Volume 24, No. 2, Art. 13 – May 2023

Transgressing the Linguistic Domain: The Transformative Power of Images in Magnus Hirschfeld's Sexological Work

Robin K. Saalfeld

Abstract: Transgender individuals have historically faced exclusion from social research, a systemic issue rooted in a lack of historical information. However, a comprehensive understanding of contemporary transness necessitates examining its history. In this article, I address early forms of visual representation of transness by focusing on HIRSCHFELD's sexological work on intermediate sex categories at the beginning of the 20th century. The objective of this article is twofold. Firstly, I examine visual methods derived from discourse analysis and grounded theory methodology for analyzing and interpreting images as cultural documents. Secondly, I apply a discourse-analytical research perspective and follow suggestions made by CLARKE (2005) to explore the influence of images on the development of discourse on transness. By demonstrating the diverse meanings conveyed through HIRSCHFELD's image use, which sometimes differ significantly from his written work, I illustrate that images have the potential to shape and transform social knowledge production beyond the linguistic domain. I conclude with suggestions for advancing methods in the field of visual sociology.

Key words: visual analysis; visual sociology; visual data; grounded theory methodology; discourse analysis; transgender; homosexuality; hermaphroditism; queer; sexology

Table of Contents

1. Introduction

2. Sociological Research With Images

2.1 Approaching visuality in discourse analysis

2.1.1 Semiotic visual discourse analysis

2.1.2 Sociological visual discourse analysis

2.2 Approaching visuality in grounded theory methodology

2.2.1 Visuality and situational analysis

2.2.2 Multislice imagining

2.2.3 Visually-oriented grounded theory methodology

2.3 Interim conclusion: Images in qualitative research

3. Visuality in the Work of Magnus HIRSCHFELD

3.1 Research design

3.2 The visuality of homosexuality as a form of hermaphroditism

3.3 Visuality of transvestism

3.4 Contextualizing results in language-based discourse

4. Conclusions

The concept of transness refers to persons whose sex assignment at birth does not align with their gender identity, gender expression and/or gender role. It includes people "moving away from the birth-assigned sex and gender" (STRAUBE, 2014, p.32), and nowadays there is a rich variety of terms transgender people use for describing their gender identity, such as transgender, transsexual, trans*, non-binary, etc. The increasing social awareness of different gender identities, gender expressions and/or gender roles is an effect of transgender activists fighting ongoing battles "advocat[ing] a social arrangement in which one is free to assign her or his own sex (or non-sex, for that matter)" (KOYAMA, 2003, p.250). [1]

Transgender activism has its roots in the early 20th century, where it was closely intertwined with the emergence of sexology, a field dedicated to understanding sex, gender, and sexual behavior (STRYKER, 2017 [2008]). However, the understanding of transness at that time was vastly different from what we understand today. Transness indicating a broad spectrum of gendered self-descriptions as we understand it now was originally introduced into medical discourse as an issue of mental pathology, referred to as "transvestism." This introduction was connected to debates about hermaphroditism and homosexual behavior (HIRSCHAUER, 2015 [1993]). While sexological discussions about hermaphroditism circled around the question of normal and deviantly-sexed bodies, sexologists problematized homosexual behavior as a mental matter potentially leading to a gendered inversion of the entire personality where a man would identify as female, and vice versa. By this problematization, homosexual behavior was framed as "mental hermaphroditism" and it was associated with the idea of deviantly-sexed bodies. This discursive link between sexual behavior and the sexuation of bodily characteristics resulted in the emergence of transvestism as a sexological concept. [2]

Magnus HIRSCHFELD, a German sexologist and one of the key figures in the liberation of sexual minorities in the first half of the 20th century, introduced the term "transsexualism" (1923, p.15), which is still in use in medical discourse today. However, it was not until the 1950s that professionals differentiated transsexuality categorically from homosexuality, hermaphroditism and especially transvestism (VETTER, 2010, p.105). Doctors then developed rigid treatment plans for transsexual patients (HIRSCHAUER, 2015 [1993]), which were structured around binary notions of gender. These treatment plans were highly inflexible and left little room for individual differences. "Transsexualism" was officially included in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual (DSM-III) in 1980, and it is generally understood now that medical sciences have taken the lead in defining transness. [3]

Interestingly, sexologists at the beginning of the 20th century were increasingly engaging in these matters by using visual methods and visual material (PETERS, 2010; SAALFELD, 2020; SYKORA, 2004). This inclusion of visuality coincided with the rise of photography as a new communication medium. The influential work of HIRSCHFELD relied heavily on visual material. He used a rich repertoire of photographs showing transvestite, intersex and homosexual people in order to demonstrate his theory of the diverse nature of the human sexes and genders (HERRN, 2005, p.19). [4]

Images contribute immensely to the social construction of knowledge about gender (LÜNENBORG & MAIER, 2013). In the humanities and due to a general increase in the consumption of images in contemporary society, art historians have shown that the social world was not only being represented in images but that it was co-produced by images (MITCHELL, 1994, p.41). For the past four decades, in differentiation and in addition to advances in art history and cultural studies, sociologists have also become increasingly interested in studying visuality (for an overview of the history of visual analysis in qualitative research, see: SCHNETTLER & RAAB, 2008). At this point in time, no-one seeks to argue against the fact that images create meaning equivalent to language. However, the development of substantial methods for accessing the social meaning of images is still ongoing. As a consequence, theoretical underpinnings for studying visuality remain rather atomized (KRESS & VAN LEEUWEN, 2021 [1996], pp.23-24). Due to the emerging nature of the field, there is a wide variety of ways for conducting visual analyses (KNOBLAUCH, BAER, LAURIER, PETSCHKE & SCHNETTLER, 2008). Most researchers in qualitative social research have worked out ad-hoc solutions for their studies (ERIKSSON & KOVALEINEN, 2008, p.43). Nonetheless, some approaches have been more prominent than others. While early considerations arose from a discourse-analytical background (CLARKE, 2005; KRESS & VAN LEEUWEN, 2021 [1996]; MALHERBE, SUFFLA, SEEDAT & BAWA, 2016; ROSE 2001), some have been developed later in the realm of grounded theory methodology following the famous notion that "all is data" (GLASER, 1998, p.8; e.g., BRECKNER, 2010; KAUTT, 2017; MEY & DIETRICH, 2016; SCHOLZ, KUSCHE, SCHERBER, SCHERBER & STILLER, 2014). [5]

This paper is divided into two main parts. In the first part, I offer an overview of the visual methods available in sociology to analyze and interpret images as cultural documents, rather than documentation of natural situations. In Section 2, I outline some key methodological approaches from the tradition of discourse analysis (DA) (Section 2.1) and grounded theory methodology (GTM) (Section 2.2). The first part ends with an interim conclusion (Section 2.3). In the second part of the paper I present an empirical example of a visual study on transness, which is based on a study about the visuality of transgender people I conducted from 2015 to 2019 at Friedrich-Schiller-University Jena (SAALFELD, 2020). In Section 3, I apply both methodological approaches (DA and GTM) in a qualitative analysis of images on transness in HIRSCHFELD's work. The empirical part is divided into three sections: In Section 3.1, I address the research design of the study, in Sections 3.2 and 3.3, I analyze the visual data from HIRSCHFELD, and in Section 3.4, the findings are contextualized within the language-based discourse of the specific historical period. The paper ends with final remarks (Section 4). It is important to note that while I present an empirical example of a visual study on transness in this paper, I do not aim to provide a comprehensive analysis of transness in visual media. For a more in-depth analysis of the visual representation of transgender people, readers can refer to SAALFELD (2020). [6]

2. Sociological Research With Images

Since the 1990s, a growing focus on the theoretical, methodological, and empirical aspects of images and visual media has emerged in both the humanities and social research. In previous studies, it was suggested that images convey meaning that is distinct from verbal text (KRESS & VAN LEEUWEN, 2021 [1996]), and that images do not simply mirror the social world but instead express a relationship to it through their aesthetic structures (BOEHM, 2008; see also BARTHES, 1973 [1957]; VAN LEEUWEN, 1991). However, images are never isolated from language-based discourse, and the meaning conveyed by an image is shaped by the relationship between the visual communication and the wider discourse about the subjects and objects depicted. Consequently, images possess both expressive and social properties, and their relationship to social reality is complex (BRECKNER, 2010). In light of this complexity, researchers must consider both expressive and social properties when using images as research objects in qualitative research. [7]

In the realm of social research, there has been a discussion about how to systematically approach images by considering both their social embeddedness (social properties) and their aesthetic structures (expressive properties). Scholars in the fields of DA and GTM have explored this methodological approach. Both fields are described below, according to their contribution towards a visual sociology. [8]

2.1 Approaching visuality in discourse analysis

Proponents of DA have attempted to include visuality as a fundamental "aspect and element of social and cultural orders and practices sui generis" (TRAUE, BLANC & CAMBRE, 2019, p.327). Norman FAIRCLOUGH, one of the founders of critical discourse analysis (CDA), advocated for the extension of discourse beyond spoken or written language use to "include other types of semiotic activity (i.e., activity which produces meaning), such as visual images" (1995, p.54). Scholars have since recognized that discourse can take both verbal and non-verbal forms (WEKESA, 2012), due to the prevalence of multi-modal communication (HART, 2016; JOHNSTONE, 2018 [2002]; MACHIN, 2013). Considered "actual instances of discourse" (JOHNSTONE, 2018 [2002], p.16), images were analyzed either as analytical pieces articulating discourse (ROSE, 2001) or as having a discourse-transformative function (MAASEN, MAYERHAUSER & RENGGLI, 2006). In some studies, scholars have accommodated both approaches (CHRISTMANN, 2008; SEKO, 2013), while a few have suggested that images could establish discourses themselves (BETSCHER, 2013). This called for specific research methods that diverged from those addressing linguistic discourses (BLEIKER, 2015). Even though proponents of visual discourse analysis (VDA) developed suitable methods (CHRISTMANN, 2008; FAIRCLOUGH, 1995; KRESS & VAN LEEUWEN, 2021 [1996]; MALHERBE et al., 2016; ROSE, 2001), such methods are still less evolved than those studying linguistic discourses. Additionally, studies focusing on the discursive status of visuality in relation to gender are still lacking. [9]

Due to the novel nature of the field, there is no one way to conduct VDA. This has to do (a) with the general fact that there is a wide variety of definitions of what actually constitutes a discourse (KELLER, 2011 [2004], p.9). Even FOUCAULT who was central to developing the concept, and whose poststructuralist approach has been widely adopted in French and German contexts, did not implement the term unambiguously in his oeuvre (KNOBLAUCH, 2005). In British and US-American contexts, semiotic approaches prevailed and proponents applied a more straightforward definition of discourse. The variety of analytical programs is also (b) a result of the distinct academic disciplines analysts came from. Discourse researchers deriving from linguistics applied other analytical strategies (and aimed at answering different research questions) than those in (poststructuralist) sociology. In the following pages, the weaknesses and strengths of both approaches (semiotic VDA and sociological VDA) are examined by drawing on KRESS and VAN LEEUWEN's (2021 [1996]) visual semiotic theory, and ROSE's (2001) visual methodology. [10]

2.1.1 Semiotic visual discourse analysis

KRESS and VAN LEEUWEN's (2021 [1996]) grammar of visual design belongs to the earliest and most influential approaches for conducting VDA (HART, 2016, p.336). The authors drew on the social semiotic approach developed by British linguist HALLIDAY (1978) to analyze how social meaning is made by the grammar of visual images. It was HALLIDAY's systematic functional model that they—among others (see e.g., LIM, 2004; O'HALLORAN, 2004; SEKO, 2013)—adopted as a theoretical framework. In his study of language as a semiotic system, HALLIDAY (1978) found that it was semiotic resources that were creating meaning. He argued that language was structured by three configurations, each of which represented a distinct function (ideational function, interpersonal function, textual function). KRESS and VAN LEEUWEN (2021 [1996]) consequently proposed that, just like language, images contained grammatical structures which needed to be analyzed. They stressed that "language and visual communication both realize the same more fundamental and far-reaching systems of meaning that constitute our cultures, but that each does so by means of its own specific forms, and independently" (p.17). Hence, KRESS and VAN LEEUWEN differentiated two levels of discourse: language-based discourse and visual discourse, each of which consisted of differing elements (texts vs. visuals) and operating with differing grammatical structures. But the authors claimed that both of these levels belonged to the same "system of meaning" (ibid.) in Western societies. To them, visual discourse served the three metafunctions that HALLIDAY (1978) had claimed for language as a semiotic system:

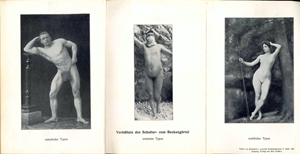

textual metafunction: the capability of images to connect visual elements together to a unified whole;

interpersonal metafunction: images forming a social relationship between the image's producer and the viewers;

ideational metafunction: images representing people's experiences of the world which are connoted by and lie behind the content. [11]

In order to access these metafunctions, KRESS and VAN LEEUWEN (2021 [1996]) suggested a wide spectrum of visual parameters which analysts needed to decode. These parameters ranged from vectorial patterns via classificational, analytical and symbolic processes, to gaze, distance, angle relations, the use of color and light, framing and zoning devices. However, it was unclear how these visual grammar structures related to one another (FORCEVILLE, 1999). It also remained unclear how the parameters could be practically applied in analyses of specific images (ibid). Other pitfalls concerned KRESS and VAN LEEUWEN's (2021 [1996]) use of binary categories structuring the parameters (such as foreground-background, bright-dark, left-right, close-far, etc.), and a tendency to essentialize parameter values. Additionally, a sociological interpretation of images requires theories connected to analytical results (JEWITT & OYAMA, 2001). This theoretical perspective was missing from their analytical toolkit. So, even though KRESS and VAN LEEUWEN (2021 [1996]) provided a comprehensive framework for analyzing the expressive properties of images, relatively little was understood about the significance of the visual grammar within a particular discourse (social properties). [12]

2.1.2 Sociological visual discourse analysis

British sociologist ROSE (2001) outlined a critical visual methodology in which she introduced several methods and perspectives for researching visual material. She touched on two varieties of DA following a Foucauldian understanding. She distinguished between 1. a DA where images (and verbal texts, for that matter) were regarded and examined as discursive articulations, and 2. a DA where researchers focused mainly on institutional practices and ways of seeing. Even though these two types might overlap, it is indicated that visual material needs to be addressed differently. While images of all sorts could potentially be included in both types, qualitative researchers using the first type would be concerned with "the production and rhetorical organization of visual and textual materials" (p.164). Hence, there is a focus on image content and structure in the first type, and ROSE suggested key research strategies such as (pp.149-163):

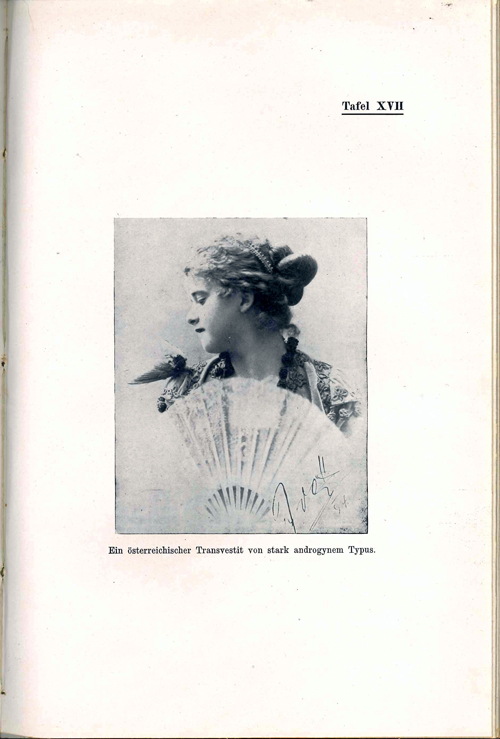

looking at images while suspending preconceived notions;

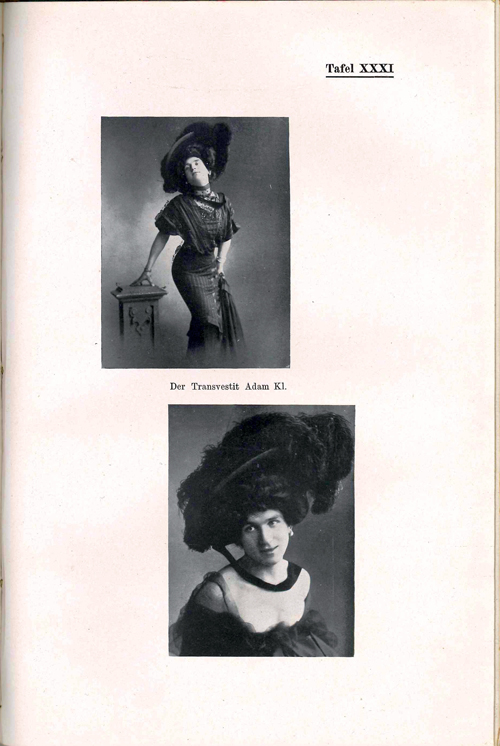

immersing oneself in these images;

discovering key themes;

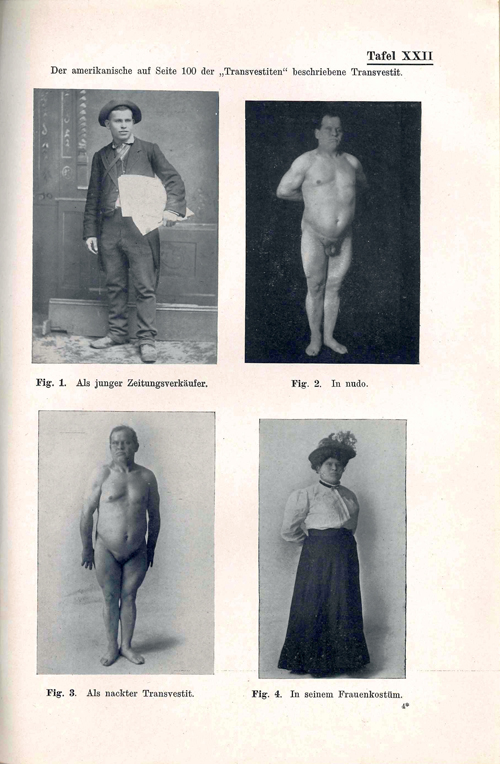

observing effects of truth;

focusing on complexity and contradictions;

considering the invisible as well as the visible;

concentrating on visual details. [13]

However, specific instructions on how to apply these strategies were missing (LICHTMAN, 2002). Researchers applying the second type would examine how images had been produced by, and reiterate, specific institutions and their practices. Applicants would, therefore, subordinate visual material to an analysis of technologies or dispositive, where extensive additional data (historical sources, social practices, etc.) would be required. [14]

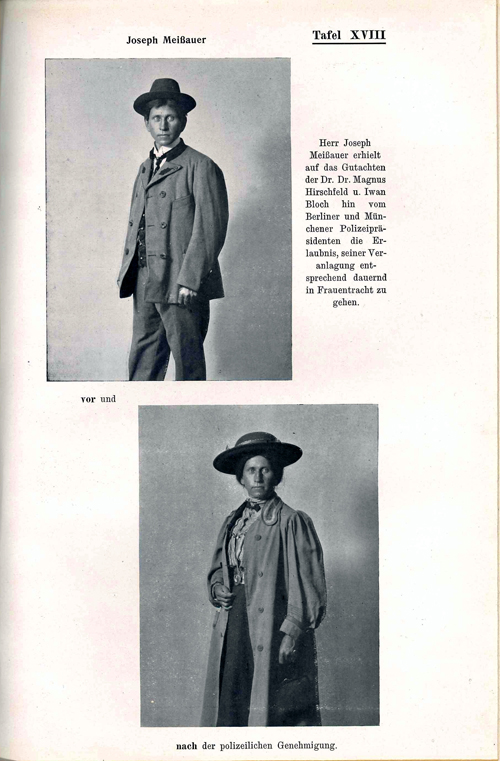

2.2 Approaching visuality in grounded theory methodology

Developed by GLASER and STRAUSS in their book "The Discovery of Grounded Theory: Strategies for Qualitative Research" in 1967, GTM is both a methodology and a specific way of doing research in qualitative social research. Situated in the interpretative paradigm, GLASER and STRAUSS originally intended to outline a bundle of research strategies bridging the gap between theory and empirical research with the aim of improving the relation between empirical findings and the development of theory. Grounded theorists seek to develop theory which is "derived from data, systematically gathered and analyzed through the research process" (STRAUSS & CORBIN, 1998 [1990], p.12). Different generations of GTM scholars emerged during the decades following "The Discovery of Grounded Theory" (GLASER & STRAUSS, 1967). Their proponents not only developed distinct GT approaches, but modified GTM's central research strategies (CHARMAZ, 2006; CLARKE, 2005; GLASER, 1978; MORSE et al., 2009; STRAUSS, 1991 [1987]; STRAUSS & CORBIN, 1998 [1990]). Despite existing differences, key principles still comprise 1. a circular research process alternating between data collection, data analysis and interpretation, 2. coding (open, axial, selective) as a central means of developing theory, 3. applying the principle of theoretical sampling, and 4. an iterative comparison of data. [15]

Even though GTM is usually applied as a research style for analyzing interviews, GLASER held that "all is data" (GLASER, 1998, p.8), a dictum that became prominent in various social studies integrating different types of data. GLASER and STRAUSS (1967) indicated that diverse forms of data, such as documents, statistics, interviews, newspaper articles, casual comments, etc., needed to be examined which would ultimately direct to the development of a theory. Yet, in all the text books teaching principles of GTM, the analysis of visual data was barely acknowledged, neither as primary nor as supplementary data (KONECKI, 2011, pp.133f.). It is only in recent years that GTM has been shown to be a suitable framework for analyzing visual communication (KAUTT, 2017), and only a few attempts have been made to develop specific visual methods (CLARKE, 2005; KONECKI, 2011; MEY & DIETRICH, 2016). Those will be reviewed briefly below. [16]

2.2.1 Visuality and situational analysis

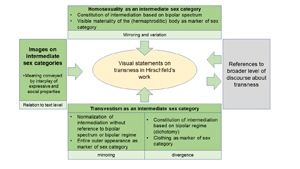

CLARKE provided an instructive methodological program for examining visuality in "Situational Analysis" (2005) in which she connected GTM with FOUCAULT's concept of discourse (e.g., 1989 [1961], 1990 [1966]) in order to allow for the complexities and differences of a postmodern world, and in order to reconcile the methodological gap between GTM and DA. Referring to the postmodern turn, CLARKE acknowledged cultural objects, technology, and the media to be central elements in shaping social situations/social worlds, and "we can [...] seek to understand how visuality is constitutive of those situations, and come to fuller terms with their rich and dense contributions to social life" (2005, p.205). [17]

CLARKE suggested writing (and coding) three types of analytical memos as core strategies for analyzing visual material. These memos correspond to GTM's basic technique of open coding segment-by-segment: locating memos (first step), big picture memos (second step) and specification memos (third step). In locating memos, researchers address the production context of images: The memo contains information about the image's place and date of origin, its creator and its audience (if known). In big picture memos, first impressions regarding the image's content are then recorded. In specification memos, researchers are not concerned with what is shown in an image (content), but rather how it is shown (form or visual structure). With this third step, which CLARKE characterized as "break[ing] the frame" (p.227), researchers focus on several aesthetic structures ranging from modes of selection, montage, framing, situatedness of visual figures, lightning, color, composition, proportion, referencing, modes of normalization, etc. Specification memos, therefore, function as a valuable means for analyzing the visual structure of images (expressive properties), and they can be regarded as a practical implementation of ROSE's (2001) first type of DA mentioned above. [18]

However, it needs to be noted that the consideration of visual material is only one element in conducting a situational analysis (SA), according to CLARKE (2005). It is debatable whether CLARKE's suggestions on analyzing visual material are even part of a visual sociology. In the German version of "Situational Analysis" (CLARKE, 2012), for example, the entire chapter on visuality was left out. Neither was her chapter regarded essential for understanding CLARKE's methodological program of SA, nor was it acknowledged in the field of visual sociology. [19]

KONECKI was one of the first to try to outline a visual grounded theory methodology (VGTM). Following STRAUSS' (1978) concept of social worlds, KONECKI (2011) proposed "a grammar of visual narrations analysis" (p.131) which he called "multislice imagining." He focused on visual processes, interactions and phenomena and concentrated on the multiple contexts ("layers") in which visual processes are embedded: 1. context of creation/production, 2. context of presentation, 3. image's content and style, and 4. reception context (pp.139ff.). KONECKI also involved research strategies typical for GTM, such as constant comparisons and theoretical sampling. [20]

In order to gain information about layers 1., 2. and 4., KONECKI suggested using common ethnographic methods, such as participant observation, interviews, memo-writing or surveys, while for layer 3., he remained less instructive in terms of an in-depth analysis. He argued that an image's content and its aesthetic structures needed to be described and then coded openly and selectively (p.142). However, he did not specify a procedure by which to describe and then code an image's composition. KONECKI's concept of a VGTM, therefore, is designed especially for studies that address the relations between different interaction contexts in which visual material is produced and circulated. It is less tailored to conducting research into images, their style and their intrinsic logic (expressive properties). [21]

2.2.3 Visually-oriented grounded theory methodology

MEY and DIETRICH (2016) picked up the discussion on approaching an image and its visual structure as a research object in and of itself. Drawing on different visual methods developed in German debates, such as an interpretation of images via objective hermeneutics (PEEZ, 2006), documentary method (BOHNSACK, 2008), and BRECKNER's segment analysis (2010), they introduced an analytical model which consisted of the following steps (MEY & DIETRICH, 2016, pp.42-57):

contextualizing an image (similar to KONECKI's [2011] analysis of Layer 1);

describing an image's compositional elements (dimensionality, perspective, etc.);

breaking down the image into distinct segments (similar to BRECKNER's [2010] suggestions);

memo-writing and open coding in regard to all segments and their interrelation (multiple coding of elements is advised);

interpretation;

category building;

sampling;

integration of image-text-relations. [22]

MEY and DIETRICH (2016) emphasized the importance of tailoring each step, especially contextualization, coding, interpretation, and category building, to the specific research question. In the project on the visual construction of transness in HIRSCHFELD's work, I focused on the visual orchestration of images and the impact of their properties on discourse: Examining the compositional elements of images individually and in relation to one another, as well as the images' social embeddedness, was crucial. It was of less importance to break down images into smaller segments, as MEY and DIETRICH (2016) proposed. Nonetheless, their approach needs to be appreciated in visual sociology because it provides a useful framework for implementing a VGTM based on established procedures for analyzing images in qualitative social research. [23]

2.3 Interim conclusion: Images in qualitative research

Qualitative sociologists approach visual analysis from two distinct perspectives. Researchers applying a cultural-analytical perspective see images as research objects in and of themselves, with images "becoming primary forms of knowledge communication, especially for understanding and interpreting historical, social and cultural realities" (SCHNETTLER & RAAB, 2008, §22). This perspective contributes to the social construction of knowledge about phenomena, such as transness, via images and is the focus of this explanation. A second perspective would be to use cameras to document natural situations. This naturalistic or interaction-analytical perspective aims at analyzing the structures of social situations, not images. [24]

It was shown that images convey meaning in ways that are vastly different from verbal texts because they possess unique expressive and social properties. Art historians recognized that images and their aesthetic structures had an intrinsic logic and productivity that cannot be compared to language (image's expressive properties), but images are also no sole pieces of art. They are embedded in language-based discourse (image's social properties). To reconcile these two notions, visual sociologists have developed methodical programs, with DA and GTM being particularly relevant to this discussion. [25]

By examining these methodical programs, I revealed that KRESS and VAN LEEUWEN (2021 [1996]) prioritized aesthetic structures in their semiotic VDA, enabling researchers to identify minute visual parameters, but their analyses remained descriptive and lacked a connection to the social properties of images. KONECKI (2011) and ROSE (2001) prioritized images' social properties, but their suggested research strategies provided less guidance in examining an image's expressive properties. CLARKE (2005) and MEY and DIETRICH (2016) offered research programs that considered both expressive and social properties, with CLARKE's (2005) ideas being particularly suitable for the study of HIRSCHFELD's image use. [26]

The objective of this study was to investigate the influence of images on the development of discourse, with a specific focus on historical representations of transness in sexology. It was assumed that images possess both expressive and social properties. To explore this, images from HIRSCHFELD's archive were analyzed, to serve as examples for the analysis. The following section details the analytical steps taken to examine HIRSCHFELD's images. [27]

3. Visuality in the Work of Magnus HIRSCHFELD

HIRSCHFELD is renowned as one of the first advocates of homosexual and transgender people. He was one of the founders of the Scientific-Humanitarian Committee which targeted research into sexual minorities in order to eliminate the criminalization of homosexuality and transvestism in the first half of the 20th century (HERRN, 2005, p.19). His doctrine about sexuelle Zwischenstufen [sexual intermediaries] (HIRSCHFELD, 1899, p.1) must be considered a milestone in the emancipation of transgender people. Like no other sexologist doctrine, it contained a rich number of images exemplifying the findings. HIRSCHFELD's handling of visual material must be characterized as unique in sexology (PETERS, 2010, p.164) making it especially valuable for a better understanding of the social construction of gender via images. [28]

Transgender individuals have historically been excluded from social research, and have therefore remained neglected subjects. This is largely due to the lack of historical information available on transness. However, to fully understand the contemporary phenomenon of transness, it is necessary to consider its history. In this study, the role of images as drivers of knowledge-production was considered. In order to gain insight into the role that images play in the social construction of sexological knowledge about transness, a queer methodology was appropriated—"a scavenger methodology that uses different methods to collect and produce information on subjects who have been deliberately or accidentally excluded from traditional studies of human behavior" (HALBERSTAM, 1998, p.13). Adhering to principles of openness and flexibility, this exploratory methodology meant:

combining two methods that are typically kept separate: DA as a research perspective, and CLARKE's (2005) method for analyzing images;

following a general understanding of discourse instead of deciding on a discipline-specific definition;

for in-depth analysis, using a practical method instead of choosing a well-established method. Suitability is more important than credibility;

modifying analytical steps suggested by CLARKE instead of obeying analytical rigor;

lowering one's sights concerning sampling and theoretical saturation because of restricted access to historical data. [29]

This "scavenger methodology" (HALBERSTAM, 1998, p.13) was essential in uncovering important insights into the role of images in the social construction of knowledge about transness. The combination of a discourse-analytical research perspective with analytical steps suggested by CLARKE (2005) provided a comprehensive framework for capturing the twofold nature of images, which possess both expressive and social properties. In other words, images function both as articulations of discourse and as productive agents that influence the construction of social reality. Discourse was broadly defined as a system of knowledge production that involves the use of language and other symbolic forms, such as images, to convey meaning within a particular historical, cultural, and institutional context. [30]

The system of knowledge production, or discourse, consists of multiple levels, with images belonging to one level and written or spoken statements about transness belonging to another. To fully comprehend the significance of the visual level, an analysis that integrates both visual and language-based levels was required. This analytical approach involved exploring the ways in which the images were "read" and how they related to the discourse on transness during the first half of the 20th century. Extensive historical knowledge is needed to conduct such analysis (SCHOLZ et al., 2014). Therefore, in this study, an in-depth visual analysis was performed to shed light on discursive shifts in the field of sexology, with these shifts being inferred through a review of literature about discursive developments pertaining to transness. [31]

In the in-depth analysis of the images, I drew on CLARKE's (2005) approach to treating images as "discursive cultural products of particular [...] disciplines" (p.219), despite the approach's limited use in visual sociology. To guide the analysis of HIRSCHFELD's images, I followed CLARKE's (2005) suggestions on memo-writing (see Section 2.2.1), which included locating memos, big picture memos, and specification memos, with a focus on the latter for in-depth analysis. The open, axial, and selective coding techniques were utilized to code all the memos by me, followed by interpretation and category building. It is worth noting that memo writing and coding are concurrent analytical activities in qualitative research, and the memos themselves included codes. [32]

An interpretation group comprising both cisgender and transgender individuals (n=4) assisted in interpretation and category building, as well as in sampling the visual material. Although access to all of HIRSCHFELD's images on sexual intermediaries was not possible, the Magnus-Hirschfeld-Gesellschaft e.V.'s [Magnus Hirschfeld Society] internet database provided access to the majority of them. The selection process for in-depth analysis was guided by GADAMER's (1986 [1959], p.64) principle that "the first step of understanding is that something appeals to us."1) To ensure a comprehensive analysis, I employed the GTM techniques of minimal and maximal contrasting, which involved selecting images captured by HIRSCHFELD himself, as well as those taken by trans individuals inserted into his publications. In addition, the analysis included various sexual intermediaries ranging from homosexuality to transvestism, as the boundaries between these phenomena were still ambiguous in the early 20th century. [33]

All in all, the following analytical steps were taken:

screening HIRSCHFELD's visual material;

selecting images for in-depth analysis;

in-depth analysis according to CLARKE (2005): memo-writing and coding;

interpretation and category building, in combination with minimal and maximal contrasting (steps two to four overlap because of the cyclical nature of those analytic activities);

contextualizing results in language-based discursive developments based on literature review. [34]

My analysis of HIRSCHFELD's visual archive was a specific case study conducted as part of a broader study on the role of visuality in the discourse surrounding transness (SAALFELD, 2020). Therefore, it should be viewed within this larger context. The overall study also encompassed examinations of visual depictions of transness in both mainstream media and within trans subculture. [35]

3.2 The visuality of homosexuality as a form of hermaphroditism

The analysis started with an image plate where HIRSCHFELD attempted to illustrate his doctrine of intermediary sexes2) for the first time (Figure 1). Besides the fact that it captured my attention, the plate was selected because it was the starting point of HIRSCHFELD's image use. I consolidated the information from the locating memo and big picture memo into a single memo, and it contained the following information:

"In the fifth issue of the Jahrbuch für sexuelle Zwischenstufen [Yearbook of Sexual Intermediaries], Hirschfeld attempted to illustrate his concept of the 'uran,' which was the starting point of his doctrine, by comparing three images [Figure 1]. The pictorial comparison belongs to the sub-chapter 'Absolute necessity of homosexuality' (pp.125-138) which was part of the paper 'Cause and character of uranism' (Hirschfeld, 1903). The plate as well as the entire publication addressed an academic audience (sexologists). I do not know whether Hirschfeld himself produced the three images. I suspect the third image (on the right) is a reproduction of someone else's canvas painting. The first image (on the left) could be a photograph Hirschfeld took. The image in the middle seems like a private photograph. My first impression is that Hirschfeld tried to identify the smooth transitions between 'male type' and 'female type' (p.129), and he seemed to refer to stereotypical depictions of maleness and femaleness" (Memo, May 13, 2017).

Figure 1: The "uran type" in contrast to the "male" and "female type" (HIRSCHFELD, 1903, p.129).3) Please click here for an enlarged version of Figure 1. [36]

The memo provides initial insights, including previously unknown information such as the producer of the images in Figure 1, as I reflect on it. Additionally, in the memo I establish a link between the images and their accompanying textual information (chapter titles, captions), indicating that the initial stages of the comprehensive visual analysis are not solely based on visual data. This link also highlights the social nature of the images. Furthermore, reflections on images, captured through memos, generate verbal data that complement the visual data. [37]

In the specification memo, I addressed the expressive properties of the images in Figure 1. The memo contained detailed descriptive data of the images' aesthetic parameters, such as figure pose, foreground-background relation, figure-observer relation, and gazing:

"The left image functioning as a demonstration of the 'male type' (ibid.) shows a naked person whose genitals are covered by a leaf. Above the black background, the figure's defined muscles become clearly visible and it strikes a pose that points to its athletic body. The figure leans nonchalantly on a column making a wide lunge, and addresses the observer directly. The right image which represents the 'female type' (ibid.) functions as the pole contrasting the sexual intermediary, together with the left image. Here, the figure crossing its legs and holding a thin spear in the right hand is elegantly embedded in an idyllic landscape with a body of water visible in the background. By softly looking into the space-off, the 'female type' (ibid.) becomes the voyeuristic object of the observer's gaze. Hirschfeld placed the sexual intermediary—the 'uran type' (ibid.)—right in the middle. The image shows a naked person whose bodily characteristics cannot easily be defined as male or female. The person wearing a light scarf above half of its face, which grants it anonymity to some extent, also gazes at the observer. In contrast to the other figures, the 'uran type' (ibid.) interacts less with the scenery into which it is placed. It seems as if it is the observer for whom the figure is striking this almost theatrical pose for. By its gesture, the figure not only illustrates itself proudly, it also hints to the fact that it was discovered as the uran" (Memo, May 14, 2017). [38]

In the subsequent analysis phase, the interpretation group and I collaboratively examined the memos to generate preliminary insights on interpretation and category construction. We identified a visual style of intermediation that defined HIRSCHFELD's pictorial reasoning: In the uran type image, an ambiguously-sexed body is represented because the uran's body incorporates both male and female bodily signs. The "uran gestures" can also be seen as a combination of the stereotypical ways of representation of both sexes. So, HIRSCHFELD utilized hermaphroditic motives to represent the sexual intermediary, reflecting his verbal reasoning: HIRSCHFELD's doctrine of sexual intermediaries was based on an intersexual scheme of constitution and variation, as he believed that "the human being is not a man or a woman, but a man and a woman" (HIRSCHFELD cited in RUNTE, 1996, p.97). [39]

However, in contrast to his textual works, HIRSCHFELD's pictorial series in Figure 1 addresses homosexuality as a bodily phenomenon rather than a product of mental characteristics: Although he explained the uran type in his doctrine as representing homosexuality based on sex drive levels, in the image plate he portrayed it as a tangible aspect, as "visible materiality" (PETERS, 2010, p.168). The images in Figure1 also demonstrate HIRSCHFELD's binary perspective, as the intermediating sex is continually contextualized within a bipolar regime of sexes, which was the dominant paradigm in medicine at that historical period. Thus, his images showcase a marked juxtaposition between the application of an established binary model of sexes and the possibility of subverting it. This contrast is consistent with HIRSCHFELD's conflicting research interests: uncovering intermediate sexes, which necessitated relying on the established binary model of sexes, and advocating for sexual minorities from a humanitarian standpoint. [40]

In my analysis, I then selected images that depicted sexual intermediaries beyond the uran type. I was particularly interested in comparing and contrasting the visual representation of homosexuality with transvestism4). To achieve this, I utilized HIRSCHFELD and TILKE's photo book Die Transvestiten [The Transvestites] (1912), which accompanied HIRSCHFELD's monograph of the same name from 1910. Besides introducing the concept of transvestism to a wider scientific public, HIRSCHFELD intended to function as a spokesman for transvestite people facilitating their identity and community building (HERRN, 2005, p.70). Consequently, the intended viewership of the images in the photo book included both the scientific community, particularly sexologists, as well as the transvestite community. The photo book contained a wide range of images sent to HIRSCHFELD by transvestite individuals, as well as photos he had taken of his own patients. This allowed for a thorough comparison, including a comparison between HIRSCHFELD's own photographs and those submitted by transvestites. [41]

For maximal contrasting, one image depicting a transvestite individual was selected for analysis (Figure 2). This image was submitted by a transvestite individual herself. Due to space restrictions, respective memos are not included in full detail in this paper. However, important points are summarized.

Figure 2: Self-depiction of a transvestite person (HIRSCHFELD & TILKE, 1912, Table XVII) [42]

Figure 2 depicts a transvestite person from Austria who, without the accompanying captions, could easily be mistaken for a cisgender woman due to the feminine pose, elegant attire, and fashion photography styling. The lighting used in the image further accentuates the subject's femininity, particularly drawing attention to the gentle facial features. For minimal contrasting, another example depicting a transvestite individual was selected for analysis (Figure 3).

Figure 3: Two self-depictions of a transvestite person (HIRSCHFELD & TILKE, 1912, Table XXXI) [43]

These two images (Figure 3) were also submitted by a transvestite individual, and only the captions reveal again that the figure portrayed is a transvestite. The expressive properties in Figure 3 resemble those of Figure 2, insofar as here, too, nothing in this photo would raise doubts about the female gender of the depicted person. The lighting accentuates the figure's curvaceous silhouette. The outer appearance as a social and cultural issue related to female gender becomes the convincing place of gender assignment which differentiates Figures 2 and 3 from Figure 1's focus on "visible materiality" (PETERS, 2010, p.168). A visual style of confident self-depiction is evident in both Figures 2 and 3. [44]

In contrast to this visual style of confident self-depiction, HIRSCHFELD, in his photo book, also featured a series of images that he personally selected and arranged (Figures 4 and 5).

Figure 4: John O. (HIRSCHFELD & TILKE, 1912, Table XXII) [45]

Again, I consolidated the information from the locating memo and big picture memo into a single memo, and it contained the following information in regard to Figure 4:

"In the photo book, a man named John O. from San Francisco was presented as the American transvestite (mentioned in table XXII) through a series of four images [Figure 4]. These images correspond to a written section about John O. in Hirschfeld's 1910 book, and they depict the transvestite person both nude and clothed in two photographs each. I'm guessing all of the photographs were produced by Hirschfeld, even though the first image might be a private photo of John O. The intended viewership of the image series includes both the scientific community, particularly sexologists, as well as the transvestite community. All in all, the images seem to showcase the process of transition from male to female, with the two shots of the naked body serving as intermediate stages" (Memo, May 23, 2017). [46]

The specification memo on Figure 4 is shortened in this paper:

"The initial photo of John O. in work clothes captures him in a casual moment and differs from the clinical style of the other three photos, where he is placed in front of sterile black or white screens. While in the other three pictures John O. takes premeditated gestures, in the first image he poses more naturally. The first and last images, again, frame the intermediate stages [...], with the naked body photos representing the constructional character of the body and its visual transformation from male to female. [...] In the first nude photo, maleness is emphasized by the striking front and side lighting, which highlights the genitals, flat chest, and muscled areas around the arms and legs. In contrast, the second nude photo emphasizes femaleness through side lighting, a white background, and a softer, less accentuated naked body. John O. also hides his genitals by pressing his legs, hinting at female curves rather than male muscularity" (Memo, May 23, 2017). [47]

In the interpretation group, we concluded that HIRSCHFELD's intention to document the sexual intermediary becomes apparent when the plate in Figure 4 is "read" from left to right. Again, HIRSCHFELD relied on a bipolar regime and placed the intermediate stages between the two endpoints. By following the transition from a clothed man in daily working life to nakedness and then to redressing in female attire, observers are able to understand the sexual intermediary. However, even though the two nude photos may appear to refer to "visible materiality" (PETERS, 2010, p.168), they did not function as a visualization of the anatomical hermaphroditism identified in Figure 1. The naked body does not reveal ambiguous sex characteristics but rather is a contested surface. The photos depicting the naked body do not "direct" observers to identify bodily sex characteristics, but instead highlight the possibilities of clothing and its relation to gender expression. So, the observer is able to identify the naked body as a surface without meaning. The sexual intermediary is only understood when the observer visually follows the practices of dressing and redressing and ascribes gendered meaning to them. [48]

Furthermore, we also took into consideration the social properties of the images in Figure 4. We observed that the visual representations of maleness and femaleness were presented as equal opposites. However, we recognized that this equivalence was not experienced by transvestite individuals in reality. HIRSCHFELD (1910, p.160) himself acknowledged this fact, noting that transvestite individuals who dressed according to their assigned sex felt constrained and subdued, while experiencing a sense of calmness and euphoria when dressed in their "preferred" gender. Although the portraits in Figures 2 and 3 conveyed a sense of well-being and euphoria, the plates curated by HIRSCHFELD lacked the visual expression of feelings of familiarity or unfamiliarity (as seen in Figure 4). Therefore, the images in Figure 4 conveyed meaning that diverged from HIRSCHFELD's written statements, whereas the images in Figures 2 and 3 mirrored his textual reasoning. [49]

Figure 5 presents a minimal contrast to Figure 4, where a double image was chosen and arranged by HIRSCHFELD. The subsequent analysis outlines the key points that were discussed in the interpretation group after completing memo-writing.

Figure 5: Joseph MEIßAUER (HIRSCHFELD & TILKE, 1912, Table XVIII) [50]

The double image in Figure 5 features Joseph MEIßAUER, a transvestite person, wearing male attire in the first image and female attire in the second image. Unlike the series of images featuring John O. in Figure 4, the double image in Figure 5 does not emphasize the body as a surface devoid of meaning, nor does it focus on the materiality of a sexed body. Instead, clothing, or the "second skin" (SYKORA, 2004), serves as the crucial marker of gender (male and female) in the images. At first glance, by the similarities between the two images, male and female genders are placed in equal position side by side. In both images, Joseph MEIßAUER takes a side step and looks directly into the camera with a somewhat tense expression, while the image section and lighting remain consistent. Similar to Figures 2 and 3, in the double image in Figure 5, it is suggested that clothing is the convincing marker of gender. However, unlike the confident self-depictions in Figures 2 and 3, the double image prompts continuous comparison between the two images, presenting a binary view of gender and suspending the possibility of identifying an intermediary or in-between position. With the images, HIRSCHFELD borrowed from the visual rhetoric of criminal photography and presented Joseph MEIßAUER as an object of examination and scrutiny, rather than a self-confident and autonomous subject. As a result, the status of transvestism is called into question and it is impossible to represent it as a substantial sex category based on these images alone. [51]

To fully understand HIRSCHFELD's visual politics in relation to transvestism, it is important to acknowledge the historical context in which he was working. During that time, the binary view of sexes was the dominant paradigm in medicine, and it was believed that biological sex was the determining factor in shaping one's gender identity. Therefore, it is not surprising that HIRSCHFELD conveyed a binary model of sexes, as seen in his series of images (Figures 4 and 5). However, it is important to note that HIRSCHFELD's visual politics are highly ambivalent when it comes to the sexual intermediary of transvestism. On the one hand, the single photographs (Figures 2 and 3) document authentic self-depictions of transvestite people, and HIRSCHFELD provided a valuable insight into their lives and experiences. On the other hand, HIRSCHFELD seemed to reinforce a binary model of sexes by the aesthetic structures in his series of images (Figures 4 and 5), which he originally intended to shy away from. [52]

Despite this ambivalence, it is also worth considering that by referencing the dominant medical paradigm of his time, HIRSCHFELD's images could be easily adapted in medical disciplines. This may have helped to further the understanding of transvestism and gender identity among medical professionals, even if his approach may seem outdated or problematic from a contemporary perspective. Overall, it is important to view HIRSCHFELD's visual politics in a nuanced way, acknowledging both the limitations and potential of his work. [53]

3.4 Contextualizing results in language-based discourse

To fully comprehend the importance of the visual level of discourse on transness, it is crucial to establish a connection between the visual level and language-based level in HIRSCHFELD's work, as well as the broader language-based level of the early 20th century. To facilitate a better understanding, the findings from the visual discourse level have been distilled into a category system presented in Figure 6.

Figure 6: Category system—visuality of transness in HIRSCHFELD's work. Please click here for an enlarged version of Figure 6. [54]

Through analyzing HIRSCHFELD's visual depictions of intermediate sex categories, I discovered subtle and nuanced meanings that were conveyed through his imagery. The depiction of homosexuality (Figure 1) as an intermediate sex category was based on a combination of male and female ideals and emphasized the physicality of the (hermaphroditic) body, suggesting a spectrum of sexes. This portrayal of a spectrum aligned with Hirschfeld's written work, in which he advocated for a range of sexes and sought to normalize homosexuality as a substantial sex category situated between male and female. However, the images also diverged from his written work, as bodily characteristics served as markers of the intermediate sex category, while in his texts, HIRSCHFELD focused on mental characteristics and sex drive. [55]

Transvestism was depicted by HIRSCHFELD as an intermediate sex category in two distinct ways. Firstly, in some images, transvestism was normalized as a substantial sex category without reference to a bipolar spectrum of sexes (Figures 2 and 3). Here, transvestite femaleness was identical to cisgender femaleness, and the images mirrored HIRSCHFELD's textual statements about the feelings of euphoria and calmness experienced by transvestite individuals. Secondly, other images, particularly those of his patients, portrayed transvestism as a result of changing clothing (Figures 4 and 5), which diverged from HIRSCHFELD's written work. With these images, HIRSCHFELD suggested a bipolar and dichotomous regime of sexes, rather than a spectrum of sexes. [56]

In his written work, HIRSCHFELD extensively discussed the existence of intermediary sexes across various levels such as gonads, genitals, secondary sex characteristics, sex drive, and personality, highlighting the potential for intermediation between them. However, his use of images mainly centered on bodily features and clothing, thereby restricting possibilities for acknowledging diversity. This approach represents a discursive reduction, which narrows the comprehension and recognition of the multifaceted nature of transness. [57]

The next step in the analysis is to link the ways of interpreting the images to the language-based discourse on transness during the first half of the 20th century. However, due to the limited scope of this paper, I will only briefly evaluate this connection. HIRSCHFELD's photo book received widespread attention upon its publication, particularly among transvestite individuals who identified as a different sex than their biological characteristics would suggest, and who sought surgical interventions. These individuals, whom HIRSCHFELD (1923) referred to as "transsexual" people, emerged as a result of research on transvestism. So, despite the varying interpretations of the images in his publication, with his photo book, HIRSCHFELD helped in fostering identity and community building among this group. Although the implications of his work on the larger discourse on transness require further investigation, it is clear that HIRSCHFELD's contributions had a significant impact on the lives of "transsexual" individuals during that time. [58]

Even before 1923, doctors had treated "transsexual" people by performing experimental surgeries. However, these innovative treatments had not targeted a "sex change" in favor of those patients, but they had constituted alternative solutions for untreatable mental conflicts (HIRSCHAUER, 2015 [1993], p.98). Doctors had classified these patients as untreatable when they had not easily been swerved from their resolve or when they had held on to their self-definition as the "opposite" sex. Doctors from the emerging field of endocrinology also played a key role in these first attempts to alter the sexed body. In the 1920s, it was possible for the first time to extract hormones from the testicles, and ovaries respectively. While sex hormones were initially assumed to cause typical male/female developments in the human body, biologists then pointed to the fact that both "male" and "female" sex hormones were prevalent in each body (VOSS, 2010, p.208). The initial notion of the binary sexed body, which was identifiable in HIRSCHFELD's imagery, thus led not only to the idea of a continuum of sexes but to the model of alterable sexes. This emergence of an endocrinological paradigm affected the medical understanding of gender and gender identity. Gender identity was not thought of in terms of a binary sexed morphology anymore, but it was understood within the framework of modifiable sex and gender (STAMMBERGER, 2017, p.89). So, at the level of language-based discourse, the focus on the materiality of the sexed body was intertwined with the concept of producible sex and gender, and this coincided with the emergence of the idea of a continuum of sexes. [59]

HIRSCHFELD's images were deeply embedded in these discursive developments, reflecting the notion of a bipolar model of sexes through the idea of a spectrum. The images in Figures 4 and 5 also highlighted the prevailing idea of sex/gender modification in HIRSCHFELD's image use. While in his written work, he acknowledged the diversification of sex categories by recognizing different levels of sexual intermediaries, his image use limited discursive possibilities. This suggests that visuality gained greater prominence over text. However, further historical research on the direct reception of HIRSCHFELD's images in medical and subcultural discourse at that time is necessary to corroborate this conclusion. [60]

With this paper, I aimed to make a two-fold contribution to the field of visual sociology. Firstly, I critically examined some of the most prominent methods for analyzing and interpreting images as research objects, drawing on DA and GTM. My evaluation criteria were based on the ability of these methods to capture both the expressive and social properties of images, as images possess both aesthetic structures and communicative functions within complex systems of knowledge production. Secondly, I conducted a visual analysis of historical images on early forms of transness in the work of HIRSCHFELD, applying research strategies derived from CLARKE (2005) and DA. I sought to investigate whether images could influence discursive developments. By combining these two aims, my contribution offers a nuanced understanding of the complex relationship between images and discursive practices, as well as the potential for images to shape and transform social knowledge production in ways that extend beyond the linguistic domain. [61]

The methodological programs proposed by CLARKE (2005) and MEY and DIETRICH (2016) have been demonstrated to be effective in analyzing and interpreting images in terms of their expressive and social properties. In particular, CLARKE's (2005) method, in which she emphasized the importance of memo-writing in the analysis process, proved to be highly applicable in this study on HIRSCHFELD's image use. By offering a concrete example of the suitability of CLARKE's (2005) method in the field of visual sociology, I contributed to the broader discourse on visual analysis methods. Furthermore, by the study's success, I suggest that CLARKE's approach to visual analysis, which is currently underutilized, could be applied in other research areas in visual sociology. In future studies, researchers should therefore continue to explore the potential of this method in a range of research questions and contexts. [62]

In the analysis of HIRSCHFELD's image use, I demonstrated the various meanings conveyed in his imagery regarding early forms of transness. I showed that while HIRSCHFELD diversified sex categories in his written work, his images focused on the sexuated body and behavioral elements, such as clothing, to justify transness. This narrowed the potential meanings of sexual intermediaries and reduced their diversity. Despite this restriction, I found that his images had a strong impact on the lives of transvestite/transsexual individuals at that time, indicating the importance of "becoming visible" in discourse for sexual minorities to gain social acceptance. Furthermore, I suggested that HIRSCHFELD's image use might have influenced discursive developments in sexology because the meanings conveyed in his images coincided with a new understanding of transness in medicine. [63]

I highlighted the importance of exploring the interplay between HIRSCHFELD's images and discursive developments, including how medical professionals and transvestite individuals directly responded to these images. This underscores the crucial role of visual analysis in social research and the need for researchers to consider the relationship between the potential meanings conveyed in images, their receptions, and the discourse structure. Therefore, developing methodological programs that incorporate these elements is a crucial objective in advancing the field of visual sociology. [64]

1) All translations from German texts are mine. <back>

2) In 1899, HIRSCHFELD mentioned intermediary sexes for the first time relating them solely to homosexuality. His scientific preoccupation with deviant sexes functioned as a means to legitimize homosexual behavior as a natural occurrence. His concept of a third sex addressing homosexuality can be traced back to German author and lawyer Karl Heinrich ULRICHS (1994 [1864-1879]) who published a number of pamphlets about Uranismus [uranism] in the 19th century. ULRICHS aimed at decriminalizing homosexuality by proposing that homosexual men possessed a female soul in a male body, arguing for the validity of this "sexually-inverted soul" (RUNTE, 1996, p.83). HIRSCHFELD took on ULRICHS' notion of a natural division between body and soul and developed it further by identifying sexual differences not just on two (body and soul) but on five distinct levels: gonads, genitals, secondary sex characteristics, mental state and sexual drive. HIRSCHFELD discovered a rich number of sexual intermediaries on each level, leading to a total of about eight-digit sexual variations, including hermaphroditism, homosexuality, androgyny and transvestism. Considering each variation as a substantial sex category (HIRSCHAUER, 2015 [1993], p.84), HIRSCHFELD struck a new path in sexology, marking intermediary sexes as innate, biological variations rather than as gonadal effects. His humanistic doctrine aiming at a "gendered conception of individuality" (HIRSCHAUER, 2015 [1993], p.84) must be considered emancipatory at that time because it avoided pathologizing sexual variations. His doctrine also avoided treating sexual variations as psychiatric issues as was the case in sexology at the beginning of the 20thcentury following theories of degeneration. <back>

3) For permission to reprint the following photos I want to thank the Magnus-Hirschfeld-Gesellschaft e.V. <back>

4) Coining the term "transvestism," HIRSCHFELD (1910, p.159) found a description for people who felt the urge to dress in clothes of a sex they were not assigned to judging from their bodily characteristics. In contrast to former sexologists such as ULRICHS (1994 [1864-1879]), WESTPHAL (1869) or KRAFFT-EBING (1886), HIRSCHFELD differentiated transvestism from homosexuality, and introduced it as a substantial sex category. This distinction was brought about mainly by transvestite and homosexual people HIRSCHFELD was in close contact with at that time. In contrast to established doctors, HIRSCHFELD characterized transvestism not so much as a psychiatric issue which was believed to manifest on a behavioral level (dressing in clothes of the opposite sex), but as an "expression of the personality"and as a "manifestation of being" (ibid.). He was the first sexologist to refer to the social identity and the way of life of transvestite people. <back>

Barthes, Roland (1973 [1957]). Mythologies. London: Paladin Books.

Betscher, Silke (2013). Bildmuster – Wissensmuster. Ansätze einer korpusbasierten Visuellen Diskursanalyse. Zeitschrift für Semiotik, 35, 285-319.

Bleiker, Roland (2015). Pluralist methods for visual global politics. Millenium: Journal of International Studies, 43(3), 872-890.

Boehm, Gottfried (2008). Wie Bilder Sinn erzeugen. Die Macht des Zeigens. Berlin: Berlin University Press.

Bohnsack, Ralf (2008). The interpretation of pictures and the documentary method. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung / Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 9(3), Art. 26, https://doi.org/10.17169/fqs-9.3.1171 [Accessed: October 5, 2022].

Breckner, Roswitha (2010). Sozialtheorie des Bildes. Zur interpretativen Analyse von Bildern und Fotografien. Bielefeld: transcript.

Charmaz, Kathy (2006). Constructing grounded theory. A practical guide through qualitative analysis. London: Sage.

Christmann, Gabriela B. (2008). The power of photographs of buildings in the Dresden urban discourse. Towards a visual discourse analysis. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung / Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 9(3), Art. 11, https://doi.org/10.17169/fqs-9.3.1163 [Accessed: October 5, 2022].

Clarke, Adele (2005). Situational analysis. Grounded theory after the postmodern turn. London: Sage.

Clarke, Adele (2012). Situationsanalyse. Grounded Theory nach dem Postmodern Turn. Wiesbaden: Springer VS.

Eriksson, Päivi & Kovalainen, Anne (2008). Qualitative methods in business research. London: Sage.

Fairclough, Norman (1995). Media discourse. London: Arnold.

Forceville, Charles (1999). Educating the eye?: Kress and van Leeuwen's Reading Images: The Grammar of Visual Design (1996). Language and Literature, 8(2), 163-178.

Foucault, Michel (1989 [1961]). Wahnsinn und Gesellschaft. Eine Geschichte des Wahnsinns im Zeitalter der Vernunft. Frankfurt/M.: Suhrkamp.

Foucault, Michel (1990 [1966]). Die Ordnung der Dinge. Eine Archäologie der Humanwissenschaften. Frankfurt/M.: Suhrkamp.

Gadamer, Hans-Georg (1986 [1959]). Vom Zirkel des Verstehens. In Hans-Georg Gadamer, Gesammelte Werke: Wahrheit und Methode (pp.57-65). Tübingen: Mohr.

Glaser, Barney G. (1978). Theoretical sensitivity. Advances in the methodology of grounded theory. Mill Valley, CA: Sociology Press.

Glaser, Barney G. (1998). Doing grounded theory. Issues and discussions. Mill Valley, CA: Sociology Press.

Glaser, Barney G. & Strauss, Anselm L. (1967). The discovery of grounded theory. Strategies for qualitative research. New York, NY: Aldine.

Halberstam, J. Jack (1998). Female masculinity. Durham: Duke University Press.

Halliday, Michael Alexander Kirkwood (1978). Language as social semiotic: The social interpretation of language and meaning. London: Edward Arnold.

Hart, Christopher (2016). The visual basis of linguistic meaning and its implications for critical discourse studies. Discourse & Society, 27(3), 335-350.

Herrn, Rainer (2005). Schnittmuster des Geschlechts. Transvestismus und Transsexualität in der frühen Sexualwissenschaft. Gießen: Psychosozial Verlag.

Hirschauer, Stefan (2015 [1993]). Die soziale Konstruktion der Transsexualität. Frankfurt/M.: Suhrkamp.

Hirschfeld, Magnus (1899). Die objektive Diagnose der Homosexualität. Jahrbuch für sexuelle Zwischenstufen unter besonderer Berücksichtigung der Homosexualität, 1, 1-35.

Hirschfeld, Magnus (1903). Ursachen und Wesen des Uranismus. Jahrbuch für sexuelle Zwischenstufen unter besonderer Berücksichtigung der Homosexualität, 5, 1-193.

Hirschfeld, Magnus (1910). Die Transvestiten. Eine Untersuchung über den erotischen Verkleidungstrieb. Berlin: Pulvermacher.

Hirschfeld, Magnus (1923). Die intersexuelle Konstitution. In Wolfgang Schmidt & Magnus Hirschfeld (Eds.), Jahrbuch für sexuelle Zwischenstufen (pp.9-26). Frankfurt/M.: Qumran.

Hirschfeld, Magnus & Tilke, Max (1912). Der erotische Verkleidungstrieb (Die Transvestiten), illustrierter Teil. Berlin: Pulvermacher.

Jewitt, Carey & Oyama, Rumiko (2001). Visual meaning: A social semiotic approach. In Theo Van Leeuwen & Caret Jewitt (Eds.), The handbook of visual analysis (pp.134-156). London: Sage.

Johnstone, Barbara (2018 [2002]). Discourse analysis. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons.

Kautt, York (2017). Grounded Theory als Methodologie und Methode der Analyse visueller Kommunikation. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung / Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 18(3), Art. 8, https://doi.org/10.17169/fqs-18.3.2859 [Accessed: October 5, 2022].

Keller, Reiner (2011 [2004]). Diskursforschung. Eine Einführung für SozialwissenschaftlerInnen. Wiesbaden: VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften.

Knoblauch, Hubert (2005). Wissenssoziologie. Konstanz: UVK.

Knoblauch, Hubert; Baer, Alejandro; Laurier, Eric; Petschke, Sabine & Schnettler, Bernt (2008). Visual analysis. New developments in the interpretative analysis of video and photography. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung / Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 9(3), Art. 14, https://doi.org/10.17169/fqs-9.3.1170 [Accessed: October 5, 2022].

Konecki, Krzysztof (2011). Visual grounded theory: A methodological outline and examples from empirical work. Revija za Sociologiju, 41(2), 131-160.

Koyama, Emi (2003). The transfeminist manifesto. In Rory Cooke Dicker & Alison Piepmeier (Eds.), Catching a wave. Reclaiming feminism for the 21st century (pp.244-259). Boston, MA: Northeastern University Press.

Krafft-Ebing, Richard von (1886). Psychopathia Sexualis. Stuttgart: Enke.

Kress, Gunther & van Leeuwen, Theo (2021 [1996]). Reading images. The grammar of visual design. London: Routledge.

Lichtman, Marilyn (2002). Review: Gillian Rose (2001). Visual methodologies: An introduction to the interpretation of visual materials. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung / Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 3(4), Art. 30, https://doi.org/10.17169/fqs-3.4.798 [Accessed: October 5, 2022].

Lim, Fei Victor (2004). Developing an integrative multi-semiotic model. In O'Halloran, Kay L. (Ed.), Multimodal discourse analysis (pp.220-246). London: Continuum.

Lünenborg, Margreth & Maier, Tanja (2013). Gender media studies. Konstanz: UVK.

Maasen, Sabine; Mayerhauser, Torsten & Renggli, Cornelia (2006). Bilder als Diskurse – Bilddiskurse. Weilerswist: Velbrück Wissenschaft.

Machin, David (2013). What is multimodal critical discourse studies?. Critical Discourse Studies, 10(4), 347-355.

Malherbe, Nick; Suffla, Shahnaaz; Seedat, Mohamed & Bawa, Umed (2016). Visually negotiating hegemonic discourse through photovoice: Understanding youth representations of safety. Discourse & Society, 27(6), 589-606.

Mey, Günter & Dietrich, Marc (2016). From text to image—shaping a visual grounded theory methodology. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung / Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 17(2), Art. 2, https://doi.org/10.17169/fqs-17.2.2535 [Accessed: October 5, 2022].

Mitchell, William John Thomas (1994). Picture theory. Essays on verbal and visual representation. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

Morse, Janice M.; Noerager Stern, Phyllis; Corbin, Juliet M.; Bowers, Barbara; Charmaz, Kathy & Clarke, Adele E. (2009). Developing grounded theory. The second generation. Walnut Creek, CA: Left Coast Press.

O'Halloran, Kay L. (2004). Multimodal discourse analysis. London: Continuum.

Peez, Georg (2006). Fotoanalyse nach Verfahrensregeln der Objektiven Hermeneutik. In Winfried Marotzki & Horst Niesyto (Eds.), Bildinterpretation und Bildverstehen. Methodische Ansätze aus sozialwissenschaftlicher, kunst- und medienpädagogischer Perspektive (pp.121-141). Wiesbaden: VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften.

Peters, Kathrin (2010). Rätselbilder des Geschlechts. Körperwissen und Medialität um 1900. Zürich: Diaphanes.

Rose, Gillian (2001). Visual methodologies. An introduction to the interpretation of visual materials. Los Angeles, CA: Sage.

Runte, Annette (1996). Biographische Operationen. Diskurse der Transsexualität. München: Fink.

Saalfeld, Robin K. (2020). Transgeschlechtlichkeit und Visualität. Sichtbarkeitsordnungen in Medizin, Subkultur und Spielfilm. Bielefeld: transcript.

Schnettler, Bernt & Raab, Jürgen (2008). Interpretative visual analysis. Developments, state of the art and pending problems. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung / Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 9(3), Art. 31, https://doi.org/10.17169/fqs-9.3.1149 [Accessed: October 5, 2022].

Scholz, Sylka; Kusche, Michel; Scherber, Nicole; Scherber, Sandra & Stiller, David (2014). Das Potenzial von Filmanalysen für die (Familien-) Soziologie. Eine methodische Betrachtung anhand der Verfilmungen von "Das doppelte Lottchen". Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung / Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 15(1), Art. 15, https://doi.org/10.17169/fqs-15.1.2026 [Accessed: October 5, 2022].

Seko, Yukari (2013). Picturesque wounds: A multimodal analysis of self-injury photographs on Flickr. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung / Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 14(2), Art. 22, https://doi.org/10.17169/fqs-14.2.1935 [Accessed: October 5, 2022].

Stammberger, Birgit (2017). Körperliche Materialität. Zur Kritik des Geschlechterkonstruktivismus. In Christoph Behrens & Andrea Zittlau (Eds.), Queer-Feministische Perspektiven auf Wissen(schaft) (pp.82-121). Rostock: Universität Rostock, https://doi.org/10.18453/rosdok_id00000110 [Accessed: October 5, 2022].

Straube, Wibke (2014). Trans cinema and its exit scapes. A transfeminist reading of utopian sensibility and gender dissidence in contemporary film. Linköping: Linköping University Press, http://liu.diva-portal.org/smash/get/diva2:742465/FULLTEXT02.pdf [Accessed: October 5, 2022].

Strauss, Anselm L. (1978). A social world perspective. In Norman Denzin (Ed.), Studies in symbolic interaction (pp.119-128). Greenwich, CT: JAI Press.

Strauss, Anselm L. (1991 [1987]). Grundlagen qualitativer Sozialforschung. Weinheim: Beltz.

Strauss, Anselm L. & Corbin, Juliet M. (1998 [1990]). Basics of qualitative research: techniques and procedures for developing grounded theory. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Stryker, Susan (2017 [2008]). Transgender history. The roots of today's revolution. New York, NY: Seal Press.

Sykora, Katharina (2004). Umkleidekabinen des Geschlechts. Sexualmedizinische Fotografie im frühen 20. Jahrhundert. Fotogeschichte. Beiträge zur Geschichte und Ästhetik der Fotografie, 24, 15-30.

Traue, Boris; Blanc, Mathias & Cambre, Carolina (2019). Visibilities and visual discourses: Rethinking the social with the image. Qualitative Inquiry, 25(4), 327-337.

Ulrichs, Karl-Heinrich (1994 [1864-1879]). Forschungen über das Räthsel der mannmännlichen Liebe. Berlin: Verlag rosa Winkel.

Van Leeuwen, Theo (1991). Conjunctive structure in documentary film and television. Continuum: The Australian Journal of Media & Culture, 5(1), 76-114.

Vetter, Brigitte (2010). Transidentität – ein unordentliches Phänomen. Bern: Hans Huber Hogrefe.

Voss, Heinz-Jürgen (2010). Making sex revisited. Dekonstruktion des Geschlechts aus biologisch-medizinischer Perspektive. Bielefeld: transcript.

Wekesa, Nyongesa Ben (2012). Cartoons can talk? Visual analysis of cartoons on the 2007/2008 post-election violence in Kenya: A visual argumentation approach. Discourse and Communication, 6(2), 223-238.

Westphal, Carl (1869). Die conträre Sexualempfindung. Symptom eines neuropathischen (psychopathischen) Zustands. Archiv für Psychiatrie und Nervenkrankheiten, 2, 73-108.

Robin K. SAALFELD is a postdoctoral researcher at the Friedrich-Schiller-University Jena. His main research areas are trans and queer studies, visual sociology, social inequalities, mixed methods and qualitative research. Currently, he is part of a research project about property inequality in the private's sphere in the Collaborative Research Center 294: Structural Change of Property.

Contact:

Dr. Robin K. Saalfeld

Friedrich-Schiller-Universität Jena

Institut für Soziologie, SFB 294: Strukturwandel des Eigentums

Carl-Zeiss-Straße 3, 07743 Jena, Germany

Tel.: 0049-(0)3641-945837

E-Mail: robin.saalfeld@uni-jena.de

URL: https://sfb294-eigentum.de/de/beteiligte/robin-k-saalfeld/

Saalfeld, Robin K. (2023). Transgressing the linguistic domain: The transformative power of images in Magnus Hirschfeld's sexological work [64 paragraphs]. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung / Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 24(2), Art. 13, https://dx.doi.org/10.17169/fqs-24.2.3975.