Volume 9, No. 2, Art. 56 – May 2008

Collective Imagining: Collaborative Story Telling through Image Theater

Warren Linds & Elinor Vettraino

Abstract: This article is a dialogue between two practitioners of Image theater—a technique which involves using the body to share stories. Working in Quebec and Scotland, we discuss the potential ways such a form of performative inquiry (FELS, 1998) can, through an online medium, be documented and disseminated in ways that are coherent with, and build on, the principles of interactive theater. Our hope is that such an exploration will enable the participants in the work, ourselves, and our readers as performative social science researchers, so that we may engage as spect-actors (BOAL, 1979) with the material and build communities of practice through reflection on action (praxis).

A key aspect we consider is ways in which physical dialogue through the body evolves—first as a method of enacting the world, where collective meaning emerges and secondly, as a concept that uses symbolic/metaphoric aesthetic language through what one colleague calls "body-storming" (like "brain-storming," but with the emotional and sensory body as a source and language of expression).

Key words: performative inquiry, storytelling, embodied knowing, practitioner research, image, imagining

Table of Contents

1. Prelude

2. Act I—The Need to Understand the World Symbolically Is in All of Us (FYFFE, 2007)

2.1 Scene I—The beginning of the beginning ...

2.2 Scene II—Group formation

3. Act II—"This Is Your stage. Sit Down, Compose Your Face. Lines Rehearsed in the Waiting Room (CANNON, cited in BOLTON, 2005, p.22)

3.1 Scene I—Story telling and the collaborative process

3.2 Scene II—"I am the beneficiary of the processes I am part of" (FYFFE, 2007)

4. Act III: "Our Revels Now are Ended, these are Actors as I Foretold You, Were All Spirits and are Melted into Thin Air" (Shakespeare, 1670/1939, p.63)

4.1 Scene I: "Imag(in)ing performance research—Only images in the mind vitalize the will. The mere word by contrast, at most inflames it, to leave it smoldering" (BENJAMIN, 1979, p.75)

"Away from the critic

Into the delicious timeless place

Where movement melts into movement

Each entirely as it was meant to be

Imminent and unknown until it arises"

(KERSLEY, cited in BOLTON, 2005, p.62)

This article is a dialogue between two practitioners of Image1) theater in Quebec and Scotland about the ways in which such a form of performative inquiry (FELS, 1998) is used to explore interactive theater processes. Our hope is that such an exploration will enable the participants in the work, and ourselves as performative social science researchers, to engage as spect-actors (BOAL, 1979) with the material, thus building a community of praxis. [1]

This article is set up as a play with several acts and scenes about our work. We interject entr'actes as hyperlinks to provide a commentary on what has gone before and what comes afterwards. At several points we also provide hyperlinks to photos and video and the reader may interact with any of these entr'actes, Images and stories which are part of the textual performance. As HALFORD and KNOWLES (2005) point out, this online medium allows us to show images "to pursue the visual beyond the usual limits of the printed academic journal" (p.1), calling us "to show more images, without losing text: enabling a more sustained and iterative engagement between pictures and text than is normally permitted" (p.1). [2]

Image work is not just a methodology; the images in this text show our theater workshop work as part of an interactive process. So we ask you, the reader, to engage with the Images connected to this text, seeing them as enabling you to participate in the enactment of our work, and not merely as illustrations of our points.

Video 1: Setting the scene: "Everything begins with the image and the image

is made up of human bodies. Through perception of the body

everyday experiences become performance" (AUSLANDER, 1994, p.124). [3]

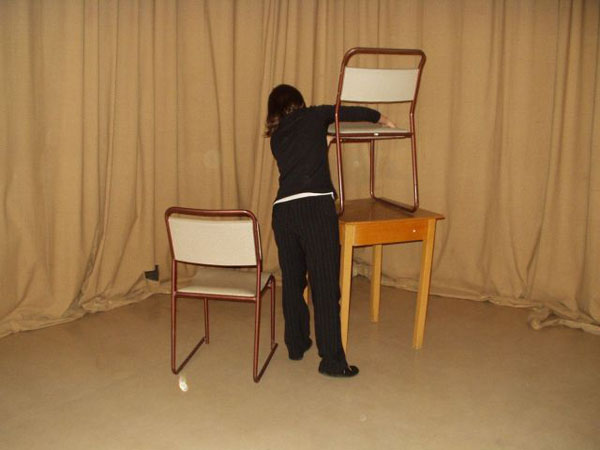

Based on the idea that "a picture is worth a thousand words" (JACKSON in BOAL, 1992, p.xx), Image Theater enables participants to create collectively, with their bodies, static group images that represents their stories. Alternative ways to change relationships of power are discussed through an interactive process between facilitators and participants, thus enabling knowing to emerge. The process of the experience leads to reflection that produces proposals for solutions, which are ultimately tested in new images and thus leads to new experience and a new round of possible actions. This "rehearsal for reality" (BOAL, 1979) enables participants to try out actions in the workshop room so that we may see what might result from our actions. [4]

Changing our view of the world "necessitates a language that speaks to the lived experiences and felt needs of students, but also a critical language that can problematize social relations which we often take for granted" (MCLAREN, 1995, p.74). As forms of re-experiencing and2) transforming our lives, imagery opens up a space for potential exploration among bodyminds where body shapes in images enable thoughts to emerge as individuals step into the realm of the possible co-created worlds. [5]

Sitting there smoldering in our bodily memory, learning becomes more tangible, and, recalling these embodied moments, makes them available for deeper exploration in the future. Drama becomes the interplay between the imagined and the actual, the tangible and the ephemeral. Reflection within drama allows knowledge to unfold and emerge and to become more explicitly known. As SIMON (1994) points out,

"[o]ur images of ourselves and our world provide us with a concrete sense of what might be possible and desirable. What we do in classrooms can matter; we can begin to enable students to enter the openness of the future as the place of human hope and worth" (p.381). [6]

Image is an embodied language that emerges through our interactions with/in the world. A person tells a story and others silently make pictures with their bodies to tell the story. They then freeze in a position to tell one moment of the story. Once the image emerges it can be manipulated in many ways. We can play with the Image through remote control as if it were a videotape—fast forward or rewind to events in the past. Or we can create an Image using more people to show a "slide show" of the story. All these techniques allow for a manipulation of time and space in the "staged reality" in the workshop space. Image and imagination thus become an interplay of structure and de-structure, the image providing a form of closure to play with; the imagination providing a way of opening up the form to possibility. [7]

In our experience, this Image work is a form of both wrighting and writing, which we call wri(gh)ting. Wrighting is more often thought of as creating, or building, something—Play wright; Ship wright; Mill wright. But if one gives it a life on its own and then attaches it to the idea of writing any form of language, then the facilitator must depend on their senses to wright worlds of imagination, crafting new modes of being and relating that which emerges through a form. This form provides us at the same time with the very means by which it can be "read." BOAL hypothesizes that "knowledge acquired aesthetically is already, in itself, the beginning of a transformation" (BOAL, 1995, p.109), so the wrighter has the important role of working with that aesthetic form to strengthen the potential of this transformation. [8]

The story we will now tell is of two journeys the authors have taken in the process of imaging and imagining (what we call imag(in)ing as they are part of the same process and the emergence of the wri(gh)ting process for them as practitioners3). [9]

2. Act I—The Need to Understand the World Symbolically Is in All of Us (FYFFE, 2007)

2.1 Scene I—The beginning of the beginning ...

Elinor's story

As a teacher, reflecting on my own practice has always been a fundamental part of my professional responsibility. The process of standing back from my own experiences and viewing them through a more critical lens has been integral to moving my own work forward. My reflection during my teacher training was always based on words and writing and yet I felt strongly that there were other ways of thinking, feeling and re-experiencing my own learning. Being creative about the approaches taken to reflecting on practice can help to widen and extend one's own understanding of the teaching and learning process. BOLTON (2005) talks about the professional arena being "... opened up to observations and reflections through the lens of artistic scrutiny" (p.11); through observing our own actions and interactions we are placed in an aesthetic space that enables us to play with reality and non-reality, to shift time and focus so that we are engaging with memories in a way that frees us up to mold and re-experience them. By doing this, we learn from and about ourselves in order to change the way in which we then operate within social constructs; potentially among them, our workplaces. [10]

It was this idea of reflecting openly, honestly and visually that led me to begin the work with a group of education workers from a charitable organization. Donna, Anne and Kirsty all work with young people in mainstream and special educational needs schools and classes. Their roles within the organization include working with individuals and groups of children who have difficulties engaging with the school environment for any number of reasons. Anne and I had most recently worked together in a local primary school. I had also worked with all three individuals at other times, in a training capacity, using drama to help them and colleagues understand how to explore different aspects of their work; much of this training was based on the introspective techniques that BOAL (1995) employs in his "Rainbow of Desire" approach to theater. [11]

The project discussed in this article involved three education workers introduced above. All three worked with young people in education and school settings who have become dis-engaged with their educational journey. Elinor developed and facilitated a program of self-reflection through which the three education workers were able to critically evaluate their own practice through Image Theater and the use of sketch books as thinking tools. The program evolved into a series of eleven 1.5 to 2 hour sessions over the period of one academic year during which the participants engaged in the techniques described in this paper, taking their learning back into their practice to enable them to enhance their professional abilities. Helping to connect the participants with each other and with their shared workplace would enable them to explore, in the safety-net of play, deeply real situations. This would happen through the consideration of dilemmas that they faced at work and solutions offered through the collaborative processes that exist within a shared drama experience. The use of sketch-books was also intended as a key aspect of this reflective experience. ROBINSON (1996) speaks about sketch-books as tools for creative thinking. They are not limited to drawings or artistic representations but instead offer opportunities to make concrete the development of abstract concepts and thoughts. This critical thinking tool enables the participant to not only store ideas and thoughts in the pages of the book, but also offers the space to explore these in any chosen form—words, images, spaces, colors, shapes etc. etc. The participant's narrative is often only understandable to the one who created it, thereby potentially offering a safe space for open and honest self-reflection. [12]

Warren's story

Though bodies act, react—and though bodily inscriptions are always reporting some mode of being, thinking, acting on the world—the special moment of "mime" calls attention to this literacy and iterates loudly the sometimes unconscious thoughts and feelings that are verbally incommunicable (BRUNNER, 1996, p.13). [13]

One way I introduce Image as a form of representation is through a handshake in an activity called Complete the Image.

Video 2: Complete the image [14]

Image is a narrative that begins with partners and a simple handshake, a transfer of grounded energy, eyes looking at each other. A simple handshake can say different things with the ways we use the rest of our bodies. If we begin to interplay, we may notice the use of the eyes, the face, the stance of each other. In addition, the handshake becomes a metaphor for my engagement as facilitator with the group I am working with. [15]

Almost every time I do Image work the first response by participants to an image is: what is the person in the Image trying to say? and then the inevitable "guessing" begins. This happens even when I begin with the "Complete the Image" handshake. I emphasize that there is no right or wrong answer. I add that the Image I show at the beginning allows everyone to "read into it" their own story. Despite these assurances, I feel the inertia and habit of "playing charades," of "guessing" what someone is trying to say remains so ingrained that participants cannot trust to let the image be, to come into its own meaning. Similarly, as a writer of performance, I seek ways to create meaning through intertextual play that invites the participant to abandon the expected, the explanatory as they read the embodied text of the image. [16]

Initially, there is the frustration of not knowing in a linear literal way the meaning of the constantly evolving text, adding our bodies to the text, shaping the air, limbs, bodies in relationship, not yet named. And then we revel in the free interplay of simply shaping space and relationship without naming, without preconception. To not expect, nor analyze, nor explain, but to write embodied possibility into the air. [17]

When working with self-reflection, the rationale behind any group formation needs to be carefully considered (BOLTON, 2001). Consideration of who and how many becomes arguably more important when the techniques being employed in the reflective process are ones that would potentially expose the participants' inner thoughts and processes to each other in obvious, and sometimes, raw ways. Indeed, a crucial consideration for the facilitator is that of their role as a guardian—a protector of the material being worked with. The facilitator's strategies must safeguard the participants from negative experiences such as feeling threatened, or being stared at. In Elinor's work with the education workers, the techniques that would be utilized (Image Theater and sketch-books) would require introspection and self-analysis, thus creating openings for individuals to face difficult truths. [18]

In forming the education workers group, it was important to acknowledge what BOLTON (2001) defines as the hidden curricula that exist within groups. She states that: "... everyone brings expectations, hopes and fears which combine with unspoken elements within the group to create curricula which are not stated and might be either productive or harmful" (BOLTON, 2001, p.58). Therefore, the membership of the group had to be supportive and comfortable for all. All members had to feel confident that their individual journeys within the process would be respected and valued and, most importantly, that they would gain from the experiences they would undergo; becoming truly reflexive in their practices. [19]

Developing and maintaining connections whilst enabling individuality within a community is vitally important in group dynamics. This has to be done every time one works together with a group, done anew, beginning new conversations. RINGER (1999) links this aspect of connections to the need for adequate containment in groups where participants have a "sense of being firmly held in the group and its task, yet not immobilized by the experience" (p.5). SALVERSON (1996) says this firmness with flexibility means there must be a space or gap within the container. This form is molded as we work together holding "the circle of knowing open and invites a current that prevents steering a straight line through the story, or arriving at predetermined destination" (p.184). She refers to Jungian therapist and writer Marion WOODMAN's notion of the container as "home," but a home that is open to possibility, the possibility of being wrong, with a gap ensuring "there is always something more to say" (SALVERSON, 1996, p.186). [20]

Facilitating such processes that have no straight line to some predetermined goal involves risk-taking. It's about providing a frayage, an opening or an interruption that "breaks a path" (NANCY 1997, p.135), developing a container of safety, where risking is possible, where storytelling is possible, where witnessing stories is possible. [21]

3. Act II—"This Is Your stage. Sit Down, Compose Your Face. Lines Rehearsed in the Waiting Room (CANNON, cited in BOLTON, 2005, p.22)

3.1 Scene I—Story telling and the collaborative process

Boalian techniques work with that which is real; with stories which are individuals' truths. The techniques of the arsenal of the oppressed should be played with, expanded, used by individuals to learn about themselves and their abilities to change their truths. LORENZ hints at this when she says "it's so clear in Boal's work that we're in this room doing things together for the sake of something that's outside the room. A rehearsal for something" (LORENZ cited in SCHUTZMAN, BLAIR, KATZ, LORENZ & RICH, 2006, p.63). However, the something is both inside and outside of the space; it is both the reality of the external and internal worlds that are being developed through the image work. The creation of story is one way in which individuals are able to share their inner realities with others. This is not to say that the individual's needs alone are exercised in Theater of the Oppressed (TO) work. BOAL's approach is to consider the pluralist individual, the shared understanding of an individual's story. Through enacting shared stories and playing out different possibilities, new ideas can be molded and perceptions shifted. Without a group dynamic it becomes "Theatre of One Oppressed" (BOAL, 1995, p.45) [22]

And so, story telling is an important aspect of Image Theater. It is a powerful and historically significant social experience. GERSIE and KING (1990, p.31) note that: "… each story is an emblem of existence, the symbolic representations of someone's interpretation of reality, of the interaction between the inner and outer world." FINLAY and HOGAN (1995) speak about stories as being the glue that holds an organization together; and this is perhaps not too strong a statement. Think of the stories that inspire the shared laughter of friends, the unspoken directives that exist between colleagues, the victorious, tragic, bloody and secret histories of countries. Story telling connects to the affective part of the brain; the part that feels and hurts and laughs and angers. If stories are indeed "... the gatekeepers between our inner and outer worlds ..." (GERSIE & KING, 1990, p.35) then they exist at the very heart of who we are and what we might be. [23]

The telling of a story potentially brings both teller and listener to the beginning of a process of understanding of who and what the story might be about and, consequently, who and what we, as the teller and listener, might be about. The teller always takes a risk in this process. GERSIE and KING (1990) talk about this risk as in terms of the response that the teller might receive; rejection, criticism. However, through the risk taking, transformation can occur (FYFFE, 2007). When a teller recounts their story, the spect-actor/listener in Image Theater then has a great responsibility for the re-creation of the tale. although the teller will never know how the story has been truly received as they are only the deliverer in the dialogue and not the recipient (GERSIE & KING, 1990). Professional self-reflection is also all about story telling in order to better understand the "meaning behind action." BOLTON (2005) discusses this in connection with writing narrative reflection when she states that writing "... fiction from depth of experience, enables people to grapple with everyday issues at the same time as abstract feelings. Writing an abstract and generalised piece about mistakes ... offers no access to deeper levels of meaning and understanding" (p.51). [24]

In the same way, using imagery to express something that can not be presented in other ways allows us to explore paradoxes—coexisting and conflicting opposites. It is these visual contradictions in the embodied relations in the Image (for example, someone smiling while doing something an observer wouldn't think would result in a smile), that are complex prompts that open up questions, moving the exploration of the theme into where there are more knots that need to be worked through. Image becomes part of a spiraling process which sparks our imaginations, enabling us to dream of alternative futures. [25]

JOHNSTON (1998) notes that once the visual language of the Image is learned, the paradoxes in a workshop between individual and collective experiences and surface/depth explorations become fruitful spaces to challenge a group in its exploration of a theme. LIPSON LAWRENCE and MEALMAN (1999, n.p.) talk about this story telling space as being "... fertile soil where the collective knowledge takes root." So the wri(gh)ter is both a teacher of the visual language and also, via this teaching, uses the language to shift the group into another level of exploration. Thus, in order to enable the participants in Elinor's study to reflect upon their own professional experiences, they needed to engage in the story telling process. With such a small group number (by the third session the group were down to five members including Elinor) Elinor as Wri(gh)ter/Joker4) wanted to offer a range of ways of developing images from the individual and collective stories whilst still retaining an emotionally and physically safe space in which to work. [26]

The first five sessions built on non-verbal images that were created sometimes individually and sometimes as a group. These sculptures were often created with physical connections but sometimes without; linking participants together at times and at others, deliberately separating the images. Through these images, participants began sharing the role of story teller; whether physically connected or not, the group's togetherness enabled them to begin to create meaning for themselves and each other. LIPSON LAWRENCE and MEALMAN (1999, n.p.) suggest that one of the main purposes of this sort of collaborative inquiry is "... to deepen the understanding of one's experience, to gain an understanding of and from fellow inquirers, and together develop new understanding of some shared phenomena." Thus, as the sessions developed, the journey itself through the dramatic process became the pivotal experience. [27]

The group made an initial image which identified their own professional concerns. This image was constructed without speaking; even so, the individual sculptures offered similar images to the audience. The image to the left represents the group's process of liberation from this collaborative image created to represent a shared oppression. [28]

"Knowledge is a negotiated discursive construct" (JONES, 2006, p.70) built in part through the telling and shared interpretations of stories. Many of these grow in an unstructured manner and Elinor was keen to create an environment where this organic dramatic process could flourish; where it could grow, take shape and flow in its own path without clear direction but instead in a way that came from sometimes unspoken areas of interest. One of the interesting outcomes of this approach became the incidental learning that took place as a result of a weaving together of ideas and existing knowledge to create new meanings for the participants. This echoes MEALMAN's (cited in LIPSON LAWRENCE & MEALMAN, 1999) findings that the value of incidental learning in a shared activity such as collaborative story telling can be greater than the intended learning. [29]

Building on the non-verbal work Elinor did with her group, she wanted to introduce the idea of storytelling through the creation of myths or legends. These would be focused on and around issues for the group within their own professional context. BOLTON (2005) discusses the idea of abstract writing—such as the creation of myths around reality—as being self-protective and this was a key reason for adopting this approach. Whilst the nature of self-reflection is linked to transformative behaviors, Elinor wanted to ensure the safety of the group in the context of the stories told. To do this Elinor adapted a technique called 6PSM5). Whilst this technique originates from a therapy base, it can also be adapted and used to develop storytelling processes for creative writing and, in this case, reflective wri(gh)ting. The stimuli for story creations came from a set of picture cards called SAGA6). These cards are similar in shape and appearance to playing cards, the difference being that instead of suits of color on the faces, the cards have a variety of images ranging from pictures of landscapes and people, to abstract images of half hidden doorways or swirling shapes in the sky (see picture below of an example of these cards). [30]

DONNA: We were asked to write up an imaginary story using Saga cards which related to our work. We would then act them out with different attitudes, feelings, emotions, personalities and behavior.

ANNE: I wrote my story about the challenge I have to look for solutions to my struggle in accepting my role. I wanted to explore the relationship I have with my role and how I could change to become more effective.

DONNA: Doing this story process with Image Theater made me realize how powerful this was! When we were acting out these different characters. It was the first time I noticed my behavior change.

Movement between images enabled the participants to, as BOAL (1995) refers to it, dynamize the psychological and physical change from one way of being to another. [32]

ANNE: the three movements one [exercise], do you remember?

KIRSTY: yes, where we made one image and moved to another and another?

ANNE: yes! That one! That one made me really think ... I got to the third image and I sort of moved into it but I was thinking "I don't know if I really want to do this or not but, hey, do it anyway" and then I just moved ... not for long ... but it felt good being in that position and I thought "I wonder if I could do that more ... you know, at work."

Participants also worked in their sketch books before and after sessions in their own ways (images of these are shown below). In some cases there was a great deal of written text, in others symbolic and iconic imagery were used to work through the reflective process. [33]

|

|

|

KIRSTY: I'm not sure how this helped me with reflection but I knew I could be as creative as I wanted to be and there was no right.

DONNA: I saw mine more as a creative diary, using all kinds of materials. Something that I could use to illustrate my own thoughts, feelings, emotions, my imagination ... even my own drawings.

KIRSTY: I suppose so, I have gone back to mine so ...? [34]

Objects were also used to consider concepts of power and trust (as can be seen in the images on the left and below). An adaptation of the Game of Space and Power (BOAL, 1992) activity was a key point within the work enabling the group to embark on a discussion around perception of power and authority; offering analysis of their own experiences connected with the images created. [35]

Listeners in the story telling process are also vital. As mentioned in the first Entr'acte, in BOAL's Image Counter-Image (1995, pp.87-91) he describes the listener as the co-pilot to the story teller's pilot. To begin the exercise he invites the pilots to choose their listeners and then to quietly retell their stories to these co-pilots; both with eyes closed so as to aid the process of speaking and hearing. Questions can be asked by the co-pilot to ensure that they have all the information they need to move to the second stage of the exercise which is for both parties to create images of the stories they have told/heard. In BOAL's work the pilots and co-pilots use members of the spect-actor audience; in Elinor's group of four the participants made use of any objects around then to recreate their interpretations of the stories they had been pilot/co-pilot in. [36]

The value of this exercise (an image of one of the group participants engaged in Image Counter Image is below) linked to the concept that listeners in the story telling process can interpret what they have heard in different ways. Sometimes the image they see and then create (with bodies or objects) is markedly different from the image constructed by the teller but this doesn't make the listener wrong; what it does it to offer another possibility to the teller, and possibilities open the door to transformation. [37]

3.2 Scene II—"I am the beneficiary of the processes I am part of" (FYFFE, 2007)

The British drama educator Dorothy HEATHCOTE (2000) writes of the teacher as craftsperson, "a maker collaborating with the nature of the material" (p.32). We would call this process wrighting because "it performs its intention in collaboration with the readiness of the material to receive the stimulation" (p.32). In the same way, the facilitator or Joker within Image Theater work is a fellow wri(gh)ter/collaborator in the visual mix of conceptualizing and concretizing story. A (perhaps) simplistic explanation of the Joker's relationship to the group would be that she is "... a contemporary and neighbour of the spectator ..." (BOAL, 1979, p.175) but her role is to act as a conduit for transformation; part of the group but apart from the group. The wri(gh)ting process for the Joker/facilitator is a dynamic journey where their interventions are tempered by a sensitivity to the nature of the materials. Rather than a canvas or piece of the clay, the "materials" in drama are "intelligent clay." This is the heart of the challenge which Joker/wri(gh)ter faces and the reason why s/he needs a wide range of strategies and negotiation skills in order to sense how the intersections between flow of the material and the rigor of the artistic technique bring an experience to life. In addition, the Joker/wri(gh)ter's part in the story telling process changes and evolves as the story evolves. Empathetic responses are natural reactions to stories that have universal themes and so the Joker/wri(gh)ter will connect with the stories being told externally as well as internally. This is an important point to consider as the Joker's responses and therefore the strategies they employ with a group can have a profound impact upon their own internal monologues. [38]

A key transformative point linked to the changing nature of the Joker/wri(gh)ter role came in the sixth session of Elinor's work. By this point the group consisted of three workers and Elinor. Initially, for pragmatic reasons (the group size), Elinor recognized that she was engaging more as a participant in the process; being able to be an extra physical body in the development of image work became beneficial. Elinor, as Joker/wri(gh)ter had developed connections with the participants engaged in the story process. Though the wri(gh)ter stands focused on working with the storied and storying bodies in front of them (or those that are absent), the wri(gh)ter works from their own body, in their own body, through their own body. The wri(gh)ter becomes aware of the role of their senses, listening, hearing, playing with the Image as tactile aesthetic form. This is the difficult work of forming the informing and informing the forming as the wri(gh)ter perceives the moments where the world of the Image is presented to all. [39]

ELINOR: The move into the SAGA stories came in the sixth session. This was where I felt my journey into the unknown became more evident. Although I was preparing for each session that we had, I realized that—more and more—I was relying upon the pull of the group to guide me to choosing a particular technique or specific focus for each week. My role was changing. I was becoming something very different; I was becoming a fellow collaborator, journeying with the others as a reflective participant, using my own work experiences to inform the process as well as to learn about myself and my own professional interactions. [40]

WARREN: Working with real clay, potter Ellen SCHON (1998, n.p.) points out, "I try to push myself to be open to the reflective process in order to be more responsive to what the material/situation is telling me so that I don't impose my tools and ideas on the material in a mismatched way." This is perhaps one of the ironies for the wri(gh)ter/Joker; that though I as wri(gh)ter stand there focused on working with the storied and storying bodies I see in front of me (or those that are absent), I work from my body, I work in my body, I work through the body. I become aware of the role of my senses, listening, hearing, playing with the Image as tactile aesthetic form. This is the difficult work of forming the informing and informing the forming as I perceive the moments where the world of the Image is presented to us. [41]

ELINOR: The change of role shouldn't really have been a surprise to me. BOLTON (2001, p.57) states that "the role of a good facilitator involves Socrates' attitude—that of not knowing the answers but being willing to enter into a joint investigation and enquiry." Reflecting on the process myself, I could see that I had an expectation of myself that linked to leadership of the group and being responsible for ensuring that the time that we had together as a group was used productively. Being comfortable with allowing the work to flow took some getting used to; perhaps this says more about my background as a teacher?? [42]

The wri(gh)ter is a type of spect-actor in the performance before any performance for others. The wri(gh)ter, as facilitator, depends on their senses to intervene so that they can mould the work, keep it open, so that they can respond to what they have seen, heard and felt from their vantage point as spectator. In this openness, wri(gh)ter keeps the text of the work open to possibility—that all has not been said or done, and that there are mysteries hidden beneath, behind and around the work that can never be writ/wrighted (nor divined). As HOFSTADER (1979) writes of writing from image (much like the work of Image Theater is writing through image):

"Think, for instance, of a writer who is trying to convey certain ideas which to him are contained in mental images. He isn't quite sure how those images fit together in his mind, and he experiments around, expressing things first one way and then another, and finally settles on some version. But does he know where it all came from? Only in a vague sense. Much of the source, like an iceberg, is deep underwater, unseen—and he knows that" (p.713). [43]

4. Act III: "Our Revels Now are Ended, these are Actors as I Foretold You, Were All Spirits and are Melted into Thin Air" (Shakespeare, 1670/1939, p.63)

4.1 Scene I: "Imag(in)ing performance research—Only images in the mind vitalize the will. The mere word by contrast, at most inflames it, to leave it smoldering" (BENJAMIN, 1979, p.75)

So, what's the connection between performative social science research and what we have just shared? [44]

Image Theater is the medium, subject and re-presentation of research into the issues it is exploring. As medium, Image is the vehicle through which we develop our knowledge about the issues raised; how and why they occur; and what can be done to work with these identified situations. As subject, we ask the question: how does the medium of the Image help us to probe into the issues and experiences of the participants? Finally, as re-presentation, the data is collected by us as researchers in many different ways; through observations, digital photo and video recordings of the development of the Image and the interaction of the actors/spect-actors in and with the image. The participants' interpretations and re-interpretations of the Image are built in new language (for example, other participants "title an Image" or add thoughts to the characters within it) and actions (through suggestions of movements that add to or detract from the original Image) and thereby the Image is continually re-presented as each change occurs. So Image is performance text where text and audience come together and inform one another and we develop a sensitivity to the intuitive, the hither side of words. [45]

We conceive of Image work as a performative method to be researched and validated, but at the same time as a research method into the particular themes that participants want to investigate. LIPSON LAWRENCE and MEALMAN (1999) discuss the emergence of the participants' unconscious stories as being important components of the research process, changing the direction of themes but enabling greater connections to be made. Thus, the Image techniques are a form of knowledge and a way of constructing and presenting that knowledge, which is participatory and performative. The act of telling and listening to stories is one of the research methods involved in the examination of problems around themes of facilitating theater workshops that are revealed during the process, as well as an affirmation that a story is important to those telling it. HERON (1999) points out that whole person learning involves enacting the interdependence of the personal within the world. Image involves not only an individual's story, but also enacts a collective linking of this story to the wider world. In this way our inquiry process is holistic, as "the sharing of individual stories and the development of collaborative stories grounds us in our humanness" (LIPSON LAWRENCE & MEALMAN, 1999). As action inquiry, Image also enables us to focus on the human qualities we share to include our vision of goals, strategies, current actions and their outcomes, and to look at what is going on in the world around us. "It also means noticing and amending ... incongruities between these components of lived inquiry" (HERON, 1999, p.317). [46]

"Collaborative inquiry … is somewhat like crossing a veil into another world of knowing" (LIPSON LAWRENCE & MEALMAN, 1999, n.p.). The different perspectives of what an image means is an important factor in the work. A workshop group will often see many different, but connected, meanings within a single image, often seeing things that the people who crafted the image hadn't thought about. The individuals in the image fill the shapes with feelings and thoughts that come from the interplay between the shape and how they feel in it, and its relation to others in the picture. Thoughts and words initially emerge from the individual's awareness of the static body in the image and the people and the world around it. Images can also be put into motion by asking those watching to suggest the next scenes in a story, or by the facilitator clapping so that each person in the Image moves toward what they want. It is in this creation and activation of the images that the facilitator has to choose methods, tools and approaches based on the particular context, theme and group response. We are interested in developing a better understanding of how performance pedagogies such as Image Theater open up spaces to explore issues. [47]

The work is based on the stories of workshop participants' lives and the enabling participants to discuss issues and search for alternative responses to the problems that are presented. Within this process, we seek to maintain the cycles of research activity where "data is collected, analyzed and presented in dramatic fashion" (NORRIS, 2000, p.45). "Popular theatre is shown to be an effective pedagogical tool and research method in the new insights and critical understandings it yielded" (CONRAD, 2004, p.1).This is also termed arts-based research (DIAMOND & MULLEN, 1999) or performative inquiry (FELS & MCGIVERN, 2002). [48]

We are, and have been, presenting this work in a virtual environment. Exploring representation of stories in Image Theater, this article has incorporated digital images and video recordings in an online environment to enable sharing and archiving of stories and interpretations of those facilitating and participating in the workshops. Following the caution expressed by BARBA (1995), FELS and MCGIVERN (2002), PHELAN (1993) and THOMPSON (2003) in privileging the written word as witness to the theater performance, we have investigated ways that incorporate sequences, sounds, and movement in the participatory research process. In future we would like to explore the use (and ethics) of web-based collaborative authoring tools, such as wikis7), which will facilitate the flow of narratives, conversations and images between and among participants at distance.

Out into the World

I decided to go away into foreign parts, meet what was strange to

me ... Followed a long vagabondage, full of research and

transformation, with no easy definitions ... you feel space

growing all around you, the horizon opens

(NIETZSCHE in WHITE, 1921/1992, p.427) [49]

ELINOR: One of the exciting things for me when writing this paper has been the idea of it being a shared dialogue, and the fact that there are so many layers to this sharing. In a sense, you and I have engaged in our own collaborative story telling process here and through that engagement we have discovered new meanings in our work. Our discussions have helped me to crystallize my own thought processes around the way I work with Image. I have also learned a lot from engaging in dialogues with the participants of the work that I did with the group of education workers. We have created the sense of collaborative self that LIPSON LAWRENCE and MEALMAN (1999, n.p.) talk about; one that "includes our individual selves [and] parts of ourselves that are shared, mutually known and commonly experienced." This layer of the story telling process will continue for both of us because you and I are sharing our experiences with a wider audience of practitioners and researchers, so here is another valuable layer of knowing. [50]

WARREN: I am reminded that the roots of the word conversation, con versare, is "turn together" (FELL, RUSSELL & STEWART, 1994). A conversation through text and images means challenging me to explore how I may bring the reader into the dance between the texts we have written and how they interpret them. But what kind of dancing? SALVIO (1997) relates that, unlike those who dance simply to win by miming other people's steps, the actors in Baz LUHRMANN's film Strictly Ballroom attend to "motion, synergy and the internal and variant rhythms of consciousness" (SALVIO, 1997, p.248) in their own bodies as well as to the bodies of those with whom they live/dance. The meandering between and amongst such bodies means that we must move beyond only intellectual understandings of experiencing something. Feelings must come into play. For it is only when we dance in the flow of emotioning of another can we experience understanding. Then we are moving in the same stream—cognitively flowing together. Other metaphors from physics such as "being on the same wavelength" or "getting up to speed" also reflect this idea (FELL, RUSSELL & STEWART, 1994). [51]

ELINOR: I definitely relate to the idea of being on the same wavelength; this for me is the emotional connection to the work and to the fellow collaborators. When you are excited about something then sharing it enables you to add more to the original idea; you get other people's understandings and energy. As a relatively new researcher (and definitely someone new to performance as research) I want to continue developing the uses of Image Theater as a methodology. I can see connections for me within organizational psychology and how we connect our inner social constructs with our external face; how do we balance our thoughts and actions in complex settings? [52]

WARREN: I am interested in how we might negotiate this tension between the structure of the dance that is this dialogical text and the need to transcend it by using the "variant meanings of motion, space and time to articulate [its] aspects" (SALVIO, 1997, p.248) of our identities as pedagogues? This requires an enactive understanding of language and knowing. As educators, we need to look more creatively at the stances we embody when we engage with texts and seek out diverse modes of interaction that extend written ideas into verbal communication, body language and other forms of performance. [53]

In reading and re-reading the text I recall, I re-collect, I re-embody the actions through the perspective of all the other times I have used it. And these writings enable a productive tension between the tradition of the technique and the transformation of myself who learns by leading the technique ... learnings which can now be fulfilled in other situations. So the next step for me is to be aware of how writing (and writing) this text changes the way I do the work in the future and, conversely, how I may write about it in the future. [54]

"Planning is both creation and calculation. It is a process of fantasy and dream, of imaginatively constructing future and potential experience" (MITCHELL, 1983, p.3).

WARREN: During the workshops I have conducted on issues of racism, the theatrical process of the Image is used to tell, and give representation to the stories of the participants. For example, one technique (Pilot/Co-Pilot [DIAMOND, 2007]) involves one participant telling a story to another. Then each of these two participants creates an Image of a critical moment in the story, placing the storyteller in the Image as themselves in relation to others. The original storyteller then chooses which Image best expresses the moment.

ELINOR: This sounds like Image Counter Image …

WARREN: David DIAMOND has adapted BOAL's work and re-titled some exercises for his particular workshop contexts. Because the Image is a concrete representation of the situation (in that it contains real bodies that can be manipulated, as well as real bodies that express themselves in relation to others and through voice), it becomes easy to manipulate, move forward into the future or back into the past or add elements that indicate other parts of a particular system's structure, or isolate a key relationship. Thus, the theater process transforms the participants' feelings and experiences into language and Images that they can hold up for critical examination by discussing or manipulating them. The participants then step back from these memories to explore the experiences, their ramifications (on others in the Image, and/or on the world of experience outside the workshop), and possible transformation.

ELINOR: This is similar to some of the sessions I developed with the group processing for the education workers project. We looked at Images created by bodies but also by objects and considered ways of moving—people and/or things—in order to effect positive change on the Image created. FYFFE (2007, n.p.) says that "transformation occurs at the moment of taking a risk ..." and this is certainly true in the sharing of self that occurs when developing images from personal story; this is one of the reasons why I sometimes use objects in place of people, to give that one step removed emphasis.

WARREN: I use two types of Imaging processes: one that starts with the word and arrives at the visual—"I say a theme, you visualize it"; and the other starts at the visual image and arrives at its verbal expression—"you create an image and we then verbalize what we see"; this is a circle of imagination and verbal expression. But when we want to go beyond authority, and aim for novelty, originality and invention, then, as CALVINO (1988) says, "the priority tends definitely to lean toward the side of the visual imagination ... these images that rain down into fantasy" (pp.86-7). These epiphanies come through individual or collective unconscious, re-emerging from memories that were heretofore lost. These moments are beyond our intentions and our control, and carry a sort of transcendence, as meaning is found through engagement, revealing "itself as one takes part in its revelation" (BUBER, 1952, p.36). This is what happens but we are, of course, limited by our perceptions of what an Image is about (connected to what I mentioned earlier about guessing, I remember working with Social Work students one time where they all wanted to know the true story behind each Image they looked at).

ELINOR: Yes, this is quite a common issue for groups that I have worked with as well and it sometimes takes a while to help them understand that the security or safety of their experiences can lie in unspoken work. I think that the power of image is that it does not require vocalization. The vocalization comes in the form of the physical responses that individuals give. Often these physical responses are what I think of as symbolic in the sense that a symbol is a shared or universally understood concept e.g.: words.

WARREN: The image as symbol requires us to make a "leap" both into it and out of it. We are limited by our imaginations, which are formed by the world outside the image. But as collaborative exploration, the forming and re-forming of the image means everyone contributes, one by one. The frozen image becomes the prelude to action, "which is revealed in the activation of the image" (BOAL, 1992, p.xx), thus bringing the images to life and discovering the direction or intention in them. <back>

Entr'Acte 2: Ruby the Lighthouse Keeper

As her input to the 6 Part Story Method sessions, one of the participants in the education workersproject developed a story around a character Ruby. The story is as follows:

Once upon a time on the Island of Johnty there lived a lighthouse keeper named Ruby. Ruby was hard working, determined, committed and thoughtful. Although serious at times, Ruby liked to laugh and have some fun.

There were a limited supply of resources on the Island of Johnty and thus many of the islanders had to leave in search of provisions from the neighboring islands. The Island of Johnty had some good links with the mainland and with other islands close by. However, some of the neighboring islands were not so accommodating and in the battle to seek provisions it could be difficult and at times treacherous out on the rugged coastline. Therefore, to prevent these battles occurring the majority of the journeys to and from Johnty occurred late at night and sometimes in rough seas. However, the island was completely surrounded by ferocious rugged rocks apart from a very narrow inlet. Therefore to prevent the boats crashing Ruby's job was of particular importance and she had to regularly maintain the lighthouse to ensure it was working most efficiently otherwise it would result in death.

Ruby was fortunate enough to have a partner who was strong and dependable and also had a lot of experience in maintaining the lighthouse. However, Queen Ishobel who ruled the Island of Johnty although gentle, kind and caring was disorganized and did not share Ruby's vision of planning ahead. Then when Ruby met with the Queen for guidance and resources to support the maintenance of the lighthouse, she often became quite frustrated as the Queen liked to stick only to two techniques to maintain the lighthouse and Ruby often wondered what else?

Therefore, over the years Ruby had become tired, confused and worn out as although she has a supportive she often feels that she is trying to maintain the lighthouse all alone. In her quest to maintain the lighthouse in the most effective way Ruby also feels that she often overloads her partner with questions/wonderings and is not sure if this is OK.

Ruby now more than ever realizes the importance of connecting with others to share their ideas and resources in planning, delivery and evaluation.

The following three photographs show key elements of Ruby's story. There are brief descriptions underneath of possible ideas emerging from each photograph. These descriptions/questions invite responses.

Ruby begs Queen Ishobel!

In the story, Ruby needs Queen Ishobel to hear her plea for more help lighting her lighthouse. One of the characteristics the participants saw in Ruby was neediness. In this picture Ruby is only using this characteristic in her interactions with the Queen (analytical image) to see if neediness will get her what she wants. Queen Ishobel looks unimpressed and bored by the despair she sees in Ruby.

The power of the guard??

The guard became an interesting character in the story. In this scene the guard has approached Queen Ishobel to let her know that Ruby is waiting to see her. The guard revels in her power as she closes the door on Ruby, waiting nervously outside; will she or won't she be allowed to see the Queen??! The guard decides …

Ruby negotiates and Queen Ishobel agrees!!

During the process of the story-play, Ruby tried a number of different ways of behaving to encourage Queen Ishobel to help her. The group talked about which types of behavior were most helpful to her and Ruby incorporated these into her final re-enactment. The result of her calm reasoning was that Queen Ishobel agreed to Ruby's request and she left with what she came for. <back>

Entr'Acte 3: The Wri(gh)ter Writes

Video 3: Cast of characters

A table

Chair….chair….chair….chair….chair….chair

Participants are asked one at a time to arrange the objects so as to make one chair the most powerful object, in relation to the other chairs, the table and the bottle. Any of the objects can be moved or place in any form whatever, on top of one another, on their sides, or whatever, but none can be removed altogether from the space. The group runs through a great number of variations in the arrangement. When an arrangement is arrived at which the group feels expresses power, a participant is asked to enter the space and take up the most powerful position, without moving anything. Once someone is in place, the other members of the group can enter the space and try to place themselves in an even more powerful position, taking away the power the first person established. <back>

"The senses bypass language: the ambush of a scent or weather. But language also jump starts the senses; sound or image sends us spiralling into memory or association" (MICHAELS, 1995, p.178).

WARREN: We are moving forward in our journey into performance. Each step we take through exercises and Image work plays in the tension between process and performance. There is no one moment where suddenly crafting for performance becomes paramount. But each step I take within the workshop brings me closer to direction and form and further away from formless play. Image is one such step. Stepping into Image work doesn’t leave sensory work aside. It deepens it.

ELINOR: I agree. As I have engaged in the different elements of each workshop, the creation of the story has become more evident as an evolving experience rather than a pre-formed entity. But in my group we were not engaging in the Image work for the purpose of performance. Any performance became a vehicle for the learning process to occur. Each image that a group member created became part of the process; so, as you say image is one such step. Stepping into Image work doesn't leave sensory work aside but deepens it.

WARREN: FELS and STOTHERS (1996) introduce performance as an action-site of space-moments of learning, an ecological dance on the edge of chaos that breathes new meaning, new relationships, new possibilities into being, becoming. The term "performance" thus acknowledges both the "process" (journey) and "product" (landscape) of exploration. In this context, every time an Image is fixed for viewing by others in the workshop, it is a form of performance where "a limited number of people in a specific time/space frame [have] an experience of value which [leaves] no visible trace afterwards" (PHELAN, 1993, p.149).

As Wri(gh)ter I then ask, how is Image a language that communicates with the mysteries of the senses, rather than just an instrument or result of knowledge? "In the expression the language of the body , the of is not the possessive but the relational. The body does not have its language, but through its language it is, that is, is allowed to stand forth as itself. The body exists as a vitality or vital force through sensation, its vocabulary. The language of the body is a language of presence" (APPLEBAUM, 1995, p.78).

ELINOR: The body stores experiences that it understands at a deeper, unconscious level so that even the smallest movement conjures up a host of memories and associations. Our bodies often communicate more truthfully than our words because each action is a sensory experience.

WARREN: As we move through sensory exercises we gradually turn from the play of our senses to something more focused on the language of/through the senses. Expression becomes a reflective mirror in which kinesthetic senses of sight, being seen, and feeling are realized and re-cognized. I begin to see what participants are capable of, what disrupts their understandings and what moves them.

This process connects Image to imagination, "as participation in the truth of the world" (CALVINO, 1988, p.88), where images are charged with meaning (energized), connected with outside the individual, outside the subjective, outside the objective. Playing in the spaces between Image/imagination can also mean there is a third option—an exploration of the "potential," the "hypothetical," "of what does not exist and perhaps will never exist but might have existed" (CALVINO, 1988, p. 91).

ELINOR: We have talked about imagination. What do you understand this to be? Is it separate from our actions, occurring only in the mind of the spect-actor?

WARREN: CALVINO (1988) speaks of it as being "the way the senses have of throwing themselves beyond what is immediately given, in order to make tentative contact with the other side of things that we do not sense directly, with the hidden or invisible aspects of the sensible. And yet such sensory anticipations and projections are not arbitrary, they regularly respond to suggestions offered by the sensible itself" (p.58). In our work, imagination becomes Image, not only, as I wrote a few years ago, "[to make] thought visible" (LINDS, 1996, p.1), but also to enable imagination to emerge through Image. This enables us to become mindful of things on the "hither side of words," these mysteries evoked through Image which move us.

ELINOR: Image and imagination are then fundamentally linked. It is not possible to have a visual image in the physical form of the body without having the record of this image in our heads. You asked a good question about how do we write down these images "... recording each arm, leg, head in its position, or do we write down the evocations arising from those within or without it?" (LINDS, 2001b, p.182) I think that the image is stored in the physicality of the action. BOAL said during a workshop once that theater was thought in corporeal form; the images created are thoughts that the body remembers.

WARREN: I offer no solution to this paradox, but it does lead to an observation that Image is not separate from oral or written language but possibly part of the process of knowing that includes the visual, the oral or the written. As re-creation, not re-presentation, "a work of art expresses a conception of life, emotion, inward reality, but it is neither a confessional nor a frozen tantrum; it is a developed metaphor, a non-discursive symbol that articulates what is verbally ineffable—the logic of consciousness itself ..." (LANGER, 1957, p.26). Thomas MOORE, the editor of some of HILLMAN's (1991) writing, explains, "… if there is a latent dimension to an image it is its inexhaustability, its bottomlessness even subtle moves with an image can turn it into a concept or link it into an abstract group of family symbols … a particular image is a necessary angel waiting for a response" (MOORE, 1991, pp.50-51). You don't translate image into meaning, it's just there bearing witness to the experience it both represents and evokes in its presence.

ELINOR: I know what you mean but the beauty about image is that you DO translate it into meaning, whether you want to or not. It's a natural human tendency to read meaning into what you see, and that meaning is connected to your own existing schema around what you are seeing. Yes, this meaning can be bottomless or inexhaustible, but there definitely can be meaning and sometimes these meanings can be shared.

WARREN: John HERON (1989) outlines meaning as involving four forms of understanding: conceptual, imaginal, practical, and experiential. He writes that experiential learning interweaves "these four sorts of understanding in such a way that they make a relatively permanent change in a person's behaviour or state of being" (p.63). He adds that the "imaginal" form of understanding is often ignored. I agree with him that when we talk about meaning, we are often referring to conceptual meaning.

ELINOR: How does HERON define imaginal and how does that connect with what we understand conceptual to be?

WARREN: "Understanding configurations in form and process. It involves an intuitive grasp of a whole, as shape or sequence" (HERON, 1989, p.13). So conceptual meaning becomes the basis of "naming" these images. (FREIRE [1970] calls this process "naming the world" [p.77] through the word.)

ELINOR: So imaginal understanding creates a more iconic connection for us. We see images or are part of them, we have our own personal understanding of what these mean. Conceptual is more connected with a wider understanding and is symbolic in the sense that symbols can be shared experiences. In relation to image work, both are true. I know that when the group engaged in the game of power and space, both iconic and symbolic imagery was present. As facilitator/joker made my own personal connections with the images I was witness to but through the responses from the group it was clear that there were symbolic references for all.

WARREN: Conceptual is a verbal process that refers to expressions of statements and propositions. Imaginal is much more symbolic and metaphoric. These are not exclusive; they are interdependent. I think Image work bridges and integrates both conceptual and imaginal ways of knowing the world. This links to what HILLMAN (1991) (drawing from JUNG) calls "active imagination." "Active imagination aims not at silence but at speech, not a stillness but at story or theatre or conversation. It emphasizes the importance of the word, not the cancellation of the word, and thus the word becomes a way of relating, an instrument of feeling" (HILLMAN, 1991, p.57). I think now of the way dialogue has been created via the Image participants have developed together. Participants will often refer back to the Image (which is no longer in front of them) in their discussions later on in a workshop.

ELINOR: Ok. So how do we, as facilitators, develop this active imagination, both in ourselves and in those we work with …? <back>

"... in front of the mirror, the child discovers his first identity, his first power, his first voluntary repetition … I am the captain of my image, which obeys me" (BOAL, 1995, pp.104-105).

ELINOR: In my main role as an educator of training teachers, self-evaluation/reflection is the basis of not only my work but my students' also. Unpacking the pivotal moment or explosion (THOMPSON, 1999) in someone's story is a powerful experience, made more so through the use of image. During the de-briefing times that we had at the beginning and end of sessions, the participants engaging in the education workers project work spoke about many key moments in their understanding; revelations about themselves as professionals and as people. Often participants aren't aware of the Image that they physically inhabit and mirroring what is seen can enable them to change the moment. Each enactment changes the experience and the learning that is generated from it; no two ways of playing it are the same. In particular, I remember something that Donna spoke about which for me connected very strongly with the concept of metaxis which BOAL (1995, p.43) defines as "the state of belonging completely and simultaneously to two different, autonomous worlds; the image of reality and the reality of the image." Donna spoke about the experience of seeing someone else playing out her story as being one of the most memorable and important parts of the workshop. When she created her story, she felt she was too embedded in the issue to see outside of it. "It was like being in a house … you are stuck in a room and all you can see is the furniture and things in the room from one level. You can't see through things, you would have to move in order to get a better picture. When I watched Anne being Jaree (the main character in Donna's story) it was as though I was standing over the house and lifting the roof off!!! I could see all of it" (Donna).

WARREN: When I ask students to write reflections of their experiences in class, one of the last questions I ask is what did you learn from describing and analyzing your experiences? I also ask the same question of myself and my experiences. Engaging in theater requires us to be in the moment of performance. In order to achieve this, I need to re-awaken the memory of my senses and re-connect with them, with these muscles, and with this body. Writing from and through this sensing body means reflection on practice is not only a reporting through writing—it is the writing and thus, the "kinds of writing employed will constitute the kinds of reflection enacted" (BLEAKLEY, 2000, p.12).

ELINOR: This brings us back to an earlier discussion about the stories that you see in images. The reflections that we see in the images we create are based upon our own experiences of molding ourselves or being molded. We embody the Images of others and learn more about our own physicality through this. EMUNAH (1994) speaks about this as mirroring; getting into the physical space of another in order to inhabit their understanding of the world. This is a very dynamic exercise that can energize and provoke individuals into action and re-action. An example of the power of reflecting an action occurred in a previous workshop that I led a number of years ago with students on a social work course. They were creating scenes for a Forum Theater presentation, and in one of the scenes involving a battered husband, the wife character-actor was engaging in a very physically violent scene. Although she could rationalize and speak about the horror of her character-actor's behavior she had no real concept of how it appeared to others. So, we reflected back to her through engaging one of her colleagues to mirror her stance, posture etc, one of the images she created which involved her about to beat her husband and his character-actor cowering before her. In seeing this image the wife character-actor was immediately struck by the power and anger she portrayed, so much so that she felt uncomfortable about engaging in that role any further.

WARREN: We become aware of feelings, thoughts, and physical responses to those events as they are happening. Through writing, we then put into practice our awareness so that it has unpredictable effects for me and my practice, thus becoming part of my teaching. The re in reflection is not a second look at my practice, but a re-activation of presence, "making it bloom, bringing it alive and into the conscious presence of its being" (SMITH, 1995, p.77). The dynamics of this writing that incorporates educational bodies with/in worlds of practice becomes markedly different from introspective forms of writing. Writing becomes an homage to language itself, where "language offers the very ambiguity, uniqueness and value conflict that Donald Schon characterizes as the 'indeterminate zones of practice' that we must inhabit effectively in establishing practical artistry as the heart of reflective practice" (BLEAKLEY, 2000, p.11).

ELINOR: I like the idea of reflection not being a rewinding into practice but an activation of something new. "We teach and write to become what and who we are ..." (WEN-SONG HWU cited in BOLTON, 1995, p.66) I think that when we engage in the forms of wri(gh)ting expressed in this article we are paradoxically adding layers of complexity and at the same time revealing greater understanding of our own practice as facilitators of Image Theater processes. When the education workers group developed their mythical stories using the SAGA cards, I began that process by modeling the practice. I turned up six cards and told a story about an issue in my own professional life; one that was current and unresolved. In beginning the activity I was merely hoping to demonstrate the technique but in undertaking the story telling process I gained a greater insight into my own feelings and actions around the issue presented with my words and ideas being reflected back to me by the group. I came away from that session having adopted the dual role of facilitator/joker and participant. I relate this level of learning very much to BOLTON's (1995) concept of Alice falling through the looking glass and entering a world which is very different from her own. What a different experience she would have had had Alice stopped to look at her reflection; she would have seen only a "back-to-front image of her accustomed self ..." and know no more about the world than that.

WARREN: The embodied nature of the learning arrived at through reflection cannot be emphasized enough. All thought is a consequence of reflection upon embodied nervous activity which, through its further interaction with the nervous system, becomes an object of additional nervous activity. "All doing is knowing; all knowing is doing" (MATURANA & VARELA, 1992, p.27). MATURANA and VARELA argue that, through the process of reflection upon experience, we define—moment by moment—our changing world. Explanation then takes that definition into a social domain, creating another context for both experience and reflection. Thus the performance that is writing and the writing that performs (which is the process I engage in) has unknown and unpredictable effects for me and my practice as drama facilitator. This process that allows me to live my knowing, a knowing that includes the ephemeral work that is drama facilitation, those "sites of mystery ... where energies converge ... where we stop and look, that double look, double glance, the sigh, being moved yet not moving" (SCOTT, 1995, n.p.). <back>

1) We will use the capitalized Image to refer to the particular theatricalized use of bodies in frozen motion in a drama workshop. When uncapitalized, image refers to the visual concept. <back>

2) John DEWEY (1929) uses the term "body-mind" to designate "what actually takes place when a living body is implicated in situations of discourse, community and participation" (p.32). Similarly, bodymind indicates "the integration of feeling and thought that emerges from/within experiential knowing by our "sensuous and sentient' [ABRAM, 1997, p.45] body" (LINDS, 2001a, p.32). <back>

3) The participants whose stories are described in this paper and who provided the Images during our workshops gave permission (as part of the author's ethical protocols passed by their respective universities research boards) for their photographic and written work to be shared as part of this article. <back>

4) In BOAL's Theater of the Oppressed, the Joker is seen as a bridge between audience and performers in an interactive Forum theater presentation. However, we are extending this role into the workshop process where s/he is the "wild card," sometimes director, sometimes referee, sometimes facilitator, sometimes leader. It is this ambiguous "in-between-ness" that is learned in practice. <back>

5) For more information about how to find out about how this technique is constructed within the context of Dramatherapy work go to http://www.dent-brown.co.uk/new6psmintro.htm. <back>

6) SAGA cards are part of a series of playing-story cards created by EOS Interactive Cards published by OH-Publishing@t-online.de. The artist is Ely RAMAN. <back>

7) One example of using online wikis after an Image Theater workshop, is at http://www.learningcreations.org/wiki/index.php/Images_of_Reality (We encourage readers to contribute to this online discussion). <back>

Abram, David (1997). The spell of the sensuous: Perception and language in a more-than-human world. New York: Vintage Books.

Applebaum, David (1995). The stop. Albany: State University of New York Press.

Auslander, Philip (1994). Boal, Blau, Brecht: The body. In Mady Schutzman & Jan Cohen-Cruz (Eds.), Playing Boal: theatre, therapy, activism (pp.124-133). New York: Routledge.

Barba, Eugenio (1995). The paper canoe: a guide to theatre anthropology (translated by Richard Fowler). New York: Routledge.

Benjamin, Walter (1979). One way street and other writings (translated by Edmund Jephcott & Kingsley Shorter). London: New Left Books.

Bleakley, Alan (2000). Writing with invisible ink: Narrative, confessionalism and reflective practice. Reflective Practice, 1(1), 11-24.

Boal, Augusto (1979). Theatre of the oppressed (translated by Charles A. & Maria-Odilia Leal McBride). London: Pluto Press.

Boal, Augusto (1992). Games for actors and non-actors (translated by Adrian Jackson). New York: Routledge.

Boal, Augusto (1995). The rainbow of desire: The Boal method of theatre and therapy (translated by Adrian Jackson). New York: Routledge.

Bolton, Gillian (2001). Reflective practice: Writing and professional development. London: Sage Publications.

Bolton, Gillian (2005). Reflective practice: Writing and professional development (2nd edition). London: Sage Publications.

Brunner, Diane DuBose (1996). Silent bodies: Miming those killing norms of gender. Journal of Curriculum Theorizing, Spring, 9-15.

Buber, Martin (1952). Eclipse of God: Studies in the relation between religion and philosophy. New York: Harper & Row.

Calvino, Italo (1988). Six memos for the next millennium. The Charles Eliot Norton lectures: 1985-86. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Conrad, Diane (2004). Exploring risky youth experiences: Popular theatre as a participatory, performative research method. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 3(1), 1-24, http://www.ualberta.ca/~iiqm/backissues/3_1/pdf/conrad.pdf [22/10/2007].

Dewey, John (1929). Experience and nature (2nd edition). LaSalle, IL: Open Court.

Diamond, David (2007). Theatre for living—The art and science of community-based dialogue. Victoria, B.C.: Trafford Publishing.

Diamond, C. Patrick & Mullen, Carol A. (1999). The postmodern educator: Arts-based inquiries and teacher development. New York: Peter Lang.

Emunah, Renee (1994). Acting for real: Dramatherapy process, technique and performance. New York: Bruner-Mazel Inc.

Fell, Lloyd; Russell, David & Stewart, Alan (Eds.) (1994). Seized by agreement, swamped by understanding, http://www.pnc.com.au/~lfell/book.html [25/10/ 2007].

Fels, Lynn (1998). In the wind clothes dance on a line. Performative inquiry: A research methodology. Unpublished PhD. Dissertation, University of British Columbia.

Fels, Lynn & McGivern Lyn (2002). Intercultural recognitions through performative inquiry. In Gerd Bräuer (Ed.), Body and language intercultural learning through drama (pp.19-35). Westport: Greenwood Publishing.

Fels, Lynn & Stothers, Lee (1996). Academic performance. In John O'Toole & Kate Donelan (Eds), Drama, culture and empowerment: The IDEA dialogues (pp.255-262). Brisbane: IDEA Publications.

Finlay, Marie & Hogan, Christine (1995). Who will bell the cat? Story telling techniques for people who work with people in organisations. In Laurie Summers (Ed.), A focus on learning. Proceedings of the 4th annual teaching learning forum, Edith Cowan University, February 1995 (pp.79-83). Perth: Edith Cowan University.

Freire, Paulo (1970). Pedagogy of the oppressed (translated by Myra Bergman Ramos). New York: Seabury Press.

Fyffe, Hamish (2007). Creativity and culture. Lecture given at Critical Connections Conference, Edinburgh, 24th-25th May 2007.

Gersie, Alida & King, Nancy (1990). Storymaking in education and therapy. London: Jessica Kingsley Publishers.

Halford, Susan & Knowles, Caroline (2005). More than words: Some reflections on working visually. Sociological Research Online, 10(1), http://ideas.repec.org/a/sro/srosro/2005-25-1.html [24/10/2007].

Heathcote, Dorothy ( 2000). Contexts for active learning: Four models to forge links between schooling and society. Drama Research, 1, 31-46.

Heron, John (1989). The facilitators' handbook. London: Kogan Page.

Heron, John (1999). The complete facilitator's handbook. London: Kogan Page.

Hillman, James (1991). Blue fire: Selected writings by James Hillman (introduced and edited by Thomas Moore). New York: Harper & Row.

Hofstadter, Douglas R. (1979). Gödel, Escher, Bach: An eternal golden braid. New York: Basic Books.

Johnston, Chris (1998). House of games: Making theatre from everyday life. New York: Routledge.

Jones, Kip (2006). A biographic researcher in pursuit of an aesthetic: The use of arts-based (re)presentations in "performative" dissemination of life stories. Qualitative Social Review, 11(1), 66-81.

Langer, Suzanne (1957). Problems in art. London: Routledge and Kegan Paul.

Linds, Warren (1996). Image theatre: Making thought visible. Unpublished manuscript.

Linds, Warren (2001a). Wo/a ndering through a hall of mirrors ... A meander through drama facilitation. In Brent Hocking, Johnna Haskell & Warren Linds (Eds.), Unfolding bodymind: Exploring possibility through education (pp.16-33). Brandon, VT: Foundation for Educational Renewal.

Linds, Warren (2001b). A journey in metaxis: Been, being, becoming, imag(in)ing drama facilitation. Unpublished doctoral dissertation. Vancouver: University of British Columbia.