Volume 9, No. 2, Art. 40 – May 2008

A Sketchbook of Memories

Karen V. Lee

Abstract: The following arts-based autoethnography (BARONE, 2003; SLATTERY, 2001) reveals the author's emotional upheaval when her daughter leaves for a one-week camping trip with her father. The experience causes an ethnographic shift inward and outward on the personal and social aspects shaping her loss. She reflects on how she lives simultaneously in a culture of independence and a culture of dependence. Multiple layers of consciousness cause her to revisit her daughter's sketching albums. In doing so, she finds enormous peace and comfort by reflecting on the drawings. In the end, she creates both a picture book of memories and a movie that becomes a manifestation of performative social science in order to "look towards means of (re)presentation that embrace the humanness of social science pursuits" (JONES, 2006, p.67). By creating the art-based autoethnography, she is able to cope with missing her daughter as she resonates with memorable insights and triumphs. Overall, the author discovers how creating both the sketchbook and movie heightens the transformative nature of autoethnographic research.

Key words: arts-based autoethnography, performative social science

Table of Contents

1. Prologue

2. Sketchbook

3. Epilogue

The following sketchbook shows how I am conflicted by dependence and independence from missing my daughter. I arrive at a crisis and choose to write autoethnographically to gain a deeper understanding about my upheaval. From writing, I provide a pedagogical context that shows how knowing the self and subjects are integrated. I wish to "showcase concrete action, dialogue, emotion, embodiment, spirituality, self-consciousness" (ELLIS, 2004, p.38) and "draw on personal experience with the explicit intention of exploring methodological and ethical issues as encountered in the research process" (SPARKES, 2002, p.59). I "look toward means of (re)presentation that embrace the humanness of social science pursuits" (JONES, 2006, p.67). [1]

There are ethical and pedagogical issues: audience, authority, exposure, ownership, personal vulnerability. There are feelings: anger, anxiety, fear, guilt, shame, discomfort, embarrassment. There is a sense of uncertainty about the performative process as I re-examine my epistemological position. I use autoethnography as a form of writing that blends social science with the aesthetic sensibility from expressive forms of art. I seek to "tell stories that show bodily, cognitive, emotional, and spiritual experience" (ELLIS, 2004, p.30). I reflect on my experience as a mother experiencing social, cultural, personal, emotional, and intellectual turmoil. [2]

The purpose of this article is for readers to gain a deeper understanding about how autoethnographical writing is a form performative social science. By writing, "the chances for understanding a way of life are enhanced" (SPARKES, 2002, p.74) as "the confessional becomes a self-reflective meditation on the nature of ethnographic understanding; the reader comes away with a deeper sense of the problems posed" (VAN MANNEN, 1988, p.92). By constructing the autoethnography, I reflect upon my ethnographic practice and raise discussion about the complex issues associated with performative social science. I use "systematic sociological introspections and emotional recall to try to understand the experiences" (ELLIS, 1997, 1999). I tell a "personal tale of what went on backstage during a research project" (ELLIS, 2004, p.50). My research is situated within a personal and contextual framework and uses a social constructionist perspective. As I share my emotions, I write, "therapeutically, vulnerably, evocatively, and ethically" (ELLIS, 2004, p.2). Through autoethnography, I ask "readers to relive the experience through the writer's or performer's eyes" (DENZIN, 2001, p.905). [3]

This morning, a deep nausea

A strange smile

I wave in silence

This morning, a deep nausea

A desperate embrace

I battle darkness

This morning, a deep nausea

A floodwater of tears

I wash the street

Sunlight upon her hair, I smile. My ten-year old daughter is in my arms. A warm breeze slips beneath my hair. Tears well up, a blast of wind scorches my cheeks. She goes camping for a week with her father. Paraphernalia: flashlights, lanterns, the bulk of food, sleeping bags to magnify the occasion. I've had my holiday with her; it is his turn. My racing heart beats against her body. The world comes and goes in this moment with my future in her hands. [4]

I stroke her hair and kiss her forehead. Give her a long hug. A shiver runs down my spine. I will walk away at right angles to my body, change position, twist and move abruptly to break the moment.

"Bye, Mom."

"Bye, honey, have a good time." [5]

The words cover my heart. A flood of breath presses the valves, the muscles. I wave, she waves back. I smile, she smiles back. I drift away, have an out-of-body experience and ask, Is this a dream? [6]

Silently, I watch her in blue shorts, pink T-shirt, purple sport sandals, blue hat, no socks. I lower my eyes to the profound goodbye. A discreet, desperate gesture, I wave again. As I catch my breath, an oppressive melancholy invades. A heavy weight presses on my heart. An unfamiliar gloom gathers. My sentence begins as the camping trip portends a long week. A lump of clay in my hands; what choice do I have? [7]

As the car drives away, I scan the room. Silence exacerbates my sense of solitude. The south-facing windows are yellow with sunlight. On the piano, her Santa photos, Mother's Day card, and class photos. A too-careful script of childhood development. It's just an ordinary day but I confess out loud, "I miss you already." [8]

Slowly, I make my way to her bedroom. In the corner, there is a black beanbag chair. Reluctantly, I sit in it. Everything is quiet and white. A chest of drawers with neatly written labels: shirts, socks, pants, underwear. There is bookshelf of her possessions. On her desk, there is a photo of her holding her stuffed bear. She has shoulder-length black hair and brown eyes. Not light brown but deep brown. She has pale, thick red lips. She likes to wear huge T-shirts that are too big for her body; she is small and thin. Her teeth are straight with many cavities. I recall waiting for her cavity operation. At three years old, she was anaesthetized to fill all the cavities at once. [9]

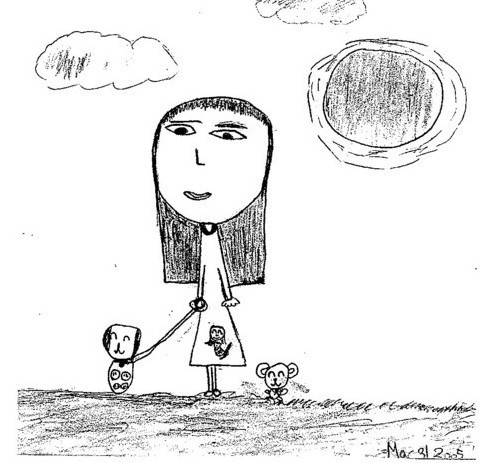

I make my way around her room and imagine her watching me. Then, I have a sudden inspiration to view her sketchbooks. Stacked in order, we bought them all at once. On some nights, she sketches for hours. The afternoon I bought her a Staedtler Series of Mars Lumograph pencils, HB, 2B, 4B, 6B, 7B, 8B, she was set for life. I take a sketchbook and open it. "This is my title page," she had explained. "Me, a dog, and Boo-boo."

Figure 1: Me, dog, Boo-boo [10]

Boo-boo, her stuffed bear, has traveled to Seattle, Disneyland, West Edmonton Mall, Harrison Hot Springs and camping sites. Boo-boo is hidden in a suitcase but easy to care for. She is a stuffed-animal aficionado. Initially, I had serious doubts about being a devoted mother. I smile and recall adopting her. At three-and-a-half months, she had tiny feet and lots of black hair. Not used to me, she cried all the way home. Eventually, she fell asleep while shaking. Allergic to milk, she drank soymilk. She only had the clothes on her back, a bottle of soymilk, a car seat, and one white crochet hat. She was a small, fragile little baby that needed my love. For ten years, she has brought pure happiness. [11]

I sigh. Take a deep breath. Yesterday, I made meatloaf. She loves to smother it with ketchup. Eating slowly, she savors each bite until it dissolves. The traditional meatloaf my mother used to make. The leftover meatloaf makes a sacred farewell. She also likes chicken, chocolate, noodles, meatloaf, pork chops, roast beef, mushroom burgers, iced tea, moussaka, potato chips, and ice cream.

|

|

"This is Ariel," she told me. Stretching out on the floor, I stare at the next drawing about fairies. She loves fairies, movies about mermaids, and stuffed unicorns. Once, I searched many stores as Ariel was the Christmas gift she really wanted. But Ariel was sold out in most stores. Only a mother buying Santa presents knows how paralyzing "sold-out" can be. Finally, I found Ariel and put it in my car. Exuberantly, she opened the present and said, "Yes! Ariel!" |

I flip the page. "This is a girl at the park with her dog," she had said softly. "His name is Squishy from the Pet Den on Broadway Street." A purely imaginative scene as she does not own a real dog. The letter "A" on the girl's hat is obviously for her name, Amber, which was carefully chosen from numerous baby name books. Who knew, "she would be mothered by an educational idealist" (LEE, 2006a, p.150)?

Figure 3: Squishy [13]

This sketch reveals her beauty: sweet mouth, white hands, a thin, comical nose, and large, deep brown eyes. Able to see everything: fierce, weird, thoughtful. She presents a rosy, smooth-haired appearance, but she does not say much in large groups. She smiles easily and often, a naturally happy child. A regular maiden, she carries herself like a young lady with manners but usually, with no socks on. The sight of her, barefoot, makes me laugh. Lately, she has been affecting her new teenage walk. Thoroughly biased, she is adorable. I run my fingers over the dog. She still speaks of this hypothetical dog. I imagine our hands squeezing together as we stroll the dog and train it to fetch. How on earth am I supposed to be a parent without having a dog? [14]

Closing my eyes, I flip the page. "This is a ballerina performing for the Queen," she explains. "She is Chinese, twenty-five years old and dances to the Nutcracker Suite."

Twirling feet

Dancing

Palms spread high

Enchanted brown eyes

Figure 4: Ballerina [15]

|

"Bunnies, bunnies," she says. Closing my eyes, I recall the sun on her face at the rabbit farm. "Can I take one home?" "Why do they live in holes?" "Do they only eat carrots?" she asks. Frantically, she chases rabbits back and forth. So much history in one syllable as she points to her favorite rabbit. For the first time, I understand the relentless need for rabbits in a little girl's life. A necessary ingredient for her education. Hunching, she waved goodbye while begging to take one home. |

|

|

|

|

|

"This is a weird-headed girl, Mom," her voice lowers. "I don't like this drawing." As a critic of food, books, friends, people, movies, it annoys her that weird classmates have off-the-wall behaviors. The idiosyncrasies of their smiles, poses, crying, nicknames, baby talk, and whining. The one characteristic she cannot tolerate: whining. |

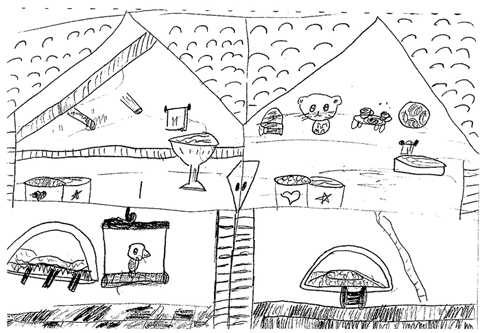

I miss her lively voice, clapping hands, whoops of delight. A dim past stirs again. The floor sways as I reflect. The sun goes behind the blinds. Dizzily, I want to hear her whine about whiners. As I flip to the next page, there is "a sketch of a hamster and bird house," she chuckled. "They try to be friends. See, they have baths, towels, food, dishes."

Figure 7: Hamster and bird house [17]

Her pet memories: two hamsters and two budgies. Chewy, a lovely hamster that would leap gracefully until he died of old age. No fuss, no sound. But she bonded with the next hamster—C.C., Cookie Crumb. I recall giving her Joey, a blue budgie. A tiny break in a daily routine. And we survived his sad conclusion. When the screen door opened, Joey flew out. Gone. No time to say goodbye. A sudden weakness as I explained it proved unwise to have an uncaged flying bird. [18]

"Poor Joe," she said. Stroking her hair, I echoed, "Poor Joe." Condolences, the "It's-okay," the "You'll-get-another-bird" follow-up. I held out my hand and she took it. Glowingly, she carried a new budgie home, ready to tame it. [19]

I calculate the math: one week, seven days, one hundred and sixty-eight hours. Blood drains from my face while a tidal wave gushes from my eyes. Flipping the page, I recall the sign. Beware: Sandhill Crane aggressive. Caution. We frolicked through the Reifel Migratory Bird sanctuary. It was June and the best month to see ducklings and goslings. It was a windy but sunny as she put her arms inside her vest. Armless, she skipped and threw birdseed. As a flock of birds surrounded us, she covered her head to avoid droppings. Suddenly, the Sandhill crane returned. Unprepared, I ran and she ran. Took it on the lam from the crane. We both fled from Big Bird.

Figure 8: Bird sanctuary [20]

"Summer Forever, the dog is happy," she had said. There is a blur of tears as I return to summer rituals. Inside my chest, there is a deep hole. Blinking, I stare at the dog. I read a book while she dug a hole. We ate noodles and played cards. There were dogs searching for scraps of food: dog chow.

Figure 9: Dog chow [21]

She grabbed my hand and dragged me to the ocean waves. I resisted and there was a tug-of-war. "Let's get your feet wet," she insisted. I inched forward; she laughed. With her hands on my back, she edged me forward. I listed reasons for not wetting my feet. But I prepared for cold water. Instantly, she let go. No pleading or whimpering. I trusted her completely. At that instant, I knew she had a compassionate soul. [22]

We talk and talk, usually over food. We chat about pets, books, food, dreams, games, ideas, funny people. Girl-to-girl. She loves funny stories, over and over, we discuss the same stories. About me, students, family, friends, grandparents. And our many projects: latch hook pillows, jigsaw puzzles. Lately, she loves silent reading. Minutes fall like leaves from a tree. The "d-e-a-r" acronym "drop everything and read." I crank up for silent reading. But sometimes, I lack fuel for the marathon and asleep on the couch. As I enter a peaceful world, I play the harmonica and wish we were silent reading. [23]

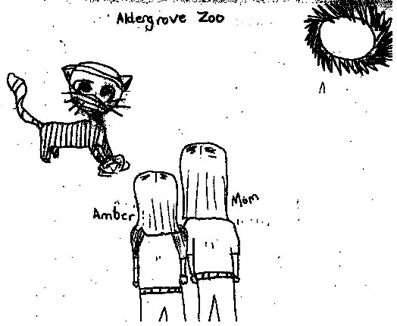

Quickly, I turn my head. There is a furtive shadow near the window. I must keep still, wait longer for my veins to warm. Turning the page, I shake my head. Committed to memory, it was a glorious day at the zoo. Our usual preparation: hats, snacks, suntan lotion, a camera, water bottles. Her eyes sparkled when spotting the tiger. For a brief moment, I swivel and bring the day back.

Figure 10: Aldergrove zoo [24]

"Let's go watch them feed the lions," she exclaims while running toward their den. Lions and tigers eat chunks of raw meat! With each throw, I gasp. The zoo keeper was feeding the large ferocious cats. No one watching but us. My memory records a fine collection of zoo animals: addax, African lions, spurred tortoise, Arctic wolf, Bactrian camel, bison, Burmese python, flamingos, Chilean fire tarantula, Eurasian lynx, and a black bear. Oh, how she loved the black bear. Named Boo-boo, like her stuffed bear. And the giraffes. And the hippopotamus in his new hippo haven. Did he show up? [25]

As she clasps my hand, I freeze the moment. How she rants about the great theft of Herbie, a rare Marginated Tortoise. There were signs everywhere.

Herbie is a rare Marginated Tortoise and

needs special care and attention to survive.

"But why would someone steal Herbie, Mom?"

"They believe someone wanted him as a pet," I say.

"I bet he misses his Mommy," she commented. [26]

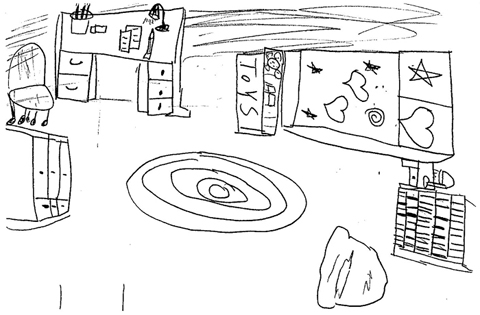

The next page in her sketchbook shows her dream bedroom. Her familiar ramble of soft vowels makes me believe in the strength of my thoughts. How she creates her passport to a different dream. Hieroglyphics. Her sketching fingers have detailed meager shadows with fantasies. She wants to read many books this year.

Figure 11: Dream bedroom [27]

Her small room is full of mild baroque, renaissance music. Some days, she would wallow in boredom and be at a loss about what to draw. With a sweet odor of breath, she is a young artist with growing depth of graphic details. I cannot resist the rise and fall of her rhythm in this room. Curled on the floor, she reads, writes and draws. [28]

I sway in a hammock slung cross-wise on our balcony. With gentle rhythm, she sketches with strong arms, happily drawing images. There is contentment as I become lost in the windless motion of her artistic pose, a flurry of fast-forwarded motions. Inundated sounds transfer as endings and beginnings paint familiar memories. Mere nostalgia gathers as I close my eyes and picture her dream room. [29]

"Picking Blueberries," is a tender prologue of a lingering morning. As my insides cave inward, I recall the smell of bushes. Sitting up, I wipe tears from my cheeks. I think of our last blueberry escapade. I smile. Picking quickly, she fills her bucket. A little girl challenges me to a blueberry-picking contest: who can pick more and faster. A little girl in blue shorts and T-shirt safely locked in a blueberry farm.

Figure 12: Picking blueberries [30]

I run my fingers over the portrayal. She knows blueberries are good for you. She understands they are high in anti-oxidants. I clear my throat. Alone, I surround by the memory of her chant, "keep picking, keep picking." A Dali day, with time melting away. Mostly, I picked but other times, I rested. There was teasing in her voice, "keep picking, Mom." When we leave, she was upset! "I could pick all day," she protested. "We'll come back. It's just too hot and I don't want us to get sunstroke," I responded. Pouting, she nodded without conviction. [31]

I convince myself I can face the week. Locked away in a sketchbook of memories, I cling to her photographic spirit. I shut my eyes and examine my world and treasure this ideal room. But there is a damp ache in my throat. Cold gasps escape. One thing I learn from missing her is that there is a compulsion to capture her soul in the palm of my hands. Walking toward the door, I tell myself, apologetically, I cannot drown in the murmur of an ocean. Instead, I need to celebrate her life from her sketchbook. [32]

This is part of motherhood. Learning how to cope without her. Find ways to feel her essence. I want her to be both dependent and independent. But she is my companion and playmate, friend and daughter. In her absence, I have been surprised by my heightened physical need for her. But reviewing her drawings is like a film in slow motion that brings her close. I must learn how to both hold her hand and set her free. Remember the mountains and profound rain that can both wash her away and bring her back to me. We co-exist in an invisible reality. Learn to let go, learn to find comfort in missing her as she has a life outside my cocoon. [33]

Today, when I thought life was wrung dry from her goodbye, images stir in my consciousness. At first, a delirium of breathing. Slowly, I imagine her return. A whistling kettle percolates. There is so much emotion from visualizing. As I stand, a strong grip takes hold. The thought of holding her and laughing with her. Watching her spread her wings and fly over the sea. Feet pointed. Forward and northward, onward and upward. [34]

I return to a normal school morning. She will be all over me about packing her lunch and not being late after school. A pampered little girl, no brother or sister; I am her playmate. Her faraway voice, "Want to see this?" "Want to do this?" The world comes and goes in the tide of our day. There will be more sketches. [35]

Tired, I look around. Sometimes, it takes the shape of things to help me cope. Inside, there is a string of guiding lights. I drift through unmarked moments and turn slowly in my weightless world. Twists and turns in the life of a mother who wants no separation from her child. But today's heartache will evaporate, little by little. The planets will come back into alignment; she will return. And stand like a delicate rose in the sunlight. We will delight in our reunion. As a short, slender form next to mine, my ten-year-old daughter will once again be in my arms. We will embrace. A warm breeze slips beneath my hair. Tears well up, a blast of wind scorches my cheeks. [36]

Performative writing reveals a journey that provides a deeper understanding about the transformative nature of constructing a sketchbook. Though the writing becomes an epiphany (DENZIN, 2001) that transforms a pedagogical context, there are other issues from this journey. I have written autoethnography to cope with grief (LEE, 2007, 2006b). and trauma (LEE, 2006c) After sharing my autoethnography with my daughter, I learn that her thoughts about her sketches had changed. Reviewing the sketches with her resulted in a dialogue about how her sketches helped me cope with missing her. She did not realize my struggle when she left for a one week camping trip. Though she acknowledged she drew the sketches a few years ago, she wanted to create new sketches to include in my next article. Her request to create more sketches lead me to the idea of creating an ongoing movie of her sketches and photos as a household artifact that could be exhibited as a memory book that could be shared with others. Invariably, I have added music and photos in the movie and will continue to add more of my daughter's sketches and photos to commemorate other shared events. Creating a movie performs the sketchbook that triumphs across the implications of using performativity as a way of dramatizing emerging phenomena.

Video 1: A sketchbook of memories [37]

Indeed, there is a metamorphosis from constructing and sharing this article through text and a movie. The transformation evocatively and passionately shares my detailed experiences of fear, grief, and love that provide proclamations of change. Though confessing my challenge chronicles vulnerability, it is the conceptual and analytical shifts of my understanding of research that enables my growth as a scholar. Reflecting on constructing the autoethnography and creating the movie represents the transformative nature of performativity in research. Organizing my daughter's drawings into a sketchbook opens up different possibilities for the way we collect artifacts that preserve our memories about events. Thus, my daughter's sketchings commemorate her insights about delight, triumph, sadness, and happiness about events. The transformative potential from the autoethnographic sketchbook can be used as a springboard for a number of future performance possibilities that include drama, voice, choral reading, and slide show presentations. Overall, creating the autoethnography with text, images, and a movie of the sketches and photos heightens my awareness of performative social science as I "look towards means of (re)presentation that embrace the humanness of social science pursuits" (JONES, 2006, p.67). In the end, this arts-based autoethnography of text, images, and a movie heightened my awareness about the emergent nature of performative artifacts that helped me gain a deeper understanding about the social and cultural aspects of missing my daughter. [38]

Barone, Tom (2003). Challenging the education imaginary: issues of form, substance, and quality in film-based research. Qualitative Inquiry, 9, 202-7.

Denzin, Norman, K. (2001). The reflexive interview and a performative social science. Qualitative Research, 1(1), 23-46.

Ellis, Carolyn (1997). Evocative autoethnography. In Williamm Tierney & Yvonne Lincoln (Eds.), Representation and the text (p.115-130). New York: State University of New York Press.

Ellis, Carolyn (1999). Heartful autoethnography. Qualitative Health Research, 9(5), 273-277.

Ellis, Carolyn (2004) Ethnographic I: A methodological novel about autoethnography. USA: AltaMira press.

Jones, Kip (2006). A biographic researcher in pursuit of an aesthetic: The use of arts-based (re)presentations in "performative" dissemination of life stories. Qualitative Sociology Review, II(1), 66-85.

Lee, Karen V. (2007). George's girl: Last conversation with my father. Journal of Social Work Practice, 21(3), 289-296.2

Lee, Karen V. (2006a). At the beach: Mother and daughter. Lifewriting, 3(1), 141-146.

Lee, Karen V. (2006b). A fugue about grief. Qualitative Inquiry, 12(6), 1154-1159.

Lee, Karen V. (2006c). Her real story. Journal of Loss and Trauma, 11(3), 257-260.

Slattery, Patrick (2001). The educational researcher as artist working within. Qualitative Inquiry, 7(3), 370-98.

Sparkes, Andrew (2002). Telling tales in sport and physical activity. USA: Human Kinetics.

Van Maanen, John (1988). Tales of the field. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Videos

Video_1: http://www.youtube.com/v/WFGTUP6PdKY&hl=en (425 x 355)

Karen V. LEE is a Faculty Advisor and co-founder of the Teaching Initiative for Music Educators cohort (TIME), at the Faculty of Education, University of British Columbia, Vancouver, B. C. Her research interests include issues of performance ethnography, women's life histories, auto/ethnography, music/teacher education, writing practices, and arts-based approaches to qualitative research. Her doctoral dissertation, a book of short stories titled Riffs of Change: Musicians Becoming Music Educators, was about musicians becoming music educators in a classroom context. She is a musician, writer, music educator, and researcher. Currently, she teaches undergraduate and graduate students in both traditional and online learning contexts at the university.

Contact:

Dr. Karen V. Lee

2125 Main Mall

UBC

Dept of Curriculum Studies, Faculty of Education

Vancouver, B.C., V6T 1Z4, Canada

E-mail: kvlee@interchange.ubc.ca

Lee, Karen V. (2008). A Sketchbook of Memories [38 paragraphs]. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung / Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 9(2), Art. 40, http://nbn-resolving.de/urn:nbn:de:0114-fqs0802400.