Volume 9, No. 2, Art. 28 – May 2008

The Poetry of Holocaust Survivor Testimony: Towards a New Performative Social Science

Frances Rapport

Abstract: Performative Social Science provides the research scientist with a much needed platform to move beyond traditional approaches to data collection, analysis and the presentation of study findings towards a response to research questions that closely resonates with the raw materials at hand. For the Performative Social Scientist's voice to be heard, new ways must be found to consider how best to represent the social world, relaxing longstanding and rigid qualitative research frameworks in favour of more contemporary and flexible approaches to working that welcome inter-disciplinary practice. By re-defining the theoretical and paradigmatic boundaries of our studies we can then encourage others to consider a range of alternative positions from which to view the world.

The paper embraces the potential such a platform offers by presenting one Holocaust survivor's lived experiences of these extraordinary events including internment in Auschwitz-Birkenau concentration camp. Through a visual and textual journey that employs photographs and poetic representations derived from one "research conversation" with the survivor, a "photo-textual montage" aims to engender a more empathic response to survivor testimony. The paper also attempts a novel juxtaposition of images and words to present a richer understanding of the researcher's relationship with the survivor, the research process and research outputs. In effect, the paper maps aspects of the research process in "coming to know" the data in chronological, temporal and spatial frames whilst emphasising the importance of presentation style, format and layout. This paper makes visible what is often invisible in more traditional approaches—the researchers own personal journey and the insights that this affords.

Key words: Auschwitz-Birkenau, Holocaust, new forms of representation, poetic representation

Table of Contents

1. Introduction

2. The Research Challenge

3. Poetic Representation as a Methodology

4. The Poetry Within Holocaust Survivor Testimony

5. Poetic Representation and Supporting Material

6. Methodological Reflections

"Misery's the river of the world" (Tom WAITS, 2006)

We arrived in a thunderstorm—raindrops bouncing off the runway, sky black and huge clouds looming overhead. It felt like we had arrived in hell on earth. [1]

Krakow is crowded and I wonder who, amongst the hoards of people roaming the streets buying amber and drinking vodka in Market Square, will be joining us for our guided tour of Auschwitz-Birkenau? Since I started working with Holocaust survivor testimony a year ago, and following hours of taped, in depth interviews with three remaining female survivors in South-East Wales, UK, I have been thinking about the possibility of making this trip. [2]

The tour guide calls out: "Anyone for—The Auschwitz Museum Tour'?" I redden, we board the coach. The Auschwitz Museum Tour—the words stick in my throat and I find myself fighting tears of anger and despair. I didn't realise we were going to a museum. What sort of a trip will this be, to be savoured, a last chance to see a prized Polish possession, a remnant from the war, before we board the plane for London? I think about the strange use of language, and how easily words can lead us astray and consider the nomenclature, The Auschwitz Museum Tour. Perhaps this is meant to portray a trip that has no easy name. Perhaps it is an introduction for a crowd of strangers? Perhaps it is the opening gambit for a coach full of people who are hurtling towards an indescribable destination—the concentration camp at Auschwitz-Birkenau.

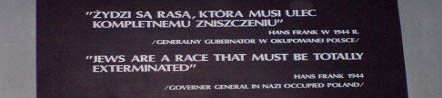

Figure 1: Plaque, Auschwitz Museum, Poland (researcher photograph 2007) [3]

When we arrive in The Auschwitz Coach Park we step out into a rain-drenched world towards the famous gates that will take us into the camp. I am overcome with an overwhelming, breathtaking sadness. Those who have perished—Jews, many Jews, Gypsies too, and Poles, Prisoners of War, disabled Germans—ground my thoughts. I stare down into the mud, down into the semi-darkness, to embedded train tracks amongst tufts of grass. I feel the rain, drip, drip, off my hair, my face, my shoulders. Trees that were once saplings are in abundance now, fine poplars planted by Jews who would not outlive them. The trees stand tall—the fruits of their labour.

Figure 2: Barracks and execution wall in Auschwitz (researcher photograph 2007) [4]

As I consider this impossible fact, I remember Anka's defiant words:

"… we had to leave all our clothes in one heap and I remember […] I still had my wedding ring. At the time when I was getting engaged and married, it was still in Prague and you were not allowed to have good rings like diamonds and things, but my husband managed to get a very nice, amethyst set in silver which was still allowed, that was a semi-precious stone and silver. Or if it wasn't allowed or was allowed, I can't remember, but I still had those two things with me, which was the most precious thing I possessed. And when I saw what's going on there that we have to leave our clothes there, and the mud and the shouting and the starting to run naked and our hair being cut off … I took my two rings and threw them in the mud and I said: 'No German will have it'. In the mud somewhere in Auschwitz, perhaps somebody found them ... ." [5]

When I lift my head the space is silent. We move to Birkenau—groups of people, shifting places, passing one another then looking away.

Figure 3: Train tracks, Birkenau (researcher photograph 2007) [6]

In the far distance is the perimeter fence and beyond that the Polish forest where the fields of chimneys eventually stop. Across the flatlands that mark out this territory are the remains of gas chambers, hurriedly demolished by Germans in recognition of imminent defeat. The chimneys and few remaining crematoria are accompanied by a small number of wooden stables that housed first horses, and then the Jews of Birkenau—a makeshift camp.

Figure 4: Birkenau and Polish forest (researcher photograph 2007) [7]

It is raining heavily now and rain drips down and into my sandals. A young woman accompanying her elderly mother, who has been walking close behind me, offers me her umbrella. I reluctantly accept. She shrugs her shoulders—she has another. The poignant gesture is not lost on me; perhaps she feels it is the least she can do. [8]

This is a topic of immense proportions. The trip described above signifies the harrowing nature of revisiting sites where the Holocaust was perpetrated and the enormity of the task I faced, upon my return to the UK, to interpret those events in a way that was accessible to others. [9]

The trip was undertaken so that I, the researcher, might gain access to events I would never experience but had, nevertheless, been told about through in-depth, extensive and multiple research conversations with three remaining female survivors, resident in South East Wales, UK. To give voice to their perceptions, in pursuit of a greater understanding of the impact of these extraordinary events on their lives and their health and wellbeing, I had travelled to Poland to "see for myself" the places where their stories centred. As a consequence, I was even more daunted by the question of how best to present the study that would impart the survivors' perceptions whilst responding at any level of resonance with the range of research journeys I had undertaken. Perhaps a useful starting point would be to offer some of the challenges I faced to the question of data representation and methodological application, in order to highlight the kinds of questions a researcher might face in making highly emotive data accessible:

How can the researcher make cogent the extraordinary events of the Holocaust in a way that might be of benefit to qualitative researchers?

Can extensive "research conversations" about health and wellbeing, loss and suffering, conducted over a one-year period, be reduced to meaningful research outputs?

How can the character of a survivor who displays a strong sense of goodwill, optimism and dignity, be comprehended in the face of such depravities?

How should the researcher respond to an office full of papers, photographs, tapes, transcripts and personal paraphernalia that deal with others' lives, whilst doing justice through personal interpretation to their stories? ("I know you'll know how to sort it, to put it across", commented Anka).

Can poetic representation, as a research methodology, help illuminate these kinds of lived experiences? [10]

This paper is an attempt to respond to these challenging questions. Whilst defending the use of poetic representation as a methodological framework, the paper will present two pieces of "ethnographic poetry" (RAPPORT, 2008), also known as "poetic representation" (RICHARDSON, 2000) and "poetic transcription" (GLESNE, 1997), derived from one of the many research conversations I had with Anka, one of the three survivors mentioned above. The paper focuses on Anka rather than the other two survivors, whose stories will be presented elsewhere. This decision has been taken because, in spite of the fact that they all spent time in Auschwitz, their stories are very different and it would not have been possible to pay full justice to them all within the same paper. Anka's research conversation centred on Anka's First Day-Last Day experiences of Auschwitz-Birkenau and followed closely on from another Health conversation. As a result Anka expressed her views on her first and last experiences of Auschwitz clearly in terms of her wellbeing during internment. [11]

The paper begins with a clarification of the methodology to lay the groundwork for these ethnographic poems. [12]

3. Poetic Representation as a Methodology

The realist tale remains the dominant paradigm in the storytelling genre in qualitative inquiry. Closely edited and heavily crafted, realist tales disclose little of the characteristics of the teller or the person about whom the story is being told and little emotive content is retained in the telling of the story. Realist tales lay bare the storyline, frequently marked out with events and dates. The realist tale presentation style often absents the researcher from the final text (SPARKES, NILGES, SWAN & DOWLING, 2003). As a consequence, their limitations have been said to include the disavowal of the duality of form and content—how we write about a phenomenon shapes how we come to understand it. Other forms of representation, in particular poetic representation, are shaped by this duality, whilst attempting to penetrate reality, tell the truth, craft new possibility, depict meaning, distil understanding and reduce and resolve raw data to best effect (PIIRTO, 2002). Indeed according to GLESNE (1997), once this is achieved, the final product may be powerfully illuminating in revealing "the wholeness and interconnectedness of thoughts". Consequently, the poetic form in qualitative research has become a firmly embedded genre that has found its way into mainstream social scientific writing (BRADY, 2000). It is widely accessible through a whole host of topics, including: race and pedagogy (HILL, 2005), sport and physical education (SPARKES et al., 2003), and health services research (KENDALL & MURRAY, 2005; CANNON POINDEXTER, 2002), and much time has been given to what SPARKES and DOUGLAS (2007) call: "making the case for poetic representation" (p.170). [13]

Scope and versatility are poetic representation's particular strengths, when traditional methods are often seen to be lacking. Poetic representation along with other, alternative forms of representation, present us with new ways of knowing social reality. Rapport includes poetic representation as part of the Arts-Based Research strand within "New qualitative methodologies" (RAPPORT 2004; RAPPORT, WAINWRIGHT & ELWYN, 2005). Arts-based research approaches and their visual data complement the Performative Social Science domain, which has expressed "dissatisfaction with the limitations in publication and presentation" of data (JONES, 2007). As a consequence, Performative Social Scientists search "the arts and humanities" fields for better transposition and dissemination approaches to qualitative research materials (JONES, 2007). [14]

Poetic representation at its most powerful provides evocative and open-ended connections to data, and is emotively effective in reaching out to the reader's sensibilities, whilst offering up a range of possible data interpretations (KENDALL & MURRAY, 2005; CANNON POINDEXTER, 2002; RICHARDSON, 2002). Poetic representation challenges the senses through the immediacy of limited, carefully chosen and well-crafted words laid down imaginatively, and can evince a vivid response from the reader. As GLESNE (1997) commented, using poetic representation to distil extensive interview transcripts is enabling. Its use highlights the: "… [E]ssence conveyed, the hues, the textures, and then drawing from all the portions of the interviews to juxtapose details into a somewhat abstract re-presentation. Somewhat like a photographer, who lets us know a person in a different way …" (p.206). [15]

4. The Poetry Within Holocaust Survivor Testimony

The survivor testimonies, including the First Day—Last Day interview upon which this paper is based, were extensive, meandering accounts that traversed a range of complex topics. Anka's descriptions of Auschwitz-Birkenau left me feeling shocked. In some sense her stories came across as unfathomable, lacking synchronicity or chronology, but this was, in part, as a result of listening to such difficult subject matter. They were also told in a matter-of-fact, predominantly emotionless way, the effect of which was to add to their impact. They were hauntingly demanding stories to listen to and this was not helped by the constant shift of focus, which reflected the way stories are often told, influenced by the story-teller-story-listener effect. To elicit a response that was anything other than equally compelling, complex, difficult and shifting was perhaps an audacity, yet in support of my decision to present the outcomes of data analysis as poetic representation I turn to the writings of EISNER (1997, 1999). In his disposition on alternative forms of data representation, EISNER argued that in order to re-tell and re-position raw material we must consider the "thinking within the material". By this, he was asserting that representation must be seen to reveal the essential features and characteristics of the original text and through presentation of those essential features, the suitability of the medium. Considering the "thinking within the material" I would go one stage further to say that it is only by studying the raw material that the researcher will recognise within it its optimal re-presentation. That is to say, the approach can be no other than inherent within the raw data, revealed through a process of serious consideration, distillation and thoughtful analysis. So it was with this interview transcript. The original interview upon which the two poetic representations are based took an hour and a half and comprised 24 pages of tightly spaced text notated according to line numbers (see excerpts from the original transcript in Table 1 below).

|

46. (A) And of course, I feel, extremely well in Jewish company, and at home there. 47. (FR) Yes? 48. (A) Always had been, but in my teens and university and all it didn't matter two hoots what sort of crowd I got to. 49. (FR) OK. 50. (AB) But since the war I would say not in, there's Czech people, I still feel at home but, I can feel different somehow here, but I would feel it anyway, the foreigner you may be, but you are never accepted. Not that I mind, you can at least live very easily with it and I don't, sort of, resent it. I always will be the foreigner. Maybe the "bloody foreigner", maybe the "bloody Jewish foreigner" but that doesn't bother me really. _______________________________________________________________________

60. (AB) But I was always able to push it off when its happening and sleep on it and perhaps next day it is better and so far its proved right, though circumstances have changed slightly. I can't give you an example, but this sort of, "I will think about it tomorrow" I really can't explain it, and there is no logical reason for it at all. 61. (FR) But you always thought it will be better tomorrow, or I will deal with it tomorrow? 62. (AB) Or I will deal with it tomorrow or, concrete example is, which was totally misplaced and totally wrong that I am here, that I thought I knew that I would get through, but it was totally irrational and 6 million people didn't, and I am sure they thought the same. 63. (FR) Not because they were all like you, optimistic? 64. (AB) Well no, what I mean, you hope, and either you believe that God will help, which he didn't or I really don't know. But I was, most of the time in a group with youngish people. 65. (FR) But you think that's a sort of characteristic of human nature that people think that they are going to survive somehow? 66. (AB) Yes, that's right. I think that this was proof in the camps. However wrong it was. |

Table 1: Excerpts from the original interview transcript [16]

Once the transcript was read a number of times, certain sections of data of varying lengths suggested themselves as important research scenarios. They stood out—a phrase here, a paragraph there—for the way in which they were integral to an understanding of the whole and without which, the whole would lack coherence. Some "research scenarios" were clearly vignettes or stories within stories, others an end in themselves and still others were less like stories than emphases to labour a point or simple asides to a point. These were less integral to the coherence of the whole, but taken together, played an equal role in clarification and highlighting the transcript's import. In all cases, they were clearly interwoven within the testimony and once identified could be removed and recorded in the order in which they appeared on the page (see for example, Table 2 below).

|

"Hardly know anything about the Jewish history, but I am Jewish." "I feel, extremely well in Jewish company." "The foreigner you may be." "You are never accepted." "Not that I mind, you can at least live very easily with it and I don't, sort of, resent it. I always will be the foreigner. Maybe the—bloody foreigner', maybe the—bloody Jewish foreigner' but that doesn't bother me really." "Thought I knew that I would get through, but it was totally irrational and 6 million people didn't, and I am sure they thought the same." "Everybody got more and more selfish in a situation like that, and if you are only you and your husband to look after and you were both young, one day your husband stole something and the next day you stole something. Much easier than if you had a wider circle of relations. Parents were one thing, but every other person, was a burden because you don't even know if you will find something to give them to eat." |

Table 2: "Research scenarios" derived from the original interview transcript [17]

A process of intensive distillation then ensued, with sections of text worked and reworked until a series of tightly knit, blank prose stanzas were produced, ranging from between one and 15 lines each. Compiling these stanzas into a fluid poetic representation was a time-consuming process, and brought to bare researcher's interpretation in recognising the interview's essential features, whilst at the same time retaining a semblance of meaning across the whole. Many stanzas were omitted in the final piece and others were reduced still further from 15 lines to four or five. The process demanded continual reading and re-reading of the raw material and the research scenarios, both of which were considered together in relation to other interview transcripts from the Series and their research scenarios. The analytic process clarified that one of the strengths of this approach to working is in the retention of the interviewee's voice, intonation, semantic usage and idiom. Consequently, word placement in the poetic representation was carefully retained alongside all grammatical irregularities (Czech was Anka's first language). The process not only led to an ongoing recognition of Anka's presence as the storyteller, but also emphasised her voice, its nuance and timbre. Anka's presence loomed large through intonation and sentence ordering, whilst events, chance happenings and conversations were offered up in the order in which they were spoken in the original research conversation, irrespective of rightful chronology. [18]

5. Poetic Representation and Supporting Material

The two pieces below: Bloody Jewish Foreigner and Like a Victory I Fooled Them are the end result of an extensive analytic process surrounding this "First Day—Last Day" interview (described above). In representing Anka's interview through finely distilled stanzas of blank prose, I hope to present her views and honour her voice. The pieces are my own reworking of Anka's transcripts rather than pieces written directly by Anka, but in the approach to staying true to her voice, they could be construed as a co-authoring process. The pieces should not only be seen as a critique of the Auschwitz-Birkenau experience, but also, through the spoken word of Anka's interpretation and my understanding of that interpretation, the way that these experiences impressed themselves on her life. The ethnographic pieces are supported by two photographs of Anka, one taken recently at her 90th birthday party (below) and another, earlier photograph from Czechoslovakia. At the end of the one-year period in which the extensive "research conversations" took place, I was offered photographs from what was now a very limited collection. The early photographs show a few members of Anka's family, most of whom did not survive the camps. These were cherished possessions, and I was asked that they be copied and returned as soon as possible. The presentation of such treasured possessions confirmed the trusting relationship that had built up between us over time and suggested that Anka was keen to gift a range of aspects of her experience as part of this study, not only her story but also her artefacts. Consequently, the work should be considered a textual and visual montage—image and poem intimately linked and my role was one of decided not whether they should be presented alongside one another, but how this could be achieved most appropriately and effectively.

Figure 5: Anka, Cambridge, April 20th 2007 (with kind permission)

Bloody Jewish Foreigner

I was brought up without any religion.

I knew I was Jewish,

but never learned to read Hebrew,

and in my parents' house nothing was kept.

It has always been there—

being Jewish.

Being born Jewish I went through all what happened,

but I am not a believer.

I would never say that I am not Jewish.

I have no religion.

I don't keep any holidays,

I can't read Hebrew, but I am Jewish.

I feel well in Jewish company.

The foreigner you may be,

the "bloody Jewish foreigner",

but that doesn't bother me.

All my life it works

this—Scarlet O'Hara theory.

"I'll think about it tomorrow",

and perhaps next day is better.

I knew I would get through—

six million people didn't.

People think they are going to survive.

However wrong it was.

Everybody trying to do his utmost

not to offend the Germans.

Like an ant crawling

to get through the day.

My mother wasn't an optimist

but kept my father going.

He clung to her all his life,

wouldn't let her out of his sight.

How is it possible to live with the knowledge

that so many perished?

We saw it every day.

You had to accept that.

I think of them an awful lot,

you are lucky not to have to mourn.

I think only of the nice things,

only good things.

Figure 6: Anka, Czechoslovakia, 1945 (with kind permission)

Like a Victory I Fooled Them

So vivid in my mind

as you sitting in front of me.

I will start talking.

It's very easy.

We arrived through that famous gate.

Birkenau.

Auschwitz.

But Birkenau was the thing.

We arrived through that gate

and before we got there,

we already saw the chimneys—

the fires.

We saw the spouting chimneys

and the smoke and the fire.

"Raus, Raus"

and soldiers up and down.

"Leave all your luggage."

"Come out, come out."

And the smell, which you had never smelled before,

and which you couldn't place.

And the chimneys.

And the smoke.

And the ashes.

And the prisoners in striped pyjamas.

Somebody must have told us

"young ones on this side."

Millions milling around,

at least a thousand people.

They separated men and women.

And when we saw this bedlam

you felt something eerie;

but you didn't know.

And this man—about my age

we knew each other all our life.

"See you after the war?"

I never saw him again.

Dr Mengele with those gloves.

Gauntlets—

in my memory they are gauntlets.

Stood there, boots shining.

"Here" and "there"—he pointed.

Doing—this" with the gloves.

The mother had a five year-old child,

she went the other side.

Nobody was afraid because—

because you didn't know.

Five in a row.

Proceed to the man with those gloves.

So we passed and I passed,

I was with a group of girls.

We went this way.

Never gave it a thought.

I had still my wedding rings,

amethyst set in silver.

I still had those with me,

the most precious things I possessed.

When I saw what's going on

that we had to leave our clothes

and the mud

and the shouting.

And the starting to run naked

and our hair being cut off.

I took my two rings,

and threw them in the mud.

No Germans will have it.

In the mud

in Auschwitz.

The most precious things I had.

Outside or under cover,

I don't remember.

We were shaven—afraid of something,

but we didn't know what.

So they shaved us.

Awful thing to loose your hair.

The most humiliating thing.

They didn't speak, just shaved our hair.

We went through those showers

and were given some horrible rags.

And then some shoes; old shoes,

I happened to get clogs.

If they were too small

we were wise enough not to ask.

In fifths, they led us to the barracks,

big but flimsy, with a door at one end.

The bunks were three-tiered,

Lie down like sardines.

And, "when will I see my parents?"

"You fool, they are in the chimney by now."

They thought we were mad.

We thought they were mad.

But we soon found out,

that they weren't mad.

You saw all the horror and it all fell into place.

And the smell and the fire and the smoke and the shouting

and the dogs and the mud.

Our first day in Auschwitz.

We were never sent to work.

Top bunk.

Awful windows

without glass.

Much colder at the top because the wind blowing through.

I was there ten days,

I was so very lucky

it lasted only ten days.

Roll calls twice a day

and we weren't tattooed.

October '44

they needed every person to work.

The capos only shouted,

"stupid cows", and "you'll soon know".

Jewish from Slovakia.

Been there years.

We stood for those roll calls,

and they counted one, two, three,

And if somebody died

they had to keep the body there.

Ten days later and we were sent walking.

We didn't have luggage and they shaved our heads.

We were given a piece of bread and sent into cattle wagons.

We were leaving Auschwitz and we didn't stop.

All elated.

The train headed west.

October in Poland.

Like a victory I fooled them. [19]

This paper has presented the outputs from one of a number of interviews or research conversations that took place between Anka, a Holocaust survivor, and the researcher between 2006 and 2007. The outputs were juxtaposed with excerpts of text and imagery relating to the research conversation supported by excerpts from the researcher's Dictaphone diary of a trip to Auschwitz-Birkenau concentration camp, to create a textual-visual montage. The montage maps aspects of the researcher's journey, to both signify how the researcher came-to-know the survivor's experiences and her ability to give voice to those experiences, and the insights that that afforded. Using a textual-visual montage format, in keeping with the new Performative Social Science agenda to concentrate on tools from the Arts and Humanities (JONES, 2006), enabled the researcher to "show" and "tell" the creative process—the researcher's engagement with her craft, and the end product—the ethnographic poem and supporting material. In effect, the textual-visual montage format should enable the reader to follow more precisely the researcher's journey, through the range of contextualised and personalised frames of reference. Strengths of this approach might be seen to include: the embellishment of a story that would otherwise be limited in scope by single-frame references, multi-perspectival insights enabling the reader to consider the study's strengths and weaknesses; the possibility for multiple interpretations of multiple data presentations (DENZIN & LINCOLN, 2000; SPARKES, 2002), opportunities for the complementarity and re-contextualisation of text through the support one medium offers to another. In effect, it should be possible to judge the success of the approach by considering the different media as individual presentations and in relation to one another, through continual cross-referencing on the page. [20]

I hope this paper can offer some useful insights for social science and health researchers working with people who have undergone an experience of suffering or trauma, people who feel displaced, disenfranchised or isolated in some way, vulnerable groups or groups who have been caught up with an extraordinary event beyond their control. As I mentioned before, this is not the only way to represent social reality in these situations, but should be seen as one way, a vehicle to elicit an immediate response to emotive data from a wide and varied readership of multi-disciplinary backgrounds. The paper can also be considered, in methodological terms, as adding to the corpus of work currently considering advances in qualitative methods moving beyond the more traditional approaches to data collection and analysis towards the most pertinent approaches for asking and answering the complex research questions and research challenges we face. Above this, I hope the paper pays homage as witness and testimonial to the events of the Holocaust and the fortitude and hopefulness in spite of great hardship of people like Anka, as she herself commented:

"They should know it […] what one human being can do to another without any reason whatsoever. And that really it was done on such a scale […] As we will all die within the next ten years, who will carry the torch afterwards? […] If you didn't live through it, it is like all history. In the next two generations nobody will know what's really true. And the story should be believed." [21]

I would like to thank Anka and the other Holocaust survivors who took part in the research conversations for their time, their insight and the gift of their voice.

Brady, Ivan (2000). Anthropological poetics. In Norman K. Denzin & Yvonna S. Lincoln (Eds.), Handbook of qualitative research (2nd ed., pp.949-979). London: Sage.

Cannon Poindexter, Cynthia (2002). Research as poetry: A couple experiences HIV. Qualitative Inquiry, 8, 707-714.

Denzin, Norman K. & Lincoln, Yvonna S. (2000). Handbook of qualitative research (2nd ed.). London: Sage.

Eisner, Elliot W. (1997). The promise and perils of alternative forms of data representation. Educational Researcher, 26, 4-10.

Eisner, Elliot W. (1999). The promise and perils of alternative forms of data representation. Educational Researcher, 28(1), 18-19.

Glesne, Corrine (1997). "That rare feeling": Re-presenting research through poetic Transcription. Qualitative Inquiry, 3(2), 202-221.

Hill, Djanna A. (2005). The poetry in portraiture: Seeing subjects, hearing voices and feeling contexts. Qualitative Inquiry, 11(1), 95-105.

Jones, Kip (2006). A biographic researcher in pursuit of an aesthetic: the use of arts-based (re)presentations in "performative" dissemination of life stories. Qualitative Sociology Review, 2(1), 66-85.

Jones, Kip (2007). Centre for Qualitative Research: Developing a Performative Social Science at Bournemouth's Centre for Qualitative Research, http://www.bournemouth.ac.uk/ihcs/rescqrpss.html [Access: March 29, 2008].

Kendall, Marilyn & Murray, Scott A. (2005). Tales of the unexpected: Patients' poetic accounts of the journey to a diagnosis of lung cancer: A prospective serial qualitative interview study. Qualitative Inquiry, 11(5), 733-751.

Piirto, Jane (2002). The question of quality and qualifications: Writing inferior poems as qualitative research. Qualitative Studies in Education, 15(4), 431-445.

Rapport, Frances (2004) (Ed.). New qualitative methodologies in health and social care research. London: Routledge.

Rapport, Frances (2008/in press). "I leave everything with you". Ethnographic poetic representation of Holocaust survivor testimony. Anthropology and Humanism.

Rapport, Frances; Wainwright, Paul & Elwyn, Glyn (2005). "Of the edgelands": Broadening the scope of qualitative methodology. Medical Humanities, 31(1), 37-43.

Richardson, Laurel (2000). Writing: A method of inquiry. In Norman K. Denzin & Yvonna S. Lincoln (Eds.), Handbook of qualitative research (2nd ed., pp.923-948). London: Sage.

Richardson, Laurel (2002). Poetic representations of interviews. In James Gubrium & Jeffrey Holstein (Eds.), Handbook of interview research (pp.877-892). London: Sage.

Sparkes, Andrew C. (2002). Telling tales in sport and physical activity: A qualitative journey. Champaign, IL: Human Kinetics Press.

Sparkes, Andrew C. & Douglas, Kitrina (2007). Making the case for poetic representations: An example in action. The Sport Psychologist, 21, 170-189.

Sparkes, Andrew. C.; Nilges, Lynda; Swan, Peter & Dowling, Fiona (2003). Poetic representations in sport and physical activity: Insider perspectives. Sport, Education and Society, 8, 153-177.

Waits, Tom (2006). Misery is the river of the world. Blood Money. [CD]

Frances RAPPORT is a social scientist with a background in the Arts. She is Professor of Qualitative Health Research at the School of Medicine, Swansea University, UK, and Head of the Qualitative Research Unit. She holds the position of Honorary Senior Research Fellow at De Montfort University, Leicester and is a Fellow of the Royal Society of Arts. Her research interests include: survivor stories and trauma, innovative methodological approaches to qualitative health research, and Assisted Reproductive Technology Medicine. Frances is currently exploring "within-method" and narrative approaches to understanding health professionals' reflections on inhabited workspace and Holocaust survivor stories. She is taking a six-month sabbatical at Harvard University to continue her work on Holocaust survivor narratives and trauma.

Contact:

Professor Frances Rapport

Professor in Qualitative Health Research

Centre for Health Information, Research and Evaluation (CHIRAL)

School of Medicine

Swansea University

Grove Building

Singleton Park

Swansea

SA2 8PP, UK

Tel.: +44 01792 513497

Fax: +44 01792 513430

E-mail: F.L.Rapport@Swansea.ac.uk

Rapport, Frances (2008). The Poetry of Holocaust Survivor Testimony: Towards a New Performative Social Science [21 paragraphs]. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung / Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 9(2), Art. 28, http://nbn-resolving.de/urn:nbn:de:0114-fqs0802285.