Volume 24, No. 1, Art. 22 – January 2023

Innovative Applications and Future Directions in Mixed Methods and Multimethod Social Research

Felix Knappertsbusch, Margrit Schreier, Nicole Burzan & Nigel Fielding

Abstract: In this editorial, we introduce the FQS special issue "Mixed Methods and Multimethod Social Research—Current Applications and Future Directions" by firstly considering changes and continuities in the field since the publication of FQS 2(1) on "Qualitative and Quantitative Research: Conjunctions and Divergences" (SCHREIER & FIELDING, 2001). We then provide a brief overview of the historical development of mixed research approaches over the past 20 years so as to arrive at a concise description of the status quo. We highlight some of the advances made by researchers applying integrative designs in multiple research areas, as well as methodologists analyzing the conceptual groundwork of mixed methods and multimethod research (MMMR). However, we also point out some of the critical issues remaining to be resolved, including the increasing internal fragmentation of the MMMR discourse and a seemingly growing gap between MMMR methodology and empirical research practice. We conclude by introducing the 13 contributions assembled in this volume.

Key words: mixed methods; multimethod research; development of mixed methods and multimethod research; applications of mixed methods and multimethod research; methodology

Table of Contents

1. Introduction

2. Historical Development of MMMR Since the Early 2000s

2.1 MMMR in the 2000s

2.2 MMMR in the 2010s

3. The Current State of the Art: A Diverse Field Marked by Increasing Methodological Specialization

4. Current (Non-)Developments and Future Trends

5. Introducing the Contributions to this Special Issue

5.1 Methodological, philosophical, and sociological reflections

5.2 Combining different types of data and methods

5.3 Applications of MMMR in different substantive research areas

Two decades after the publication of FQS 2(1) on "Qualitative and Quantitative Research: Conjunctions and Divergences" (SCHREIER & FIELDING, 2001), in the current thematic issue we consider the development of mixed methods and multimethod research (MMMR)1) and assess the current state of the art. As we will outline below, researchers have applied MMMR-designs in an increasing number of social research areas, while the methodological discourse on method integration has also become broader and more diverse. Generally, we view this continuing growth in integrative research practice and methodological deliberation as a positive development. However, there are a number of problems attached to it as well, including a potential disconnect between methodological discourse and empirical research practice, and—somewhat ironically—a growing division of approaches within the MMMR-field itself. [1]

Also, the relative success of MMMR as an alternative methodological "movement" (TEDDLIE & TASHAKKORI, 2020 [2003], p.3) should not lead one to underestimate the degree of ongoing fragmentation within empirical social research as a whole. In many fields, the divides between different research cultures seem to have been stabilized, if not broadened, and current methodological disputes are often still characterized by the marks of the old qualitative-quantitative debate, despite the use of a different, more pluralist terminology. Hence, there is good reason to maintain a critical view towards the advance of MMMR as well, and such critical assessment makes up an important part of this special issue alongside the exemplification of its potentials and benefits. [2]

It is telling that at the time when two of us—Nigel FIELDING and Margrit SCHREIER—were editors of the 2001 volume, they did not actually use the term mixed methods. Instead, the special issue was titled "Qualitative and Quantitative Research: Conjunctions and Divergences." To begin with, not using the term mixed methods is indicative of a very different stage in the development of mixed-methods-methodology. In 2001, we were just beginning to see the institutionalization of MMMR. At that time, the Mixed Methods International Research Association (MMIRA) had not yet been founded. The highly influential "Handbook of Mixed Methods Research" (TASHAKKORI & TEDDLIE, 2010 [2003]) had not yet been published, and the first issue of the Journal of Mixed Methods Research had not yet appeared. Mixed methods were still a long way from becoming established as a third paradigm in the social sciences, as it is frequently referred to today (although there is still an ongoing discussion as to whether the use of this term is justified or not: KNAPPERTSBUSCH, 2023). Hence it made sense to avoid using a term that would not be recognized by many researchers at the time. The concept of bringing together qualitative and quantitative research methods was one with which methodologists were more likely to be familiar, especially considering that there is a longstanding tradition of researchers employing such combinations—though not necessarily involving the degree of integration that is characteristic of mixed methods in particular. [3]

The differences in the development of mixed methods in 2001 compared to today also become obvious when taking a closer look at the content of some of those early contributions. Today, putting forward a triangulation and a sequential approach towards combining design elements, as FIELDING and SCHREIER (2001) did in their introduction to the thematic issue, would not be noteworthy in any way. This also applies to the different types of mixed methods designs that MAYRING (2001) presented in his contribution. Today, such points have become standard textbook material. In a similar vein, the contributions featured in the third section of the 2001 issue, titled "Innovative Applications," would hardly be considered innovative now. [4]

At the same time, many points that were made by the authors in 2001 are still surprisingly relevant. This includes, for example, KELLE's discussion of the concept of triangulation (2001; taken up by FIELDING & SCHREIER [2001] in their introduction to the issue). Indeed, triangulation today is rarely conceptualized in the sense of mutual validation, at least not in the context of mixed methods research—a view that was much more prominent twenty or so years ago. But even today few researchers embrace the suggestion made by FIELDING and SCHREIER to think of triangulation as an opportunity for taking a skeptical position towards one's findings, although GREENE's (2007, pp.102f.) concept of "initiation" is somewhat similar (see also: FIELDING, 2009). [5]

Another concept that is still useful in the current methodological discussion is that of methodological hybrids. FIELDING and SCHREIER (2001) mentioned hybrid methods and methodologies as a third approach to combining elements of the qualitative and the quantitative research tradition. They defined hybrids as follows: "By 'hybrids' we mean approaches which do in themselves constitute a combination of qualitative and quantitative elements. These elements may be so closely 'packed' as to be practically indistinguishable" (§33). Several such hybrids were featured in the 2001 issue, such as the approaches of logographic analysis (SCHMITT, MEES & LAUCKEN, 2001) or numerically aided phenomenology (KUIKEN & MIALL, 2001) or the method of knowledge tracking described by JANETZKO (2001). With the emphasis placed by many authors in the mixed methods community on "textbook" approaches and here especially on design typologies (KNAPPERTSBUSCH, 2023, §23), hybrids—which are by definition difficult to place within such typologies—have received comparatively little attention. One exception has been (qualitative) content analysis which has repeatedly been described as such (BURZAN, 2016; MAYRING, 2012; SCHREIER, 2012). Recently, however, increasing attention has been paid to hybrids as a distinct category within—or in addition to—mixed methods under the name of "merged methods" (GOBO, FIELDING, LA ROCCA & VAN DER VAART, 2021). [6]

As we say above, one reason why SCHREIER and FIELDING did not use the term mixed methods in the title of the 2001 special issue had to do with the term not yet being as established then as it is today. But there was another reason as well, and this has to do with the second half of their chosen title: "Conjunctions and Divergences." In other words, they were not only concerned with highlighting convergences between the methodological traditions, but also with pointing out divergences. With the current prevalence of mixed methods, it is easy to forget that mixed methods is not always a good thing. It is not only that research questions exist that are better answered by using a solely quantitative or a qualitative approach. But the qualitative and quantitative research logic does differ in fundamental ways. These differences can be turned into the very strength of a mixed methods approach by thoughtfully combining quantitative and qualitative research elements. But if elements are combined without giving sufficient consideration to these differences, the result is likely to be inferior to an exclusively qualitative or quantitative study. In the 2001 issue, WITT pointed out some such combinations. By applying those, researchers may bring out the worst in either a qualitative or a quantitative research logic. FIELDING and SCHREIER (2001) also highlighted that methods should be combined so as to compensate—instead of emphasize—each other's weaknesses and biases. It is with this in mind that we asked the authors in the current special issue to not only highlight the productive potential of MMMR designs, but to also retain a clear focus on the possible drawbacks and difficulties in their application. [7]

Many of the contributions to this issue have arisen out of the research network Mixed Methods and Multimethod Social Research based at Helmut-Schmidt-University Hamburg. During its four-year period of existence (January 2018-May 2022) the participants of the network project tackled a number of current issues in the development of MMMR methodology, such as integrative data-analysis techniques, MMMR sampling and data collection, or quality criteria in MMMR. The main goal in organizing the project was to provide an infrastructure for constructive, problem-centered, interdisciplinary discussion, and to promote the professionalization of MMMR in German-language communities while also strengthening its ties to the global MMMR discourse. A group of international mixed methods and multimethod scholars from various backgrounds, including psychology, education, political science, sociology, and economics took part in this exchange over the course of seven biannual workshops and conferences. [8]

In continuation of the basic goals and principles of the research network, with this special issue we intended to foster exchange between German-speaking and international MMMR communities. We therefore included contributions from core-members of the network project as well as from international guest experts. When inviting our international authors, we explicitly sought to include European voices into a MMMR discourse still mainly influenced by Anglo-American contributions. In line with this goal of broadening the spectrum of methodological deliberation, we also tried to create a balanced mix of relatively new voices and established experts. [9]

In this editorial, we will first provide a brief sketch of the historical developments of MMMR over the past 20 years (Section 2). We then outline the current state of the field as we see it, including a number of questions and issues to be addressed further (Section 3). After highlighting some important present trends in MMMR and venturing a look at possible future developments (Section 4), we close with an overview of the contents of this special issue (Section 5). [10]

2. Historical Development of MMMR Since the Early 2000s

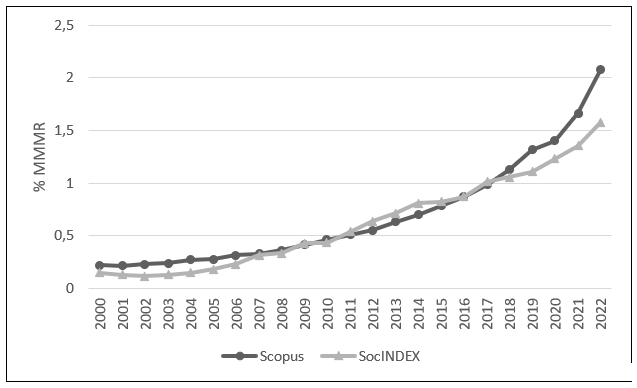

Numerous instructive accounts of the history of MMMR already exist (CRESWELL & PLANO CLARK, 2017 [2011]; MAXWELL, 2016), and there is no need to repeat what others have already reviewed comprehensively. While aiming to avoid such redundancies, we will give a compressed outline of the main trends and issues we see in the development of MMMR methodology over the past two decades. As will be discussed further in the following sections, systematic empirical information on the prevalence of MMMR is somewhat scattered, and available studies often date back ten years or more. However, even a very basic plotting of the percentages of publications including MMMR-related terminology in two major scientific databases reveals a clear positive trend over the past 20 years (Figure 1): MMMR is still very much a growing field.

Figure 1: Percentage of entries containing the search terms mixed methods, multimethod, or triangulation in the databases Scopus and SocINDEX2) [11]

At the start of the 21st century the MMMR movement had already been developed for more than two decades, and there was a growing body of specialized literature, as is evident in the publication of many now classic textbooks during the early 2000s (BREWER & HUNTER, 2006; GREENE, 2007; KELLE, 2008; MORSE & NIEHAUS, 2009; TEDDLIE & TASHAKKORI, 2020 [2009]). The establishment of the Journal of Mixed Methods Research in 2007, which has since been developed into the most visible and influential periodical specifically dedicated to mixed methods, was another important step in this consolidation phase. But the growing popularity of MMMR as a methodological specialty area was also accompanied by a renewed and intensified tendency towards (self-)reflection and criticism within the community. [12]

In the second half of the 2000s, the "reflective period" of MMMR had begun (CRESWELL & PLANO CLARK, 2017 [2011], p.24), which also included several critical assessments of the shortcomings and blind spots of MMMR methodology. Researchers specializing in qualitative and interpretive approaches accused mixed methods methodologists of watering down and constraining qualitative research (HOWE, 2004). Despite the pluralistic aspirations of mixed methods researchers, they claimed, MMMR was in fact used as a cover "for the continuing hegemony of positivism" (GIDDINGS, 2006, p.195; see also FIELDING, 2010a). Other critics tackled the problem of persisting paradigmatic conventions from a more generalized perspective, arguing that MMMR methodologists—often contrary to their intentions—facilitated an uncritical reproduction and reification of an oversimplified qualitative-quantitative-distinction (HAMMERSLEY, 2002; SYMONDS & GORARD, 2010). In a similar vein, some authors questioned whether mixed methods could or should be seen as a distinctive methodological program or paradigm at all (GREENE, 2008; MAXWELL, 2011). It is interesting to note that these reflections and criticisms of MMMR came at a time in which methodologists also pointed to a possible revival of past "paradigm wars" (ALISE & TEDDLIE, 2010, p.103; HAMMERSLEY, 2008) in some research areas, indicating an ongoing demand for integrative and mediating perspectives. [13]

Looking back at the 2001 special issue (SCHREIER & FIELDING, 2001), we find it striking how many of the contributors back then presented ideas relating to the combination of qualitative and qualitative research elements while rejecting the very notion of a clear distinction between qualitative and quantitative. CUPCHIK (2001), for example, suggested constructivist realism as an overarching epistemology; GUTIERREZ SANIN (2001) focused on common methodological problems faced by all researchers alike; KLEINING and WITT (2001) proposed a heuristic orientation as a common starting point in both qualitative and quantitative research; and WESTMARLAND (2001) emphasized the importance of feminism as an orienting perspective compared to a qualitative or quantitative methodological outlook, somewhat akin to what has since been put forward as a transformative approach by MERTENS (2010). The criticism that by advocating mixed methods, researchers in fact uphold the distinction between qualitative and quantitative, has been voiced repeatedly (among others by BERGMAN, 2008; GIDDINGS, 2006; HUNTER & BREWER, 2015). The suggestions made by the above authors in 2001 for situating both qualitative and quantitative approaches within an overarching framework are, in our view, still relevant today (GOBO, 2023). [14]

While arguments about the relation between qualitative, quantitative, and mixed approaches and the paradigmatic identity of MMMR remained inconclusive—which comes as no surprise, given the diversity of methodological standpoints from which they were made—other authors attempted to provide a more descriptive, empirical perspective on the application of MMMR in what came to be called the "prevalence rates literature" (ALISE & TEDDLIE, 2010, p.103). Scholars in this then burgeoning sub-field assessed the spread of MMMR designs in various disciplines and research areas (PLANO CLARK & IVANKOVA, 2016), including sociology (PAYNE, WILLIAMS & CHAMBERLAIN, 2004), psychology (ALISE, 2008; BRYMAN, 2006), health research (O'CATHAIN, MURPHY & NICHOLL, 2007; PLANO CLARK, 2010), and education (HUTCHINSON & LOVELL, 2004; NIGLAS 2004; TRUSCOTT et al., 2010). While the authors of these systematic reviews mostly focused on the prevalence of integrative designs as measured by published original research, with estimates ranging from 5% to 18%, they also regularly pointed to discrepancies between the idealized accounts found in the methodological literature and actual empirical MMMR applications. [15]

For one thing, there seemed to be a lot of unidentified applications of method integration, without any direct reference to MMMR concepts or literature (BRYMAN, 2006; O'CATHAIN et al., 2007; SCHREIER & ODAĞ, 2020; TRUSCOTT et al., 2010). Authors described this as indicative of a growing disconnect between methodological conceptualizations of MMMR and actual empirical research practice that was equally problematic for both sides. While paradigm-debates among methodologists seemed to lack a substantive connection to practical research applications, MMMR users often applied method combinations without systematically consulting methodological literature. Meanwhile, this disconnect is also at the base of methodological difficulties for systematic reviewing, making database-searches an inaccurate tool for measuring the prevalence of MMMR application. Another issue frequently noted in the prevalence rates literature was that even in studies where MMMR was explicitly introduced as a design-feature, the implementation of method combinations often remained rather superficial. Many self-identified mixed researchers did not include distinct qualitative and quantitative data sources in their studies3) (BRYMAN, 2006; NIGLAS, 2004), or made little effort to integrate the results of different strands of analysis (ALISE & TEDDLIE, 2010). [16]

Despite these criticisms, the MMMR methodological literature was further expanded during the 2010s. In particular the number of textbooks and edited volumes was steadily extended, including some of the most popular instructional publications in the field to this day (CRESWELL & PLANO CLARK, 2017 [2011]; GOERTZ & MAHONEY, 2012; HESSE-BIBER & JOHNSON, 2015; TASHAKKORI & TEDDLIE, 2010 [2003]). It was also during this decade that the MMMR field became more established in German language communities, as is evident from numerous influential publications dating back to this period (BAUR, KELLE & KUCKARTZ, 2017; BURZAN, 2016; FLICK, 2011; GLÄSER-ZIKUDA, SEIDEL, ROHLFS, GRÖSCHNER & ZIEGELBAUER, 2012; KUCKARTZ, 2014). [17]

The continuous growth of the MMMR field was also evident in its increased institutionalization in the form of professional organizations and scientific networks. In the year 2013, the Mixed Methods International Research Association (MMIRA) was founded, and it has since been extended by several regional chapters. The MMIRA members organize annual conferences both globally and regionally and provide a steady stream of introductory workshops, online courses and instructional materials. Within the German-language context the research network "Mixed Methods and Multimethod Social Research," funded by the German Research Foundation from 2018 to 2022, solidified and extended professional ties among Swiss, Austrian, and German MMMR experts. The network project has since been carried over into an interdisciplinary Working Group Mixed Methods within the sections Methods of Empirical Research and Methods of Qualitative Research within the German Sociological Association. [18]

But while the professionalization of MMMR was advanced further, including a growing industry of instructional courses and workshops, critical perspectives on MMMR methodology were also continued, with authors still pointing to the prevailing gap between methodology and research practice, but also taking up new issues. Among these was the notion that many MMMR methodologists had pursued what critics saw as an overly narrow path towards professionalization, focusing too much on the promotion of a distinctive research approach and community, thereby turning MMMR into a largely self-referential "silo" (MAXWELL, 2018, p.317; see also FIELDING, 2010b; TIMANS, WOUTERS & HEILBRON, 2019). Among the effects of this narrow, paradigmatic approach to MMMR, critics claimed, were the incomplete and biased coverage of the diversity of integrative research approaches, a restricted exchange of ideas between research areas, and an inaccurate depiction of the history of MMMR (MAXWELL, 2016). [19]

Somewhat similar accusations were directed against MMMR methodology by the proponents of postmodernist approaches, claiming that by employing mixed-methods-designs, researchers merely added an "orthodoxy of integration" to the already existing traditionalisms of qualitative and quantitative research (UPRICHARD & DAWNEY, 2019, p.20), unnecessarily constraining what could be a much more open, exploratory endeavor. Meanwhile, controversies about the issue of paradigmatic conventions and specifically the use of the qualitative-quantitative-distinction within MMMR were being revived, with some authors maintaining that a clear distinction between different (qualitative and quantitative) methods approaches was part of the solution offered by MMMR methodologists, while others saw the reproduction of such categorical distinctions as part of the problem (HAMMERSLEY, 2018; MAXWELL, 2019; MORGAN, 2018). [20]

Hence, over the past decade we see a mixed picture of continuous growth in the MMMR literature as well as its professional organizations, but also critical interjections indicating the continuity of some of the problematic aspects in the field. Unfortunately, the prevalence rates literature in which reliable empirical knowledge on the international and interdisciplinary development of MMMR could be provided seems to have lost momentum. Since its peak around the year 2010 (HOWELL SMITH & SHANAHAN BAZIS, 2021) it has levelled off at a moderate output, with authors becoming more and more concerned with particular sub-fields and methodological specialties (BASH, HOWELL SMITH & TRANTHAM, 2021; COATES, 2021; GUETTERMAN, BABCHUK, HOWELL SMITH & STEVENS, 2019). Thus, current empirical information on the quality and spread of MMMR in the broader social research landscape is scarce, despite the fact that a sober, empirical perspective would be of great use to methodologists engaging in continuing critical discussions about the relation between qualitative, quantitative, and MMMR approaches. This is especially true with regard to comparative work both in an interdisciplinary as well as an international perspective. [21]

3. The Current State of the Art: A Diverse Field Marked by Increasing Methodological Specialization

Over the past two decades MMMR methodology has been developed into a highly diverse field with different sub-communities, many of which are only loosely connected. The methods and methodological concepts referred to as mixed methods or multimethod research—or any other of the numerous related labels—include design-typology oriented approaches (CRESWELL & PLANO CLARK, 2017 [2011]; TEDDLIE & TASHAKKORI, 2020 [2009]), dialectical frameworks (GREENE, 2007; JOHNSON, 2017), transformative, postcolonial, and feminist perspectives (CRAM & MERTENS, 2015; HESSE-BIBER, 2012; MERTENS, 2010), case based methods & set theoretic approaches (GOERTZ, 2017; GOERTZ & MAHONEY, 2012; SCHNEIDER & ROHLFING, 2013), and genuinely integrated approaches such as qualitative content analysis (KANSTEINER & KÖNIG, 2020; SCHREIER, 2012) or network analysis (HOLLSTEIN & WAGEMANN, 2014). [22]

On top of this proliferation of approaches, there are rival conceptualizations whose authors claim to provide a stronger theoretical foundation or a more innovative approach to method integration, such as triangulation (FLICK, 2017) or merged methods (GOBO et al., 2021). These are often paired with a harsh rejection of the supposed "myths about MMR [mixed methods research]" (FLICK, 2017, p.46). However, such polemics also must be read in the context of equally provocative calls for abandoning certain terminology, including triangulation, in order to advance MMMR methodology (FETTERS & MOLINA-AZORIN, 2017; MORGAN, 2019). Looking back at the 2001 special issue, it is interesting to note that the concept of triangulation, which was indicated as "the most prominent among [...] integrative methodological approaches" by FIELDING and SCHREIER (2001, §3), seems in fact to have lost some of its original popularity within the MMMR discourse over the years. That said, its clear and logical foundation, originally introduced by CAMPBELL and FISKE (1959) and later adapted by Norman DENZIN (1978), which made the concept so influential in the first place, is still relevant today. [23]

Somewhat ironically, authors engaging in the current methodological quarrels within the MMMR discourse seem to at least partly reproduce distinctions characteristic of the qualitative-quantitative-divide which MMMR methodologists originally set out to overcome (KNAPPERTSBUSCH, 2020). Some of these fractal iterations of the qualitative-quantitative-debate may be seen as a productive processing of some of methodology's "essentially contested concepts" (GALLIE, 1956, p.167), i.e., perennial problems for which there may simply be no conclusive solution, and ongoing controversy over their true significance has to be considered an integral aspect of their practical meaning. In a similar vein, authors have repeatedly defended the thesis of an "incommensurability" between qualitative and quantitative methodologies (BLAIKIE, 2007; KELLE & REITH, 2023). On a more optimistic note, these reiterations of the qualitative-quantitative-debate may be described as steps on a (however tangled) path towards a less disputed, common understanding of social research methodology—despite their recursive structure. In any case, it does not seem far-fetched to read these recurring qualitative-quantitative-debates as signs that MMMR as a methodological movement has stalled. Caught between the institutionalization of a relatively coherent but highly self-centered methodological sub-specialty, and a relapse into paradigmatic fragmentation of approaches within MMMR itself, the impact of integrative research methodology on empirical social research in general remains limited. [24]

Of course, when voicing such concerns one must also be wary of the abovementioned fact that we still have very little empirical information on the actual extent of MMMR applications in different substantive disciplines and sub-fields. We know that mixed approaches have been relatively prominent in those areas in which key contributions to the early development of MMMR methodology were made, including the applied fields of education, health research, and evaluation, as well as the broader disciplines of sociology, political science, and some areas of psychology. But we have very little current and reliable knowledge about whether these are still the most important areas of application, and a very limited understanding of the lesser-known areas in which integrative research is practiced beyond the boundaries of mainstream MMMR. [25]

Unfortunately, these gaps and problems in current MMMR methodology coincide with a re-intensification of debates about methodological schisms and the qualitative-quantitative-divide in many disciplines and research areas, including sociology (MÜNCH, 2018; RÖMER, 2019), political science (GOERTZ & MAHONEY, 2012), and education (MUNOZ-NAJAR GALVEZ, HEIBERGER & McFARLAND, 2020; PIVOVAROVA, POWERS & FISCHMAN, 2020). Thus, the search for ways to strengthen MMMR as an approach that could be employed in a mediating role in such reoccurring methodological quarrels continues. [26]

4. Current (Non-)Developments and Future Trends

The institutionalization of MMMR, in the form of a professional association, international network with regional branches, and dedicated journals, is a two-edged sword, and, arguably, one of the edges has blunted with time. The markers of institutionalization noted in the previous sentence were necessary, and appropriate, when efforts were being made to establish mixed methods as a distinct methodological approach in the social sciences and to legitimate the activities of those who practiced the craft. While it is somewhat overstating the case to suggest that as a quite diverse methods community mixed methods was sufficient of a movement to have a coherent objective that unified all those concerned, it is plausible to maintain that the approach is now accepted as a distinctive and (to varying degrees in different quarters) legitimate methodological school of thought. But times change. Institutionalization too often means increasingly rigid boundaries and torpor within them. The claim can be made that there is a risk of such rigidity coming to predominate amongst contemporary scholars in methodology, and that those who seek to make innovative contributions in the mixed method domain—examples of which can be found in current efforts to evolve the notion of integration in MMMR (GOBO et al., 2021)—may be met with critics who exhibit a similar measure of skepticism and resistance as the advocates of mixed methods themselves faced from the proponents of established methodological approaches when mixed methods ideas were fresh and new. [27]

One aspect of this, though certainly not specific to MMMR alone (BAGELE, 2020; RYAN & GOBO, 2011), is the underrepresentation and relative neglect of non-western-centric perspectives and scientific communities of the Global South and East in the mixed-methods-discourse, in which Anglo-American perspectives are still quite dominant. This issue, already noted by FIELDING and SCHREIER in their editorial to the 2001 volume, remains largely unresolved on various levels, including differences between European takes on MMMR and the North American perspective, as well as within the European research landscape.4) [28]

As a way to refresh our approach to mixed methods, and to revive the spirit of radical innovation that marked the work of the pioneers in this area, a look forward is a more useful angle than looking back and trying to draw boundaries around what has been achieved. In large measure, what's next is, and will be, fundamentally shaped by the new technologies that have become available for social research, whilst acknowledging that the uses that are made of technology are always entwined with the socio-political context in which such use occurs. And despite the pull of the future we should accord due respect to the mixed methods pathway up to here. One of the most appealing promises of applying mixed methods has always been to achieve a social science in which researchers' analyses offer both the depth of qualitative data and the range of quantitative data. That potential, however seldom achieved, will always remain one of the core reasons of why we mix methods. [29]

A cluster of work by researchers exploiting the affordances of new computational resources shows real promise of reconciling the depth/range conundrum. This includes topic modeling, where researchers derive strictly-controlled abstractions from what they refer to as bags of associated words, thus blending qualitative and quantitative work with big data (ANANDARAJAN, HILL & NOLAN, 2019); the move by those who work with qualitative software toward analytical semi-automation and the incorporation of quantitative analysis tools into such software (SILVER & LEWINS, 2017); the well-established but increasingly analytically powerful fuzzy set approach represented in the work of practitioners of qualitative comparative analysis but performed at scale; and the emergent multi-modal content analysis techniques used by social network analysts for work with social media data, in which these scholars mix intensive indicators of granular relationships across an extensive set of domains (LA ROCCA, 2020). [30]

Mention should also be made of innovative forms of mixed methods of a non-technological kind. An example is what we might call distributed ethnography. In the classic form of ethnography, a rigorous regime of procedures and a substantial time investment are required. A distributed form would involve researchers mixing methods by taking the sampling frame of a relevant or self-designed survey and conditioning that ethnographic regime by repeating the fieldwork component with the principal populations and sub-groups represented in the sampling frame and/or that have emerged as significant in respect of the topic of interest upon analysis of the survey (BAUR & HERING, 2017). The idea is akin to the multi-sited ethnography method (MARCUS, 1995) but here the ethnographers would delve into sub-groups on a systematic sampling basis rather than selecting sites because they strongly feature the phenomenon of interest (see also TANNER, 2023). [31]

The high-potential methodological innovations mentioned here are largely in their nascency, but developing them further promises to contribute to the aspiration of capturing both depth and range. The theorist MacCANNELL (1992) put that aspiration in somewhat more sophisticated form and, in doing so, showed how close the practice of mixing methods is to the very core of our disciplines:

"The social sciences occupy the gap between statistical and symbolic significance. The condition of their existence is to struggle endlessly with the question of the possibility of a convergence of the symbolic and statistical orders on more than a superficial level" (p.92). [32]

One important step towards more fully acknowledging this elective affinity between MMMR and social science methodology in general would be to lay out the specific substantive issues within certain disciplines where method integration would be useful or even necessary, as KELLE (2008) did for sociology. It would be a worthwhile pursuit to investigate more systematically the domain-specific methodological features which make mixed methods designs a highly productive option in other disciplines and fields such as psychology, education, or media and communication research. [33]

Another decisive task for the future development of MMMR will be to more systematically include integrated perspectives in the teaching of social research methods (GREENE, 2010; MERTENS et al., 2017). As yet, most university curricula remain firmly rooted in the traditional separation of qualitative and quantitative approaches, and scholars from both sides naturally are interested in maximizing the space assigned to their respective paradigms (HIRSCHAUER & VÖLKLE, 2017; WILLIAMS, SLOAN & BROOKFIELD, 2017). This is understandable, given the crucial reproductive function of academic socialization for scientific specialty areas of any kind. Also, a commitment to increasing the share of MMMR in methods curricula should not be misinterpreted as a competitive push towards replacing or dismantling established methodological approaches. But the qualitative-quantitative-divide is a prime example of how a highly functional and rational process of specialization can lead to the (unintended) consequence of a fragmented pluralism in which critical discourse is replaced by mutual disinterest, and methodological multilingualism and perspective-taking are crowded out by self-referential expertise. [34]

In anticipation of suspicions that such criticism may itself be nothing more than an expression of a self-centered focus on MMMR, it seems important to emphasize that the current fragmented state of teaching social research methodology not only poses a problem for the development of MMMR as a specialty area—it also constitutes a hindrance to the adequate education of students who are likely to face tasks that require exactly such methodological flexibility and multilingualism in future professional environments in- and outside of academia (FIELDING, 2010b). [35]

5. Introducing the Contributions to this Special Issue

In putting together this issue, we drew upon the research network "Mixed Methods and Multimethod Social Research" based at Helmut-Schmidt-University Hamburg and started out by inviting participants in the network to contribute their insight into current MMMR methodology and/or applications, including but not limited to results from the network proceedings specifically. When inviting these contributions, we emphasized our goal to include a diversity of voices of MMMR researchers from different European countries and at different stages of their career in order to broaden the current predominantly Anglo-American MMMR discourse. In order to achieve this, since the network members predominantly hailed from German-language countries, we further invited some selected MMMR researchers, including both established methodologists and younger scholars at the postdoctoral stage. To allow for accommodating the resulting broad spectrum of contributions—ranging from methodological reflections to MMMR applications—, we decided to include both full-length papers and a research note that seemed more appropriate for featuring specific MMMR applications. [36]

This special issue is organized into three thematic sections (which were also outlined in our call for papers), covering prominent topics in the current MMMR discourse. In Section 1, the focus is on methodological, philosophical, and sociological reflections on past and current MMMR practice, with topics ranging from the consistency of methodological paradigms, through social and cultural factors and their effect on methodological preferences, to the criteria used to assess the quality of different research approaches, including MMMR. In Section 2, we address the potentials and problems of combining different types of data and methods in empirical research practice. In these contributions, current developments in the area of mixed methods sampling procedures, data sources and design elements are covered. In Section 3, the emphasis is on MMMR applications in a number of substantive research areas, including media psychology, education research, sociological museum research, and the sociology of religion. [37]

5.1 Methodological, philosophical, and sociological reflections

We start the special issue with a trio of contributions where contemporary concerns in MMMR epistemology are addressed. Is there a need for paradigm-bound research and where does the claim of ties lead? Udo KELLE and Florian REITH take a critical look at this issue in their contribution "Strangers in Paradigms!? Alternatives to Paradigm-Bound Methodology and 'Methodological Confessionalism.'" Starting from an analysis of the model of paradigm-bound methodology of Yvonna LINCOLN and Egon GUBA (e.g., GUBA & LINCOLN, 1994; LINCOLN & GUBA, 1985; LINCOLN, LYNHAM & GUBA, 2011), they argue that several paradigm-oriented authors work with concepts (e.g., positivism or constructivism), which are not well-defined, lack coherence and are hardly related to contemporary epistemological debates. As an alternative to paradigm-bound methodology, KELLE and REITH propose an epistemologically informed application of methods by employing epistemological concepts as heuristic devices, which can be used to identify and solve methodological problems. They illustrate this approach with an example of their own mixed methods study on religious affiliation and religious attitudes, in which they simultaneously drew on realist and constructivist concepts. [38]

Giampietro GOBO (2023) takes issue with some of the claims and assumptions frequently associated with mixed methods methodology in his contribution "Mixed Methods and Their 'Pragmatic Approach': Is There a Risk of Being Entangled in a Positivist Epistemology and Methodology? Limits, Pitfalls and Consequences of a Bricolage Methodology." He challenges the claim that mixed methods constitute a third methodological approach, arguing that mixed methods researchers frequently follow what is ultimately a (post-)positivist agenda. He sees evidence of this in how measurement is discussed and used in the literature, as well as in the way the concept of qualitative research has been stretched so as to include instances of quantitative methodology (such as the mention of qualitative variables). He then continues by pointing out positivist assumptions inherent in pragmatism as a methodological foundation of mixed methods research. According to GOBO, the seemingly straightforward combination of qualitative and quantitative methods within a pragmatist framework—sometimes characterized as a bricolage methodology—comes at the cost of neglecting the specific methodological foundation of each of these methods or approaches, relegating qualitative methods to the status of mere tools. Instead, he advocates a new epistemic culture based on a new methodological language that allows for reconceptualizing key methodological terms and procedures. [39]

In her contribution "The Fundamental Difference Between Qualitative and Quantitative Data in Mixed Methods Research" Judith SCHOONENBOOM (2023) raises issues that concern the very foundation of mixed methods inquiry, namely the question of what exactly qualifies data as either quantitative or qualitative. Departing from the common assumption that quantitative data are at their core numerical, whereas qualitative data consist of words, she argues that quantitative data are distinct, highly condensed, and are characterized by a specific structure where each number is regarded as the value of a variable; moreover, they can be meaningfully analyzed only through quantitative methods. Qualitative data, by contrast, are considered to be unstructured, rich, and they cannot be meaningfully analyzed using quantitative methods. After describing quantitative and qualitative data in these terms, SCHOONENBOOM goes on to discuss some implications of these definitions. Quantitizing qualitative data, for example, does not, according to SCHOONENBOOM, result in hybrid or mixed data, but in new quantitative data. Most importantly, she points out that if mixed methods research is defined as research where both quantitative and qualitative data are used, the criterion of this definition is met if qualitative data are collected and analyzed using qualitative methods for data analysis and if the qualitative data are then quantitized to yield a new quantitative data set that is analyzed using quantitative analysis methods. In this and several other respects SCHOONENBOOM thus challenges some of the tenets in mixed methods research and encourages us to reconsider the meaning of terms such as hybrid data or crossover data analysis. [40]

Martyn HAMMERSLEY (2023) turns to the controversial question of assessment criteria in his contribution "Are There Assessment Criteria for Qualitative Findings? A Challenge Facing Mixed Methods Research." An obvious problem is that there are no generally agreed criteria for assessing qualitative findings. HAMMERSLEY argues that some important distinctions need to be made if progress is to be achieved on this issue. A very important one is between the standards in terms of which assessment is carried out and the indicators used to evaluate findings in relation to those standards. The author takes strong positions in this context: Thus he rejects the possibility of a detailed and explicit set of indicators that can immediately be used to determine the validity of knowledge claims. Furthermore—and this is where the mixed methods context becomes significant—he denies that there is any fundamental philosophical difference between quantitative and qualitative methods. However, this should not lead to redefining the ontological, epistemological, and/or axiological assumptions of social scientific research at all. Instead, qualitative researchers should accept that the basic standards of validity and value-relevance apply to their empirical work as well, while quantitative researchers should develop greater sensitivity towards the interpretability and malleability of indicators used to apply these standards. [41]

In his contribution entitled "From Paradigm Wars to Peaceful Coexistence? —A Sociological Perspective on the Qualitative-Quantitative-Divide and Future Directions for Mixed Methods Methodology," Felix KNAPPERTSBUSCH (2023) argues that the current state of MMMR and the impact of MMMR methodologists on the social research landscape is ambivalent. His starting point is the observation that even though the merits of integrative research are widely recognized in current methodological discourse, and explicit confrontation between qualitative and quantitative paradigms is generally avoided, social research practice is still very much segregated along the lines of the qualitative-quantitative-divide, while MMMR remains marginal. This constellation of overt pluralism and latent fragmentation, so KNAPPERTSBUSCH, is mainly driven by the social, organizational and cultural aspects of professional social research. This applies not only to the traditionalisms and path-dependencies of qualitative and quantitative approaches, but also to the way in which MMMR itself has been institutionalized as a methodological specialty area. In successfully establishing MMMR as a recognized niche discourse or a third paradigm, proponents of the mixed methods movement have lost their initial critical aim, which KNAPPERTSBUSCH identifies as a "meta-reflexive" critique of methodological schisms (§20). In order to reinvigorate some of MMMR's meta-reflexive critical momentum he suggests the systematic inclusion of a sociology of science perspective into MMMR methodology. [42]

An example of how sociology of science can be used to illuminate the development of mixed methods is provided by Noemi NOVELLO (2023) in the contribution "Communities of Scholars and Mixed Methods Research: Relationships among Fields and Researchers." Starting out from a combination of the new political sociology of science, feminist standpoint theories of knowledge, and the social construction of knowledge, the author uses strategies from citation network analysis (CNA) in order to examine processes of the production and circulation of knowledge within the mixed methods community during the foundational phase from 2003 to 2017. In this way, NOVELLO can identify several distinct sub-communities, i.e., sociology of culture, education, health care, and social network analysis, in addition to the largest sub-community consisting of authors citing experts such as CRESWELL, GREENE, ONWUEGBUZIE, or TASHAKKORI who write about mixed methods from a methodological perspective. These methodologists are cited across sub-communities, thus fulfilling an important role in holding the community together. The same applies to selected authors from various sub-communities who are not cited with great frequency, but across the different research areas where mixed methods are employed. These bridging authors (NOVELLO, 2003, §5) are considered to be crucial for solidifying the mixed methods community during this emergent phase. [43]

5.2 Combining different types of data and methods

Mixed methods researchers have to make decisions at the initial planning stages of a research project, as well as during later stages of the process, and these decisions differ according to the concrete types of data and methods that are to be combined. However, there is little explicit methodological reflection on such differences in the literature. In the following section the authors make such differentiations, namely with regard to qualitative and quantitative longitudinal data, to the combination of visual and verbal data, to open-ended questions in standardized surveys, and to nested sampling in sequential designs. It is noticeable that temporal aspects are often an important part of the methodological issues for which solutions have to be found. [44]

Longitudinal research holds great promise for researching change and continuity, but at the same time there are more methodological and practical challenges than in cross-sectional research. Such challenges are growing when qualitative and quantitative longitudinal research are combined within a mixed methods framework. Susanne VOGL (2023) deals with "Mixed Methods Longitudinal research" in her contribution. She presents the strengths and challenges of quantitative and qualitative longitudinal research and discusses design options with regard to dimensions such as time and timing, priority, purpose, sampling, data collection, analysis and interpretation, and reporting. According to VOGL, temporal aspects are especially important in the mixed methods context, as appropriate design decisions have to be made or revisited in each wave. [45]

Leila AKREMI and Dagmar ZANKER (2023) provide an example of how to mix standardized administrative data and survey data with qualitative content analysis in their contribution "Mixing Standardized Administrative Data and Survey Data with Qualitative Content Analysis in Longitudinal Designs: Perceptions of Justified Pensions and Related Life Courses." The content analysis is applied to open-ended questions in the standardized survey of the study "Lebensverläufe und Altersvorsorge" (LeA) [Life Courses and Old-Age Provision], where respondents could express their opinions and needs with regard to the German statutory pension system. The authors highlight the analytical potential—which is rarely exploited—and challenges of open-ended questions and reflect on methodological issues with regard to an often time consuming process of data collection, interpretation and integration. [46]

Andrea HENSE (2023) compares the strengths and weaknesses of complementing timelines and genograms with narrative interviewing in her contribution "Combining Graphic Elicitation Methods and Narrative Family Interviews in a Qualitative Multimethod Design." In this context, analytical gains in the phases of sampling, data collection and analysis are discussed using the example of a research project on status maintenance in middle-class families. The interplay of visual and verbal data can be used to pursue different purposes, including comparison, mutual compensation, or complementarity. HENSE implements this with a view to longitudinal biographical data and relationships over three generations. In this way, she also provides an insightful illustration of the potential of method integration in the context of an exclusively qualitative-interpretive multimethod design. [47]

Mixed methods sampling is at the center of Pascal TANNER's (2023) contribution "Nested Sampling in Sequential MMR Designs: Comparing Recipe and Result." He focuses on the type of sequential design where an initial quantitative phase is used for selecting cases in a subsequent qualitative phase by dividing the population into subgroups. In this, he draws upon STOLZ (2017) who argued that, provided sufficient quantitative data are available, nested sampling is suitable for including a comparatively large number of cases in the qualitative phase which can then form the basis for describing social milieus. TANNER argues that the principle of nested sampling is equally applicable to the analysis of complex causal relationships. Following a description of the steps in implementing this sampling strategy, he then illustrates the actual application—and the difficulties resulting in research practice—by drawing upon two studies from the sociology of religion. He points out that the effort in implementing nested sampling is considerable, especially if variables other than sociodemographic standard criteria are used for creating subgroups from which to sample the cases for the qualitative phase. Moreover, a core difficulty consists of having a sufficient number of cases to draw upon for each subgroup. [48]

5.3 Applications of MMMR in different substantive research areas

In the first contribution of this section, Jennifer EICKELMANN and Nicole BURZAN (2023) deal with "Challenges of Multimethod and Mixed Methods Designs in Museum Research." Based on two of their own sociological research projects—using different qualitative and quantitative methods—in which they investigated the extent to which museums are oriented to offering experiences and which role museum guards play beyond their security function, they discuss more general opportunities and challenges of mixed methods. They show how MMMR designs can be used to grasp the complexity of the tensions in complex organizations by looking at specific constellations involving different actors and organizational processes. Furthermore it is possible to enhance reflections during the research process by interrelating the perspectives accessed through different methods. On the side of challenges, the temporality of the empirical procedure and the comparability of data and findings are discussed. This includes questions of how linear and iterative approaches as well as parallel and sequential procedures can be integrated, and the extent to which a considered decision is necessary between breadth or depth of comparison. [49]

In their contribution entitled "Mixed Methods in Research on the Psychology of the Internet and Social Media," Özen ODAĞ and Alexandra MITTELSTÄDT (2023) examine the use of mixed methods in a research area that is ostensibly highly interdisciplinary in character, being composed of contributions from psychology, media, and communication studies. ODAĞ and MITTELSTÄDT argue that in practice, however, the field is characterized by methodological compartmentalization, with researchers from psychology and communication studies predominantly making use of a quantitative methodology in combination with regularity-type causal reasoning and researchers from media studies mostly employing qualitative methods and approaches in combination with a subjective meaning-type causal logic. They substantiate their argument by a content analysis of empirical studies published in six purposefully selected journals, two from each field, in the year 2020, clearly showing a field-specific use of either quantitative or qualitative methods and causal reasoning as well as only few mixed methods studies. This compartmentalization, they claim, poses a significant challenge to those wanting to take an MMR approach, as understanding internet and social media use requires taking into account reasons and motives as well as usage patterns. To achieve this, both qualitative and quantitative methods and approaches are required. ODAĞ and MITTELSTÄDT illustrate this based on a mixed methods study comparing acculturation strategies on social media among Turkish and Korean heritage youths in Germany where a quantitative survey and focus groups with subsequent content analysis are both subsumed under a subjective meaning-type reasoning. [50]

Mathias MEJEH, Gerda HAGENAUER and Michaela GLÄSER-ZIKUDA (2023) illustrate the use of MMMR in the field of education. In their contribution "Mixed Methods Research on Learning and Instruction—Meeting the Challenges of Multiple Perspectives and Levels Within a Complex Field" they start by emphasizing the various interrelated levels of the educational system and their reciprocal and intertwined relationships. They argue that using MMMR designs can greatly benefit analyses of this complexity. After briefly outlining the methodological foundations of research on learning and instruction, the authors present two studies from their research program, illustrating significant challenges and opportunities for implementing MMMR in schools. Moreover, they draw conclusions about how MMMR approaches might be further advanced in applied school-based research. [51]

In all three contributions in this section, the authors impressively demonstrate how mixed methods designs can be applied to capture the complexity of social phenomena. It can be assumed that the well-developed but still growing toolkit of MMMR will continue to be an increasingly important resource for social researchers of diverse fields, given their growing interest in the complex interrelations between different actors, perspectives, levels and processes, as indicated, for example, by the advent of complexity science. [52]

The production of this special issue was funded by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG, German Research Foundation)—project number 374277577, Research Network Mixed Methods and Multimethod Social Research.

1) The terms multimethod and mixed methods are used with a variety of different meanings and applications (ANGUERA, BLANCO-VILLASEÑOR, LOSADA, SÁNCHEZ-ALGARRA & ONWUEGBUZIE, 2018). In one rather common conceptualization the term multimethod research is taken to describe any combination of (qualitative and/or quantitative) empirical methods of data collection or analysis, while the term mixed methods is used to specifically refer to the integration of qualitative and quantitative approaches (FETTERS & MOLINA-AZORIN, 2017). We find this distinction to be useful, however, acknowledging the inconsistent use of both terms as well as the fuzziness of the qualitative/quantitative distinction, we also use the acronym MMMR (mixed-methods and multimethod research) to refer to the field of method integration in general (HESSE-BIBER, 2015). <back>

2) Data retrieved on October 26, 2022. Search query: "mixed method*" OR multimethod* OR multi-method* OR triangulat* (where "..." indicates a specific phrase, and * includes any possible extensions of a term). Average number of database entries per year: Scopus=2.657.334; SocINDEX=70.932. We acknowledge that these are very rough numbers, and they are far from a reliable estimate of the actual prevalence of MMMR-related publications. <back>

3) It is important to note that the inclusion of distinct qualitative and quantitative data is far from being universally accepted as a necessary criterion for categorizing a mixed methods design. For example, conversion or transformation designs, in which data are transformed from one type into another, e.g., when quantitizing initially qualitative material during content analysis, are frequently referred to as mixed methods designs (SCHOONENBOOM, 2023; SCHREIER, 2012). <back>

4) A current example of a project in which researchers are working towards a more inclusive international peer-learning process with regard to MMMR methodology, specifically within the area of spatial and urban sociology, is the Global Center of Spatial Methods for Urban Sustainability. <back>

Akremi, Leila & Zanker, Dagmar (2023). Mixing standardized administrative data and survey data with qualitative content analysis in longitudinal designs: Perceptions of justified pensions and related life courses. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung / Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 24(1), Art. 16, https://doi.org/10.17169/fqs-24.1.4003.

Alise, Mark A. (2008). Disciplinary differences in preferred research methods: a comparison of groups in the Biglan classification scheme. Dissertation, Department of Educational Theory, Policy, and Practice, Louisiana State University, Baton Rouge, LA, US, https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations/2052 [Accessed: August 8, 2022].

Alise, Mark A. & Teddlie, Charles (2010). A continuation of the paradigm wars? Prevalence rates of methodological approaches across the social/behavioral sciences. Journal of Mixed Methods Research, 4(2), 103-126.

Anandarajan, Murugan; Hill, Chelsey & Nolan, Thomas (2019). Practical text analytics: Maximizing the value of text data. Cham: Springer.

Anguera, M. Teresa; Blanco-Villaseñor, Angel; Losada, José L.; Sánchez-Algarra, Pedro & Onwuegbuzie, Anthony J. (2018). Revisiting the difference between mixed methods and multimethods: Is it all in the name?. Quality & Quantity, 52(6), 2757-2770.

Bagele, Chilisa (2020). Indigenous research methodologies. Los Angeles, CA: Sage.

Bash, Kirstie L.; Howell Smith, Michelle C.; & Trantham, Pam S. (2021). A systematic methodological review of hierarchical linear modeling in mixed methods research. Journal of Mixed Methods Research, 15(2), 190-211.

Baur, Nina, & Hering, Linda (2017). Die Kombination von ethnografischer Beobachtung und standardisierter Befragung. Kölner Zeitschrift für Soziologie und Sozialpsychologie, 69(Supplement 2), 387-414.

Baur, Nina; Kelle, Udo & Kuckartz, Udo (Eds.) (2017). Mixed Methods. Kölner Zeitschrift für Soziologie und Sozialpsychologie, 69(Supplement 2).

Bergman, Max M. (Ed.) (2008). Advances in mixed methods research: Theories and applications. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Blaikie, Norman (2007). Approaches to social enquiry: Advancing knowledge. Cambridge: Polity.

Brewer, John & Hunter, Albert (2006). Foundations of multimethod research: Synthesizing styles. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Bryman, Alan (2006). Integrating quantitative and qualitative research: How is it done?. Qualitative Research, 6(1), 97-113.

Burzan, Nicole (2016). Methodenplurale Forschung. Chancen und Probleme von Mixed Methods. Weinheim: Beltz Juventa.

Campbell, Donald & Fiske, Donald (1959). Convergent and discriminant validation by the multitrait-multimethod-matrix. Psychological Bulletin, 56(2), 81-105.

Coates, Adam (2021). The prevalence of philosophical assumptions described in mixed methods research in education. Journal of Mixed Methods Research, 15(2), 171-189.

Cram, Fiona & Mertens, Donna M. (2015). Transformative and indigenous frameworks for multimethod and mixed methods research. In Sharlene Hesse-Biber & R. Burke Johnson (Eds.), The Oxford handbook of multimethod and mixed methods research inquiry (pp.91-109). New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

Creswell, John W. & Plano Clark, Vicki L. (2017 [2011]). Designing and conducting mixed methods research. Los Angeles, CA: Sage.

Cupchik, Gerald (2001). Constructivist realism: An ontology that encompasses positivist and constructivist approaches to the social sciences. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung / Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 2(1), Art. 7, https://doi.org/10.17169/fqs-2.1.968 [Accessed: October 26, 2022].

Denzin, Norman K. (1978). The research act. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill.

Eickelmann, Jennifer & Burzan, Nicole (2023). Challenges of multimethod and mixed methods designs in museum research. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung / Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 24(1), Art. 12, https://doi.org/10.17169/fqs-24.1.3988.

Fetters, Michael D. & Molina-Azorin, José F. (2017). The Journal of Mixed Methods Research starts a new decade: Principles for bringing in the new and divesting of the old language of the field. Journal of Mixed Methods Research, 11(1), 3-10.

Fielding, Nigel (2009). Going out on a limb: Postmodernism and multiple method research. Current Sociology, 57(3), 427-447.

Fielding, Nigel (2010a). Elephants, gold standards and applied qualitative research. Qualitative Research, 10(1), 123-127.

Fielding, Nigel (2010b). Mixed methods research in the real world. International Journal of Social Research Methodology, 13(2), 127-138.

Fielding, Nigel & Schreier, Margrit (2001). Introduction: On the compatibility between qualitative and quantitative research methods. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung / Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 2(1), Art. 4, https://doi.org/10.17169/fqs-2.1.965 [Accessed: July 13, 2022].

Flick, Uwe (2011). Triangulation. Eine Einführung. Berlin: Springer VS.

Flick, Uwe (2017). Mantras and myths: The disenchantment of mixed-methods research and revisiting triangulation as a perspective. Qualitative Inquiry, 23(1), 46-57.

Gallie, Walter B. (1956). Essentially contested concepts. Proceedings of the Aristotelian Society, 56, 167-198.

Giddings, Lynne S. (2006). Mixed-methods research: Positivism dressed in drag?. Journal of Research in Nursing, 11(3), 195-203.

Gläser-Zikuda, Michaela; Seidel, Tina; Rohlfs, Carsten; Gröschner, Alexander & Ziegelbauer, Sascha (Eds.) (2012). Mixed methods in der empirischen Bildungsforschung. Münster: Waxmann.

Gobo, Giampietro (2023). Mixed methods and their pragmatic approach: Is there a risk of being entangled in a positivist epistemology and methodology? Limits, pitfalls and consequences of a bricolage methodology. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung / Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 24(1), Art. 13, https://doi.org/10.17169/fqs-24.1.4005.

Gobo, Giampietro; Fielding, Nigel; La Rocca, Gevisa; van der Vaart, Wander (Eds.) (2021). Merged methods: A rationale for full integration. London: Sage.

Goertz, Gary (2017). Multimethod research, causal mechanisms, and case studies. An integrated approach. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Goertz, Gary & Mahoney, James (2012). A tale of two cultures. Qualitative and quantitative research in the social sciences. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Greene, Jennifer C. (2007). Mixed methods in social inquiry. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Greene, Jennifer C. (2008). Is mixed methods social inquiry a distinctive methodology?. Journal of Mixed Methods Research, 2(1), 7-22.

Greene, Jennifer C. (2010). Foreword. Beginning the conversation. International Journal of Multiple Research Approaches, 4(1), 2-5.

Guba, Egon G. & Lincoln, Yvonna S. (1994). Competing paradigms in qualitative research. In Norman K. Denzin & Yvonna S. Lincoln (Eds.), Handbook of qualitative research (pp.105-117). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Guetterman, Timothy C.; Babchuk, Wayne A.; Howell Smith, Michelle C. & Stevens, Jared (2019). Contemporary approaches to mixed methods-grounded theory research: A field-based analysis. Journal of Mixed Methods Research, 13(2), 179-195.

Gutierrez Sanin, Francisco (2001). Imitation games and political discourse. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung / Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 2(1), Art. 10, https://doi.org/10.17169/fqs-2.1.971 [Accessed: October 26, 2022].

Hammersley, Martyn (2002). The relationship between qualitative and quantitative research: Paradigm loyalty versus methodological eclecticism. In John T. Richardson (Ed.), Handbook of qualitative research methods for psychology and the social sciences (pp.159-174), Malden, MA: Blackwell.

Hammersley, Martyn (2008). Paradigm war revived? On the diagnosis of resistance to randomized controlled trials and systematic review in education. International Journal of Research & Method in Education, 31(1), 3-10.

Hammersley, Martyn (2018). Commentary—On the "indistinguishability thesis": A response to Morgan. Journal of Mixed Methods Research, 12(3), 256-261.

Hammersley, Martyn (2023). Are there assessment criteria for qualitative findings? A challenge facing mixed methods research. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung / Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 24(1), Art. 1, https://doi.org/10.17169/fqs-24.1.3935.

Hense, Andrea (2023). Combining graphic elicitation methods and narrative family interviews in a qualitative multimethod design. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung / Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 24(1), Art. 6, https://doi.org/10.17169/fqs-24.1.3970.

Hesse-Biber, Sharlene (2012). Feminist approaches to triangulation. Journal of Mixed Methods Research, 6(2), 137-146.

Hesse-Biber, Sharlene (2015). Introduction: navigating a turbulent research landscape: working the boundaries, tensions, diversity, and contradictions of multimethod and mixed methods inquiry. In Sharlene Hesse-Biber & R. Burke Johnson (Eds.), The Oxford handbook of multimethod and mixed methods research inquiry (pp.xxxiii-liii). New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

Hesse-Biber, Sharlene & Johnson, R. Burke (Eds.) (2015). The Oxford handbook of multimethod and mixed methods research inquiry. New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

Hirschauer, Stefan & Völkle, Laura (2017). Denn sie wissen nicht, was sie lehren. "Empirische Sozialforschung" als Etikettenschwindel. Soziologie, 46(4), 417-428.

Hollstein, Betina & Wagemann, Claudius (2014). Fuzzy-set analysis of network data as mixed method: Personal networks and the transition from school to work. In Silvia Domínguez & Betina Hollstein (Eds.), Mixed methods social networks research. Design and applications (pp.237-268), New York, NY: Cambridge University Press.

Howe, Kenneth R. (2004). A critique of experimentalism. Qualitative Inquiry, 10(1), 42-61.

Howell Smith, Michelle C. & Shanahan Bazis, Pamela (2021). Conducting mixed methods research systematic methodological reviews: A review of practice and recommendations. Journal of Mixed Methods Research, 15(4), 546-566.

Hunter, Albert & Brewer, John D. (2015). Designing multimethod research. In Sharlene Hesse-Biber & R. Burke Johnson (Eds.), The Oxford handbook of multimethod and mixed methods research inquiry (pp.185-205). New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

Hutchinson, Susan R. & Lovell, Cheryl D. (2004). A review of methodological characteristics of research published in key journals in higher education: Implications for graduate research training. Research in Higher Education, 45(4), 383-403.

Janetzko, Dietmar (2001). Processing raw data both the qualitative and quantitative way. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung / Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 2(1), Art. 11, https://doi.org/10.17169/fqs-2.1.972 [Accessed: October 26, 2022].

Johnson, R. Burke (2017). Dialectical pluralism: A metaparadigm whose time has come. Journal of Mixed Methods Research, 11(2), 156-173.

Kansteiner, Katja & König, Stefan (2020). The role(s) of qualitative content analysis in mixed methods research designs. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung / Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 21(1), Art. 11, http://dx.doi.org/10.17169/fqs-21.1.3412 [Accessed: June 30, 2022].

Kelle, Udo (2001). Sociological explanations between micro and macro and the integration of qualitative and quantitative methods. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung / Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 2(1), Art. 5, https://doi.org/10.17169/fqs-2.1.966 [Accessed: October 26, 2022].

Kelle, Udo (2008). Die Integration qualitativer und quantitativer Methoden in der empirischen Sozialforschung: Theoretische Grundlagen und methodologische Konzepte. Wiesbaden: VS Verlag für Sozialwisseschaften.

Kelle, Udo & Reith, Florian (2023). Strangers in paradigms!? Alternatives to paradigm-bound methodology and "methodological confessionalism"'. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung / Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 24(1), Art. 20, http://dx.doi.org/10.17169/fqs-24.1.4015.

Kleining, Gerhard & Witt, Harald (2001). Discovery as basic methodology of qualitative and quantitative research. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung / Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 2(1), Art. 16, https://doi.org/10.17169/fqs-2.1.977 [Accessed: October 26, 2022].

Knappertsbusch, Felix (2020). ''Fractal heuristics'' for mixed methods research: Applying Abbott's ''fractal distinctions'' as a conceptual metaphor for method integration. Journal of Mixed Methods Research, 14(4), 456-472.

Knappertsbusch, Felix (2023). From paradigm wars to peaceful coexistence? A sociological perspective on the qualitative-quantitative-divide and future directions for mixed methods methodology. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung / Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 24(1), Art. 2, https://doi.org/10.17169/fqs-24.1.3966.

Kuckartz, Udo (2014). Mixed Methods. Methodologie, Forschungsdesigns und Analyseverfahren. Wiesbaden: Springer VS.

Kuiken, Don & Miall, David S. (2001). Numerically aided phenomenology: Procedures for investigating categories of experience. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung / Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 2(1), Art. 15, https://doi.org/10.17169/fqs-2.1.976 [Accessed: October 26, 2022].

La Rocca, Gevisa (2020). Possible selves of a hashtag: Moving from the theory of speech acts to cultural objects to interpret hashtags, International Journal of Sociology and Anthropology, 12(1), 1-9.

Lincoln, Yvonna S. & Guba, Egon G. (1985). Naturalistic inquiry. Beverly Hills, CA: Sage.

Lincoln, Yvonna S.; Lynham, Susan H. & Guba, Egon G. (2011). Paradigmatic controversies, contradictions, and emerging confluences, revisited. In Norman K. Denzin & Yvonna S. Lincoln (Eds.), The Sage handbook of qualitative research (pp.97-128). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

MacCannell, Dean (1992). Empty meeting grounds. The tourist papers. London: Routledge.

Marcus, George E. (1995). Ethnography in/of the world system: The emergence of multi-sited ethnography, Annual Review of Anthropology, 24, 95-117.

Mayring, Philipp (2001). Kombination und Integration qualitativer und quantitativer Analyse. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung / Forum Qualitative Social Research, 2(1), Art. 6, https://doi.org/10.17169/fqs-2.1.967 [Accessed: October 26, 2022].

Mayring, Philipp (2012). Qualitative Inhaltsanalyse. Ein Beispiel für Mixed Methods. In Michaela Gläser-Zikuda, Tina Seidel, Carsten Rohlfs, Alexander Gröschner & Sascha Ziegelbauer (Eds.), Mixed Methods in der empirischen Bildungsforschung (pp.27-36). Münster: Waxmann.

Maxwell, Joseph A. (2011). Paradigms or toolkits? Philosophical and methodological positions as heuristics for mixed methods research. Mid-Western Educational Researcher, 24(2), 25-30.

Maxwell, Joseph A. (2016). Expanding the history and range of mixed methods research. Journal of Mixed Methods Research, 10(1), 12-27.

Maxwell, Joseph A. (2018). The ''silo problem'' in mixed methods research. International Journal of Multiple Research Approaches, 10(1), 317-327.

Maxwell, Joseph A. (2019). Distinguishing between quantitative and qualitative research: A response to Morgan. Journal of Mixed Methods Research, 13(2), 132-137.

Mejeh, Mathias; Hagenauer, Gerda & Gläser-Zikuda, Michaela (2023). Mixed methods research on learning and instruction—meeting the challenges of multiple perspectives and levels within a complex field. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung / Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 24(1), Art. 14, https://doi.org/10.17169/fqs-24.1.3989.

Mertens, Donna M. (2010). Transformative mixed methods research. Qualitative Inquiry, 16(6), 469-474.

Mertens, Donna M.; Bazeley, Pat; Bowleg, Lisa; Fielding, Nigel; Maxwell, Joseph; Molina-Azorin, Jose F. & Niglas, Katrin (2017). Expanding thinking through a kaleidoscopic look into the future: Implications of the Mixed Methods International Research Association's task force report on the future of mixed methods. Journal of Mixed Methods Research, 10(3), 221-227.

Morgan, David L. (2018). Living with blurry boundaries: The value of distinguishing between quantitative and qualitative research. Journal of Mixed Methods Research, 12(3), 268-279.

Morgan, David L. (2019). Commentary—after triangulation, what next?. Journal of Mixed Methods Research, 13(1), 6-11.

Morse, Janice & Niehaus, Linda (2009). Mixed method design: Principles and procedures. London: Routledge.

Münch, Richard (2018). Soziologie in der Identitätskrise: Zwischen totaler Fragmentierung und Einparadigmenherrschaft. Zeitschrift für Soziologie, 47(1), 1-6.

Munoz-Najar Galvez, Sebastian; Heiberger, Raphael & McFarland, Daniel (2020). Paradigm wars revisited: A cartography of graduate research in the field of education (1980-2010). American Educational Research Journal, 57(2), 612-652.

Niglas, Katrin (2004). The combined use of qualitative and quantitative methods in educational research. Dissertation, Faculty of Educational Sciences, Tallinn Paedagogical University, Estonia, https://www.digar.ee/arhiiv/en/download/193063 [Accessed: June 30, 2022].

Novello, Noemi (2023). Communities of scholars and mixed methods research: Relationships among fields and researchers. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung / Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 24(1), Art. 19, http://dx.doi.org/10.17169/fqs-24.1.4008.

O'Cathain, Alicia; Murphy, Elizabeth & Nicholl, Jon (2007). Why, and how, mixed methods research is undertaken in health services research in England: A mixed methods study. BMC Health Services Research, 7, Art. 85, https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-6963-7-85 [Accessed: June 30, 2022].

Odağ, Özen & Mittelstädt, Alexandra (2023). Mixed methods in research on the psychology of the internet and social media (POISM). Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung / Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 24(1), Art. 18, http://dx.doi.org/10.17169/fqs-24.1.4009.

Payne, Geoff; Williams, Malcolm & Chamberlain, Suzanne (2004). Methodological pluralism in British sociology. Sociology, 38(1), 153-163.

Pivovarova, Margarita; Powers, Jeanne M. & Fischman, Gustavo E. (2020). Moving beyond the paradigm wars: Emergent approaches for education research. Review of Research in Education, 44(1), vii-xvi.

Plano Clark, Vicki L. (2010). The adoption and practice of mixed methods. U.S. trends in federally funded health-related research. Qualitative Inquiry, 16(6), 428-440.

Plano Clark, Vicki L. & Ivankova, Nataliya V. (2016). Mixed methods research. A guide to the field. Los Angeles, CA: Sage.

Römer, Oliver (2019). Wissenschaftslogik und Widerspruch. Die Esser-Hirschauer-Kontroverse. Soziologiehistorische und systematische Überlegungen zu einem "Methodenstreit". Zeitschrift für Theoretische Soziologie, 8(2), 220-244.

Ryan, Anne & Gobo, Giampietro (2011). Managing the decline of globalized methodology. International Journal of Social Research Methodology, 14(6), 411-415.

Schmitt, Annette; Mees, Ulrich & Laucken, Uwe (2001). Logographische Analyse sozial prozessierender Texte. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung / Forum Qualitative Social Research, 2(1), Art. 14, https://doi.org/10.17169/fqs-2.1.975 [Accessed: October 26, 2022].

Schneider, Carsten Q. & Rohlfing, Ingo (2013). Combining QCA and process tracing in set-theoretic multi-method research. Sociological Methods & Research, 42(4), 559-597.