). [27]

Not only during the protests on September 23, 2016, but also in many other situations, the protesting crowds were dispersed by violent interventions (Video 3 and Video 4). Some of these incidents, in which students were confronted by police and shot at with tear gas, rubber bullets, or stun grenades, have been documented by protesters themselves or by journalists via social media (ibid.). One student protester commented on the violent situation that he found himself in, saying "It is a bit scary when you hear shots and then your friends are running, so yeah, it's a bit scary" (Video 3, 1:09-1:11 min.). [28]

On seeing the same video sequence, the activist from Cape Town remarked that "Throughout history our protests for independence, service delivery protests, student protests and so on, turned out to face police violence, so you always do not know what is going to happen when you protest" (ethnographic interview 2, April 11, 2019, p.1). When involving oneself in protest by means of singing and dancing, the tension of consciousness created in this process thus always includes the awareness of an incalculable risk of one being confronted with different forms of police violence. How a protest develops depends decisively on the affective state created by the protest atmosphere: It is shaped by either peaceful, or tense and violent interactions between protagonists, for example, between the protesters and the police. With this in mind, some students who organized and led collective actions appointed so-called "marshals," who were responsible for the protesters' safety and security (p.2). According to the activist from Cape Town, protest organizers appoint these marshals based on their reputation, standing within the respective "movement community," and knowledge of safety and security issues and crowd control. Marshals need to emanate from the "movement community." Normally, one marshal is responsible for around 25 protesters' safety and security. One example of the ways in which a marshal exerts control over collective actions is to direct the protesters in the first line of a standing or moving crowd to perform an activity in unison (ibid.). For instance, in the protest on April 4, 2016, around 25 protesters at the head of the crowd held a metal chain as a type of boundary in order to maintain an order of non-violence over the protesting masses that followed (Video 2, 4:29-5:39 min.). This line demarcated a zone that protesters in the following masses were disciplined not to cross. In front of this line, the marshals and various individual student leaders directed the standing or moving crowd via songs, calls-and-responses, dances, and speeches (with the help of a powerful megaphone). Through the guidance of the marshals, the chain symbolically served to control the affective state of the crowd and thereby promote a non-violent atmosphere within the protest: "protesters carry a lot of emotions and their demands are normally what they strongly feel to raise and as a leader and a marshal you need to be briefed properly by those issues too" (ethnographic interview 4, May 10, 2019, p.1). So in this case, marshals and individual student leaders coordinated and organized protesters by means of symbolic collective action in order to achieve a common aim. [29]

The described embodied practices are more ostentatious and more concentrated in their collective performance of movement than in everyday life situations that involve joint actions of dancing and moving; they are also less playful or elated, and more earnest. Student protesters thus enter the social atmosphere of protest by oscillating between collectively generating movements, rhythms, and sounds, and producing individual political speeches for the audiences. It is through the joint experiencing of the particular atmosphere that the participants are able to engage in the social practice of protest in a coordinated manner. When we asked the activist from Cape Town about how individuals actually become acquainted with these practices, he told us that many of the protest participants grew up with these protest calls, songs, and dances in their neighborhoods, and that they are seen as "our [fire]arm to fight against the injustice of poverty" (ethnographic interview 1, March 22, 2019, p.1). He explained that the "Amandla-Awethu" call-and-response, the associated arm and hand gestures, as well as songs such as "Siphethe amagerila"8) (and its chorus "We are not afraid because we got a spirit of no retreat, no surrender and we are not afraid"), are utilized by one or more protesters in order to get other protesters, comrades, neighbors, or friends in the mood and to motivate them to join in with acts of resistance. He added that, in fact, it is not enough to simply possess the embodied knowledge of the coordinated practices of protest described above. It is also crucial to verbally address in a bodily and rhetorical language so that they can comprehend the common issues of the protesters, particularly to accurately reflect and reactivate the sufferance and pain that the people endure on a daily basis. This serves as a potential source of mobilization, but it is important to do so in a way that the people can identify with (ethnographic interview 3, April 19, 2019). Therefore, both bodily and rhetorical devices are used to convince participants to join the protest as well as to maintain a protest "mood," that is to say, to establish and preserve the social atmosphere of protest. According to this activist, there are many other songs of protest that were sang "during the struggle against apartheid, in guerrilla camps in exile and inside the country in the heat of fire during boycotts" (ethnographic interview 1, March 22, 2019, p.1). In his view, these moments of protesting together in a closely connected, embodied way, are what allow one to express and experience solidarity with others. However, this solidarity does not just imply sharing the same issues and pains, but also aims to change them. This is how, in these moments, a common "we" is created: alliance, affective cohesion, and solidarity. [30]

In the course of the protests, the #FeesMustFall movement used various media to produce the relevant province of meaning and to create a corresponding atmosphere, ranging from collective rhythmized marches, individual speeches, call-and-response practices, musical performances, and the carrying of symbols such as sticks. If we relate our—necessarily cursory—findings to the elements of experiential style that SCHÜTZ conceptualized, we can say that the #FeesMustFall movement is characterized by a certain tension of consciousness. As we have seen, the protest participants—in their collective practices of ostentatious action, stylized gesturing, and coordinated rhythmical movement—created a highly attentive and vigilant "space of appearance" in the here and now, yet with the anticipation of a better future. This space of appearance, however, is highly affective, derived as it is from collectively shared experiential reservoirs, as well as from repertoires of protest action through which the former are re-actualized. SCHÜTZ (1945) described these experiential reservoirs in terms of an attention to life as follows:

"Attention à la vie, attention to life, is, therefore, the basic regulative principle of our conscious life. It defines the realm of our world which is relevant to us; it articulates our continuously flowing stream of thought; it determines the span and function of our memory; it makes us—in our language—either live within our present experiences, directed toward their objects, or turn back in a reflective attitude to our past experiences and ask for their meaning" (p.537). [31]

These repertoires and reservoirs are what SCHÜTZ and Thomas LUCKMANN (1974 [1973], p.99) called "stocks of knowledge." They are specified in the detailed historical contents of struggle songs, in a familiarity with symbolic bodily movements, and in distinctive shouts and dances of protests. As shown by these examples, the described practices have the potential to produce and deliver affects of shared pain and anger against common experiences of social and political injustice, and to bundle and concentrate these affects into a moment of joint focus that is taken to be decisive for the future. This leads to a form of sociality in protest situations that is characterized by the identification of the self with a larger collectivity, which shares affects and experiences, and unites the will of all people to transform the conditions in which they live. The province of meaning of social protest enables protesters to establish through rhythmizing and coordination a social "we"-body, transmuting their bodies into a collective site of political agency and into a spatial configuration of protest. [32]

The accompanying epoché is one in which relevancies and pragmatic constraints of everyday life are obscured in order to enable one to concentrate on the existentially decisive moment—the here and now. In this situation, the guiding principles of everyday life such as long-term planning, cautiousness, or circumspect decrease in importance in favor of the determined, kairotic grasping of the moment. This endows the protest movement with a characteristic time-perspective: one in which a painful past and an expectant future coalesce in the here and now—as a decisive instant for a radical change of course. Additionally, the idea that, through protest, one is able to create another future, that is to say, a better or more just future, represents a form of spontaneity: one that attributes the individual actor in a protest situation with the capability "to bring about the projected state of affairs by bodily movements gearing into the outer world" (SCHÜTZ, 1945, p.17). [33]

Finally, protest movements establish a typical form of sociality through "a common intersubjective world of communication and social action" (p.552). However, this intersubjective world is centered not only around the physical place-based protests. The videos of the #FeesMustFall protests circulating on independent media channels show how mediatization has developed as a dynamic driving force in spreading the atmospheric properties of protest. In what follows, we focus on the role of mediatization in social protest. [34]

4.2 Medial re-configurations of social protest

Even back in the 1990s, when social media played virtually no role in the organization of protests, William GAMSON (1995) described "movement activists" as "media junkies" (p.85). In this respect, GAMSON claimed that, with the famous protest chant "The whole world is watching,"9) demonstrators showed their awareness of the fact that they were making history in the very moment of protesting. This was amplified by the fact that they were at the same time being observed by the mass media. As he stated:

"The media spotlight validates the fact that they are important players. Conversely, a demonstration with no media coverage at all is a nonevent, unlikely to have any positive influence on either mobilizing potential challengers or influencing any target. No news is bad news" (p.94). [35]

In the same vein, one speaker of the #FeesMustFall demonstration in front of the COSATU building on September 23, 2016 addressed the need for protest movements to use media sources, both traditional as well as social:

"WE NEED THE MEDIA AS MUCH AS WE WANT COSATU TO TAKE A DECISION [...] BECAUSE YOU MUST REMEMBER THAT OTHER INSTITUTIONS, THEY DON'T HAVE THE PRIVILEGE TO OWN THE MEDIA HOUSES. NO ONE IS SPEAKING [...] FOR THE STUDENTS [...] WE ARE GOING, WE ARE GOING TO ALLOW THE MEDIA HERE AND WE ARE GOING TO USE THEM TO SPEAK TO BLACK GOVERNMENT" (Tweet 2, 0:00-0:45 min.). [36]

This quote indicates that protesters are actively involved in the production of a mass media audience, and allow information about issues important to them to be shared by students, government institutions, and national and international viewers through their use of media channels. It is then the processes of mediatization that set the conditions under which the province of meaning and the atmosphere of a protest movement can be established and spread. Thus, the first aspect of the role of the media in protest movements is that medial practices not only underscore an awareness that protests matter, help set the protest agenda, and strengthen an embodied "we" amongst protesters, they most importantly produce the communicative preconditions for the establishment of the type of sociality that the province of meaning "social protest" represents. A second aspect of the media's role becomes apparent in our example from Senegal that begins with leading figures of the protest movement Y'en a Marre [We are fed up] making an appointment with journalists from different media channels on April 7, 2017. This served to spread the message that a protest event would take place on the following day at the Place of the Obelisk in Dakar at 3:00 p.m. [37]

In Figure 6 shows the moment when one of the movement leaders made the official call to protest, his upper body is shown surrounded by TV microphones, smartphones, and other types of recording devices, which are pointed in the direction of his mouth. He asks all parties from "civil society" and "political society," as well as citizens in general, to participate massively in the protest in order to articulate their grievances against government policies. He outlines several times that the event will be peaceful and non-violent; that no provocation from others, or from those inside the ranks of the protesters themselves will be accepted; and that, by publicly announcing the protest beforehand, the national and international public will function as witnesses and external observers of this movement being a non-violent one (Video 510)).

Figure 6: Announcing protest in a press conference, tracing of a still from video (00:28), http://xalimasn.com/yen-a-marre-dans-la-rue-pour-denoncer-la-derive-vers-le-pouvoir-autocratique-de-macky-sall/ [Accessed: April 15, 2019] [38]

As in the previous example, the communicative preconditions for a protest movement-type of sociality are created through these medial practices, which are carried out into the world and legitimize the bodily forms of protest to come. However, in this situation, the "protest of tomorrow" is furthermore anticipated and reflected through medial practices, which generate national and international witnesses, and at the same time mobilize participants for future non-violent collective actions. The following day, this protest event did indeed receive massive participatory support and was well documented by diverse media sources, who reported a peaceful protest atmosphere. Particularly the protesters themselves, as social media users, also served as eyewitness documenters and writers of opinion pieces about their protests (e.g., Videos 611) and 712)). Thus, the media not only provides the means for establishing a communicative infrastructure of protest, they also help the movement itself to adopt a self-reflexive stance and thereby transcend its embeddedness in the here and now. There are similar online documentations of protesters participating in the #FeesMustFall protests. Figure 7 illustrates how students filmed the protest actions in front of the COSATU building with their smartphones to produce documents that transcend the embodied here and now situation.

Figure 7: Students recording their protests themselves with their smartphones, tracing of a still from video (0:20 minute),

https://www.news24.com/SouthAfrica/News/live-feesmustfall-students-plot-next-move-20160923 [Accessed: April 15, 2019] [39]

Social media sources are used here as a method of documenting protests in situ, thus transcending their embodied here-and-now nature. Student protesters who find themselves in the midst of the protesting crowd, and who are therefore involved "in the moment" of protesting, provide eyewitness accounts of their own affective and intellectual concerns as well as of the collective situation and atmosphere. In the case of the protests in front of the COSATU building, journalists and other media activists shared their photos, videos, and written posts via Twitter, Facebook, and other sites (e.g., Video 2). In response to these posts, other users discussed the speeches, police altercations, and other events documented. In these virtual spaces, embodied meanings, alternative stocks of knowledge, and interpretations of societal issues are circulated. [40]

"And if this conjuncture of street and media constitutes a very contemporary version of the public sphere, then bodies on the line have to be thought [of] as both there and here, now and then, transported and stationery [sic] [...]" (BUTLER, 2015, p.94). The examples of protesting bodies detailed in this article, which establish social atmospheres and the province of meaning of protest—both there and here, now and then, transported and stationery—also initiate a refiguration of public spaces at the conjuncture of "the streets" and the media. In our empirical examples, this refiguration of public space in protest situations has produced both offline and online audiences, a national and international public, witnesses, and external observers. In our examples, these shifting publics are located both on the streets and in the media, they emerge as a constitutive, if somewhat technically advanced, segment of protest sociality. [41]

Thus, through the mediatization of the province of meaning of social protest, the following transformations occur, expressed in the terms of the six SCHÜTZian elements of experiential styles:

The tension of consciousness shifts away from an extreme focus on the ongoing collective protest action, through social media, to a reflexive stance that anticipates that the protest is also normatively observed by absent publics as a mise-en-abîme.

The epoché is re-configured insofar as the relevance of social media audiences and the concentration of a performance directed towards them are included in the situation.

The spontaneity widens its scope from the direct world at hand to the inclusion of external publics as addressees who observe and assess the actions of the movement normatively—in other words, in terms of their credibility and legitimacy.

The experience of one's self is rendered reflexive as the self becomes an object of its own medial documentation.

The sociality of protest is expanded and transcended, since the protesting "we" is medially documented and broadcast to include absent groups.

The time-perspective is equally extended as documentation allows for the storage and re-use of the specific atmosphere in order to activate affects and stances. [42]

Starting in our examples of protest movements from the affected moving and speaking body, coordination with other affected moving and speaking bodies occurs as the participants together draw on shared experiential reservoirs. Through these coordinated actions, a social atmosphere emerges that encompasses affective as well as epistemic dimensions, eventually constituting the type of sociality characteristic of protest movements. The result is an atmosphere created through embodied practices that manifest shared experiential, affective resources, ultimately forming the typical province of meaning of protest. As we have shown in our article, these practices encompass songs, dances, and calls-and-responses that reactivate a shared reservoir of past experiences. As we have also shown, in today's protest situations, these embodied, situated practices are complemented by social media practices that ensure the dissemination of experiential reservoirs, goals, ideas, and atmospheres, alternative to the existing socio-political order, and with new normative orientations. Specifically, these normative orientations endow a movement with legitimacy. In protest situations, protesters themselves and external observers re-mediatize the collective actions of the protest in a (self-)reflexive way to reach out to other sociocultural contexts and forms, thus reconfiguring, and transcending, the social space of the protest. In this multiple spatial configuration, social atmospheres are, therefore, produced and spread not only through situated, embodied practices, but also through social media practices. [43]

In our view, and with reference to KNOBLAUCH and LÖW (2017), mediatization in this context is a mobilizing force in the refiguration of public space and the reflexive modification of social protest. In the process of refiguring space—that is to say, when protesters appropriate, embody, and mediatize space—not only do different locations become connected "by the circulation of knowledge, representations and things" (p.3), but the protesting individuals adopt a reflexive stance towards themselves and their actions. Accordingly, as our examples have shown, the sociality of protest—meaning its atmospheric dimensions and its province of meaning—is shaped by translocal "social contexts of different [offline and online] activities, forms of communication and societal functions" (ibid.), as well as by the integration of anticipated perspectives from others on the here and now of the protest situation. This, with reference to KNOBLAUCH and LÖW, underscores the need to polycontextualize the phenomenon of social protest. [44]

The ideas for this article stem from our research project "Jugendbewegung und der Wandel des Politischen" [Youth Movements and Political Change], in which we are, among other things, interested in mediatized practices and their role in the changing political cultures of urban Senegal and Bangladesh from a transregional perspective. This research project is funded by the German Research Foundation (DFG, Project Number 395804440), whom we would like to thank for their financial support. We would also like to thank the editors of this special issue for valuable comments on the earlier version of this text and Sebastian KOCH, who created the tracings for the figures in this article. Zachary MÜHLENWEG did language-editing.

1) We are aware that pragmatism (on which grounded theory methodology is based) and the phenomenological approach that we pursue here in this article shape two different traditions. However, they share many cross-connections and mutual fertilizations and influences, especially at the beginning of their establishment as social science methodologies (SRUBAR, 1988). <back>

2) Video 1: Media for justice (2016). Wits fees must fall student leaders speak out to COSATU leaders, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=lb9PNRnyyUo [Accessed: March 25, 2019]. <back>

3) IsiXhosa is one of the eleven official languages of South Africa and together with isiZulu is one of the largest spoken languages in the country. Both belong to the so-called Nguni language group of Bantu languages of Niger-Congo (KULA & MARTEN, 2008). <back>

4) Video 2: #FeesMustFall Protest, Wits University, April 4, 2016, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=6ThVA9ZCQeI [Accessed: March 25, 2019]. <back>

5) Tweet 1: Zuma concerned about violence at universities, https://www.news24.com/SouthAfrica/News/live-feesmustfall-students-plot-next-move-20160923 [Accessed: March 25, 2019]. <back>

6) Video 3: Fusion (2016), South African students take shirts off to protest police violence, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=YbFSIw7dl_4 [Accessed: March 23, 2019]. <back>

7) Video 4: #feesmussfall short documentary, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=pcG8qtykfkQ[Accessed: March 8, 2019]. <back>

8) "Siphete amagerila" is a local expression combining isiXhosa terms with the concept of guerrilla, which in this context refers to armed combatants trained in guerrilla warfare, and translates as "We have trained guerrillas." The song was previously sung by trained combatants, for example during past struggles for freedom. Nowadays it is retained in the cultural memory and serves as a "constant reminder of a bitter past that ordinary South Africans have gone through" (ethnographic interview 1, March 22, 2019, p.1). <back>

9) "The whole world is watching" was chanted by anti-war demonstrators in Chicago during the street protests of 1968, as TV cameras beamed images all over the world of protesters facing up to police enforcement. Since then, this slogan has become emblematic for other violent protest situations (GITLIN 2003 [1981]). <back>

10) Video 5: http://xalimasn.com/yen-a-marre-dans-la-rue-pour-denoncer-la-derive-vers-le-pouvoir-autocratique-de-macky-sall/ [Accessed: March 23, 2019]. <back>

11) Video 6: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=rPhp9k_8a-M [Accessed: March 23, 2019]. <back>

12) Video 7: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=741rYIbpz-M [Accessed: March 23, 2019]. <back>

Arendt, Hannah (1970). On violence. New York, NY: Harcourt, Brace & World.

Arendt, Hannah (1998 [1958]). The human condition. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

Author unknown (2019). Hundreds of students march in Paris for climate action. The Associated Press, February 22, 2019, https://www.apnews.com/6867eb8b379649f599ffe750aab2d373 [Accessed: March 22, 2019].

Baragwanath, Robyn (2016). Social media and contentious politics in South Africa. Communication and the Public, 1(3), 362-366, https://doi.org/10.1177/2057047316667960 [Accessed: July 5, 2021].

Baur, Nina; Mennell, Stephen & Million, Angela (2021). The refiguration of spaces and methodological challenges of cross-cultural comparison. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung / Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 22(2), Art. 25, http://dx.doi.org/10.17169/fqs-22.2.3755 [Accessed: July 3, 2021].

Bessel, Richard & Emsley, Clive (2000). Patterns of provocation: Police and public disorder. New York, NY: Berghahn Books.

Böhme, Gernot (1995). Atmosphäre: Essays zur neuen Ästhetik. Frankfurt/M.: Suhrkamp.

Böhringer, Daniela; Karl, Ute; Müller, Hermann; Schröer, Wolfgang & Wolff, Stephan (2012). Den Fall bearbeitbar halten: Gespräche in Jobcentern mit jungen Menschen. Opladen: Barbara Budrich.

Butler, Judith (2015). Notes towards a performative theory of assembly. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Daniel, Antje (2019). Ambivalenzen des Forschens unter Bedingungen (post-)dekolonialer Praxis. Forschungsjournal Soziale Bewegungen, 1, 40-49.

della Porta, Donatella; Andretta, Massimiliano; Mosca, Lorenzo & Reiter, Herbert (2006). Transnational protest and public order. In Donatella della Porta, Massimiliano Andretta, Lorenzo Mosca & Herbert Reiter (Eds.), Globalization from below: Transnational activists and protest networks (pp.150-195). Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press.

Francis, Sieraaj & Hardman, Joanne (2018). #RhodesMustFall: Using social media to "decolonize" learning spaces for South African higher education institutions: A cultural historical activity theory approach. South African Journal of Higher Education, 32(4), 66-80, http://dx.doi.org/10.20853/32-4-2584 [Accessed: July 5, 2021].

Gamson, William A. (1995). Constructing social protest. In Hank Johnston & Bert Klandermans (Eds.), Social movements and culture (pp.85-106). Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press.

Garfinkel, Harold (1967). Studies in ethnomethodology. Cambridge, MA: Polity Press.

Gerhards, Jürgen & Rucht, Dieter (1992). Mesomobilization: Organizing and framing in two protest campaigns in West Germany. American Journal of Sociology, 98(3), 555-596.

Gitlin, Todd (2003 [1981]). The whole world is watching: Mass media in the making and unmaking of the New Left. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

Glaser, Barney G. & Strauss, Anselm L. (1999 [1967]). The discovery of grounded theory: Strategies for qualitative research. New York, NY: Aldine de Gruyter.

Gukelberger, Sandrine (2018). Urban politics after apartheid. London: Routledge.

Griffero, Tonino (2014 [2010]). Athmospheres. Aesthetics of emotional spaces. Farnham: Ashgate.

Griffero, Tonino (2017 [2013]). Quasi-things: The paradigm of atmospheres. Albany, NY: State University of New York Press.

Hodes, Rebecca (2016). Briefing questioning "Fees must fall". African Affairs, 116(462), 140-150.

Juris, Jeffrey (2014). Embodying protest: Culture and performance within social movements. In Britta Baumgarten, Peter Ullrich & Priska Daphi (Eds.), Conceptualizing culture in social movement research (pp.227-246). Houndmills: Palgrave Macmillan.

Knoblauch, Hubert & Löw, Martina (2017). On the spatial re-figuration of the social world. Sociologica, 2, 1-27, https://www.rivisteweb.it/doi/10.2383/88197 [Accessed: August 27, 2021].

Knoblauch, Hubert & Löw, Martina (2020). The re-figuration of spaces and refigured modernity—concept and diagnosis. Historical Social Research, 45(2), 263-292, https://www.ssoar.info/ssoar/handle/document/66902?locale-attribute=en [Accessed: July 3, 2021].

Kula, Nancy C. & Marten, Lutz (2008). Central, East, and Southern African languages. In Peter Austin (Ed.), One thousand languages (pp.86-111). Oxford: The Ivy Press.

Low, Setha M. (2003). Embodied space(s): Anthropological theories of body, space, and culture. Space and Culture, 6(1), 9-18.

Meyer, Christian (2009). Rhetoric and culture in Non-European societies. In Ulla Fix, Andreas Gardt & Joachim Knape (Eds.), Rhetoric and stylistics. An international handbook of historical and systematic research (Vol. II, pp.1144-1158). Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter.

Meyer, Christian (2014). Die soziale Praxis der Podiumsdiskussion. Eine videogestützte ethnomethodologische Konversationsanalyse. In Johannes Angermuller, Martin Nonhoff, Eva Herschinger, Felicitas Macgilchrist, Martin Reisigl, Juliette Wedl, Daniel Wrana & Alexander Ziem (Eds.), Diskursforschung. Ein interdisziplinäres Handbuch (Vol. II, pp. 404-432). Bielefeld: Transcript.

Meyer, Christian & von Wedelstaedt, Ulrich (2017). Zur Herstellung von Atmosphären: Stimmung und Einstimmung in der Sinnprovinz Sport. In Larissa Pfaller & Basil Wiesse (Eds.), Stimmungen und Atmosphären (pp.233-262). Wiesbaden: Springer VS.

Oberzaucher, Frank (2014). Übergabegespräche. Interaktionen im Krankenhaus. Eine Interaktionsanalyse und deren Implikationen für die Praxis. Stuttgart: Lucius & Lucius.

Peterson, Lindsey; Radebe, Kentse & Mohanty, Somya (2016). Democracy, education and free speech: The importance of #FeesMustFall for transnational activism. Societies Without Borders, 11(1), 1-128, https://scholarlycommons.law.case.edu/swb/vol11/iss1/10 [Accessed: July 5, 2021].

Phillips, Kristine (2018). Protesters clash, arrests mount after toppling of Confederate statue at UNC-Chapel Hill. The Washington Post, August 25, 2018, https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/grade-point/wp/2018/08/25/protesters-clash-arrests-mount-after-toppling-of-confederate-statue-at-unc-chapel-hill/?noredirect=on&utm_term=.ea61c43f7aec [Accessed: March 22, 2019].

Radermacher, Martin (2018). "Atmosphäre": Zum Potenzial eines Konzepts für die Religionswissenschaft. Zeitschrift für Religionswissenschaft, 26(1), 142-194.

Riedel, Friedlind (2019). Atmosphere. In Jan Slaby & Christian von Scheve (Eds.), Affective societies. Key concepts (pp.85-95). New York, NY: Routledge.

Runkel, Simon (2018). Collective atmospheres. Phenomenological explorations of protesting crowds with Canetti, Schmitz, and Tarde. Ambiances Varia, 1-17, https://doi.org/10.4000/ambiances.1067 [Accessed: July 5, 2021].

Schmidt, Robert & Wiesse, Basil (2019). Online participant videos: A new type of data for interpretative social research?. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung / Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 20(2), Art. 22, http://dx.doi.org/10.17169/fqs-20.2.3187 [Accessed: August 26, 2021].

Schütz, Alfred (1945). On multiple realities. Philosophy and Phenomenological Research, 5(4), 533-576.

Schütz, Alfred & Luckmann, Thomas (1974 [1973]). The structures of the life-world. London: Heinemann Educational Books Ltd.

Seidman, Gay. W. (2000). Blurred lines: Nonviolence in South Africa. PS: Political Science and Politics, 33(2), 161-167.

Srubar, Ilja (1988). Kosmion: Die Genese der pragmatischen Lebenswelttheorie von Alfred Schütz und ihr anthropologischer Hintergrund. Frankfurt/M.: Suhrkamp.

Strauss, Anselm (2008 [1987]). Qualitative analysis for social scientists. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Tarrow, Sidney (1989). Democracy and disorder: Protest and politics in Italy, 1965-1975. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

Tarrow, Sidney (1994). Power in movement. Social movements, collective action and politics. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press.

Timm Knudsen, Britta & Andersen, Casper (2019). Affective politics and colonial heritage. Rhodes must fall at UCT and Oxford. International Journal of Heritage Studies, 25(3), 239-258.

van Leeuwen, Anouk; Klandermans, Bert & van Stekelenburg, Jacqueline (2014). A study of perceived protest atmospheres: How demonstrators evaluate police-demonstrator interactions and why. Mobilization, 20(1), 81-100.

van Leeuwen, Anouk; van Stekelenburg, Jacqueline & Klandermans, Bert (2016). The phenomenology of protest atmosphere: A demonstrator perspective. European Journal of Social Psychology, 46(1), 44-62.

Vershbow, Michela E. (2010). The sounds of resistance: The role of music in South Africa's anti-apartheid movement. Inquiries Journal, 2(06), 1-2, http://www.inquiriesjournal.com/a?id=265 [Accessed; July 5, 2021].

Waddington, P. David (2007). Policing public disorder: Theory and practice. Portland, OR: Willan Publishing.

|

Sandrine GUKELBERGER works at the Department of History and Sociology at the University of Konstanz as one of the principal investigators in the DFG-funded research project "Jugendbewegungen und der Wandel des Politischen" [Youth Movements and Political Change]. In her main research she focuses on urban theory, protest and social movement theory, postcolonial cultural studies, gender studies, and ethnographic methodologies. Her book "Urban Politics after Apartheid" was published by Routledge in 2018. |

Contact: Dr. Sandrine Gukelberger Universität Konstanz, AG Allgemeine Soziologie und Kultursoziologie, Fachbereich Geschichte und Soziologie, Fach 41 Tel.: +49-7531-883545 E-mail: sandrine.gukelberger@uni-konstanz.de |

|

Christian MEYER is Chair of general and cultural sociology at the University of Konstanz. Having conducted extensive fieldwork in Senegal on everyday life and village politics, he co-directs the DFG-research project on "Jugendbewegungen und der Wandel des Politischen" [Youth Movements and Political Change]. His research interests focus on social theory, phenomenological sociology and ethnomethodology, interaction, culture and practice, and qualitative methodology. His newest book is "Culture, Practice, and the Body" (Metzler, 2018). |

Contact: Prof. Dr. Christian Meyer Universität Konstanz, AG Allgemeine Soziologie und Kultursoziologie, Fachbereich Geschichte und Soziologie, Fach 41 Tel.: +49-7531-885020 E-mail: christian.meyer@uni-konstanz.de |

Gukelberger, Sandrine & Meyer, Christian (2021). Creating space by spreading atmospheres: Protest movements from a phenomenological perspective [44 paragraphs]. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung / Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 22(3), Art. 16, http://dx.doi.org/10.17169/fqs-22.3.3796.