Volume 24, No. 3, Art. 10 – September 2023

Critical Reflection on Sexuality Research in Nigeria: Epistemology, Fieldwork and Researcher's Positionality

Oluwatobi Alabi

Abstract: Within various African cultures, discussion of sexuality is typically secretive and reticent. Because of the multiple and sometimes contradictory narratives about sexuality, researching it in this context remains a very sensitive and knitted terrain, requiring careful navigation of historical, sociocultural and religious factors. The state of such scholarship in Nigeria is here explored critically, drawing on my experience of studying traditional aphrodisiacs in Ilorin. In this article, I present a reflection on the epistemological grounding of that work, my positionality and fieldwork experience, as well as the dilemmas, challenges and the politics of researching sexuality in Nigeria. I argue that the complexity of a researcher's identity and embodiments is not to be treated as redundant; instead, it needs to be taken into account in legitimate and productive ways. Focusing on these elements and experiences during fieldwork revealed how researchers can have the opportunity to contour, compound and contribute to a qualitative study. Investigators must be self-aware and constantly reflexive through this process.

Key words: sexuality; reflexivity; epistemology; positionality; methodology; qualitative approach; qualitative interviewing; fieldwork

Table of Contents

1. Background

2. The State of Sexuality Research in Nigeria

3. Fieldwork Experience: Researching Sexuality in Ilorin, Nigeria

3.1 Doing reflexive sexuality research

3.2 Qualitative design and the study of sexuality

3.2.1 Sampling strategies

3.2.2 Qualitative interviewing

3.2.3 The value of continuous recording: A note

3.2.4 Data analysis

4. Researching Sexuality and Converging Identities

4.1 Credibility criterion: Trustworthiness

4.2 Ethical considerations

5. Moving Forward: Conducting Critical Sexuality Research in Nigeria

6. Limitations

7. Conclusion

Typically, Nigerians shy away from discussions of sex and sexuality; furthermore, such relevant research is paid little attention to except when examined in relation to marriage, demography, prostitution and diseases (IKPE, 2004). This reticence is strongly associated with the country's colonial history and the overwhelming influence of religion. Sexuality, which is more than reproduction, immorality and diseases, is complex, multileveled and relevant to the different aspects of human lives. WEEKS (2003 [1986], p.7) described sexuality as "an historical construction," along with "a host of different biological and mental possibilities, and cultural forms—gender identity, bodily difference, reproductive capacities, needs, desires, fantasies, erotic practices, institutions and values—which need not be linked together, and in other societies have not been." Sexuality is an evolving collection of meanings, acts, mores, values and beliefs constantly related (often in subtle ways) with social structures and contextual peculiarities of the times they are engaged in. As such, DOWSETT (2009, p.22) emphasized that the task of sexuality researchers is to explore sexuality as an ever-changing subject. [1]

IZUGBARA (2004) raised very cogent issues about the state of sexuality research in Nigeria that remains germane to how it is generally approached and how sexuality is understood. He demonstrated that prevailing sexuality discourses in Nigeria are reproduced by oppressive patriarchal subjectivities and ideologies, often manifesting through homophobia, penis-centered framing of power and male-privileging norms and social structures. With an oppressive male-biased cultural construction of sexuality that is couched as normative, gender-related disadvantages are sustained and reproduced. IZUGBARA thus advocated a thorough discussion of the complexities of sexuality in Nigeria, a stance I maintain in this article. [2]

Through a critical reflection on the epistemological framing of the study on women's use of traditional aphrodisiacs (kayan mata) in Ilorin, Nigeria, I outline how sexuality research in the country has been confined to reproduction, morality and diseases and I critique normative assumptions about sex and sexual experiences. I argue that reexamining the conceptual, theoretical and methodological tools that characterize this work in Nigeria is crucial. Critical questions challenging the narrow, overly simplistic and dualistic spectrum through which sexuality is researched must be asked: What are the various ways in which sexuality is experienced? What are the historical, cultural, political, geographical and socioeconomic factors significant to peoples' experiences of sexuality? What are the crucial factors to consider in designing an appropriate methodology involving contextual peculiarities, nuances and the multileveled nature of sexuality in Nigeria? How is the construction of sexuality influential between the relations of power and knowledge in Nigeria? [3]

The purpose of this article is to emphasize problems with the ways sexuality has typically been investigated in Nigeria and then explore how such research can be deepened to ensure criticality and nuance. Critical sexuality research is an opportunity to interrogate questions of power and claims to knowledge. It also shows the evolving cultural embeddedness and context-specific nature of understanding sexuality. [4]

In the first section of this article, I present reasons why carefully investigating the methods of examining sexuality in Nigeria is imperative. I explore the state of sexuality research, aiming to bring to the fore popular methodological designs in the processes involved (Section 2). In Section 3, I show the importance of doing reflexive sexuality research, the benefits of adopting a qualitative design for the study of sexuality, qualitative interviewing and the value of continuous recording during fieldwork. By reflecting on these challenges within a space of converging and intersecting identities, I identify critical dilemmas, complexities and the politics of sexuality research (Section 4). Finally, I discuss the important considerations for research design, limitations and conclusion (Sections 5-7). [5]

2. The State of Sexuality Research in Nigeria

Few researchers have explored in their work the experiences and ways of being, which may be a challenge to Nigerian gender and sexual norms and expectations (IZUGBARA, 2004). With the desire to remain religiously modest and morally upright, researchers are greatly limited in the exploration of sexuality research except where it includes reproduction, sexual violence and the spread of disease (ADETUTU, ASA, SOLANKE, AROKE & OKUNLOLA, 2021; IKPE, 2004; MBACHU, CLARA AGU & ONWUJEKWE, 2020). A historical analysis of the entrenchment of patriarchy and the influence of colonial imperialism on belief systems, morals, values, norms and cultural practices of groups within Nigeria contains useful insights into the contemporary state of sexuality research. [6]

The sociocultural, political and economic legacies of western imperialism linger and continue to have an effect on people's lives across most African countries, decades after independence (BOELLSTORFF, 2012; LEWIS, 2011). Beyond its political and economic gains, the colonial project sustained its grip on the colonies by insidiously capturing and redefining normative practices, and in the process reconstructing core values and belief systems. For instance, through religion, indigenous norms, values, mores, belief systems and practices were demonized and people were urged to jettison them for the civilized and acceptable western (White) ways of life (ANIEKWU, 2006; PEIRETTI-COURTIS, 2021; TAMALE, 2011, 2014). [7]

The regulation of sexuality arguably became a crucial part of the colonial puritanical and medicalization agenda aimed at creating an unequal power relation between the colonizer and the colonized, an asymmetric relation where the colonized looked up to the colonizer for guidance and orientation into a civilized western world. This reductionist project limited discussion of sexuality to 1. reproduction and morality, 2. stiffened self-expression and 3. perpetually constructed and dictated systems of power within the colonies. FOUCAULT (2019 [1976]) described this agenda as a system that uses the body as a medium of social control. Western imperialists depicted African sexualities as primitive, exotic, bestial, immoral and lascivious (EPPRECHT, 2009; TAMALE, 2008, 2014), and African people as hypersexual beings with untamed lust that needed to be saved and modernized. African sexualities were erroneously described as unrestrained and problematic (AHLBERG, 1994; EPPRETCH, 2009; LEWIS, 2011). The exploitation of valuable resources and extension of cultural hegemony were reframed as an agenda to "save" and "modernize" Africa. Religion was a vital tool for this agenda; Africans were admonished to jettison their beliefs and values because they were archaic and unaligned with Western essential requirements for development (AHLBERG, 1994; MEIU, 2015; TAMALE, 2011). [8]

Sexual chastity and purity became the hallmark of these religious teachings, with special emphasis on covering and hiding body parts. As such, dress code regulations were used to control women's sexuality in colonial and even postcolonial Africa. Gradually, teachings promoting values and beliefs steeped in Victorian moralism, body shaming and antisexual codes formed an elaborate scheme for social control across all spheres of these societies (TAMALE, 2014). Even in contemporary Nigeria, the colonial legacy of regulating sexualities lingers and has at times even intensified. [9]

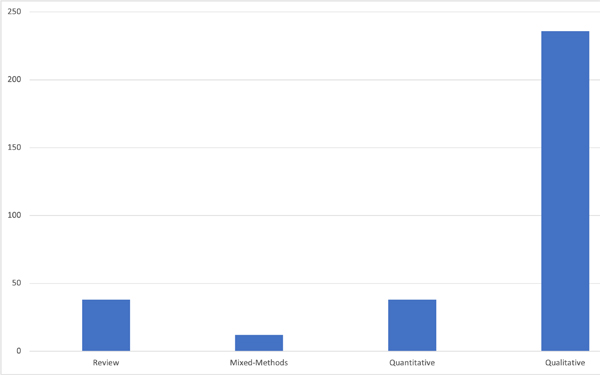

Another challenge with the study of sexuality in Nigeria is the methodology deployed. Most authors adopted a positivist and essentialist approach (see Figure 3) without much emphasis on the social logic and subjective realities having impact on people's experiences of sexuality. Authors using this methodology produced a disingenuous understanding of sexuality. They dismissed the complicated systems of language, contextual experience, cultural institutions and behavioral practices that produce deep and critical discourses of sexuality. Consequently, their text lacks critical questioning of colonial assumptions of African sexualities. FLETCHER, DOWSETT, DUNCAN, SLAVIN and CORBOZ (2013, p.323) presented the audit report of sexuality research and training and described sexuality scholarship in developing countries:

"The audit revealed that a great deal of recent sexuality research and scholarship (and, therefore, research training) either carried out in developing countries or aimed at developing-country audiences occurred mainly in the field of HIV and AIDS. By far the majority of this work followed classic public health, behavioural sciences and/or epidemiological approaches in which sexuality is reduced to a function of (measurable) sexual behaviour carrying risk for HIV infection. Studies were mostly survey-based, with cross-sectional samples of either general populations (e.g., young people and college students) or specific 'at-risk' sub-populations (e.g., gay men and sex workers). The complexities of sexual identities, sexual relations, sexual desires, and sexual cultures were largely absent." [10]

The inherent limitations of surveys for the study of sexualities have been rigorously debated in the academy for decades and have led to experimentation with other methodologies. Underlining this debate is the need to 1. account for complexities and sensitivities, and 2. apply a nuanced lens, carefully unearthing often silenced and repressed knowledge about sexualities. [11]

To further substantiate the fact that sexuality research in Nigeria is highly positivist, I examined a systematic review of empirical literatures published between 2010 and 2021 on sexuality in Nigeria. Table 1 shows the criteria for including a publication. For a wide reach, peer-reviewed and non-peer-reviewed publications were included in this analysis. Only empirical studies discussing sexuality in Nigeria that adopted qualitative methods were included in the final analyzed data. Moreover, because of the language barrier, only publications appearing in English were included.

|

|

Concept |

Search Operation |

|

#1 |

Sexuality |

"sexuality," "sex," "sensuality," "gender," "sexual orientation," "sexual relation," "sexiness," "desirability," "passion," "eroticism," "intercourse," "procreation" |

|

#2 |

Nigeria |

"Nigeria," "federal republic of Nigeria," "Nigerian ethnic groups," "ethnic groups in Nigeria," "Yoruba," "Hausa," "Hausa/Fulani," "Igbo" |

Table 1: Search operation terms [12]

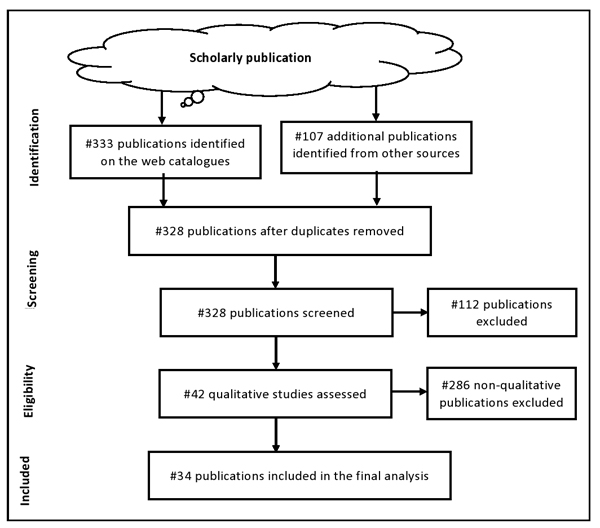

The web catalogues used to gather relevant literature included Scopus, Web of Science (WoS), African Journals Online (AJO) and Sabinet African Journals (SAJ). These well-recognized databases have a wide range of literature across disciplines such as the social sciences and humanities. Figure 1 shows the identification procedure. The search included a combination of terms (see Table 1) that also included various studies on sexuality in Nigeria by methodological design.

Figure 1: Flow diagram for data collection (following PRISMA-P1) by MOHER et al., 2009, p.5) [13]

I searched relevant keywords using the title filter of the databases (see Figure 2). The terms were operationalized together on WoS, Scopus (e.g., see Figure 2) and employed on SAJ. In all these cases, a year limit of 2010-2021 was applied. For journal databases, issues between 2010 and 2021 were scanned to determine if an article met the inclusion criteria. The entire exercise identified 440 articles from the web catalogs. Next, I scanned the abstract and titles of these articles and identified 328 studies, including 12 mixed method studies, 38 reviews and 236 quantitative studies (see Figure 3). The screening also narrowed the searched 42 qualitative studies (see Figure 4) to 34 publications that informed the final analysis in this article. These publications were then imported into ATLAS.ti2) for analysis.

Figure 2: A screenshot demonstrating the search operation on Scopus database. Please click here for an enlarged version of Figure 2.

Figure 33): A chart showing the studies investigating sexuality in Nigeria between 2010 and 2021, by methodological design [14]

In this article, I do not invalidate the positivist approach to investigating sexuality, but rather, I argue that researcher go beyond snapshot surveys in the study of sexuality (NAIDOO, 2008). I believe sexuality studies must have an in-depth, critical and nuanced methodology and that investigators recognize sexuality as a social construct shaped by multiple factors, continuously evolving and ever-changing. These factors must be recorded and engaged with, if any meaning and insight is to be derived from the continuously changing sexual realities in Nigeria. [15]

TAMALE (2011) argued that because of the complexity of sexuality, its studies must reflect its nuances, contextual and multileveled nature. The methods and techniques of inquiry must emerge from an informed understanding that experiencing sexuality is not monolithic, and scholars must tread sensitively. Furthermore, TAMALE noted that the technique for investigating sexualities must have certain forms of flexibility in planning and implementation, as the researcher is tasked with constantly reflecting on the process. Decisions made through the research process may have the need for revisitation—a factor that became crucial in my study of women's use of traditional aphrodisiacs in Ilorin. [16]

To highlight some studies is similarly important, particularly in areas where researchers have exerted significant effort to separate the type of data collected from their epistemological approach. These studies can be described as pragmatic, having a mixed-methods approach (CRESWELL, 2014; MAXWELL, 2021; PATTON, 2015). This approach blurs the lines that have traditionally separated enquiry into constructivist and positivist epistemological worldviews. As a result, researchers now use a variety of data collection methods, regardless of their epistemological perspective. This enables them to collect data that include objective and subjective realities. Despite acknowledging the lack of clarity when separating studies adopting positivistic or constructivist epistemological approaches, I argue that the majority of the studies reviewed in Figure 3 show sexuality largely from a positivist perspective. [17]

3. Fieldwork Experience: Researching Sexuality in Ilorin, Nigeria

The study involved in this article is adapted from my doctoral thesis on women's sexual agency and their use of traditional aphrodisiacs. More specifically, in the doctoral work—which took place in Ilorin, Nigeria, between 2018 and 2020—I sought to understand the varied ways in which women's use of traditional aphrodisiacs, specifically kayan mata4), is influential to sexual agency and notions of empowerment in intimate relationships. In addition, most of the stories told within this research were voiced by married and unmarried women who use kayan mata—in their own ways and on their own terms. [18]

This strategy is consistent with feminist, antiracist and disability research methodologies (LIDDIARD, 2013). DEI and JOHAL (2005, p.2) noted that methodologies such as this show "the minoritized at the center of analysis" where their "subjective experience and voices" are prioritized (POLE & LAMPARD, 2015, p.290). I therefore deemed it very important to present informed, critical and nuanced narrative from the perspective of women using kayan mata and to outline its possible connection to sexual agency and notions of empowerment. With the growth of women's use of kayan mata and its relevance in Nigeria's popular media—especially in anecdotal narratives relating it to juju5) and women's untamed desire to exploit resources (economic, social, political, etc.) from men—kayan mata has become an important issue in the sociology of intimate relationships. Thus, the intention was to situate these women's voices and lived experiences as an informed narrative amongst the myriads of anecdotes about why women use kayan mata. Specifically, a critical and nuanced analysis should be undertaken to know the motivation(s) of women's use of kayan mata and its connections to 1. sexual pleasure and satisfaction, 2. men's fidelity, 3. sexual agency and 4. empowerment in intimate relationships. This subject matter was important to advance the sociology of intimate relationship and family dynamics. [19]

3.1 Doing reflexive sexuality research

This section includes the processes, politics, practicalities and problems of conducting my sexuality research as a young, unmarried, male Christian researcher among married and unmarried women in a predominantly Muslim community in Nigeria. It shows a reflexive but critical account of my experience, highlighting the implications and ways around conducting such work when complex and non-aligning identities converge in the fieldwork. The aim is to "demystify the research activity" (BARTON, 2005, p.319), an important methodological practice in feminist studies where "strong reflexivity" (McCORKEL & MYERS, 2003, p.203) is necessary. Such an approach shows "the diversity of informants and ... the ways that differences between researchers and respondents [participants] shape research processes" (RICE, 2009, p.246). [20]

BERGER (2015) stated that in reflexivity, the investigators’ subjectivity is neither invalidated nor existing knowledge disregarded; rather, data are prioritized and knowledge is critically engaged. The arguments presented in this article are not "narcissistic nor self-indulgent" or "vanity reflexivity" (LIDDIARD, 2013, p.106 KENWAY & McLEOD, 2004, p.527). In this article, I take cues from the reflexive sociology of BOURDIEU, who advocated rather for "intellectual introspection than for permanent sociological analysis and control of sociological practice" (WACQUANT & BOURDIEU, 1992, p.40). [21]

As such, through this reflexive process, crucial attention is given to my personal identity, location within the field and scholastic fallacy. As argued by KENWAY and MCLEOD (2004, p.529), I admit that my understanding and interpretation of the social world as (an intellectual) researcher emerged from the "'collective unconscious' of an academic field." Thus, my reflexivity in this article is purposeful, and I aim to make a significant epistemological, ontological and methodological contribution to researching sexuality in Nigeria. [22]

As a Nigerian, I speak Yoruba and hail from Kwara State, where my study took place. I recruited participants from the state capital Ilorin and its surrounding towns. Some of my childhood was spent in Ilorin, where I have visited ever since. My return to Ilorin to conduct fieldwork involved several dilemmas. SULTANA (2007) noted that describing field versus home is often more challenging and problematic than people realize. For me, returning to Ilorin for fieldwork was not simply going home, but also an opportunity to navigate the intersecting issues of religion, age, gender, education and marriage. [23]

These intersecting identities of gender, religion, age and marriage were significant factors involved in the insider/outsider dynamic within the research context. Being an unmarried researcher in a society that places a high value on traditional family structures and promotes conservative views on sexuality can create a sense of disconnect in interaction with participants. In Nigeria, marriage is often seen as a prerequisite to engaging in a conversation on sexual matters. Some participants may view the unmarried status as a lack of credibility or relevant first-hand experience. Additionally, being a young man may further exacerbate the insider/outsider tension. Age is often associated with wisdom and experience, and youthfulness may evoke skepticism. My age may be seen as a barrier to understanding and relating to older married participants' experiences and perspectives. Furthermore, being a male investigator in a society with a deeply ingrained patriarchy can also shape the dynamics of conducting sexuality research. In Nigeria, dialogue around sex and sexuality are often influenced by gender power dynamics, with men traditionally holding more authority and privilege in such conversations. This power imbalance posed a significant threat to access and could have distorted interpretation of findings. [24]

Consequently, from the beginning of my investigation, I had to negotiate spaces carefully, practice reflexivity and pay attention to my positionality in relation to multiple layers of power structures. Although shaped by the same historical and political forces as my research participants, I may see the native as the other, due to class privilege (KWAME, 2017; SMITH, 2018). I was very aware of my class and educational privilege (in material and symbolic forms). Consequently, I was simultaneously either an insider or an outsider, both or neither (MILLIGAN, 2016; PROBST, 2016). In a similar manner to SULTANA (2007, p.377), I believe that the borders I have crossed are always present within me, negotiating the various locations and subjectivities that I feel simultaneously part of and distant from. Additionally, with "the ambivalences, discomfort[s], tensions, and instabilities of subjective positions" (ibid.), I am compelled to reflect critically on my fieldwork methods. [25]

In this article, I put in chronological order the significant methodological, ethical and material dilemmas surrounding the research process. A crucial part of this discussion is the exploration of the ways in which my "identity, subjectivity and embodiment" (LIDDIARD, 2013, p.106) as a young, unmarried, male Christian researcher were interwoven within the research process and became a significant factor for the chances of recruiting and connecting with participants. Instead of approaching this study as an "objective, disembodied voice, without any particular vantage point or value" (RICE, 2009, p.264), as popularized by most traditionally positivist social research, I consider the role of my inner and outer self, applying a self-conscious and self-reflexive lens throughout the inquiry process (LIDDIARD, 2013). [26]

3.2 Qualitative design and the study of sexuality

The use of traditional aphrodisiacs by women in Nigeria has not gained much attention in literature. As such, an explorative design is essential to the process of investigating the influence of traditional aphrodisiacs on sexuality, sexual behavior and other aspects of women's lives to achieve a detailed and informed understanding of this phenomenon. The use of open-ended questions became an opportunity for participants to express themselves in terms of how traditional aphrodisiacs are believed to affect sexual intimacy, relationship satisfaction and prospects of (in)fidelity. What motivates the use of traditional aphrodisiacs and how they might improve sexual relationships and the quality of marital bonds were questions addressed in the study. Some of these questions were raised spontaneously during the process of data collection, with the aim of gaining more insight into emerging narratives related to women's use of kayan mata. From the outset, it seemed evident that the appropriate research design to investigate the use of traditional aphrodisiacs among women was one that needed to provide room for understanding subjective realities and nuances, an approach best suited to a qualitative design. In this section, I highlight the merits and demerits associated with this design and explore its contextual relevance to the study of sexuality. Furthermore, I provide an in-depth explanation for each of the various methods adopted and their relevance to the research process. [27]

A qualitative research design involves essential strategies to understand how social reality is perceived. Its ability to capture subjective reality is valuable when exploring contemporary social problems, where the narratives of subjects are crucial for knowledge production (SARANTAKOS, 2012). This research design is also useful in describing, generating and testing a theory in relation to certain social phenomena (GLASER & STRAUSS, 2017 [1967]). While qualitative designs have been critiqued for lacking solid methodological generalizability (FLICK, 2014), proponents have responded by arguing that qualitative researchers aim not to draw inferences from a large population but to describe a social phenomenon from the perspective of participants and to understand its implications for the relevance of theoretical propositions (GLASER & STRAUSS, 2017 [1967]). [28]

SARANTAKOS (2012) argued that a qualitative research design should be adopted when investigating relatively unexplored social issues, lacking in comprehensive theoretical propositions. This applies to the use of traditional aphrodisiacs, a topic that has seldom been addressed in empirical work. Knowing more about this phenomenon is important, particularly from the perspective of those experiencing it. I explored the use of such aphrodisiacs and the implications of their use for women's life circumstances, marriages and agency. A design was thus required so as not to treat reality as objective and truth as singular, but rather an approach whereby the investigator could explore this phenomenon, understand the circumstances that influence its prevalence and examine people's subjective perceptions. Following GLASER and STRAUSS's (2017 [1967]) definition, qualitative research design is an opportunity to understand the subjective nature of reality. [29]

According to MASON (2010), the nature of a research problem is crucial for sample selection. Two sampling strategies were adopted: Purposive and snowball sampling. Purposive sampling is used when the information required is confined to a specific group of individuals (SEKARAN & BOUGIE, 2016). The onus falls on the researcher to first define the specific characteristics required of participants who are knowledgeable to answer the questions relevant to the phenomenon. Women who use traditional aphrodisiacs were the participants of this study because they personally experience the phenomenon of aphrodisiacs, especially in terms of how using these may have effects on their sexual agency and sexuality. I also interviewed sellers and men. I included men for many reasons, relevant to the growing debates about women's contemporary use of kayan mata and especially since these conversations seem to be taking on gender roles and expectations. The inclusion of men in this study was meant to provide additional insight, since they were not the primary focus of the work. The 29 persons who had been interviewed at the end of the fieldwork were married women (16), unmarried women (4), sellers (3) of traditional aphrodisiacs, and men (6). Purposive sampling hinges on the fact that the information gathered from these participants can be significantly useful in answering the research questions (SAUNDERS, LEWIS & THORNHILL, 2009). Though criticized for its insufficiency to enable generalization of information to entire populations (SEKARAN & BOUGIE, 2016), the strategy can be an opportunity to recruit those who meet the necessary criteria and provide useful insights. [30]

The second sampling strategy adopted was snowballing. This recruitment strategy is useful for investigating a population that is hardly accessible or available and requires essential referrals from a few identified contacts (SADLER, LEE, LIM & FULLERTON, 2010). Once a suitable participant has been identified, they become a link to recruiting others who share the characteristics relating to the investigated phenomenon (NOY, 2008). In my research, I investigated a highly sensitive social issue among women because despite the popularity of the use of traditional aphrodisiacs among women in Nigeria, married women are still "secretive" about their involvement, due to notions of sexual power and control popularly linked to the use of these traditional sexual stimulants. As such, they were classified as a hard-to-reach population, and so it became essential to locate individuals who could provide referrals to other married or unmarried women willing to participate. Three key informants identified prior to the fieldwork were able to provide referrals. Recruiting young unmarried women was very difficult because of stereotypes that they sell their bodies for sex or are promiscuous and husband snatchers. [31]

The difficulty in recruiting informants exemplifies LEE's (1993) classification of potential threats encountered when conducting research on sensitive topics: Intrusive threat, sanction threat and political threat. Intrusive threats refer to the invasion of "private, stressful, or sacred" areas (p.4). Conducting research that is controversial or involves sexual or religious practices involves a great deal of sensitivity and caution. The second type of threat is called the sanction threat which is related to studies where research participants could reveal information that could be stigmatizing or incriminating. A third type of threat imposed by sensitive topics is the political threat. In such situations, researchers may trespass into areas with some form of social tension because of the "vested interests" of the powerful in society (ibid.). [32]

As discussed and highlighted by LEE, the classification of threats when conducting research on sensitive topics is relevant for the context of my study, specifically intrusive threats. LEE's classification illustrates the significance of considering the potential implications of research on participants and researchers, as well as taking proactive measures to mitigate any potential discomfort or fear that may subsequently arise during the process. Married and unmarried women who use traditional aphrodisiacs were strongly reluctant to take part for fear of being judged or misunderstood. Young unmarried women were unwilling to join the research project due to the aforementioned stigma. As such, the field work was complex because of the need to recruit different categories of participants and interview individuals who could provide robust information to answer the questions. The subjects had to be provided with a safe environment where they could express themselves without fear of being judged, misunderstood or stigmatized. [33]

Equally important from the outset was to assure participants that strict confidentiality would be maintained throughout the research process. A confidentiality agreement was made with them to ensure the privacy of their data and the anonymity of their identities. I requested pseudonyms to use in writing the report; some agreed and a few preferred not to give any names because they simply wanted to share their experiences. When assuring participants of confidentiality it must be followed by a detailed and systematic explanation of how it will be implemented. Consequently, the language used on the instruments of data collection and throughout the interview process must be neutral and nonjudgmental. Expunging words, phrases or sentences that may be construed as discriminatory or stigmatizing was an important part of this research process. Throughout the fieldwork, interviews were conducted at locations where participants felt safe and comfortable, which in this context included inside vehicles in the parking lot of their office, inside a traditional aphrodisiac seller's store, as well as in the home of one of the female research assistants. In every one of these spaces where people were nearby, participants felt very safe engaging. The discussions did not probe if married women got their husbands' approval to take part. However, I inquired if their partners knew they use kayan mata and all of them said yes. It appears that the use of these traditional aphrodisiacs is acceptable within marriages but raises questions when used outside of marriage. Unmarried women were more reluctant to participate in the study. To address intrusive threat, I ensured confidentiality and anonymity, described the overall purpose and procedures clearly and employed trained interviewers who were sensitive to the cultural context. The selection of the sample strategies implemented was premised on the need to assess participants' first-hand knowledge and to facilitate a deep exploration of the phenomenon under investigation (SMITH, COLOMBI & WIRTHLIN, 2013), influenced by the nature of the research problem, purpose, design and implications for addressing the topic. [34]

3.2.2 Qualitative interviewing

I adopted in-depth semistructured interviews aided by open-ended questions to unravel and explore the use of traditional aphrodisiacs by women in Ilorin. CRESWELL and CRESWELL (2017, p.190) noted that qualitative interviews involve "unstructured and generally open-ended questions that are few and intended to elicit views and opinions from the participants." I preferred this interview type for flexibility whereby I could ask questions and the participants could engage with me without specific restrictions. Through this interview type, I could also explore supplementary questions suitable for the interview and ensure that the research objectives were addressed adequately (BRYMAN, 2004). [35]

I developed an interview guide containing questions flexibly drafted to address the objectives, guide the interview process and ensure that all participants were asked the same questions. The interview schedule contained questions so that I could investigate the motivations for women's use of traditional aphrodisiacs and how they influenced sexual behavior and sexual agency. I could probe beyond the listed questions if participants needed to expand and clarify an experience they shared. This would be a follow-up question to further understand or explore a thought shared by a participant in relation to the research. [36]

I usually began these interviews with questions about biographical information, such as "Please tell me about yourself, who you are, your age, and what you do for a living." These questions were aimed at knowing more about the participants and creating a comfortable environment for them to have a conversation. I viewed it as important to get them to say something they might be eager to disclose, such as talking about who they are before moving on to the more detailed discussion related to sex, sexual behavior and sexual experience. Importantly, the responses might differ greatly. Generally, responses ranged from a very detailed description of self to comic praises of their lineage and clan to very short and specific responses about their identities. Also, because of the nature of the study, some participants were uncomfortable saying anything about themselves; all they wanted to do was to participate in the research without their responses being traced to them. This was despite that the informed consent was explained and the clauses on anonymity and confidentiality were emphasized. Apparently, investigating sexuality within this context requires flexibility and a constant reassessment of strategy. [37]

3.2.3 The value of continuous recording: A note

Throughout this research, and with every informal conversation with married and unmarried women in Ilorin, I found ways to initiate talks around traditional uses of sexual stimulation. Through observation and informal conversations with men and women throughout the time of the fieldwork in Ilorin, I gained insights into the popular narrative about women who use traditional aphrodisiacs and what women think of sexual stimulation, as it relates to their sexual agency and sexuality. I constantly kept notes in a diary, as I reflected on essential points, themes, correlations and dissatisfaction about the use of traditional aphrodisiacs within the study location. I kept these notes in a hardback diary and I only used them during informal chats about the research, not during the interview process. I also documented in the diary my observations throughout the fieldwork. This diary became an important resource of knowledge on various meaningful informal conversations in the process of attempting to recruit research participants. [38]

GRAY (2013, p.239) opined that observation "involves the systematic viewing of people's action and the recording, analysis, and interpretation of their behaviour." The notes kept throughout the period of this research were meant to help understand the phenomenon of sexual stimulation among women in Ilorin in the later stages of the work. Also, the informal conversations with individuals who were not part of the sample were my resource for broader insight into the complexity of sexual stimulation among Muslim women who use aphrodisiacs in Ilorin, Nigeria. Moreover, the informal conversations became a good opportunity to highlight the eminent issues that should be investigated in the research. SWAIN and SPIRE (2020) described "informal conversations as opportunities to add 'context' and 'authenticity' to data and argue that they can unlock otherwise missed opportunities to expand and enrich data" (Abstract). The additional insights derived from outside the ambit of the selected interviews also textured the final data analysis. [39]

Once NVivo had been used to organize the data and identify the common pattern of thoughts, I adopted thematic content analysis for data interpretation. BRYMAN (2004, p.181) defined thematic content analysis as "an approach to the analysis of document and texts [which may be printed or visual] that seeks to quantify content in terms of predetermined categories and in a systematic and replicable manner." In this study, the transcripts generated from the in-depth interviews were analyzed and themes were developed based on the research questions and on similar patterns of thoughts expressed by the participants in the process of coding the data. BRAUN and CLARKE (2006) made a succinct list of the process of thematic content analysis, namely familiarization with the data, generating initial codes, searching for themes, reviewing themes, defining, and naming themes and producing a report. In this type of analysis, the researcher must be immersed in the data to develop a rich description and understanding of the thoughts of the participants related to the phenomenon under investigation. [40]

The gathered data were managed with the aid of computer-based software (NVivo 12 Pro). Recurrent patterns and themes were thematically discussed. The recorded interviews were transcribed and then coded in NVivo. Each of the interviews was read thoroughly and the thoughts expressed were coded into major nodes6) and subnodes for analysis. Parent nodes were created from the research questions and objectives, while subnodes emanated during the coding process to describe the narratives. This process could also be referred to as the classification of thoughts into similar patterns. The nodes that were created became essential for the generation of themes and content analysis. Some of the findings of this study show that through the stimulation of love and the enhancement of sexual pleasure, the use of these traditional aphrodisiacs was deemed to strengthen sexual and overall relationship satisfaction. These traditional aphrodisiacs were also used as an important tool for negotiating power and influence within household politics which women found helpful in order to claim agency over their sexual life, enhance their participation in household decisions and challenge oppressive structures that inhibit them. [41]

4. Researching Sexuality and Converging Identities

HATCH (2002) noted that a major characteristic of qualitative research is the ability of the researcher to become a research instrument for data collection. This process relies on their reflexive abilities. DENZIN and LINCOLN (2008) argued that with this process, researchers can admit and clearly state their biases and ideological preferences relating to their study. For instance, the ethical dilemmas in my study included carefully navigating my position as a young, unmarried, male Christian researcher investigating a social issue relating to sex and sexuality among women who are predominantly Muslim and married. [42]

The complex nature of my identity was very relevant to the context and content of the research. My gender and religious identity became the most prevalent of all. According to scholars, gender interacts dynamically with social and cultural categories prevalent within the field. GALAM (2015) reported that a man discussing sex with another man's wife is seen as taboo, specifically within the Islamic Sharia law, which is a religious legal system that outlines several consequences for such acts. As such, caution was required, and it meant including female research assistants in the study. Under the Sharia, sexual intercourse is only permitted within marriage. Interestingly, sexual intercourse is often seen as the act of sexual penetration and other acts that could lead to that, such as private meetings between a man and woman who are not closely related. Illicit sexual acts are considered a punishable offense at discretion in view of the negative impact it might have on society. The offense is often backed with a verse in the Quran, 17:32: "Do not come near zina [illicit sexual intercourse], for it is shameful [deed] and an evil, opening the road to other evils" (OSTIEN & UMARU, 2007, p.44). Moreover, a man who engages in unlawful sexual relations is also believed to commit a civil offense against the woman, irrespective of whether she consented or not (WEIMANN, 2010). Hence, after proper evidence has been provided to establish claims, the man who commits this offense is liable for a proper bride price if the woman is not married, as well as 100 lashes and banishment for one year. [43]

The implications of conducting research on sex and sexual stimulant use among predominantly Muslim married women in Nigeria are multifaceted. As indicated by LEE (1993, p.4), it evokes the notion of a threat of sanctions. As previously explained, the Sharia Law stipulates punishments for acts of sexual non-conformity, including the meeting of a man and a married woman. Therefore, in approaching the field, I had to consider the possibility that some women might feel uncomfortable about sharing intimate details regarding their sex lives with a young, unmarried, male Christian researcher. Therefore, I had to act appropriately to ensure that the privacy and dignity of the female participants were always respected, that my team and I were protected, and that the study remained culturally and religiously sensitive. Failure to do so posed serious ethical, legal and political implications for the entire research process. [44]

While I was part of the entire process, I deemed it essential to recruit two female research assistants to be lead interviewers because some female subjects, as it turned out, were more comfortable relating with female interviewers. After the first five interviews, I discovered that some women were not saying much and did not open up; however, two interviews stood out as they completely opened up and exposed deep-seated debates about the use of traditional aphrodisiacs. From the interview recordings, I noted that a participant mentioned she was comfortable discussing this very private matter of her life with the female assistant because she had said that she was married. This immediately became a turning point for how the fieldwork was approached. Going back to listen to the other three interviews that lacked details, I discovered that these interviews were between the unmarried assistant and married women. Following this discovery, I immediately needed to reexamine my approach and begin to match the participants and research assistants. Subsequently, the married assistant was paired with married women and the unmarried assistant interviewed unmarried participants. Subsequently, this process was very effective. As the interviews proceeded, I discovered that most of the married participants in the study saw marriage as a very strong identity that bears responsibilities and challenges which might not be easily understood by an unmarried woman. This was the reason why they did not open up at the earliest stage of the fieldwork. In addition, some of the other women preferred talking to me directly because they felt it important that men understood their opinion and perspective about issues such as this. These women believed it important to see men become interested in women's practices. These fascinating experiences showed new dimensions into the investigation of sexuality within a predominantly patriarchal society. [45]

As interviews with male participants began, I deemed it crucial to remain conscious and to critically engage normative biases, sentiments and assumptions usually held and often sustained when men talk about women. During these interviews, when phrases such as "you know these women," "all these women wahala [problems]," and "women and their love for men and sex" were used, I asked for clarification. Maintaining this critical approach was helpful to ensure that stigmatizing assumptions about women were not reproduced. [46]

CRESWELL and CRESWELL (2017) noted that a researcher is a fundamental part of the research methodology in a qualitative study. This requires active involvement in and engaging with the emerging methods—from data collection to data interpretation and report writing. As such, I deemed it important to carefully outline how sentiments were addressed in this research to ensure credibility. DENZIN and LINCOLN (2008) commented on the nature of the value-free qualitative study. They believed that, because of the nature of the qualitative inquiry, bracketing the researcher's values from the research process and conclusions is very difficult and takes a conscious reflective effort to recognize these emotions and engage them productively for knowledge production. Thus, the acknowledgment of one’s subjectivity is crucial in a qualitative study. [47]

4.1 Credibility criterion: Trustworthiness

One of the most popular credibility criteria for qualitative studies is member checking. This is a quality control process where research participants can check their interview transcripts to see if they are accurate and valid written translations of the experiences they have communicated in the interviews (HARPER & COLE, 2012). In general, member checking also follows a process whereby, at the end of the interview, the researcher summarizes the points from the interviews to ensure that the participants' thoughts were captured accurately. That was implemented in this study. Following the transcription of each interview, the transcripts were shared with the participants to ensure that the narratives they shared were accurately captured. They agreed that the transcripts adequately captured all the information they shared, and no changes were made to them. YIN (2011) gave a succinct description of the processes of ensuring trustworthiness and credibility. He stated that the researcher must describe and document the procedure in a way that other people can review and understand. This process is one of the applications of a methodology chapter—to detail the processes and methods adopted. YARDLEY (2015) described this as writing up a research report to withstand scrutiny. To design and implement a methodological approach is thus crucial to allow for unhindered discovery and unanticipated events. [48]

Attendance to ethical issues ensures adherence to standardized practices in conducting research, to avoid exploiting or endangering participants (SILVERMAN, 2009). Such issues are taken very seriously in the social sciences, even more so when dealing with a potentially vulnerable group. DIENER and CRANDALL (2016 [1978]) highlighted the factors that should be considered in social science research: posing harm to participants, lacking informed consent, invading privacy, and involving deception. [49]

Markedly, sex and sexuality are fiercely debated across many cultures, especially as they relate to women's decision making. Explicit sexual expression by women is often regarded as a sign of promiscuity and, as such, the topic investigated is one that could have easily led to the stigmatization of the women who chose to participate. It became important that serious precautions were taken and that a well-thought approach that would not expose participants to stigma and researcher to any form of danger be deployed. The first was identifying a study location that is progressive (or at least is seen to be) in its approach to religion and sexuality in Ilorin Kwara State in Nigeria. Apart from it being arguably religiously tolerant, my experience in and knowledge of Ilorin were more advantageous and meant that I understood the various dynamics of the city and could relate better to participants from this space (linguistically and culturally). [50]

An informed consent document containing a detailed explanation of the various ways anonymity and confidentiality were protected was made available to participants. Some of the steps taken and highlighted in the informed consent document included voluntary participation and an option to quit participation without any explanation, at any time they felt uncomfortable, and the use of pseudonyms in report writing to protect personal identities. The purpose of the research was explained in detail to the participants, and they were made aware that, should they feel uncomfortable with the interview process, they could withdraw at any point. In addition, permission to record the interviews was sought. They were also reminded that the information they provided was confidential and that the source would not be divulged at any point as only the researcher and supervisors would have access to the information gathered. This was consistent with SURMIAK's (2018) point that participant information must be protected except for cases where disclosure has been permitted. At the end of the interviews, participants were engaged in an informal feedback session to determine how the interviews went and to ensure that the process had not left them emotionally harmed or with feelings of regret. [51]

5. Moving Forward: Conducting Critical Sexuality Research in Nigeria

The complexity of sexuality necessitates a research design that is discursive, constantly evolving, conscious of emerging subjectivities and nuances, maximally flexible with minimum bias and reflective of contextual peculiarities and multileveled influences. The linear process or a specific framework may be lacking for how sexuality research is meant to be conducted; researchers must plan, implement and constantly reflect on the design throughout the process. Investigators are thus expected to be conscious of their role(s) in the study and that methodology is approached as a political process attending to issues of context, ethics, voice, and ideologies (BENNETT, 2008). Methodology is "part and parcel of theory-building and transformative change" (TAMALE, 2011, p.46). [52]

Researchers of sexuality in Nigeria particularly must be critical of the ways the dualistic understanding of gender has shaped the conception of sexuality. As TAMALE (2011) argued, gender and sexuality have been normatively deployed across Africa to denote power and dominance and sexuality researchers must explore gendered sexualities and/or sexualized genders. Thus, subjectivities must be acknowledged and explored (where applicable) in studying sexuality; the various ways through which sexualities are experienced and embodied must be researched even if these identities are not normative. Uncritical and simplistic conceptualizations of sexuality as just relating to sex must be rethought and critically questioned. [53]

Researchers designing methodologies to study sexuality must position sexuality as a concept that is susceptible to change, constantly evolving and operating within a space where issues like history, culture, politics and experience are constantly in interaction. Empirical studies of sexualities should be foregrounded in the experiences of participants; in doing this, "complex and abstract qualitative phenomena that are unquantifiable, such as emotions, feelings and other sensitive issues critical in sexuality research" (ibid.) must be explored. Also, investigators must "refrain from objectifying participants and avoid hierarchical representations of knowledge about their experiences" (ibid.). This is important because acknowledging subjectivities as highlighted above requires that these experiences are acknowledged and voices recognized as an important part of knowledge production. [54]

Context and methodological limitations are highlighted in the interpretation of the results especially with regard to the argument made about the marginalization of sexuality research in Nigeria. Even though a systematic review of empirical literature was conducted by gathering publications across selected online academic databases, part of the limitations was that not all articles on sexuality adopting qualitative methodology in Nigeria between 2010 and 2021 might have been captured. Apparently, Southern knowledge is insufficiently represented in western-based databases (SCHÄFER & SCHLICHTING, 2014). As such, I consider it crucial to include regional databases like SAJ and AJO. Marginalization in scholarship representation is critical and has implications for knowledge participation (CZERNIEWICZ, GOODIER & MORRELL, 2017), and as such, merits serious attention. [55]

The social, cultural and religious context posed a very tight and fragile environment to address a sensitive topic such as sex and sexual enhancement. As LEE (1993) argued, numerous intrinsic and sanction threats could be navigated carefully. The measures discussed in this article were implemented to create a safe environment for participants to engage. However, I acknowledge that the sensitivity of this research could have affected participation rates. Similarly, as part of the measures taken to navigate the context, I had to include female research assistants as part of my team. They have extensive experience conducting qualitative interviews and are familiar with the cultural context of the study site. Even though I was present, they sometimes had to lead interviews because the respondent preferred a female to ask the questions. As a principal investigator, this could have been a limitation in these contexts. Nevertheless, I find it necessary to conform to legal and cultural regulations and norms. Furthermore, women's use of traditional aphrodisiacs was limited to heterosexual intimate relationships because same-sex relationships are illegal in Nigeria. [56]

I argue that the colonial legacies of African sexualities still linger and as such, this continues to be a significant factor on how sexuality is understood and practiced in Nigeria. Arguments were provided to support the determination that most sexuality research in Nigeria has been positivistic by methodological design, giving little attention to the subjective realities that shape people's experiences. Moreover, the requirements to be morally upright and not to desecrate normative sociocultural spaces became the ultimate limitations for the critical engagement of sexuality, except when it involves reproduction, diseases and morality. These arguments were further substantiated with a systematic review of empirical literature investigating sexuality by methodological design in Nigeria between 2010 and 2021. While the demerits of a positivist approach to researching sexuality were highlighted, I do not discredit the value of the arguments presented in this article but rather I argue that snapshot surveys are insufficient to understand the complexities and dynamics encompassed in sexualities. An appropriate methodology must account for contextual peculiarities, nuances and the multileveled nature of sexualities. [57]

Further, a reflexive account of the processes, challenges, practicalities and politics of conducting critical sexuality research in Nigeria from a sociological perspective has been critically presented. I reflect on the unpopular "warts and all" in research methods textbooks and "impact driven" academic publications, having a significant focus on "sanitized" narratives of methodological processes and practice (POULTON, 2012, pp.67-68). Through this reflexive methodological article, I uncovered significant dilemmas frequently encountered in the study of sexuality in Nigeria and provide important nuggets for how to approach critical sexuality research. The reflexive approach I adopted aligns with feminist epistemologies, ensuring that the production of certain types of knowledge benefits greatly from accountability, reflexivity and positionality (WALBY, 2011). Moreover, I explicate ways in which a researcher's identity, embodiment, subjectivities and lived experience impact empirical research and highlight ways to deal with bias that might threaten the credibility of a qualitative study. [58]

This reflexive account reveals the complexity of my positionality and brings to the fore how facets of my identity manifest in different ways—and in distinct moments—dependent on my encounters with participants' identities (ENGLAND, 1994). These encounters exemplify "the ways that difference between researchers and respondents [participants] shape research processes" (RICE, 2009, p.246). Furthermore, my discussion shows the ways in which multiple aspects of a research process (design, recruitment of participants, researcher/participants relationships and fieldwork/data collection) were—and still are–embedded in my identity, subjectivity and embodiment as a young, unmarried, male Christian researcher investigating an issue relating to sex. The purpose is to contextualize how these compounded elements became the strength rather than the weakness of the study—often prepositioned within positivist assumptions (LIDDIARD, 2013, p.112). In essence, through exploring the relationships between myself and the research process—or through "demystifying the research activity" (BARTON, 2005, p.319)—a rich account of researching sexuality in Nigeria has been documented: A predominantly patriarchal society with a proclivity to shy away from engaging in discussions about sex and not even to attempt to have such conversations with anyone outside their gender category. This reflexive account can be a contributing factor to the methodological repertoire informing empirical sexuality research in Nigeria, whereby I hold (rightly and publicly) my ethical standards, politics and actions to account (DE MARRAIS, 1998; ENGLAND, 1994). [59]

Finally, through the critical exploration of my emotional engagement with the research process, a contribution is made to the call that researchers be seen as a significant part of a qualitative investigation and their emotions be recognized as significantly texturing knowledge production (CARROLL, 2013; DICKSON-SWIFT, JAMES, KIPPEN & LIAMPUTTONG 2009; GAZSO & BISCHOPING, 2018). As CARROLL (2013, p.558) stated, "the incorporation of emotions and their analysis into theoretical study on the sociology of emotion can be crucial to extending theory." Hence, I argue that the emotional engagement, intersections of identities and embodiment are not to be treated as redundant in a research process but essential to be engaged in legitimate and productive ways. Focusing on these elements and experiences during fieldwork revealed how they "can contour, compound, and contribute to the emotional [sensitive] work experienced by qualitative researchers" (LIDDIARD, 2013, p.113). Through this critical reflexive documentation of my experience researching sexuality in Nigeria, the dialogue on sharing research journeys is further expanded, deepening the conversation around the challenges, politics and complexities of this work, with the hopes that the boundaries of such investigation can be pushed beyond diseases, morality and reproduction. [60]

1) Preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis protocols <back>

2) ATLAS.ti is a computer-aided qualitative data analysis software (CAQDAS) useful in managing qualitative data. <back>

3) Figure 3 shows that researchers had adopted a quantitative methodology in most studies on sexualities in Nigeria between 2010 and 2021. <back>

4) Kayan mata is a traditional aphrodisiac made from roots, fruits, plants and animal parts. This aphrodisiac is consumed/applied through different mediums depending on the intended purpose and goal. The popular avenues through which kayan mata products are consumed include mixing it with a soda for drinking, eating it after it has been prepared as part of the ingredients of a delicacy, vaginal insertion, inhaling, spraying like perfume, artistic drawings on the body, and licking (for products that come in the form of candy). <back>

5) Juju in this context is used to describe a form of sexual desire and pleasure that is linked to powers beyond the natural. <back>

6) Nodes are central to understanding and working with NVivo; they let you gather related material in one place so that you can look for emerging patterns and ideas. You can create and organize nodes for themes or "cases" such as people or organizations. <back>

Adetutu, Olufemi; Asa, Sola; Solanke, Bola; Aroke, Abdul Rahman A. & Okunlola, David (2021). Socio-cultural and gender-based issues that shape sexuality of emerging adults in Nigeria: A qualitative approach. Research Square, June 1, https://assets.researchsquare.com/files/rs-507275/v1_covered.pdf?c=1631868403 [Accessed: July 12, 2023].

Ahlberg, Beth M. (1994). Is there a distinct African sexuality? A critical response to Caldwell. Africa: Journal of the International Institute of African Languages and Culatures, 64(2), 220-242.

Aniekwu, Nkolika I. (2006). Converging constructions: A historical perspective on sexuality and feminism in post-colonial Africa. African Sociological Review/Revue Africaine de Sociologie, 10(1), 143-160.

Barton, Len (2005). Emancipatory research and disabled people: Some observations and questions. Educational Review, 57(3), 317-327.

Bennett, Jane (2008). Editorial: Researching for life: Paradigms and power. Feminist Africa, 11, http://www.agi.ac.za/sites/default/files/image_tool/images/429/feminist_africa_journals/archive/11/fa11_entire_journal.pdf [Accessed: April 11, 2022].

Berger, Roni (2015). Now I see it, now I don't: Researcher's position and reflexivity in qualitative research. Qualitative Research, 15(2), 219-234.

Boellstorff, Tom (2012). Some notes on new frontiers of sexuality and globalisation. In Peter Aggleton, Paul Boyce, Henrietta Moore & Richard Parker (Eds), Understanding global sexualities (pp.183-197). London: Routledge.

Braun, Virginia & Clarke, Victoria (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77-101.

Bryman, Alan (2004). Social research methods. New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

Carroll, Katherine (2013). Infertile? The emotional labour of sensitive and feminist research methodologies. Qualitative Research, 13(5), 546-561.

Creswell, John W. (2014). Research design: Qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods approaches (4th ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Creswell, John W. & Creswell, J. David (2017). Research design: Qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods approaches (5th ed.). Los Angeles, CA: Sage.

Czerniewicz, Laura; Goodier, Sarah & Morrell, Robert (2017). Southern knowledge online? Climate change research discoverability and communication practices. Information, Communication & Society, 20(3), 386-405.

De Marrais, Kathleen B. (1998). Inside stories: Qualitative research reflections. London: Routledge.

Dei, George J. & Johal, Gurpreet S. (2005). Critical issues in anti-racist research methodologies. Lausanne: Peter Lang.

Denzin, Norman K. & Lincoln, Yvonna S. (2008). Introduction: The discipline and practice of qualitative research. In Norman Denzin & Yvonna Lincoln (Eds), The Sage handbook of qualitative research (pp.1-32). Los Angeles, CA: Sage.

Dickson-Swift, Virginia; James, Erica L.; Kippen, Sandra & Liamputtong, Pranee (2009). Researching sensitive topics: Qualitative research as emotion work. Qualitative Research, 9(1), 61-79.

Diener, Edward & Crandall, Rick (2016 [1978]). Ethics in social and behavioral research. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

Dowsett, Gary (2009). Facilitator notes: Introduction. Melbourne: ARCSHS.

England, Kim V. (1994). Getting personal: Reflexivity, positionality, and feminist research. The Professional Geographer, 46(1), 80-89.

Epprecht, Marc (2009). Sexuality, Africa, history. The American Historical Review, 114(5), 1258-1272.

Fletcher, Gillian; Dowsett, Gary W.; Duncan, Duane; Slavin, Sean & Corboz, Julienne (2013). Advancing sexuality studies: A short course on sexuality theory and research methodologies. Sex Education, 13(3), 319-335.

Flick, Uwe (2014). An introduction to qualitative research. Los Angeles, CA: Sage.

Foucault, Michel (2019 [1976]). The history of sexuality 1: The will to knowledge. London: Penguin.

Galam, Roderick G. (2015). Gender, reflexivity, and positionality in male research in one's own community with Filipino seafarers' wives. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung / Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 16(3), Art. 13, https://doi.org/10.17169/fqs-16.3.2330 [Accessed: July 17, 2023].

Gazso, Amber & Bischoping, Katherine (2018). Feminist reflections on the relation of emotions to ethics: A case study of two awkward interviewing moments. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung / Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 19(3), Art. 7, http://dx.doi.org/10.17169/fqs-19.3.3118 [Accessed: July 17, 2023].

Glaser, Barney G. & Strauss, Anselm L. (2017 [1967]). Discovery of grounded theory: Strategies for qualitative research. London: Routledge.

Gray, David E. (2013). Doing research in the real world. Los Angeles, CA: Sage.

Harper, Melissa & Cole, Patricia (2012). Member checking: Can benefits be gained similar to group therapy. The Qualitative Report, 17(2), 510-517, http://nsuworks.nova.edu/tqr/vol17/iss2/1?utm_source=nsuworks.nova.edu%2Ftqr%2Fvol17%2Fiss2%2F1&utm_medium=PDF&utm_campaign=PDFCoverPages [Accessed: July 17, 2023].

Hatch, Amos J. (2002). Doing qualitative research in education settings. New York, NY: Suny Press.

Ikpe, Eno B. (2004). Human sexuality in Nigeria: A historical perspective. Lagos: Africa Regional Sexuality Resource Center, http://arsrc.org/downloads/uhsss/ikpe.pdf [Accessed: July 17, 2023].

Izugbara, Chimaraoke O. (2004). Patriarchal ideology and discourses of sexuality in Nigeria. Lagos: Africa Regional Sexuality Resource Center, https://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/document?repid=rep1&type=pdf&doi=28aa3be60661d564271d95869014dc0b1ca84524 [Accessed: July 17, 2023].

Kenway, Jane & McLeod, Julie (2004). Bourdieu's reflexive sociology and "spaces of points of view": Whose reflexivity, which perspective? British Journal of Sociology of Education, 25(4), 525-544.

Kwame, Abukari (2017). Reflexivity and the insider/outsider discourse in indigenous research: My personal experiences. AlterNative: An International Journal of Indigenous Peoples, 13(4), 218-225.

Lee, Raymond M. (1993). A journey to the history of the interview. Serendipities, 1(1), https://unipub.uni-graz.at/serendipities/content/titleinfo/1314313/full.pdf [Accessed: July 12, 2023].

Lewis, Desiree (2011). Representing African sexualities. In Sylvia Tamale (Ed.), African sexualities: A reader (pp.199-216). Cape Town: Pambazuka Press.

Liddiard, Kirsty (2013). Reflections on the process of researching disabled people's sexual lives. Sociological Research Online, 18(3), 105-117.

Mason, Mark (2010). Sample size and saturation in PhD studies using qualitative interviews. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung / Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 11(3), Art. https://doi.org/10.17169/fqs-11.3.1428 [Accessed: July 17, 2023].

Maxwell, Joseph A. (2021). Why qualitative methods are necessary for generalization. Qualitative Psychology, 8(1), 111.

Mbachu, Chinyere O.; Clara Agu, Ifunaya & Onwujekwe, Obinna (2020). Collaborating to co-produce strategies for delivering adolescent sexual and reproductive health interventions: processes and experiences from an implementation research project in Nigeria. Health Policy and Planning, 35(Supplement 2), ii84-ii97, https://doi.org/10.1093/heapol/czaa130 [Accessed: July 12, 2023].

McCorkel, Jill A. & Myers, Kristen (2003). What difference does difference make? Position and privilege in the field. Qualitative Sociology, 26(2), 199-231.

Meiu, George P. (2015). Colonialism and sexuality. In Patricia Whelehan & Anne Bolin (Eds), The international encyclopedia of human sexuality (pp.197-200). Hoboken, NJ: Willey-Blackwell.

Milligan, Lizzi (2016). Insider-outsider-inbetweener? Researcher positioning, participative methods and cross-cultural educational research. Compare: A Journal of Comparative and International Education, 46(2), 235-250, https://doi.org/10.1080/03057925.2014.928510 [Accessed: July 12, 2023].

Moher, David; Shamseer, Larissa; Clarke, Mike; Ghersi, Davina; Liberati, Alessandro; Petticrew, Mark; Shekelle, Paul; Stewart, Lesley A. & PRISMA Group* (2009). Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. Systematic Reviews, 4(1), 2-9, https://doi.org/10.1186/2046-4053-4-1 [Accessed: July 15, 2023].

Naidoo, Kammila (2008). Researching reproduction: Reflections on qualitative methodology in a transforming society. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung / Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 9(1), Art. 12, https://doi.org/10.17169/fqs-9.1.338 [Accessed: July 15, 2023].

Noy, Chaim (2008). Sampling knowledge: The hermeneutics of snowball sampling in qualitative research. International Journal of Social Research Methodology, 11(4), 327-344.

Ostien, Philip & Umaru, M.J. (2007). Changes in the law in the sharia states aimed at suppressing social vices. In Philip Ostien (Ed.), Sharia implementation in Northern Nigeria 1996-2006: A sourcebook (pp.9-75). London: Spectrum Books.

Patton, Michael. Q. (2015). Qualitative research & evaluation methods (4th ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Peiretti-Courtis, Delphibe (2021). African hypersexuality: A threat to white settlers? The stigmatization of "black sexuality" as a means of regulating "white sexuality." In Alain Giami & Sharman Levinson (Eds..), Histories of sexology (pp.263-276). London: Palgrave Macmillan.

Pole, Christopher & Lampard, Richard (2015). Practical social investigation: Qualitative and quantitative methods in social research. London: Routledge.

Poulton, Emma (2012). If you had balls, you'd be one of us! Doing gendered research: Methodological reflections on being a female academic researcher in the hyper-masculine subculture of "football hooliganism". Sociological Research Online, 17(4), 67-79.

Probst, Barbara (2016). Both/and: Researcher as participant in qualitative inquiry, Qualitative Research Journal, 16(2), 149-102.

Rice, Carla (2009). Imagining the other? Ethical challenges of researching and writing women's embodied lives. Feminism & Psychology, 19(2), 245-266.

Sadler, Georgia R.; Lee, Hau-Chen; Lim, Rod S.H. & Fullerton, Judith (2010). Recruitment of hard‐to‐reach United States population subgroups via adaptations of the snowball sampling strategy. Nursing and Health Sciences, 12(3), 369-374.

Sarantakos, Sotirios (2012). Social research. London: Macmillan.

Saunders, Mark N.K; Lewis, Philip & Thornhill, Adrian (2009). Research methods for business students. London: Pearson Education.

Schäfer, Mike S. & Schlichting, Inga (2014). Media representations of climate change: A meta-analysis of the research field. Environmental Communication, 8(2), 142-160.

Sekaran, Uma & Bougie, Roger (2016). Research methods for business: A skill building approach. Chichester: Wiley.

Silverman, Henry I. (2009). Qualitative analysis in financial studies: Employing ethnographic content analysis. Journal of Business & Economics Research (JBER), 7(5), 133-136, https://doi.org/10.19030/jber.v7i5.2300 [Accessed: July 12, 2023].

Smith, Andrea (2018). Unsettling the privilege of self-reflexivity. Victoria: Camas Books.

Smith, Andrew R.; Colombi, John M. & Wirthlin, Joseph R. (2013). Rapid development: A content analysis comparison of literature and purposive sampling of rapid reaction projects. Procedia Computer Science, 16, 475-482, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.procs.2013.01.050 [Accessed: July 12, 2023].

Sultana, Farhana (2007). Reflexivity, positionality and participatory ethics: Negotiating fieldwork dilemmas in international research. ACME: An International Journal for Critical Geographies, 6(3), 374-385, https://acme-journal.org/index.php/acme/article/view/786/645 [Accessed: July 12, 2023].

Surmiak, Adrianna (2018). Confidentiality in qualitative research involving vulnerable participants: Researchers' perspectives. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung / Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 19(3), Art. 12, https://doi.org/10.17169/fqs-19.3.3099 [Accessed: July 12, 2023].

Swain, Jon & Spire, Zachery (2020). The role of informal conversations in generating data, and the ethical and methodological issues they raise. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung / Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 21(1), Art. 10, https://doi.org/10.17169/fqs-21.1.3344 [Accessed: July 12, 2023].

Tamale, Sylvia (2008). The right to culture and the culture of rights: A critical perspective on women's sexual rights in Africa. Feminist Legal Studies, 16(1), 47-69.

Tamale, Sylvia (2011). Researching and theorising sexualities in Africa. In Sylvia Tamale (Ed.), African sexualities: A reader (pp.11-36). Nairobi: Pambazuka.

Tamale, Sylvia (2014). Exploring the contours of African sexualities: Religion, law and power. African Human Rights Law Journal, 14(1), 150-177.

Wacquant, Loc J. & Bourdieu, Pierre (1992). An invitation to reflexive sociology. Cambridge: Polity.

Walby, Sylvia (2011). The impact of feminism on sociology. Sociological Research Online, 16(3), 158-168.

Weeks, Jeffrey (2003 [1986]). Sexuality (2nd ed.) London: Routledge.

Weimann, Gunnar J. (2010). Islamic criminal law in Northern Nigeria: Politics, religion, judicial practice. Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press.

Yardley, Lucy (2015). Demonstrating validity in qualitative psychology. Qualitative Psychology: A Practical Guide to Research Methods, 2, 235-251.

Yin, Robert K. (2011). Qualitative research from start to finish. New York, NY: Guilford Publications.

Dr. Oluwatobi Joseph ALABI is a Global Excellence Stature postdoctoral research fellow at the Department of Sociology, University of Johannesburg. His research interests include gender and sexuality, family and reproductive health, poverty and inequality, education, and youth and development. He has taught at the Department of Sociology, University of KwaZulu-Natal and the Centre for General Education at the Durban University of Technology South Africa.

Contact:

Oluwatobi Joseph Alabi, PhD

Department of Sociology

University of Johannesburg

Auckland Park, Johannesburg South Africa

E-Mail: damilarealabi40@yahoo.com

Alabi, Oluwatobi (2023). Critical reflection on sexuality research in Nigeria: Epistemology, fieldwork and researcher's positionality [60 paragraphs]. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung / Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 24(3), Art. 10, https://dx.doi.org/10.17169/fqs-24.3.3972.