Volume 23, No. 2, Art. 7 – May 2022

Asynchronous Online Photovoice: Practical Steps and Challenges to Amplify Voice for Equity, Inclusion, and Social Justice

Anna CohenMiller

Abstract: While researchers initially developed photovoice methodology as a means to hear voices of vulnerable populations and of marginalized experiences, using it in an online format has recently been adapted for application during the COVID-19 pandemic. In this article, I discuss implementing online photovoice in an asynchronous mode. I explore the potential of the methodology for equity, inclusion and social justice through an international study conducted with motherscholars (mothers in academia) who suddenly began guiding their children through online learning during the first wave of the COVID-19 pandemic. I describe the steps in the online photovoice study that was intended to amplify participant voice and the challenges faced. As such, I propose novel insights, practical tips, obstacles to avoid, and critical self-reflective questions for researchers interested in expanding their toolkit for qualitative social justice research.

Key words: asynchronous online photovoice; equity inclusion; social justice; rigid flexibility; participant voice; motherscholar; mothers in academia; COVID-19

Table of Contents

1. Same Boat, Different Storms

2. Photovoice

3. Photovoice Online

4. Learning From the Online Photovoice Study of Motherscholars: A Step-by-Step Process

4.1 Questions to consider when starting the project

4.2 How to identify and access potential participants?

4.3 How to collect the data in an asynchronous mode?

4.4 What can be learned from the data?

5. Contribution of the Study

6. Limitations

7. Recommendations

1. Same Boat, Different Storms

When the world faced the COVID-19 pandemic, those who were working and also had children were faced with an additional challenge to learn how to lead their children through online learning while working full-time from home. Considering that mothers take on a disproportionate role in raising children, when schools closed for face-to-face instruction during the pandemic, mothers were faced with further work for caregiving (GREGORY, 2020). The added work for women has been termed "unbridled" role conflict between work and family expectations (ADISA, AIYENITAJU & ADEKOYA, 2021, p.241) and for mothers as "untenable" responsibilities and expectations (COHENMILLER & IZEKENOVA, 2022; DEL BOCA, OGGERO, PROFETA & ROSSI, 2020). [1]

Because people have structured academic organizations around a male model of the ideal worker, the resultant system has led to creating a system perpetuating inequity for women and mothers in academia (SALLEE, WARD & WOLF-WENDEL, 2016). The academic workplace is constructed around this male model (COHENMILLER, 2018). While most academics faced changes to their daily life because of the pandemic, due to the historically patriarchal structure of higher education, women have had a unique experience. For example, Ellen KOSSEK, Tracy DUMAS, Matthew PISZCZEK and Tammy ALLEN (2021) conducted a study of over 700 women in science, technology, engineering and mathematics fields (STEM) during the pandemic, finding that the women developed various adaptations to adjust to the lack of work and home separation. The researchers described multiple examples of mothers in STEM who developed strategies such as concealing their motherhood while on video calls (e.g., removing any evidence of being a parent from their background) or the exact opposite, revealing their motherhood as the effort to conceal children's presence took extra effort. In more stereotypically patriarchal societies, such as Bangladesh, women's roles during the pandemic likewise took on additional responsibilities requiring added efforts and strategies (UDDIN, 2021). [2]

To refer to mothers working in academia, I use the term "motherscholars," which was first coined by Cheryl MATIAS (2011, 2022) and one I extend, such as in The Motherscholar Project. The term was created to purposefully combine the roles of mother and scholar into one term, advocating for the integration of two roles (mother, scholar). The pressure to continue working at a normal pace of a frequent adage, publish or perish, led to tremendous stresses and changes that are suggested to lead to excessive exacerbation of equity and inclusion in academia for years to come (COHENMILLER, 2020a). The simultaneous timeline in academia for women to reach tenure and have children overlap is tremendous (WARD & WOLF-WENDEL, 2012). Using the lens of Joan ACKER's (1990) theory of gendered organizations, researchers have shown challenges motherscholars face and ways to create more equitable and inclusive spaces, such as simple steps as recognizing the presence of mothers in the academic workplace (COHENMILLER, DEMERS, SCHNACKENBERG & IZEKENOVA, 2022). [3]

As someone who has studied motherscholars for many years, I have become an insider to many communities of mothers in academia around the globe. From these communities, I started hearing stories about the pressures and new obligations motherscholars were taking on during the pandemic. My position in living and working in Central Asia in an international community with previous experience in the United States included global communities of motherscholars and an added awareness to the role responsibilities of various multicultural contexts. The expectations, for instance for women living in Central Asia includes intense societal pressure to manage all childcare, housework, family (often including taking care of in-laws), as well as paid employment (COHENMILLER, SANIYAZOVA & SANIYAZOVA, 2019; TABAEVA, 2021) [4]

At some points, I heard stories firsthand, such as one that a former student shared about being a full-time teacher working from home along with her child who was learning full-time and her mother who lived with them, who was also a full-time teacher. Three people online streaming the internet and all speaking simultaneously in one house suggest structural obstacles that are not easily remedied, especially in comparison to someone else who may have the home to themselves while working. At other times I heard stories posted at motherscholar social media groups about lack of understanding, excessive pressure on timed responses, and meeting grant deadlines. [5]

While the COVID-19 pandemic affected the entire world, how it touched those working in organizations varied greatly (COHENMILLER & IZEKENOVA, 2022). As May FRIEDMAN and Emily SATTERTHWAITE (2021) articulated, COVID-19 impacted parents across gender, race, and class differently, referring to the pandemic as the "same storm, different boats" (p.53). Those working in academic institutions, depending on their position, found some flexibility in being able to continue their work while at home. Such distance or remote work meant that work could continue "as normal" but under new conditions. For those in faculty/professoriate positions who were teaching and researching, working from home meant adjustment to schedules, sometimes learning new online platforms, supporting students, and reconfirming research (COHENMILLER & LEVETO, forthcoming). For those in administrative/support roles, expectations for maintaining regular work schedules meant pressures such as being asked to respond to e-mails within minutes (COHENMILLER, 2020b). [6]

Yet, for those with young children at home, the apparent and superficial concept of quickly transitioning to working from home was interrupted by a reality of caretaking. Moreover, just as academic institutions were moving online, schools, including preschool through high school/secondary school, were also suddenly transitioning to online learning. However, a major difference was that while many in higher education institutions had some experience in online or hybrid teaching, those working in schools typically had none. These cascading effects of a sudden transition to online work and online education affected caretakers disproportionately (HIGGINBOTHAM & DAHLBERG, 2021), in particular, mothers who primarily took on these roles, including during the pandemic (COHENMILLER & IZEKENOVA, 2022; COHENMILLER & LEVETO, forthcoming; O'REILLY & GREEN, 2021). Using a feminist lens such as emphasized by Andrea O'REILLY and Fiona GREEN (2021), I recognize how societies, cultures, and organizations are gendered. The experiences of those within these contexts are therefore also gendered, including for motherscholars during the pandemic. [7]

As a mother in academia, who teaches teachers—a motherscholar—I experienced the reality of the sudden disruption of moving into one living space with two young children and a spouse, all trying to learn and teach and work online. I struggled even though I was one of the fortunate ones: we have multiple physical spaces in the house to move around to, high-speed internet, and my spouse works part-time and takes on a good amount of the caretaking responsibilities. In comparison, the students I worked with were schoolteachers and also school leaders living in small houses with multiple children and adults, all trying to stream full-time throughout the day while using inconsistent internet. And these challenges only speak to the work obstacles and not the emotional, physical, or spiritual toil of facing health crises. [8]

Yet, the discourse of many workplaces was that each employee needed to ensure they were giving their all, that they weren't "on vacation." I started to see such comments in many places and from many people, all seeming to miss the experience of people's lives, especially mothers who were taking on the added roles of full-time guidance of children's learning. I saw that those I worked with were struggling with far greater obstacles, too—the high school teacher living with her two children who were learning online and her mother who was teaching online from the same house. These comments echo literature specific to academia during the pandemic. For instance, Carolyn COYNE, Jimmy BALLARD and Ira BLADER (2020) draw lessons about US university closures, offering recommendations for future shut-downs, such as clear communication. And focusing on gender in higher education during the pandemic, Meredith NASH and Brendan CHURCHILL (2020) studied surveys in research conducted across Australian university responses relating to remote working and caring responsibilities. The researchers pointed to key information demonstrating a lack of communication and recognition of including women and mothers in academia, "[w]e argue that COVID-19 provides another context in which universities have evaded their responsibility to ensure women's full participation in the labour force" (NASH & CHURCHILL, 2020, p.833). [9]

The study under discussion here emerged to uncover the reality of life during COVID-19 quarantine for mothers in academia who were also taking on these new responsibilities/jobs. I started to ask myself: How can the experiences I'm hearing be aligned with what the workplace is saying? What is actually happening on the ground, in people's homes? To understand the reality of motherscholars' lives, it became apparent that seeing into their home life would be necessary. During quarantine, people were stuck in their homes, to varying degrees, even some in "lockdown" not allowed to leave except for specific reasons. My experience fell into this second category. [10]

While I focus on academia, I recognize this is a privileged profession, often allowing a lot of flexibility in structuring our time. I realize the benefit I had in my academic position during such upheaval. I am grateful (which I also heard from the women I spoke with) that we were not faced with more significant obstacles. However, for some involved in academia, such as administrative staff, I heard stories of women being told they had to respond to all e-mails within ten minutes and to "[r]emember that this is not a vacation" (COHENMILLER, 2020b, p.16). I heard from others in various countries about pressures to keep working despite family members being gravely sick. Such anecdotes align with literature on the topic of mothers in academia (ANDERSON & LAFRENIÈRE, 2021; BROMWICH, 2021; MARTÍNEZ & ORTÍZ, 2021). [11]

To better understand the "reality" of how motherscholars worldwide were experiencing the pandemic, I began the photovoice study. From previous studies with motherscholars, I knew this population often does not have time for video conferencing and instead prefer to share data asynchronously because of their limited time and multiple roles (COHENMILLER, DEMERS & SCHNACKENBERG, 2020). Thus, I decided to implement an asynchronous online photovoice study. I applied for ethical review in April 2020 to conduct a photovoice study of motherscholars during quarantine and lockdown (the terminology and restrictions varying dependent on the country context). Participants identified as mothers and worked in academia while also guiding children through online learning during the pandemic (COHENMILLER & IZEKENOVA, 2022). Soon after receiving ethical approval, I was able to add a researcher to the team, and we collected data from May through September 2020 through purposeful sampling. This strategy allowed us to recruit specific individuals meeting our inclusion criteria. Such an approach was recommended by Sharan MERRIAM and Elizabeth TISDELL (2016) when "the investigator wants to discover, understand, and gain insight and therefore must select a sample from which the most can be learned" (p.96). (I discuss the inclusion criteria further in Section 4.) [12]

In this article, I provide an overview of the study, beginning with a discussion of photovoice in general (Section 2) and photovoice online (Section 3). Then I move into the description of the online photovoice study of motherscholars which details the processes, imagery, and select findings to highlight the key concepts (Section 4). After this I note the study's contribution (Section 5) and limitations (Section 6). Lastly, I end with recommendations for asynchronous online photovoice to amplify voice for equity, inclusion, and social justice, incorporating questions to ask ourselves as researchers to facilitate this process through critical self-reflection (Section 7). [13]

Photovoice is a participatory action research methodology grounded in theoretical underpinnings of emancipatory practice. Participants are actively engaged in developing the research, data collection, analysis, and sharing of findings. To create a photovoice methodology, Caroline WANG and Mary Anne BURRIS (1997) extended their previous work with "photo novella" (p.369) and working in rural communities to facilitate voice for vulnerable populations, demonstrated findings to a larger audience. While WANG and BURRIS noted how photo novella was "commonly used to describe the using photographs or pictures to tell a story or to teach language" (ibid.), photovoice takes on an expanded direction: "(1) to enable people to record and reflect their community's strengths and concerns, (2) to promote critical dialogue and knowledge about important community issues through large and small group discussion of photographs, and (3) to reach policymakers" (p.370). [14]

Photovoice offers many opportunities to empower participants and integrate social justice into the center of the work. For example, Marie-Anne SANON, Robin EVANS-AGNEW, and Doris BOUTAIN (2014) inspected photovoice studies from 2008-2013, looking specifically to see how social justice was integrated across the 30 studies. They found that all the studies emphasized social justice awareness, with a limited number focused on reducing or transforming social justice. As I described about photovoice: "The theoretical framework for a photovoice methodology (which at times is referred to in the literature as a method) draws from critical educational theories, feminist theories, and more recently from emancipatory and decolonial theories" (COHENMILLER & IZEKENOVA, 2022). [15]

In using a critical feminist lens in photovoice, researchers could focus on topics of gender equity and inclusion. Sharing the results is a fundamental aspect of the photovoice process, advocating with the community. Such a public show demonstrates the topic for others to see and better understand, often focusing on policymakers. The methodology can also be used as a participatory research process focusing more on photo-elicitation as a method (LIEBENBERG, 2018) instead of integrating participants throughout the study itself. In photo-elicitation, researchers can bring photos to have participants discuss. For example, following a participatory research approach (instead of adding in "action"), participants might be involved in data collection and analysis but not necessarily in the creation of the study, the formation of research questions, or dissemination decisions. [16]

Photovoice, initially developed in particular for use in health fields, has also been incorporated to study various topics throughout the years, focusing on understanding experience and perceptions. For example, researchers have worked with communities internationally, such as with children in Kenyan orphanages (JOHNSON, 2011), with women with disabilities (MACDONALD, DEW & BOYDELL, 2020) to address academic knowledge (ROGER, 2017), engage youth participation (BUTSCHI & HEDDERICH, 2021; LOFTON, NORR, JERE, PATIL & BANDA, 2020; WOODGATE, ZURBA & TENNENT, 2017), and enhance awareness and knowledge (BRÄNNSTRÖM, NYHLÉN & GÅDIN, 2020; SPRAGUE, OKERE, KAUFMAN & EKENGA, 2021). Recently, photovoice has been altered for a new direction termed "rapid photovoice" (RPV) as an emancipatory methodology (LUESCHER, FADIJI, MORWE & LETSOALO, 2021). LUESCHER et al. adjusted photovoice to fit the constraints of their timing and funding, developing an approach integrating social media. They centered Freirean social justice and suggested: "RPV ... may be viewed as an innovative, variant of the photovoice methodology—and, as such, may inspire other researchers to be creative and adaptive in designing a research methodology that suits their project" (p.13). [17]

Adapting photovoice online is a burgeoning topic, especially regarding the COVID-19 pandemic. However, even before the pandemic, researchers were examining how participants could be reached with online photovoice. For example, community psychologists Lauren LICHTY, Mariah KORNBLUH, Jennifer MORTENSEN, and Pennie FOSTER-FISHMAN (2019) created an online photovoice study with youth. They found it was an "empowering method, including increased self-competence, emergent critical awareness, and a cultivation of resources for social action" (p.5). They pointed out that online photovoice can be an effective means for bridging geographic distances, working with participants who value technology, and reducing costs. [18]

Others have also explored online photovoice research, such as Laura LORENZ with the organization PhotoVoice Worldwide. As a result of the pandemic, online versions of photovoice continue to emerge as powerful reminders about reaching marginalized populations and advocating for socially just changes with the community. For instance, Ahmet TANHAN and Robert STRACK (2020) developed an approach for photovoice online they term "Online Photovoice." While they collected data online with participants, they came together as a community for dinner to celebrate and share the outcome of their work. [19]

Researchers have also emphasized the methodological lessons and cautions of online photovoice adaptation. For example, Meagan CALL-CUMMINGS and Melissa HAUBER-ÖZER (2021) emphasized focusing on the theoretical and practical application: "we must remember the emancipatory goals of participatory inquiry, always relying upon and anchoring our methodological decisions in the ontologies and epistemologies of genuine participation that undergird photovoice" (p.3214). [20]

Another example of online photovoice can be seen in the work of Nadia RANIA, Ilaria COPPOLA, and Laura PINNA (2021). They analyzed how photovoice can be "successful" during COVID times to understand the experiences of young adults. The researchers found essential factors to consider in creating small groups in photovoice online to improve communication and rapport, standard practices such as turn-taking, and inclusion of participants by ensuring everyone could interact using the online tools. [21]

Although interactions are different in physical spaces than online ones, some approaches for adapting photovoice online attempt to integrate similar levels and time of interaction as a face-to-face approach. For instance, researchers can incorporate online focus groups and online galleries to mimic face-to-face interactions. However, other researchers adapted photovoice online in unique ways, which sought not to replicate face-to-face photovoice studies but instead incorporate asynchronous interactions (DOYUMGAÇ, TANHAN & KIYMAZ, 2020; HISCOCK, 2020; TANHAN & STRACK, 2020). Such asynchronous interactions help adjust to the needs of participants. [22]

Photovoice offers excellent opportunities to understand experiences firsthand, but criticism of it also exists. Without an emphasis on the theoretical underpinnings of social justice, photovoice outcomes can lose their purpose and power, such as becoming watered down or reinforcing positivistic views (SHANKAR, 2016), incorporating adaptations without sufficient training (RANIA et al., 2021), or lacking a transformative process (CALL-CUMMINGS & HAUBER-ÖZER, 2021). [23]

4. Learning From the Online Photovoice Study of Motherscholars: A Step-by-Step Process

In this study, I adapted photovoice for online use in an asynchronous mode with the specific intent to demonstrate and amplify the voices of those overlooked. I developed the framework for the study, inviting a PhD student with whom we have presented about adapting photovoice (COHENMILLER & IZEKENOVA, 2020) and written about the findings of this study (COHENMILLER & IZEKENOVA, 2022). [24]

In the traditionally male-model of academia, motherscholars are a marginalized and vulnerable group. Further, as described by Andrea O'REILLY (2021), mothers are broadly marginalized and vulnerable in a patriarchal society. As such, O'REILLY argued for extending feminist thinking to include matricentric feminism, which centers the multiple oppressions of women in a patriarchal society alongside the recognition of the oppression of mothers. O'REILLY's (2021) matricentric theory built upon feminist theories adding in the essential and unique experience of mothers. [25]

Following previous research in adapting photovoice online to address social justice issues (e.g., CALL-CUMMINGS & HAUBER-ÖZER, 2021; LUESCHER et al., 2021), I saw the adaptation as a means to address the needs of the particular community. Such an approach is echoed in work conducted by Glenis MARK and Amohia BOULTON (2017) in using an altered version of photovoice to "indigenize" research in their research with Māori people. [26]

My work was framed by centering the importance of culture, society and role, drawing from Lev VYGOTSKY's (1978) sociocultural theory, Dorothy HOLLAND, William LACHICOTTE, Debra SKINNER, and Carole CAIN's (1998) "figured worlds" (p.51), and Andrea O'REILLY's (2021) matricentric theory. VYGOTSKY (1978) described how a sociocultural theoretical lens could center cultural context, recognizing the ways people interact in the world. In this way, I saw that photovoice could help complement and showcase the lives of those involved through the participatory research approach. HOLLAND et al. (1998) discussed the concept of "figured worlds," the intersecting ways in which our selves and roles interrelate as we "figure" who we are in relation to one another in our particular social context, one that evolves and changes based upon those we interact with. These theoretical frames provided a lens to center the experiences of motherscholars within the figured worlds of academic organizations and their homelives. Further, I began the study with an awareness that women's understanding and conceptualization of themselves as mothers and motherscholars would vary based upon the cultural context of their individual lived experiences and the patriarchal societies in which they have lived. These overlapping ideas affect how people see their roles as mothers and academics. [27]

The following details the steps taken to adapt photovoice for online use in the hopes others might learn valuable insights for conducting studies, learn from the challenges, and recognize the potential for uncovering structural inequalities and promoting socially just solutions while remaining “rigidly flexible” (COHENMILLER et al., 2020) to the fundamental theoretical underpinnings of photovoice. [28]

4.1 Questions to consider when starting the project

Fundamental to the process of any study is understanding the purpose and goals. For photovoice, I recognized that the social justice foundation is also vital. Thus, multiple questions related to socially just practice can be considered for someone interested in applying online photovoice in an asynchronous mode. Such questions could include the following:

How is social justice integrated into the study?

Whose voices are being amplified? And whose voices are being excluded?

How can the data be collected in a way that is simple for all participants?

Will there be online interaction between participants?

How will the findings be shared at the end of the study? (I purposefully use the phrase "sharing the findings" in place of "disseminating the findings" as a feminist research choice to move away from sexist academic language centering men's bodies, see e.g., Bridget CRAWFORD's (2014) on "seminal," drawing from Jenny DAVIS's (2014a, 2014b) on the topic and the parallel Latin root of seminal and disseminate according to Merriam-Webster's dictionary.)

How can all these aspects be integrated into an institutionally approved research study? (For example, while some photovoice studies allow images of people's faces as a step towards emancipatory action, we decided in the cultural context in which we work that such a request might delay the review process and slow data collection.)

How might the study potentially impact the real-world lives of participants? [29]

These types of questions helped guide the development of this study. The following identifies how I thought about each question. Social justice was integrated from the beginning, such as through the theoretical lenses of the research, which purposefully consider the process and outcome of the research. The voices to amplify were motherscholars, a population marginalized in academia. However, I recognize there remain those whose voices are not heard; those without internet access would not have been able to take part in the study. Such lack of access to technology and inclusion is a significant issue internationally for qualitative social justice research. [30]

I developed a simple Google form for data collection as a simple method for responses in a common platform known internationally. I decided to collect data asynchronously, not requiring participant interaction. From previous research with motherscholars, I had learned about the time demands making it challenging to find synchronous times for data collection (COHENMILLER et al., 2019). The sharing of data and findings was indicated for both academic and public formats (see Photovoice: Motherscholars during Quarantine). I included each step within the ethical review application at our university. [31]

Initially, the data collection was planned to be anonymous—for the Google form not to collect personal e-mails. However, I found participants were contacting me after they were submitting their form or to ask if they could submit information via e-mail instead. As such, I returned to the ethical review board to request an amendment allowing for people to add their names and e-mails and to provide information about themselves via e-mail. Participants were notified in the consent form that their names would not be revealed and instead pseudonyms would be provided, and any information identifying them in the photos would be masked. One person specifically requested to have her name remain along with the picture of herself. She explained that by showing herself and her name, she was making a statement again a history of being silenced, stating, "we have been historically erased as knowing-subjects we would like the picture to remain as it is with the parts of our faces visible still visible." [32]

While e-mailed responses were an unexpected change, similar to a previous study I had conducted with motherscholars, incorporating rigid flexibility to adapt the process of data collection was necessary to facilitate participation (COHENMILLER et al., 2019). In my previous study, motherscholars requested to detail their experiences via text messages in both synchronous and asynchronous means, and in this study, multiple motherscholars asked to use e-mail. From these studies, it appears that when there are constraints on time and multiple role demands such as experienced by motherscholars, options for asynchronous data collection are essential. [33]

As a final step, the impact for the real-world lives of participants centered on raising awareness of the experiences and the potential issues of equity and inclusion in academic organizations. At the time of writing this article, I have published a website with photos and descriptions of which participants are aware. I invited all participants to respond if they were interested in coming together online for an informal discussion and virtual "coffee chat." Three people have answered, and we plan to meet one another online. The limited number of participant responses suggests continued demands on participants' lives as motherscholars during the pandemic, which still requires online learning and working from home in some parts of the world. [34]

Additionally, as many participants are from Kazakhstan, where Instagram is a primary social media outlet, I have begun an Instagram account related to this project. Finally, I plan to incorporate an exhibit of the motherscholars experience related to International Women's Day through printing photos for a university exhibit and a virtual exbibit at Gender Forum. The Consortium of Gender Scholars. The combination of these steps is intended to raise awareness and stimulate discussion of the obstacles motherscholars have faced and to create equitable and inclusive practice and policy to address future re-entry to more "normal" times. [35]

4.2 How to identify and access potential participants?

I was interested in participants who aligned with the following inclusion criteria:

identified as a mother;

worked in an academic organization;

was a caretaker for a child(ren) suddenly learning online, during the abrupt transition to working/learning from home during the pandemic. [36]

As the study began and many motherscholars started to participate, I invited another researcher to join the team, a PhD student (IZEKENOVA) I regularly worked with on topics related to gender (e.g., COHENMILLER & IZEKENOVA, 2020, 2022). We both live and work in Kazakhstan, in Central Asia, and previously I lived and worked in the United States. As mothers ourselves, we knew of this population well and were hearing from formal and informal international networks, in particular in Central Asia and the US, about their struggles to be heard and seen. In the following sections, I thus switch in voice from the description of the study that I developed to the data collection that was implemented as a team. [37]

To identify participants, we turned to social media networks. Specifically, we recruited them from Facebook groups in which we were members focusing on women and mothers in academia. We were insiders to these groups, having been members for months to years depending on the group. Being an insider allowed us to already understand the common practices of each Facebook group and the accepted interactions and policies, including recruitment for research studies. Yet, as we posted the recruitment invitation (Figure 1), we recognized a move along the "spectrum" of an insider to a potential outsider (COHENMILLER & BOIVIN, 2021), as our role shifted to the researcher.

Figure 1: Sample Facebook recruitment invitation [38]

4.3 How to collect the data in an asynchronous mode?

We delineated inclusion criteria that assumed the participants had internet access. However, their level of comfort and knowledge with various online programs was not known. Hence, I developed the data collection to be as user-friendly and straightforward as possible. I used a Google form to guide participants through the photovoice process. All participants chose to include their name and e-mail except one person who did not include contact information. All names except the one person who specifically requested her name and photo to show herself were changed according to the ethical research approval at our university. [39]

In developing the Google form, we gathered multiple aspects related to background information. For instance, we asked motherscholars to identify their geographic location, position in academia, number of children learning online and whether it was a new occurrence for online learning, questions about family structure (e.g., who was the primary caretaker and who lives in the home), if the children had any special needs and if there was anything else important to know about the children to better understand their reality. [40]

The request for sharing a photo included the following open-ended questions:

Describe your photo: What is happening in your picture?

Why did you take a picture of this?

What does this picture tell us about your life?

How can this picture provide opportunities for us to improve life?

Is there anything else you'd like to share? (e.g., about your reality, about your experience, or just something to highlight for others to hear) [41]

4.4 What can be learned from the data?

A key aim of the research study was to amplify voice and identify structural inequalities to improve academia or the lives of motherscholars. During the asynchronous photovoice study, 68 motherscholars from across the globe participated by sharing photos and descriptions about their lives while guiding children through online learning during quarantine/lockdown. Most participants were from the United States and Kazakhstan, the two locations where my co-author and I have spent most of our careers living and working. Other countries represented included Australia, the Philippines, South Korea, Hungary, Ukraine, Lebanon, the UK, and Ireland. Motherscholars identified their position/roles as ranging across the academic "pipeline" from graduate student to senior lecturer/full professor and administrative leadership roles. [42]

Across the study, 20 participants identified their children as having special needs, with another 15 offering additional specifics. For example, Rachel (pseudonym provided for all participants unless otherwise noted) said, "[m]y youngest has an anxiety disorder," Holly sharing "[m]y son is high-risk for COVID-19 due to asthma." She continued to explain,

"I am the primary breadwinner and we have no family where we live. My husband is an immigrant and I am the child of immigrants so our network in the US are friends mostly. We don't live near them bc of academia. We are very alone." [43]

The photographs offered deep insights into the experiences of being a motherscholar at home during quarantine/lockdown while also guiding children through online learning. The photos and descriptions demonstrate a conflict between personal agency and a focus on being hopeful and grateful and the recognition that there is a lack of academic institutional practice and policy to "facilitate success" for motherscholars (COHENMILLER et al., 2022). [44]

Assistant professor Karly in the United States had two children in grades 6 and 7. She mentioned that her son in 7th grade was on the autism spectrum. Karly said the following of her photo (Figure 2):

"It's my daily reality 8am-1pm. I have a hard time helping both of them at the same time. Caleb needs more help, but Abby needs help sometimes as well. She is more likely to get behind in her work than Caleb because I need to help him so much. It's hard to keep them both focused on their work. I feel like people making decisions about online school don't see the parent end. It's not as easy as getting the children online. There's [sic] tensions, especially when you have more than one child. I feel like I can't do all of my jobs well at the same time. Either I'm a good mom/home schooler, or a good academic. I've been unsuccessful at doing both." [45]

She illustrated how the picture might help motherscholars and academic organizations understand:

Focus on your health even in the chaos. It is our single greatest asset, and we have to protect it. Employers who are not empathetic to families must do better. The academia allows for flexibility, which can be great for working parents, but more has to be done to ensure our well-being is protected. I was struggling before the pandemic, and I honestly don't know if I can stay in academia and be a present mom. My kids often go to my husband for most things. Publish or perish has to die because I'm not missing out on my family because of a manuscript or grant. [46]

These comments provided important insight connected to how emancipatory research can work. Such feedback can help lead to policy outcomes that could affect socially-just changes for motherscholars.

Figure 2: Shared dining table and work space [47]

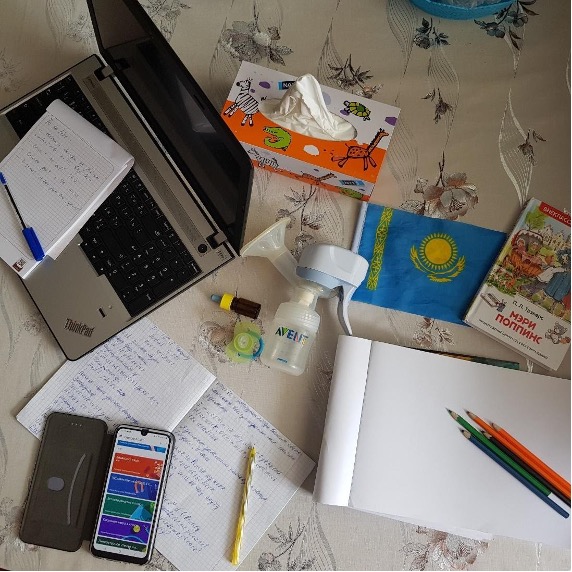

Yelena in Ukraine was an assistant professor with two children, one who was in the first level (age 3) and the other was in middle school (age 11). She pointed out that this picture was selected for two reasons: "1) I wanted to have a memory of this 2) I wanted to have an illustration of what the triple load of mothers looks like" (Figure 3).

Figure 3: Daily Zooming—teaching and children [48]

Yelena continued to say:

"I conduct seminars for my students online. This picture can tell that I have to cope independently with any challenges.

This picture may make someone think about what should be changed in their approach to working mothers. I would also like attention to be paid to the fact that mothers have an extra (and extreme) unpaid load in a pandemic

During the pandemic, I acutely felt how unfairly distributed expectations. I must provide distance education to my students and my child, as well as second child supervision. And I must at the same time be competitive in academic life. The university leadership has already promised me twice to provide the position of assistant professor. However, this has not yet happened. And this is again postponed due to the fact that the university has not changed the procedure for the competition and submitting documents from offline to online

This picture may make someone think about what should be changed in their approach to working mothers. I would also like attention to be paid to the fact that mothers have an extra (and extreme) unpaid load in a pandemic." [49]

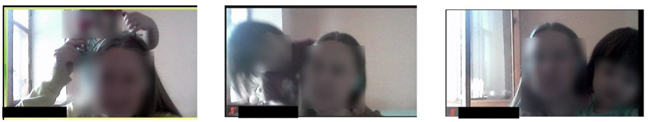

Yamina in Kazakhstan was an academic manager and had three children including a newborn, a preschooler, and a fourth grader. She said this photo described items of an everyday routine, "elements of our life" (Figure 4):

"I work from home, and I also help my son with his classes, and my toddler loves to be involved. Moreover, I'm breastfeeding my newborn son and I do my best to take care of him as well. It is a picture of a mother who deals with work, motherhood and tries to fit in 24 hours all the duties.

No need to be a perfect, you can only try. Try to make everything as simple as possible."

Figure 4: Items of daily life [50]

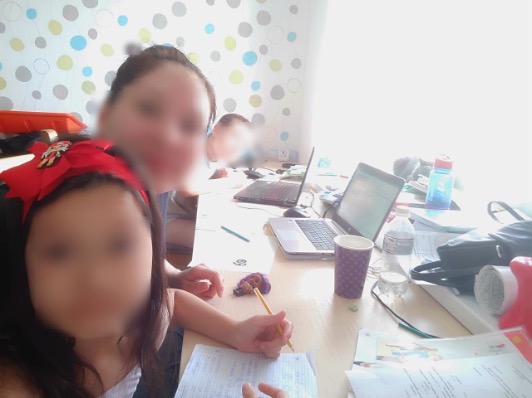

Zarina, a research assistant working in Kazakhstan, had a third and fifth-grade child learning online. The figure showed "[m]e and my kids are sitting together in the long table and studying/working simultaneously" (Figure 5):

"I took this picture to capture this moment when I started to experience the unique level of stress and studying for 3 people at the same time. As a mother in academia I experience a greater extend [sic] of responsibilities, housework, homework and all borders between professional/academic/personal lives have been diminished due to pandemic.

I hope the university and policy makers will understand the difficulties of motherscholars and implement some policies for improvement, provide funding for supporting mothers."

Figure 5: Studying and working simultaneously [51]

Molly was an assistant professor in the United States, with a child in kindergarten. She mentioned that her daughter had anxiety, and the photo showed "the lack of privacy and personal space even when working. I feel like this shows a typical day” (Figure 6).

Figure 6: No privacy or personal space [52]

She continued on to describe her selection of photo:

"My daughter is sitting right next to me/on me while I work on my laptop, doing ABC Mouse on her tablet with my dog sitting on my feet. You can see her empty meal plate on the tv table next to us. She wants to be in the same room/sit next to me all the time and so does the dog. Privacy and personal space are hard to find. We're both in our PJs." [53]

Molly extended upon her description:

"This picture shows survival mode. I have a lot of work to do but have to attend to a child at the same time. I'm a single mom. Before COVID I could pay for childcare and send my daughter to school, I don't have those options anymore." [54]

Others spoke specifically to the process of describing their experience as part of the project. Roxanne described:

"I think talking (writing) about it has helped. I also think it's important for us to reach out to another and let us know that we're not alone. My life is pure and utter chaos right now. But I'm still standing, we're still getting things done, we still love each other, and we'll be okay. Maybe putting that out there, letting other academic mamas know that everything is a literal and figurative mess right now, will help them feel better about their own chaos. And I think seeing others will help me feel better about my own." [55]

Ainur pointed out how the study helped her and how she wanted others to understand:

"I am glad to express my thoughts and feelings about the difficulties that working mothers at the academy experience. I would like the bosses and colleagues to understand how women and children are busy and take this into account when setting up any deadlines and meetings." [56]

These examples vividly show the potential for asynchronous online photovoice to demonstrate participant reality, which can impact their situation, such as raising awareness to social justice issues and offering a chance to speak to issues of equity and inclusion in academic organizations contributing to socially-just policy change. [57]

This article addresses an essential aspect of conducting qualitative research during socially distanced times. To respond to the cultural and contextual needs of participants, we adapted photovoice for both online use and also for an asynchronous format with special recognition of the need to undergird the study through an emancipatory and social justice lens (CALL-CUMMINGS & HAUBER-ÖZER, 2021). The study adds an important contribution to the literature on photovoice that aimed to maintain a focus on social justice and emancipatory processes. It offers ideas for other researchers and practitioners to consider, for instance, when working with communities with limited time or resources to access synchronous online video for online photovoice. Thus, there is potential for asynchronous online photovoice to level the playing field in providing methodological socially just opportunities for more people to share their experiences and lived realities, especially during crisis and upheaval where communities may have less contact. [58]

In line with online photovoice galleries, there is potential to showcase participant experiences on websites, social media, and conferences (ibid.). A final step of the project was to augment the website and social media presence at the international 2022 Gender Forum, organized by The Consortium of Gender Scholars. Through such an added step, the aim was to provide further insight for community members and academic organizations to consider socially-just solutions to facilitate success for motherscholars during pandemic times. [59]

There were times when participants provided some information on the Google form but left out other parts. Not including an e-mail, for example, meant there was no way to follow-up to check on their responses as a part of member checking. In this study, the findings were posted on social media piecemeal at the end of the study. Considering the nature of the pandemic and the multiple waves and issues of equity and inclusion in the multiple returns to academic life, having a quicker sharing of findings could have helped showcase the experiences for others, academic organizations, and policymakers. For our team, we were faced with similar obstacles faced by the motherscholars in this study, the multiple roles of full-time work and/or PhD studies plus guiding children through online learning during quarantine and lockdown. At the time of writing this article, the findings of this study continue to be posted on social media and a website. While online photovoice studies can include a face-to-face element (TANHAN & STRACK, 2020), there was no such chance in this study because of the geographic disparate locations of participants. However, we sent an e-mail to participants to invite them to an online opening and a virtual coffee, although most did not respond. [60]

Although most participants responded clearly to the questions on the Google form, there was an instance where someone said she was unclear about one question. Moreover, after reading through all participants' descriptions, as a research team we became aware that the use of a specific phrase may have been construed differently based upon cultural contexts. While I went into the study with the recognition of varied cultural context, figured worlds, and marginalized experiences of motherscholars, we nonetheless faced an unexpected finding. In the Kazakhstani context, a question about children with special needs could have been misconstrued as only referring to an extreme disability, which offers insight to why no Kazakhstani motherscholars noted any special needs of their children even though almost half of all them described otherwise. For example, they mentioned children having anxiety disorders, extreme asthma making it hard to leave the house during the pandemic, mild autism, or being gifted and talented. [61]

When physical access to participants and communities is suddenly removed or when there is no time to meet, applying photovoice in an online asynchronous format focusing on emancipation and social justice can address the need for rapid response, offering an essential role in uncovering structural inequalities and amplifying participant voice. The following are key recommendations we have identified from our experience of conducting an asynchronous online photovoice study. We have organized the recommendations as critical self-reflective questions to ask oneself as a researcher (see Table 1)—as such questions offer a chance for foreground equity, inclusion, and social justice in qualitative research (COHENMILLER & BOIVIN, 2021).

|

Topic |

Question |

|

Social justice |

How am I foregrounding social justice in the asynchronous online photovoice study? |

|

Voice |

Whose voices might I overlook in data collection? What steps can be used to remedy this? |

|

Cultural context |

How do the questions I am planning to ask reflect the cultural context? How have I checked if the meaning intended by the questions reflects those I am asking? |

|

Ethics |

What decisions are being made about the use of names and faces for the project (e.g., confidentiality regarding having focus groups or adapting for individual sharing)? And what justification can I explain to the ethical review board about either direction (e.g., blinding names/faces, showing names/faces)? |

|

Sharing findings |

At what point in the study do I plan to start sharing the findings (e.g., images, descriptions)? What is the benefit of waiting or beginning the process early (as centered on social justice)? |

|

Impact |

How am I considering the impact of the study? In particular, how can I center the benefits for participants taking part of the study? |

Table 1: Critical self-reflective questions to foreground equity, inclusion and social justice [62]

A huge thank you to all the motherscholars who were a part of this study, for sharing your lives and explaining your realities to move towards a more socially just future in academia. Thank you further to the insightful comments from the FQS editorial team, in particular Katja MRUCK for her overall vision for the Journal and mentoring of qualitative researchers.

Acker, Joan (1990). Hierarchies, jobs, bodies: A theory of gendered organizations. Gender and Society, 4(2), 139-158.

Adisa, Toyin Ajibade; Aiyenitaju, Opeoluwa & Adekoya, Olatunji David. (2021). The work-family balance of British working women during the COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of Work-Applied Management, 13(2) 241-260, https://doi.org/10.1108/JWAM-07-2020-0036 [Accessed: February 25, 2022].

Anderson, Gilian & Lafrenière, Sylvie (2021). "Who cares?" Women's and mothers' employment in caring industries during the first wave of COVID-19. In Andrea O'Reilly & Fiona J. Green (Eds.), Mothers, mothering, and COVID-19: Dispatches from the pandemic (pp.65-82). Bradford: Demeter Press.

Brännström, Lotta; Nyhlén, Sara & Gådin, Katja Gillander (2020). Girls' perspectives on gendered violence in rural Sweden: Photovoice as a method for increased knowledge and social change. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 19, 1-19, https://doi.org/10.1177/1609406920962904 [Accessed: February 15, 2022].

Bromwich, Rebecca J. (2021). Mothers in the legal profession doubling up on the double shift during the COVID-19 pandemic: Never waste a crisis. In Andrea O'Reilly & Fiona J. Green (Eds.), Mothers, mothering, and COVID-19: Dispatches from the pandemic (pp.131-140). Bradford: Demeter Press.

Butschi, Corinne & Hedderich, Ingeborg (2021). How to involve young children in a photovoice project. Experiences and results. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung / Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 22(1), Art. 5, http://dx.doi.org/10.17169/fqs-22.1.3457 [Accessed: January 5, 2022].

Call-Cummings, Meagan & Hauber-Özer, Melissa (2021). Virtual photovoice: Methodological lessons and cautions. The Qualitative Report, 26(10), 3214-3233, https://doi.org/10.46743/2160-3715/2021.4971 [Accessed: January 5, 2022].

CohenMiller, Anna (2018). Creating a participatory arts-based online focus group: Highlighting the transition from DocMama to Motherscholar. The Qualitative Report, 23(7), 1720-1735, https://doi.org/10.46743/2160-3715/2018.2895 [Accessed: February 28, 2022].

CohenMiller, Anna (Ed.) (2020a). Addressing issues of equity during and after COVID-19: Recommendations for higher education institutions and general information, https://bit.ly/3jLclX7 [Accessed: February 28, 2022].

CohenMiller, Anna (2020b). Spiraling. Academic motherhood and COVID-19. Journal of the Motherhood Initiative for Research and Community Involvement, 11(2), 9-20, https://jarm.journals.yorku.ca/index.php/jarm/article/view/40604/36775 [Accessed: February 28, 2022].

CohenMiller, Anna & Boivin, Nettie (2021). Questions in qualitative social justice research in multicultural contexts. London: Routledge.

CohenMiller, Anna & Izekenova, Zhanna (2020). Adapting photovoice for online use during times of disruption: Addressing issues of equity and inclusion in higher education. Presentation, NVivo Virtual Conference "Qualitative Research in a Changing World", virtual, September 23-24, 2020, http://dx.doi.org/10.13140/RG.2.2.18500.24961 [Accessed: February 28, 2022].

CohenMiller, Anna & Izekenova, Zhanna (2022). Motherhood in academia during the COVID-19 pandemic: An international online photovoice study addressing equity and inclusion in higher education. Innovative Higher Education.

CohenMiller, Anna, & Leveto, Jess (forthcoming). The impact of the pandemic on academic mothers: Integrating photovoice and surveys to imagine more equitable and inclusive higher education organizations. In Anna CohenMiller, Tamsin Hinton-Smith, Fawzia Mazanderani & Nupur Samuel (Eds.), Leading change in gender and diversity in higher education from margins to mainstream. London: Routledge.

CohenMiller, Anna; Demers, Denise & Schnackenberg, Heidi (2020). Rigid flexibility in research: Seeing the opportunities in "failed" qualitative research. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 19, 1-6, https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/1609406920963782 [Accessed: January 10, 2022].

CohenMiller, Anna; Saniyazova, Aray & Saniyazova, Zhanar (2019). Graduate student parents in Kazakhstan. Presentation, Comparative International Education Society (CIES) Conference, San Francisco, CA, USA, April 14-19, 2019.

CohenMiller, Anna; Demers, Denise; Schnackenberg, Heidi & Izekenova, Zhanna (2022). "You are seen; you matter:'' Applying the theory of gendered organizations to equity and inclusion for motherscholars in higher education. Journal of Women and Gender in Higher Education.

Coyne, Carolyn; Ballard, Jimmy D. & Blader, Ira J. (2020). Recommendations for future university pandemic responses: What the first COVID-19 shutdown taught us. PLOS Biology, 18(8), e3000889, https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pbio.3000889 [Accessed: February 25, 2022].

Crawford, Bridget (2014). For those who cringe at the word “seminal” when used in academic discourse. Feminist Law Professors, April 30, http://www.feministlawprofessors.com/2014/04/cringe-word-seminal-when-academic-discourse/ [Accessed: February 28, 2022].

Davis, Jenny (2014a). Don't say seminal, it's sexist. Cyborgology, April 21, https://thesocietypages.org/cyborgology/2014/04/21/dont-say-seminal-its-sexist/ [Accessed: February 28, 2022].

Davis, Jenny (2014b). Seminal is still sexist. A response to the critics, Cyborgology, April 29, https://thesocietypages.org/cyborgology/2014/04/29/seminal-is-still-sexist-a-response-to-the-critics/ [Accessed: February 28, 2022].

Del Boca, Daniela; Oggero, Noemi; Profeta, Paola & Rossi, Mariacristina (2020). Women's and men's work, housework and childcare, before and during COVID-19. Review of Economics of the Household, 18, 1001-1017, https://doi.org/10.1007/s11150-020-09502-1 [Accessed: February 25, 2022].

Doyumğaç, Ibrahim; Tanhan, Ahmet & Kiymaz, Mustafa Said (2020). Understanding the most important facilitators and barriers for online education during COVID-19 through online photovoice methodology. International Journal of Higher Education, 10(1), 166-190, https://doi.org/10.5430/ijhe.v10n1p166 [Accessed: January 10, 2022].

Friedman, May & Satterthwaite, Emily (2021). Same storm, different boats: Some thoughts on gender, race, and class in the time of COVID-19. In Andrea O'Reilly & Fiona J. Green (Eds.), Mothers, mothering, and COVID-19: Dispatches from the pandemic (pp.53-64). Bradford: Demeter Press.

Gregory, Laurel (2020). Mothers taking on "shocking" number of hours caring for children during pandemic: study. Global News, October 20, https://globalnews.ca/news/7408226/mothers-hours-child-care-pandemic-study/ [Accessed: March 3, 2022].

Higginbotham, Eve & Dahlberg, Maria Lund (Eds.) (2021). The impact of COVID-19 on the careers of women in academic sciences, engineering, and medicine. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

Hiscock, Claire (2020). International student voices and the VLE: How can photovoice and student focus groups contribute to the design of VLE spaces. International Journal of Computer-Assisted Language Learning and Teaching (IJCALLT), 10(3), 16-27.

Holland, Dorothy; Lachicotte, William; Skinner, Debra & Cain, Carole (1998). Identity and agency in cultural worlds. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Johnson, George A. (2011). A child's right to participation: Photovoice as methodology for documenting the experiences of children living in Kenyan orphanages: A child's right to participation. Visual Anthropology Review, 27(2), 141-161.

Kossek, Ellen Ernst; Dumas, Tracy L.; Piszczek, Matthew M. & Allen, Tammy D. (2021). Pushing the boundaries: A qualitative study of how STEM women adapted to disrupted work-nonwork boundaries during the COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of Applied Psychology, 106(11), 1615-1629, https://doi.org/10.1037/apl0000982 [Accessed: February 25, 2022].

Lichty, Lauren; Kornbluh, Mariah; Mortensen, Jennifer & Foster-Fishman, Pennie (2019). Claiming online space for empowering methods: Taking photovoice to scale online. Global Journal of Community Psychology Practice, 10(3), 1-26, https://www.gjcpp.org/pdfs/5-LichtyEtAl-Final.pdf [Accessed: February 25, 2022].

Liebenberg, Linda (2018). Thinking critically about photovoice: Achieving empowerment and social change. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 17, 1-9, https://doi.org/10.1177/1609406918757631 [Accessed: January 10, 2022].

Lofton, Saria; Norr, Kathleen F.; Jere, Diana; Patil, Crystal & Banda, Chimwemwe (2020). Developing action plans in youth photovoice to address community-level HIV risk in rural Malawi. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 19, 1-12, https://doi.org/10.1177/1609406920920139 [Accessed: January 10, 2022].

Luescher, Thierry M.; Fadiji, Angelina W.; Morwe, Keamogestse & Letsoalo, Tshireletso S. (2021). Rapid photovoice as a close-up, emancipatory methodology in student experience research: The case of the student movement violence and wellbeing study. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 20, 1-16, https://doi.org/10.1177/16094069211004124 [Accessed: January 10, 2022].

Macdonald, Diane; Dew, Angela & Boydell, Katherine M. (2020). Structuring photovoice for community impact: A protocol for research with women with physical disability. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung / Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 21(2), Art. 16, https://doi.org/10.17169/fqs-21.2.3420 [Accessed: January 10, 2022].

Mark, Glenis & Boulton, Amohia (2017). Indigenising photovoice: Putting Māori cultural values into a research method. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung / Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 18(3), Art. 19, http://dx.doi.org/10.17169/fqs-18.3.2827 [Accessed: January 10, 2022].

Martínez, Lidia Ivonne Blásquez & Ortíz, Lucia Montes (2021). Motherhood and academia in Mexican universities: Juggling our way through COVID-19. In Andrea O'Reilly & Fiona J. Green (Eds.), Mothers, mothering, and COVID-19: Dispatches from the pandemic (pp.153-168). Bradford: Demeter Press.

Matias, Cheryl E. (2011). "Cheryl Matias, PhD and mother of twins": Counter storytelling to critically analyze how I navigated the academic application, negotiation, and relocation process. In session, Paying it forward: Mother scholars navigating the academic terrain. Paper, American Educational Research Association (AERA), AERA Division G Highlighted Panel, New Orleans, LA, USA, April 8-12, 2011.

Matias, Cheryl E. (2022). Birthing the motherscholar and motherscholarship. Peabody Journal of Education.

Merriam, Sharon B. & Tisdell, Elizabeth J. (2016). Qualitative research: A guide to design and implementation (4th ed.). Hoboken, NJ: Jossey-Bass.

Nash, Meredith & Churchill, Brendan (2020). Caring during COVID‐19: A gendered analysis of Australian university responses to managing remote working and caring responsibilities. Gender, Work & Organization, 27(5), 833-846.

O'Reilly, Andrea (2021). Matricentric feminism: Theory, activism, and practice (2nd ed.). Bradford: Demeter Press.

O'Reilly, Andrea & Green, Fiona Joy (Eds.) (2021). Mothers, mothering, and COVID-19: Dispatches from the pandemic. Bradford: Demeter Press.

Rania, Nadia; Coppola, Ilaria & Pinna, Laura (2021). Adapting qualitative methods during the COVID-19 era: Factors to consider for successful use of online photovoice. The Qualitative Report, 26(8), 2711-2729, https://doi.org/10.46743/2160-3715/2021.4863 [Accessed: January 17, 2022].

Roger, Kerstin (2017). The fringe value of visual data in research: How behind is academia? International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 16, 1-7 https://doi.org/10.1177/1609406917736668 [Accessed: January 17, 2022].

Sallee, Margaret; Ward, Kelly & Wolf-Wendel, Lisa (2016). Can anyone have it all? Gendered views on parenting and academic careers. Innovative Higher Education, 41(3), 187-120.

Sanon, Marie-Anne; Evans-Agnew, Robin A. & Boutain, Doris M. (2014). An exploration of social justice intent in photovoice research studies from 2008 to 2013. Nursing Inquiry, 21, 212-226.

Shankar, Arjun (2016). Auteurship and image-making: A (gentle) critique of the photovoice method. Visual Anthropology Review, 32(2), 157-166.

Sprague, Nadav L.; Okere, Uzoma C.; Kaufman, Zoe B. & Ekenga, Christine C. (2021). Enhancing educational and environmental awareness outcomes through photovoice. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 20, 1-11, https://doi.org/10.1177/16094069211016719 [Accessed: January 10, 2022]

Tabaeva, Almira (2021). The challenges of doctoral student mothers with implications for policy change: A case study of Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan. Paper, Round Table "The Gender Differentiated Impact of the Pandemic on Paid and Unpaid Care Work, Gender Economics Research Centre, Almaty, Kazakhstan, June 3, 2021.

Tanhan, Ahmet & Strack, Robert W. (2020). Online photovoice to explore and advocate for Muslim biopsychosocial spiritual wellbeing and issues: Ecological systems theory and ally development. Current Psychology, 39(6), 2010-2025.

Uddin, Mahi (2021). Addressing work‐life balance challenges of working women during COVID‐19 in Bangladesh. International Social Science Journal, 71(239-240), 7-20.

Vygotsky, Lev (1978). Mind in society: The development of higher psychological processes. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Wang, Caroline & Burris, Mary Ann (1997). Photovoice: Concept, methodology, and use for participatory needs assessment. Health Education & Behavior, 24(3), 369-387.

Ward, Kelly & Wolf-Wendel, Lisa (2012). Academic motherhood: How faculty manage work and family. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press.

Woodgate, Roberta L.; Zurba, Melanie & Tennent, Pauline (2017). Worth a thousand words? Advantages, challenges and opportunities in working with photovoice as a qualitative research method with youth and their families. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung / Forum: Qualitative Socia Research, 18(3), Art. 2, https://doi.org/10.17169/fqs-18.1.2659 [Accessed: January 10, 2022].

Dr. Anna COHENMILLER is faculty in the Graduate School of Education and co-founding director of The Consortium of Gender Scholars at Nazarbayev University in Kazakhstan, Central Asia. She integrates the professional and personal with a commitment to building coalitions locally and internationally to promote socially-just qualitative research to facilitate and amplify voice for those marginalized, oppressed, and/or colonized.

Contact:

Anna CohenMiller

Graduate School of Education

Nazarbayev University

53 Kabanbay Batyr Ave, Nursultan, Kazakhstan, 010000

Tel.: (+7) 701 109 0392

E-mail: Anna.CohenMiller@nu.edu.kz

URL: http://anna.cohenmiller.com/

CohenMiller, Anna (2022). Asynchronous online photovoice: Practical steps and challenges to amplify voice for equity, inclusion, and social justice [62 paragraphs]. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung / Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 23(2), Art. 7, https://doi.org/10.17169/fqs-22.2.3860.