Volume 24, No. 2, Art. 3 – May 2023

Transoptic Landscape Analysis: Multidimensional Landscapes of a Multinational Wales

Mark Rhodes

Abstract: In this article I propose a novel extension to landscape analysis through multidimensional understandings, including—yet reaching beyond—tangible and into more-than-representational understandings of landscape. This "transoptic" approach to landscape, breaking away from strictly searching for visual representations of culture, allows for sonic, experiential, and emotional layers of meaning embedded in landscapes to emerge from their plural cultural and historical contexts. Memory, and the production and experience of that memory in the landscape, benefit from this transoptic understanding. Utilizing memory work, which includes both memory production and consumption, in Wales as a case study, I employ a transoptic landscape analysis to approach multicultural understandings of Welsh history, memory, landscape, and identity in the National Wool Museum. Wales faces significant challenges as it navigates the rapidly shifting geopolitics of Europe, the United Kingdom, and its own histories and institutions. This demonstrated transoptic qualitative landscape method may be applied not only to Wales's complicated geographies but to those nations and peoples facing similar challenging memory work across Europe and the globe. Through an epistemology and methodology in which landscape is treated as transoptic and the appropriate mixed methods are deployed to explore multidimensional space and place, clearer contexts of embedded, perhaps even contested, meanings may emerge.

Key words: landscape methods; memory work; national identity; heritage; Wales; museums

Table of Contents

1. Introduction

2. Landscapes, Memories, and Wales

3. Methodology

4. Archiving Landscapes

5. Interviewing Landscapes

6. Performing Landscapes

7. The Discourses of National Landscapes

8. History, Memory, Identity, and National Landscapes

9. Conclusion

Since 1997, the term "landscape" has appeared in the title of at least six percent of geography dissertations in the United States alone (KAPLAN & MAPES, 2015). In light of its permeation within and well beyond geography, some argue that, from the human geography perspective, landscape may have over-stepped its bounds by creeping from the material towards the intangible, ephemeral, and performative arena of "place" (ALLEN, LAWHON & PIERCE, 2019). Certainly, as evidenced in the use of landscape in FQS thus far as little more than a synonym for status, stature, or outlook, landscape has transgressed well away from its rootedness in writing about the land, place, and space (a clear exception is SUWALA, 2021's theorizations of space and cultural landscapes). Instead, I build upon work by WYLIE and WEBSTER (2018, p.44) and others within and beyond the field of geography to challenge the "critical and creative expression" of landscapes. I expand upon existing landscape method frameworks and situate a methodological landscape analysis that contextualizes the embedded layers of meaning and discourse both materialized and intangible within qualitative research methods. In this article, I ask how traditional landscape methods may be expanded upon to explore the breadth and depth of memorial landscapes, particularly those found within national heritage institutions. [1]

Using Wales's National Wool Museum as a case study to illustrate a transoptic—including, yet reaching beyond, the visual—utilization and approach to memory work, I reveal how combining methods of archival, narrative, performative, and discourse analyses may better situate landscape studies—particularly landscapes of memory, heritage, and national identity. The National Wool Museum lies in the west of Wales in a heavily Welsh-speaking area of the country and reflects larger questions of Welsh nationalism and Welsh identity found within the rest of the 7-museum National Museum Wales system and Wales's unique geopolitical situation within the broader United Kingdom. By drawing broadly across mixed methods, I deployed textual analysis of archival materials (POST, 2015), narrative (BERNARD, WUTICH & RYAN, 2016), content (COPE, 2021), and discourse (WAITT, 2021) analyses of semi-structured in-depth and in-situ interview data. These analyses were then supplemented with a combined more-than-representational (WATERTON, 2019) and material discourse analysis (SCHEIN, 2009) of heritage landscapes. Combined, these mixed methods represent what I will refer to throughout this paper as transoptic landscape analysis. [2]

In line with the new cultural geography shift of the 1990s, many of the most significant landscape frameworks and scholars considered the cultural landscape as "a tangible, visible entity" (SCHEIN, 1997, p.660), something "as a concrete, visual vehicle of subtle and gradual inculcation" (DUNCAN, 2004, p.19). These post-structural conceptualizations of landscape as text and the power associated with representation have since followed exploration into the more-than-representational and the role of not only power and symbology but of the affect and agency of landscapes themselves. In the context of new conceptualizations of landscape as experienced, imagined, and intangible, older frameworks benefit from reinterpretation, injecting vibrant ontological considerations of the more-than-representational into landscape. [3]

Using this transoptic understanding of landscape and landscape analysis, I broach the question of how national institutions in Wales, exemplified through the National Wool Museum, have shaped landscapes of national heritage and how visitors experience those landscapes. Combining Welsh styles of understanding the landscape with a reimagined methodological toolset, I identify processes undertaken in producing and experiencing historical narratives in Wales. Using a single heritage institution in Wales, I focus in this article on how a transoptic landscape framework may be situated as a multidimensional lens for use in critical cultural, historical, and spatial research. The following structure follows that framework, beginning with a discussion of the memorial landscape in Welsh contexts (Section 2), transitioning into an exploration of the case study through the four aspects of the methodological framework (Section 3), archives (Section 4), interviews (Section 5), performance (Section 6), and discourse (Section 7), and ending with a discussion of the broader impacts and applications (Sections 8-9). [4]

2. Landscapes, Memories, and Wales

Landscape spans many meanings and interpretations, from something to be scientifically observed to an epistemological way of seeing. Building upon the term "transoptic landscape" as landscape beyond—yet still including—the visual (RHODES, 2021a, p.559), offers yet another "way of seeing." It draws upon more-than-representational concepts that embrace the ability to understand more than just material discourses and their representative symbology and symbolism by bringing in non-representative forms of knowing such as embodied, experienced, and emotional encounters. Transoptic landscape analysis, like more-than-representational theory, includes material discourse but maintains a flexibility and utility necessary to incorporate critical geographies, such as more pluralized or multicultural understandings of place and space. A transoptic approach, I argue, may be a useful means of understanding landscapes. Elsewhere, I suggest transoptic landscapes combine arguments from both non-representational and more-than-representational theories to better incorporate sensory methods (sound, touch, and smell) with emotions, experiences, and the non-human in the methodological decisions necessary to address a transoptic landscape epistemology (RHODES, 2021a). Interpreting and experiencing landscapes can reveal the key functions and representations of memory in place and space but can also move beyond representation as the core result of landscape work. Instead, landscapes reflect the subjective and objective, tangible and intangible, ways of knowing embedded meaning in space and place. As POST (2021, p.170) stressed, "the self is part of the landscape and simultaneously authors it while being subconsciously formed by that same built environment ... [informed by] exposure, connection, access, epistemology, and being in place." This more-than-representational conceptualization of landscape, as well as similar work by WATERTON (2019), informs a transoptic understanding of landscape. Transoptic landscape analysis puts into practice a process of understanding place and space which blends the material and ephemeral, the representational and the embodied, and the multivocality of perspective and place. Memory work, specifically, can be understood partially through landscape analysis' use of personal observation and experience, photography, and field notes. With these tools, I consider the combination of material, archival, performative, and narrative layers at work. [5]

Despite a focus on methodological considerations, I none-the-less add to Welsh studies and landscape perspectives by focusing on the scale of the nation, how national institutions conduct memory work, or the production and consumption of memory as a socially constructed process of interpreting the past (RHODES, 2020a), and how individuals experience those landscapes, spaces, and places of memory. Geographers, in particular, have fostered a great deal of interest in Welsh nationalism (e.g., GRUFFUDD, 1995; JONES, 2008; JONES & ROSS, 2016; KNOWLES, 1999; MERRIMAN & JONES, 2009, 2016). Outside of geography, GAFFNEY (1998), OSMOND (2007), HOWELL (2013a, 2013b, 2016), LEWIS (2018) and MASON (2007) all engaged with post-devolution heritage in Wales. Bringing in a transoptic understanding of landscape builds upon these works by including the structural nature of Welsh memory work with more-than-representational understandings, demonstrating the utility of such a landscape study in the context of memory and national identity. I apply this framework through a case study in Wales of the National Wool Museum, one of seven museums within the National Museum Wales system. [6]

Wales is often presented as an "imagined nation," with work centering upon historic accuracy rather than examining the work that historical (re)creation and memory does (CURTIS, 1986; GRUFFUDD, 1995; HOWELL, 2013a; WILLIAMS, 1985). JONES and FOWLER (2007, p.333) described Wales as a nation of "political and cultural processes in motion, rather than being static." And EVANS (2007, p.124) wrote, Wales's unique relationship with the United Kingdom (and now its shifting presence in the European Union) presents "a wider and more challenging project of nation-building." Bringing a transoptic understanding of landscape, which includes foci on the structural nature of built Welsh memory work, yet also includes more-than-representational understanding, demonstrates the utility of transoptic landscape methods in studying the context of multivocal memory and national identity. [7]

The Welsh language contains two words for "landscape": tirwedd and tirlun. Tirwedd means "land" (tir) "face" (wedd) and is often used when describing topography and physical landscape while tirlun translates directly to "land" (tir) "picture" (llun) and has historically been used for landscape painting or the more aesthetic aspects of landscape. In one of the figures referenced below, you may notice another word, bro, which most often translates more directly to "region." Within National Museum Wales, more often than not, when tirlun is used to describe landscapes, it is used in the plural: tirluniau. Even when translating from English "landscape," the museum will most often use tirluniau ("landscapes"). MORSE (2010, p.3) unpacked tirlun as reflecting "our perception and construction of landscape in social and cultural terms" yet still roots it in scenery. In many ways, through the Welsh language, the highly imbued "landscape" becomes both more operationalized and disparate. Having separate terms define our perception and the physicality of landscape may somehow undermine the comprehensive geographies of landscapes that necessarily incorporate both discourse materialized and a way of seeing into consideration. That would be the case if there was not a third Welsh translation of landscape. Cynefin is an arguably untranslatable concept, combining tirwedd and tirlun with history, identity, and home. Its literal translations include haunt and habitat, which are clearly more-than-representational understandings of landscape. The artist Kyffin WILLIAMS (1998, p.16) contextualized cynefin as "not just landscape but a landscape with everything in it." The memory embedded into the tirluniau or cynefin functions on a spiritual level in the overall national institutions in Wales, contributing to the more-than-representational nature of the landscapes of the nation (PEARSON, 2013; WILLIAMS, 1993). Thus, performances, practices, narratives, and material discourses hold power in the remembering and forgetting in the context of the nation. Such examples in the case of Welsh history include the exclusion and inclusion of slavery within Welsh museums (RHODES, 2020b, 2021b), how environmental impacts are discussed at Welsh industrial heritage sites (PRICE & RHODES, 2022; RHODES, 2021c), or the role Wales played within the British Empire (EVANS & MISKELL, 2020; MISKELL, 2020). [8]

Bringing Welsh styles of understanding landscape together with the memory and landscape methods of historical and cultural geographers, artists, and other scholars, I develop a unique approach to landscapes of memory and heritage in Wales. DROZDZEWSKI's (2016, p.20) "memory-methods," applied to understand the memorial landscapes of the built infrastructure of Berlin and Warsaw, offer a strong example for understanding these processes. Her combination of landscape analysis, participant observation, and interviewing enabled her to better understand the memory embedded in the urban landscape. Likewise, SCHEIN's (2009) landscape framework, which understands landscape as history, meaning, mediation, and discourse materialized, utilized a similar set of mixed methods. Finally, ROSE (2016) brought archival and interviewing methods into the realm of the more traditional understanding of text and visual representations of institutional knowledge production in her discussion of discourse analysis. Memory, shaped by cultural and historical contexts, functions regularly as collective memory. Heritage communicates past events into memorial conceptualizations. Those collective memories, through the process of memory work (the production and consumption of memory), draw from and shape their associated landscapes. NORA (1984) described these spaces as lieu de mémoire [sites of memory]. Memory work often continues in an effort to diversify and grant access to transnational narratives (TILL, 2002). Yet, in some cases when certain events are behind a pay wall, or the institutions are too underfunded to enact permanent and meaningful change, the meaning of the landscape remains traditional. [9]

LEWIS (2018, p.63) explored the role of National Museum Wales, particularly its folk museum, in consciously shaping these sites of memory: "the museum is concerned with opening up the process of constructing history, and of enabling an awareness of methods involved in history-making." She stressed the importance of place here as cultural contexts change resulting in changes to national narratives and help reify "representations of ways of life that we no longer occupy but which are meaningful to us because they represent cultural memory." More common within geography has been the exploration of the memorial landscape, incorporating the dual social constructs of memory and landscape and the layered meanings at work within both. Memory studies scholars and geographers have focused particularly on the ability of such memorial landscapes to shape emotional wellbeing (BOWRING, 2021; DOSS, 2012; GRIFFITHS, 2021; MICIELI-VOUTSINAS & PERSON, 2021) and/or generate political power (KOBES, 2022; RHODES, 2021d; SHEEHAN & SPEIGHTS-BINET, 2019), often through revealing or obfuscating historical narratives. [10]

I present a four-part framework similar to, yet beyond, those presented to include a more performative and intangible perspective. This four-part framework, landscape as history, meaning, performance, and discourse beyond the material, works in tandem to generate broader and deeper understandings of the landscapes of memory work. A transoptic approach demands the blending of artistic, performative, and ethnographic exploration of place and space. Adding landscape to such artistic participant observation contextualizes art and work in place, space, history, community, and representation and, as WATERTON (2021, p.241) stated, it offers to "exceed textual and visual registers, and include the sensual, haptic, corporeal and kinesthetic in theoretically and politically useful ways." [11]

An important caveat to this establishment of such a framework is that these understandings and approaches to landscape are neither exclusive nor disparate. The point I make here, particularly regarding the necessity to delineate between performance and discourse as semi-separate analyses, pushes landscape discourse analysis beyond its historical roots in the material at the exclusion of more-than-representational modes of thinking. In the following framework, while each method does build upon the other, each offers unique ontological and epistemological understandings of landscape. [12]

The data for this study are partly archival, derived from historical contexts and discourses provided by newspaper articles, royal charters, programs, schedules, and stakeholder opinions on National Museum Wales. As POST (2015, p.195) discussed, archives and landscapes "work in lockstep with one another." Most archival sources for the National Wool Museum are located within National Museum Wales's collections at the National Library of Wales. [13]

I also conducted 50 vox pop visitor interviews and five semi-structured interviews with the museum staff. The shorter interviews asked three main questions of visitors leaving the museum, identified using convenience sampling, over the course of one week. Why did they come, what histories have they encountered, and did they have any personal connection to those histories or the place itself? These interviews and subsequent use of word clouds (Figure 1), text mining/content analysis and narrative analysis reveal that visitors both read and experience the museum and place it into the broader context of Welsh industrialization.

Figure 1: Word cloud of visitor responses to how they have experienced Welsh history at National Wool Museum [14]

Performativity allows an attention to identity that spans beyond the visible to the embodied, experienced, and performed layers of the transoptic landscape. Drawing from BUTLER (1990) and FORTIER (2000) who attempted to de-naturalize gender and ethnicity, respectively, I apply many similar concepts to de-naturalize nationality. Performance reflects and embodies the nation and the power for use by or against the political and cultural apparatuses of the state (EDENSOR, 2008; ESCOBAR NIETO & FERNÁNDEZ DROGUETT, 2008; WOODS, 2010). In more literal performative contexts, "ideas of the nation can be reproduced ... created or negotiated" through performance (WOOD, 2012, p.198). BUTLER and SPIVAK (2007) added that not only can music reproduce and define a nation, but it can also be used to contest that nation via counter-culture through minority languages, protest, or the simple refusal to sing (DUFFY, 2005). Unique among the landscapes, places, and spatialities of the performing arts is the role of the festival in making, contesting, and empowering the nation and national identities (DUFFY, 2005; WATERMAN, 1998). The performances, practices, narratives, and material discourses embedded in landscape hold power in the remembering and forgetting of the nation. DEWSBURY et al. (2002, p.438 as cited in WATERTON, 2019, p.93) reiterated that landscapes are not "'codes to be broken,' but instances, events, and practices that are 'performative in themselves; as doings.'" [15]

Performativity allows a clear, yet messy (SOMMERFELDT, CAINE & MOLZAHN, 2014) link for identifying the position of the body, "as both produced by and a product of the world" (WATERTON, 2019, p.93). This framework focuses the experienced nature of the audience and researcher as performers in the landscape and the power of the landscape/performance itself (beyond the metaphor) (THRIFT, 1996; LORIMER, 2005). For instance, WATERTON and DITTMER (2014) and SMITH and FOOTE (2017) recognized the assemblage of meaning at work in heritage landscapes, which treats landscapes as confluent and conflictive, employing a discourse analysis to interpret these meanings. [16]

The role of music, language, and sound as both acoustic variables and emotive atmospheric stimuli explicitly link language, sense of place, and the social structures influencing them (FAUDREE, 2012). Language, in particular, functions as a critical everyday component of soundscape (DEVADOSS, 2017; LEADLEY, 2011). As such, I draw upon a variety of core landscape fieldwork methods to support the overall framework: fieldnotes (LORIMER, 2005), photo-essays (VAN MELIK & ERNSTE, 2019), geospatial technologies, and audio and video recording. [17]

Overall, I utilize archive, narrative, performance, and discourse to navigate various conceptualizations of Welsh national identities. Understanding the history written and read from the landscape and the archives sets up the project. Narratives and the content of visitors and crafters of these landscapes provides context beyond the researcher. Performance roots myself as the researcher into these landscapes beyond my clear presence in the archives and interviews, as well as breaks down the landscape beyond typical material understandings. Finally, the material and immaterial are merged in a discursive reading and experiencing of the landscape. In the remainder of this article, I will use these four frames via a Welsh case study to illustrate such an implementation of a transoptic landscape analysis. [18]

The National Wool Museum sits on the northern edge of the village of Dre-fach Felindre in the industrial complex once known as Cambrian Mills. Previously named the National Woollen Museum, the site began as a gallery for woollen textiles founded in 1976, alongside the still operating Cambrian Mills. Today, the museum serves as a key feature in the village and symbolizes and narrates the significance of the textile industry in Wales. [19]

Most archival documents on the establishment (and contention surrounding) what was to eventually become the National Wool Museum reside at the National Library of Wales. Here, policy documents and meeting minutes from various National Museum Wales committees involved in the foundation of the museum indicate one overarching theme in relation to landscape: interconnectedness. The museum's historical geographies and the surrounding landscapes interconnect across scales, from the local to the national, and across topic, from industry to industrial heritage. While hyper-localized into a single mill, the museum now serves as 1/7th of the country's national museum narrative, and the surrounding landscapes connect not only into the story of Welsh industrialization through the woollen industry but scratch the surface of Wales's broader imperial connections via wool's role in the British Empire. [20]

The Welsh woollen industry is classified by the museum as "one of the most important rural industries" (JENKINS, 1993, p.9)1) in Wales. As founder Geraint JENKINS (1976, p.5) wrote, "[Dre-fach Felindre] was until recently the main centre of woollen production in Wales." The village itself, while surrounded by agricultural production, was a hub of industry. As stated in the Wool Museum's village tour, "The Weaving Trail," at one point there were 24 mills on the banks of what used to be two villages, Dre-fach and Felindre. Today only one remains—Melin Teifi—after returning to the Cambrian Mills site to operate alongside the national museum, and, as of 2022 when the owner retired, the national museum purchased the operation; the remnants of the village's mills inundate the landscape. [21]

Melin Teifi makes the National Wool Museum unique for housing a full production works within its walls. Melin Teifi rented the lower floor of one of the museum's buildings. The founders of the small mill worked at the original Cambrian Mills for many years before it closed in 1982, and brought their small production back when National Museum Wales purchased the entire site and opened the museum in 1984 (DAVIES, 2017). For all but two years of NMW's presence in Dre-fach Felindre, a mill has been operating alongside active interpretation and demonstration, producing blankets, clothing, and other woollen items. Moving forward, National Museum Wales and the National Wool Museum must decide how they will manage operating a fully functioning mill alongside its heritage operations after purchasing Melin Teifi in August, 2022. [22]

With the ultimate goal of bringing meaningful narrative to the historical context of national memory work and landscape, 50 vox pop visitor interviews compliment context provided through the archives. For the vox pop interviews, which are short semi-structured in-situ interviews (DROZDZEWSKI, 2016), I utilized convenience sampling over the course of a week, including both weekend and weekday times, recruiting from all exiting adult visitors during those periods. The 50 interviewees do not approach a representative sample of visitors for that week (n=1001); however, they can speak to emerging patterns and individual experiences. All data were transcribed and coded, assessed via content analysis, and explored for patterns and cross-method connections at a paragraphic level using narrative analyses. I also conducted in-depth semi-structured interviews with all staff at the wool museum. These responses were also transcribed and, at a conversational scale (including my own responses and questions; NETTL, 2015) analyzed using narrative analysis. [23]

As interviewee 30 stated: "[w]ell we both read the information cards extensively, have listened to some of the recordings, and you join the two don't you. That's what we've read. We've read the museum." Not only does this narrative pull out the material power of the museum, it indicates the role of story through non-textual form. In conjunction with the visitor interviews, five of the staff stressed in their in-depth interviews that the focus of the museum rests on story. More often than not, those storied landscapes emerged not from the informational panels but the extra-sensorial affects of the museum and the performances of the staff. Visitors discussed in detail the museum's photographs, sound, music, and smell. However, more than any other topic in the museum, visitors commented on the oral histories throughout the second-floor galleries:

"Yes, well I've seen people using the looms and things and talking about how it used to be here. And obviously there's lots of photographs everywhere and the audio, in the upstairs, you can hear, like, the women talking about how they sewed all the things together" (interviewee 43). [24]

In this case, the combination of the photographs and the oral histories bring the machinery, industry, and museum to life. A Welsh artist (interviewee 8) visiting the museum further commented on these stories and brought those national histories into her own personal memories, but also through the sense of smell:

"Yes, beyond text ... sometimes I read the text, sometimes I just look at what's in front of me, but there's a sound audio, as well, which is quite nice to have cause you get voices telling you stories. And smell, which I thought, that's kind of a memory isn't it. It kind of instigates ... yeah, I associate it with smells that make me think of things like my grandad has, which we've not long ago taken things out of his house, and there were blankets that my nan had made and there's that smell which is kind of really quite significant for me." [25]

In each of these cases, it is the multi-media approach of the museum which engages with visitors' experiences and links them into the broader Welsh histories presented in the museum's transoptic landscapes. [26]

As in most locales, identity, memory, and landscape transcend one another through iterative everyday practice at the National Wool Museum. The agency of artifacts, even when not bringing about greater structural understanding, touch on the memories wrapped up in collective memory embedded within them and embodied into their everyday use within the museum landscapes. [27]

The role of performance also shapes the everyday experience of history on site from the role of the demonstrating craftspeople, to the linguistic performativity, to the use of textiles and fashion performance.

"Without the guidance of the staff, I wouldn't have known what doors you could go out and where they were. Everything is sort of blended together into the painted walls, and the doors' 'come this way' signs are red plaques in small font that you immediately interpret as 'do not enter' or 'fire escape' signs. One door, admittedly in Welsh, had a similar red sign and an odd image of a person pushing the door, which after entering the room I realized the door probably read storage or private and it was actually an image of someone putting their hand up in a stop gesture.

The primary interaction, while somewhat limited from the exhibits, comes from the staff, which I was lucky enough to see operate some of the machines." [28]

My own performance and mediation of the museum's landscapes reflect back within these fieldnotes. Thinking back to my own performance throughout the landscapes of Dre-fach Felindre and the museum, the significance of my monoglottism and the agency of the village and its environment both stand out. Besides this, the role of visitor and staff performance in the museum plays a central role in the development of the museum's identity and the overall experience of the site. [29]

My lack of Welsh comprehension, as my field notes indicate, literally led me in the wrong direction in the museum. With less than 3% of visitors with any degree of Welsh comprehension, this complicates the museum's narrative and, in a way, contrasts the visitor with the identity of place in Dre-fach Felindre, especially with the integration and presence of the Welsh language often listed first and sometimes more prominently than the English translations. It was the primary language in the largest pub in town. Bus riders and drivers communicated in Welsh, and when I hiked up to the cemetery overlooking the town which used to house Capel Undodaidd Pen-Rhiw until it was moved to the Welsh National Museum of History in 1953, I encountered the memorial to the chapel written in Welsh. This memorial (Figure 2) signifies the historical and continuing presence of Welsh in the village. Notice the monolingual text ... in Welsh. My linguistic performativity falls short of outright harassment, but no doubt my preconceived notions that the museum should be bilingual with English signage and translations most convenient to best facilitate my experience of the museum indicate the larger issue of a general imperialistic approach to the museum. As two museum staff discussed in an interview,

"the problem we've got very often is that you're taking a Welsh group round and you do tend to get lots of complains and 'oh, you're speaking that language' and a lot of negativity coming round with it even though someone like Glanmor will be following and he'll be translating [into English]."

Figure 2: A 1953 monolingual marker in Dre-fach Felindre indicating the previous location of the chapel Undodaidd Pen-Rhiw

before it was moved to St. Fagans [30]

The National Wool Museum experiences a conflict between its Welsh speaking staff, Welsh language landscape, Welsh speaking community, and nearly completely non-Welsh speaking visitors. The agency of the village, in addition to language, reveals itself through the integration of the museum into the community and the environmental significance of the surrounding area. As one of my interviewees revealed, each of the small streams which fueled the mills holds a Welsh name that often exposes deep meanings of the place itself and oftentimes these names do not readily translate to English. One of my evenings was spent at the Drefelin Mill, just a short walk through the maze of public footpaths that connect the cluster of mill towns amongst the many valleys of the area. This mill, complete with an in-tact millstone and very few other amenities, continuously houses artists who travel to the quiet village for space and inspiration from other artists and their surrounding environment. While the one artist focused on the Welsh language and the surrounding environment, another was more interested in the accompanying soundscape of the machines at the museum and streams linked to the mills. I interacted with these artists several times in the National Wool Museum throughout the week as they explored and recorded the landscapes of the woollen industry. [31]

In the first floor "Textile Gallery," the performance of wool became most literal, where the significance of Welsh woollen fashion was on full display. Inscribed with many meanings, including the concept that "wool can be class-less, for rich or for poor," the gallery's performance of a Welsh national identity via an embodied (and engendered) form plays throughout. Wool's status as "a cultural symbol, a stamp of identity," came across through the gallery text and accompanying displays and artifacts, but song and film reaffirm the text of the gallery. Most prominent, the "Style Show" plays on continuous film loop in this gallery and some of the associated displayed pieces clearly performed this "piece of Welsh history." MOSTAFANEZHAD and PROMBUROM (2018, p.94) reinforced the importance of these styles of re-enactments in the affect of geopolitical development of tourist imaginaries. These assemblages of performed identities intertwined with the material discourse of the surrounding industrial ruins and the museum itself. Staff and visitors alike brought these assemblages of understanding into the national discourse through the performance of the museum's landscapes. [32]

A broad glance at landscape from a performed perspective in this case illuminates an institutional engagement with non-traditional voices, often alongside what is thought of as traditional. Viewing the memory work of national institutions, such as the National Wool Museum, through solely traditional understandings of landscapes only reveals, for the most part, traditional understandings of culture, paralleling similar performative landscape analyses at the Welsh National Eisteddfod (an annual national festival; RHODES, 2021a). To best understand the intricate nature of these bureaucratic systems of memory and culture where production has shifted away from a "stuff in cases," memorial-mania, or culturally conservative programming approach, the landscape methods employed must be equally progressive, intricate, and flexible. [33]

7. The Discourses of National Landscapes

Building upon and incorporating transoptic landscapes as archive, meaning, and performance, landscapes as discourse bring a fourth, yet overlapping dimension to understandings of memory work and identity. HARVEY (2013, p.155) discussed the incorporation of critical performative and (auto)ethnographic means of understanding memorial landscape as a move away from "strict linear temporality." The past then becomes active and the present no longer functions as the sum of all past events (p.154). Past and memory become prospective rather than retrospective. I now implement Longhurst and colleagues' use of the body as an "instrument of research" (LONGHURST, HO & JOHNSTON, 2008, p.215) core to a more-than-representational method of landscape fieldwork, by participating in and observing the tangible, intangible, and practiced discourses at work within the National Wool Museum. These compounded factors include the significant element of soundscape, textual elements in the museum, and a self-guided village tour developed and promoted by National Museum Wales. [34]

The National Wool Museum not only finds itself inundated with sound, but that sound, for the most part, originates from a single source...running water. Like a moated castle, visitors cannot avoid running water on their approach to the museum. For the five percent who visit the museum by foot and public bus (as well as many whose coaches cannot navigate into the car park), they walk past a large turbine upon their entrance into the shop and beginning of the museum. Likewise, those arriving by car pass over two bridges on their way to the museum's main entrance with one being a leat (the sluice way for the water from the turbine) and the other being the river Teifi. Even for those individuals who walk back along the drive and attempt to go in the back door of the museum (no evidence suggests this occurs regularly) must pass over the vehicular Teifi bridge. Beyond linguistic meanings embodied in these waters, the significance of their sound throughout the museum is powerful. Visitors experience the museum under the constant reverberation of the water wheel. One visitor from England connected personally with the sound, recounting how: "the waterwheel, which was just before the entrance, brought back memories for me" (interviewee 43). [35]

Beyond the water, it was surprising that more visitors did not also comment on the sound of the machinery. As I mentioned above, one of the artists-in-residence spent much of her time audio-recording the machines (§31). Again, between the machines and the waterwheel, visitors are inundated with the pulsing rhythm of industry throughout the museum. In the active mill next door to the main museum building, the sound is intense enough for warnings to be posted in the viewing galleries and for all employees to wear headphones. This soundscape serves as a reminder that you are not in a static museum, but perhaps in the beating heart of what is left of the Welsh woollen industry, where wool products continue to be made by both the museum staff and the on-site mill. Such processes further bring the museum to life allowing affective processes of connection to language, labor, and land to impact interpretation while also instilling a sense of industrial nostalgia. [36]

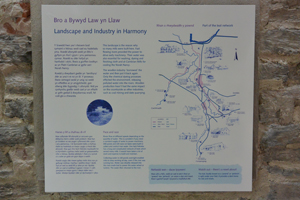

The text throughout the museum further reinforces the national narratives sculpted and experienced by staff and visitors. From the Style Show's line: "An Affordable Piece of Welsh History" (§31), to references of Queen Elizabeth and Prince Charles, to the Welsh-based art exhibit "Hiraeth/Longing," the text continually scales visitors up from a localized woollen mill museum to the larger institutions and narratives at work via the Welsh nation and the British state. And that text from the very beginning of the museum's narrative engages with the concept of landscape. "Landscape and Industry in Harmony" is the first panel most visitors to the museum see, and it says, "[t]his landscape is the reason why so many mills were built here" (Figure 3). The accompanying map shows the relationship between the local communities, mills, and waterways, particularly the importance of the leats which diverted water from the rivers to the mills and thus both powered the mills, but also reshaped the local environment.

Figure 3: An interpretive sign and map of the local surrounds connecting the wool industry to the local landscape. Please click here for an enlarged version of Figure 3. [37]

Finally, while most other national museums in Wales have open dialogue with their surrounding community, only the Wool Museum includes a community tour as part of its discourse. Clearly sitting on the shop counter are four tours of Dre-fach Felindre: one long, one short, in Welsh and English. The longer hour and a half tour called The Weaving Trail, "unravels the woolly wonders of Dre-fach" and expands the notion of a national landscape beyond the walls or boundaries of the museum to include that of the local area. In this way, the museum also actively generates a tourism presence in the community. As indicated in the text of the tour, a description of the "Welsh Not" would also indicate that the audience of this tour may be geared toward the international (non-Welsh) visitor. Also mentioned in the text is the desire for this tour to not only engage visitors with the local community through observation, but through engagement, as well. Encouraging visitors to double-back to some of the locations after the tour and "see what was happening on the inside." [38]

Inside the national museum, children, as well as myself, seemed to get great enjoyment in participating in the museum's internal tour, "A Woolly Tale," which differs from other national museums in that participants actively use wool to card, spin, and stich on, in, and through their Woolly Tale booklet as they move throughout the museum. One interesting element of the activity is that there is no way to complete it monolingually. Once you have sewn the pages together, you are left with English on one side and Welsh on the other, encouraging participants, including this author, to actually transfer their answers from English to Welsh on the now blank, yet available, side of their Woolly Tale. With the 1993 Welsh Language Act, bilingualism has transcended into the everyday materialized and transoptic discourse of memory work embedded within all national museums in Wales. [39]

Nothing may be published or produced by National Museum Wales that is monolingual, and many staff positions now require a familiarity with Welsh for employment. The National Wool Museum sets itself apart, however, by pushing beyond these minimal requirements into a more forceful bilingual engagement. Welsh translations were not simply included underneath or beside an original English text, but often came first, and at times, thanks to the color of signage, the layout of text, or the first language of the staff, took a more prominent position within the landscapes. [40]

8. History, Memory, Identity, and National Landscapes

National memorial landscapes require finesse in finding the appropriate toolbox with which to study unique contexts. While Wales remains a unique situation, there are methodological concepts offered here which I suggest are applicable to other European and global contexts. When discussing national identity, memory, and landscape in a British context, lessons from Wales could have direct and meaningful application for Scottish understandings of national memorial landscapes. Even prior to the most recent move towards Scottish independence, scholars have explored the (more-than-)representational landscapes which tie together culture, politics, and memory in Scottish national identity (DeSILVEY, 2003; EDENSOR, 2005; LORIMER, 1999). Beyond Scotland, however, the adaptability, flexibility, transdisciplinarity, and the transcultural aspect of a transoptic landscape analysis places such a framework into an appropriate position to explore the dialectical navigation of structurationalism between considerations of agency and structure (GREGORY, 1982; WARF, 1988). [41]

Finally, on a broader scale, these processes of understanding memory and a transoptic interpretation of landscape and landscape analysis could be easily injected with other critical thought. Just as these structurational processes in Wales allow agency to correspond to global socioeconomic structures, a more specifically post-structural understanding of transoptic landscape may provide critical historical and cultural context. Just as powerful stories of Welsh wool and mill communities intersect with larger narratives around industry and history in the museum, we can see the intersection of tangible and intangible heritage. Language and material culture, soundscape and environment, smell and industrial heritage, and fashion and textile heritage all illustrate the dialectics of tangible-intangible heritage. All "intangible" cultural heritage in the landscapes of the National Wool Museum is materially rooted, and the landscapes of "tangible" cultural heritage only exist because of performative and experiential embedded meanings. [42]

Already, Black geographies offer a strong theoretical underpinning to a transoptic understanding in geography. As McKITTRICK (2006, p.xi) wrote, "[g]eography's discursive attachment to stasis and physicality, the idea that space 'just is,' and that space and place [landscape] are merely containers for human complexities and social relations, is terribly seductive." Through more-than-representational thought, Western thought and material meaning can yield to the critical, spiritual, and indigenous understandings of place and space—such as in the case of Wales. A transoptic approach to landscape allows more fluid geographies and identities to surface through both the flexibility of the study and incorporating more fluid and plural Welsh senses of place. [43]

Just as Black geographies (p.xii) can span "across the seeable and unseeable, the geographic and the seemingly ungeographic," certain Welsh geographies demand an understanding of landscape as cynefin, requiring an embodied experience and the processes of dwelling amongst the cultural and physical. A loose, yet expanded understanding of these layers of embedded history, meaning, performance, and discourse should not be seen as a stretch of theoretical understanding, but rather an evolution in critical qualitative methodologies. ALLEN et al. (2019, p.1008) stated that "[a]t its core, landscape refers to the plural meanings that are made from an ontologically singular (material) object. In contrast... relational place refers to the plural meanings that are made from an ontologically plural object." I would argue that this reading of landscape is in direct conflict with COSGROVE's (1998) landscape idea of an ontological understanding of space and place. Even through stepping back and understanding landscape as layers of embedded meaning, meaning cannot singularly be spatial but further embedded with sense of place, absence, and emotion. In CRANE and LARA's (2021, p.87) place-based politics of Mexico's disappeared, they, too, acknowledged "that landscape remains fundamental to understanding the spatiality of disappearance," particularly when set into specific cultural contexts. Rather than dismissing this epistemological approach, I would argue that critical scholars can embrace such understandings for their potential to cut across the widest possible geographies, empowering alternative and plural spatial methodologies. [44]

This case study into memory work presents an overview of a transoptic landscape theory and possible understanding as a methodological framework. Clearly, these Welsh examples merely scrape the surface of the possibility of broader analyses, but nonetheless illustrate the diversity of applicability of such transoptic understandings. Through such a lens, industrially rooted and multilingual plural identities emerge within the memorial landscapes of national institutions in Wales. [45]

The ability to think transoptically about landscape, or bring in alternative understandings of the complexity of Welsh landscapes, enabled this study to include archival research, interviews, and performative and other observational and participatory fieldwork. This work fits within the organic progression of landscape understanding and serves as another tool by which social scientists can apply critical analyses and inject multiple perspectives into the methodologies of our fields. Particularly in the context of Brexit and growing independence movements throughout Western Europe, this framework, and Welsh research in general, may point to why, despite twenty-five years of devolution and a presumably progressive Welsh Government, issues of inclusion and access persist in the face of expanded performative landscapes of empowered "others." [46]

This transoptic understanding of landscape should be considered as yet another step toward an ongoing conversation on what landscape means and how it could be implemented in research. By bridging the seen and the unseen, the corporeal with the ephemeral, and the performative and material with the spiritual and sensory, landscape and geography can reach into the critical discourses of disparate nations and peoples. In Wales, the transoptic understanding of memory work has brought forward archival, individual, and performative discourses in the face of institutional heritage. Through such practice, collective memories of the pluralized nation can be understood through their industrial and multifaceted properties. [47]

1) All translations from non-English texts are mine. <back>

Allen, Douglas; Lawhon, Mary & Pierce, Joseph (2019). Placing race: On the resonance of place with black geographies. Progress in Human Geography, 43(6), 1001-1019.

Bernard, H. Russell; Wutich, Amber & Ryan, Gery (2016). Analyzing qualitative data: Systematic approaches. New York, NY: Sage.

Bowring, Jacky (2021). An affective absence: Memorialising loss at Pike River Mine, New Zealand. Emotion, Space and Society, 41, 100845.

Butler, Judith (1990). Gender trouble and the subversion of identity. New York, NY: Routledge.

Butler, Judith & Spivak, Gayatri. C. (2007). Who sings the nation-state: Language, politics, belonging. Kolkata: Seagull Books.

Cope, Meghan (2021). Organizing, coding, and analyzing qualitative data. In Iain Hay & Meghan Cope (Eds.), Qualitative research methods in human geography (pp.355-375). Don Mills: Oxford University Press.

Cosgrove, Denis E. (1998). Social formation and symbolic landscape. Madison, WI: University of Wisconsin Press.

Crane, Nicolas J. & Lara, Oliver Hernández (2021). Place-based politics, and the role of landscape in the production of Mexico's disappeared. Journal of Latin American Geography, 20(1), 79-98.

Curtis, Tony (1986). Wales: The imagined nation. Bridgend: Poetry Wales Press.

Davies, Branwen (2017). Melinau gwlan/woollen mills of Wales. Llandysul: Gomer Press.

DeSilvey, Cailtin (2003). Cultivated histories in a Scottish allotment garden. cultural geographies, 10(4), 442-468.

Devadoss, Christabel (2017). Sound and identity explored through the Indian Tamil diaspora and Tamil Nadu. Journal of Cultural Geography, 34(1), 70-92.

Doss, Erika (2012). Memorial mania: Public feeling in America. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

Drozdzewski, Danielle (2016). Encountering memory in the everyday city. In Danielle Drozdzewski, Sarah De Nardi & Emma Waterton (Eds.), Memory, place and identity: Commemoration and remembrance of war and conflict (pp.27-57). Abingdon: Routledge.

Duffy, Michelle (2005). Performing identity within a multicultural framework. Social & Cultural Geography, 6(5), 677-692.

Duncan, James S. (2004). The city as text: The politics of landscape interpretation in the Kandyan Kingdom. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Edensor, Timothy (2005). The ghosts of industrial ruins: Ordering and disordering memory in excessive space. Environment and Planning D: Society and Space, 23(6), 829-849.

Edensor, Timothy (2008). Mundane hauntings: Commuting through the phantasmagoric working-class spaces of Manchester, England. cultural geographies, 15(3), 313-333.

Escobar Nieto, Marcia & Fernández Droguett, Roberto (2008). Performatividad, memoria yconmemoración: La experiencia de la marchaRearme en el Chile post-dictadorial [Performativity, memory and commemoration: The experience of MarchaRearme in post-dictatorial Chile. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung / Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 9(2), Art. 36, https://doi.org/10.17169/fqs-9.2.389 [Accessed: February 15, 2023].

Evans, Chris & Miskell, Louise (2020). Swansea copper: A global history. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press.

Evans, Dafydd (2007). "How far across the border do you have to be, to be considered Welsh?"—National identification at a regional level. Contemporary Wales, 20(1), 123-143.

Faudree, Paja (2012). Music, language, and texts: Sound and semiotic ethnography. Annual Review of Anthropology, 41, 519-536.

Fortier, Anne-Marie (2000). Migrant belongings: Memory, space, identity. London: Routledge.

Gaffney, Angela (1998). Aftermath: Remembering the Great War in Wales. Cardiff: University of Wales Press.

Gregory, Derek (1982). Regional transformation and Industrial Revolution: A geography of the Yorkshire woolen industry. Basingstoke: Palgrave.

Griffiths, Hywel M. (2021). Enacting memory and grief in poetic landscapes. Emotion, Space and Society, 41, 100822.

Gruffudd, Pyrs (1995). Remaking Wales: Nation-building and the geographical imagination, 1925-1950. Political Geography, 14(3), 219-239.

Harvey, David (2013). Emerging landscapes of heritage. In Peter Howard, Ian Thompson & Emma Waterton (Eds.), The Routledge companion to landscape studies (pp.152-165). London: Routledge.

Howell, David R. (2013a). The intangible cultural heritage of Wales: A need for safeguarding? International Journal of Intangible Heritage, 8, 104-116.

Howell, David R. (2013b). The heritage industry in a politically devolved Wales. Dissertation, history, University of South Wales, UK.

Howell, David R. (2016). Selection and deselection of the national narrative: Approaches to heritage through devolved politics in Wales. In Glenn Hooper (Ed.), Heritage and tourism in Britain and Ireland (pp.161-176). London: Palgrave Macmillan.

Jenkins, Geraint (1993). Amgueddfa Diwydiant Gwlân Cymru [Museum of the Welsh Woollen Industry]. Cardiff: National Museum of Wales.

Jenkins, Geraint (1976). Esgair Moel Woollen Mill. Cardiff: National Museum of Wales.

Jones, Rhys (2008). Wales. In Ernest Gellner (Ed.), Nations and nationalism (pp.1631-1641). Oxford: Blackwell Publishing.

Jones, Rhys & Fowler, Carwyn (2007). Placing and scaling the nation. Environment and Planning D: Society and Space, 25(2), 332-354.

Jones, Rhys & Ross, Andrea (2016). National sustainabilities. Political Geography, 51, 53-62.

Kaplan, David H. & Mapes, Jennifer E. (2015). Panoptic geographies: An examination of all US geographic dissertations. Geographical Review, 105(1), 20-40.

Knowles, Anne (1999). Migration, nationalism, and the construction of Welsh identity. In Guntram Herb & David Kaplan (Eds.), Nested identities: Nationalism, territory, and scale (pp.289-316). Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield.

Kobes, Tomáš (2022). The Maria Stock Pathway. On the building of memorial landscape in the West Bohemian Region. Memory Studies, 15(4), 883-897.

Leadley, Marcus (2011). Soundscape and perception: Reconfiguring the acoustic environment for experimental purpose. SoundEffects, 1(1), 118-138.

Lewis, Lisa (2018). Performing Wales: People, memory, and place. Cardiff: University of Wales Press.

Longhurst, Robyn; Ho, Elsie & Johnston, Lynda (2008). Using "the body" as an "instrument of research": kimch'i and pavlova. Area 40(2), 208-217.

Lorimer, Hayden (1999). Ways of seeing the Scottish Highlands: Marginality, authenticity and the curious case of the Hebridean blackhouse. Journal of Historical Geography, 25(4), 517-533.

Lorimer, Hayden (2005). Cultural geography: The busyness of being more-than-representational. Progress in Human Geography, 29(1), 83-94.

Mason, Rhianna (2007). Museums, nations, identities: Wales and its national museums. Cardiff: University of Wales Press.

McKittrick, Katherine (2006). Demonic grounds: Black women and the cartographies of struggle. Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press.

Merriman, Peter & Jones, Rhys (2009). "Symbols of justice": The Welsh Language Society's campaign for bilingual road signs in Wales, 1967-1980. Journal of Historical Geography, 35, 350-375.

Merriman, Peter & Jones, Rhys (2016). Nations, materialities, and affects. Progress in Human Geography, 41(5), 600-617.

Micieli-Voutsinas, Jacque & Person, Angela M. (2021). Affective architectures: More-than-representational geographies of heritage. London: Routledge.

Miskell, Louise (2020). The steel industry in Welsh history and heritage. In Stefan Berger (Ed.), Constructing industrial pasts: Heritage, historical culture and identity in regions undergroing structural economic transformation (pp.91-106). New York, NY: Berghahn Books.

Morse, Sarah E. (2010). The Black Pastures: The significance of landscape in the work of Gwyn Thomas & Ron Berry. Dissertation, literature, Swansea University, UK, https://cronfa.swan.ac.uk/Record/cronfa42924 [Accessed: February 15, 2023].

Mostafanezhad, Mary & Promburom, Tanya (2018). "Lost in Thailand": The popular geopolitics of film-induced tourism in northern Thailand. Social & Cultural Geography, 19(1), 81-101.

Nettl, Bruno (2015). The study of ethnomusicology: Thirty-three discussions. Urbana, IL: University of Illinois Press.

Nora, Pierre (1984). Rethinking France: Les lieux de mémoire [sites of memory] (Vol. 1-4). Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

Osmond, John (2007). Myths, memories and futures: The National Library and National Museum in the story of Wales. Cardiff: Institute of Welsh Affairs

Pearson, Mike (2013). Land marks. In Oriel Myrddin Gallery (Ed.), Andre Stitt in the West (pp.21-27). Carmarthen: Oriel Myrddin.

Post, Christopher (2015). Seeing the past in the present through archives and the landscape. In Stephen P. Hanna, Amy E. Potter, Arnold Modlin, Perry Carter & David L. Butler (Eds.), Social memory and heritage tourism methodologies (pp.189-209). London: Routledge.

Post, Christopher (2021). Placing affective architectures in landscapes of public pedagogy at the university. In Jacque Micieli-Voutsinas & Angela M. Person (Eds), Affective architectures: More-than-representational geographies of heritage (pp.168-184). London: Routledge.

Price, William R. & Rhodes, Mark (2022). Coal dust in the wind: Interpreting the industrial past of South Wales. Tourism Geographies, 24(4-5), 837-858.

Rhodes, Mark (2020a). Memory. In Audrey Kobayashi (Ed.), International encyclopedia of human geography (2nd ed., pp.49-52). Amsterdam: Elsevier.

Rhodes, Mark (2020b). Exhibiting memory: Temporary, mobile, and participatory memorialization and the Let Paul Robeson Sing! exhibition. Memory Studies, 13(6), 1235-1255.

Rhodes, Mark (2021a). The nation, the festival, and institutionalized memory: Transoptic landscapes of the Welsh National Eisteddfod. GeoHumanities, 7(2), 558-583.

Rhodes, Mark (2021b). Amgueddfa'r Gogledd: Slate, slavery, and transcalar labor in the National Slate Museum. In Mark Rhodes, William Price & Amy Walker (Eds.), Geographies of post-industrial place, memory, and heritage (pp.185-200). London: Routledge.

Rhodes, Mark (2021c). Dancing around the subject: Memory work of museum landscapes at the Welsh National Waterfront Museum. The Professional Geographer, 73(4), 594-607.

Rhodes, Mark (2021d). The absent presence of Paul Robeson in Wales: Appropriation and philosophical disconnects in the memorial landscape. Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers, 47, 763-779.

Rose, Gillian (2016). Visual methodologies: An introduction to researching with visual materials. New York, NY: Sage.

Schein, Rich (1997). The place of landscape: A conceptual framework for interpreting an American scene. Annals of the Association of American Geographers, 87(4), 660-680.

Schein, Rich (2009). A methodological framework for interpreting ordinary landscapes: Lexington, Kentucky's courthouse square. The Geographical Review, 99(3), 377-402.

Sheehan, Rebecca & Speights-Binet, Jennifer (2019). Negotiating strategies in New Orleans's memory-work: White fragility in the politics of removing four Confederate-inspired monuments. Journal of Cultural Geography, 36(3), 346-367.

Smith, Samuel A. & Foote, Kenneth E. (2017). Museum/space/discourse: Analyzing discourse in three dimensions in Denver's History Colorado Center. cultural geographies, 24(1), 131-148.

Sommerfeldt, Susan; Caine, Vera & Molzahn, Anita (2014). Considering performativity as methodology and phenomena. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung / Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 15(2), Art. 11, https://doi.org/10.17169/fqs-15.2.2108 [Accessed: February 15, 2023].

Suwala, Lech (2021). Concepts of space, refiguration of spaces, and comparative research: Perspectives from economic geography and regional economics. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung / Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 22(3), Art. 11, https://doi.org/10.17169/fqs-22.3.3789 [Accessed: February 15, 2023].

Thrift, Nigel (1996). Spatial formations. London: Sage.

Till, Karen (2002). Places of memory. In John Agnew, Katharyne Mitchell & Gerard Toal (Eds.), A companion to political geography (pp.289-301). Hoboken, NJ: Blackwell.

Van Melik, Rianne & Ernste, Huib (2019). “Looking with intention”: Using photographic essays as didactical tool to explore Berlin. Journal of Geography in Higher Education, 43(4), 431-451,

Waitt, Gordon (2021). Revealing the construction of social realities: Foucauldian discourse analysis. In Iain Hay & Meghan Cope (Eds.), Qualitative research methods in human geography (pp.333-354). Don Mills: Oxford University Press.

Warf, Barney (1988). Regional transformation, everyday life, and Pacific Northwest lumber production. Annals of the Association of American Geographers, 78(2), 326-346.

Waterman, Stanley (1998). Carnivals for elites? The cultural politics of arts festivals. Progress in Human Geography, 22(1), 54-74.

Waterton, Emma (2019). More-than-representational landscapes. In Peter Howard, Ian Thompson, Emma Waterton & Mick Atha (Eds.), The Routledge companion to landscape studies (pp.91-101). London: Routledge.

Waterton, Emma (2021). Epilogue: A coda for the "left behind": Heritage and more-than-representational theories. In George S. Jaramillo & Juliane Tomann (Eds.), Transcending the nostalgic: Landscapes of postindustrial Europe beyond representation (pp.235-252). New York, NY: Berghahn Books.

Waterton, Emma & Dittmer, Jason (2014). The museum as assemblage: Bringing forth affect at the Australian War Memorial. Museum Management and Curatorship, 29(2), 122-139.

Williams, Gwyn (1985). When was Wales? A history of the Welsh. London: Black Raven Press.

Williams, Kyffin (1998). The land and the sea. Llandysul: Gomer

Williams, Raymond (1993). The country and the city. London: Hogarth.

Wood, Nichole (2012). Playing with "Scottishness": Musical performance, non-representational thinking and the "doings" of national identity. cultural geographies, 19(2), 195-215.

Woods, Michael (2010). Performing rurality and practicing rural geography. Progress in Human Geography, 34(6), 835-846.

Wylie, John & Webster, Chris (2018). Eye-opener: Drawing landscape near and far. Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers, 44(1), 32-47.

Mark RHODES is an assistant professor of geography at Michigan Technological University. Mark is a cultural and historical geographer focused upon memory, heritage, and landscape, and using cultural and spatial contexts to better understand historical plurality for sustainable and equitable futures.

Contact:

Mark Rhodes

Michigan Technological University

Department of Social Sciences

1400 Townsend Dr. Houghton, Michigan 49931, USA

E-mail: marhodes@mtu.edu

Rhodes, Mark (2023). Transoptic landscape analysis: Multidimensional landscapes of a multinational Wales [47 paragraphs]. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung / Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 24(2), Art. 3, https://dx.doi.org/10.17169/fqs-24.2.3964.