Volume 24, No. 2, Art. 5 – May 2023

Pediatric Nurses in Early Childhood Intervention in Germany—Emergence of a New Professional Role: Situational Analysis and Mapping

Birte Kimmerle, Friederike zu Sayn-Wittgenstein & Ursula Offenberger

Abstract: In this essay, we show how an arena is created and how a new field of work for pediatric nursing emerges from it. The situation of pediatric nurses in early childhood intervention in Germany is presented, considering related social worlds and discourses as well as historical, social, and political processes. Based on a study using interview data of pediatric nurses, text documents and field notes, we demonstrate how components of the theory/methods package of situational analysis can be used to analyze the genesis of a specialized professional group in its embeddedness in an arena. In particular, the concepts of social worlds/arenas theory and the concept of processual ordering are applied. Mapping strategies are harnessed to structure discourse material in order to show the positioning of different elements in the arena and to discuss them in their interrelation and against the background of current developments in the nursing profession.

Key words: situational analysis; social worlds/arenas; processual ordering; positional maps; early childhood intervention; nursing profession; pediatric nurses

Table of Contents

1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1 Study design and data corpus

2.2 Reflexivity

3. How Pediatric Nurses Came Into Play

4. Processual Ordering in the Arena

4.1 FGKiKP in confrontation with other professionals

4.2 Risk, prevention and responsibility: How discourses co-constituted the arena of Frühe Hilfen

4.2.1 Discourse of orientation towards risk or resource

4.2.2 Discourse of prevention and intervention

4.2.3 Discourse about public versus private responsibility for parenting

4.3 Related positions

5. Discussion and Conclusion

Does early childhood set the course for the rest of life? This was the central question of a conference of the Nationales Zentrum Frühe Hilfen [National Center for Early Prevention] (NZFH, 2015). Health-related effects of adverse childhood experiences were investigated in long-term studies: The more stressors in childhood, the higher the risk for illness and long-term health consequences in adulthood (EGLE et al., 2016). Responsibility for healthy childhood has become an important societal value and child protection constitutes a framework of action for society as a whole (HORCHER-METZGER, 2021). What does this imply for preventive services for young families? In this paper, we explore how a new professional role in the field of pediatric nursing emerged in the context of early childhood intervention. [1]

Pediatric nurses with a specific additional qualification to support families with newborns, infants and young children through home visits are referred to as Familien-Gesundheits- und Kinderkrankenpflegerinnen [family, health, and pediatric nurses] (FGKiKP)1) in Germany. This professional role and the outreach health service provided, called Frühe Hilfen, developed in conjunction with one another. The term Frühe Hilfen was established in the context of a federal program for early childhood intervention (NZFH, 2018a). Because direct translations of Frühe Hilfen—either early childhood intervention or early prevention—bear different connotations in English, we will proceed using the German term in this essay. [2]

In an ongoing research enquiry, which is the PhD work of Birte KIMMERLE under the supervision of Ursula OFFENBERGER and Friederike ZU SAYN-WITTGENSTEIN and which was approved by the Ethics Committee, Witten/Herdecke University (N°147/2016), we are particularly interested in the following questions: How does this new professional role emerge? How do pediatric nurses fit into this new field of work? What is specific about their activities? Subsequently, we will discuss the results against the backdrop of current transformations in the nursing profession (KIMMERLE, OFFENBERGER & ZU SAYN-WITTGENSTEIN, 2020). [3]

Starting from a known outcome—FGKiKP having emerged—we pressed the rewind button and looked at the bigger picture: What led to the development of the arena of Frühe Hilfen and how did it start? At the beginning of the millennium, the Bundesministerium für Familie, Senioren, Frauen und Jugend [Federal Ministry for Family Affairs, Senior Citizens] (BMFSFJ) issued a "Nationaler Aktionsplan: Für ein kindgerechtes Deutschland 2005-2010" [National Action Plan: Germany Fit for Children (2005-2010)] and declared a healthy and violence-free upbringing a political goal (BMFSFJ, 2006a). Violence through neglect was recognized as a problem and was to be scientifically investigated. Children were to be taken into account in all policies. As a first step toward this goal, the Kinder- und Jugendhilfeweiterentwicklungsgesetz [Child and Youth Welfare Development Act] (KICK) came into force in 2005 with the aim of improving the protection of children and young people. The Minister for Family Affairs was a strong advocate for healthy childhood and children's rights. One of her primary concerns was to improve the protection of children from violence. [4]

In 2006, a scandal occurred: A child died as a result of injuries and neglect, despite the family having been looked after by the youth welfare office and the child having been under state protection. The tragedy was much discussed in the media: The death of this child was seen as proof of the failure of the child protection system; authority figures were pilloried, and culprits were sought. Due to this issue, the discourse on child welfare and child protection was accelerated and the debate about public versus private responsibility for parenting was further incited. As a result, sections of the public called into question the role of state agencies such as the youth welfare office. [5]

The Minister for Family Affairs at the time decided to learn from these mistakes (BMFSFJ, 2008) and to do an even better job of ensuring that "no child falls through the cracks" (RENNER, 2012, p.1). She wanted to improve the coordination of the efforts of the different actors and launched a nationwide campaign: "Early help for parents and children and social early warning systems" (BMFSFJ, 2007, p.1). Against this background, Frühe Hilfen is first and foremost an initiative to prevent risks to the welfare of children, to identify these risks at an early stage and to build up an institutional warning system. It was during this era that the arena of Frühe Hilfen was born. [6]

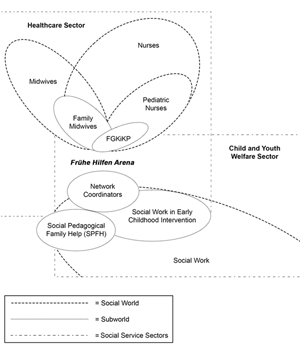

Within the framework of Frühe Hilfen, multi-professional, interdisciplinary networks with coordinated support services for vulnerable families with psychosocial and healthcare needs were established (NZFH, 2018a). One component is the long-term home visiting service offered by healthcare professionals, internationally comparable with early childhood intervention programs or home visiting programs. By providing this service, FGKiKP have been advocating for a healthy start in life and strengthening families for more than ten years (PAUL, BACKES, RENNER & SCHARMANSKI, 2018). They perform the same services as family midwives and other specific services2) and give targeted, non-stigmatizing support to families in need who are experiencing difficulties in bringing up their children. The family-oriented additional qualification for pediatric nurses was specifically designed for the work in Frühe Hilfen and is equivalent to the qualification of a family midwife (NZFH, 2014). In this way, the stage was set for creating a new field of work for healthcare professionals. [7]

The aim of this article is to show the use of theories and methods of situational analysis in operation. We would also like to present preliminary results about pediatric nurses in a new professional role in Germany. In the next section the research design and the empirical foundation for our research inquiry is presented (Section 2). A subsection is devoted to the topic of reflexivity, because subjectivity plays an important role in the research constellation. In the following sections, results from the analysis are explained: First, we present how FGKiKP emerged from the arena, creating a new field of work for pediatric nurses (Section 3). A map is used to explain the relations of FGKiKP to other social worlds and their processual ordering in the arena (Section 4). Three central discourses involved in constituting the arena are first presented in summary form. Then, we zoom into one of these discourses and evaluate the different positions with the help of a positional map. Finally, the discussion of the results, including reflections on the methodological procedure, is followed by concluding remarks (Section 5). [8]

2.1 Study design and data corpus

A fundamental component of the methodological approach is the concept of situation. In line with Adele CLARKE (2005), Kathy CHARMAZ (2014 2006]) pointed out that the logical extension of the constructivist approach means learning "how, when, and to what extent the studied experience is embedded in larger and, often, hidden structures, networks, situations, and relationships" (p.240). Thus, the concept of situation was expanded in the course of the enquiry, in order to enable a better understanding of how the situation of FGKiKP has become the way it is, which elements play a role, how, and by whom or what the situation is shaped. The situation is understood as a relational structure, including everything that is made relevant by the interactions that take place (CLARKE, FRIESE & WASHBURN, 2018, p.46). Hence, the question was raised as to what (co-)constitutes the situation of FGKiKP (KIMMERLE et al., 2020). [9]

CLARKE et al. (2018) wanted to "reground grounded theory after the interpretive turns" (p.61) and assembled the theory-methods package of situational analysis. They drew from the situation-centered social worlds and arenas approach, which can be traced back to the Chicago School, particularly Anselm STRAUSS (1978a, 1978b, 1978c). The arena is the meeting point for social worlds, bringing them into contact and relation (STRAUSS, 1993, p.215). In arenas, "various issues are debated, negotiated, fought out, forced and manipulated by representatives" of social worlds or subworlds (STRAUSS, 1978c, p.124). CLARKE (2005) combined social worlds/arenas theory with a poststructuralist and postmodernist starting point: Boundaries are perceived as being fluid and porous, negotiations are fluid, discourses are multi-layered and often contradictory. Moreover, issues such as power and inequality did not play a major role in the work of STRAUSS (STRÜBING, 2014 [2004]), but were explicitly referred to by CLARKE (2019) and her anchoring in, e.g., "feminist epistemology, critique of science, and inequality studies3)" (OFFENBERGER, 2019, §7), with which she enriched grounded theory methodology. Situational analysis is based on three "new grounds" (CLARKE et al., 2018, p.77):

CLARKE suggested how concepts of Michel FOUCAULT—especially his concept of discourses—can be integrated into a grounded theory (KELLER, 2008). If, according to FOUCAULT (2020 [1966]), individuals and collectives are constituted by discourses: Which discourses play a role in the constitution of the situation of FGKiKP?

CLARKE et al. (2018, pp.85ff.) drew attention to materiality and explicit consideration of the non-human as powerful elements of the situation. In doing so, they referred to actor-network theory (LATOUR, 2010 [2007]), but also to the importance of things in pragmatism and interactionism, e.g., in FOUCAULT (2020 [1966]). In this inquiry, the baby scale is one example that serves as a door opener for FGKiKP, making it a powerful actant. The key is to recognize how things are related (CLARKE et al., 2018, p.86).

As a third "new ground," in the new edition of the situational analysis, CLARKE et al. (pp.63ff.) referred to assemblage theory. An assumption in assemblage theory is that the relationships between different entities are not stable and fixed, but can be shifted and replaced. [10]

CLARKE (2005) thus placed the situation at the center of analyses rather than the action, as STRAUSS did. Mapping strategies are a tool to set different foci in an analysis. On the one hand, the maps are a tool that, like the wide-angle lens in photography, helps to get a bigger picture (CLARKE et al., 2018, p.117). On the other hand, individual facets, for example certain discourses, can be singled out or zoomed in upon. Related to the research inquiry, the focus of analysis lies (pp.16ff.):

on the ecology of relationships that exist between different elements of a situation: What does—which elements do—matter for the situation of FGKiKP? How can the view be broadened? For this step of analysis, CLARKE et al. (pp.127ff.) suggested situational maps as a tool.

on different social groups that come together in the situation: How does FGKiKP relate to other groups of actors in Frühe Hilfen networks? How do FGKiKP negotiate and shape the situation? For this step of analysis, CLARKE et al. (pp.147ff.) suggested social worlds/arenas maps.

on discourses in the situation under study: How and from which situation did Frühe Hilfen develop in Germany? In which discourses did the field of work and the professional role emerge in the first place? For this purpose, CLARKE et al. (pp.165ff.) proposed positional maps as a tool for analysis. [11]

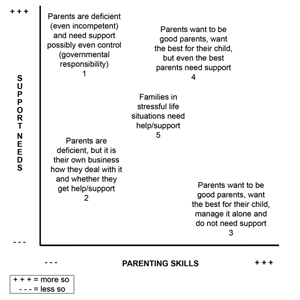

Several specific forms of empirical data inquiry were carried out. Seven problem-centered interviews (WITZEL, 2000; WITZEL & REITER, 2012) with an occupational biographical open-ended narrative impulse were conducted with FGKiKP by KIMMERLE between February 2016 and March 2018. In February 2018, KIMMERLE also chaired a group discussion (BOHNSACK, 2002). A total of ten FGKiKP participated in the study. A supplementary interview with a family midwife and a provider of further training for qualification as a family midwife or FGKiKP followed in March 2018. All interviews lasted between two and three hours, which implies that study participants had ample opportunity to unfold their constructs and communicative rule system. The interviews were recorded, transcribed verbatim in full by KIMMERLE and pseudonymized. Artifacts or actors that were made relevant in the survey situation were included in the analyses, e.g., the "child protection questionnaire" (a survey instrument for assessing the family situation), the sleeping bag (as a welcome gift for young families) or documentation instruments. Job advertisements and job descriptions were also included as material as soon as study participants referred to them. Moreover, data sources included field notes collected by KIMMERLE at congresses and after exchanges with pediatric nurses, nursing students, from the early 2000s to 2020. To unravel the emergence of the arena and the new professional role, we wanted to trace the main lines of development and the social, political, and cultural backgrounds: Thus, we analyzed papers, chronicles and excerpts on these developments and political decisions. These included documents of political programs and initiatives for the development of Frühe Hilfen, programmatic texts for the design of Frühe Hilfen such as the "Mission Statement Early Childhood Intervention" (NZFH, 2018a) and basic documents for the qualification as a FGKiKP or family midwife (e.g., NZFH, 2016-2018) as well as campaigns to publicize the offer of early childhood intervention and documentation of events, symposia and congresses in the context of Frühe Hilfen. [12]

Data management in the analysis process was supported by qualitative data analysis (QDA) software. According to CLARKE et al. (2018, p.108) grounded theory methodology and situational analysis procedures can both be applied in the same larger project. However, they suggested not to mix the two analysis procedures, but to conduct them separately. Therefore, two projects were created in the QDA program: One with the empirical data from the interviews and a second with the extensive discourse material. The interviews were analyzed according to the principles of grounded theory methodology: coding procedures, contrastive comparison, theoretical saturation, memo writing (CORBIN & STRAUSS, 2015 [1990]). In the second project, 274 documents that were considered groundbreaking for the development of the arena Frühe Hilfen and the emergence of the professional orientation FGKiKP were filed. Then, situational, relational, and positional maps for different discourse material were created, recreated and compared to reconstruct these developments (for more examples see also KIMMERLE et al., 2020). [13]

KIMMERLE is a pediatric nurse and has long been interested in the field of outreach, early help and health promotion for families with newborns and young children. For 20 years—practically her entire professional life from being a nurse to a PhD student—she has been following developments and collecting data on how this field of work for nurses is evolving and emerging. Thus, she is connected to her research field in many ways, being a pediatric nurse who identifies with the profession and conducting research in her own field. So, the subjectivity in this research cannot be removed, but we will reflect sharply on the parts of this research that may be subjective. In this way, the duality as a researcher may transform from a limitation into a benefit. CLARKE et al. (2018) considered own experience as a data source: "Researchers should use their own experience of the phenomenon under study and of doing the research as one among many data sources" (p.107), e.g., to create maps. To ensure reflexivity, we think it is doubly important to join together in research workshops and also include perspectives and input from other researchers on our own topic. This is also important with regard to data collection and theoretical sampling, in order to illuminate dark corners or to recognize the "gorillas sitting around" (p.120). This requirement was addressed in this research by attending regular research workshops, methodological workshops, and conferences such as the bilingual conference on social worlds, arenas, and situational analysis in preparation for this publication. [14]

As part of the professional group, it was easy to gain access to the research field. As a lecturer in the context of the additional qualification as a FGKiKP as well as at congresses in the context of early childhood intervention, the first author was in the middle of it all and part of the action. Therefore, it was challenging to create analytical distance. As a pediatric nurse, she was not unaffected by the way the profession was portrayed or marginalized in public. Even basic documents mentioned the profession only implicitly as a "professional group comparable to family midwives" (e.g., AYERLE, CZINZOLL & BEHRENS, 2012; NZFH, 2018b). To find out how this could happen, we decided to unravel the logic of the field in its formation. In the next section, we put a focus on the emergence of FGKiKP and compare this specialized professional role to pediatric nursing. [15]

3. How Pediatric Nurses Came Into Play

Through the arena of Frühe Hilfen, a field of work for pediatric nurses was newly produced. The FGKiKP role with its specifics and new features was developed against the background of problems with high social relevance, namely child welfare endangerment and families with cumulative distress or who are in high-stress situations. The state was considered responsible for a healthy and violence-free childhood and all families were to be reached with its support and assistance services to strengthen parenting skills. Competent and qualified professionals were needed, in particular for multiple coinciding problems or even emergencies that affect one or both parents and the child. In addition, there was another challenge—an interface problem: On the one hand, accessing help from a single source was presented as the ideal; on the other hand, this requirement met fragmented responsibilities in different social service sectors. These problems were countered first by forming networks and interdisciplinary cooperation. Secondly, home visiting programs were established according to the international model, where qualified healthcare professionals were to ensure better health in the families. Therefore, qualified specialists were needed in the area of maternal health, child health, development, and nutrition, and on the daily life of families. Recognizing and assessing risk factors also required professional qualification (BMFSFJ, 2006b). The key question at this initial stage was: Who can do this? Who can take action here? Who can act in this field between help and control? The premises were to establish strong networks for children and parents, to support children from the very beginning and to qualify professionals (BMFSFJ, 2008). To qualify pediatric nurses for work with families in psychosocially difficult situations, the Berufsverband Kinderkrankenpflege Deutschland [Professional Association of Pediatric Nursing] (BeKD) designed an additional qualification for pediatric nurses to become a FGKiKP. Since 2012, they have been deployed nationwide in Frühe Hilfen networks as alternative or in addition to family midwives. We tracked the emergence of the arena Frühe Hilfen and recognized how a new field of work for pediatric nursing was produced. Given this starting point, there were also reasons from pediatric nurses' perspectives why they felt their profession was being addressed: Monitoring children's development and health and supporting families are among their core tasks. [16]

According to CLARKE, STRAUSS defined social worlds "as groups with shared commitments to certain activities [...] to achieve their goals, and building shared ideologies" and shared perspectives (CLARKE, 1991, p.131). All activities in the social world are oriented around one core activity (STRAUSS, 1978a). Thus, we asked in the analyses: What constitutes the core activity of the interviewed FGKiKP? What do they see as their core mission? [17]

The core activity of FGKiKP, towards which they orientate all of their activities, is the monitoring of children's health and development, as this example illustrates: "Once again we are placing the focus in a classic sense on the child, what their interaction behavior and their bonding behavior are like, or how the child is developing, i.e., their health development" (Participant 7). FGKiKP remain associated with the same primary activity as pediatric nurses: the monitoring of children's health and development. Additionally, we asked: Is there something different and new that forms part of the activities of FGKiKP? From the interview analyses, we concluded that the FGKiKP's main concern in monitoring health and development is to prevent illness and, above all, to promote the health of the family and a healthy upbringing of children.

"We have always made it clear that we are active in prevention, which means that we deal with the basic issues: sleeping, eating, simply everything that is necessary for children to grow up healthy, because we think that this is a health mandate" (Participant 7). [18]

FGKiKP have a stronger focus on the whole family than pediatric nurses in the hospital setting, as the following example illustrates. One participant tells of a family to which she was called because of twins who were not developing healthily. However, she then relates to what she put in place for the sibling and how the focus expanded to the whole family:

"At the end of the day it's about family support, and naturally the focus is on the infant, but you can never just look at one family member in isolation, but rather have to see the family as a whole. So when, in conversation, I see a need here or there, it can happen that I go a bit further" (Participant 3). [19]

This also includes providing psychosocial support and, in particular, supporting the parent-child relationship:

"In the family I encourage above all the mother-child relationship and interaction. These mothers, who are mentally strained, or sometimes depressed or even aggressive towards their children, are highly unsettled. I see my main task as giving them the assurance that what they are doing, they are doing well" (Participant 4). [20]

One new focus of attention in this emerging field of work is the prevention of risks to the welfare of the child. From the interviews, we analyzed that child protection is a mission of the social subworld. "Of course, in the back of my mind is always the question of child protection, and the kind of things I need to be paying attention to in that regard" (Participant 3). Child protection became the overriding guiding principle and a foundation for all actions for FGKiKP, as evidenced in all interviews. [21]

With all these additional tasks and new perspectives, FGKiKP see themselves as part of a network in which they take on the function of a pilot or guide, in the sense of an expert who has local knowledge and who is responsible for guiding or maneuvering a ship entering a harbor. This is new, compared to the activities of a pediatric nurse in the hospital:

"In a case I have now, there's a family that really just has financial troubles—debt—so they're having relationship problems, and on top of all that, their child has infant regulatory disorder—a really difficult story. And it's clear that we can't manage all of that in terms of prevention, logically. And every now and then there's a case where we become harbor pilots, and have that function perhaps for quite some time, and maybe also need to take the helm once in a while" (Participant 7). [22]

If necessary, they guide families to further support services and facilitate contact with other (healthcare) professionals in the Frühe Hilfen network. Their new role allows them to pursue activities in networking and cooperation much more than in a hospital setting. From the interviews, we conclude that, while FGKiKP pursue a broader core mission, these activities are close to the traditional mission of monitoring children's health and development. FGKiKP rely on their skills from their original professional roles. From these initial roles they take their core mission of ensuring that the child grows up in a healthy way and all their activities are focused on achieving this result. [23]

The study participants primarily present themselves as part of a pediatric nursing social world. Although this could stem from the fact that the interviewer also comes from pediatric nursing and this therefore might be a matter of establishing common ground in the conversation, the question arises: Do FGKiKP form a new subworld of pediatric nursing? Do they emerge from processes of segmentation? Segmentation and intersection are processes which STRAUSS emphasized in several of his publications (1978a, 1982a, 1982b, 2001 [1975]; see also BUCHER & STRAUSS, 1961). Social worlds typically segment into multiple worlds or intersect with others (CLARKE & STAR, 2008; STRAUSS, 1978a). These segments form subworlds (STRAUSS, 1978a, 1982b). An initial assumption was that the pediatric nurses who have the additional qualification as an FGKiKP constitute such a segment within pediatric nurses. They form a new group intersecting with family midwives. Both have the same family-oriented and psychosocial additional qualification. We took a closer look at these intersection processes to examine the positioning of FGKiKP: How do they interact? How do they exchange, negotiate or conflict with other social worlds and subworlds? We will refer to the processual ordering in the next section. [24]

4. Processual Ordering in the Arena

4.1 FGKiKP in confrontation with other professionals

According to CLARKE (1991), the emergence of arenas is an excellent starting point for grasping central social processes as they are structured because "nothing is taken for granted" (p.143). She then considered the co-construction of the arena between different social worlds—the negotiation—as "a key process, if not the fundamental process" (ibid.). The negotiated order theory of STRAUSS (1978b, 1982b), established and still used by CLARKE (2021, pp.47ff.), is another sensitizing concept for the analyses of this study. STRAUSS (1993) suggested in a later publication to rename the "concept of negotiated order" to "concept of processual ordering" to "emphasize the creative or constructive aspect of interaction" (p.254). This theoretical basis can be used to analyze how pediatric nurses negotiate their activities as pioneers in this multi-professional field of work. In their new professional role, they struggle to find their place within different professional groups. In the following section, we look at how FGKiKP relate to other social worlds that co-constitute the arena. With the help of a social worlds/arenas map (Figure 1), we show the arena Frühe Hilfen with the major social worlds and subworlds or segments identified as dominant in relation to FGKiKP. These include family midwives and social workers.

Figure 1: Social worlds/arenas map of the new professional role and institutional framework. Please click here for an enlarged version of Figure 1. [25]

The special feature of this map is that, in addition to the major social worlds, the social service sectors have been outlined as well. According to CLARKE (1991), "it is likely that the state in some form or another will continue to be a significant actor in most major arenas of social concern" (p.129), which is also the case in the Frühe Hilfen arena and is made effective in the institutional framework. Specific to the arena of Frühe Hilfen is that actors come together who belong to different social service sectors: healthcare and youth welfare. The aim of building networks is that these sectors should be interwoven more strongly, linked, and work better together. The position of FGKiKP in between leads to boundaries having to be negotiated, which can cause conflicts (GROSS, GINTER & ZELLER, 2017, p.55). This is why the health and youth welfare sectors are included in the map as institutional frameworks. [26]

FGKiKP are described as comparable to family midwives. Even in their original professions, there is an intersection area—as shown in the map—for midwives and pediatric nurses, for example, lactation consultation. In Frühe Hilfen, FGKiKP and family midwives have the same additional qualification and work in the same field of practice: the family home. Even though competing activities can lead to conflict, we saw in the interviews that the relationship is changing. In the beginning, it was strongly characterized by competition, which is in line with the phenomenon of cooperation without consensus identified by STRAUSS (1993). However, the longer the teams work together, the more negotiation processes lead to an agreement and the better the cooperation becomes. [27]

Frühe Hilfen is a field of work constituted and controlled by the welfare state. As the field belongs to youth services, FGKiKP interact with social workers. The social workers' field of practice is within youth services, and they often work as coordinators of the multidisciplinary Frühe Hilfen networks. Network coordinators appear as key actors at the core of the arena. They are the gatekeepers and define the major elements for other collective actors. The question is whether or not they function as "centers of authority" (CLARKE, 1991, p.144). In the empirical material, this is demonstrated as follows: Coordinators determine what is considered a case, whether a nurse is needed, what they must do and for how long, and then give instructions to the FGKiKP. The professional autonomy of FGKiKP is limited to the execution of these instructions. [28]

The following results can be summarized about the position of the FGKiKP in relation to other social worlds in the Frühe Hilfen arena: Given organizational, bureaucratic and legal structures severely restrict the autonomy of the professionals. The degree of heteronomy is high. FGKiKP have no professional autonomy, neither vis-à-vis state authorities nor the employing organizations. Even the immediate framework of nursing activities is subject to bureaucratic control. [29]

In the Frühe Hilfen arena each social world struggles for influence, power, and resources. FGKiKP have to negotiate on all sides. They interact with other professionals—representatives of welfare state regulations, financiers, and caregivers—as well as families of the children. The goals of their negotiations are to define the nurses' possibilities for action, specify their field of activity, and fine-tune their work objectives, procedures, conditions, individual role and boundaries within the multidisciplinary Frühe Hilfen networks. [30]

The core mission of child protection connects these social worlds with each other but can also cause confrontation. The negotiation of child welfare between different professionals is a subject of sustained contestation. FGKiKP often feel that their assessment is not taken seriously or that they are left alone, especially if authorities do not act. The question of where early risk identification ends and an acute endangerment of the child's well-being begins is answered differently by those involved. [31]

FGKiKP in Frühe Hilfen in Germany are experienced professionals with substantial expert knowledge, who are highly committed to healthy development. Despite an increased qualification profile, they often work under precarious conditions and in a relationship of great dependence on other professionals and state regulations. More professional autonomy is needed for FGKiKP to effectively enact their core mission. This depends heavily on the framework conditions surrounding the profession. Structural conditions are, in turn, negotiated—"negotiations produce structural conditions" (CLARKE, 2021, p.50). Using the perspective of social worlds in combination with negotiated order theory as sensitizing concepts help to understand how FGKiKP struggle and work hard to clarify their new professional role and to analyze the tensions they come into. These are part of controversial discourse fields. How discourses influence the formation of professional orientation is examined in more detail in the following. [32]

4.2 Risk, prevention and responsibility: How discourses co-constituted the arena of Frühe Hilfen

As we described in Sections 1-4, the arena of Frühe Hilfen—where FGKiKP are produced—is an ensemble of interconnected elements. In the last section, the analytical focus was put on social worlds with which FGKiKP interact. The negotiations that take place are shaped by discourses and in turn influence discourses. Arenas are thus sites of discourses (CLARKE et al., 2018, pp.73,148). They are among the constituent elements of the arena. We understand discourses in FOUCAULT's sense as a sequence of events—i.e., something in the making, including thoughts and utterances—to be grasped in their historical formation, in the chronology of their external relations (RUOFF, 2018 [2007], pp.110f.). Social worlds are constituted by discourses, and vice versa. In the poststructuralist sense, social ecology is a tangled interplay. A core business of social worlds is to produce and monitor discourses via negotiations and thus also to influence actions of other social worlds (CLARKE, 2005). Therefore, arenas always reveal power relations. Through the control and monitoring of discourses by social worlds, power becomes effective and visible (CLARKE et al., 2018, p.148). In this section, we will first look at dominant discourses in the Frühe Hilfen arena and then zoom into one discourse to reveal the different positionalities it contains. In the collected material, various mutually influencing discourses were reconstructed which are complexly interwoven with each other as well as with the developments of the field of work: with the constitution of the arena and with the emergence of the FGKiKP. [33]

4.2.1 Discourse of orientation towards risk or resource

A controversial field of discourse spans the paradigm of risk orientation. While children are at risk and no child should fall through the net with the approach of selective prevention, there is the paradigm of resource orientation: All children should grow up healthy with the approach of health promotion and universal prevention. In this field of tension, the federal initiative Frühe Hilfen came into being. Under the perspective of risk orientation, the goal was to identify risks as early as possible: preventive approaches. At the same time, a more resource-oriented approach was to be pursued, targeted at all children: health promotion. At the end of the 20th century, the worldwide development of health policy experienced a turning point: from a medical, risk-oriented perspective with a biomedical understanding of disease to a more holistic concept of health with the health promotion concept of the Ottawa Charter (WHO, 1986). A more differentiated view of health and illness was demanded by health, environmental and consumer movements, especially women's health and self-help movements (KABA-SCHÖNSTEIN, 2018). This led to the European strategy "health for all" (WHO, 1999). At that time, the focus was on health promotion as well as preventive and supportive health education. The child protection debate coincides with this time and thus forms a counterpoint to the resource orientation. [34]

4.2.2 Discourse of prevention and intervention

In child protection in Germany, a distinction is made between early prevention (Frühe Hilfen) and intervention-based child protection, which is also laid down in law (KINDLER, 2016; SCHONE, 2010). Frühe Hilfen is about the early identification of risks to well-being, development, and health. Intervention-based child protection aims at interfering without delay when there are strong indications that a child is at imminent risk of harm. Frühe Hilfen includes primary and secondary prevention services with measures being based on trust and voluntariness. In contrast, tertiary preventative measures are initiated by virtue of the state's protection mandate in situations of imminent danger to the child. The exercise of these measures does not rely on cooperation on the part of the parent or guardian, who may, if necessary, be compelled to comply. But where does early detection of potential danger end and an acute risk to well-being begin? There is a gray area between imminent danger and risk of danger and between help and control, between preventive help concepts and intervention-based child protection measures. This gray area may lead to tension and is interactively negotiated between the different social worlds in the Frühe Hilfen arena. [35]

4.2.3 Discourse about public versus private responsibility for parenting

The understanding and meaning of childhood, parenthood and family has undergone transformations over time and is interwoven with processes of social change, e.g., changing gender relations since industrialization (HORCHER-METZGER, 2021, p.20). It reflects the shifting boundary between privacy and the public as a sociopolitical construction (HAUSEN, 2020, pp.267f.). These transformations have an impact on ideas and models of good parenting, education, relationships and the function of family (BUSCHHORN, 2015, p.220). In the emergence of Frühe Hilfen, which is aimed at supporting parents and strengthening their parenting skills, this area of tension between the private and the public becomes apparent: Who has the responsibility for healthy childhood? Is this a task for society as a whole, or does the responsibility for parenting lie with the parents alone? At what point should state institutions provide support? Which offers should be made to (which) families? Do families have a right to support? What does this mean for care structures? How do FGKiKP position themselves in this context? These questions will be examined more closely in the next section. [36]

When analyzing dominant discourses, positional maps can be used to locate and represent central positions in the situated/situational field of action (FRIESE, CLARKE & WASHBURN, 2022). We used positional maps to differentiate which contentious issues are negotiated and which positions are taken in these negotiation processes (KIMMERLE et al., 2020). With the following map, we illustrate the range of positions in the discussion of responsibility for healthy development, child well-being, support needs, and parenting skills. We map the positions identified from the data between the axes of support needs and parenting skills in the following figure.

Figure 2: Positional map: Support needs vs. parenting skills. Please click here for an enlarged version of Figure 2. [37]

In Figure 2, different perspectives on support needs depending on parenting skills are visualized. The discourses explained in the last section are reflected in the different positions and all manifest themselves in a certain view of parents. The first position is that parents are deficient or even incompetent and the state is responsible for children's well-being and healthy development. This arose from the unfortunate death of a child (Section 1). The media attention of this case was extensive. Parents were characterized as potential dangers to their children. The actions of the role of the state were called into question. A deficit- and risk-oriented view was established, which is also reflected in the term of the framework program "early warning system" (BMFSFJ, 2007, p.1). This risk-oriented view is depicted in the map (Position 1). In this scenario, families need help and possibly even control by professionals. The conclusion of the Position 2 is different: Parents are deficient, but how they deal with it and whether they seek help is their own business. The responsibility for the child's upbringing is a family matter and lies solely with the parents. The next two positions (3 and 4) are based on the assumption that all parents want to be good parents and want the best for their child, but different conclusions are drawn: According to the Position 3, parents must manage their family alone and do not need support, whereas Position 4 is based on the experience that even the best parents need support. Position 4 is taken by FGKiKP, according to the interview analyses of this study. This would result in universal prevention services for all families, which is how Frühe Hilfen program was initially conceived and designed. But this is no longer the case: On the contrary, Position 4 is marginalized. In the meantime, Position 5 in the middle has become established—especially among political decision-makers and stakeholders in Frühe Hilfen. [38]

Position 5, just at the center of the map, illustrates the belief that different parenting skills are necessary in different life situations and that stressful situations may lead to families needing support. This position also stands for the scientific knowledge that when stressful situations accumulate, the risk of endangering the well-being of children increases (VAN ASSEN, KNOT-DICKSCHEIT, POST & GRIETENS, 2020). That is why families who are (over) burdened and families who are exposed to psychosocial risks need support. As evidenced by the analysis of discourse material, socially disadvantaged families are assumedly under multiple stressors and in special need of support. The more stress, the more need for support: Accordingly, Position 5 slides up the map. [39]

The prevailing position is a mixture of scientific findings, expert opinions and political decisions and is based on the following chain of reasoning: Families become a potential risk to their children's well-being when they are overburdened and stressed (LANG et al., 2022). If such risk factors accumulate, then the risk potential for children increases (SALZMANN et al., 2018). Warning signs must be recognized. Therefore, families must be monitored as long as there is a need for help and as long as no other system of help is available. Here, too, the state has a responsibility. On the one hand, parents are seeking advice and need guidance; they even have a right to support; on the other hand, parents are frequently not reached by the help services or refuse support (NEUMANN & RENNER, 2016). At the beginning of the development of Frühe Hilfen, the aim was to reach all families with its services of support and assistance to strengthen parenting skills. In the sense of the health goals and in accordance with the principles of equal health opportunities, socially disadvantaged families in particular must be strengthened in order to protect children. Children with social and health risks should be supported from the beginning to avoid undesirable developments (SPANGLER, VIERHAUS & ZIMMERMANN, 2020). Thus, appropriately qualified specialists are essential, but so is the cooperation and interlinking of sectors and structures (VOLK et al., 2020). [40]

A prerequisite for reaching families, especially those who need help the most, is the availability of qualified professionals. They must be qualified to assess the situation in families and to ensure "systematic and comprehensive access to the target group" (NZFH, 2011, p.20). Health professionals are suitable for this (PABST, SANN, SALZMANN & KÜSTER 2018, p.55). They should support families and, if necessary, refer them to further help from appropriate agencies in the social services. That is where family midwives and, since 2009, FGKiKP in home visiting programs came into play. [41]

In summary, Position 4 reflects the stance of FGKiKP. It can be inferred from the data of this study that they are convinced that parents, regardless of their (potential) competence, need support in developing skills for bringing up their children. The view of the FGKiKP is that everyone has problems or can experience stressful situations in which help and support are important. However, the FGKiKP most urgently want to help those who need their assistance and those who accept the help, cooperate, participate, and are grateful for it. Their offer is voluntary, low-threshold and preventive. The only prerequisite: It must be connected to health ("this is a health mandate," Participant 7). They always have the child's well-being in mind; that is their guiding principle. If the best possible health is not maintained, the well-being of the child is endangered. All children have the right to develop in the best possible way. If this is not pursued, their well-being is threatened. This is where the position differs from social workers, who identify a threat only at a more advanced stage. Social workers do not equate the endangerment of the best possible development with child welfare endangerment. In contrast, the interviewed FGKiKP do not separate child welfare and health. Their attitude is: Those who look closely at health always have the child's well-being in mind as well. [42]

The responsibility for children being safe from violence and thus having a healthy development and environment is identified as a key issue in the arena. Different positions on this issue essentially depend on the answer to the questions: Is there a public responsibility to ensure that children grow up healthy and free of violence? What are the consequences if we assume that this is the case? [43]

The story of Frühe Hilfen is the story of the government's efforts to ensure that children grow up healthy and free from violence. For this reason, FGKiKP based their actions on the protection and the best interests of the child. But the positions in the discourse of responsibility differed. If FGKiKP had their way, family support would go further than it currently does, as shown in the positional map (Figure 2). According to the analysis of the discourse material, the dominant position was that most families can manage on their own. The state was only held responsible for a healthy upbringing in cases of social disadvantage and when there was a threat to the well-being of the child. This position was also the dominant one for economic reasons. FGKiKPs' perspective—all families require support in one way or another—was marginalized because enacting this perspective would require more resources than are available in the social service sectors. Furthermore, it had to be questioned whether the position that all parents need (professional) support in order to ensure the healthy upbringing of their children also represents a strategy to legitimize, secure and expand the field of work and thus the activity of FGKiKP. [44]

The arena of Frühe Hilfen is constituted by numerous players and debated issues. As described in the previous sections, it is an area of tension: between the different social service sectors, between the different social worlds in their professional roles, between early detection of risk potential and acute risk to the well-being of a child, between help and control, between preventive help concepts and intervention-based child protection measures, and between individual and public responsibility. Ultimately, it is always about the well-being of the child and a healthy upbringing. The arena is a site of discourses: It was inferred how different discourses are related to the emergence of the arena Frühe Hilfen and the professional orientation of FGKiKP. A field of work for healthcare professionals was developed and a new professional role was produced and established. The conflicts between the professional actors in this field of work became apparent. The pediatric nurse entered this arena and must negotiate on all sides. [45]

In Germany, with FGKiKP and their deployment in early childhood intervention programs, a new professional role has developed. The essential starting point was the emergence of the arena Frühe Hilfen where various elements were involved, as was demonstrated in this article: Child welfare endangerment as a social problem, the death of a child as discursive explosion (BÜHRMANN & SCHNEIDER, 2008), the discourse on child welfare, child protection and related discourses, the state community, an interface problem within different social services, federal programs, political decisions, professional associations and their interests, health professionals and other elements. We presented the logic of this field's formation by deriving the constitution of the arena with respect to FGKiKP. From their perspective on the turmoil of interacting elements within the arena, it became apparent how FGKiKP are challenged to constantly reposition themselves in order to best accomplish their mission of ensuring that children grow up in a healthy way. [46]

Pediatric nurses are in demand here—and have themselves fought to get involved—because they saw themselves as experts in monitoring and promoting children's health, which, according to the interviews, was their core activity. In this context, they focused on the health of the whole family, also offering psychosocial support and striving to encourage the parent-child-bond. However, they did not see their support for families as panaceas or feel omnipotent. Rather, they perceived themselves as part of a network in which they had a pilot function and referred families to other professionals. [47]

As a constituent of Frühe Hilfen networks, FGKiKP presented themselves in the interviews as part of the social world of pediatric nurses. Nevertheless, they made clear what their specific mission as FGKiKP is and can accordingly be interpreted as a subworld of pediatric nursing. As such, they are in constant negotiation processes with other social worlds and their segments in the arena of Frühe Hilfen. The professional actors with whom they mainly work together are family midwives and social workers. Important questions in this regard pertain to areas of responsibility between the subworlds and issues of to whom professional autonomy is granted. [48]

In particular, this article focused on the controversy between assigning the parents' responsibility for their own children's upbringing and the state's duty to protect and guard all children's well-being. One view is that children grow up best in their families. Thus, the family is of great importance for the child's health. At the same time, there is a public responsibility for the conditions surrounding child development; children need healthy living conditions and circumstances. Both conditions surrounding families and the family itself influence health and can be considered a resource or a potential source of danger or deficiency. As was illustrated, with the establishment of Frühe Hilfen, the government chose to provide professional support to families when needed. Positional maps were used to outline the range of positions and perspectives on the necessity of early childhood prevention or intervention depending on parenting skills. [49]

In Frühe Hilfen, it is possible for nurses to work in a resource-oriented and preventive way and to promote health with families. But the legal regulation only includes families with children up to the age of three. However, the new professional role for pediatric nurses in Frühe Hilfen could be a first step toward community health nursing in the pediatric setting. In home visiting programs such as in the framework of Frühe Hilfen or community health, nursing professionals establish themselves within the family setting, showing up in the living environment, and visiting the families at home. In the sense of "Health in all Policies" (WHO, 2015), health-promoting structures and framework conditions should also be created beyond Frühe Hilfen, both in the healthcare sector and across social service sectors. This requires qualified and specialized professionals to ensure that families receive the support they need. Nursing professionals should decide on the extent and duration of necessary nursing support. But in terms of professional autonomy, the working situation in Frühe Hilfen is not much different from the clinical setting: Pediatric nurses are dependent on the decisions of other professions—medicine or social work—even in matters that concern their core tasks. While nursing is situated in hegemonic structures, professionalization is nevertheless also the responsibility of the professional group: (Pediatric) nurses must position themselves and become visible. [50]

What are the limitations of this study? As the first author has an affiliation to the nursing profession, reflexivity is particularly important in this research inquiry. Within this research, it was a personal intent to give a voice to those working within this field who often go unheard. All reports were deeply mediated by the first author and thus influenced by elements of subjectivity. Regarding the complexity and fluidity of the processes and conditions, there was the risk of oversimplification when one main process is selected. We addressed this by regularly attending research workshops and engaging with theory and methods in order to ensure a critical consideration of the materials at hand (CLARKE et al., 2018, p.39). Being close and at the same time consciously distancing oneself from the material turns an interwovenness with the research field into a resource. The second limiting point is the decision to follow the perspective, relations, and positions of one social world: the nursing profession and the social subworld of FGKiKP. However, the use of situational analysis tools helped us to construct a bigger picture when analyzing the emergence of this new role. [51]

For the investigation of a complex role development in its interrelation with social worlds as well as historical, societal, and political processes, situational analysis offers a social theoretical foundation and excellent tools for analysis. We find discourses in the data corpus of this study that serve as a justificatory framework for the establishment of professional orientation. The analysis of discourses involved in the production of FGKiKP is essential for answering the research question. During this research, we found the use of social worlds/arenas and positional maps helpful as we tried to understand the negotiation processes and processual ordering that resulted in the emergence of a new professional role. Using the concepts of social worlds and arenas primarily helps to map the situation as it is now. In order to fully understand the current situation, it is necessary to look at the emergence of the arena (CLARKE et al., 2018, p.319). Therefore, in this work, a reconstruction of recent developments was carried out on the basis of textual data (legal texts, statements, articles, interview and discussion transcripts, etc.). Using the heuristics of situational analysis, the constituent elements of the new professional role were elaborated and examined in their interdependent arrangement. [52]

In this article, we wanted to show how social worlds/arenas theory, just like the concept of processual ordering, can be used to trace the emergence of a professional role in its development. We were also concerned with demonstrating how the construction of positional maps using discourse material can help provide a critical lens to analyze the situation. However, researchers must be mindful of maintaining an overview of the bigger picture while also analyzing in detail to report on the dynamic evolution of professional arenas. Here, situational analysis becomes an invaluable tool in analyzing social processes in their complexity (OFFENBERGER, 2020). Mapping strategies help to maintain an overview despite this complexity. With the theory/methods package of situational analysis we were able to demonstrate how the discourse around child protection, child welfare, and parenting skills is involved in the emergence of FGKiKP. This discussion sets standards, consequently guiding and legitimizing the actions of these professionals. The core mission of the FGKiKP—with a specific focus on child welfare—can be explained by deriving the emergence of the arena Frühe Hilfen, from which the new professional role was created. [53]

Firstly, we would like to thank the two anonymous reviewers who contributed greatly to developing the text. Further, we want to thank Aljosha KANNEWURF for his eagle eye, Fanni WEBER and Paige LEERSSEN for their eloquence, and Johanna RISTAU for her great help with shortening. We would like to thank Sarah B. EVANS-JORDAN for constructive discussions—her guidance throughout the process was invaluable— and Matthias LEGER for his collegial feedback, Renate BERNER for the encouragement and everyone who participated in the preceding workshop and who brought this special issue to life.

1) They are not to be confused with another occupational profile called Familiengesundheitspflege [family health nursing]. The latter is not primarily a care concept for families with children, nor are pediatric nurses necessarily involved. The two professional profiles also differ in their qualifications. To be as specific as possible about what professional role we mean, we use the abbreviation FGKiKP in the following. <back>

2) FGKiKP are especially in demand when it comes to support families of children with a chronic illness or disability, which will very likely have a need for services over a longer period of time. Legally, FGKiKP can follow families for up to three years, whereas midwives' services are limited to one year. <back>

3) All translations of German texts are the first author's own. <back>

Ayerle, Gertrud; Czinzoll, Kerstin & Behrens, Johann (2012). Weiterbildungen im Bereich der Frühen Hilfen für Hebammen und vergleichbare Berufsgruppen aus dem Gesundheitsbereich: Eine Expertise im Auftrag des Nationalen Zentrums Frühe Hilfen. Materialien zu Frühen Hilfen, 6, Nationales Zentrum Frühe Hilfen (NZFH) in der Bundeszentrale für gesundheitliche Aufklärung, https://www.fruehehilfen.de/fileadmin/user_upload/fruehehilfen.de/downloads/Expertise_Weiterbildungen_FH.pdf [Accessed: January 18, 2023].

BMFSFJ – Bundesministerium für Familie, Senioren, Frauen und Jugend (2006a). Nationaler Aktionsplan: Für ein kindgerechtes Deutschland 2005-2010, https://www.bmfsfj.de/resource/blob/94404/5aa28b65de1e080ce2b48076380f90b1/nap-nationaler-aktionsplan-data.pdf [Accessed: January 18, 2023].

BMFSFJ – Bundesministerium für Familie, Senioren, Frauen und Jugend (2006b). Zwölfter Kinder- und Jugendbericht: Bericht über die Lebenssituation junger Menschen und die Leistungen der Kinder- und Jugendhilfe in Deutschland, https://www.bmfsfj.de/resource/blob/112224/7376e6055bbcaf822ec30fc6ff72b287/12-kinder-und-jugendbericht-data.pdf [Accessed: January 18, 2023].

BMFSFJ – Bundesministerium für Familie, Senioren, Frauen und Jugend (2007). Frühe Hilfen für Eltern und Kinder und soziale Frühwarnsysteme: Bekanntmachung zur Förderung von Modellprojekten sowie deren wissenschaftlicher Begleitung und Wirkungsevaluation, https://www.bmfsfj.de/resource/blob/100674/d8fc9edd616d8832dbe2d863ce86ef2d/ausschreibung-fruehe-hilfen-text-data.pdf [Accessed: January 18, 2023].

BMFSFJ – Bundesministerium für Familie, Senioren, Frauen und Jugend (2008). Lernen aus problematischen Kinderschutzverläufen: Machbarkeitsexpertise zur Verbesserung des Kinderschutzes durch systematische Fehleranalyse, https://www.bmfsfj.de/blob/jump/94214/lernen-aus-problematischen-kinderschutzverlaeufen-data.pdf [Accessed: January 18, 2023].

Bohnsack, Ralf (2002). Gruppendiskussionsverfahren und dokumentarische Methode. In Doris Schaeffer & Gabriele Müller-Mundt (Eds.), Qualitative Gesundheits- und Pflegeforschung (pp.305-25). Bern: Huber.

Bucher, Rue & Strauss, Anselm L. (1961). Professions in process. The American Journal of Sociology, 66(4), 325-334.

Bührmann, Andrea D. & Schneider, Werner (2008). Vom Diskurs zum Dispositiv: Eine Einführung in die Dispositivanalyse (2nd ed.). Bielefeld: transcript.

Buschhorn, Claudia (2015). Familie, Elternschaft und Frühe Hilfen. Soziale Passagen, 7(2), 219-233.

Charmaz, Kathy (2014 [2006]). Constructing grounded theory (2nd ed.). Los Angeles, CA: Sage.

Clarke, Adele E. (1991). Social worlds/arenas theory as organizational theory. In David R. Maines (Ed.), Social organization and social process. Essays in honour of Anselm Strauss (pp.119-158). New York, NY: de Gruyter.

Clarke, Adele E. (2005). Situational analysis: Grounded theory after the postmodern turn. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Clarke, Adele E. (2019). Situating grounded theory and situational analysis in interpretive qualitative inquiry. In Antony Bryant & Kathy Charmaz (Eds.), The Sage handbook of current developments in grounded theory (pp.3-47). Los Angeles, CA: Sage.

Clarke, Adele E. (2021). Straussian negotiated order research, c1960-2020. In Dirk vom Lehn, Natalia Ruiz-Juno & Will Gibson (Eds.), The Routledge international handbook of interactionism (pp.47-58). London: Routledge Taylor & Francis.

Clarke, Adele E. & Star, Susan Leigh (2008). The social worlds framework: A theory/methods package. In Edward J. Hackett, Olga Amsterdamska, Wiebe E. Bijker, Michael Lynch & Judy Wajcman (Eds.), The handbook of science and technology studies (3rd ed., pp.113-138). Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press.

Clarke, Adele E.; Friese, Carrie & Washburn, Rachel (2018). Situational analysis: Grounded theory after the interpretive turn (2nd ed.). Los Angeles, CA: Sage.

Corbin, Juliet M. & Strauss, Anselm L. (2015 [1990]). Basics of qualitative research: Techniques and procedures for developing grounded theory (4th ed.). Los Angeles, CA: Sage.

Egle, Ulrich T.; Franz, Matthias; Joraschky, Peter; Lampe, Astrid; Seiffge-Krenke, Inge & Cierpka, Manfred (2016). Gesundheitliche Langzeitfolgen psychosozialer Belastungen in der Kindheit: ein Update. Bundesgesundheitsblatt, 59(10), 1247-1254, https://doi.org/10.1007/s00103-016-2421-9 [Accessed: January 18, 2023].

Foucault, Michel (2020 [1966]). Die Ordnung der Dinge: Eine Archäologie der Humanwissenschaften (26th ed., transl. by U. Köppen). Frankfurt/M.: Suhrkamp.

Friese, Carrie; Clarke, Adele E. & Washburn, Rachel (2022). Situational analysis as critical pragmatist interactionism. In Adele E. Clarke, Rachel Washburn & Carrie Friese (Eds.), Situational analysis in practice. Mapping relationalities across disciplines (pp.97-110). London: Routledge.

Groß, Lisa; Ginter, Johanna & Zeller, Maren (2017). "… wenn andere Professionen ihren eigenen Blick auf die Sachen haben" – Über die (Nicht-)Herstellung von Zuständigkeit im multiprofessionellen Handlungsfeld der Frühen Hilfen. Neue Praxis – Zeitschrift für Sozialarbeit, Sozialpädagogik und Sozialpolitik, Sonderheft 14, 53-64.

Hausen, Karin (2020). Öffentlichkeit und Privatheit. Gesellschaftspolitische Konstruktionen und die Geschichte der Geschlechterbeziehungen. In Tanja Thomas & Ulla Wischermann (Eds.), Feministische Theorie und Kritische Medienkulturanalyse. Ausgangspunkte und Perspektiven (pp.263-268). Bielefeld: transcript.

Horcher-Metzger, Rosemarie (2021). Im Spannungsfeld von Geburtshilfe und Frühen Hilfen: Eine biografieanalytische Studie zum beruflichen Selbstverständnis von Hebammen und Familienhebammen. Weinheim: Beltz.

Kaba-Schönstein, Lotte (2018). Gesundheitsförderung 2: Entwicklung vor Ottawa 1986. In Bundeszentrale für gesundheitliche Aufklärung (BZgA) (Ed.), Leitbegriffe der Gesundheitsförderung und Prävention. Glossar zu Konzepten, Strategien und Methoden, https://dx.doi.org/10.17623/BZGA:224-i034-1.0 [Accessed: January 18, 2023].

Keller, Reiner (2008). Michel Foucault. Klassiker der Wissenssoziologie, Vol. 7. Konstanz: UVK.

Kimmerle, Birte; Offenberger, Ursula & zu Sayn-Wittgenstein, Friederike (2020). Die Situationsanalyse als Weiterentwicklung der Grounded Theory: am Beispiel einer empirischen Untersuchung zur Kinderkrankenpflege in Frühen Hilfen. Journal für Qualitative Forschung in Pflege- und Gesundheitswissenschaft, 7(2), 86-94.

Kindler, Heinz (2016). Frühe Hilfen und interventiver Kinderschutz: eine Abgrenzung. In Volker Mall & Anna Friedmann (Eds.), Frühe Hilfen in der Pädiatrie: Bedarf erkennen, intervenieren, vernetzen (pp.13-26). Wiesbaden: Springer.

Lang, Katrin; Liel, Christoph; Lux, Ulrike; Kindler, Heinz; Vierhaus, Marc & Eickhorst, Andreas (2022). Child abuse potential in young German parents: Predictors, associations with self-reported maltreatment and intervention use. Child Psychiatry and Human Development, 53(3), 569-581.

Latour, Bruno (2010 [2007]). Eine neue Soziologie für eine neue Gesellschaft: Einführung in die Akteur-Netzwerk-Theorie (transl. by G. Roßler). Berlin: Suhrkamp.

Neumann, Anna & Renner, Ilona (2016). Barrieren für die Inanspruchnahme Früher Hilfen: Die Rolle der elterlichen Steuerungskompetenz. Bundesgesundheitsblatt, 59(10), 1281-1291, https://doi.org/10.1007/s00103-016-2424-6 [Accessed: January 18, 2023].

NZFH – National Centre on Early Prevention (2011). Pilot projects in the German Federal States: Summary of results, https://www.fruehehilfen.de/fileadmin/user_upload/fruehehilfen.de/pdf/NZFH_Pilotprojekte_ENG_09_11.pdf [Accessed: January 18, 2023].

NZFH – National Centre on Early Prevention (2014). Kompetenzprofil Familien-Gesundheits- und Kinderkrankenpflegerinnen und -pfleger in den Frühen Hilfen, https://www.fruehehilfen.de/fileadmin/user_upload/fruehehilfen.de/pdf/Publikation_NZFH_Kompetenzprofil_FGKiKP_2014.pdf [Accessed: January 18, 2023].

NZFH – National Centre on Early Prevention (2015). "Stellt die frühe Kindheit Weichen?": Tagungsbegleiter. Eine Veranstaltung des Instituts für Psychosomatische Kooperationsforschung und Familientherapie des Universitätsklinikums Heidelberg und des Nationalen Zentrums Frühe Hilfen, https://www.fruehehilfen.de/service/publikationen/einzelansicht-publikationen/titel/tagungsbegleiter-stellt-die-fruehe-kindheit-weichen/ [Accessed: January 18, 2023].

NZFH – National Centre on Early Prevention (2016-2018). Qualifizierungsmodule [1-10] für Familienhebammen und Familien-Gesundheits- und Kinderkrankenpflegerinnen und -pfleger, https://www.fruehehilfen.de/service/publikationen/publikationsreihen-des-nzfh/ [Accessed: November 20, 2022].

NZFH – National Centre on Early Prevention (2018a). Mission statement early childhood intervention: Contribution by the NZFH, https://www.fruehehilfen.de/fileadmin/user_upload/fruehehilfen.de/pdf/Publikation-NZFH-Mission-Statement-Early-Childhood-Intervention-Contribution-by-the-NZFH-Advisory-Committee.pdf [Accessed: January 18, 2023].

NZFH – National Centre on Early Prevention (2018b). Dokumentationsvorlage für Familienhebammen und vergleichbare Berufsgruppen aus dem Gesundheitsbereich, https://www.fruehehilfen.de/service/arbeitshilfen-fuer-die-praxis/dokumentationsvorlage/ [Accessed: January 18, 2023].

Offenberger, Ursula (2019). Anselm Strauss, Adele Clarke und die feministische Gretchenfrage. Zum Verhältnis von Grounded-Theory-Methodologie und Situationsanalyse. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung / Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 20(2), Art. 6, http://dx.doi.org/10.17169/fqs-20.2.2997 [Accessed: January 18, 2023].

Offenberger, Ursula (2020). Perspektiven und Potenziale qualitativer Gesundheitsforschung: Ein Plädoyer für interdisziplinäre Brückenschläge. Gesundheitswesen, 84(1), 80-84.

Pabst, Christopher; Sann, Alexandra; Salzmann, Daniela & Küster, Ernst-Uwe (2018). Im Profil: Gesundheitsfachkräfte in den Frühen Hilfen. Nationales Zentrum Frühe Hilfen (NZFH), Forschungsverbund Deutsches Jugendinstitut (DJI) und TU Dortmund (Eds.), Datenreport Frühe Hilfen: Ausgabe 2017 (pp.54-71). Köln: NZFH.

Paul, Mechthild; Backes, Jörg; Renner, Ilona & Scharmanski, Sara (2018). Vom Aktionsprogramm über die Bundesinitiative zur Bundesstiftung Frühe Hilfen. JuKiP – ihr Fachmagazin für Gesundheits- und Kinderkrankenpflege, 7(4), 157-161, http://dx.doi.org/10.1055/a-0635-2600 [Accessed: January 26, 2023].

Renner, Ilona (2012). Wirkungsevaluation "Keiner fällt durchs Netz": Ein Modellprojekt des Nationalen Zentrums Frühe Hilfen (Kompakt). Nationales Zentrum Frühe Hilfen (NZFH) in der Bundeszentrale für gesundheitliche Aufklärung, https://www.fruehehilfen.de/fileadmin/user_upload/fruehehilfen.de/downloads/Wirkungsevaluation.pdf [Accessed: January 18, 2023].

Ruoff, Michael (2018 [2007]). Foucault-Lexikon: Entwicklung – Kernbegriffe – Zusammenhänge (4th ed.). Stuttgart: UTB.

Salzmann, Daniela; Lorenz, Simon; Sann, Alexandra; Fullerton, Birgit; Liel, Christoph; Schreier, Andrea; Eickhorst, Andreas & Walper, Sabine (2018). Wie geht es Familien mit Kleinkindern in Deutschland?. In Nationales Zentrum Frühe Hilfen (NZFH), Forschungsverbund Deutsches Jugendinstitut (DJI) und TU Dortmund (Eds.), Datenreport Frühe Hilfen: Ausgabe 2017 (pp.6-23). Köln: NZFH.

Schone, Reinhold (2010). Kinderschutz: Zwischen Frühen Hilfen und Gefährdungsabwehr. Informationszentrum Kindesmisshandlung/Kindesvernachlässigung (IzKK): IzKK-Nachrichten, 1, 4-7.

Spangler, Gottfried; Vierhaus, Marc & Zimmermann, Peter (2020). Entwicklung von Säuglingen und Kleinkindern aus Familien mit unterschiedlich starken Belastungen: Zentrale Ergebnisse aus der Vertiefungsstudie im Rahmen der Prävalenz- und Versorgungsforschung des NZFH. Nationales Zentrum Frühe Hilfen, https://doi.org/10.17623/NZFH:MFH-ZEV-PV [Accessed: January 18, 2023]

Strauss, Anselm L. (1978a). A social worlds perspective. Studies in Symbolic Interaction, 1, 119-128, https://www.uzh.ch/cmsssl/suz/dam/jcr:ffffffff-9ac6-46e7-ffff-fffffdf1b114/04.22_strauss_78.pdf [Accessed: January 18, 2023].

Strauss, Anselm L. (Ed.) (1978b). Negotiations: Varieties, contexts, processes, and social order. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Strauss, Anselm L. (1978c). Continuous working relations in organizations. In Anselm L. Strauss (Ed.), Negotiations: Varieties, contexts, processes, and social order (pp.105-141). San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Strauss, Anselm L. (1982a). Social worlds and legitimation processes. Studies in Symbolic Interaction, 4, 171-190, https://www.uzh.ch/cmsssl/suz/dam/jcr:ffffffff-f74e-70e9-0000-0000092eea7e/04.20.strauss_82.pdf [Accessed: January 18, 2023].

Strauss, Anselm L. (1982b). Interorganizational negotiations. Urban Life, 11(3), 350-367.

Strauss, Anselm L. (1993). Continual permutations of action. London: Taylor & Francis.

Strauss, Anselm L. (Ed.) (2001 [1975]). Professions, work and careers. New Brunswick, NJ: Transaction.

Strübing, Jörg (2014 [2004]). Grounded Theory: Zur sozialtheoretischen und epistemologischen Fundierung eines pragmatistischen Forschungsstils (3rd ed.). Wiesbaden: Springer VS.

Van Assen, Arjen G.; Knot-Dickscheit, Jana; Post, Wendy J. & Grietens, Hans (2020). Home-visiting interventions for families with complex and multiple problems: A systematic review and meta-analysis of out-of-home placement and child outcomes. Children and Youth Services Review, 114, 1-14, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2020.104994 [Accessed: January 18, 2023].

Volk, Sabrina; Warnecke, Anna-Victoria; Haude, Christin; Pieper, Stefanie; Cloos, Peter & Schröer, Wolfgang (2020). Netzwerke Frühe Hilfen. Multiprofessionelle Kooperation als Grenzarbeit. Nationales Zentrum Frühe Hilfen, https://www.fruehehilfen.de/fileadmin/user_upload/fruehehilfen.de/pdf/Publikation-NZFH-Kompakt-Multiprofessionelle-Kooperation-als-Grenzarbeit.pdf [Accessed: January 18, 2023].

WHO – World Health Organization (1986). Ottawa Charter for Health Promotion, https://www.euro.who.int/__data/assets/pdf_file/0004/129532/Ottawa_Charter.pdf [Accessed: January 18, 2023].

WHO – World Health Organization (1999). Gesundheit 21: Das Rahmenkonzept "Gesundheit für alle" für die Europäische Region der WHO. Europäische Schriftenreihe "Gesundheit für alle", 6, WHO-Regionalbüro für Europa, https://www.euro.who.int/__data/assets/pdf_file/0006/109761/EHFA5-G.pdf [Accessed: January 18, 2023].

WHO – World Health Organization (2015). Health in all policies, https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/151788/9789241507981_eng.pdf;sequence=1 [Accessed: January 18, 2023].

Witzel, Andreas (2000). The problem-centered interview. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung / Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 1(1), Art. 22, https://doi.org/10.17169/fqs-1.1.1132 [Accessed: January 18, 2023].

Witzel, Andreas & Reiter, Herwig (2012). The problem-centred interview: Principles and practice. Los Angeles, CA: Sage.

Birte KIMMERLE is a PhD student at the University of Witten/Herdecke. In her dissertation, she investigates how a professional orientation in nursing is differentiating and a new field of work is developing. She researches, writes, and teaches in the fields of pediatric nursing, child and family health nursing, nursing science, public health, and early childhood intervention. As a research associate and pediatric nurse, she works in the Department of Nursing Science at the Faculty of Medicine at the University of Tübingen.

Contact:

Birte Kimmerle

Witten/Herdecke University, Faculty of Health

Department of Nursing Science

Alfred-Herrhausen-Straße 50, 58455 Witten, Germany

University of Tübingen, Institute of Health Sciences

Department of Nursing Science

Hoppe-Seyler-Str. 9, 72076 Tübingen, Germany

Tel.: +49 (0)7071-29-88805

Fax: +49 (0)7071 29-25321

E-mail: Birte.Kimmerle@med.uni-tuebingen.de | Birte.Kimmerle@uni-wh.de

URL: https://www.medizin.uni-tuebingen.de/de/das-klinikum/mitarbeiter/profil/4353

Friederike ZU SAYN-WITTGENSTEIN is a public health scientist and midwife. She holds the chair in nursing and midwifery science at the University of Applied Sciences Osnabrück, Germany, since 2000. She leads a research program on midwifery care concepts and their impact on women's and their young families' health. She is also a visiting professor at the University Witten/Herdecke since 2014.

Contact:

Prof. Dr. Friederike zu Sayn-Wittgenstein Hohenstein

Osnabrück University of Applied Sciences

Faculty of Business Management and Social Sciences

Barbarastraße 24, 49076 Osnabrück, Germany

Witten/Herdecke University, Faculty of Health

Department of Nursing Science

Alfred-Herrhausen-Straße 50, 58455 Witten, Germany

E-mail: f.wittgenstein@hs-osnabrueck.de

URL: https://www.hs-osnabrueck.de/prof-dr-friederike-zu-sayn-wittgenstein-hohenstein/

Ursula OFFENBERGER is a junior professor at the Methods Center of the Faculty of Economics and Social Sciences at the University of Tübingen and heads the Qualitative Methods and Interpretative Social Research Unit. Her research interests include grounded theory methodology and situational analysis, gender studies, and science and technology studies.

Contact:

JProf. Dr. Ursula Offenberger

University of Tübingen, Department of Social Sciences

Methods Center

Haußerstraße 11, 72076 Tübingen, Germany

Tel.: +49 (0)7071-29-77513

E-Mail: ursula.offenberger@uni-tuebingen.de

URL: https://uni-tuebingen.de/en/faculties/faculty-of-economics-and-social-sciences/subjects/department-of-social-sciences/methods-center/institute/members/offenberger-ursula-jun-prof/

Kimmerle, Birte; zu Sayn-Wittgenstein, Friederike & Offenberger, Ursula (2023). Pediatric nurses in early childhood intervention in Germany—emergence of a new professional role: Situational analysis and mapping [53 paragraphs]. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung / Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 24(2), Art. 5, https://dx.doi.org/10.17169/fqs-24.2.4036.