Volume 9, No. 2, Art. 50 – May 2008

Interrogating the Conventional Boundaries of Research Methods in Social Sciences: The Role of Visual Representation in Ethnography

Nel Glass

Abstract: The author will propose that the use of performative social science is a means to deliberately interrogate long held conventions of established research. The innovative role of visual art representation in data collection, analysis and public engagement with research will be discussed.

Examples will be drawn from two postmodern feminist ethnographic research which investigated academic professional development, resilience, hope and optimism in the UK, US, Australia and New Zealand from 1997-2005. Artwork was initially created as data collection and digitalised as representation to intentionally validate the voices of research participants, the researcher and viewers of the work. The research participants and viewers were given opportunities to actively engage with the visual work. Artwork complimented two additional research methods: critical conversational interviewing and reflective journaling.

This paper will address the ways inclusion of art methods contributed and deepened data representation. The role of crafting artwork in the field, the artistic changes that represented the complexity of data analysis and engagement with the work will be explored.

It will be argued that the creation and engagement with artwork in research is an empowering and dynamic process for researchers and participants. It is an innovative means of representing intersubjectivity that results in reciprocity.

Key words: artwork, representation, intersubjectivity, reciprocity, ethnography, interrogation, hope, resilience, optimism

Table of Contents

1. Introduction

2. The Possibilities of an Emerging Aesthetic and the Need to Interrogate Conventional Methods

3. Background

4. Art at Work

5. Art at Work in Ethnography

5.1 Overview of research projects

5.2 Performative methods at work in ethnography

5.3 Weaving art and words

5.4 Audience engagement

6. Conclusion

Over the last ten years I have observed and equally, been a part of an exciting changing dynamic in qualitative research. As a research supervisor, I have experienced firsthand, the inclusion and emerging power of performative research methods such as art (BRACKER, 2001; JOYCE, 2007; WARD, 2003), dance (BRACKER, 2001), music (OGLE, 2005) and poetry (BARR, 2004) in health related research projects. Being part of several research student's endeavours to creatively develop and bring their projects to wider audiences not only has been humbling, it has been energising. In a very explicit way, I have embraced, advocated and celebrated performative social science as authentic qualitative research methods within many and varied social science kitchens. And, I don't suggest celebration as a superficial event, being able to breathe life into data and take a further reflexive turn (KUSENBACH, 2002) and/or narrative turn (SPARKES, 2003) creates ubiquitous possibilities for both researchers and viewers alike. This notwithstanding, data reconstructions and new inclusions have only been possible due to researcher's willingness to recognise the limitations of conventional boundaries and "experiment with different ways of presenting [their] text" (DENZIN, 2001, p.45) by ethical and moral means. [1]

2. The Possibilities of an Emerging Aesthetic and the Need to Interrogate Conventional Methods

The motivation to use aesthetics has been driven by multiple post positivist critiques and interrogations of the traditional approaches to research representation. In broad terms, such approaches can offer an alterative means to the achievement of one main purpose in qualitative research that being, getting closer to the lives of the people being studied (TEN HAVE, 2004, p.174); or can combine together scientific and communicative concerns (KEEN & TODRES, 2007). However, most critically, aesthetic based methods can represent the lives of people being studied more acutely. [2]

For over a decade now, "subjectivity and identity are concepts of central importance to critical, feminist and postmodern ontology and epistemology" (OGLE & GLASS, 2006, p.170). For instance, perceptions of self, non-unitary and multiple views of self and polyvocality have necessitated the development of several new approaches on how to represent self in research (BLOOM, 1998; BUKER, 1999; FERGUSON, 1993; GERGEN, 2001; GERGEN & GERGEN, 2000; GLASS & DAVIS, 2004; HARAWAY, 1990; OGLE & GLASS, 2006). [3]

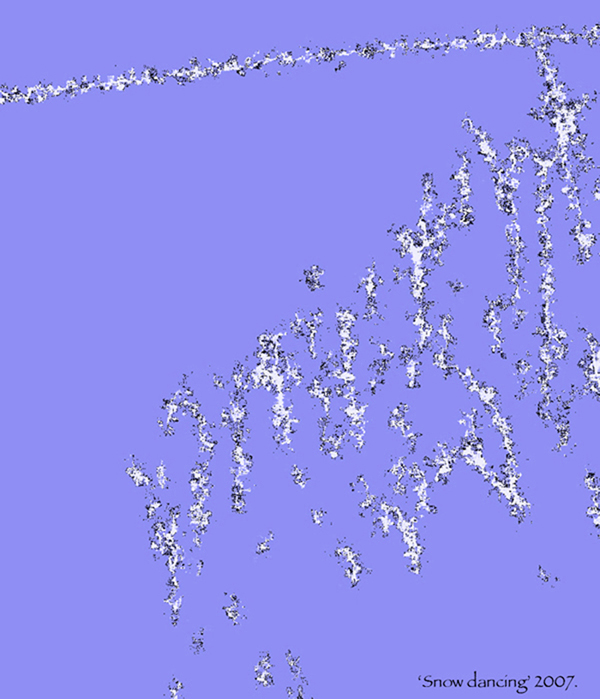

However, whilst most people are seldom univocal and are fundamentally multiplicitous (GERGEN, 2001), there still remains an all-encompassing belief amongst some scholars that the self is one, and one, implies coherency. As GERGEN and GERGEN (2000, p.1037) have suggested,

"[t]here is a pervasive tendency for scholars ... to presume coherence of self. Informed by the Enlightenment conceptions of the rational and morally informed mind, they place a premium on coherence, integration and clarity of purpose. The ideal scholar should know where he or she stands ... Yet ... the conception of the singular or unified self is both intellectually and politically problematic". [4]

Therefore whilst it is imperative that individual researchers are cognisant of their own non-unitary selves as well as their participants, and the incessant impacts on different worldviews of data representation, the use of performative research methods are still emerging. This is despite the fact that the use of multiple perspectives helps to uncover alternative interpretations that otherwise may have escaped consideration (SAVAGE, 2000). And, that the inclusion of performative methodological approaches to social science research creates a medium for necessary fluidity in data expression and representation. [5]

Most specifically, when considering qualitative research in health science the exploration is usually directed towards the meaning of events and people's emotions. However, researchers are often challenged in their quest to accurately express participants unique situations and context. Conventional data is oftentimes represented by flat words on a page, that appear bare and it is this that does little to explain health related phenomena exactly. As people's emotions are complex and multiplicitous, part of the challenge for qualitative researchers is to accurately represent their data and bring alive its meaning. However, my point here is not to champion a methodological approach at the expense of another, rather it is to highlight and engage an audience with "the description of the complex, multi-dimensional object which is the social" (ANGERMÜLLER, 2005, par.14). [6]

Therefore, the not so quiet revolution in performative social science (JONES, 2007) demands that qualitative researchers do not ignore what constitutes legitimate social research in the academy. An interrogation of the rigid definitions of social research is critical and in some disciplines within social science overdue. [7]

The inclusion of performative social science research methods enables researchers and audiences to respond to research aesthetically. Such methods result in processes of unique engagement between researchers and viewers. It does include blurring of boundaries (DENZIN, 2001) and what is energising about this is the possibility for different ways of viewing the same data. By the use of visual and auditory engagement, research takes on new dimensions, it not only becomes interactive, the engagement opens up heuristic possibilities between researchers and viewers. What is more, when health related research depicts emotions, the strong representation of a visual becomes in one's face. When the viewer is drawn in, their responses to such a medium in turn have the potential to engage the researcher further in the totality of the meaning of the research. [8]

Having introduced visual engagement above, I will turn now to the use of art specifically as a performative social science research method and its inherent empowering aspects in health related research. Contextually though, I first provide some background to my thoughts on this topic. [9]

My beginnings in the area of performative art based research methods were perhaps modest. I have identified modest as I believe to be sure of all of the research possibilities at the beginning of projects is somewhat naive and futile. [10]

As a feminist academic in health science I began supervising research students who were established visual and installation artists (BRACKER, 2001; WARD, 2003). Their careers intersected with mine in their quest to bring together art and health in research. I have continued this process now with several students over a ten-year period. Further to this, over the last five years I concurrently have been using performative based art methods in my own health related ethnographic projects. There were two common aims that culminated in all of these projects, which were: the inclusion of a visual explication of the specific health issues in data representation and, the use of artwork in combination with somewhat traditional methods such as the inclusion of written text. [11]

There were some unexpected revelations from these projects that were examples of multiplicity, non-unitary worldviews and different perceptions on a particular body of work. All of projects resulted in healing outcomes and these were not limited to the researchers. The projects were impacting visually on the viewers of the work and, in turn dialogues on emotional healing occurred during and after the exhibitions. Interestingly, there appeared to be an emergence of a healing nexus from the art-based research on health. For instance, viewers demonstrated a strong resonance with the artwork in terms of their own inner health irrespective of whether they participated in the research. Viewers spoke of the ways in which the images contributed to an understanding of their own wellbeing and through self-reflective processes they were able to identify ways to improve their own emotional health. It was my impression that the artwork was dynamic and as a performative research method it had an at work connotation. I will now elaborate on the at work notion of art. [12]

Irrespective of the chosen medium(s) the powerful effects of artwork as a performative social science method are in its generated interactive expression and the effects of that process. Most critically, when the researcher positions artwork for audience engagement a spatial shift occurs enabling the performative. Therefore researchers' need to determine if they have the desire to mobilise their two dimensional images into those that are aesthetically dynamic. Inherent within this is a possible psychological challenge for researchers, as the transformed artwork necessitates interactions with audiences. Researchers need to consider such implications due to the fact that if audience "voices [are] not welcomed or sought, these performative dimensions of practice can easily be ignored" (BRACKER, 2001, p.11) and transformation possibly will not occur. [13]

Whether there is a desired end point in an artwork or not, when art is developed as a performative research method, the visual representations are often the outcome of many interesting intersections. I have stated intersections to mean reflective moments in time, when the researcher pauses in their processes to consider the partial realities of their creation. I also would argue that intersections could be deliberately initiated by the researcher, by the look, feel and message within the artwork, or the interactions between the researcher and viewers. Possibilities are endless in this contemplative engaging performative process. What I am inferring here is that artwork is not a static research method in any way. It is fluid, active and mobile in creation and interpretations. I would term this process art at work. Such an enactment involves a performative process for both the researcher and viewers who are engaging with the artwork. This process is often in contrast to other research methods that may be used to present data such as written text themes in isolation. Therefore when art is working effectively as a performative research method, the actual artwork invites the viewers, research participants and the researcher themselves into the project. [14]

Like a hermeneutic circle the researcher creates the artwork, whilst simultaneously interacting with the creation in isolation and then with an audience. All of these aspects manifest to be like a sum is greater than the parts spiralling phenomena. These result in the researcher's further engagement with the existing artwork and possibly additional creative work. All of this can be attributed to an innovative art at work process. I will now draw on some examples of this process in my own performative art in ethnographic health related research. [15]

5.1 Overview of research projects

From 1997-2004 I conducted a postmodern feminist ethnographic study on the professional development experiences of women nurse academics in universities. [16]

The project was a multi-sited ethnography involving nine university schools of nursing in Australia, New Zealand, Scotland, England and the United States. Following each institutional human research ethics committee approval, a total of 53 participants consented to join the study. The research methods were art-based and written reflections, participant observation and conversational interviewing. [17]

The results revealed the major dominant features to be the increasing competitiveness of university cultures, workplace violence and vulnerability (GLASS, 2001, 2003, 2006, 2007a). A secondary analysis was performed on the data. This included a realist analysis, an oppositional analysis, deconstructive moment and postmodern reconstruction. Participants chose to invert the negatively constructed vulnerability as weakness and revision it as an empowered positive position. Such a refocusing enhanced personal and professional outcomes and the negative term, vulnerability was repositioned as an enabling state (GLASS & DAVIS, 2004). [18]

Participants also identified that university workplaces needed to be more effective and supportive of their faculty, and they were hopeful of positive changes. Yet, hope, resilience and optimism remained marginalised and subjugated discourses. For instance, "whilst emotional resilience was achieved by some participants this occurred over an extensive period of time and only came about if there was cultural change or emotional safety to speak out" (GLASS & DAVIS, 2004, p.89). [19]

As a result of these findings a second postmodern feminist ethnography was conducted in 2005 on resilience, hope and optimism. This project inverted the marginalised and subjugated discourses identified above. This ethnography was conducted in three sites following institutional human research ethics committee approval. There were twenty participants who were nurse academics and clinicians from England, Scotland and New Zealand. The same methods were used for the second ethnography. [20]

The results from this study were that resilience whilst not limited to situations of stereotypical adversity, was perceived as critical to working well in universities and health care. Resilience, hope and optimism were personally driven, and unacknowledged by institutions. Hope and optimism were perceived as necessary components of resilience yet they must be pervasive in nature to result in improved wellbeing (GLASS, 2007b). [21]

5.2 Performative methods at work in ethnography

As outlined above artwork was used as a performative method, however of equal importance was that the artwork appeared to be an empowering research process for myself as the researcher, participants and more broadly other viewers of the images. The distinguishing factor to emphasise is that research methods are traditionally defined as a means to collect data only. Whereas in these two projects I used the artwork as a reflective and reflexive tool. The artwork was developed whilst collecting data and during data analysis, therefore the representations of the images began in the field. The images as a body of work for both ethnographies were publicly presented in art exhibitions, on DVDs and in power point presentations. The engagement with myself as researcher, participants and more broadly audiences highlighted the importance of aesthetic interactions in order to inform further artwork. For example, at the first exhibition the audience asked to see the beginning visual images. Therefore in the second exhibition all of the initial images were included as well as the last images created at the specific time. In these situations art was at work as a praxis tool and, as such, the performative aspects were consistent threads. [22]

In terms of my own engagement I would first sketch a raw image in the field. This may have been representative of an issue, a person or a location. In a reflexive manner in conversations with participants, and through reflective journaling alongside the creation of beginning images, I would begin to construct "a picture of ... [participants experiences of their] professional development in relation to an issue of concern" (STREET, 1995, p.147). This may be an additional image or one that I developed further. The image would be more definitive in terms of the issue with which I was grappling. [23]

As participants spoke of the emotional impact of professional development, optimism, hope and resilience all of the images represented these states. Therefore, in my creations, I was struck, and vacillated between the many possibilities of voice, polyvocality, what I saw and felt to be occurring. I strongly resonated with the comment by BLOOM (1998, p.2),

"we grapple with concerns about ethics, reflexivity, emotions, positionality, polyvocality, collaboration, identification with participants, intersubjectivity, and our own authority as interpreters. Postmodernist thinking increasingly makes the interpretive task tricky as the old theories and master narratives of unified individuality collapse and are slowly displaced by theories of the speaking subject". [24]

After returning from each ethnographic site my efforts were directed further towards accurately representing the participants voices. This was perceived as a visual process using both the created images and written text. I had a strong desire to validate the participant's many voices and particularly, the complexity of their previously unheard emotions. [25]

I would listen repeatedly to the conversational stories from the participants; reflect on my field notes and earlier images. This created the momentum to create additional images as I moved towards an interpretation and analysis of the participant's experiences. As in the hermeneutic circle outlined above, I found this newer work informed the earlier work. Digitalising the images was a further at work process. Through this medium I would enhance and manipulate the images fluidly in order to deepen the representation of the emotional aspects of the participant's stories. I was then well positioned to create a visual body of work for two art exhibitions on the research projects. An example of a beginning point and an image that resulted in significant fluid manipulation is represented below (Figure 1 and 2) in the images entitled snow dancing. These were exhibited in the second exhibition (GLASS, 2007c).

Figure 1: Snow dancing: Initial field sketch (GLASS, 2007c)

Figure 2: Snow dancing: Image in exhibition (GLASS, 2007c) [26]

It is important to emphasise this performative process was not about, using art for arts sake (SPARKES, 2003). Rather, it was an attempt to go beyond the traditional, namely to position the two bodies of artwork explicitly amongst the relevant health audiences. It was intentional to have the viewers as part of the enactment process. As KEEN and TODRES (2007) have suggested oftentimes research findings are only reported in journals or at conferences and this limits those who would be able to access these findings. I, like KEEN and TODRES (2007, par.4) wanted to ensure an "active task of applying research to practice, policy or people". As such, I created these bodies of work and took these to locations and the people who would most likely be able to benefit from performative interactions, namely the health and art communities. [27]

One of the reasons for choosing to represent my data as both artwork and written text was to bring together multiple viewing positions even if at times both might seem like collisions (BRACKER, 2001) or contradictions of reality (CHEEK, 2000). Moreover, I wanted to ensure that my internal written and visual methods were as explicit as the exterior representations irrespective of similar or different interpretations. As BRACKER reflected, "being attentive to the collisions between my 'exterior' and my 'interior' spatio-temporal environments and my interpretations of them, produced a threshold within which my journeying was possible" (2001, p.180). [28]

As with the snow dancing visuals illustrated above, in the exhibition I also positioned written text data by pseudonym, and the practical details of the image development on a card. The card was adjacent to the visual images. The following illustrates the card for "Snow dancing".

"Snow dancing" (2007). Image 29.5 x 35cm; Framed 46 x 51cm. Mixed media. Image created with pen; digitally enhanced—Photoshop 8.0 on MacBook Pro; white mat board on black frame.

This image symbolises the safe connections with colleagues. The dance is representative of the freedom participants experienced by positive communications. It is critical to participants' wellbeing and strengthening resilience.

I think it's important to voice things out a bit ... [because] perceptions can be quite out of whack ... [and] to do that with someone that you trust (Indigo).

A group of us last year... said we have to make this work ... and it's about saying let's care for each other, and ... hey, you're okay and I care for you. You know, I thought about you outside of work (Torie).

On support mentoring: Oh god it's wonderful, yeh, it's just wonderful ... and I've maintained a relationship with a network of women who work in health that meet every so often... and it's the personal relationships that makes it important and just a caring place to be and feel safe to make mistakes (Felicity). [29]

Moreover as I mentioned earlier in health related research I have experienced the ways in which both art and written text seem to speak with, and to, audiences and the combination appears to create a healing nexus. What I am meaning here is that a healing process seems to be instigated when viewers within the safety of the viewing space, become de-silenced, reclaim their voice (GLASS, 1998) and speak of their resonations with the images. At both exhibitions, I provided a blank book for viewers to comment on their thoughts. I will now put forward the following viewer reflections on the exhibition of hope to illustrate this process:

"A relaxing atmosphere and the art provides a space to reflect on resilience for all of us creating boundaries between our work and ourself. Thank you for sharing this with us". [30]

Another viewer wrote:

"As always your work is amazing! It takes me on a journey of my own self reflection, thank you—I'll take a little bit of it home". [31]

In terms of reciprocity the viewers' thoughts also contributed to the researcher's future knowing. VAN MANEN has explained it this way,

"[we] may have knowledge on one level and yet this knowledge is not available to our linguistic competency ... it may be that what remains beyond one person's linguistic competence may nevertheless be put into words by another person ... something that appears ineffable within the context of one type of discourse may be expressible by means of another form of discourse ... [w]hat appears unspeakable ... one moment may be captured, however, incomplete, in language the next moment" (1990, pp.113-114). [32]

Therefore as a result of the inclusion of visual representation in both images and written text, the research began to speak to more researchers, participants and viewers in various, unique and individual ways. As one viewer said:

"While I found some of the pieces difficult to look at as they reflected some of my own personal issues ... this could be considered validating. Sometimes words can't quite reflect a thought or an experience but your art, I feel, not only compliments your written research but also can stand alone as emotion-inducing, meaningful pieces of art!" [33]

Most critically, the combination of both prevents "an inactive representation bounded by the spatialities of the page" (BRACKER, 2001, p.143). Interestingly, it seemed that as art at work avoids the voices of the participants being "muted and inauthentic" (ROGERS & BABINSKI in SPARKES, 2003, p.417) the visual images appeared to speak to the audiences. [34]

I will now provide an example from both exhibitions of the use of written text with a visual image. Figure three "Vulnerability" is from the first exhibition and illustration four, "Her" is from the second exhibition below.

Figure 3: "Vulnerability": Image in exhibition (GLASS, 2006) [35]

The accompanying written text card for "Vulnerability" was:

"Vulnerability" (2005). Image 22 x 74cm; Framed 39 x 92cm. Mixed media. Image created with soft pastel; digitally enhanced—Photoshop Elements & Photoshop on Macintosh G4; white mat board on black frame.

This image was triggered by participants discussing the importance of emotional safety, acknowledgement of their stories without judgement whilst they felt vulnerable. For Emma, being heard through her emotional pain mattered considerably to her and decreased her vulnerability. She said, "well I met you and you've heard my story".

Vulnerability was an overwhelming emotion, thought and reaction to destructive communication at home and work. Yet it was possible for vulnerability to be re-visioned and acted on positively and strategically to improve one's wellbeing.

I listened to you present at the conference, and I thought I could tell you a story or two ... Since then I have actually been thinking about how volatile the experience of being a senior woman [nurse academic] actually is, ... and so you have to kind of re-position yourself against all of these external forces (Minereva).

The image symbolises that inter-personal and intra-personal vulnerability can be an opportunity for growth, and contribute to emotional resilience rather than a stereotypical dis-empowering event.

Figure 4: "Her": Image in exhibition (GLASS, 2007c) [36]

The accompanying written text card for "Her" was:

"Her" (2006).

Image 37 x 48.5cm, Framed 53 x 65cm.

Mixed media. Image created with pen.

Digitally enhanced—Photoshop 8.0 on MacBook Pro.

White mat board on black frame.

Image inspired by participants identifying positive aspects they see within themselves and their colleagues. It also represents the valuing and nurturing of those experiences.

I have a certain style, I see everyone in the school as being really creative but we are in different sort of ways. Some do it in a very structured way and other people's style is not black and white and we are all really different (Tessa).

I tend to gravitate toward those people who are women sensitive in their approach to care, but really give a damn about ... what we should be doing and what we're not doing (Isis). [37]

I would argue that engagement with audiences is one of the most empowering aspects of performative social science research methods. It opens up the humanness in interactions and more broadly social science pursuits (Kip JONES, website). Whilst ensuring anonymity the performative process honours participants (JONES, 2007) publicly, and specifically, validates their courageous stories. Moreover, the relationships between viewers in these projects were characterised by reciprocity. Viewers were extremely willing to engage and share their thoughts and feelings and were as interested in the many and varied impacts of the work on myself as the researcher. [38]

Moreover, such a process for researchers allows for their own embodiment as they too, have the potential to become actors in their interactions with viewers (BRACKER, 2001). In my own ethnographic work I wanted viewers to experience the visual representations, bring them in, see and interact with my processes. It was the vivid depiction of emotion that needed to be seen. [39]

My art exhibition on the first ethnography was titled "look at me, feel it" (GLASS, 2006). This title was deliberately chosen to represent the ways in which I was encouraging the viewer to come right into the research processes. I wanted the viewers to engage not only in the so-called outcomes of the research but equally be part of my processes as a researcher, and interact with this body of work. In this and the next exhibition, titled "Hope through the looking glass" (GLASS, 2007c) I represented the research findings by using both visual and written text. In the second exhibition, initial field images were presented, as were the last images at the time of the exhibition. [40]

Furthermore, having audience involvement in these bodies of work again brought alive the performative. As CARTER stated,

"We need a vocabulary able to describe self-conscious events, capable of revealing the subjective significance of performances. It is not enough to describe what they represented or how they were seen; we also need to ask what was intended and how (quite literally) the intention was embodied" (1992, p.172). [41]

Therefore my reflexive embodiment now encompassed several additional gifts from both audiences and other scholars. Audiences have strongly identified with these bodies of work however, I was mindful that location needs to be understood as partial, and therefore a moment in time. As one viewer has revealed what a fantastic reflection, the energy in here reflects so much of you and your art, resilience and reflection I love it all. However the moments are tangible as one's creations are just "condensed maps of contestable worlds" (HARAWAY,1997, p.11). [42]

However as a performative social science research, I see these reflections as performative gifts or art at work and they have resulted in my intention to further explore the research on resilience, optimism and hope in the form of an additional exhibition. [43]

The paper presented has focused on a positive role for performative art based social science research. I have introduced and explained the power inherent in art at work as a research method and most specifically its possibility to be an active transformative process. [44]

I have advocated for its utilisation especially in health related research, where there is often a focus on getting in close to participants lives, and their emotional wellbeing. Examples of such a process have been highlighted throughout the paper, particularly those that result in levels of emotional healing for all those involved in the research process. [45]

In this paper I have explored the terrain of the current discourse and interrogated the traditional conventions in social science research. This notwithstanding, I have not rejected traditions in totality. More so, I have advocated for the performative and explored ways that both written and visual texts can be utilised in, and at the same location. I have argued for the combination of visual and written text as empowering performative research methods and processes for research that is centred on emotions. [46]

I finally propose and advocate for the use of performative social science methods as a challenging yet daring move forward in transformative processes for researchers, participants and viewers alike. It too can be and is a convincing contribution to social science. Opening one's mind to possibilities can turn researchers' dreams to fulfilling realities in their practices. [47]

I close this paper with a final gift from two viewers on resonating images and processes:

"The work really resonates—it's not just nurse academics this is relevant to, I think lots of workers' in the modern world would find this of interest, thanks for bringing it to us".

"Thoroughly enjoying the visuals, the diversity of images, beginning to understand the power of this process". [48]

The research participants, for their time and generosity of spirit in sharing their experiences. Southern Cross University Australia, for funding of this research.

Angermüller, Johannes (2005). "Qualitative" methods of social research in France: Reconstructing the actor, deconstructing the subject. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung / Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 6(3), Art. 19, http://www.qualitative-research.net/fqs-texte/3-05/05-3-19-e.htm [Date of access October 28, 2007].

Barr, Jennieffer (2004). Living with an uninvited guest: A hermeneutic analysis of the impact and self-management of postpartum depression. PhD Thesis. Southern Cross University.

Bloom, Leslie (1998). Under the sign of hope: Feminist methodology and narrative interpretation. Albany: State University of New York Press.

Bracker, Maree (2001). The art of installation: Scripting the threshold. PhD Thesis. Southern Cross University.

Buker, Eloise (1999). Is the postmodern self a feminised citizen? In Shirley Heckman (Ed.), Feminism, identity and difference (pp.80-99). London: Frank Cass.

Carter, Paul (1992). Living in a new country: History, travelling and language. London: Faber & Faber.

Cheek, Julianne (2000). Postmodern and poststructural approaches to nursing research. Thousand Oaks: Sage.

Denzin, Norman (2001). The reflexive interview and a performative social science. Qualitative Research, 1(1), 23, http://qrj.sagepub.com:80/cgi/reprint/1/1/23 [Date of access: October 27, 2007].

Ferguson, Kathy (1993). The man question: Visions of subjectivity in feminist theory. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Gergen, Kenneth (2001). Social construction in context. London: Sage.

Gergen, Mary & Gergen, Kenneth (2000). Qualitative inquiry: Tensions and transitions. In Norman Denzin & Yvonne Lincoln (Eds.), Handbook of qualitative research (2nd ed., pp.1025-1046). Thousand Oaks: Sage.

Glass, Nel (1998). Becoming de-silenced and reclaiming voice: Women nurses speak out. In Helen Keleher & Frances McInerney (Eds.), Nursing matters (pp.121-138). Melbourne: Churchill Livingstone.

Glass, Nel (2001). The dis-ease of nursing academia: Putting the vulnerability "out there" Part two. Contemporary Nurse, 10(3-4), 178-186.

Glass, Nel (2003). Studying women nurse academics: Exposing workplace violence Part two. Contemporary Nurse, 14(2), 187-195.

Glass, Nel (2006). Look at me, feel it [Art exhibition]. NEXT SCU Art Gallery. Lismore NSW: Southern Cross University.

Glass, Nel (2007a). Investigating women nurse academics' experiences in universities: The importance of hope, optimism and career resilience for workplace satisfaction. Annual Review of Nursing Education, 5, 111-136.

Glass, Nel (2007b). Finding the key to proactive mental health practice: The relationship between hope, optimism and resilience. Paper presented at the 13th Annual International Hunter Mental Health Conference Resilience—Key to Thrive, Newcastle, NSW, Australia, May 18.

Glass, Nel (2007c). Hope: Through the looking Glass [Art exhibition]. NEXT SCU Art Gallery. Lismore NSW: Southern Cross University.

Glass, Nel & Davis, Kierrynn (2004). Reconceptualizing vulnerability: Deconstruction and reconstruction as a postmodern feminist analytical research method. Advances in Nursing Science, 27(2), 82-92.

Haraway, Donna (1990). A manifesto for cyborgs: Science, technology and socialist feminism in the 1980s. In Linda Nicholson (Ed.), Feminism/postmodernism (pp.190-233). New York: Routledge.

Haraway, Donna (1997). Modest_ witness @second_millennium. femaleman© _ meets oncomouse™: Feminism and technoscience. New York: Routledge.

Jones, Kip (2007). How did I get to Princess Margaret? (And how did I get her to the world wide web?). Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung / Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 8(3), Art. 3, http://www.qualitative-research.net/fqs-texte/3-07/07-3-3-e.htm [Date of access: October 28, 2007].

Joyce, Susan (2007). The processes towards new notions of self. Paper presented at the DOaRS Health Promotion and Disease Prevention Postgraduate and Honours Research Seminar, July 11. Southern Cross University. Lismore, NSW, Australia.

Keen, Steven & Todres, Les (2007). Strategies for disseminating qualitative research findings: Three examples. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung / Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 8(3) Art. 17, http://www.qualitative-research.net/fqs-texte/3-07/07-3-17-e.htm [Date of access: October 29, 2007].

Kusenbach, Margarethe (2002). Upclose and personal: Locating the self in qualitative research. Qualitative Sociology, 25(1), 149-152.

Ogle Kaye, Robyn (2005). Shifting (com)positions on the subject of management: A critical feminist postmodern ethnography of critical care nursing. PhD Thesis. Southern Cross University.

Ogle Kaye, Robyn & Glass, Nel (2006). Mobile subjectivities: Positioning the nonunitary self in critical, feminist and postmodern research. Advances in Nursing Science, 29(2), 170-180.

Savage, Jan (2000). One voice, different tunes: Issues raised by dual analysis of a segment of qualitative data. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 31(6), 1493-1500.

Sparkes, Andrew (2003). Review essay: Transforming qualitative data into art forms. Qualitative Research, 3(3), 415-420, http://qrj.sagepub.com:80/cgi/reprint/3/3/415 [Date of access: October 27, 2007].

Street, Annette (1995). Nursing replay: Researching nursing culture together. Melbourne: Churchill Livingstone.

Ten Have, Paul (2004), Understanding qualitative research and ethnomethodology. London: Sage Publications Incorporated, http://site.ebrary.com.ezproxy.scu.edu.au/lib/southerncross/Doc?id=10080971&ppg=184 [Date of access: October 29, 2007].

van Manen, Max (1990). Researching lived experience: Human science for an action sensitive pedagogy. New York: State University of New York Press.

Ward, Louise (2003). The role of art as an innovative reflective practice in nursing: An exploration of the experience of a beginning registered nurse. BNurs Hons Thesis. Southern Cross University.

|

Nel GLASS (RN, BA, MHPEd, PhD) is a registered nurse, sociologist and digital artist. Nel is an Associate Professor and Director of Research and Postgraduate Studies. She has been engaged in feminist emancipatory research projects for most of her academic career. Her research projects continue to be centred on improving workplace practices, hope resilience, optimism; notions of voice, healing and mobile subjectivities. |

|

Contact:

Nel Glass

Department of Nursing and Health Care Practices

Southern Cross University

PO Box 157, Lismore, NSW 2480, Australia

Tel.: +61 266203674

Fax: +61 266203022

E-mail: nel.glass@scu.edu.au

URL: http://www.scu.edu.au/schools/hahs/

Glass, Nel (2008). Interrogating the Conventional Boundaries of Research Methods in Social Sciences: The Role of Visual Representation in Ethnography [48 paragraphs]. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung / Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 9(2), Art. 50, http://nbn-resolving.de/urn:nbn:de:0114-fqs0802509.